1. Introduction

Ketamine is a well-established medication in both human and veterinary medicine for sedation and anaesthesia [

1,

2]. It has garnered attention for its antinociceptive and analgesic properties since the 1950s [

3]. Sadove et al. reported ketamine’s analgesic activity even at subanaesthetic dosages allowing to reduce undesirable side effects due to dissociative states [

4]. Later, the role of ketamine’s NMDA-antagonist activity was described [

5] and the use of subanaesthetic intravenous infusion of ketamine as adjuvant for pain therapy more widely investigated [

6]. In recent years, the use of subanaesthetic intravenous ketamine infusions has gained adhesion, especially in the context of multimodal pain therapy, with its potential in preventing wind-up, central sensitization, and postoperative hyperalgesia in humans [

7]. Veterinary studies have also recognized its benefits contributing to the growing body of evidence [

8,

9].

Subanaesthetic infusions have also been documented in dogs under clinical conditions, often combined with other medications, using dosages typically adapted from human studies, spanning from 0.12 to 0.6 mg/kg

/h [

8,

10,

11]. The intravenous dosage recommended in the veterinary literature ranges between 0.1 and 1 mg/kg/h [

12,

13,

14], extrapolated from human-related suggestions to minimize undesired effects[

15,

16,

17]. Human studies have reported analgesic plasma concentrations at approximately 150 ng/mL [

18,

19], while research on conscious dogs anticipated analgesic plasma concentrations to lie above 200 ng/mL, a concentration associated with the emergence of mild undesired effects [

20,

21]. Although there is suspicion regarding the anti-hyperalgesic activity of ketamine at lower concentrations in dogs (100-150 ng/mL), this phenomenon remains inadequately characterized [

9,

20].

The majority of pharmacokinetic investigations concerning ketamine in dogs have utilized significantly higher doses and, in many instances, have involved concomitant administration of other anaesthetic agents, consequently influencing its pharmacokinetic profile [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. When extrapolating the simulated blood concentration from these studies to low doses, it becomes evident that the concentrations in dogs are consistently 3 to 5 times lower than those observed in humans [

18,

31]. Even in the context of low-dose analgesic ketamine infusion (0.6 mg/kg

/h), dogs exhibit notably lower plasma concentrations compared to humans [

9]. These findings suggest that achieving the desired analgesic blood levels in dogs may necessitate higher dosages in comparison to human counterparts.

The first aim of the present study is to report the stereoselective pharmacokinetic analysis of racemic ketamine administered at low dose in unmedicated dogs. Secondary aims were to identify behavioural side effects elicited by ketamine administration and extrapolate a recommendation for ketamine infusion rate to target analgesic concentrations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal ethics

The in vivo experiments were approved by the local ethical committee for animal experimentation (Approval No. 2090) and all experiments performed according to the Swiss regulations and as described in the permission.

2.2. Animals and data collection

The study was performed on nine (n=9) intact male beagles, weighting between 7.6 and 12.7 kg body weight (mean ± SD, 9.1±1.5). The dogs were fasted during 6 hours with permanent access to water before each experiment. After aseptical preparation of the skin, a 22 G intravenous (IV) catheter was placed in the right cephalic vein for ketamine administration; A 18 G IV catheter was connected to an extension set with a 3-way cap, in the opposite cephalic vein for blood sampling. Each dog received two treatments (BOL and INF) with a minimum interval of 4 days. For treatment BOL, racemic ketamine (Narketan®10, Vetoquinol AG, Ittigen, Switzerland) was administered as a single IV bolus of 1 mg/kg over 2 minutes. For treatment INF, an initial bolus of 0.5 mg/kg was given over 1 minute followed by an IV infusion at 0.01 mg/kg/min for 1 hour. For both treatments, T0 was defined as the end of the bolus administration. Venous blood samples were taken from the left cephalic vein in heparinized tubes shortly before ketamine application and at 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 30 min after T0 in the treatment BOL, or at 1, 20, 40, 60 and 80 min after T0 in the treatment INF. All samples were immediately kept on ice, centrifuged soon after, and the plasma stored at −80 °C until determination of ketamine and norketamine enantiomers concentrations.in vivo experiments were approved by the local ethical committee for animal experimentation (Approval No. 2090) and all experiments performed according to the Swiss regulations and as described in the permission.

2.3. Plasma level analysis

Enantiomers of ketamine and of its active metabolite norketamine were measured in plasma using capillary electrophoresis [

32]. Briefly, the assay is based upon liquid–liquid extraction of ketamine and norketamine from 1 mL plasma followed by analysis of the reconstituted extract by capillary electrophoresis in the presence of a phosphate buffer (pH 2.5) containing 10 mg/mL highly sulfated β-cyclodextrin as a chiral selector [

9]. For each ketamine enantiomer, the calibration range was between 0.04 and 2.17 μg/mL and between 0.05 and 2.5 μg/mL for the enantiomers of norketamine, respectively. Lamotrigine was used as an internal standard (IST). Analyses were performed on a capillary electrophoresis analyser using a 50 μm ID uncoated fused-silica capillary of 45 cm effective length, an applied voltage of -20 kV and a cartridge temperature of 20 °C. The detection wavelength was 195 nm. The quantitation limit for all enantiomers was 2.5 ng/mL. Intraday precision data (n = 3) were < 6.5 % and interday data (n = 4) were < 9.2 % for all enantiomers at concentrations ≥ 25 ng/mL. The time curves for R- and S-ketamine (R-ket, S-ket) and R- and S-norketamine (R-nor, S-nor) were obtained for each animal with both treatments. The enantiomer ratio (R/S) was calculated for each sampling time for visualization of stereoselectivity.

2.4. Pharmacokinetic modelling

Each step of the pharmacokinetic modelling was performed with commercially available software (Monolix Suite

® v.2023R1, ©Lixoft). Following assumptions were made: the administration of racemic ketamine leads to equal amount of administered R- and S-ket; there is no interconversion between R- and S-enantiomers [

33]. Based on data fit, diagnostic plots, Akaike information criterion (AIC), Objective Function Value of the log-likelihood (OFV), and residuals analysis, the most suitable standard mammillary multi-compartmental model was determined for both R- and S-ket plasma concentrations of each individual (PKanalix

®). This was performed to obtain initial estimates for the population modelling. Non-compartmental analysis for R-/S-ket concentrations were also performed to orient initial estimates (PKanalix

®). Then, different combined parent-metabolite models of the population pharmacokinetic data were evaluated using Stochastic Approximation Expectation-Maximization algorithm (SAEM, Monolix

®). The final estimates were evaluated based on data fit, adequacy to initial estimates, diagnostic parameters, residual analysis and standard errors, and visual predictive check graphics.

