Submitted:

18 December 2023

Posted:

19 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Blood drawing and plasma prepatation

2.3. APOE genotyping

2.4. Quantification of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42

2.5. CSF analysis

2.6. Amyloid PET-CT acquisition and computing

2.6.1. [18F]flutemetamol PET-CT

2.6.2. [11C]PiB PET-CT

2.7. Basic characteristics

2.7.1. Characteristics of volunteers and patients

2.7.2. Characteristics of participants with amyloid measured through CSF or PET analysis

2.8. Statistical analysis

2.8.1. Gaussian mixture model (GMM)

2.8.2. Decision tree

2.8.3. ROC curve

2.8.4. Posttest probabilities

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Amyloid status

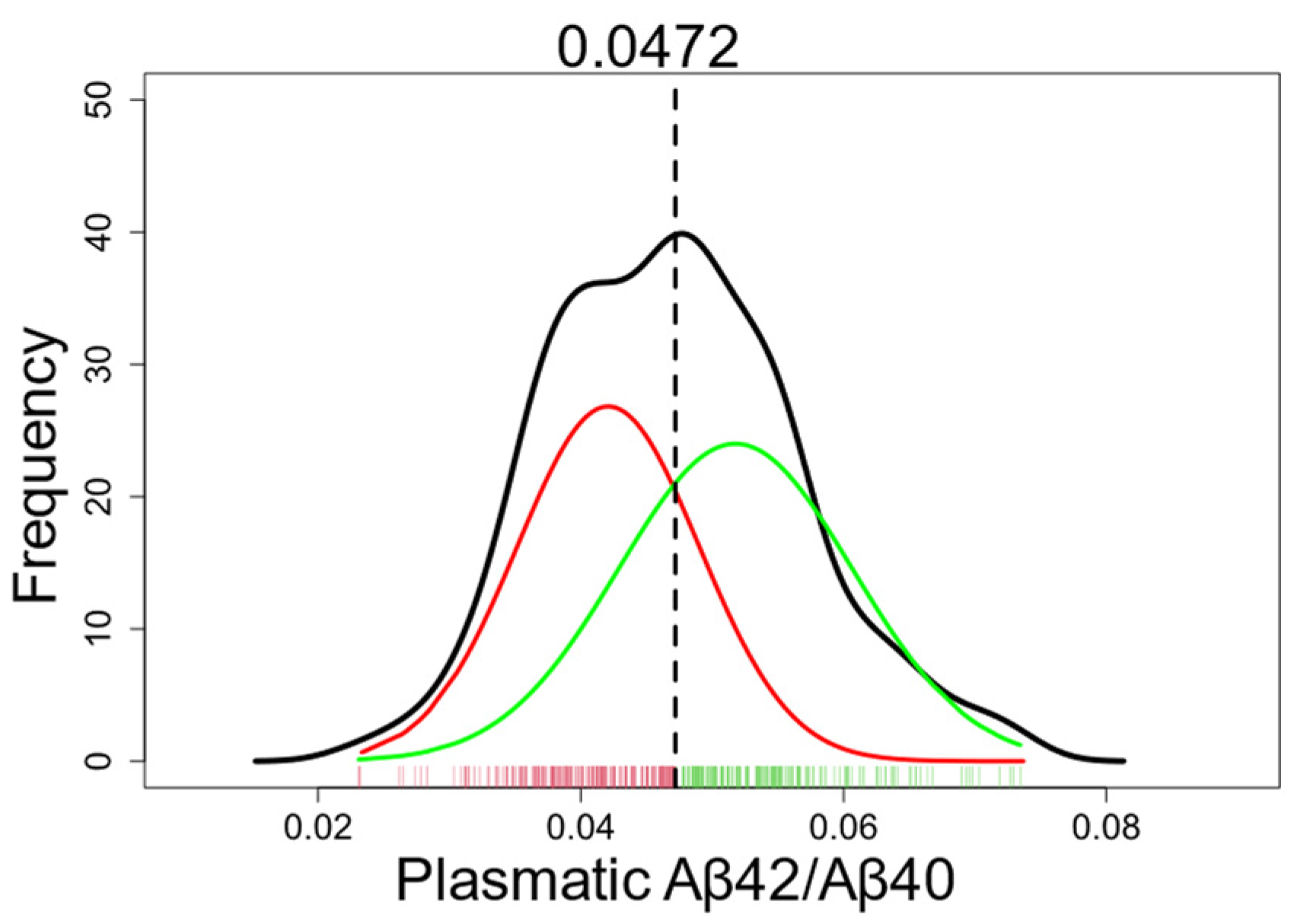

3.3. GMM-based classification of plasma Aβ

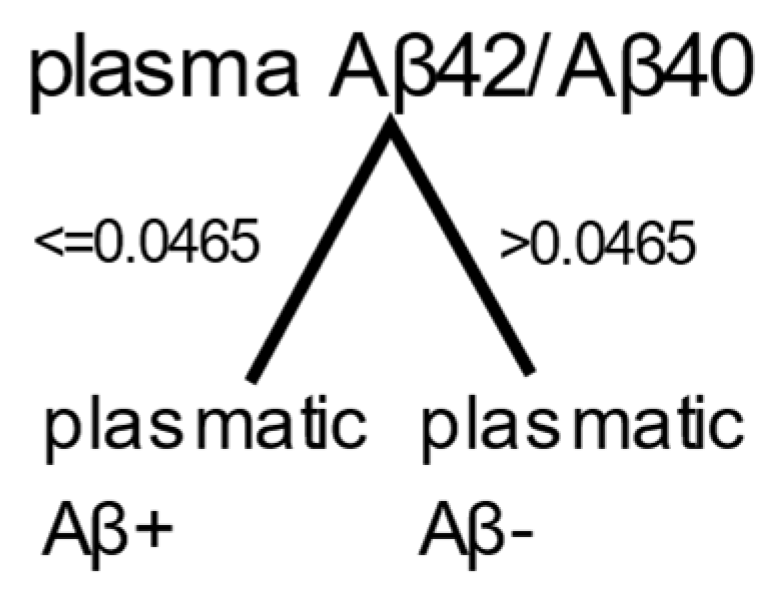

3.4. Decision tree

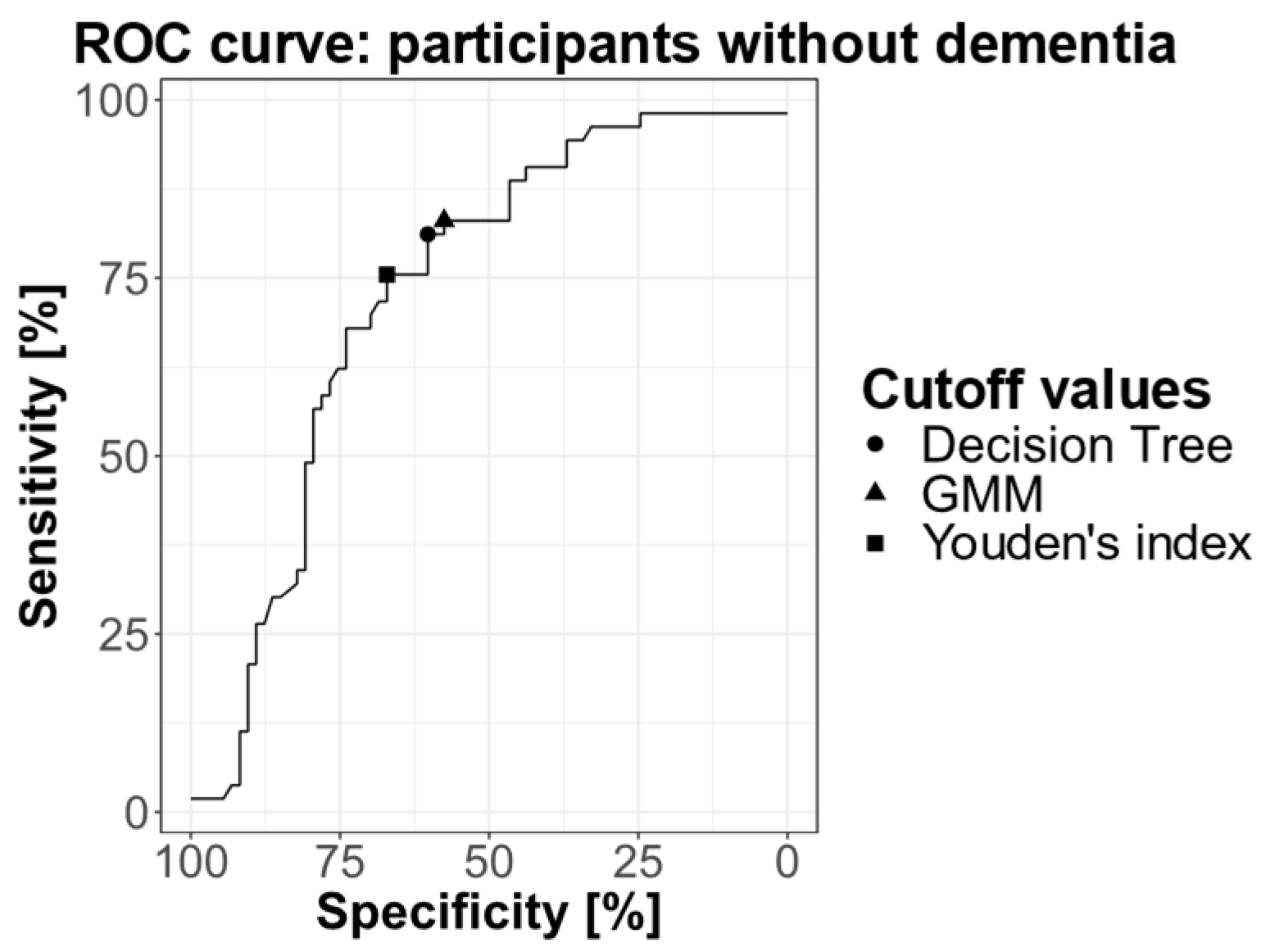

3.5. ROC curve

3.6. Posttest probabilities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hebert, L.E.; Weuve, J.; Scherr, P.A.; Evans, D.A. Alzheimer Disease in the United States (2010-2050) Estimated Using the 2010 Census. Neurology 2013, 80, 1778–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J.A.; Higgins, G.A. Alzheimer’s Disease: The Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis. Science 1992, 256, 184–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawuenyega, K.G.; Sigurdson, W.; Ovod, V.; Munsell, L.; Kasten, T.; Morris, J.C.; Yarasheski, K.E.; Bateman, R.J. Decreased Clearance of CNS β-Amyloid in Alzheimer’s Disease. Science 2010, 330, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, N.; Hesse, C.; Davidsson, P.; Minthon, L.; Wallin, A.; Winblad, B.; Vanderstichele, H.; Vanmechelen, E.; Blennow, K. Cerebrospinal Fluid 2-Amyloid(1-42) in Alzheimer Disease: Differences