1. Introduction

A burn scar, categorized as a hypertrophic scar, can lead to significant clinical manifestations, discomfort, and the development of post-burn scar (PBS) syndrome [

1,

2]. PBS syndrome affects as many as 77% of burn injury patients, increasing their likelihood of experiencing pain and pruritus (itching) [

1]. These symptoms arise from the hypertrophic and inflammatory changes in the scar tissue and often exhibit limited responsiveness to conventional treatments [

2]. Additionally, patients with PBS syndrome commonly report poor sleep quality (insomnia), possibly linked to heightened rates of comorbid posttraumatic stress syndrome and pruritus [

2].

Laser therapy and surgery are effective treatments for burn scars, but they are often delayed until the scar stabilizes, particularly for major burn scars. This delay may lead to more severe PBS syndrome symptoms and scar conditions [

2,

3,

4]. Rehabilitation is vital for burn scar contractures, but it usually can’t fully relieve PBS syndrome symptoms [

2]. Complementary therapies like massage, hypnosis, music therapy, and aromatherapy show promise in PBS syndrome treatment [

6]. Acupuncture, utilizing the meridian system, is another successful complementary method for managing pain related to burn scars [

2,

7].

Recently, interest in auriculotherapy has grown in clinical and experimental research, some studies have shown the effect of auriculotherapy via neurostimulation [

8]. For example, Shiozawa et al. (2014) demonstrated how electrical stimulation of cranial nerves via the external ear can harness brain plasticity for therapeutic purposes. Mercante et al. (2018) introduced the concept of auricular neuromodulation (AN), examining the neuroanatomical and neurochemical properties of the vagus and trigeminal nerves in the ear and their connections to specific CNS regions [

9]. Various studies have drawn parallels between noninvasive and invasive vagus nerve stimulation. Niemtzow’s "battlefield acupuncture" (BFA) aimed to influence central pain control through somatotopic representation in the ear, though the evidence is limited [

10,

11,

12].

In 2017, the Singapore Symposium on auriculotherapy advanced our neurophysiological understanding, connecting clinical auriculotherapy applications to the auricular branch of the vagus nerve. This implies that the auricles could be an affordable target for noninvasive techniques to modulate CNS functions. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated significant improvements in conditions like chronic pain, osteoarthritis, poststroke syndrome, and drug abuse through auriculotherapy [

13,

14]. Magnetic auriculotherapy has also proven effective in reducing pain and distress in neonates in intensive care units [

15]. Despite acupuncture’s global acceptance, it remains outside mainstream practice, partially due to needle phobia. Consequently, alternative auriculotherapy methods, such as laser light, self-administered auricular acupressure (AA), and magnetic beads, have been developed for clinical use [

13].

