Submitted:

03 January 2024

Posted:

04 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.2. Data extraction

2.3. Data selection & Inclusion Criteria

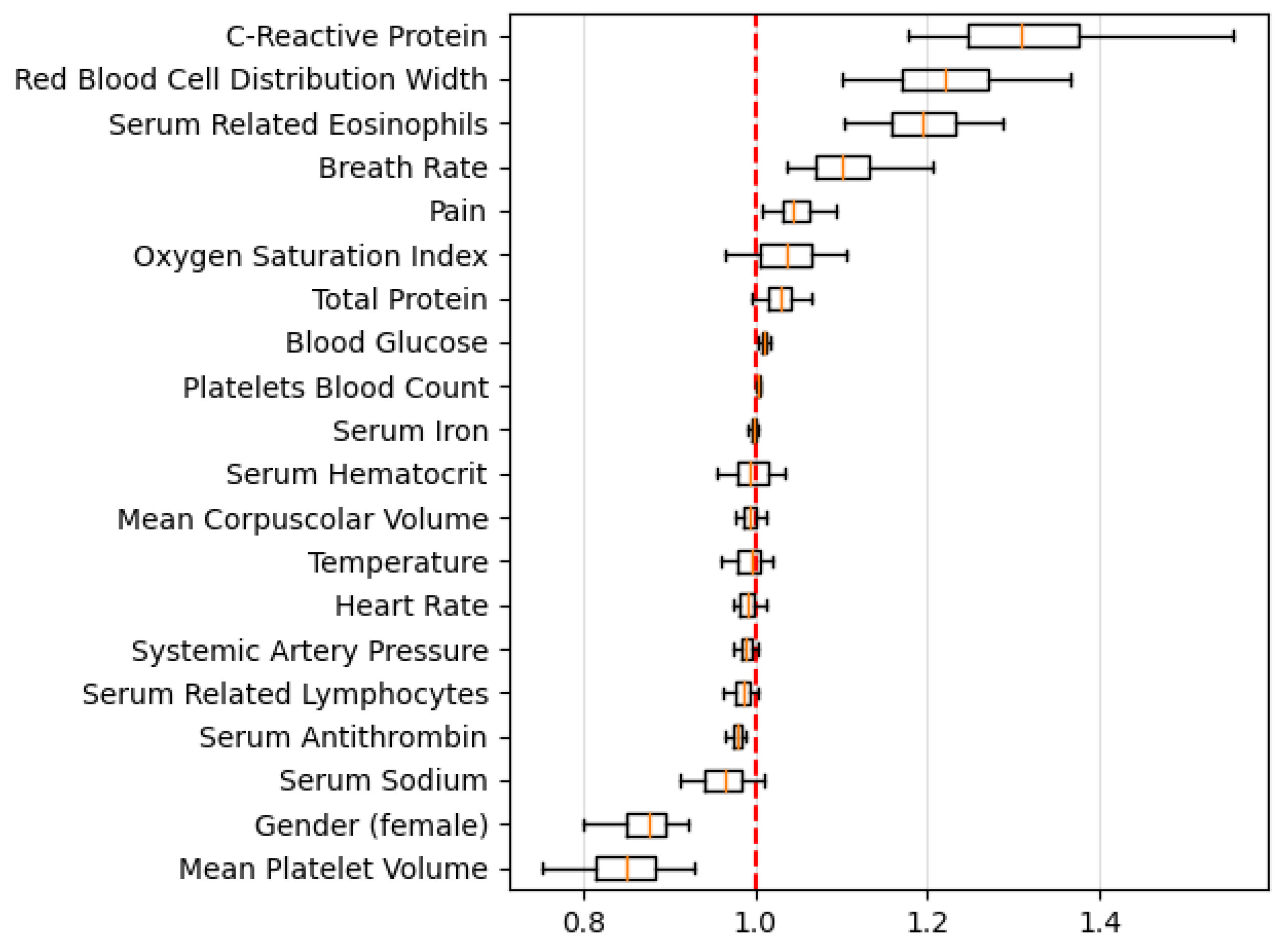

2.4. Feature selection

2.5. Analytics

- Missing values imputer: missing values are imputed with the mean in the overall population.

- Feature scaler: The features are scaled using a minimum and maximum scaler.

- Classification model: Logistic Regression.

