Introduction

In an international agreement, the United Nations (UN) (2015) proposed the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to establish global objectives, in order to achieve a sustainable future for people. The fourth goal of the SDGs states that quality education “aims to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” (UN, 2015, par. 1). Quality of education reduces socio-economic and gender inequalities, and promotes tolerance and peaceful coexistence (UN, 2018). According to the UN, people can have better jobs and better lives with a good education.

To reach this goal in Colombia, various authors consider bilingualism as one of the components to have a better education, because it represents a tool to communicate and have access to more opportunities, such as jobs, knowledge, scholarships, cultural exchanges, cognitive development, etc. (Luengo, 2004; Cárdenas & Miranda, 2014; Mineducación, 2006). In the Colombian educational context, English language has been adopted by the Colombian government to design the bilingual policy. The national bilingual policy has been materialized through several initiatives such as “Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo” (PNB) (2004-2019), “Colombia Bilingüe” (CB) (2014-2018) and “Programa Nacional de Inglés - Colombia Very Well” (CVW) 2015-2025. In the country, bilingualism (Spanish - English) is considered as an engine for development and English has become the target language to be achieved. This view arises from the need of the population to speak a foreign language, which allows them to communicate and be competent in the 21st century.

The Ministry of National Education in Colombia (Mineducación) proposes English teaching as a necessity of the country in the face of the challenges of globalization. According to the Mineducación (2006), bilingualism consists of the development of communicative competence, including linguistic, pragmatic and sociolinguistic competence. These competences require critical reading, grammar understanding, writing, listening and speaking correctly in a foreign language, in this case English. In the field of bilingualism, Cárdenas (2006) as cited in Bernal (2020) argues that "bilingualism is a natural process and therefore it is not achieved through the imposition of policies, but by providing the conditions and taking into account the needs of the diverse Colombian realities" (p. 45).

Different investigations have addressed the study of the implementation of educational policies about bilingualism, from the national to the municipal context. To date, these studies have found that the programs have not obtained the expected learning results in students and teachers according to the national goals (Cárdenas & Miranda, 2014). Gómez (2021) points out that one issue that hinders the achievement of such goals at the administrative level is the fact that hiring regulations for public education do not require English teachers to demonstrate English proficiency. The author also states that another challenge for public education is the budgetary limitation to meet the goals of bilingual programs. Furthermore, it is important to ensure the continuity, uniformity and a grounded structure of bilingual programs at the national level, in this way they would not depend on the changes of municipal administration (De La Cruz & Jaramillo, 2022; Hurtado, 2021). In addition, English learning must be strengthened through the integration of the knowledge of all school subjects, so that bilingualism could be meaningful in the daily use of students (Hurtado, 2021). Considering the previous findings, despite the importance of promoting bilingualism for Colombian society, its implementation is still deficient. Although these studies have described the limitations and challenges of bilingual policies in Colombia, there is still the need to examine how the policies have been implemented at the local level and how this implementation compares to national policies.

This paper examines the characteristics of the programs to promote bilingualism in the municipality of Tuluá, Valle del Cauca, from 2013-2021. The focus of the study is to investigate the effects of the bilingualism law (Ley 1651 de 2013) on the national, departmental, and municipal level programs. Documentary research was used as the methodological design (Baena, 2017), and the analytic method data analysis stages (Lopera et al., 2010) were employed to analyze the results. The results of the analysis of the national Saber11 tests (2013-2021) in relation to the implemented bilingual programs over the same period provide insight into the actions and results of the previous bilingual programs (Gómez, 2021; Cárdenas & Miranda, 2014). The findings of the documentary analysis offer an understanding of the implications of bilingualism policies at the national, departmental, and municipal levels, and their effects on students’ learning results. As such, the paper further contributes to the body of knowledge on the construction of bilingual policies at the municipality level. The structure of this paper is divided into the following sections: the theoretical background, the methodology, the results and discussion, the conclusions and recommendations, and finally, suggestions for future research.

Theoretical Framework

Bilingualism

According to the Ministerio de Educación Nacional (2006), bilingualism is defined as "the different degrees of proficiency with which an individual is able to communicate in more than one language and culture" (p. 5). This concept can be applied to contexts where a second or foreign language is used (Mineducación, 2006). Oestreicher (1974) proposed important criteria for defining bilingualism such as the development of speaking, listening, reading, and writing skills in different linguistic contexts. Additionally, linguistic functions in bilingualism are based on a person’s capacity to use two languages and switch between them fluently. Lastly, attitudes are also considered a criterion for bilingualism, in which the user is part of the linguistic community and interacts with the new culture (Thiery, 1978).

