1. Introduction

Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase 1 (PARP1), the most known member of ADP-ribosyltransferase family, acts as a prime sensor of DNA strand breaks; it becomes catalytically active upon binding to broken DNA. PARP1 catalyzes the formation of poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR). This process, known as PARylation, leads to the recruitment and activation of various DNA repair factors [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. PARP1 is a critical sensor and regulator in DNA damage response, primarily through its involvement in the base excision repair (BER) pathway. Furthermore, PARP1 is implicated in other DNA repair processes, including nucleotide excision repair (NER), homologous recombination (HR), and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), suggesting its broader involvement in maintaining genome stability. In addition, PARP1 is involved in other cellular processes such as transcriptional regulation, chromatin remodeling, and cell death. The BER pathway consists of several consecutive steps: excision, where an aberrant base is detached from the DNA backbone; incision of phosphodiester backbone at the position of abasic site; gap processing that includes editing of the DNA termini, when necessary, followed by dNMP insertion and ligation of nicks, where the DNA backbone is restored. BER is mainly initiated by one of damage-specific DNA glycosylases and can proceed either a short-patch (SP) or a long-patch (LP) pathways with replacement of one or several nucleotides, respectively [

6,

7]. In addition, this type of DNA repair also comprises several minor pathways, single-strand break repair (SSBR), which starts from DNA intermediate with already cleaved sugar-phosphate backbone of DNA, nucleotide incision repair (NIR), where AP endonuclease 1 (APE1) initiates DNA-glycosylase independent repair of some types of oxidized bases [

8,

9].

Recently [

10], using the extracts and RNA preparations obtained from the parental HEK293T cell line (HEK293T WT) and its derivative HEK293T/P1-KD cell line with reduced PARP1 expression caused by corresponding shRNA (PARP1 knockdown, HEK293T/P1-KD) we assessed by qPCR the levels of mRNAs coding for some BER proteins involved in catalysis and regulation in short-patch pathway: PARP1, APE1, uracil DNA glycosylase (UNG2), DNA polymerase β (POLβ), DNA ligase III (LIG3), XRCC1 and Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase 2 (PARP2). The levels of mRNA coding PARP1 and amount of PARP1 protein were roughly halved in HEK293T/P1-KD cells as compared to parental cells. The PARP1 amount in the cells did not significantly influence the mRNA levels of UNG2, APE1, POLβ, LIG3, and XRCC1. Interestingly, the amount of mRNA coding PARP2 in HEK293T/P1-KD cells proved to be halved as compared to parental cells. Catalytic activities of the BER enzymes in the whole-cell extracts evaluated using specific DNA substrates also did not differ significantly between HEK293T WT and HEK293T/P1-KD cells. Under conditions of PAR synthesis, no significant change in the efficiencies of the reactions catalyzed by UNG2, APE1, POLβ, and LIG3 was also observed.

Later, we evaluated the effect of PARP1 knockout on the expression of some the BER-related genes in the HEK293A (HEK293A/P1-KO) cell line obtained using CRISPR/Cas9 technique [

11]. Data of the PCR analysis testify in favor of a homozygous deletion in the PARP1 gene [

11,

12]. Both PARP1 mRNA in cells and amount of PARP1 protein in the whole-cell extract were barely detectable. Transcriptomic analysis revealed more than 4,000 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in HEK293A/P1-KO cells compared to wild-type HEK293A cells. Among DEGs several enzymes involved in the long-patch BER pathway were found to be down-regulated by knockdown of PARP1 [

13].

In this study, we have knocked out the PARP1 gene in the human HEK293FT line using the CRISPR/Cas9 based technique. This line is fast growing isolate derived from human embryonic kidney cells – HEK293T [

14]. The obtained cell clones with putative PARP1 knockout were characterized genetically, biochemically and phenotypically by several approaches. Characterization included: PCR analysis of deletions in genomic DNA, Sanger sequencing of genomic DNA, qPCR analysis of mRNA encoding PARP1, western-blot analysis of whole-cell-extract proteins with anti-PARP1 antibodies and the PAR synthesis in the whole-cell-extracts.

Then we assessed by qPCR in one clone the levels of mRNAs coding other BER-related proteins, namely PARP2, UNG2, APE1, POLβ, LIG3, and XRCC1, which are involved in the short-patch pathway of BER. Simultaneously, we compared the efficiency of uracil removal, AP site cleavage, DNA synthesis, and ligation in the whole-cell extracts of the mutant cells and parental cells in the presence and absence of NAD+.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

TEMED, bis-acrylamide, MgCl2, Tris, SDS, bromophenol blue, NaBH4, bovine serum albumin, dithiothreitol, acrylamide, ammonium persulfate, EDTA, and glycine were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, SG, USA).

[γ-32P]ATP (5000 Ci/mmol) and [α-32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol) were produced in the Laboratory of Biotechnology, Institute of Chemical Biology and Fundamental Medicine SB RAS (ICBFM SB RAS), Russia. Synthetic oligonucleotides including PCR primers were obtained from Laboratory of Medicinal Chemistry, ICBFM SB RAS, Master mix for RT-qPCR BioMaster RT-qPCR SYBR Blue (2×) and BioMaster HS-Taq PCR-Color (2×) for PCR were from Biolabmix (Russia). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to PARP1 were kindly provided by Dr. G.L. Dianov (Institute of Cytology and Genetics, SB RAS, Russia). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked secondary antibodies were obtained from Laboratory of Biotechnology ICBFM SB RAS.

Polynucleotide kinase of T4 phage, E. coli UDG, T4 DNA ligase were purified from E. coli cells overexpressing the corresponding proteins. The plasmids bearing cDNA of human AP endonuclease 1 and rat DNA polymerase β were kindly provided by Dr. S.H. Wilson (NIEHS, NIH, USA). The recombinant proteins Pol β and APE1 were purified as described in [

15,

16], respectively. The vector coding for human PARP1 was a generous gift of Dr. V. Schreiber (ESBS, Illkirch, France). The recombinant PARP1 expressed in the insect cells and purified as described in [

17] was a kind gift from Dr. M. Kutuzov (LBCE, ICBFM SB RAS).

HEK293FT cell line was from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA; Cat. №R70007). The supported laboratory stock was checked for the absence of mycoplasma contamination by PCR. Plasmid pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (PX458) was a gift from Feng Zhang (Addgene plasmid # 48138; http://n2t.net/addgene:48138; RRID: Addgene_48138). pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

2.2. Cultivation of cells

The growth medium for clone selection contained DMEM/F12 1:1 (Servicebio, Wuhan, China), 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin–streptomycin, and 1×GlutaMAX (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

HEK293FT WT and HEK293FT/P1-KO cells were grown in DMEM/F12 1:1 (Servicebio, Wuhan, China) in the presence of 10% FBS (HyClone, USA), 100 unit/mL penicillin (Invitrogen, USA) and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere.

2.3. Generation of PARP1 knockout cells (HEK293FT/P1-KO)

PARP1 knockout HEK293FT clones were obtained as previously described for HEK293A [

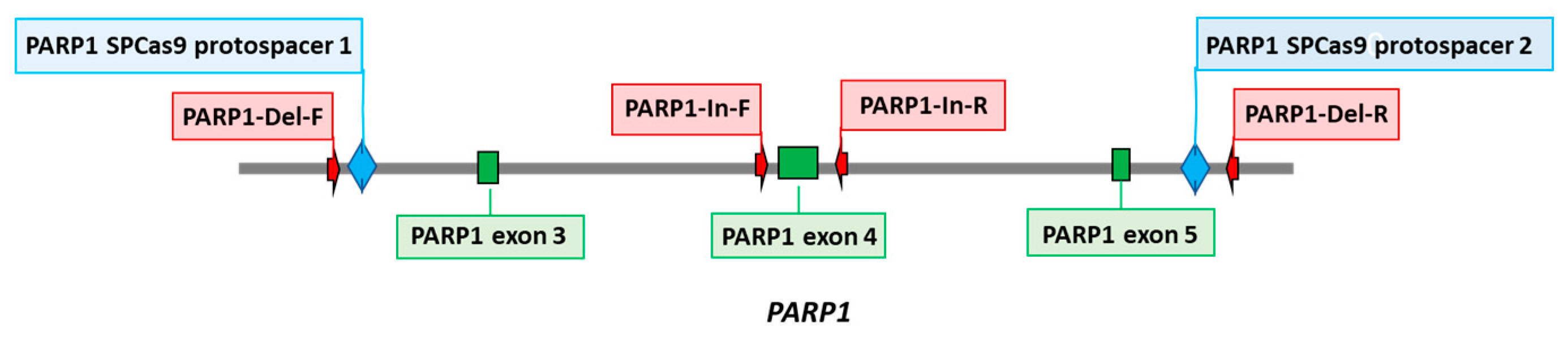

11]. Briefly, two protospacers for DNA sequence deletion that includes 3–5 exons of the PARP1 gene (PARP1-gRNA1 and PARP1-gRNA2,

