1. Introduction

As the global environmental crisis intensifies, the imperative for sustainable development becomes more acute. This is particularly evident in the energy sector, where a fundamental shift from traditional, fossil fuel-based sources to cleaner, renewable alternatives is not just desirable, but necessary. This transformation, encapsulated by the paradigm of “fossil energy clean, non-fossil energy scale, and energy system intelligence,” has become a focal point of research and policy worldwide [

1]. Embracing the International Renewable Energy Agency’s (IRENA) concept, we define energy transition as a comprehensive restructuring of energy systems, transitioning from traditional, fossil fuel-dominated sources to sustainable, low-carbon alternatives (IRENA, 2020). This transition, driven by environmental imperatives, the quest for energy security, and socio-economic development through renewable energy, is now at the forefront of global strategies [

2].

The urgency of this transition has been amplified by recent geopolitical developments, especially the Russia-Ukraine conflict, which has heightened the need to reduce reliance on external energy sources. This crisis has transformed the energy landscape into a global concern, necessitating immediate and long-term actions. The 2022 energy crisis, characterized by unprecedented shocks in natural gas, coal, and electricity markets, and significant disturbances in oil markets, is compelling governments worldwide to implement both immediate measures to alleviate economic impacts and hasten structural changes to diminish fossil fuel dependence, a major contributor to climate change since the Industrial Revolution. Nations are deploying various energy use programs to address these challenges, such as the US Inflation Reduction Act, the EU’s RePower EU and Fit for 55 packages, and Japan’s Green Transformation (GX) program. These initiatives aim to rapidly decrease fossil fuel use, as evidenced by ambitious clean energy targets set by countries like China and India, and global energy markets are adjusting to the disruption of Russia-Europe energy flows [

3]. The European Union (EU) has been particularly proactive, launching the RePowerEU Plan in 2022 to strengthen the objectives of its Fit for 55 initiative. In response to the global energy market disruptions, the RePowerEU Plan focuses on conserving energy, enhancing clean energy production, and diversifying energy sources. The ultimate goal is to accelerate the EU’s clean energy transition, thereby increasing Europe’s independence from unstable fossil fuels. Recognizing renewables as the most affordable and cleanest energy option, the EU proposes increasing its 2030 renewable energy target from 40% to 45%. The EU Solar Energy Strategy, part of this plan, is dedicated to expanding the deployment of photovoltaic energy (

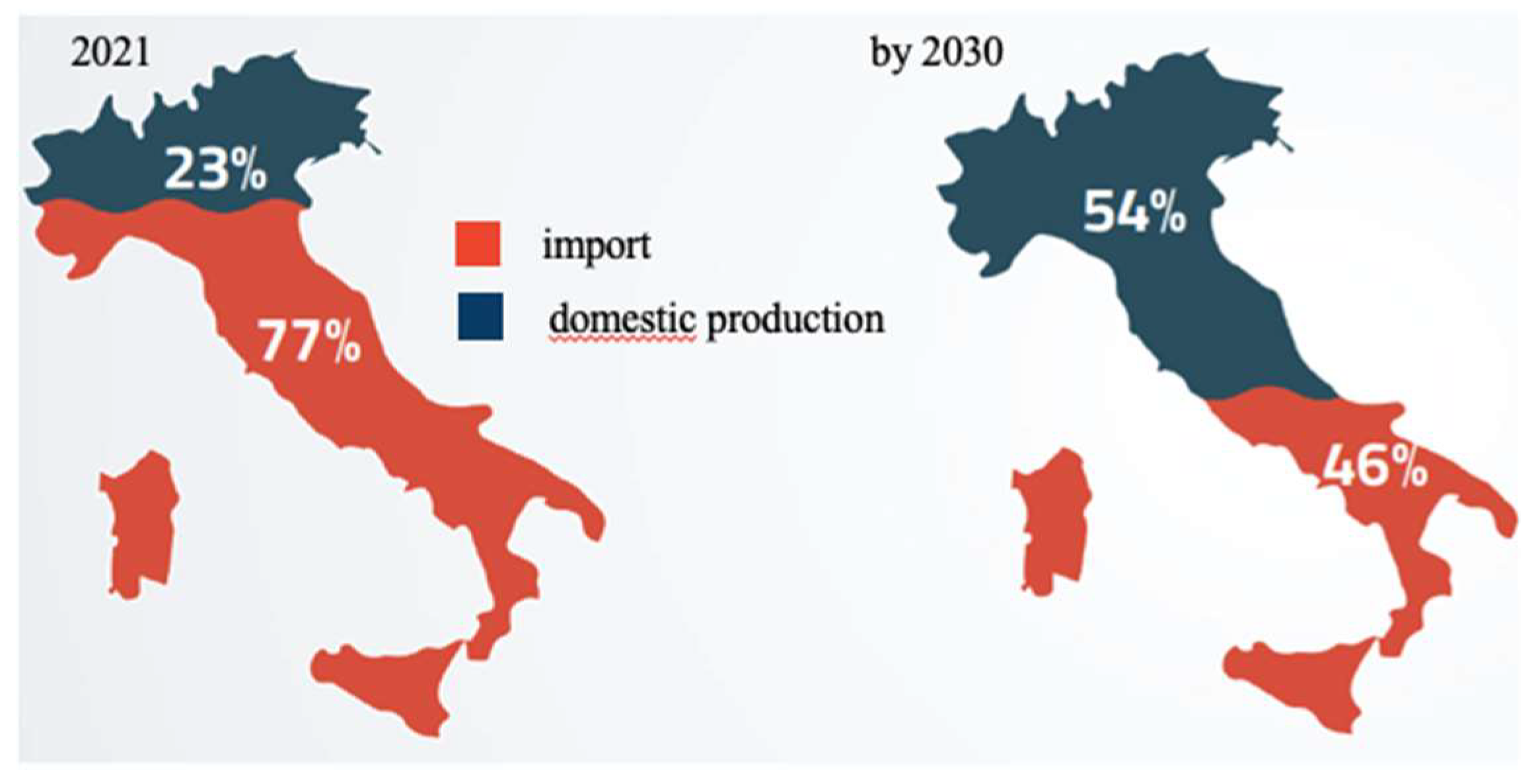

https://commission.europa.eu).In this context, Italy’s situation is particularly relevant. As a European country heavily impacted by the Ukraine-Russia conflict and with a high dependency on energy imports, Italy is at a critical juncture. Over 77% of Italy’s energy requirements, particularly in oil, gas, and coal, are met through imports [

4], with the gas sector almost entirely reliant on external sources. To align with the EU directives and increase energy independence, Italy has been revising its energy policies. The Italian National Energy Strategy emphasizes the role of energy communities in achieving national renewable energy targets and meeting the European target for 2023. Despite supportive legislation, implementing energy communities in Italy is challenged by administrative complexities, financial constraints, and a need for heightened public awareness [

5].

