1. Introduction

Chum salmon (

Oncorhynchus keta, hereafter referred to as ‘salmon’) is one of the six species (chum, coho, chinook, sockeye, pink, and cherry salmon) of salmonid fish that inhabit the North Pacific. All species of salmon are anadromous, i.e., they hatch in a river, migrate to the sea for growth, and then return to the river to spawn [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The early life stage of a salmon begins in a wild or artificial hatchery in freshwater. After growth, it moves to a brackish water environment and, when adapted to seawater, migrates seaward [

5,

6]. Therefore, salmon are euryhaline [

7]; they inhabit freshwater and seawater environments. However, the fertilized egg period is highly sensitive to environmental changes such as salinity, which can affect egg development and hatching [

8]. Fertilized eggs of Atlantic salmon (

Salmo salar) are adversely affected by osmotic pressure when exposed to saline water (0.5–5 psu) during the prehatching development stage [

9].

During the spawning migration, salmon move to the upper reaches of rivers to find the optimal spawning environment. For example, in the Skagit River (WA, USA), salmon travel more than 170 km upstream to spawn. In the Yukon River (AK, USA) and the Amur River (Russia), salmon move more than 2,500 km upstream before they reach their spawning grounds [

6]. Most salmon-spawning migrations in Korea occur in rivers on the eastern coast, which are short with steep slopes from the headwater to the river mouth [

10,

11]. In particular, the Namdae River is where most salmon in Korea migrate to spawn [

12]. The topographical characteristics limit the range of salmon distribution in these rivers to a narrow space (approximately 10 km in the case of the Namdae River) upstream from the estuary, and artificial structures such as weirs can also interrupt salmon movement to the upstream areas [

11]. Moreover, reduced winter precipitation results in low stream flow and water levels, restricting the area available for salmon migration. This leads to frequent exposure of fertilized eggs to the atmosphere after spawning [

13,

14,

15]. Because of these environmental factors, in the case of rivers located on the eastern coast of Korea, including the Namdae River (Yangyang), salmon spawning grounds are formed downstream [

11,

14], and seawater movements, such as high waves and tides, can cause environmental changes (e.g., salinity) in the lower reaches.

The recent significant increase in wave height along the eastern coast of Korea has caused wave overtopping [

16,

17]. The influx of seawater in the spawning ground can affect the survival (hatching) rate of salmon eggs. For example, the wave overtopping that occurred immediately after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami affected the lower reaches of rivers near the Pacific Ocean in Japan. The salinity of artificial spawning grounds in Iwate and Miyagi Prefectures rose to 14.5 psu, affecting salmon incubation and discharge rates [

8]. In addition, long-term sea level rise as a result of global warming can be a major cause of environmental change in the lower reaches of rivers and, as a result, can cause changes in the Namdae River’s resources that salmon use as spawning grounds.

This study hypothesized that changes in salinity in the lower reaches of the river owing to the influence of environmental changes, such as high waves, could affect the survival rate of salmon eggs. The purpose of this study was to understand how changes in river water salinity affect the development fertilized chum salmon eggs. To achieve this, we observed the survival rate of fertilized eggs before and after the eyed-egg stage exposed to various salinities. The experimental results indicate that fertilized eggs that have not yet reached the eyed stage are vulnerable to salinity. In the context of the spawning ground environment status of the Namdae River, this suggests that the sustainability of the chum salmon stocks is threatened.

2. Materials and Methods

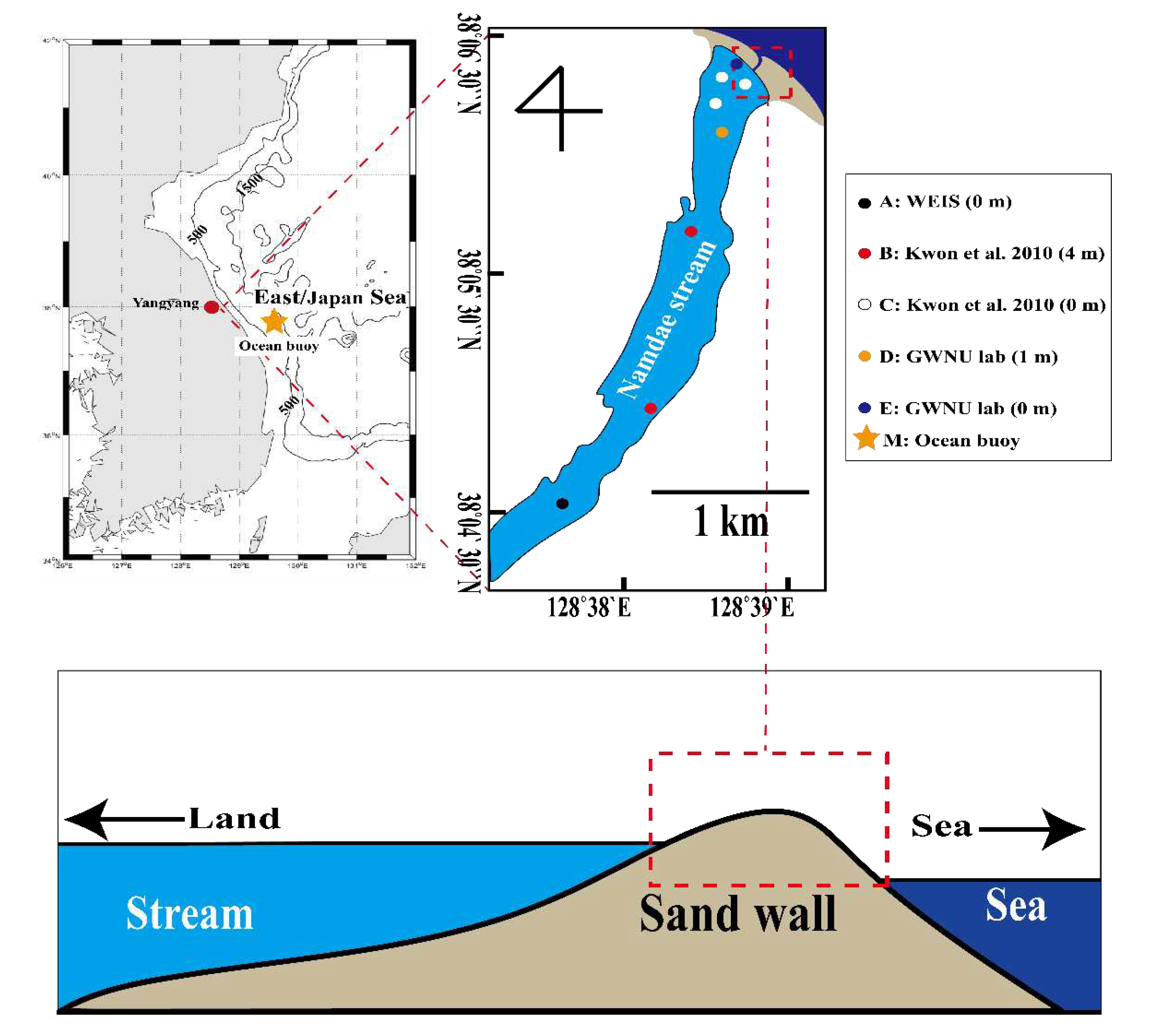

2.1. Salinity in Namdae River

Salinity data were provided by the Water Environment Information System (WEIS;

