Keyword: electrophysiology

1. Introduction

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) reduces morbidity and mortality and reverses left ventricular (LV) remodeling in heart failure patients with LV electrical dyssynchrony and systolic impairment [

1,

2]. CRT alone demonstrated to decrease sudden death according to the remodeling properties on left ventricle and to the reduction of ventricular arrhythmias [

3].

Despite this, CRT induced proarrhythmia has been reported as a clinically serious, rare, and unpredictable phenomenon [

4,

5]. The mechanism of CRT-induced proarrhythmia remains under debate. The main reliable hypothesis seems to be that prolongation of the transmural dispersion of repolarization, by reversal of the activation sequence caused by LV epicardial pacing, might promote polymorphic TV [

5,

6] while others have indicated re-entry as the possible responsible mechanism of likely mechanism induced proarrhythmia [

7]. Furthermore, the electrical storm induced by CRT-pacing might be observed early after the implantation (3 days) [

8] but a longer latent period (2 years) has been also described [

9]. Independently to the delay of presentation, CRT-induced proarryhtmia is uncommon but life-threatening event after CRT implantation causing electrical storm and worsening of hemodynamic conditions. The early presentation of proarrhythmia seemed to be clearly related to CRT pacing, while a longer delayed electrical storm might be easily attributed to the progression of cardiomyopathy and worsening of heart failure condition.

In this case report, a description of how a LV pacing induced polymorphic ventricular tachycardia immediately after the initiation of CRT has been reported.

2. Case Presentation

The patient is a 77year old man with systolic heart failure, depressed left ventricular function (30%), functional class NYHA III. In his clinical history , a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease emerged as well as a persistent atrial fibrillation (AF) treated with cardioversion in 2019 and a multivessel coronary artery disease treated with coronary angioplasty (PTCA) on MO and LAD.

On 2019, after recurrent fast ventricular tachycardia (TV) episodes, the patient has been implanted with an ICD in secondary prevention. He underwent placement of Abbott Fortify Assura 1359QC with a right defibrillation lead Durata 7122Q.

