Submitted:

20 December 2023

Posted:

20 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. INTRODUCTION

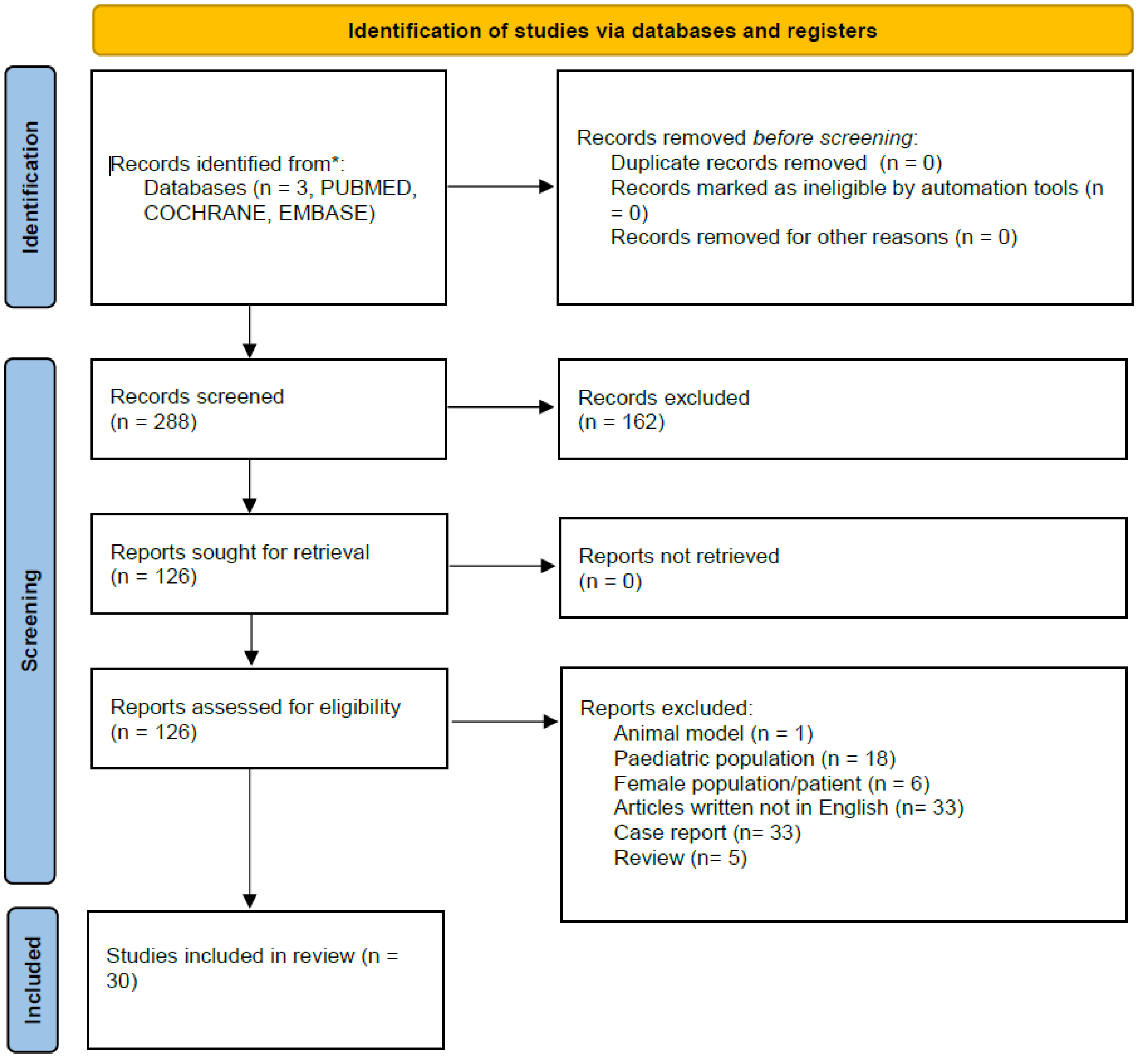

1. MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. RESULTS

3.1. CONSERVATIVE TREATMENTS

3.1.1. Topical corticosteroids

3.2.2. The Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) for lichen sclerosus (LS)

3.2.3. PhimoStop™

1. Surgical treatments

4.1. Circumcision

4.1.1. Techniques of circumcision

4.1.2. Circumcision in elderly patients

4.1.3. Effect of circumcision on sexual function

4.2. Preputial sparing techniques

4.2.1. Prepuce-sparing plasty and simple running suture

4.2.2. Y – V Preputioplasty (Figure 4)

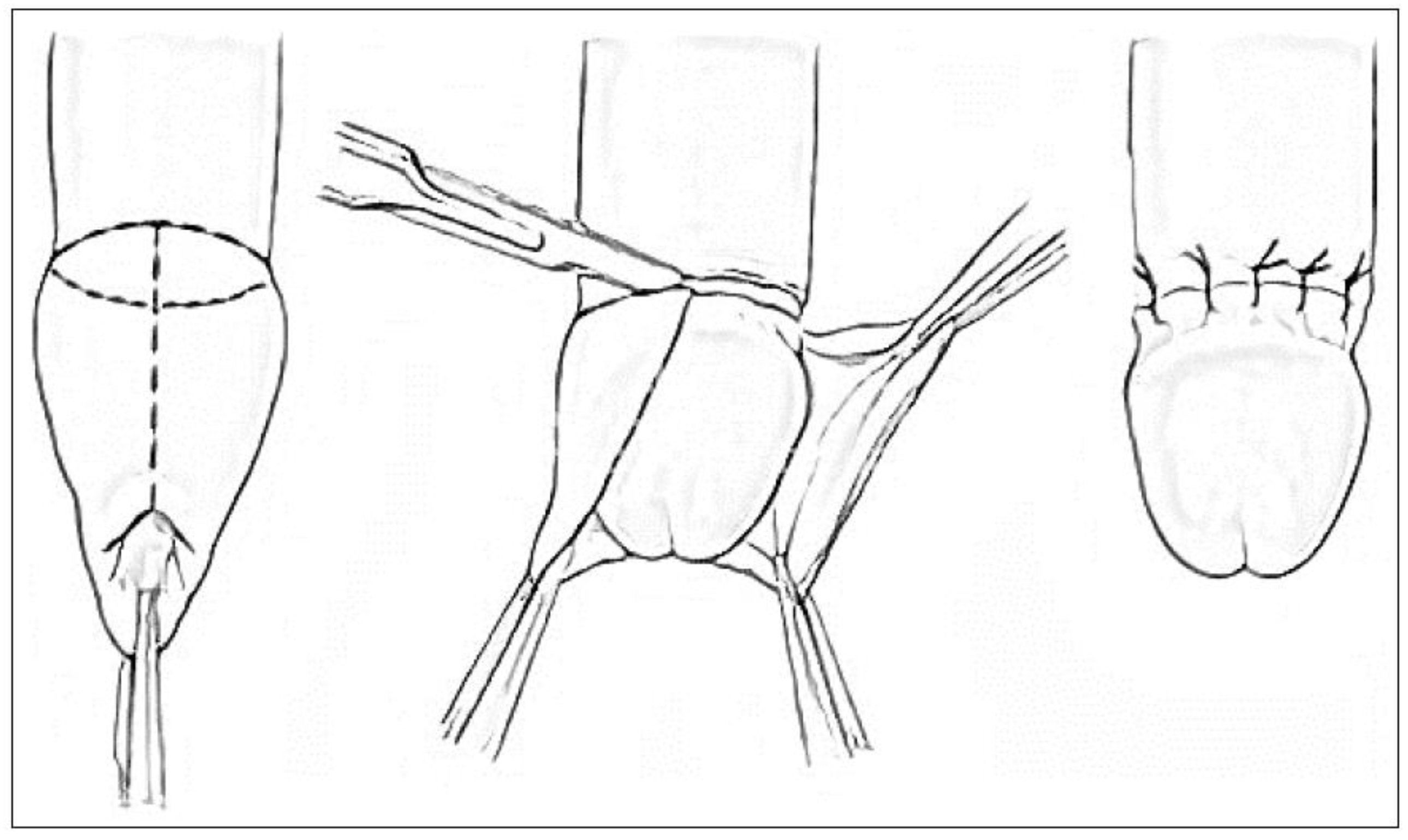

4.2.3. Heineke-Mikulicz Preputioplasty (Figure 5)

