Submitted:

18 January 2024

Posted:

19 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fuel parameters

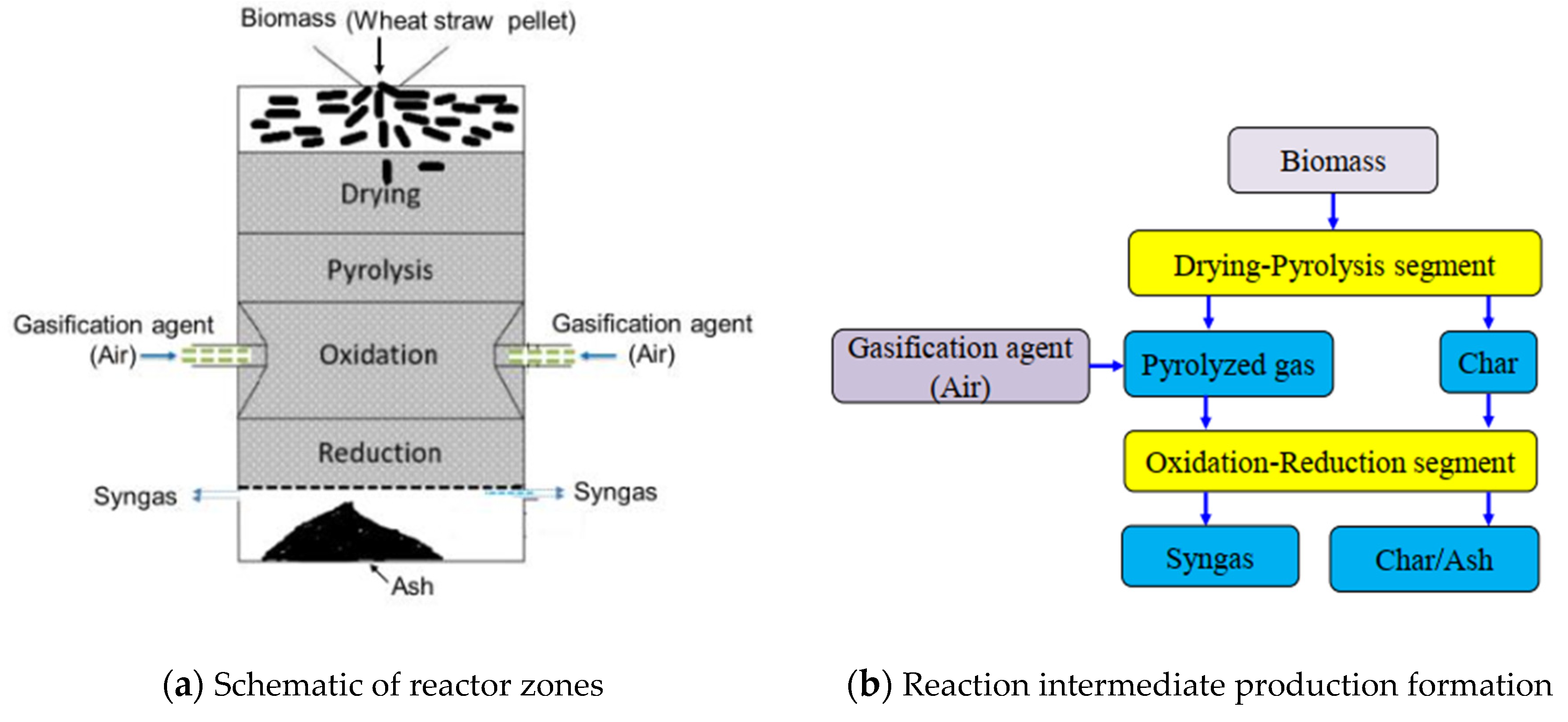

2.2. Reactor - the central part of the gasifier

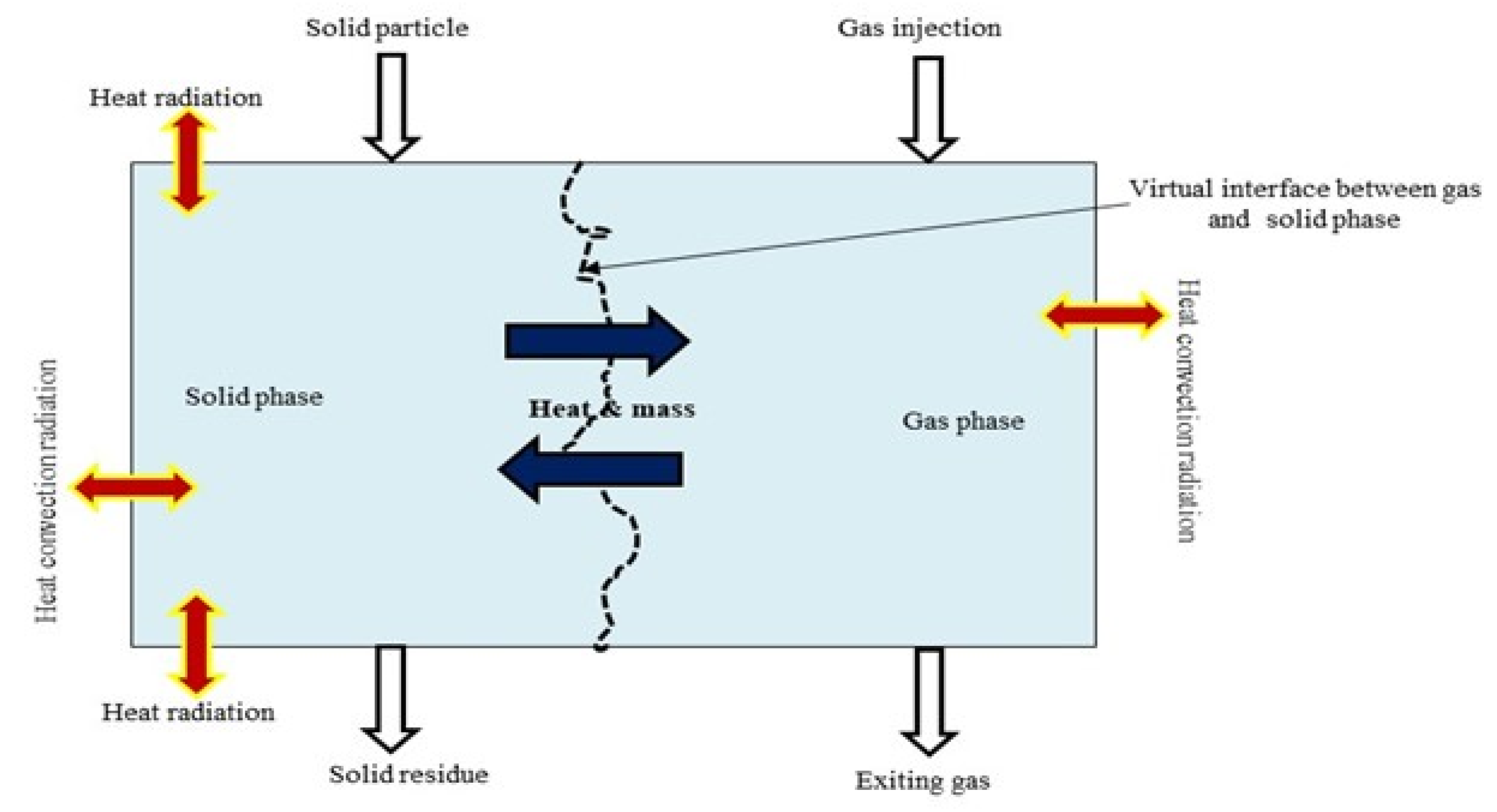

2.2. Modelling theory - thermochemical conversion of solid fuel

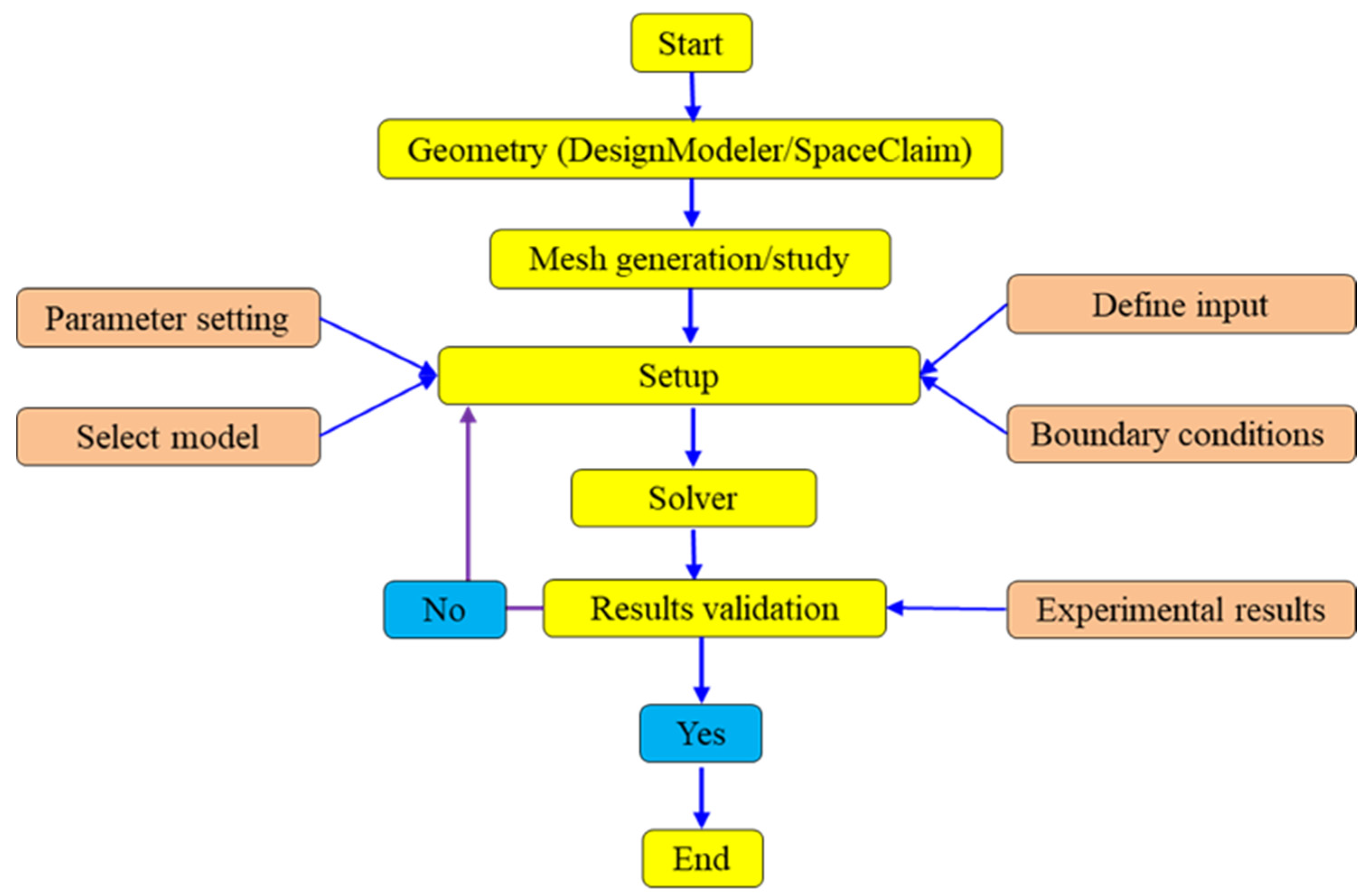

2.3. CFD model development

- A.