Between Early- and Late-Onset Alzheimer Disease and Stability During the Course of Disease. ARCH NEUROL 1999, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiltfang, J.; Esselmann, H.; Bibl, M.; Hüll, M.; Hampel, H.; Kessler, H.; Frölich, L.; Schröder, J.; Peters, O.; Jessen, F.; et al. Amyloid β Peptide Ratio 42/40 but Not Aβ42 Correlates with phospho-Tau in Patients with Low- and high-CSF Aβ40 Load. Journal of Neurochemistry 2007, 101, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanseeuw, B.J.; Betensky, R.A.; Jacobs, H.I.L.; Schultz, A.P.; Sepulcre, J.; Becker, J.A.; Cosio, D.M.O.; Farrell, M.; Quiroz, Y.T.; Mormino, E.C.; et al. Association of Amyloid and Tau With Cognition in Preclinical Alzheimer Disease: A Longitudinal Study. JAMA Neurol 2019, 76, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, C.R.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a Biological Definition of Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2018, 14, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donohue, M.C.; Sperling, R.A.; Petersen, R.; Sun, C.-K.; Weiner, M.W.; Aisen, P.S. for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Association Between Elevated Brain Amyloid and Subsequent Cognitive Decline Among Cognitively Normal Persons. JAMA 2017, 317, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.A.; Jang, Y.J.; Kim, M.K.; Lee, S.M.; Moon, S.Y. Promising Blood Biomarkers for Clinical Use in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Focused Update. J Clin Neurol 2022, 18, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, R.J.; Munsell, L.Y.; Morris, J.C.; Swarm, R.; Yarasheski, K.E.; Holtzman, D.M. Human Amyloid-β Synthesis and Clearance Rates as Measured in Cerebrospinal Fluid in Vivo. Nat Med 2006, 12, 