Figure 1.

Italian dependency on imports in 2021 and by 2030 [

8].

Figure 1.

Italian dependency on imports in 2021 and by 2030 [

8].

The 2030 Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted by world leaders at the UN summit in 2015, underscore the significance of cooperation in achieving sustainable development [

6]. This notion of shared commitment is particularly relevant in the energy sector. In 2019, the EU introduced the concept of energy communities, including renewable energy communities (RECs), in its legislation, promoting citizen participation and flexibility in electricity systems through demand response and storage. RECs represent a shift from traditional centralized energy systems to decentralized, community-driven initiatives, stimulating local economic development and fostering resilience and sustainability [

7].

Although private sector participation is clearly stated, it seems to be secondary compared to the main aim of a REC, spreading citizen participation and benefits, enhancing the double dimensions of generation of to an energy community -even in the case of ERCs. It is underpinning the active role of the industrial system, but enabling small and medium enterprises to enter and contribute actively to the development and management of REC.

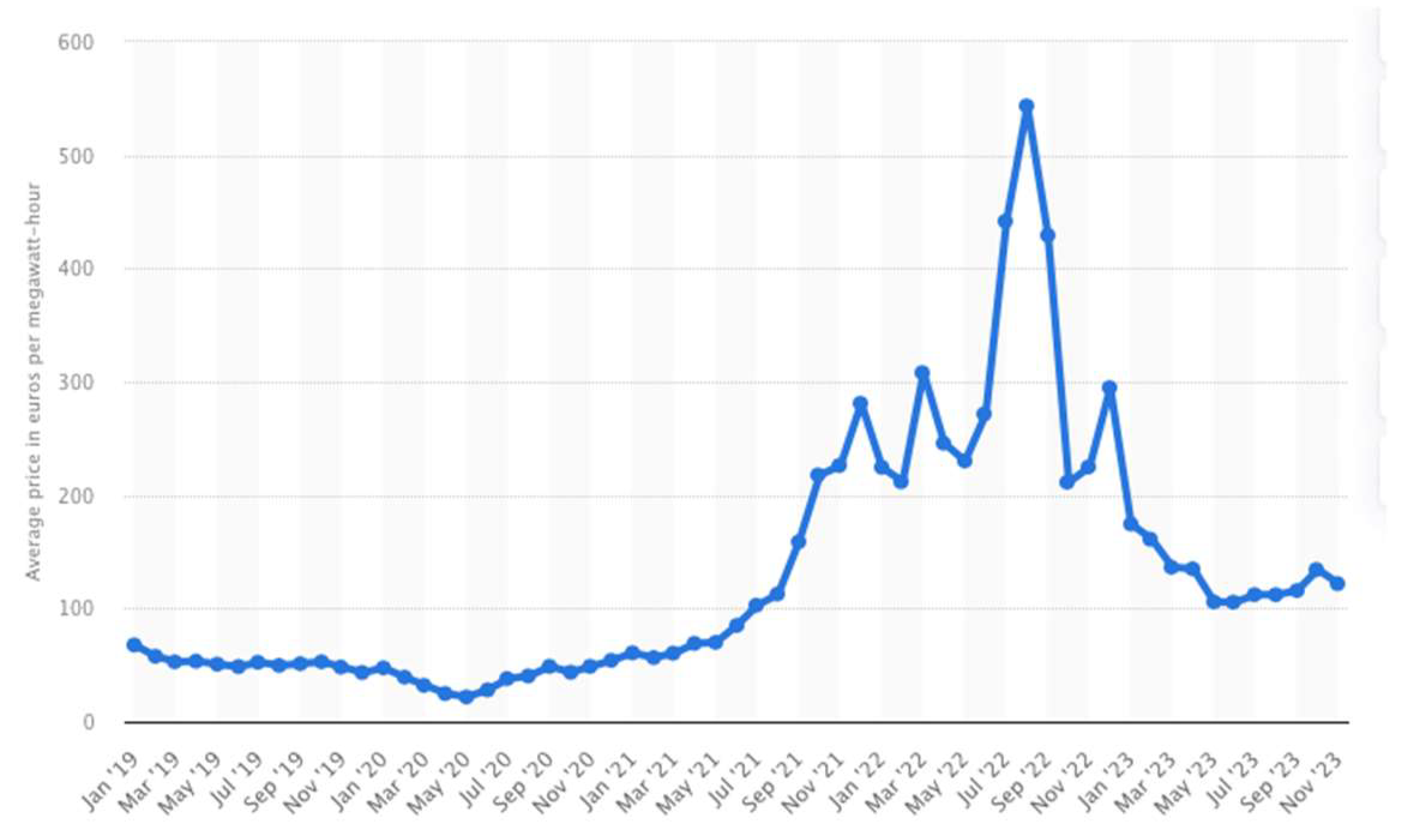

Since 2020, due to the global energy crisis, manufacturing industries (MI) experienced the greatest impact of energy costs – representing a consistent part of production costs and having a huge, direct influence on economic sustainability (

Figure 2). Amid extraordinary energy cost increases, MI have been—and still are— the industries most involved in the search for and adoption of energy solutions that aim to reduce the economic impact of these costs.

According to Statista.com [

8], the average wholesale electricity price in Italy amounted to 121.78 euros per megawatt hour in November 2023, a year-over-year decline of over 45 percent. In the past years, electricity prices in Italy soared, the result of several factors affecting much of Europe, including increased heating demand due to cold winters, a rise in natural gas and coal prices, a drop in wind power generation due to low wind speeds, a shortage of gas supply following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and extreme heat during the 2022 summer months. Since 2023, power prices have started to decrease.

Among manufacturing industries, large ones tend to drive their energy transition autonomously: they are typically more structured and educated than small and medium industries (SMIs). In Lombardy, a region at the forefront of industrial innovation and economic development in Italy, recent research [

9] documented the industrial sector’s commitment to energy-related matters, and confirms that industrial firms are particularly attuned to sustainability and energy matters. It also states a direct link between industrial size and the inclination to invest in sustainability. Thus, it is of utmost relevance to stimulate and support SMIs – the less open to investing in sustainability – to switch to new energy production frameworks, boosting renewable energy sources use, and facilitating their energy transition phase. The European Union (EU) along with national governments provides tools, support, and facilities for this aim, promoting the idea of energy communities that intend to provide clean energy to citizens and businesses [

10,

11]. In Lombardy, the potential for RECs is particularly notable. Lombardy government supports RECs development, which can include financial subsidies, technical assistance, or simplified procedures for renewable energy system installation [

12]. The regional government collaborates with municipalities, local businesses, and communities to foster RECs’ development. This involves sharing best practices and coordinating with local energy planning but integrating RECs in Lombardy’s environmental and urban planning policies [

13]. and undertaking educational initiatives to raise awareness about RECs and encourage public participation.

