INTRODUCTION

Transcutaneous stimulation serves as a viable intervention to restore upper limb functions [

1]. Thus, evaluating the neurophysiological function mediated by transcutaneous stimulation will aid in developing better devices, their optimization, and the assessment of the meditated recovery. This study presents a system to evaluate several facets of hand function for neuroprostheses-mediated tasks.

The forearm's tightly packed musculature makes the identification of optimal motor point and electrode configuration an arduous task [

2,

3]. Furthermore, more than one stimulation site and electrode configuration can elicit a similar response. Hence, targeting the forearm muscles to identify, localize, and characterize the motor points and their electrode configurations must be carried out like a methodical process, wherein the assessment setup must facilitate fasting scanning times and standardization of outcome [

2,

3,

4].

During external stimulation, its influence and the resulting muscle contraction can be quantified based on the contact forces exerted using a dynamometer under isometric conditions [

5,

6]. Similarly, studies have used dynamometry to measure wrist torque and prehensile grasp forces [

7,

8]. Although they are suitable for larger forces such as wrist torque or isometric digit forces, they are not suitable for low-level grip forces that involve object manipulation tasks.

Similarly, quantitative investigations on hand function can be summed up into four categories. Firstly, finger movements and grip force are studied to evaluate fine motor control [

8,

9]. Secondly, the relation between grip force and the load is studied by assessing the grip necessary to counteract the physical load while holding an object [

10,

11]. Thirdly, to study unconstrained manipulation, dynamic gripping is assessed. Lastly, the force-generating capacity is assessed by studying the power grip [

12]. To facilitate such measures while performing manipulation tasks, both kinetic and kinematic aspects of digits and the objects being grasped must be evaluated [

10].

Studies have measured the position and forces of digits and fingers using a measurement system that mounted load cells [

7,

13]. However, these systems were static, facilitating assessments only for prefixed hand or forearm orientations. As an alternative to such static assessment systems, sensorized gloves can promote robust and dynamic measures while performing manipulation tasks. Sophisticated systems included the use of fiber optics-based sensors, motion capture devices, such as the Vicon [

8,

9,

10], and inertial measurement sensors, which gave the position and orientation of each digit in a 3D space used [

10,

11,

14,

15,

16]. Still, these devices are cumbersome, need constant calibration, and are technically challenging to operate in a non-laboratory-based setting. However, incorporating lightweight, compact sensors with robust measurement outcomes and low power consumption can make them ideal for hand function assessments.

With the above motivations, the main objective of this study is to present a system for assessing several aspects of electrical stimulation while facilitating hand function tasks. Thus, the objective of this system includes:

To feature an XY-gantry system that localizes motor points under three forearm orientations.

To include dynamometry and electromyography to assess muscle contraction.

To facilitate the assessment of nerve excitation by eliciting a twitch response.

To include a sensorized glove for kinetic and kinematic measures of hand function.