856–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissin, D.M.; Kan, C.W.; Campbell, T.G.; Howes, S.C.; Fournier, D.R.; Song, L.; Piech, T.; Patel, P.P.; Chang, L.; Rivnak, A.J.; et al. Single-Molecule Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay Detects Serum Proteins at Subfemtomolar Concentrations. Nat Biotechnol 2010, 28, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verberk, I.M.W.; Slot, R.E.; Verfaillie, S.C.J.; Heijst, H.; Prins, N.D.; van Berckel, B.N.M.; Scheltens, P.; Teunissen, C.E.; van der Flier, W.M. Plasma Amyloid as Prescreener for the Earliest A Lzheimer Pathological Changes. Ann Neurol. 2018, 84, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Y.; Wang, B.; Guo, Q.; Miao, Y. Plasma Aβ as a Biomarker for Predicting Aβ-PET Status in Alzheimer’s Disease: a Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2022, 93, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janelidze, S.; Stomrud, E.; Palmqvist, S.; Zetterberg, H.; van Westen, D.; Jeromin, A.; Song, L.; Hanlon, D.; Tan Hehir, C.A.; Baker, D.; et al. Plasma β-Amyloid in Alzheimer’s Disease and Vascular Disease. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 26801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, A.; Kaneko, N.; Villemagne, V.L.; Kato, T.; Doecke, J.; Doré, V.; Fowler, C.; Li, Q.-X.; Martins, R.; Rowe, C.; et al. High Performance Plasma Amyloid-β Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease. Nature 2018, 554, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovod, V.; Ramsey, K.N.; Mawuenyega, K.G.; Bollinger, J.G.; Hicks, T.; Schneider, T.; Sullivan, M.; Paumier, K.; Holtzman, D.M.; Morris, J.C.; et al. Amyloid β Concentrations and Stable Isotope Labeling Kinetics of Human Plasma Specific to Central Nervous System Amyloidosis. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2017, 13, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, S.E.; Bollinger, J.G.; Ovod, V.; Mawuenyega, K.G.; Li, Y.; Gordon, B.A.; Holtzman, D.M.; Morris, J.C.; Benzinger, T.L.S.; Xiong, C.; et al. High-Precision Plasma β-Amyloid 42/40 Predicts Current and Future Brain Amyloidosis. Neurology 2019, 93, e1647–e1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giudici, K.V.; De Souto Barreto, P.; Guyonnet, S.; Li, Y.; Bateman, R.J.; Vellas, B. MAPT/DSA Group Assessment of Plasma Amyloid-β 42/40 and Cognitive Decline Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults. JAMA Netw Open 2020, 3, e2028634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verberk, I.M.W.; Hendriksen, H.M.A.; Van Harten, A.C.; Wesselman, L.M.P.; Verfaillie, S.C.J.; Van Den Bosch, K.A.; Slot, R.E.R.; Prins, N.D.; Scheltens, P.; Teunissen, C.E.; et al. Plasma Amyloid Is Associated with the Rate of Cognitive Decline in Cognitively Normal Elderly: The SCIENCe Project. Neurobiology of Aging 2020, 89, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, J.R.; Zimmer, J.A.; Evans, C.D.; Lu, M.; Ardayfio, P.; Sparks, J.; Wessels, A.M.; Shcherbinin, S.; Wang, H.; Monkul Nery, E.S.; et al. Donanemab in Early Symptomatic Alzheimer Disease: The TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023, 330, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyck, C.H.; Swanson, C.J.; Aisen, P.; Bateman, R.J.; Chen, C.; Gee, M.; Kanekiyo, M.; Li, D.; Reyderman, L.; Cohen, S.; et al. Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med 2023, 388, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. Mini-Mental State. Journal of Psychiatric Research 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villemagne, V.L.; Burnham, S.; Bourgeat, P.; Brown, B.; Ellis, K.A.; Salvado, O.; Szoeke, C.; Macaulay, S.L.; Martins, R.; Maruff, P.; et al. Amyloid β Deposition, Neurodegeneration, and Cognitive Decline in Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study. The Lancet Neurology 2013, 12, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayart, J.