1. Introduction

Despite the endpoint of caries excavation is today controversially discussed in order to protect pulp vitality[

1,

2,

3], successful endodontic treatment is still a key factor in conservative dentistry when it comes to irreversible pulp inflammation[

4,

5]. Unfortunately, today a significant shift towards systematic reviews is clearly visible in the dental literature, involving the problem that in many cases collected data are more frequently cited than original research[

6,

7]. This inflation of literature papers may tempt young researchers to head towards their computer instead of going to lab or operatory in order to produce real data[

8]. Additionally, in many countries prospective clinical trials are more and more impeded by sprawling bureaucracy as well as inadequate ethical concerns and burdens[

9,

10]. All of these factors make clinical research more and more expensive, less attractive for the dental industry as sponsor, and finally less accomplishable in general[

10].

It is well-known that pulp treatment is strongly correlated with patients’ quality of life[

11,

12,

13], because simple tooth preservation is a major outcome being considered. However, missing outcome assessment leads to a weak scientific basis for clinical decision-making[

14]. Therefore, more clinical research in endodontics has been repeatedly requested[

15]. Beside randomized trials as gold standard, also prospective cohort studies [

8,

15], have been described promising[

15]. Furthermore, inclusion of several variables combined with multivariate statistics are fundamental prerequisites to reduce the risk of confounding bias[

16]. On the other hand, large-scale prospective cohort studies involving multiple variables are extremely time-consuming and thus expensive[

8,

15], and it is well-known from these studies that when after many years of recall assessments substantial results are available, the respective materials that had been used may not be on the market anymore[

17]. These are the main reasons why very few endodontic prospective long-term trials have been published[

17,

18,

19], additionally suffering relatively short follow-up periods. Real long-term data are therefore desired for both patient information and public health and insurance issues [

4,

15].

However, beside endodontic treatment alone, postendodontic restoration quality has been discussed to be an important factor for long-term success as well[

20]. It is not decisive, whether quality of endodontic treatment or postendodontic restoration is more important[

20] instead of focusing on both factors being extremely clinically relevant issues in this topic[

21]. Nevertheless, when dealing with that old data like in the present investigation, it is interesting that almost all facts being relevant today have not been investigated before the present endodontic treatments have been made. This means that today’s evidence about post-endodontic restorations[

3,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25] has been not available in the 1980’s when metal posts and screws were clinical standard as well as amalgam restorations. When direct resin composite restorations were used, dentin was covered with a thick cement lining and moreover, dentin bonding was not established. This means that in every single adhesive approach, only enamel margins were really bonded.

Therefore, the present study retrospectively evaluated the 40-years outcome of endodontic treatment of 174 patients and 243 teeth having been endodontically treated by two different dentists in the 1970’s and 80’s.

2. Materials and Methods

Endodontic treatments in the present retrospective study were performed by two experienced dental practitioners (P1: Albrecht, P2: Behrens) in two different private dental practices in Kiel, Germany. P1 treated 73 patients with 107 teeth, P2 101 patients with 138 teeth. The study protocol was approved by a local ethics committee (University of _________; Ref. No. 474/18) and all patients provided informed consent prior to treatment start. All endodontic treatments were performed from 1969 to 1993. Evaluations were carried out by the two practitioners until 2018. The paper was written in consideration of STROBE guidelines. Patients were included if a primary or secondary endodontic treatment was indicated and possibility of post-operative restoration was available. Teeth with any loosening, root resorptions or root fractures were excluded. Endodontic treatment procedures based on contemporary methods of the respective period. During vital exstirpation, root canals were prepared with hedstrom files, rinsed with H2O2, dried with paper points, and filled with gutta percha and sealer using lateral compaction. Prior to preparing root canals with endodontic instruments, patients were clinically and radiographically examined. Clinical examination included evaluation of tooth position, pre-existing restoration, periodontal status, pain symptoms, vitality status, and sensitivity to percussion. Presence and depth of caries as well as presence and size of apical radiolucency were evaluated radiographically. Working length was determined radiographically. Finally, a radiograph was taken to check quality/homogeneity and distance of the root canal filling to the individual apex. 3% sodium hypochlorite was used as disinfectant and if the treatment required several sessions, intracanal medication (ChKM/Speiko, Calxyl/OCO) were applied. Subsequent to root canal obturation, all teeth were either restored with a new restoration (amalgam, resin composite, glass-ionomer cement), or by recementation of pre-existing prosthetic restorations, or by manufacturing of new indirect prosthetic restorations. Cast metal posts were inserted when significant loss (>50%) of coronal tooth structure required additional intracanal retention. In cases of failed or lost post-operative restorations, endodontically treated teeth were newly restored at different times in the following years.

In the period after completion of endodontic and restorative treatments, all patients joined an individual monitoring for clinical reevaluation including subsequent control radiographs. Depending on the associated findings, endodontically treated teeth received periodontal therapy, endodontic re-treatment, or dental apectomy. Both operators screened 243 teeth treated in the period from 1969 until 1993. Pre-, intra- and post-operative data and possible prognostic factors with corresponding data were collected in Excel sheets (

Table 1,2). The primary outcome tooth survival was achieved when the endodontically treated tooth was in situ, painless and in full function[

19]. The secondary outcome was to investigate the impact of potential prognostic factors on survival rates.

Statistical analysis of tooth survival was performed by Kaplan-Meier survival test considering the date of tooth extraction. Reasons for extraction were periodontal disease, root/crown fracture, untreatable caries and endodontic inflammation. Tooth-related variables to evaluate possible prognostic factors were compared by log-rank-, Mantel-Haenszel and Wilcoxon-test. Prism/GraphPad (Insight Partners, Praphpad Holdings, LLC, Los Angeles, USA) was used for statistical analysis and the level of significance was set at p≤0,05.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Outcome Practitioner A

3.1.1. Overall Tooth survival

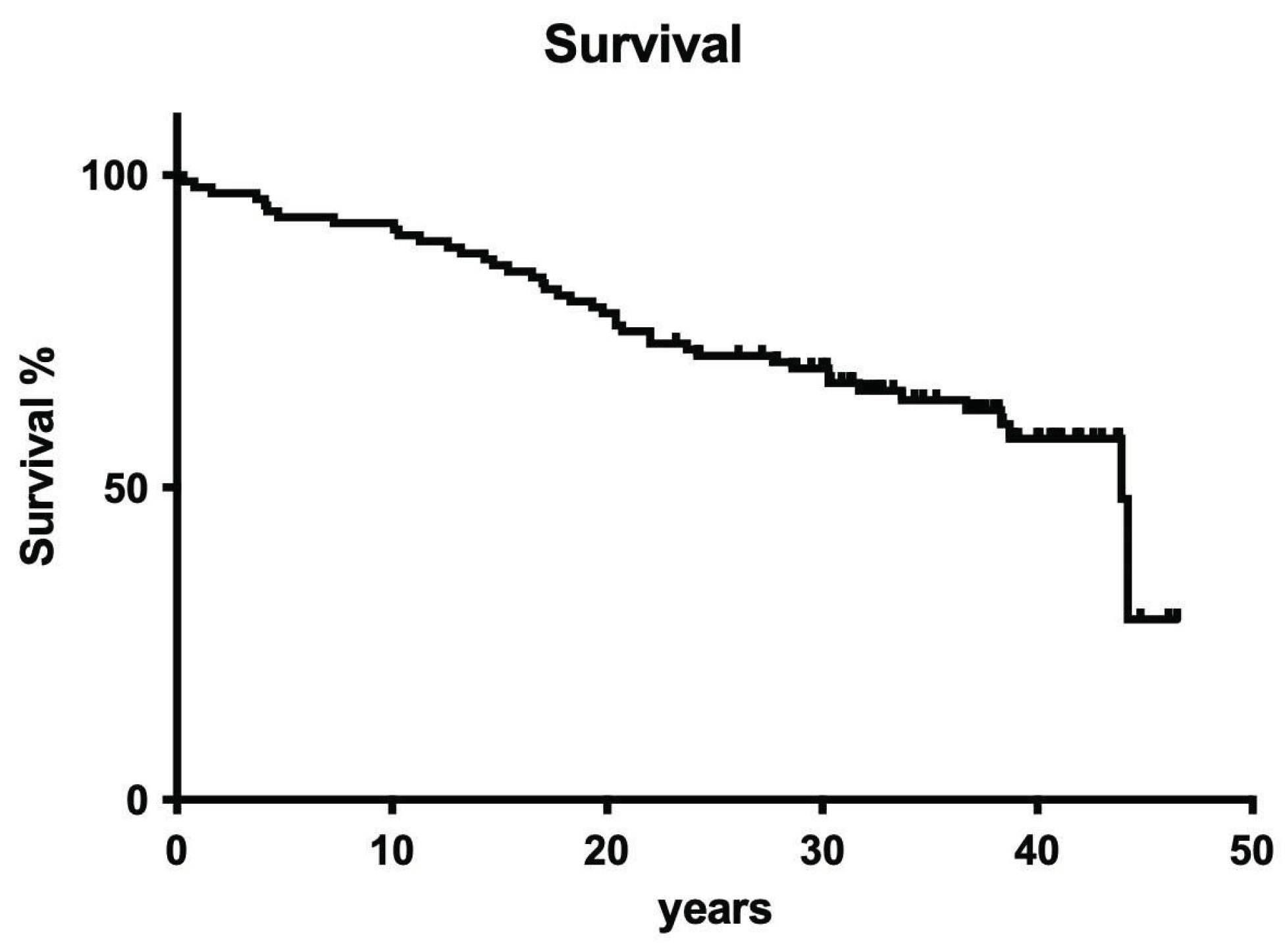

Overall tooth loss after 40 years was 43.9%. The observed extraction rate was homogeneously distributed over the complete observation period, so no cumulative incidents like in many other clinical trials occurred (

Figure 1).