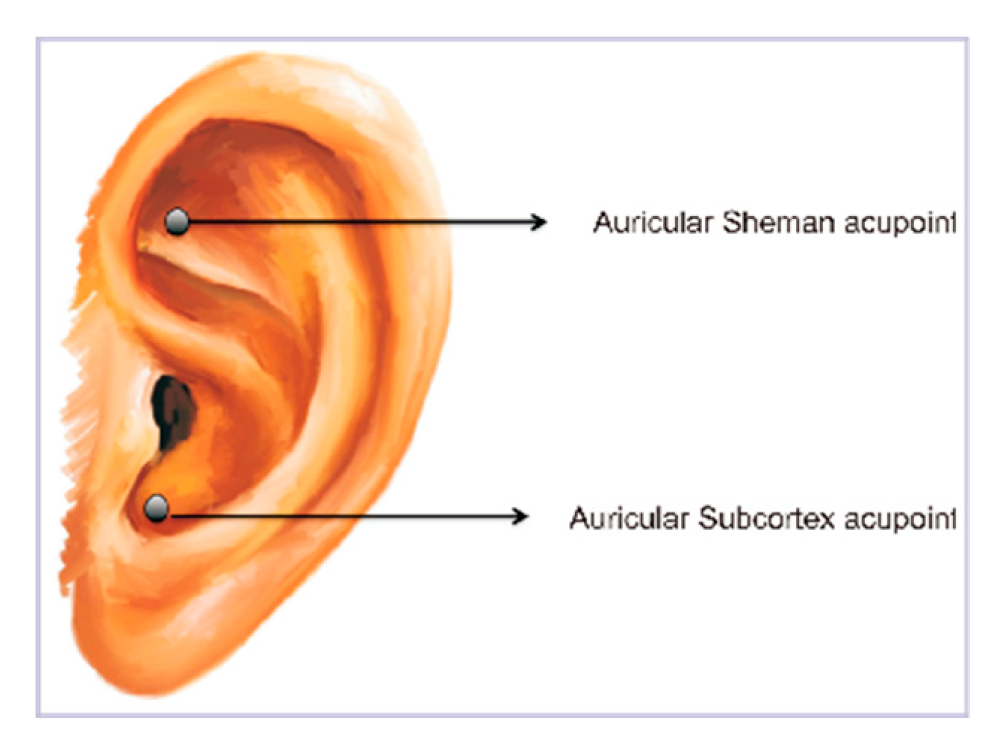

In our previous prospective, single-arm study aimed to evaluate auriculotherapy’s potential in alleviating PBS syndrome symptoms in individuals with major burn injuries (> 20% TBSA) without relying on pharmaceuticals. To address the unique challenges of major burn scars, we utilized self-massage magnet beads on specific auricular acupoints, Shenmen and Subcortex, both acupoints are recognized for their influence on the autonomic nervous system, particularly the parasympathetic branch [

14,

16], which may relieve PBS symptoms like pain and itching. The results revealed a significant reduction in clinical symptoms post-intervention, although the effect was not sustained. Notably, among patients with abnormal HRV (SD < 40), treatment led to a significant decrease in normal-to-normal heart rate interval, heart rate analysis abnormalities, and very low-frequency heart rate [

17].

Heart rate variability (HRV) analysis involves the examination of the variations in time between successive heartbeats. HRV parameters provide insights into the balance and activity of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), particularly the interplay between the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches [

18].

While HRV is commonly utilized to gauge overall ANS function in psychiatric patients [

19,

20], here we broadened its application to encompass patients afflicted by significant burn scars in this study. The functionality of both the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions of the ANS can influence factors like sleepiness, pain threshold, and itching. HRV was employed to assess how auriculotherapy impacts the ANS and was quantified through time domain and frequency domain parameters.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient selection

The participants included in this study are the same as those in our previous study [

17]. All participants were survivors of the Formosa Color Dust Explosion in Taiwan [

11]. The selection criteria were as follows: 1) ages between 19 and 35 years, 2) Total Burn Scar Area (TBSA) greater than 20%, 3) scars that had reached a stable condition for over six months, 4) stable physical condition with ongoing rehabilitation, 5) no central nervous system (CNS) injuries or coexisting medical conditions, and 6) no recent laser treatments or surgical procedures within the past three months.

Exclusions encompassed individuals with burn scars covering less than 20% of their TBSA, those dealing with alcoholism, neurological impairments, pre-existing medical conditions before the burn injury, or major limb amputation due to the burn. Participants who had undergone laser treatment or surgery in the preceding three months were also excluded. Patients taking psychiatric medications or sleep aids before their burn injury and those presently in an unstable medical condition were also excluded. Additionally, individuals unwilling to complete questionnaires, adhere to treatment protocols, or who had previously received treatment(s) other than auricular-stimulating therapy for Post-Burn Scar (PBS) syndrome were excluded. Also, patients who had undergone major limb amputation as a result of their burn injury were not included in this study.

Between May 2016 and May 2017, 62 patients were recruited. Of these, only 31 met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled. Among the 31, one female participant withdrew the day following auricular magnetic bead treatment due to intolerable pain from her burn scars. This left a final cohort of 30 individuals for the study.

This study was approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) at both study sites: The Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital IRB in Taipei, Taiwan (IRB No. 20160201R), and the Sunshine Social Welfare Foundation IRB (IRB No. SU105001, 10491 3F, No.91,

Section 3, Nanjing East Road, Zhongshan District, Taipei City, Taiwan). The same study protocol was followed at both study sites.