Table S1) were selected using https: //

www.benchling.com/ (accessed date 1 November 2020). Positions of protospacers are shown in

Figure 1. Corresponding oligonucleotides to express gRNA1 and gRNA2 were cloned into plasmid pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (PX458). HEK293FT cells were transfected with plasmids PARP1-gRNA1 and PARP1-gRNA2 (0.25 µg each) using Lipofectamine 3000 Reagent (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the GFP-positive cell population was enriched by cell sorting using BD FACS Aria III Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Single cell clones grew for two weeks, and genome was analyzed for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletions in PARP1 gene by PCR amplification of the target region. PCR was performed using DNA obtained with QuickExtract™ DNA Extraction Solution (Lucigen, Madison, WI, USA) and the following primers: PARP1-Del-F and PARP1-Del-R for deletions and PARP1-In-F and PARP1-In-R for wild-type allele (

Table 1). The reactions were run on an S1000 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, Singapore) using the following program: 95 ⁰C for 3 min; 35 cycles: 95 ⁰C for 30 s; 60 ⁰C for 30 s; 72 ⁰C for 30 s; and 72 ⁰C for 3 min. The reaction products were resolved in 1% agarose gel with ethidium bromide.

2.4. DNA sequencing

To identify and map deletions in PARP1 gene PCR products obtained using primers PARP1-Del-F and PARP1-Del-R were cloned in the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Ten independent plasmid clones were sequenced by the Sanger method using universal M13 primers at the SB RAS Genomics Core Facility (ICBFM SB RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia).

2.5. Estimation of doubling time

Doubling time for wild type and mutant cells was studied in real time using xCELLigence DP RealTime Cell Analyzer (ACEA Biosciences, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The cells were seeded on 16-well E-plates at a density of 105 cells/well in 150 μL of complete DMEM/F12 medium (Servicebio, Wuhan,China) with 1× GlutaMAX, 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and in the presence of 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in 5% CO2 atmosphere and incubated for nearly 24 h to let cells adhere to the bottom of the plate. The cells were incubated for the next 30 h under standard conditions. Cell index values were measured every 30 min.

2.6. Cell culture cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity of the compounds was examined on HEK293FT WT and PARP1 knockout HEK293FT/P1-KO cells using the MTT test (Dia-m, Novosibirsk, Russia). Cells were seeded in 96-well plates (10000 cells per well) in DMEM/F12 medium (Servicebio, Wuhan, China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 units/mL), and streptomycin (100 µg/mL) (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humid atmosphere. The tested compounds were added to the medium nearly at 30 % confluence. To determine the cytotoxicity of Topotecan (Tpc, Actavis, Sindan Pharma, Romania) and Temozolomide (Tmz, TCI Chemicals, Zwijndrecht, Belgium), the cells were treated with compounds with the indicated concentrations for 72 h. All measurements were repeated minimum twice.

2.7. [32P]–labeling of oligonucleotides and preparation of the BER DNA substrates

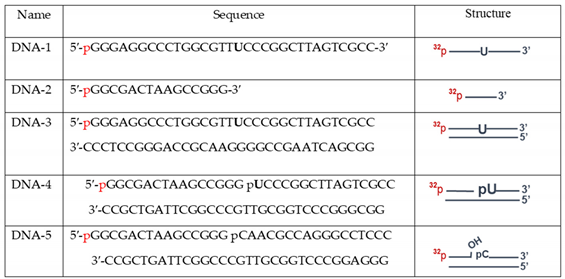

The oligodeoxyribonucleotides DNA-1 or DNA-2 (

Table 1) were the 5′ end labeled with [

32P]phosphate by T4 polynucleotide kinase and then purified by polyacrylamide gel (PAAG)/7 M urea electrophoresis according to [

18].

To obtain DNA duplexes the complementary oligodeoxyribonucleotides were mixed in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 1 mM EDTA at equimolar concentration followed by heating at 97°C for 5 min and slow cooling down to room temperature. The resulting DNA duplexes were analyzed by electrophoresis in 10% polyacrylamide gel under non-denaturing conditions.

2.8. Isolation of total RNA

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to [

19]. The purity of the isolated RNAs was accessed by the ratio of absorbance at 260 nm and 230 nm (A260/230). A ratio of ~1.8-2.0 is generally accepted as “pure” for RNA. For use in qPCR, RNA was additionally treated by DNAse to degrade possible traces of genomic DNA.

2.9. qPCR analysis of mRNA levels in HEK293FT WT and HEK293FT/P1-KO cells

To estimate the relative expression of genes encoding the key short patch BER proteins in HEK293FT WT and HEK293FT/P1-KO cell lines the RT-qPCR analysis was performed. The reaction mixtures (20 μL) contained 0.5 ng/μL of total RNA, 0.5 µM primers, 10 μL of BioMaster RT-qPCR SYBR Blue (2×). RT-qPCR was performed on an LigthCycler96 system (Roche, Switzerland) under the following conditions: 1800 s a reverse transcription at 45°C, 300 s initial denaturation at 95°C, 30 × (10 sec 95°C denaturation, 58°C primer annealing, 10 sec 72°C primer elongation). The fluorescence was recorded during the annealing/elongation step in each cycle. A melting curve analysis was performed at the end of each PCR by gradual increase the temperature from 58 to 95°C while recording the fluorescence. Signal detection was carried out at 84°C for 5 s. A single peak at the melting temperature curve of the PCR products confirmed primers specificity. The RT-qPCR was carried out in triplicate. Housekeeping genes

Gapdh,

B2M, Tubβ, and

ACBT were used as calibrators. Primers were selected using the Primer-BLAST program (NCBI, USA). The primers are listed in

Table S1. For each pair of primers, the amplification efficiency has been found to be in the range of 90-110%.

2.10. Whole-cell extracts (WCEs)

Whole-cell extracts from HEK293FT WT and HEK293FT/P1-KO cells were prepared as described previously [

20]. Protein concentration was measured by Bradford assay [

21]. The extracts were equalized in concentration of total protein and stored in aliquots at −70°C.

2.11. Western blot analysis of PARP1 in the whole-cell extracts (WCEs) of HEK293FT WT and HEK293FT/P1-KO cells

Western blot analysis was performed according to [

22]. In brief, the whole-cell extract proteins, 2.5 µg or PARP1, 0.05 µg were resolved in 12.5% SDS-PAGE [

23] followed by electrotransfer of proteins onto nitrocellulose membrane using Trans-Blot Turbo (Bio-Rad, USA). The membrane was incubated in a solution of primary antibodies (rabbit antibodies to PARP1 at a dilution of 1:1000), then in a solution of secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP). The conjugate was stained using Super Signal West Pico PLUS (Thermo Scientific, USA) according to manufacturer’s recommendation. Chemiluminescence was detected at an Amersham Imager 600 (GE Healthcare, USA).

2.12. Synthesis of [32P]NAD+

The synthesis of radioactive NAD

+ was carried out from [α-

32P]-ATP as described in [

24]. Briefly, the reaction mixtures containing 1 mM ATP, 10 MBq of [α-

32P]ATP, 20 mM MgCl

2, 2 mM β-nicotinamide mononucleotide, and 5 mg/mL nicotinamide nucleotide adenylyltransferase in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) were incubated at 37 °C for 60 min and stopped by heating to 90 °C for 3 min. After removal of a denatured protein by centrifugation, the solution was used as a source of NAD

+ without purification.