Bilingualism has been explored from three theoretical positions: the maximalist, minimalist and neutral or functional perspectives (Bloomfield, 1933; Oestreicher, 1974; Thiery, 1978; Lambert, 1975, as cited in Reynolds, 1991; Galindo, 2012; Haugen, 1972, in Alonso, Gallo, & Torres, 2012; Macnamara, 1967). These perspectives are delimited by the characteristics of the contexts. The maximalist position suggests that a bilingual person is able to master two languages equally as a native speaker. Thiery (1978) also posits that a bilingual individual is a member of two different linguistic communities, holding approximately the same social and cultural level. The term "additive bilingualism" is used to refer to the learning of a second language in a social immersion, without threatening or replacing the first language (Lambert, 1975, as cited in Reynolds, 1991). On the other hand, the minimalist position states that a bilingual person must possess a minimum proficiency in at least one of the communicative skills (Galindo, 2012). Finally, bilingualism from a more flexible and functional conception proposes that an individual can produce expressions in another language and understand its meanings, without the need to master the language as a native speaker (Haugen, 1972, in Alonso, Gallo, & Torres, 2012; Macnamara, 1967).

The neutral or functional position in relation to school learning environments is third in line. Bilingualism from this standpoint implies the ability of students to communicate in everyday contexts, despite having unequal levels of communicative skills (Galingo, 2012). Macnamara (1966) further suggests that a bilingual person is an individual who has managed to develop the four language skills of speaking, listening, reading, and writing in a second or foreign language, even at its most basic level. To ensure that teachers and students achieve the desired outcomes, the Ministry of Education in Colombia has embraced the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) with Decrees 3870/2006 and 4904/2009, and Mineducación has put in place procedures to assess the English language proficiency of students through Colombian Institute for the Promotion of Higher Education (ICFES) tests. This, in turn, enables the educational system to identify areas of improvement and contextualize language and educational policies.

Language policy

Language policy is an important concept that informs this study. According to Torres-Melo and Santander (2013), public policies reflect the ideals of a society and seek the common good. In the field of education, particularly language policies, the same applies. Johnson (2013) defines language policy as a “mechanism that impacts the structure, function, use or acquisition of a language” (p. 9). Tollefson (2006) adds that language policies should be oriented towards the promotion of democracy and reducing inequality, as well as preserving cultural heritage.

In Colombia, language policies are mainly divided into two categories: one that regulates the relationship between Spanish and minority languages and the other that promotes the inclusion of a foreign language. Both policies have a common goal of promoting multilingualism in Colombia, though they have their own advantages and disadvantages, as seen in previous studies. This article will focus on bilingual policy initiatives. The guidelines of these policies seek to create a “desired linguistic behavior” (Tovar, 1997). Language strategies framed by policies should follow a spiral cycle that begins with a description of the real and contextual situation, followed by implementation and concluded with an evaluation process.

Bilingual education policies and bilingual programs

According to Llano (2022), bilingual education policies and bilingual programs have been developed in Colombia with the aim of achieving educational objectives and curricular standards. However, the results of these plans have been questioned due to their failure in the implementation and fulfillment of their objectives. In this regard, Bastidas and Jiménez (2021) found that the first National Plan for Bilingualism (PNB, 2004-2019) has not been successful in terms of bilingualism indicators or state test results. Likewise, other researchers have found that the low English results are connected with these flawed national plans (Gómez, 2021; Cárdenas & Miranda, 2014). Furthermore, it has been argued that these plans embrace a reductionist view of bilingualism, privileging Spanish-English combinations while disregarding other languages such as French or German, or indigenous languages and cultures (Gómez, 2021). To tackle this, an intercultural approach has been proposed, which suggests bilingual teachers to help students to accomplish the national standards while providing them with intercultural content (Truscott de Mejía & Tejada, 2020; Byram et al., 2002; Perlaza et al. 2022).

On the other hand, previous studies on English teaching reveal that the Colombian government has not been able to cover the total number of specialized teachers in English in all regions and at all levels (Osorio et al., 2020). De la Cruz and Jaramillo (2022) ratified that bilingualism policies "do not favor the teaching and learning process of a foreign language, since they are not adapted to the educational context in Colombia" (p. 19); thus, they proposed that the language proficiency levels should be adjusted. According to Gomez (2021), there exists a lack of conditions for the implementation of the PNB in public education, which presents gaps that "constitute structural shortcomings of the public education system at the elementary, secondary and high school levels" (p. 37). Other researchers show another weakness in Colombian education. A structural gap for an inappropriate system of securing quality to evaluate the implementation of educational language policies; which causes the failure to achieve the goals or it is required more time to achieve them (Bastidas & Jimenez, 2021; Hurtado, 2021; Cardenas & Miranda, 2014).