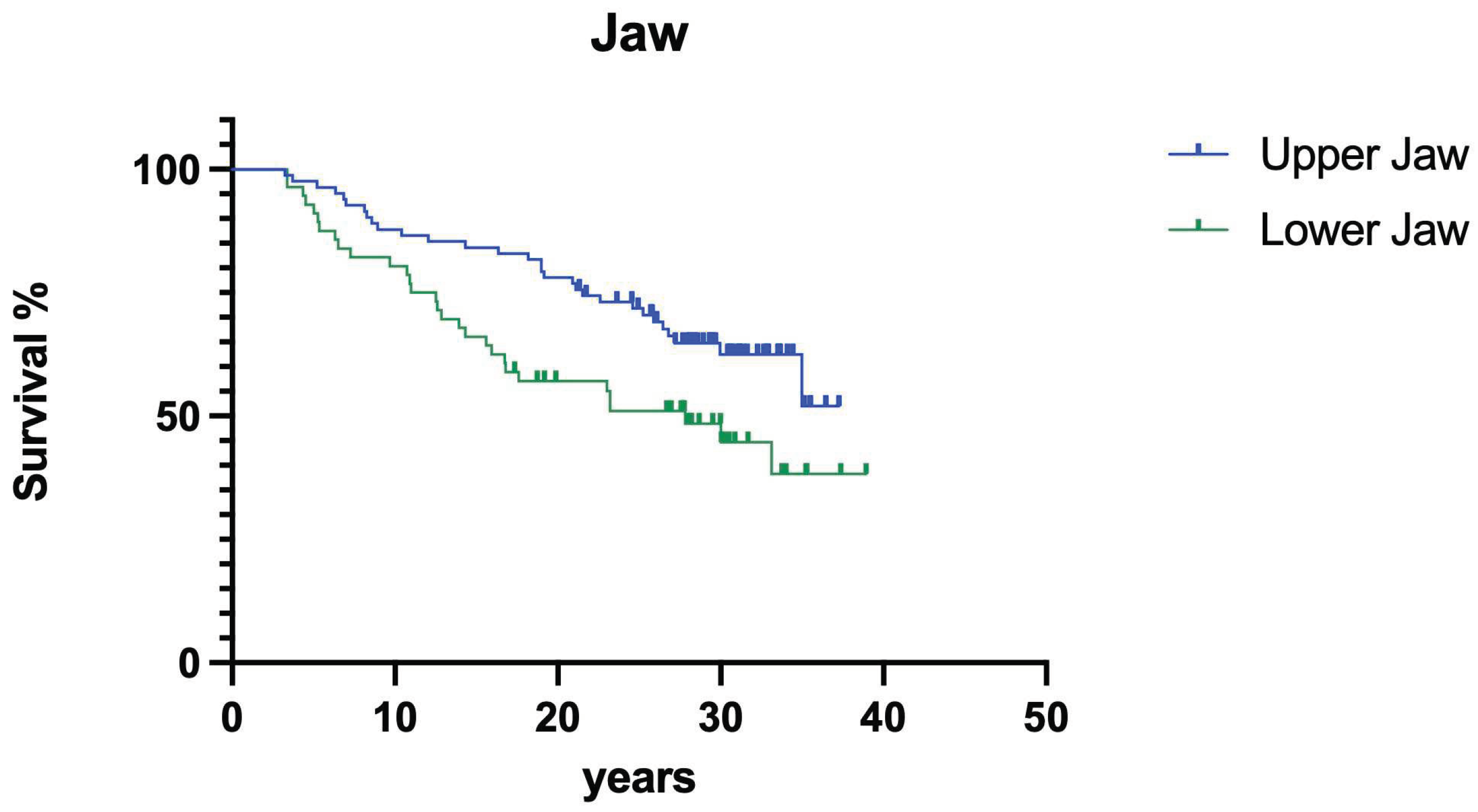

3.1.2. Influence of jaw

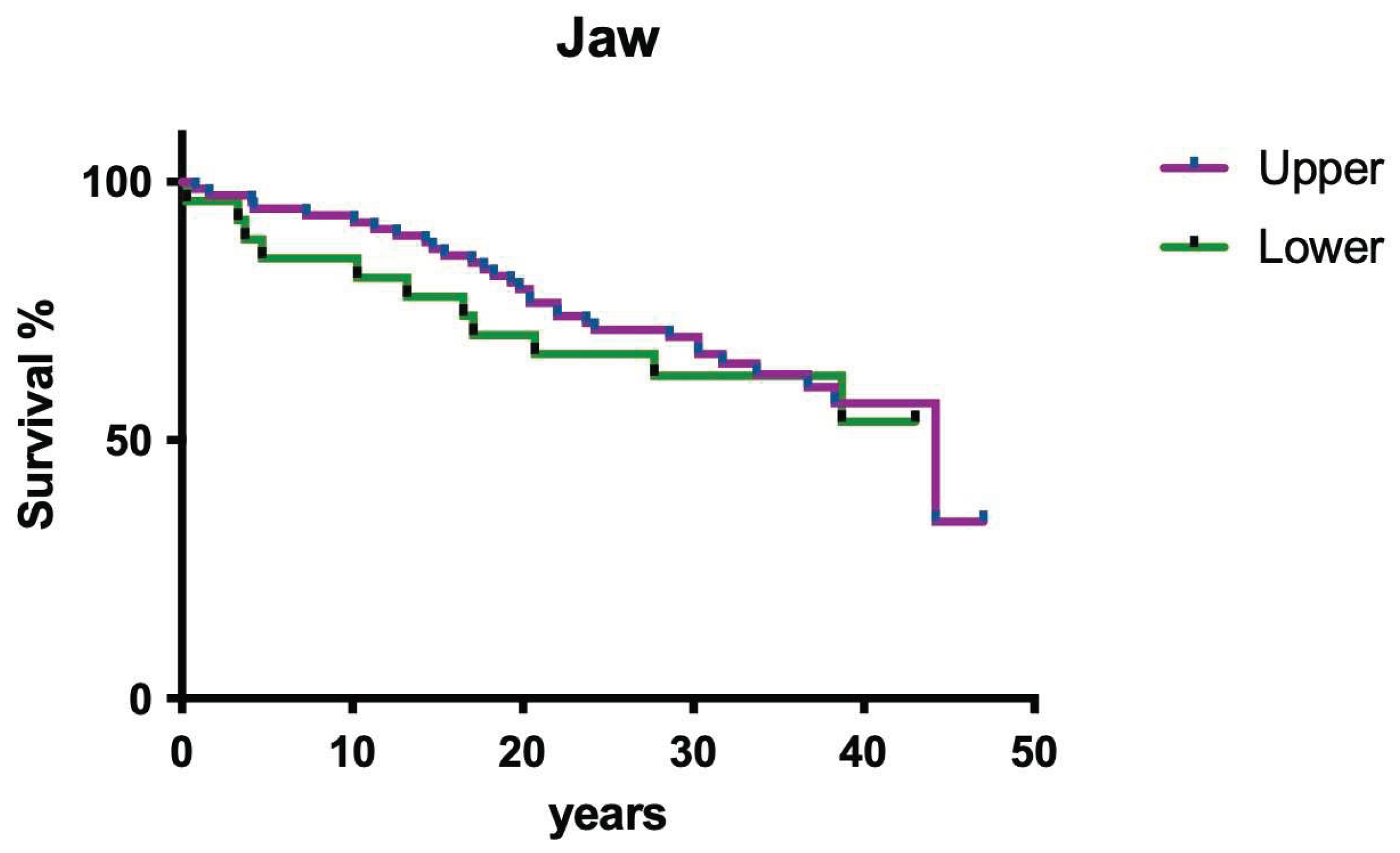

Jaw position had no significant impact on overall survival (

Figure 2; p>0.05).

3.1.3. Influence of tooth position

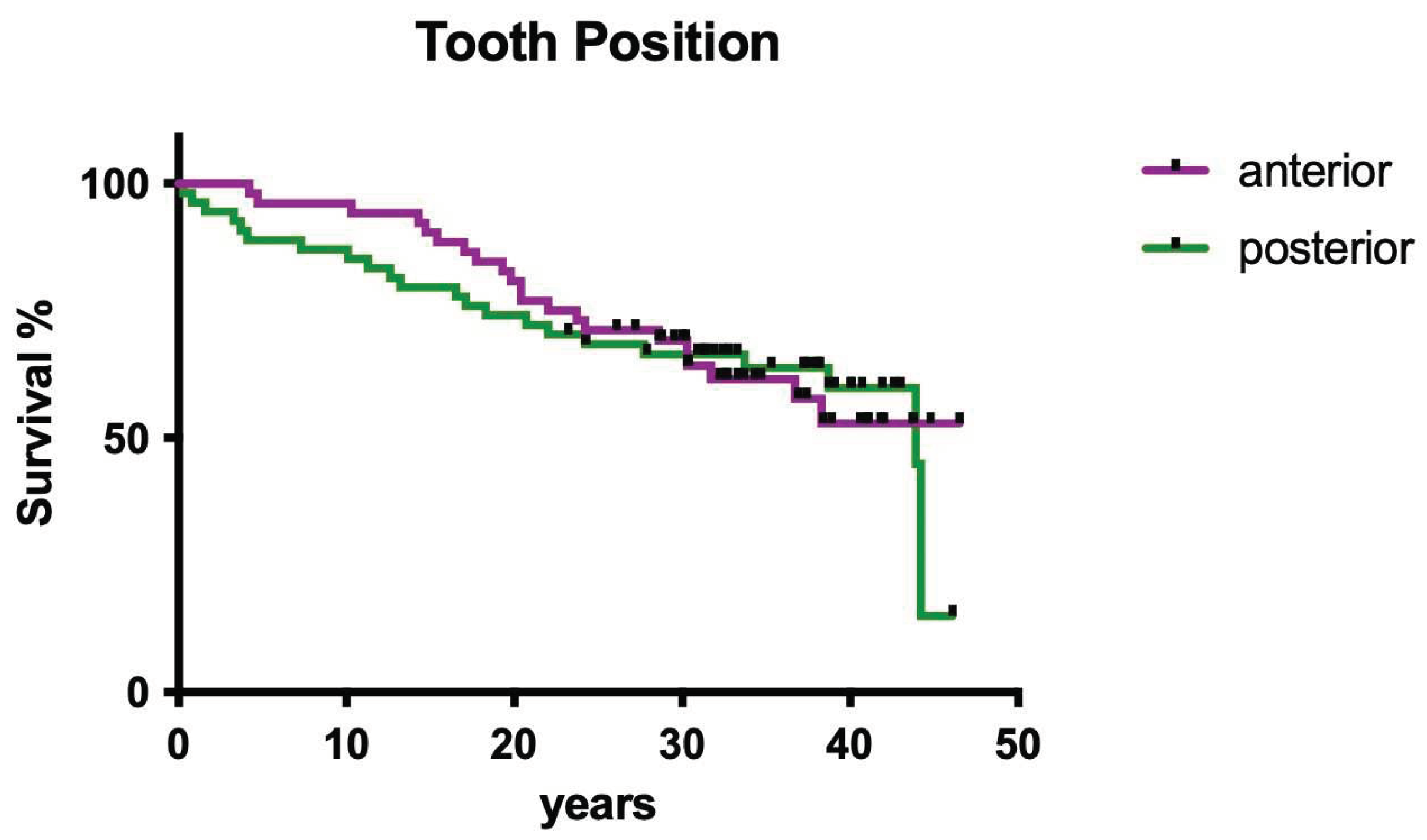

Tooth position (i.e. anterior vs. posterior) had no significant influence on overall survival (

Figure 3; p>0.05).