2.5. Prediction

A simulation was run to obtain a simple infusion regimen allowing to maintain a summative plasma level for ketamine enantiomers of 150 ng/mL (see justification in the discussion below) while minimising norketamine accumulation in plasma. The simulation was performed both using the formulas of a previously published algorithm [

34] as well as the Simulx

® module of the Monolix software suite. Finally, a prediction of the context sensitive half-time curve for ketamine based on the pharmacokinetic data set was performed.

2.6. Behavioural and antinociceptive data

The dogs were scored every minute for behavioural patterns during administration of ketamine by an unblinded observer. Occurrence of seven predefined behavioural patterns was recorded using a checklist: #1 Signs of disorientation, #2 repeated lateral head movements, #3 starring eyes, #4 irregular breathing pattern, #5 muscular tremors, #6 salivation or lip licking, #7 excitement. At each evaluation, one point was attributed for each behaviour such that a score of 0 meant the absence of these abnormal behaviours while a maximal score of 7 implies marked undesirable effects. In parallel, a non-invasive experimental test for quantification of anti-nociception (Nociceptive Withdrawal Reflex evaluation) had been performed in all dogs during the ketamine infusion (treatment INF). More detailed description of material, methods and results for this investigation were addressed in a previous article [

9] and will not be presented here.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR; 25-75th percentile). Analyses were performed with a dedicated statistical software (Sigmaplot 14.0, Systat software, Inc.) and significance set for P < 0.05. The differences between R- and S-ket, as well as R- and S-nor were analysed by a 2-way ANOVA for repeated measures followed by posthoc Holm-Sidak test for pairwise comparison. The effect of time on enantiomer ratio and behaviour score was analysed with a Friedman ANOVA on ranks for repeated measures followed by posthoc Tukey test for pairwise comparison. Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curve analysis was performed with easyROC application [

35] to evaluate which cut-off values for plasma concentration of total ketamine best discriminate presence of undesirable side-effects (behavioural score above 2,1 and 0 respectively). Nonparametric analysis was performed to determine standard error and confidence interval [

36], and the Youden index method was applied to determine optimal cut-point [

37].

3. Results

In one dog blood samples could not be properly obtained during treatment BOL and in another one this happened during treatment INF such that samples from 8 dogs were analyzed in each case.

3.1. Plasma concentrations

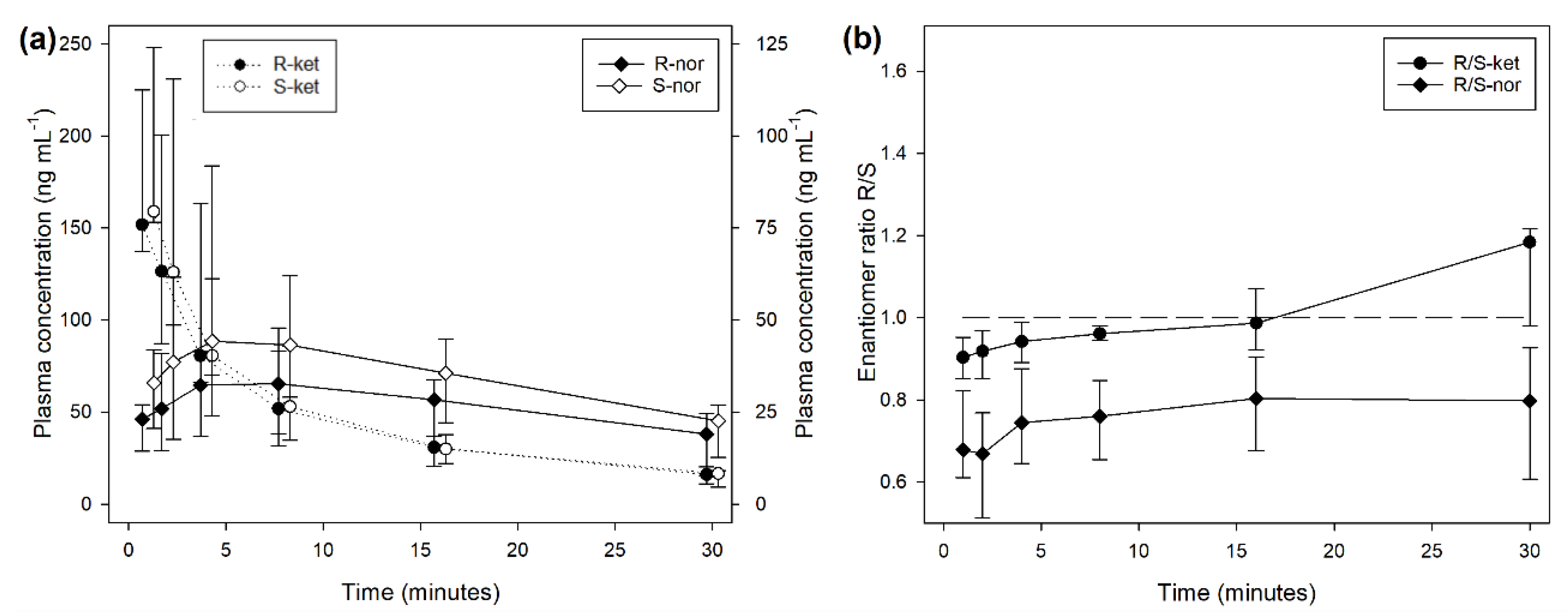

During treatment BOL, the plasma concentrations of R- and S-ketamine reached a peak immediately after end of injection followed by a steep decrease over time (

Figure 1). The concentration of S-ket was significantly higher than R-ket at 1 (P < 0.001) and 2 minutes (P = 0.001) after T0 with a difference of 16 (5-18) ng/mL (9% of the concentration).

