1. Introduction

Dating from 1931 [

1], research on tungsten electrodeposition has lead to development of several kinds of tungsten alloys with metals such as Fe, Co, Ni [

2] and Cu [

3], which act as

inducing metals for the reduction of tungstates [

4]. Besides tungsten, such alloy must contain one or more inducing metals. Most original papers cover only selected binary or ternary alloys, focusing mainly on their applicational properties. Most common applications of electrodeposited tungsten alloys include protective and decorative coatings [

5] or catalytic layers for hydrogen evolution [

6].

An attempt of obtaining an alloy of higher complexity in terms of qualitative composition and controlling it quantitatively should rely on a comparison of deposition rates for individual metals in the system, mostly the inducing metals. However, mentioned background makes the comparison difficult and uncertain. Minimum variables necessary to calculate the rates are current density j, current (faradaic) efficiency CE and exact alloy composition, or at least atomic content of tungsten at%W for binary alloys. In such case, deposition rate v of a certain element X on normalized area of cathode, in z-electronic process, can be expressed as v = j · CE · F⁻¹ · z⁻¹ · at%X [mol · s⁻¹ · m⁻²]. Although CE is a quantity that is crucial to describe the deposition process, numerous authors skip it in the publications. Furthermore, most works that contain the needed information, present it not as exact numbers, but rather as graphs, which would rather focus on influence of a particular parameter on the outcome. Multitude of these parameters which affect the deposition rates make it difficult to compare results of various researchers, especially that each of them conducts the experiments under different conditions, ie. bath composition (both qualitative and quantitative) and temperature. Thus, despite of almost centennial of research on tungsten codeposition, the numerical results cannot be easily unified.

In

Table 1 several sets of data were collected, concerning the deposition rates

v of Fe, Co and Ni in binary alloys with W. The numbers were calculated from

j,

CE and

at%W, contained in tables or gathered from plots (in the latter case, the source was mentioned with an * asterisk). In lack of more general criteria of choice, the highest achieved rate of Fe/Co/Ni deposition was chosen for each source. All

v values [mol · s⁻¹ · m⁻²] were multiplied by 10E5 for legibility.

Although occurence of major discrepancies between the rates achieved by separate researchers cannot be denied, the results do overlap partly. Most notably,

v of Ni is usually more than an order of magnitude lower compared to Fe and Co. Difference in

j applied by various authors is the most obvious cause of the inconsistency in the results, but even for the same

j, the numbers vary due to divergency of other plating conditions, such as bath composition and temperature. Nevertheless, the papers cover some important cases of influence of those parameters on the

v. Plots of

at%W and

CE against

j are quite common [

7,

8,

9,

11,

12,

14], even though some authors stay at constant value of

j, described as optimal [

10,

16]. Plots of inducing metal deposition rates against

j tend to increase monotonically due to the apparent increase of current passing through the circuit. The increase is concave down though, mostly because of

CE decrease and simultaneous increase of

at%W in the alloys. Besides, applying pulse current was found to possibly increase

at%W and

CE, with higher

v of cobalt at higher frequencies of the pulses [

10]. Other variables found in foregoing papers include ia. temperature [

13] or tungstate concentration [

15], which gave no clear correlations with

v of nickel.

Introducing ions of additional inducing metal to bath, which leads to deposition of ternary or multinary alloys, has a certain influence on deposition rates for particular metals. Presence of Cu(II) ions in the solution [

17,

18] inevitably lowers

at% of other metals, but increases the

CE of the whole deposition process, especially in case of WNiCu alloys. As regards mixing more than one iron-group metal into the alloy, interpretation of the data contained in previous works is even more difficult, as most of works on electrodeposition of ternary tungsten alloys do not cover any comparison to the binary alloys.