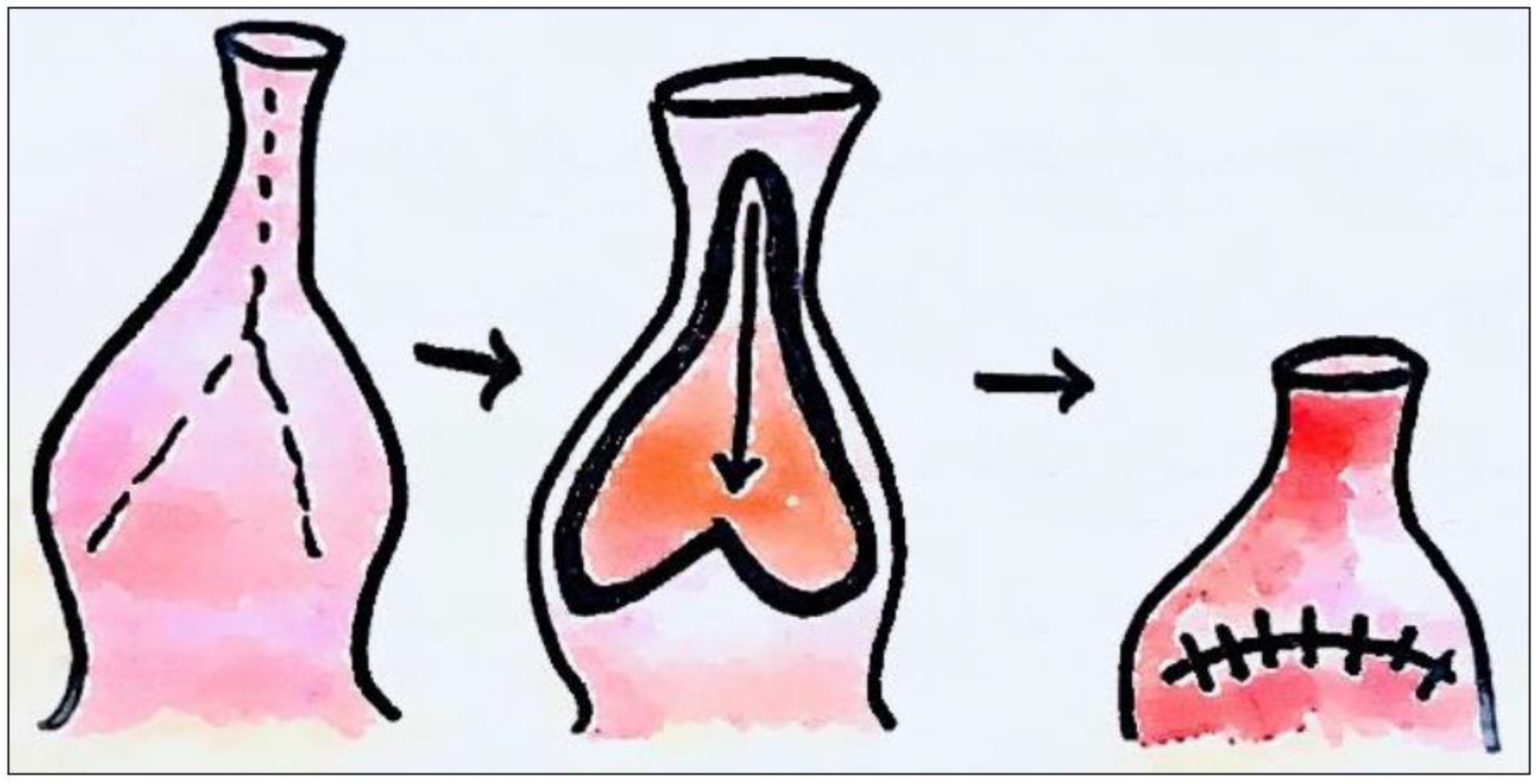

4.3. In-situ devices

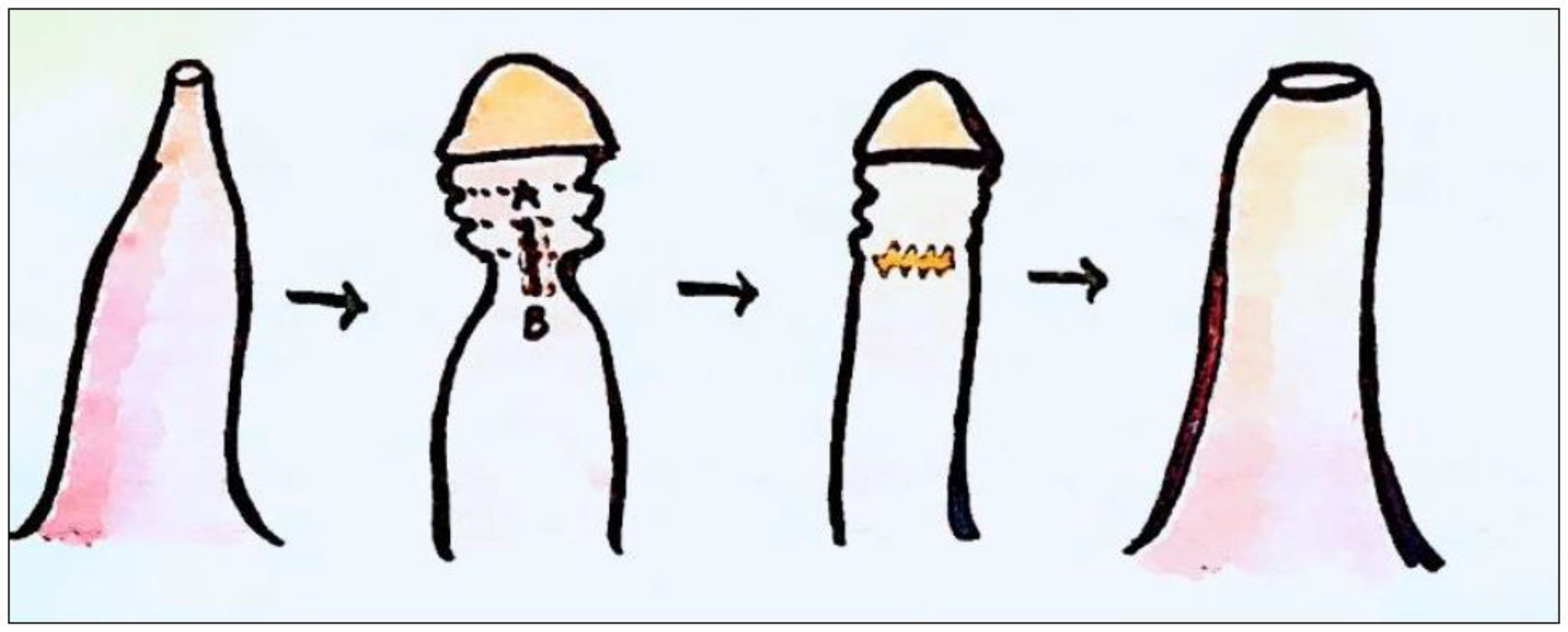

4.3.1. The PrePex device (Figure 6)

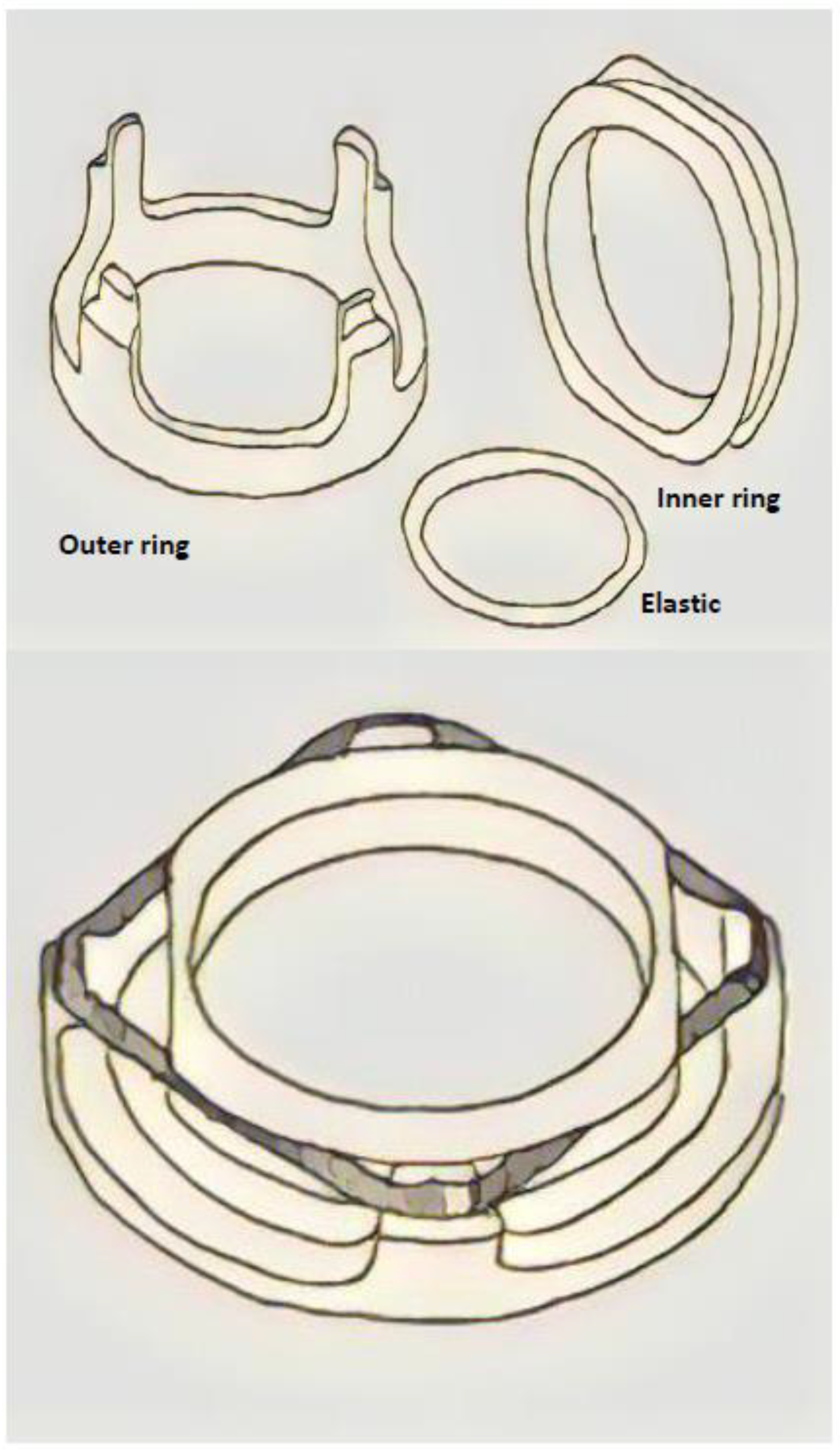

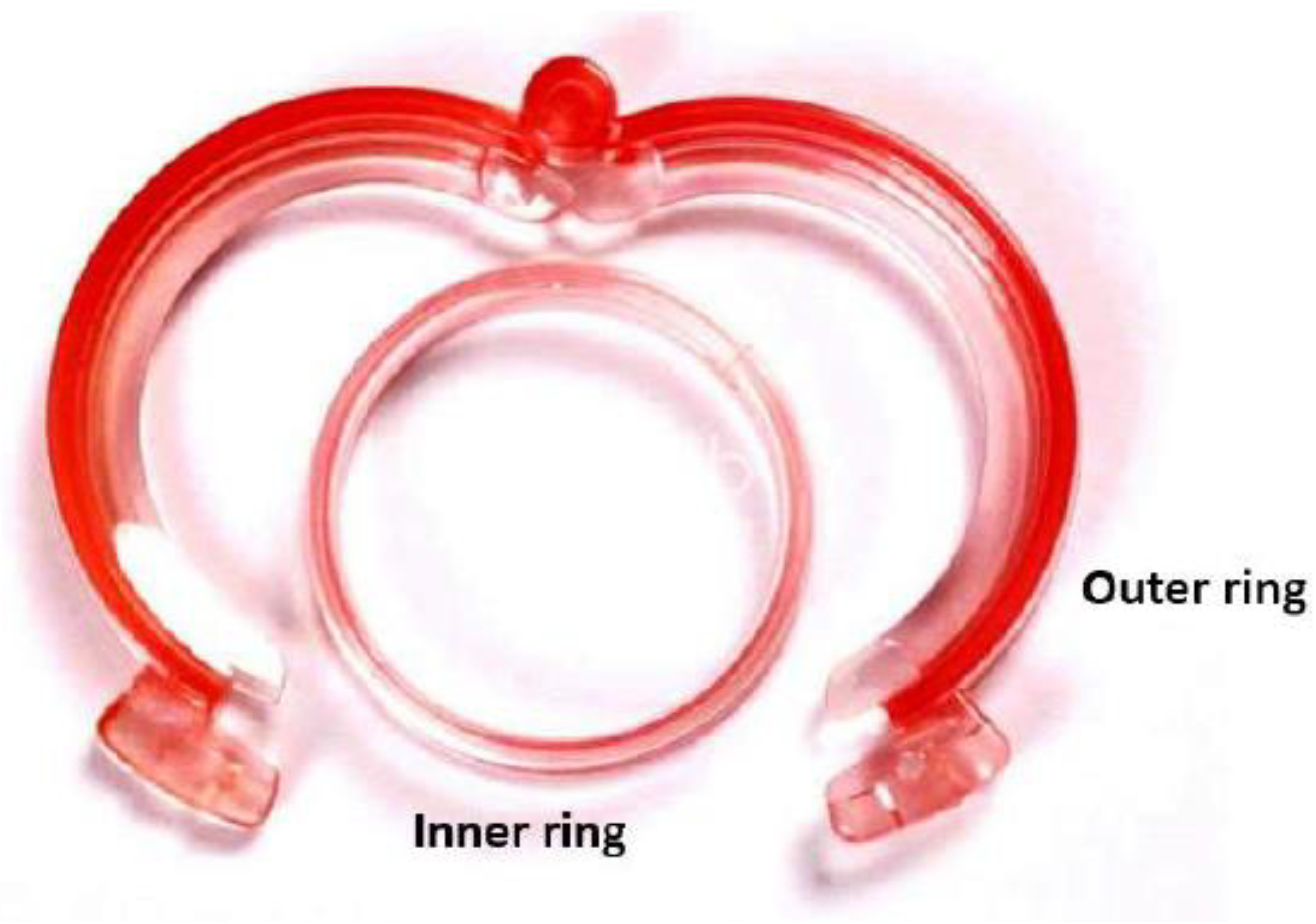

4.3.2. The Shang Ring™ device (Figure 7)

1. CONCLUSIONS

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- L. S. Palmer and et al., Management of abnormalities of the external genitalia in boys. In: CampbellWalsh Urology. , vol. 11th ed. Vol. 4. 2016.

- D. GAIRDNER, “The fate of the foreskin, a study of circumcision.,” Br Med J, vol. 2, no. 4642, pp. 1433–7, illust, Dec. 1949. [CrossRef]

- M. Czajkowski et al., “Lichen Sclerosus and Phimosis - Discrepancies Between Clinical and Pathological Diagnosis and Its Consequences.,” Urology, vol. 148, pp. 