Introduction

Four years have passed since the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic began in Wuhan, China, and three years have passed since the introduction of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. In Japan, COVID-19 was classified as a Category 5 infectious disease in May 2023, similar to seasonal influenza, and more than six months have passed since then.

An eighth wave of COVID-19 spread during the summer of 2023 and is expected to spread again in the winter of 2023–2024. However, this recent wave did not cause significant disruption; society returned to normal, and people's interest in COVID-19 seems to be gradually waning. We believe that the pandemic has been contained; however, free vaccination with the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine continues even after COVID-19 has been classified as a category 5 disease, which does not require special quarantine or total surveillance. Japan is the only country in the world that has promoted vaccination with up to six or seven doses of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine for the entire population.

In 2023, we reported that high titer levels of antibodies persisted for a relatively long period in patients with COVID-19 who had acquired immunity through both vaccination and post-vaccination breakthrough infection (“hybrid immunity”), raising questions regarding the need for frequent additional vaccinations [

1,

2,

3]. We identified the need for a large-scale study in Japan to examine the trends in COVID-19 antibody titers over time in post-vaccination breakthrough cases, which comprise the majority of COVID-19-infected patients in Japan.

However, no large-scale studies have been conducted, at least in Japan. In Japan, the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare and prominent experts recommended that even previously infected people receive an additional vaccination three months after infection [

4,

5]. In addition, many people in Japan, mainly older adults, had been spontaneously infected with COVID-19 in the summer of 2023 and received the sixth or seventh additional dose of the vaccine in the autumn of 2023, even though their antibody titers were high.

Herein, we describe several cases of spontaneous infection with COVID-19 after multiple vaccine doses and follow-up of antibody titers for six months to 1 year, prompting us to reconsider the significance of additional vaccination.

Results

Case presentations

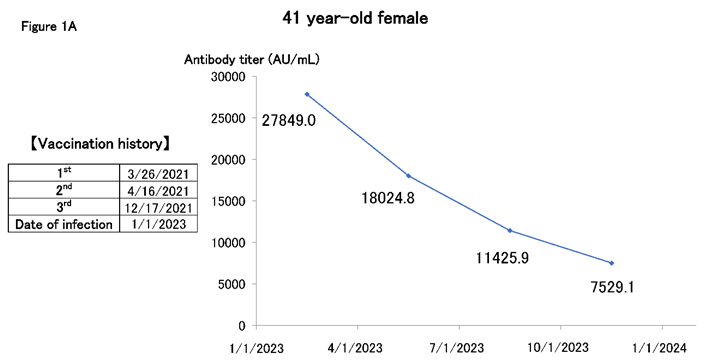

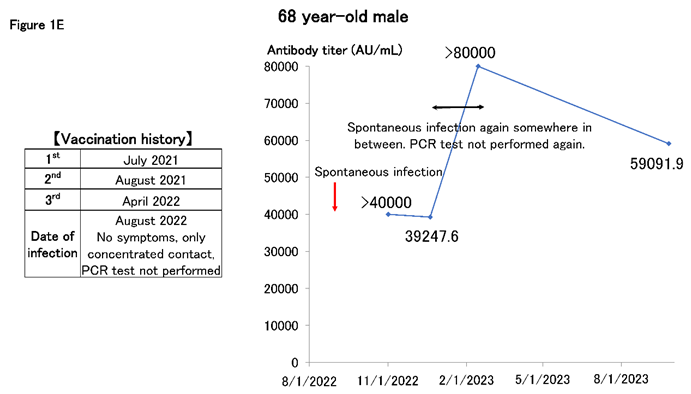

Figure 1A shows the case of a woman in her 40s working in the medical profession. The patient was vaccinated with up to three doses, but her entire family was infected in the beginning of 2023. We have been monitoring antibody titers every three months since then, and while these have declined, they have remained in the order of 10,000 for at least 6 months.