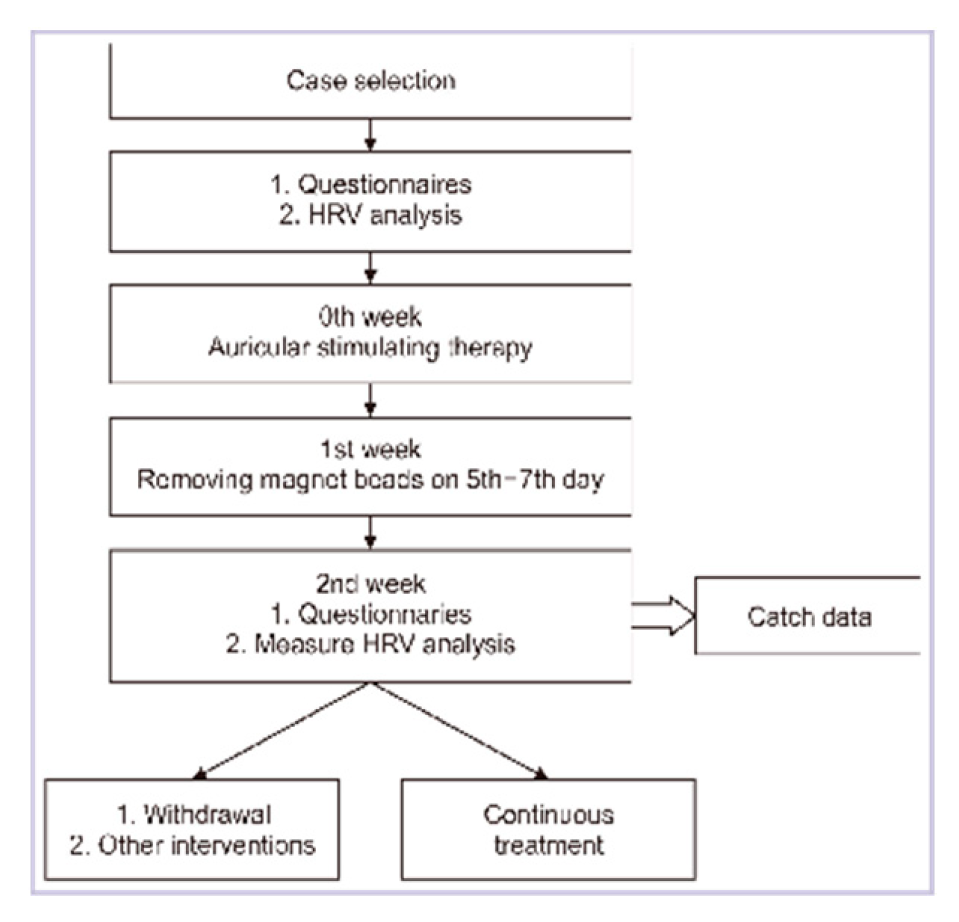

2.2. Treatment protocol

The treatment tool was largely as described previously [

17]. Briefly, the whole duration of the study was 29 days, and the intervals were a one-week intervention and a one-week break for two courses. The preinterventional data were collected on the first day, and the postinterventional data were collected on the fifteenth and twenty-ninth experimental days separately.

Before the treatment commenced, patients who had been enrolled filled out clinical variable questionnaires and underwent HRV testing during their initial evaluation. Magnetic beads were placed on the auricular Shenmen and Subcortex acupoints of one ear (as illustrated in

Figure 1) using an acupoint detection pen. The treatment procedure consisted of self-administered massages five times a day, and both magnetic beads were removed on the eighth day of the experiment. Subsequently, patients underwent a second evaluation as part of the post-intervention assessment and then commenced the second treatment course. Each patient, in total, received two courses of treatment and underwent three evaluations.

Heart rate variability (HRV) assessment. HRV was used to evaluate the influence of auriculotherapy on the ANS. The general status of autonomic system functioning can be quantified via standard deviations from the normal-to-normal heart rate interval (SD), total power of autonomic system activity (TP), High Frequency (HF), Normalized High-Frequency power (HFN), Low Frequency (LF), Normalized Low-Frequency power (LFN), Very Low hear rate intervals (VL), and L/H ratio. In general concept, SD and TP mean the total activity of autonomic system, LFN stands for the activity of sympathetic system, and HFN relates to that of the parasympathetic system.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The results were analyzed by paired-samples t-tests, simple linear analysis, and linear regression analysis in SPSS (22, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A p-value (or p-value) less than 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

3. Results

Our previous study has demonstrated that a single course of auriculotherapy ameliorated symptoms associated with PBS syndrome, including procedure-related pain, background pain, itchiness, and sleep quality (p < 0.05 for all categories) (n = 30).

