1. Introduction

The confluence of subtropical and subarctic waters forms the distinct Subpolar Front in the Japan Sea (JS), that lies between 39° and 41°N and extends across the whole basin from the Korean coast to the Japanese islands [

1,

2,

3,

4] (

Figure 1). The zonal eastward flow along the front is known to be highly variable with seasonal migration [

5,

6]. Meandering of the frontal flow is accompanied with formation of eddies of different polarity and sizes generated through a baroclinic instability [

7,

8]. In the previous studies, anticyclonic eddies (ACEs) have been often observed in the area north of Yamato Rise by satellite images [

9,

10,

11,

12], in the current meter observations at the mooring station M3 [

13] and during oceanographic surveys [

2,

14,

15,

16]. The topographically controlled mesoscale ACEs have been simulated with the help of a numerical circulation model by Prants et al. [

17] that showed the formation of such eddies in the cold season and stagnation over the bottom topography between sea mounts and bottom depressions. The quasi-stationary ACEs have been shown to be sufficiently nonlinear to exist as a stable entity. The quasigeostrophic nonlinearity parameter (the ratio of the relative vorticity advection to the planetary vorticity advection) has been estimated to be in the range of 3.3–6.6 [

17].

The quasi-stationary frontal eddies in the northern JS have been sampled and studied much more rarely then quasi-stationary eddies in the southern part of the Sea like the warm Ulleung quasi-stationary ACE in the Ulleung Basin [

5,

8,

18], the ACE over bottom topography around the Oki Spur, the Wonsan ACE [

7] and the Doc cyclonic eddy in between the Ulleung and Oki ACEs [

19]. All these eddies have been well studied with the help of ship and satellite observations, surface drifters and profiling floats.

In this paper, we have analyzed another area to north of the Subpolar Front in the northwestern JS where mesoscale eddies regularly form, circulate and decay (

Figure 2). The frontal eddies in the northwestern JS are also interesting because they form in the area where warm subtropical and cold subarctic waters mix with an impact on marine ecosystem. It may be important for understanding transport pathways [

16,

20] for invasions of subtropical species. Since the last decades in the twentieth century, invasions of warm-water fish (conger eel, tuna, moonfish and triggerfish) and some tropical and subtropical marine organisms (turtles, sharks and others) have been observed more and more often in the northwestern JES, near the coast of Russia [

21].

We study a frontal ACE, called further as eddy A, in the northwestern JS that has been sampled in May of 2004 (

Figure 1). This large-scale eddy lasted exceptionally long time as an entity allowing us to track its evolution from formation to decay with the help of altimetry-based Lagrangian indicators. Our aim is to document the essential events in the evolution of this eddy based of Lagrangian maps, to identify the origin of water masses that were gained, retained, and released by the eddy and to compare the simulation results with ship observation data and satellite infrared images. For this purposes, Lagrangian approach seem to be more appropriate than commonly used Eulerian means because the Lagrangian maps are imprints of the history of water involved in the vortex motion, whereas vorticity, the Okubo-Weiss parameter and similar Eulerian indicators are just ‘instantaneous’ snapshots.

The paper is organized as follows. The CTD data obtained from the shipboard observations and satellite data are described in section 2.

Section 2 introduces also the automated tracking algorithm for detection of eddies and Lagrangian methods that we used in the present paper.

Section 3 presents the area of the most frequent formation of anticyclonic eddies just to the north of Subpolar Front by AMEDA algorithm, and the eddy A vertical structure and composition of water masses in its core by the results of shipboard observations. In section 4, we document the essential events in the eddy’s evolution based of Lagrangian maps and compare the simulation results with satellite infrared images. The calculation of the content of waters of subtropical and subarctic origin inside the eddy core and its temporal development is also present in

Section 4. The results are discussed in

Section 5.