274–279, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Korkes, J. L. Silva, and A. C. L. Pompeo, “Circumcisions for medical reasons in the Brazilian public health system: epidemiology and trends.,” Einstein (Sao Paulo), vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 342–6, 2012. [CrossRef]

- C. Radmayr and et al., “EAU Guidelines on Paediatric Urology, 2022,” 2022.

- M. Carilli et al., “Can circumcision be avoided in adult male with phimosis? Results of the PhimoStopTM prospective trial.,” Transl Androl Urol, vol. 10, no. 11, pp. 4152–4160, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. M. Shabanzadeh, S. Clausen, K. Maigaard, and M. Fode, “Male Circumcision Complications - A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression.,” Urology, vol. 152, pp. 25–34, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Asimakopoulos, B. Iorio, G. Vespasiani, V. Cervelli, and E. Spera, “Autologous split-thickness skin graft for penile coverage in the treatment of buried (trapped) penis after radical circumcision,” BJU Int, vol. 110, no. 4, pp. 602–606, Aug. 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Krill, L. S. Palmer, and J. S. Palmer, “Complications of circumcision.,” ScientificWorldJournal, vol. 11, pp. 2458–68, 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. Abdulwahab-Ahmed and I. A. Mungadi, “Techniques of male circumcision.,” J Surg Tech Case Rep, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1–7, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Asimakopoulos, B. Iorio, G. Vespasiani, V. Cervelli, and E. Spera, “Autologous split-thickness skin graft for penile