Analysis of heart rate variability (HRV) data was applied to evaluate autonomic system functionality before and after the administration of auriculotherapy. The paired-sample t-test conducted for the pre- and post-auriculotherapy analysis revealed a significant correlation between Pre-SD and Post-SD (P = 0.017). The mean Pre-SD is 39.39 with a standard deviation of 17.348, while the mean Post-SD is 43.32 with a standard deviation of 14.7. Similarly, there were significant correlations observed for Pre-TP vs. Post-TP (P = 0.014) and Pre-HF vs. Post-HF (P = 0.04). The mean Pre-TP is 1534.68 with a standard deviation of 1405.125, and the mean Post-TP is 1722.24 with a standard deviation of 1046.817. The mean Pre-HF is 321.04 with a standard deviation of 364.128, and the mean Post-HF is 354.64 with a standard deviation of 223.610.

On the other hand, correlations were not significant for Pre-VL vs. Post-VL (P = 0.072), Pre-L/H vs. Post-L/H (P = 0.368), Pre-LF vs. Post-LF (P = 0.514), Pre-LFN vs. Post-LFN (P = 0.229), Pre-HFN vs. Post-HFN (P = 0.478).

Simple linear regression analysis was utilized to assess the relationship between TBSA and various ANS variables, the results indicate a significant correlation between TSBA and pre-SD (P = 0.042), with each one-unit increase in TBSA, there is a reduction of 0.437 units in Pre-SD. A trend of correlation between TBSA and pre-VL was also detected (P = 0.054), albeit at the edge of significance, with each one-unit increase in TBSA corresponding to a decrease of 13.931 units in Pre-VL.

Conversely, TBSA does not exhibit significant correlations with post-SD (P = 0.866), pre-TP (P = 0.065), post-TP (P = 0.949), post-VL (P = 0.957), pre-L/H (P = 0.297), post-L/H (P = 0.661), pre-LF (P = 0.905), post-LF (P = 0.204), pre-LFN (P = 0.582), post-LFN (P = 0.766), pre-HF (P = 0.337), post-HF (P = 0.236), pre-HFN (P = 0.174), and post-HFN (P = 0.760).

Taken together, we expanded HRV analysis before and after auriculotherapy of patients with major burn scars and found significant and negative correlations between TBSA and pre-SD prior to auriculotherapy.

4. Conclusions

The findings in this study suggest that auriculotherapy had a significant impact on specific parameters related to autonomic nervous system activity, while others showed no significant change. For example, Parameters such as Pre-SD, Pre-TP, and Pre-HF showed significant correlations between pre- and post-treatment measurements, indicating a notable relationship. Linear regression analysis between TBSA and different HRV variables revealed significant correlation observed is between TBSA and Pre-SD. For every unit increase in TBSA, there is a decrease in Pre-SD. However, the clinical significance of this correlation would need further investigation and interpretation.

5. Discussion

The observation that in patients with significant burn scars, TBSA is negatively correlated with SD before auriculotherapy (pre-SD) may be explained as follows. A larger TBSA indicates a more extensive burn injury and might correlate with increased physical trauma, pain, and psychological stress. These factors can influence ANS functioning. A higher SD (sympathetic activity) indicates greater heart rate variability, which is generally associated with better autonomic health and adaptability [

21]. Negative correlation between TBSA and pre-SD suggests that the extent of the burn scar might contribute to autonomic dysregulation, which may result in decreased heart rate variability and a smaller SDNN before treatment.

The intention behind using auriculotherapy is to modulate the autonomic balance and improve overall well-being. The loss of negative correlation between TBSA and post-SD suggests that auriculotherapy has some impact on sympathetic activity. However, no significant correlations was found between TBSA and other ANS-related HRV variables, both before and after auriculotherapy. These variables include parasympathetic activity (Pre-VL), normalized low-frequency power (Pre-LFN), high-frequency power (Pre-HF), and others. The lack of significant correlations in these variables suggests that TBSA may not strongly influence these aspects of ANS function. Taken together, the current study did not conclusively demonstrate that auriculotherapy fully restores ANS function.

