1. Introduction

Precision agriculture (PA) is defined as a particular agricultural management based on the observations, measurements, and responses of a set of quantitative and qualitative variables affecting agricultural production [

1]. The first step in the PA approach is the acquisition and collection of data from different sensors, such as optical, multispectral, and geophysical ones, aimed at obtaining a deep characterization of the plants and monitoring their crop [

2]. Therefore, PA commonly includes a wide range of techniques and methodologies which need to be properly combined to develop an increasingly sustainable agricultural management [

3,

4]. In this regard, the combination of data from different sources is bound to the proper management of the reference system, commonly handled through Geographic Information Systems (GIS), which are highly suitable tools for multidisciplinary studies [

5]. Among all, geophysics and geomatics techniques represent fundamental support tools for PA applications, giving essential information for cultivation protection and monitoring [

6].

In particular, geophysical analyses involve the study of the chemical characteristics of the plants and the shallow part of the subsoil, using ad hoc instruments, such as georadars [

7,

8]. On the other hand, geomatic techniques allow obtaining quantitative parameters describing the plants, in terms of height, crown extension and volume. The use of Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) in the agricultural field dates back to the ‘90s, with the development of farm machines equipped with GNSS receivers. However, GNSS instruments cannot ensure high-density datasets without resulting in very time-consuming and expensive surveys [

9]. Therefore, in this context, they are commonly employed as a support for other techniques. In the early 2000s, drones became the new major players in precision agriculture, being a very useful platform to transport different types of sensors (i.e. LiDAR, multi-spectral, optical cameras). Indeed, the main advantages of using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) are related to the fast performance and lower costs compared to other geomatic techniques [

10].

Several studies addressed the use of UAV remotely sensed data for forestry or agricultural applications, mainly relying on LiDAR datasets or multi-spectral imagery [

8,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Moreover, most of the applications are framed in forest environments, where tall and dense trees are present, and the main focus is crown identification and classification [

12,

13,

15,

18,

19,

20,

21]. On the other hand, recent studies have been conducted over areas with lower vegetation, using photogrammetric or LiDAR data sources, providing promising results [

14,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Compared with LiDAR point clouds, photogrammetric data are known to be generally noisier and less accurate, since they do not provide information about the terrain surface but only in the upper layer [

12]. Conversely, information representing the ground level can be retrieved from LiDAR data by exploiting multi-return echoes penetrating into the canopy [

28,

29]. This fact commonly ensures a better accuracy of the ground representation, which is crucial for a fair reconstruction of the 3D structure of vegetation [

12]. Nevertheless, this benefit is obtained with more expensive instruments, requiring also more advanced carrying platforms.

Whatever the employed technique, analysis in the agricultural field generally relies on raster-based methods, through Canopy Height Models (CHM), or others combining point clouds and raster data [

30]. The CHM represents the trees’ crowns and their heights from the ground, hence it is obtained as the difference between a Digital Surface Model (DSM) and the related Digital Terrain Model (DTM). The reference DTMs can be generated by exploiting automatic filters to identify the points representing the ground surface. Originally, the algorithms for vegetation filtering were designed for LiDAR datasets, although they can be employed for photogrammetric applications [

21]. Indeed, different software implements automatic filters for the vegetation that yet lead to better performances in forests rather than in areas with low trees [

12,

22,

23,

24]. However, fruit farmland or vineyards are characterized by the presence of sparse trees and relatively low heights, ranging from approximately 1 m and 4 m [

31]. A similar situation concerns soils contaminated by pollutants or heavy metals undergoing phytoremediation or reclamation by planting trees or shrubs which can improve the chemical and physical characteristics of the soils and reduce the pollution level [

32,

33].

This paper presents the first results of a research concerning the use of aerial photogrammetry acquired by very low-cost UAV to retrieve dimensional parameters of the trees, in particular their height. The study belongs to a wider project aimed at finding algorithms and procedures to analyse and monitor soils contaminated with heavy metals and undergoing phytoremediation process, based on the definition of dimensional, geophysical and chemical parameters. The final purpose is to define specific algorithms for different soils, plant species and microbial populations allowing the identification of the optimal conditions for the contaminated site’s restoration. To this aim, two study areas have been chosen to carry out the geomatic surveys, named “Area 1” and “Area 2”, having different characteristics in terms of mean trees’ height (Area 1: 5 m; Area 2: 0.70 m), to test the procedure even in a context of low trees. Area 1 is 1.2 ha wide and covered by approximately 80 olive trees with 5 m of mean height. Three low-cost UAV campaigns have been performed in this area, under the same conditions but with different flying altitudes: 30 m, 40 m and 50 m, in order to evaluate the impact of different resolutions of the images (Ground Sampling Distance - GSD). Area 2 extends for 0.6 ha, with nearly 600 young trees belonging to three different species (lentisk, poplar and oleander) having different mean heights: about 50 cm, 70 cm and 85 cm for the lentisk, poplar and oleander, respectively. Only one UAV survey has been performed on Area 2, flying 42 m high.

Starting from the photogrammetric datasets, the implemented workflow involves the elaboration of the reference Digital Terrain Model (DTM), the UAV point clouds and the Digital Surface Models (DSM) and a GIS-based procedure for the extraction of the trees’ heights, based on a local maxima approach.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Areas

Two different study areas have been chosen for the analysis, having different characteristics, especially in terms of mean trees’ heights. The analysis aimed to test the possibility of applying the same method of height extraction in different conditions, in order to evaluate the possible limits of the methodology.