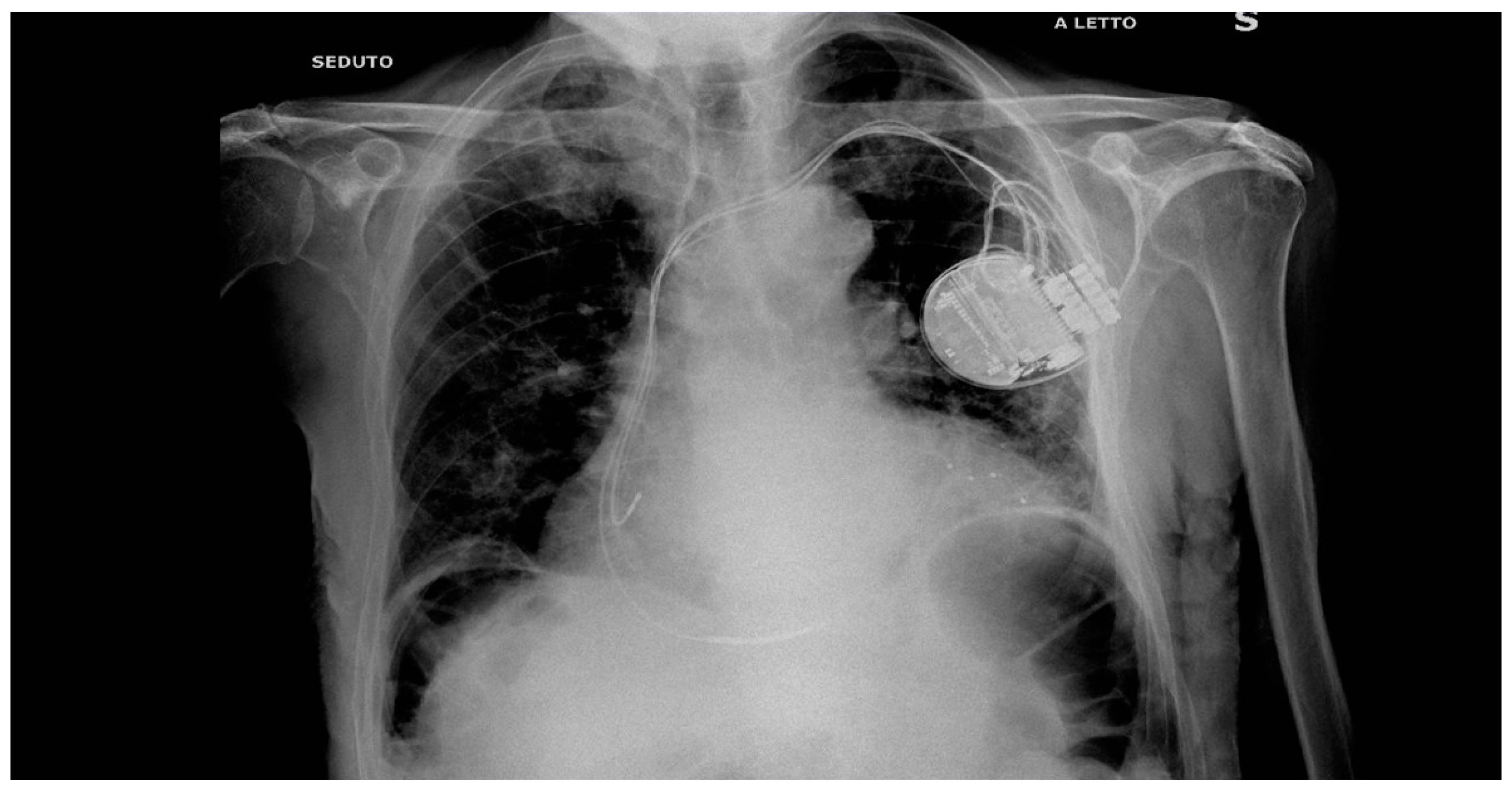

In 2022 after history of HF, hypocinetic cardiomyopathy with AF - not controlled frequency, an upgrade to CRTD implantation was programmed followed by the NAV ablation in order to reduce the elevated frequency of AF despite medical optimization (see

