Submitted:

20 December 2023

Posted:

21 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Polymeric materials

2.2. Silicon substrates

2.3. Preparation of ultra-thin polymeric films by spin-coating

2.4. Preparation of thin and thick polymer films by drop-casting and casting

2.5. X-ray reflectivity measurements

2.6. Atomic Force Microscopy imaging

3. Results and Discussions

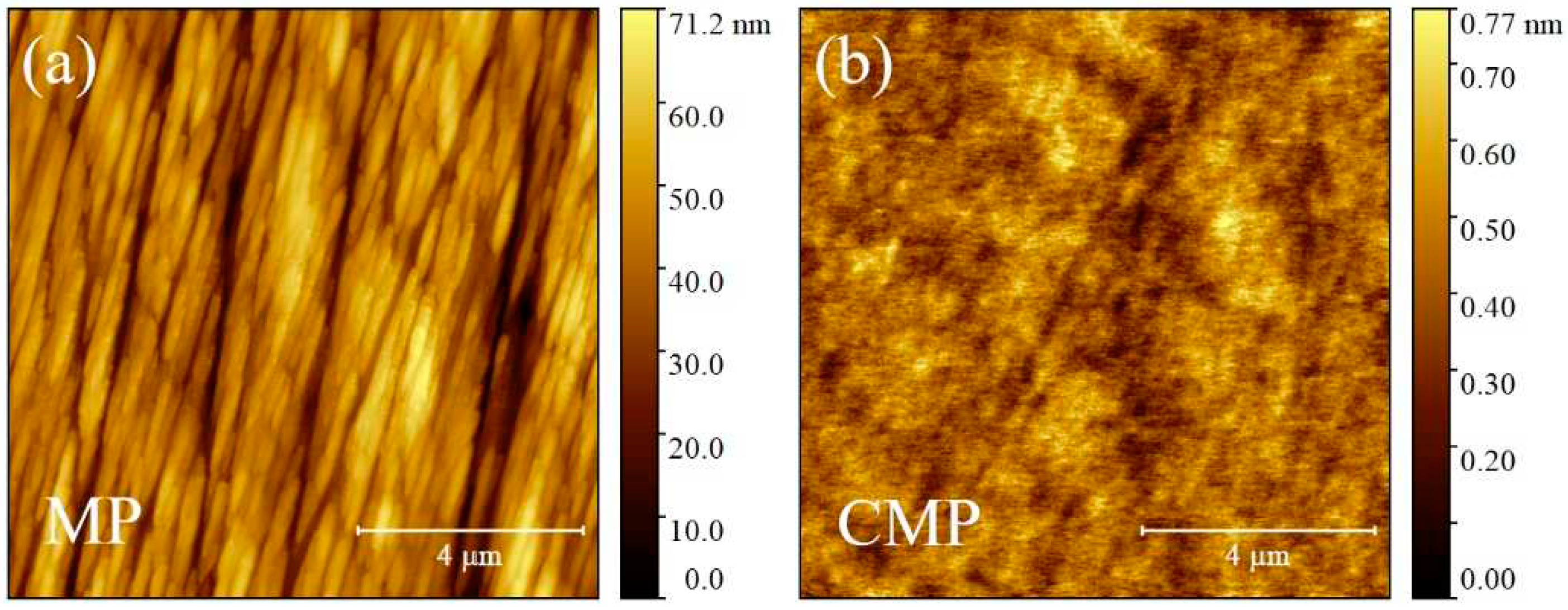

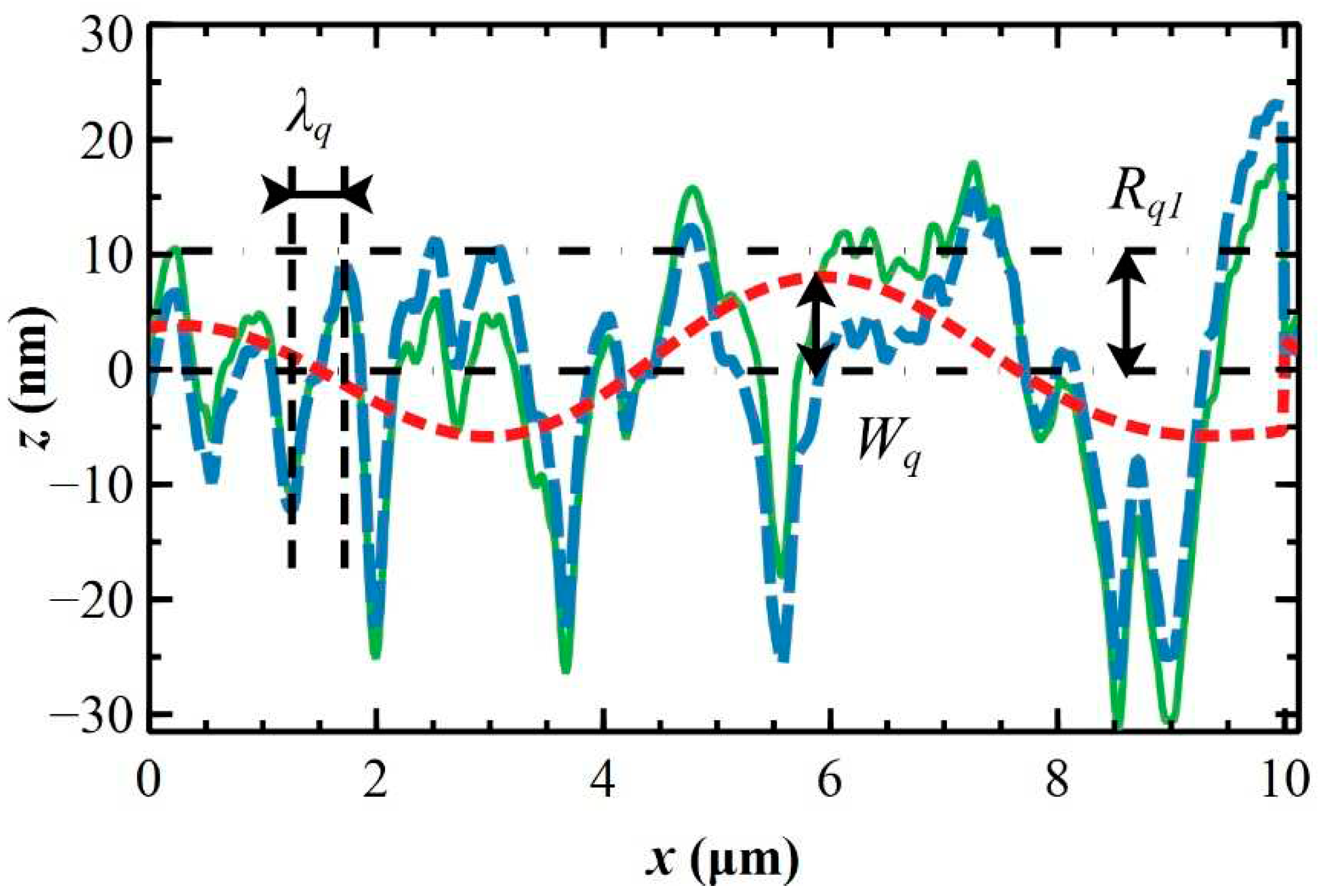

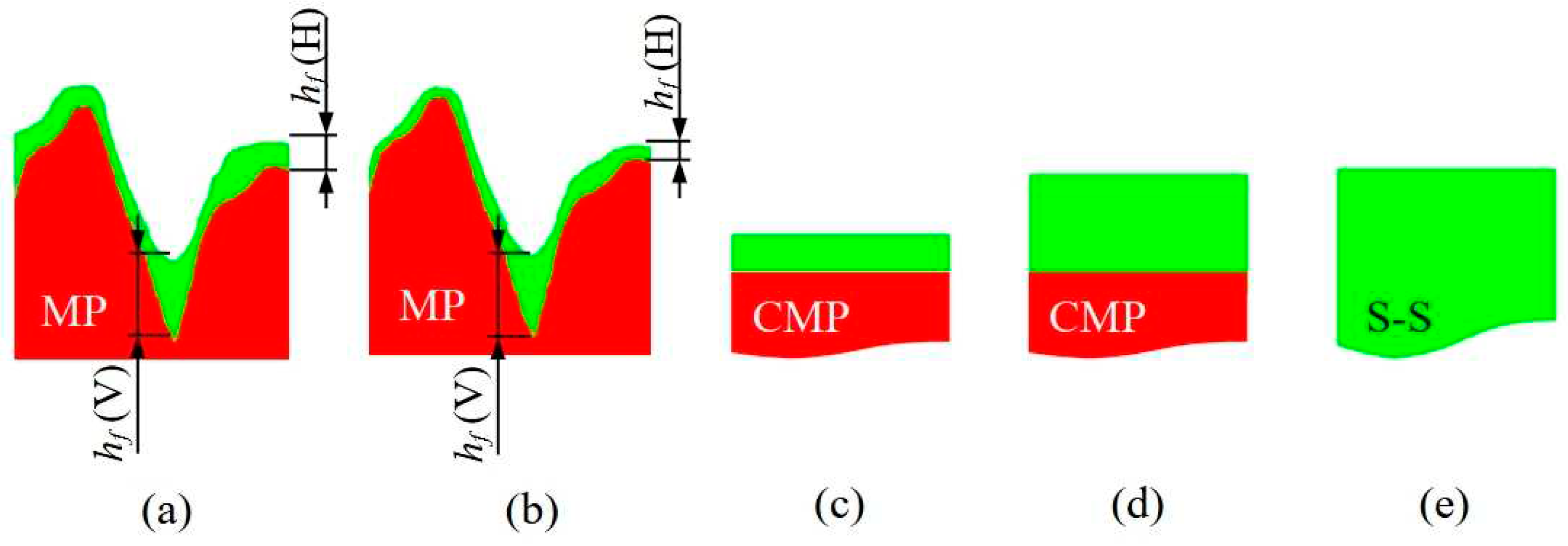

3.1. Morphological characterization of silicon substrates

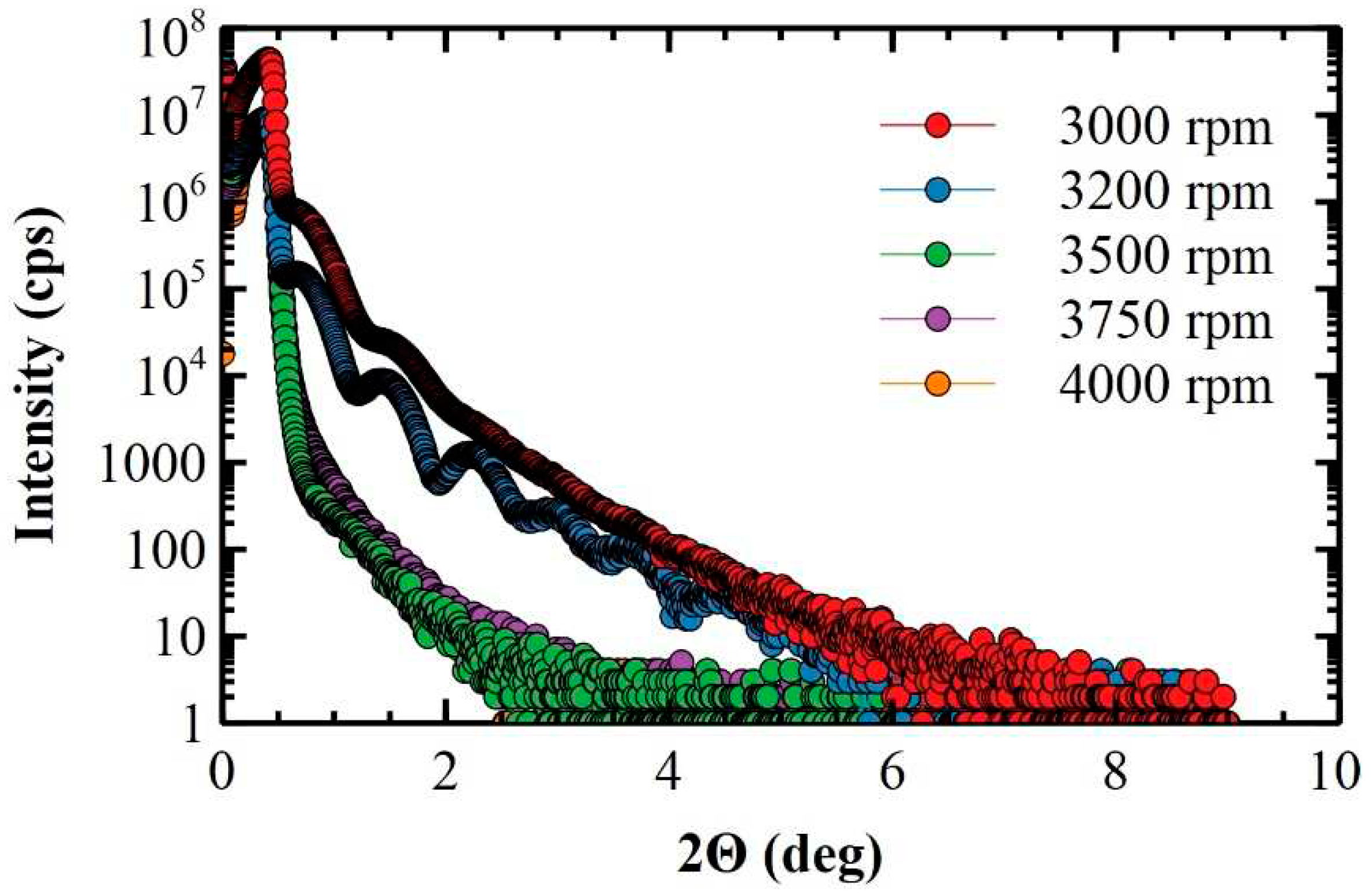

3.2. X-ray characterization of ultra-thin and thin polymeric films

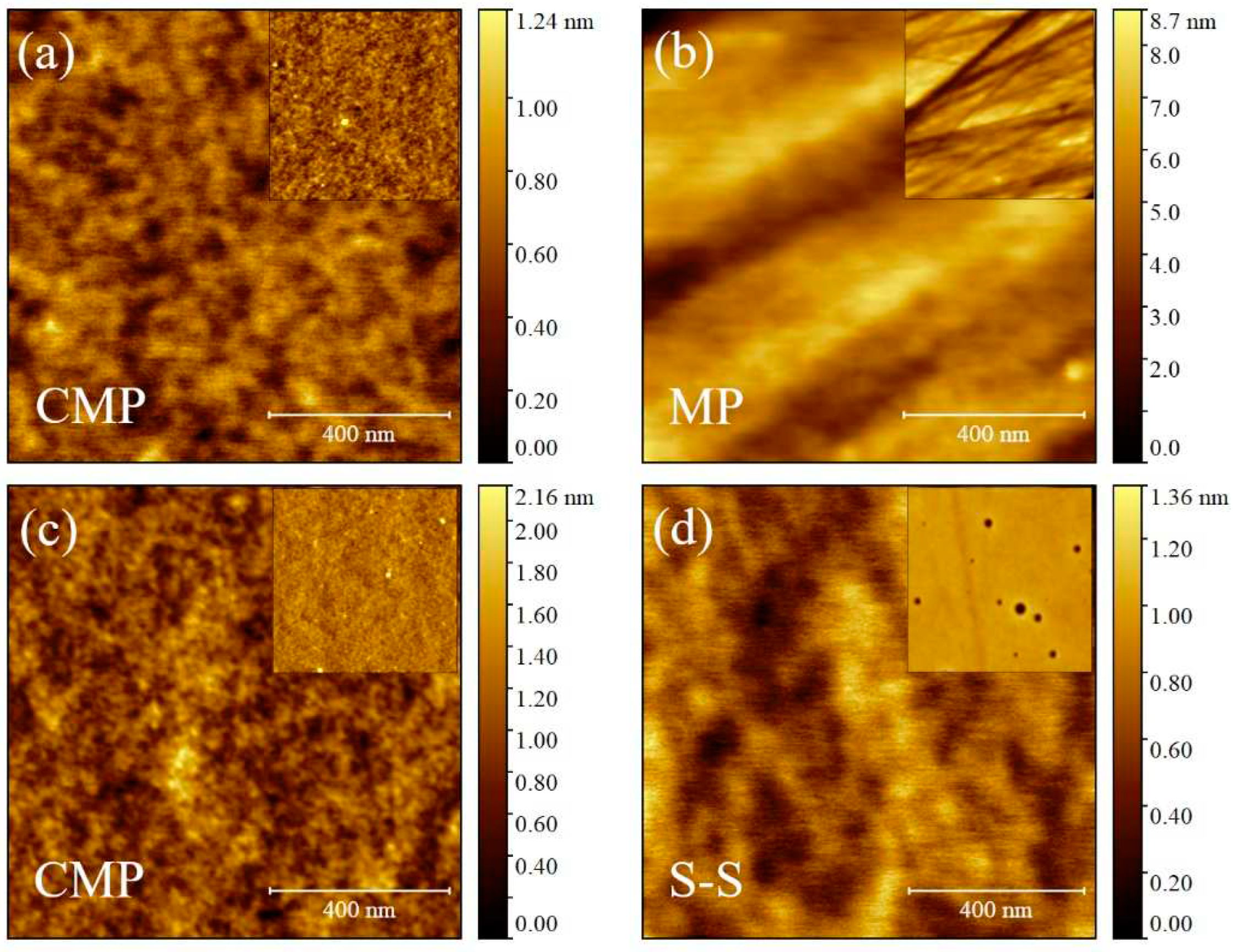

3.3. Morphological characterization of ultra-thin, thin and self-standing polymeric films

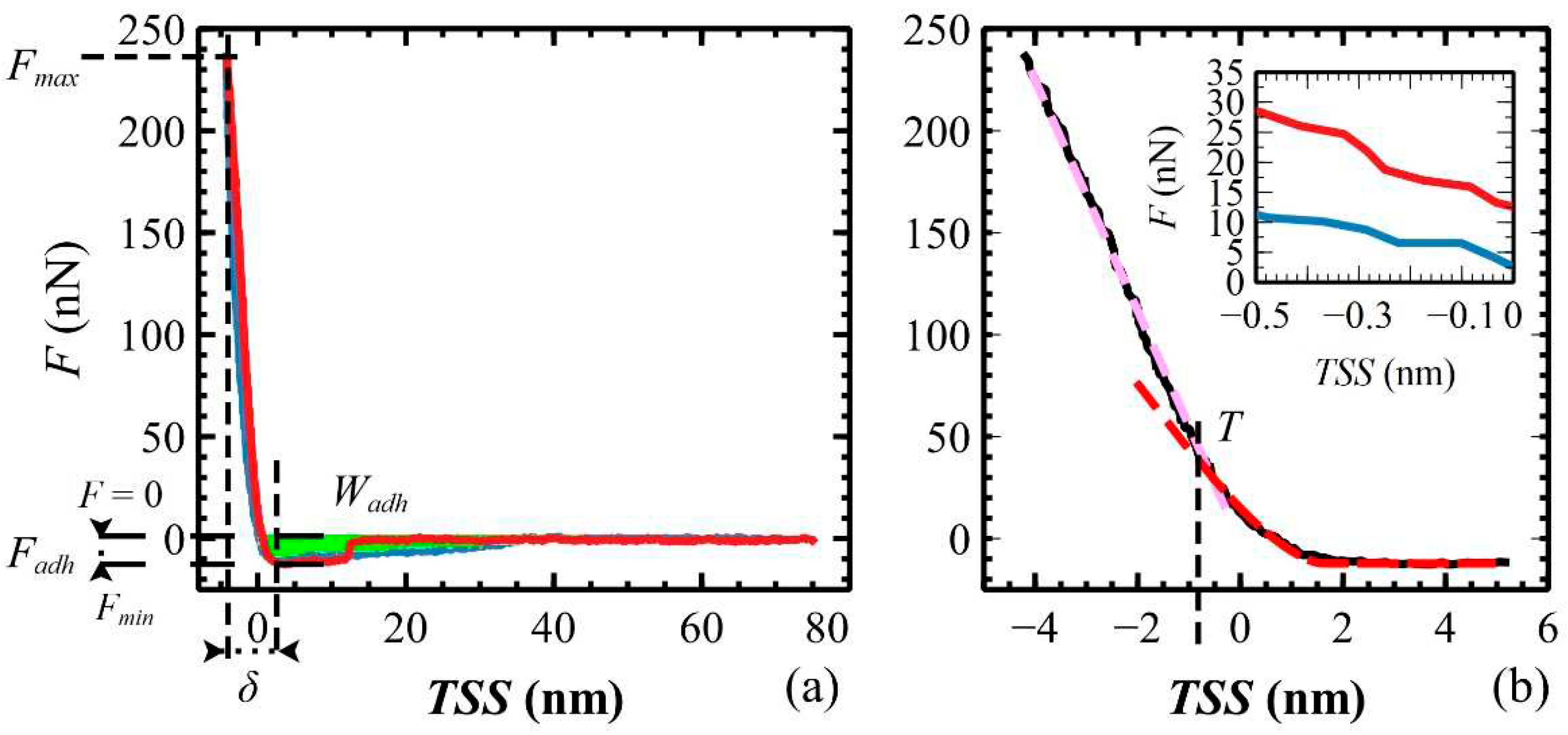

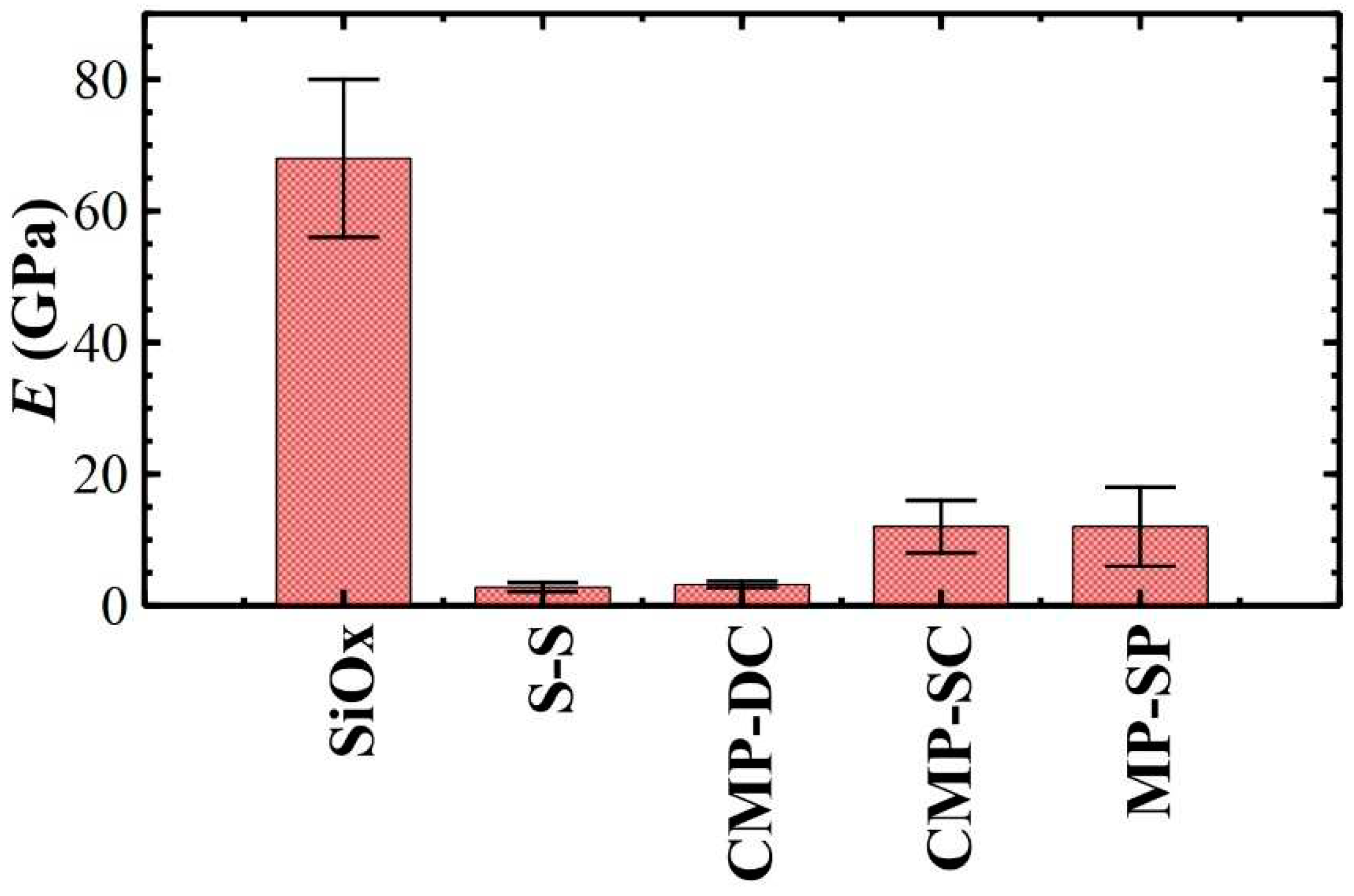

3.4. Elastic modulus of polymeric films measured in air

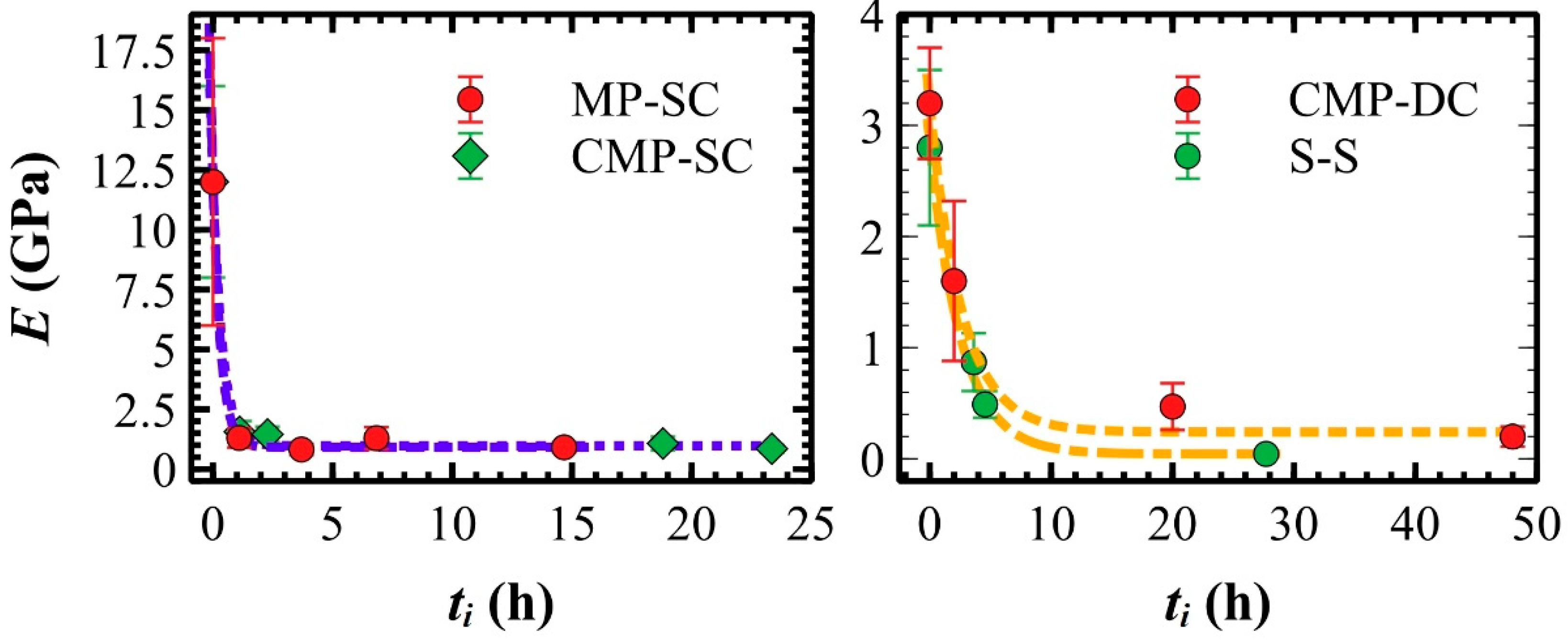

3.5. Elastic modulus of polymeric films measured in liquid

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gorrasi, G.; Stanzione, M.; Izzo, L. Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Star-like PEO-PMMA Based Copolymers. React. Funct. Polym. 