3.1.4. Influence of root canal infection

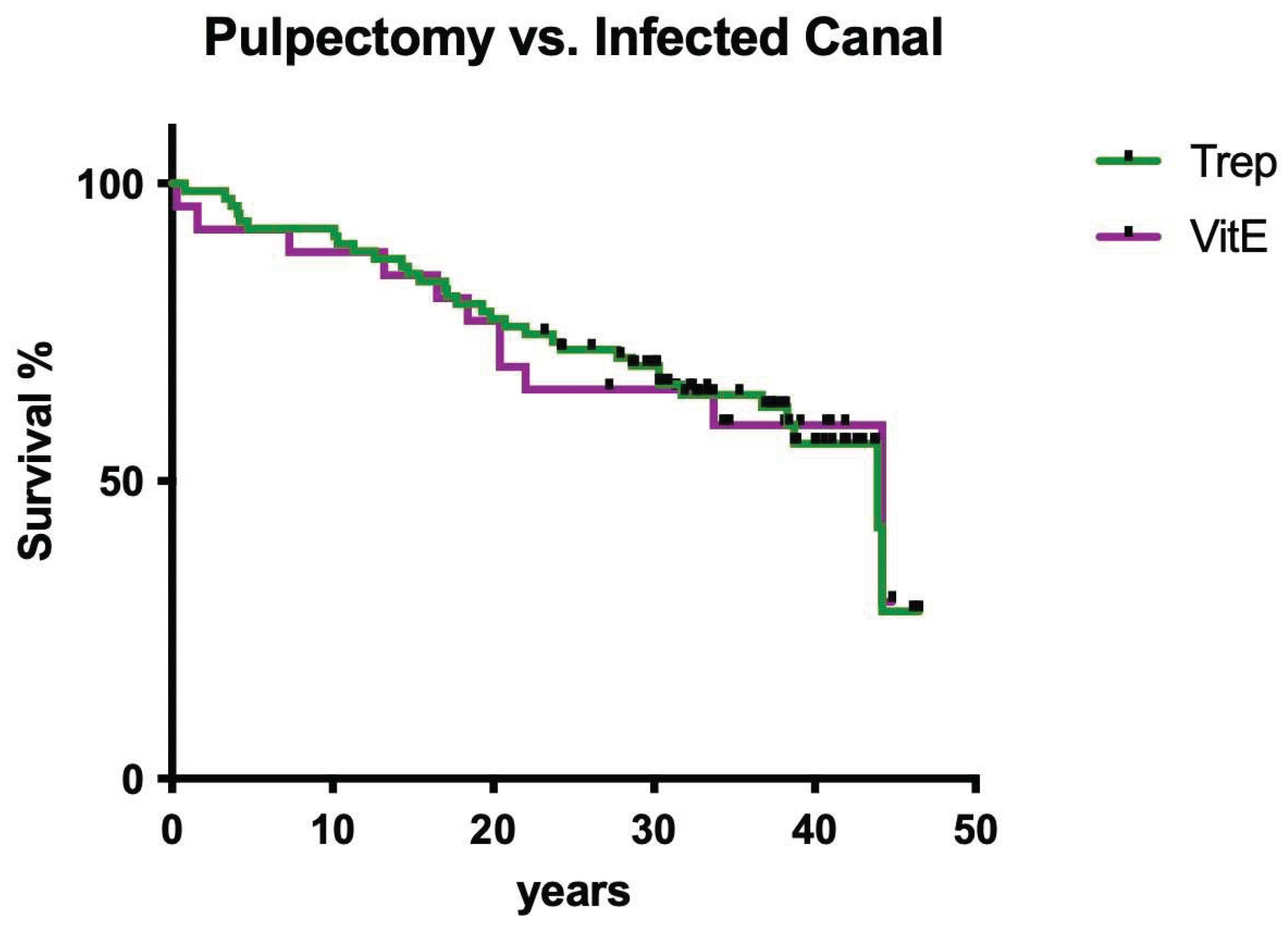

The infection status (pulpectomy vs. infected canal) had no significant influence on overall survival (

Figure 4; p>0.05).

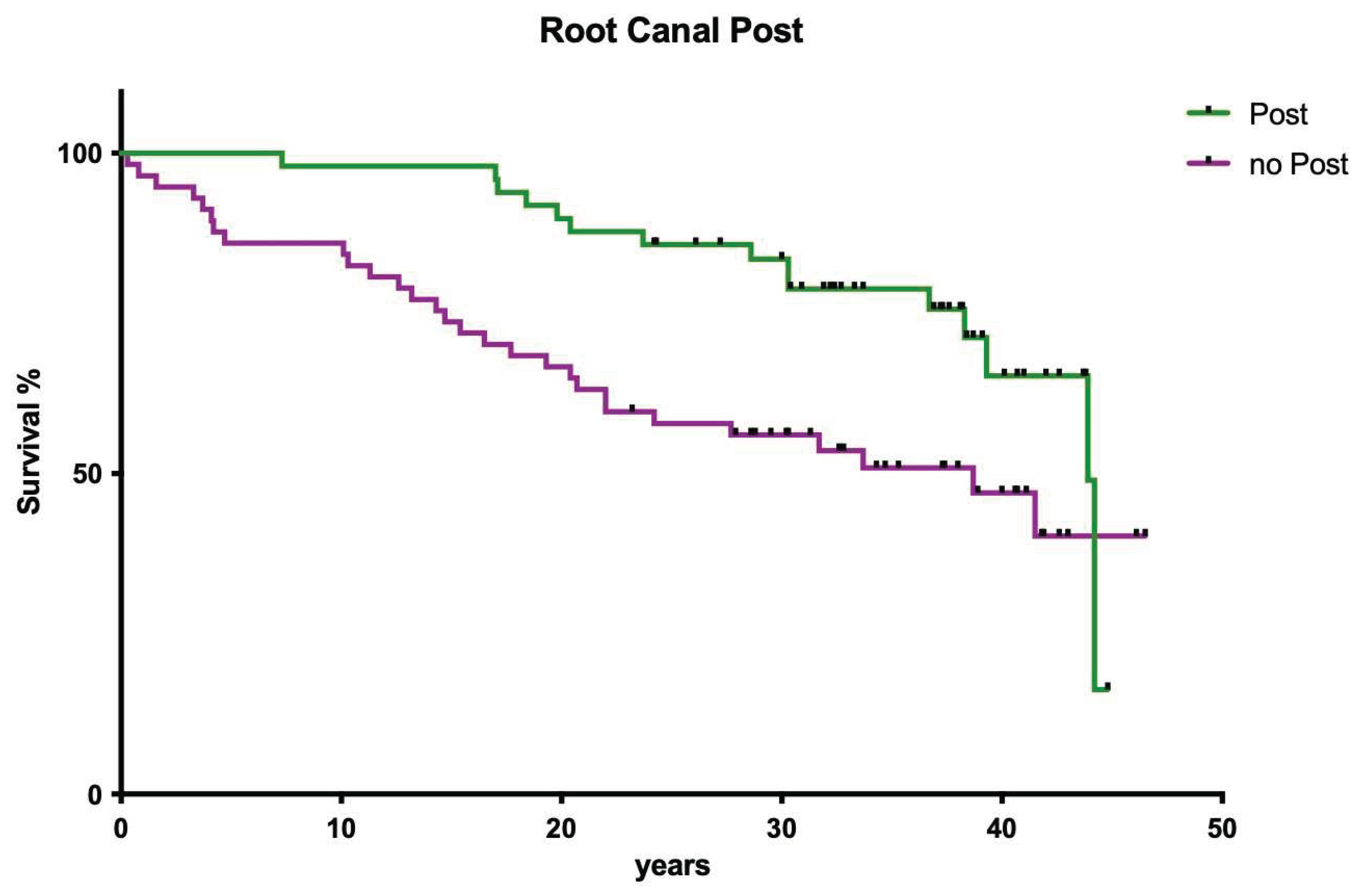

3.1.5. Influence of post insertion

The presence of postendodontically inserted root canal posts had no influence on clinical long-term success (

Figure 5; p>0.05).

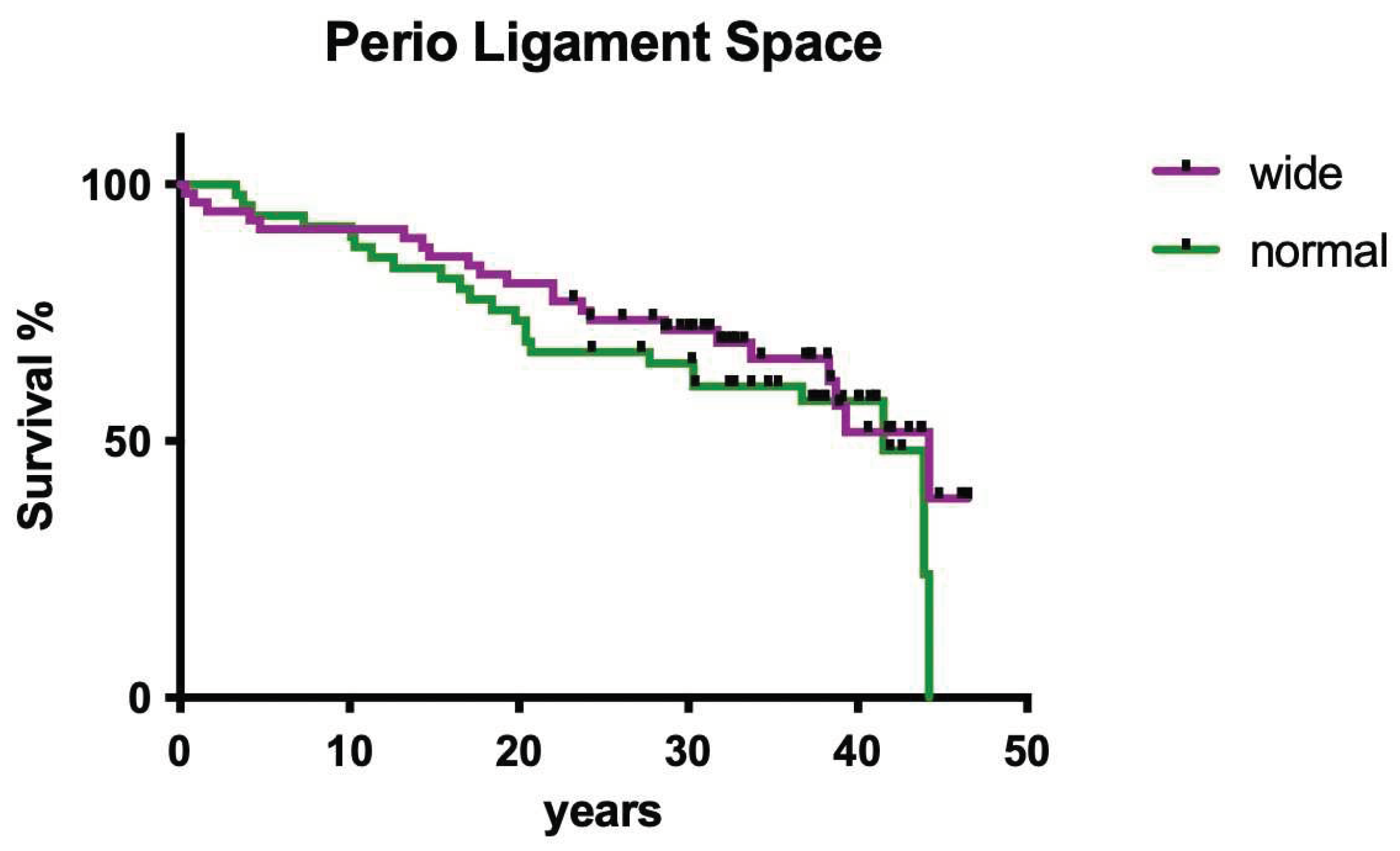

3.1.6. Influence of periodontal ligament space

The radiographically evaluated width of the periodontal ligament space did not show a significant influence on clinical outcome (

Figure 6; p>0.05).