-L.; Hanseeuw, B.; Ivanoiu, A.; Van Pesch, V. Analytical and Clinical Performances of the Automated Lumipulse Cerebrospinal Fluid Aβ42 and T-Tau Assays for Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis. J Neurol 2019, 266, 2304–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanseeuw, B.J.; Malotaux, V.; Dricot, L.; Quenon, L.; Sznajer, Y.; Cerman, J.; Woodard, J.L.; Buckley, C.; Farrar, G.; Ivanoiu, A.; et al. Defining a Centiloid Scale Threshold Predicting Long-Term Progression to Dementia in Patients Attending the Memory Clinic: An [18F] Flutemetamol Amyloid PET Study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2021, 48, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corder, E.H.; Saunders, A.M.; Strittmatter, W.J.; Schmechel, D.E.; Gaskell, P.C.; Small, G.W.; Roses, A.D.; Haines, J.L.; Pericak-Vance, M.A. Gene Dose of Apolipoprotein E Type 4 Allele and the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease in Late Onset Families. Science 1993, 261, 921–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrer, L.A. Effects of Age, Sex, and Ethnicity on the Association Between Apolipoprotein E Genotype and Alzheimer Disease: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA 1997, 278, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roses, A.D. APOLIPOPROTEIN E ALLELES AS RISK FACTORS IN ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE. Annu. Rev. Med. 1996, 47, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraley, C.; Raftery, A.; Scrucca, L.; Brendan Murphy, T.; Fop, M. Gaussian Mixture Modelling for Model-Based Clustering, Classification, and Density Estimation 2022.