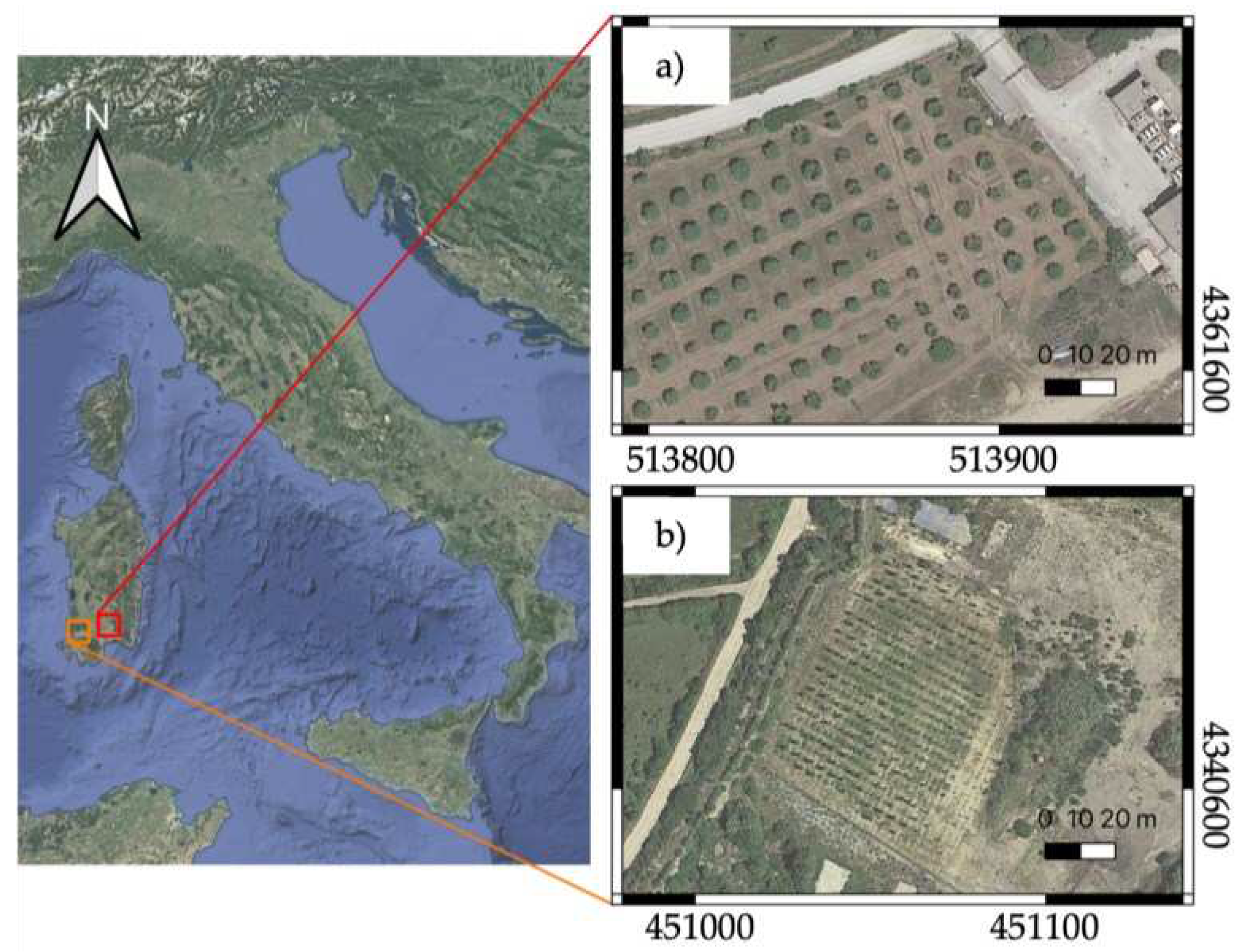

The first site, named “Area 1”, is part of an olive grove extended for about 1.2 hectares and located in the South of Sardinia, Italy (

Figure 1a). The olive trees follow a precise configuration along different rows and the trees' heights range approximately between 3 m and 6 m. This area was chosen as the optimal case study for our application, considering the mean trees' heights, the canopy extension and the density of the foliage.

The second site, hereafter called “Area 2”, consists of 26 plant rows with 2-3 m of inter-distance extending for about half a hectare (

Figure 1b). Since the planting of the area was part of a requalification project started a few months before the survey, here the plants' heights are generally very low, ranging between 10 cm and 140 cm. Moreover, three different plant species are present, having different typical characteristics in terms of foliage: lentisk, poplar and oleander. We want to stress that this second study area is particularly challenging due to the poor growth of the plants at the survey epoch.

Both sites have low terrain slopes, allowing considerations in the DTM processing that will be presented later.

