Introduction

The human fetus has the capability to initiate an inflammatory response in the presence of microbial intrusion from bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa, as well as non-infection related stimuli (1). Fetal Inflammatory Response Syndrome (FIRS) is a condition occurring during the fetal period, characterized by the activation of the fetal immune system, which denotes a subclinical state. FIRS can be viewed as a specific manifestation of the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) during the fetal stage. Gomez et al. (2) introduced the concept of FIRS, which is rooted in SIRS. FIRS diagnosis relies on an Interleukin-6 (IL-6) level exceeding 11 pg/mL in fetal cord blood. Additionally, Pacora et al. (3) in 2002 proposed that histopathological indicators such as funisitis/chorionic vasculitis could validate FIRS. Infants with FIRS face elevated rates of complications, including early-onset neonatal sepsis, intraventricular hemorrhage, periventricular leukomalacia, and mortality, compared to those without FIRS (4-7). Diagnosing FIRS is vital because it allows for the early identification of at-risk newborns, enabling healthcare providers to take the necessary steps to optimize care and reduce the likelihood of severe complications and mortality.

Innate immunity is the first line of defense against infection and comprises physical and chemical barriers, such as the skin enzymes and proteins. In innate immunity, the first line of defense is provided by cellular and humoral mediators. PTX3 (Pentraxin 3), a biomarker involved in innate immunity, is stored in neutrophils (8). Although there is no direct information linking PTX3 and innate immunity in newborn babies (9). It is known that the immune system of neonates and infants is still developing and has different components of innate and acquired immunity (10).

PTX3 is a well-known acute phase protein. Research has shown that it is synthesized by numerous cell types within the body during inflammation and is also locally produced at the site of inflammation (10). Normally, PTX3 is stored in neutrophil granules where there is a constant pool of glycoproteins. Studies indicate that levels of PTX3 in the blood serum start to rise as early as 1 hour after damage to the body. It is also important to note that this protein is synthesized and acts locally during inflammation.

Under physiological conditions, except for the pre-ovulation period and pregnancy, plasma PTX3 levels are very low. For instance, 2 ng/mL in humans and 25 ng/mL in mice (11). However, in inflammatory or infectious diseases, PTX3 acts as an acute-phase protein, with very low levels in the serum and tissues of normal individuals, rapidly increasing in response to inflammatory stimuli. There is evidence that PTX3 is associated with inflammation in the early stages. In light of these findings, it can be argued that PTX3 can be used as a marker of the acute phase response.

Research studies conducted in adult patients have demonstrated the prognostic significance of PTX3 in critically ill intensive care patients with sepsis and bacteremia (12). PTX3, an acute-phase protein closely linked to innate immunity, has emerged as a valuable marker for detecting the onset of inflammation. In this study, we postulate that PTX3 holds both diagnostic and prognostic value in preterm newborns.

The primary objective of our research is to investigate the relationship between cord blood PTX3 levels and FIRS in preterm newborns, taking into account the rapid increase in PTX3 levels in response to inflammatory stimuli. By assessing PTX3 in these cord blood samples, we aim to explore its potential as a biomarker for these medical conditions. The findings of this study have the potential to facilitate early diagnosis and enhance the effective management of FIRS in preterm newborns, ultimately leading to improved long-term prognosis.

Materials-Methods

This prospective study was conducted in the Department of Neonatology, Faculty of Eskişehir Osmangazi University Medical Faculty, in the period between September 2008, March 2009.

Study Popülation: A total of 63 patients with gestational age between 28-36 weeks, who were followed up in the neonatal intensive care unit of Eskişehir Osmangazi University Faculty of Medicine. One patient was excluded from the study due to congenital anomalies. Upon enrollment, data were collected on subject demographics, clinical history, and relevant comorbidities, with a particular focus on morbidity rates in premature infants.

Based on clinical manifestations (poor suckling, lethargy, altered muscle tone, respiratory distress, apnea, poor perfusion, cyanosis, bradycardia, thermoregulatory disorders including fever or hypothermia, food intolerance, and metabolic acidosis) and laboratory test results (CRP, TNF-Alfa, IL-6, PTX 3, platelet count, and white blood cell (WBC) count), the infection was determined in neonates. Moreover, we performed CRP, TNF-alfa, IL-6, PTX3 in mother blood. For this study, we gathered 2 mL samples of maternal venous blood collected immediately after delivery and 1 mL samples of umbilical vein blood during delivery from the neonates. Additionally, blood samples (0.5 mL) from newborns were collected from the peripheral vessels during a routine blood sampling procedure in the first 12 hours of life and 3rd day for cytokines. In all systemic blood samples, the levels of PTX3, CRP, and IL-6 as well as platelet and white blood cell (WBC) count were determined. In addition, PTX3, IL-6, and TNF alpha concentrations were measured in both umbilical cord blood and peripheral blood on the third day after birth. After separation, the obtained serum samples were stored at -80°C until all samples were collected.