http://water.nier.go.kr/), Kwon et al. [

18], and the Gangneung Wonju National University Fisheries Oceanography Lab (hereafter referred to as

GWNU lab;

Figure 1). The salinity concentration from WEIS was measured monthly at the surface from 1997 to 2022 (excluding January 2001 and 2016). The data from Kwon et al. covered April to November 2008, excluding June and September [

18]. The data from the GWNU lab were collected at a depth of 1 m from June to December 2017 (excluding October and November) and October 2019 to April 2020, and at the surface in October and November 2017, and from October 2019 to April 2020.

2.2. Experiment design

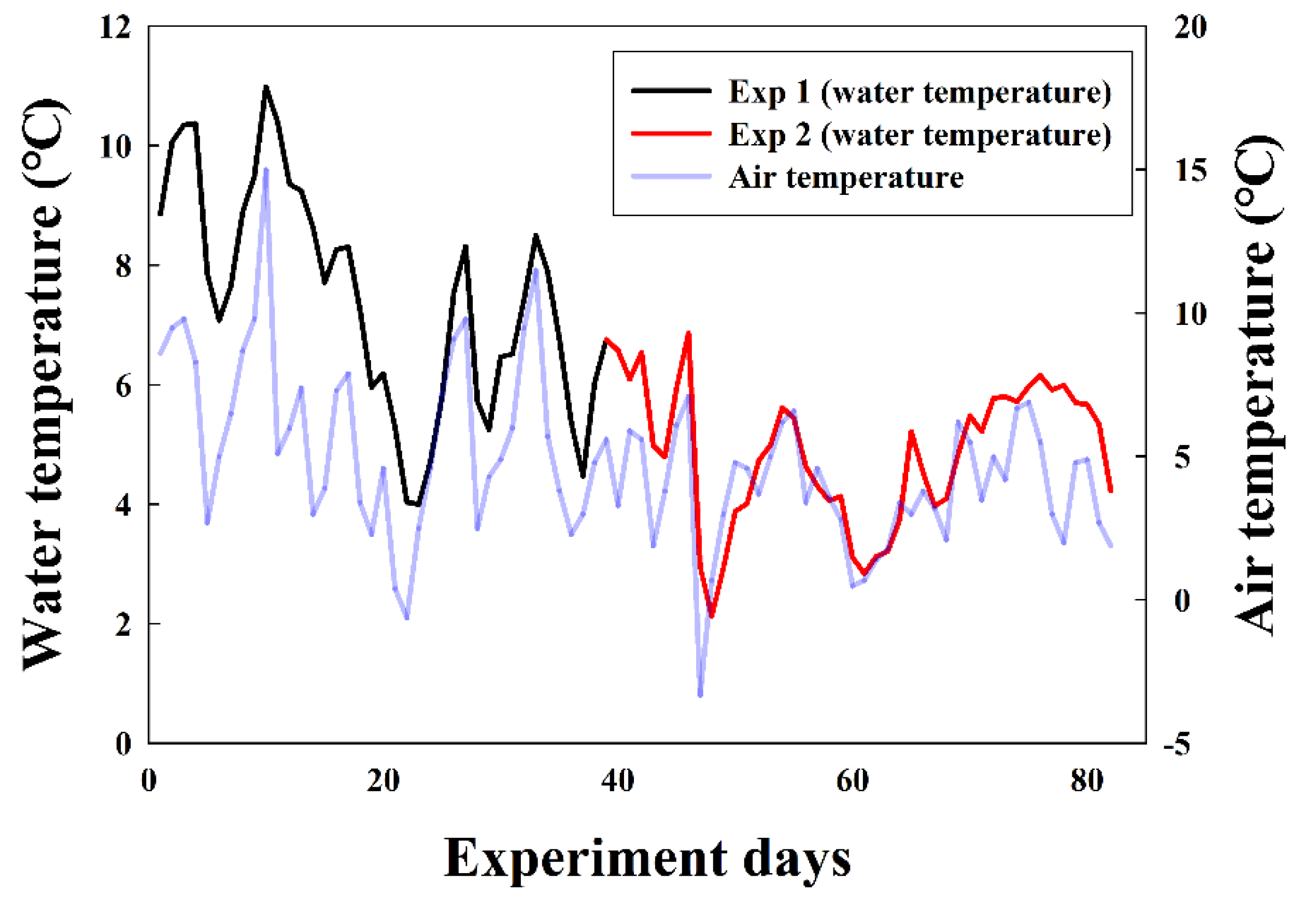

The Korea Fisheries Resources Agency provided artificially fertilized salmon eggs and the facilities to conduct the experiments (using Atkins hatchers). The experimental conditions involved controlling salinity using freshwater from the Namdae River, where salmon migrate for spawning, to create four environments (0, 1, 3, and 5 psu; salinities were created by adding salt to the river water). Supplemental water was periodically added to maintain the salinity concentration. During the experiment, the water temperature was not artificially controlled and was affected by changes in the atmospheric environment in the same manner as in the natural spawning grounds (

Figure 2). The water temperature in the experimental tanks during the experiment period ranged from 2.12 to 10.98 °C (x̅ = 6.06 °C).

Two experiments were performed based on the egg development process. This involved assessing, in response to various salinities, the rate of survival to the eyed-egg stage of < 1-day-old fertilized eggs (Exp 1) and the hatching rate of early eyed-eggs (Exp 2). Exp 1 was concluded when all eggs were at either the eyed-egg stage or dead, and Exp 2 was concluded when all eyed-eggs had hatched or were dead. For each experiment, 100 eggs were placed, and dead eggs (which are discoloured) were removed daily. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and during the experiments, the Atkins hatchers were covered with a mesh to prevent threats from predators such as rodents. During Exp 1 and Exp 2 the water temperature ranged from 3.99 to 10.98 °C (x̅ = 6.06 °C) and 2.12 to 6.85 °C (x̅ = 4.86 °C), respectively. The rate of survival to eye-egg stage and hatching rate are presented as a percentage.