2.2 UAV Photogrammetric Surveys

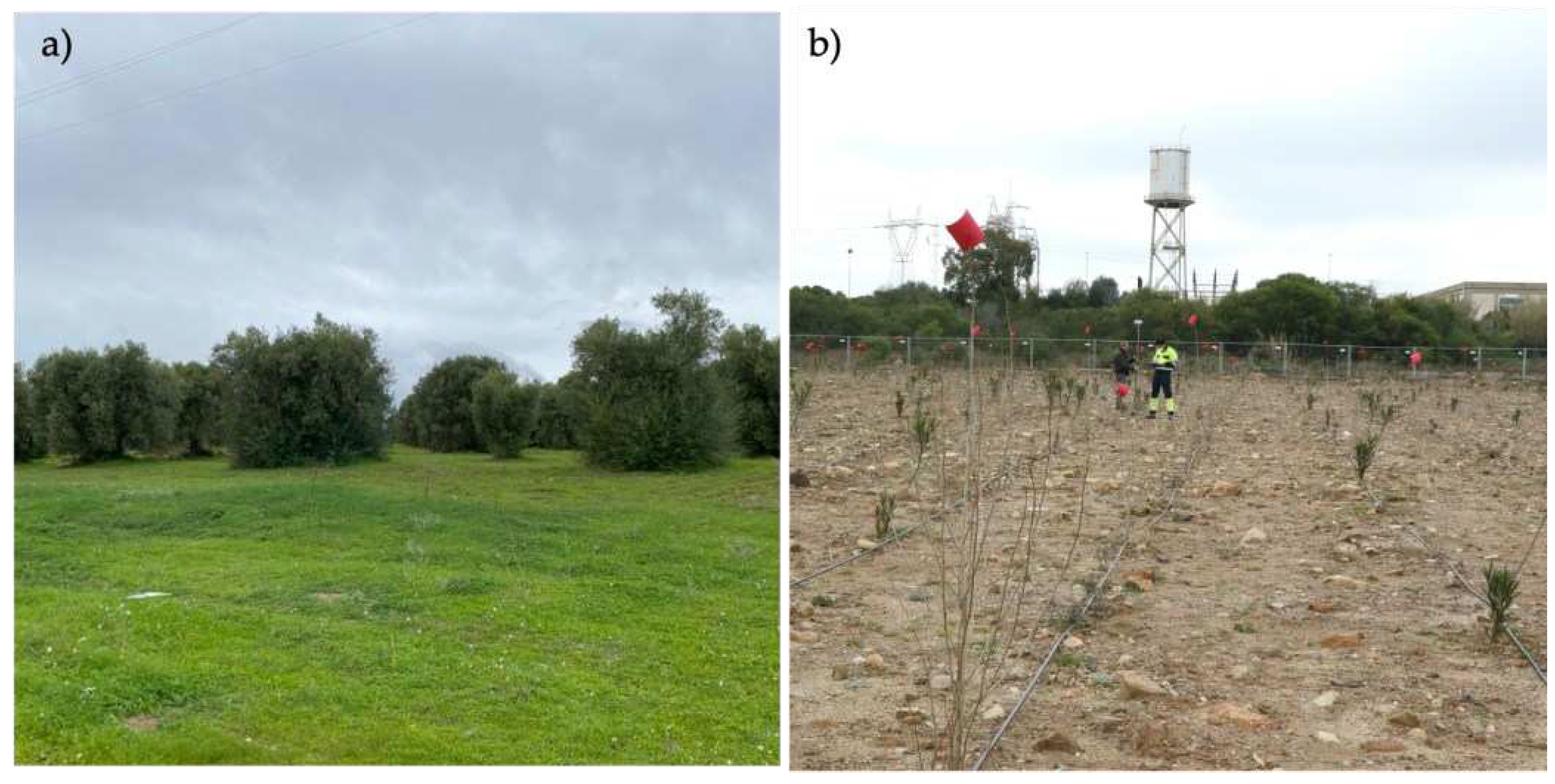

In Area 1, three UAV campaigns have been performed using a very low-cost Mini 3 - DJI drone equipped with an RGB optical camera, during the same day under the same weather conditions (

Figure 2a). Three different flight altitudes have been set, being 50 m, 40 m and 30 m, respectively for flights 1, 2 and 3. Nadiral images have been acquired setting a 12 MP resolution. A total of 6 GCPs have been evenly distributed over the area and surveyed using a single Trimble R8 GNSS receiver operating in NRTK mode for the georeferencing process. The GCPs coordinates in terms of Northing and Easting aligned to the ETRF2000-UTM32N reference system (EPSG: 6707) have been obtained exploiting the Sardinian SARNET network [

34]. Moreover, ellipsoidal heights have been converted into orthometric ones using ConveRgo software [

35] which exploits the ITALGEO05 geoidheight grid (GK2 format) [

36].

Concerning Area 2, the UAV survey has been carried out using a Phantom-DJI drone equipped with RGB sensors, flying 42 m high. The GCPs survey followed the same method as the first site for a total of 7 points (

Figure 2b).

For all the surveys, the GCPs were materialized on the ground using red and white circular targets with a diameter of 20 cm (

Figure 3). The shape and size of the targets have been planned to be visible on images acquired flying up to 80 m high.

Table 1 shows the main parameters of the three UAV campaigns in Area 1 and the flight in Area 2, hereafter called “Flight a”.

2.3 Image processing

Acquired images have been processed using Agisoft Metashape software [

37], which implements the standard Structure from Motion (SfM) algorithm [

38]. SfM is a photogrammetric method for high-resolution topographic reconstructions operating under the same basic theory of stereoscopic photogrammetry. However, they fundamentally differ since, in SfM, the geometry of the scene and the camera’s positions and orientation are automatically solved without exploiting known points [

31]. Thus, the use of multi-image UAV photogrammetry with the SfM approach allows for obtaining accurate metric information with reduced costs and acquisition times.

Conversely, in the stereoscopic photogrammetry workflow, points are solved simultaneously using a highly redundant, iterative bundle adjustment procedure, based on a database of features automatically extracted from a set of multiple images with a high degree of overlap [

39]. The SfM workflow in Metashape consists of the following steps: image import, image alignment, generation of the sparse point cloud, optimization of the image alignment, georeferencing, elaboration of the dense point cloud, DEM and orthophoto generation.

For each UAV dataset, the dense points cloud has been processed by choosing High-quality parameter.

Table 2 reports the number of points in each point cloud and the size of the corresponding file.