Diagnosis of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) was made based on the clinical signs of premature infants, such as cyanosis, respiratory distress, groaning respiration, intercostal and subcostal retractions, and radiological findings of reticulogranular appearance, air bronchogram, and lack of ventilation. Diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) was based on the continuation of oxygen demand until the 36th week according to the corrected age calculation for infants younger than 32 weeks of gestation, and for infants older than 32 weeks of gestation, a postnatal oxygen requirement of more than 28 days, according to the clinic. IL-6 levels above 11 pg/mL detected in the umbilical vein were considered as FIRS (+). Patients were divided into FIRS (+) and FIRS (-) groups depending on the presence of fetal inflammatory response syndrome.

Sample acquisition

In 62 infants, the umbilical cord during delivery and 3rd. periferik blood samples were collected for TNF-α, IL-6, and PTX 3 levels. Serum and plasma were separated by centrifugation at 5000 cycles for 10 min without blood clotting and taken into biochemistry and CBC tubes for cytokine and PTX 3 analysis. The separated serum and plasma were transferred to other tubes and stored at -80º C until the day of the study.

Cytokine levels and PTX 3 measurements

TNF-α, IL-6, and PTX 3 levels were studied using the Alfa Prime ELISA instrument by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). "Bender Medsystems TNf-α" Elisa kit was used for TNF-α measurements, "BenderMedSystems- Human IL-6" Elisa kit was used for IL-6 measurements, and "Quantakine- Human Pentraxin 3/ TSG-14 Immunoassay" Elisa kit was used for PTX 3 levels. The units of TNF-α and IL-6 were measured as pg/ml, and the unit of PTX was 3 ng/ml.

Statistical Method

The data were evaluated using IBM SPSS Statistics Standard Concurrent User V 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA) statistical package program. Descriptive statistics are given as number of units (n), percentage (%), mean ± standard deviation, median (M), minimum (min), maximum (max), and interquartile range (IQR) values. The normal distribution of the numerical variables was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk normality test. The homogeneity of variance was evaluated using Levene’s test. Comparisons for FIRS groups in numerical variables were made by t-test in independent samples if the data were normally distributed and by Mann-Whitney U test if the data were not normally distributed. Chi-square tests were used to compare groups on categorical variables. Factors affecting FIRS positivity were evaluated using a multiple binary logistic regression analysis. The Backward Wald method was used as the elimination method. The goodness of fit for the latest model was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. The performance of PTX-3 in predicting OPPORTUNITY positivity was evaluated using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

The study was approved by the appropriate Bioethics Committee (no. Eskişehir Osmangazi University, Faculty of Medicine, 2008/ 442). All parents provided a signed informed consent before recruitment into the research.

Results

Sixty-three patients were enrolled in the study. One patient was excluded due to multiple congenital anomalies. The study was completed with 62 patients. Of these, 35 (56.5%) were female. The median gestational age was 33 weeks and the median birth weight was 1795 g. Early membrane rupture was present in 41 (66.1%) patients and 18 (29%) patients were diagnosed with respiratory distress syndrome (RDS). Six (8.2%) patients received a diagnosis of neonatal pneumonia. The placentas of 49 patients could be examined. Funisitis was found in 22 (44.9%) of these patients (

Table 1).

The parameters analyzed from cord blood and peripheral blood samples of patients are shown in

Table 2. The median serum reactive protein (CRP) on the first day was 0.22 (0.01-12.8), TNF alpha 0.28 pg/mL, IL-6 6.59 pg/mL, and PTX3 4.59 (0.95-36.7) ng/mL. (

Table 2).

The median values of PTX 3 were found to be 7.67 ng/mL in preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (PPROM), 13.7 ng/mL in RDS, 14.47 ng/mL in sepsis, 16.45 ng/mL in neonatal pneumonia, 6.49 ng/mL in cases with funisitis, 11.51 ng/mL in those with FIRS, 31.8 ng/mL in cases with exitus, 2.78 ng/mL in infants diagnosed with ROP, 29 ng/mL in infants with intracranial hemorrhage, and 9.52 ng/mL in those with BPD (

Table 3).