However, despite huge investments in spreading knowledge and encouraging participation, especially in creating renewable energy communities (RECs), such communities have not been developed on a wide scale yet.

This paper explores the framework for RECs in Lombardy, focusing on the private sector’s perspective. We consider small and medium enterprises as our focus and particularly, small and medium industries (SMI). Through a comprehensive survey conducted among Lombardy’s SMI, we have gathered insights into their readiness and willingness to participate in RECs. Our primary argument is that the active involvement of Local Public Bodies (LPBs) in leading RECs, combined with the possibility of extensive civil society participation, can increase SMI’s interest in joining RECs. This necessitates PABs to effectively communicate the concept of RECs and the associated benefits. This study aims to clarify the role of LPBs in facilitating REC participation and explores the cooperative model of RECs, engaging diverse partners in a shared energy project.

2. Literature review

2.1. REC

In recent years, there has been a growing awareness within academic circles about the critical role of business models that enable and accelerate the transition to renewable energy. These models are increasingly recognized for their positive impacts on social communities and the environment. Central to this discourse is the concept of distributed energy systems (DESs), the spread of renewable energy sources (RESs), and citizen involvement as key stakeholders in energy co-creation processes. Since the 2019 Clean Energy for All European Package (CEP) – and particularly the recast of the Renewable Energy Directive (REDII) [

14] a central and active role for citizens and communities in the energy transition from centralized, fossil-fuel-based systems to decentralized systems based on renewable energy sources (RES), is formally recognized. The package formalizes the rights of European citizens to become individual and/or collective prosumers [

15,

16,

17,

18]. The prosumer model for energy communities, while matching more than one Sustainable Development Goal (n. 11 – sustainable cities and communities; n.12 – responsible consumption and production; n 13 – climate action; n. 17 – partnership for the goals), underscores the importance of cooperation among natural persons (community members), the private sector (notably small and medium enterprises, SMEs), and public entities (such as local authorities and municipalities). The collective goal of these communities extends beyond financial profits, aiming to generate significant social and environmental benefits.

EU directives, established in the “Clean Energy for All Europeans” legislative package (CEP - Clean Energy Package), aim to implement adequate legal frameworks to facilitate the energy transition and give citizens a prominent role in the energy sector. Two directives within the CEP are of particular significance:

- the RED II defines a Renewable Energy Community (REC) as a “legal entity that, by the applicable national law, is based on open and voluntary participation, is autonomous, and is effectively controlled by shareholders or members that are located in the proximity of the renewable energy projects that are owned and developed by that legal entity; the shareholders or members of which are natural persons, SMEs or local authorities, including municipalities; the primary purpose of which is to provide environmental, economic or social community benefits for its shareholders or members or for the local areas where it operates, rather than financial profits [

19].

- the Directive on the Internal Market for Electricity (EU Directive 2019/944) [

20] defines a Citizen Energy Community (CEC) as a legal entity too, based on voluntary and open participation and is effectively controlled by members or shareholders that are natural persons, local authorities, including municipalities, or small enterprises; it has for its primary purpose to provide environmental, economic or social community benefits to its members or shareholders or to the local areas where it operates rather than to generate financial profits; and it may engage in generation, including from renewable sources, distribution, supply, consumption, aggregation, energy storage, energy efficiency services or charging services for electric vehicles or provide other energy services to its members or shareholders.

While these Directives differ, they both define an energy community as a “legal entity” based on “open and voluntary participation,” whose primary purpose is not to generate financial profits but to achieve environmental, economic, and social benefits. RECs have well-defined space limits for participants as they need to be close to the associated project of the Community. Also, to ensure the non-profit nature of energy communities, participation by energy sector companies (suppliers and ESCOs) as community members is not allowed; they are allowed to provide supply and infrastructure services.

RECs), as conceptualized in the Recast Renewable Energy Directive, Directive (EU) 2018/2001, represent a transformative approach to energy production and consumption. The governance of these entities is underscored by the principles of ease of entry and exit for households, as mandated by the Electricity Directive, emphasizing their accessible and democratic nature (Directive (EU) 2019/944).

The REC model is gaining traction as a means to enhance social acceptance of renewable energy sources, encourage decentralized energy production, and accelerate the energy transition [

21]. The EC acknowledges the substantial social role of energy communities, not only in delivering tangible benefits to partners, such as reducing electricity costs, increasing efficiency, and creating employment opportunities, but also in fostering wider societal impacts. These include enhancing public acceptance of renewable energy projects and attracting private investment in the clean energy transition. The EU’s emphasis on community engagement and energy democracy promotes local ownership and active participation in the sustainable energy system [

22]. This approach envisions energy communities as platforms where local residents actively engage in the development, operation, and benefit-sharing of renewable energy projects, fostering a sense of ownership and responsibility [

21].

The structure of these communities is based on the principle of voluntary participation, as outlined in the renewable energy directive. This flexibility allows partners to join or leave the community with ease, as stated in the electricity directive. Engaging the community in renewable energy initiatives encompasses several key aspects, including education, awareness campaigns, and transparent communication. These elements are critical in building community support and involvement [

23,

24].

As a result, Renewable Energy Community (REC) represents an innovative organizational model that unites citizens, associations, organizations, and businesses at a local level. Their objective is to construct and manage facilities for producing and sharing renewable energy through effective cooperation. This approach not only yields economic benefits but also engenders social and environmental advantages for all participants. RECs are increasingly recognized as catalysts for the development of local, ’zero-mile’ energy production.

Furthermore, energy communities serve as a collective instrument to facilitate the country’s clean energy transition. They play a crucial role in improving public acceptance of renewable energy projects and attracting much-needed private investments in the clean energy sector. The EU’s perspective on energy communities is inclusive and flexible, allowing them to adopt various legal forms, such as associations, cooperatives, partnerships, non-profit organizations, or small/medium-sized enterprises. This diversity enables citizens and market players to collaborate and invest jointly in energy assets, contributing to a more decarbonized and flexible energy system. As unified entities, energy communities can access suitable energy markets on a level playing field with other market actors, thereby enhancing the efficiency and sustainability of the energy transition. Ownership and control in RECs are uniquely structured to ensure effective participation by citizens, local authorities, and smaller businesses, especially those whose primary economic activity is not in the energy sector. This structure facilitates a grassroots approach to energy management, distinguishing RECs from traditional energy models. The primary purpose of RECs, as delineated, is to generate social and environmental benefits, shifting focus from profit maximization to community welfare and sustainability [

25] and aligning energy production priorities more closely with community needs and sustainable practices.