coverage in the treatment of buried (trapped) penis after radical circumcision.,” BJU Int, vol. 110, no. 4, pp. 602–6, Aug. 2012. [CrossRef]

- P. Pedersini, F. Parolini, A. L. Bulotta, and D. Alberti, “‘Trident’ preputial plasty for phimosis in childhood.,” J Pediatr Urol, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 278.e1-278.e4, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Benson and M. K. Hanna, “Prepuce sparing: Use of Z-plasty for treatment of phimosis and scarred foreskin.,” J Pediatr Urol, vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 545.e1-545.e4, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A.C. Peterson, B. D. Joyner, and R. C. Allen, “Plastibell template circumcision: a new technique.,” Urology, vol. 58, no. 4, pp. 603–4, Oct. 2001. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Page et al., “The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews.,” BMJ, vol. 372, p. n71, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Xu, K. Mishra, and L. C. Zhao, “Heineke-Mikulicz Preputioplasty: Surgical Technique and Outcomes.,” Urology, vol. 166, pp. 271–276, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Nabavizadeh, K. D. Li, N. Hakam, N. M. Shaw, M. S. Leapman, and B. N. Breyer, “Incidence of circumcision among insured adults in the United States.,” PLoS One, vol. 17, no. 10, p. e0275207, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Monarca, M. I. Rizzo, L. Quadrini, G. Sanese, G. Prezzemoli, and N. Scuderi, “Prepuce-sparing plasty and simple running suture for phimosis.,” G Chir, vol. 34, no. 1–2, pp. 38–41, 2013.