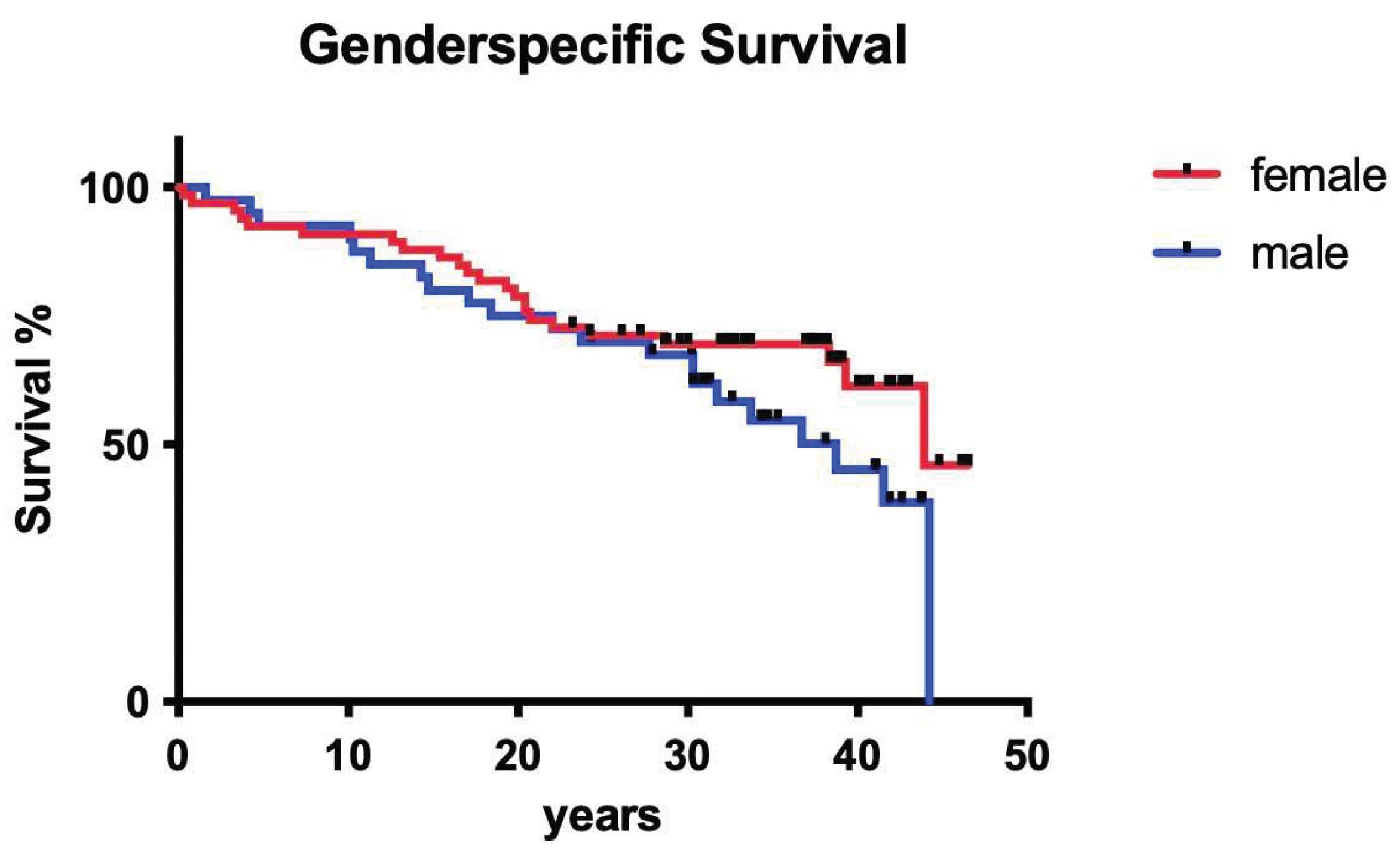

3.1.7. Influence of gender

Sex of the patients did not show a significant influence on long-term tooth survival (

Figure 7; p>0.05).

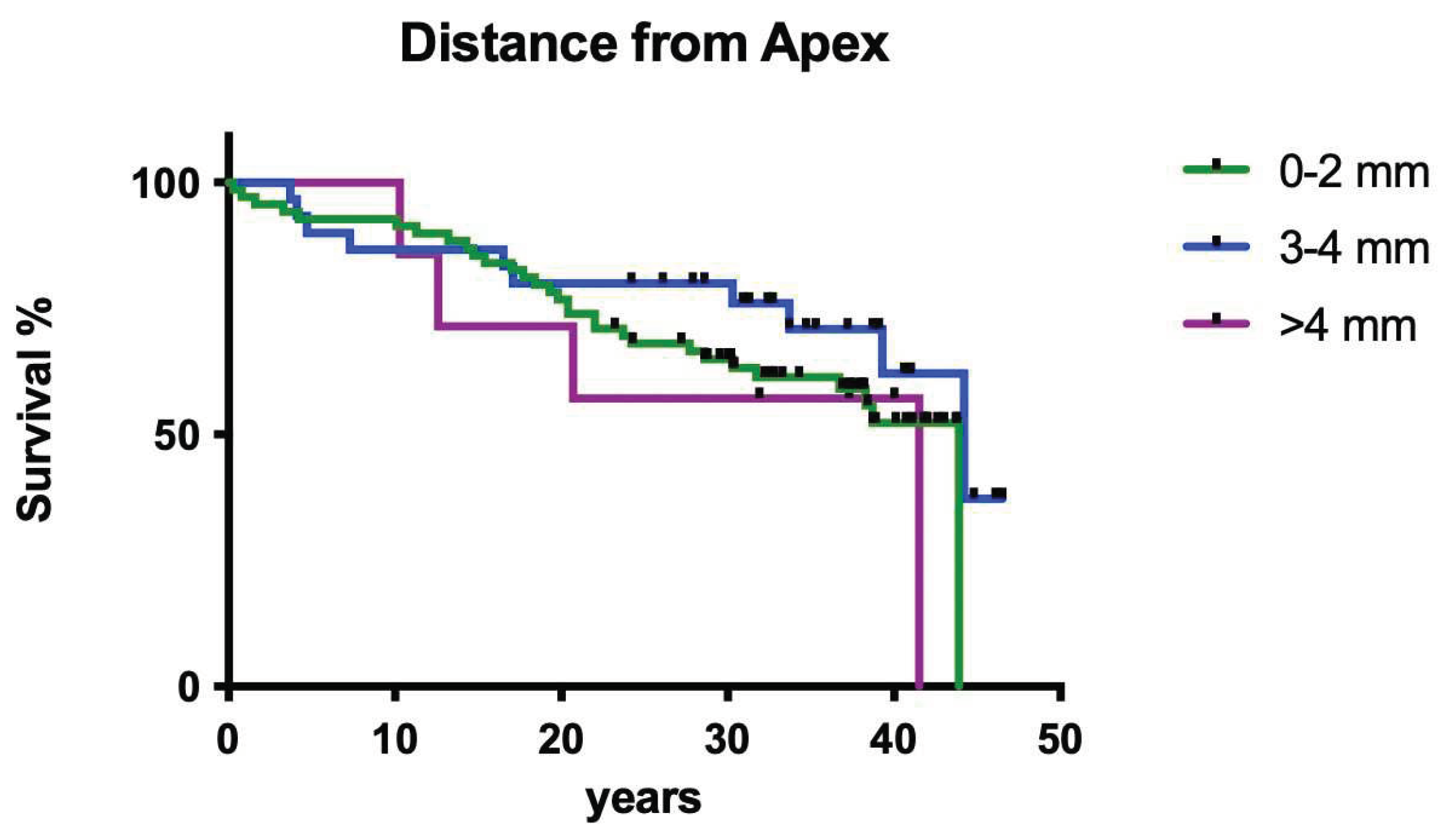

3.1.8. Influence of working length

The measured distance of the root canal filling to the radiological apex did not have a significant influence on clinical long-term survival of endodontically treated teeth (

Figure 8; p>0.05).

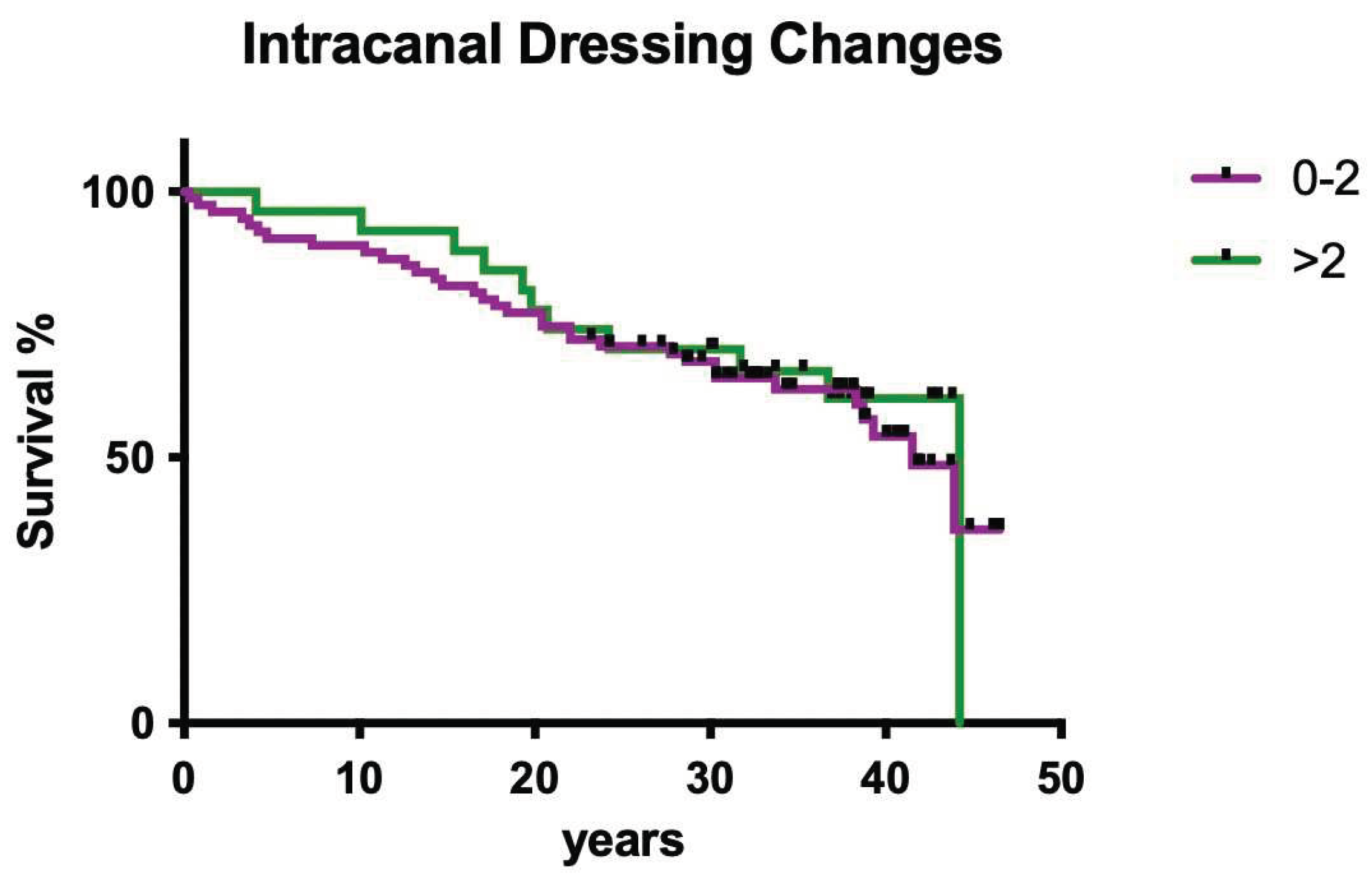

3.1.9. Influence of intracanal dressing changes

The number of intracanal medicament dressing changes did not have a significant effect on clinical outcome (

Figure 9; p>0.05).

3.2. Clinical outcome practitioner B

3.2.1. Overall survival

Overall clinical survival of operator B was slightly higher compared to operator A, but not statistically significant (

Figure 10; p>0.05).

3.2.2. Jaw

Jaw position had no significant impact on overall survival (

Figure 11; p>0.05).