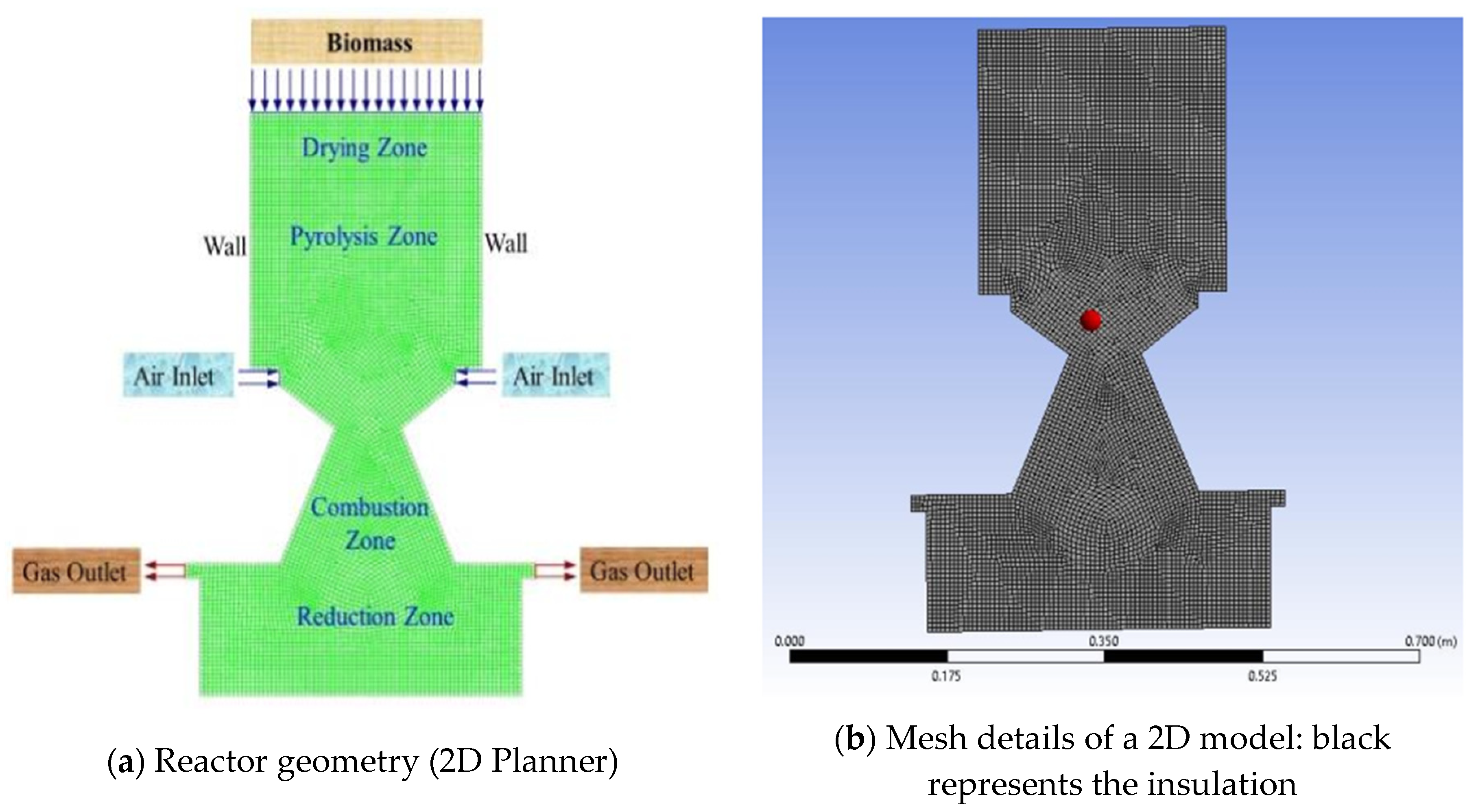

- Geometry construction

- B.

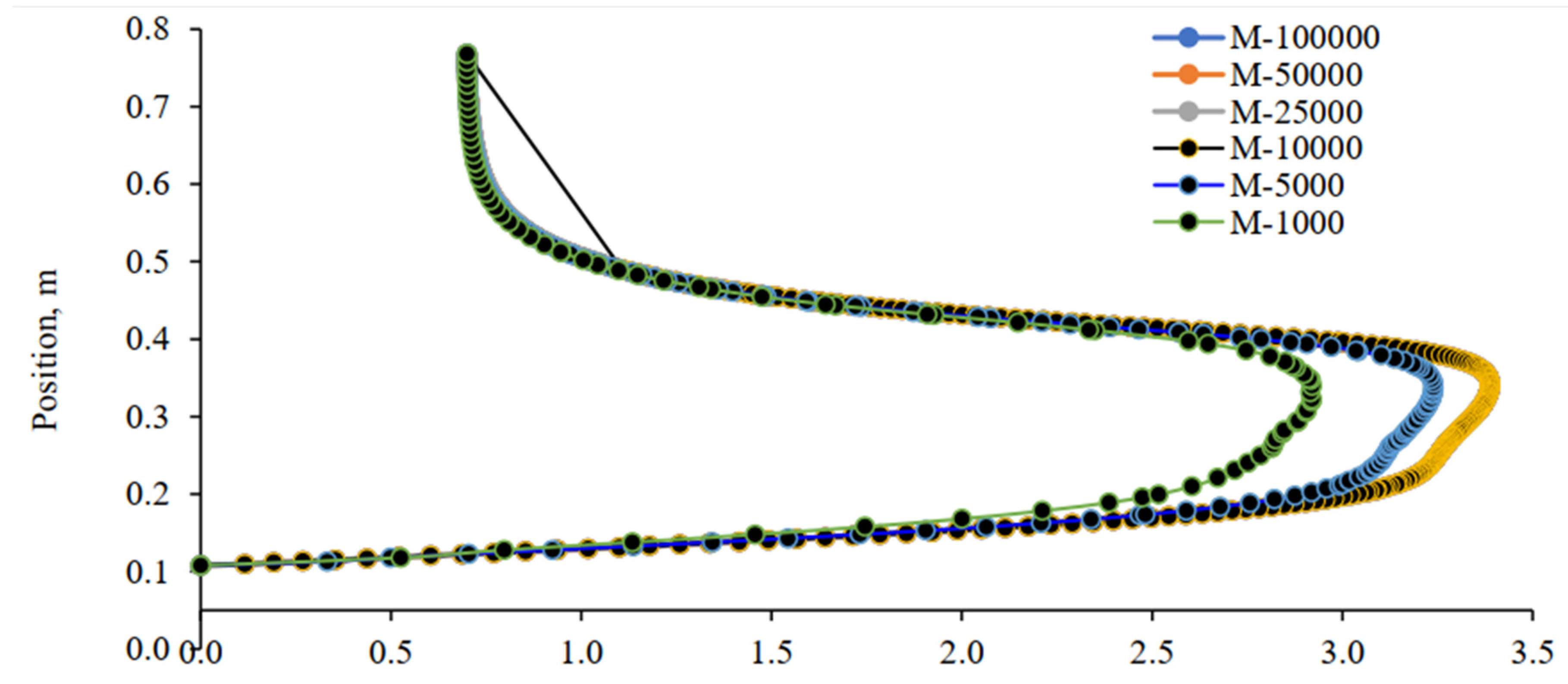

- Mesh generation

- C.

- Model setting

- -

- Model selection

- -

- Model simplifications

2.3. Solution of model-based equations

- i.

- Governing equation: pressure velocity coupling method

- ii.

- Energy and species transport equation

- iii.

- Particle combustion model

- -

- Force balance equation

- -

- Particleheatbalance equation

- -

- Heattransferduring the devolatilisation process

- -

- Heat transfer during the char conversion process

- iv.

- Radiation model

- v.