The median R/S enantiomer ratio for ketamine was 0.95 (0.91-1.00) and did not differ significantly with time (

Figure 1). The plasma concentrations of norketamine increased for 4 minutes after ketamine administration before decreasing. Levels of S-nor were significantly higher than R-nor at all time points with a median R/S enantiomer ratio of 0.74 (0.64-0.86) (

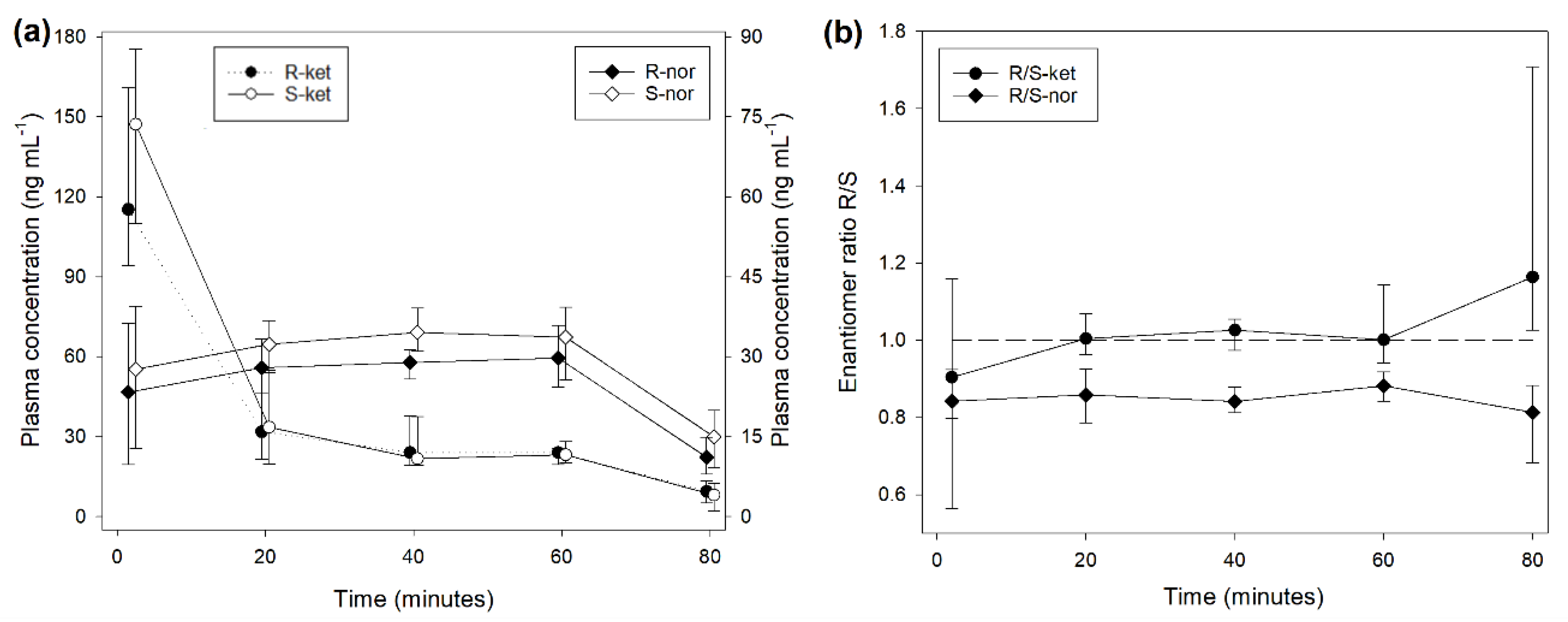

Figure 1). A similar picture was observed during treatment INF (

Figure 2), while the median R/S enantiomer ratio for norketamine was 0.87 (0.78-0.90) (

Figure 2).

3.2. Pharmacokinetic analysis and prediction

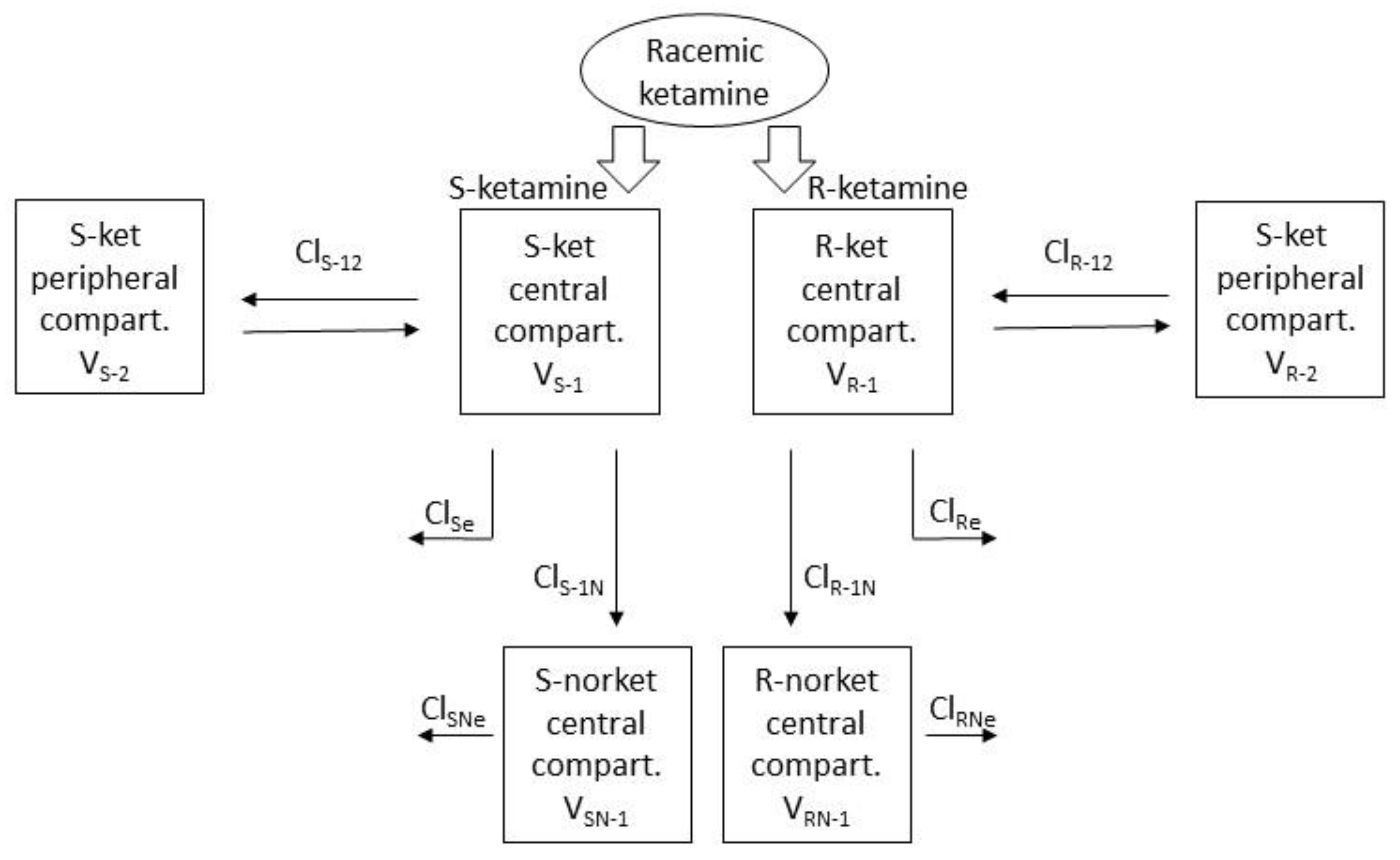

Both R- and S-ket were best modeled with a standard mammillary 2-compartment model and R- and S-nor with a standard mammillary 1-compartment model, issued from the central compartment of their respective parent drug (

Figure 3).