2.3. Statistical analysis

We used IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (v. 28.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) for statistical analyses and conducted one-way ANOVAs to examine the relationship between salinity concentration and the survival rate to eyed-egg stage and hatching rate. When statistical significance was confirmed, we performed a post-hoc analysis using Tukey’s HSD.

Figure 2.

Water and air temperatures recorded during the experimental period. During Exp 1, the water temperature ranged from 3.99 to 10.98 °C (x̅ = 6.06 °C). In Exp 2, it ranged from 2.12 to 6.85 °C (x̅ = 4.86 °C). Water temperature data were provided by the Gangneung Wonju National University Fisheries Oceanography Lab. Air temperature data were provided by the Korea Meteorological Administration.

Figure 2.

Water and air temperatures recorded during the experimental period. During Exp 1, the water temperature ranged from 3.99 to 10.98 °C (x̅ = 6.06 °C). In Exp 2, it ranged from 2.12 to 6.85 °C (x̅ = 4.86 °C). Water temperature data were provided by the Gangneung Wonju National University Fisheries Oceanography Lab. Air temperature data were provided by the Korea Meteorological Administration.

3. Results

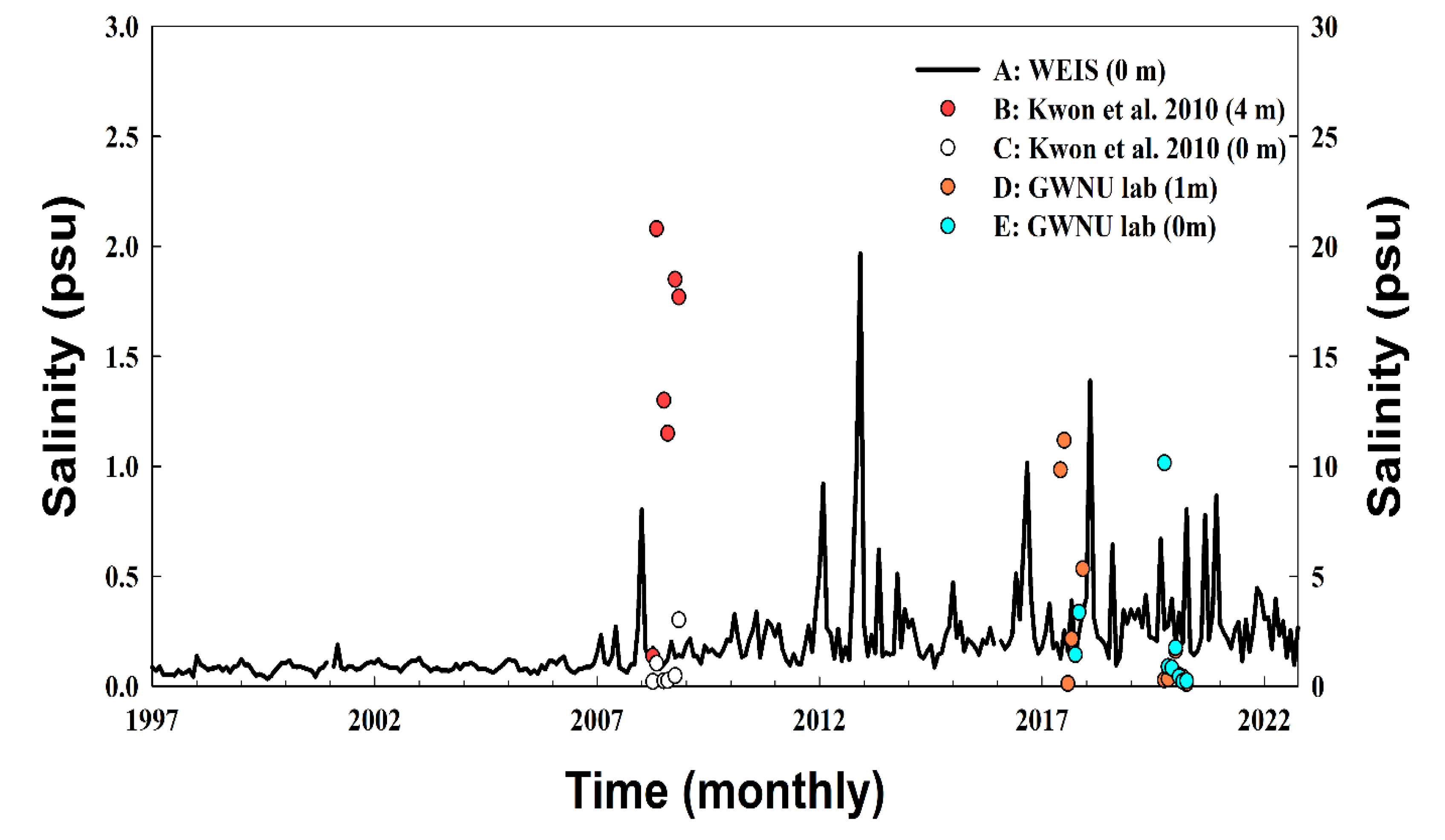

3.1. Changes in the salinity concentration of the Namdae River

During the experiment, the surface water salinity at station A, located approximately 3.6 km from the Namdae River estuary, ranged from 0.06 to 1.97 psu (x̅ = 0.26 psu). Salinity began to increase in late 2007 and peaked in 2012. At stations B, C, D, and E, salinity ranged from 1.36 to 20.08 psu (x̅ = 13.81 psu), 0.21 to 3.01 psu (x̅ = 0.87 psu), 0.11 to 11.17 psu (x̅ = 2.71 psu), and 0.21 to 10.14 psu (x̅ = 2.14 psu), respectively (

Figure 1 and

Figure 3).