4. Lagrangian Analysis of Evolution of the Eddy

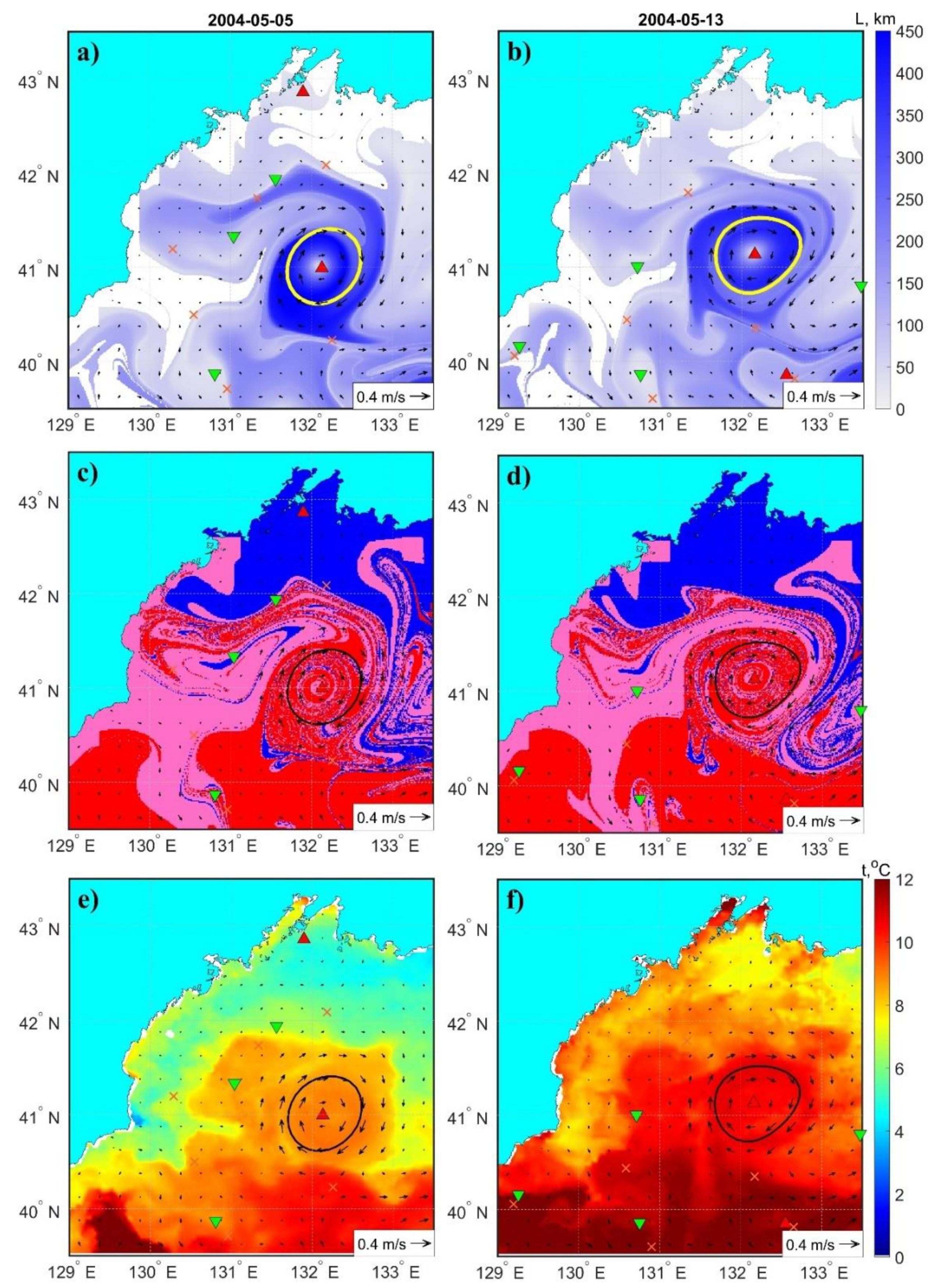

The altimetry-based L-, O- and T- maps were computed daily (see Sec. 2.4) and analyzed in this section to study the evolution of the studied eddy and some of its properties. The inspection of those Lagrangian maps allows us to track the eddy during its lifetime. To validate the simulation results, we use SST images obtained on the same dates as the Lagrangian maps.

