1. Introduction

There is a growing demand for rapid diagnostic methods to evaluate plant responses to chemicals or environmental conditions in plant biology and agrochemical research. The most common method to diagnose plant responses to chemicals is whole-plant assay in a pot condition [

1]. This requires a large space to grow plants in the glasshouse and much effort including labor, time, and cost. To solve these problems, several rapid methods have been developed such as petri dish assay [

2], growth pouch assay [

3], trimmed stem node assay [

4], and leaf disc assay [

5,

6,

7,

8]. A new approach has also been made to detect plant spectral responses after chemical treatment. The chlorophyll fluorescence (CF) imaging was developed to diagnose plant response to stress including herbicides in field conditions using CF to save time, cost, and labor [

8,

9,

10]. Measuring plant leaf temperature using an infrared (IR) thermal sensor has also been studied to diagnose plant response to stress including herbicides [

11,

12,

13].

However, the capacity of current methods to detect plant responses is constrained by their lack of flexibility, repeatability, and effectiveness [

9]. The primary obstacles to methods of diagnosis are time and space constraints. To effectively demonstrate and evaluate the response of plants, it is necessary to have a sufficiently wide space for plant cultivation. Moreover, a significant amount of labor and time is necessary to cultivate enough plants to validate the response. Furthermore, conducting evaluations in the field with a portable device results in delays and inevitable errors in the plant diagnostic procedure. Therefore, it is crucial to create novel bioassay approaches that can provide a compact and simple approach to assess and diagnose plant responses.

In herbicide discovery and development, herbicide bioassay is essential for not only detecting and quantifying herbicide efficacy but also diagnosing herbicide mode of action. A multi-well plate is a widely used tool in cell culture for carrying out large-scale biological investigations [

14]. Several studies have exhibited the application of multi-well plates for cultivating plants and assessing their responses to herbicides. Little plants or plant parts, such as leaves, were placed into multi-well plates, and spectral image analysis was applied to diagnose and evaluate the responses of plants under stress conditions including herbicide [

15,

16,

17]. These studies demonstrated a good synergy between the two methods, however, combining the use of spectral image analysis had not been previously investigated.

Therefore, this study was conducted to develop a multi-well plate assay method for herbicide screening. To detect plant response to herbicides, plant spectral images were acquired after herbicide treatment using RGB, IR thermal, and CF sensors and analyzed for diagnosing herbicide efficacy and mode of action.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant materials and growing plant in multi-well plate

As a model plant to diagnose plant responses to herbicide in multi-well plate, a monocot weed crabgrass, Digitaria ciliaris, was selected. Crabgrass seeds were collected in 2021, air-dried, and stored in a cold chamber maintained at 4oC until use. A number of tests were conducted to optimize the growing condition of the weed in multi-well plate consisting of 24 wells (4 x 6) with 15.5 mm of diameter (SPL Life Sciences, Korea). Finally, seeds of crabgrass were sown on multi-well plate at a density of 15 seeds well-1 and incubated in a growth chamber (Hanbaek Science, Korea) maintained at 30oC/20℃ (day/night) with a 16 hours photoperiod until the 1- leaf stage.

2.2. Herbicide treatment

When crabgrass reached the 1-leaf stage, herbicide was sprayed using a CO

2-pressurized, belt-driven sprayer (R&D sprayers, USA) fitted with a flat fan nozzle 8001 (Spraying Systems Co., USA) to deliver a spray volume of 300 L ha

-1. Six herbicides with different modes of action were selected; paraquat (PSI inhibitor), tiafenacil (PPO inhibitor), penoxulam (ALS inhibitor), isoxaflutole (HPPD inhibitor), glufosinate (GS inhibitor), and glyphosate (EPSPS inhibitor) (

Table 1). Based on our preliminary test and growth stage of crabgrass grown in multi-well plate, a quarter dose (x 1/4) of their recommended doses was used.

As each multi-well plate has 24 wells arranged in 6 rows with 4 wells row-1, only two rows were sprayed with each herbicide by covering the other rows with plastic plates large enough to cover the rows. Following herbicide application, multi-well plates were placed in the growth chamber maintained at 30oC/20℃ (day/night) with a 16 hours photoperiod. All treatments were arranged in a completely randomized design with 8 replications in the growth chamber. Following the herbicide treatment, the weed plants were relocated to the growth chamber.

2.3. Spectral image acquisition and analysis

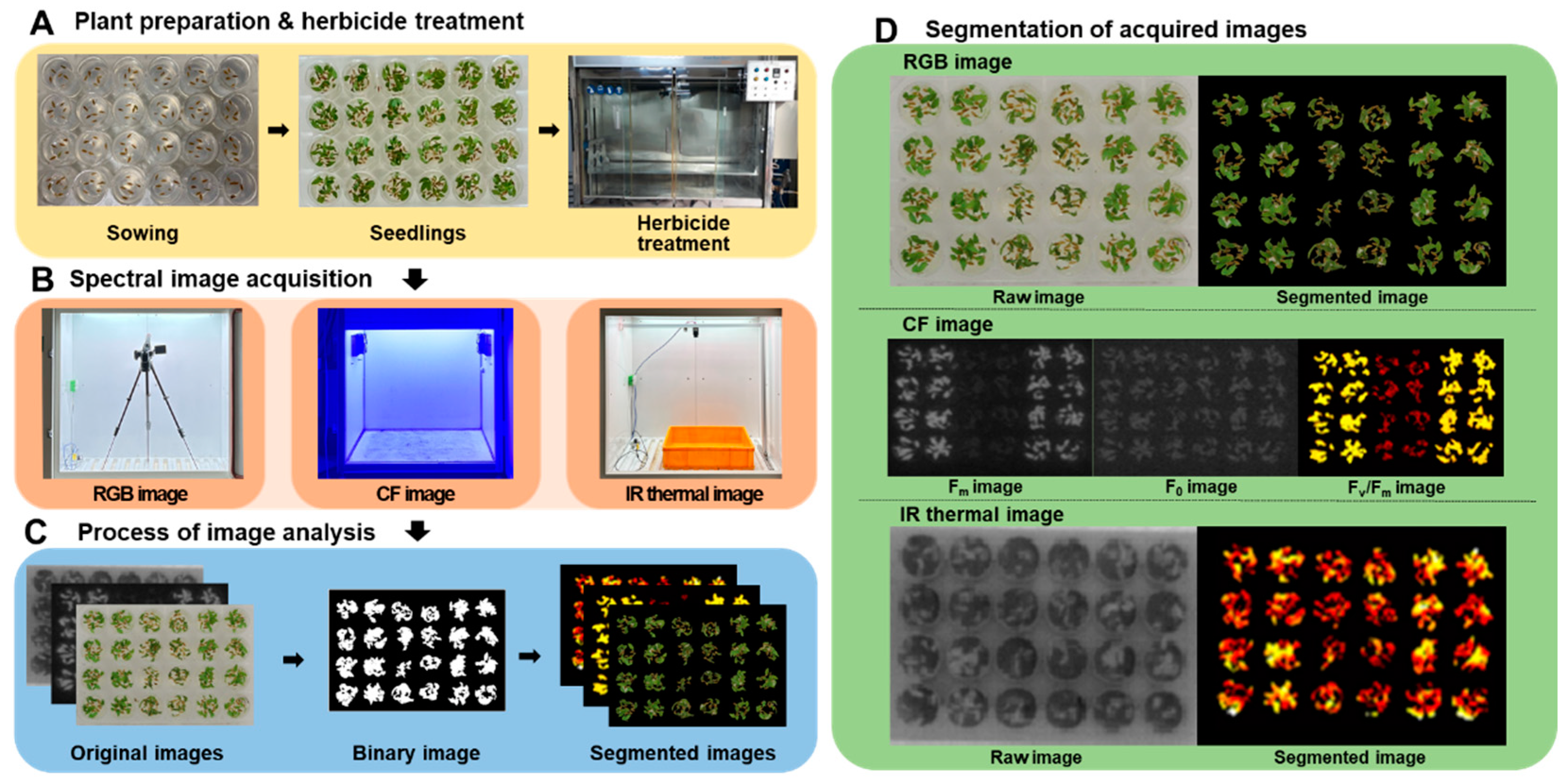

RGB, chlorophyll fluorescence (CF), and IR thermal images were acquired after herbicide treatment and analyzed using MATLAB R2023b (The MathWorks Inc., USA).