As mentioned before, more precise control of deposition rates of particular metals is an essential requirement for obtaining W alloys with more than one inducing metal. To obtain an alloy consisting of three or more metals, deposition rates for particular metals have to be calculated for the same system at constant plating parameters. Thus, the following work is intended to quantify the rates of Fe, Co, Ni and Cu codeposition with W and to evaluate ratios between these rates, as a prelude to research on electrodeposition of multi-component alloys of tungsten.

2. Materials and Methods

As this study concerns comparison of deposition rates of the inducing metals in alloys with tungsten, several different materials were obtained at varying concentrations of inducing metal ions, while keeping all the essential conditions constant. All samples were deposited from plating bath, which composition is presented in

Table 2. All reagents were analytical grade.

Usage of ferric ammonium citrate deserves some individual attention. For electrodeposition of iron–tungsten alloys, baths containing iron(II) salts are commonly used, such as ferrous sulphate. Ease of oxidation of iron(II) to iron(III) makes such baths unstable, so they would have to be either freshly prepared for each experiment, or constantly monitored. Replacing Fe(II) with Fe(III) solves this problem, so the Fe(III) ions concentration is known more precisely. Choice of this particular ferric compound was justified by its high solubility and by Fe(III) ion being already in an appropriate citrate complex.

As marked before, concentrations of particular inducing metal salts varied throughout the experiment. Utilized baths can be divided into four series A, B, C and D, respecting their composition. In series A (12 samples) were baths containing one inducing metal salt, Fe(III), Co(II) or Ni(II) in concentration of 27 mM, that produced binary alloys WFe, WCo or WNi respectively. Series B (12 samples) consisted of baths with two (13.5 mM) or three (9 mM) inducing metal ions at equal concentrations summing up to 27 mM altogether, leading to deposition of ternary alloys WFeCo, WFeNi, WCoNi, and quaternary WFeCoNi. Whereas results of deposition from bath series A and B allow to compare deposition rates of particular iron-group metals in the same conditions, the remaining two series were set up to examine influence of Cu on deposition rates in a high entropy alloy. Series C (WFeCoNi, 11 samples) and D (WFeCoNiCu, 9 samples) consisted of baths designed to generate respectively quaternary and quinternary alloys possibly close to equal

at% of the metals, ie. equal deposition rates. Exact ion concentrations used in C and D bath series are gathered in

Table 3.

During the electrodeposition, the plating bath was separated from 0.25 M sodium sulphate solution as an anode electrolyte. Two inert Ti/RuOx anodes were placed symmetrically around the cathode. All samples were deposited with constant current at current density j = 50 mA·cm⁻². Potentiostat/galvanostat EG&G PAR 173A was utilized as the source of current. All experiments were conducted at constant temperature 65°C. The coatings were plated on .999 Ag foil, cut in rectangles so that the area of the substrate was A = 2.4 cm². Duration of the deposition was t = 1800 s. Before deposition, all substrates were cleaned by annealing in CH₄–O₂ flame, then mechanically scrubbed with a detergent and finally washed with ethanol. Each time, the clean Ag substrate was weighed on an analytical balance with precision ± 0.1 mg. After the deposition, each sample was weighed again in order to calculate the mass of the deposit Δm.

Composition of the deposited alloys was measured using FE SEM Zeiss Merlin with Bruker Quantax 400 EDS analyzer. EDS spectra were acquired as an average from a (0.3 x 0.4) mm site in the very centre of the sample. Numerical results were calculated from the acquired spectra using the original Bruker software and normalized to 100% after omitting oxygen, presence of which indicates surface oxidation of the alloy, and carbon, which might contaminate the surface before measurement. Mass content wt%X and atomic content at%X of the metals in the samples can be easily converted into each other, utilizing molar masses M of all the metals present in the alloy.

For each metal X (Fe, Co, Ni or Cu), the deposition rate [mol · cm⁻² · s⁻¹] calculated for a particular sample v X = Δm · wt%X · A⁻¹ · M⁻¹ · t⁻¹, assuming that the electrodeposition process is should not be affected by changing A or t. The final results, ie. values of v of the inducing metals, at% of tungsten and other metals, and CE of the whole process, were calculated as an average within the four mentioned bath series. All following values of v have been multiplied by 10E5 for legibility of the data.

