Submitted:

20 January 2024

Posted:

22 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

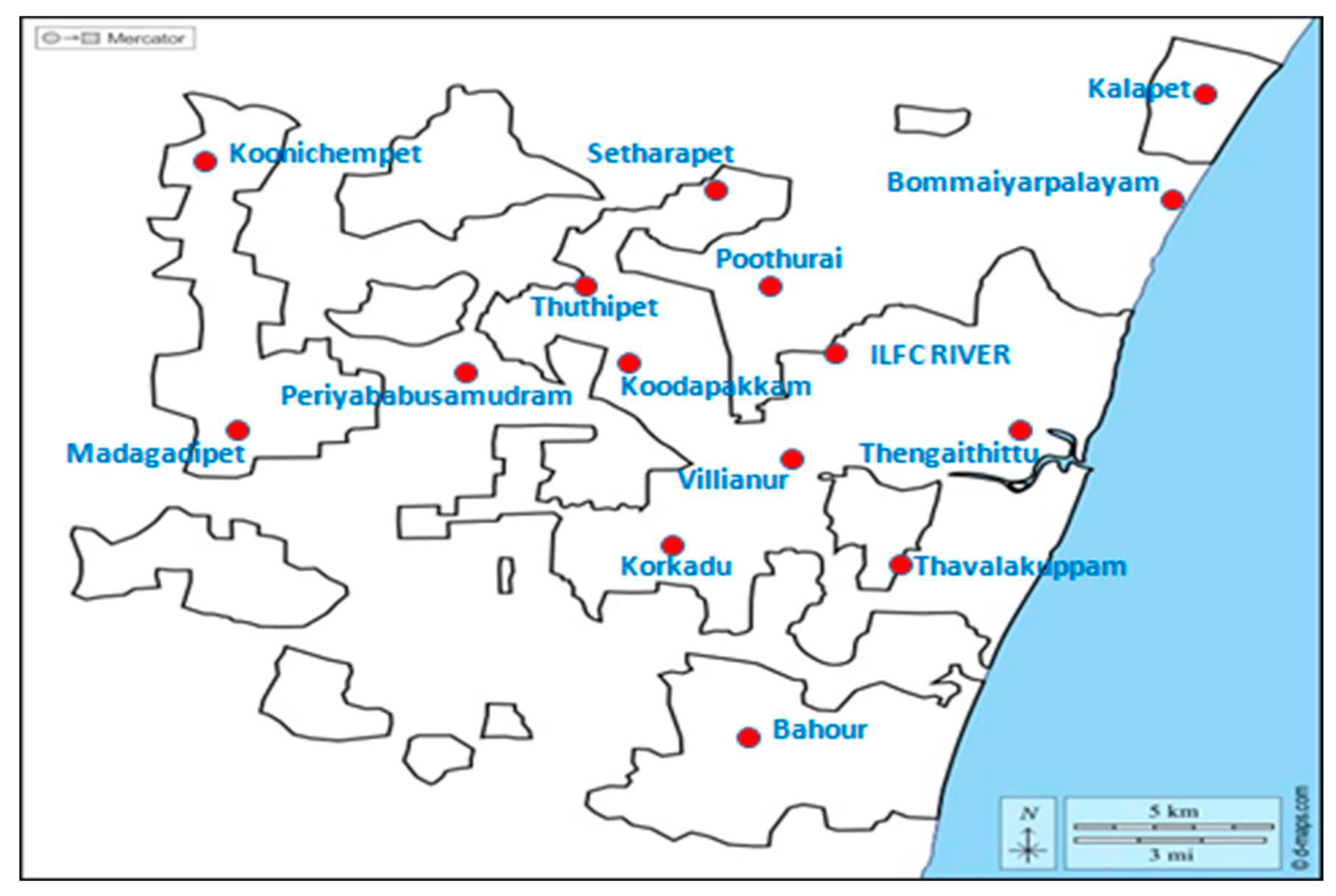

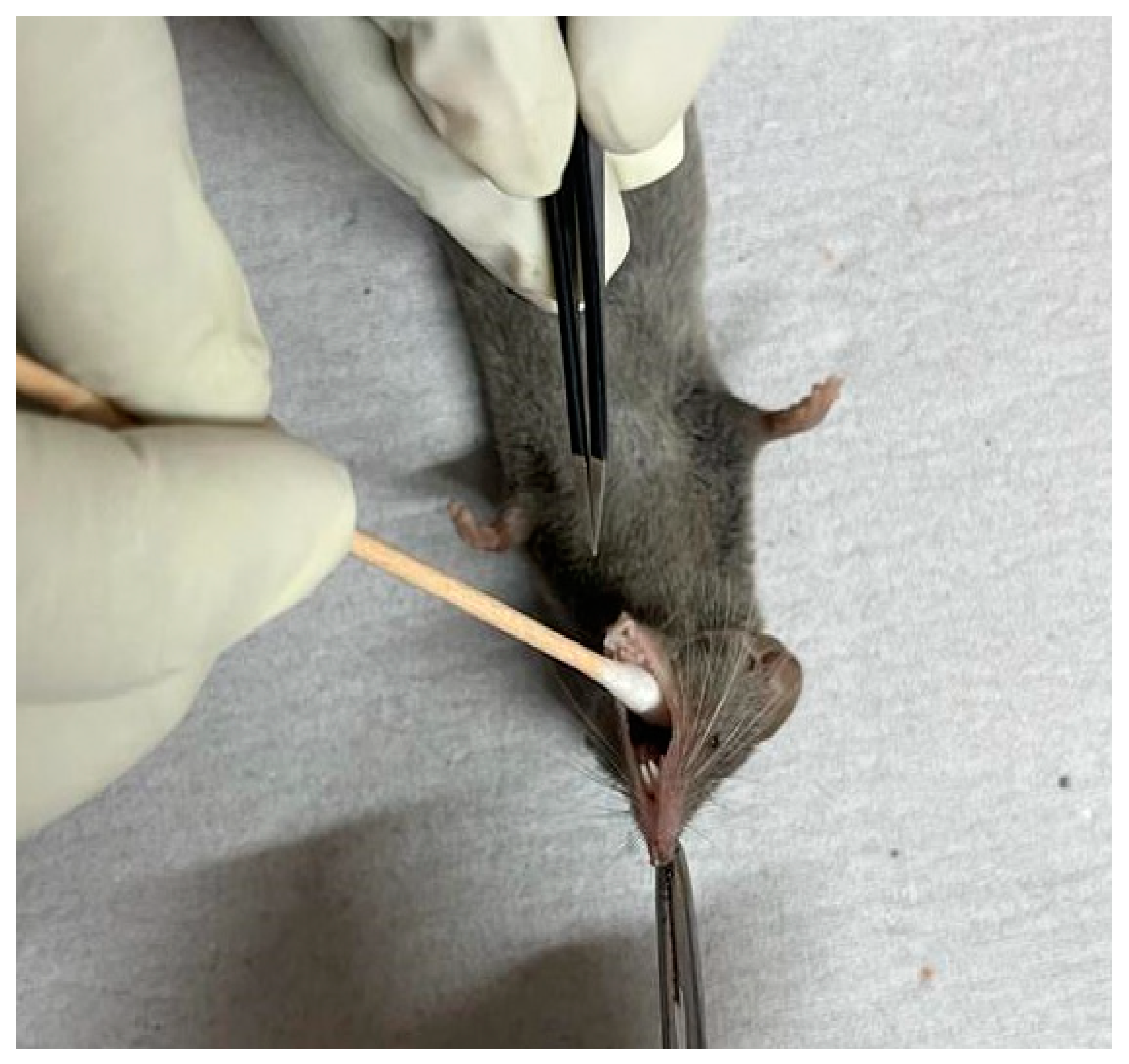

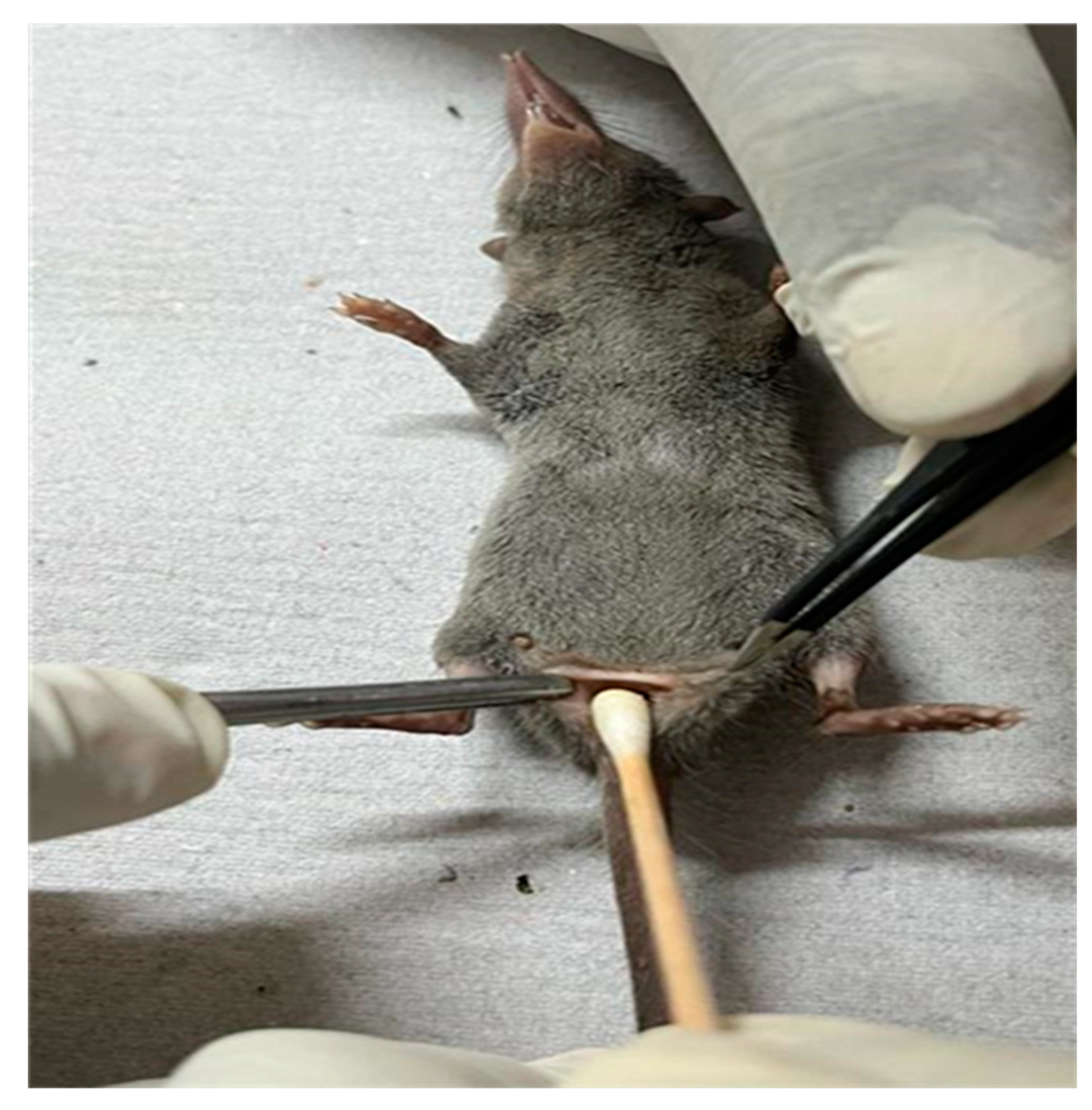

Collection and processing of samples

Isolation of the bacterial pathogens:

2.3. Preparation of template DNA

2.4. Identification of Staphylococcus spp. and genes conferring methicillin resistance by PCR

2.5. Detection of Escherichia coli and the presence of Extended Spectrum Beta Lactamase genes (ESBL) by PCR

2.6. PCR Detection of Salmonella sp and non-typhoidal Salmonella sp. and their AMR genes

2.7. Sequencing and analysis of the PCR products

3. Results

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgment

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Encyclopedia of Mammals, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press, 2006; ISBN 978-0-19-920608-7.