In cord and peripheral blood samples, we found significantly elevated levels of PTX3 in patients with RDS (p=0.022), sepsis (p=0.001), neonatal pneumonia (p=0.016), and FIRS (p=0.001) (

Table 3). The median PTX3 level in patients with an exitus was 16.28 ng/mL. Furthermore, although the relationship between CRP (p=0.10) and IL-6 levels on the 3rd day (p=0.09) in FIRS(+) cases was not significant, the correlation with cord IL-6 (p=0.001) was statistically significant. In infants with FIRS, the increase in PTX3 was statistically significant (p=0.013), with an OR of 1.131 (95% CI 1.026-1.246) (

Table 4).

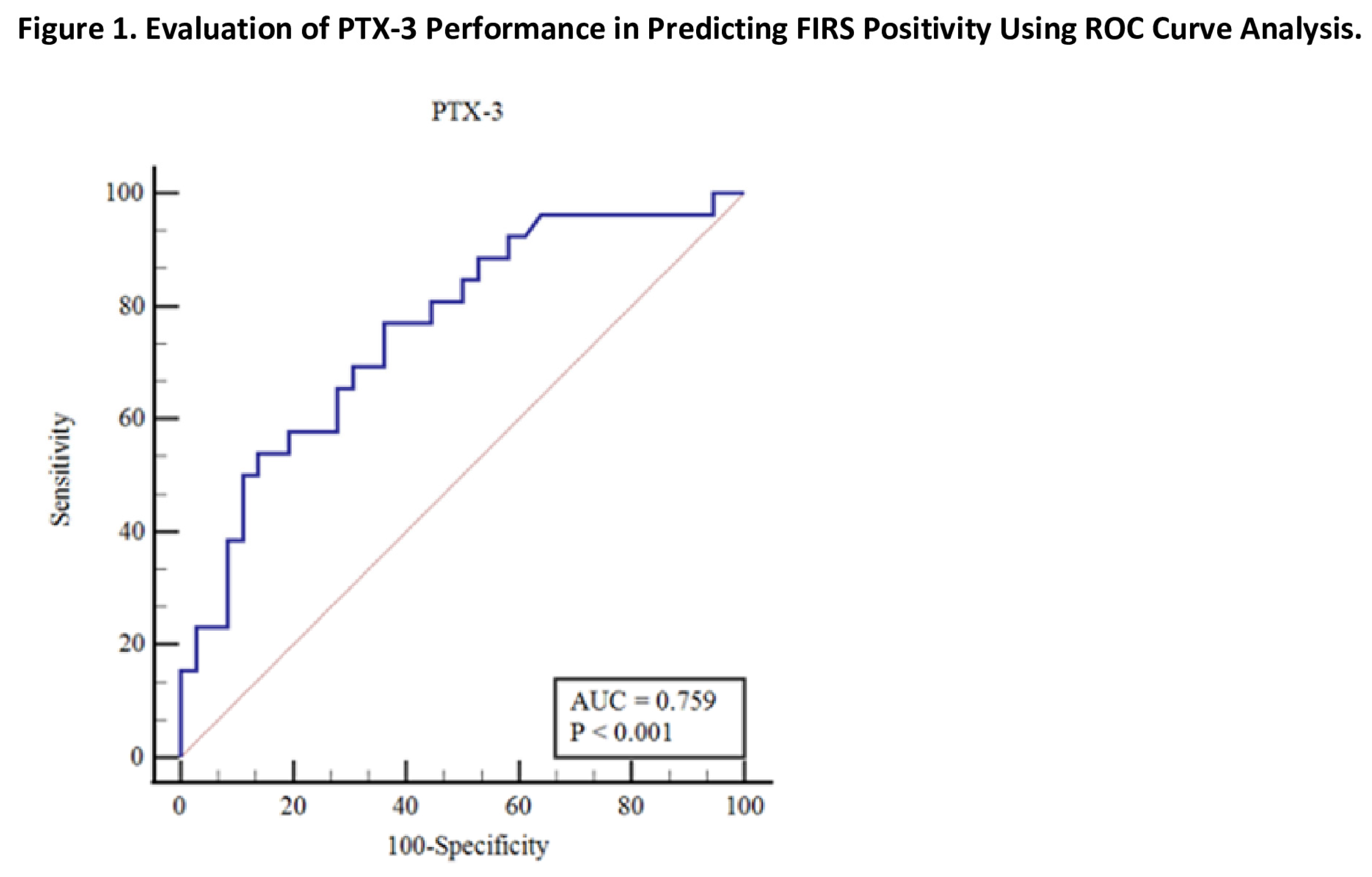

The PTX3 level had a cutoff value >4.45 (p<0.001) for predicting FIRS with an AUC of 0.759, 76.9% sensitivity (95% CI 56.4-91), and 63.9% specificity (95% CI 46.2-79.2) (

Table 5).