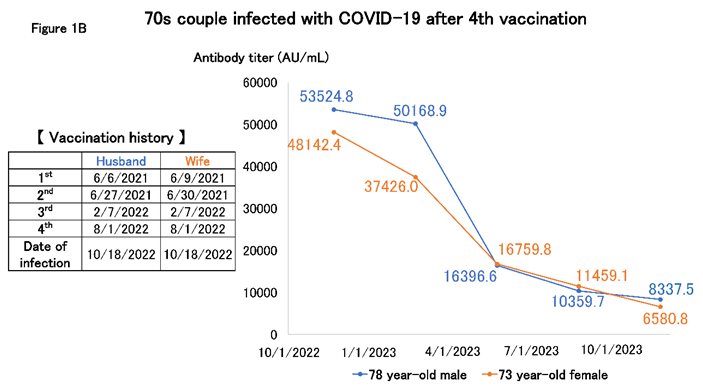

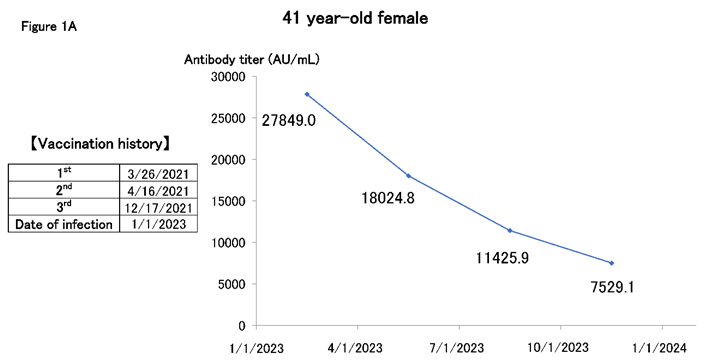

Figure 1B shows the titer of a couple in their 70s, whom the author is following as outpatients. The patients were infected in October 2022 after receiving the fourth vaccination, but they could not decide whether to be vaccinated again because of severe adverse reactions to the vaccine; therefore, they decided to have their antibody titer checked. We monitored the antibody titer every three months for a year. After infection, the antibody titer gradually declined but remained at a level of at least 10,000 units for approximately one year.

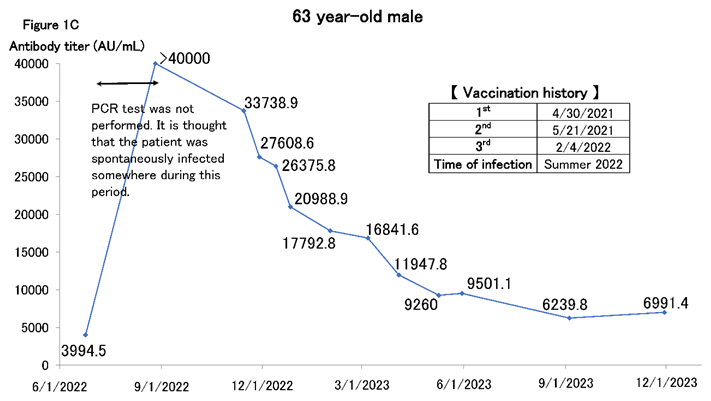

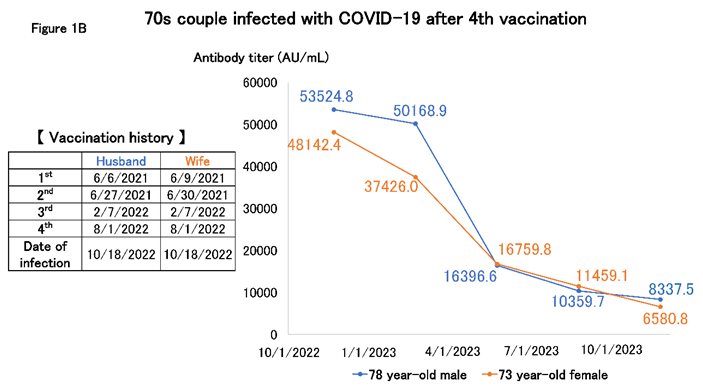

Figure 1C shows a man in his 60s thought to have been spontaneously infected in the summer of 2022, after which the antibody titer increased to >40,000 AU/mL (the upper limit of measurement at our facility at that time). We followed up on the antibody titer frequently after that. The waning of antibody titers was not linear but exhibited a shape similar to the exponential function f(X) = e-X. The decline tends to be gradual and approaches a plateau. Antibody titers decreased considerably over time. However, antibody titers only rise to a few hundred units with natural infection, and titers in the 6,000–7000 AU/mL range are approximately the same as those immediately after the second or third vaccination. Thus, antibody titers in the order of thousands are still sufficiently high, and we believe that antibody titers from hybrid immunity are prohibitively high.