The economic benefits of RECs are significant, contributing to local economic development acting as catalysts for economic development by creating job opportunities, retaining financial gains within communities, and encouraging entrepreneurship [

26]. Socially, these communities foster local cohesion and environmental awareness, enhancing the quality of life of their members [

27]. In an environmental perspective, due to their decentralized nature, RECs are instrumental in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, contributing to global sustainability efforts to fight climate change [

28,

29] by focusing on local, renewable energy generation.

2.2. SMEs participation to REC

SME represents the very heart of every economic tissue, representing over 99% of businesses in the EU according to the Annual Report on European SMEs 2022/2023 [

30]: micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises contribute significantly to the EU’s economic landscape. In their journey for developing more sustainable, SME face several constraints –the most frequently cited according to Álvarez Jaramillo et al. [

31] were lack of resources, the high initial capital cost of implementing sustainability measures, and lack of expertise.

More recently, the global energy crisis boosted SMEs pressure toward reducing energy costs. This push arises from various factors, including economic forces, rising energy expenses, and shifting social attitudes towards the environment and broader corporate social responsibility initiatives, which encompass low carbon efforts. In the energy domain, although several legal requirements are especially devoted to larger companies to boost the low carbon transition, the EU recognize SME playing a relevant role for their impact. According with Conway, SME engagement in the low carbon could be due to the following features [

32]:

Innovative Potential: SMEs often have flexible organizations, strong local/regional focus, less bureaucracy, and a founder’s vision, enabling them to proactively create new products and processes quickly and innovate in the low carbon sector.

Responsiveness and Adaptability: They tend to be more adaptable and responsive to environmental changes and can implement low-carbon/environmental initiatives faster than larger companies.

Economic and Competitive Benefits: Engaging in low carbon initiatives can lead to cost savings through more efficient use of resources. This efficiency can also offer competitive advantages, such as labelling goods as ’eco-products’.

Reactive and Incremental Approach: Most SMEs adopt a reactive approach to environmental management that can quickly reflect in improved financial performance, especially at the early stages of low carbon activity adoption.

SMEs, along with individuals, households, and institutions, are identified as entities that can actively participate in the energy system as prosumers (Clean Energy for all Europeans Package) and are recognized as having ‘a particularly high potential for energy communities due to their energy demand and flexibility volume’ [

33]. The benefits for a SME entering a REC [

34,

35] could be economical (cost reduction and energy efficiency as SMEs in RECs can benefit from reduced energy costs due to shared renewable energy resources [

36]; also, SMEs may benefit from government subsidies, tax incentives, and grants for participating in RECs [

38,

39]), environmental (for participation in a REC allows SMEs to significantly lower their carbon footprint, aligning with global sustainability goals [

37]) and social (as for reputation enhancement: cooperate locally in a REC could improve SME’ brand image but fostering a sense of community and providing networking opportunities, beneficial for business growth and collaboration), contributing to generate a competitive edge in the market [

35,

40,

41].

To partner in a REC could also underline substantial limitations for a SME, typically related to its main features (resources constraints, lack of knowledge, and time to devote of the human resources [

39]), making engagement in similar low carbon initiatives, challenging [

42]. Resources constrains could also specifically refer to human resources, with inadequate technical skills to devote to the REC project [

43]. Limits could also be due to exogenous causes – such as lack of regulation, or policy uncertainty [

44], that could slow down SMEs willingness to partner in a REC.

2.3. The role of trust for SMEs

Research on trust results fragmented across multiple disciplines; in management since the late 90s, the concept has been investigated in an interfirm network perspective. Among the main contributors, Das [

45] has clearly stated the potential for partner’s confidence in building firm relationships, while in the same year Gulati [

46] underlined the negative impact of a lack of confidence between partner [

47]. Trust – along with partner reputation, plays a huge role in building a solid relationship; it needs to be carefully managed and developed over time to preserve the ongoing relationship [

48,

49].

In 2011, Sarker et al. [

50] extended the pivotal role of trust to distributed (‘virtual’) teams, not having shared history or common social context, are initially unknown each other and have very limited “face-to-face interaction”). According to this work, in situation where partners have divergent goals, values, and ideologies, trust stands as a means for the collaboration to be successful. Later on, Petrovich and Kubli [

33] underline social identification with the community as directly influencing the willingness to actively support and participate community energy projects. Trust benefits repeated interactions, where strong ethical business practices and consistent, positive experiences reinforce the belief in the reliability and integrity of the other party, building its reputation, as a result of trust-worthy behaviours [

51,

52,

53].

Trust and reputation play a notable role for SME facing lack of information, for instance mediating SME perception of the potential benefits of networks [

54], leading to greater information sharing and innovation, facilitating cooperation [

55].

The relevance of trust could be extended to Government and public bodies, suche as in a 2022 Deloitte work [

56], highlighting the increasing efforts of governments to engage with communities and become a trusted source of information: according to their research, the challenge for government leaders should be to improve engagement with communities while building trust (and, at the end, a solid reputation). trust is the foundational factor in government-community relationships. If people don’t trust an agency, they won’t be receptive to its messages or share their views honestly. This insight is particularly relevant for local governments when communicating with SMEs and other local stakeholders. Public entities such as the state, regions, provinces, and municipalities are organized in a hierarchy from a national to a territorial level, resembling a sort of pyramid structure. Following the same formal structure, SMEs often perceive a closer connection with local structures such as Municipalities (local public bodies, LPBs) and are more prone to develop trust-based relationship locally. This is due to more frequent interactions and often a personal acquaintance with various offices and officials responsible for activities at the local level. LPBs institution are in charge of SME development as one of the main factors enabling entrepreneurship (such factors are individual capacity, family life, social networking, business environment, government support policy and government support process [

39].

