1. Introduction

Hayflick and Moorhead first used the term “cellular senescence” to describe how human somatic cells gradually lose their ability to proliferate. [

1]. Along with the loss of the capacity to replicate, this condition also exhibits a variety of important modifications in cell structure, gene expression, metabοlism, epigenetics, and other areas[

2]. The knowledge of how telomeres can signal senescence arrest has come a long way since then. These mechanisms are particularly crucial in the study of aging since it has been established that cellular senescence, which is fueled by telomere disruption, is a primary cause of aging and age-related disease[

2].

Telomeres are DNA tandem repeats (TTAGGG) linked to a variety of proteins that together make up the “Shelterin” complex. At the end of linear chromosomes, a ribonucleoprotein called telomerase repeats, elongating the telomeric TTAGGG. The core holoenzyme of this multi-subunit ribonucleoprotein enzyme only consists of catalytic telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) and an RNA template (TERC) [

1,

2,

3]. Telomerase silencing occurs because TERC is widely expressed while the TERT gene is strongly repressed in the majority of human somatic cells [

1,

2]. Hence, the factor that sets a rate limit for telomerase activity regulation is TERT. Telomeres have a 3′ overhang made up of single-stranded nucleotide repeats, as well as a lagging strand that is high in cytocine and a leading strand that is high in guanine [

3].

DNA breaks into single and double strands when the OS is high. Due to their higher guanine content and increased vulnerability to oxidative damage, telomeres also shorten more quickly as a result of it. The majority of somatic cells lack the telomerase enzyme, which results in a condition known as the “end-replication problem” during cell division. This is due to DNA polymerases’ innate inability to completely duplicate the lagging strand with a high concentration of telomere C[

4]. By allowing DNA polymerases to start DNA replication, RNA primers contribute to the synthesis of the lagging strand. However, when the final primer at the 3′ end is deleted, telomere repeats are lost and unavoidably, the recently formed strand will be a few nucleotides shorter[

4].

It has been determined that the telomere length (TL) in human spermatozoa is roughly 6–20 kb, longer than that in somatic cells[

5,

6,

7]. Additionally, it appears that the telomeres in spermatozoa are organized in a particular way, with the telοmeric sections of chrοmatin being either at the nuclear membrane or at the nuclear periphery. Since the oocyte may more easily access these sites for pronuclear growth after fertilization, it has been postulated that the placement of histοne-bοund telomeres close to the nuclear border and their combination have a functional effect[

5,

8].

Histones are not completely removed from the cell during the repackaging process; in human sperm, 10-15% of them are still present[

9,

10,

11], compared to only 1-2% in rat sperm[

11,

12]. Round spermatids demonstrate that fully developed sperm still have dimeric telomeres, in contrast to earlier germ cells, which have little or no telomerase activity[

13]. Germ cells experience substantial chromatin repackaging during spermiogenesis and epididymal transit. A tight toroidal conformation is formed by the gradual replacement of the majority of histone-bound nucleosomes by transition proteins and then protamines[

14].

In cοntrast to the germline, where telomeres have generally been thought to stay constant within a species, higher animal somatic tissues have been shown to experience telomere shortening with age. A sign of youth and biological fitness has been thought to be longer telomeres in an individual’s somatic tissues compared to other members of the same species. It was therefore surprising when several laboratories discovered that the sperm of older men had longer telomeres, which resulted in their children having leukocytes with higher TL.

It was rapidly hypothesized that the contradictory events must be brought on by biological processes that take place in the testes during a man’s lifetime. According to some, spermatozoa with long telomeres may have been selected for aging, whereas some hypothesized that telomere elongation takes place in the aging testes[

6,

15]. However, a bizarre hypothesis that old men’s gonads regenerate has come to dominate thought among peers in the field. A pioneering investigation that was published in short stated that different mechanisms, rather than a variation in the timing of telomere regulation, are the cause of longer TLs in spermatozoa from older men [

16].

Telomeres, the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes, play a major role in cellular aging and senescence, in contrast to BMI, which is commonly used as a measure of general health and obesity. Mitochondrial DNA is essential for the cellular synthesis of energy and has implications for age-related disorders. This study aims to advance knowledge of the molecular mechanisms underlying aging and the possible effects of lifestyle and metabolic factors on cellular health by exploring the interactions between these three variables.

