Submitted:

07 December 2023

Posted:

08 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

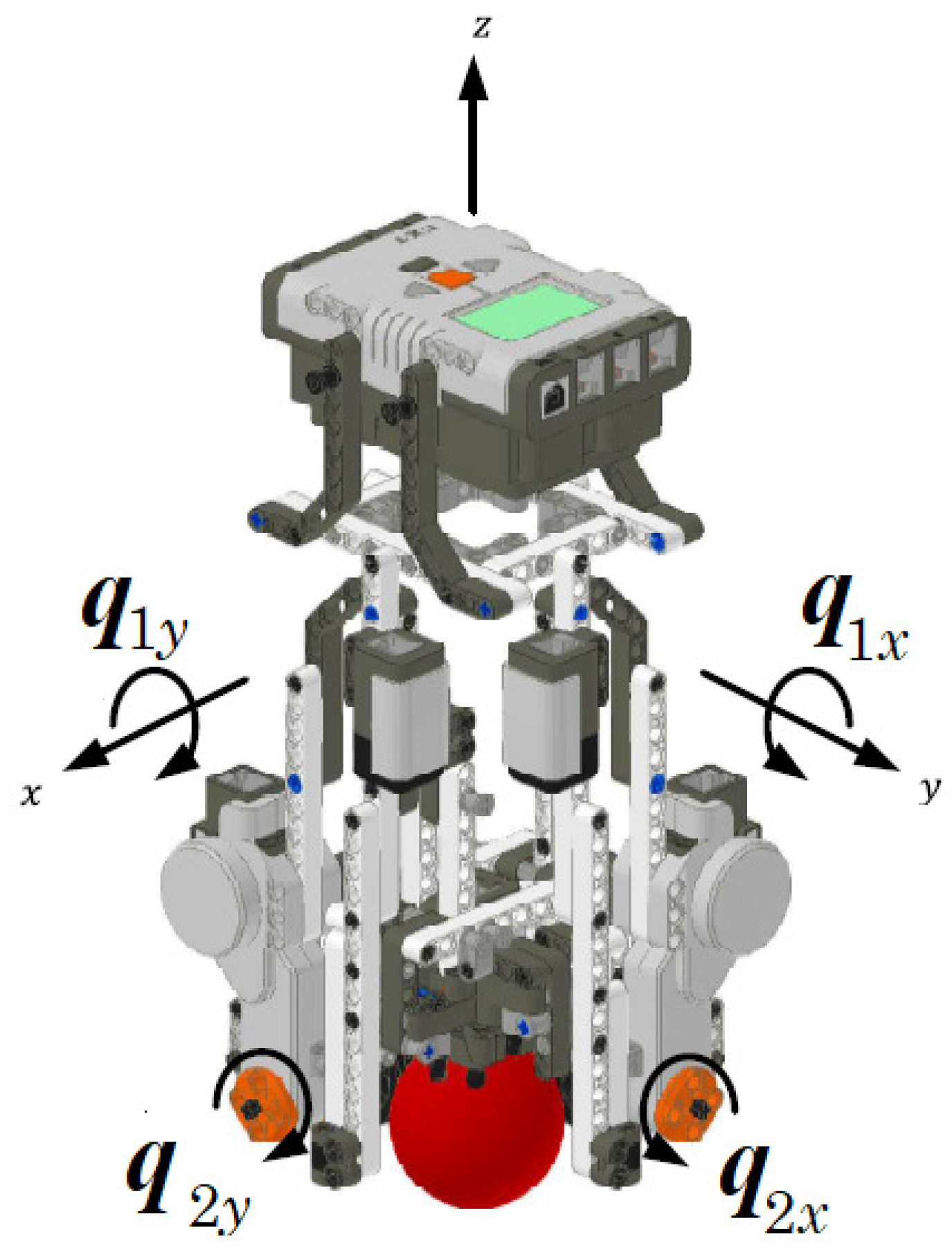

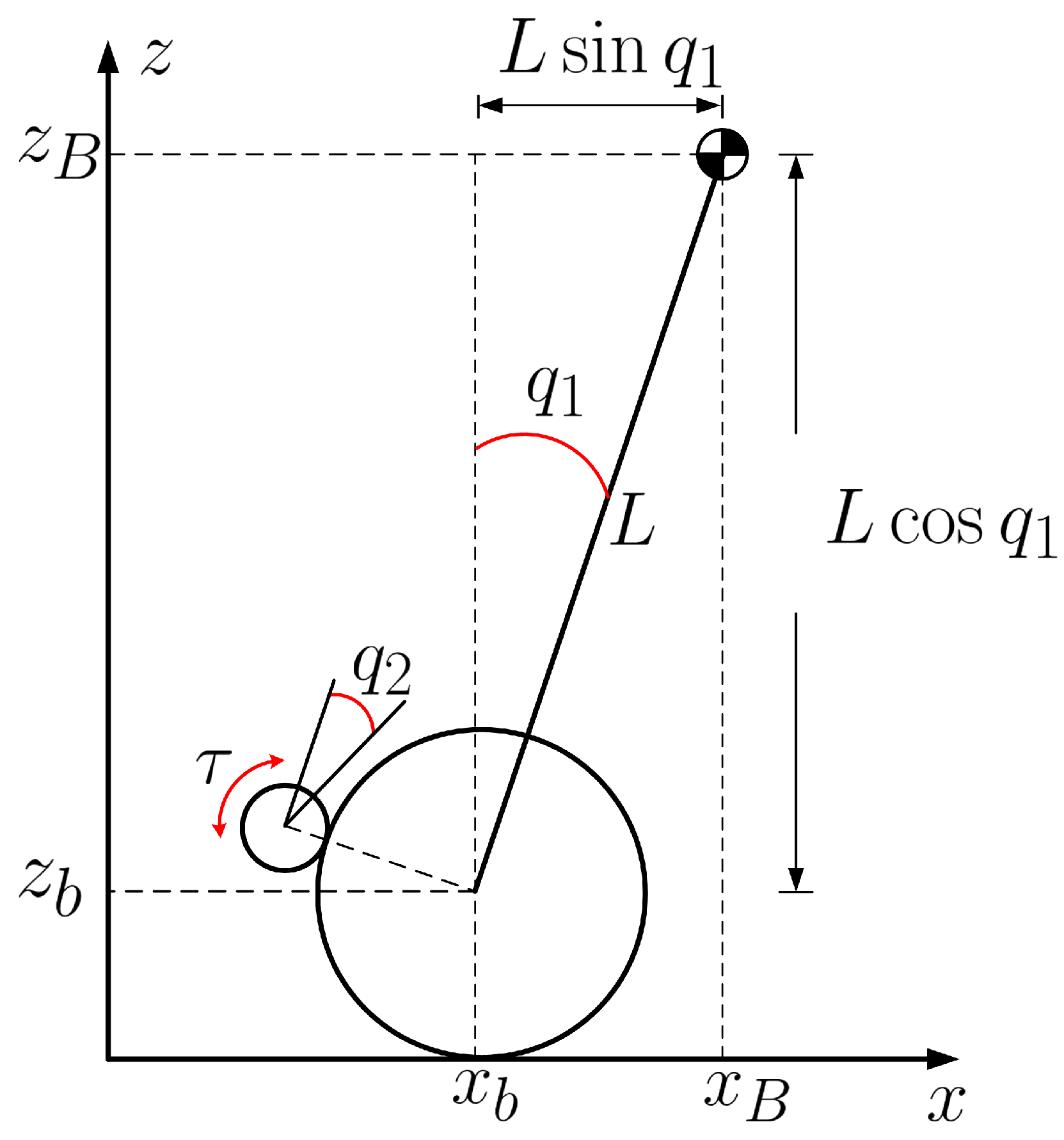

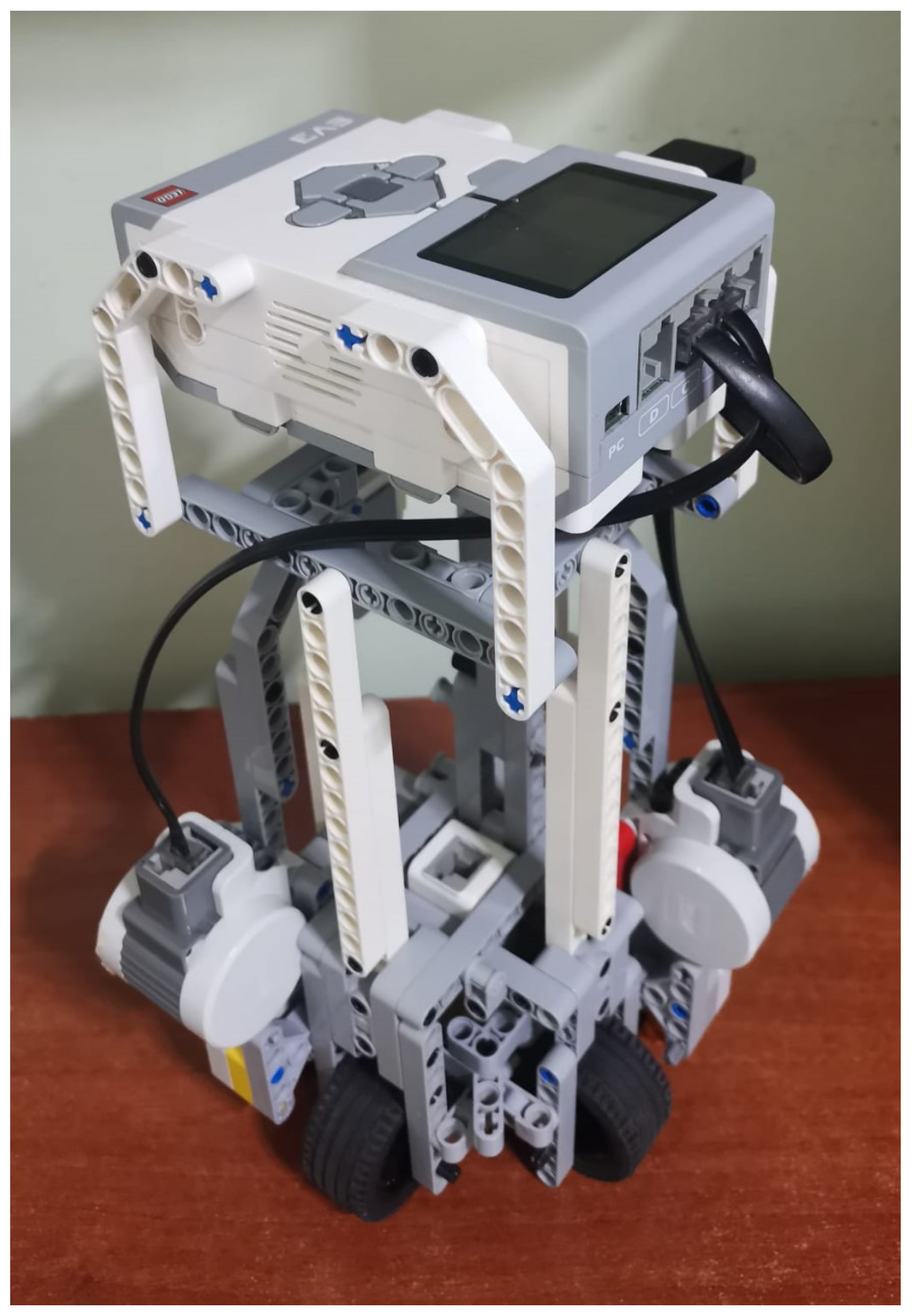

2. Dynamical model

2.1. DC motor dynamics

2.2. EV3BRS’s state–variable equations

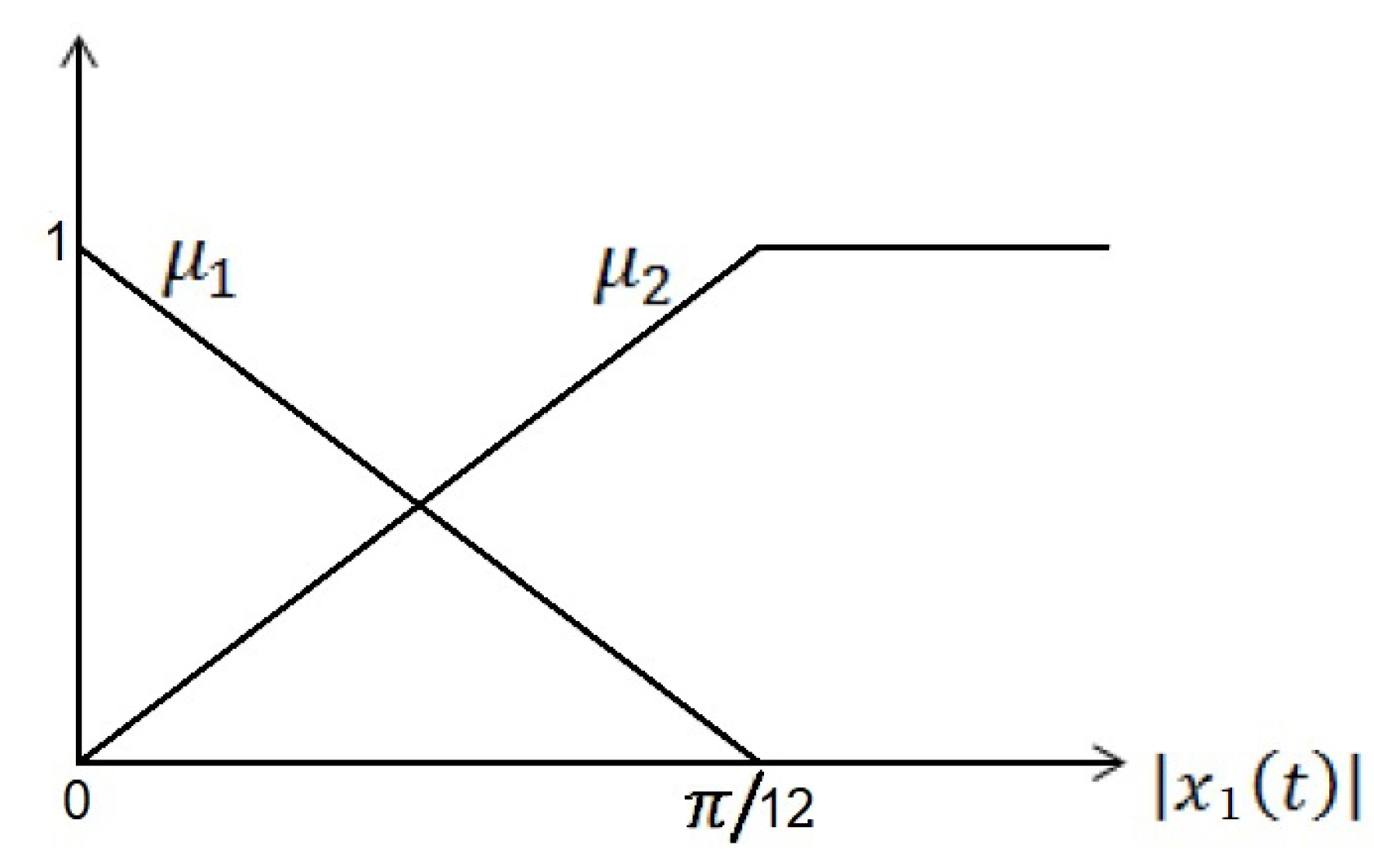

3. Takagi–Sugeno Fuzzy Modelling

3.1. EV3BRS’s TSFM

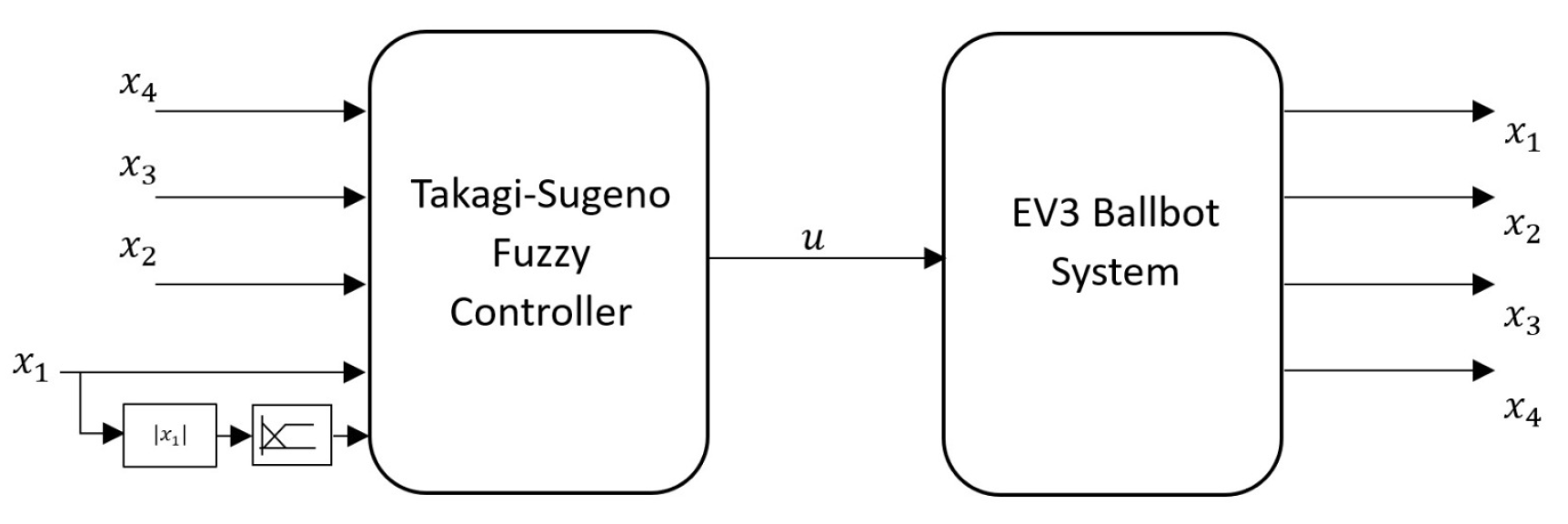

3.2. Parallel Distributed Compensation (PDC)

3.3. TSFC Design

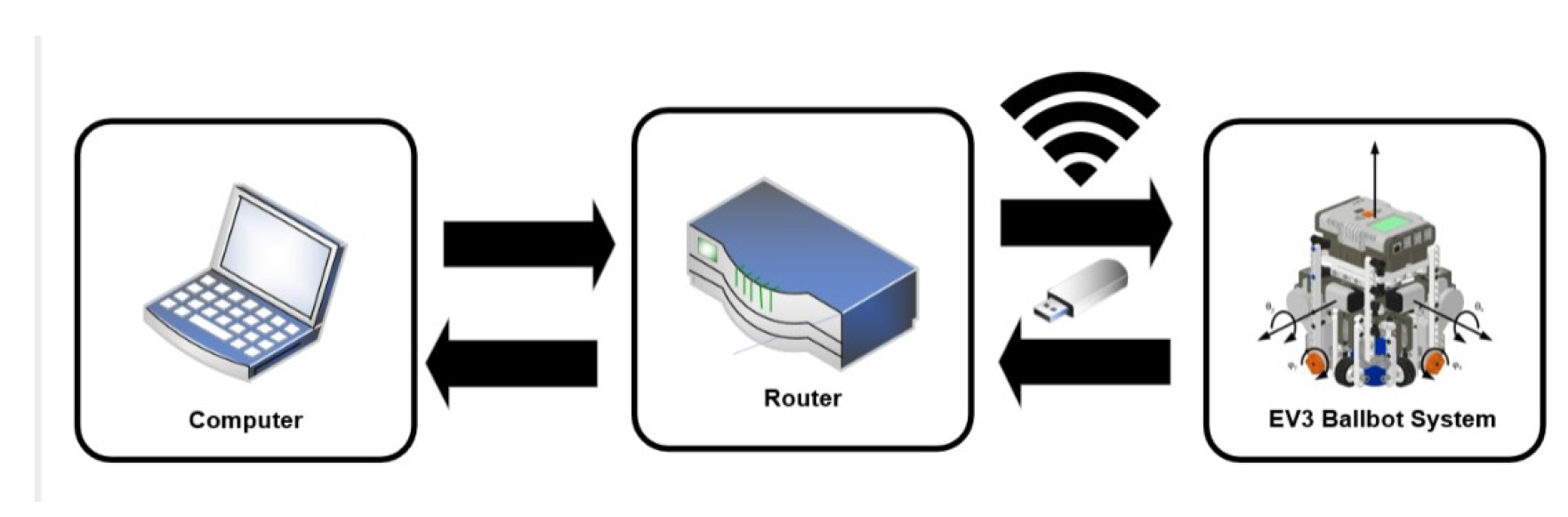