2.13. PARP activity assay

The reaction mixtures (10 μL) contained 0.6 A260/mL of activated DNA, 20 μM [32P]NAD+, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 40 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 0.1 mg/mL BSA were assembled on ice. The whole-cell extract proteins at the final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL or 100 nM PARP1 were added as indicated in the figure legends. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 1 min. The reaction was stopped by dropping the aliquot of 4 μL on the Whatman 1 paper filters pre-impregnated with trichloroacetic acid (TCA). PAR attached to proteins was precipitated on the filters in the presence of TCA. To remove unreacted NAD+, the dried filters were washed 3 times with 150 mL of 5% ice-cold TCA, the rest of TCA was removed from paper by 90% ethanol, and filters were dried and subjected to autoradiography for quantification.

2.14. Quantification of the results of autoradiography

After separation of the products, the PAAG gels were dried and then subjected to autoradiography using Biomolecular Imager Typhoon FLA 9500 (GE Healthcare, USA). Radioactivity of the products was quantitated using software “Quantity One” (Bio-Rad, USA).

2.15. Preparations of DNA substrates with apurinic/apyrimidinic sites or 5ʹ-dRP residues

The uracil residue in the substrates was removed immediately before experiments by E. coli UDG. The reaction mixture contained 10 mM TE buffer pH 7.5, 1 μM uracil-containing DNA and UDG, 0.1 unit/μL. The reaction was carried out at 37 °C for 20 min.

2.16. Tests for the BER enzyme activity in the whole-cell extracts (WCEs)

2.16.1. The uracil excision activity

The reaction mixtures (10 μL) contained the following components: 0.1 μM [

32P]-labeled uracil-containing DNA (Table 2, DNA-1 or DNA-3), proteins of the whole-cell extract at the final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL or 0.1 unit/μL E. coli UDG, 20 mM Tris-HCl, (pH 8.0, 40 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, 0.1% Nonidet P-40), 400 μM NAD

+ (where specified). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37 °C. Aliquots of 2 µL were transferred at 2, 5, and 10 min into the tubes that contained 2 µL of 100 mМ NaOH with the following incubation at 60 °C for 10 min. Then the reaction mixtures were supplemented with an equal volume of mixture containing 90% formamide and 10 mM EDTA and heated at 97 °C for 15 min followed by the products separation in 20% PAAG with 7 M urea and 10% formamide [

18]. The gels were dried and subjected to autoradiography.

2.16.2. The AP site cleavage activity

The reaction mixtures (10 µL) contained the following components: 0.1 µM [32P]-labeled uracil containing DNA duplex (DNA-3, Table 2), whole-cell extract proteins at the final concentration of 0.01 mg/mL or 1 nM APE1, 5 mM MgCl2, buffer components (10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, 0.02% Nonidet P-40, 0.1 mg/mL BSA and 400 μM NAD+ (where specified)). AP sites in DNA were generated by UDG immediately before the test of AP endonuclease activity. The reaction was carried out at 37 °C, the 2 μL aliquots were withdrawn at 2, 4, and 8 min; then the reaction was stopped by equal volume of mixture containing 100 mM methoxyamine and 50 mM EDTA followed by incubation for 30 min at 0°C. After that the samples were supplemented with an equal volume of mixture containing 90% formamide and 10 mM EDTA and incubated at 0°C for 30 min. The efficiency of AP site cleavage by the lyase mechanism was assayed similarly, except that the reaction mixture contained 20 mM EDTA instead of magnesium ions and incubation time was 10, 15, and 30 min. Further analysis was performed as described in the previous section.

2.16.3. DNA polymerase activity

The reaction mixtures (10 µL) contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM dNTPs, 100 nM 5′-[32P]-labeled DNA duplex (DNA-4, Table 2), 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 5% glycerol, and 0.5 mg/ml of whole-cell-extract proteins or 50 nM Polβ, and 400 μM NAD+ (where specified). Prior to DNA synthesis, DNA-5 was treated by UDG to obtain DNA substrate for SP-BER containing 5ʹ-dRP residue at the downstream oligonucleotide. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37 °C. Aliquots of 2 µL were taken at 5, 10, and 15 min and supplemented with 1 μL of 25 mM EDTA to stop the reaction. Further analysis was performed as described above.

2.16.4. DNA ligase activity

The reaction mixtures (10 µL) contained: buffer components (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1 mg/mL BSA), 0.1 μM [32P]-labeled DNA duplex (DNA-5, Table 2), 0.05 mg/mL extract or 0.1 u/μL T4 DNA ligase, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 400 µM NAD+ (where specified). Samples were incubated at 37 °C. Aliquots of 2 µL were taken at 5, 15, and 30 min and mixed with 2 µL of 90% formamide and 10 mM EDTA. Further analysis was performed as described above.

2.17. Cell Culture Cytotoxicity Assay

Cytotoxicity of the compounds was examined on HEK293FT WT and PARP1 knockout HEK293FT/P1-KO cells using the MTT test (Dia-m, Novosibirsk, Russia). Cells were seeded in 96-well plates (10000 cells per well) in DMEM/F12 medium (Servicebio, Wuhan, China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen), penicillin (100 units/mL), and streptomycin (100 µg/mL) at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humid atmosphere. The tested compounds were added to the medium nearly at 30 % confluence. To determine the cytotoxicity of Topotecan (Tpc, Actavis, Sindan Pharma, Romania) and Temozolomide (Tmz, TCI Chemicals, Zwijndrecht, Belgium), the cells were treated with compounds with the indicated concentrations for 72 h. All measurements were repeated minimum twice.

3. Results and Dicussion

PARP1 is known as an abundant protein with many pleiotropic functions in cells. The role of PARP1 in different ways of DNA repair has been previously studied using various experimental models, which have their own advantages and disadvantages. One of the convenient and productive ways to analyze an influence of PARP1 on the activity of the DNA repair enzymes at each step of the BER process consists in comparison of their activities in the reconstituted system containing DNA intermediate with lesions distinctive for this step of DNA repair and whole-cell extracts from parental cells and cells devoid of PARP1. Use of human cells with complete absence of PARP1 opens up new possibilities to study the role of this protein in the BER system at the level of the proteins themselves and/or of their activities as well as at the level of the mRNAs encoding them.

3.1. Generation and characterization of HEK293FT/P1-KO cells

The PARP1 knockout HEK293FT clones (HEK293FT/P1-KO) were generated essentially as previously described for PARP1 knockout HEK293A cells [