Traditionally, it has been demonstrated the low level of English proficiency of teachers in elementary school. According to Correa et al. (2016), many professional educators and elementary school graduates specialized in other fields of knowledge such as social sciences end up teaching English. Other researchers identified as a determining factor the minimal time of allocation for English learning as a factor that has an impact on the non-achievement of the objectives set (Osorio et al., 2020). Some researchers have tried to implement new approaches as Content and Language Integrated Learning in order to enhance better results by showing the limitations of materials, English level of teachers and lack of time for the foreign language classes (Quintana et al. 2018; Medina-Soto, 2018; Romero-Martínez, 2017). Finally, "for a bilingual program to develop and consolidate properly, it requires a high command of the language on the part of teachers, and the greatest possible exposure of the students to it" (Hernández-Prados, 2021, p. 5).

Method

This qualitative research follows the principles of descriptive relational scope, which consists of specifying the properties and characteristics of the sample elements or categories of analysis. This method allows researchers to approach the sources of information from a flexible perspective, delimited from the conceptual elements and the study objectives. This qualitative research is not only characterized by the data, because in effect exists data that can be quantified. In this case, the method of analysis used is not mathematical (Deslauriers 2004). Furthermore, qualitative research is non-linear and it allows exploring the phenomenon in depth, allowing its interpretation and contextualization.

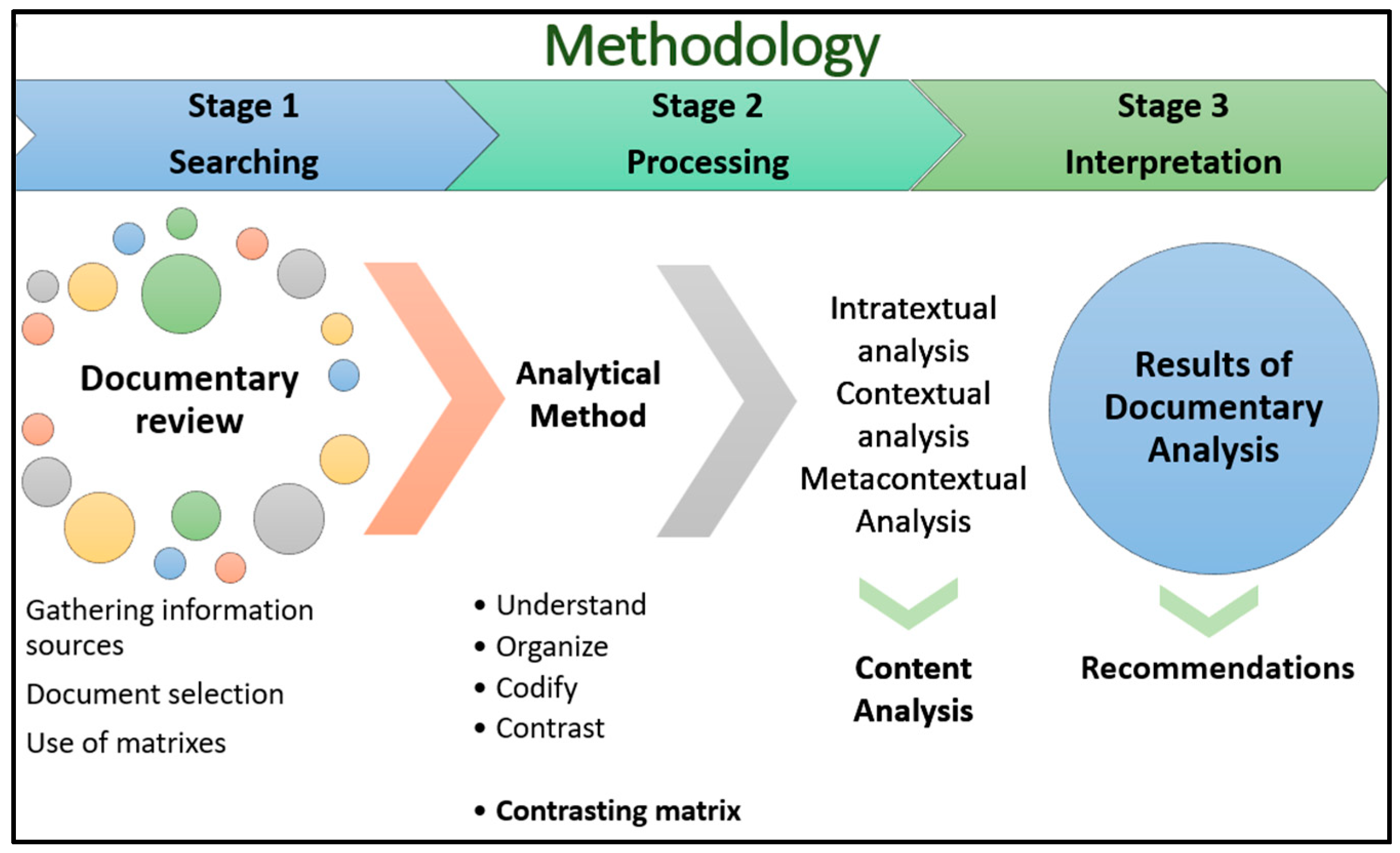

The research design brings together two complementary methods, the documentary analysis and the analytical method. Documentary research consists of the review, analysis and comparison of relevant bibliographic sources, in order to extract the information to support the research categories (Baena, 2017). The documentary stages carried out included the compilation of documentary sources obtained after consultation with experts and on the web. The systematic review of the sources made it possible to establish the relationship of the documents found with the topic under study. The documents selected in the matrices were reviewed in depth thanks to the creation of definitive documentary files. The results of the documentary analysis are expressed and strengthened by the four phases and the three readings of the analytical method.