- Meerburg, B.G.; Singleton, G.R.; Kijlstra, A. Rodent-Borne Diseases and Their Risks for Public Health. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 35, 221–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gakuya, F.M.; Kyule, M.N.; Gathura, P.B.; Kariuki, S. Antimicrobial Resistance of Bacterial Organisms Isolated from Rats. East Afr. Med. J. 2001, 78, 646–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, S.J.; Paterson, G.K. Mechanisms of Methicillin Resistance in Staphylococcus Aureus. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2015, 84, 577–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.; Gabriel, S.I.; Borrego, S.B.; Tejedor-Junco, M.T.; Manageiro, V.; Ferreira, E.; Reis, L.; Caniça, M.; Capelo, J.L.; Igrejas, G.; et al. Antimicrobial Resistance and Genetic Lineages of Staphylococcus Aureus from Wild Rodents: First Report of mecC-Positive Methicillin-Resistant S. Aureus (MRSA) in Portugal. Animals 2021, 11, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.A.; Joshi, T.; Larsen, A.R.; Andersen, P.S.; Harms, K.; Mollerup, S.; Willerslev, E.; Fuursted, K.; Nielsen, L.P.; Hansen, A.J. Vancomycin Gene Selection in the Microbiome of Urban Rattus Norvegicus from Hospital Environment. Evol. Med. Public Health 2016, 2016, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Masoud, S.M.; Abd El-Baky, R.M.; Aly, S.A.; Ibrahem, R.A. Co-Existence of Certain ESBLs, MBLs and Plasmid Mediated Quinolone Resistance Genes among MDR E. Coli Isolated from Different Clinical Specimens in Egypt. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonola, V.S.; Katakweba, A.; Misinzo, G.; Matee, M.I. Molecular Epidemiology of Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Virulence Factors in Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia Coli Isolated from Rodents, Humans, Chicken, and Household Soils in Karatu, Northern Tanzania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, K.H.; Khor, W.C.; Quek, J.Y.; Low, Z.X.; Arivalan, S.; Humaidi, M.; Chua, C.; Seow, K.L.G.; Guo, S.; Tay, M.Y.F.; et al. Occurrence and Antimicrobial Resistance Traits of Escherichia Coli from Wild Birds and Rodents in Singapore. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, T.T.; Feasey, N.A.; Gordon, M.A.; Keddy, K.H.; Angulo, F.J.; Crump, J.A. Global Burden of Invasive Nontyphoidal Salmonella Disease, 2010(1). Emerg Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majowicz, S.E.; Musto, J.; Scallan, E.; Angulo, F.J.; Kirk, M.; O’Brien, S.J.; Jones, T.F.; Fazil, A.; Hoekstra, R.M. International Collaboration on Enteric Disease “Burden of Illness” Studies The Global Burden of Nontyphoidal Salmonella Gastroenteritis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 50, 882–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, P.F.; Zhao, S.; Tate, H. Antimicrobial Resistance in Nontyphoidal Salmonella. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, V.C. Taxonomic Studies on Indian Muridae and Hystricidae: Mammalia, Rodentia; Records of the Zoological Survey of India; Zoological Survey of India: Calcutta, India, 2000; ISBN 978-81-85874-31-9. [Google Scholar]