The eddy was formed from a meander-like feature of the Subpolar Front. The elliptic point, that was the center of the newborn eddy, appeared on Lagrangian maps in

Figure 6a and c on January 9, 2004 at (40.4°N, 131.2°E) signaling its birth. The red color on origin maps in

Figure 6c and d codes the Lagrangian particles which crossed the Subpolar Front from south for 365 days prior the dates indicated on the maps. More exactly, they crossed during this period of time the 39°N latitude somewhere in the range of 127°–140°E and represent subtropical water. The blue color codes the particles which crossed the 42.6°N latitude from north, and they represent subarctic water. The rose color codes water parcels which got into AVISO coastal grid cells for 365 days prior the dates indicated on the maps. Calculation of trajectories of particles backward in time was stopped when they reached one of the coastal AVISO cells. These Lagrangian particles originate in the along-shore North Korean Cold Current.

It follows from the Lagrangian maps in

Figure 6c and d that the eddy was filled up with a subtropical ‘red’ water. This water inclined into the ‘rose’ water originated in the along-shore North Korean Cold Current. The eddy grew fast and reached ~80 km in diameter during the week after formation (

Figure 6b and d). The darker the color on L-maps, the greater the distance the corresponding particles traveled in the past. The spiral-like filament of the ‘dark blue’ water in

Figure 6b illustrates clearly the process of eddy formation. The SST images in

Figure 6e and f, taken on the same dates as the shown L- and O-maps, confirm the Lagrangian simulation, including formation of the eddy from the intrusion of subtropical water.

Inspecting the gallery of daily computed L-maps and infrared images, we have found that the eddy experienced some deformations during its lifetime including events with entrainment and detrainment of water, splitting and merger with other eddies and eventual decay in October of 2004. The first splitting of the eddy occurred after a month after the formation between 15 and 25 February.

Figure 6 shows how the splitting looks on L-maps and SST images. A blob-like feature with the ‘dark blue’ water in

Figure 7a, split off from the parent eddy in the second half of February. The birth of an elliptic point at (41.3°N, 132°E) signaled appearance of the newborn eddy (

Figure 7b). This splitting is also seen on the SST images in

Figure 7c and d where the newborn eddy contained warmer water in the surface core as compared to the core of the parent eddy.

Just after splitting, the parent eddy begun to interact intensively with the newborn eddy. As the result, it eventually absorbed the newborn eddy. This process was signaled by disappearance of the elliptic point of the newborn eddy on March 5 (

Figure 8a). The united eddy has grown up gradually and reached almost circular shape by the beginning of April with the diameter of 100 km (

Figure 8b). The O-maps in

Figure 8c and d allow us to identify the subtropical origin of the water wrapped onto the eddy core. The process is complicated with the entrainment of a small amount of ‘blue’ subarctic water and ‘rose’ coastal water. The O-maps demonstrate bands of waters of different origin around the eddy periphery. The entrainment process is seen in the SST field as well (

Figure 8e and f) but only partially due to cloudiness in the beginning of March.

Just before sampling, the eddy again entrained water from the surrounding (

Figure 9). The L-maps in

Figure 9a and b show a streamer of this water as the long blue ‘tail’. It follows from

Figure 9c and d that the streamer carried mostly a subtropical ‘red’ water. SST images in

Figure 8e and f confirm that. The entrainment process had started in the end of April and continued until the days of sampling (May 11–16).