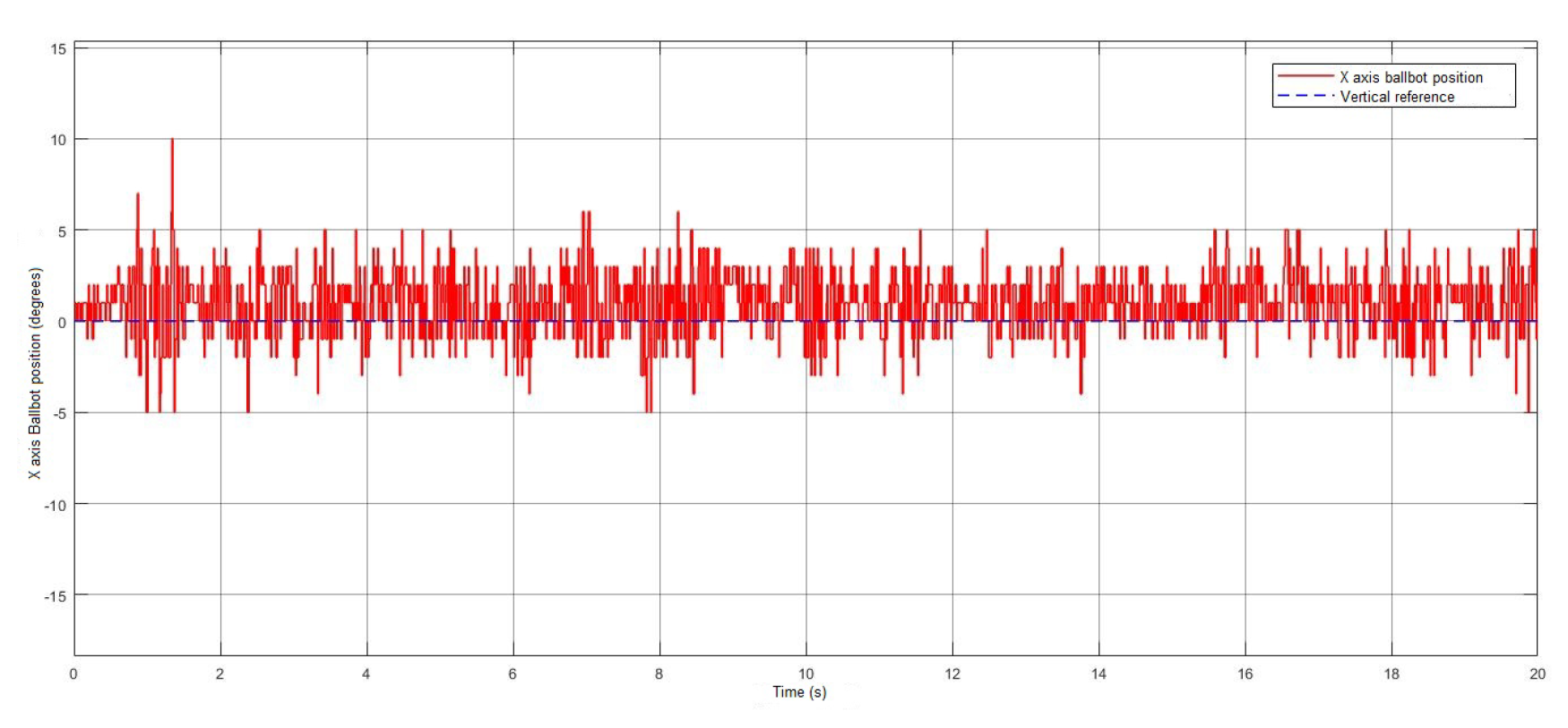

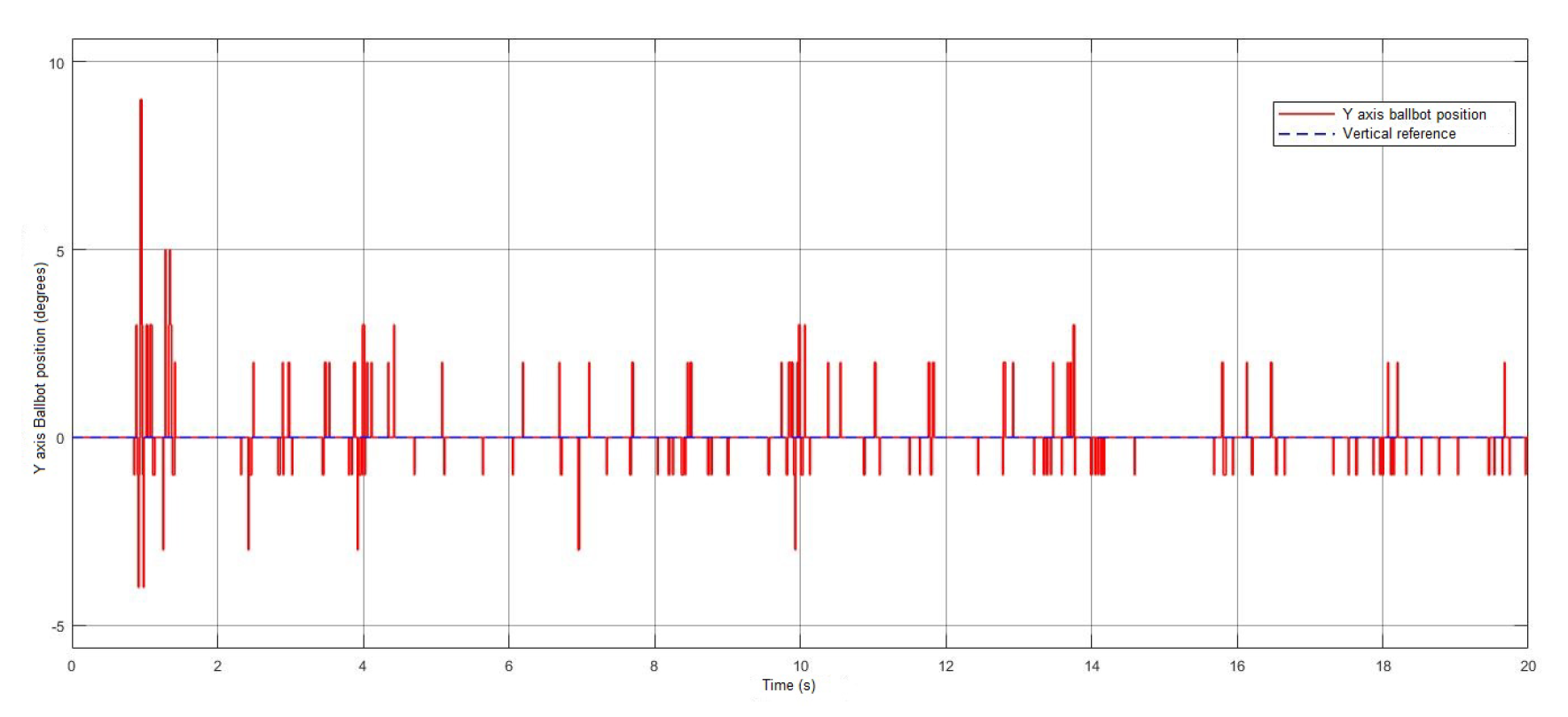

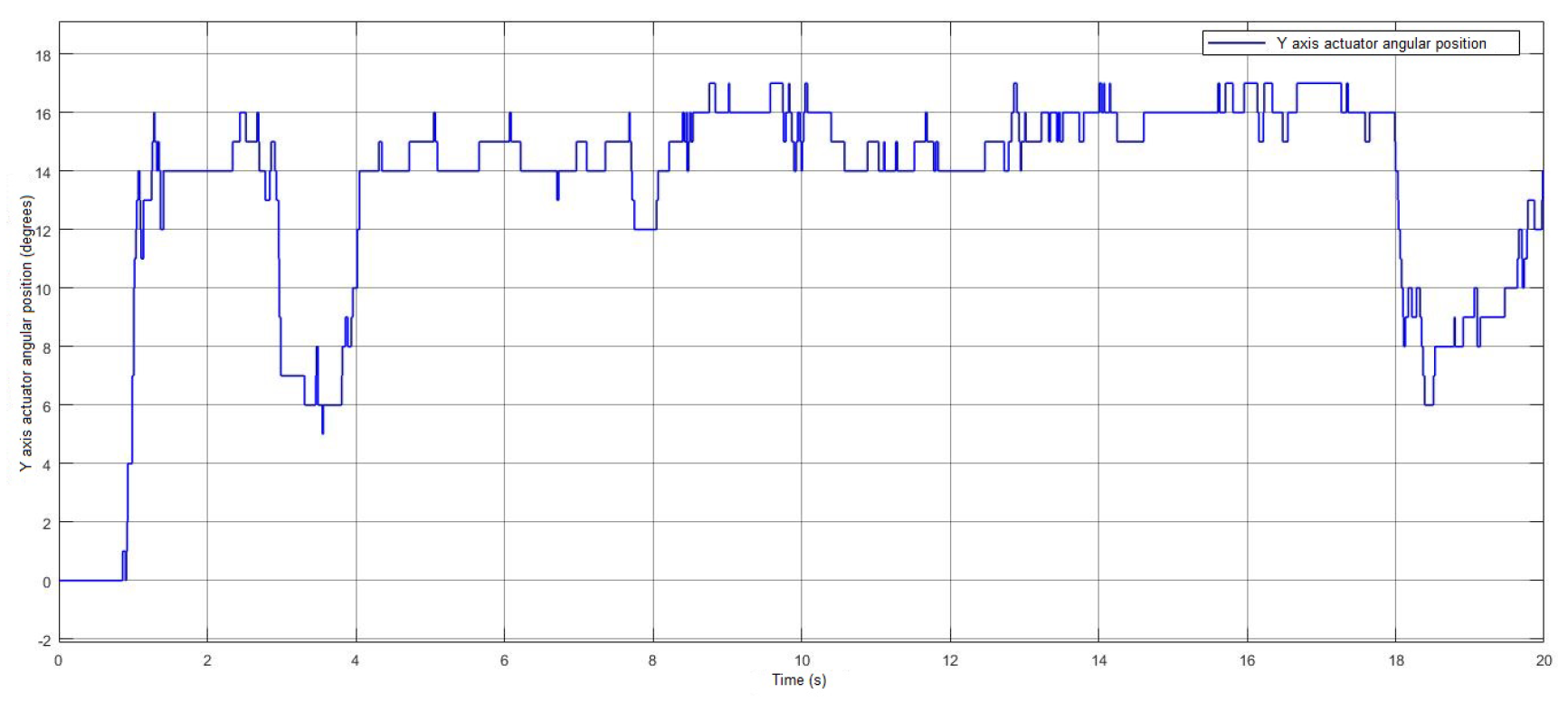

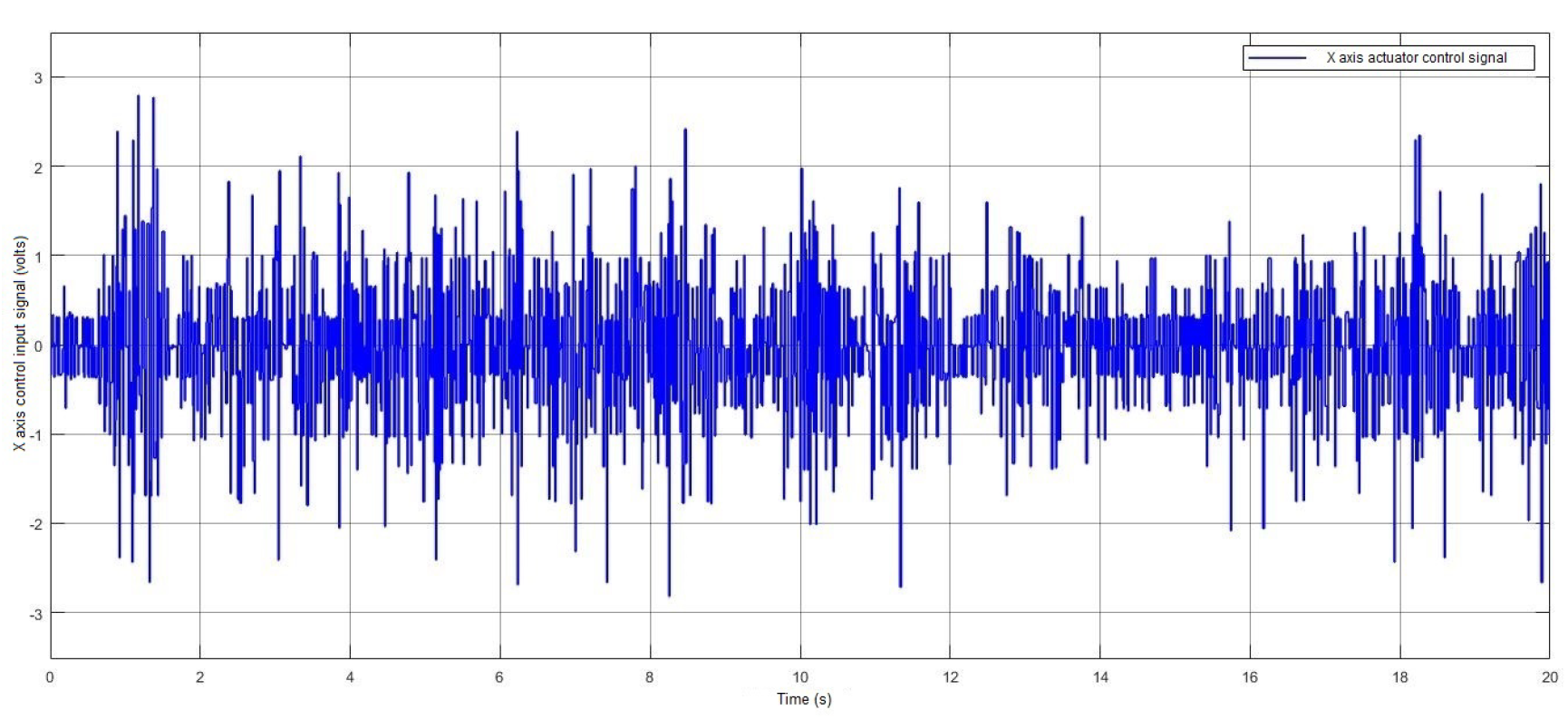

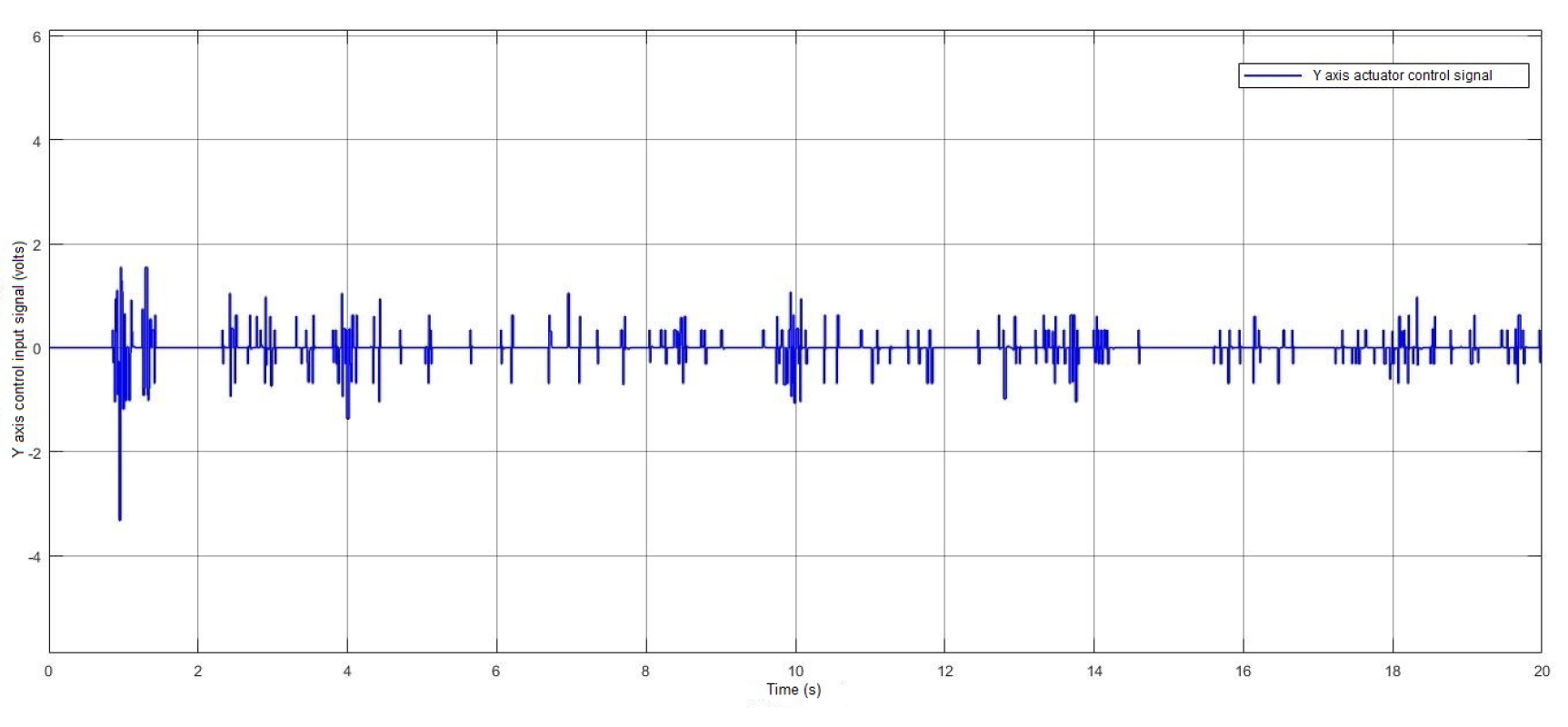

4. Results

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BEMF | Back Electromotive Force |

| BRS | Ball Robot System |

| BS | Ball Segway |

| DC | Direct Current |

| DOF | Degree-of-Freedom |

| DTLQR | Discrete-Time Linear Quadratic Regulator |

| EV3BRS | EV3 Ballbot Robotic System |

| HSMC | Hierarchical Sliding Mode Control |