METHODS

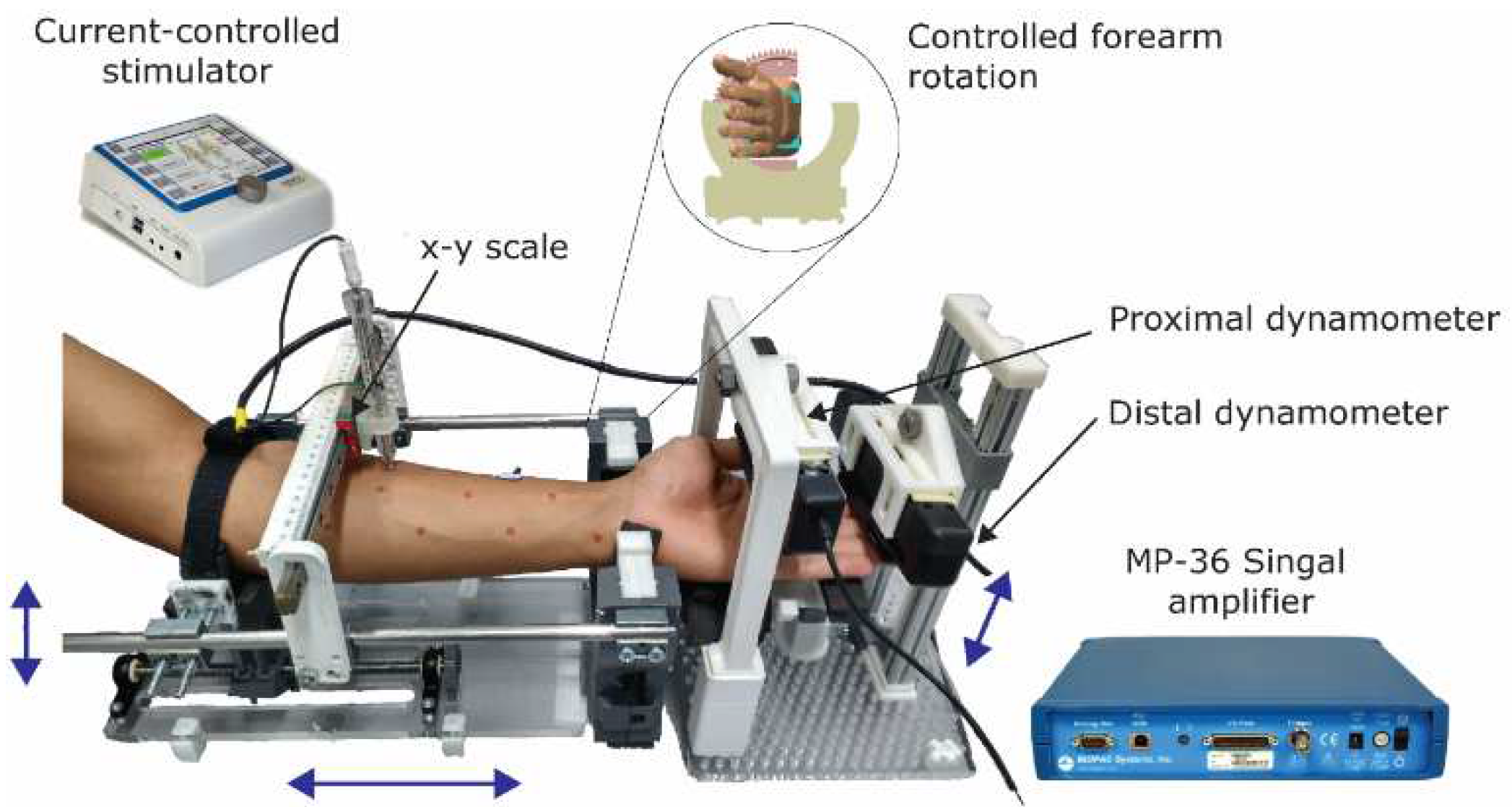

Firstly, a custom-made setup was devised to position/orient the forearm while the participants sat comfortably (Figure 1). Given the prolonged nature of experiments, adjustable and padded arm support further improved participant's comfort. The anthropometric information on the length of the forearm, length span of the wrist, and length of fingers was considered for the design of the test bench [

17,

18]. The setup also featured several adjustments that could improve the suitability of the user, as indicated by blue arrows in Figure 1. At the wrist level, a mechanism facilitates controlled pronated, supinated, and neutral positions, insert in Figure 1. The setup featured an XY-gantry that gave electrode positions about the forearm surface.

Figure 1.

Hand function assessment system.

Figure 1.

Hand function assessment system.

Secondly, the setup had two SS25LA Dynamometers (BIOPAC Systems, Inc., California) that evaluated the muscle response to subsequent stimulation. One dynamometer measured the forces exerted by the thumb and wrist and the other measured forces across the four digits. The positions of these sensors were adjusted to suit the user. Force measurements from these dynamometers sampled at 1 kHz were recorded using Biopac MP 36 (BIOPAC Systems, Inc., California). The Biopac MP 36 amplifier also enabled electromyography (EMG) measures. The interactive objects represented the objects that were used in daily living [

19,

20].