In the analytical method, some authors define analysis as "the decomposition of a phenomenon into its constituent elements'' (Lopera et al., 2010). With this method, the researchers can approach the understanding of reality, from the complete decomposition of the components involved in a phenomenon or object of study. Likewise, another contribution of the analytical method is the depth of analysis that researchers can conduct. This content analysis includes intratextual reading, contextual reading and metacontextual reading (Lopera et al., 2010). The first level called intratextual corresponds to the detailed analysis that the researcher can make of each category; in this case, of the chosen documents related to the bilingual strategies or program in the municipality of Tuluá. The contextual level allows researchers to make a contrast between the discourses proposed by two or more programs or documents. The metacontextual reading enables the researchers to visualize in a panoramic view the contributions made by each work unit, considering the macro reality of the municipality and even of other sectors of the region such as Santiago de Cali or even at the national level.

For a better understanding of this methodology, the following figure presents how both methods and processes complement this research study. This figure (

Figure 1) contains the theoretical positions and methodological procedures adapted from Baena (2017) and Lopera et al. (2010).

Data collection

The study collected data from public documents and databases, as well as public libraries of UCEVA, the municipality and official web pages. The Secretary of Education Office of Tuluá (SEM) provided some documents and reports related to bilingualism in education from 2017 until 2021. The study reviewed and analyzed legal and official documents about bilingualism programs during the last 9 years. The final sample of this study has 25 programs, strategies, actions and policies for the analysis, following the steps of the analytical method.

Instruments

The documental analysis implemented diverse designs of matrices to develop the entire process. These matrices were created by the researchers and they are divided into three categories: the information processing matrix, the codification matrix and the contrast matrix. The information processing matrix contains the characterization of the policies, programs and strategies implemented between 2013 and 2021, including the institutions in charge and covenants, duration, and population. This process corresponds to the second stage of processing information and intratextual analysis. The codification matrices allowed researchers to compare the data in a transversal way. As a consequence, the process determined the step by step of code prioritization and selection to validate the categories of the study, find emergent categories. With these codes, researchers could identify the concurrences and discrepancies in the categories of the analysis. This process corresponds to the second stage of processing and interpreting information and the contextual analysis. Finally, the emergent matrix of codification compiles the general analysis of each category, considering content and elements of the previous codes and validating them. The content of this final matrix is the source for the discussion and further recommendations. This last process corresponds to the third stage of interpreting information and metacontextual analysis according to an analytical method.

Results

This section presents and correlates the outcomes of the documentary analysis stages conducted through data processing matrices to address the inquiry: What are the characteristics of bilingualism promotion programs in the municipality of Tuluá, Valle del Cauca, between 2013-2021? The description of bilingual policies at the national, departmental and municipal levels is compared with local bilingualism strategies and learning outcomes in the saber 11 tests. To achieve the first objective of the research, it was necessary to explore digital databases and public libraries in Tuluá. A gap in studies related to bilingualism programs carried out in Tuluá was found from the enactment of the PNB in 2004 until 2013, when law 1651 of Bilingualism was enacted. Therefore, this study adopts the 2013-2021 timeframe.

Following the stages of the methodological design, the sample of documents selected for this research underwent an intratextual reading that allowed for deduction of the programs or actions under analysis. These are not only related to actions for the promotion of bilingualism in Tuluá, but also respond to the legal framework, ministerial quality references, analysis of results, among others. The actions developed by academic institutions and reported by the local government were carried out in official educational institutions from both urban and rural areas.

The information processing matrix was used for the selection of sources according to the mapping in the matrix and in-depth review of the selected sources. This instrument details the characteristics of the 25 actions prioritized in Tuluá for the promotion of bilingualism and allows, thanks to contextual reading, to achieve research objectives related to the descriptive phase of the study, as shown in

Table 1.

This research paper analyzed the strategies implemented in the city of Tuluá from 2013 to 2021. The results obtained through the literature review and interviews with key informants revealed that up to 16% of strategies were implemented per year from 2016 to 2021, with more than half of the strategies directed towards teacher qualification. Out of the total strategies, 20% are specifically related to student qualification. Additionally, 60% of the strategies have no information about their duration due to the low description of them in the source documents. These results suggest that the implementation of strategies in Tuluá has been adequate, although more information is needed to evaluate their effectiveness.