- Soumya, M.P.; Pillai, R.M.; Antony, P.X.; Mukhopadhyay, H.K.; Rao, V.N. Comparison of Faecal Culture and IS900 PCR Assay for the Detection of Mycobacterium Avium Subsp. Paratuberculosis in Bovine Faecal Samples. Vet. Res. Commun. 2009, 33, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Sparling, J.; Chow, B.L.; Elsayed, S.; Hussain, Z.; Church, D.L.; Gregson, D.B.; Louie, T.; Conly, J.M. New Quadriplex PCR Assay for Detection of Methicillin and Mupirocin Resistance and Simultaneous Discrimination of Staphylococcus Aureus from Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 4947–4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brakstad, O.G.; Aasbakk, K.; Maeland, J.A. Detection of Staphylococcus Aureus by Polymerase Chain Reaction Amplification of the Nuc Gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1992, 30, 1654–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, D.C.; de Lencastre, H. Multiplex PCR Strategy for Rapid Identification of Structural Types and Variants of the Mec Element in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 2155–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stegger, M.; Andersen, P.S.; Kearns, A.; Pichon, B.; Holmes, M.A.; Edwards, G.; Laurent, F.; Teale, C.; Skov, R.; Larsen, A.R. Rapid Detection, Differentiation and Typing of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Harbouring Either mecA or the New mecA Homologue mecA(LGA251). Clin. Microbiol. Infect 2012, 18, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Griffiths, M.W. PCR Differentiation of Escherichia Coli from Other Gram-Negative Bacteria Using Primers Derived from the Nucleotide Sequences Flanking the Gene Encoding the Universal Stress Protein. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1998, 27, 369–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colom, K.; Pérez, J.; Alonso, R.; Fernández-Aranguiz, A.; Lariño, E.; Cisterna, R. Simple and Reliable Multiplex PCR Assay for Detection of blaTEM, Bla(SHV) and blaOXA-1 Genes in Enterobacteriaceae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003, 223, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, J.K.; Jay, C.; Metchock, B.; Berkowitz, F.; Weigel, L.; Crellin, J.; Steward, C.; Hill, B.; Medeiros, A.A.; Tenover, F.C. Evolution of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactam Resistance (SHV-8) in a Strain of Escherichia Coli during Multiple Episodes of Bacteremia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997, 41, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, T.K.; Warjri, I.; Roychoudhury, P.; Lalzampuia, H.; Samanta, I.; Joardar, S.N.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Chandra, R. Extended-Spectrum-β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia Coli Isolate Possessing the Shiga Toxin Gene (Stx1) Belonging to the O64 Serogroup Associated with Human Disease in India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 2008–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aabo, S.; Rasmussen, O.F.; Rossen, L.; Sørensen, P.D.; Olsen, J.E. Salmonella Identification by the Polymerase Chain Reaction. Mol. Cell Probes 1993, 7, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, M.W.; Mahon, J.; Lax, A.J. Development of a Probe and PCR Primers Specific to the Virulence Plasmid of Salmonella Enteritidis. Mol. Cell Probes 1994, 8, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumet, C.; Ermel, G.; Rose, N.; Rose, V.; Drouin, P.; Salvat, G.; Colin, P. Evaluation of a Multiplex PCR Assay for Simultaneous Identification of Salmonella Sp., Salmonella Enteritidis and Salmonella Typhimurium from Environmental Swabs of Poultry Houses. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1999, 28, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olobatoke, R.Y.; Mulugeta, S.D. Incidence of Non-Typhoidal Salmonella in Poultry Products in the North West Province, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2015, 111, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Chiu, C.H.; Wu, W.Y.; Chu, C.H.; Liu, T.P.; Ou, J.T. Large Drug Resistance Virulence Plasmids of Clinical Isolates of Salmonella Enterica Serovar Choleraesuis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 2299–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehrenberg, C.; Friederichs, S.; de Jong, A.; Michael, G.B.; Schwarz, S. Identification of the Plasmid-Borne Quinolone Resistance Gene qnrS in Salmonella Enterica Serovar Infantis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 58, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittecoq, M.; Godreuil, S.; Prugnolle, F.; Durand, P.; Brazier, L.; Renaud, N.; Arnal, A.; Aberkane, S.; Jean-Pierre, H.; Gauthier-Clerc, M.; et al. Antimicrobial Resistance in Wildlife. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-J.; Huang, Y.-C. New Epidemiology of Staphylococcus Aureus Infection in Asia. Clin. Microbiol. Infect 2014, 20, 605–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porrero, M.C.; Mentaberre, G.; Sánchez, S.; Fernández-Llario, P.; Gómez-Barrero, S.; Navarro-Gonzalez, N.; Serrano, E.; Casas-Díaz, E.; Marco, I.; Fernández-Garayzabal, J.-F.; et al. Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) Carriage in Different Free-Living Wild Animal Species in Spain. Vet. J. 2013, 198, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van De Giessen, A.W.; Van Santen-Verheuvel, M.G.; Hengeveld, P.D.; Bosch, T.; Broens, E.M.; Reusken, C.B.E.M. Occurrence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus in Rats Living on Pig Farms. Prev. Vet. Med. 2009, 91, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Álvarez, L.; Holden, M.T.G.; Lindsay, H.; Webb, C.R.; Brown, D.F.J.; Curran, M.D.; Walpole, E.; Brooks, K.; Pickard, D.J.; Teale, C.; et al. Meticillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus with a Novel mecA Homologue in Human and Bovine Populations in the UK and Denmark: A Descriptive Study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011, 11, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, T.K.; Shome, B.R.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Goyal, N.K.; Lundkvist, Å.; Deka, R.P.; Shome, R.; Venugopal, N.; Grace, D.; Sharma, G.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococci from the Dairy Value Chain in Two Indian States. Pathogens 2023, 12, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, J.; Zhong, X.; Xiong, Y.; Qiu, M.; Huo, S.; Chen, X.; Mo, Y.; Cheng, M.; Chen, Q. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus among Urban Rodents, House Shrews, and Patients in Guangzhou, Southern China. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, M.C. Overview: Foodborne Pathogens in Wildlife Populations. In Food Safety Risks from Wildlife; Jay-Russell, M., Doyle, M.P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–30. ISBN 978-3-319-24440-2. [Google Scholar]