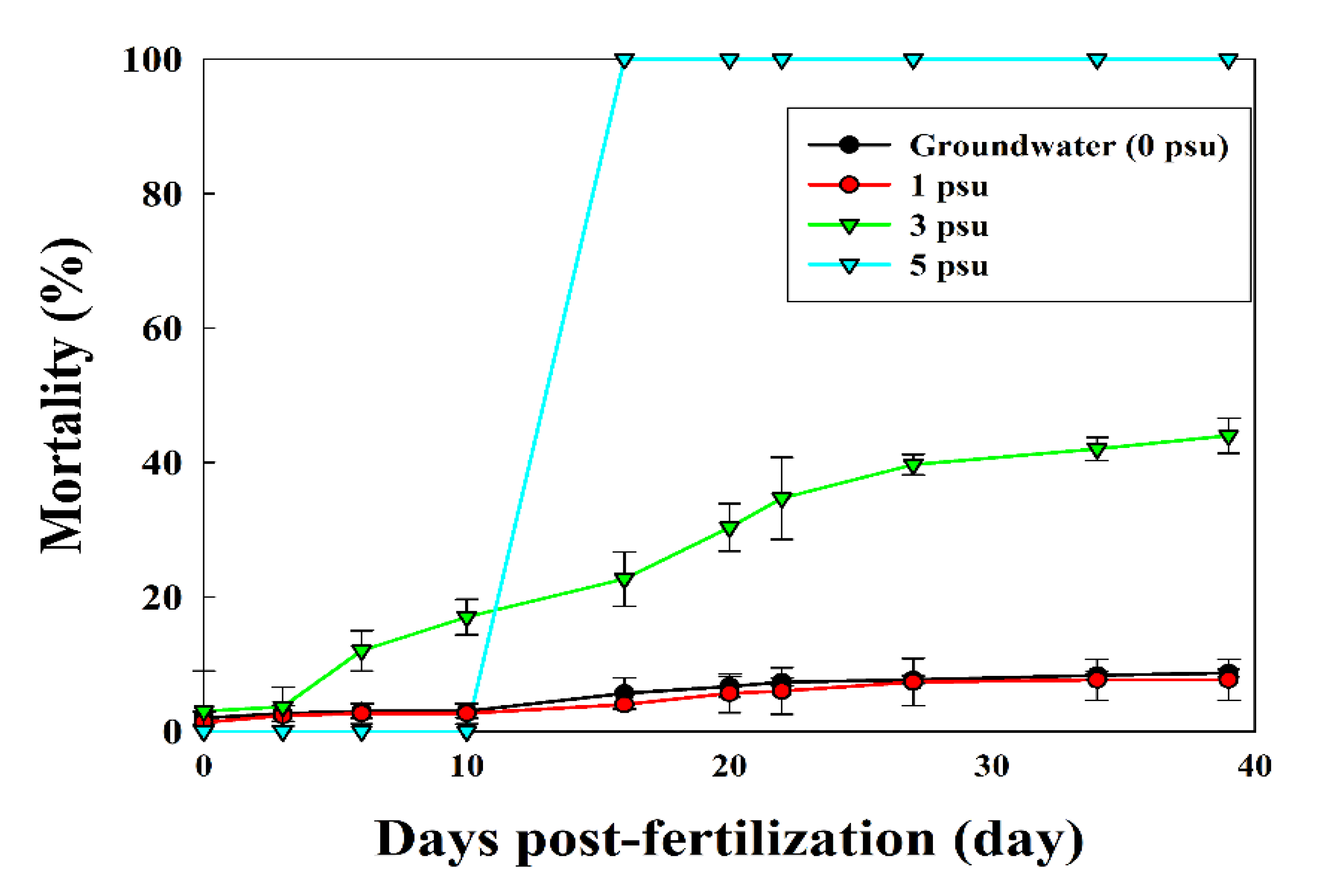

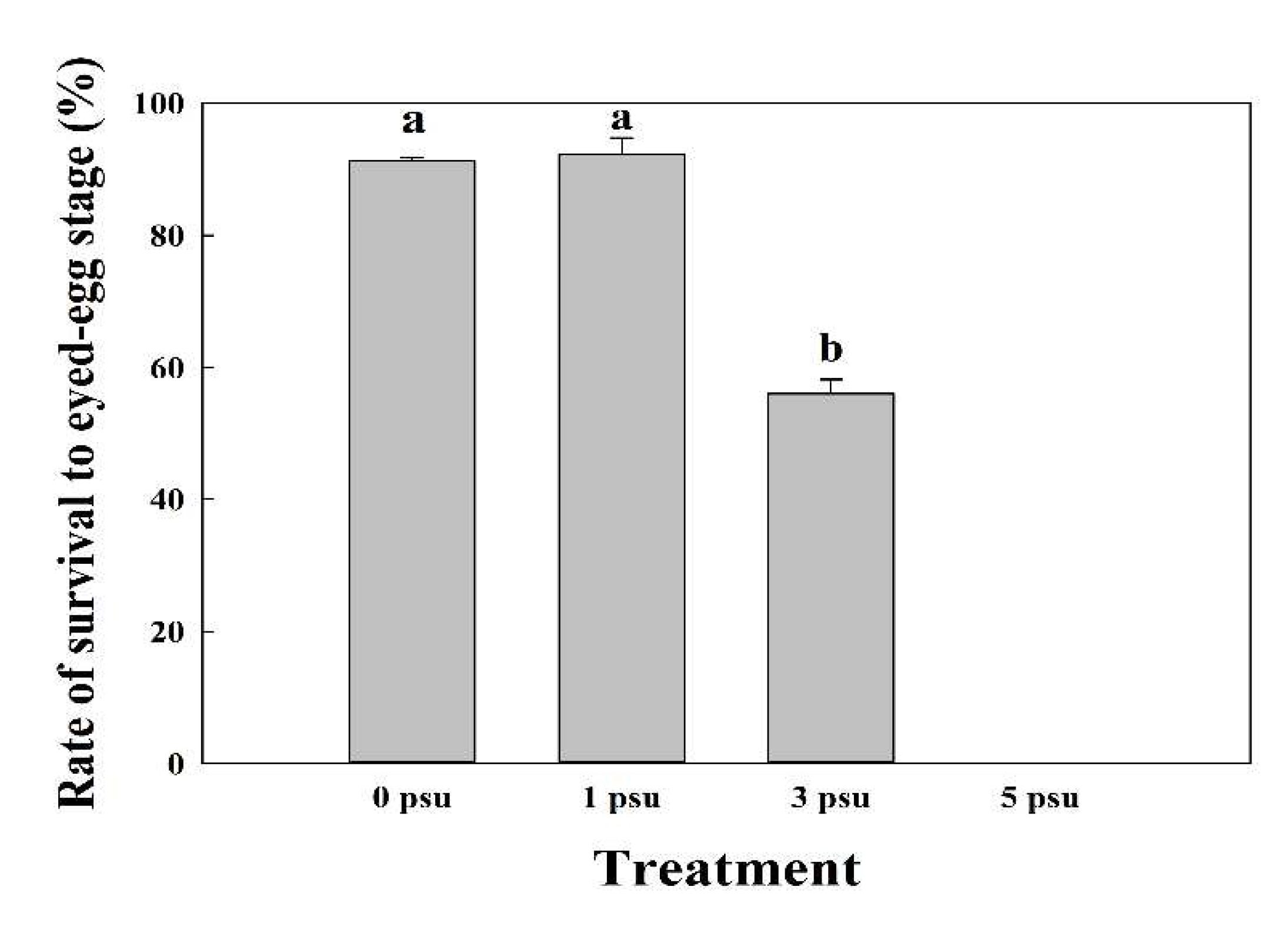

3.2. Effect of salinity on the rate of survival to the eyed-egg stage and hatching rate

The average (± SD) rate of survival to eyed-egg stage of the fertilized eggs in Exp 1 was 91.3 ± 0.47%, 92.3 ± 2.49%, and 56 ± 2.16% at 0, 1, and 3 psu, respectively. However, at 5 psu, all eggs died 10 d post-fertilization and did not develop into the eyed stage (

p < 0.05;

Figure 5).