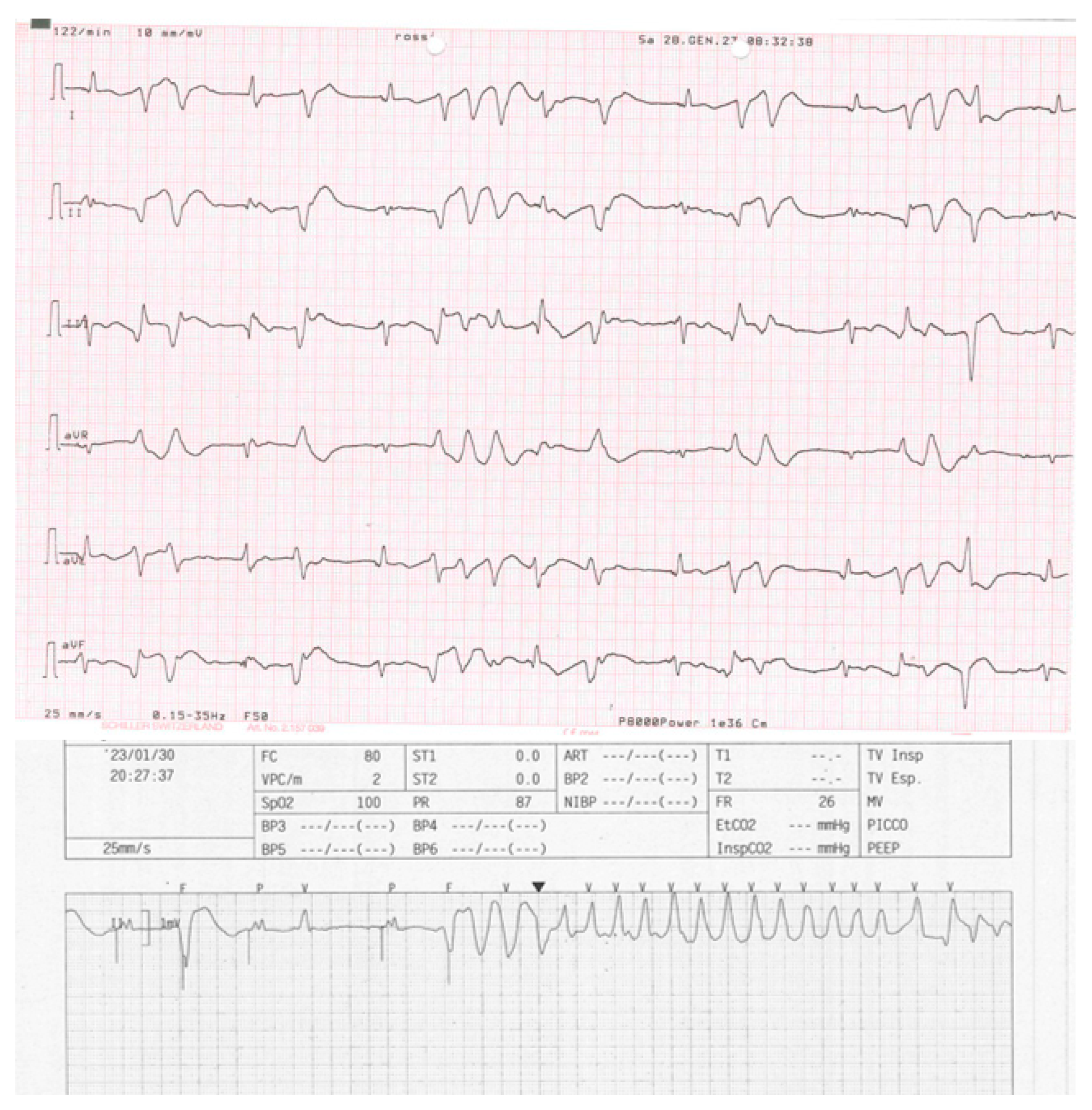

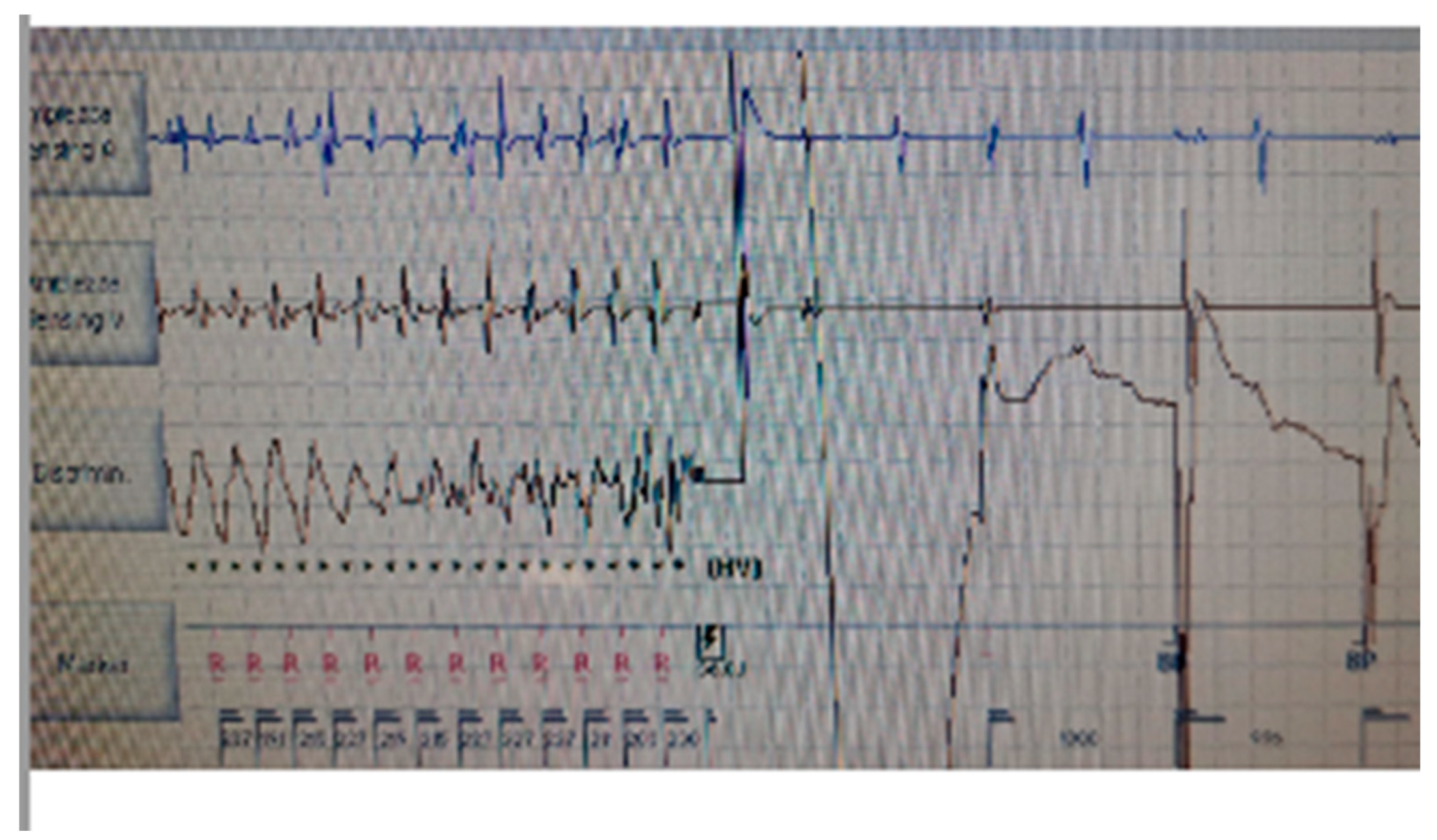

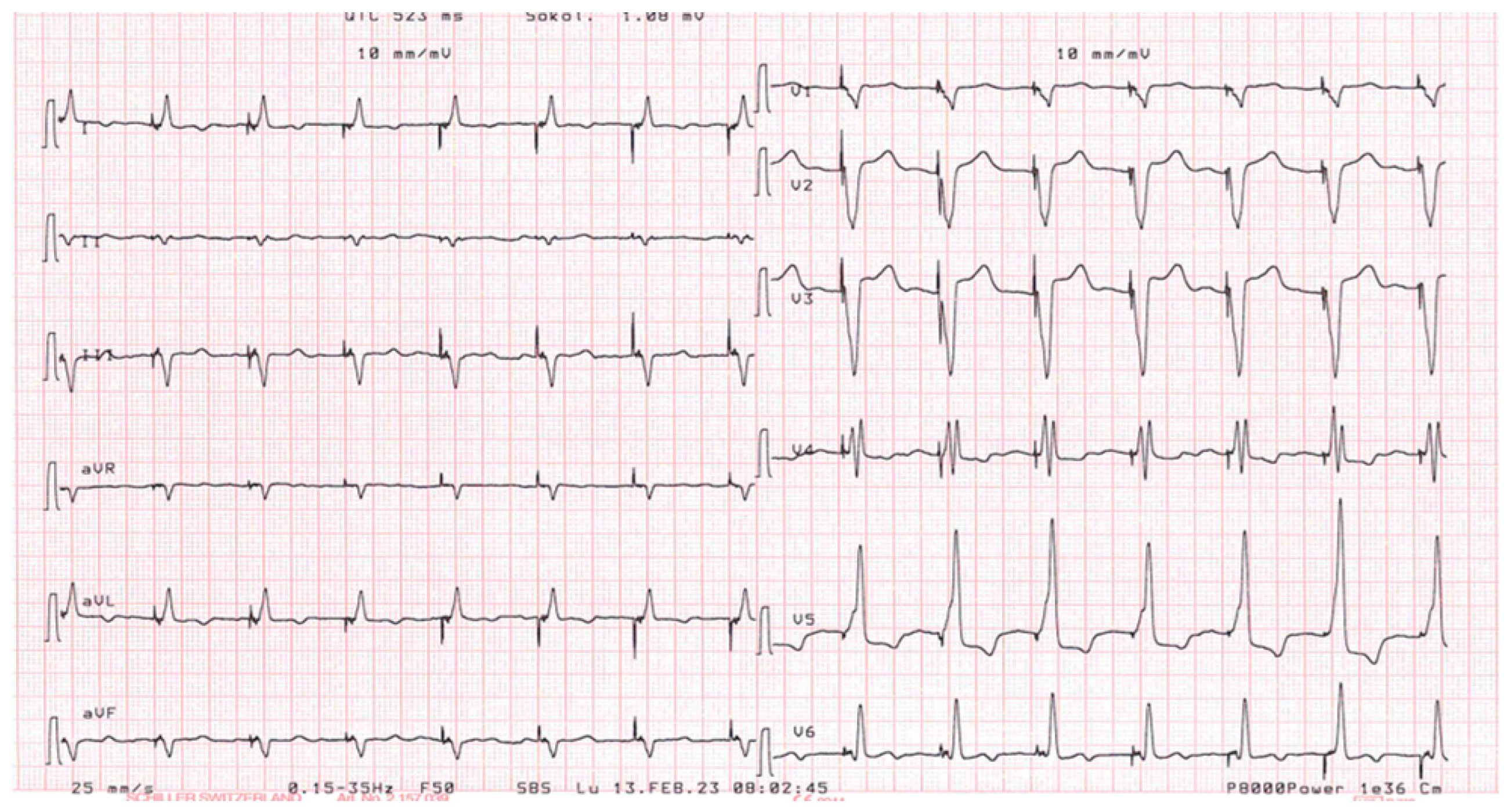

Figure 1 for the correct position of electrocatheters after implantation). During the night, caused by an initial delirium , it has been initiated quetiapine and haloperidol in order to control the psychotic poussee. The day after the CRTD implantation, polymorphic ventricular tachycardia have been registered, initially treated with magnesium intravenously and an increment of bisoprolol dosage (see

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). According to the hypothesis of a proarrhythmic damage due to the new LV stimulation, a check of the device has been performed but the mechanism of CRT-induced proarrhythmia remains unknown during the LV stimulation (single site, D1-M1 configuration).