- Baquero, F.; Coque, T.M.; Martínez, J.-L.; Aracil-Gisbert, S.; Lanza, V.F. Gene Transmission in the One Health Microbiosphere and the Channels of Antimicrobial Resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkogwe, C.; Raletobana, J.; Stewart-Johnson, A.; Suepaul, S.; Adesiyun, A. Frequency of Detection of Escherichia Coli, Salmonella Spp., and Campylobacter Spp. in the Faeces of Wild Rats (Rattus Spp.) in Trinidad and Tobago. Vet. Med. Int. 2011, 2011, 686923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onanga, R.; Mbehang Nguema, P.P.; Ndong Atome, G.R.; Mabika Mabika, A.; Ngoubangoye, B.; Komba Tonda, W.L.; Obague Mbeang, J.C.; Lebibi, J. Prevalence of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases in E. Coli of Rats in the Region North East of Gabon. Vet. Med. Int. 2020, 2020, 5163493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himsworth, C.G.; Zabek, E.; Desruisseau, A.; Parmley, E.J.; Reid-Smith, R.; Jardine, C.M.; Tang, P.; Patrick, D.M. Prevalence and Characterization of E.Coli and Salmonella Spp in the Feces of Wild Urban Norway and Black Rats (Rattus Norvegius and Rattus Ratttus ) from an Inner City Neighbourhood of Vancouver. J. Wildl. Dis. 2015, 51, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guenther, S.; Bethe, A.; Fruth, A.; Semmler, T.; Ulrich, R.G.; Wieler, L.H.; Ewers, C. Frequent Combination of Antimicrobial Multiresistance and Extraintestinal Pathogenicity in Escherichia Coli Isolates from Urban Rats (Rattus Norvegicus) in Berlin, Germany. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e50331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Literák, I.; Dolejska, M.; Cizek, A.; Djigo, C.A.T. Reservoirs of Antibiotic-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae among Animals Sympatric to Humans in Senegal: Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases in Bacteria in a Black Rat (Rattus Rattus). Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 3, 751–754. [Google Scholar]