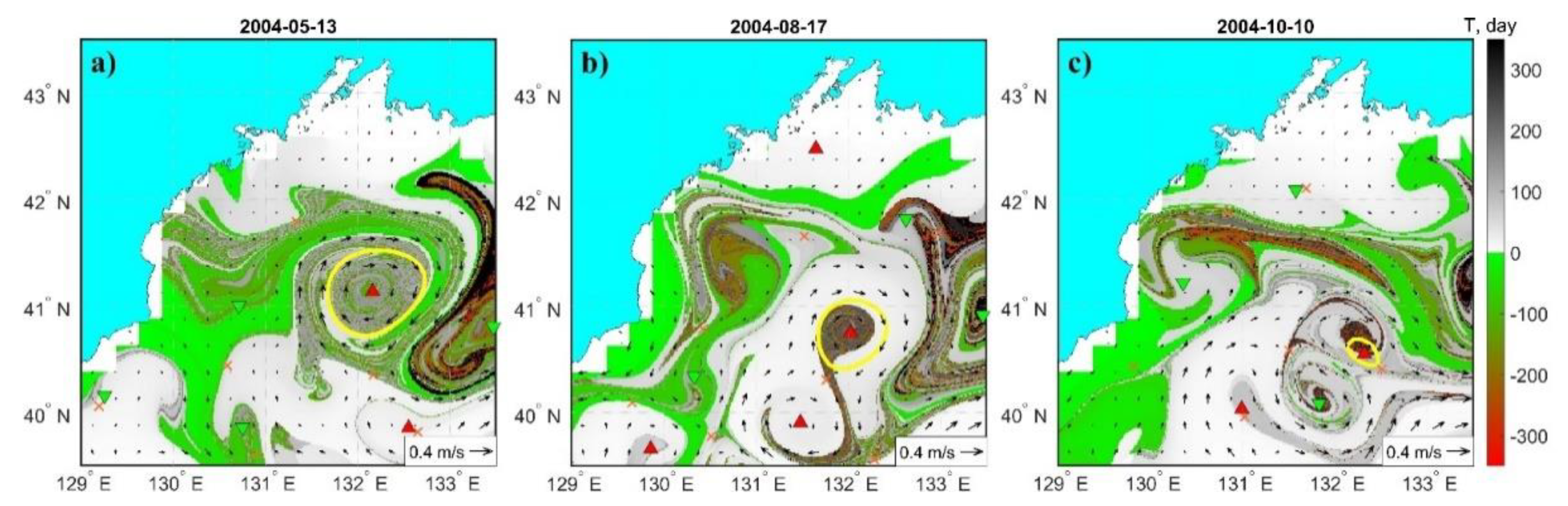

The information on the ‘age’ of water in the study area, and in particular, inside the surface eddy core, can be obtained from T-maps computed for 365 days backward in time (see Sec. 2.4). The T-map in

Figure 10a shows the studied eddy on the day of sampling when it has the maximum lateral size. By this time, the eddy predominantly consisted of a subtropical grey water which spent in the study area between 100 and 200 days. The darker the color, the older the core water is. The green and rose colors represent the ‘age’ of the coastal water, i.e., the green and rose particles got into the blue AVISO coastal grid cells for 365 days prior the dates indicated on the maps, and after that they were not integrated. Inclusions of the comparatively ‘young’ coastal water are present not only along the eddy periphery but inside the core as well.

The gradual erosion of the eddy resulted in a significant reduction of the eddy size (

Figure 10b and c). The interaction of the weakened eddy A, filled with the ‘old’ subtropical water, with a young ACE of the Subpolar Front to south is shown in

Figure 10b on August 17. By this time, the eddy was considerably

shrunken. The eddy A decayed due to interaction with the zonal eastward flow that eventually absorbed the eddy on October 10. This event was signaled by disappearance of the elliptic point inside the eddy (

Figure 10c). Thus, the life of the eddy lasted nine months, from January 9 to October 10, 2004. During this long period of time, we were able to track the eddy as an entity using daily Lagrangian maps and the AMEDA eddy tracking algorithm.