Although different poles have been tested, the LV stimulation was turned off. According with the clinical data available in the literature which tested the hypothesis that pacing with a left ventricle lead positioned on the epicardial scar can be a responsible mechanism and we tried to program the Multipoint Pacing Stimulation (MPP) from the left side, thus modifying the generated wavefront and the refractory period. With the new wavefront generated with the Multipoint Stimulation, ventricular tachycardia / electrical storm no longer occurred. The patient stopped the neurolectic drugs and a low dosage of amiodarone (600mg/week ) and bisoprolol have been started before the hospital discharge. During a long-term follow-up (12 months) no other TV episodes have been stored in the memory of the device.

3. Discussion

Potential pro-arrhythmic effects of CRT has been described in several previous experiences [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9] where biventricular and LV pacing are responsible of polymorphic and monomorphic VT although the mechanism of CRT-induced TV remains unclear. It has been observed as VT induced by CRT regarded patients with ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Several authors [

6] believed that changing the activation sequence near the scar areas by the LV stimulation is responsible of the unidirectional block and reentry and might induce proarrhythmia .

Others [

8] have demonstrated that VT can be induced by stimulating on epicardial scar and managed with catheter ablation, identifying the intramyocardial reentry as the main mechanism.

Almost surely LV pacing near the scar seems to be the primarily responsible of VT inducted.

In our patient, according with the LV lead position related to the scar observed in the previous CAD episodes, seems to be very close to the first configuration tested in CRT stimulation (D1-M2).