- Jansen, W.J.; Ossenkoppele, R.; Knol, D.L.; Tijms, B.M.; Scheltens, P.; Verhey, F.R.J.; Visser, P.J.; Aalten, P.; Aarsland, D.; Alcolea, D.; et al. Prevalence of Cerebral Amyloid Pathology in Persons Without Dementia: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2015, 313, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, A.L.; Lawler, P.E.; Bollinger, J.G.; Li, Y.; Schindler, S.E.; Li, M.; Lopez, S.; Ovod, V.; Nakamura, A.; Shaw, L.M.; et al. The Performance of Plasma Amyloid Beta Measurements in Identifying Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Literature Review. Alz Res Therapy 2022, 14, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmqvist, S.; Janelidze, S.; Stomrud, E.; Zetterberg, H.; Karl, J.; Zink, K.; Bittner, T.; Mattsson, N.; Eichenlaub, U.; Blennow, K.; et al. Performance of Fully Automated Plasma Assays as Screening Tests for Alzheimer Disease–Related β-Amyloid Status. JAMA Neurol 2019, 76, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udeh-Momoh, C.; Zheng, B.; Sandebring-Matton, A.; Novak, G.; Kivipelto, M.; Jönsson, L.; Middleton, L. Blood Derived Amyloid Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease Prevention. J Prev Alz Dis 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergallo, A.; Mégret, L.; Lista, S.; Cavedo, E.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Vanmechelen, E.; De Vos, A.; Habert, M.; Potier, M.; et al. Plasma Amyloid β 40/42 Ratio Predicts Cerebral Amyloidosis in Cognitively Normal Individuals at Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2019, 15, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, D.S.; Ashton, N.J.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Simrén, J.; Lantero-Rodriguez, J.; Karikari, T.K.; Hiniker, A.; Rissman, R.A.; Salmon, D.P.; et al. Plasma Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease in Relation to Neuropathology and Cognitive Change. Acta Neuropathol 2022, 143, 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janelidze, S.; Palmqvist, S.; Leuzy, A.; Stomrud, E.; Verberk, I.M.W.; Zetterberg, H.; Ashton, N.J.; Pesini, P.; Sarasa, L.; Allué, J.A.; et al. Detecting Amyloid Positivity in Early Alzheimer’s Disease Using Combinations of Plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 and P-tau. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2022, 18, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keshavan, A.; Pannee, J.; Karikari, T.K.; Lantero-Rodriguez, J.; Ashton, N.J.; Nicholas, J.M.; Cash, D.M.; Coath, W.; Lane, C.A.; Parker, T.D.; et al. Population-Based Blood Screening for Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease in a British Birth Cohort at Age 70. Brain 2021, 144, 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Schindler, S.E.; Bollinger, J.G.; Ovod, V.; Mawuenyega, K.G.; Weiner, M.W.; Shaw, L.M.; Masters, C.L.; Fowler, C.J.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; et al. Validation of Plasma Amyloid-β 42/40 for Detecting Alzheimer Disease Amyloid Plaques. Neurology 2022, 98, e688–e699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zicha, S.; Bateman, R.J.; Shaw, L.M.; Zetterberg, H.; Bannon, A.W.; Horton, W.A.; Baratta, M.; Kolb, H.C.; Dobler, I.; Mordashova, Y.; et al. Comparative Analytical Performance of Multiple Plasma Aβ42 and Aβ40 Assays and Their Ability to Predict Positron Emission Tomography Amyloid Positivity. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2023, 19, 956–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milà-Alomà, M.; Ashton, N.J.; Shekari, M.; Salvadó, G.; Ortiz-Romero, P.; Montoliu-Gaya, L.; Benedet, A.L.; Karikari, T.K.; Lantero-Rodriguez, J.; Vanmechelen, E.; et al. Plasma P-Tau231 and p-Tau217 as State Markers of Amyloid-β Pathology in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat Med 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karikari, T.K.; Pascoal, T.A.; Ashton, N.J.; Janelidze, S.; Benedet, A.L.; Rodriguez, J.L.; Chamoun, M.; Savard, M.; Kang, M.S.; Therriault, J.; et al. Blood Phosphorylated Tau 181 as a Biomarker for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Diagnostic Performance and Prediction Modelling Study Using Data from Four Prospective Cohorts. The Lancet Neurology 2020, 19, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielke, M.M.; Frank, R.D.; Dage, J.L.; Jeromin, A.; Ashton, N.J.; Blennow, K.; Karikari, T.K.; Vanmechelen, E.; Zetterberg, H.; Algeciras-Schimnich, A.; et al. Comparison of Plasma Phosphorylated Tau Species With Amyloid and Tau Positron Emission Tomography, Neurodegeneration, Vascular Pathology, and Cognitive Outcomes. JAMA Neurol 2021, 78, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, S.A.; Spires-Jones, T.L.; Durrant, C.S. The Physiological Roles of Tau and Aβ: Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology and Therapeutics. Acta Neuropathol 2020, 140, 417–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, Y.-M.; Kokjohn, T.A.; Watson, M.D.; Woods, A.S.; Cotter, R.J.; Sue, L.I.; Kalback, W.M.; Emmerling, M.R.; Beach, T.G.; Roher, A.E. Elevated Aβ42 in Skeletal Muscle of Alzheimer Disease Patients Suggests Peripheral Alterations of AβPP Metabolism. The American Journal of Pathology 2000, 156, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, Y.-M.; Kokjohn, T.A.; Kalback, W.; Luehrs, D.; Galasko, D.R.; Chevallier, N.; Koo, E.H.; Emmerling, M.R.; Roher, A.E. Amyloid-β Peptides Interact with Plasma Proteins and Erythrocytes: Implications for Their Quantitation in Plasma. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2000, 268, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, O.L.; Kuller, L.H.; Mehta, P.D.; Becker, J.T.; Gach, H.M.; Sweet, R.A.; Chang, Y.F.; Tracy, R.; DeKosky, S.T. Plasma Amyloid Levels and the Risk of AD in Normal Subjects in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Neurology 2008, 70, 1664–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, H.; Braak, E. Frequency of Stages of Alzheimer-Related Lesions in Different Age Categories. Neurobiology of Aging 1997, 18, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Cardoso, C.; Dorieux, O.; Malgorn, C.; Epelbaum, S.; Petit, F.; Kraska, A.; Brouillet, E.; Delatour, B.; Perret, M.; et al. Age-Associated Evolution of Plasmatic Amyloid in Mouse Lemur Primates: Relationship with Intracellular Amyloid Deposition. Neurobiology of Aging 2015, 36, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Volunteers | AD patients | Non-AD patients | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 277 | 70 | 18 | |