3. Results

All obtained alloys form shiny gray metallic coatings, well adherent to the substrates. Only WFe coating was observed to turn brownish after longer exposition to air, which indicates that this alloy is prone to corrosive oxidation more than others.

In

Table 4 results for binary alloys are gathered, ie. experiment series A. Presented data include deposition rates of the inducing metals, atomic content of tungsten, and faradaic efficiency of the deposition processes. All the rates here and further are expressed in SI units [mol · m⁻² · s⁻¹] and multiplied by 10E5 for legibility.

Efficiency of deposition depends strongly on which metal was codeposited with tungsten, and so do the deposition rates for particular metals. More precisely, deposition rate of cobalt for WCo alloy is about 4 times higher than that of nickel in WNi alloy, and deposition rate of iron in WFe is about 10 times higher than that of nickel. In general, tungsten content in all of these binary alloys is ca. 24%, but in it tends to be slightly higher when the deposition is slower. Thus, out of these three alloys, WNi has the highest W content, and WFe has the lowest in present study.

In experiment series B, ternary and quaternary alloys were deposited, utilizing baths containing equal concentrations of the inducing metal salts. Therefore, compared to series A, concentration of a particular metal was two times lower for a ternary alloy and three times lower for the quaternary WFeCoNi alloy.

Table 5 contains relevant data for alloys deposited in series B.