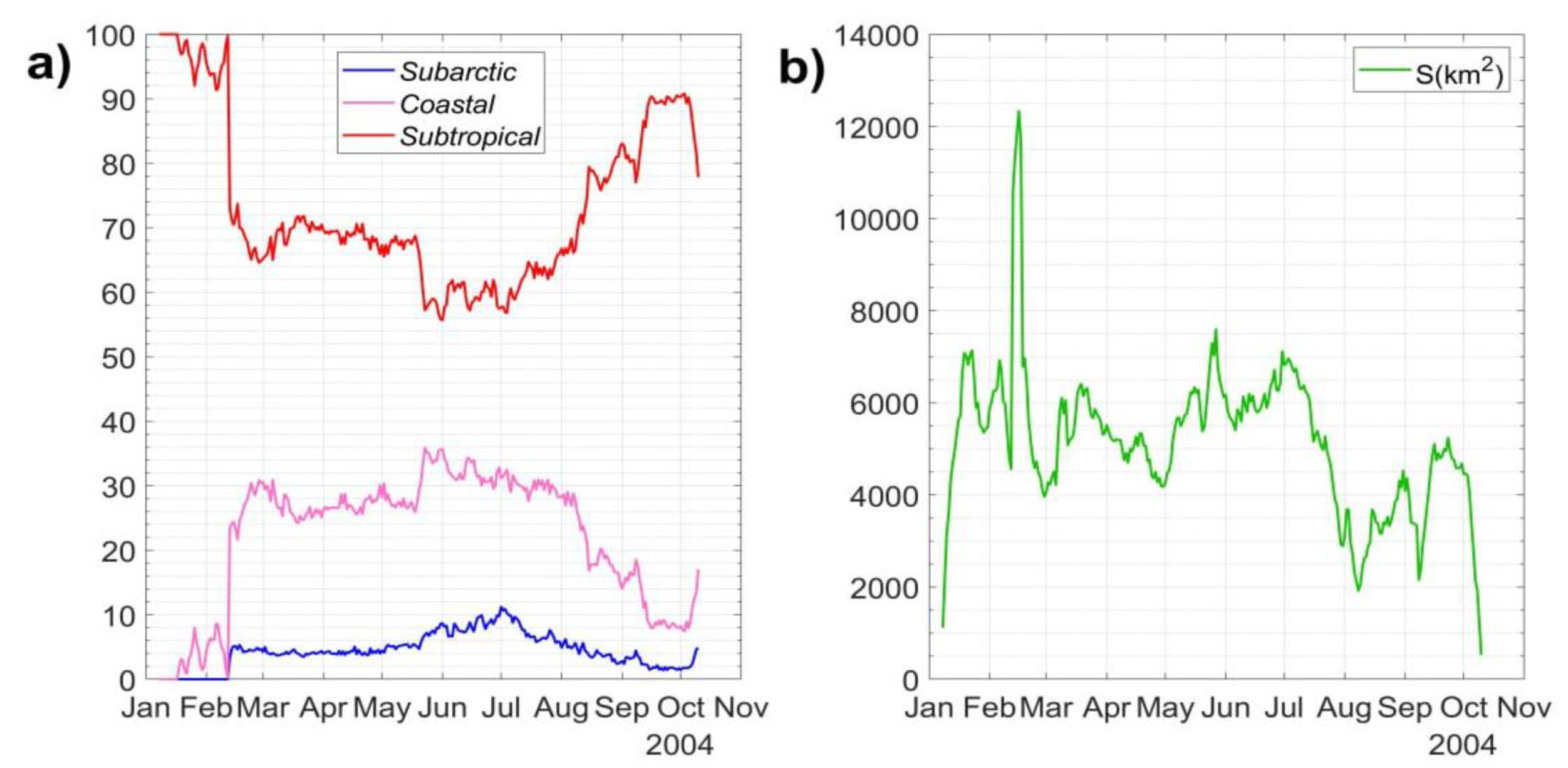

To calculate the percentage of waters of different origin in the surface core, we count every day the number of subtropical, subarctic and coastal particles, , and , inside the characteristic eddy contour delineating the core of the eddy at the surface (see Sec. 2.1). The subtropical and subarctic particles are distinguished as those ones which crossed the zonal lines 39°N and 42.6°N from south and north, respectively, entered the study area for 365 days prior the date indicated on the plot and detected inside the vortex contours. The coastal particles mark coastal water which has been trapped by the eddy.

In

Figure 11a we plot the percentage of subtropical, subarctic and coastal waters in the eddy core during its lifetime that was calculated by dividing

,

and

by the current value of the area under the vortex contour. During the entire lifetime of the eddy, the surface core has been filled mainly with the subtropical water originated in the southern flank of the Subpolar Front. It is consistent with the origin maps in

Figure 6, 7, 8 and 9 which show the subtropical water by red color. The episodes with cardinal changes of the percentage of water of different origin in

Figure 11 can be compared with the Lagrangian maps on the same dates. An entrainment of the ‘rose’ coastal water begun from February 9. That is reflected in

Figure 11a as a rapid increase of portion of coastal water in the vortex core by February 13

due to the decline in the content of subtropical water. Starting from this date, a small amount of subarctic water appears in the core for the first time. The coastal water made up a significant portion of the surface core water until the middle of August (see

Figure 10a and the T-map in

Figure 9b, where this water is shown in grey). An entrainment of the coastal water occurred also in the middle of May (see

Figure 10 and O-maps and SST images in

Figure 9), when the eddy was sampled. The final decrease of the content of the subtropical water occurred in the end of life of the eddy (see

Figure 11a and the T-map in

Figure 10c). As to subarctic water, its amount in the surface core was practically the same from February 13 and by the eventual decay.