3. Results

3.1. Dataset

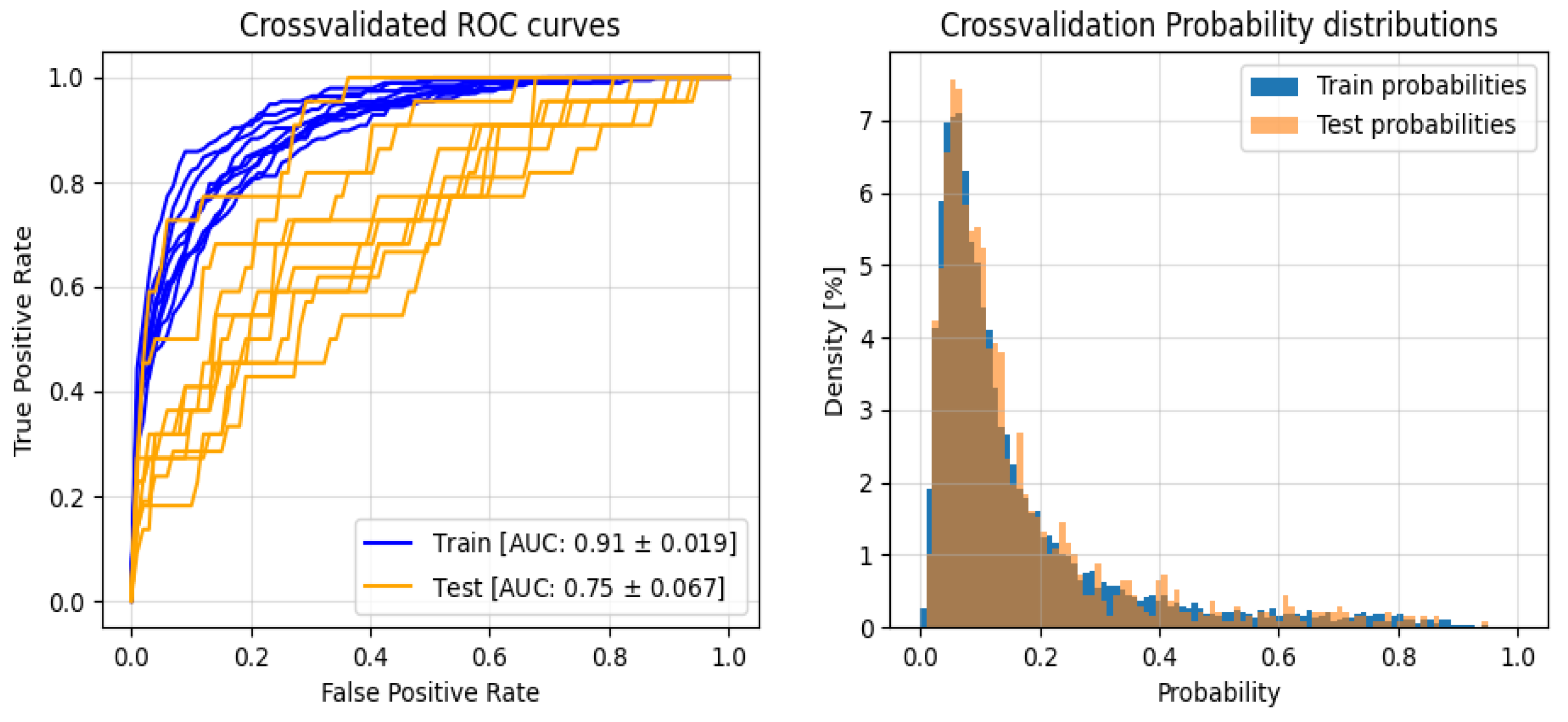

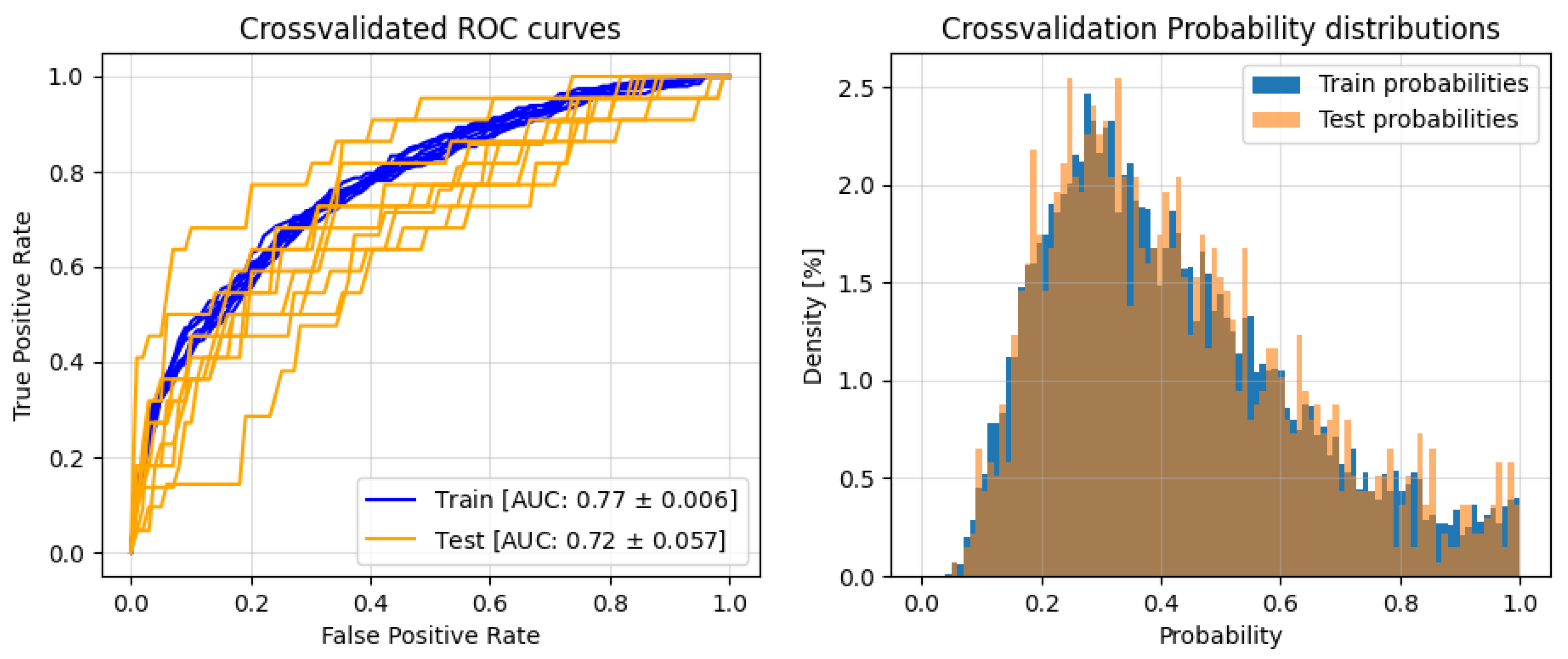

3.2. Classification

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Test | Train | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| F1 | 0,785 ± 0,143 | 0,454 ± 0,109 | 0,893 ± 0,028 | 0,622 ± 0,059 |