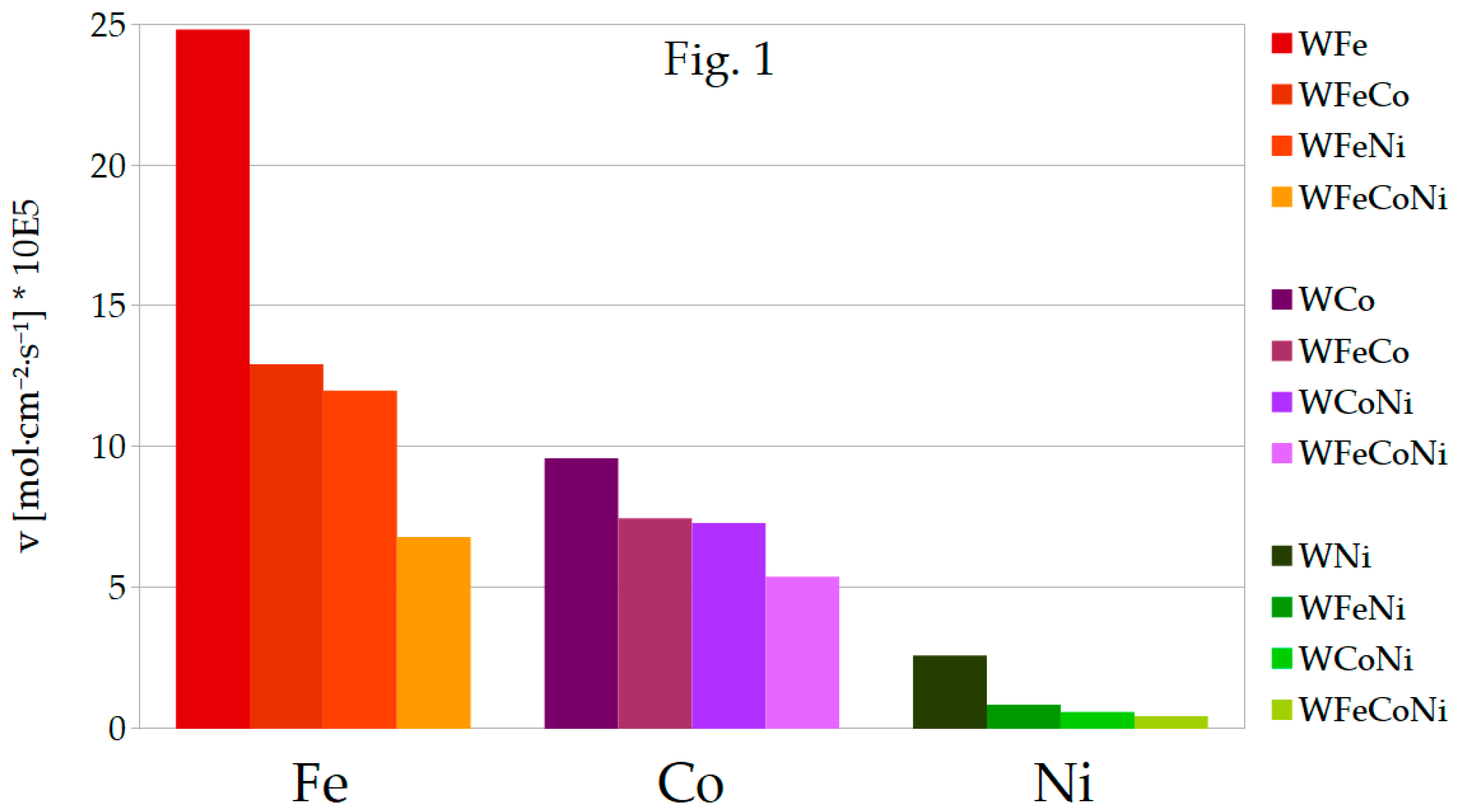

The results from

Table 4 and

Table 5 are presented below as bar charts in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

Figure 1 is a straight representation of the values of

v for Fe, Co and Ni deposition in particular binary, ternary and quaternary alloys. The values of the deposition rates as given in