The dense point cloud of Flight 1 is shown in

Figure 4, as an example.

2.4 Direct measurements of trees' heights

All the UAV surveys have been coupled with in-field measurements to be used for the validation process. In particular, the height of each single tree has been directly measured using a metric rod. We are aware that this method inevitably suffers from the weather conditions, in particular the wind, the trees' characteristics in terms of foliage and crown’s extension and the subjective nature affecting the observations.

Direct height values have been matched with the trees' positions exploiting a GIS-based procedure, obtaining a complete description of the area in terms of plant row, ID number, plant species (for Area 2), and plant height. We will refer to these values as “direct measurements”.

2.5 GIS-based approach to extract the trees' heights

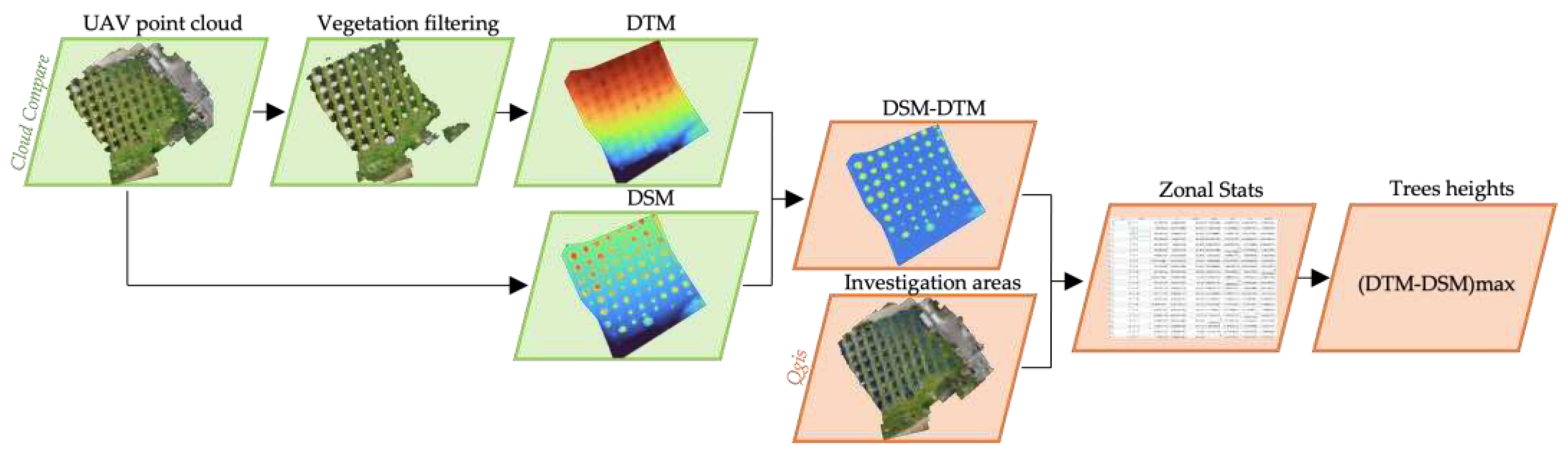

For each photogrammetric survey, the dense point clouds have been interpolated using the CloudCompare software package [

40] obtaining the corresponding DSM, with 20 cm of pixel dimension. Afterwards, the applied methodology aims at untying the trees’ height extraction from the availability of a Digital Terrain Model of the area provided by an external data source, using UAV-derived data to produce also the reference DTM. This choice was possible considering the low slope gradient of the terrain in both the chosen sites. Nevertheless, bearing in mind the different characteristics between the two case studies in terms of trees’ heights and crown extensions, slightly different filtering procedures were used to produce the reference DTM. Indeed, in Area 1 we have mature olive trees with very defined canopies, while in Area 2 we can consider having at least little bushes. For this reason, the common automatic filtering operations, i.e. the inbuilt classification algorithms provided by Agisoft Metashape and CloudCompare software, were not usable on the second site. In Area 1, the automatic filter implemented by CloudCompare software (Cloth Simulation Filter - CSF) has been applied to split the UAV point clouds into “ground” and “off-ground” points. The following parameters have been chosen for the CSF processing: cloth resolution 1.0; max iterations 1000; classification threshold 0.5. The vegetation filtering of the second dataset has been manually carried out by exploiting the open-source LAStool package [

41] implemented in Qgis software [

42]. A clipping operation of the point cloud has been performed, leading to the removal of the crowns from the original point cloud. After the filtering step, the DTMs of the two sites were generated by interpolating the ground points using the

Rasterize tool in CloudCompare, with a 20cm pixel dimension.

Then, the maps of height variation have been computed as the differences between each DSM and the related DTM:

where the result represents the Canopy Height Model (CHM) [

28]. Finally, CHM maps have been analysed using a local maxima approach. In particular, the maximum values of the CHM within individual trees’ investigation areas have been identified using the

Zonal Statistic tool in Qgis software. Retrieved values are the candidates to correspond to trees’ tops, and have been selected as UAV-derived trees’ heights.

Figure 5 graphically shows the complete workflow to extract the trees’ heights.