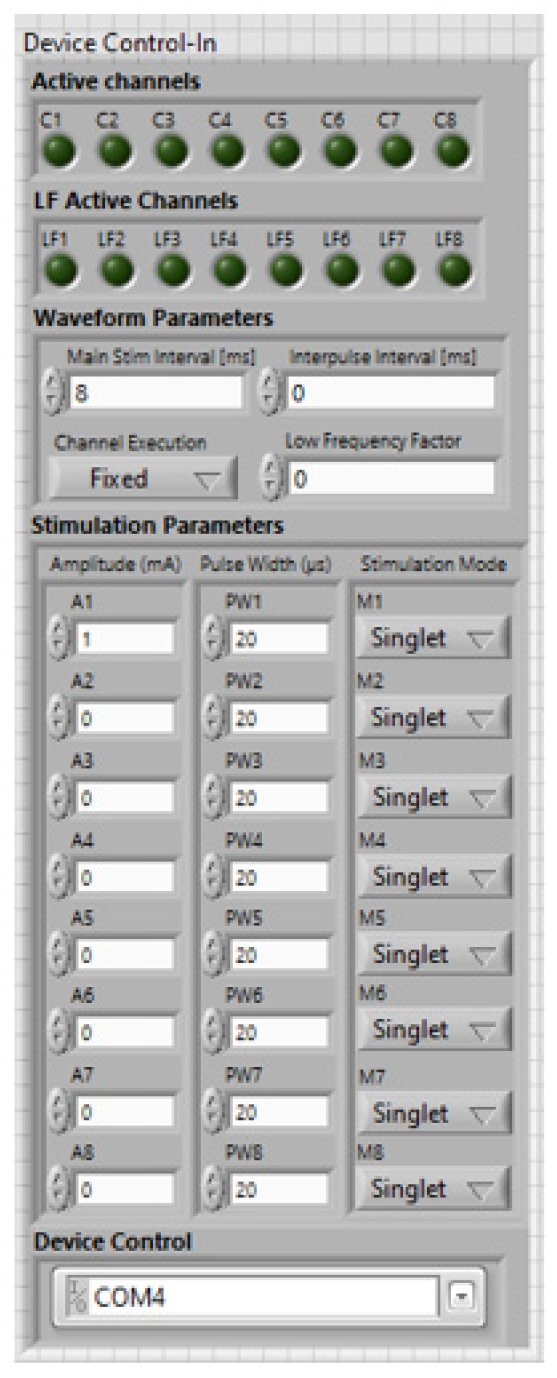

Also, the external stimulation was delivered through a current-controlled stimulator, Rehastim

TM (Hasomed GmbH). The stimulator had eight channels to deliver customized stimulation and supported various pulse generation modes. The stimulation parameters could be regulated, with amplitude up to 130 mA, pulse-width up to 500 µs, and frequency up to 50 Hz, using a PC via the ScienceMode2. A custom software interface was developed to control the hardware (Figure 1). Details of this software implementation are described here [

21].