- Burriel, A.R.; Kritas, S.K.; Kontos, V. Some Microbiological Aspects of Rats Captured Alive at the Port City of Piraeus, Greece. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2008, 18, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliver, M.A.; Bennett, M.; Begon, M.; Hazel, S.M.; Hart, C.A. Antibiotic Resistance Found in Wild Rodents. Nature 1999, 401, 233–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, P.-L.; Lo, W.-U.; Lai, E.L.; Law, P.Y.; Leung, S.M.; Wang, Y.; Chow, K.-H. Clonal Diversity of CTX-M-Producing, Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia Coli from Rodents. J. Med. Microbiol. 2015, 64, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (EFSA and ECDC) The European Union One Health 2018 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J. 2019, 17, e05926. [CrossRef]

- El-Sharkawy, H.; Tahoun, A.; El-Gohary, A.E.-G.A.; El-Abasy, M.; El-Khayat, F.; Gillespie, T.; Kitade, Y.; Hafez, H.M.; Neubauer, H.; El-Adawy, H. Epidemiological, Molecular Characterization and Antibiotic Resistance of Salmonella Enterica Serovars Isolated from Chicken Farms in Egypt. Gut. Pathog. 2017, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taioe, M.O.; Thekisoe, O.M.M.; Syakalima, M.; Ramatla, T. Confirmation of Antimicrobial Resistance by Using Resistance Genes of Isolated Salmonella Spp. in Chicken Houses of North West, South Africa. Jwpr 2019, 9, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, E.K.; Ayyash, D.B.; Alturkistni, W.; Alyahiby, A.; Yaghmoor, S.; Iyer, A.; Yousef, J.; Kumosani, T.; Harakeh, S. Impact of Sporadic Reporting of Poultry Salmonella Serovars from Selected Developing Countries. J. Infect Dev. Ctries 2015, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feasey, N.A.; Dougan, G.; Kingsley, R.A.; Heyderman, R.S.; Gordon, M.A. Invasive Non-Typhoidal Salmonella Disease: An Emerging and Neglected Tropical Disease in Africa. Lancet 2012, 379, 2489–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelloni, F.; Tosi, G.; Massi, P.; Fiorentini, L.; Parigi, M.; Cerri, D.; Ebani, V.V. Some Pathogenic Characters of Paratyphoid Salmonella Enterica Strains Isolated from Poultry. Asian Pac J. Trop. Med. 2017, 10, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, S.; Antony, P.X.; Mukhopadhyay, H.K.; Pillai, R.M.; Thanislass, J.; Padmanaban, V.; Srinivas, M.V. Genetic Characterization of Fluoroquinolone-Resistant Escherichia Coli Associated with Bovine Mastitis in India. Vet. World 2016, 9, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramatla, T.; Tawana, M.; Lekota, K.E.; Thekisoe, O. Antimicrobial Resistance Genes of Escherichia Coli, a Bacterium of “One Health” Importance in South Africa: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AIMS Microbiol. 2023, 9, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Maksoud, M.; Abdel-Khalek, R.; El-Gendy, A.; Gamal, R.F.; Abdelhady, H.M.; House, B.L. Genetic Characterisation of Multidrug-Resistant Salmonella Enterica Serotypes Isolated from Poultry in Cairo, Egypt. Afr. J. Lab. Med. 2015, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Bacterial Pathogens | Targeted gene | Sequences | Annealing temperature | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus sp | 16S rRNA | AACTCTGTTATTAGCGAAGAACA CCACCTTCCTCCGGTTTGTCACC |