2011, 71, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.K.; Bae, Y.H.; Kim, S.W. Star-Shaped Poly(Ether-Ester) Block Copolymers: Synthesis, Characterization, and Their Physical Properties. Macromolecules 1998, 31, 8766–8774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, L.; Pappalardo, D. “tree-Shaped” Copolymers Based on Poly(Ethylene Glycol) and Atactic or Isotactic Polylactides: Synthesis and Characterization. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2010, 211, 2171–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, M.; Li, H.; Li, H. The Degree of Crystallinity Exhibiting a Spatial Distribution in Polymer Films. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 107, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, W.; Li, J. Star Polymers: Advances in Biomedical Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2015, 46, 55–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigliotta, G.; Mella, M.; Rega, D.; Izzo, L. Modulating Antimicrobial Activity by Synthesis: Dendritic Copolymers Based on Nonquaternized 2-(Dimethylamino)Ethyl Methacrylate by Cu-Mediated ATRP. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrella, S.; Vitiello, C.; Mella, M.; Vigliotta, G.; Izzo, L. The Role of Charge Density and Hydrophobicity on the Biocidal Properties of Self-Protonable Polymeric Materials. Macromol. Biosci. 2015, 15, 927–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francolini, I.; Ruggeri, V.; Martinelli, A.; D’Ilario, L.; Piozzi, A. Novel Metal-Polyurethane Complexes with Enhanced Antimicrobial Activity. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2006, 27, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Sun, G. Novel Refreshable N-Halamine Polymeric Biocides: Grafting Hydantoin-Containing Monomers onto High Performance Fibers by a Continuous Process. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 88, 1032–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mella, M.; Mollica, L.; Izzo, L. Influence of Charged Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonds in Weak Polyelectrolytes: A Monte Carlo Study of Flexible and Extendible Polymeric Chains in Solution and near Charged Spheres. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2015, 53, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mella, M.; Izzo, L. Structural Properties of Hydrophilic Polymeric Chains Bearing Covalently-Linked Hydrophobic Substituents: Exploring the Effects of Chain Length, Fractional Loading and Hydrophobic Interaction Strength with Coarse Grained Potentials and Monte Carlo Simulations. Polymer (Guildf). 2010, 51, 3582–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, L.; Matrella, S.; Mella, M.; Benvenuto, G.; Vigliotta, G. Escherichia Coli as a Model for the Description of the Antimicrobial Mechanism of a Cationic Polymer Surface: Cellular Target and Bacterial Contrast Response. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 15332–15343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanford Nanofabrication Facility Cleaving Wafers and Substrates Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IRoIXjxIcBQ.

- Xia, J.; Yu, J.; Lu, S.; Huang, Q.; Xie, C.; Wang, Z. Surface Morphology Evolution during Chemical Mechanical Polishing Based on Microscale Material Removal Modeling for Monocrystalline Silicon. Materials (Basel). 2022, 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyona, M.D. A Comprehensive Study of Spin Coating as a Thin Film Deposition Technique and Spin Coating Equipment. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 2, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mella, M.; Tagliabue, A.; Vaghi, S.; Izzo, L. Evidences for Charged Hydrogen Bonds on Surfaces Bearing Weakly Basic Pendants: The Case of PMMA–Ran–PDMAEMA Polymeric Films. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 620, 126525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extrand, C.W. Spin Coating of Very Thin Polymer Films. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1994, 34, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerhofer, D. Characteristics of Resist Films Produced by Spinning. J. Appl. Phys. 1978, 49, 3993–3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koryta, J. Diffusion. Mass Transfer in Fluid Systems; Cambridge university press, 1985; Vol. 194; ISBN 0521871212.