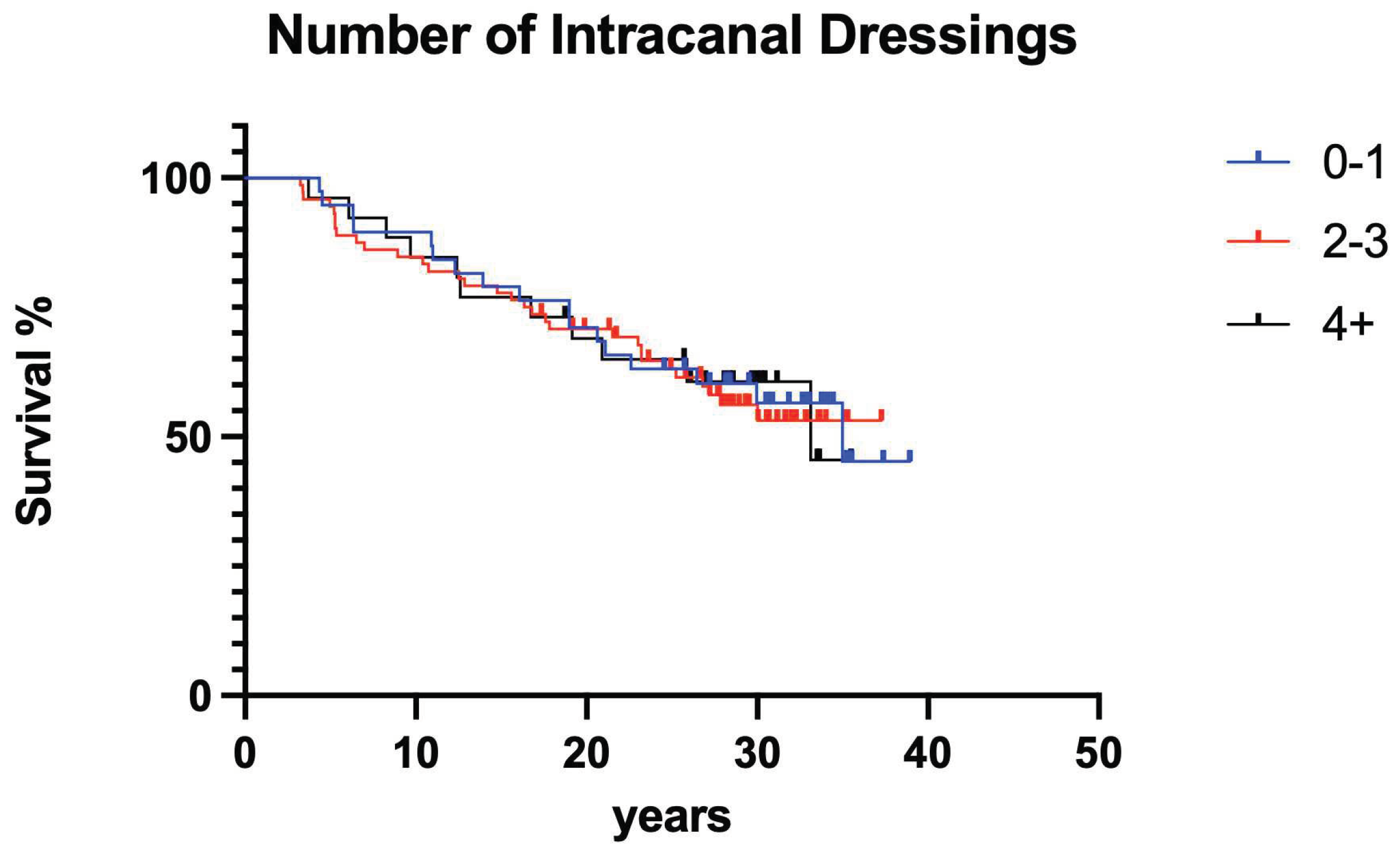

3.2.3. Number of intracanal dressing changes

The number of intracanal medicament dressing changes did not have a significant effect on clinical outcome (

Figure 12; p>0.05).

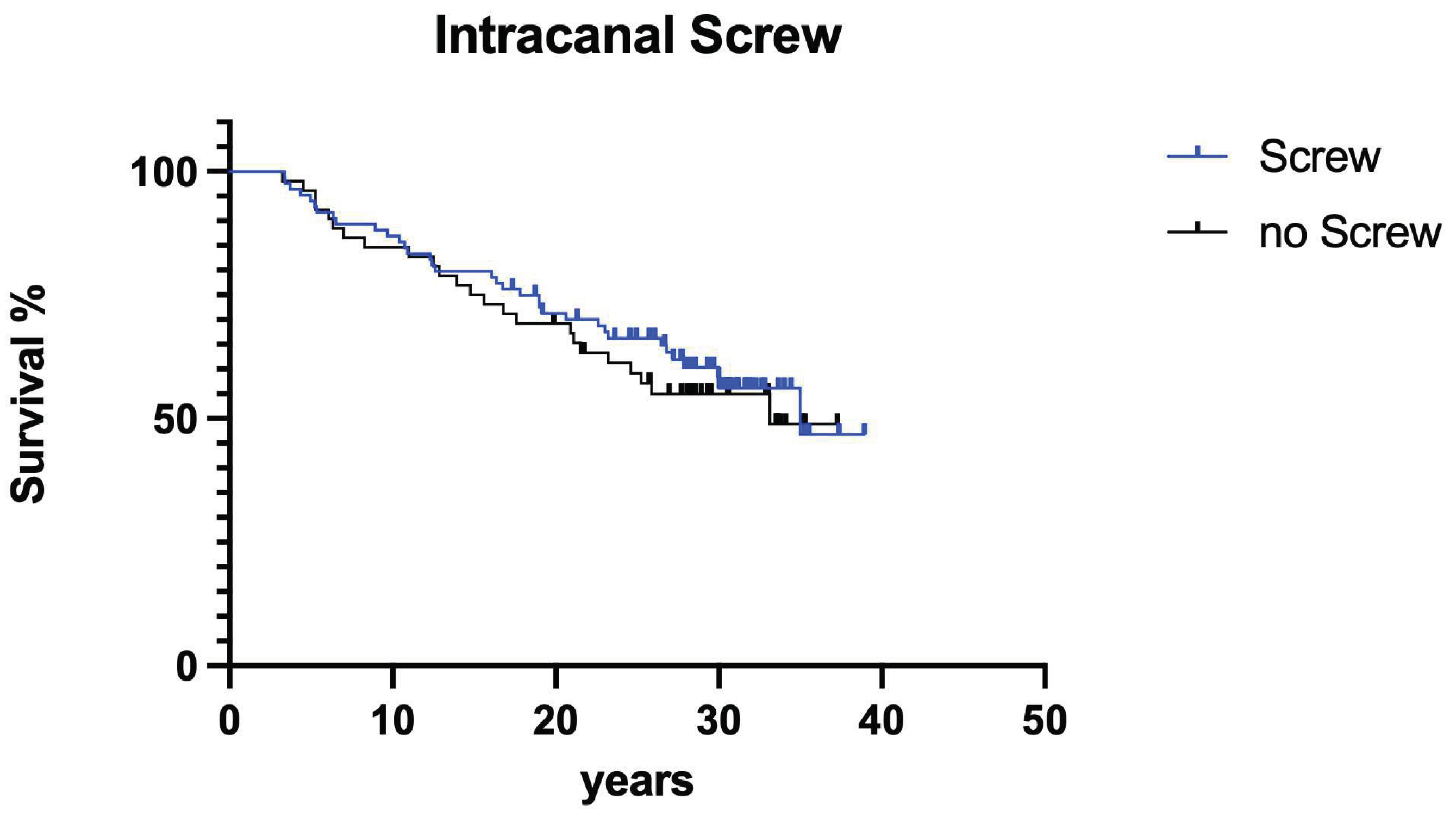

3.2.4. Screws

The presence of postendodontically inserted root canal retention screws had no influence on clinical long-term success (

Figure 13; p>0.05).

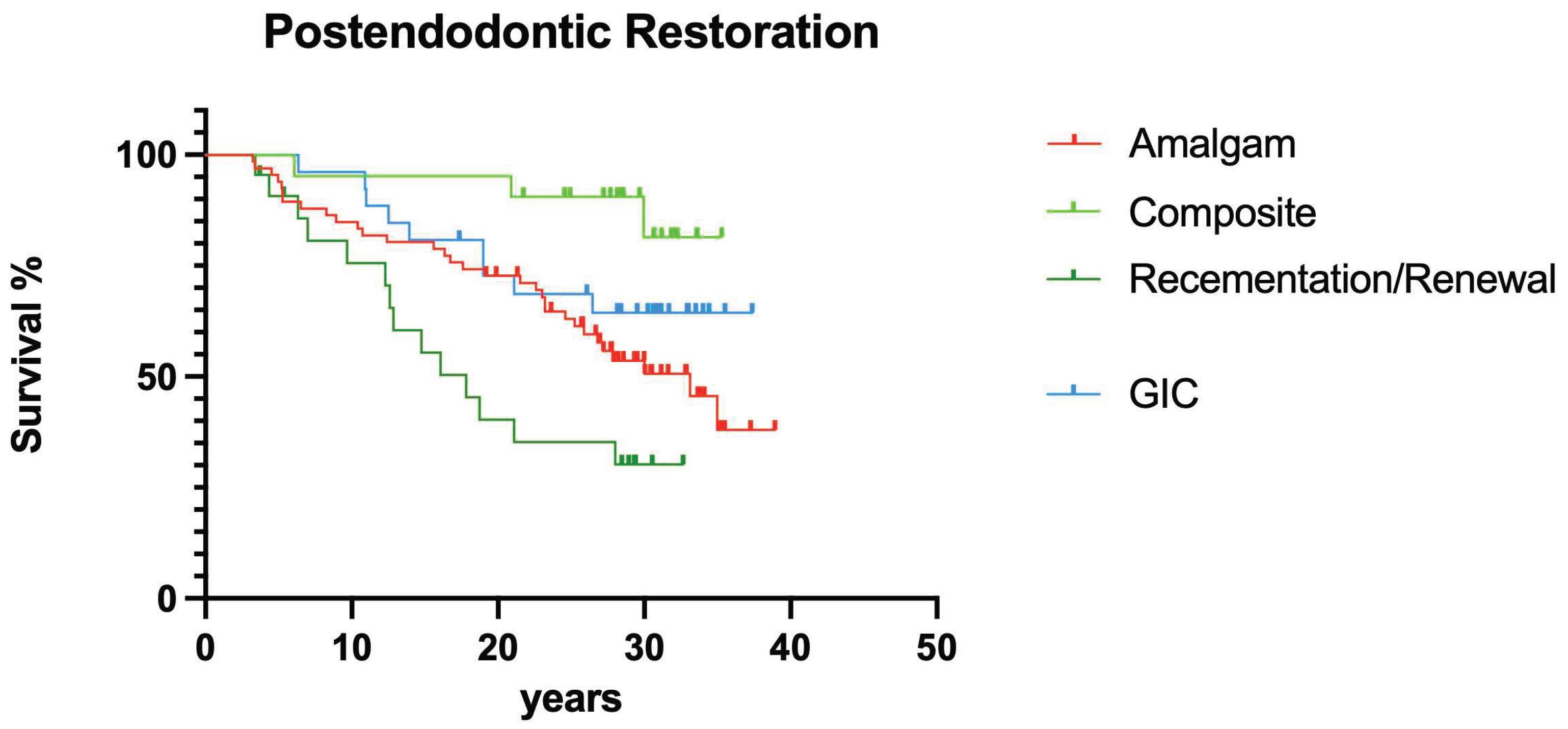

3.2.5. Postendodontic restoration

Different postendodontic restorations showed a significant effect on overall survival, direct resin composite restorations lead to less failures compared to prosthetic restorations (

Figure 14; p<0.05).

