1. INTRODUCTION

The field of organizational and behavioral science has extensively researched leadership. The idea that effective leadership is a key indicator of organizational success contributes to the importance of this field (Bass, 1990). Most people define leadership as a persuasion technique used to help organizations accomplish their goals on an individual, team, and corporate level. "The affinity people have with their leader or subordinate, which in turn shape their cultural fit, amendment of standards, and thus reactions to change, decisions of correctness, they accomplish experience, and their commitment of work for the organization even beyond the official-suggestion," is the definition of the leader-member relationship (Gerstner and Day, 1997, p. 34). A defined relationship and a mechanism for analyzing how leaders and members interact that could either support or obstruct professional success are provided by the Leader-Member Exchange Theory (LMX). There are ramifications for many aspects of organizational life for LMX. For example, LMX research has concentrated on worker productivity (Scandura & Graen, 1984), organizational climate, performance assessment (Wayne & Ferris, 1990; Linden, Wayne, & Stilwell, 1993), and so forth. However, the factors that can affect LMX may be investigated to support conceptual frameworks. It has long been believed that organizational dynamics can be better understood by considering demographic factors if they have an impact on LMX.

Gender roles are societal attitudes that apply to people based on their socially defined sexual identity (Eagly, 1987). Throughout history, societal attitudes depend on the concept that certain vocations, hobbies, and emotions are more suited for one gender than the other and those concepts have been prominent and persistent. Men are supposed to have agentic traits such as assertiveness, independence, and boldness, while women are thought to have a high degree of communal attributes such as sociability, generosity of spirit, and care for others (Bakan, 1966; Eagly, 2009). The characteristics given to each gender are used to make decisions on how women and men expected to behave at home and at work to ensure the betterment of their workgroup. People's expectations are influenced by gender role beliefs, as described by Eagly (2009), which influence the perceived consequences of interactions, attitudes, exchange quality, and participation in activities in job role definition. A range of internal and external demographic variables influence the quality of LMX. The key demographic characteristics are age, gender, tenure, and educational background (Malangwasira, 2013). Leaders and subordinates can provide distinct demographic insights. This study evaluates the influence of gender similarity/dissimilarity on LMX of the hospitals in Kolkata.

2. Research Objective

To empirically investigate the degree of correlation between leaders’ and members’ perception of the exchange quality shared by them in the gender similar / dissimilar groups.

3. Literature Review

LMX theory was proposed by Dansereau, Graen, Haga & Cashman in 1975. In those days the LMX was referred to as the Vertical Dyad Linkage (VDL) approach to accomplishment. LMX theory consequently viewed leadership as a dyadic action between a leader and each of the subordinates differently, depending on mutual perception on their relationship. Schriesheim, Castro and Cogliser (1999) viewed the aboriginal Vertical Dyad Linkage as evolving into two theoretical approaches LMX and individualized leadership. The LMX approach has exploited measures of leader-member exchange as its central idea of exploring perception of the relationship from both side of the dyad but has left some dimensions open-ended. According to LMX theory, effective leadership is achieved via the dyadic relationship of the leader and member together. These relationships experience or is generated out of a conglomerate of social exchanges and are characterized as the quality of the relationship between a leader and a subordinate (Schriesheim et al., 1999). LMX relationships develop through a process of exchanging a communication of tangible and intangible commodities inside a leader-member dyad. Here, a leader might use resources or transactions like, information, influence, desired tasks, latitude, support and attention, for the services of the employee, which might include task performance, commitment, loyalty and citizenship.

Originating from social exchange and reciprocity theories, Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) display the dyadic relationship between team-members and their team-boss in organizations (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995; Graen & Cashman, 1975; Northouse, 2010). The Leader (supervisor) and the Member (subordinate) have a two-way connection termed a dyad, according to LMX (Graen & Cashman, 1975; Danserau, Graen, & Haga, 1975; Graen & Schiemnann, 1978; Graen & Scandura, 1987; Vecchio & Gobdel, 1984 ; Deluga, 1998). According to the notion, leaders handle each employee differently in terms of social interactions, i.e., supervisors do not engage with subordinates in the same way (Graen & Cashman, 1975; Wayne & Green, 1993). Because supervisors have constrained time and resources, and people have concerns and differing levels of interest in their job, the quality of the interaction or exchange varies. In exchange for subordinates' performance on both scheduled and unstructured duties, supervisors trade personal and positional resources. Sharing of significant information, influence in decision-making, work assignment, job latitude, assistance, and attention are examples of personal and positional resources (Graen & Cashman, 1975). This research is a helpful addition to the pool of information to comprehend the dynamics of dyadic functioning in organizational settings in light of the demographic element gender, as indicated by the widespread use of LMX theory.