- Bornside, D.E.; Macosko, C.W.; Scriven, L.E. Spin Coating of a PMMA/Chlorobenzene Solution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1991, 138, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.B.; Underhill, P.; Torkelson, J.M. Spin Coating of Thin and Ultrathin Polymer Films. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1998, 38, 2039–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank, D.D. Vapor Pressure of Chloroform Available online: http://www.ddbst.com/en/EED/PCP/VAP_C47.php.

- Chang, C.C.; Pai, C.L.; Chen, W.C.; Jenekhe, S.A. Spin Coating of Conjugated Polymers for Electronic and Optoelectronic Applications. Thin Solid Films 2005, 479, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallini, M.; Albonetti, C.; Biscarini, F. Nanopatterning Soluble Multifunctional Materials by Unconventional Wet Lithography. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 1043–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sader, J.E.; Chon, J.W.M.; Mulvaney, P. Calibration of Rectangular Atomic Force Microscope Cantilevers. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1999, 70, 3967–3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolyakov, G.; Formosa-Dague, C.; Severac, C.; Duval, R.E.; Dague, E. High Speed Indentation Measures by FV, QI and QNM Introduce a New Understanding of Bionanomechanical Experiments. Micron 2016, 85, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, R. Nanomechanical Mapping of Soft Materials with the Atomic Force Microscope: Methods, Theory and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 5850–5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappella, B.; Dietler, G. Force-Distance Curves by Atomic Force Microscopy. Surf. Sci. Rep. 1999, 34, 1–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiodini, S.; D’Avino, G.; Muccioli, L.; Bartolini, L.; Gentili, D.; Toffanin, S.; Albonetti, C. Self-Organization of Complete Organic Monolayers via Sequential Post-Deposition Annealing. Prog. Org. Coatings 2020, 138, 105408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Costa, N.P.; Hoh, J.H. Calibration of Optical Lever Sensitivity for Atomic Force Microscopy. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1995, 66, 5096–5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruker Corporation JPK Bio-Compatible Glue Available online: https://www.bruker.com/en/products-and-solutions/microscopes/bioafm/bioafm-accessories/jpk-bio-compatible-glue.html.

- Nečas, D.; Klapetek, P. Gwyddion: An Open-Source Software for SPM Data Analysis. Cent. Eur. J. Phys. 2012, 10, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualtieri, E.; Pugno, N.; Rota, A.; Spagni, A.; Lepore, E.; Valeri, S. Role of Roughness Parameters on the Tribology of Randomly Nano-Textured Silicon Surface. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2011, 11, 9244–9250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technologies, P. Abrasive Grinding Paper; 2011.