50°C for 1 min | 16 |

| S. aureus | nuc | GCGATTGATGGTGATACGGT AGCCAAGCCTTGACGAACTAAAGC |

55°C for 30 sec | 17 |

| Methicillin resistance | mec A | TCCAGATTACAACTTCACCAGG CCACTTCATATCTTGTAACG |

50°C for 1 min | 18 |

| mec C | GAAAAAAAGGCTTAGAACGCCC GAAGATCTTTTCCGTTTTCAGC |

19 | ||

| E. coli | uspA | CCGATACGCTGCCAATCAGT ACGCAGACCGTAAGGGCCAGAT |

60°C for 1.5 mins | 20 |

| ESBL-producing E. coli | TEM | ATGAGTATTCAACATTTCCG CTGACAGTTACCAATGCTTA |

56°C for 1 min | 21 |

| SHV | AGGATTGACTGCCTTTTTG ATTTGCTGATTTCGCTCG |

22 | ||

| CTX-M | CAATGTGCAGCACCAAGTAA CGCGATATCGTTGGTGGTG |

59°C for 30 sec | 23 | |

| Salmonella sp | invA | GCCAACCATTGCTAAATTGGCGCA GGTAGAAATTCCCAGCGGGTACTG |

55°C for 45 sec | 24 |

| Salmonella enteritidis | spvC | GCCGTACACGAGCTTATAGA ACCTACAGGGGCACAATAAC |

57°C for 45 sec | 25 |

| Salmonella typhimurium | fliC | CGGTGTTGCCCAGGTTGGTAAT ACTGGTAAAGATGGCT |

55°C for 45 sec | 26 |

| Tetracycline resistance | Tet | GCACTTGTCTCCTGTTTACTCCCC CCTTGTGGTTATGTTTTGGTTCCG |

53°C for 1min | 27 |

| Sulphonamides resistance | sul3 & sul4 | TCAACATAACCTCGGACAGT GATGAAGTCAGCTCCACCT |

60°C for 40 sec | 28 |

| Fluoroquinolone resistance | qnrA | TCAGCAAGAGGATTTCTCA GGCAGCACTATGACTCCCA |

53°C for 30 sec | 29 |

| The animal reservoir | Staphylococcus spp. and the AMR genetic element tested positive in the rodent/shrew screened | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | Staphylococcus non-aureus | Staphylococcus aureus | ||||

| mec A | mec C | mec A | mec C | mec A and mec C | ||

| Rattus rattus | 10 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Suncus murinus | 30 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 4 | |

| Total | 40 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 5 | |

| The animal reservoir | E.coli and the AMR genetic element tested positive in the rodent/shrew screened | |||||

| TEM | SHV | CTX-M | TEM and SHV | SHV and CTX-M | TEM, SHV, and CTX-M | |

| Rattus rattus | 6 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 1 |

| Suncus murinus | 15 | 37 | 9 | 11 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 21 | 45 | 11 | 13 | 7 | 2 |

| The animal reservoir | Salmonella spp. and the AMR genetic element tested positive in the rodent/shrew screened | |||||

| tet | sul 3 and sul 4 | qnrA | tet and qnrA | tet and sul 3 & sul 4 | sul 3 & sul 4 and qnrA | |

| Rattus rattus | 3 | 5 | 2 | - | 2 | - |

| Suncus murinus | 10 | 15 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Total | 13 | 20 | 11 | 2 | 6 | 1 |

| Pathogen | Staphylococcus sp | S. aureus | MRSA | MRSA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | (16S rRNA) | (nuc) | (mec A) | (mec C) | ||

| Genbank accession ID | OQ979122, OQ979123 | OQ992661, OQ992662 | OQ992663, OQ992664 | OQ992664 | ||

| Pathogen | E. coli | |||||

| Gene | (uspA) | TEM | SHV | CTX M | ||

| Genbank accession ID | OQ872769 | OR066219 | OR066218 | OR066217 | ||

| Pathogen | Salmonella spp | S. enteritidis | S. typhimurium | |||

| Gene | (invA) | (spvC) | (fliC) | tet | sul3 & sul4 | qnrA |

| Genbank accession ID | OR066220, OR066221 | OR066224, OR066225 | OR066222, OR066223 | OQ992668, OQ992669 | OQ992665, OQ992666 | OQ992667 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).