In the next stage (set of definitive documentary files), the review was carried out through metacontextual reading to arrive at the results with a sequence validated by the instruments detailed in the methodological route.

Table 1 shows the relationship between the actions (25) taken to promote bilingualism and the results of the Saber 11 tests. The ICFES classifies 5 levels of performance from A- to B+, including A1, A2 and B1. The CEFR recognizes levels A1, A2, B1, B2; however, in Colombia, level A- was added to include people who are below level A1 of the CEFR, whose performance is very basic in terms of structure and vocabulary; level B+ also includes people who have a level higher than B1. The score equivalence for each level is described below: A- from 0 to 47 points, A1 from 48 to 57 points, A2 from 58 to 67 points, B1 from 68 to 78 points, and B+ from 79 to 100 points.

Table 2.

Standardized test results (Saber 11).

Table 2.

Standardized test results (Saber 11).

| Country / Municipality |

Percentage of students by performance levels |

| A- |

A1 |

A2 |

B1 |

B+ |

| Colombia |

40% |

30% |

18% |

9% |

1% |

| Tuluá |

44% |

30% |

17% |

7% |

2% |

Considering the importance of analyzing information, the research process included a codification process made in the metacontextual analysis. The contrast matrix was used to process and contrast the information, which was documented in

Table 3. It contains the most important categories of the study with their respective codes based on the reading of the documents. After grouping the codes, new categories were generated, as seen in the third column. This column represents the general conception of the categories in the national and local context, which will be discussed further in light of the background.

Table 3 is initially divided into the main categories, which are the conception of bilingualism and bilingual educational policies. Likewise, from the theoretical sections, it was necessary to analyze these programs and strategies from the categories of teaching, methodology, learning, and evaluation since they are fundamental components from the documentation, planning and proposal of initiatives or policies. Emerging categories were included, which represent important findings in the contextual analysis of the programs. In the above table, the first column corresponds to the document number with the same numbering in the characterization table, thus it is easy to recognize those documents that share notions or characteristics in their implementation. The second column includes the definitions or sections that involve the categories previously defined from the theoretical foundation. The definitions contained therein correspond to the data extracted from the original documents. In the third column, codes are grouped together to determine the frequency with which any of the components are adopted or implemented in national bilingual policies. These codes are input for the complete codification process to be carried out in the contrastive matrix.

Summarizing, the documents submitted to content analysis are related not only to actions to promote bilingualism in Tuluá but also respond to legal frameworks, ministerial references of quality, analysis of results, among others. The actions developed by academic entities and informed by the Secretary of Education of Tuluá. As described above, all quality documents corresponding to national, departmental and municipal bilingualism programs implemented in Tuluá from 2013 to 2021 were analyzed.

Discussion

Having analyzed data according to the research question, objectives and methodology stages, four main categories emerged from this deductive analysis. These categories are: The notion of bilingualism in Colombia, Processes and characteristics of bilingual public policies and programs, Conception of English teaching, learning and evaluation in the bilingual programs and Promotion of bilingualism and results of the Saber 11° tests. These categories make it possible to respond to the research question: What are the characteristics of the bilingualism promotion programs in the municipality of Tuluá, Valle del Cauca, between 2013-2021? In this part of the article, the information of the mentioned categories and results will be supported in detail with theoretical background to present the discussion.

The first category that emerged from this analysis is the notion of bilingualism in Colombia. This category includes a discussion on how bilingualism is defined in Colombia and how it is related to national policies. The second category is Processes and characteristics of bilingual public policies and programs. This category includes a discussion on how these policies and programs are implemented in Tuluá. The third category is Conception of English teaching, learning and evaluation in the bilingual programs. This category includes a discussion on how English is taught, learned and evaluated in these programs. Finally, Promotion of bilingualism and results of the Saber 11° tests is the fourth category that emerged from this analysis. This category includes a discussion on how these programs promote bilingualism and what are their results.

The first category of this discussion is the notion of bilingualism in Colombia. This category is considered one of the main categories because it represents the definition and goal of bilingualism in Mineducación’s national linguistic and educational policies. It is also the basic notion that all institutions must consider when developing projects or strategies. As a result of the analysis, the general conception of bilingualism in Colombia is “Degrees of language proficiency to communicate in diverse contexts. Bilingualism includes skills in the use of foreign languages for competitiveness in the contemporary world. Bilingualism focused on English as a foreign language” (Mineducación, 2006, p.5). This means that learning English as a foreign language is socially considered as a tool to compete in labor and academic worlds.

The concept of bilingual education in each program is understood as the degree of mastery that people develop to communicate in English and thus use it to have better labor and academic conditions in their lives (Mineducación, 2006). This implies that the acquisition of an L2 has a direct impact on individual and collective development of human beings, both in terms of job opportunities and professional training, while there is an intercultural exchange (Oestreicher, 1974; Thiery, 1978).