2.3.1. RGB image

RGB images of crabgrass plants growing in multi-well plates were acquired using a CMOS camera (EOS-600D, Canon, Japan) at 3, 6, 24, 48, 72, and 120 hours after herbicide treatment (HAT). Acquired RGB images were then analyzed after white balancing and transforming the RGB image into the Lab color space to segment crabgrass from the image. Otsu thresholding was then applied in a* channel in Lab color space to eliminate the background (

Figure 1). To measure the visual responses and level of greenness in plants, the modified Normalized Difference Index (mNDI) and Excess Green Index (ExG) were calculated by normalizing the red (R), green (G), and blue (B) values of crabgrass using the following formulae,

where NDI

h and NDI

0 indicate NDI values of weed plants treated with herbicide and untreated control, respectively.

2.3.2. CF image

Chlorophyll fluorescence (CF) images of crabgrass plants on well plates were acquired using an SNU-KIST 2 imaging system (Seoul National University/KIST, Korea) at 3, 6, 24, 48, 72, and 120 HAT. For each CF image, pixel intensity of crabgrass was averaged to derive CF value after removing the background by Otsu thresholding. CF image parameters were then calculated using the following formulae,

where

F0 is the ground CF at dark-adapted state,

Fm is the CF value at 1 second when a plant emits maximum fluorescence and

Fs is the CF value at 60 seconds when it comes to a steady state. The CF parameters were then normalized by dividing the values of crabgrass treated with herbicides by those of untreated control.

2.3.3. IR thermal image

IR thermal images of crabgrass on multi-well plate were acquired using an A65sc infrared camera (FLIR, Sweden) mounted in the growth chamber (Gaooze, Korea) maintained at 33℃ at 3, 6, 24, 48, 72, and 120 HAT. The image registration algorithm was employed to extract the leaf temperature of crabgrass by verifying the plant body using the corresponding RGB image segmented in 2.2.1. The temperature difference was subsequently calculated using leaf temperature data derived from IR thermal image analysis using the following formula,

where

Th and

T0 indicate leaf temperatures of weed plants treated with herbicide and untreated control, respectively.

2.4. Statistical analysis

All plant spectral image data were initially subjected to the two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine statistical significance in the effects of two factors, herbicide and time, on spectral responses of crabgrass to herbicides tested. Normalized spectral parameters were then subjected to principal component analysis (PCA) to test if spectral responses can be separated and clustered depending on herbicide mode of action. Initially PCA was performed for each time point (3, 6, 24, 48, 72, and 120 HAT) separately and then for pooled data. All statistical analyses were conducted using R 3.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

3. Results

3.1. Optimization of growing crabgrass in the multi-well plate

Considering the fast and even germination and compact plant growth, crabgrass was selected as a model plant for this study. Crabgrass seeds were sown on wells of 24- and 96-well plates and checked their seedling growth. The well size of the 96-well plate was too small to grow crabgrass, while that of the 24-well plate was large enough to grow crabgrass. Therefore, the 24-well plate was selected for further studies. To optimize seed germination and seedling growth, various media including water, agarose (0.4%, w/v), and Murashige and Skoog medium were tested and found that that the medium composed solely of agarose (Inclonebiotech Co., Korea) was appropriate [

18]. To optimize growth condition in the 24-well plate, number of seeds well

-1 and temperature from germination to seedling growth were tested and found that 15 seeds well

-1 appeared to be appropriate, and optimum growth condition in the 24-well plate was 30℃/20℃ (day/night) with a 16 hours photoperiod until the 1-leaf stage. At the 1-leaf stage, crabgrass had sufficient canopy size to exhibit spectral responses to herbicides. Therefore, our results demonstrated that crabgrass can be grown in the 24-well plates for herbicide bioassay. Crabgrass seeds at 15 seeds well

-1 need to be sown on wells containing 0.8 ml of 0.4% agar medium and incubated in the growth chamber maintained at 30

oC/20℃ (day/night) with a 16 hours photoperiod until the 1-leaf stage (5 days). After herbicide treatment, crabgrass needs to be placed in the growth chamber for image acquisition.

3.2. Changes in spectral response of crabgrass to herbicides

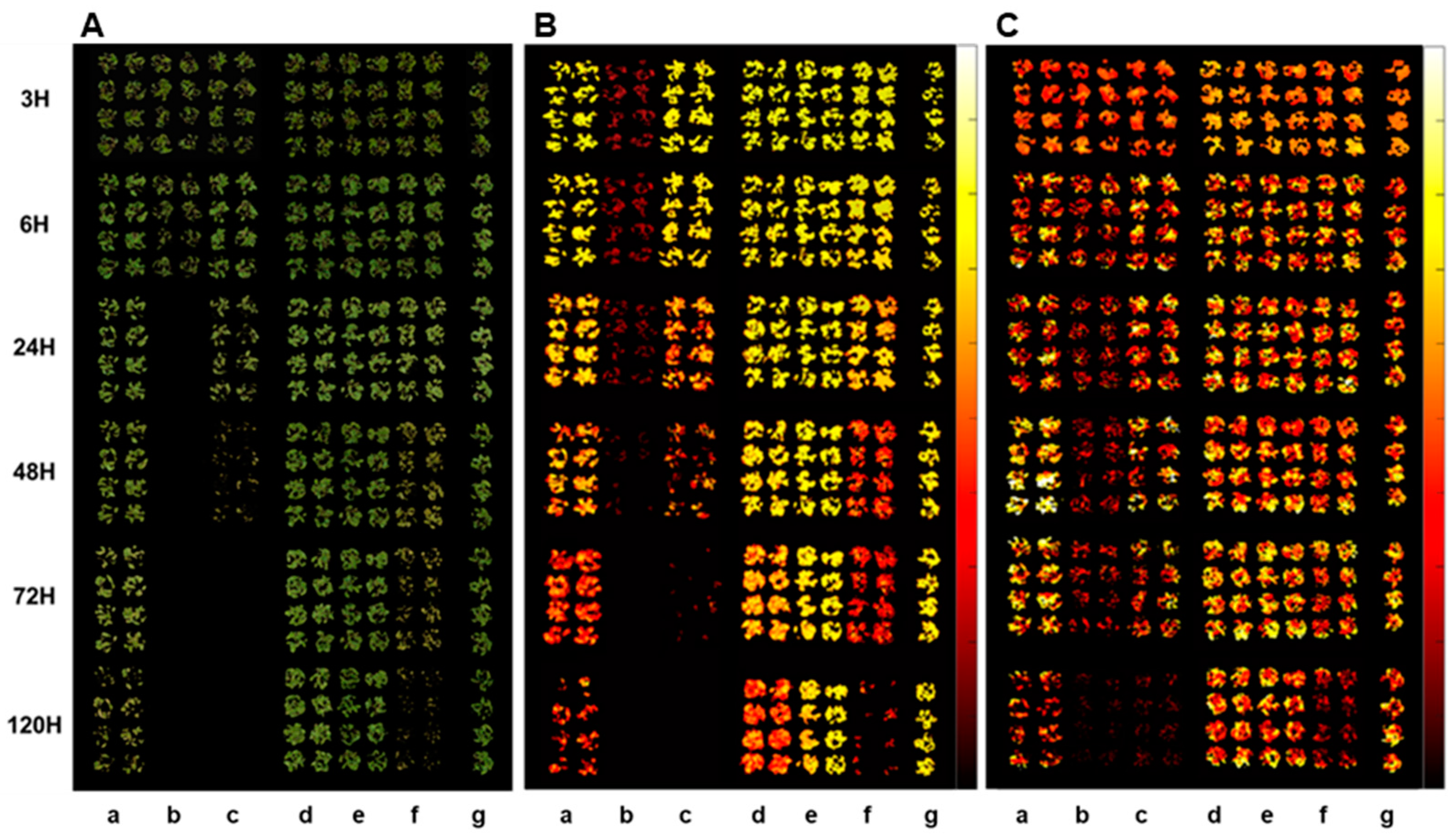

Plant spectral images acquired by different sensors, RGB, CF, and IR thermal sensors, showed clear differences depending on herbicide mode of action and time after herbicide treatment (

