Submitted:

19 January 2024

Posted:

22 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

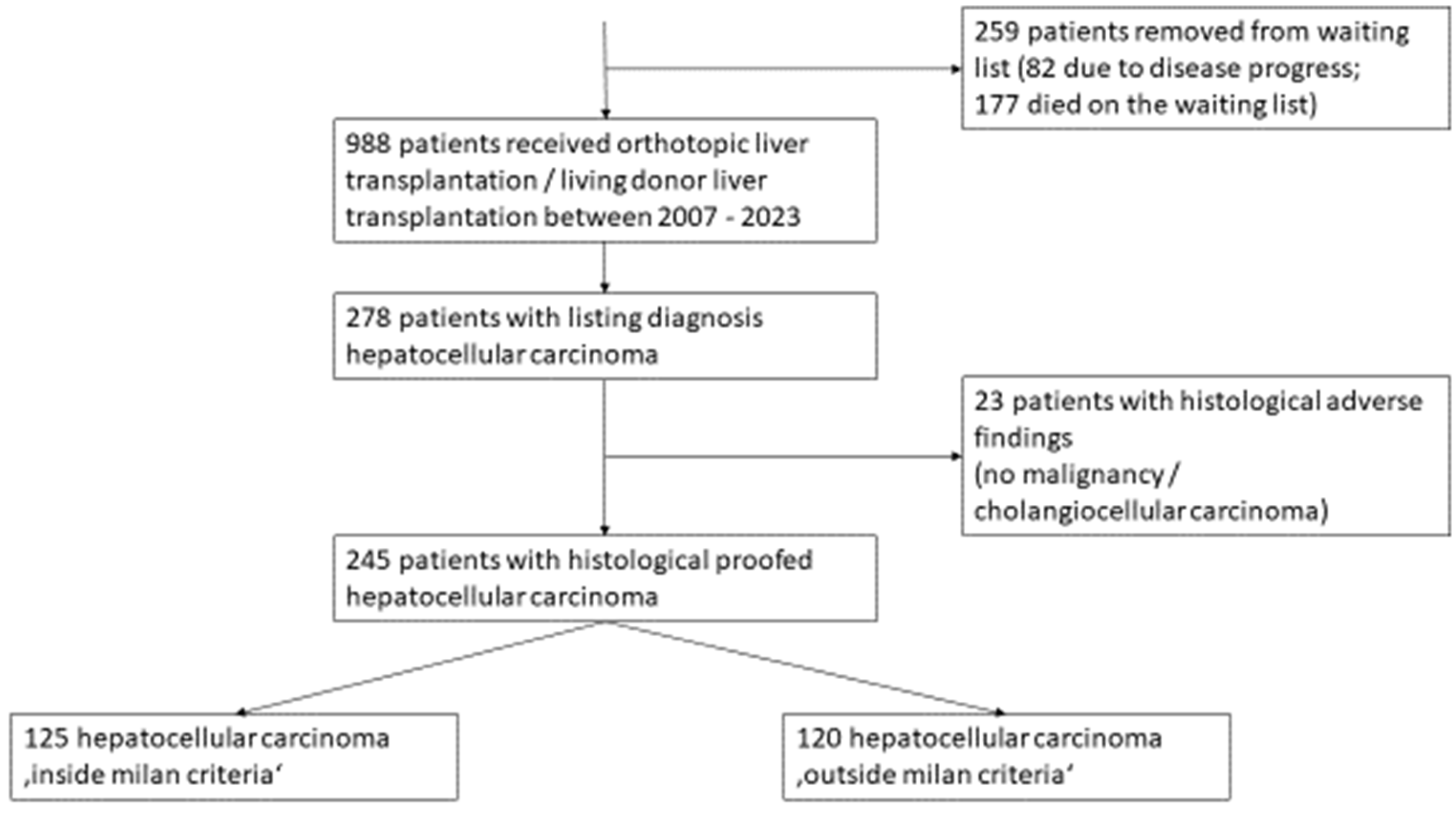

Patient selection

Outcome measures

Statistical analysis

Results

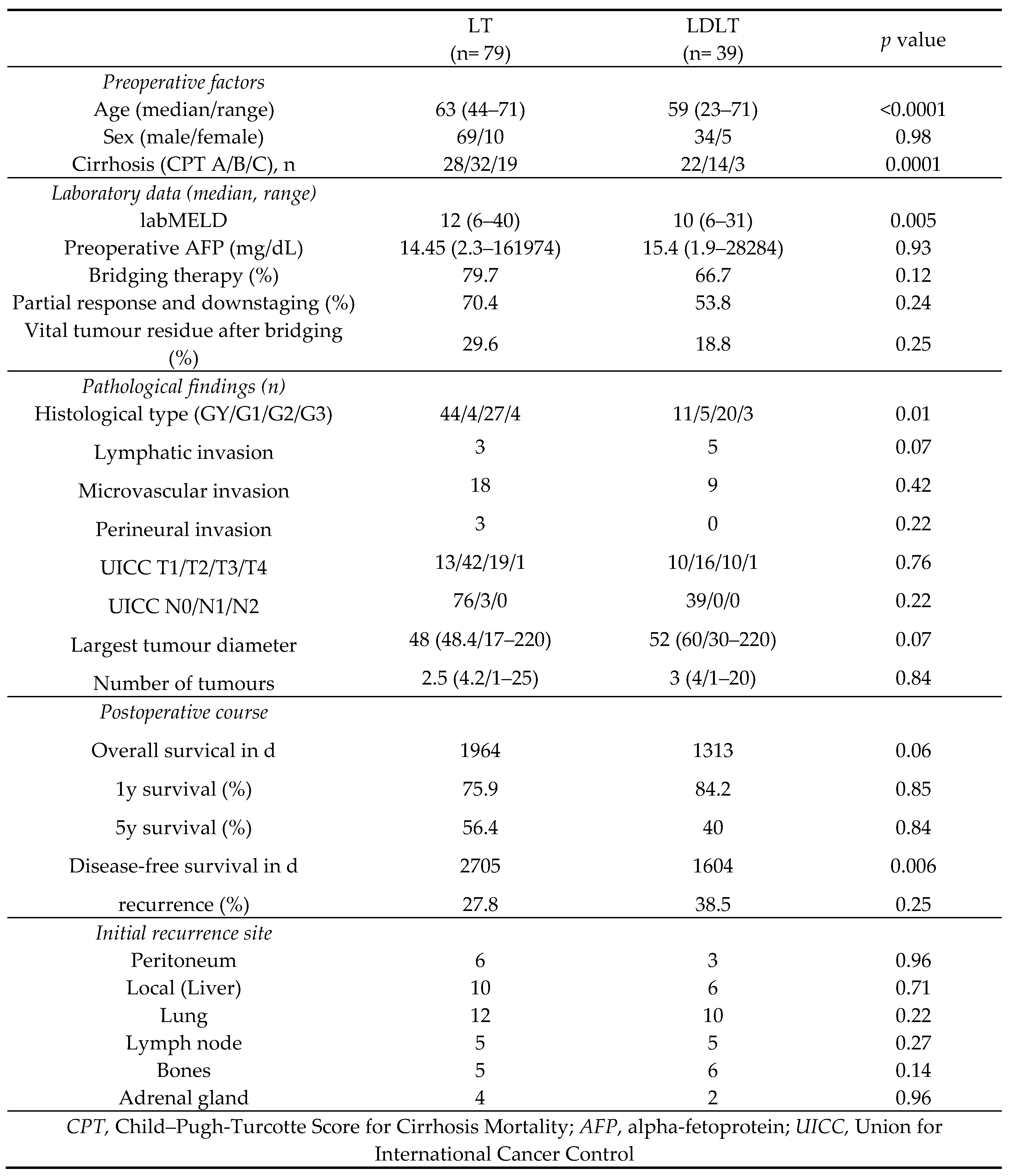

Epidemiology

Overall survival rate inside and outside the MC

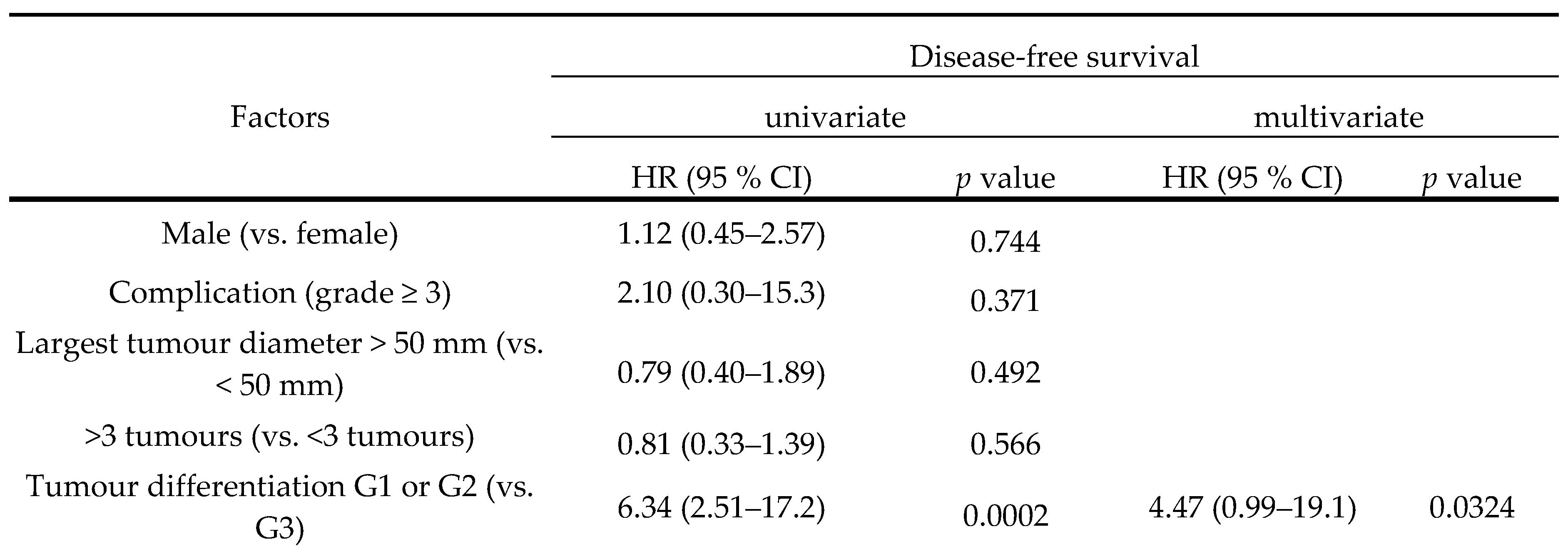

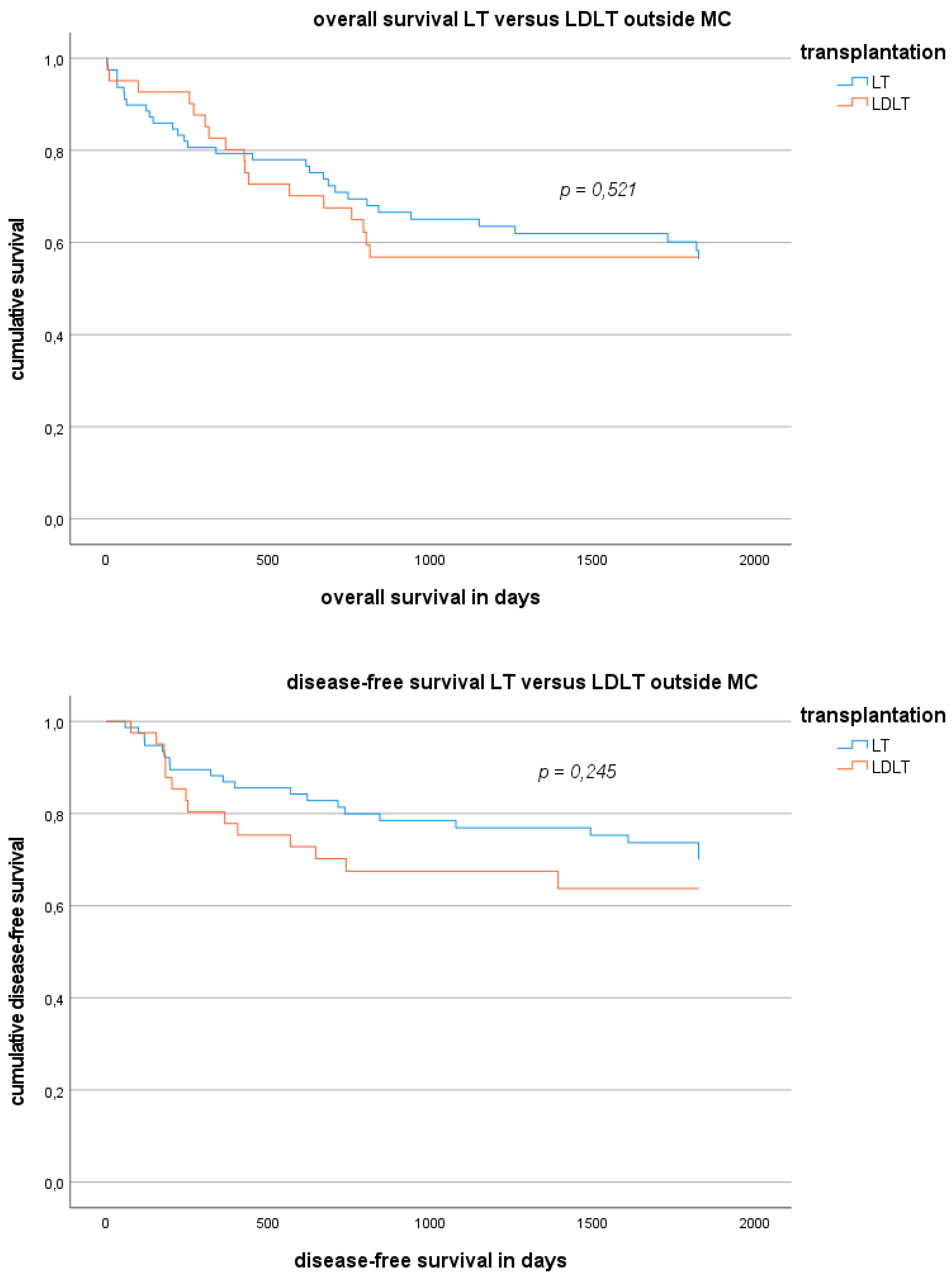

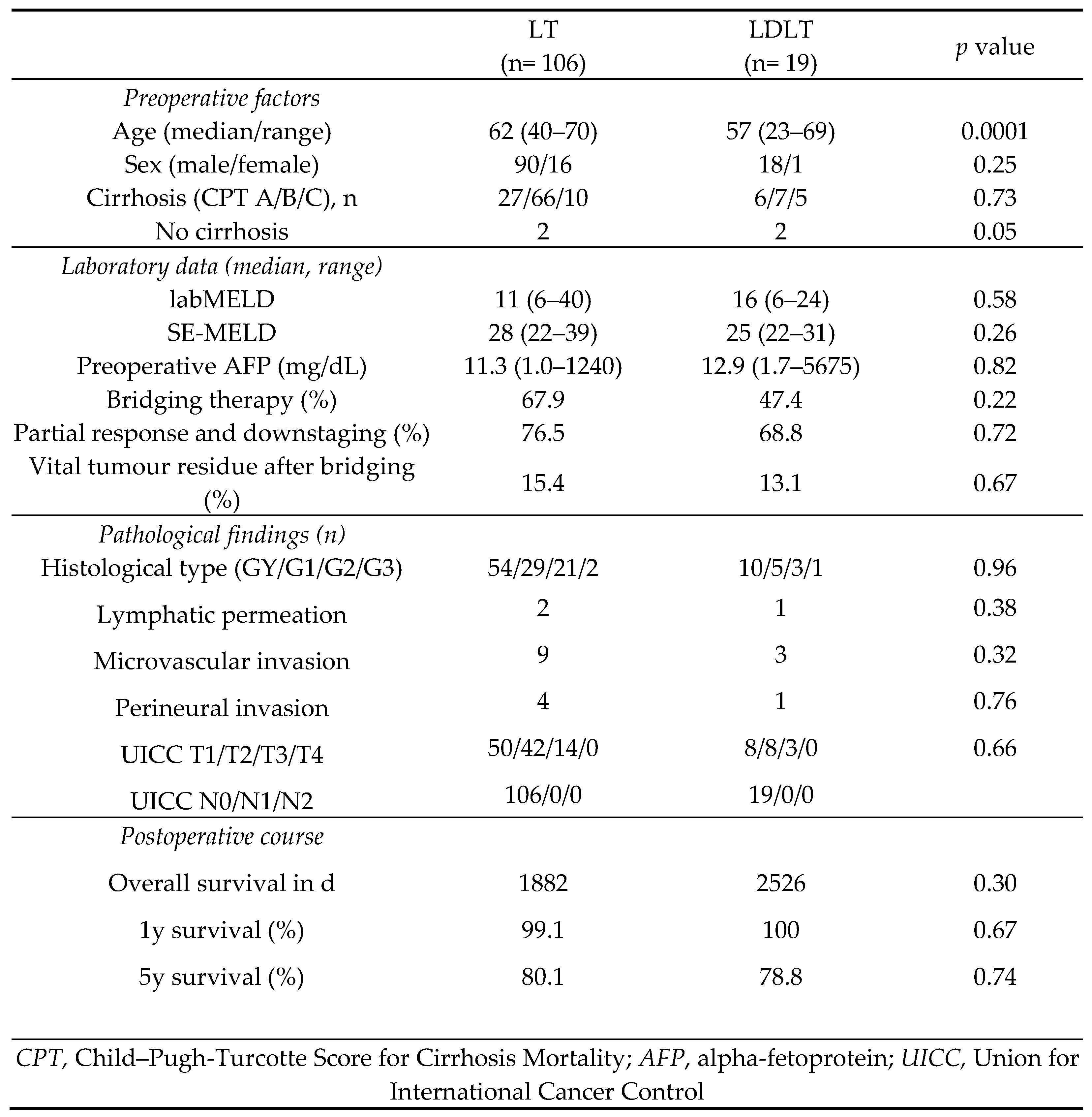

DFS and OS for patients who underwent LDLT or LT outside the MC

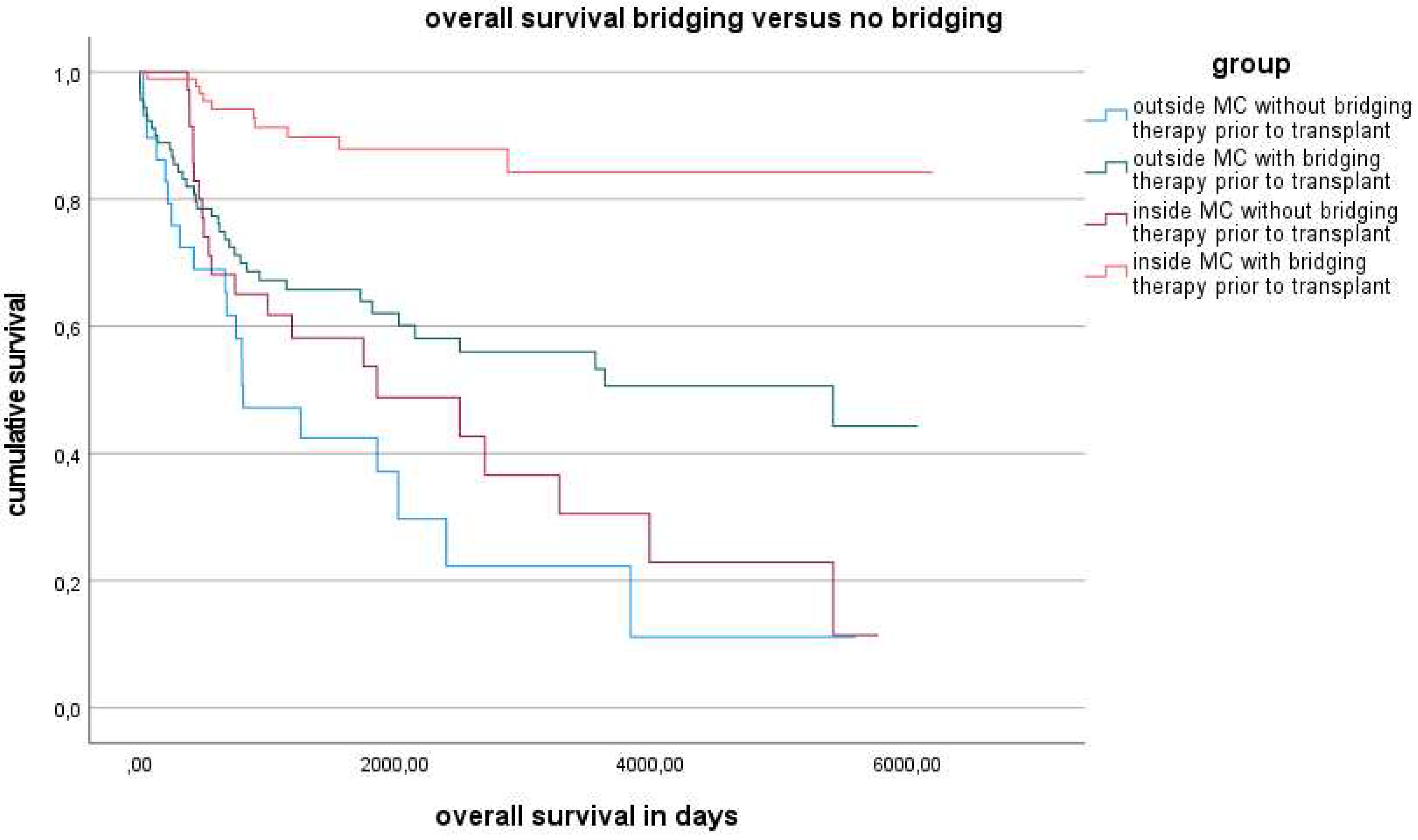

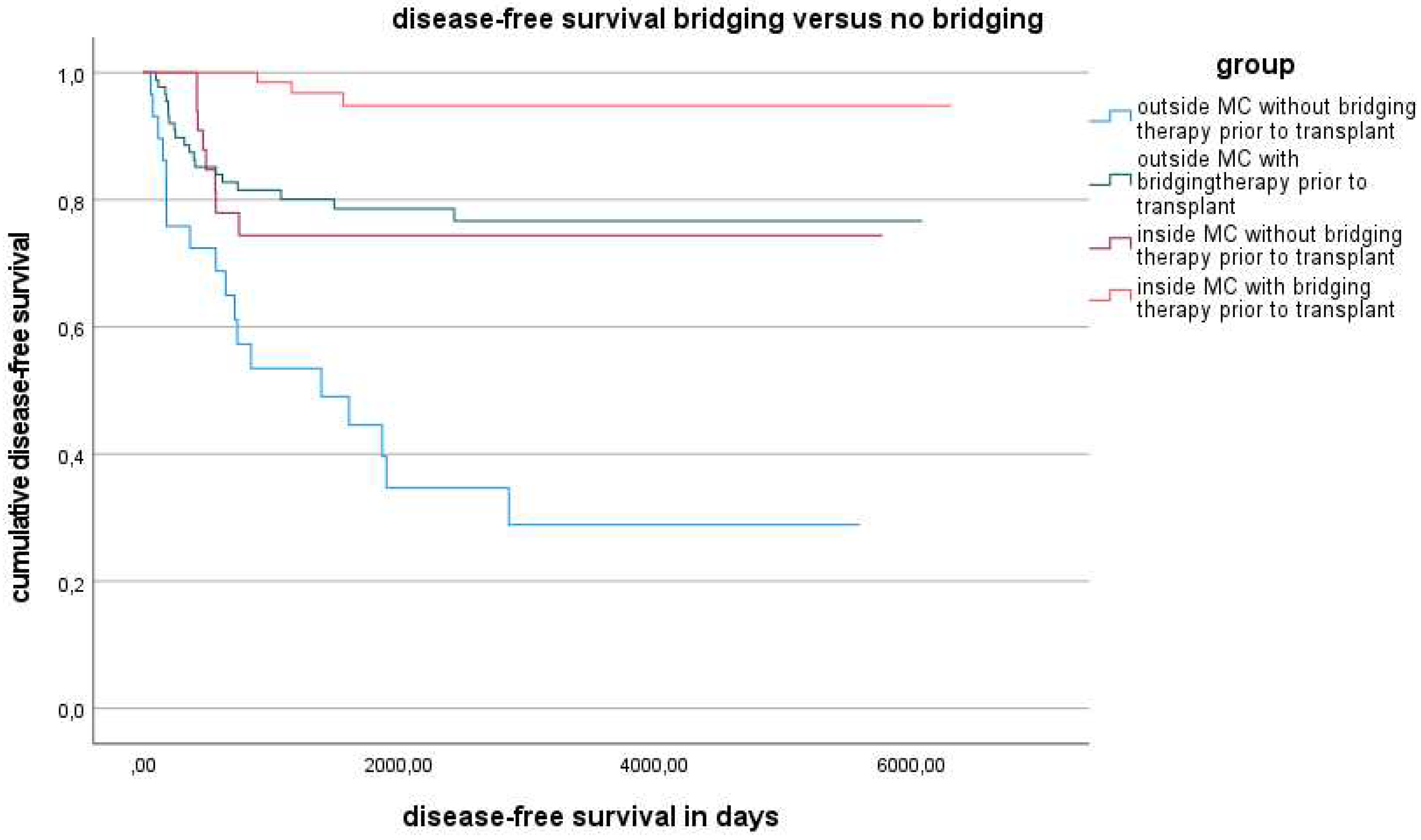