- Gadelmawla, E.S.; Koura, M.M.; Maksoud, T.M.A.; Elewa, I.M.; Soliman, H.H. Roughness Parameters. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2002, 123, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagnall, H. Exploring Surface Texture; Rank Taylor Hobson, 1986; ISBN 090192007X.

- De, R.R.L.; Albuquerque, D.A.C.; Cruz, T.G.S.; Yamaji, F.M.; Leite, F.L. Measurement of the Nanoscale Roughness by Atomic Force Microscopy: Basic Principles and Applications. In Atomic Force Microscopy - Imaging, Measuring and Manipulating Surfaces at the Atomic Scale; Bellitto, V., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2012; p. Ch. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, G.J.; Sedin, D.L.; Rowlen, K.L. Surface Roughness by Contact versus Tapping Mode Atomic Force Microscopy. Langmuir 1999, 15, 1429–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wallace, W.E. Characterization of Planarity of Polymer Thin Films on Rough Surfaces. Scatt. Surf. Rough. II 1998, 3426, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garoff, S.; Sirota, E.B.; Sinha, S.K.; Stanley, H.B. The Effects of Substrate Roughness on Ultrathin Water Films. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 7505–7515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Chou, F. Complete Analytical Solutions of Film Planarization during Spin Coating. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1999, 146, 3819–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Precision Devices, I. Surface Roughness Terminology and Parameters Available online: www.predev.com/pdffiles/surface_roughness_terminology_and_parameters.pdf.

- Wei, J.; Verhaar, T.M.; Sarro, P.M. Pattern Transfer on a Vertical Cavity Sidewall Using SU8. J. Micromechanics Microengineering 2009, 19, 74018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillwagon, L.E.; Larson, R.G.; Taylor, G.N. Planarization of Substrate Topography by Spin Coating. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1987, 134, 2030–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Tsarkova, L.A. Surface Roughness-Mediated Ordering in Block Copolymer Films toward Spatially Controlled Patterns. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 6840–6848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Yu, X.; Jin, Y. Considering Surface Roughness Effects in a Triangular Pore Space Model for Unsaturated Hydraulic Conductivity. Vadose Zo. J. 2015, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Grant Willson Spincoating. Available online: https://willson.cm.utexas.edu/Research/Sub_Files/Planarization/simulation.php (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Valle, F.; Brucale, M.; Chiodini, S.; Bystrenova, E.; Albonetti, C. Nanoscale Morphological Analysis of Soft Matter Aggregates with Fractal Dimension Ranging from 1 to 3. Micron 2017, 100, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, C.; Minier, J.P.; Lefèvre, G. Numerical Study on the Adhesion and Reentrainment of Nondeformable Particles on Surfaces: The Role of Surface Roughness and Electrostatic Forces. Langmuir 2012, 28, 438–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Hwu, J.; Liu, Y.; Gauzner, G.; Lee, K.; Kuo, D. Study of Spin-Coated Resist Coverage on Nanoscale Topography Using Spectroscopic Ellipsometry. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110, 14303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D. Measuring the Elastic Modulus of Polymers Using the Atomic Force Microscope. 2010, 43.