Figure 2). Spectral changes by herbicide treatment became apparent as time after herbicide treatment progressed. The fastest spectral change was observed in paraquat (PSI) treatment in all spectral images, followed by tiafenacil (PPO) and glufosinate (GS), while the slowest one was observed in penoxsulam (ALS), followed by isoxaflutole (HPPD) and glyphosate (EPSPS). Spectral changes in RGB image include dehydration, chlorosis and necrosis, which depend on herbicide mode of action and time after herbicide treatment (

Figure 2A). In the case of CF image, the most notable and fast change was observed in paraquat (PSI) treatment even at 3 HAT and distinctive difference between herbicide modes of action was observed from 48 HAT (

Figure 2B). A relatively slow change but still clear difference between herbicide modes of action were also observed in IR thermal image (

Figure 2C). ANOVA of all spectral parameters estimated by spectral image analysis showed very high statistical significance in both herbicide and time, and their interaction (

Table 2). Considering F value, herbicide affected RGB and CF images more significantly than time, while it affected IR thermal image less significantly than time. In particular, the difference in F

v/F

m and F

d/F

m between herbicide and time were greatest, suggesting that these CF parameters may be useful to diagnose herbicide modes of action.

3.3. Changes in RGB spectral responses to herbicides

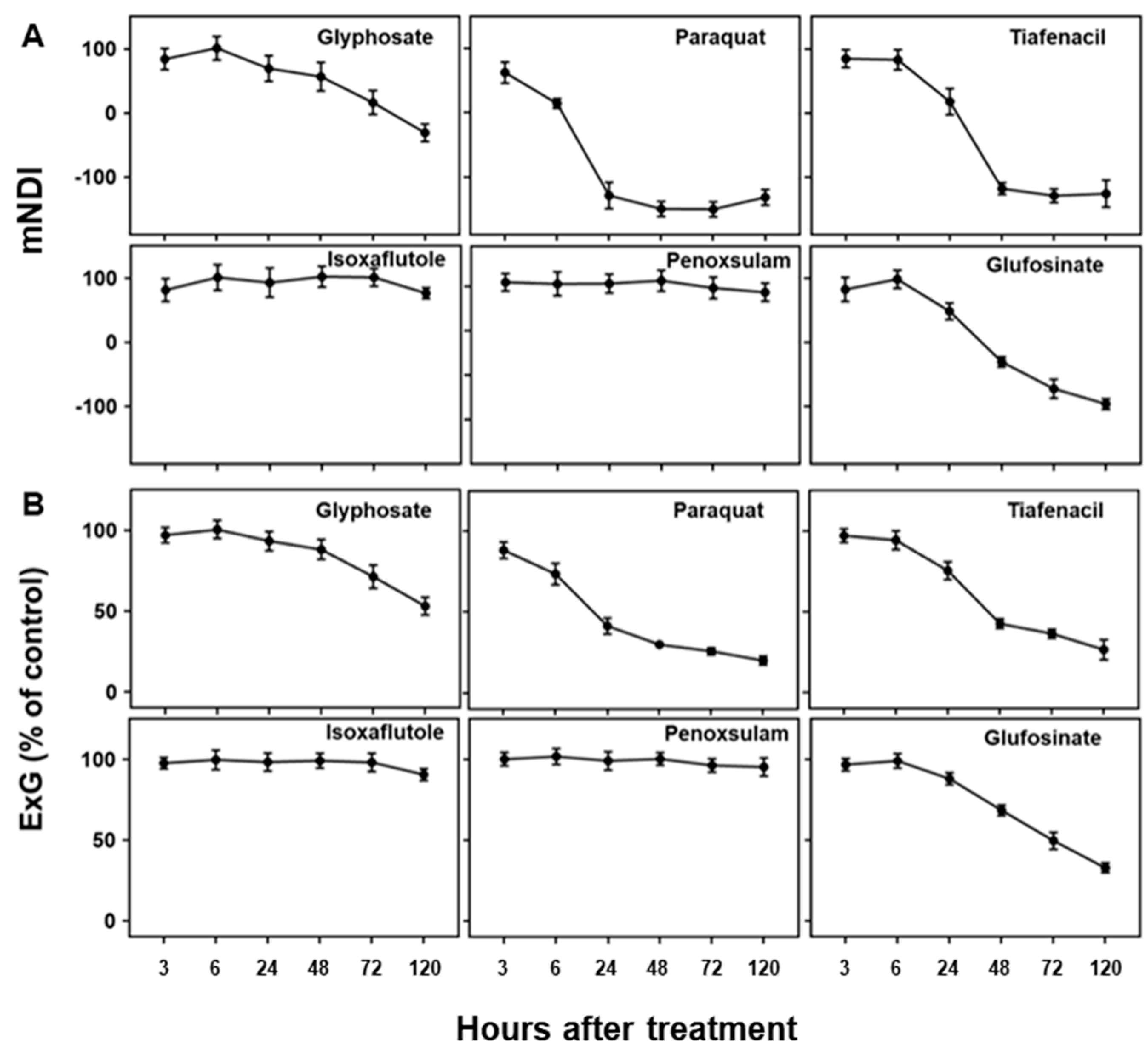

As visual symptoms became evident, mNDI and ExG values experienced a significant reduction (

Figure 3). mNDI and ExG exhibited comparable trends to visual symptoms, with a gradual decrease over time. Paraquat (PSI) showed the fastest and greatest reduction in mNDI and ExG values, followed by tiafenacil and glufosinate. mNDI and ExG values of paraquat dropped to 53.9% and 73.5% compared to the untreated control, respectively, at 6 HAT. This reduction aligned with the rapid herbicidal symptom of paraquat (PSI) demonstrated in the RGB images (

Figure 2A). Crabgrass plants exhibited near-fatal conditions at 24 HAT with paraquat (PSI) and 48 HAT with tiafenacil (PPO). Glufosinate (GS) and glyphosate (EPSPS) started to show color change at 24 HAT and 72 HAT, respectively, coinciding with the decreases in mNDI and ExG values. Isoxaflutole (HPPD) and penoxsulam (ALS) showed minimal herbicidal activity based on visual observations, and no significant changes observed in mNDI and ExG after their treatment until 120 HAT. These differential changes in mNDI and ExG after herbicide treatment indicate that mNDI and ExG values can be used to diagnose herbicidal activity and mode of action by plant image analysis.