| Precision | 0,291 ± 0,032 | 0,369 ± 0,148 | 0,963 ± 0,005 | 0,501 ± 0,076 |

| Recall | 0,706 ± 0,202 | 0,699 ± 0,184 | 0,833 ± 0,048 | 0,835 ± 0,029 |

References

- Volpe, L.; Indelli, P.F.; Latella, L.; Polli, P.; Yakupoglu, J.; Marcucci, M. Periprosthetic Joint Infections: A Clinical Practice Algorithm. Joint 2014, 2, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S.; Ong, K.; Lau, E.; Mowat, F.; Halpern, M. Projections of Primary and Revision Hip and Knee Arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007, 89, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torre, M.; Romanini, E.; Zanoli, G.; Carrani, E.; Luzi, I.; Leone, L.; Bellino, S. Monitoring Outcome of Joint Arthroplasty in Italy: Implementation of the National Registry. Joints 2017, 5, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izakovicova, P.; Borens, O.; Trampuz, A. Periprosthetic Joint Infection: Current Concepts and Outlook. EFORT Open Reviews 2019, 4, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palan, J.; Nolan, C.; Sarantos, K.; Westerman, R.; King, R.; Foguet, P. Culture-Negative Periprosthetic Joint Infections. EFORT Open Reviews 2019, 4, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talsma, D.T.; Ploegmakers, J.J.W.; Jutte, P.C.; Kampinga, G.; Wouthuyzen-Bakker, M. Time to Positivity of Acute and Chronic Periprosthetic Joint Infection Cultures. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 2021, 99, 115178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evangelopoulos, D.S.; Stathopoulos, I.P.; Morassi, G.P.; Koufos, S.; Albarni, A.; Karampinas, P.K.; Stylianakis, A.; Kohl, S.; Pneumaticos, S.; Vlamis, J. Sonication: A Valuable Technique for Diagnosis and Treatment of Periprosthetic Joint Infections. The Scientific World Journal 2013, 2013, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, S.; Wyles, C.C.; Osmon, D.R.; Carvour, M.L.; Sagheb, E.; Ramazanian, T.; Kremers, W.K.; Lewallen, D.G.; Berry, D.J.; Sohn, S.; et al. Automated Detection of Periprosthetic Joint Infections and Data Elements Using Natural Language Processing. The Journal of Arthroplasty 2021, 36, 688–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bingham, J.S.; Salib, C.G.; McQuivey, K.; Temkit, M.; Spangehl, M.J. An Evidence-Based Clinical Prediction Algorithm for the Musculoskeletal Infection Society Minor Criteria. The Journal of Arthroplasty 2018, 33, 2993–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deo, R.C. Machine Learning in Medicine. Circulation 2015, 132, 1920–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, Y.Y.; Chan, P.K.; Chan, V.W.K.; Cheung, A.; Luk, M.H.; Cheung, M.H.; Fu, H.; Chiu, K.Y. Application of Machine Learning in the Prevention of Periprosthetic Joint Infection Following Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review. Arthroplasty 2023, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. MACHINE LEARNING IN PYTHON.

- Pollard, T.J.; Johnson, A.E.W.; Raffa, J.D.; Mark, R.G. Tableone: An Open Source Python Package for Producing Summary Statistics for Research Papers. JAMIA Open 2018, 1, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedair, H.; Ting, N.; Jacovides, C.; Saxena, A.; Moric, M.; Parvizi, J.; Della Valle, C.J. The Mark Coventry Award: Diagnosis of Early Postoperative TKA Infection Using Synovial Fluid Analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011, 469, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Wang, Q.; Kuo, F.-C.; Goswami, K.; Tan, T.L.; Parvizi, J. The Presence of Sinus Tract Adversely Affects the Outcome of Treatment of Periprosthetic Joint Infections. J Arthroplasty 2019, 34, 1227–1232.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigmund, I.K.; McNally, M.A.; Luger, M.; Böhler, C.; Windhager, R.; Sulzbacher, I. Diagnostic Accuracy of Neutrophil Counts in Histopathological Tissue Analysis in Periprosthetic Joint Infection Using the ICM, IDSA, and EBJIS Criteria. Bone Joint Res 2021, 10, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, I.; Klemt, C.; Robinson, M.G.; Esposito, J.G.; Uzosike, A.C.; Kwon, Y.-M. The Use of Artificial Neural Networks for the Prediction of Surgical Site Infection Following TKA. J Knee Surg 2023, 36, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klemt, C.; Laurencin, S.; Uzosike, A.C.; Burns, J.C.; Costales, T.G.; Yeo, I.; Habibi, Y.; Kwon, Y.-M. Machine Learning Models Accurately Predict Recurrent Infection Following Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty for Periprosthetic Joint Infection. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2022, 30, 2582–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.; Hu, H.; Li, J.; Li, M.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, G.; Ni, M. A Preliminary Study on the Application of Deep Learning Methods Based on Convolutional Network to the Pathological Diagnosis of PJI. Arthroplasty 2022, 4, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Cheligeer, C.; Southern, D.A.; Martin, E.A.; Xu, Y.; Leal, J.; Ellison, J.; Bush, K.; Williamson, T.; Quan, H.; et al. Development of Machine Learning Models for the Detection of Surgical Site Infections Following Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: A Multicenter Cohort Study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2023, 12, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc., 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

| Features | Missing Value | Aseptic Cohort | Infected Cohort | Overall | P-value |