3. Results

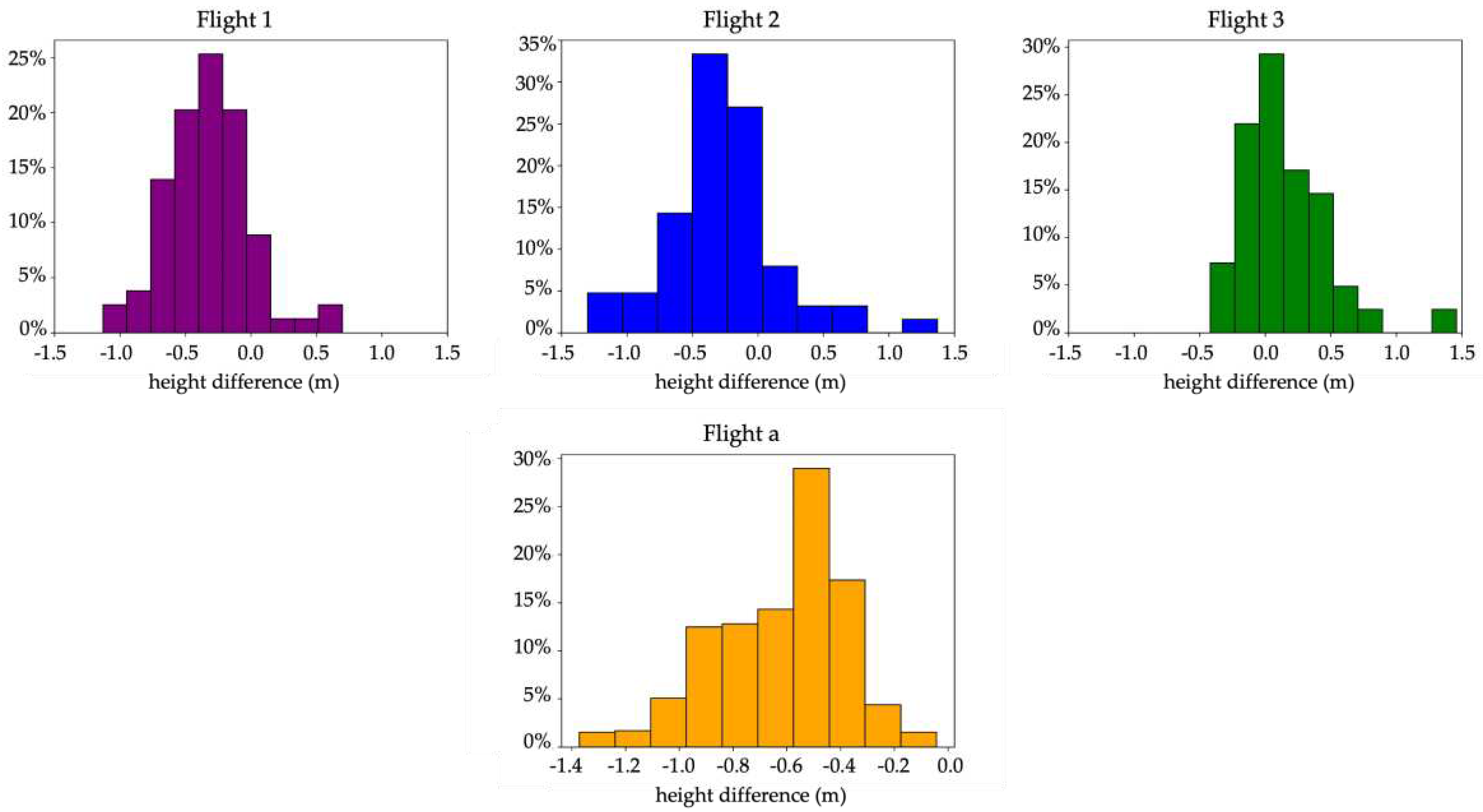

Extracted values of trees’ heights have been analysed and compared with the direct measurements separately for the two study areas. In particular, differences have been calculated using the direct measurements as reference values and the main statistics have been computed (

Table 3).

Concerning Area 1, results are within the expected method’s accuracy obtained for higher trees or in forestry contexts, since the mean absolute values of the differences range between 14 cm and 34 cm. As expected, the lower the flying altitude, i.e. the lower the GSD, the better coherence we found with the direct measurements, from Flight 1 to 3. In particular, Flight 3 (30 m of flight altitude) shows very promising results, with 90% of the differences below 50 cm. Nevertheless, a difference between the three flights arises, since the former tend to underestimate the trees' heights, while the third slightly overestimates their values (considering the direct measurements as a reference in the comparison). This fact is also evident from the frequency distribution histograms of the differences in

Figure 6a and should be further investigated to understand possible sources of this behaviour. Although Flight 3 involved a slightly smaller area compared with the previous ones, with a total of 41 identified trees, we can observe an almost normal distribution of the differences close to zero-centred.

The situation is different in Area 2, where

Table 3 and

Figure 6b show that values are entirely shifted toward the negatives, with a mean value of about minus 60 cm, i.e. nearly 30 cm more than the highest flight on Area 1 (Flight 1). This fact was expected and mainly related to the low heights of the trees, with different impacts on the whole procedure. As a first aspect, independently of the following elaborations, it is difficult to obtain a good representation of very low trees from the photogrammetric dense point cloud, considering the limited extension of the canopies and the foliage. Secondly, low heights negatively impact vegetation filtering which cannot exploit automatic tools but rather requires a manual procedure. As a final point, comparing DSMs and DTMs, both of which derive from interpolation processes entraining sources of uncertainty, requires proper accuracies to enable small variations to be detected. Reasonably, these aspects mutually influence each other, as well as the plants’ heights that are both the origin of the problem and the reason which makes the method unusable in this context. Indeed, even if the direct measurements are known to have accuracies lower than the cm-level, the obtained differences are comparable to or sometimes higher than the actual trees’ heights in the area.