The second category is titled Processes and characteristics of bilingual public policies and programs. From the emergent codes and data analysis, this is the general conception of educational public policies presented in

Table 5.

In the national context, educational policies represent the guidelines from which teaching strategies or pedagogical support are derived. They aim to facilitate the learning process of a new linguistic code and lead students and teachers to develop communicative competences, in accordance with national bilingualism objectives.

From a theoretical perspective, the purpose of a public policy proposal is the pursuit of the ideal of a society (Torres-Melo & Santander, 2013). It allows identifying the conflicts and needs of a community, achieving the purposes of the same, outlining guidelines, distributing resources and responsibilities to have a greater organization (Torres-Melo and Santander, 2013). Furthermore, the projection of programs and policies can be considered to propose strategies that generate the configuration of cooperation networks. These strategies can be used to promote the collective construction of social dynamics with the support of economic, academic, public and private sectors (Gómez, 2021). In addition, all this will allow efforts to be focused not only on the qualification of teachers and preparation of students to improve standardized test results but also to generate multi-sectoral strategies that can respond in a decentralized manner to problems of sectors involved in the process (Gómez, 2021; Hurtado, 2021). Linguistic planning corresponds to a set of actions carried out in order to optimize use of a second language in a given social group. These actions are implemented by individuals within an institutional framework guided in turn by corresponding public policies in order to develop “desired linguistic behavior” (Tovar, 1997).

The third category is called Perception of Educational Policy: English Teaching, Learning and Assessment in Bilingual Programs. It is directly related to linguistic policies. According to the general analysis of this category after reading the documents of the 25 programs analyzed, the planning process of bilingual strategies should involve teachers, students, assessment and the conditions or resources to implement them in the centers. This can be seen in

Table 5:

Innovative teaching methodologies are recommended, where students are active agents during the learning process. These methodologies seek that students develop skills from communication in English, problem solving, respect for each other and the ability to work in a team and community.

In addition, in some programs it is recommended the use of ICT mediation within the processes of teaching, learning and evaluation of English. Overall, the active and student-centered methodologies and teachers training with current tools to respond to the contextualized needs of their students is supported by De La Cruz y Jaramillo (2022).

In this fourth category related to

Table 3, according to the analysis of the results of Saber 11 tests contrasted with the implemented programs, there were better levels of performance in the results in 2016. This could be related to the emergent programs of Mineducación directed to English teaching, for example the Basic Learning Rights (2016). Among national programs are the PNB, CVW and Colombia Bilingüe. In

Table 3, the lowest score was in 2013, for which there were 3 strategies in operation. Already by 2014 an improvement is observed along with the implementation of two new strategies, among them the Colombia Bilingüe program of the Ministry of Education. By 2017, despite having 8 strategies in place, the result dropped 4 points. From 2018 to 2021 there are from one to two strategies in place and the average is still around 50 points. Also, a significant difference is evidenced in the results of private schools with respect to official schools in both Tuluá and Cali. Cali also reflects better results with respect to Tuluá, even surpassing the results at the national level.

Likewise, rural schools in Tuluá show lower performance throughout the measurement between 2013 and 2021, which denotes little relevance of national, regional and local language policies in this population. These low results and non-fulfillment of the bilingual goals were also found by Cardenas and Miranda (2014), Hurtado (2021) and Gómez (2021). These authors found that the Saber 11 results reveal the deficit in the English proficiency of students and the coordination of strategies as a weakness, which also hinders the fulfillment of the bilingual goals proposed in the national bilingual programs (Cardenas and Miranda, 2014; Hurtado, 2021; Gómez, 2021).

The aforementioned is shown on few studies which have been conducted for accounting the real situation of bilingualism in Tuluá. This has limited, for example, the access to the results of state tests such as Saber 11° and Saber Pro. Due to the scarcity of recorded actions, it is necessary to adequately systematize strategies or programs. These records will allow for follow-up and evaluation of bilingual programs. A database should be implemented by local academic authorities to allow for the reliable organization of information related to bilingualism and language policies in the locality.

In this manner, Tuluá has shown initiative and leadership in promoting bilingualism through organizations such as UCEVA, the Levapan Foundation, and the Municipal Education Secretariat. These organizations have increased organization and registration of strategies that are carried out. Additionally, there is inter-institutional synergy that can enhance the impact of programs or activities that will be implemented in the municipality to achieve learning objectives set for students.

This documentary review has allowed us to identify that there is little evidence of a previous diagnosis in the implementation of bilingual programs. This represents a weakness in determining the effectiveness of strategies and programs. In the absence of such diagnosis, weaknesses or opportunities that Tuluá had to respond to its needs in relation to bilingualism were not considered. For this reason, it is recommended that future planning and implementation of bilingual actions include a diagnostic and final evaluation process. This makes it possible to know the initial level of the population, design strategies focused on the needs of the context, and assess the evolution of learning during implementation. For further bilingual actions in Tuluá, it is crucial to strengthen or prioritize conditions according to the institutional or inter-institutional capacity of Tuluá in favor of bilingualism. This is only possible with an appropriate process of evaluation and monitoring.