| LQR | Linear Quadratic Regulator |

| LMIs | Linear Matrix Inequalities |

| MIMO | Multi-Input Multi-Output |

| NXTBRS | NXT Ballbot Robotic System |

| ODW | Omnidirectional Wheel |

| PDC | Parallel Distributed Compensation |

| PLDI | Polytopic Linear Differential Inclusion |

| PC | Polytopic Controller |

| PM | Polytopic Model |

| TSFC | Takagi-Sugeno Fuzzy Controller |

| TSFM | Takagi-Sugeno Fuzzy Model |

References

- García, R.; Arias, M. Linear Controllers for the NXT Ballbot with Parameter Variations Using Linear Matrix Inequalities. Control Syst. Mag. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- R. Hollis, Ballbots, Sci. Am., vol. 295, no. 4, 2006.

- Yamamoto, Y. NXT Ballbot Model–Based Design–Control of Self–balancing Robot on a Ball, Built with LEGO Mindstorm NXT, 1st ed., Cybernet Systems, Japan, 2009.

- Gawthrop, P.; McGookin, E. `A LEGO–based control experiment. Control Syst. Mag. 2004, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, P.; Arribas, T.; Gómez, M.; Rodríguez, O. A Monoball Robot Based on LEGO Mindstorms. Control Syst. Mag. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- P. Hurbain, LEGO 9V Technic Motors compared characteristics. [Online]. Available: http://www.philohome.com/motors/motorcomp.

- Pinto, M.; Bermúdez, G. Parameters determination of a mobil robot of LEGO Mindstorms (in Spanish). Ingeniería Investigación y Desarrollo 2007, 5, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- R. García, Development of a robot ballbot–like for control applications (in Spanish). [Online]. Available: http://jupiter.utm.mx/tesis_dig/12495.pdf.

- Ogata, K. Modern Control Engineering. Fourth Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2002.

- Franklin, G.F.; Powell, J.D.; Emami–Naeini, A. Feedback Control of Dynamic Systems. Sixth Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2010.

- I. Ortíz, F. I. Ortíz, F. Jurado, and E.J. Ollervides-Vázquez, Discrete-Time Linear Quadratic Regulator for a NXT Ballbot System, 2022 Int. Conf. on Mechatronics, Electronics and Automotive Eng. (ICMEAE), Cuernavaca, Morelos, México, pp. 95-100, 2022.

- L.E. Herrera, R. L.E. Herrera, R. Hernández, and F. Jurado, Control and extended Kalman filter based estimation for a ballbot robotic system, XX Congreso Mexicano de Robótica (COMRob), Ensenada, Baja California, México, 2018.

- Chiu, C.H.; Peng, Y.F. Design of Takagi-Sugeno Fuzzy Control Scheme for Real World System Control. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Rigatos, M. G. Rigatos, M. Abbaszadeh, J. Pomares, A nonlinear optimal control method for the ballbot autonomous vehicle, 2020 American Control Conf., Denver, CO, USA, pp. 665-670, 2020.