It should be postulate that the presence in therapy of haloperidol and quetiapine might be play a role in the determinism of proarrhythmmic effect. Previous reports [

10,

11,

12] underlined as particularly for haloperidol , the risk of torsades de pointes seemed to be demonstrated especially for women and for intravenously administration. Less dangerous and proved was the effect on QT length for quetiapine, that seemed to determinate a QT shortening that might be also considered an indicator of proarrhythmic effect. In any case, the antipsychotic treatment has been withdrawn quickly after the polymorphic TV evidence and none drug has been infused intravenously. The quinidine-like effects of some antidepressant drugs (particularly tricyclic antidepressants) and antipsychotic drugs (particularly the phenothiazines) has normally provided as treatment of psychosis and depression in patients with major mental illness. This is especially true among elderly patients with pre-existing risk factors for corrected QT interval prolongation. Specifically, clinicians treating elderly patients with antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs that may prolong the QTc interval should surely obtain a baseline ECG for elderly female patients with additional risk factors such as personal or family history of pre-syncope or syncope, electrolyte disturbances or cardiovascular disease. Elderly male patients are also subject to QTc interval prolongation when such risk factors are present.

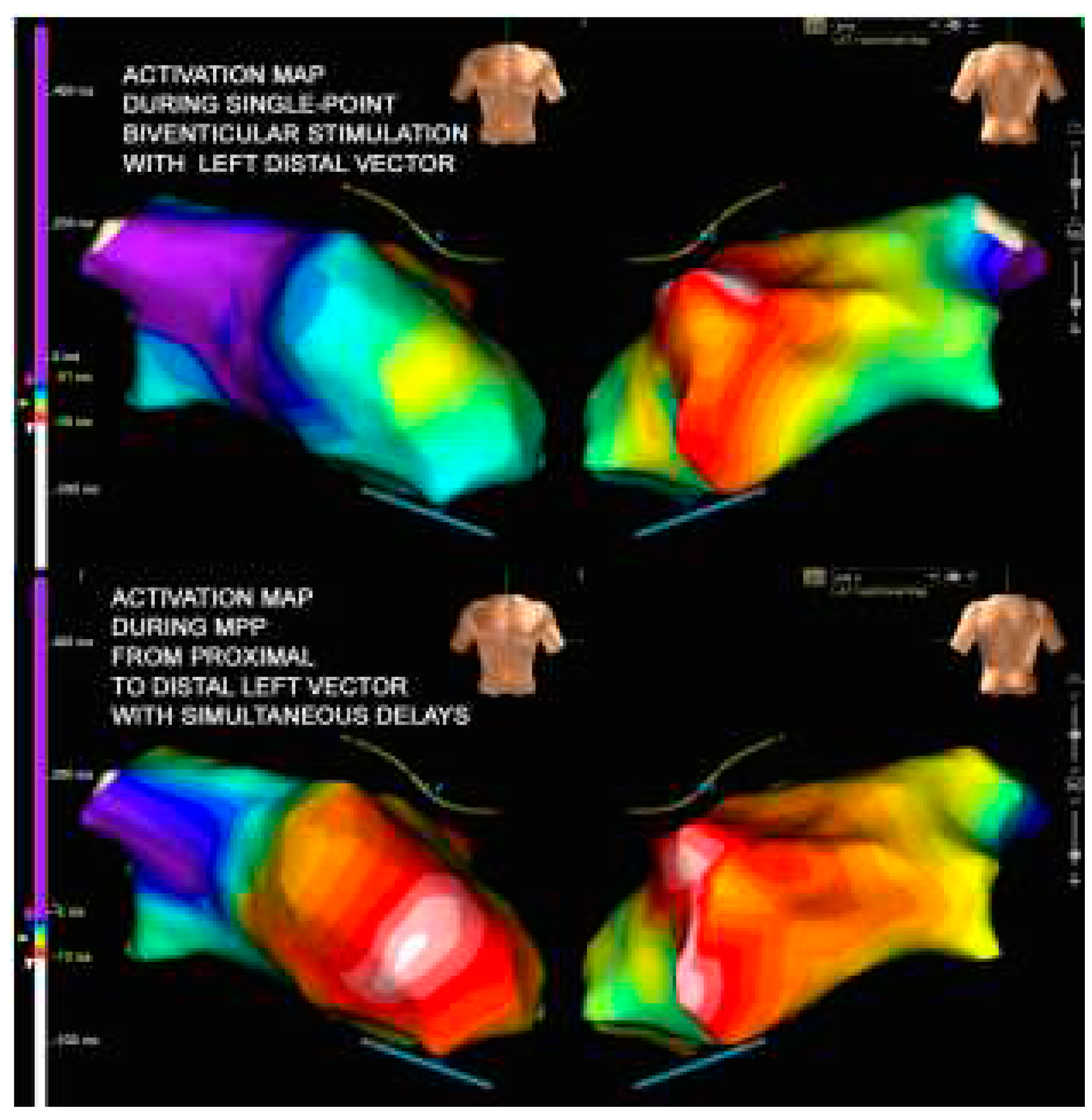

Since the patient had a fairly wide scar which also affected the proximal part of the catheter (M3-P4), we can assume that the change of the pole was not sufficient to avoid the unidirectional block and initiation of the reentrant circuit. Our possible solution then it was to try an extended and wider wavefront stimulation created by the multipoint left ventricular pacing (MPP). The MPP is obtained when multiple pacing stimuli are delivered via a single quadripolar lead placed in a branch of the coronary sinus to achieve a biventricular pacing [

13]. Recent clinical single-centre experiences [

13,

14] suggested as the MPP stimulation seemed to improve acutely the measures of dyssynchrony, the hemodynamic response obtained through a recruitment of a larger portion of the left ventricle, resulting in a more homogenous and flat propagation (see

Figure 4). Asvestas et al [