3.4. Changes in CF spectral responses to herbicides

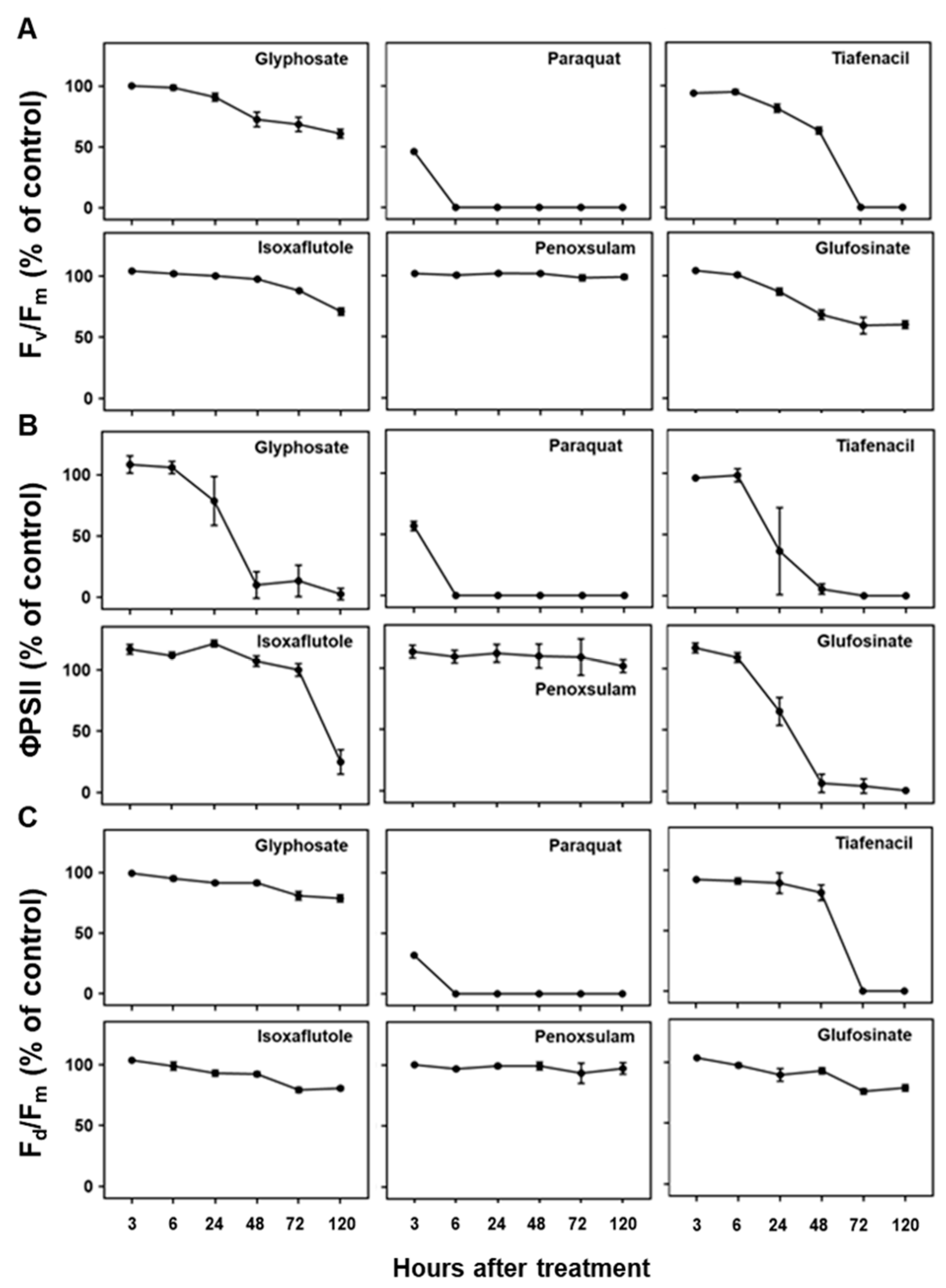

Three CF parameters, F

v/F

m, ΦPSII, and F

d/F

m, demonstrated differential changes over time after herbicide treatment depending on herbicide mode of action (

Figure 4). Except penoxsulam, which did not show any herbicidal activity against crabgrass, all the other herbicides such as paraquat (PSI), glufosinate (GS), tiafenacil (PPO), glyphosate (EPSPS), and isoxaflutole (HPPD) resulted in significantly reduced CF parameters compared to the untreated control. Herbicide treatment primarily resulted in a decrease in all the CF parameters, with variations depending on herbicide mode of action. Except for penoxsulam (ALS), CF spectral responses to herbicides were more immediate and pronounced compared to the other spectral responses such as RGB and IR thermals. Among herbicides, paraquat showed the fastest and greatest reduction in all the CF parameters even at 3 HAT, resulting in significant reduction of F

v/F

m, ΦPSII, and F

d/F

m, up to 45.9%, 56.7%, and 31.8% of the untreated control, respectively, and reached at 0% 6 HAT. Tiafenacil (PPO) showed the second fastest and greatest significant reduction in all the CF parameters from 24 HAT, reaching to almost zero at 72 HAT. Glufosinate (GS) and glyphosate (EPSPS) displayed a sudden decrease in ΦPSII at 24 HAT, but their decreases in F

v/F

m and F

d/F

m were not that great when compared to ΦPSII. Isoxaflutole (HPPD) did not exhibit a significant change in all the CF parameters until 48 HAT, but a sudden decrease in ΦPSII was observed at 120 HAT, when no changes in RGB and IR thermal spectral responses were observed (

Figure 3 and

Figure 5).