- Chemical Reaction model

2.3. Boundary and operating conditions setup

2.3. Input data for simulations

2.3. Numerical calculation

3. Results and discussion

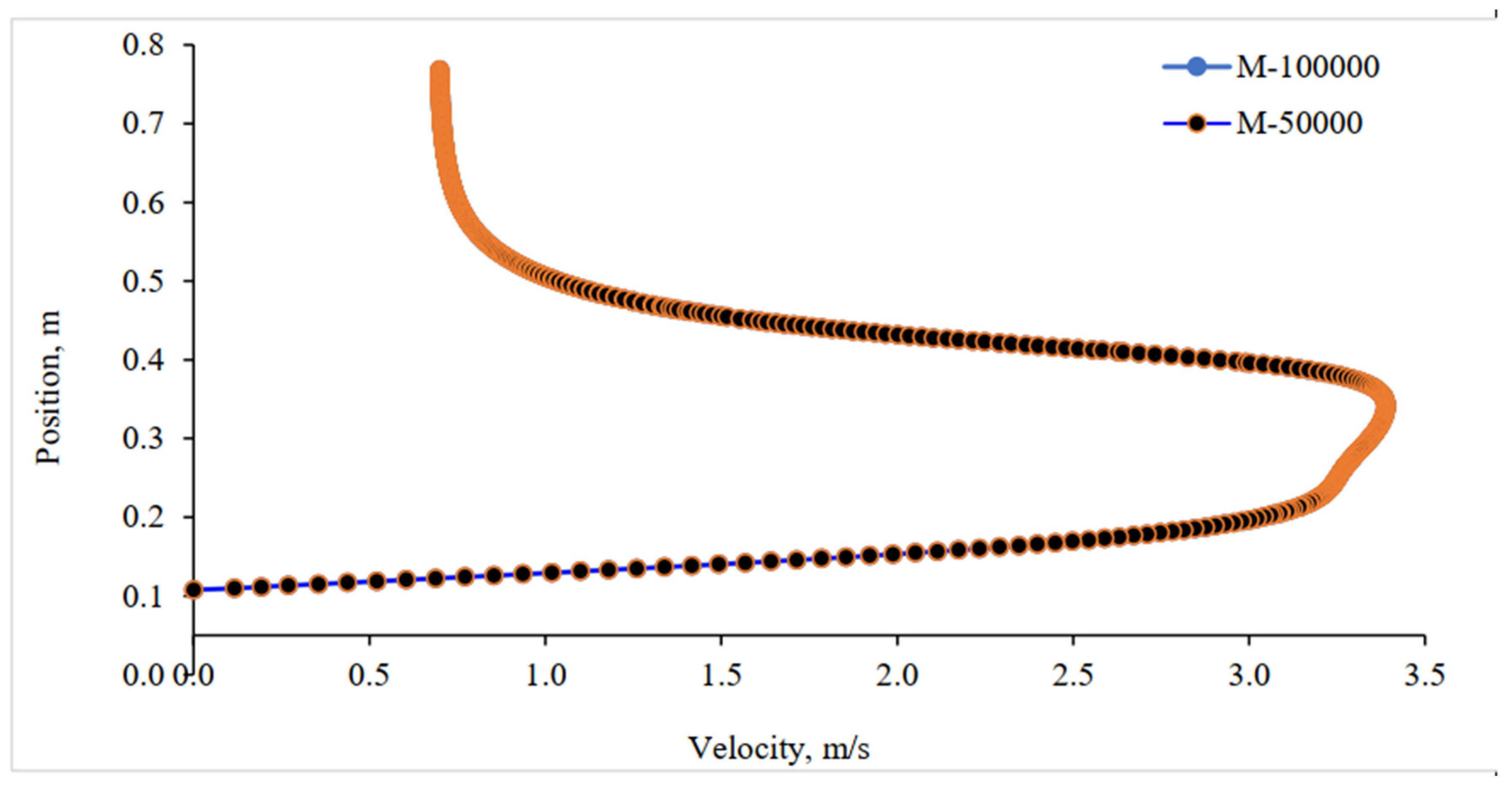

3.1. Grid sensitivity analysis

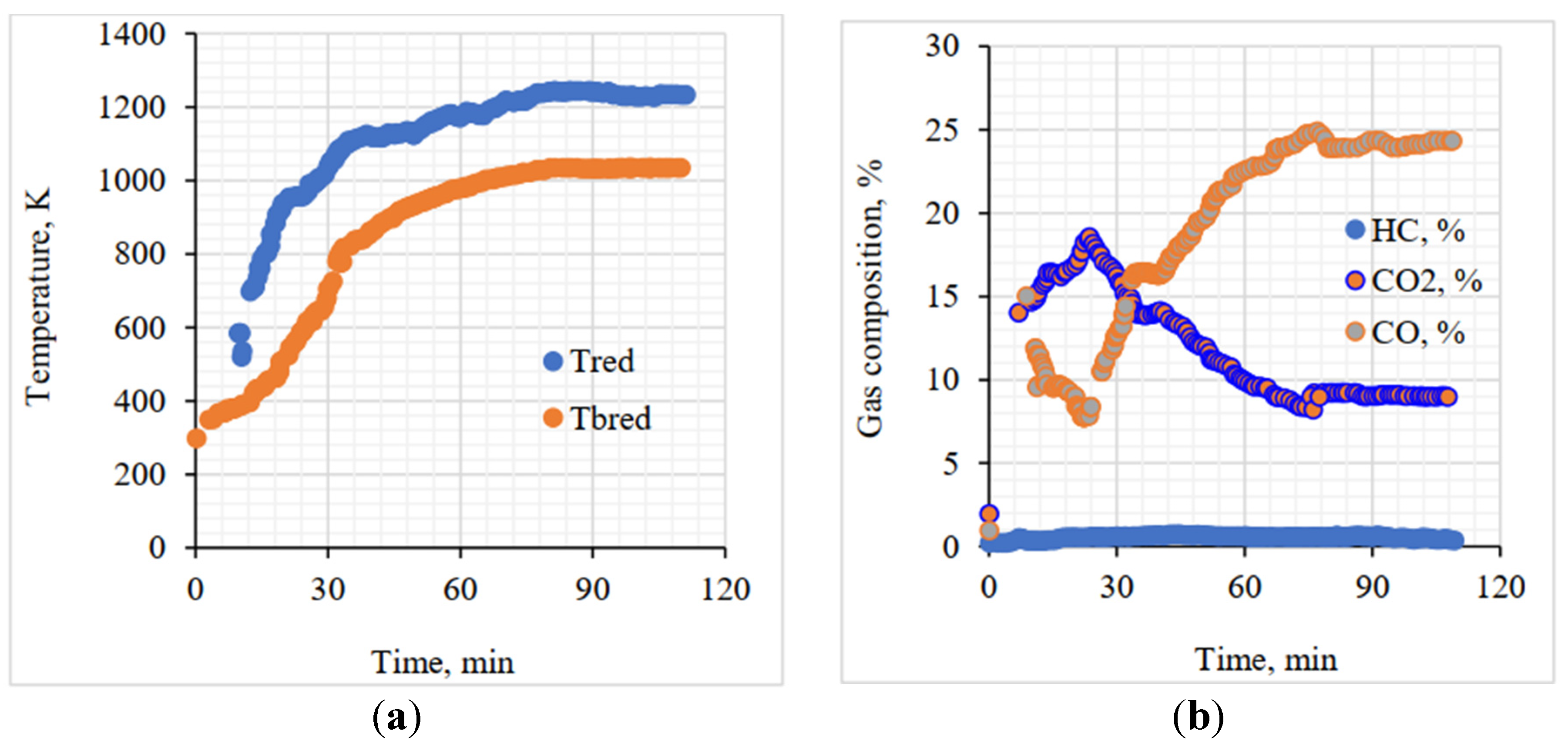

3.2. Model validation and comparison

3.2.1. Experimental details on gasification

3.2. Prediction profile and gas distribution