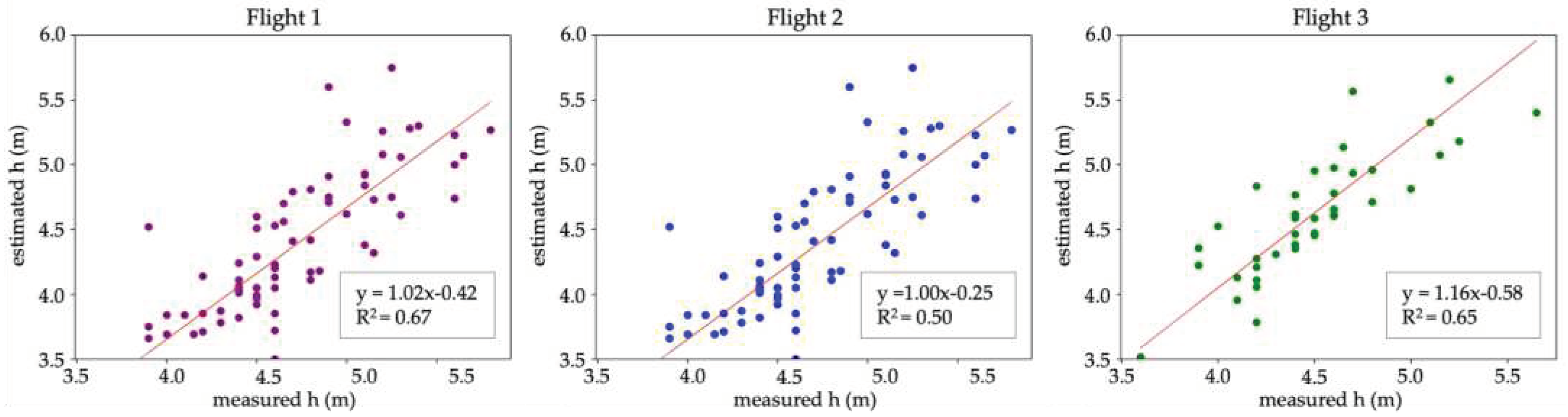

Figure 7 shows the relation between estimated and measured trees’ heights for the three flights performed in Area 1, in terms of linear regression lines. Overall we can say that the models, i.e. the estimated values, are pretty able to replicate the observed samples. Flight 1 and Flight 3 exhibit similar coefficients of determination (R

2=0.67; R

2=0.65), whereas the value is slightly lower for Flight 2 (R

2=0.50).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

To date, the monitoring and management of agricultural lands is a topic of high interest in the context of environmental protection and precision agriculture (PA). Indeed, there is a growing development of related research also due to the European Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) [

43,

44].

This study focuses on the use of photogrammetric data to retrieve dimensional parameters of trees. Preliminary results of the trees’ height estimation from low-cost imagery acquired by low-cost UAV platforms are presented. Two study areas have been chosen in Sardinia, Italy, named “Area 1” and “Area 2”, with extensions of 1.2 ha and 0.6 ha, respectively. The first site is an olive grove where trees heights range between 3 and 6 m, individual trees are located along separated rows and trees crowns are pretty wide, representing ideal conditions for the analysis. On the other hand, Area 2 was chosen to test the applicability of the same methodology in a challenging context. Indeed, in the second scenario, we deal with very young trees (heights ranging between 10 cm and 140 cm), sometimes with leaf-off conditions. Three survey campaigns have been performed in Area 1 flying at different altitudes (30 m, 40 m and 50 m), while only one UAV flight is available as a test case in Area 2 (42 m of flight altitude). In both cases, the Digital Surface Models have been generated by exploiting the standard SfM approach implemented in Agisoft Metashape software. The reference DTMs have been produced starting from the dense point clouds, applying automatic filtering procedures or implementing a manual classification of ground and vegetation. The Canopy Height Models obtained as differences between each DSM and the related DTM have been analysed using a local maxima approach choosing ad hoc windows as individual investigation areas around each tree. Thus, the candidate trees’ tops have been identified and the related heights have been considered for the analysis. In-field measurements have been performed concurrently with each UAV survey using a metric rod and used for the validation process. In particular, the UAV-derived heights have been compared with the so-called “direct measurements” for each tree in the two study areas.

In Area 1, the comparison with the direct measurements provides promising results, with mean residuals ranging between 14 and 34 cm. The best values are related to the campaign with 30 m of flying altitude, proving that the images’ resolution (GSD) is a fundamental parameter to obtain higher quality in the photogrammetric products. Moreover, all three flights in Area 1 have 50% of the differences lower than 38 cm and the frequency distribution histograms of the differences follow almost normal distributions. However, results in the first site exhibit different behaviours since Flight 1 and 2 generally underestimate the trees' heights, while Flight 3 tends to overestimate. This fact requires further investigation which will be developed in future studies. Considering the mean heights of the trees in Area 1, the obtained results confirm the applicability of the procedure to estimate the “absolute” trees’ heights. Therefore, the implementation of the same methodology to multitemporal datasets acquired at low-flight altitudes could allow even the determination of trees’ rate of growth over medium-long temporal scales. This becomes a key data in the analysis of phytoremediation processes, to assess the plant’s health and the effectiveness of the chosen restoration method.

Results in the first site are also coherent with the outcomes of a similar study by Zarco-Tejada et al. [

25], where they obtained an RMSE of 35 cm for trees’ heights ranging between 1.16 m and 4.38 m. Concerning the coefficients of determination related to the trees’ height estimation, they obtained a higher value (R

2 = 0.83 versus our R

2 = 0.67) which could be related to the difference in the measurements used for the validation. Moreover, Birdal et al. [

23] found an RMSE equal to 28 cm, which is also consistent with our findings.