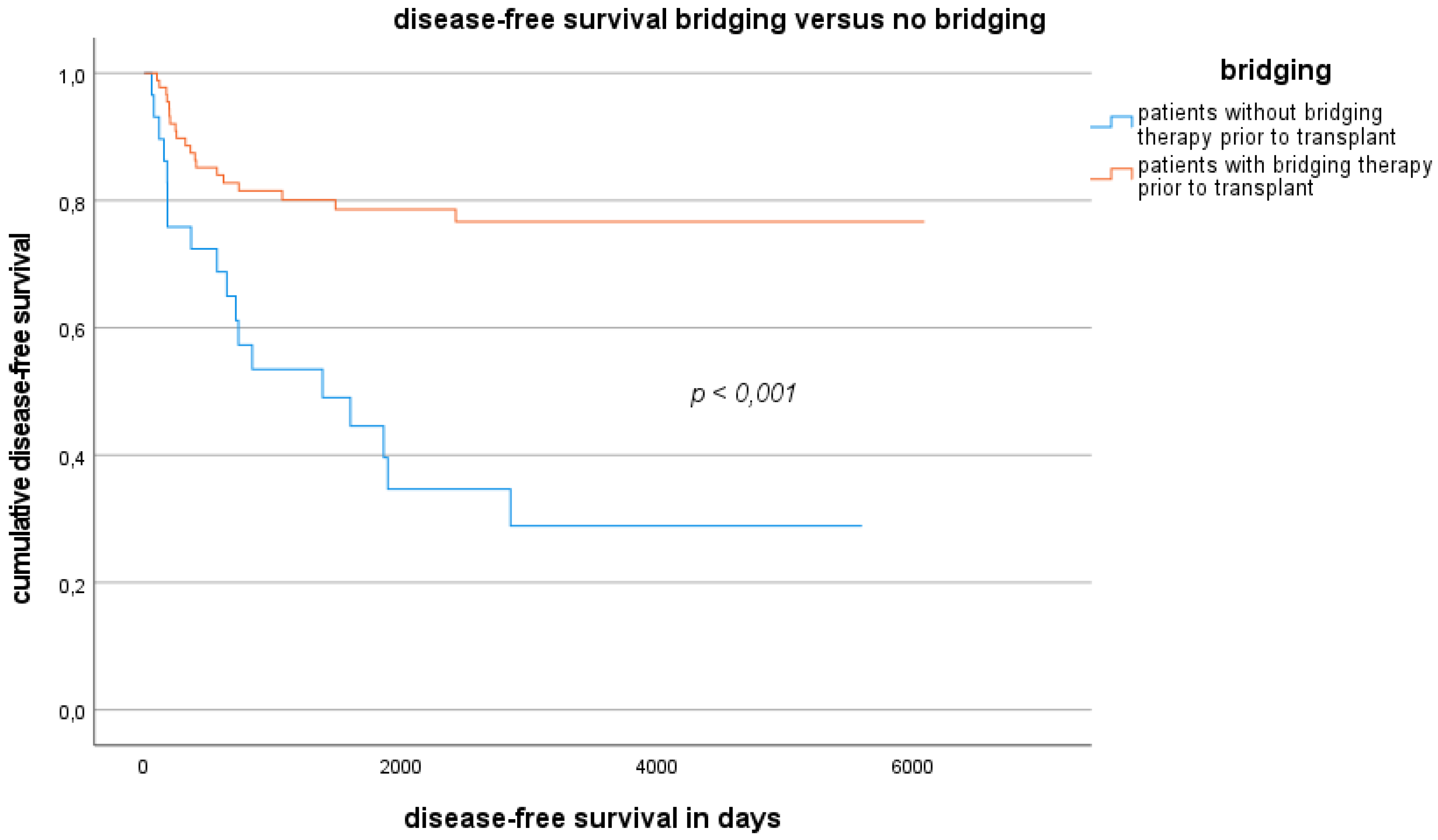

MELD score, tumour morphology and bridging response outside the MC

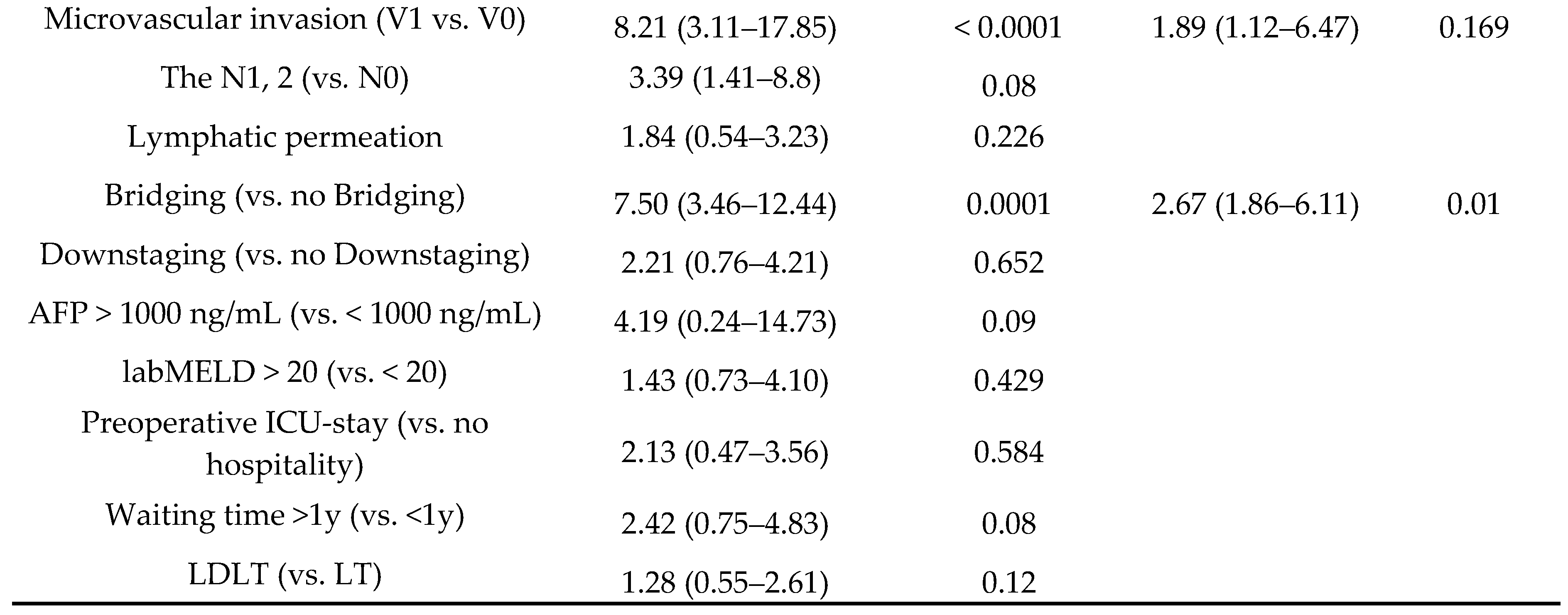

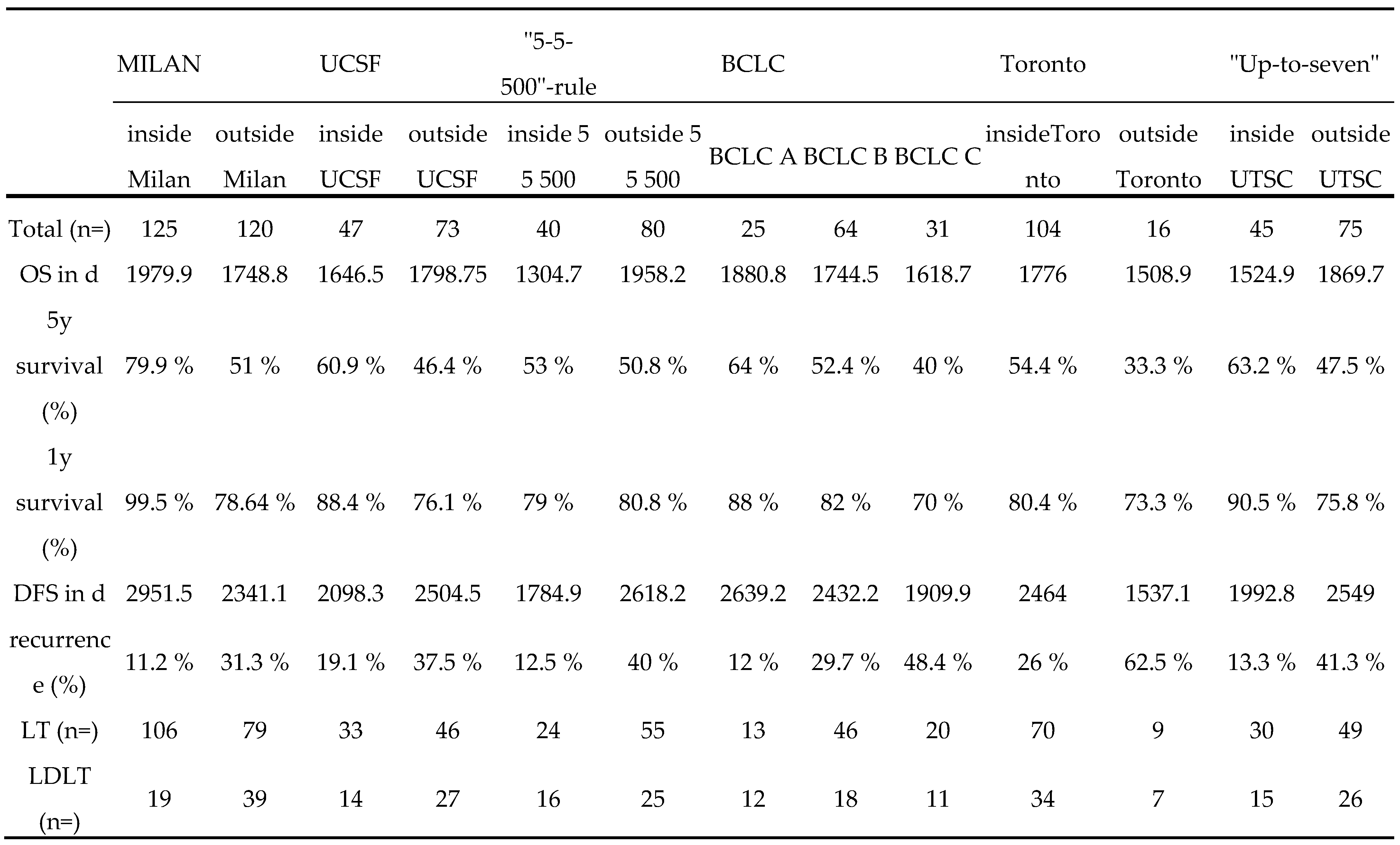

Results according to different classifications beyond the Milan grade

HCC waitlist dynamics

Discussion

Conclusion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Da, B.L. et al. Pathogenesis to management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes Cancer 13, 72–87 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Dopazo, C. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 50, 107313 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Mazzaferro, V. et al. Liver Transplantation for the Treatment of Small Hepatocellular Carcinomas in Patients with Cirrhosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 334, 693–700 (1996). [CrossRef]

- Mazzaferro, V. et al. Predicting survival after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria: a retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol. 10, 35–43 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Shehta, A. et al. Bridging and downstaging role of trans-arterial radio-embolization for expected small remnant volume before liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Surg. 24, 421–430 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., Hui, K.M., Shi, M., Reau, N. & Aloman, C. Differential expression of hepatic cancer stemness and hypoxia markers in residual cancer after locoregional therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol. Commun. 6, 3247–3259 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Ettorre, G.M. & Laurenzi, A. Liver Transplantation and Hepatobiliary Surgery, Interplay of Technical and Theoretical Aspects. 183–191 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q., Anwar, I.J., Abraham, N. & Barbas, A.S. Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Downstaging or Bridging Therapy with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Cancers 13, 6307 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Zori, A.G. et al. Locoregional Therapy Protocols With and Without Radioembolization for Hepatocellular Carcinoma as Bridge to Liver Transplantation. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 43, 325–333 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Makary, M.S., Bozer, J., Miller, E.D., Diaz, D.A. & Rikabi, A. Long-term Clinical Outcomes of Yttrium-90 Transarterial Radioembolization for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A 5-Year Institutional Experience. Acad. Radiol. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in HBV-Caused Hepatocellular Carcinoma Therapy. Vaccines 11, 614 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Wassmer, C.-H. et al. Immunotherapy and Liver Transplantation: A Narrative Review of Basic and Clinical Data. Cancers 15, 4574 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Wehrenberg-Klee, E., Goyal, L., Dugan, M., Zhu, A.X. & Ganguli, S. Y-90 Radioembolization Combined with a PD-1 Inhibitor for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 41, 1799–1802 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.Y. et al. Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Validation of the UCSF-Expanded Criteria Based on Preoperative Imaging. Am. J. Transplant. 7, 2587–2596 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Sapisochin, G. et al. The extended Toronto criteria for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective validation study. Hepatology 64, 2077–2088 (2016). [CrossRef]