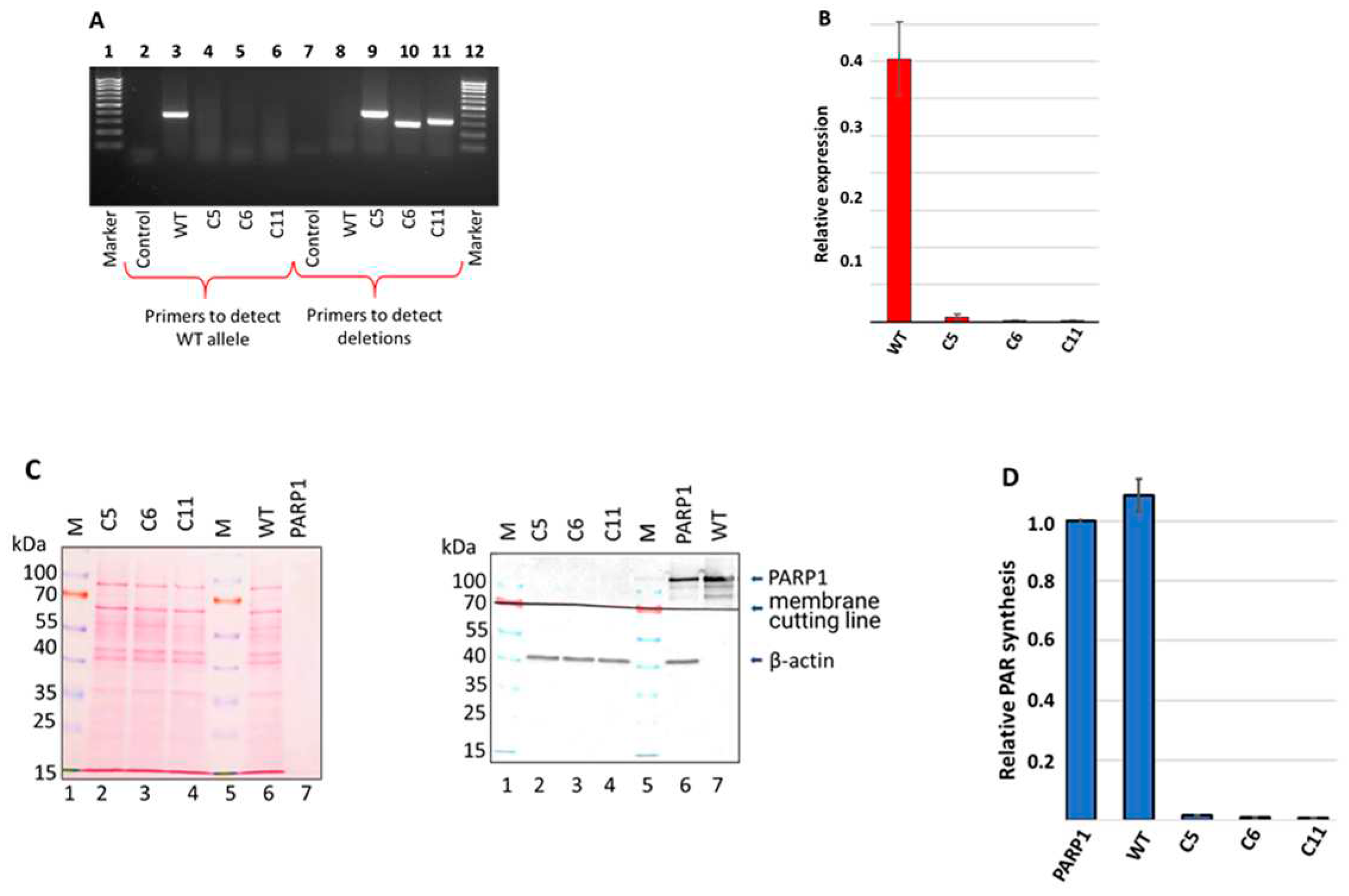

11]. Positions of protospacers for the deletion of DNA sequence including 3–5 exons of the PARP1 gene, which encodes the part of DNA-binding domain, and the primer sequences for detection of deletions, are shown in the scheme (

Figure 1).

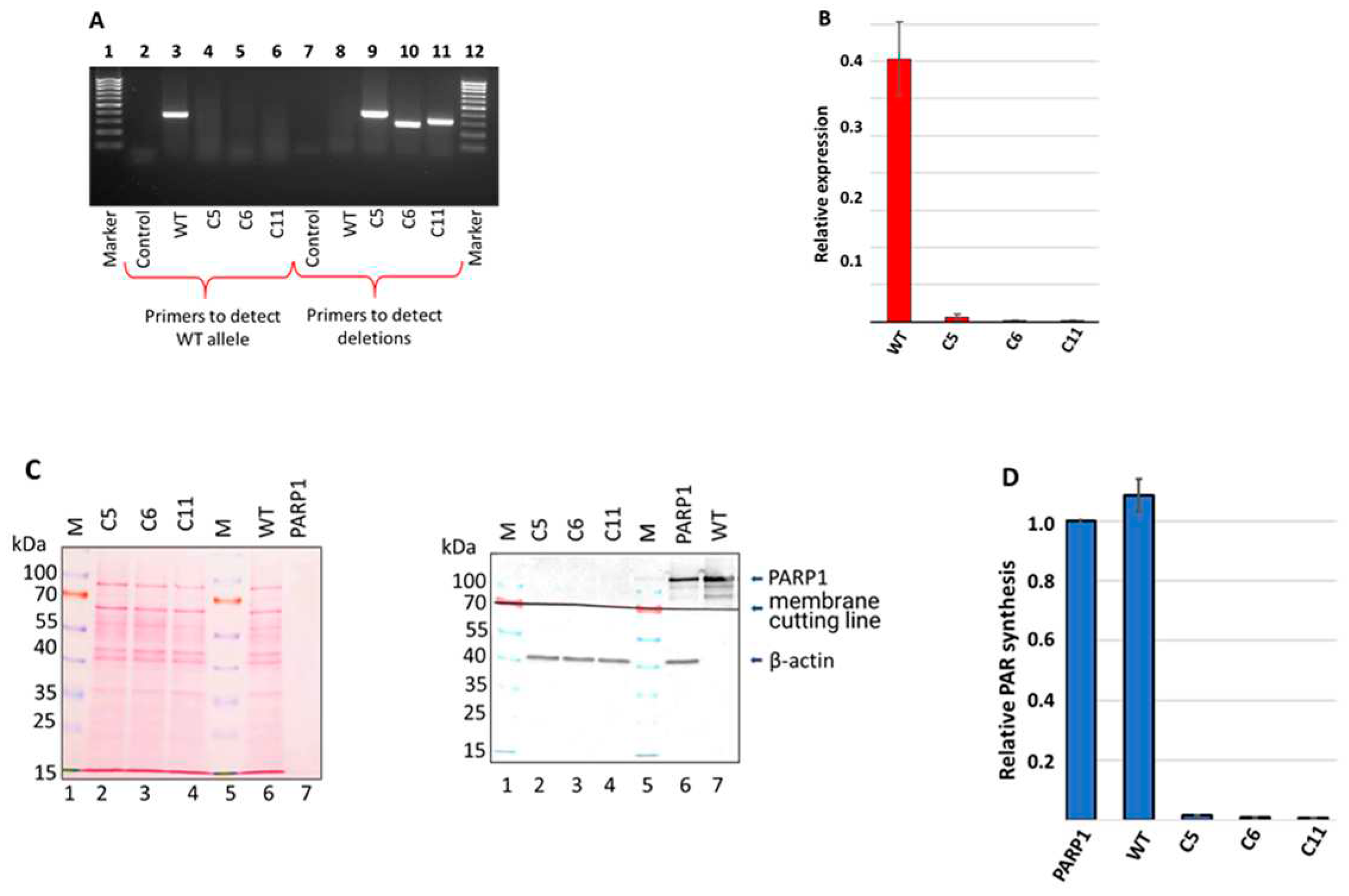

About one week after transfection of HEK293FT WT cells with corresponding plasmids, the individual clones were picked for genotype analysis around the gRNA targeting site by PCR analysis of genomic DNA. Three clones, further designated as C5, C6, and C11, in which PCR analysis did not reveal the product characteristic for wild type genomic (

Figure 3A, lanes 3-6), were selected for further reproduction and study.

Figure 2.

Analysis of PARP1 content in HEK293FT WT and HEK293FT/P1-KO clones. (A). PCR analysis of genomic DNA of selected clones. Lanes 1 and 12 – 100-1000 bp DNA ladder; lanes 2–6 – products of PCR with primers for detection of the PARP1 wild type allele; lanes 7–11 products of PCR with primers for detection of deletion in the PARP1 gene. (B). Quantification of PARP1 mRNA amount in the cells. The results are shown as mean ± standard deviation as obtained in three independent experiments. (C). Western blot analysis of PARP1 protein in whole-cell extracts of the cells. β-actin was used as internal control of loading. Left panel shows Ponceau S staining of the membrane. Right panel – antibody detection of PARP1 and β-actin. (D). Efficiency of PAR synthesis in the whole-cell extracts. The relative level of PAR synthesized by endogenous PARPs for 1 min at 37 °C is represented. In each experiment, the amount of PAR synthesized by the extract PARPs was normalized to that synthesized by 100 nM recombinant PARP1. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments.

Figure 2.