- -

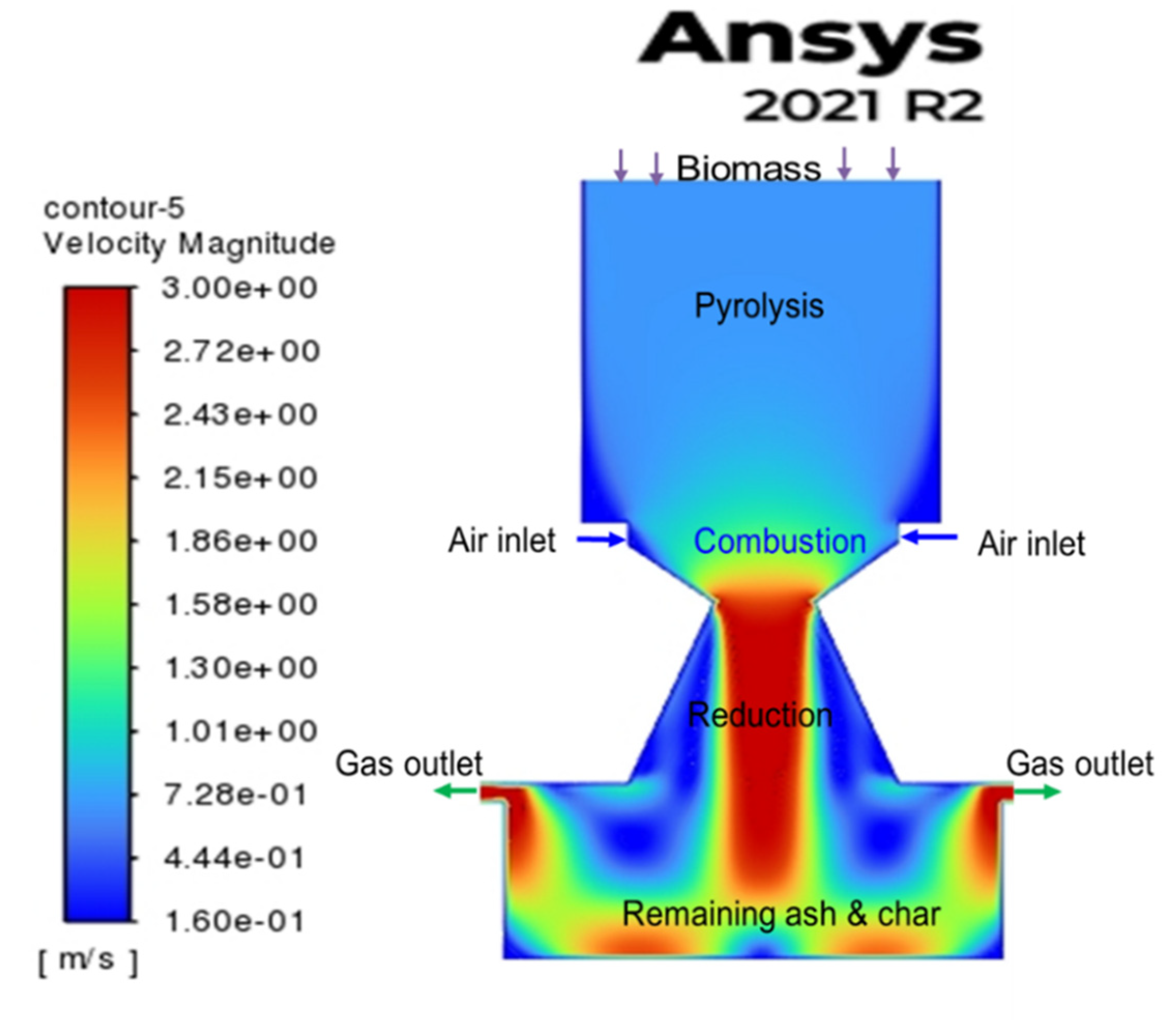

- Velocity profile

- -

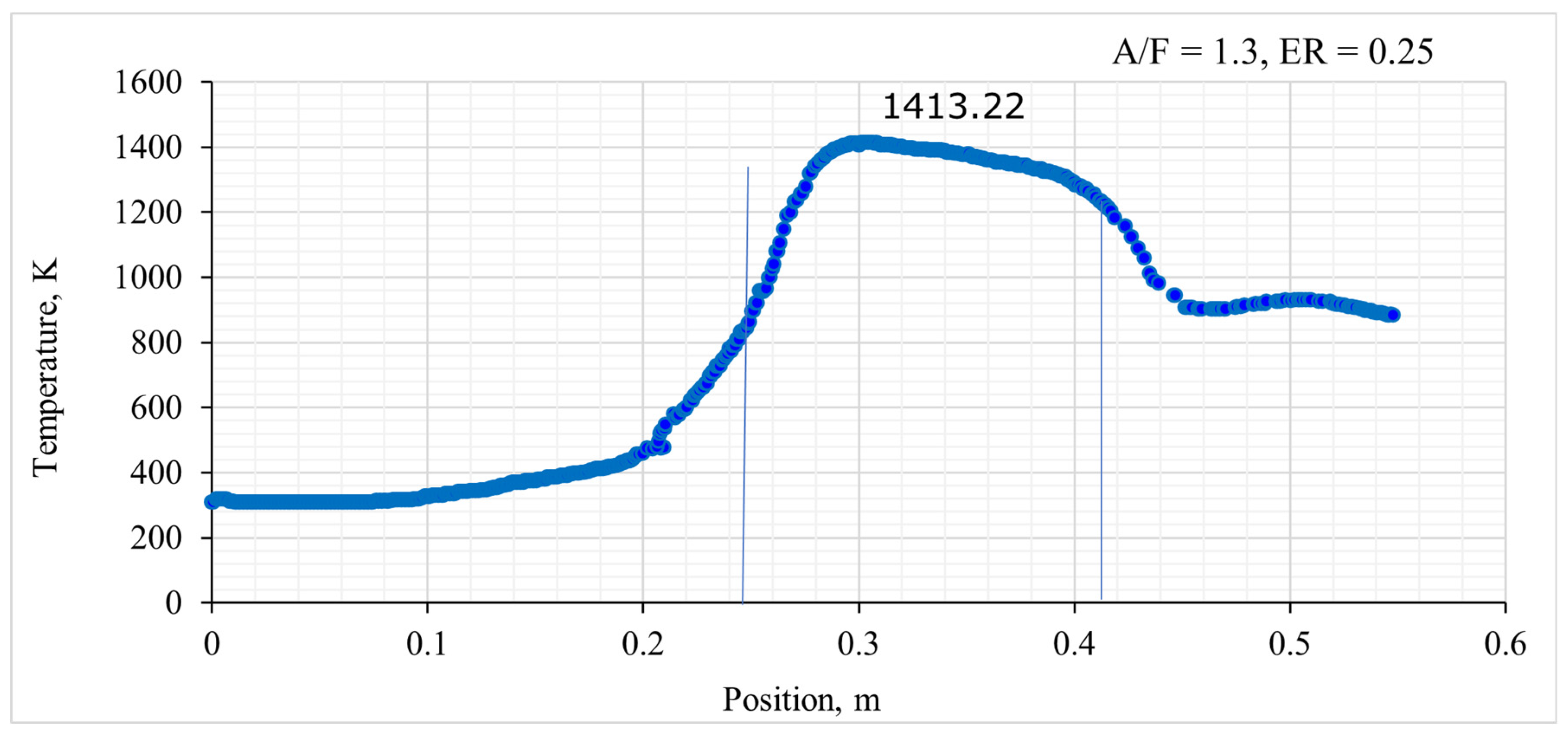

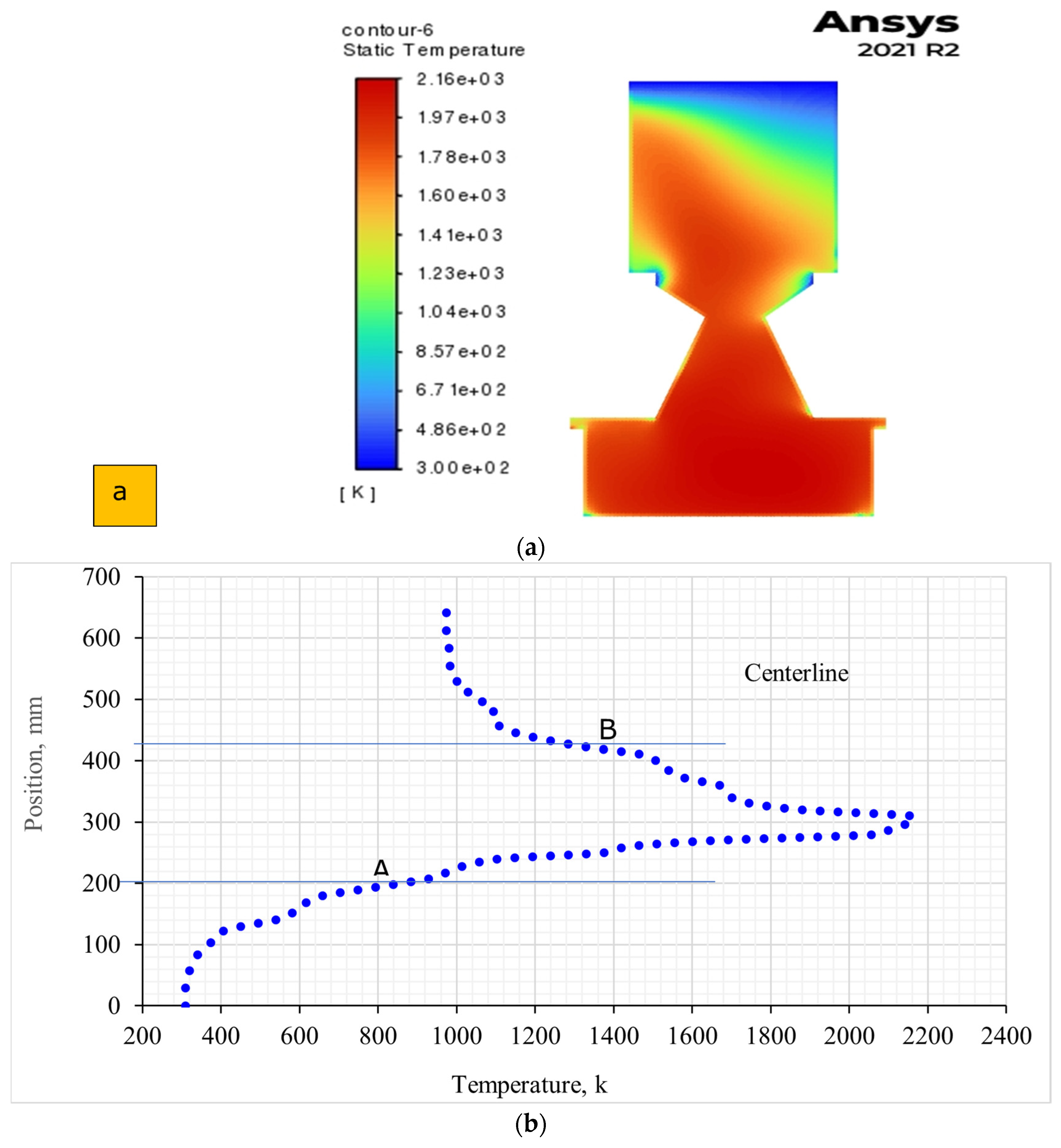

- Temperature profile

- -

- Model limitation for temperature

- -

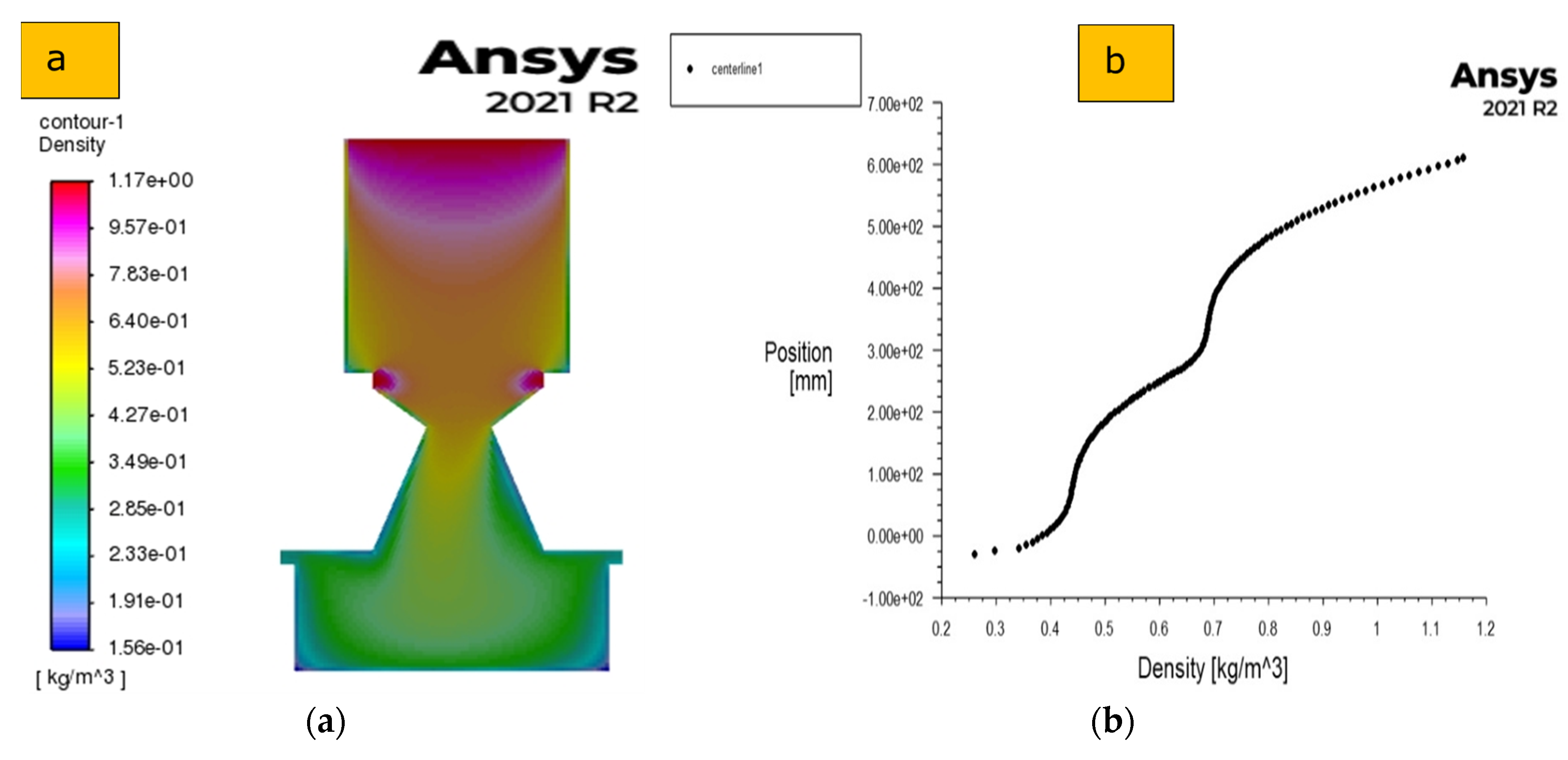

- Gas density profile

- -

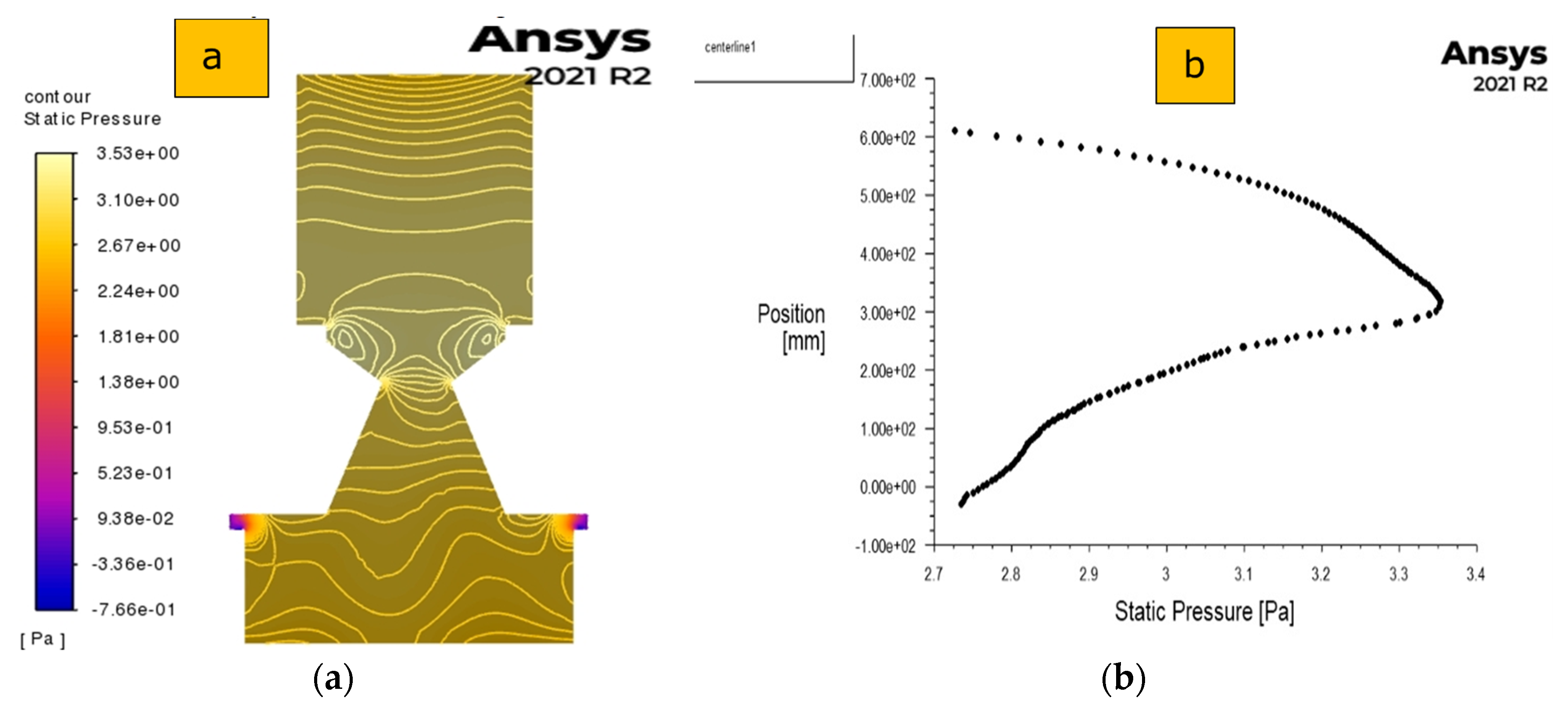

- Pressure profile

- -

- Gas species profile