- Olubowale, O.H.; Biswas, S.; Azom, G.; Prather, B.L.; Owoso, S.D.; Rinee, K.C.; Marroquin, K.; Gates, K.A.; Chambers, M.B.; Xu, A.; et al. “may the Force Be with You!” Force-Volume Mapping with Atomic Force Microscopy. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 25860–25875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franz, C.M.; Taubenberger, A.; Puech, P.H.; Muller, D.J. Studying Integrin-Mediated Cell Adhesion at the Single-Molecule Level Using AFM Force Spectroscopy. Sci. STKE 2007, 2007, pl5–pl5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Yu, Z.; Wei, Y. Measurement of Nanoindentation Properties of Polymers Considering Adhesion Effects between AFM Sharp Indenter and Material. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2020, 34, 1591–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, S.; Trost, C.O.W.; Kreiml, P.; Cordill, M.J. Accurate Measurement of Thin Film Mechanical Properties Using Nanoindentation. J. Mater. Res. 2022, 37, 1373–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokukin, M.E.; Sokolov, I. On the Measurements of Rigidity Modulus of Soft Materials in Nanoindentation Experiments at Small Depth. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 4277–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranchida, D.; Piccarolo, S.; Soliman, M. Nanoscale Mechanical Characterization of Polymers by AFM Nanoindentations: Criticalr Approach to the Elastic Characterization. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 4547–4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griepentrog, M.; Krämer, G.; Cappella, B. Comparison of Nanoindentation and AFM Methods for the Determination of Mechanical Properties of Polymers. Polym. Test. 2013, 32, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruker QITM Makes AFM Easy - Perfect for Non-Experts, Beginners and Occasional Users. Available online: https://www.jpk.com/products/atomic-force-microscopy/qi-mode/pid4448 (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Butt, H.-J.; Cappella, B.; Kappl, M. Force Measurements with the Atomic Force Microscope: Technique, Interpretation and Applications. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2005, 59, 1–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.R.; Raghunathan, V.K.; Garland, S.P.; Morgan, J.T.; Russell, P.; Murphy, C.J. Automated AFM Force Curve Analysis for Determining Elastic Modulus of Biomaterials and Biological Samples. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2014, 37, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, C.M.; Vogt, B.D.; Harrison, C.; Julthongpiput, D.; Huang, R. Elastic Moduli of Ultrathin Amorphous Polymer Films. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 5095–5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassous, E. Fabrication of Novel Three-Dimensional Microstructures by the Anisotropic Etching of (100) and (110) Silicon. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 1978, 25, 1178–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, K.; Satomi, N.; Sasaki, S. Elastic Modulus of Polystyrene Film from near Surface to Bulk Measured by Nanoindentation Using Atomic Force Microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 89, 31925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, K.; Yang, F.; Druffel, T.; Grulke, E.A. Nanoindentation Behavior of Ultrathin Polymeric Films. Polymer (Guildf). 2005, 46, 11768–11772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oommen, B.; Van Vliet, K.J. Effects of Nanoscale Thickness and Elastic Nonlinearity on Measured Mechanical Properties of Polymeric Films. Thin Solid Films 2006, 513, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, E.K.; Horkay, F.; Maresca, J.; Kachar, B.; Chadwick, R.S. Determination of Elastic Moduli of Thin Layers of Soft Material Using the Atomic Force Microscope. Biophys. J. 2002, 82, 2798–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, J.M.; Stafford, C.M.; Vogt, B.D. Impact of Molecular Mass on the Elastic Modulus of Thin Polystyrene Films. Polymer (Guildf). 2010, 51, 4211–4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, W.; Fujie, T.; Nakajima, K. Contact-Induced Stiffening in Ultrathin Amorphous Polystyrene Films. Polymer (Guildf). 2018, 153, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viville, P.; Deffieux, A.; Schappacher, M.; Leclère, P.; Brédas, J.L.; Lazzaroni, R. Influence of Tip Indentation Depth on the Adhesive Behavior of Viscoelastic Polydimethylsiloxane Networks Studied by Atomic Force Microscopy. Macromol. Symp. 2001, 167, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, C.A.; Lee, L.T.; Galembeck, F. Surface Mechanical Properties of Thin Polymer Films Investigated by AFM in Pulsed Force Mode. Langmuir 2009, 25, 9938–9946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisenhorn, A.L.; Hansma, P.K.; Albrecht, T.R.; Quate, C.F. Forces in Atomic Force Microscopy in Air and Water. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1989, 54, 2651–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Takahara, A.; Kajiyama, T. Film Thickness Dependence of the Surface Structure of Immiscible Polystyrene/Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) Blends. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 3232–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Turner, K.T. Measurement of the Strength and Range of Adhesion Using Atomic Force Microscopy. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 2016, 9, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hu, H.; Li, S.; He, Y. Evolution of Mechanical Properties of Polypropylene Separator in Liquid Electrolytes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 46441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Mukherjee, M. Swelling Dynamics of Ultrathin Polymer Films. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 8728–8731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogieglo, W.; Wormeester, H.; Eichhorn, K.J.; Wessling, M.; Benes, N.E. In Situ Ellipsometry Studies on Swelling of Thin Polymer Films: A Review. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2015, 42, 42–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benaglia, S.; Drakopoulou, S.; Biscarini, F.; Garcia, R. In Operando Nanomechanical Mapping of PEDOT:PSS Thin Films in Electrolyte Solutions with Bimodal AFM. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 14146–14154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasil’eva, V.I.; Kranina, N.A.; Malykhin, M.D.; Akberova, E.M.; Zhiltsova, A. V. The Surface Inhomogeneity of Ion-Exchange Membranes by SEM and AFM Data. J. Surf. Investig. 2013, 7, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metze, F.K.; Sant, S.; Meng, Z.; Klok, H.A.; Kaur, K. Swelling-Activated, Soft Mechanochemistry in Polymer Materials. Langmuir 2023, 39, 3546–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccurso, E.; Graf, K. Nanostructuring Effect of Plasma and Solvent Treatment on Polystyrene. Langmuir 2004, 20, 11183–11190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.G.; Raybin, J.G.; Ansay, G.E.; Sibener, S.J. Spatiotemporal Mapping of Hole Nucleation and Growth during Block Copolymer Terracing with High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 5644–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| A(BC)2 data |

|---|

|

T = 298.15 K R = 82.06 atm·cm3·mol-1·K-1 |

|

Dg = 0.106·10-6 cm2·s-1 a νg = 0.1553 cSt = 0.1553·10-2 cm2·s-1 b PCHCl3 = 26.271 kPa ≈ 0.26 atm c MCHCl3 = 119.38 g·mol-1 d ρ0 = 1.49 g·cm-3 e C = 0.5474 f |

| ω (rpm) | Sub | Rq (nm) | Wa (nm) | λa (µm) | Rq1 (nm) | sh (nm) | P (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3000 | CMP | 0.15 ± 0.025 | / | / | / | ≈ 0.14 | ≈ 100 |

| 3200 | CMP | 0.19 ± 0.125 | / | / | / | ≈ 0.19 | ≈ 100 |

| 3500 | MP | 6.4 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 1.9 | 0.60 ± 0.15 | 4.1 ± 0.8 | 18 ± 3 | 49 ± 17 |

| 3750 | MP | 4.5 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 0.98 ± 0.36 | 3.0 ± 1.3 | 13 ± 3 | 63 ± 25 |

| 4000 | MP | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.65 ± 0.29 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 9.3 ± 0.1 | 73 ± 13 |

| Sample | δ (nm) | Fmax (nN) | Fadh (nN) | Wsep (·10-17 J) | E (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP-SC | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 121 ± 5 | 14 ± 1 | 6.8 ± 0.7 | 12 ± 6 |

| CMP-SC | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 257 ± 4 | 16.8 ± 1.6 | 8 ± 1 | 12 ± 4 |

| CMP-DC | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 120.4 ± 0.6 | 7.7 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.8 | 3.2 ± 0.5 |

| S-S | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 240 ± 1 | 8.2 ± 1.6 | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 2.8 ± 0.7 |

| Sample | t0 (h) | ES (GPa) | Fadh (nN) | Wadh (·10-17 J) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP-SC | 0.33 ± 0.08 | 0.91 ± 0.09 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

| CMP-SC | 0.41 ± 0.13 | 0.97 ± 0.15 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.3 |

| CMP-DC | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 0.24 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.5 |

| S-S | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 0.044 ± 0.005 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).