| Age: mean (SD) | 66.5 (7.78) | 71.1 (8.05) | 65.6 (9.55) | 0.00044a |

| MMSE: mean (SD) | 28.5 (1.27) | 24.1 (4.59) | 26.4 (2.12) | 10-9a |

| APOE*: n ε4-/nε4+ (% ε4-/%ε4+) | 192/83 (70%/30%) |

21/40 (34%/66%) |

14/2 (87.5%/12.5%) | 10-7b |

| Gender: male/female | 98/179 | 32/38 | 7/11 | 0.28b |

| CSF/PET Aβ+ | CSF/PET Aβ- | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 74 | 77 | |

| Age: mean (SD) | 70.8 (8.11) | 67.8 (8.67) | 0.03a |

| MMSE: mean (SD) | 24.6 (4.57) | 27.8 (2.15) | 10-7a |

| APOE*: n ε4- / nε4+ (% ε4-/%ε4+) | 20/47 (30%/70%) | 49/23 (68%/32%) | 10-5b |

| Gender: male/female | 33/41 | 35/42 | 0.99b |

| Non-demented/demented | 53/21 | 73/4 | |

|

Volunteers AD patients Non-AD patients |

13 | 53 | |

| 60 | 9 | ||

| 1 | 15 | ||

| Measure of amyloid: | |||

| CSF | 54 | 24 | |

| [18F]flutemetamol PET | 17 | 51 | |

| [11C]PIB PET | 3 | 2 |

| Volunteers | AD | Non-AD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmatic Aβ+ | 115 | 67 | 10 |

| Plasmatic Aβ- | 162 | 3 | 8 |

| All individuals | CSF/PET Aβ+ | CSF/PET Aβ- |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmatic Aβ+ | 65 | 34 |

| Plasmatic Aβ- | 9 | 43 |

| Non-demented individuals | CSF/PET Aβ+ | CSF/PET Aβ- |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmatic Aβ+ | 44 | 31 |

| Plasmatic Aβ- | 9 | 42 |

| All individuals | CSF/PET Aβ+ | CSF/PET Aβ- |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmatic Aβ+ | 64 | 32 |

| Plasmatic Aβ- | 10 | 45 |

| Non-demented individuals | CSF/PET Aβ+ | CSF/PET Aβ- |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmatic Aβ+ | 43 | 29 |

| Plasmatic Aβ- | 10 | 44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).