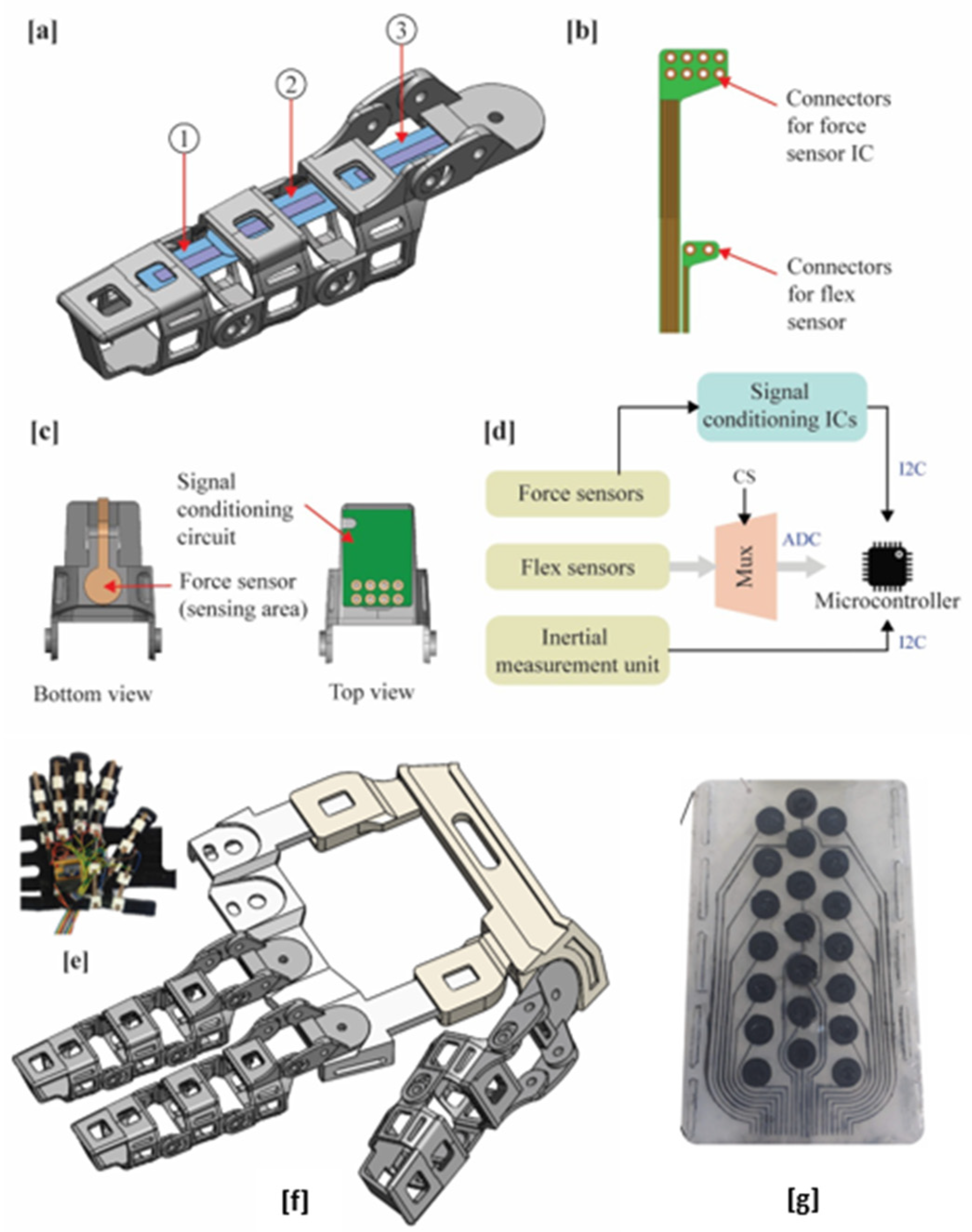

Thirdly, a sensorized glove facilitated the kinetic and kinematic measures of hand manipulation tasks. It consisted of a fabric glove with several sensors mounted using a 3D printed assembly (

Figure 2e). The glove mounted flex sensors, force sensors, and IMUs that measured digit motion, fingertip forces, and hand orientation during activities of daily living (ADL)-based grasp, respectively.

A second iteration of the glove was also developed, as described here [

22]. The glove included unidirectional, resistance-based flex sensors (Spectra-Symbol, Salt Lake City, USA). Several flex sensors measured the flexion of five digits, the flexion of the wrist, the abduction of the thumb, and the extension of the wrist. Each digit had two flex sensors that measured the range of motion at its respective proximal and medial phalanges. The outputs were then normalized based on the ROM of their respective phalanges to give the percentage of flexion/extension between 0 – 100. The capacitance-based force sensors (Singletact

TM, Pressure Profile Systems Inc., USA) at the fingertips gave a pre-calibrated output that measured fingertip forces up to 50 N. Also, the IMU was mounted on the posterior side of the hand, which prevented any interruption to the user while handling or grasping objects. A DAQ device collected the outputs from all the sensors and processed them in LabVIEW 8.6 (National Instruments, TX, USA).

The ADL-based grasps were mediated by dynamic control over the forearm muscles using an electrode array-based sleeve. The sleeve had several reconfigurable 3 x 3 pads of Ag-AgCl-based disposable snap electrodes that covered the desired forearm regions. Seen-printed wearable sleeves were also used [

23] (

Figure 2g).

RESULTS And DISCUSSION

The assessment setup enabled to position/orient the forearm; this allowed motor point identification under controlled pronated, supinated, and neutral positions in [

24,

25]. Following motor point-based stimulation, to quantify muscle tension directly, isometric contact forces of the digits and the wrist were measured using the two dynamometers mounted to the setup. Moreover, motor points along the forearm surface were traced using a special motor point pen mounted on the XY gantry. The gantry system within the setup facilitated the localizing and assessment of the response of motor point-based stimulation.