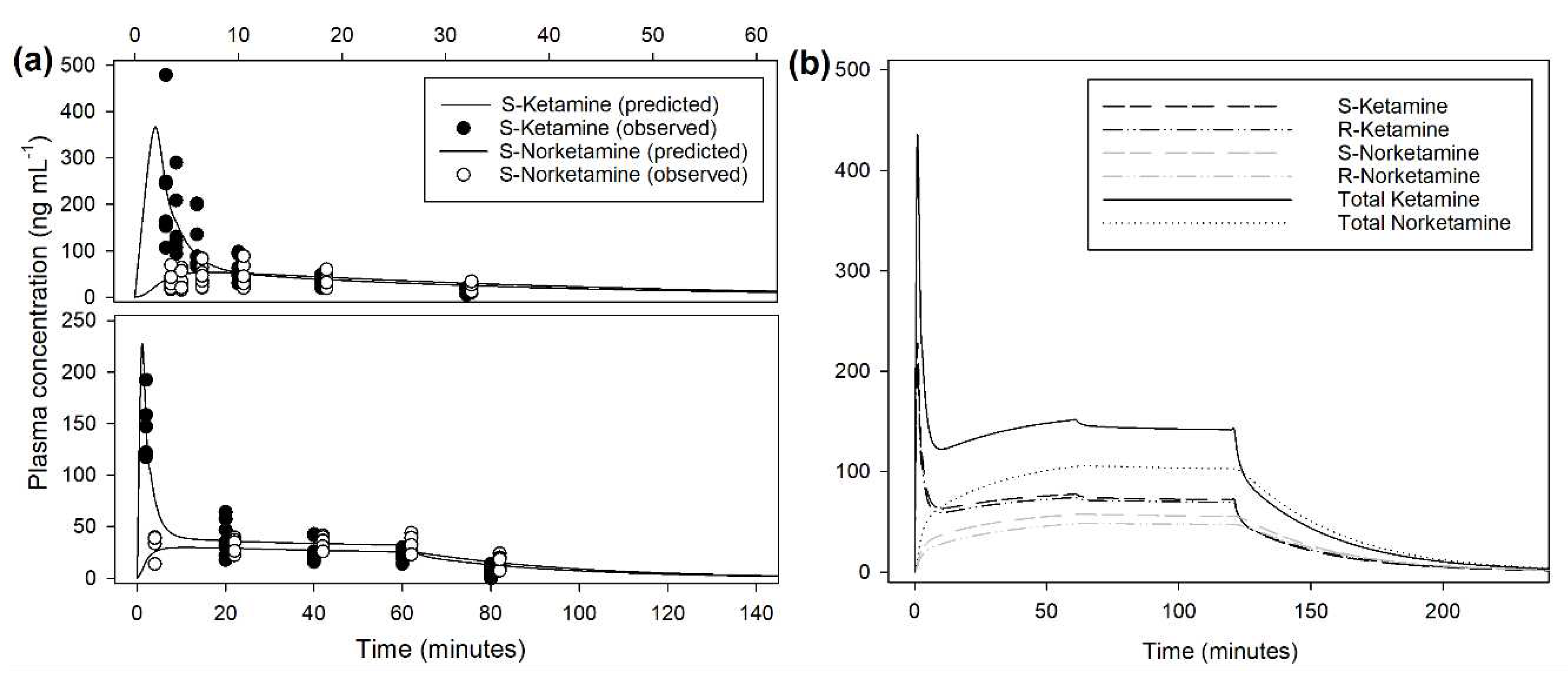

The main steps to determine the best population models are described in Appendix A. The respective pharmacokinetic parameters are presented in

Table 1. An example of prediction obtained from the population model is presented in

Figure 4. Extrapolation from the pharmacokinetic model to target approximately 150 ng/mL of total ketamine in plasma suggests an initial bolus of 0.5 mg/kg over 1 minute followed by 2 mg/kg/h reduced after 1 hour to 1.8 mg/kg/h (

Figure 4, Appendix A). Infusion rate to steady state of total ketamine at 150 ng/mL was predicted at 1.7 mg/kg/h. At this infusion rate, this model predicted a context-sensitive halftime (50%) for total ketamine of 10 minutes that nearly did not change with prolonged duration of infusion of 12 hours.