- -

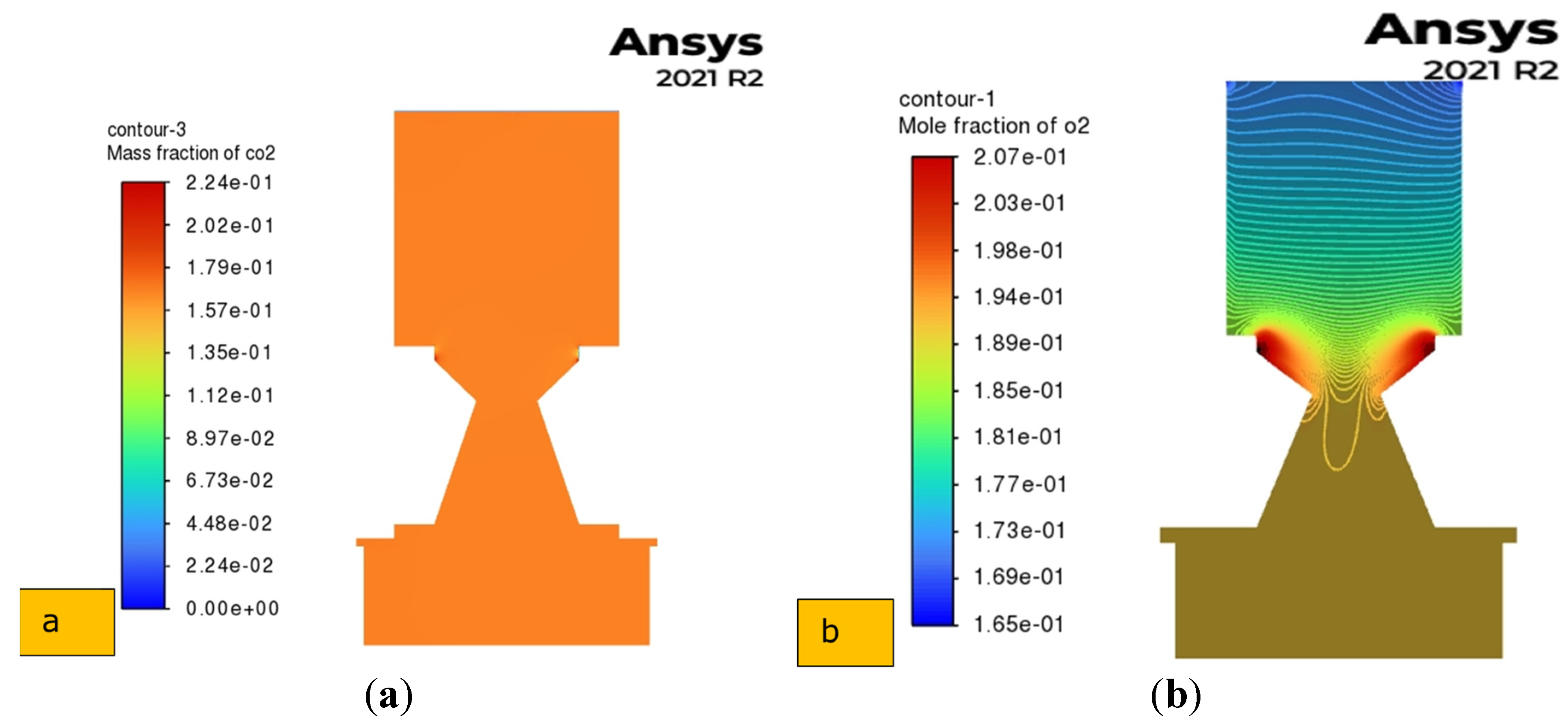

- CO2 and O2 profile

- -

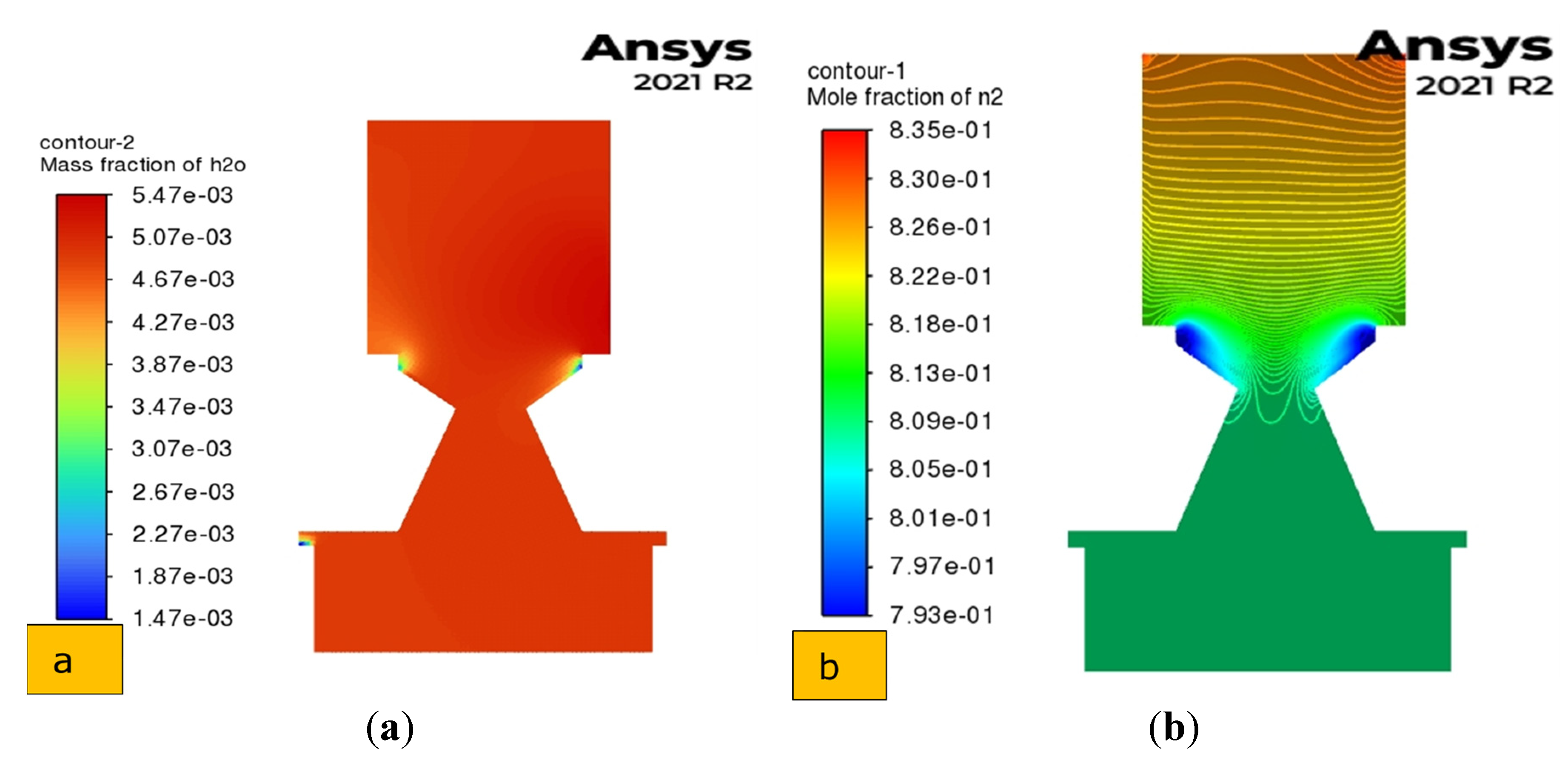

- H2O and N2 mole fraction profile

3.2. Performance study

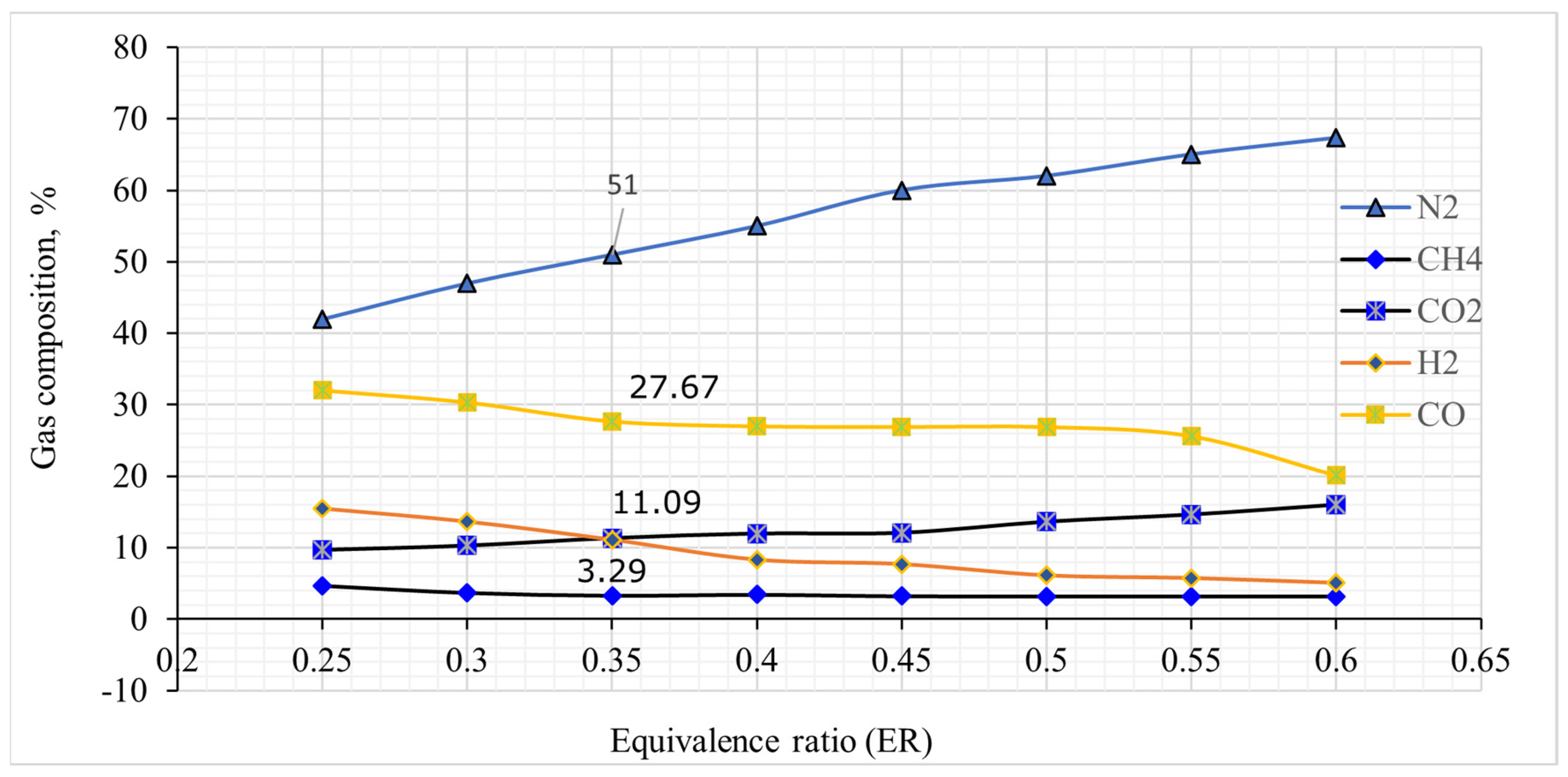

3.2.1. Effect of ER on gas composition

3.2.1. Gas production and gas efficiency

| Items | Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER, % | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.60 |