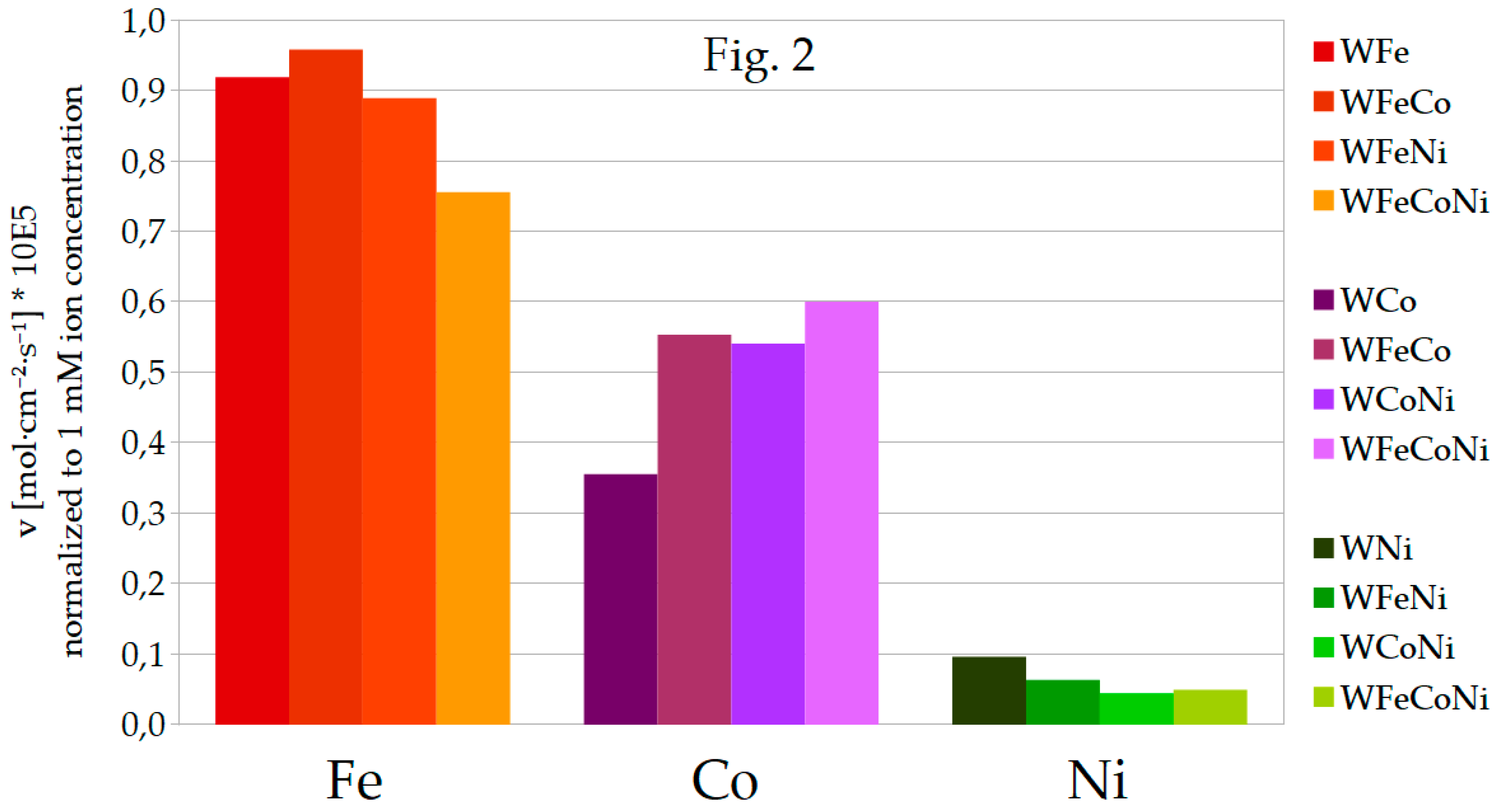

Figure 1 are well comparable visually within the categories of binary, ternary or quaternary alloys. However, as it was already mentioned, particular inducing metal ion concentrations for ternary metal deposition were divided by half, so the constant 27 mM concentration is shared by the two inducing metal ions in bath, and so on with the bath for the quaternary alloy and three inducing metal ions. Thus,

Figure 2 is presented as well, where the rates have been normalized to 1 mM metal ion concentrations, that is divided by 27 for the binary alloys, by 13.5 for the ternary alloys and by 9 for the quaternary WFeCoNi alloy deposition. Presented in such way, the differences between the values of the deposition rates can be compared for the particular inducing metals, especially in terms of divergencies from the linearity of

v as a function of metal ion concentration.

In general, during the deposition of the ternary alloys, iron still deposits at highest rate, whilst nickel deposits most slowly. In comparison to WFe, deposition rate of Fe is about 2 times lower for WFeCo and WFeNi alloys, and approximately 3 times lower for WFeCoNi, so it seems to be close to proportional to iron concentration in the plating bath. However, deposition rates for the remaining metals change in a different manner. As for Co, deposition rates in the ternary alloys are noticeably higher than half the rate for WCo, also the deposition rate in WFeCoNi is higher than a third of that for the binary alloy. The opposite can be observed for Ni: rates of Ni deposition in the ternary and quaternary alloys are much lower than would be expected if they were proportional to nickel concentration in baths. For that reason, in the quaternary WFeCoNi alloy, deposition rates of Fe and Co approach each other, so they are both more than 10 times higher than the rate of Ni deposition. Tungsten content in the ternary alloys containing nickel is close to that in the binary WNi, and for WFeCo, it is very close to tungsten content in WFe. In the WFeCoNi alloy, tungsten content is somewhat in the middle, closest to at% W in WCo alloy. In most cases, faradaic efficiencies for the ternary and quaternary alloys are close to mean values of the efficiencies for the binary alloys with corresponding metals.