The area under the characteristic eddy contour, delineating the surface core, rapidly increased after the formation of the eddy reached approximately 100 km in size by the middle of January. The maximum size of ~120 km was recorded by the middle of February after an entrainment of a large amount of subtropical and coastal waters. Just after that, the eddy destabilized and split into two parts. The erosion of the eddy begun in the beginning of July when it decreased in size from 100 km to 50 km for the month. The eventual decay started in the beginning of October and finished on October 10 (see

Figure 10d).

5. Discussion

We used the Lagrangian approach to study the evolution of an ACE in the northwestern JS. On the one hand, this eddy was formed in the region near the Subpolar Front where mesoscale eddies regularly appear and circulated. On the other hand, it was an exceptional long-lived eddy observed with Lagrangian data over 9 months. The eddy was a strong dynamic feature with the diameter reaching 120 km and extended vertically to the bottom that was sampled in details with CTD observations.

We have demonstrated a multilayer structure of this eddy based on ship observations. The eddy had a core of warm and low salinity water between 250 and 400 m which is typical for the eddies observed in the northwestern JS earlier [

15]. However, we found other anomalies in its structure which have not observed before including a core of warm and relatively high salinity water between 30 and 230 m, that are slightly warmer and saline as compared to the surroundings, and surface water above the seasonal picnocline. These anomalies in a vertical composition of different water masses in the eddy could be explained by the peculiarities of its evolution.

Using Lagrangian approach, we have traced the eddy evolution over 9 months since January through October 2004. Based on daily-computed L- maps and maps of water origin and water ‘age’ we found a few events of entrainment of surrounding water by the eddy, splitting and merger with neighbor eddies. These events were confirmed by satellite infrared images.

Our analysis demonstrated that an entrainment of subtropical water from the south into the eddy dominated during the whole period of its evolution. It was especially strong in the beginning and in the end of the eddy life cycle, in January and in October. Just after formation and isolation of the eddy from the flow of subtropical water, an entrainment of coastal water surrounding the eddy has increased. Subarctic water from the north was also observed to be entrained into the eddy, however its volume was around ten times lower as compared to that of subtropical water. Large entrainment of surrounding water into the eddy in February caused its rapid enlargement and splitting into two eddies later in this month. Entrainment of surface water from the south, from the area of the Subpolar Front just prior to the ship observation was responsible for formation of surface warm water in the upper 0–30 m observed in the middle of May (WI at

Figure 5a).

It is however difficult to explain the origin of higher salinity water in the upper core (HS1 at

Figure 5a) and the origin of lower salinity core (LS at

Figure 5a). The first water mass could be formed during the process of formation of the eddy in January (

Figure 6c and e). The second one could be the result of entrainment and subduction of low salinity intermediate water from the north. It is difficult to judge on the subsurface entrainment and subduction processes using Lagrangian approach based on the satellite altimetry.

Because the simulation results are based eventually on the AVISO velocity field which is imperfect by many reasons, we need to discuss the adequacy of our Lagrangian results in representing reality. First of all, we compared these results, when possible, with observation data and infrared images. The second evidence of the reliability of the results obtained is more sophisticated. The altimetric velocity field in active dynamical areas is, in principle, chaotic (turbulent). Regarding the simulation of particle’s trajectories, it is impossible to obtain ‘true’ trajectories in a chaotic and imperfect velocity field. Even if it would be absolutely perfect, it is impossible to do this because of the exponential sensitivity of output results on small variations in initial conditions and parameters in the real ocean. It is known [

27] that the distance between initially closed by particles grows exponentially (on average) with time in a chaotic velocity field resulting in unpredictability of their positions over a definite time interval. This means that any error in specifying initial particle’s positions grows so quickly that it becomes practically impossible to predict final positions with a reasonable confidence interval.