| LHV, MJ/m3 | 7.65 | 6.86 | 6.09 | 5.74 | 5.57 | 5.39 | 5.18 | 4.38 |

| , % | 64~100 | 58~90 | 51~80 | 48~75 | 47~73 | 45~71 | 43~68 | 37~57 |

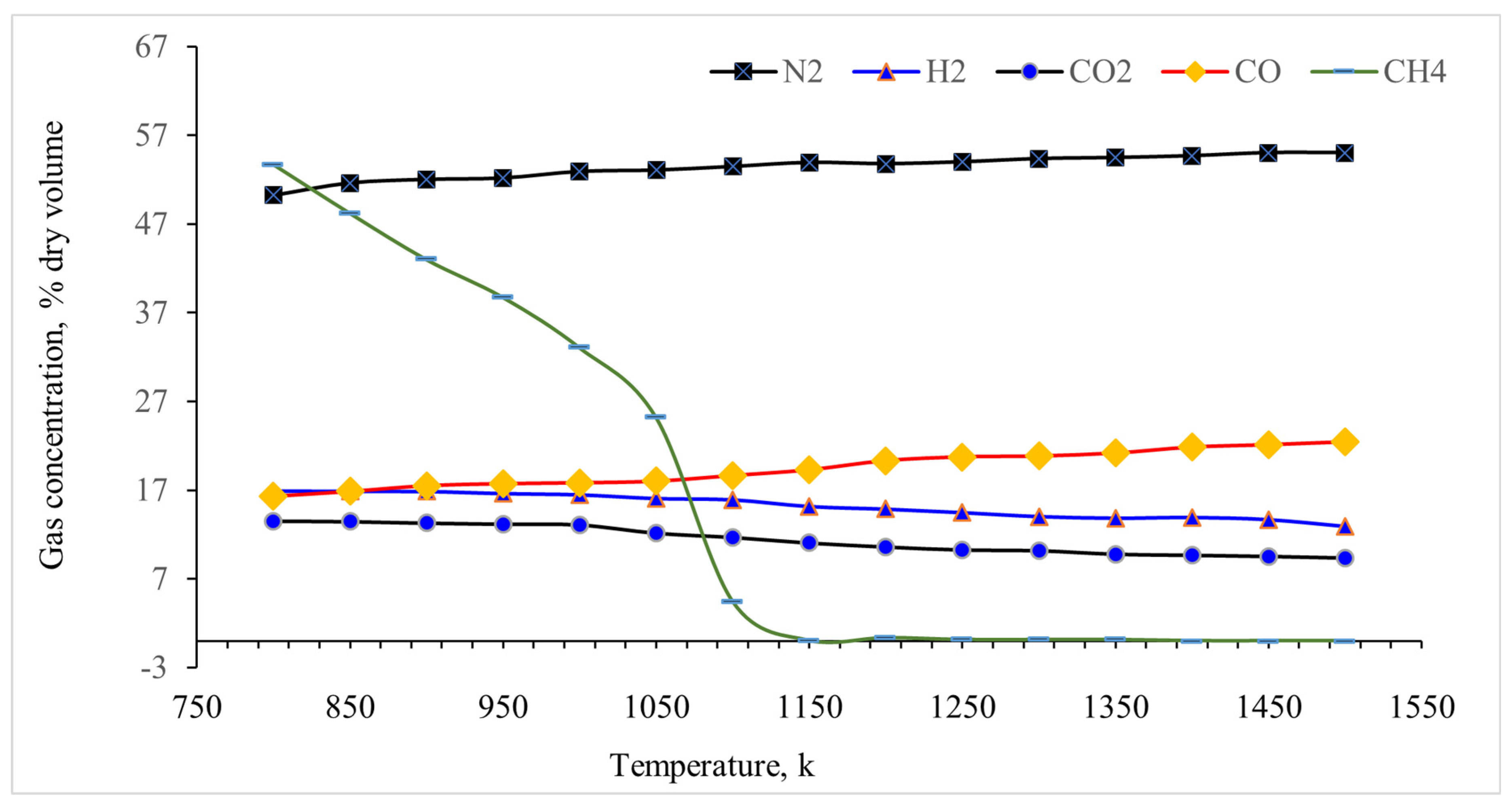

3.2.1. Effect of temperature on syngas species concentration

4. Conclusions

- ▪

- A higher temperature zone prevails beneath the air injection zone.