- M. Siev, M. Keheila, P. Motamedinia, and A. Smith, “Indications for adult circumcision: a contemporary analysis.,” Can J Urol, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 8204–8, Apr. 2016.

- P. Carmine et al., “Circumferential dissection of deep fascia as ancillary technique in circumcision: is it possible to correct phimosis increasing penis size?,” BMC Urol, vol. 21, no. 1, p. 15, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Rajan, S. A. McNeill, and K. J. Turner, “Is frenuloplasty worthwhile? A 12-year experience.,” Ann R Coll Surg Engl, vol. 88, no. 6, pp. 583–4, Oct. 2006. [CrossRef]

- F. Casabona, I. Gambelli, F. Casabona, P. Santi, G. Santori, and I. Baldelli, “Autologous platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in chronic penile lichen sclerosus: the impact on tissue repair and patient quality of life.,” Int Urol Nephrol, vol. 49, no. 4, pp. 573–580, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. T. D’Arcy and S. Q. Jaffry, “A review of 100 consecutive sutureless child and adult circumcisions.,” Ir J Med Sci, vol. 180, no. 1, pp. 51–3, Mar. 2011. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Fink, C. C. Carson, and R. F. DeVellis, “Adult circumcision outcomes study: effect on erectile function, penile sensitivity, sexual activity and satisfaction.,” J Urol, vol. 167, no. 5, pp. 2113–6, May 2002.

- N. P. Munro, H. Khan, N. A. Shaikh, I. Appleyard, and P. Koenig, “Y-V preputioplasty for adult phimosis: a review of 89 cases.,” Urology, vol. 72, no. 4, pp. 918–20, Oct. 2008. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Barone et al., “Simplifying the ShangRing technique for circumcision in boys and men: use of the no-flip technique with randomization to removal at 7 days versus spontaneous detachment.,” Asian J Androl, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 324–331, 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Gu et al., “Introducing the QuillTM device for modified sleeve circumcision with subcutaneous suture: a retrospective study of 70 cases.,” Urol Int, vol. 94, no. 3, pp. 255–61, 2015. [CrossRef]

- G. Kigozi et al., “The safety and acceptance of the PrePex device for non-surgical adult male circumcision in Rakai, Uganda. A non-randomized observational study.,” PLoS One, vol. 9, no. 8, p. e100008, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Q. Su et al., “A Comparative Study on the Clinical Efficacy of Modified Circumcision and Two Other Types of Circumcision.,” Urol J, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 556–560, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Jasaitiene et al., “Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus in pediatric and adult male patients with congenital and acquired phimosis.,” Medicina (Kaunas), vol. 44, no. 6, pp. 460–6, 2008.

- X. Wu et al., “A report of 918 cases of circumcision with the Shang Ring: comparison between children and adults.,” Urology, vol. 81, no. 5, pp. 1058–63, May 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. Mu, L. Fan, D. Liu, and D. Zhu, “A Comparative Study on the Efficacy of Four Types of Circumcision for Elderly Males with Redundant Prepuce.,” Urol J, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 301–305, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Shen et al., “A Comparative Study on the Clinical Efficacy of Two Different Disposable Circumcision Suture Devices in Adult Males.,” Urol J, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 5013–5017, Aug. 2017.

- P. Ronchi, S. Manno, and L. Dell’Atti, “<p>Technology Meets Tradition: CO2 Laser Circumcision versus Conventional Surgical Technique</p>,” Res Rep Urol, vol. Volume 12, pp. 255–260, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z.-L. Jiang, C.-W. Sun, J. Sun, G.-F. Shi, and H. Li, “Subcutaneous tissue-sparing dorsal slit with new marking technique: A novel circumcision method.,” Medicine, vol. 98, no. 16, p. e15322, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- B.-D. Lv et al., “Disposable circumcision suture device: clinical effect and patient satisfaction.,” Asian J Androl, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 453–6, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang et al., “Application of a novel disposable suture device in circumcision: a prospective non-randomized controlled study.,” Int Urol Nephrol, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 465–73, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Han, D.-W. Xie, X.-G. Zhou, and X.-D. Zhang, “Novel penile circumcision suturing devices versus the shang ring for adult male circumcision: a prospective study.,” Int Braz J Urol, vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 736–745, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J.-H. Lei et al., “Circumcision with ‘no-flip Shang Ring’ and ‘Dorsal Slit’ methods for adult males: a single-centered, prospective, clinical study.,” Asian J Androl, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 798–802, 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang et al., “Safety and efficacy of a novel disposable circumcision device: a pilot randomized controlled clinical trial at 2 centers.,” Med Sci Monit, vol. 20, pp. 454–62, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- P. Malone and H. Steinbrecher, “Medical aspects of male circumcision.,” BMJ, vol. 335, no. 7631, pp. 1206–90, Dec. 2007. [CrossRef]