Our result unraveled a negative, albeit non-significant, correlation between TBSA and pre-VL in patients with significant burn scar. The extent of burn injuries might contribute to autonomic dysregulation. The LF component of heart rate variability (HRV) is associated with both sympathetic and parasympathetic activity, with sympathetic modulation being dominant, and the very low frequency (VL) within the LF range is even slower oscillations of heart rate and is often linked to mechanisms involving blood pressure regulation, hormonal influences, and vasomotor control [

22]. This stress derived from large TBSA could lead to an autonomic imbalance toward sympathetic dominance, as partly revealed as decreased very low frequency oscillations within the LF range (pre-VL). Auriculotherapy could potentially influence the autonomic modulation of heart rate, including the very low frequency component, which is supported by our finding that no negative correlation was found between TBSA and post-VL in patients with major burn scars.

In summary, albeit lack of distinct HRV data results which might stem from the synchronized rise or fall in overall ANS activity following significant burns. The relationship between TBSA and HRV parameters highlights the potential impact of burn injuries on autonomic function. The findings suggest that burn scar extent might contribute to autonomic dysregulation, leading to decreased heart rate variability. In this study, subsequent application of auriculotherapy addressed this imbalance and sped restoration of ANS function more quickly and improved clinical scar syndromes. The findings from this study can provide valuable insights to guide future approaches in patient treatments.

Moreover, while not explicitly documented, it is apparent that patients undergo a noteworthy improvement in sleep quality following the treatment. This constructive change can also provide valuable perspectives for shaping forthcoming therapeutic strategies.

Limitations and Strengths of this study

This study is constrained by a limited number of patients and the challenge of implementing a fully double-blind setup due to treatment restrictions related to scar management. Nevertheless, it introduces a fresh perspective by employing HRV changes in the context of burn scar treatment.

The key advantage of this study lies in the uniform age distribution of all patients, who experienced injuries at the same time. Additionally, the interventions targeting HRV were applied uniformly across the cohort. Such a harmonized and synchronous approach is relatively uncommon in previous research, making it a notable strength of this study.

To determine whether auriculotherapy effectively restores ANS function, further research is needed. The current results provide some hints that it may have an impact on sympathetic activity, but the overall function of the autonomic nervous system is complex and involves various factors. Larger, controlled studies and additional investigations into the mechanisms of auriculotherapy are required to draw more definitive conclusions regarding its effects on ANS function.

Table 1.

Pre and Post-auriculotherapy Analysis (Paired Sample T-Test).

Table 1.

Pre and Post-auriculotherapy Analysis (Paired Sample T-Test).

| I. Paired sample statistics |

|

|

| Pair |

Mean |

N |

SD |

SEM |

| pre-SD |

39.4 |

38 |

17.35 |

2.81 |

| post-SD |

43.3 |

38 |

14.78 |

2.40 |

| pre-TP |

1534.7 |

38 |

1405.13 |

227.94 |

| post-TP |

1722.2 |

38 |

1046.82 |

169.82 |

| pre-VL |

635.2 |

38 |

582.22 |

94.45 |

| post-VL |

722.7 |

38 |

460.33 |

74.68 |

| pre-L/H |

1.3 |

37 |

1.09 |

0.18 |

| post-L/H |

1.3 |

37 |

0.89 |

0.15 |

| pre-LF |

396.6 |

27 |

397.12 |

76.43 |

| post-LF |

471.9 |

27 |

414.77 |

79.82 |

| pre-LFN |

51.7 |

25 |

17.14 |

3.43 |

| post-LFN |

68.9 |

25 |

102.13 |

20.43 |

| pre-HF |

321.0 |

25 |

364.13 |

72.83 |

| post-HF |

354.6 |

25 |

223.61 |

44.72 |

| pre-HFN |

40.4 |

24 |

14.90 |

3.04 |

| post-HFN |

38.8 |

24 |

10.77 |

2.20 |

Table 2.

Pre and Post-auriculotherapy Analysis (Paird Sample Correlation Test).

Table 2.