- ▪

- Changes in the Equivalence Ratio influenced the heating value of gas and gas production efficiency.

- ▪

- An ER of 0.35 appeared optimal for syngas production, resulting in CO at 27.67% and H2 at 11.09%. Increased ER led to a decrease in CO and H2 composition, accompanied by an increase in CO2 concentration.

- ▪

- A higher equivalence ratio (0.25~0.6) is responsible for the high nitrogen content (42~67.3%) in producer gas.

- ▪

- The proposed CFD model offered an initial estimation of producer gas composition, aiding in controlling operating parameters during real experiments.

- ▪

- Simulation work proved beneficial for improve the gasifier's design parameters and enhancing the performance of the gasifier.

Nomenclature

|

density of the fluid mixture mass fraction of species K in the fluid mixtures = fluctuation dilation in compressible turbulence volume force acting on species k in the j direction coordinates axes = dynamic viscosity of the mixture the i-component of the diffusion velocity of species K energy flux in the mixture total energy from chemical, potential and kinetic energies = energy flux from the outer heating source = source term for the ith (x, y, z) momentum equation = specific heat at constant pressure = net rate of production of species, i = net rate of production of species “i” by chemical reaction = specific heat = turbulence kinetic energy due to buoyancy C = linear-anisotropic phase function coefficient = latent heat of evaporation = Stefan constant, respectively. (- ) = drag force per unit particle mass. |

t = time pressure velocity components the viscus stress tensor = the tensor unit. the reaction rate of species k = user-defined source terms for k = user-defined source term for ϵ = turbulent Prandtl numbers for k = turbulent Prandtl numbers for h = sensible enthalpy H = latent heat enthalpy = reference enthalpy = reference temperature species i's average mass = volatile fraction = initial mass = absorption coefficient, = Stefan-Boltzmann constant, G = incident radiation, and A = particle surface area |

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest

References

- Gupta, R., P. Jain, and S. Vyas, CFD modeling and simulation of 10 kWe Biomass Downdraft gasifier. Int. J. Curr. Eng. Technol. 2017, 7, 1446–1452. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, B.; Prajapati, Y.K.; Sheth, P.N. CFD analysis of biomass gasification using downdraft gasifier. Mater. Today: Proc. 2020, 44, 4107–4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrenfeldt, J.; Thomsen, T.P.; Henriksen, U.; Clausen, L.R. Biomass gasification cogeneration – A review of state of the art technology and near future perspectives. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2013, 50, 1407–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahng, M.-K.; Mukarakate, C.; Robichaud, D.J.; Nimlos, M.R. Current technologies for analysis of biomass thermochemical processing: A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2009, 651, 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caputo, A.C.; Palumbo, M.; Pelagagge, P.M.; Scacchia, F. Economics of biomass energy utilization in combustion and gasification plants: effects of logistic variables. Biomass- Bioenergy 2005, 28, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahromi, R.; Rezaei, M.; Samadi, S.H.; Jahromi, H. Biomass gasification in a downdraft fixed-bed gasifier: Optimization of operating conditions. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2020, 231, 116249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susastriawan, A.; Saptoadi, H. ; Purnomo Small-scale downdraft gasifiers for biomass gasification: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 76, 989–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, D. Modeling of biomass gasification: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, T.K.; Sheth, P.N. Biomass gasification models for downdraft gasifier: A state-of-the-art review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 50, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanavath, K.N. , et al., Oxygen–steam gasification of karanja press seed cake: Fixed bed experiments, ASPEN Plus process model development and benchmarking with saw dust, rice husk and sunflower husk. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 3061–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Villetta, M.; Costa, M.; Massarotti, N. Modelling approaches to biomass gasification: A review with emphasis on the stoichiometric method. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 74, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.Y.; Ahmad, M.M.; Yusup, S.; Inayat, A.; Khan, Z. Mathematical and computational approaches for design of biomass gasification for hydrogen production: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 2304–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Elkamel, A.; Lohi, A.; Biglari, M. Computational Fluid Dynamics Modeling of Biomass Gasification in Circulating Fluidized-Bed Reactor Using the Eulerian–Eulerian Approach. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 18162–18174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chogani, A.; Moosavi, A.; Sarvestani, A.B.; Shariat, M. The effect of chemical functional groups and salt concentration on performance of single-layer graphene membrane in water desalination process: A molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 301, 112478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, L. CFD Studies on Biomass Thermochemical Conversion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2008, 9, 1108–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, W.; Blasiak, W. Two-Dimensional Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulation of Biomass Gasification in a Downdraft Fixed-Bed Gasifier with Highly Preheated Air and Steam. Energy Fuels 2013, 27, 3274–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepiot, P., C. J. Dibble, and T.D. Foust, Computational Fluid Dynamics Modeling of Biomass Gasification and Pyrolysis, in Computational Modeling in Lignocellulosic Biofuel Production. 2010. p. 273-298.

- Fernando, N.; Narayana, M. A comprehensive two dimensional Computational Fluid Dynamics model for an updraft biomass gasifier. Renew. Energy 2016, 99, 698–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shafay, A.; Hegazi, A.; Zeidan, E.; El-Emam, S.; Okasha, F. Experimental and numerical study of sawdust air-gasification. Alex. Eng. J. 2020, 59, 3665–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, J.; Liu, H.; Li, J. An overview of CFD modelling of small-scale fixed-bed biomass pellet boilers with preliminary results from a simplified approach. Energy Convers. Manag. 2012, 63, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, B.; Prajapati, Y.K.; Sheth, P.N. CFD analysis of the downdraft gasifier using species-transport and discrete phase model. Fuel 2022, 328, 125302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meenaroch, P.; Kerdsuwan, S.; Laohalidanond, K. Development of Kinetics Models in Each Zone of a 10kg/hr Downdraft Gasifier using Computational Fluid Dynamics. Energy Procedia 2015, 79, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngamsidhiphongsa, N.; Ponpesh, P.; Shotipruk, A.; Arpornwichanop, A. Analysis of the Imbert downdraft gasifier using a species-transport CFD model including tar-cracking reactions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 213, 112808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal, Z.; Rifau, A.; Quadir, G.; Seetharamu, K. Experimental investigation of a downdraft biomass gasifier. Biomass- Bioenergy 2002, 23, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidian, F.; Sampurno, R.D.; Ail, I. CFD SIMULATION OF SAWDUST GASIFICATION ON OPEN TOP THROATLESS DOWNDRAFT GASIFIER. J. Mech. Eng. Res. Dev. 2018, 41, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsi, C.-L.; Kuo, J.-T. Estimation of fuel burning rate and heating value with highly variable properties for optimum combustion control. Biomass- Bioenergy 2008, 32, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, B.; Chen, G.; Bowtell, L.; Mahmood, R.A. Assessment of densified fuel quality parameters: A case study for wheat straw pellet. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2023, 8, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahinpey, N.; Gomez, A. Review of gasification fundamentals and new findings: Reactors, feedstock, and kinetic studies. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2016, 148, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnecke, R. Gasification of biomass: comparison of fixed bed and fluidized bed gasifier. Biomass- Bioenergy 2000, 18, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siripaiboon, C.; Sarabhorn, P.; Areeprasert, C. Two-dimensional CFD simulation and pilot-scale experimental verification of a downdraft gasifier: effect of reactor aspect ratios on temperature and syngas composition during gasification. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2020, 7, 536–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, C.; Boissonnet, G.; Seiler, J.-M.; Gauthier, P.; Schweich, D. Study about the kinetic processes of biomass steam gasification. Fuel 2007, 86, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Santos, M.L.d. Solid Fuels Combustion and Gasification: Modeling, Simulation, and Equipment Operations Second Edition. 2010.

- Nørregaard, A.; Bach, C.; Krühne, U.; Borgbjerg, U.; Gernaey, K.V. Hypothesis-driven compartment model for stirred bioreactors utilizing computational fluid dynamics and multiple pH sensors. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 356, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abele, E.; Fujara, M. Simulation-based twist drill design and geometry optimization. CIRP Ann. 2010, 59, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSYS, I. , ANSYS fluent theory guide. 2015, Southpointe, 2600 ANSYS Drive, Canonsburg, PA 15317: ANSYS, Inc.

- Yang, Q.; Cheng, K.; Wang, Y.; Ahmad, M. Improvement of semi-resolved CFD-DEM model for seepage-induced fine-particle migration: Eliminate limitation on mesh refinement. Comput. Geotech. 2019, 110, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Jones, D.D.; Hanna, M.A. Thermochemical Biomass Gasification: A Review of the Current Status of the Technology. Energies 2009, 2, 556–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janajreh, I.; Al Shrah, M. Numerical and experimental investigation of downdraft gasification of wood chips. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 65, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, G. and D. Martelli, Validation of the coupled calculation between RELAP5 STH code and Ansys FLUENT CFD code. 2014.

- Wu, C.-C.; Völker, D.; Weisbrich, S.; Neitzel, F. The finite volume method in the context of the finite element method. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2022.

- ANSYS, I. , ANSYS fluent theory guide. 2018, Southpointe, 2600 ANSYS Drive, Canonsburg, PA 15317: ANSYS, Inc.

- Lu, D.; Yoshikawa, K.; Ismail, T.M.; El-Salam, M.A. Assessment of the carbonized woody briquette gasification in an updraft fixed bed gasifier using the Euler-Euler model. Appl. Energy 2018, 220, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launder, B. and D. Spalding, Lectures in mathematical models of turbulence. 1972: Academic Press, London, England.

- Keshtkar, M.; Eslami, M.; Jafarpur, K. A novel procedure for transient CFD modeling of basin solar stills: Coupling of species and energy equations. Desalination 2020, 481, 114350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnussen, B.; Hjertager, B. On mathematical modeling of turbulent combustion with special emphasis on soot formation and combustion. Symp. (International) Combust. 1977, 16, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, T.; Strom, H.; Lovas, T. Grid-independent Eulerian-Lagrangian approaches for simulations of solid fuel particle combustion. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 387, 123964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Chen, X.; Zhou, C.-S.; Xu, J.-S.; Musa, O. Numerical Study of Micron-Scale Aluminum Particle Combustion in an Afterburner Using Two-Way Coupling CFD-DEM Approach. Flow, Turbul. Combust. 2020, 105, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, G.; Zhong, W. CFD-DEM modeling of oxy-char combustion in a fluidized bed. Powder Technol. 2022, 407, 117698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, Y.-T.; Chyou, Y.-P.; Wang, T. Numerical analysis of gasification performance via finite-rate model in a cross-type two-stage gasifier. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2013, 57, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P. , Biomass Gasification, Pyrolysis and Torrefaction - Practical Design and Theory. 2018, Academic Press: United State of America.