As expected, the context in Area 2 entailed different conclusions, since the mean value of the differences is about -60 cm, i.e. sometimes higher than the actual trees heights in the area. Even if the flight altitude was comparable with the one of Flight 1, the mean differences are 30 cm higher. This fact is reasonably not only due to the altitude rather than to the “absolute” height of the individual trees that made the whole procedure very challenging. We identified three main aspects impacting this outcome: i) goodness of the photogrammetric dense cloud in representing low trees; ii) manual vegetation filtering; iii) impact of the interpolation in the DSM and DTM generation and differencing. Although these conditions make the methodology not usable, bearing in mind the presence of different plant species in Area 2, we tried to relate the results with this parameter. However, no evidence has arisen, unless a slightly better behaviour of the lentisk compared with the other two species (poplar, oleander), but probably reliable results would require higher plants to allow their differentiation by foliage and crown extensions.

In conclusion, the analysis presented in this paper confirms the suitability of UAV photogrammetric data acquired from low-cost instruments for trees’ height extraction. This fact represents a benefit for those involved in the agricultural field since the usage of such equipment is easily accessible even for non-specialist users. The proposed methodology is based on a standard photogrammetric processing coupled with a GIS-based analysis. The adopted workflow is straightforward and mainly based on open-source software, such as CloudCompare and Qgis, making again the whole procedure very flexible.

Promising results have been obtained for trees 3 to 6 meters tall, whereas the application of the same methodology in a low trees’ context requires further investigations. However, we want again to stress the complexity of the context chosen in the case of Area 2, where trees’ heights are always below 1.5 m and the foliage is poorly grown. For this reason, a further test may involve an intermediate case study which can be found in Area 2 after the plants growth. In addition, a possible source of accuracy improvement has been identified in the use of oblique images, rather than only nadiral ones, as suggested in [

23,

26].

Finally, it should be highlighted that this research is framed in the context of a wider project, “Tecnologie di CARatterizzazione Monitoraggio e Analisi per il ripristino e la bonifica (CARMA)”, involving both geomatics and geophysical data [

45]. Thus, the presented study is the first step to reaching the Project’s goals of integrating geometric, biochemical and geophysical data in a single workflow to assess the trees’ health condition and rates of growth. Considering this multidisciplinary context, future developments may involve the employment of more advanced technologies, such as LiDAR, to improve the accuracy, especially in areas with low trees.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.V. and E.V.; methodology, G.V. and E.V.; software, E.V.; resources, G.V.; writing—review and editing, E.V. and G.V.; supervision, G.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Pasquale Carta, Andrea Dessì, Sergio De Montis and Federico Secchi for their contribution during the field surveys.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ammoniaci, M.; Kartsiotis, S.-P.; Perria, R.; Storchi, P. State of the Art of Monitoring Technologies and Data Processing for Precision Viticulture. Agriculture 2021, 11, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliai, A.; Ammoniaci, M.; Sarri, D.; Lisci, R.; Perria, R.; Vieri, M.; D’Arcangelo, M.E.M.; Storchi, P.; Kartsiotis, S.-P. Comparison of Aerial and Ground 3D Point Clouds for Canopy Size Assessment in Precision Viticulture. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crookston, R.K. A top 10 list of developments and issue impacting crop management and ecology during the past 50 years. Crop Science 2006, 46, 2253–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casa, R. Agricoltura di precisione. Metodi e tecnologie per migliorare l’efficienza e la sostenibilità dei sistemi colturali. Edagricole New Bus. Media 2016.

- Vacca, G.; Quaquero, E. BIM-3D GIS: an integrated system for the knowledge process of the buildings. Journal of Spatial Science 2020, 65, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobart, M.; Pflanz, M.; Weltzien, C.; Schirrmann, M. Growth height determination of tree walls for precise monitoring in apple fruit production using UAV photogrammetry. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaru, N.; Rossi, M.; Vacca, G.; Vignoli, G. Spreading of Localized Information across an Entire 3D Electrical Resistivity Volume via Constrained EMI Inversion Based on a Realistic Prior Distribution. Remote Sensing 2022, 15, 3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Dugo, V. Using high-resolution UAV thermal imagery to assess the variability in the water status of five fruit tree species within a commercial orchard. Precision Agriculture 2013, 14, 660–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchi, E.; Tavasci, L.; De Nigris, N.; Gandolfi, S. GNSS and photogrammetric UAV derived data for coastal monitoring: A case of study in Emilia-Romagna, Italy. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2021, 9, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.L.; Tian, W.T.; Yin, J. A Review of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Low-Altitude Remote Sensing (UAV-LARS) Use in Agricultural Monitoring in China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, L. Assessing the stability of canopy maps produced from UAV-LiDAR data. IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium-IGARSS. IEEE, 2013, pp. 3879–3882.