9] described as the MPP stimulation was able to suppress a proarrhythmic effect in a CRTD patients two years after the implantation of the device programming a larger front of stimulation (bipolar pacing proximal 4 to RV coil). In the experience of Roque et al [

8], 8 patients with proarrhythmic effect of CTRD in which a positive LV lead/scar relationship (in other words defined as a lead tip positioned on scar/border zone) were successfully treated by catheter ablation of the ventricular tachycardia.

In our patients we decided to reactivate LV pacing using 2 differently poles of the LV lead that have been activated simultaneously (D1-M2 – M3-P4). After this change the patient was monitored and no VTs has been recorded and treated (

Figure 5). In our point of view the wider wave front generated by the MPP near the scar area can activated a larger part of the left ventricle determining a synchronization of the tissue. We can assume in our experience that VTs induced are related to the reentry mechanism facilitated by the unidirectional block. As a result, MPP pacing configuration near the scar area avoid the onset of a unidirectional block with the establishment of the reentry phenomenon thus avoiding induced VTs.

Finally, our clinical experience underlined as left pacing may determine a ventricular remodeling and can certainly lead to a clinical benefit for the patient. However, the detection area of the lead must be carefully evaluated also in relation to a possible scar. In our case, MPP stimulation certainly proved to be an excellent solution for the patient's outcome.

According to the severity of electrical storm in those CRT implanted patients, the possibility of a arrhythmogenic effect of cardiac pacing should be identify. First of all, the identification of patients at risk might be screened with imaging technique (like cardioMRI able to discover areas of transmural myocardial fibrosis). Finally, the influence of LV lead position on determining the proarrhythmic effect has been clearly documented in the MADIT-CRT trial [

15] in which an anterior position of LV lead was associated with a higher risk of arrhythmic events in comparison to a posterior or lateral locations. The explanation seemed to be obtained from the greater presence of myocardial infarction in patients in which the LV stimulation was located in the anterior wall. Finally, CRT patients that manifest an increment of ventricular arrhythmias early after the device implantation should be hospitalized for a longer time in order to monitorized the events.

Author Contributions

All the authors contributed to editing, reviewing and final approval of the article.