Pre and Post-auriculotherapy Analysis (Paird Sample Correlation Test).

| Pair |

Number of Pairs |

Correlation |

p Value |

| pre-SD vs post-SD |

38 |

0.384 |

*0.017 |

| pre-TP vs post-TP |

38 |

0.394 |

*0.014 |

| pre-VL vs post-VL |

38 |

0.295 |

0.072 |

| pre-L/H vs post-L/H |

37 |

0.152 |

0.368 |

| pre-LF vs post-LF |

27 |

0.131 |

0.514 |

| pre-LFN vs post-LFN |

25 |

0.249 |

0.229 |

| pre-HF vs post-HF |

25 |

0.413 |

*0.040 |

| pre-HFN vs post-HFN |

24 |

-0.152 |

0.478 |

Table 3.

Pre and Post-auriculotherapy Analysis (Paired Sample T-Test).

Table 3.

Pre and Post-auriculotherapy Analysis (Paired Sample T-Test).

| Pair |

Paired Variable Difference |

95% CI |

t |

df |

p value (2-tailed) |

| Mean |

SD |

SEM |

lower bound |

upper bound |

| pre-SD vs post-SD |

-3.92 |

17.96 |

2.91 |

-9.82 |

1.98 |

-1.35 |

37 |

0.187 |

| pre-TP vs post-TP |

-187.55 |

1382.05 |

224.20 |

-641.82 |

266.72 |

-0.84 |

37 |

0.408 |

| pre-VL vs post-VL |

-87.53 |

626.72 |

101.67 |

-293.52 |

118.47 |

-0.86 |

37 |

0.395 |

| pre-L/H vs post-L/H |

0.02 |

1.30 |

0.21 |

-0.42 |

0.45 |

0.08 |

36 |

0.936 |

| pre-LF vs post-LF |

-75.37 |

535.27 |

103.01 |

-287.12 |

136.37 |

-0.73 |

26 |

0.471 |

| pre-LFN vs post-LFN |

-17.24 |

99.25 |

19.85 |

-58.21 |

23.73 |

-0.87 |

24 |

0.394 |

| pre-HF vs post-HF |

-33.60 |

339.56 |

67.91 |

-173.76 |

106.56 |

-0.50 |

24 |

0.625 |

| pre-HFN vs post-HFN |

1.63 |

19.67 |

4.01 |

-6.68 |

9.93 |

0.41 |

23 |

0.689 |

Table 4.

Linear Regression analysis of the correlation between TBSA and different HRV variables.

Table 4.

Linear Regression analysis of the correlation between TBSA and different HRV variables.