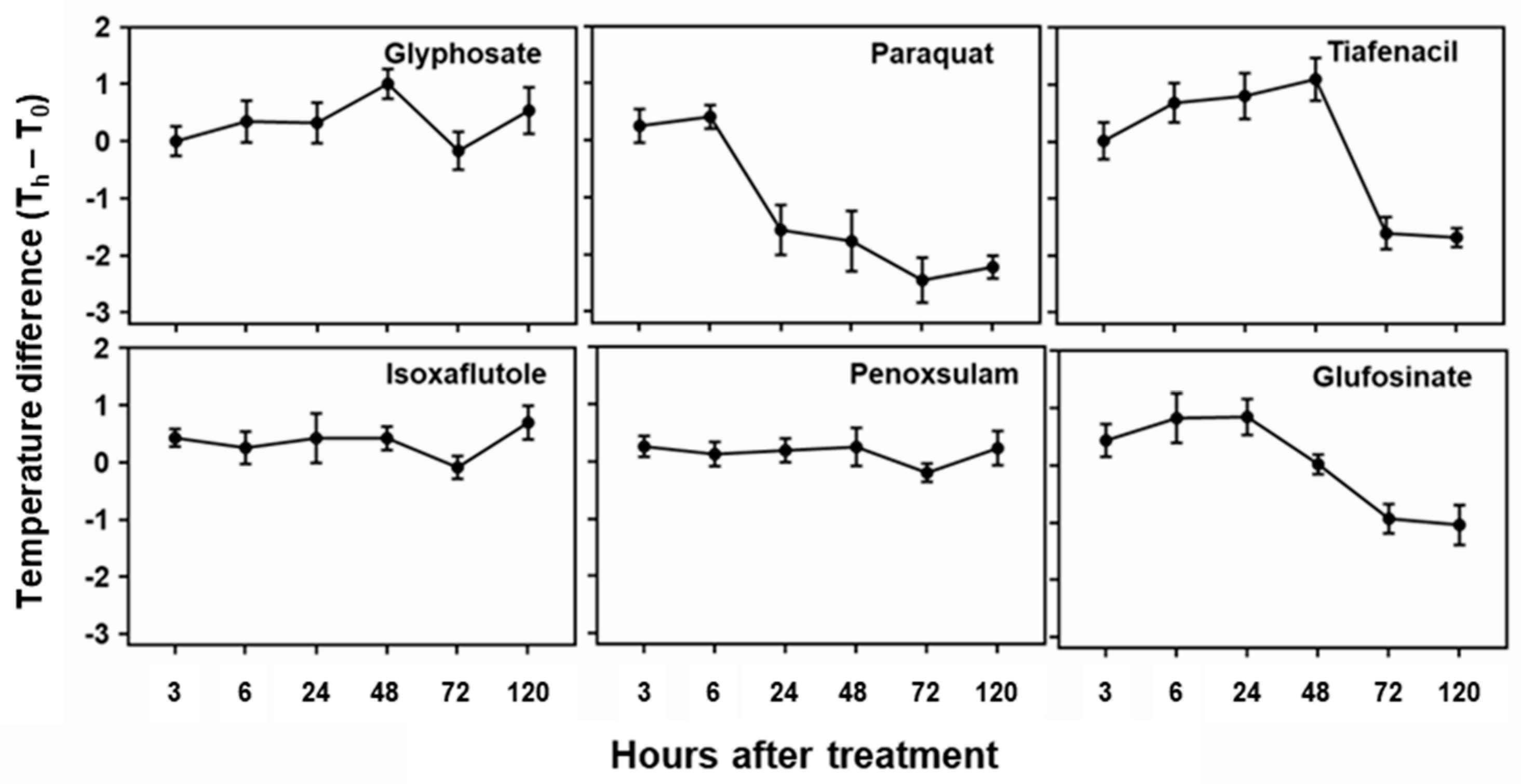

3.5. Changes in IR thermal spectral responses to herbicides

The temperature difference estimated based on plant leaf temperature determined by IR thermal image analysis also showed distinctive differences among herbicides tested in this study (

Figure 5). All tested herbicides exhibited distinct temperature variations compared to the untreated control. Initial increase in temperature difference was observed for paraquat, tiafenacil, glufosinate, and glyphosate, and then decrease at a certain point with plants being dehydrated. As observed in the other spectral responses, paraquat (PSI) showed the greatest change in temperature difference, showing increase until 6 HAT and then sudden decrease from 24 HAT. Glufosinate (GS) showed continuous increase in temperature difference until 24 HAT, while tiafenacil (PPO) and glyphosate (EPSPS) showed increase until 48 HAT, and then decrease afterwards. Isoxaflutole (HPPD) displayed significant increase as late as 120 HAT, while penoxsulam (ALS) did not show any noticeable change even at 120 HAT.