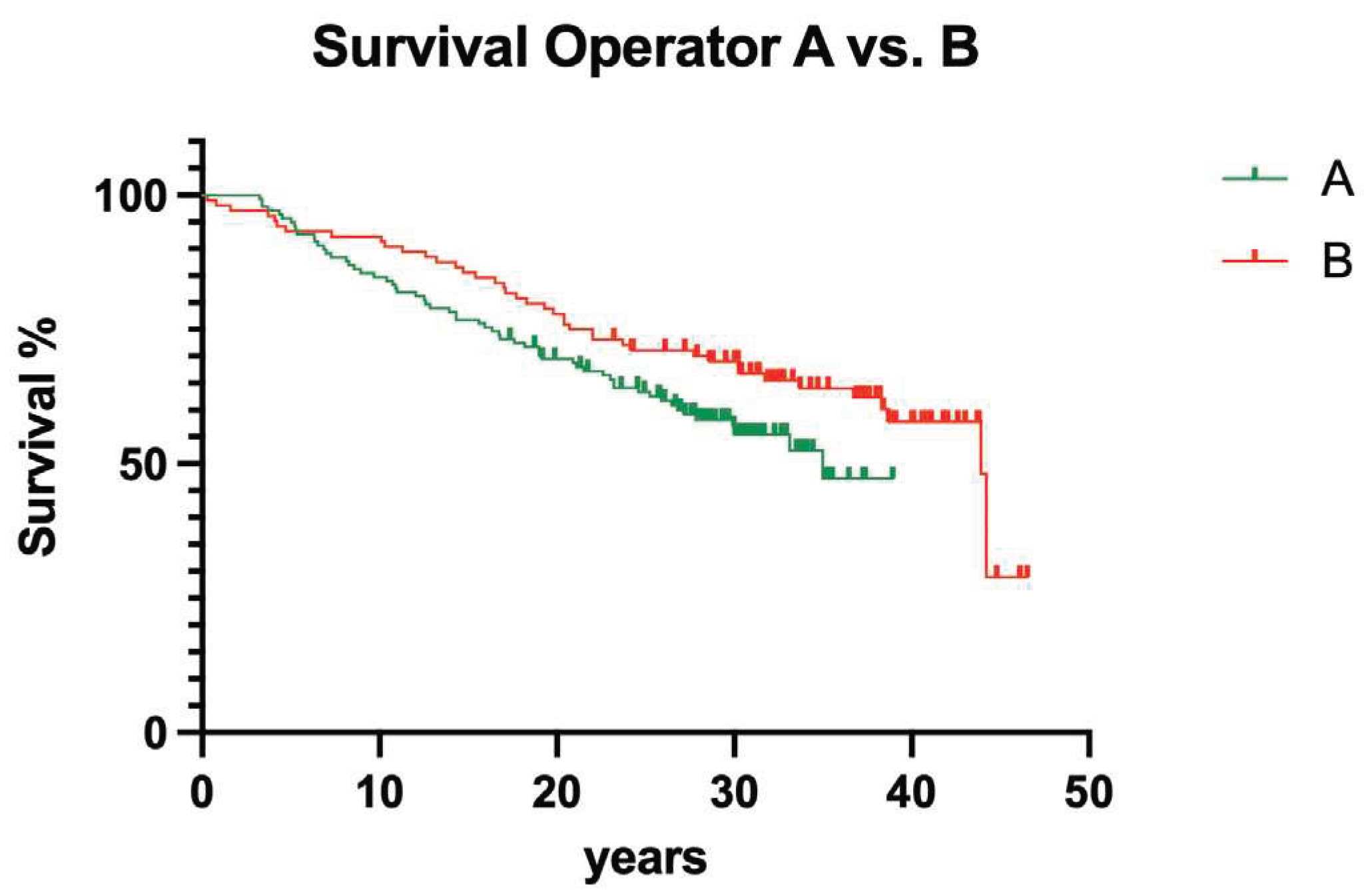

3.3. Interoperator comparison

Between the operators having been involved in the present study, no significant influence could be computed (

Figure 15; p>0.05).

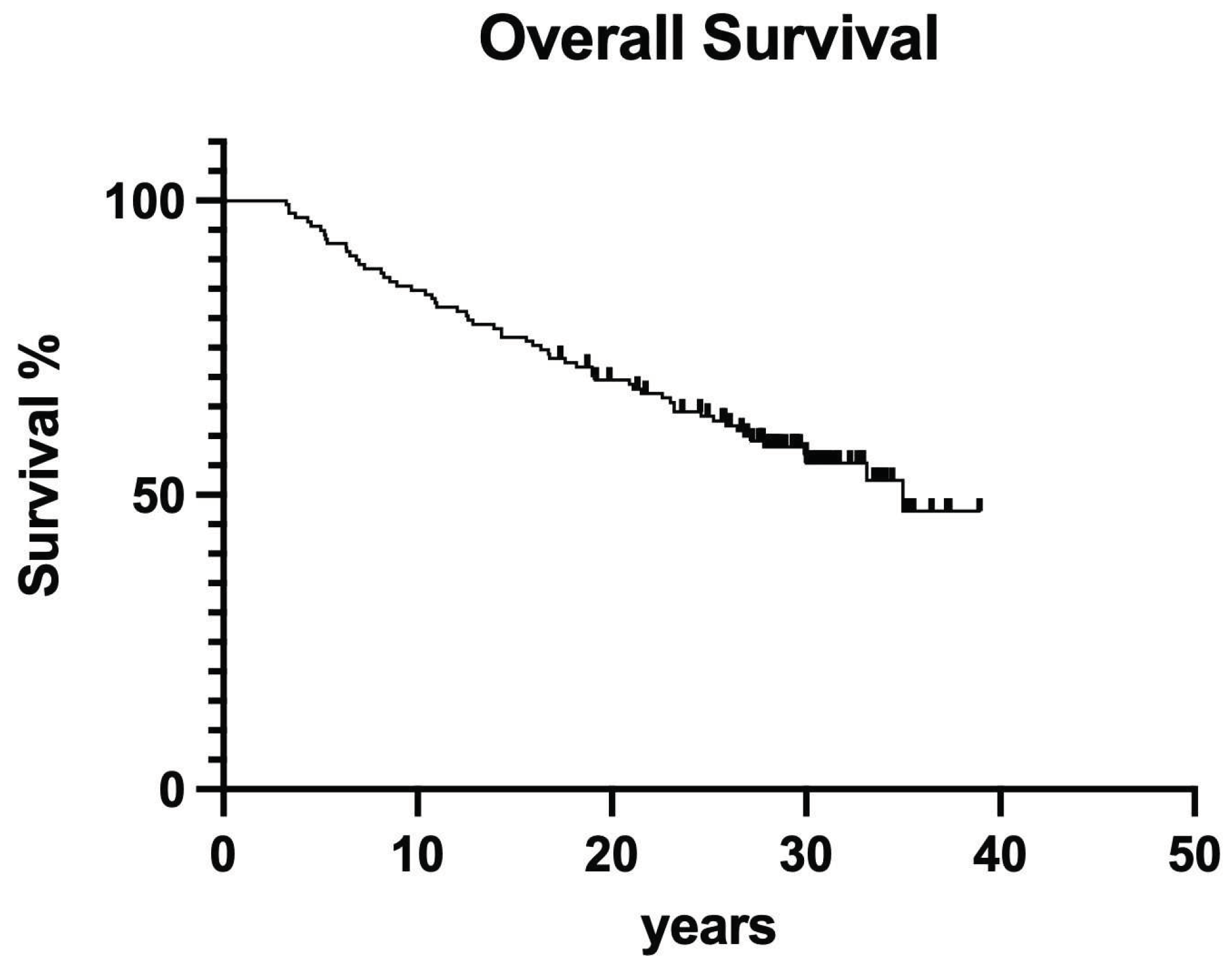

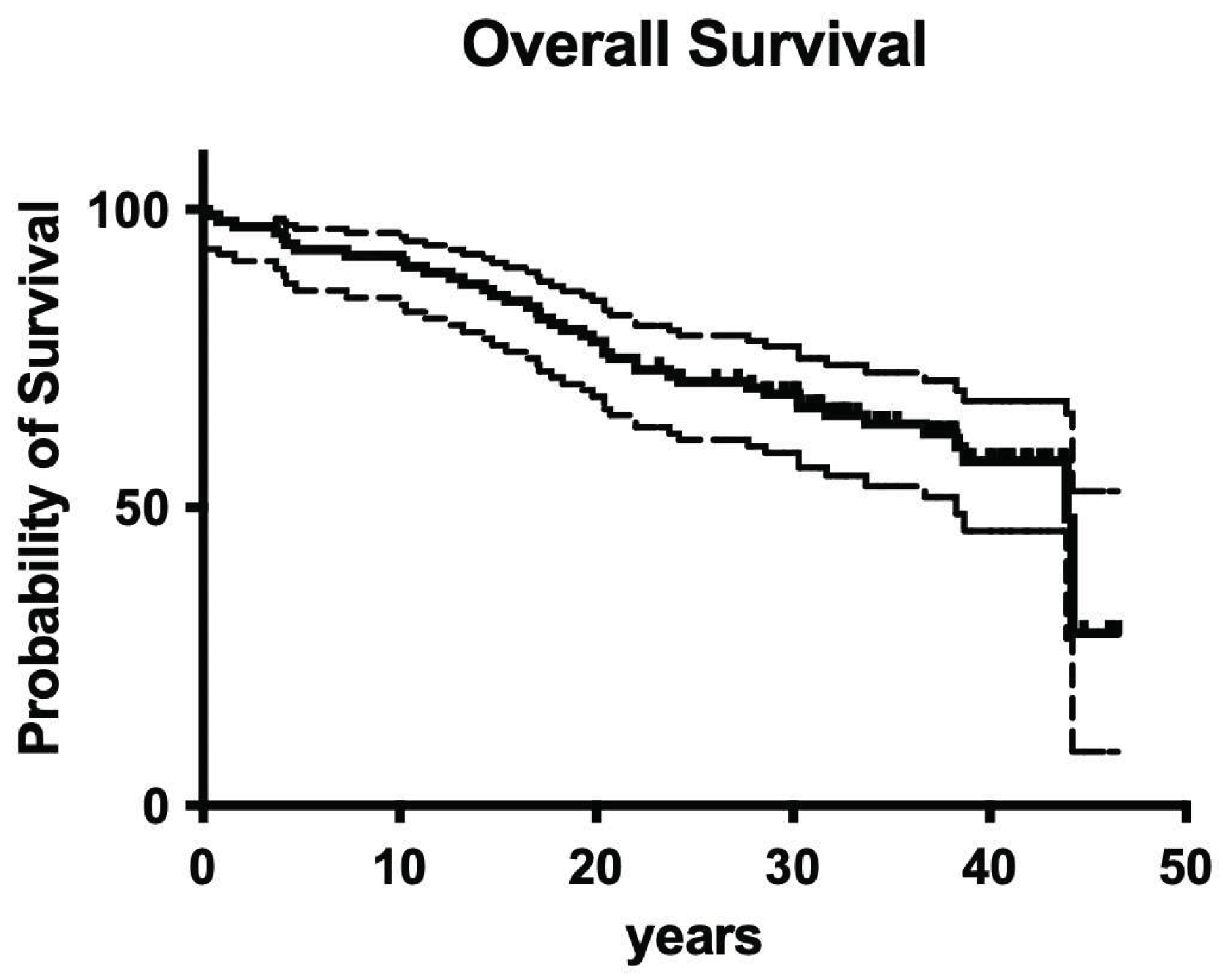

3.4. Overall survival

Overall survival for the whole retrospective study was 56.1% after 40 years of clinical service (

Figure 16).