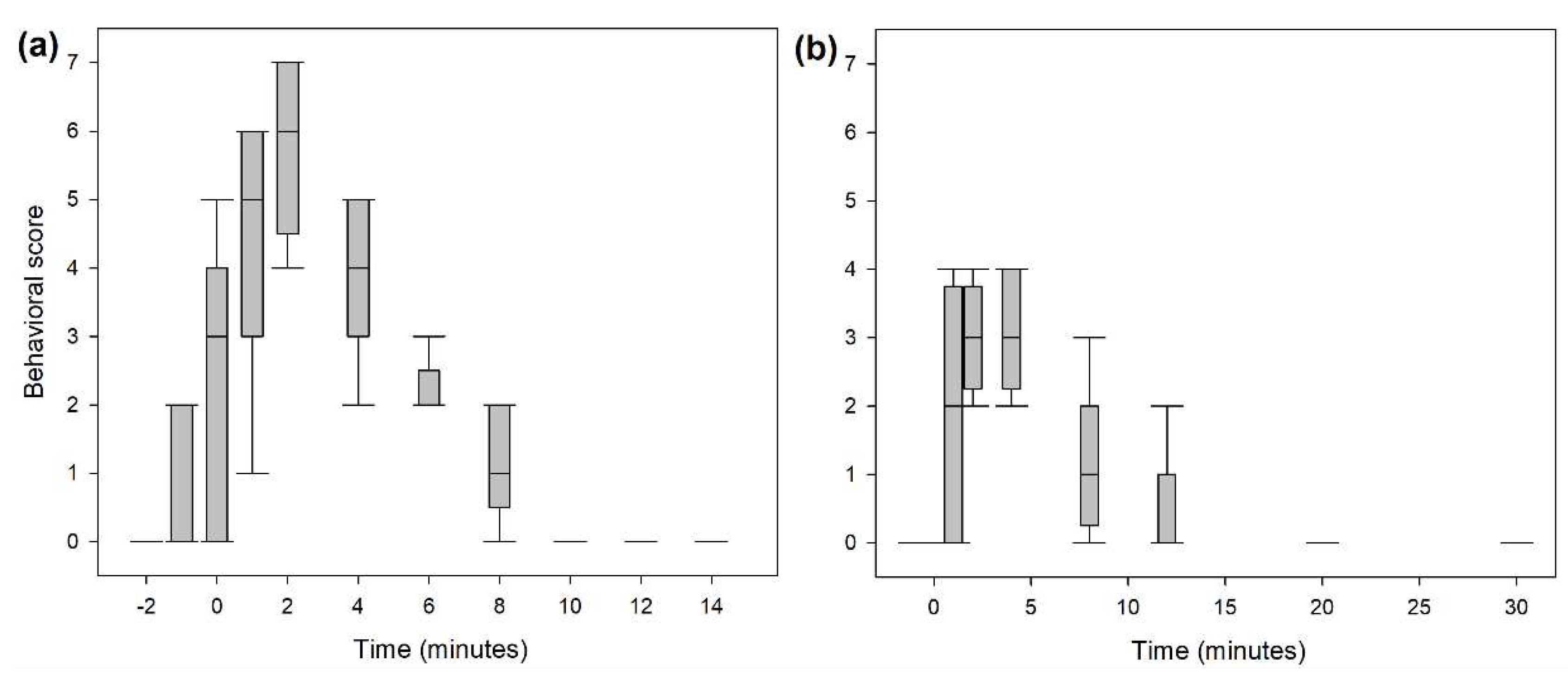

3.3. Behavioural scores

A significantly higher score for undesirable behavioral effects was observed within the first five minutes following the end of the bolus administration in both studies (

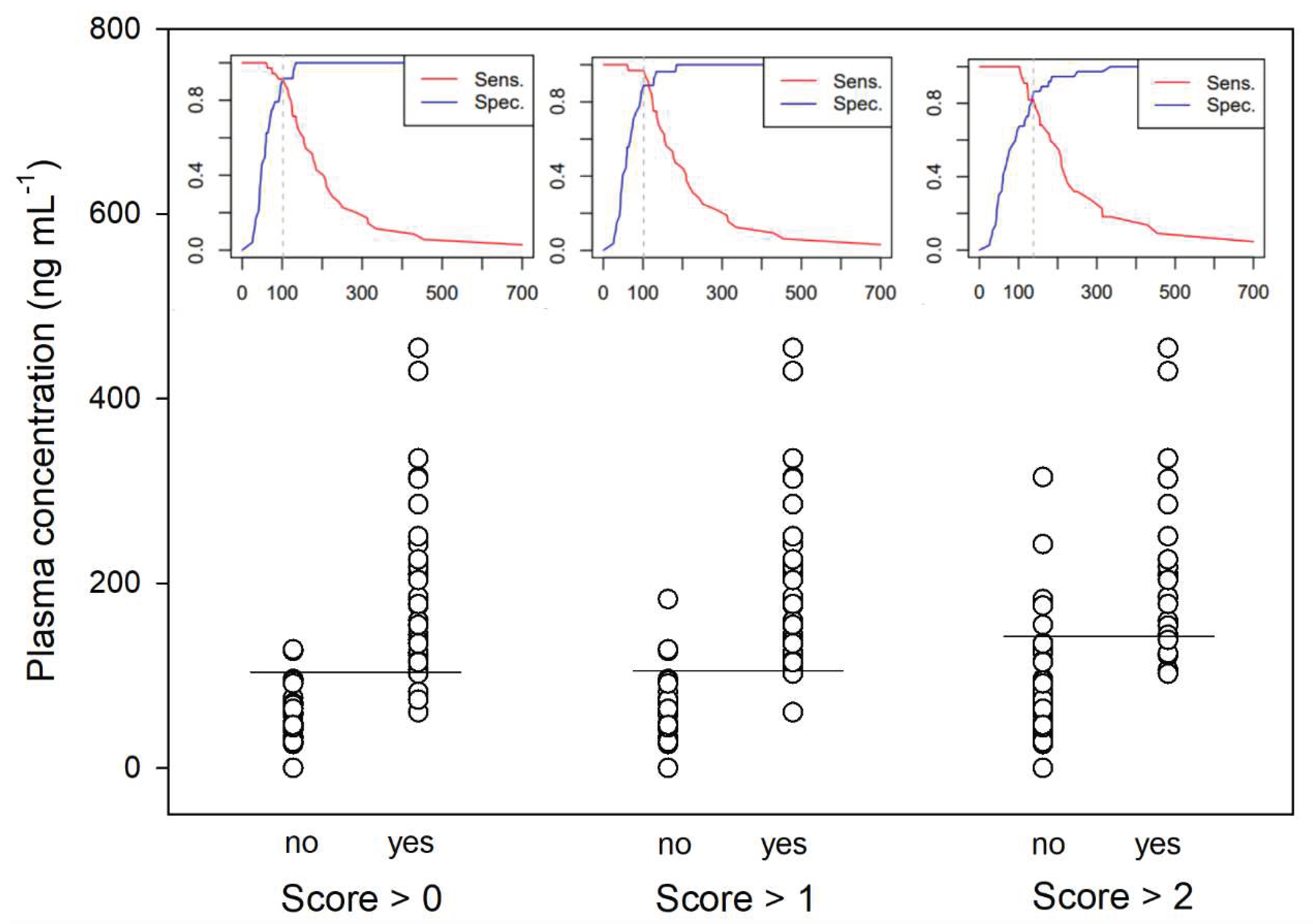

Figure 5). The three most common behaviors observed were signs of disorientation, repeated lateral head movements and starring eyes. An hysteresis of 2 minutes was observed for all dogs between peak plasma concentration and peak behavioral score. Taking this time lag in account, ROC curve analysis (

Figure 6) defined a plasma concentration for total ketamine of 138, 102 and 102 ng/mL as best cut-off values correlating respectively with a behavioral score above 2 (AUC: 0.9; specificity: 87%; sensitivity: 82%), above 1 (AUC: 0.95; specificity: 89%; sensitivity: 97%) and above 0 (AUC: 0.96; specificity: 92%; sensitivity: 91%).