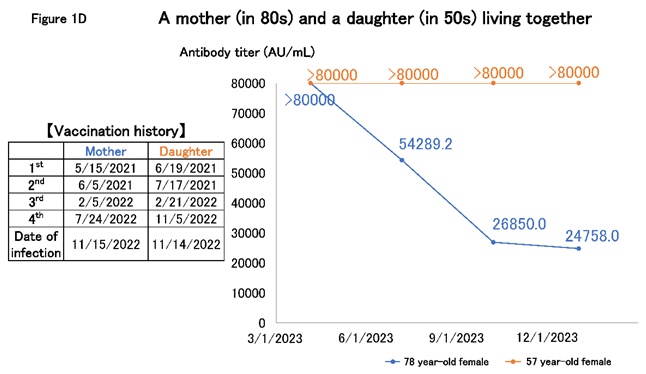

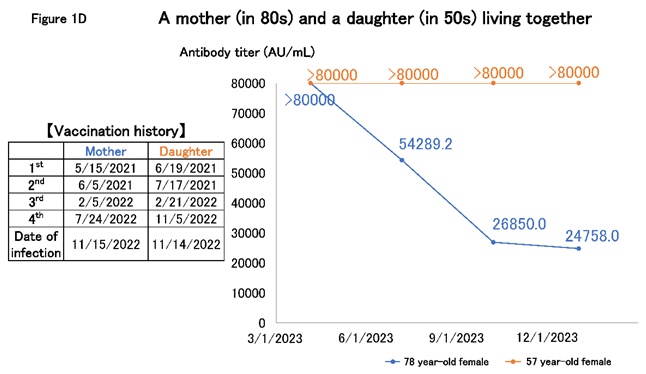

However, patients maintain high antibody titers nearly a year after infection. Figure 1D shows the case of a mother in her 80s and a daughter aged nearly 60 years who lived together. In this case, the daughter was spontaneously infected immediately after receiving the fourth dose of the vaccine in November 2022, after which the mother was infected. When we started the follow-up, approximately six months had passed since the infection. The daughter's antibodies remained >80,000 AU/mL for a long time, and the mother's antibody level was still >20,000 AU/mL, although it gradually decreased. The daughter may have been asymptomatically infected during follow-up; however, in such cases, the mother who lived with the daughter would have been infected at a high rate. Since the titer in the mother was not increased, this was considered unlikely.