3. Materials and Methods

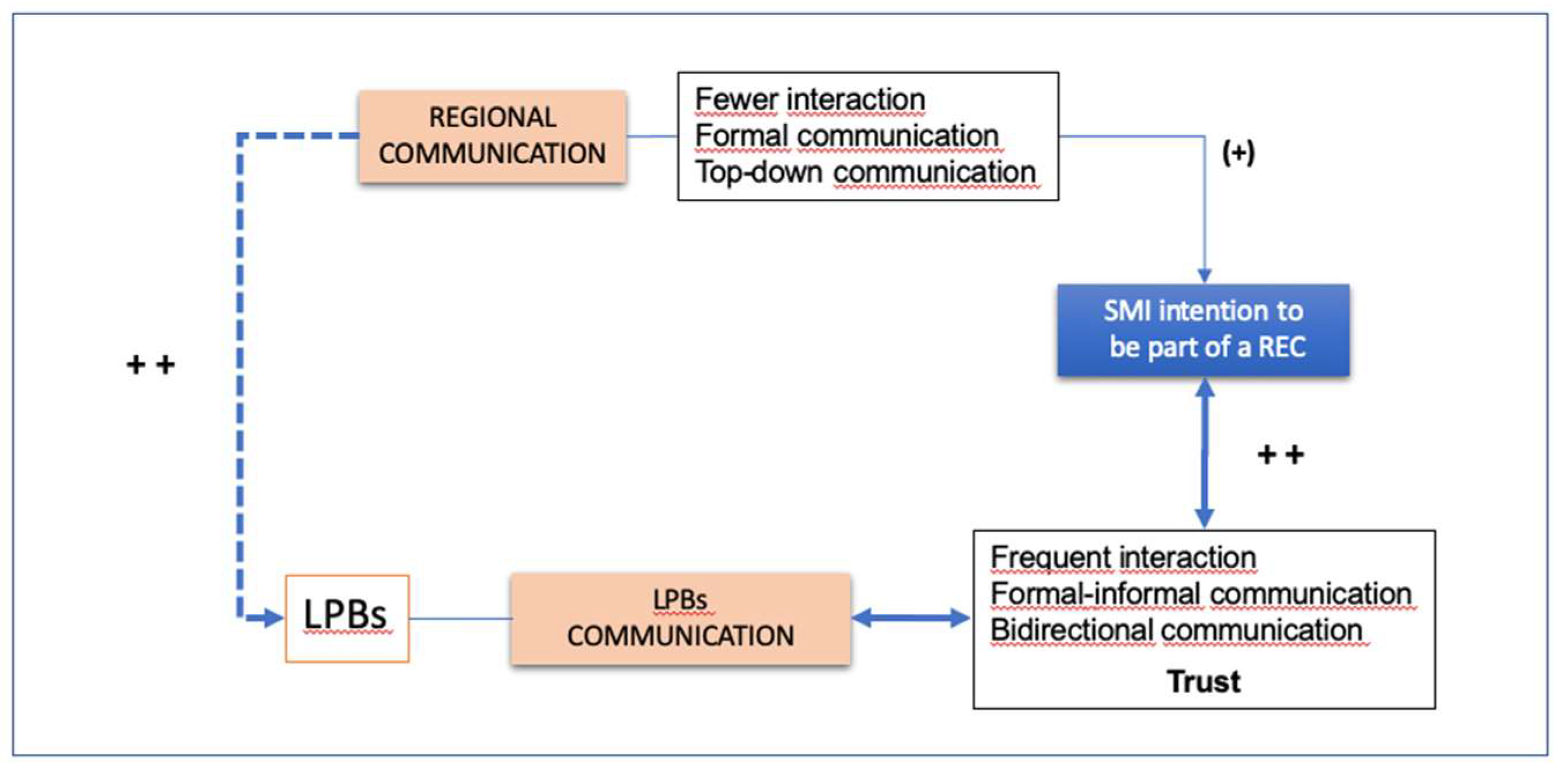

We suppose that considering the frequency of activation of the relationship, and the level of personal knowledge among them, a SME has a better direct knowledge and develops trust in LPBs than to regional (or even national level) institutions as we assume trust is built over repeated interactions, where consistent, positive experiences reinforce the belief in the reliability and integrity of the other party. For SMEs, frequent interactions with LPBs can foster a deeper understanding and trust. This proximity allows for more personalized, direct communication, and often a better alignment of interests and needs. Sometimes, familiarity with the individuals in charge at the municipal level can remove barriers to communication, making information exchange about initiatives like REC more efficient. Managers of SMEs often have direct knowledge of or even personal contacts within the LPBs, which can facilitate smoother and more open communication channels.

Even if there is not a one-size-fits-all scenario, we could thus hypothesize that LPBs are awarded with trust more than regional institution: local entities are closer to the day-to-day operations of SMEs, often sharing the same community and being more attuned to local challenges and needs. In contrast, regional public bodies might seem more distant, both in terms of physical location and in their understanding of local-specific issues. Thus, SMEs often have a more open and proactive attitude towards communication from local municipalities compared to regional institutions. This could be due to several factors, including geographical proximity, a sense of community, and more frequent interactions. Local authorities are perceived as more directly invested in the SME’s immediate environment, making their communication seem more relevant and urgent. Thus, we suppose frequent and positive engagements with local municipalities build a strong reputation, fostering trust. These established relationships make SMEs more receptive to communication from these entities. SMEs often have a strong sense of responsibility towards their local community and environment, with a positive effect on their performance [

57]. This sustainable attitude can make them more sensitive to initiatives like REC that have a direct impact on their locality. Local municipalities are seen as allies in promoting sustainable practices, reinforcing the SME’s commitment to its local area. In contrast, regional entities might not have the same level of regular interaction, leading to a lesser degree of trust and familiarity, with a more limited ability to stimulate SMEs toward regional initiatives.

We hypothesize SMEs perceive higher trust levels with LPBs, who can make local initiatives more stimulating than regional ones. This could be particularly true when the initiative in object has never been experienced before – such as in the case of RECs (

Figure 3). To validate the hypothesis, we consider investigating the small and medium industries of the Lombardy region, as it is the most industrialized area of the whole Country and one of the first economic areas of the European Union. The region shows the highest concentration rate for manufacturers in the industrial and craft domains. Lombardy, with its high industrial density, presented a strategic opportunity to address our research questions (RQs).

Particularly, we examined the following research questions:

RQ1: Given the extensive legislation regarding RECs published during 2020-2022 at the EU (CEP), national (Decreto Milleproroghe), and regional levels (regional law 2/2022), and considering the efforts to support REC development through the allocation of public resources for knowledge dissemination and opportunity expansion, is the concept of REC well-understood by SMIs in Lombardy?

RQ2: In light of the common regional commitment to disseminate knowledge and generate interest in RECs, but varying levels of commitment by LPBs, can a correlation be identified between the level of knowledge about RECs and the extent of LPBs’ commitment?