Table 6 contains analogous data for experiment series C and D, ie. quaternary WFeCoNi and quinternary WFeCoNiCu alloys. As mentioned earlier, these baths contained adjusted concentrations of the metal ions, so to obtain alloys consisting of possibly equal

at% of the inducing metals, also included in the tab. Due to

v of nickel over 10 times lower than that of the other metals, Ni(II) concentration had to be an order of magnitude higher than of the other metals (see

Table 3). Also, proper concentration of Cu(II) was determined in a sequence of subsidiary tests between series C and D.

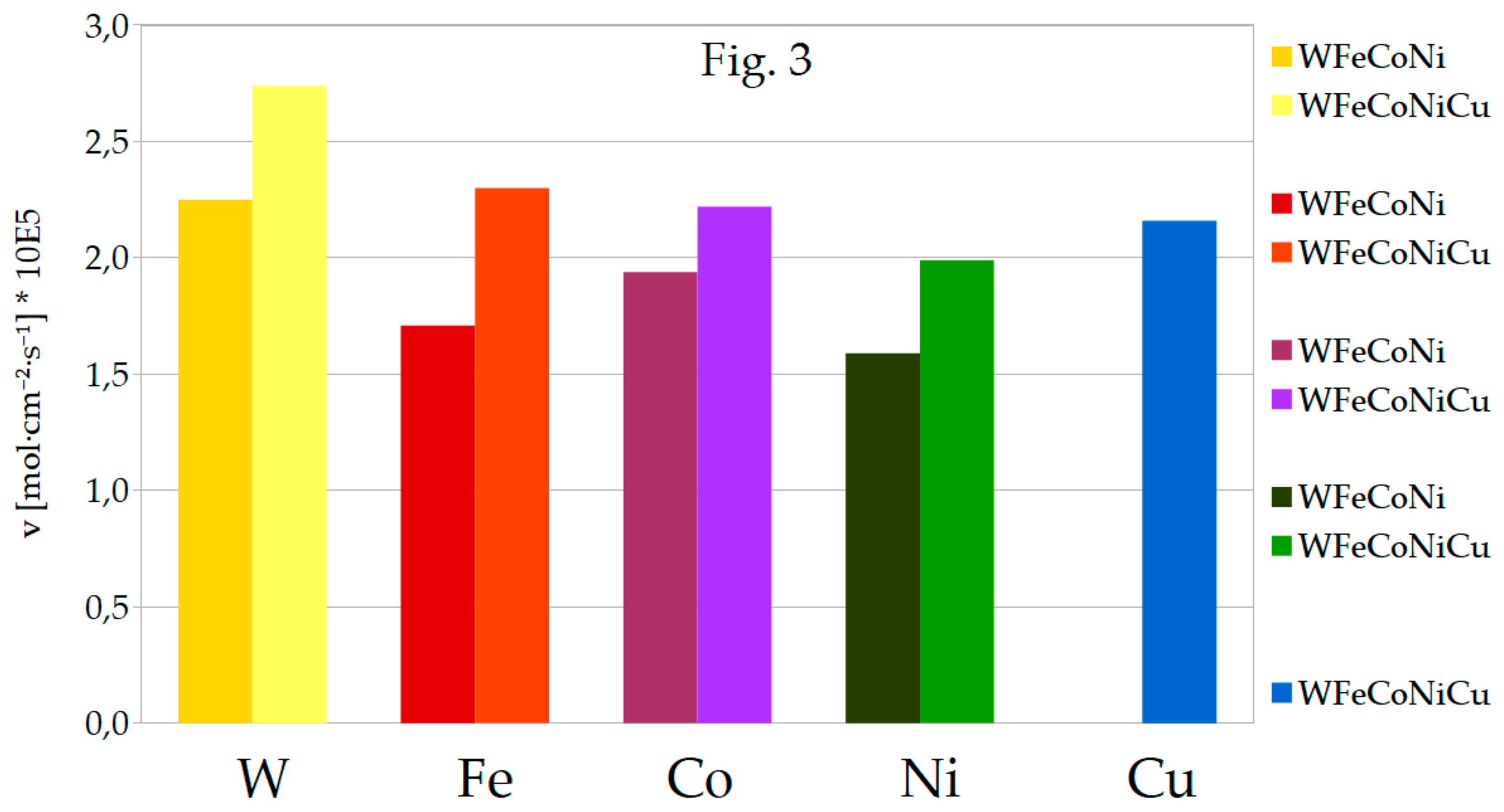

The values of the deposition rates contained in

Table 6 are also depicted in

Figure 3 in a visually comprehensive manner.