Analysis of PARP1 content in HEK293FT WT and HEK293FT/P1-KO clones. (A). PCR analysis of genomic DNA of selected clones. Lanes 1 and 12 – 100-1000 bp DNA ladder; lanes 2–6 – products of PCR with primers for detection of the PARP1 wild type allele; lanes 7–11 products of PCR with primers for detection of deletion in the PARP1 gene. (B). Quantification of PARP1 mRNA amount in the cells. The results are shown as mean ± standard deviation as obtained in three independent experiments. (C). Western blot analysis of PARP1 protein in whole-cell extracts of the cells. β-actin was used as internal control of loading. Left panel shows Ponceau S staining of the membrane. Right panel – antibody detection of PARP1 and β-actin. (D). Efficiency of PAR synthesis in the whole-cell extracts. The relative level of PAR synthesized by endogenous PARPs for 1 min at 37 °C is represented. In each experiment, the amount of PAR synthesized by the extract PARPs was normalized to that synthesized by 100 nM recombinant PARP1. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments.

Data of PCR analysis with specific primers confirmed presence of deletions in C5, C6, and C11 clones (

Figure 3A, lanes 8-11).

Genomic DNA of three selected cell clones (C5, C6, and C11) was sequenced by the Sanger method. Data are shown in

Figure S1. In all three clones, analysis revealed extended deletions differing in positions and length. Sequencing data demonstrate that in each clone the only one type of deletion was generated which may be related, for instance, with the presence of single allele coding for PARP1 in the cell genome. Indeed, it is reported [

25] that HEK293, the progenitor cell line for HEK293FT, contains the only one copy of Chr 1 harboring the PARP1 gene, while in another study [

26] three copies were found.

After confirming deletions in the PARP1 gene at the genome level, we evaluated by qPCR the level of mRNA coding PARP1 (

Figure 2B). No significant amount of mRNA coding PARP1 detected in all three HEK293FT/P1-KO cell clones.

Next, we confirmed the PARP1 gene knockout at the protein level by the western blot analysis. The analysis of the whole-cell extracts of HEK293FT/P1-KO clones and HEK293FT WT cells did not reveal detectable amount of PARP1 in mutant cells (

Figure 2C, compare lanes 2-4 and lane 6).

To further characterize the mutant cell lines, the efficiency of poly(ADP) ribose (PAR) synthesis catalyzed by endogenous PARPs of whole-cell extracts. [

32P]-labelled NAD

+ and activated DNA as a cofactor were used (

Figure 2D). We choose one minute time point, which is in the linear part of the kinetic curve of PAR synthesis by the endogenous PARPs of WCEs, on the base of preliminary study data. In each experiment, the amount of PAR synthesized in the cell extracts were normalized on that of synthesized by 100 nM recombinant PARP1. As expected, practically no synthesis of PAR was detected in the extracts of HEK293FT/P1-KO cells. As a whole, these results are in full agreement with known main contribution of PARP1 into PAR synthesis in the cells [

3,

27,

28,

29]. Thus, obtained 3 clones of HEK293FT/P1-KO do not express detectable amount of PARP1.

Doubling time of HEK293FT/P1-KO clones and HEK293FT WT cells was estimated in real time using the xCELLigence device. Data is represented in (

Figure S2.) The cells’ doubling time was: 9.6±0.1 h for WT, 9.3±0.3 h for C5, 10.0±0.1 h for C6, and 13.2±0.3 h for C11.

Data of topotecan and temozolomide influence on cells viability according MTT test are shown in

Figure S3. As expected PARP1 knockout cell clones were somewhat more sensitive to topotecan than wild type HEK293FT cells. Increased sensitivity of PARP1 knockout cells to the action of topotecan was previously demonstrated for HEK293A line [

11]. Obtained HEK293FT/P1-KO clones did not demonstrate significant difference in sensitivity to temozolomide with parental cells.

Cell clone C5 was selected as a representative of HEK293FT/P1-KO for the following biochemical study of PARP1 influence on the BER system. All data below denoted by HEK293FT/P1-KO cells refer to clone C5.

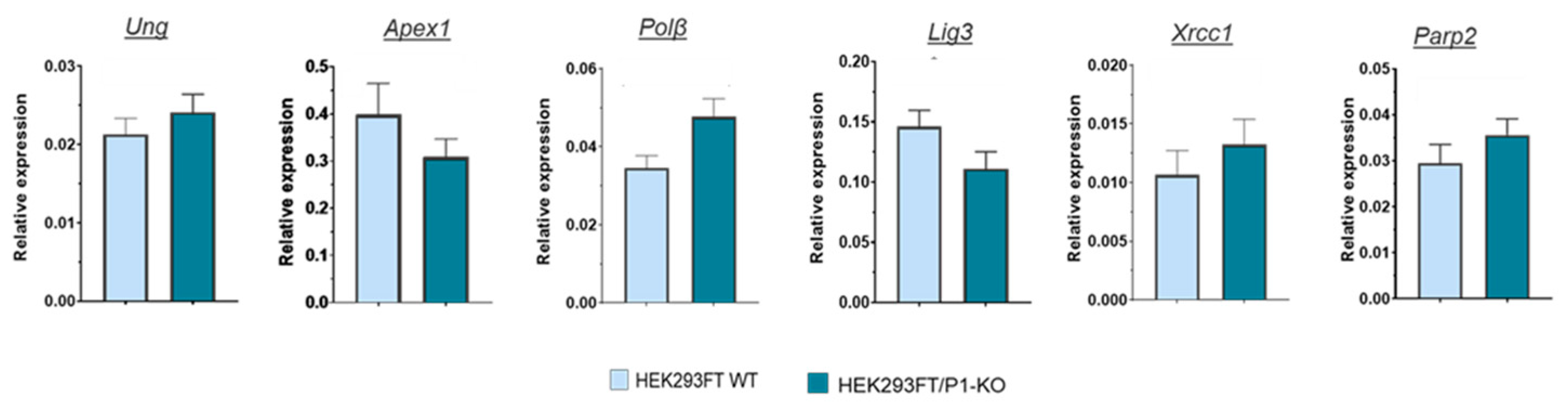

3.2. Comparison of Parp2, Ung2, Apex1, Polβ, and XRCC1 mRNA relative expression

Taking into account known participation of PARP1 in regulation of pre-mRNA splicing and in maintenance of mRNA stability/decay [

30] and involvement in transcriptional regulation [

31], we were intended to evaluate the impact of the PARP1 full absence in the cells on the levels of mRNAs encoding the proteins involved in the BER process. To this end using the preparation of RNA obtained from HEK293FT WT and HEK293FT/P1-KO cells (clone C5), we compared relative amount of mRNAs coding PARP2, Ung2, APE1 (Apex1), DNA polymerase β (Polβ), DNA ligase III (Lig3), and XRCC1 in the cells above by qPCR analysis.

As a whole, no strong influence of PARP1 knockout on the levels of mRNAs coding the SP BER proteins was found. This fact testifies against influence of PARP1 on the short-patch BER system on the mRNA level. Interestingly, transcriptomic analysis of HEK293A PARP1 knockout reveals down regulation of mRNA coding Polβ [

23], while in current study we detected slight increase in the level of mRNA coding it.