| Dependent Variable |

SS |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

p value |

| pre-SD |

1227.296 |

1 |

1227.296 |

4.459 |

*0.042 |

| post-SD |

6.453 |

1 |

6.453 |

0.029 |

0.066 |

| pre-TP |

6658859.028 |

1 |

6658859.028 |

3.611 |

0.065 |

| post-TP |

4636.032 |

1 |

4636.032 |

0.004 |

0.949 |

| pre-VL |

1249148.75 |

1 |

1249148.75 |

3.982 |

0.054 |

| post-VL |

640.07 |

1 |

640.07 |

0.003 |

0.957 |

| pre-L/H |

1.29 |

1 |

1.29 |

1.118 |

0.297 |

| post-L/H |

0.16 |

1 |

0.16 |

0.195 |

0.661 |

| pre-LF |

2330.82 |

1 |

2330.82 |

0.014 |

0.905 |

| post-LF |

278133.52 |

1 |

278133.52 |

1.690 |

0.204 |

| pre-LFN |

91.89 |

1 |

91.89 |

0.311 |

0.582 |

| post-LFN |

813.35 |

1 |

813.35 |

0.090 |

0.766 |

| pre-HF |

130073.05 |

1 |

130073.05 |

0.959 |

0.337 |

| post-HF |

148400.67 |

1 |

148400.67 |

1.464 |

0.236 |

| pre-HFN |

392.02 |

1 |

392.02 |

1.957 |

0.174 |

| post-HFN |

20.47 |

1 |

20.47 |

0.095 |

0.760 |

References

- Choi, Y.H.; Kim, K.M.; Kim, H.O.; Jang, Y.C.; Kwak, I.S. Clinical and histological correlation in post-burn hypertrophic scar for pain and itching sensation. Ann Dermatol. 2013, 25, 428–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuignet, O.; Pirlot, A.; Ortiz, S.; Rose, T. The effects of electroacupuncture on analgesia and peripheral sensory thresholds in patients with burn scar pain. Burns 2015, 41, 1298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willows, B.M.; Ilyas, M.; Sharma, A. Laser in the management of burn scars. Burns 2017, 43, 1379–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.; Park, J.H.; Lee, D.Y.; Hwang, N.Y.; Ahn, S.; Lee, J.H. The important factors associated with treatment response in laser treatment of facial scars: a single-institution based retrospective study. Ann Dermatol. 2019, 31, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, M.H.; McGuire, M.; Mustoe, T.A.; Pusic, A.; Sachdev, M.; Waibel, J.; et al. Updated international clinical recommendations on scar management: part 2--algorithms for scar prevention and treatment. Dermatol Surg. 2014, 40, 825–31. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard, F.J., Jr.; Ryan, C.M.; Schneider, J.C. Physical and psychiatric recovery from burns. Surg Clin North Am. 2014, 94, 863–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S. The successful treatment of pain associated with scar tissue using acupuncture. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2014, 7, 262–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiozawa, P.; Silva, M.E.; Carvalho, T.C.; Cordeiro, Q.; Brunoni, A.R.; Fregni, F. Transcutaneous vagus and trigeminal nerve stimulation for neuropsychiatric disorders: a systematic review. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2014, 72, 542–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercante, B.; Deriu, F.; Rangon, C.M. Auricular neuromodulation: the emerging concept beyond the stimulation of vagus and trigeminal nerves. Medicines (Basel) 2018, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemtzow, R.C. Battlefield acupuncture. Med Acupunct. 2007, 19, 225–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, P.H.; Pock, A.; Ling, C.G.; Kwon, K.N.; Vaughan, M. Battlefield acupuncture: opening the door for acupuncture in Department of Defense/Veteran’s Administration health care. Nurs Outlook. 2016, 64, 491–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.H.; Chiang, Y.C.; Hoffman, S.L.; Liang, Z.; Klem, M.L.; Tam, W.W.; et al. Efficacy of auricular therapy for pain management: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014, 2014, 934670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleson, T. Progress in clinical applications of auricular acupuncture at the International Symposium on Auriculotherapy held in Singapore. SOJ Anesthesiol Pain Manag. 2018, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.H.; Hsu, C.H.; Jong, G.P.; Ho, S.; Tsay, S.L.; Lin, K.C. Auricular acupressure for managing postoperative pain and knee motion in patients with total knee replacement: a randomized sham control study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012, 2012, 528452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, K.M.L.; Oei, J.L.; Quah-Smith, I.; Kamar, A.A.; Lordudass, A.A.D.; Liem, K.D.; et al. Magnetic non-invasive auricular acupuncture during eye-exam for retinopathy of prematurity in preterm infants: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Front Pediatr. 2020, 8, 615008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.M.; Clelland, J.A.; Knowles, C.J.; Jackson, J.R.; Dimick, A.R. Effects of auricular acupuncture-like transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation on pain levels following wound care in patients with burns: a pilot study. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1990, 11, 322–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Chen, S.P.; Lyu, S.Y.; Hsu, C.H. Application of auriculotherapy for post-burn scar syndrome in young adults with major burns. Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian Studies. 2021, 14, 127–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sztajzel, J. Heart rate variability: a noninvasive electrocardiographic method to measure the autonomic nervous system. Swiss medical weekly. 2004, 134, 514–22. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana, D.S.; Guastella, A.J.; Outhred, T.; Hickie, I.B.; Kemp, A.H. Heart rate variability is associated with emotion recognition: Direct evidence for a relationship between the autonomic nervous system and social cognition. International journal of psychophysiology. 2012, 86, 168–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullett, N.; Zajkowska, Z.; Walsh, A.; Harper, R.; Mondelli, V. Heart rate variability (HRV) as a way to understand associations between the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and affective states: A critical review of the literature. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Moneghetti, K.J.; Christle, J.W.; Hadley, D.; Plews, D.; Froelicher, V. Heart Rate Variability: An Old Metric with New Meaning in the Era of using mHealth Technologies for Health and Exercise Training Guidance. Part One: Physiology and Methods. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2018, 7, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saul, J.P.; Valenza, G. Heart rate variability and the dawn of complex physiological signal analysis: methodological and clinical perspectives. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 2021, 379, 20200255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).