Another important factor affecting students’ English proficiency is the qualification of teachers since elementary school. This phenomenon is a consequence of current educational policies and depends on the low supply of education professionals with a degree in languages. This has a direct impact on the low acquisition of linguistic competence by students. According to the results, the total number of strategies implemented from 2013 to 2021 reflects a conception of bilingualism that responds to the guidelines proposed by the Ministry of Education and the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR). English teachers also have guidelines and standards that guide the teaching process. However, Colombian hiring regulations allow professionals from different areas to work as English teachers; therefore, they do not have adequate didactic strategies for teaching this subject. Consequently, it is recommended that primary schools be provided with real English teachers for this subject or to train teachers in English proficiency and provide them with pedagogical books, didactic materials, technological resources, etc.

Finally, it is recommended to determine the purpose of bilingual education in Tuluá. It must be established according to the idea of responding to national objectives and implementing the teaching of a foreign language. Additionally, it must be considered an intercultural multilingual education that contemplates the transversality of English and different subjects. This approach proposes the formation and growth of conscious people capable of caring for, preserving, and solving problems in their environment while living with cultural and linguistic diversity. In conclusion, with this conception and educational approach, individuals can evolve and society can progress.

Funding

The research project “TULUÁ IN PURSUIT OF BILINGUALISM: ANALYSIS OF THE PROMOTION OF ENGLISH IN THE MUNICIPALITY (2013-2021), which led to the results presented in this manuscript, received funding from Unidad central del Valle del Cauca, Tuluá Colombia.

Conflict of Interest

The study reported in this article is part of a larger research project conducted by Adela Macías Molina, Angie Ruiz León, Carlos Mario Villada, Gonzalo Romero Martínez, Angelmiro Galindo Martínez, as master's thesis work, to contribute to the project "Políticas Públicas de Bilingüismo de Tuluá". The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. Unidad Central del Valle del Cauca sponsored this research. No other competing interest to disclose.

References

- Alonso, J.; Gallo, B.; Torres, G. (2012). Elementos para la construcción de una política pública de bilingüismo en el Valle del Cauca: un análisis descriptivo a partir del censo ampliado de 2005. Estudios Gerenciales, 28(125), 59-67. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa? 2122. [Google Scholar]

- Baena, G. (2017). Metodología de la investigación (3a. ed.). Grupo Editorial Patria.

- Bastidas, J.; Jiménez, J. (2021). La política lingüística educativa en Colombia: análisis de la literatura académica sobre el Plan Nacional de Bilingüismo. Retrieved from Fundación Dialnet: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo? 8008. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, A. (2020). Abordaje del bilingüismo en educación preescolar, básica y media desde los referentes del marco común europeo de referencia, /: Universitaria Juan N. Corpas. Centro Editorial. Ediciones FEDICOR. https.

- Bloomfield, L. (1933). Language.

- Byram, M.; Gribkova, B.; Starkey, H. (2002). Developing the intercultural dimension in language teaching: a practical introduction for teachers. /: policy division, directorate of school, out-of-school and higher education, Council of Europe. https, 1680. [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas, R.; Miranda, N. (2014). Implementación del Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo en Colombia: Un balance intermedio. /: 17, No. 1. pp. 51-67. https, 8343; 17. [Google Scholar]

- Correa, D.; González, A. (2016). English in public primary schools in Colombia: Achievements and challenges brought about by national language education policies. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 24, 83. [CrossRef]

- Decreto 3870 (2006). Gestor normativo. Función Pública. https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php? 2209.

- Decreto 4904. (2009). Función Pública. https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=38477#:~:text=por%20el%20cual%20se%20reglamenta,y%20se%20dictan%20otras%20disposiciones.

- Deslauriers, J. (2004). Investigación cualitativa, guía práctica. Traducción Miguel Ángel Gómez Mendoza, Doctorado en Ciencias de la Educación - Rudecolombia.

- De la Cruz, C.; Jaramillo, B. (2022). Sistematización de la experiencia: ser docente por un día, el estudiante como un agente de cambio. Unidad Central del Valle del Cauca - UCEVA.

- Galindo, A. (2012). Producción argumentativa escrita en lengua materna de estudiantes en formación universitaria bilingüe y tradicional en la Universidad del Quindío, Colombia. Retrieved from Forma y Función, vol. 25, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2012, pp. 115-137: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/219/21928398006.