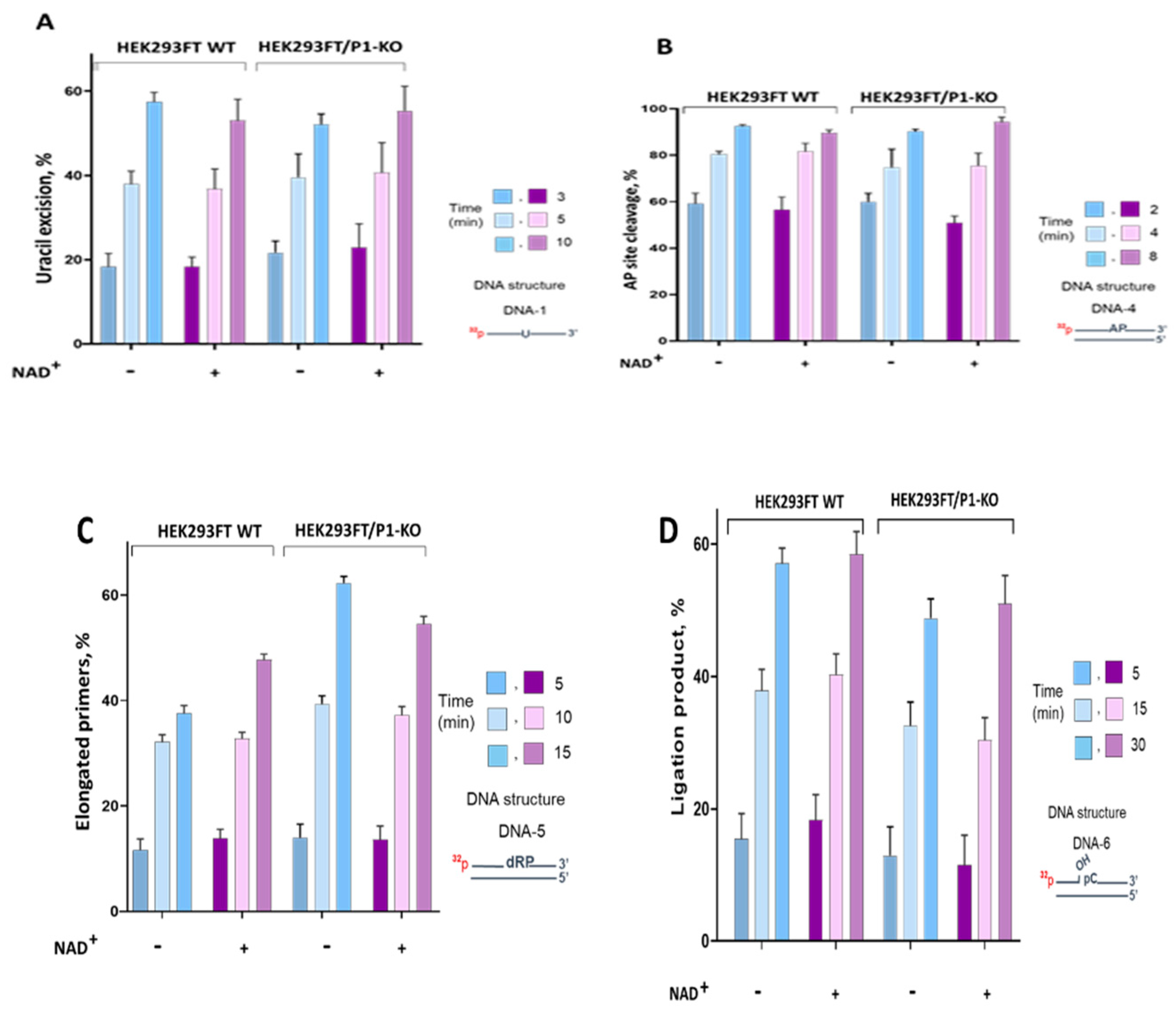

3.3. Influence of PARP1 presence in WCEs on the efficiency of the BER reactions

To analyze the impact of PARP1 on the efficiency of the short-patch BER reactions catalyzed by endogenous enzymes we compared the enzyme activities by functional tests: excision of uracil, AP site processing, DNA synthesis and DNA ligation. In functional assays the

32P-labelled DNA structures imitating intermediates of particular stage and the whole-cell extract from HEK293FT WT and HEK293FT/P1-KO cells were used. The examples of electrophoretic analysis of the products of the BER reactions are shown in

Figure S4. To evaluate the influence of PARylation all functional tests were performed in parallel in the absence and presence of NAD

+. It should be noted that when determining the effect of PAR synthesis on the activity of endogenous enzymes of the extracts the DNA substrate characteristic for a certain stage of BER acted as a cofactor DNA, which is necessary for PARP1 activation. Comparison of cofactor characteristics of activated DNA, traditionally used in tests for determining PARP1 activity, and 0.1 μM BER DNA substrates, used in the tests of the BER enzyme activity, revealed the comparable levels of PAPR1 activation (

Figure S5).

3.3.1. Uracil removal

The uracil residues in genomic DNA may appear due to occasional substitution of thymine during DNA synthesis or as a result of spontaneous and enzymatic cytosine deamination. It is thought that 70–200 spontaneous cytosine deamination events occur in a single cell daily [

32]. Three types of uracil-DNA glycosylases were found in higher eukaryotic cells [

33]: single strand-selective monofunctional uracil glycosylase (SMUG), mitochondrial UNG1, and nuclear UNG2. Uracil N-glycosylases UNG2 and SMUG1 initiate error-free BER in most DNA contexts [

33].

No statistically significant difference in mRNA level of UNG2 between HEK293FT WT and HEK293FT/P1-KO cells was detected by qPCR. Interestingly, that in HEK293A cells PARP1 knockout leads, as determined by transcriptomic analysis, to decreased expression of four DNA glycosylases with another uracil DNA glycosylase, SMUG1, being among them [

23].

We compared efficiency of uracil removal from both double-strand and single-strand DNA (DNA-1 and DNA-3,

Table 1). To track the uracil excision DNA intermediate was subjected to alkaline treatment, which splits sugar-phosphate backbone at the position of AP site arising after uracil removal. An example of electrophoretic analysis of uracil excision products by endogenous uracil DNA glycosylases of WCEs on single-strand and double-strand substrates are shown in

Figure S3 A.

Summarized data of uracil excision by the WCE uracil DNA glycosylases in the presence and the absence of NAD

+ are shown in

Figure 4A.

The efficiency of uracil excision by the extract uracil DNA glycosylases was about 10% higher on single-strand DNA compared to double-strand DNA (

Figure S4 A). This efficiency was not influenced by the presence or absence of PARP1. Additionally, the presence of NAD

+ in the reaction mixtures did not affect the efficiency of uracil removal (

Figure 4A). Therefore, there was no evidence of PARP1 influencing uracil excision in WCEs.

The next step of SP BER is processing of AP site. AP site can occur via several ways: via hydrolysis catalyzed by specific apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases and tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1 or AP-lyase dependent splitting mechanism [

34]. Hydrolysis is known to be the predominant way of AP site processing in mammalian cells [

35] with APE1 being the enzyme responsible for cleavage of the majority of AP sites [

36]. Our study of PARP1 and APE1 interplay at the earlier BER DNA intermediate – an AP site containing DNA - in the system reconstituted from individual proteins have demonstrated the inhibition of APE1 activity by PARP1, both on naked DNA and in the context of reconstituted nucleosome core particles [

37,

38,

39]. Auto(PARylation) of PARP1 in the presence of NAD

+ resulted in a decrease of its inhibitory effect.

To analyze the processing of AP site the uracil-containing double-stranded DNA (

Table 1, DNA-3) was converted to an AP site containing substrate immediately prior to experiment by treatment with

E. coli uracil DNA glycosylase. An example of electrophoretic analysis of the products arose after AP site cleavage by endogenous enzymes of WCEs are shown in

Figure S4 B. Summarized data of AP site cleavage by the WCE enzymes in the presence and the absence of NAD

+ are represented in

Figure 4B. AP site processing by the extracts of HEK293FT cells did not differ between WT and P1/KO cells, although the APE1 mRNA level was slightly higher in WT cells (

Figure 3). The presence of NAD

+ did not interfere with AP site processing in WCEs of mutant and parental cells.

APE1-independent activity was estimated by testing AP site cleavage in the presence of EDTA to bind Mg

2+ ions, which are absolutely required for the APE1 functioning [

36]. The efficiency of AP site cleavage was about 4-6%.

DNA synthesis at the DNA with the gap formed after AP site processing is the next BER step that is conducted by DNA polymerases with Polβ being the main DNA polymerase of SP BER [

6]. Prior studies of our laboratory demonstrated that in the system reconstructed from purified PARP1 and Polβ, PARP1, which possesses high affinity to DNA containing single-strand breaks, can inhibit Polβ activity, but inhibitory effect is more pronounced on the substrate of LP BER than on the SP BER substrate [

40].