To collect original data for this study, we partnered with Confapindustria Lombardia (CL), a Lombardy-based organization representing small and medium-sized industrial enterprises (SMIs). Our focus on SMIs was driven by multiple factors. Significantly, since the energy crisis in 2021, energy expenses have become a crucial catalyst in advancing the shift to sustainable energy sources and reducing consumption. SMIs, in contrast to larger corporations that often independently manage sustainable energy initiatives, could offer more relevant insights for our study, particularly regarding their interest in Renewable Energy Communities (RECs), as discussed in the Literature review section.

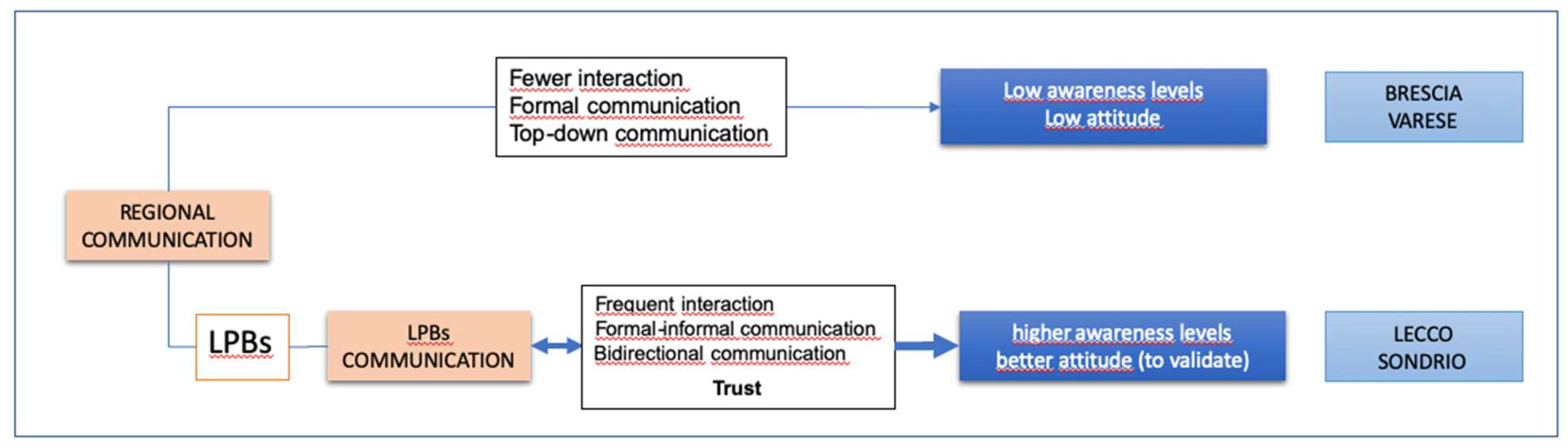

Earlier informal discussions with communication experts from local CL associations indicated varying levels of engagement by (LPBs) in promoting RECs among SMIs. Based on this information, we selected three geographical areas in the region: the provinces of Varese and Brescia, and the combined Lecco-Sondrio area. The provinces of Varese and Brescia had limited exposure to REC-related information from LPBs. In contrast, businesses in Lecco and Sondrio, although separate provinces, were treated as a singular area by CL and had considerable exposure to local institutional communications about RECs, demonstrating a high interest in disseminating knowledge and encouraging SMI participation in these initiatives.

4. Results

In January 2023, a comprehensive survey was distributed to SMI members of CL. Within a fortnight, it garnered 450 responses. Post exclusion of incomplete and anomalous entries, 212 responses were deemed suitable for evaluation. The demographic breakdown of the sample showed a predominance of SMIs in the metalworking sector, accounting for 48%, and 11% in the rubber and plastics industries, with other sectors each contributing less than 2%.

We consider three main questions. The first entails energy costs impact, on a scale of five levels as in

Table 1. Results indicated that for most respondents, energy costs had a marginal effect on revenue.

The second, considers the awareness levels of RECs on a five points scale. The third direct question asked for the attitude toward RECs. Data analysis required to re-organize with the following unique responses:

“Not interested,” or blank entry → 1

“I am currently searching for basic information” → 2

“I am currently Searching for in-depth information” → 3

“I will try to be part of a REC” → 4

“I am actively involved in a REC” → 5

We decided to give the lowest rate both to ones who declare themselves not interested but to the ones who don’t give any answer too as we consider the decision to “not waste time to give further information” as similar to a lack of interest.

To assess RQ1, we initially evaluated the level of awareness regarding RECs among participants. We employed a five-point semantic differential scale for data collection, ranging from 1 (indicating complete lack of knowledge) to 5 (indicating thorough knowledge). The findings in

Table 2 showed that half of the respondents scored 1, revealing a lack of awareness about RECs. Conversely, only 14% of respondents scored 4 or 5, demonstrating a strong or comprehensive understanding of RECs. Also, the mean knowledge level is approximately 2.02 and the median knowledge level is 1.0.

Considering the distribution plot, we observe that a significant number of respondents have rated their knowledge level as 1, indicating a low level of understanding of REC. The number of responses gradually decreases as the knowledge level increases, with very few respondents rating their knowledge at the highest levels (4 and 5). These findings suggest that the concept of REC is not well-understood by a majority of the SMIs in Lombardy, as indicated by the low mean and median knowledge levels and the high frequency of level 1 responses.

To have a more comprehensive understanding of the topic and to answer the best to RQ1, we first related the 5 point awareness levels to the different attitude the interviewed have toward RECs. The correlation rate is approximately 0.34 – indicating a moderate positive correlation. This suggests that as the self-assessed knowledge level of REC increases, there is a moderately positive trend in the attitudes towards REC. Data distribution is as in

Table 4.

Table 3.

Attitude towards ERC.

Table 3.

Attitude towards ERC.

Awareness level

Attitude towards ERC |

% |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| Not interested |

34% |

42% |

13% |

28% |

33% |

29% |

| Searching for basic information |

50% |

54% |

81% |

48% |

11% |

14% |

| Searching for in dept information |

8% |

2% |

6% |

16% |

33% |

0% |

| Try to build/enter in a ERC |

4% |

2% |

0% |

4% |

11% |

29% |

| Actively involved |

4% |

0% |

0% |

3% |

7% |

25% |

| Tot |

100% |

51% |

14% |

21% |

9% |

5% |

Results indicated a substantial lack of information about RECs, as 51% of SMIs were still searching for basic information about RECs – 54% of whom declared the level 1 awareness.