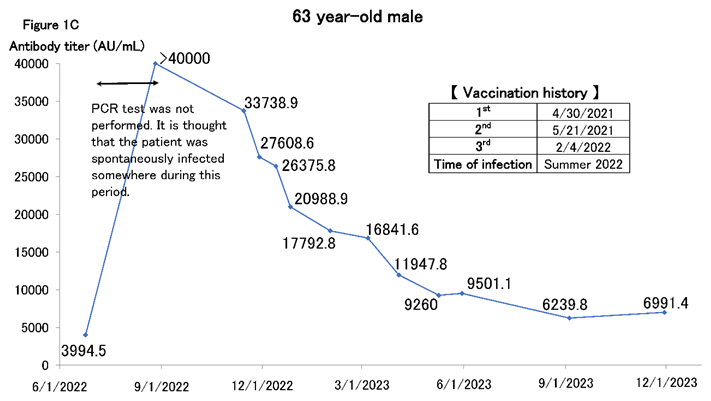

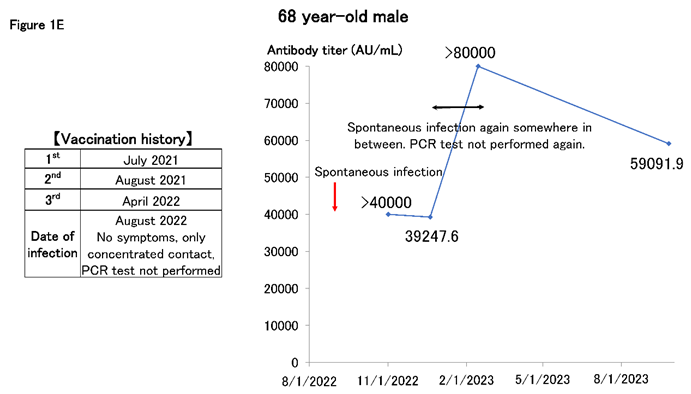

Cases of high antibody titers have occurred after repeated spontaneous infections without a PCR diagnosis. Figure 1E shows a man in his 60s who is considered to have been spontaneously infected asymptomatically in the summer of 2022 and was infected again in the winter of 2023; the antibody titer increased to >80000 AU/mL and has remained high ever since. Thus, cases exist where high antibody titers are maintained through repeated spontaneous infections without additional vaccines.

Table 1 describes the cases of three infected patients in the summer of 2023 after receiving the fifth vaccine dose. All were women in their 70s, and they wondered whether to take the sixth dose in the autumn of 2023. Several months had passed since the infection, but two cases exhibited antibody titer that had increased to >8,0000 AU/mL. We decided that additional vaccination was unnecessary, and we will continue to follow up on the antibody titer.

Discussion

Herein, we describe antibody titer trends for several cases of SARS-CoV-2 antibody that could be followed for a relatively long time after the breakthrough infection with COVID-19 in 2023. According to an analysis of blood donations, as of February 2023, 42.3% of the Japanese population had N antibodies, indicating a previous infection with COVID-19 [

6]. Currently, most of the Japanese population is thought to have a history of past COVID-19 natural infections. In early 2022, when most of the population (>70%) had received the second dose of the vaccine, the cumulative number of COVID-19-infected persons in Japan was approximately 1.7 million; by May 2023, the cumulative number of infected persons was approximately 34 million. Thus, in Japan, most infected people are thought to have become infected after the Omicron strain became the predominant SARS-CoV-2 strain after a second or more vaccinations. Therefore, Japanese individuals with N antibodies likely have hybrid immunity due to vaccination and spontaneous infection, accounting for most of the population. Certain of them may have been naturally infected six months to a year or more ago, and their antibody titers may have declined; however, many of those with hybrid immunity are still considered to have high antibody titers.

This study had certain limitations. This study only described a few cases, and discussing the advantages and disadvantages of additional vaccinations on this basis alone could be argued to be inappropriate. Furthermore, although neutralizing antibodies can be measured instead of IgG antibodies against the RBD or cellular immunity evaluated, we did not consider those aspects of immunity in this study. A large multicenter study should examine the increase in SARS-CoV-2 antibody titers and the long-term follow-up of hybrid immunity after a breakthrough infection to answer these questions.

Additional predisposing factors in antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 have been identified. Differences in the degree of SARS-CoV-2 antibody acquisition and maintenance after vaccination have been reported, and host factors such as age, sex, comorbidities, and genetic polymorphisms have been shown to be involved [

7]. Furthermore, the higher the IgG and neutralizing antibody titers, the stronger the protection against infection with the Omicron variant and the stronger the symptomatic disease [

8]. Based on these studies, we should consider what specific predisposing factors in the Japanese population would result in higher SARS-CoV-2 antibody titers and what level of SARS-CoV-2 antibody titer would effectively prevent the onset of disease or severe disease.

In the United States, a robust study of US Military Health System beneficiaries was conducted to clarify the predictors of vaccine immunogenicity. This study showed that antibody titers did not decrease six months after COVID-19 infection when hybrid immunization was acquired compared with immunization via vaccine or infection alone [

9]. The authors stated that the antibody titer remained high for at least six months after hybrid immunization. This may help inform vaccination timing strategies.