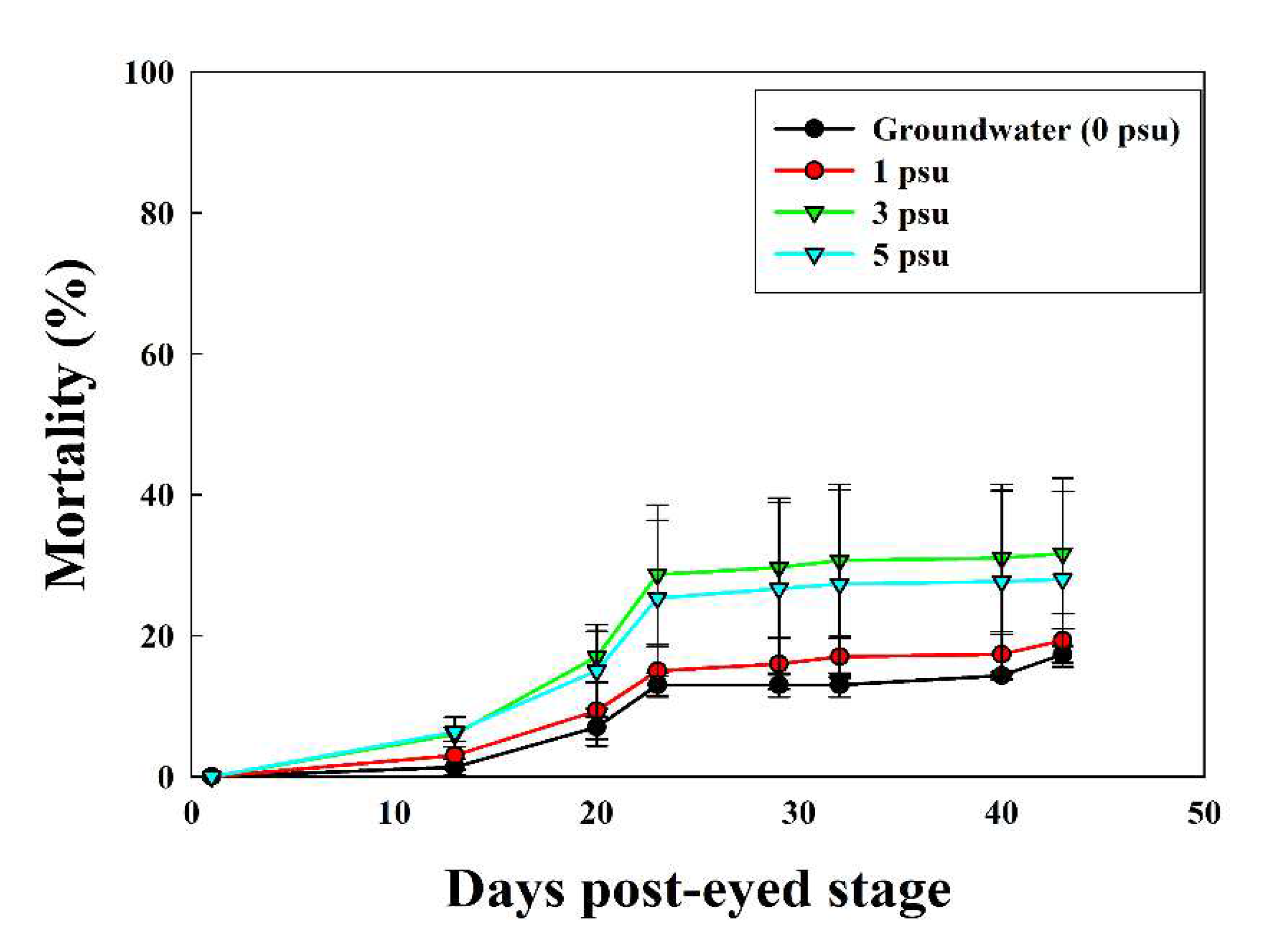

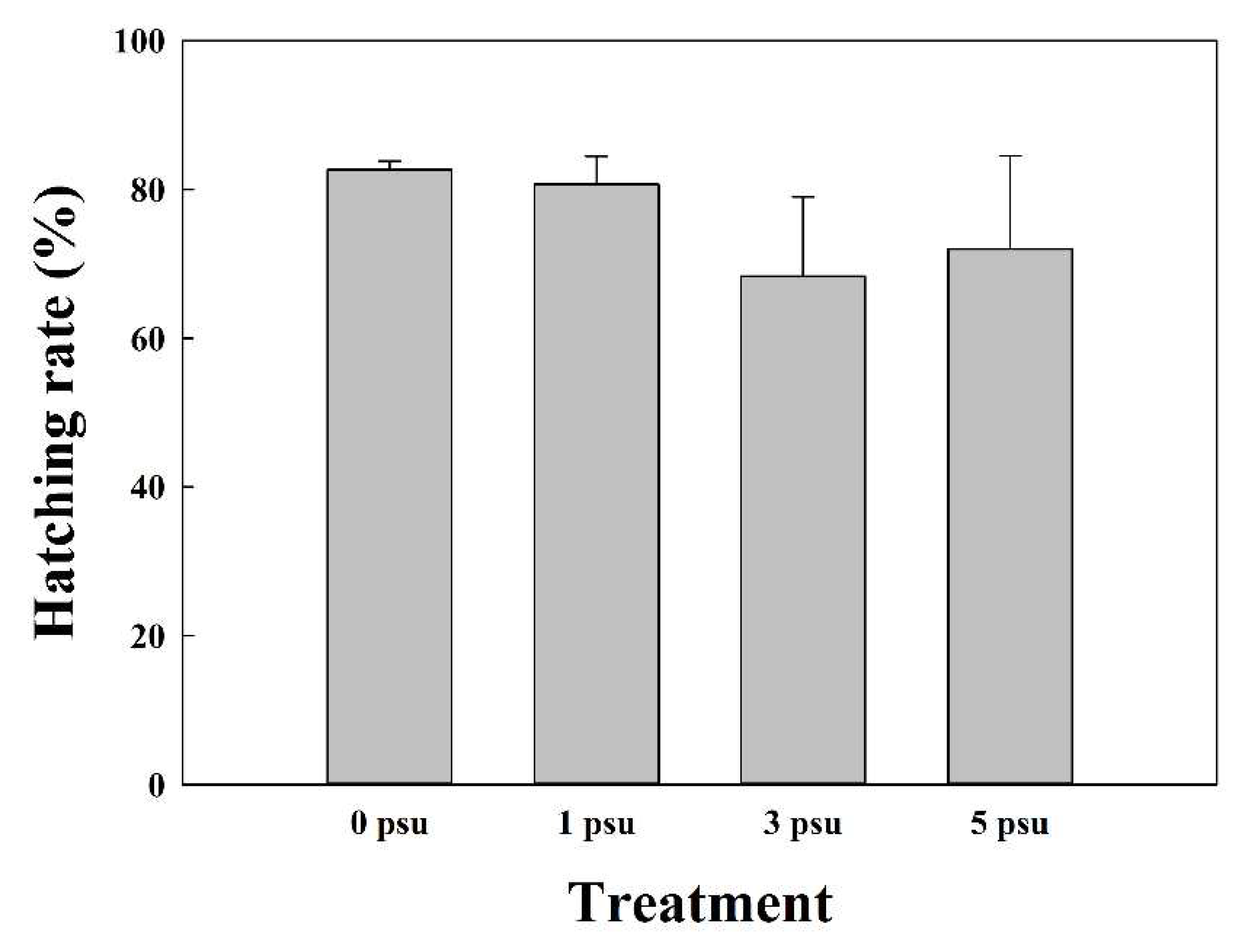

The average hatching rates of the eyed-egg stage in Exp 2 were 82.7 ± 1.15%, 80.7 ± 3.79%, 68.3 ± 10.69%, and 72.0 ± 12.49% at 0, 1, 3, and 5 psu, respectively (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). In Experiment 2, hatching rates differed depending on the salinity, but egg development progressed to the hatching stage at all salinities.

Figure 4.

Mean (± SD, n = 3) mortality rates of fertilized chum salmon eggs over 40 days under various salinity conditions.

Figure 4.

Mean (± SD, n = 3) mortality rates of fertilized chum salmon eggs over 40 days under various salinity conditions.

Figure 5.

Mean (± SD, n = 3) rate of survival of fertilized chum salmon eggs to the eyed-egg stage under various salinity conditions (p < 0.05). Alphabetic letters indicate significant differences between the treatment groups.

Figure 5.

Mean (± SD, n = 3) rate of survival of fertilized chum salmon eggs to the eyed-egg stage under various salinity conditions (p < 0.05). Alphabetic letters indicate significant differences between the treatment groups.

Figure 6.

Mean (± SD, n = 3) mortality rate of chum salmon eyed-eggs over 45 days under various salinity conditions.

Figure 6.

Mean (± SD, n = 3) mortality rate of chum salmon eyed-eggs over 45 days under various salinity conditions.

Figure 7.

Mean (± SD, n = 3) hatching rate of chum salmon eyed-eggs under various salinity conditions (p > 0.05).

Figure 7.

Mean (± SD, n = 3) hatching rate of chum salmon eyed-eggs under various salinity conditions (p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

Korea is the southern limit of salmon distribution in the North Pacific. The Namdae River, where the largest number of salmon migrate for spawning in Korea, passes through a small coastal city. In this river, saline water is distributed in the lower layers of the lower reaches because of the influence of domestic sewage and wave overtopping caused by high waves (