Apparently, the deposition rates of each inducing metal in both alloys are indeed close to equal, within the standard deviation intervals. When comparing WFeCoNi series B and C, it should be noticed that tungsten content in the latter exceeds 30%, which is much higher than in any previous alloy in series A or B. On the other hand, faradaic efficiency of the deposition process reaches only 5%, which is lowest than for any other alloy except binary WNi.

For the quinternary WFeCoNiCu alloy (series D), tungsten content goes back to 24%, but all the rates of metal deposition are about 1.25 times higher than without copper, including v of tungsten. Deposition rate of Fe seems to be the most affected, and Co the least, it is still clearly higher though. Obviously, the copper itself deposits simultaneously with the other metals. Altogether, introduction of copper makes the faradaic efficiency 1.5 times higher. Taking the standard deviation ranges into account, obtained high-entropy WFeCoNiCu alloys have well balanced atomic composition with 24% tungsten and ca. 19% of each inducing metal.

4. Discussion

Out of three most researched binary alloys of tungsten, ie. with Fe, Co or Ni, WFe is deposited with highest faradaic efficiency, and WNi with lowest, which was also observed in cited papers. Overall, achieved deposition rates are somewhat lower than rates found in literature (see

Table 1), which may be caused by various factors such as discrepancies in current densities, bath composition and temperature. However, for a precise control of composition of a quinternary alloy, knowledge of ratios between the rates of electrodeposition in the same conditions is way more important than maxing out the rates themselves.

In general, higher deposition rates of the inducing metals coincide with higher deposition rates of tungsten and higher overall efficiency of the deposition process. Assuming that [(Me)(WO₄)(H)(Cit)]

n⁻ type complex is a direct precursor of the electrodeposited alloy, according to the most recent mechanism proposal for tungsten codeposition [

19], it should indicate that the complex stability constant is increasing in sequence Me = Ni < Co < Fe.

Copresence of two or three inducing metal ions in one plating bath at equal concentrations causes disproportionate changes in deposition rates of the inducing metals. Most notably, Ni deposition rate goes down in presence of other inducing metals, which also could be explained by competition of the metal ions to form the adequate precursor complex.

Tuning the bath composition in such manner that the metal deposition rates are equal inevitably requires that metal ions in the solution be mostly nickel (about 88% of inducing metal ions in the bath). Hence, the faradaic efficiency is relatively low. However, even though the metal ions are mostly nickel, the efficiency of the deposition from such bath is 2.5 times higher, compared to deposition of binary WNi alloy. Also, in the quaternary alloy deposited from such bath, at%W is undoubtedly highest, exceeding 30%, which shows that this balanced setting is optimal in terms of tungsten content. Addition of copper ions into the plating bath not only introduces copper into the alloy, but also catalyzes deposition of every other metal, which leads to a remarkable boost in current efficiency. Question about exact role of copper in the mechanism of induced codeposition is yet to be answered in future studies.