When comparing the serum cytokine levels of mothers and infants, there was no significant difference for IL-6 (p=0.184). However, there was a significant difference for PTX (p=0.001) and TNF-alpha (p=0.001) (

Table 6).

Discussion

In this study, we observed significant associations between levels of PTX3 and several clinical conditions, including RDS, sepsis, neonatal pneumonia, and surfactant usage. These findings strongly suggest that PTX3 shows promise as a useful biomarker for assessing the severity of pulmonary injury and fetal inflammation in newborns. Furthermore, our results revealed notable disparities in PTX3 levels between infants with FIRS and those without FIRS, underscoring the potential role of PTX3 in identifying instances of this condition. Significant correlations were found between increased PTX3 concentration and RDS, sepsis, pneumonia and surfactant therapy required for lung maturation support. These associations indicate PTX3 may serve as a valuable metric for evaluating the extent of lung damage and prenatal inflammatory response in newborns.

Plasma levels of PTX3 rise in certain medical conditions like sepsis, small-vessel vasculitis, and acute myocardial infarction (13-15). PTX3 is a multifunctional acute phase protein that belongs to the family of long pentraxins. It is synthesized in various cells throughout the body in response to proinflammatory factors and is also produced locally at the site of inflammation. In normal physiological conditions, PTX3 is stored in neutrophil granules, along with other glycoproteins. Following a damaging stimulus, an increase in PTX3 levels in the bloodstream can be observed as early as one hour (9). While the precise biological functions of PTX3 in children remain incompletely understood, certain studies have indicated that PTX3 exhibits a more sensitive and rapid elevation compared to CRP in response to inflammation, specifically within a short duration of one hour (16-19). These findings suggest the potential utility of PTX3 as a biomarker in pediatric populations.

The reference range for PTX3 levels in newborn infants is currently unknown. However, a study by Galli et al. demonstrated that PTX3 levels differed between cesarean section (C/S) and vaginal deliveries (C/S: 13.24 ng/mL, vaginal: 18.41 ng/mL), indicating an association between PTX3 levels and the mode of delivery. In another study involving premature infants born to mothers with electronic medical records (EMRs) between 23-36 weeks of gestation, higher PTX3 levels were found to be linked to intracranial hemorrhage, increased mortality risk, and prolonged neonatal intensive care unit stays. Furthermore, elevated PTX3 levels were observed in newborns with respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), sepsis, prematurity-associated retinopathy, and necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) (20-21). PTX3 has been shown to increase the oxygen and ventilation requirements in late preterm infants (22).

In this study, the median PTX3 level of preterm infants between 28-37 weeks gestation was found to be 4.59 (0.95-36.77) ng/mL. Infants born to mothers with PPROM had a PTX3 level of 7.67 ng/mL. Those diagnosed with RDS had a PTX3 level of 13.7 ng/mL, while infants with sepsis had a PTX3 level of 14.47 ng/mL. Infants with neonatal pneumonia had a PTX3 level of 16.45 ng/mL, while those with funisitis had a PTX3 level of 6.49 ng/mL. Infants with FIRS had a PTX3 level of 11.51 ng/mL, and those who did not survive (exitus) had a PTX3 level of 31.8 ng/mL. Infants with retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) had a PTX3 level of 2.78 ng/mL, and those with intracranial hemorrhage had a PTX3 level of 29 ng/mL.

The study by Battal et al. demonstrated that PTX3 may be a more reliable diagnostic marker for pulmonary hypertension and sepsis in full-term neonates compared to CRP and procalcitonin (16-17). Furthermore, this study found a significant association between elevated PTX3 levels and sepsis in infants with clinical signs of infection, as well as in infants with RDS. These findings suggest that PTX3 could serve as an early diagnostic marker for respiratory conditions, such as RDS, in preterm infants.