Past studies investigating the effect of gender on leadership styles have found strong evidence supporting gender differences in organizational context, where women have the tendency to adopt a more democratic, participative style, whereas, men would apply a more autocratic and directive style (Eagly & Johnson, 1990; 1996). As noted by Ansari (1989), male leaders exhibited a greater likelihood of using influence tactics such as negative sanction, assertiveness, reward, and exchange as compared to female leaders. Other researchers such as Carothers and Allen (1999) also concluded that males changed tactics from reward to coercion whenever challenged while females continued to use request when insulted. Some previous researches mentioned a remarkable fact that, both male and female supervisors exhibit a positive bias toward subordinates of the same sex and rate members of the same gender higher (Varma & Stroh, 2001). Gender match affected LMX in a Malaysian setting, which led to organizational support (Bhal, Ansari and Aafaqi, 2007). Males had a more positive LMX relationship under male supervision, while females had a more positive LMX relationship under female supervision, with a significant interaction between supervisor gender and subordinate gender, highlighting different patterns of exchange between the two groups (Milner, Katz, Fisher & Notrica, 2007). The gender of the supervisors, on the other hand, had no significant impact on LMX encounters (May-Chiun, Ramayah, Ernest, 2009). A study of Indonesian government officials found that gender had a direct impact on LMX (Santoso & Franksiska, 2019) Hence, from the above backdrop the specific focus of this study is to examine whether gender can influence leader-member exchange quality significantly or not.

4. Research Design

4.1. Research question

Do gender influence leader-member exchange quality across workgroups in hospitals of Kolkata?

4.2. Sample description

The sample size for the study is 594, with age range from 19 to 65 years. The sample for the study was organized department-wise and selected using clustered & structured sampling techniques. Questionnaire was administered (4 Private & 4 Public healthcare organizations) to the identified leader and member sets (at least 2 dyads from each department).

Average score of members LMX of each work group under the leader is computed (97 scores) and considered for comparison with leader’s score. The groups are then categorized into male-male Leader-Member groups, female-female Leader-Member groups and mixed Leader-Member groups and the groups are comprised of 25, 38 and 34 samples respectively.

4.3. Hypothesis

- a)

Gender has an impact on LMX of groups with male leader and male member?

- b)

Gender has an impact on LMX of groups with female leader and female member?

- c)

Gender has an impact on LMX of groups with mixed gender leader & member?

4.4. Statistical Tool used

Pearson’s correlation test is conducted to understand the strength and direction of relationship between leader and member perception of relationship quality in work groups with male-male or female-female or male/female- female/male composition in hospitals of Kolkata.

4.5. Description of the instrument & scoring interpretation

LMX-7 scale used in this study contains items that asks to describe individual perception on LMX relationship with leader or subordinates (one at a time). The score obtained on the questionnaire of the scale, reflects the quality of the leader–member relationships under test and indicates the degree to which the relationships are effectively. To interpret LMX 7 scores the point mentioned in scale as very high has a range of value between 30–35, high can be marked for the range of 25–29, moderate lies between 20–24, low can be 15–19, and very low is 7-14. Scores in the upper ranges indicate stronger, higher-quality leader–member exchanges (e.g., in- group members), whereas scores in the lower ranges indicate exchanges of lesser quality (e.g., out-group members). (G. B. Graen and M. Uhl-Bien, 1995).