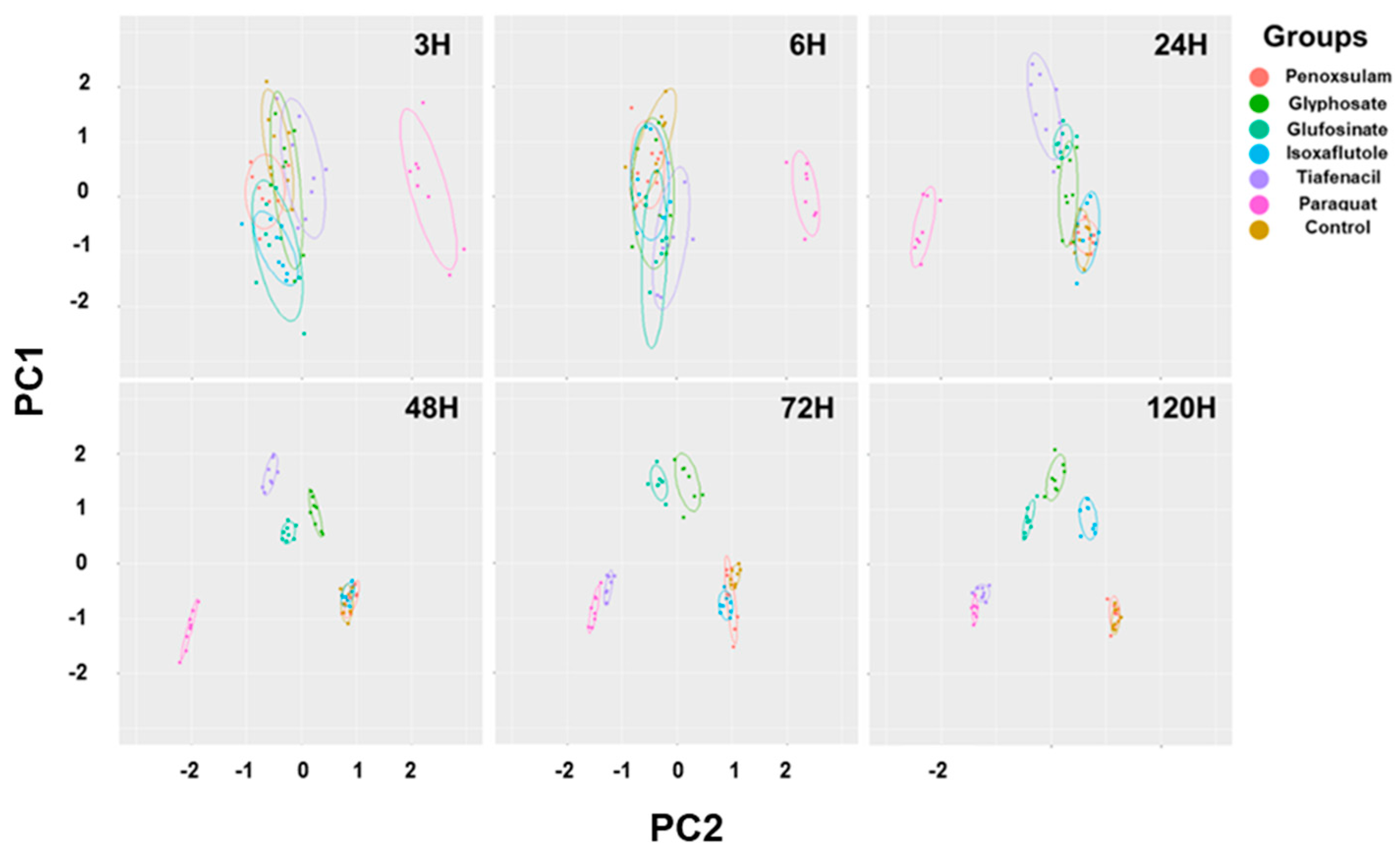

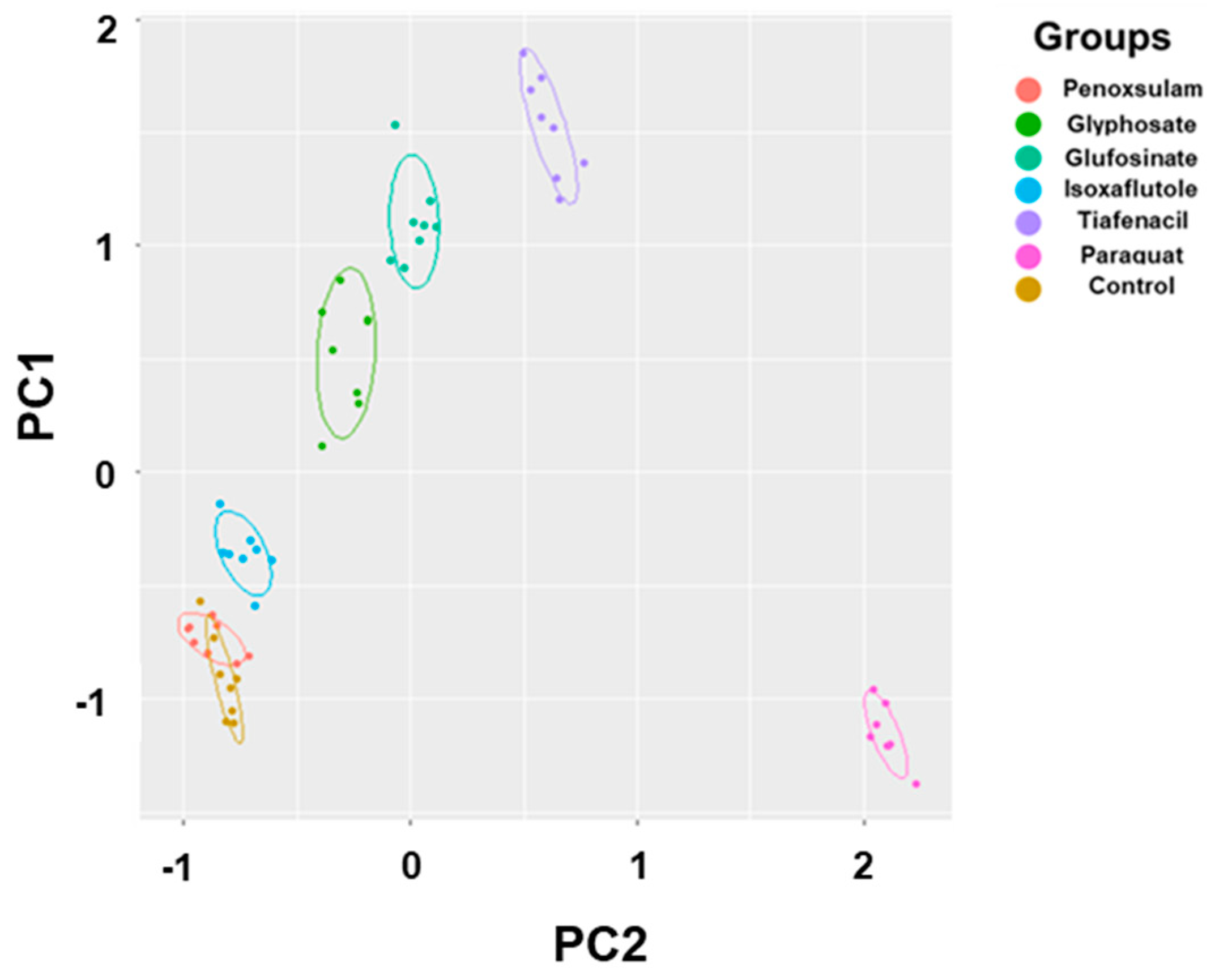

3.6. Principal Component Analysis

The 2-dimensional PCA of all spectral image parameters observed at different timings after herbicide treatment showed gradual clustering of herbicides with time depending on herbicide mode of action (

Figure 6,

Table S1). Paraquat (PSI) exhibited noticeable separation from the other herbicides as early as 3 HAT. At 24 HAT, tiafencial (PPO)_ became independently clustered from the other herbicides. At 48 HAT, glufosinate (GS) and glyphosate (EPSPS) were independently clustered. Isoxaflutole (HPPD) was the last one separated from the other herbicides as late as 120 HAT. However, penoxsulam (ALS) failed to be independently clustered even at 120 HAT. The PCA using the pooled data from 3 HAT until 120 HAT demonstrated clear clustering of herbicides based on herbicide mode of action except for penoxsulam (ALS), which was not separated from untreated control due to very low efficacy against crabgrass (

Figure 7,

Table S2). The 3-dimensional PCA for spectral image parameters observed each time point and pooled data also showed similar clustering depending on herbicide mode of action (

Figures S1 & S2). For quick acting herbicides such as paraquat (PSI), tiafenacil (PPO) and glufosinate (GS), they required only 2 days after herbicide for clustering by herbicide mode of action, while for slow acting herbicides such as glyphosate (EPSPS) and isoxaflutole (HPPD), they required a bit longer period after herbicide treatment.

4. Discussion

4.1. Spectral image responses to herbicides

Plant imaging has been becoming a core technique for plant phenotyping and diagnosis in plant and agricultural sciences [

19]. One of the benefits of plant image analysis is that it allows non-destructive and high-throughput screening of plant responses [

19,

20,

21,

22]. In this study, we developed multi-well plate assay by combining with plant spectral image analysis for rapid diagnosis of herbicide activity and mode of action. Three different sensors, RGB, CF and IR thermal sensors, were used to acquire spectral responses at different time points after herbicide treatment and showed differential spectral responses depending on herbicide mode of action and time when spectral images were acquired, suggesting a potential diagnosis of herbicide mode of action based on spectral image data. Among spectral image parameters, those related to CF image seemed to be most responsive to herbicide, particularly ΦPSII (

Figure 4). Other image parameters derived from RGB and IR thermal images were also informative although they appeared to be relatively slow and less responsive than CF image (

Figure 3 &

Figure 5).

RGB image is most commonly used for analyzing vegetation indices associated with plant growth and canopy development and has a broad range of applications because it is easily accessible and provides informative and high-resolution results, even with commercially available cameras installed in smartphone [

23]. In this study, RGB color change in response to herbicide was analyzed by RGB image analysis, particularly the level of greenness in the leaves as leaf discoloration such as yellowing and bleaching are the most common symptoms after herbicide treatment [

24]. The mNDI and ExG values showed significant evidence of changes in leaf color and suppression of plant development resulting from herbicide action (

Figure 2A &

Figure 3). Moreover, the observed changes varied depending on the herbicide mode of action. The herbicides related to reactive oxygen species (ROS), including paraquat (PSI), tiafenacil (PPO) and glufosinate (GS) exhibited rapid changes in these RGB-based parameters. Glyphosate (EPSPS) showed a rather mild and slow response, while isoxaflutole (HPPD) and penoxsulam (ALS) showed very little changes. These parameters allowed for the explanation of plants’ responses to herbicide depending on mod of action, suggesting that mNDI and ExG are highly useful to quantify plant damage caused by herbicides and to diagnose herbicide mode of action.

Given that photosynthesis requires plant pigments, antioxidant systems, and proteins linked to several enzymes and carbohydrates, any stress experienced by plants is likely to impact photosynthesis [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Herbicides act on distinct targets depending on the mode of action and consequently impact photosynthesis in various ways. In our study, paraquat exhibited the most rapid and significant reduction in CF parameters within 3 HAT, despite the absence of any apparent visual impact, while no discernible difference in CF image was observed in penoxsulam (ALS) treatment (

Figure 2B &

Figure 4). Other herbicides such as tiafenacil (PPO), glufosinate (GS), glyphosate (EPSPS), and isoxaflutole (HPPD) exhibited distinct herbicide effects on CF images and parameters based on their respective modes of action. Among these herbicides, tiafenacil (PPO) was the fastest, followed by glufosinate (GS), glyphosate (EPSPS), and isoxaflutole (HPPD). Interestingly, isoxaflutole (HPPD) showed a sudden decrease in the CF parameters at 120 HAT. Using CF image analysis, herbicide effects could be detected at much earlier timings compared to other image analysis, and the extent of decrease were quite larger. In overall, CF image analysis was more discernible in terms of differentiating herbicides depending on their modes of action, suggesting its suitability for high-throughput screening (HTS) of herbicide molecules.

Leaf temperature is strongly correlated with overall physiological condition of the plant, particularly the conductance of stomata and the rate of photosynthesis. A symptom of plant stress is the closure of stomata in leaves, which is accompanied by a reduction in the absorption of carbon dioxide during photosynthesis. This ultimately results in a decrease in transpiration [

29], and the temperature of stressed leaves rises due to reduced transpiration. Leaf temperature is a reliable indicator for detecting numerous types of stress in plants, such as drought, salt stress and herbicide that affect photosynthesis [

30,

31,

32]. In our study, the IR thermal images revealed that the leaf temperature reached its highest point when the effects of herbicides and visible damage became evident (

Figure 2C &

Figure 5). Early initial increase in the leaf temperature and its subsequent decrease at a certain point after herbicide treatment varied with herbicide mode of action, implying that change in plant leaf temperature measured by IR thermal image analysis may also be used to explain herbicide mode of action.