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that the administration of the racemic mixture of ketamine at low doses in unpremedicated dogs did not result in stereoselective differences in the concentration time course between S- and R-ketamine. These findings are consistent with previous investigations of ketamine in dogs, both in vitro [

38] and in combination with other medications [

24,

27,

28,

30]. It is worth noting that stereoselective pharmacokinetics can vary across different species [

39] and have been observed in the case of ketamine in horses [

40].

Comparing the current findings with previously published data on ketamine pharmacokinetics in dogs is challenging due to the novelty of this study, which investigates ketamine in the absence of concomitant drugs. Furthermore, the individual examination of each enantiomer in this study complicates direct comparison with existing pharmacokinetic models for total ketamine. Notably, the observed plasma concentrations for both total ketamine and norketamine align closely with the anticipated values derived from previously published pharmacokinetic parameters [

21,

22,

23,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. These observations imply that the pharmacokinetics of ketamine may not be significantly impacted by the simultaneous administration of common anesthetic drugs, as has been observed with fluconazole, for example, which, although reported, was not deemed clinically significant in the context of anaesthesia [

29].

The final population pharmacokinetic models obtained for both S- and R-ketamine include a significant variability within subjects for several parameters across different occasions. Typically, inter-occasion variability (IOV) accounts for fluctuations within an individual across different instances, while inter-individual variability (IIV) reflects inherent distinctions among individuals. In Monolix

®, these variabilities are treated independently, with individual parameter values on each occasion being mutually exclusive. This implies that IOV essentially functions as IIV. Nevertheless, in specific scenarios, such as when there are only a few instances per individual, it becomes inappropriate to estimate both IOV and IIV, leading to the retention of only IOV as published earlier [

41]. The implementation of IOV varies in other population pharmacokinetics software, making the estimation of IOV without IIV practically not possible. However, Monolix

® enables the simultaneous estimation of variability, capturing parameter differences both between individuals and within the same individual across different occasions [

42]. In the present study, the two occasions referred to a single bolus and an infusion. It remains to be investigated if the variability observed is partly due to mode of administration.

The context-sensitive half-time of 10 minutes reported in this study notably contrasts with the terminal half-times typically documented for ketamine. This is possibly attributed to differences in their respective definitions, as previously highlighted [

43]. Given its significance in predicting the trajectory of effects induced by anaesthetic and analgesic agents, the low context-sensitive half-time underscores the potential for a rapid decline of the plasma concentrations following ketamine administration of relatively short duration as in the present study. Further exploration with prolonged infusion durations is warranted to verify the predicted sustained rapid reduction in plasma concentration over time.

Norketamine, recognized as an active metabolite of ketamine [

44,

45,

46,

47], demonstrates a discernible rise in plasma concentrations during ketamine infusion, with prolonged administration potentially leading to a slowdown in its elimination. However, the precise contribution of accumulated norketamine concentrations to the overall effect remains inadequately documented. Notably, the prolonged impact of norketamine has been suggested to potentially play a role in the enduring antidepressant effect of ketamine [

47], although comprehensive investigation into this phenomenon is still warranted.

In human subjects, research indicates that plasma concentrations ranging between 100 and 150 ng/mL are necessary to effectively alleviate hyperalgesia and allodynia [

15,

19,

20,

48]. In the context of this study, the primary result is that the total ketamine plasma concentrations achieved from an intravenous infusion at 10 micrograms/kg/min in unmedicated dogs fall significantly below the antihyperalgesic plasma levels (150 ng/mL). Through the application of the obtained pharmacokinetic model, it is determined that an infusion rate of ketamine (racemic) at 28-33 micrograms/kg/min is necessary to attain this targeted level. For short procedures necessitating rapid attainment of the desired plasma concentration, an intravenous bolus of approximately 0.5 mg/kg is recommended. Nonetheless, the requirement for this specific plasma concentration in dogs, as well as the potential presence of analgesic effects at lower levels, remains insufficiently investigated. Notably, a separate study conducted on conscious dogs reported that analgesic plasma concentrations may require to exceed 200 ng/mL [

21], while the anti-hyperalgesic activity of ketamine has been suggested at concentrations close to 100 ng/mL [

9].

Increasing the dose of ketamine to achieve optimal analgesic efficacy is often constrained by the potential emergence of undesirable behavioral side effects. While emergence delirium and dissociative states are recognized as undesirable outcomes of inappropriate ketamine anesthesia in dogs [

49], a comprehensive evaluation of the behavioral side effects associated with the administration of low-dose ketamine in canines has not been documented yet. In human subjects, adverse effects such as memory impairment, hallucinations, nightmares, dissociative states, and confusion have been reported [

50]. In the present study, no behavioral abnormalities were observed during the course of the infusion. However, in the initial minutes following bolus administration, transient signs of disorientation, repeated lateral head movements, and a fixed gaze were noted in nearly all the subjects, with no lasting complications. Additional irregular breathing patterns, muscular tremors, salivation, or lip licking, and sporadic instances of excitement were observed. A correlation between the occurrence of abnormal behavior and ketamine plasma concentration was noted, with the presence of at least three of these behavioral patterns being associated with concentrations exceeding 150 ng/mL. While further investigation is necessary, maintaining such potentially analgesic plasma concentrations appears challenging without the occurrence of at least a few mild behavioral side effects, such as transient disorientation, abnormal head movements, fixed gaze, and lip licking.

It would be valuable to include females in further studies to evaluate if gender specific differences in pharmacokinetic occur.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the presence of stereoselective pharmacokinetics for norketamine but not for ketamine. Additionally, it underscores the requirement for a higher dose (threefold increase) of ketamine in male dogs to attain plasma concentrations comparable to those deemed analgesic in humans. Importantly, it emphasizes the potential challenges associated with administering such doses without eliciting undesirable behavioral side effects. Consequently, there remains a clear need for targeted research aimed at understanding the dose-dependent antinociceptive properties of ketamine in dogs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Details of the pharmacokinetic modeling.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B., C.S. and O.L.L.; methodology, A.B., C.S., R.T., W.T. and O.L.L.; software, O.L.L.; validation, R.T., W.T. and O.L.L.; formal analysis, R.T., W.T. and O.L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, G.P. and O.L.L.; writing—review and editing, G.P., A.B., C.S., R.T., W.T. and O.L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the State Veterinary Office, County of Berne (Approval No. 2090).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wright, M. Pharmacologic effects of ketamine and its use in veterinary medicine. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1982, 180, 1462–71.