Changes over time in antibody titers and cellular immunity should be tracked. Unlike antibodies, memory T cells are considered to be long-lived and remain in sufficient numbers to suppress severe disease even eight months after vaccination [

10].

An immunology expert prescribed in an online article, "Immune memory from vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 infection is maintained for at least one year and is re-boosted by actual infection and repeat vaccination. No immunological reason is observed to vaccinate more frequently, such as every three months. Rather, immunologically speaking, frequent administration of vaccines carries a higher risk of adverse reactions from adjuvants and diseases from antibodies [

11]."

Infectious disease experts have appeared on various media and social networking sites to encourage the public to receive the COVID-19 vaccine [

12,

13,

14]. However, many citizens did not feel there was any scientific basis for what the infectious disease experts had said, and many believed there was no coherence.

Why have infectious disease specialists in Japan lost the trust of the public? The following symbolic episodes occurred in Japan as an example of this discordance. However, they were not directly related to the COVID-19 vaccine. At one time in Japan, people were recommended to remove their masks only when they brought food to their mouths during meals and wear masks at other times, especially during conversations and even during meals, the so-called "masked meal [

15]." However, additional opinions stated that frequently bringing one’s hands to one’s mouth during a meal might increase the risk of infection [

16]. Dr. Shigeru Omi, the Chairman of the Subcommittee on Countermeasures against COVID-19, personally demonstrated and encouraged a "masked meal." This practice was ridiculed as "Omi’s way of eating.” By the end of 2022, prominent infectious disease experts posted a video on YouTube recommending this "masked meal” [

17]. However, a professional baseball player had a negative view of the actions and words of these infectious disease experts [

18]. We will not discuss here whether "masked meal" effectively prevent infections. However, we consider that the topic of the "masked meal" symbolizes the considerable gap between the infectious disease specialists who recommended the "masked meal" and the general public's perception.

In October 2023, a remarkable article was published by a group of prominent researchers who stated that the COVID-19 vaccine reduced both infections and deaths in Japan from February to November 2021 by >90% and that without the vaccine, the number of COVID-19 infections and deaths could have reached approximately 63.3 million and 360,000, respectively [

19]. Although we do not discuss this article now, many citizens do not believe the COVID-19 vaccination was effective, and a video questioning this article was immediately uploaded to YouTube [

20,

21].

Infectious disease experts have announced the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine in preventing the onset and severity of the disease and have strongly recommended frequent additional vaccinations because the antibody titer decreases over time after vaccination. However, many public members no longer believe the COVID-19 vaccine is effective. Many have received free vaccination coupons, but for how long they should continue to be vaccinated remains unclear. Many question the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine and whether the entire population, including healthy young people, should continue to be vaccinated. Again, a gap between infectious disease specialists and the general public appears to be present in the perception of the COVID-19 vaccination.

Therefore, rather than continuing to promote frequent vaccination of the entire population, a clear and scientific presentation of the positive reasons for COVID-19 vaccination in Japan and the target of vaccination in the form of a target antibody titer would be valuable. This will help restore public confidence in infectious disease specialists and healthcare professionals.

Even if the antibody titer remains high after infection with a conventional strain, this may not be effective in protecting against the currently prevalent mutant strains. If a person has been infected recently, the virus that infects them is considered more up-to-date than the current vaccine, and rushing to vaccinate them may not be worthwhile. We believe a flexible response that considers cost and risk benefits is required.

SARS-CoV-2 antibody titers raised by hybrid immunity are robust, although they tend to decline over time. Individual differences exist but do not decrease completely within at least 3 months. From 2024, vaccination will be optional once a year for older patients. However, at least for those already infected, it may not be necessary once a year. A multicenter large-scale study should be conducted on the changes in antibody titers after COVID-19 infection. Therefore, the significance of routine vaccinations should be considered. Since Japan has been conducting numerous unparalleled vaccinations worldwide, meaningful research could be subsequently performed on antibody titer trends.