4.2. Diagnosis of herbicide mode of action based on spectral response data

PCA using all spectral data (RGB, CF, and IR thermal image parameters) successfully differentiated herbicides and clustered depending on their modes of action (

Figures 6 & 7). The results demonstrated a sequential separation of the tested herbicides following the order of spectral responsiveness; paraquat (PSI) was the fastest, followed by tiafenacil (PPO), glufosinate (GS), glyphosate (EPSPS), and isoxaflutole (HPPD). Penoxsulam (ALS), which did not have any herbicidal activity against crabgrass in this study, was located very close to the untreated control until the end of the measurement. The results obtained by 3 dimensional PCA also showed consistent with those by 2 dimensional PCA, showing more distinct disparities among herbicide modes of action (

Table S2,

Figure S1, and

Figure S2). Our results thus demonstrate that multi-well plate assay combined with plant spectral image analysis can be used to diagnose and investigate herbicide mode of action.

4.3. High throughput screening of herbicide using multi-well plates assay combined with plant spectral image analysis

The use of multi-well plates in herbicide screening has been reported in several previous studies [

15,

16,

17]. Those studies mainly adopted CF image analysis for early and rapid detection of herbicide effects. In our study, various plant spectral images were used to investigate visible RGB and invisible IR thermal and CF spectral responses to herbicide. To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first attempt acquiring and analyzing 3 different types of spectral images for diagnosing herbicide mode of action using multi-well plate. The multi-well plate assay combined with spectral image analysis showed a favorable synergy in the whole process of the experiment including plant preparation, image acquisition and analysis. In comparison with the conventional whole-plant herbicide assay, our method can test many herbicidal chemicals in a limited space and time. Multiple studies using the multi-well plate assay can be simultaneously conducted in a controlled growth chamber or laboratory equipped with image acquisition system, enabling automatic herbicide bioassay, high-throughput screening (HTS) in herbicide discovery and development.

Nevertheless, there is still much room to be improved for HTS using our method. In plant preparation, automatic preparation of growth medium and growing plants will save time and effort dramatically. Automatic image acquiring system that collects continual spectral responses will save our efforts and provide more detailed spectral understanding to diagnose herbicide mode of action. Furthermore, improving the spraying system will boost the speed and effectiveness of the multi-well plate assay for herbicide screening. If herbicide spray can be precisely made to each well independently, the multi-well plate assay combined with plant spectral image analysis can handle much more herbicidal molecules in herbicide discovery stage.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1. The proportion of variance that the first and second principal component (PC) explained (% of total variance). Table S2. The proportion of variance that the first, second, and third principal component (PC) explained (% of total variance). Figure S1. PCA results of six spectral parameters of crabgrass at 3 h, 6 h, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, and 120 h after treatment of herbicides with different modes of action. These images represent PCA results using the PC1, PC2, and PC3 axes, and each symbol represents the replication. Figure S2. PCA results of six spectral parameters of crabgrass by aggregating all of the data including 3 h, 6 h, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, and 120 h after treatment of herbicides with different modes of action. These images represent PCA results using the PC1, PC2, and PC3 axes, and each symbol represents the replication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.-S.K.; Methodology, S.-M.J., T.-K.N.; Investigation, S.-M.J.; Software, S.-M.J., T.-K.N.; Data Curation, S.-M.J.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, S.-M.J., T.-K.N.; Visualization, S.-M.J., T.-K.N.; Writing – Review & Editing, D.-S.K.; Supervision, D.-S.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture and Forestry (IPET) (321056-05-1-HD050).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Olofsdotter, M.; Olesen, A.; Andersen, S.; Streibig, J. A comparison of herbicide bioassays in cell cultures and whole plants. Weed Research 1994, 34, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckie, H.J.; Friesen, L.F.; Nawolsky, K.M.; Morrison, I.N. A rapid bioassay to detect trifluralin-resistant green foxtail (Setaria viridis). Weed Technology 1990, 4, 505–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lim, S.; Kim, J.; Song, J.; Yook, M.; Nah, G.; Valverde, B.; Kim, D. Quantifying herbicide dose–response and resistance in Echinochloa spp. by measuring root length in growth pouches. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 2015, 95, 1181–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D.-S.K.; Caseley, J.C.; Brain, P.; Riches, C.R.; Valverde, B.E. Rapid detection of propanil and fenoxaprop resistance in Echinochloa colona. Weed Science 2000, 48, 695-700. [CrossRef]

- Koger, C.H.; Shaner, D.L.; Henry, W.B.; Nadler-Hassar, T.; Thomas, W.E.; Wilcut, J.W. Assessment of two nondestructive assays for detecting glyphosate resistance in horseweed (Conyza canadensis). Weed Science 2005, 53, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaner, D.L.; Nadler-Hassar, T.; Henry, W.B.; Koger, C.H. A rapid in vivo shikimate accumulation assay with excised leaf discs. Weed Science 2005, 53, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Varanasi, V.; Perez-Jones, A. A nondestructive leaf-disk assay for rapid diagnosis of weed resistance to multiple herbicides. Weed Science 2021, 69, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukupová, J.; Smatanová, S.; Nedbal, L.; Jegorov, A. Plant response to destruxins visualized by imaging of chlorophyll fluorescence. Physiologia Plantarum 2003, 118, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lim, S.; Kim, J.; Nah, G.; Fischer, A.; Kim, D. Leaf chlorophyll fluorescence discriminates herbicide resistance in Echinochloa species. Weed Research 2016, 56, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaerle, L.; Leinonen, I.; Jones, H.G.; Van Der Straeten, D. Monitoring and screening plant populations with combined thermal and chlorophyll fluorescence imaging. Journal of Experimental Botany 2007, 58, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.G. Application of thermal imaging and infrared sensing in plant physiology and ecophysiology. In Advances in botanical research; Elsevier: 2004; Volume 41, pp. 107-163.

- Kim, J.-W.; Lee, T.-Y.; Nah, G.; D.-S.K. Potential of thermal image analysis for screening salt stress-tolerant soybean (Glycine max). Plant Genetic Resources 2014, 12, S134-S136. [CrossRef]