Similarly, dynamometry was used to determine the muscle response to varying stimulation parameters [

26]. Evoked force exertions were normalized based on the strength of isometric contractions using maximum voluntary isometric contractions (MVIC) [

25]. Also, the influence of stimulation-induced fatigue was studied across the forearm muscle groups; here, EMG was used to quantify the onset of fatigue by measuring the fall in muscle contraction levels over time [

26]. Furthermore, the sensorized glove, which mounted flex and force sensors, measured digit motion and force exerted during ADL-based grasps [

22]. These electrophysiological evaluations can help identify stimulation waveform parameters for a desired target response and further optimizations on them can improve subject-specific outcome [

27,

28,

29,

30].

Lastly, the setup was able to position the forearm comfortably for extended periods, which enabled psychophysical, recruitment (muscle), and excitability measures to assess the stimulation performance for electrodes [

23,

31,

32,

33].

CONCLUSION

A hand grasp assessment setup is proposed to evaluate several aspects of electrical stimulation across the forearm muscles. The entire system and its elements were custom-built, which consisted of a test-bench platform with dynamometry and electromyography, a sensorized glove, and interactive objects. The test-bench platform featured an XY-gantry scale that was used to locate and assess the response motor point-based stimulation. Also, the sensorized glove-mounted flex sensors, force sensors, and IMUs that measured digit motion, fingertip forces, and hand orientation during ADL-based grasps, respectively. The system was exclusively designed for neuroprostheses-mediated grasp. Still, it can be extended to generic grasp and object manipulation-based research.

References

- Marquez-Chin, C.; Popovic, M.R. Functional electrical stimulation therapy for restoration of motor function after spinal cord injury and stroke: A review. Biomed Eng Online 2020, 19, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, R.H. FNS of the upper limb: targeting the forearm muscles for surface stimulation. Med Biol Eng Comput 1990, 28, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerveld, A.J.; Schouten, A.C.; Veltink, P.H.; van der Kooij, H. Selectivity and Resolution of Surface Electrical Stimulation for Grasp and Release. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2012, 20, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RaviChandran, N.; Aw, K.C.; McDaid, A. Characterizing the Motor Points of Forearm Muscles for Dexterous Neuroprostheses. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2020, 67, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, C.M.; Dixon, W.; Bickel, C.S. Impact of varying pulse frequency and duration on muscle torque production and fatigue. Muscle Nerve 2007, 35, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickel, C.S.; Gregory, C.M.; Azuero, A. Matching initial torque with different stimulation parameters influences skeletal muscle fatigue. J Rehabil Res Dev 2012, 49, 323–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, M.; Gross, G.P.; Lang, M.; Kuhn, A.; Keller, T.; Morari, M. Assessment of finger forces and wrist torques for functional grasp using new multichannel textile neuroprostheses. Artif Organs 2008, 32, 634–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, T.; Popovic, M.R.; Dumont, C. A dynamic grasping assessment system for measuring finger forces during wrist motion. Artif Organs 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, T.; Popovic, M.R.; Ammann, M.; Andereggen, C.; Dumont, C. a System for Measuring Finger Forces During Grasping. In Proceedings of the International Functional Electrical Stimulation Society (IFESS 2000) Conference, Aalborg, Denmark; 2000, pp. 2–5.

- Reilmann, R.; Gordon, A.M.; Henningsen, H. Initiation and development of fingertip forces during whole-hand grasping. Exp Brain Res 2001, 140, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurillo, G.; Zupan, A.; Bajd, T. Force tracking system for the assessment of grip force control in patients with neuromuscular diseases. Clinical Biomechanics 2004, 19, 1014–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chida. S.; et al. Evaluation Of Grasping Power By Means Of Functional Electrical Stimulation In A Patient With Complete C6 Tetraplegia. In Proceedings of the 3rd Annual Conference of the International Functional Electrical Stimulation Society; 1998; p. 181.