- Gerun, L.; Paraschiv, M.; Vîjeu, R.; Bellettre, J.; Tazerout, M.; Gøbel, B.; Henriksen, U. Numerical investigation of the partial oxidation in a two-stage downdraft gasifier. Fuel 2008, 87, 1383–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Blasi, C.; Branca, C. Modeling a stratified downdraft wood gasifier with primary and secondary air entry. Fuel 2013, 104, 847–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Blasi, C. <Dynamic behaviour of stratified downdraft gasifiers.pdf>. Chemical engineering science, 2000. 55(15): p. 2931-2944.

- Muilenburg, M.; Shi, Y.; Ratner, A. Computational Modeling of the Combustion and Gasification Zones in a Downdraft Gasifier. in ASME 2011 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition. 2011.

- Erlich, C.; Fransson, T.H. Downdraft gasification of pellets made of wood, palm-oil residues respective bagasse: Experimental study. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.S.; Sohn, J.; Lee, U.D.; Hwang, J. CFD-DEM simulation of air-blown gasification of biomass in a bubbling fluidized bed gasifier: Effects of equivalence ratio and fluidization number. Energy 2020, 219, 119533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barco-Burgos, J.; Carles-Bruno, J.; Eicker, U.; Saldana-Robles, A.; Alcántar-Camarena, V. Hydrogen-rich syngas production from palm kernel shells (PKS) biomass on a downdraft allothermal gasifier using steam as a gasifying agent. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 245, 114592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya, D.M.Y.; Lora, E.E.S.; Andrade, R.V.; Ratner, A.; Angel, J.D.M. Biomass gasification using mixtures of air, saturated steam, and oxygen in a two-stage downdraft gasifier. Assessment using a CFD modeling approach. Renew. Energy 2021, 177, 1014–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, P.C.; Sekhar, S.J. Species – Transport CFD model for the gasification of rice husk (Oryza Sativa) using downdraft gasifier. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 139, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Paul, M.C.; Varjani, S.; Li, X.; Park, Y.-K.; You, S. Concentrated solar thermochemical gasification of biomass: Principles, applications, and development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 150, 111484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xu, H.; Yang, W.; Zhou, A.; Xu, M. CFD simulation of a fluidized bed reactor for biomass chemical looping gasification with continuous feedstock. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 201, 112143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.D.; Shah, N. ; Patel CFD Analysis of Spatial Distribution of Various Parameters in Downdraft Gasifier. Procedia Eng. 2013, 51, 764–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, E.; Ismail, T.M.; Ramos, A.; El-Salam, M.A.; Brito, P.; Rouboa, A. Assessment of the miscanthus gasification in a semi-industrial gasifier using a CFD model. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 123, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Jensen, A.; Glarborg, P.; Jensen, P.; Kavaliauskas, A. Numerical modeling of straw combustion in a fixed bed. Fuel 2005, 84, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, P.N.; Babu, B. Experimental studies on producer gas generation from wood waste in a downdraft biomass gasifier. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 3127–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couto, N.; Monteiro, E.; Silva, V.; Rouboa, A. Hydrogen-rich gas from gasification of Portuguese municipal solid wastes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 10619–10630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gungor, A.; Yildirim, U. Two dimensional numerical computation of a circulating fluidized bed biomass gasifier. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2013, 48, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T.; Maya, D.M.Y.; Nascimento, F.R.M.; Shi, Y.; Ratner, A.; Lora, E.E.S.; Neto, L.J.M.; Palacios, J.C.E.; Andrade, R.V. An Experimental and Theoretical Study of the Gasification of Miscanthus Briquettes in a Double-Stage Downdraft Gasifier: Syngas, Tar, and Biochar Characterization. Energies 2018, 11, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brar, J.S.; Singh, K.; Zondlo, J.; Wang, J. Co-gasification of Coal and Hardwood Pellets: Syngas Composition, Carbon Efficiency and Energy Efficiency. 2012 Dallas, Texas, July 29 - August 1, 2012. 2012. American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers.

- Pandey, A.; Bhaskar, T.; Stöcker, M.; Sukumaran, R.K. Recent Advances in Thermo-Chemical Conversion of Biomass; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, NX, Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, U.; Paul, M.C. CFD modelling of biomass gasification with a volatile break-up approach. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 195, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulos, I.-S.; Karagiannidis, A.; Gkouletsos, A.; Perkoulidis, G. Modelling of a downdraft gasifier fed by agricultural residues. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, P.; Dubuisson, R. Performance analysis of a biomass gasifier. Energy Convers. Manag. 2002, 43, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pellet features | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Proximate analysis (wt % as received, db) |

Moisture | 3.50 |

| Volatile matters | 44.51 | |

| Fixed carbon | 36.99 | |

| Ash | 15.00 | |

| Calorific value, HHV (MJ/kg) | 19.06 | |

| Ultimate analysis (wt % as received, db) |

Carbon | 45.97 |

| Hydrogen | 5.22 | |

| Nitrogen | 0.72 | |

| Sulphur | 0.21 | |

| Oxygen (by difference) | 47.88 | |

| Density | Apparent density (kg/m3) | 817.71 |

| Bulk density (kg/m3) | 427.45 | |

| Thermokinetic properties* | In combustion | |

| Activation of energy, (kJ/mol) | 418.935 | |

| Pre-exponential factor, (1/sec) | 1.76E+16 | |

| In pyrolysis | ||

| Activation of energy, (kJ/mol) | 132.868 | |

| Pre-exponential factor, (1/sec) | 2.4E+4 | |

| Components | Computational model |

|---|---|

| Biomass |

|

| Air |

|

| Gasification |

|

| Parameter | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Gasification agent (air) | Air flow rate: 54 kg/hr (37.87 Nm3/hr) | - |

| Air velocity: 3.2 ~7.2 m/s (average 5.2) | [1] | |

| Air fuel ratio: 6:1 v/m | [38] | |

| Air inlet temperature: 300K | [1] | |

| Pressure | Gasification pressure: 1 atm = 101325 pascal | [6] |

| Outlet gauge pressure: 0 | [30] | |

| Pressure outlet: 249 pascals (min) and 747 pascals (max) | - | |

| Biomass | Input: Biomass (WSP) inject (Gravity feed) | - |

| Gravitational acceleration: - 9.8 m/sec2 | - | |

| Biomass inlet temperature: 300°K | [2] | |

| Biomass flow rate: 9 kg/hr | [1] | |

| Biomass moisture content: 3.5% | - | |

| Temperature | Temperature-Atmospheric condition: 300K | [30] |

| Operating temperature: 300 ~ 2500K | - | |

| Reactor wall | Motion: stationary | [30] |

| Wall shear condition: No slip | ||

| Wall roughness: standard | ||

| Inlet species mass fraction of O2: 0.23 | [30] | |

| Inlet velocity magnitude: 0.056 m/sec | - | |

| Wall (interior and exterior walls): Stainless steel | - | |

| Wall thickness: 3 mm | - | |

| Others | Equivalence ratio: 0.2 ~ 0.6 | [24] |

| Turbulence intensity: 5% | [30] | |

| Particle-specific heat: 2.5 kJ/kgK | [30] | |

| Particle size in the discrete phase: 0.1 mm | [2] | |

| Uniform porosity: 0.5 | [54] | |

| For simulation time setup: 10 sec | [30] | |

| Model run: 0 to 7200 sec | ||

|

Conditions/Assumptions |

|

|

|

P1: Radiation reflection at the surface is isotropic |

|

-intermittency: Include the effect of share stress transport, kinetic and its dissipation rate and the change in velocity |

|

Nonpremix combustion-non-adiabatic |

|

Euler-Lagrange (discrete phase)Particle devolatilisation model: Single kinetic rate Particle combustion: Kinetic/diffusion-limited rate |

| Variable | Discretisation Scheme | Information |

|---|---|---|

| Pressure staggering option | PRESTO! | Pressure-based Navier-Stokes solution algorithm (the default) |

| Pressure velocity coupling | SIMPLE | Governing equation |

| Gradient option | Least Squares Cell-based | - |

| Pressure | Second Order Upwind | Spatial discretisation |

| Momentum | Second Order Upwind | Spatial discretisation |

| Turbulent Kinetic Energy | Second Order Upwind | Spatial discretisation |

| Turbulent Dissipation Rate | Second Order Upwind | Spatial discretisation |

| Energy | Second Order Upwind | Spatial discretisation |

| Mean mixture fraction | First Order Upwind | Spatial discretisation |

| Mixture fraction variance | Second Order Upwind | Spatial discretisation |

| Soot | Second Order Upwind | Spatial discretisation |

| Others | First order Upwind | - |

| Discrete ordinates | Second Order Upwind | Spatial discretisation |

| Formulation | Implicit | - |

| Velocity formulation | Absolute | default setting |

| Porous formulation | Superficial velocity | - |

| Initialisation | Hybrid | - |

| Gas phase reaction | Solid particle surface reactions | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction | Reaction order | Reaction | Reaction order |

| Volatile decomposition | Char decomposition | ||

| CO Combustion: | |||

| H2 Combustion: O | |||

| Water-gas shift: | |||

| Particulers | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Mesh element size (average) | : | 1 mm |

| No of nodes | : | 172677 |

| No of elements | : | 171558 with a rectangular shape |

| Minimum orthogonal quality | : | 0.38916 |

| Maximum aspect ratio | : | 5.27929. |

| Particulars | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Experiments | ||

| Temperature (k) | Combustion (Upper concentric at x = 0.25 to 0.3 m) |

900~1413 | 1250 |

| Reduction (Bottom reduction at x = 0.425 m) |

1100 | 1080 | |

| Gas species (% v/v) |

CO2 | 9.99 | 9.4 |

| CO | 21.60 | 23.3 | |

| CH4 | 0.13 | 0.051 | |

| H2 | 16.81 | N/A | |

| Zone | Temperature range, k |

|---|---|

| Drying and pyrolysis | 300~856 |

| Combustion | 856~1356 (Max temp. 2160) |

| Reduction | 1356~974 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).