5. Results

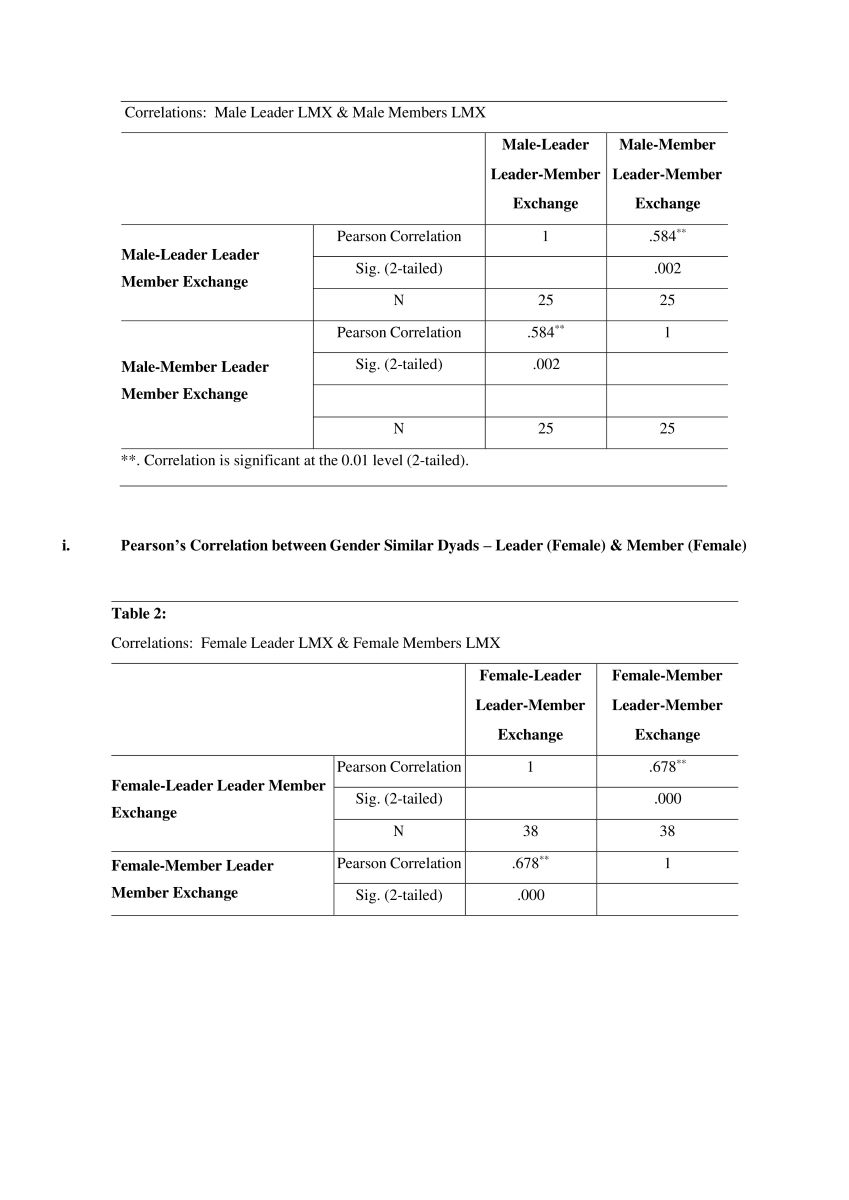

Pearson’s correlation analysis is conducted to understand the statistical relationship between male leaders’ and male members’ perception of Leader Member Exchange quality.

-

i.

Pearson’s Correlation between Gender Similar Dyads ---Leader (Male) & Member (Male)

Table 1.

Correlations: Male Leader LMX & Male Members LMX.

Table 1.

Correlations: Male Leader LMX & Male Members LMX.

| |

Male-Leader

Leader-Member Exchange

|

Male-Member

Leader-Member Exchange

|

| Male-Leader Leader Member Exchange |

Pearson Correlation |

1 |

.584**

|

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

|

.002 |

| N |

25 |

25 |

| Male-Member Leader Member Exchange |

Pearson Correlation |

.584**

|

1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

.002 |

|

| |

|

|

| N |

25 |

25 |

The test yields a p-value less than 0.01 (p<0.01), hence the association in the research question is statistically significant. The direction of the relationship is positive & the strength of relationship is medially strong with correlation coefficient (r) as 0.584. LMX quality perceived by leader and member in male-male group has a medium correlational value.