Figure 3). Salmon adapt to freshwater and seawater environments at each growth stage throughout their life cycle. Generally, during the spawning and hatching seasons, they spend their early life in the middle and upper reaches of the river, where they are unaffected by seawater.

In this study, the eyed-egg stage was more salinity-tolerant than the early fertilized egg stage (

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). This may result from the exposure to saline water before the chorionization of the egg envelope during development to the eyed-egg stage. Exposure to saline water in the early stage of fertilization can affect the hardening process by weakening the egg envelope and causing premature hatching [

19,

20]. Ban et al. exposed chum salmon eggs to various salinities (0, 0.5, 1, 2.1, 4.1, 8.3 psu) before and after fertilization at a water temperature of 10 °C. For eggs exposed before fertilization, the hatching rate was less than 2% when the salinity was 4.1 psu or higher. However, the hatching rate of eggs exposed after fertilization was more than 90% in all salinities [

8]. Similarly, in this study, 1-day-old fertilized eggs were directly influenced by salinity. However, the low hatching rate of eyed eggs associated with salinities above 3 psu in our study contrasts with the results of Ban et al. [

8] (

Figure 2). This may be associated with the effect of water temperature on hatching. The optimal hatching temperature of fertilized salmon eggs is between 8 and 10 °C [

8,

21,

22]. Ban et al. found that eggs exposed to freshwater (0 psu) between 7 and 13 °C had a very high hatching rate (approximately 90%) [

8]. The hatching rate was relatively lower, approximately 78% and 86% at 4 °C and 16 °C, respectively.

In this study, the eyed-eggs had a hatching rate of 70–80% under changing water temperature conditions. The hatching rate was likely influenced by the unstable environment during embryo development, as the eggs experienced the same fluctuations in water temperature as natural river water. Notably, the average water temperature during the experiment was less than 5 °C, indicating that the incubation rate was relatively low because it developed at a water temperature lower than the optimal incubation water temperature range.