- Westerveld, A.J.; Schouten, A.C.; Veltink, P.H.; Van Der Kooij, H. Control of thumb force using surface functional electrical stimulation and muscle load sharing. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2013, 10, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crago, P.E.; Chizeck, H.J.; Neuman, M.R.; Hambrecht, F.T. Sensors for Use with Functional Neuromuscular Stimulation. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 1986, BME-33, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memberg, W.D.; Crago, P.E. A Grasp Force and Position Sensor for the Quantitative Evaluation of Neuroprosthetic Hand Grasp Systems. IEEE Transactions on Rehabilitation Engineering 1995, 3, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentner, R.; Classen, J. Development and evaluation of a low-cost sensor glove for assessment of human finger movements in neurophysiological settings. J Neurosci Methods 2009, 178, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett, J.W. The Adult Human Hand: Some Anthropometric and Biomechanical Considerations. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 1971, 13, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simone, L.K.; Kamper, D.G. Design considerations for a wearable monitor to measure finger posture. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2005, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergara, M.; Sancho-Bru, J.L.; Gracia-Ibáñez, V.; Pérez-González, A. An introductory study of common grasps used by adults during performance of activities of daily living. Journal of Hand Therapy 2014, 27, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starkey, M.L.; Curt, A. Clinical Assessment and Rehabilitation of the Upper Limb Following Cervical Spinal Cord Injury. In Neurorehabilitation Technology, no. 1; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 107–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RaviChandran, N.; Aw, K.; McDaid, A. A LabVIEW Interface for RehaStim 2. TechRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, N.; McDaid, A. Design of a low-profile glove to evaluate neuroprostheses-mediated grasps. International Journal of Biomechatronics and Biomedical Robotics 2022, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, N.; Teo, M.Y.; Mcdaid, A.; Aw, K. Conformable Electrode Arrays for Wearable Neuroprostheses. Sensors 2023, 23, 2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RaviChandran, N.; Aw, K.; McDaid, A. Electrophysiologically-identified motor points of forearm muscles. IEEE Dataport 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RaviChandran, N.; Aw, K.C.; McDaid, A. Characterizing the Motor Points of Forearm Muscles for Dexterous Neuroprostheses. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2020, 67, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RaviChandran, N. Towards Wearable Neuroprostheses for Hand Function Restoration. The University of Auckland, 2019. Accessed: Aug. 19, 2023. [Online]. Available online: https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/50470.

- RaviChandran, N.; Aw, K.; McDaid, A. Automatic calibration of electrode arrays for dexterous neuroprostheses: a review. Biomed Phys Eng Express 2023, 9, 052001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisi, L.; Ravichandran, N. Genetic algorithms and unsupervised machine learning for predicting robotic manipulation failures for force-sensitive tasks. Proceedings - 2018 4th International Conference on Control, Automation and Robotics, ICCAR 2018; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2018; pp. 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, L.; RaviChandran, N. Evolutionary Denoising-Based Machine Learning for Detecting Knee Disorders. Neural Process Lett 2020, 52, 2565–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, L.; RaviChandran, N.; Lanzillotta, M. Artificial Intelligence for Clinical Gait Diagnostics of Knee Osteoarthritis: An Evidence - based Review and Analysis. TechRxiv. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, N.; Teo, M.Y.; Aw, K.; McDaid, A. Design of Transcutaneous Stimulation Electrodes for Wearable Neuroprostheses. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2020, 28, 1651–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RaviChandran, N.; Aw, K.C.; McDaid, A. Influence of Electrode Geometry on Selectivity and Comfort for Functional Electrical Stimulation. In The International Functional Electrical Stimulation Society (IFESS), RehabWeek; IFESS: Toronto, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RaviChandran, N.; Hope, J.; Aw, K.; McDaid, A. Modeling the excitation of nerve axons under transcutaneous stimulation. Comput Biol Med 2023, 107463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

N. RaviChandran* and A. McDaid are with the Medical Devices and Technologies group, Department of Mechanical Engineering, The University of Auckland, 20 Symonds street, Grafton, Auckland, New Zealand.

K. Aw is with the Smart Materials and Microtechnologies group, Department of Mechanical Engineering, The University of Auckland,

20 Symonds street, Grafton, Auckland, New Zealand.

(Correspondence email: nrav195@aucklanduni.ac.nz)

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).