Taking all the above into consideration should enable relatively precise control of Fe, Co, Ni and Cu content in electrodeposited tungsten alloys of higher complexity, especially in high-entropy quinternary WFeCoNiCu alloy. The deposition rates of the studied metals depend on their ion concentrations in a manner linear enough to modify the metal content predictably. Further iterations of adjusting the inducing metal ion concentrations may easily allow to tune the composition of the high-entropy alloy, either for obtaining excess of a chosen metal or to have the material composition well balanced. Due to completely different behavior of tungsten species within supposed codeposition mechanism, controlling W content in the alloy would be a completely different task, thus was not included in the present study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, review and supervision, M.D.; experimental work and writing, T.R.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fink, C.G.; Jones, F.L. The Electrodeposition of Tungsten from Aqueous Solutions. Trans. Electrochem. Soc. 1931, 59, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsyntsaru, N.; Cesiulis, H.; Donten, M.; Sort, J.; Pellicer, E.; Podlaha-Murphy, E.J. Modern trends in tungsten alloys electrodeposition with iron group metals. Surf. Eng. Appl. Electrochem. 2012, 48, 491–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacal, P.; Indyka, P.; Stojek, Z.; Donten, M. Unusual example of induced codeposition of tungsten. Galvanic formation of Cu–W alloy. Electrochem. Commun. 2015, 54, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abner Brenner, Electrodeposition of alloys. Principles and practice, Academic Press, New York and London (1963).

- Brenner, A.; Burkhead, P.; Seegmiller, E. Electrodeposition of Tungsten Alloys Containing Iron, Nickel, and Cobalt. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. 1947, 39, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Piron, D.L.; Sleb, A.; Paradis, P. Study of Electrodeposited Nickel-Molybdenum, Nickel-Tungsten, Cobalt-Molybdenum, and Cobalt-Tungsten as Hydrogen Electrodes in Alkaline Water Electrolysis. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1994, 141, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobanova, Z.I.; Grabco, D.Z.; Danitse, Z.; Mirgorodskaya, Y.; Dikusar, A.I. Electrodeposition and properties of an iron-tungsten alloy. Surf. Eng. Appl. Electrochem. 2007, 43, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsyntsaru, N.; Bobanova, J.; Ye, X.; Cesiulis, H.; Dikusar, A.; Prosycevas, I.; Celis, J.-P. Iron–tungsten alloys electrodeposited under direct current from citrate–ammonia plating baths. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2009, 203, 3136–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietzke, M.H.; Holt, M.L. Codeposition of Tungsten and Iron from an Aqueous Ammoniacal Citrate Bath. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1948, 94, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donten, M.; Stojek, Z. Pulse electroplating of rich-in-tungsten thin layers of amorphous Co-W alloys. J. Appl. Electrochem. 1996, 26, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; El Rehim, S.A.; Moussa, S. Electrodeposition of noncrystalline cobalt–tungsten alloys from citrate electrolytes. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2003, 33, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsyntsaru, N.; Cesiulis, H.; Budreika, A.; Ye, X.; Juskenas, R.; Celis, J.-P. The effect of electrodeposition conditions and post-annealing on nanostructure of Co–W coatings. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2012, 206, 4262–4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, T.M.; Eliaz, N.; Gileadi, E. Electroplating of Ni[sub 4]W. Electrochem. Solid-state Lett. 2005, 8, C58–C61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Bairachna, T.; Podlaha, E.J. Induced Codeposition Behavior of Electrodeposited NiMoW Alloys. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2013, 160, D434–D440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, O.; Gileadi, E. Electroplating of High Tungsten Content Ni/W Alloys. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2000, 3, 543–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesiulis, H.; Baltutiene, A.; Donten, M.; Stojek, Z. Increase in rate of electrodeposition and in Ni(II) concentration in the bath as a way to control grain size of amorphous/nanocrystalline Ni-W alloys. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2002, 6, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernickaite, E.; Tsyntsaru, N.; Cesiulis, H. Electrochemical co-deposition of tungsten with cobalt and copper: Peculiarities of binary and ternary alloys coatings formation. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2016, 307, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacal, P.; Donten, M.; Stojek, Z. Electrodeposition of high-tungsten W-Ni-Cu alloys. Impact of copper on deposition process and coating structure. Electrochimica Acta 2017, 241, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gileadi, E.; Eliaz, N. The Mechanism of Induced Codeposition of Ni-W Alloys. ECS Trans. 2007, 2, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).