Most early life stages of aquatic animals are highly vulnerable [

23] and are known to be sensitive to changes in the physical environment of their spawning grounds [

24]. Most salmon that migrate to the Namdae River in Korea cannot move to the upper reaches of the river and spawn in the middle or lower reaches [

14]. In particular, many salmon are prevented from accessing the middle or upper reaches of the river through the presence of weirs and catch nets installed for artificial seedling production. Similarly, anadromous river herring (alewives [

Alosa pseudoharengus] and blueback herring [

Alosa aestivalis]), which inhabit the Lamprey and Oyster rivers in New Hampshire (USA), usually spawn in the upper reaches of these rivers. However, dam construction has led to the destruction of spawning grounds, eventually resulting in a decrease in the resource volume [

25].

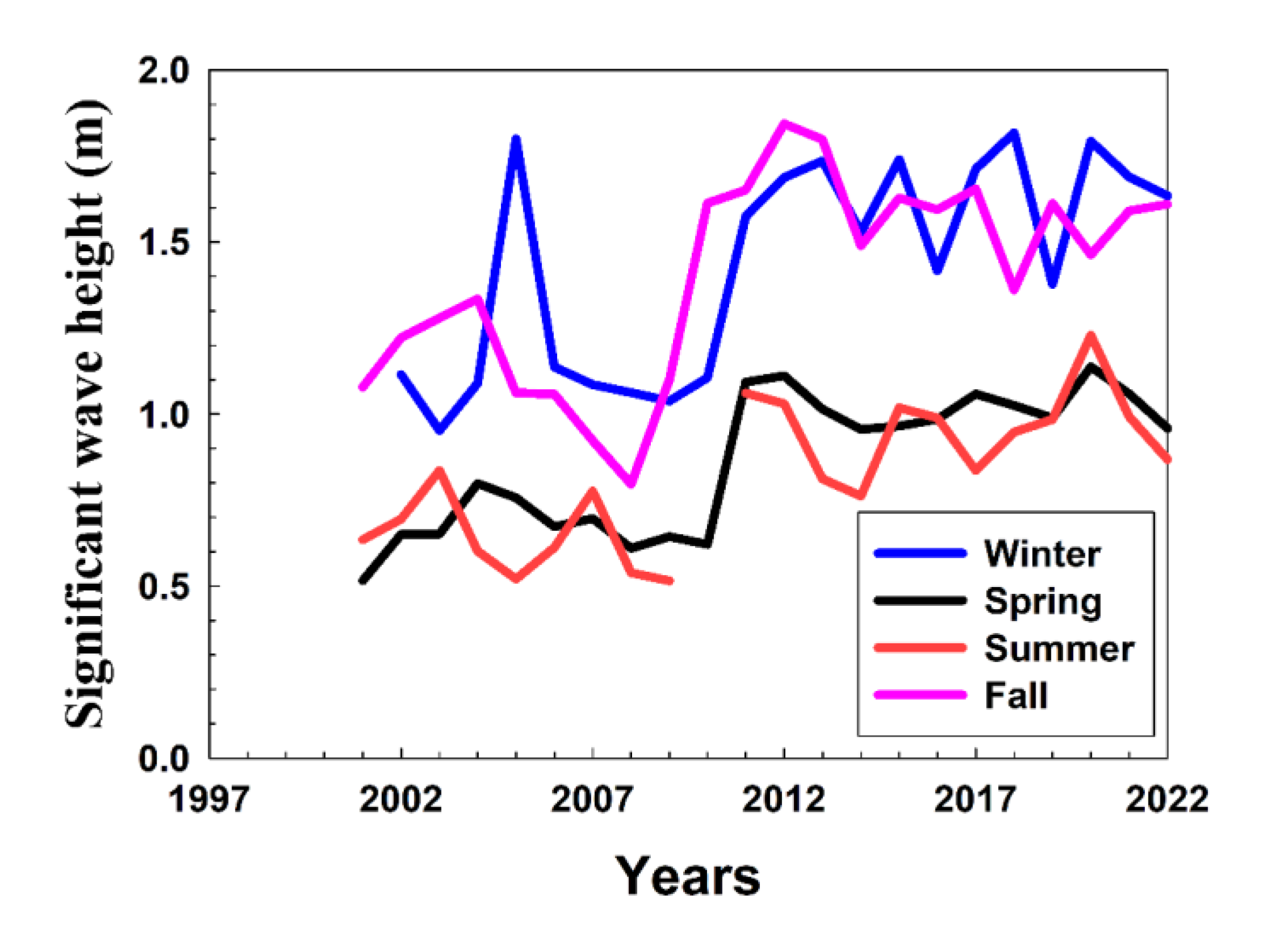

During the experimental period, many dead eggs were observed in the lower reaches of the Namdae River (between stations A and B;

Figure 1). This phenomenon is related to the experimental findings of this study. Owing to the geographical characteristics of the lower Namdae River, when seawater flows in, it tends to remain in the lower layer of the river for a long time because it is denser than the freshwater (

Figure 1 and

Figure 3). The high salinity in the lower reaches of the Namdae River has appeared continuously since 2012. It is considered to be related to the recent trend of increasing significant waves along the eastern coast of Korea during winter [

16] (

Figure A1). In addition, sea levels along the eastern coast of Korea are expected to rise by approximately 0.58 cm/year from 2005 to 2040 [

26], and the frequency of high waves is simultaneously increasing [

16,

17]. These phenomena are significant causes of frequent wave overtopping and the consequent changes in the salinity of rivers.

This study found that exposure of fertilized salmon eggs to saline water in the pre-eyed stage negatively affected survival and hatching rates. The gradual increase in salinity in the lower reaches of the Namdae River is expected to affect not only the survival rate of salmon in early life but also change salmon stocks in the long run.