- Domino, E.F. Taming the ketamine tiger. 1965. Anesthesiology 2010, 113, 678–84. [CrossRef]

- Filibeck, U.Castellano, C. Strain dependent effects of ketamine on locomotor activity and antinociception in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1980, 13, 443–7. [CrossRef]

- Sadove, M.S.;Shulman, M.;Hatano, S.Fevold, N. Analgesic effects of ketamine administered in subdissociative doses. Anesth Analg 1971, 50, 452–7.

- Anis, N.A.;Berry, S.C.;Burton, N.R.Lodge, D. The dissociative anaesthetics, ketamine and phencyclidine, selectively reduce excitation of central mammalian neurones by N-methyl-aspartate. Br J Pharmacol 1983, 79, 565–75. [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.F.;Dahl, J.B.;Moore, R.A.Kalso, E. Peri-operative ketamine for acute post-operative pain: a quantitative and qualitative systematic review (Cochrane review). Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2005, 49, 1405–28. [CrossRef]

- McNicol, E.D.;Schumann, R.Haroutounian, S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of ketamine for the prevention of persistent post-surgical pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2014, 58, 1199–213. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.E.;Walton, J.A.;Hellyer, P.W.;Gaynor, J.S.Mama, K.R. Use of low doses of ketamine administered by constant rate infusion as an adjunct for postoperative analgesia in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2002, 221, 72–5. [CrossRef]

- Bergadano, A.;Andersen, O.K.;Arendt-Nielsen, L.;Theurillat, R.;Thormann, W.Spadavecchia, C. Plasma levels of a low-dose constant-rate-infusion of ketamine and its effect on single and repeated nociceptive stimuli in conscious dogs. Vet J 2009, 182, 252–60. [CrossRef]

- Slingsby, L.S.Waterman-Pearson, A.E. The post-operative analgesic effects of ketamine after canine ovariohysterectomy--a comparison between pre- or post-operative administration. Res Vet Sci 2000, 69, 147–52. [CrossRef]

- Sarrau, S.;Jourdan, J.;Dupuis-Soyris, F.Verwaerde, P. Effects of postoperative ketamine infusion on pain control and feeding behaviour in bitches undergoing mastectomy. J Small Anim Pract 2007, 48, 670–6. [CrossRef]

- Bednarski, R.M., Dogs and Cats, in Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia: The Fifth Edition of Lumb and Jones, K.A. Grimm, et al., Editors. 2015, John Wiley & Sons. p. 819-826.

- Gaynor, J.S.Muir, W.W., Handbook of veterinary pain management. 3rd ed. 2015, St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier. 620.

- Kerr, C., Pain management I: systemic analgesics, in BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Anaesthesia and Analgesia, T. Duke-Novakovski, M. De Vries, and C. Seymour, Editors. 2016, BSAVA: Gloucester, UK. p. 124-142.

- Clements, J.A.;Nimmo, W.S.Grant, I.S. Bioavailability, pharmacokinetics, and analgesic activity of ketamine in humans. J Pharm Sci 1982, 71, 539–42. [CrossRef]

- Domino, E.F.;Zsigmond, E.K.;Domino, L.E.;Domino, K.E.;Kothary, S.P.Domino, S.E. Plasma levels of ketamine and two of its metabolites in surgical patients using a gas chromatographic mass fragmentographic assay. Anesth Analg 1982, 61, 87–92.

- Richebe, P.;Rivat, C.;Rivalan, B.;Maurette, P.Simonnet, G. [Low doses ketamine: antihyperalgesic drug, non-analgesic]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2005, 24(11-12): pp. 1349–59. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.;Wise, R.G.;Painter, D.J.;Longe, S.E.Tracey, I. An investigation to dissociate the analgesic and anesthetic properties of ketamine using functional magnetic resonance imaging. Anesthesiology 2004, 100, 292–301. [CrossRef]

- Mion, G. Ketamine stakes in 2018: Right doses, good choices. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2019, 36, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Mion, G.Villevieille, T. Ketamine pharmacology: an update (pharmacodynamics and molecular aspects, recent findings). CNS Neurosci Ther 2013, 19, 370–80. [CrossRef]

- Kaka, U.;Saifullah, B.;Abubakar, A.A.;Goh, Y.M.;Fakurazi, S.;Kaka, A.;Behan, A.A.;Ebrahimi, M.Chen, H.C. Serum concentration of ketamine and antinociceptive effects of ketamine and ketamine-lidocaine infusions in conscious dogs. BMC Vet Res 2016, 12, 198. [CrossRef]

- Kaka, J.S.Hayton, W.L. Pharmacokinetics of ketamine and two metabolites in the dog. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 1980, 8, 193–202. [CrossRef]

- Schwieger, I.M.;Szlam, F.Hug, C.C., Jr. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ketamine in dogs anesthetized with enflurane. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 1991, 19, 145–56. [CrossRef]

- Henthorn, T.K.;Krejcie, T.C.;Niemann, C.U.;Enders-Klein, C.;Shanks, C.A.Avram, M.J. Ketamine distribution described by a recirculatory pharmacokinetic model is not stereoselective. Anesthesiology 1999, 91, 1733–43. [CrossRef]

- Roncada, P.;Zaghini, A.;Riciputi, C.;Romagnoli, N.Spadari, A. Kinetics of ketamine plasma and urine metabolite levels following intravenous administration in the dog. Vet Res Commun 2003, 27 Suppl 1: pp. 433–6. [CrossRef]

- Pypendop, B.H.Ilkiw, J.E. Pharmacokinetics of ketamine and its metabolite, norketamine, after intravenous administration of a bolus of ketamine to isoflurane-anesthetized dogs. Am J Vet Res 2005, 66, 2034–8. [CrossRef]