- TAKISHIMA, T. et al. The Japanese 5-5-500 Rule Predicts Prognosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Hepatic Resection. Anticancer Res. 43, 1623–1629 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Reig, M. et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J. Hepatol. 76, 681–693 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Lubel, J.S., Roberts, S.K., Strasser, S.I. & Shackel, N. Australian recommendations for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Méd. J. Aust. 215, 334-334.e1 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Seehofer, D. et al. Patient Selection for Downstaging of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Prior to Liver Transplantation—Adjusting the Odds? Transpl. Int. 35, 10333 (2022). [CrossRef]

- DSO. Jahresbericht der deutschen Stiftung für Organspende https://dso.de/BerichteTransplantationszentren/Grafiken%20D%202021%20Leber.pdf (2021).

- Goldaracena, N. et al. Live donor liver transplantation for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma offers increased survival vs. deceased donation. J. Hepatol. 70, 666–673 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Nadalin, S. et al. Living donor liver transplantation in Europe. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutrition 5, 159–75 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Malinchoc, M. et al. A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology 31, 864–871 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Lencioni, R. & Llovet, J. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) Assessment for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis 30, 052–060 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 45, 228–247 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Vogel, A., Meyer, T., Sapisochin, G., Salem, R. & Saborowski, A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 400, 1345–1362 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Hameed, B., Mehta, N., Sapisochin, G., Roberts, J.P. & Yao, F.Y. Alpha-fetoprotein level > 1000 ng/mL as an exclusion criterion for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma meeting the Milan criteria. Liver Transplant. 20, 945–951 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.-H. et al. A Practical Risk Classification of Early Recurrence in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients with Microvascular invasion after Hepatectomy: A Decision Tree Analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 30, 363–372 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Toso, C. et al. Total tumor volume and alpha-fetoprotein for selection of transplant candidates with hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective validation. Hepatology 62, 158–165 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Bhangui, P. et al. Intention-to-treat analysis of liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Living versus deceased donor transplantation. Hepatology 53, 1570–1579 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.Y. et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Expansion of the tumor size limits does not adversely impact survival. Hepatology 33, 1394–1403 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Sotiropoulos, G.C. et al. Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: University Hospital Essen Experience and Metaanalysis of Prognostic Factors. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 205, 661–675 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Vakili, K. et al. Living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Increased recurrence but improved survival. Liver Transplant. 15, 1861–1866 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Sandro, S.D. et al. Living Donor Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Long-Term Results Compared With Deceased Donor Liver Transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 41, 1283–1285 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, L. et al. Living donor liver transplantation versus deceased donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Comparable survival and recurrence. Liver Transplant. 18, 315–322 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Park, M.-S. et al. Living-Donor Liver Transplantation Associated With Higher Incidence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Recurrence Than Deceased-Donor Liver Transplantation. Transplant. J. 97, 71–77 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S., Lee, S., Joh, J., Suh, K. & Kim, D. Liver transplantation for adult patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Korea: Comparison between cadaveric donor and living donor liver transplantations. Liver Transplant. 11, 1265–1272 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Sandri, G.B.L., Rayar, M., Qi, X. & Lucatelli, P. Liver transplant for patients outside Milan criteria. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 3, 81–81 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Ramos, F. et al. ECOG Performance Status Shows a Stronger Association with Treatment Tolerability Than Some Multidimensional Scales in Elderly Patients Diagnosed with Hematological Malignancies. Blood 136, 15–16 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Martino, M.D. et al. Comparison of Up-to-seven criteria with Milan Criteria for liver transplantation in patients with HCC. Trends Transplant. 14, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Rauchfuß, F. et al. Searching the ideal hepatocellular carcinoma patient for liver transplantation: are the Toronto criteria a step in the right direction? Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 6, 342–343 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.-S. et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Hangzhou experiences. Transplantation 85, 1726–32 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Yan, P. & Yan, L.-N. Staging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int.: HBPD INT 2, 491–5 (2003).

- Yap, A.Q. et al. Clinicopathological factors impact the survival outcome following the resection of combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Oncol 22, 55–60 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, A.B.H. et al. Living donor liver transplantation for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma including macrovascular invasion. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 148, 245–253 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-C. & Chen, C.-L. Living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma achieves better outcomes. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutrition 5, 415–421 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, A.B.H., Waheed, A. & Khan, N.A. Living Donor Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Appraisal of the United Network for Organ Sharing Modified TNM Staging. Front. Surg. 7, 622170 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.C.L. et al. Long-Term Survival Outcome Between Living Donor and Deceased Donor Liver Transplant for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Intention-to-Treat and Propensity Score Matching Analyses. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 26, 1454–1462 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.Y., Wang, W.T. & Yan, L.N. Hangzhou criteria for liver transplantation in hepatocellular carcinoma: a single-center experience. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 26, 200–204 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Ivanics, T. et al. Living Donor Liver Transplantation (LDLT) for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) within and Outside Traditional Selection Criteria: A Multicentric North American Experience. Ann. Surg. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Xu, X., Ling, Q., Wu, J. & Zheng, S. Role of Pittsburgh modified TNM criteria in prognosis prediction of liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Chin. Méd. J. 120, 2200–3 (2007). [CrossRef]

- PONS, F., VARELA, M. & LLOVET, J.M. Staging systems in hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB 7, 35–41 (2005). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).