- D.B. Pham, S.G. D.B. Pham, S.G. Lee, S. Back, J.J. Kim, M.K. Lee, Balancing and translation control of a ball Segway that a human can ride, 2016 16th Int. Conf. on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS), Gyeongju, Korea (South), 2016.

- Pham, D.B.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.J.; Lee, S.G. “Balancing and Transferring Control of a Ball Segway Using a Double–Loop Approach”. IEEE Control Systems Magazine 2018, 38, 15–37. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, D.B.; Lee, S.G. “Hierarchical Sliding Mode Control for a Two-Dimensional Ball Segway that is a Class of a Second-Order Underactuated System”. J. of Vibration and Control 2019, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Park, B.S. Robust Control for Trajectory Tracking and Balancing of a Ballbot. IEEE Access 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, V.T.; Lee, S.G. Robust integral backstepping hierarchical sliding mode controller for a ballbot system. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2020, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D.B. Pham, S.G. D.B. Pham, S.G. Lee, T.H. Bui, T.P. Truong, Hierarchical Sliding Mode Control for a 2D Ballbot that is a Class of Second-Order Underactuated System, IntechOpen, 2022.

- Do, V.T.; Lee, S.G.; Mien, V. “Adaptive Hierarchical Sliding Mode Control for Full Nonlinear Dynamics of Uncertain Ridable Ballbots under Input Saturation”. Int. J. of Robust and Nonlinear Control 2021, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V.T. Do, S.G. V.T. Do, S.G. Lee, K.W. Gwak, “Passivity-based Nonlinear Control for a Ballbot to Balance and Transfer,” Int. J. of Control Automation and Systems, vol. 17, no. 10, 2019.

- Jang, H.G.; Hyun, C.H.; Park, B.S. Neural Network Control for Trajectory Tracking and Balancing of a Ball-Balancing Robot with Uncertainty. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.B.; Kim, J.J.; Lee, S.G. “Combined Control with Sliding Mode and Partial Feedback Linearization for a Spatial Ridable Ballbot”. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2019, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.B.; Weon, I.S.; Lee, S.G. Partial Feedback Linearization Double-Loop Control for a Pseudo-2D Ridable Ballbot. Int. J. of Control, Automation and Systems 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V.T. Do, D.B. Pham, S.G. Lee, Design of an energy-based controller for a 2D ball segway, 17th Int. Conf. on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS), Jeju, Korea (South), 2017.

- R. Esfandiari and B. Lu, Modeling and Analysis of Dynamic Systems, Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2010.

- R. Kelly, V. Santibáñez, and A. Loría, Control of Robot Manipulators in Joint Space, Springer, 2005.

- L.A. Vázquez, F. Jurado, C.E. Castañeda, and V. Santibáñez,“Real–time decentralized neural control via backstepping for a robotic arm powered by industrial servomotors,” IEEE Trans. on Neural Net. and Learning Syst., vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 419–426, 2018.

- L.A. Vázquez, F. Jurado, C.E. Castañeda, and A.Y. Alanis,“Real–time implementation of a neural integrator backstepping control via recurrent wavelet first order neural network,” Neural Proc. Lett., vol. 49, pp. 1629–1648, 2019.

- T. Takagi and M. Sugeno, “Fuzzy identification of systems and its applications to modeling and control,” IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cyber., vol. 15, pp. 116-132, 1985.

- H.O. Wang, K. Tanaka and M. Griffin, An analytical framework of fuzzy modeling and control of nonlinear systems: stability and design issues, Proc. 1995 American Control Conf., Seattle, pp. 2272-2276, 1995.

- F. Jurado, B. Castillo–Toledo, and S. Di Gennaro, Stabilization of a Quadrotor via Takagi–Sugeno Fuzzy Control, Proc. of the 12th World Multi–Conference on Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics: WMSCI 2008, Orlando, FL, 2008.

- F. Jurado, G. Palacios, F. Flores, and H. M. Becerra, “Vision-based trajectory tracking system for an emulated quadrotor UAV,” Asian J. of Control, vol. 16, issue 3, pp. 729-741, 2014.

- M.A. Llama, W. De La Torre, F. Jurado, and R. Garcia-Hernandez, “Robust Takagi–Sugeno fuzzy dynamic regulator for trajectory tracking of a pendulum–cart system,” Mathematical Problems in Engineering, vol. 2015, Article ID 247682, 11 pages, 2015. [CrossRef]

- L.X. Wang, A Course in Fuzzy Systems and Control. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall PTR, 1997.

- H.O. Wang, K. Tanaka and M. Griffin, Parallel Distributed Compensation of Nonlinear Systems by Takagi–Sugeno Fuzzy Model, Proc. FUZZ-IEEE/IFES’95, pp. 531-538, 1995.

- K. Tanaka and H.O. Wang, Fuzzy Control Systems Design and Analysis: A Linear Matrix Inequality Approach, John Wiley & sons, Inc., 2001.

- R. Enemegio, F. Jurado, and J. Villanueva-Tavira, Takagi-Sugeno Fuzzy Controller Design for an EV3 Ballbot Robotic System, Proc. of the 2022 International Conference on Mechatronics, Electronics and Automotive Engineering (ICMEAE), Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico, 2022.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Units |

| Mass of the body | 0.7448 | kg | |

| Mass of the ball | 0.0139 | kg | |

| Radius of the wheel | 0.0222 | m | |

| Radius of the ball | 0.026 | m | |

| Body moment of inertia | kg | ||

| Ball moment of inertia | kg | ||

| Height of the centre of mass | L | 0.155 | m |

| Gravity acceleration | 9.81 | m/ | |

| Gear ratio, motor ball | – | ||

| DC motor moment of inertia | 1× | kg | |

| Friction between body and surface | 0 | Nms/rad | |

| Friction between body and ball | 0.0022 | Nms/rad | |

| DC motor torque constant | 0.317 | Nm/A | |

| DC motor resistance | 6.69 | ||

| DC motor back EMF constant | 0.468 | V s/rad |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).