4. Discussion

Without having an overwhelming load of clinical long-term studies in endodontics available, it is well-known from the literature in the field that endodontic treatments are both successful and responsible for tooth preservation in the long run[

4,

18,

19].

Although there is an enormous progress in root canal preparation techniques documented using any kind of more flexible and less deviating NiTi-instruments[

17,

26], it is still not fully understood and known whether old-fashioned root canal treatment regimens of the past have been successful, too. There may be the primary concern of using too stiff steal instruments causing routine deviation of the root canal system potentially leading to significantly less overall success of endodontic measures. Furthermore, also clearly obsolete intracanal medicaments and sealer materials have been used back then and today no one would even think to use them again because meanwhile exist much better alternatives in any indication[

5,

27,

28]. Therefore, the aim of the present retrospective evaluation was to investigate 1970/80’s style endodontic treatment outcome over more than four decades.

To cut a long story short: Also old-fashioned non-surgical endodontic treatment was successful over the observation period of 40 years. It is astonishing that after 40 years, more than 50% of endodontically treated teeth are still in function (Figures 16, 17). Although materials and techniques have been used that are completely disregarded as obsolete today, in the end the observed and documented outcome was excitingly good. So when materials and techniques are obviously less decisive factors for clinical outcome, what is it? Having a closer look into the treatment protocols of the available documentations clearly shows two important aspects: 1. Both operators have been very experienced, a factor that has been shown to be of predominant importance in other fields of dentistry[

29], and 2. Only teeth with absolutely no loosening have been included in the study because both operators also had a strong background in Periodontology. So based on the data of the present evaluation both factors seem to positively influence long-term outcome of endodontic treatments.

Concerning the evaluated co-factors for clinical success, it was shown that gender of patients, jaw, tooth position (anterior vs. posterior), and number of intracanal dressing/medication changes did not show a significant influence on clinical outcome. Compared to the literature in the field of endodontology, the most surprising finding of the present study was clearly that the distance from root filling to radiographical apex apparently did not affect clinical outcome. This may be justified by the fact that many pulpectomies have been performed as primary endodontic treatment with less need for disinfection protocols[

4,

5,

17], however, it remains astonishing.

It has been reported that the quality of the individual post-endodontic restoration is an important factor for long-term tooth survival[

21,

23,

24,

25], sometimes it was even regarded as more important than the quality of root canal obturation itself[

20]. Also in the present trial, significant differences between the involved post-endodontic restorations have been computed. Although adhesive technologies have been neither fully understood nor extremely advanced back in the 1980’s, the outcome of resin composite fillings as post-endodontic restorations was surprisingly good. However, as normally smaller defects receive more direct resin composite restorations[

24], retrospectively this observation may just be correlated to primary cavity as well as defect size and therefore be somewhat questionable. And although screw-retained post-endodontic build-ups have been reported as inferior measures[

30], the present data revealed no difference between screws and posts, however, compared to more adhesive times, every single post was luted with conventional cements and not fully adhesively luted like today [

23,

24,

25]. This may explain the similar results when it comes to screws vs. posts for post-endodontic build-up[

23,

24,

25].

Nevertheless, facing the array of clinical variables that have not been known or fully understood in the 1980’s combined with the fact that flexibility of root canal instruments has been mainly underdeveloped[

26], the overall outcome of the present retrospective investigation is surprisingly good. This also has a significant impact on quality of life for the investigated group of patients[

12]. The final critical question remains: Although we know so much more today in almost every aspect that has been investigated here[

23], and although we definitely have access to much more advanced materials, methods, and protocols[

21]: Are really more successful today in clinical endodontics?[

16]

5. Conclusions

Endodontic treatment of root canals having been filled in the 1980’s showed a good clinical outcome over 40 years of clinical service. Both experience of the operators and narrow/strict indication seem to be decisive factors for clinical success.

Supplementary Materials

on file.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B. methodology, R.F.; software, A.K., B.B.-B., M.J.R; validation, R.F. and A.K.; formal analysis, R.F.; investigation, C.B. and H.-U. A.; resources, S.B.; data curation, R.F and M.J.R; writing—original draft preparation, R.F. and A.K.; writing—review and editing, R.F.; visualization, A.K.; supervision, S.B. and R.F.; project administration, R.F.; M.J.R. and A.K. contributed equally. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Banerjee A, Splieth C, Breschi L et al. When to intervene in the caries process? A Delphi consensus statement. Br Dent J 2020; 229 (7): 474-482. [CrossRef]

- Schwendicke F, Splieth CH, Bottenberg P et al. How to intervene in the caries process in adults: proximal and secondary caries? An EFCD-ORCA-DGZ expert Delphi consensus statement. Clin Oral Investig 2020; 24 (9): 3315-3321. [CrossRef]

- European Society of Endodontology developed b, Duncan HF, Galler KM et al. European Society of Endodontology position statement: Management of deep caries and the exposed pulp. Int Endod J 2019; 52 (7): 923-934. [CrossRef]

- Chopra V, Davis G, Baysan A. Clinical and Radiographic Outcome of Non-Surgical Endodontic Treatment Using Calcium Silicate-Based Versus Resin-Based Sealers-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Studies. J Funct Biomater 2022; 13 (2). [CrossRef]

- Van Nieuwenhuysen JP, D'Hoore W, Leprince JG. What ultimately matters in root canal treatment success and tooth preservation: A 25-year cohort study. Int Endod J 2023; 56 (5): 544-557. [CrossRef]

- Frankenberger R, Van Meerbeek B. Editorial: Citations in Science - Original Research vs Review Papers. J Adhes Dent 2020; 22 (3): 231.

- Cornish F. Evidence synthesis in international development: a critique of systematic reviews and a pragmatist alternative. Anthropol Med 2015; 22 (3): 263-277. [CrossRef]

- Duncan HF, Kirkevang LL, Orstavik D, Sequeira-Byron P. Research that matters--clinical studies. Int Endod J 2016; 49 (3): 224-226.

- Greener M. The good, the bad and the ugly red tape of biomedical research. How could regulators lower bureaucratic hurdles in clinical research without compromising the safety of patients? EMBO Rep 2009; 10 (1): 17-20.

- Osanto S, van Poppel H, Burggraaf J, Hall RR. Hurdles in modern trial management: as overbureaucracy and commercialization of clinical trials suffocate independent academic research, it's time for a change. Eur Urol 2009; 56 (4): 622-624. [CrossRef]

- Dugas NN, Lawrence HP, Teplitsky P, Friedman S. Quality of life and satisfaction outcomes of endodontic treatment. J Endod 2002; 28 (12): 819-827. [CrossRef]

- Leong DJX, Yap AU. Quality of life of patients with endodontically treated teeth: A systematic review. Aust Endod J 2020; 46 (1): 130-139. [CrossRef]

- Neelakantan P, Liu P, Dummer PMH, McGrath C. Oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) before and after endodontic treatment: a systematic review. Clin Oral Investig 2020; 24 (1): 25-36. [CrossRef]

- Hatipoglu O, Hatipoglu FP, Javed MQ et al. Factors Affecting the Decision-making of Direct Pulp Capping Procedures among Dental Practitioners: A Multinational Survey from 16 Countries with Meta-analysis. J Endod 2023; 49 (6): 675-685. [CrossRef]

- Bergenholtz G, Kvist T. Call for improved research efforts on clinical procedures in endodontics. Int Endod J 2013; 46 (8): 697-699. [CrossRef]

- Leprince JG, Van Nieuwenhuysen JP. The missed root canal story: aren't we missing the point? Int Endod J 2020; 53 (8): 1162-1166.

- Ricucci D, Russo J, Rutberg M et al. A prospective cohort study of endodontic treatments of 1,369 root canals: results after 5 years. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2011; 112 (6): 825-842.

- Ng YL, Mann V, Gulabivala K. A prospective study of the factors affecting outcomes of nonsurgical root canal treatment: part 1: periapical health. Int Endod J 2011; 44 (7): 583-609. [CrossRef]

- Friedman S, Abitbol S, Lawrence HP. Treatment outcome in endodontics: the Toronto Study. Phase 1: initial treatment. J Endod 2003; 29 (12): 787-793. [CrossRef]

- Ray HA, Trope M. Periapical status of endodontically treated teeth in relation to the technical quality of the root filling and the coronal restoration. Int Endod J 1995; 28 (1): 12-18. [CrossRef]

- European Society of Endodontology developed b, Mannocci F, Bhuva B et al. European Society of Endodontology position statement: The restoration of root filled teeth. Int Endod J 2021; 54 (11): 1974-1981. [CrossRef]

- Bruhnke M, Naumann M, Beuer F et al. Implant or tooth? - A cost-time analysis of managing "unrestorable" teeth(✰). J Dent 2023; 136: 104646.

- Mannocci F, Bitter K, Sauro S et al. Present status and future directions: The restoration of root filled teeth. Int Endod J 2022; 55 Suppl 4 (Suppl 4): 1059-1084. [CrossRef]

- Naumann M, Schmitter M, Krastl G. Postendodontic Restoration: Endodontic Post-and-Core or No Post At All? J Adhes Dent 2018; 20 (1): 19-24.

- Naumann M, Schmitter M, Frankenberger R, Krastl G. "Ferrule Comes First. Post Is Second!" Fake News and Alternative Facts? A Systematic Review. J Endod 2018; 44 (2): 212-219.

- Schafer E, Zapke K. A comparative scanning electron microscopic investigation of the efficacy of manual and automated instrumentation of root canals. J Endod 2000; 26 (11): 660-664. [CrossRef]

- Stueland H, Orstavik D, Handal T. Treatment outcome of surgical and non-surgical endodontic retreatment of teeth with apical periodontitis. Int Endod J 2023; 56 (6): 686-696. [CrossRef]

- Winkler A, Adler P, Ludwig J et al. Endodontic Outcome of Root Canal Treatment Using Different Obturation Techniques: A Clinical Study. Dent J (Basel) 2023; 11 (8). [CrossRef]

- Frankenberger R, Reinelt C, Petschelt A, Kramer N. Operator vs. material influence on clinical outcome of bonded ceramic inlays. Dent Mater 2009; 25 (8): 960-968. [CrossRef]

- Schmitter M, Hamadi K, Rammelsberg P. Survival of two post systems--five-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Quintessence Int 2011; 42 (10): 843-850.

Figure 1.

Overall clinical survival of teeth treated by operator A.

Figure 1.

Overall clinical survival of teeth treated by operator A.

Figure 2.

Overall clinical survival in upper and lower jaws.

Figure 2.

Overall clinical survival in upper and lower jaws.

Figure 3.

Overall clinical survival of anterior vs. posterior teeth treated by operator A.

Figure 3.

Overall clinical survival of anterior vs. posterior teeth treated by operator A.

Figure 4.

Overall clinical survival of teeth with different infection of the root canal system.

Figure 4.

Overall clinical survival of teeth with different infection of the root canal system.

Figure 5.

Clinical survival of teeth with post vs. no post postendodontic restoration.

Figure 5.

Clinical survival of teeth with post vs. no post postendodontic restoration.

Figure 6.

Clinical survival of teeth with differently wide perio ligament spaces.

Figure 6.

Clinical survival of teeth with differently wide perio ligament spaces.

Figure 7.

Clinical survival of teeth in males vs. females.

Figure 7.

Clinical survival of teeth in males vs. females.

Figure 8.

Clinical survival of teeth with different working lengths.

Figure 8.

Clinical survival of teeth with different working lengths.