Informed Consent Statement

The patient described in this case-report provided informed written consent for the publication of images.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cleland, J.G.; Daubert, J.C.; Erdmann, E.; Freemantle, N.; Gras, D.; Kappenberger, L.; Tavazzi, L. Cardiac resynchronization-Heart Failure (CARE-HF) Study Investigators. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2005, 352, 1539–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bristow, M.R.; Saxon, L.A.; Boehmer, J.; Krueger, S.; Kass, D.A.; De Marco, T.; Carson, P.; DiCarlo, L.; DeMets, D.; White, B.G.; DeVries, D.W.; Feldman, A.M. Comparison of medical therapy , Pacing and Defibrillation inHeart Failure (COMPANION) Investigators. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2004, 350, 2140–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleland, J.G.; Daubert, J.C.; Erdmann, E.; Freemantle, N.; Gras, D.; Kappenberger, L.; Tavazzi, L. Long-term effects of cardiac resynchronization therapy on mortality in heart failure the CARE-HF trial extension phase. Eur Heart J 2006, 27, 1928–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mykytsey, A.; Maheshwari, I.P.; Dhar, G.; Razminia, M.; Zheutlin, T.; Wang, T.; Kehoe, R. Ventricular tachycardia induced by ventricular pacing in severe ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2005, 16, 655–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, H.M.; Verdino, R.J.; Russo, A.M.; Gesterfeld, E.P.; Hsia, H.H.; Lin, D.; Dixit, S.; Cooper, J.M.; Callans, D.J.; Marchlinski, F.E. Ventricular tachycardia storm after initiation of biventricular pacing: incidence, clinical characteristics management and outcome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2008, 19, 708–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, J.M.; Brugada, J.; Antezelevitch, C. Potential proarrhythmic effects of biventricular pacing. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005, 46, 2340–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantharia, B.K.; Patel, J.A.; Nagra, B.S.; Ledley, G.S. Electrical storm of monomorphic ventricular tachycardia after a cardiac-resynchronization-therapy-defibrillator upgrade. Europace 2006, 8, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque C, Trevisi N, Silberbauer J, Oloriz T, Mizuno H, Baratto S, Bisceglia C, Sora N, Marzi A, Radinovic A, Guarracini F, Vergara P, Sala S, Paglino G, Gulletta S, Mazzone P, Cireddu M, Maccabelli G, Della Bella P. Electrical storm induced by cardiac resynchronization therapy is determined by pacing on epicardial scar and can be successfully managed by catheter ablation. Circ Arrhytm Electrophysiol 2014, 7, 1064–1069.

- Asvestas, D.; Balasubramanian, R.; Sopher, M.; Paisey, J.; Babu, G.G. Extended bipolar left ventricular pacing as a possible therapy for late electrical storm induced by cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Electrocardiology 2017, 50, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieweg, W.V.R.; Wood, M.A.; Fernandez, A.; Beatty-Brooks, M.; Masnain, M.; Padwag, A.K. Proarrhythmic risk until antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs: implications in the elderly. Drugs Aging 2009, 26, 997–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massetti, C.M.; Cheng, C.M.; Shape, B.A.; Meier, C.R.; Guglielmo, B.S. The FDA extended warning for intravenous haloperidol and torsades de pointes: how should Institutions respond? J Hosp Med 2010, 5, E8–E16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanti, A.; Micallef, B.; Saijj, J.V.; Serracino-Inglett, A.I.; Borg, J.J. QT shortening : a proarrhythmic safety surrogate measure or an inappropriate surrogate indicator of it? Curr Med Res Opin 2022, 38, 1473–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metha, V.S.; Elliott, M.K.; Sidhu, B.S.; Gould, J.; Porter, B.; Niederer, S.; Rinaldi, C.A. Multipoint pacing for cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2021, 32, 2577–2589. [Google Scholar]

- Menardi, E.; Ballari, G.P.; Goletto, C.; Rossetti, G.; Vado, A. Characterization of ventricular activation pattern and acute hemodynamics during multipoint left ventricular pacing. Heart Rhythm 2015, 12, 1762–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutyifa, V.; Zareba, W.; McNitt, S.; Singh, J.; Hall, W.J.; Polonsky, S.; Goldenberg, I.; Huang, D.T.; Merkely, B.; Wang, P.J.; et al. Left ventricular lead location and the risk of ventricular arrhythmias in the MADIT-CRT trial. Eur Heart J 2013, 34, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).