- Stoll, M.; Jones, H.G. Thermal imaging as a viable tool for monitoring plant stress. OENO One 2007, 41, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Tian, Z.; Hao, N.; Bachman, H.; Zhang, P.; Hu, J.; Huang, T.J. Acoustofluidic multi-well plates for enrichment of micro/nano particles and cells. Lab on a Chip 2020, 20, 3399–3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbagallo, R.P.; Oxborough, K.; Pallett, K.E.; Baker, N.R. Rapid, noninvasive screening for perturbations of metabolism and plant growth using chlorophyll fluorescence imaging. Plant Physiology 2003, 132, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Diego, N.; Fürst, T.; Humplík, J.F.; Ugena, L.; Podlešáková, K.; Spíchal, L. An automated method for high-throughput screening of Arabidopsis rosette growth in multi-well plates and its validation in stress conditions. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, A.D.; Collier, C.J.; Flores, F.; Mercurio, P.; O’Brien, J.; Ralph, P.J.; Negri, A.P. A miniature bioassay for testing the acute phytotoxicity of photosystem II herbicides on seagrass. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0117541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Classic Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiologia Plantarum 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, T.K.; Kim, D.S. Weed research using plant image science. Weed & Turfgrass Science 2018, 7, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.; Bachik, N.A.; Muhadi, N.A.; Yusof, T.N.T.; Gomes, C. Non-destructive techniques of detecting plant diseases: A review. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology 2019, 108, 101426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaari, M.S.M.; Mertens, S.; Verbraeken, L.; Dhondt, S.; Inzé, D.; Bikram, K.; Scheunders, P. Non-destructive analysis of plant physiological traits using hyperspectral imaging: A case study on drought stress. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 195, 106806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patane, P.; Vibhute, A. Chlorophyll and nitrogen estimation techniques: A Review. International Journal of Engineering Research and Reviews 2014, 2, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Padmavathi, K.; Thangadurai, K. Implementation of RGB and grayscale images in plant leaves disease detection–comparative study. Indian Journal of Science and Technology 2016, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, G.; Netherland, M. Herbicide assays for predicting or determining plant responses in aquatic systems. Journal Of Aquatic Plant Management 2018, 56, 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Blokhina, O.; Virolainen, E.; Fagerstedt, K.V. Antioxidants, oxidative damage and oxygen deprivation stress: a review. Annals of Botany 2003, 91, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Römer, S.; Fraser, P.D. Recent advances in carotenoid biosynthesis, regulation and manipulation. Planta 2005, 221, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumesh, K.; Ninsawat, S.; Som-ard, J. Integration of RGB-based vegetation index, crop surface model and object-based image analysis approach for sugarcane yield estimation using unmanned aerial vehicle. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2021, 180, 105903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Chen, K.; Chen, T.; Li, H.; Li, W.; Cheng, T.; Xia, F.; Lou, Z.; Geng, T.; Sun, D. Monitoring weed mechanical and chemical damage stress based on chlorophyll fluorescence imaging. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1188981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgeon, R.; Wolf, S. Phloem transport: cellular pathways and molecular trafficking. Annual Review of Plant Biology 2009, 60, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineda, M.; Barón, M.; Pérez-Bueno, M.-L. Thermal imaging for plant stress detection and phenotyping. Remote Sensing 2020, 13, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinonen, I.; Jones, H.G. Combining thermal and visible imagery for estimating canopy temperature and identifying plant stress. Journal of Experimental Botany 2004, 55, 1423–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimwe, R.; Abutaleb, K.; Ahmed, F. Applications of thermal imaging in agriculture—A review. Advances in Remote Sensing 2014, 3, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The overall process of multi-well plate assay combined with spectral image analysis. A: Plant preparation and herbicide treatment, B: Spectral image acquisition, C: Process of image analysis, D: Segmentation of acquired images.

Figure 1.

The overall process of multi-well plate assay combined with spectral image analysis. A: Plant preparation and herbicide treatment, B: Spectral image acquisition, C: Process of image analysis, D: Segmentation of acquired images.

Figure 2.

RGB (A), CF (B), and IR thermal (C) images of crabgrass at 3, 6, 24, 48, 72, and 120 hours after treatment of herbicides, (a) glyphosate (EPSPS), (b) paraquat (PSI), (c) tiafenacil (PPO), (d) isoxaflutole (HPPD), (e) penoxsulam (ALS), (f) glufosinate (GS), and (g) untreated control.

Figure 2.

RGB (A), CF (B), and IR thermal (C) images of crabgrass at 3, 6, 24, 48, 72, and 120 hours after treatment of herbicides, (a) glyphosate (EPSPS), (b) paraquat (PSI), (c) tiafenacil (PPO), (d) isoxaflutole (HPPD), (e) penoxsulam (ALS), (f) glufosinate (GS), and (g) untreated control.

Figure 3.

Changes in (A) mNDI and (B) ExG values over time after treatment of herbicides with different modes of action.

Figure 3.

Changes in (A) mNDI and (B) ExG values over time after treatment of herbicides with different modes of action.

Figure 4.

Changes in chlorophyll fluorescence parameters including (A) Fv/Fm, (B) ΦPSII, and (C) Fd/Fm over time after treatment of herbicides with different modes of action.

Figure 4.

Changes in chlorophyll fluorescence parameters including (A) Fv/Fm, (B) ΦPSII, and (C) Fd/Fm over time after treatment of herbicides with different modes of action.

Figure 5.

Changes in temperature difference over time after treatment of herbicides with different modes of action.

Figure 5.

Changes in temperature difference over time after treatment of herbicides with different modes of action.

Figure 6.

PCA results of six spectral parameters of crabgrass observed at 3, 6, 24, 48, 72, and 120 hours after herbicide treatment with different modes of action. Each symbol represents the replication.

Figure 6.

PCA results of six spectral parameters of crabgrass observed at 3, 6, 24, 48, 72, and 120 hours after herbicide treatment with different modes of action. Each symbol represents the replication.

Figure 7.

PCA results of six spectral parameters of crabgrass by aggregating all of the data including 3 h, 6 h, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, and 120 h after treatment of herbicides with different modes of action. Each symbol represents the replication.

Figure 7.

PCA results of six spectral parameters of crabgrass by aggregating all of the data including 3 h, 6 h, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, and 120 h after treatment of herbicides with different modes of action. Each symbol represents the replication.

Table 1.

List of herbicides used for herbicide bioassay using well plates and spectral image analysis.

Table 1.

List of herbicides used for herbicide bioassay using well plates and spectral image analysis.

| Herbicide |

Mode of action |

Dose (g a.i. ha-1) |

Product name |

Formulation |

Manufacturer |

| Recommended |

Tested |

| Paraquat |

PSI inhibitor |

500 |

125 |

Gramoxone |

SL |

Farmhannong Ltd.,

Korea |

| Tiafenacil |

PPO inhibitor |

160 |

40 |

Terrad’or |

ME |

Farmhannong Ltd., Korea |

| Penoxsulam |

ALS inhibitor |

120 |

30 |

Salchodaechup |

SC |

Samgong Ltd.,

Korea |

| Isoxaflutole |

HPPD inhibitor |

200 |

50 |

Merlin |

WG |

BASF, Germany |

| Glufosinate |

GS inhibitor |

1440 |

360 |

Basta |

SL |

Bayer Crop Science, Korea, Korea |

| Glyphosate |

EPSPS inhibitor |

3690 |

922.5 |

Keunsami |

SL |

Farmhannong Ltd., Korea |

Table 2.

Summary of two-way ANOVA of each spectral parameter of crabgrass after treatment of herbicides with different modes of action.

Table 2.

Summary of two-way ANOVA of each spectral parameter of crabgrass after treatment of herbicides with different modes of action.

| Spectral parameter |

Source of variation |

F value |

P value |

P value summary |

| RGB |

mNDI |

Herbicide |

1063.089 |

<0.0001 |

**** |

| Time |

606.495 |

<0.0001 |

**** |

| Herbicide x Time |

95.708 |

<0.0001 |

**** |

| ExG |

Herbicide |

1816.526 |

<0.0001 |

**** |

| Time |

1185.414 |

<0.0001 |

**** |

| Herbicide x Time |

166.365 |

<0.0001 |

**** |

| CF |

Fv/Fm |

Herbicide |

8354.295 |

<0.0001 |

**** |

| Time |

1894.120 |

<0.0001 |

**** |

| Herbicide x Time |

341.633 |

<0.0001 |

**** |

| ΦPSII |

Herbicide |

859.989 |

<0.0001 |

**** |

| Time |

653.637 |

<0.0001 |

**** |

| Herbicide x Time |

73.445 |

<0.0001 |

**** |

| Fd/Fm |

Herbicide |

5966.657 |

<0.0001 |

**** |

| Time |

661.369 |

<0.0001 |

**** |

| Herbicide x Time |

238.078 |

<0.0001 |

**** |

| IR |

Temperature difference |

Herbicide |

11.923 |

<0.0001 |

**** |

| Time |

37.174 |

<0.0001 |

**** |

| Herbicide x Time |

15.847 |

<0.0001 |

**** |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).