However, in strongly chaotic systems each numerically computed trajectory stays uniformly close to some ‘true’ trajectory with slightly altered initial position [

27]. In other words, a computed trajectory is ‘shadowed’ by a ‘true’ one. By integrating advection equations, we compute not a ‘true’ trajectory but a trajectory that is close to this ‘true’ trajectory, and we do not know which one. Therefore, computation with a large number of particles, allows us to track the real pathways of water even in a chaotic field. Thus, in spite of the impossibility of obtaining a specified ‘true’ trajectory, computed pathways for a large congregation of particles approximate real pathways.

As to simulating the processes inside the eddy core, it should be stressed that a large-scale velocity field is smooth and regular there. It allowed us to identify the eddy center with a good accuracy exceeding the nominal resolution of the geostrophic field. Comparing the coordinates of the eddy center in the sampling sections in

Figure 3 (41°09’N and 131°15’E) with the calculation of the eddy center on the days of sampling in

Figure 9b (41°08’N and 131°11’E), we may conclude that they coincide with the good accuracy of 9 km.

Figure 1.

Fronts and eddies in the Japan Sea based on 10-day mean temperature distribution at 100 m depth for 11–20 May 2004 (JMA data). Schematic location of the Subpolar Front is indicated by the white dashed line (SF). Warm-core anticyclonic eddies are observed to the north of the front (A), over Yamato Rise (YE), in the Ulleung Basin (UE), east off Oki Spur (OE) and at other locations. Location of the studied anticyclonic mesoscale eddy on these dates is indicated as A.

Figure 1.

Fronts and eddies in the Japan Sea based on 10-day mean temperature distribution at 100 m depth for 11–20 May 2004 (JMA data). Schematic location of the Subpolar Front is indicated by the white dashed line (SF). Warm-core anticyclonic eddies are observed to the north of the front (A), over Yamato Rise (YE), in the Ulleung Basin (UE), east off Oki Spur (OE) and at other locations. Location of the studied anticyclonic mesoscale eddy on these dates is indicated as A.

Figure 2.

The occurrence frequency of anticyclones with the lifespan exceeding 30 days in the northwestern Japan Sea in 1993–2021 with the imposed formation (a) and decay (b) sites. The sites of formation and decay of the studied eddy are shown in a) and b) by stars on January 9 and October 10, 2004, respectively.

Figure 2.

The occurrence frequency of anticyclones with the lifespan exceeding 30 days in the northwestern Japan Sea in 1993–2021 with the imposed formation (a) and decay (b) sites. The sites of formation and decay of the studied eddy are shown in a) and b) by stars on January 9 and October 10, 2004, respectively.

Figure 3.

(a) Temperature and (b) salinity distribution at 300 m based on ship CTD observations in 11–16 May, 2004. Location of the studied eddy A is indicated by the arrow.

Figure 3.

(a) Temperature and (b) salinity distribution at 300 m based on ship CTD observations in 11–16 May, 2004. Location of the studied eddy A is indicated by the arrow.

Figure 4.

(a) Dynamic topography of the sea surface relative to 1500 m (dyn m) and (b) vertical distribution of meridional component of geostrophic velocity (cm/c) along the section 41°09’N crossing the eddy A based on the ship CTD observations in 11–16 May, 2004. Red and blue color correspond to northward and southward flows.

Figure 4.

(a) Dynamic topography of the sea surface relative to 1500 m (dyn m) and (b) vertical distribution of meridional component of geostrophic velocity (cm/c) along the section 41°09’N crossing the eddy A based on the ship CTD observations in 11–16 May, 2004. Red and blue color correspond to northward and southward flows.

Figure 5.

(a) Temperature (°C) and (b) salinity (psu) distributions along the zonal section (41°09’N) crossing the eddy A based on the CTD observations in 14–16 May, 2004. WI – warm intrusion; UC – vertically uniformed core; HS1 – upper high salinity layer; LS – low salinity core; HS2 – lower high salinity layer.

Figure 5.

(a) Temperature (°C) and (b) salinity (psu) distributions along the zonal section (41°09’N) crossing the eddy A based on the CTD observations in 14–16 May, 2004. WI – warm intrusion; UC – vertically uniformed core; HS1 – upper high salinity layer; LS – low salinity core; HS2 – lower high salinity layer.

Figure 6.