-

ii.

Pearson’s Correlation between Gender Similar Dyads – Leader (Female) & Member (Female)

Table 2.

Correlations: Female Leader LMX & Female Members LMX.

Table 2.

Correlations: Female Leader LMX & Female Members LMX.

| |

Female-Leader Leader-Member

Exchange

|

Female-Member Leader-Member

Exchange

|

| Female-Leader Leader Member Exchange |

Pearson Correlation |

1 |

.678**

|

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

|

.000 |

| N |

38 |

38 |

| Female-Member Leader Member Exchange |

Pearson Correlation |

.678**

|

1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

.000 |

|

| |

N |

38 |

38 |

When, the test is conducted to understand the statistical relationship between female leaders’ and female members’ perception of Leader Member Exchange quality, the test yields a p-value less than 0.01 (p<0.01), hence the correlation is statistically significant. The direction of the relationship is positive & the strength of relationship is strong with correlation coefficient (r) as 0.678. LMX quality perceived by leader and member in female-female group has a strong correlational value.

-

iii.

Pearson’s Correlation between Gender Dissimilar Dyads – Leader (Male / Female) & Member (Female / Male)

Table 3.

Correlations: Male/Female Leader LMX & Female / Male Members LMX.

Table 3.

Correlations: Male/Female Leader LMX & Female / Male Members LMX.

| |

Mixed- Leader- Leader Member Exchange |

Mixed-Member Leader Member Exchange |

| Mixed-Leader Leader Member-Exchange |

Pearson Correlation |

1 |

.747**

|

| Sig. 2-tailed) |

|

.000 |

| N |

34 |

34 |

| Mixed-Member Leader Member Exchange |

Pearson Correlation |

.747**

|

1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

.000 |

|

| N |

34 |

34 |

Third correlational test is conducted to understand the statistical relationship between mixed category of leaders’ and mixed-group members’ perception of Leader Member Exchange quality. The test yields a p-value less than 0.01 (p<0.01), hence the association is statistically significant. The direction of the relationship is positive & the strength of relationship is very strong with correlation coefficient (r) as 0. 747. LMX quality perceived by leader and member in male-female/female-male group has a high correlational value.

6. Finding

When compared it can be seen that the gender dissimilar dyads show highest leader-LMX & member-LMX correlation (R-value) when correlation analysis is conducted to understand the statistical relationship between the two.

Table 4.

Comparison between results.

Table 4.

Comparison between results.

| |

Respective Leader-Member Exchanges |

| All Male- Leader Member Exchange |

Pearson Correlation |

1 |

.584**

|

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

|

.002 |

| N |

25 |

25 |

| All Female Leader Member Exchange |

Pearson Correlation |

.678**

|

1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

.000 |

|

| N |

38 |

38 |

| Mixed Team- Leader Member Exchange |

Pearson Correlation |

.747**

|

1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

.000 |

|

| N |

34 |

34 |

Gender appears to have interesting implications when used as a marker of evaluation. When attempt was made to understand how gender similar & dissimilar dyads would perceive leader member relationship quality, it was seen that in case of both the dyadic partners being male the correlation is least, which increases when both the dyadic partners are female. However, the degree of perceptual agreement of the LMX quality is highest when the workgroup is heterogeneous in composition, i.e., male and female combination for leader and members, for the sample under test. The direction of relationship is positive in all three cases and strength of the relationship varies from medium to strong.

7. Discussion & Conclusion

The perception of the male or female leader about their male or female member in a heterogeneous group is generally better than homogeneous combinations, as it cancels the normal ego-clashes between same genders. Both dyad-members, in gender dissimilar work-groups generally perceive the relationship in a convergent manner or has agreement in perception because it is perceived probably on the basis of interactions, communications and behavioral patterns that the dyad shares in daily operational activities (Hogg, 1992; Sias, 1996; Graen & Scandura, 1987). The results can be explained in line with previous researches where the acceptance & reciprocation of positive exchange is largely dependent on followers’ way of accepting their leader (Graen et al., 1982; Graen, Scandura, & Graen, 1986). Uhl-Bien and Maslyn (2003) reported on components that might comprise reciprocal behaviour like similar interest, pattern of competition & mutual affection, highlighted as factors enhancing positive relationship. This kind of relationships are generally blessed with mutual interests and high-quality exchange. Gender is a significant predictor of LMX relationship quality and there are many other factors that may impact the perceptual agreement of the leader and the member (Matkin & Barbuto, 2012; Pelled & Xix, 2000; Milner et al., 2007; Thomas, 2013).