Type II pneumocytes play a crucial role in surfactant production and function. It is known that the functions of surfactant-producing type II pneumocytes are impaired in RDS. In adult patients with COVID-19, PTX3 positivity has been observed in alveolar macrophages and Type II pneumocytes. Additionally, it has been shown that both peripheral blood and lungs of these patients contain high levels of PTX3 in myelomonocytic cells (23). This study also found elevated PTX3 levels in patients with RDS and neonatal pneumonia. Surfactant has been administered to all patients diagnosed with RDS, as well as to some infants with a diagnosis of neonatal pneumonia.

When the fetus is exposed to microorganisms or non-infection-related stimuli, it can elicit a local or systemic inflammatory response. The term "Fetal Inflammatory Response Syndrome" (FIRS) is commonly used to describe the presence of a systemic inflammatory response resulting from the activation of the innate immune response. Early identification of infants with FIRS is crucial. In this study, the levels of PTX3 in both umbilical cord and peripheral blood samples were found to be potentially significant indicators for early detection of FIRS. Infants born with FIRS have a higher risk of various complications compared to those without FIRS, both in the early and late stages. Early complications include a higher incidence of neonatal sepsis, intraventricular hemorrhage, periventricular leukomalacia, and death. Surviving infants are at risk of long-term sequelae such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia, cerebral palsy, retinopathy of prematurity, and sensorineural hearing loss (1).

In this study, we demonstrated the significant increase in PTX3 levels in patients who developed FIRS. Additionally, we found that a cutoff value of >4.45 ng/mL for PTX3 had a sensitivity of 76.9% and specificity of 63.9% in predicting FIRS. Among the patients in the study group, four of them experienced fatal outcomes. The median PTX3 value for those who had fatal outcomes was 16.28 ng/mL.

The lack of correlation between maternal and neonatal PTX3 concentrations in the study conducted by Akin et al. contrasts with the findings of this study, which revealed a correlation between maternal and neonatal PTX3 levels as well as TNF alpha levels. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in sample characteristics, such as low Apgar scores and all mothers having preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), which were present exclusively in this study's sample. These variations in sample characteristics could contribute to the observed differences in the results.

The main limitations of this study were the small sample size, limited occurrence of complications, and the relatively short duration of the study (seven months). The lack of statistical significance in the association between PTX3 levels and the development of complications may be attributed to these factors. It is important to note these limitations and highlight the need for larger-scale and longer-term studies to validate these findings. The limitations of this study should be considered when interpreting the results and making generalizations.

The strengths of this study include the significant correlations observed between PTX3 levels and important clinical conditions such as RDS, sepsis, neonatal pneumonia, and surfactant use. These findings demonstrate the promising potential of PTX3 as a useful biomarker for assessing the severity of pulmonary damage and fetal inflammation in newborns. Furthermore, our results have revealed notable differences in PTX3 levels between infants with and without FIRS, highlighting the potential role of PTX3 in the identification of this condition. Significant correlations have been found between PTX3 levels and conditions requiring surfactant therapy, such as RDS, sepsis, pneumonia, and lung maturation support. These relationships indicate that PTX3 could be a valuable criterion for assessing the degree of lung damage and prenatal inflammatory response.

Additionally, although the precise biological functions of PTX3 in children have not been fully understood, some studies have shown that PTX3 responds to inflammation more sensitively and rapidly than C-reactive protein (CRP), with a significant increase observed within a short period of one hour. These findings suggest the potential usefulness of PTX3 as a biomarker in pediatric populations.

In conclusion, the study demonstrates significant associations between PTX3 levels and important clinical conditions, indicating its potential as a useful biomarker for assessing pulmonary damage severity, fetal inflammation, and identifying FIRS in newborns. The correlations between PTX3 levels and conditions such as RDS, sepsis, pneumonia, and the need for surfactant therapy highlight its potential as a valuable measure for evaluating lung damage and prenatal inflammatory response. Further research is warranted to fully elucidate the precise biological functions of PTX3 in children and explore its potential applications as a biomarker in pediatric populations.

Author Contribution

Conceptualization: EÇD, BÖG, AA, Methodology: EÇD, BÖG, HNT, Software: BÖG, EÇD, Validation: BÖG, ÖÇ, Formal Analysis: ÖÇ, Investigation: BÖG, Resorces: BÖG, HNT, AA, Data Curation: BÖG, EÇD, Writing-original Draft Preparation: BÖG, Writing –Review&Editing: EÇD, HNT, AA, Vizualization: BÖG, Supervision: AA, EÇD, HNT, Project Administration: AA, EÇD, Funding Acquisition: EÇD.