We compared DNA polymerase activity in WCEs of HEK293FT WT and HEK293FT/P1-KO cells (Figure 4S C,

Figure 4 C). The data demonstrates that PARP1 deletion in cells leads to 10-15% increase in the primer elongation by the extract enzymes. Slight increase in the level of the mRNA coding Polβ was observed in HEK293FT/P1-KO cells (

Figure 3) that can result in the higher concentration of the enzyme in this extract. Thus, this increase may be caused both by higher Polβ concentration and lack of competition between Polβ and PARP1. When NAD

+ is present, no reliable influence of PARylation on DNA synthesis was observed neither in HEK293FT WT nor in HEK293FT/P1-KO WCEs. Weak influence of PARylation on DNA synthesis catalyzed on the DNA intermediates of SP and LP pathways by endogenous DNA polymerases of WCEs obtained from mouse or naked mole rat fibroblasts or HEK293T cells on the DNA intermediates of SP and LP pathways of BER [

24]. It should be noted that WCEs of these cells demonstrated striking difference in the efficiency of PAR synthesis while the efficiency of DNA synthesis was comparable in all WCEs.

The last SP BER step – ligation – is conducted by ATP-dependent DNA ligase 3α (LIG3). LIG3 forms stable functionally active complex with the architectural XRCC1 protein [

41]. XRCC1 has no catalytic activity, but forms binary and ternary complexes with several BER enzymes (proteins) to provide their concerted action, which to a great extent, is determined by the XRCC1 capabilities of binding with BER proteins, undergoing PARylation, and binding with PAR [

41,

42].

We estimated DNA ligase activity in the whole-cell extracts using nicked DNA (DNA-5,

Table 1). Efficiency of DNA ligation was somewhat lower in WCE of HEK293FT/P1-KO cells (

Figure 4D). The lower efficiency in ligation could be related with the observed decrease of mRNA encoding LIG3 (

Figure 3). Again, there was no influence of NAD

+ presence irrespectively of the extract source, wild type or PARP1 knockout cells.

4. Conclusions

The current understanding of the roles of DNA-activated PARPs, such as PARP1 and PARP2, in BER is still being actively studied. The majority of available data suggests that PARP1 may have no influence or a negative impact on BER, as it competes with BER proteins for the same DNA intermediates. However, this competition can be overcome through PARylation [

39,

40,

43]. On the other hand, it has been suggested that PAR may play a role in the formation of cellular compartments by interacting with BER proteins [

2,

44]. Additionally, the role of PARP2 in the regulation of BER should not be underestimated, especially considering the discovery of proteins like Histone Parylation Factor 1 (HPF1), which can considerably enhance the activity of PARP2 [

45,

46]. This phenomenon may allow PARP2 to substitute for PARP1 in certain processes. Interestingly, the absence of PARP1 in cells does not significantly affect the mRNA levels of BER enzymes or the activities of the main short-patch BER enzymes. It appears that the relatively low effects of PARP1 may contribute to fine-tuning the activities of BER enzymes in the absence of severe cell stress. This aligns with the current understanding that the BER system has redundant capacity, and excess non-demanded proteins are deactivated, for example through the ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis system [

47,

48].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S.D., A.A.M., S.N.K., S.M.Z., and O.I.L.; methodology, N.S.D., A.A.M. S.N.K, and E.A.M.; analysis, E.S.I, S.P.M., E.A.M.; investigation, N.S.D., A.S.K., E.A.M., A.A.Y., and E.S.I.; resources, S.M.Z., O.I.L., and S.N.K; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.K.; N.S.D., and S.N.K.; writing—review and editing, S.N.K., S.M.Z., O.I.L.; visualization, N.S.D., E.S.I., and S.N.K.; supervision, S.N.K. and O.I.L.; project administration, O.I.L.; funding acquisition, S.N.K. and O.I.L.

Funding

Main part of the study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project no. № 19-04-00204) for and partially by the Russian state-funded project for ICBFM SB RAS (Grant Number 121031300041-4) for creation of PARP1 knockout cell lines. .

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lüscher, B.; Ahel, I.; Altmeyer, M.; et al. ADP-ribosyltransferases, an update on function and nomenclature. FEBS J. 2021, 289, 7399-7410. [CrossRef]

- Lavrik, O.I. PARPs’ impact on base excision DNA repair, DNA Repair (Amst.). 2020, 93, 102911. [CrossRef]

- Alemasova, E.E.; Lavrik O.I. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by PARP1: reaction mechanism and regulatory proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 3811–3827. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Hernandez, K.; Rodriguez-Vargas, J.M.; Schreiber, V.; Dantzer, F. Expanding functions of ADP-ribosylation in the maintenance of genome integrity. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 63, 92–101. [CrossRef]

- Khodyreva, S.N. and Lavrik, O.I. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 as a key regulator of DNA repair, Mol. Biol. (Moscow). 2016, 50, 580–595. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, K.H. and Sobol R.W. A unified view of base excision repair: lesion-dependent protein complexes regulated by post-translational modification. DNA Repair (Amst.). 2007, 6, 695–711. [CrossRef]

- Svilar, D.; Goellner, E.M.; Almeida, K.H. and Sobol, R.W. Base excision repair and lesion-dependent subpathways for repair of oxidative DNA damage. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 14, 2491–2507. [CrossRef]

- Caldecott, K.W. Mammalian DNA base excision repair: dancing in the moonlight, DNA Repair (Amst.). 2020, 93, 102921. [CrossRef]

- Baiken, Y.; Kanayeva, D.; Taipakova, S.; Groisman, R.; Ishchenko, A.A.; Begimbetova, D.; Matkarimov, B.; Saparbaev, M. Role of base excision repair pathway in the processing of complex DNA damage generated by oxidative stress and anticancer drugs. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 22, 617884. [CrossRef]

- Ilina, E.S.; Kochetkova, A.S., Belousova, E.A.; Kutuzov, M.M.; Lavrik, O.I.; Khodyreva, S.N. Influence of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 level on the status of base excision repair in human cells Mol Biol (Mosk). 2023, 57, 285-298. PMID: 37000656.

- Dyrkheeva, N.S.; Filimonov, A.S.; Luzina, O.A.; Orlova, K.A.; Chernyshova, I.A.; Kornienko, T.E.; Malakhova, A.A.; Medvedev, S.P.; Zakharenko, A.L.; Ilina, E.S.; Anarbaev, R.O.; Naumenko, K.N.; Klabenkova, K.V.; Burakova, E.A.; Stetsenko, D.A.; Zakian, S.M.; Salakhutdinov, N.F.; Lavrik O.I. New hybrid compounds combining fragments of usnic acid and thioether are inhibitors of human enzymes TDP1, TDP2 and PARP1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11336. [CrossRef]

- Dyrkheeva, N.S.; Malakhova, A.A.; Zakharenko, A.L.; Okorokova, L.S.; Shtokalo, D.N.; Pavlova, S.V.; Medvedev, S.P.; Zakian, S.M.; Nushtaeva, A.A.; Tupikin, A.E.; Kabilov, M.R.; Khodyreva, S.N.; Luzina, O.A.; Salakhutdinov, N.F.; Lavrik, O.I. Transcriptomic analysis of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated PARP1-knockout cells under the influence of topotecan and TDP1 inhibitor. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 5148. [CrossRef]

- Zakharenko, A.L.; Malakhova, A.A.; Dyrkheeva, N.S.; Okorokova, L.S.; Medvedev, S.P.; Zakian, S.M.; Kabilov, M.R.; Tupikin, A.A.; Lavrik, O.I. PARP1 gene knockout suppresses expression of DNA base excision repair genes. Dokl. Biochem. Biophys. 2023, 508. 6–11. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Xu, W.W; Jiang, S.; Yu, H.; Poon, H.F. The Scattered Twelve Tribes of HEK293. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2018, 11, p. 621–623. [CrossRef]

- Drachkova, I.A.; Petruseva, I.O.; Safronov, I.V.; Zakharenko, A.L.; Shishkin, G.V.; Lavrik, O.I.; Khodyreva, S.N. Reagents for modification of protein-nucleic acids complexes. II. Site-specific photomodification of DNA-polymerase beta complexes with primers elongated by the dCTP exo-N-substituted arylazido derivatives. Bioorg. Khim. (Mosc.). 2001, 27, 197–204. PMID: 11443942.