In case of gender similar workgroups, the LMX correlation is positive; more specifically female-female combination shows slightly stronger relationship when compared to male-male dyadic combination. That the intention to engage in activities that enhance mutual trust and obligations co-dependence is high for gender- similar groups. But when gender heterogeneous workgroup is being investigated the LMX correlation is very strong. This can have a plausible explanation in the characteristics of LMX for the management in particular. Same employees often share different quality of bond with different leaders with change in situational or professional reasons (Kim et al., 2013). But when gender of dyadic partners is dissimilar, LMX is high, probably because employees are super-conscious that their LMX will somewhat be reflecting their acceptance towards opposite gender subordinate or boss (Kark & Manor, 2003; Thomas, 2013). However, in gender similar dyads, due to congruence or perceptual similarity in respect to attributes like feminine or expressive behaviors (e.g., empathy) in case of females and masculine or instrumental behaviors (e.g., competitiveness) in case of males, the perceptual agreement is discretionary & contingent. Kidder and Parks (2001) indicated that LMX is highly consistent within female group due to characteristic of similarity regarding sincerity towards work and requirement of obvious dependence on each other to maintain family urgencies. It is less consistent in male groups due to common ego clashes between males. Both are fundamental and common characteristics of the mentioned genders. These research findings can be used by both hospital management and academia to asses such relationships while taking any strategic decisions, and might add value for future research in the behavioral field.

References

- Bass, B. M. (1985). ‘Leadership and performance beyond expectation’, New York: Free Press.

- Brower, H. H., Schoorman, F. D., & Tan, H. H. 2000, ‘A model of relational leadership: The integration of trust and leader-member exchange’, Leadership Quarterly, 11: 227–250. [CrossRef]

- Bhal KT, Ansari. MA, ‘Measuring quality of interaction between leaders and members’,Journal of Applied Social Psychology 26 (11), 945-0972. [CrossRef]

- Dansereau, F., Graen, G.B., & Haga, W. (1975), ‘A vertical dyad linkage approach to leadership in formal organizations’, Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 13, 46-78. [CrossRef]

- Deluga, R. J. 1994, ‘Supervisor trust building, leader-member exchange and organizational citizenship behaviour’, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 67,315–326. [CrossRef]

- Desimone, L., C, Greenwich, CT 2002, ‘Toward a more refined theory of school effects: A study of the relationship between professional community and mathematics teaching in early elementary school. Research and Theory in Educational Administration’, Miskel & W. Hoy (eds.), Information Age Publishing, 8. 67-89.

- Dienesch, R. M, Liden, R. C 1986, ‘Leader-member exchange model of leadership: A critique and further development’, Journal of Academy of Management Review [AMR], 11, 618 – 634. [CrossRef]

- Deluga R. J. (1994). Supervisor trust building, leader-member exchange and organizational citizenshipbehaviour, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 67,315–326. [CrossRef]

- Dienesch, R. M, Liden, R. C (1986), Leader-member exchange model of leadership: A critique and further development. Journal of Academy of Management Review [AMR], 11, 618 - 634. [CrossRef]

- Evans, Martin G 1970, ‘The effects of supervisory behavior on the path-goal relationship’, Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 5: 277–298. [CrossRef]

- Ferris G. 1985, ‘Role of leadership in the employee withdrawal process: A constructive replication’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 70(4): 777-781. [CrossRef]

- Gerstner, C.R. and Day, D.V. (1997) “Meta-analytic review of leader-member exchange theory: correlates and construct issues”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 82 No. 6, pp. 827-844. [CrossRef]

- Gomez, C., & Rosen, B. 2001, ‘The leader-member exchange as a link between managerial trust and employee empowerment’,. Group and Organization Management, 26, 53-69. [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.B. 1976, ‘Role making processes within complex organizations’, M.D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology (pp. 1201-1245). Chicago: Rand-McNally.