Secondly, we related the knowledge levels to the energy costs impact, to underline the urgency for the SMI the most affected by rising costs to RECs. At this end, we needed to convert the Energy costs impact as follows:

“0 to 5%”: 1,

“6% to 10%”: 2,

“11% to 20%”: 3,

“21% to 30%”: 4,

“more than 30%”: 5,

The resulting correlation rate is approximately 0.023, indicating a very weak positive correlation, suggesting that how significantly energy costs affect SMIs sales does not appear to be a major factor in shaping their attitudes towards REC.

Thus to give answer to RQ1, and considering the distribution of the awareness levels, we can consider that the mean and median knowledge levels were relatively low, indicating that a significant portion of respondents rated their understanding of REC as limited. Also, a high frequency of level 1 responses (lowest knowledge level) suggests that many SMIs have a basic or minimal understanding of REC.

The second research question entails to compare the same results on a local scale: the Mann-Whitney U test – a non-parametric test – is considered, as particularly useful for comparing two groups with ordinal data and not-normal distribution. Lecco-Sondrio area is compared, both for awareness of RECs and for SMI attitude toward RECs, to Varese and Brescia considered together, as their data distribution revealed a very similar pace. This should determine the statistical significance of any observed differences between these two defined groups.

The p-value for the knowledge levels and attitudes toward RECs, were performed by the Python library used for statistical analysis. If the p-value is low (below 0.05), it suggests that the difference in knowledge levels or attitudes between Lecco-Sondrio and the other provinces is statistically significant and not likely due to random chance. The following

table 4 and

table 5 summarize the survey data.

The results of the Mann-Whitney U test, used to compare the knowledge levels about RECs between Lecco-Sondrio and other provinces, indicate there is a statistically significant difference in the knowledge levels for the two groups: p-value is 0.0045, less than the typical threshold of 0.05. Also, the mean knowledge level in Lecco-Sondrio is approximately 2.40, which is higher than the mean knowledge level in other provinces, which is approximately 1.89 (

table 6).

These findings support the hypothesis that in areas like Lecco-Sondrio, where local bodies are actively involved in promoting RECs, there is a higher level of awareness or knowledge about RECs compared to areas where such promotion is primarily at the regional level.

On the contrary, the results of the Mann-Whitney U test comparing attitudes towards RECs between Lecco-Sondrio and other provinces indicate the difference is not statistically significant as the p-value reach 0.0836, which is greater than the typical threshold of 0.05 (

table 7). This is confirmed by the mean attitude level in Lecco-Sondrio – approximately 1.67, quite close to the mean value in Varese and Brescia (approximately 1.47): although the mean attitude level is slightly higher in Lecco-Sondrio compared to other provinces, this difference is not statistically significant according to the test. This suggests that while there might be a trend towards more positive attitudes towards RECs in Lecco-Sondrio, the evidence is not strong enough to conclusively demonstrate a significant impact of local promotional activities compared to regional efforts based on this data alone.

Thus to answer to RQ2 it is statistically demonstrate that Lecco-Sondrio area shows the highest mean knowledge level about RECs, consistent with the hypothesis that local commitment positively impacts awareness. On the other hand, Varese and Brescia, representing provinces with presumably less local commitment, show lower mean knowledge levels. Also, although LPBs action can positively affect RECs awareness levels among SMI, there is no clear evidence of its impact on attitude.

5. Discussion

Based on the data analysis, it is evident that the concept of REC lacks in-depth understanding by a majority of SMIs in Lombardy. This was well underlined by the overall low knowledge levels, and particularly by a significant portion of respondents rating their understanding as basic or minimal.

However, there is a moderate positive correlation between knowledge levels and attitudes towards REC (

Figure 4). This suggests that as the understanding of REC improves among SMIs, there tends to be a more positive and engaged attitude towards REC. This finding implies that enhancing the understanding and knowledge of REC among SMIs in Lombardy could potentially lead to more favorable attitudes and perhaps even greater engagement with REC initiatives.

To gain this result, it could be useful to rethink the communication process devoted to promoting and generating interest in RECs initiatives. A deeper investigation of the survey data has solicited attention toward local public bodies such as Municipalities. For their local nature, LPBs benefit SMI trust – a huge enabler for the decision-making process in lack of information condition.

Comparing provinces, there was a statistically significant difference in the knowledge levels about RECs between Lecco-Sondrio (with high local commitment) and other provinces. This indicates that local promotional activities, like those in Lecco-Sondrio, may have a positive impact on REC knowledge among SMIs. However, the difference in attitudes towards REC between Lecco-Sondrio and other provinces was not statistically significant: there was a trend of slightly more positive attitudes in Lecco-Sondrio, but this was not enough to conclusively demonstrate a significant impact of local promotional activities compared to regional efforts based solely on this data.

Although further investigation should be conducted to gain data validation on a wider scale, this analysis highlights the potential benefits of local engagement and commitment to raising awareness and understanding of RECs among SMIs. Increased knowledge about RECs in regions with higher local commitment, like Lecco-Sondrio, underscores the importance of localized efforts. Probably, translating this increased awareness into significantly more positive attitudes or proactive behaviors towards RECs may require additional strategies or efforts beyond awareness-raising.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to privacy restrictions. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express sincere gratitude to Confapindustria Lombardia for their support in this research, significantly contributing to data collection and, to the advancements presented in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cheng, W.J.; Mo, D.X.; Tian, Y.J.; Xu, W.Q.; Xie, K.C. Research on the composite index of the modern Chinese energy system. Sustainability 2019, 11 (1), citato da Jicheng Liu, Yu Yin, Suli Yan, Research on clean energy power generation-energy storage-energy using virtual enterprise risk assessment based on fuzzy analytic hierarchy process in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236, 117471. [CrossRef]

- Bazilian, M.; Bradshaw, M.; Goldthau, A. The Case for a Global Energy Transition. Nature 2019, 574, 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency. Available online: https://www.iea.org (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Italy for Climate. Available online: www.italyforclimate.org (accessed on 22 December 2023).