- Lebedeva, N.A.; Khodyreva, S.N.; Favre, A.; Lavrik, O.I. AP endonuclease 1 has no biologically significant 3′-5′-exonuclease activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 300, 182–187. PMID: 12480540.

- Amé, J.C.; Kalisch, T.; Dantzer, F. & Schreiber, V. Purification of recombinant poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 780, 135–152. PMID: 21870259. [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Fritsch, E.F.; Maniatis, T. Molecular Cloning: a Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press., 1989, 2nd Ed.

- Rio, D.C.; Ares, M.Jr.; Hannon, G.J.; Nilsen, T.W. Purification of RNA using TRIzol (TRI Reagent). Cold Spring Harb. Protoc., 2010, pdb.prot.5439.

- Biade, S.; Sobol, R.W.; Wilson, S.H.; Matsumoto, Y. Impairment of proliferating cell nuclear antigen-dependent apurinic/apyrimidinic site repair on linear DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 898–902. [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.A. Rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. PMID: 942051. [CrossRef]

- Ilina, E.S.; Lavrik, O.I. Khodyreva, S.N. Ku antigen interacts with abasic sites. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008, 1784, 1777-1785. [CrossRef]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970, 277, 680–685. [CrossRef]

- Kosova, A.A.; Kutuzov, M.M.; Evdokimov, A.N.; Ilina, E.S.; Belousova, E.A.; Romanenko, S.A.; Trifonov, V.A.; Khodyreva, S.N.; Lavrik O.I. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation and DNA repair synthesis in the extracts of naked mole rat, mouse, and human cells. Aging (Albany NY). 2019, 11, 2852–2873. [CrossRef]

- Stepanenko, A.; Andreieva, S.; Korets, K.; Mykytenko, D.; Huleyuk, N.; Vassetzky, Y.; Kavsan, V. Step-wise and punctuated genome evolution drive phenotype changes of tumor cells. Mutat. Res. 2015, 771, 56–69. [CrossRef]

- Binz, R.L.; Tian, E.; Sadhukhan, V.; Zhou, D.; Hauer-Jensen, M.; Pathak, R. Identification of novel breakpoints for locus- and region-specific translocations in 293 cells by molecular cytogenetics before and after irradiation. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 10554. [CrossRef]

- Langelier, M.F.; Eisemann, T.; Riccio, A.A.; Pascal, J.M. PARP family enzymes: regulation and catalysis of the poly(ADP-ribose) posttranslational modification. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2018, 53, 187−198. PMID: 30481609. [CrossRef]

- Hanzlikova, H.;4 Gittens, W.; Krejcikova, K.; Zeng, Z.; Caldecott, K.W. Overlapping roles for PARP1 and PARP2 in the recruitment of endogenous XRCC1 and PNKP into oxidized chromatin. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 2546–2557. [CrossRef]

- Suskiewicz, M.J.; Palazzo, L.; Hughes, R. and Ahel, I. Progress and outlook in studying the substrate specificities of PARPs and related enzymes. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 2131–2142. [CrossRef]

- Matveeva, E.A.; Mathbout, L.F.; Fondufe-Mittendorf, Y.N. PARP1 is a versatile factor in the regulation of mRNA stability and decay. Sci. Reports. 2019, 91, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.L.; Ren, E.C. Functional aspects of PARP1 in DNA repair and transcription // Biomolecules. 2012, 2, 524. PMID: 24970148. [CrossRef]

- Doseth, B.; Ekre, C.; Slupphaug, G.; Krokan, H.E.; Kavli, B. Strikingly different properties of uracil DNA glycosylases UNG2 and SMUG1 may explain divergent roles in processing of genomic uracil. DNA Repair (Amst.). 2012,11, 587−593. [CrossRef]

- Doseth, B.; Visnes, T.; Wallenius, A.; Ericsson, I.; Sarno, A.; Pettersen, H.S.; Flatberg, A.; Catterall, T.; Slupphaug, G.; Krokan, H.E.; Kavli, B. Uracil-DNA glycosylase in base excision repair and adaptive immunity: Species differences between man and mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 16669–16680. PMID: 21454529. [CrossRef]

- Khodyreva, S.; Lavrik, O. Non-canonical interaction of DNA repair proteins with intact and cleaved AP sites. DNA Repair (Amst). 2020, 90, 102847. [CrossRef]

- Mol, C.D.; Hosfield, D.J.; Tainer, J.A. Abasic site recognition by two apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease families in DNA base excision repair: the 3’ ends justify the means. Mutat. Res. 2000, 460, 211–229. PMID: 10946230. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.M.; Barsky, D. The major human abasic endonuclease: formation, consequences and repair of abasic lesions in DNA. Mutat. Res. 2001, 485, 283–307. [CrossRef]

- Sukhanova, M.V.; Khodyreva, S.N.; Lebedeva, N.A.; Prasad, R.; Wilson, SH.; Lavrik. O.I. Human base excision repair enzymes apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease1 (APE1), DNA polymerase beta and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1: interplay between strand-displacement DNA synthesis and proofreading exonuclease activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 1222–1229. PMID: 15731342. [CrossRef]

- Khodyreva, S.N.; Prasad, R.; Ilina, E.S.; Sukhanova, M.V.; Kutuzov, M.M.; Liu, Y.; Hou, E.W.; Wilson, S.H.; Lavrik, O.I. Apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) site recognition by the 5’-dRP/AP lyase in poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2010, 107, 22090-22095. [CrossRef]

- Kutuzov, M.M.; Belousova, E.A.; Kurgina, T.A.; Ukraintsev, A.A.; Vasil’eva, I.A.; Khodyreva, S.N.; Lavrik, O.I. The contribution of PARP1, PARP2 and poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation to base excision repair in the nucleosomal context. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 4849. [CrossRef]

- Sukhanova, M.; Khodyreva, S.; Lavrik O. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 regulates activity of DNA polymerase beta in long patch base excision repair. Mutat. Res. − Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2010, 685, 80−89. [CrossRef]

- Caldecott, K.W. XRCC1 protein; form and function. DNA Repair (Amst.). 2019. 81, 102664. PMID: 31324530. [CrossRef]

- Moor, N.A.; Lavrik, O.I. Protein-protein interactions in DNA base excision repair. Biochemistry (Moscow). 2018, 83, 411–422. PMID: 29626928. [CrossRef]

- Kutuzov, M.M.; Khodyreva, S.N.; Amé, J.C.; Ilina E.S.; Sukhanova, M.V.; Schreiber. V.; Lavrik, O.I. Interaction of PARP-2 with DNA structures mimicking DNA repair intermediates and consequences on activity of base excision repair proteins. Biochimie. 2013, 95, 1208-1215. [CrossRef]

- Vasil’eva, I.; Moor, N.; Anarbaev, R.; Kutuzov, M.; Lavrik, O. Functional roles of PARP2 in assembling protein–protein complexes involved in base excision DNA repair. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4679. [CrossRef]

- Kurgina, T.A.; Moor, N.A.; Kutuzov, M.M.; Lavrik, O.I. The HPF1-dependent histone PARylation catalyzed by PARP2 is specifically stimulated by an incised AP site-containing BER DNA intermediate. DNA Repair (Amst). 2022, 120, 103423. [CrossRef]

- Kurgina, T.A.; Lavrik, O.I. Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerases 1 and 2: Classical Functions and Interaction with New Histone Poly(ADP-Ribosyl)ation Factor HPF1. 2023, Mol. Biol. (Mosk), 57, 254−268. PMID: 37000654. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, J.L.; Dianov, G.L. Co-ordination of base excision repair and genome stability. DNA Repair (Amst.). 2013, 12, 326−333. [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, M.J., Parsons, J.L. Regulation of base excision repair proteins by ubiquitylation. Exp. Cell. Res. 2014, 329, 132−138. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).