Acknowledgements

This study was presented as an oral presentation at the 19th UNEKO (National Neonatology Congress in Türkiye) and this article is also derived from the thesis titled "Evaluation of inflammation parameters and PTX 3 in umbilical cord blood in preterm". We would like to thank the participants and their families for their involvement in this study.

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- E Jung, R Romero, L Yeo et all. The fetal inflammatory response syndrome: the origins of a concept, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and obstetrical implications. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020:25;p 101146. [CrossRef]

- Gomez R, Romero R, Ghezzi F et all. The fetal inflammatory response syndrome Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179: 194–202. [CrossRef]

- Pacora P, Chaiworapongsa T, Maymon E et all. Funisitis and chorionic vasculitis: the histological counterpart of the fetal inflammatory response syndrome J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002; 11; 18–25. [CrossRef]

- Lannergård A, Rosenström F, Normann E et all. Serum pentraxin 3 concentrations in neonates Upsala J Med Sci.2014; 119: 62–4. [CrossRef]

- Yu J C, Khodadadi H, Malik A et all. Innate immunity of neonates and infants Front Immunol.2018;9: 1759. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal A., Singh PP, Bottazzi B et all. Pattern Recognition by Pentraxins. 2009. Target Pattern Recognition in Innate Immunity. Adv Exp Med Biol. vol 653. Springer, New York, NY. [CrossRef]

- Mantovani A, Garlanda C, Doni A et al.: Pentraxins in innate immunity: from C-reactive protein to the long pentraxin PTX3. J Clin Immunol 2008; 28: 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Giacomini A, Ghedini GC, Presta M et al.: Long pentraxin 3: a novel multifaceted player in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2018; 1869: 53–63. [CrossRef]

- Szymkowiak M, Surmiak P, Baumert M. Pentraxin 3 – possible uses in neonatology and paediatrics. Paediatr Fam Med. 2020:16(3);247–250. [CrossRef]

- Maugeri N, Rovere-Querini P, Slavich M et al.: Early and transient release of leukocyte pentraxin 3 during acute myocardial infarction. J Immunol 2011; 187: 970–979. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Jafari N, Barnes RB et al.: Studies of gene expression in human cumulus cells indicate pentraxin 3 as a possible marker for oocyte quality. Fertil Steril 2005; 83 Suppl 1: 1169–1179. [CrossRef]

- Cruciani L, Romero R, Vaisbuch E et al.: Pentraxin 3 in maternal circulation: an association with preterm labor and preterm PROM, but not with intra-amniotic infection/inflammation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2010; 23: 1097–1105. [CrossRef]

- Mauri T, Bellani G, Patroniti N, et al. Persisting high concentra tions of plasma pentraxin 3 over the first days after severe sepsis and septic shock onset are associated with mortality. Intensive Care Med 2010;36:621–9. [CrossRef]

- Mantovani A, Garlanda C, Bottazzi B, et al. The long pentraxin PTX3 in vascular pathology. Vascul Pharmacol 2006;45:326–30. [CrossRef]

- Nebuloni M, Pasqualini F, Zerbi P, et al. PTX3 expression in the heart tissues of patients with myocardial infarction and infectious myocarditis. Cardiovasc Pathol 2011;20:e27–35. [CrossRef]

- Farhadi R, Rafiei A, Hamdamian S et al.: Pentraxin 3 in neonates with and without diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. Clin Biochem 2017; 50: 223–227. [CrossRef]

- Battal F, Emel Bulut Ö, Yıldırım Ş et al.: Serum pentraxin 3 concen tration in neonatal sepsis. J Pediatr Infect Dis 2019; 14: 219–222. [CrossRef]

- Sprong T, Peri G, Neeleman C et al.: Pentraxin 3 and C-reactive protein in severe meningococcal disease. Shock 2009; 31: 28–32. [CrossRef]

- Yüksel S, Çağlar M, Evrengül H et al.: Could serum pentraxin 3 levels and IgM deposition in skin biopsies predict subsequent renal involvement in children with Henoch–Schönlein purpura? Pediatr Nephrol 2015; 30: 969–974. [CrossRef]

- Galli A, Nuccetelli M, Pierini R et al.: PTX3 protein determination in neonatal and in childhood age. Early Hum Dev 2008; 84.Suppl: S144. [CrossRef]