- C.-C. Chi, G. Kirtschig, M. Baldo, F. Brackenbury, F. Lewis, and F. Wojnarowska, “Topical interventions for genital lichen sclerosus.,” Cochrane Database Syst Rev, vol. 2011, no. 12, p. CD008240, Dec. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu et al., “A Prospective, Randomized Controlled Trial of Circumcision in Adult Males Using the CO 2 Laser: Modified Technique Compared with the Conventional Dorsal-Slit Technique,” Photomed Laser Surg, vol. 31, no. 9, pp. 422–427, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Neill, F. M. Lewis, F. M. Tatnall, N. H. Cox, and British Association of Dermatologists, “British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of lichen sclerosus 2010.,” Br J Dermatol, vol. 163, no. 4, pp. 672–82, Oct. 2010. [CrossRef]

- G. Moreno, J. Corbalán, B. Peñaloza, and T. Pantoja, “Topical corticosteroids for treating phimosis in boys.,” Cochrane Database Syst Rev, no. 9, p. CD008973, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Liu, J. Yang, Y. Chen, S. Cheng, C. Xia, and T. Deng, “Is steroids therapy effective in treating phimosis? A meta-analysis.,” Int Urol Nephrol, vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 335–42, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Kikiros CS, Beasley SW, and Woodward AA, “The response of phimosis to local steroid application. ,” Pediatr Surg Int , vol. 8, pp. 329–332, 1993.

- S. Shikanov et al., “Knotless Closure of the Collecting System and Renal Parenchyma with a Novel Barbed Suture During Laparoscopic Porcine Partial Nephrectomy,” J Endourol, vol. 23, no. 7, pp. 1157–1160, Jul. 2009. [CrossRef]

- F. N. Elmasalme, S. A. Matbouli, and M. S. Zuberi, “Use of tissue adhesive in the closure of small incisions and lacerations.,” J Pediatr Surg, vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 837–8, Jun. 1995. [CrossRef]

- M. Czajkowski et al., “Male Circumcision Due to Phimosis as the Procedure That Is Not Only Relieving Clinical Symptoms of Phimosis But Also Improves the Quality of Sexual Life.,” Sex Med, vol. 9, no. 2, p. 100315, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Mutabazi et al., “One-arm, open-label, prospective, cohort field study to assess the safety and efficacy of the PrePex device for scale-up of nonsurgical circumcision when performed by nurses in resource-limited settings for HIV prevention.,” J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, vol. 63, no. 3, pp. 315–22, Jul. 2013. [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Advantage/Disavantage | Side Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Phimostop™[Carilli M et al,5] | Shaped silicone tuboids of increasing size to obtain a non-forced dilation of the prepuce | Scarce: discomfort with larger tuboid size |

| Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) [Casabona F et al, 20] | Reduction/disappearance of symptoms and/or of lichen sclerosus | Risk of malignant disease (actually no study demonstrates that PRP promotes hyperplasia, carcinogenesis, or tumor growth) |

| Topical corticosteroids [Moreno G et al, Liu J et al] | Complete or partial clinical resolution of phimosis (long – term follow – up not available) | These drugs could induce skin atrophy, telangiectasia and immunosuppression (increasing the risk of malignancy) |

| Potency | Topical corticosteroids |

|---|---|

| Very potent | Clobetasol propionate 0.05% Diflucortolone valerate 0.3% |

| Potent | Bethametasone dipropionate 0.05% to 0.064% Bethametasone valerate 0.1% to 0.12% Diflucortolone valerato 0.1% Hydrocortisone butyrate 0.1% Mometasone furoate 0.1% Triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% |

| Moderate | Betamethasone valerate 0.025% Clobetasone butyrate 0.05% |

| Mild | Hydrocortisone 0.1% to 2.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).