Backward-in-time Lagrangian maps and SST images in January 2004. (a) and (b) L-maps, (c) and (d) origin maps with imposed AVISO velocity field show the eddy formation. Rose color on the maps codes virtual particles which got into AVISO coastal grid cells prior the dates indicated on the maps. Gradation of the blue color on the L-maps shows the length of the pass covered by the virtual particles for 30 days in the past. Red and blue colors on the origin maps code subtropical and subarctic waters, respectively. The black curves on the O-maps are characteristic contours of the studied eddy (see Sec. 2.1). These contours delineate the core of the eddy at the surface. (e) and (f) SST images on the same dates as in Lagrangian maps (white color means cloudiness). The up(down) oriented triangles denote elliptic points corresponding to the locations of centers of anticyclones (cyclones). The crosses are hyperbolic points.

Figure 6.

Backward-in-time Lagrangian maps and SST images in January 2004. (a) and (b) L-maps, (c) and (d) origin maps with imposed AVISO velocity field show the eddy formation. Rose color on the maps codes virtual particles which got into AVISO coastal grid cells prior the dates indicated on the maps. Gradation of the blue color on the L-maps shows the length of the pass covered by the virtual particles for 30 days in the past. Red and blue colors on the origin maps code subtropical and subarctic waters, respectively. The black curves on the O-maps are characteristic contours of the studied eddy (see Sec. 2.1). These contours delineate the core of the eddy at the surface. (e) and (f) SST images on the same dates as in Lagrangian maps (white color means cloudiness). The up(down) oriented triangles denote elliptic points corresponding to the locations of centers of anticyclones (cyclones). The crosses are hyperbolic points.

Figure 7.

(a) and (b) L-maps, (c) and (d) SST images with imposed AVISO velocity field show splitting of the eddy A (yellow and black contours) in February.

Figure 7.

(a) and (b) L-maps, (c) and (d) SST images with imposed AVISO velocity field show splitting of the eddy A (yellow and black contours) in February.

Figure 8.

(a) and (b) L-maps, (c) and (d) origin maps, (e) and (f) SST images with imposed AVISO velocity field show interaction of the splitting products, merger of these products on March 5 and entrainment of water by the united eddy.

Figure 8.

(a) and (b) L-maps, (c) and (d) origin maps, (e) and (f) SST images with imposed AVISO velocity field show interaction of the splitting products, merger of these products on March 5 and entrainment of water by the united eddy.

Figure 9.

(a) and (b) L-maps, (c) and (d) origin maps, (e) and (f) SST images with imposed AVISO velocity field show interaction of the splitting products, merger of these products on March 5 and entrainment of water by the united eddy.

Figure 9.

(a) and (b) L-maps, (c) and (d) origin maps, (e) and (f) SST images with imposed AVISO velocity field show interaction of the splitting products, merger of these products on March 5 and entrainment of water by the united eddy.

Figure 10.

The water-age T-maps show how ‘old’ is the water inside the studied eddy shown by the yellow contour. Three events in its biography are shown: (a) sampling on May 13, when the eddy had a maximum lateral size, (b) interaction of the weakened eddy with an anticyclone of the Subpolar Front on August 17 and (c) eventual decay on October 10. The legend of colors: nuances of the grey color represent the ‘age’ of subtropical water, green and rose colors represent the ‘age’ of coastal water, the white area to the north of eddy is covered by subarctic water. The blue areas are the AVISO coastal cells.

Figure 10.

The water-age T-maps show how ‘old’ is the water inside the studied eddy shown by the yellow contour. Three events in its biography are shown: (a) sampling on May 13, when the eddy had a maximum lateral size, (b) interaction of the weakened eddy with an anticyclone of the Subpolar Front on August 17 and (c) eventual decay on October 10. The legend of colors: nuances of the grey color represent the ‘age’ of subtropical water, green and rose colors represent the ‘age’ of coastal water, the white area to the north of eddy is covered by subarctic water. The blue areas are the AVISO coastal cells.

Figure 11.

(a) The percentage of subtropical (red), subarctic (blue) and coastal (rose) waters inside the surface core during the lifetime of the eddy. (b) The area of the surface core of the eddy during its lifetime.

Figure 11.

(a) The percentage of subtropical (red), subarctic (blue) and coastal (rose) waters inside the surface core during the lifetime of the eddy. (b) The area of the surface core of the eddy during its lifetime.