| Patients (number) | 1141 | 219 | 1360 | ||

| Pain | 1 (0.10%) | 1.0 [0.53 1.05] | 1.0 [0.87 1.10] | 1.0 [0.57 1.07] | <0.001 |

| Breath Rate (bpm) | 69 (5.10%) | 15.57 [15.09 16.0] | 15.68 [15.24 16.25] | 15.6 [15.13 16.01] | 0.01 |

| Heart Rate (rpm) | 1 (0.10%) | 74.18 [69.55 78.85] | 74.92 [69.77 79.73] | 74.29 [69.56 78.98] | 0.46 |

| Systemic Artery Pressure (mmHg) | 1 (0.10%) | 119.25 [112.79 126.27] | 119.22 [113.51 127.56] | 119.23 [112.8 126.5] | 0.722 |

| Oxygen Saturation Index (%) | 1 (0.10%) | 98.15 [97.54 98.64] | 98.1 [97.52 98.52] | 98.14 [97.54 98.61] | 0.211 |

| Temperature °C | 1 (0.10%) | 36.42 [36.29 36.57] | 36.39 [36.28 36.49] | 36.42 [36.29 36.57] | 0.02 |

| Serum Antithrombin (%) | 45 (3.30%) | 100.0 [92.0 108.0] | 96.0 [89.0 103.0] | 99.0 [91.0 107.0] | <0.001 |

| Serum Related Eosinophils (%) | 0 (0.00%) | 2.0 [1.0 3.0] | 2.0 [2.0 4.0] | 2.0 [1.0 3.0] | 0.002 |

| Serum Hematocrit (%) | 0 (0.00%) | 42.0 [39.3 44.5] | 40.6 [38.3 43.65] | 41.8 [39.1 44.4] | <0.001 |

| Serum Related Lymphocytes (%) | 0 (0.00%) | 28.0 [23.0 34.0] | 26.0 [20.5 31.0] | 28.0 [23.0 33.0] | <0.001 |

| Mean Corpuscolar Volume (fL) | 0 (0.00%) | 89.7 [86.5 92.9] | 87.6 [84.35 91.3] | 89.4 [86.14 92.7] | <0.001 |

| Mean Platelet Volume (fL) | 0 (0.00%) | 8.9 [8.2 9.6] | 8.5 [7.8 9.0] | 8.8 [8.1 9.5] | <0.001 |

| Serum Ironemia (µg/dL) | 43 (3.20%) | 79.0 [62.0 100.0] | 62.0 [43.5 85.5] | 76.0 [58.0 98.0] | <0.001 |

| Serum Glucose (mg/dL) | 203 (14.90%) | 96.0 [89.0 103.0] | 98.0 [92.0 108.0] | 96.0 [89.0 104.0] | 0.004 |

| C-Reactive Protein (mg/dL) | 114 (8.40%) | 0.3 [0.15 0.59] | 0.64 [0.32 1.935] | 0.34 [0.17 0.71] | <0.001 |

| Total Protein (g/dL) | 0 (0.00%) | 11.2 [10.7 11.9] | 11.9 [11.2 12.6] | 11.3 [10.8 12.0] | <0.001 |

| Serum Sodium (mmol/L) | 201 (14.80%) | 142.0 [141.0 143.0] | 142.0 [140.0 143.0] | 142.0 [141.0 143.0] | 0.017 |

| Gender (Female) | 0 (0.00%) | 691 (60.6%) | 94 (42.9%) | 785 (57.7%) | <0.001 |

| Red Blood Cell Distribution Width (%) | 0 (0.00%) | 14.0 [13.4 14.8] | 14.7 [13.9 15.98] | 14.1 [13.5 15.0] | <0.001 |

| Platelets Blood Count (10^3/mm^3) | 0 (0.00%) | 231.0 [196.0 272.0] | 254.0 [214.0 308.5] | 234.0 [197.0 278.0] | <0.001 |

| Test | Train | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| F1 | 0.824 ± 0.062 | 0.427 ± 0.067 | 0.815 ± 0.014 | 0.444 ± 0.011 |

| Precision | 0.911 ± 0.023 | 0.349 ± 0.092 | 0.924 ± 0.003 | 0.329 ± 0.014 |

| Recall | 0.761 ± 0.111 | 0.603 ± 0.143 | 0.729± 0.024 | 0.688± 0.024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).