- Gaudiosi, G.; Benassi, L.; Mancini, L. Unpacking the territoriality of renewable energy communities in Italy: The role of administrative boundaries in shaping participation. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 75, 102047. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Available online: www.un.org (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Strielkowski, W.; Brůha, J.; Chigisheva, O. Socioeconomic aspects of renewable energy sources: Global trends, case studies and policy implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123459. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. Available online: www.statista.com (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Unioncamere Lombardia. Sostenibilità ambientale e sociale: la propensione delle imprese lombarde. Available online: www.unioncamerelombardia.it (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Mihailova, D.; et al. Exploring modes of sustainable value co-creation in renewable energy communities. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otamendi-Irizar, I.; et al. How can local energy communities promote sustainable development in European cities? Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 84, 102363. [Google Scholar]

- Regional Agency for Environmental Protection in Lombardy. Available online: www.arpalombardia.it (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Lombardy Regional Council. Available online: www.en.regione.lombardia.it (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- European Commission. Clean Energy for All Europeans Package. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-strategy/clean-energy-all-europeans-package_en (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Hall, S.; Brown, D.; Davis, M.; Ehrtmann, M.; Holstenkamp, L. Business models for prosumers in Europe. 2020.

- Horstink, L.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Ng, K. Pluralising the European energy landscape: Collective renewable energy prosumers and the EU’s clean energy vision. Energy Policy 2021, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laveyne, J.; Baetens, J.; et al. Addressing the Challenges of a Nuclear Phase-Out with Energy Synergies on Business Parks. In Proceedings of the First World Energies Forum, 2020; 58, 22.

- Biresselioglu, M.E.; Limoncuoglu, S.A.; Demir, M.H.; Reichl, J.; Burgstaller, K.; Sciullo, A.; Ferrero, E. Legal Provisions and Market Conditions for Energy Communities in Austria, Germany, Greece, Italy, Spain, and Turkey: A Comparative Assessment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renewable Energy Directive (RED II). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018L2001 (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Recast Electricity Directive (2019/944). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019L0944 (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Bauwens, T.; Aitken, M.; Devine-Wright, P. Energy communities and the energy transition: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 119, 109568. [Google Scholar]

- Dechezleprêtre, A.; Nachtigall, D.; Venmans, F. The importance of policy transparency for the adoption of clean energy: Evidence from the diffusion of solar photovoltaic systems in Germany. Energy Policy 2021, 149, 112102. [Google Scholar]

- Devine-Wright, P.; et al. Social Cohesion and Community Resilience in Renewable Energy Communities. Environ. Sociol. 2020.

- Walker, G.; Devine-Wright, P.; Hunter, S.; High, H.; Evans, B. Trust and community: Exploring the meanings, contexts and dynamics of community renewable energy. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 2655–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggett, C.; Aitken, M. Grassroots energy innovations: The role of community ownership and investment. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Strielkowski, W.; et al. Economic Catalysts and Benefits of Renewable Energy Communities. J. Renew. Energy Econ. 2021.

- Warbroek, B.; Hoppe, T. Sustainable energy transition at the community level: An interdisciplinary framework. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017.

- Sovacool, B.K.; Axsen, J. Functional, symbolic and societal frames for automobility: Implications for sustainability transitions. Transp. Res. Part A: Policy Pract. 2018.

- Seyfang, G.; Haxeltine, A. Growing grassroots innovations: Exploring the role of community-based initiatives in governing sustainable energy transitions. Environ. Plan. C: Gov. Policy 2012.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, Joint Research Centre; Di Bella, L.; Katsinis, A.; Lagüera-González, J. Annual report on European SMEs 2022/2023 – SME performance review 2022/2023. Publications Office of the European Union, 2023. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2826/69827 (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- Álvarez Jaramillo, J.; Zartha Sossa, J.W.; Orozco Mendoza, G.L. Barriers to sustainability for small and medium enterprises in the framework of sustainable development—Literature review. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, E. Engaging small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the low carbon agenda. Energy, Sustain. Soc. 2015, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovich, B.; Kubli, M. Energy communities for companies: Executives’ preferences for local and renewable energy procurement. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 184, 113506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D.; Coelho, P.S.; Machás, A. The role of communication and trust in explaining customer loyalty: An extension to the ECSI model. Eur. J. Mark. 2004, 38, 1272–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bögel, P.M. Company reputation and its influence on consumer trust in response to ongoing CSR communication. J. Mark. Commun. 2019, 25, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; Cameron, L. Renewable energy projects and the concept of shared benefits. J. Bus. Ethics 2015.

- Jones, A.; Willis, R. The role of SMEs in achieving sustainability goals. J. Sustain. Dev. 2017.

- Khan, J. Government policies and renewable energy investments. Energy Policy J. 2016.

- Sudibyo, Y.A.; Suhardi; Soesanto, E.; Soetjitro, P. The role of local government in developing small and medium-sized enterprises. J. Gov. Regul. 2017, 6, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T. Green business practices and competitive advantage. Int. J. Bus. Innov. 2018.

- Lee, K. Community renewable energy and socio-economic development. Renew. Energy J. 2019.

- Brown, D.; Lee, M. Barriers to renewable energy technology adoption. Energy Econ. J. 2014.

- Patel, V.; Perez, A. Challenges in renewable energy management. J. Energy Manage. 2015. 45. Nguyen, H.; Simkin, L. Impact of regulatory changes on renewable energy investments. Energy Policy J. 2016, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, H.; Simkin, L. Impact of regulatory changes on renewable energy investments. Energy Policy J. 2016.

- Das, T.K.; Teng, B.S. Between trust and control: Developing confidence in partner cooperation in alliances. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R. Alliances and networks. Strat. Manag. J. 1998, 19, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrakis, P.E.; Kostis, P.C. The Role of Knowledge and Trust in SMEs. J. Knowledge Econ. 2015, 6, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariño, A.; De la Torre, J.; Ring, P.S. Relational quality: Managing trust in corporate alliances. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2001, 44, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashant, K.; Harbir, S. Managing strategic alliances: what do we know now, and where do we go from here? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2009, 23, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, S.; Ahuja, M.; Sarker, S.; Kirkeby, S. The role of communication and trust in global virtual teams: A social network perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2011, 28, 273–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, L.T. Trust: the connecting link between organizational theory and philosophical ethics. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 379–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, T. Trust, reputation and corporate accountability to stakeholders. Bus. Ethics: A Eur. Rev. 2001, 10, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, L.K.; Weaver, G.R. Managing Ethics in Business Organizations: Social Scientific Perspectives. Stanford Business Books 2003, 392 pages.

- Brunetto, Y.; Farr-Wharton, R. The moderating role of trust in SME owner/managers’ decision-making about collaboration. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2007, 45, 362–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, A.; Iglič, H. Trust, governance and performance: The role of institutional and interpersonal trust in SME development. Int. Sociol. 2005, 20, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. Inclusive Government: Community Communication. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/public-sector/government-trends/2022/inclusive-government-community-communication.html (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Longo, M.; Mura, M.; Bonoli, A. Corporate social responsibility and corporate performance: the case of Italian SMEs. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2005, 5, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).