Figure 9.

Clinical survival of teeth with differently frequent root canal dressings.

Figure 9.

Clinical survival of teeth with differently frequent root canal dressings.

Figure 10.

Overall clinical survival of operator B.

Figure 10.

Overall clinical survival of operator B.

Figure 11.

Overall clinical survival of teeth in different jaws.

Figure 11.

Overall clinical survival of teeth in different jaws.

Figure 12.

Overall clinical survival of teeth with different numbers of intracanal dressings.

Figure 12.

Overall clinical survival of teeth with different numbers of intracanal dressings.

Figure 13.

Overall clinical survival of teeth screw vs. no screw.

Figure 13.

Overall clinical survival of teeth screw vs. no screw.

Figure 14.

Clinical survival of teeth with different postendodontic restorations.

Figure 14.

Clinical survival of teeth with different postendodontic restorations.

Figure 15.

Clinical survival of teeth with different operators.

Figure 15.

Clinical survival of teeth with different operators.

Figure 16.

Clinical survival of both operators.

Figure 16.

Clinical survival of both operators.

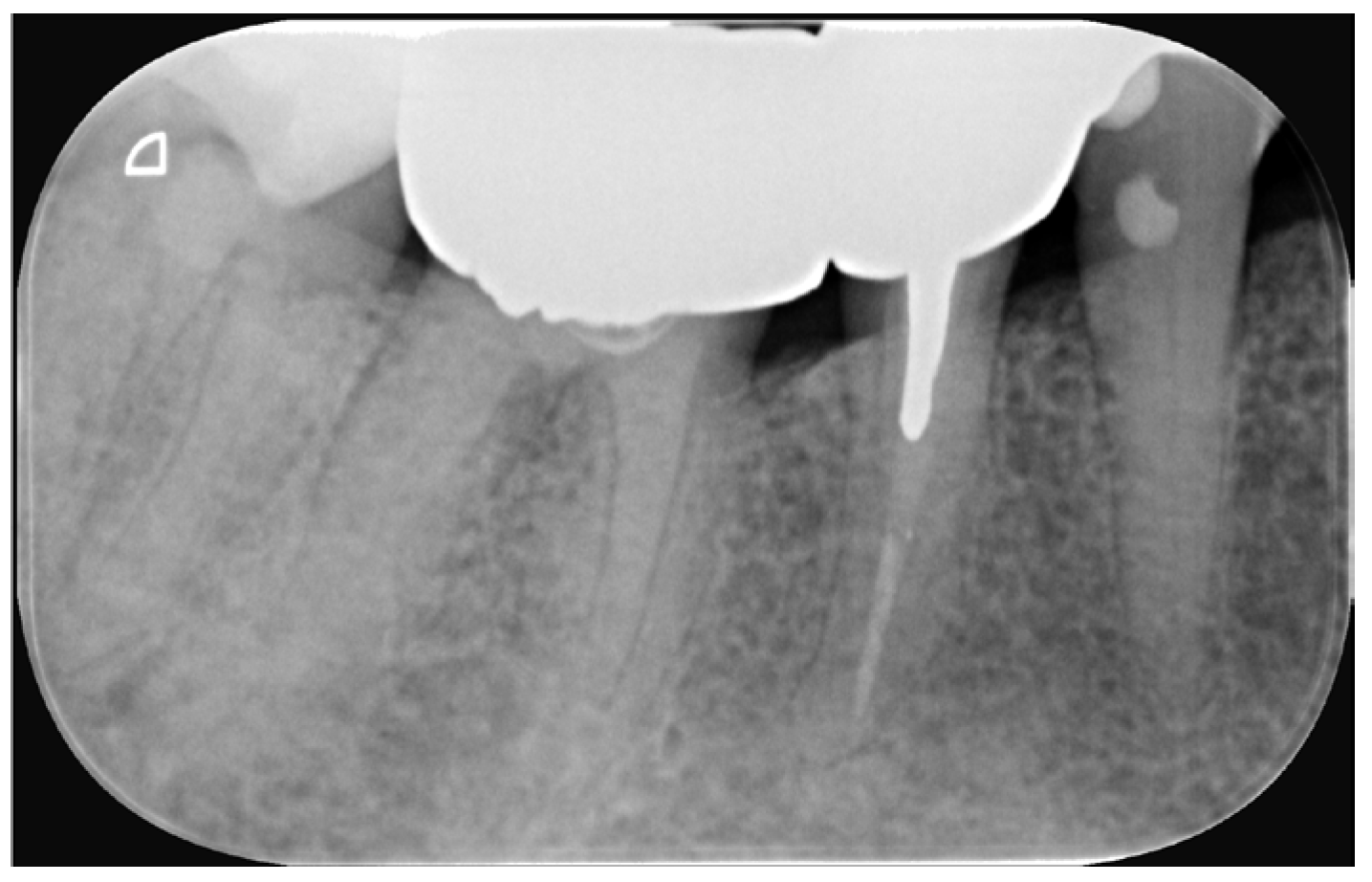

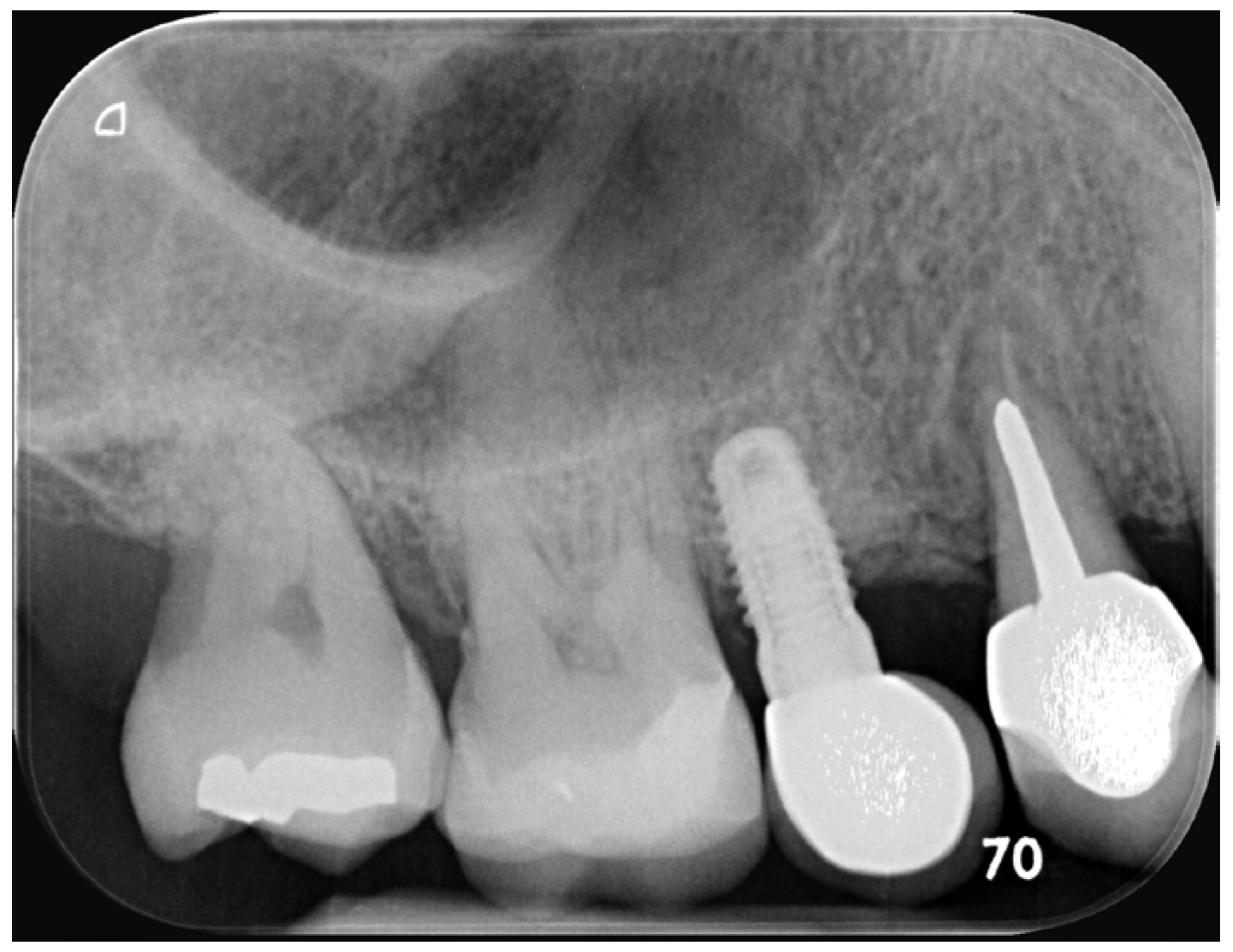

Figure 17.

Radiographic outcome.

Figure 17.

Radiographic outcome.

Table 1.

Variables and Co-variables of Operator 1.

Table 1.

Variables and Co-variables of Operator 1.

| Variables (P1) |

|

Endodontically treated teeth |

Extractions |

| Preoperative |

| |

|

n=107 |

n=46 |

| Gender |

male (29)

female (44) |

66 |

|

| Tooth location |

upper jaw

lower Jaw

anterior

posterior |

77

27

52

54 |

|

| Coronal caries |

|

63 |

31 |

| Root caries |

|

4 |

2 |

| Sensitivity to percussion |

Yes

no |

75

32 |

30

16 |

| Vitality status |

Vital

Non-vital |

29

75 |

16

30 |

| Presence of apical radiolucency |

Yes

no |

45

62 |

27

19 |

| Periapical space |

normal

enlarged |

49

58 |

23

23 |

| Tooth function |

Distal tooth in quadrant

Bridge in abutment

Double proximal contact |

13

10

84 |

4

9

33 |

| Distance root-canal filling to apex |

0-2 mm

2-3 mm

>=4 mm |

59

31

16 |

27

12

7 |

| Number of intracanal medications |

0

1

2

3

4 or more |

35

21

24

19

8 |

14

11

9

10

2 |

| Post |

Yes

no |

49

58 |

17

29 |

Table 2.

Variables and Co-variables of Operator B and comparisons A vs. B.

Table 2.

Variables and Co-variables of Operator B and comparisons A vs. B.

| Variables (P2) |

|

Endodontically treated teeth |

Extraction |

| Pre-operative |

| |

|

n=138 |

n=61 |

| Gender |

male

female |

|

|

| Deep caries |

|

11 |

6 |

| Vitality status |

vital

non-vital

no data |

46

60

32 |

23

23

15 |

| Pain symptoms |

yes

no data |

11

127 |

5

56 |

| Sensitivity to percussion |

yes

no |

137

1 |

61

0 |

| Operator |

P1

P2

P1 anterior

P1 posterior

P2 anterior

P2 posterior |

104

138

52

54

30

108 |

42

60

21

22

9

51 |

| Tooth location |

Upper jaw

Lower Jaw

Anterior upper jaw

Posterior upper jaw

Posterior lower jaw |

82

56

30

52

56 |

30

30

9

21

30 |

| Number of intracanal medications |

0-1

2-3

>/=4 |

38

72

26 |

17

31

11 |

| Duration from trepanation to root canal filling |

0

1-14 days

15-28 days

>28 days |

18

10

33

75 |

10

4

12

34 |

| Post |

Yes

no |

86

52 |

37

24 |

| Restoration |

Amalgam

Composite

Recementation/Renewal of prosthetic restoration

Glass-ionomer cement

|

66

21

22

26 |

33

3

14

9 |

| Periodontal therapy |

Yes

no |

30

108 |

13

47 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).