This study investigated the effects of salinity on eggs immediately after fertilization and at the eyed stage. However, it is necessary to continuously monitor changes as the hatched larvae grow in this environment. For example, exposure to saline water during egg development can also impact survival and growth after hatching [

8]. Additionally, Korea continues to experience severe drought in winter, and these environmental changes result in a decrease in the flow rate and water levels, increasing the likelihood of spawning areas forming in the lower reaches of rivers.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we analyzed the effect of salinity on the survival rate of fertilized eggs and found that the stage before eyed eggs was vulnerable to salinity. Due to anthropogenic environmental factors, the spawning grounds of the Namdae River have gradually moved to the lower reaches of the river, where high-salinity water is distributed. This phenomenon is expected to undermine spawning and hatching capabilities and impact the sustainability of salmon stocks. The results of this study could contribute to the establishment of an environmental management plan for the sustainability of salmon resources and changes in salmon resource abundance influenced by precipitation patterns, water temperature, and the increasing frequency of high waves due to climate change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J. W. P. and C. I. L.; methodology, J. W. P. and C. I. L.; validation, C. I. L.; formal analysis, J. W. P. and H. J. P.; investigation, B. S. K.; resources, J. K. K.; data curation, J. W. P.; writing—original draft preparation, J. W. P. and C. I. L.; writing—review and editing, H. K. J.; visualization, J. W. P.; supervision, C. I. L.; project administration, C. I. L.; funding acquisition, C. I. L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Korea Institute of Marine Science and Technology Promotion, funded by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (20220214, 20220558), and the National Institute of Fisheries Science, Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, Korea (R2024008).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Seasonal change in significant wave height measured at the ocean buoy near the Namdae River mouth (orange-colored star in

Figure 1). Ocean buoy data was provided by the Korea Meteorological Administration (

https://data.kma.go.kr/cmmn/main.do).

Figure A1.

Seasonal change in significant wave height measured at the ocean buoy near the Namdae River mouth (orange-colored star in

Figure 1). Ocean buoy data was provided by the Korea Meteorological Administration (

https://data.kma.go.kr/cmmn/main.do).

References

- Dittman, A.; Quinn, T. Homing in pacific salmon: mechanisms and ecological basis. J. Exp. Biol. 1996, 199, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amberson, S.; K. Biedenweg, J. James.; P. Christie. “The heartbeat of our people”: identifying and measuring how salmon influences Quinault tribal well-being. Society and Natural Resources 2016, 29, 1389–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. A.; Kang, S. K.; Seo, H. J.; Kim, E. J.; Kang, M. H. Climate variability and chum salmon production in the North Pacific. The Sea 2007, 12, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H. S.; Seong, K. B.; Lee, C. H. History and status of the chum salmon enhancement program in Korea. The Sea 2007, 12, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Salo, E. O. Life history of chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta). In Pacific Salmon Life Histories; Groot, C.; Margolis, L., Eds. UBC Press: Vancouver, Canada, 1991; pp. 231–309.

- Johnson, O. W.; Grant, W. S.; Kope, R. G.; Neely, K.; Waknitz, F. W.; Waples, R. S. Status review of chum salmon from Washington, Oregon, and California. U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-32, 1997.

- Lee, H. J.; Lee, S. Y.; Kim, Y. K. Molecular characterization of transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) gene transcript variant mRNA of chum salmon Oncorhynchus keta in response to salinity or temperature changes. Gene 2021 795, 145779. [CrossRef]

- Ban, M.; Itou, H.; Nakashima, A.; Sada, I.; Toda, S.; Kagaya, M.; Hirama, Y. The effects of temperature and salinity of hatchery water on early development of chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta). Aquaculture 2022, 549, 737738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jenssen, E.; Fyhn, H.J. Effects of salinity on egg swelling in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Aquaculture 1989, 76, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S. O.; Hwang, S. I. Mechanism of the Marine Terraces Formation on the Southeastern Coast in Korea. Journal of the Korean Geographical Society 2000, 35(1), 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B. S.; Jung, Y. W.; Jung, H. K.; Park, J. M.; Lee, C. I. Behavior Patterns during Upstream Migration of Chum Salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) in the Lower Reaches of Yeon-gok Stream in Eastern Korea. J. Environ. Sci. Int. 2020, 29, 885–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Joo, G. J.; Jung, E.; Gim, J. S.; Seong, K. B.; Kim, D. H.; Lineman, M. J. M.; Kim, H. W.; Jo, H. The spatial distribution and morphological characteristics of Chum Salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) in South Korea. Fishes 2022, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, H. I.; Rose, K. A. Designing optimal flow patterns for fall chinook salmon in a Central Valley, California, River. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2003, 23, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B. S.; Jung, Y. W.; Kim, W. B.; Hong, S.E.; Lee, C. I. Distribution and Behavioral Characteristics of Chum Salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) in Namdae River, Korea. J. Environ. Sci. Int. 2022, 31(10), 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, M.; Dunbar, M. J.; Smith, C. River flow as a determinant of salmonid distribution and abundance: a review. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2015, 98, 1695–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. H.; Jang, C. J.; Do, K. D.; Jung, H. S.; Yoo, J. S. Linear trend of significant wave height in the East Sea inferred from wave hindcast. J. Coast. Disaster Prev. 2019, 6, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, T. S.; Park, J. J.; Eum, H. S. Wave Tendency Analysis on the Coastal Waters of Korea Using Wave Hind-Casting Modelling. J. Korean Soc. Mar. Environ. Saf. 2016, 22, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K. Y.; Lee, Y. H.; Shim, J. M.; Lee, P. Y. Occurrence and variation of oxygen deficient water mass in the Namdae River estuary, Yangyang, Korea. The Sea 2010, 15, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Luberda, Z.; Strzezek, J.; Luczynski, M.; Naesje, T.F. Catalytic properties of hatching enzyme of several salmonid species. Arch. Hydrobiol. 1994, 131, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luczyński, M.; Kolman, R. Hatching of Coregonus albula and C. lavaretus embryos at different stage of development. Environ. Biol. Fish 1987, 19, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beacham, T.D.; Murray, C.B. Effect of Female Size, Egg Size, and Water Temperature on Developmental Biology of Chum Salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) from the Nitinat River, British Columbia. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1985, 42, 1755–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C. B.; McPhail, J. D. Effect of incubation temperature on the development of five species of Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus) embryos and alevins. Can. J. Zool. 1988, 66, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepin, P. Effect of temperature and size on development, mortality, and survival rates of the pelagic early life history stages of marine fish. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1991, 48, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pörtner, H. O.; Peck, M. A. Climate change effects on fishes and fisheries: towards a cause-and-effect understanding. J. Fish Biol. 2010, 77, 1745–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiMaggio, M. A.; Breton, T. S.; Kenter, L. W.; Diessner, C. G.; Burgess, A. I.; Berlinsky, D. L. The effects of elevated salinity on river herring embryo and larval survival. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2016, 99, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y. K.; Jung, B. S.; Kim, R. H. Flood risk assessment for coastal cities considering sea level rise due to climate change. J. Korean Soc. Hazard Mitig. 2020, 20, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).