- Wallace, L.; Lucieer, A.; Malenovský, Z.; Turner, D.; Vopěnka, P. Assessment of forest structure using two UAV techniques: A comparison of airborne laser scanning and structure from motion (SfM) point clouds. Forests 2016, 7, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argamosa, R. J. L. Fully automated GIS-based individual tree crown delineation based on curvature values from a lidar derived canopy height model in a coniferous plantation. Int. Arch. Photogramm, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2016, 41, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beloiu, M.; Heinzmann, L.; Rehush, N.; Gessler, A.; Griess, V. C. Individual Tree-Crown Detection and Species Identification in Heterogeneous Forests Using Aerial RGB Imagery and Deep Learning. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiede, D.; Hochleitner, G.; Blaschke, T. A full GIS-based workflow for tree identification and tree crown delineation using laser scanning. ISPRS Workshop CMRT 2005, 5, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Latella, M.; Sola, F.; Camporeale, C. A density-based algorithm for the detection of individual trees from LiDAR data. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velusamy, P.; Rajendran, S.; Mahendran, R.K.; Naseer, S.; Shafiq, M.; Choi, J.-G. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) in Precision Agriculture: Applications and Challenges. Energies 2022, 15, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, S.; Sanders, T. G.; Mund, J. P.; Greve, K. UAV-based photogrammetric tree height measurement for intensive forest monitoring. Remote sensing 2019, 11, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameyama, S. and Sugiura, K. Estimating tree height and volume using unmanned aerial vehicle photography and SfM technology, with verification of result accuracy. Drones 2020, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtseven, H.; Akgul, M.; Coban, S.; Gulci, S. Determination and accuracy analysis of individual tree crown parameters using UAV based imagery and OBIA techniques. Measurement 2019, 145, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komárek, J.; Klápště, P.; Hrach, K.; Klouček, T. The potential of widespread UAV cameras in the identification of conifers and the delineation of their crowns. Forests 2022, 13, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, L.; Lindberg, E.; Holmgren, J. Towards low vegetation identification: A new method for tree crown segmentation from LiDAR data based on a symmetrical structure detection algorithm (SSD). Remote Sensing of Environment 2022, 270, 112857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdal, A. C.; Avdan, U.; Türk, T. Estimating tree heights with images from an unmanned aerial vehicle. Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk 2017, 8, 1144–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudrý, V.; Klápště, P.; Fogl, M.; Gdulová, K.; Barták, V.; Urban, R. Assessment of LiDAR ground filtering algorithms for determining ground surface of non-natural terrain overgrown with forest and steppe vegetation. Measurement 2020, 150, 107047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarco-Tejada, P. J.; Diaz-Varela, R.; Angileri, V.; Loudjani, P. Tree height quantification using very high resolution imagery acquired from an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) and automatic 3D photo-reconstruction methods. European journal of agronomy 2014, 55, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourreza, M.; Moradi, F.; Khosravi, M.; Deljouei, A.; Vanderhoof, M. K. GCPs-free photogrammetry for estimating tree height and crown diameter in Arizona Cypress plantation using UAV-mounted GNSS RTK. Forests 2022, 13, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülci, S. The determination of some stand parameters using SfM-based spatial 3D point cloud in forestry studies: an analysis of data production in pure coniferous young forest stands. Environmental monitoring and assessment 2019, 191, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, M.; Silva, C.A.; Klauberg, C.; Jat, P.; Catts, G.; Cardil, A.; Hudak, A.T.; Dia, M. Individual Tree Detection from Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Derived Canopy Height Model in an Open Canopy Mixed Conifer Forest. Forests 2017, 8, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearse, G. D.; Dash, J. P.; Persson, H. J.; Watt, M. S. Comparison of high-density LiDAR and satellite photogrammetry for forest inventory. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2018, 142, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcore, E.; Latella, M. Riparian ecosystems mapping at fine scale: a density approach based on multi-temporal UAV photogrammetric point clouds. Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation 2022, 8, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacca, G. Estimating tree height using low-cost UAV, Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2023, 48, 381–386. [Google Scholar]

- Naveed, M. Morphological and Structural Responses of Albizia lebbeck to Different Lead and Nickel Stress Levels. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, K.; Tian, C.; Mai, W. Progress of Euhalophyte Adaptation to Arid Areas to Remediate Salinized Soil. Agriculture 2023, 13, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnet, Web Server della Rete di Stazioni Permanenti della Sardegna. Available online: http://www.sarnet.it/servizi.html (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Centro Interregionale per I Sistemi Informatici Geografici e Statistici In Liquidazione. Trasformazioni di coordinate – Il software ConveRgo. Available online: https://www.cisis.it/?page_id=3214 (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- International Service for the Geoid (ISG). Italy (ITALGEO05). Available online: https://www.isgeoid.polimi.it/Geoid/Europe/Italy/italgeo05_g.html (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- AgiSoft PhotoScan Standard (Version 1.2.6) (Software). (2016*). Retrieved from http://www.agisoft.com/downloads/installer/.

- Turner, D.; Lucieer, A.; Watson, C. An automated technique for generating georectified mosaics from ultra-high resolution unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) imagery, based on structure from motion (SfM) point clouds. Remote sensing 2012, 4, 1392–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeliski, R. Computer vision: algorithms and applications. Springer Nature 2022.

- CloudCompare. Available online: https://www.danielgm.net/cc/ (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Isenburg, M. LAStools - efficient LiDAR processing software (version 141017, unlicensed), available at: http://rapidlasso.com/LAStools.

- Qgis Documentation. Available online: https://docs.qgis.org/2.8/en/ (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- European Commission. Agriculture and rural development, Common Agricultural Policy. 1. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/common-agricultural-policy_en#:~:text=The%20CAP%20is%20a%20partnership,27%20commenced%201%20January%202023 (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Alexandratos, N. and Bruinsma, J. World agriculture towards 2030/2050: the 2012 revision. ESA Working paper 2012, 12-03. Rome, FAO, 2012.

- Ecoserdiana. Progetto di Ricerca su Tecnologie di CARatterizzazione Monitoraggio e Analisi per il ripristino e la bonifica (CARMA) - Fondo Europeo di Sviluppo Regionale - Por Fesr Sardegna 2014-2020, available at: https://www.ecoserdiana.com/servizi/progetti-di-ricerca.html.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).