- Gómez, M. (2021). Planificando la implementación de la Política pública de bilingüismo del Valle del Cauca. Biblioteca Digital Universidad del Valle. https://bibliotecadigital.univalle.edu. 4195. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera Moreno, L. (2018). La prueba saber 11o como instrumento para medir el nivel de inglés a partir de los criterios planteados en el programa Colombia bilingüe. Uniandes. https://repositorio.uniandes.edu. 6412. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Prados, M.; Galián, B.; Poveda, C. La didáctica del inglés. Revisión de programas sobre bilingüismo. Estudios. [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, J.F. (2021). Análisis documental de los planes sectoriales de educación en relación con la educación bilingüe (español-inglés) básica y media en Bogotá en el período del 2004 al 2020. Repositorio Universidad Pedagógica Nacional. http://repository.pedagogica.edu.co/handle/20.500. 1220. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.C. (2013). Language policy.

- Ley 1651 de 2013 - Gestor Normativo. (s. f.). Función Pública. https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php? 5377.

- Llano, R. (2022). Language Policy, Bilingualism, and the Role of the English Teacher: A Scientific Literature review from the Global dimension to the Colombian context. Revistas Udistrital. https://revistas.udistrital.edu.co/index. 1850. [Google Scholar]

- Lopera, J.; Ramírez, C.; Zuluaga, M.; Ortiz, J. (2010). El método analítico como método natural. https://bibliotecadigital.udea.edu. 1049. [Google Scholar]

- Macnamara, J. (1966). Bilingualism and primary education: A study of Irish experience. Edinburgh University Press, Issue 3.

- Macnamara, J. (1967). The bilingual’s linguistic performance, 23.

- Medina-Soto, A.; Vargas-Urrego, W.; Romero-Martínez, G. (2018). Dramatic Expression: A Strategy for the English Oral Production through the CLIL Approach. International Journal of Education and Learning Systems. 1299. [Google Scholar]

-

25. Ministerio de Educación Nacional (Mineducación). (2006). Política pública de bilingüismo, Santiago de Cali.

- 26. Ministerio de Educación Nacional. (Mineducación). (2014). Programa Nacional de Inglés 2015-2025.

-

27. Ministerio de Educación Nacional (Mineducación). (2016). Estándares Básicos de Competencias.

- 28. Ministerio de Educación Nacional (Mineducación). (2016). Lineamientos estándar de fortalecimiento del inglés.

- Oestreicher, J. (1974). The early teaching of a modern language, education and culture.

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas (ONU). (2019). Análisis conjunto de país SNU Colombia 2019. https://colombia.un. 1608.

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas (ONU). (2015). Objetivos de desarrollo sostenible. https://www.un.

- Osorio, M.; Cely, B.; Ortiz, M.; Benito, J.; Herrera, C.; Bernar, A.; Zuluaga, N. (2020) Tendencias en la formación de docentes de lenguas extranjeras y necesidades de los contextos educativos de educación básica y media en Colombia Fundación Universitaria Juan, N. Corpas. Centro Editorial. Ediciones FEDICOR. https://repositorio.juanncorpas.edu.

- Perlaza Torres, L.; Macias Molina, A.; Romero Martínez, G. (2021). Tecnologías del aprendizaje y el conocimiento en el aprendizaje integrado de contenido y lenguas extranjeras para el desarrollo de la competencia comunicativa intercultural. Revista Boletín Redipe. [CrossRef]

- 34. Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo. (2004-2019). Retrieved from, 1621.

- Quintana Aguilera, J.A.; Restrepo Castro, D.; Romero, G.; Cárdenas Messa, G.A. (2019). Efecto del Aprendizaje Integrado de Contenido y Lengua Extranjera en el desarrollo de habilidades de comprensión lectora en inglés. Lenguaje. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A. (1991) The McGill conference in honor of Wallace, E. Lambert. bilingualism, multiculturalism, and second language learning. Nipissing University College.

- Romero, G. (2017). Developing Reading Comprehension Skills in an ESP Course through a Theme and Task Based Learning Model. WSEAS Transactions on Advances in Engineering Education, /: Retrieved from http, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 38. The United Nations (UN). (2015). Sustainable Development Goals.

- 39. The United Nations (UN). (2018). Sustainable development goal 4, quality education. 2018.

- Thiery, C. (1978). True bilingualism and second-language learning.

- Tollefson, J.W. (2006) Critical theory in language policy En, T. Ricento (ed.) An Introduction to Language Policy: Theory and Method, pp. 42–59. Blackwell Publishing.

- Torres-Melo, J.; Santander, J. (2013). Introducción a las políticas públicas: Conceptos y herramientas desde la relación entre Estado y ciudadanía. IEMP Ediciones.

- Tovar, L. (1997). Planeación lingüística y contexto social. Lenguaje. 25.

- Truscott de Mejía, A.M.; Tejada, S.I. (2020). Teaching language is not enough: towards a recognition of intercultural sensitivity in bilingual teaching and learning, /: a la lingüística aplicada y el bilingüismo. Redipe. https.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).