- Graen, G.B., & Cashman, J. (1975). A role-making model of leadership in formal organizations: A developmental approach, In: J.G. Hunt & L.L. Larson (Eds.), Leadership Frontiers (pp. 143-166). Kent, OH: Kent State University Press.

- Graen, George B. and Uhl-Bien, Mary 1995, ‘Relationship-Based Approach to Leadership: Development of Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) Theory of Leadership over 25 Years: Applying a Multi-Level Multi-Domain Perspective’, Management Department Faculty Publications. Paper 57. [CrossRef]

- Hersey. P and Blanchard. K.H. (1969). Management of Organizational Behaviour: Utilization of human resources. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall.

- House, Robert J 1996, ‘Path-goal theory of leadership: Lessons, legacy, and a reformulated theory’,Leadership Quarterly. 7 (3): 323–352. [CrossRef]

- Jagendorf, J. & Malekoff, A 2005, ‘Groups-on-the-go: Spontaneously formed mutual aidgroups foradolescents in distress’, in Malekoff, A., & Kurland, R. (eds.). A quarter century of classics (1978- 2004): Capturing the theory, practice, and spirit of social work with groups. The Haworth Press. [CrossRef]

- Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1978). The social psychology of organizations (Vol. 2, p. 528). New York:Wiley.

- Liden, R. C., & Graen, G 1980, ‘Generalizing ability, of the vertical dyad linkage model of leadership’,Academy of Management Journal, 23, 451-465.

- Liden, R. C., & Maslyn, J. M 1998, ‘Multidimensionality of leader-member exchange: An empiricalassessment through scale development’, Journal of Management, 24, 43-73. [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K., Lippitt, R. and White, R 1939, ‘Patterns of aggressive behaviour in experimentally createdsocial climates’, Journal of Social Psychology 10: 271-99. [CrossRef]

- Milner, K., Katz, L.-A., Fisher, J., & Notrica, V. (2007). Gender and the Quality of the Leader-Member Exchange: Findings from a South African Organisation. South African Journal of Psychology, 37(2), 316– 329. [CrossRef]

- May-Chiun Lo, T. Ramayah and Ernest Cyril de Run (2009). Leader member exchange, gender, and influence tactics. A test on multnational companies in Malaysia. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 7(1).

- Scandura, T. A., & Graen, G. B. (1984), ‘Moderating effects of initial leader-member exchange statuson the effects of a leadership intervention’ , Journal of Applied Psychology, 69, 428-436. [CrossRef]

- Scandura, T. A., Graen, G. B., & Novak, M. A. (1986), ‘When managers decide not to decide autocratically: An investigation of leader-member exchange and decision influence’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 579- 584. [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck J, May DR, Brown FW. 1994, ‘Procedural justice explanations and employee reactions to economic hardship: a field experiment’, Journal of Applied Psychology 79: 455-460. [CrossRef]

- Scott, S. G., & Bruce, R. A. (1994), ‘Determinates of innovative behavior: A path-model of individualinnovation in the workplace’, Academy of Management Journal, 137,580-607. [CrossRef]

- Steers, R.M. Bigley, G.A. & Porter, L.W 1996, ‘Motivation and leadership at work’, Singapor,McGraw- Hill.

- Sweeney, J. T. and Quirin, J. J 2008, ‘Accountants as layoff survivors: A research note. Accounting’, Organizations and Society, 34(6/7):787-795. [CrossRef]

- Wayne SJ, Shore M, Liden RC 1997, ‘Perceived organizational support and leader-memberexchange: A social exchange perspective’, Acad.Manage. J., 40(1): 82-111.

- Yukl, G., & Van Fleet, D. D 2000, ‘Theory and research on leadership in organizations’, M. D. Dunnette & L.

- M. Hough (Eds.),Handbook of organizational psychology 2nd ed., Vol. 5, pp.147–197,Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).