- Sandbaumhuter, F.A.;Theurillat, R.;Bektas, R.N.;Kutter, A.P.N.;Bettschart-Wolfensberger, R.Thormann, W. Pharmacokinetics of ketamine and three metabolites in Beagle dogs under sevoflurane vs. medetomidine comedication assessed by enantioselective capillary electrophoresis. J Chromatogr A 2016, 1467: pp. 436–444. [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, N.;Bektas, R.N.;Kutter, A.P.;Barbarossa, A.;Roncada, P.;Hartnack, S.Bettschart-Wolfensberger, R. Pharmacokinetics of ketamine and norketamine enantiomers after racemic or S-ketamine IV bolus administration in dogs during sevoflurane anaesthesia. Res Vet Sci 2017, 112: pp. 208–213. [CrossRef]

- Berke, K.;KuKanich, B.;Orchard, R.;Rankin, D.Joo, H. Clinical and pharmacokinetic interactions between oral fluconazole and intravenous ketamine and midazolam in dogs. Vet Anaesth Analg 2019, 46, 745–752. [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, N.;Bektas, R.N.;Kutter, A.P.N.;Barbarossa, A.;Roncada, P.;Hartnack, S.Bettschart-Wolfensberger, R. Pharmacokinetics of S-ketamine and R-ketamine and their active metabolites after racemic ketamine or S-ketamine intravenous administration in dogs sedated with medetomidine. Vet Anaesth Analg 2020, 47, 168–176. [CrossRef]

- Arendt-Nielsen, L.;Petersen-Felix, S.;Fischer, M.;Bak, P.;Bjerring, P.Zbinden, A.M. The effect of N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist (ketamine) on single and repeated nociceptive stimuli: a placebo-controlled experimental human study. Anesth Analg 1995, 81, 63–8. [CrossRef]

- Theurillat, R.;Knobloch, M.;Schmitz, A.;Lassahn, P.G.;Mevissen, M.Thormann, W. Enantioselective analysis of ketamine and its metabolites in equine plasma and urine by CE with multiple isomer sulfated beta-CD. Electrophoresis 2007, 28, 2748–57. [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, A.;Thormann, W.;Moessner, L.;Theurillat, R.;Helmja, K.Mevissen, M. Enantioselective CE analysis of hepatic ketamine metabolism in different species in vitro. Electrophoresis 2010, 31, 1506–16. [CrossRef]

- Levionnois, O.L.;Mevissen, M.;Thormann, W.Spadavecchia, C. Assessing the efficiency of a pharmacokinetic-based algorithm for target-controlled infusion of ketamine in ponies. Res Vet Sci 2010, 88, 512–8. [CrossRef]

- Goksuluk, D.;Korkmaz, S.;Zararsiz, G.Karaağaoğlu, A.E. EasyROC: An Interactive Web-tool for ROC Curve Analysis Using R Language Environment. The R Journal 2016, 8, 213–230. [CrossRef]

- DeLong, E.R.;DeLong, D.M.Clarke-Pearson, D.L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988, 44, 837–45.

- Youden, W.J. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 1950, 3, 32–5. [CrossRef]

- Capponi, L.;Schmitz, A.;Thormann, W.;Theurillat, R.Mevissen, M. In vitro evaluation of differences in phase 1 metabolism of ketamine and other analgesics among humans, horses, and dogs. Am J Vet Res 2009, 70, 777–86. [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, A.;Portier, C.J.;Thormann, W.;Theurillat, R.Mevissen, M. Stereoselective biotransformation of ketamine in equine liver and lung microsomes. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 2008, 31, 446–55. [CrossRef]

- Larenza, M.P.;Peterbauer, C.;Landoni, M.F.;Levionnois, O.L.;Schatzmann, U.;Spadavecchia, C.Thormann, W. Stereoselective pharmacokinetics of ketamine and norketamine after constant rate infusion of a subanesthetic dose of racemic ketamine or S-ketamine in Shetland ponies. Am J Vet Res 2009, 70, 831–9. [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, F.;Terrier, J.;Favre, S.;Gosselin, P.;Fontana, P.;Daali, Y.;Lenoir, C.;Samer, C.F.;Rollason, V.;Reny, J.L.;Csajka, C.Guidi, M. Population pharmacokinetics of apixaban in a real-life hospitalized population from the OptimAT study. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 2023, 12, 1541–1552. [CrossRef]

-

Inter occasion variability, /: Version 2023 2023; Available from: https, 2023.

- Bailey, J.M. Context-sensitive half-times: what are they and how valuable are they in anaesthesiology? Clin Pharmacokinet 2002, 41, 793–9. [CrossRef]

- Grant, I.S.;Nimmo, W.S.Clements, J.A. Pharmacokinetics and analgesic effects of i.m. and oral ketamine. Br J Anaesth 1981, 53, 805–10. [CrossRef]

- Shimoyama, M.; Shimoyama, N.;Gorman, A.L.;Elliott, K.J.Inturrisi, C.E. Oral ketamine is antinociceptive in the rat formalin test: role of the metabolite, norketamine. Pain 1999, 81, 85–93. [CrossRef]

- Holtman, J.R., Jr.;Crooks, P.A.;Johnson-Hardy, J.K.;Hojomat, M.;Kleven, M.Wala, E.P. Effects of norketamine enantiomers in rodent models of persistent pain. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2008, 90, 676–85. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.;Kobayashi, S.;Nakao, K.;Dong, C.;Han, M.;Qu, Y.;Ren, Q.;Zhang, J.C.;Ma, M.;Toki, H.;Yamaguchi, J.I.;Chaki, S.;Shirayama, Y.;Nakazawa, K.;Manabe, T.Hashimoto, K. AMPA Receptor Activation-Independent Antidepressant Actions of Ketamine Metabolite (S)-Norketamine. Biol Psychiatry 2018, 84, 591–600. [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.;Wallace, M.S.;Ridgeway, B.Yaksh, T. Concentration-effect relationship of intravenous alfentanil and ketamine on peripheral neurosensory thresholds, allodynia and hyperalgesia of neuropathic pain. Pain 2001, 91, 177–87. [CrossRef]

- Berry, S.H., Injectable anesthetics, in Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia: The Fifth Edition of Lumb and Jones, K.A. Grimm, et al., Editors. 2015, John Wiley & Sons. p. 283-287.

- Short, B.;Dong, V.;Galvez, V.;Vulovic, V.;Martin, D.;Bayes, A.J.;Zarate, C.A.;Murrough, J.W.;McLoughlin, D.M.;Riva-Posse, P.;Schoevers, R.;Fraguas, R.;Glue, P.;Fam, J.;McShane, R.Loo, C.K. Development of the Ketamine Side Effect Tool (KSET). J Affect Disord 2020, 266, 615–620. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).