- Akin MA, Gunes T, Coban D et al.: Pentraxin 3 concentrations of the mothers with preterm premature rupture of membranes and their neonates, and early neonatal outcome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2015; 28: 1170–1175. [CrossRef]

- Sciacca P, Betta P, Mattia C et al.: Pentraxin-3 in late-preterm newborns with hypoxic respiratory failure. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2010; 2: 805–809). [CrossRef]

- Brunetta E., Folci M, Bottazzi B et al. Macrophage expression and prognostic significance of the long pentraxin PTX3 in COVID-19. Nat Immunol. 2021;22, 19–24. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Patients.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Patients.

| Variables |

n |

Statistics |

|

Gender, n (%) |

|

|

| Girls |

62 |

35 (56.5) |

| Boys |

27 (43.5) |

| Gestational age, M (min-max) |

62 |

33 (28-37) |

| Birth weight, M (min-max) |

62 |

1795 (990-3020) |

| PPROM |

62 |

|

No

Yes

|

41 (66.1) |

| |

21 (32,9) |

| RDS, n (%) |

62 |

|

| Yes |

18 (29.0) |

| No |

44 (71.0) |

| Surfactant, n (%) |

62 |

|

| Yes |

18 (29.0) |

| Yok |

44 (71.0) |

| Neonatal pneumonia, n (%) |

62 |

|

| Yes |

6 (8.2) |

| No |

56 (91.8) |

| Placenta, n (%) |

49* |

|

| Chorioamnionitis (+) |

22 (44.9) |

| Chorioamnionitis (-) |

27 (55.1) |

| Ex (exitus), n (%) |

62 |

|

| Yes |

4 (6.5) |

| No |

58 (93.5) |

|

Sepsis, n (%) |

62 |

|

| Yes |

11 (16.4) |

| No |

51 (83.6) |

ROP (retinopathy of prematurity), n (%)

Yes

No

|

62 |

3 (4.8)

59 (95.2) |

Intracranial Hemorrhage, n (%)

Yes

No |

62 |

6 (9.7)

56 (90.3) |

| BPD (Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia), n (%) |

|

|

| Yes |

62 |

4 (6.5) |

| No |

58 (93.5) |

Table 2.

Hastaların labaratuvar verileri yönünden değerlendirilmesi.

Table 2.

Hastaların labaratuvar verileri yönünden değerlendirilmesi.

| PH(cord) |

62 |

7.28±0.09 |

| PO2(mm/Hg) |

62 |

29 (11-149) |

| PCO2(mm/Hg) |

62 |

45 (10-171) |

| HCO3(mEq/L) |

62 |

19.03±4.10 |

| Laktat(mEq/L) |

62 |

28 (10-107) |

| BD (mmol/L)(base deficit) |

62 |

-6 (-20-21) |

|

APGAR (1st minute) |

62 |

7 (0-9) |

|

APGAR (5th minute) |

62 |

8 (1-10) |

| PH (peripheral blood samples) |

62 |

7,29±0,01 |

| PO2(mm/Hg) |

62 |

36 (12-71) |

| PCO2(mm/Hg) |

62 |

18 (8-27) |

| HCO3(mEq/L) |

62 |

18.13±3.41 |

| Laktat(mEq/L) |

62 |

27 (10-156) |

|

BD(mmol/L)

|

62 |

-12 (-15- (-4)) |

| Hemoglobin(gr/dL) |

62 |

17.25±1.62 |

| White Blood Cell Count |

62 |

8000 (3600-9900) |

| Plateret |

62 |

218.000(19.000-586.000) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST)(IU/L) |

62 |

57 (4-855) |

Alanine aminotransferase

(ALT) (IU/L)

|

62 |

11 (5-342) |

CRP, M (min-max)

Peripheral blood samples |

62 |

0,22 (0,01-12,8) |

TNF alfa, M (min-max) (pg/mL)

Cord:

Peripheral blood samples |

62 |

0.28 (0.17-7.85)

0.22(0.05-6.07) |

IL-6, M (min-max)

Pg/mL

Cord

Peripheral blood samples |

62 |

6.59(0.03-146.39)

7.07(0.92-165.53) |

PTX-3, M (min-max)

Ng/mL

Cord

Peripheral blood samples |

62 |

4.59 (0.95-36.77)

7.41(0.95-36.7) |

Table 3.

Comparison of categorical variables with PTX-3.

Table 3.

Comparison of categorical variables with PTX-3.

| |

|

PTX-3 |

Test Statistics |

| |

n |

M |

IQR |

Test value |

p value |

| Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

| Girls |

35 |

4.77 |

7.83 |

0.114†

|

0.910 |

| Boys |

27 |

4.46 |

7.50 |

|

|

| PPROM |

|

|

|

|

|

| None |

41 |

4.77 |

7.67 |

|

|

| Yes |

21 |

9,40 |

1.00 |

0.707‡

|

0.702 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| RDS(Respiratory Distress Syndrome) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

18 |

10.11 |

13.70 |

2.287†

|

0.022 |

| No |

44 |

4.30 |

2.86 |

|

|

| Sulfactant |

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

18 |

10.11 |

13.70 |

2.287†

|

0.022 |

| No |

44 |

4.30 |

2.86 |

|

|

| Sepsis |

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

11 |

10.21 |

14.47 |

1.451†

|

0.001 |

| No |

51 |

4.46 |

4.81 |

|

|

| Neonatal pneumonia |

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

5 |

12.27 |

16.45 |

2.340†

|

0.016 |

| No |

56 |

4.45 |

6.39 |

|

|

| Placenta** |

|

|

|

|

|

| Chorioamnionitis(+) |

22 |

5.01 |

6.49 |

1.045†

|

0.296 |

| Chorioamnionitis(-) |

27 |

4.04 |

7.41 |

|

|

FIRS

Fırs (+)

Fırs (-) |

26

36 |

8.87

3.75 |

11.51

3.65 |

3.459‡ |

0.001

|

| Exitus |

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

4 |

16.28 |

31.83 |

0.573†

|

0.590 |

| No |

58 |

4.59 |

7.47 |

|

|

| ROP (retinopathy of prematurity) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

3 |

2.78 |

- |

0.295†

|

0.781 |

| No |

59 |

4.64 |

7.65 |

|

|

| Intracranial hemorrhage |

|

|

| Yes |

6 |

4.13 |

29.00 |

0.071†

|

0.954 |

| No |

56 |

4.59 |

7.55 |

|

|

| BPD(Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia |

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

4 |

2.33 |

9.52 |

1.246†

|

0.222 |

| No |

58 |

4.70 |

7.66 |

|

|

Table 4.

Evaluation of factors affecting positivity of FIRS through multiple binary logistic regression analysis*.

Table 4.

Evaluation of factors affecting positivity of FIRS through multiple binary logistic regression analysis*.

| |

Regression Coefficients* |

| |

β |

standard error |

Wald Statistics |

p |

OR |

95% C.I.for OR

|

| Lower |

Upper |

| Constant |

-1.808 |

0.518 |

12.173 |

<0.001 |

0.164 |

|

|

| PTX-3 |

0.123 |

0.049 |

6.147 |

0.013 |

1.131 |

1.026 |

1.246 |

Variables entered on step 1: Gender, PROM,RDS, SEPSIS, gestational age, APGAR score, Base Excess (BE), PH2, peripheral CO2, peripheral HCO3, peripheral BE, White Blood Cell Count, Platelet Count (PLT), C-Reactive Protein (CRP), Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST), Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT).

Model Summary: Hosmer and Lemeshov Test χ2=9.945; p=0.269; Nagelkerke R2=0.315 |

Table 5.

Evaluation of PTX-3 Performance in Predicting FIRS Positivity Using ROC Curve Analysis.

Table 5.

Evaluation of PTX-3 Performance in Predicting FIRS Positivity Using ROC Curve Analysis.

| |

AUC

(%95 CI) |

p value |

Cut-off |

Sens

(%95 CI) |

Spec

(%95 CI) |

PPV

(%95 CI) |

NPV

(%95 CI) |

| PTX-3 |

0.759

(0.634-0.859) |

<0.001 |

>4.45 |

76.9

(56.4-91.0) |

63.9

(46.2-79.2) |

60.6

(48.7-71.4) |

79.3

(64.6-89.0) |

Table 6.

The Relationship Between Infant and Maternal Cytokines.

Table 6.

The Relationship Between Infant and Maternal Cytokines.

| |

Anne |

Bebek |

Test İstatistikleri |

| |

M (IQR) |

M (IQR) |

z |

t |

| İL-6 |

5,10 (16,17) |

6,59 (20,56) |

1,327 |

0,184 |

| PTX |

11,11 (13,12) |

4,59 (7,79) |

3,478 |

0,001 |

| TNF alfa |

1,07 (0,93) |

0,28 (1,30) |

3,342 |

0,001 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).