2. Results

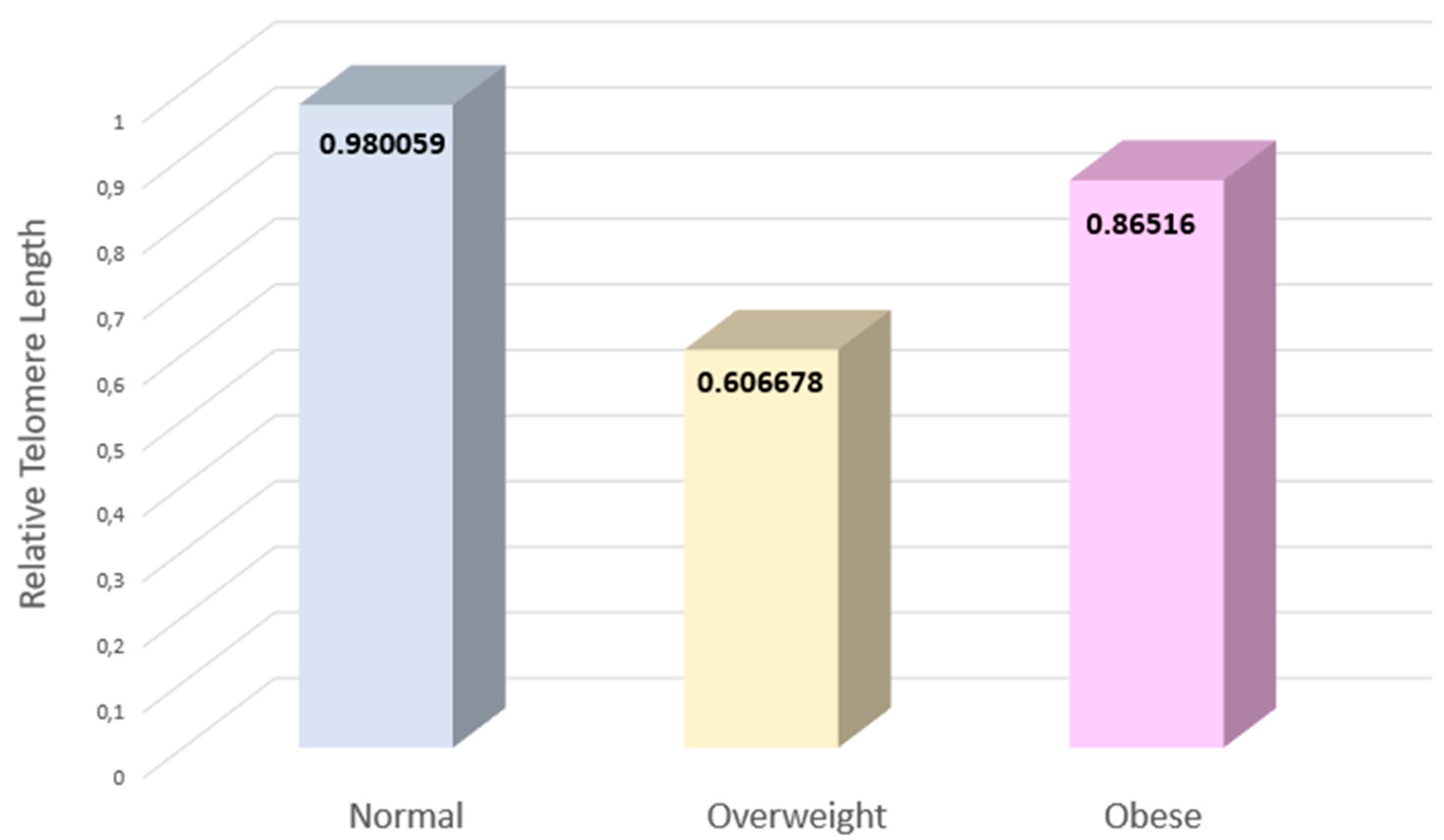

The individuals were divided into three groups according to their BMI. The mean values for relative telomere length are displayed in the graph below (

Figure 1). Based on the differences in standard deviations across the three groups, error bars have been defined.

The overweight group’s TL differs by almost half from that of the groups with normal and obese BMIs, respectively. Yet, this difference is not significant in terms of statistics (p>0.05). While the obese group’s variance ranges from -2 to 3, the normal group’s relative TL fluctuates between -2 and 4. However, the relative TL ranges between -1 and 2 in the group of people who are overweight (

Figure 1).

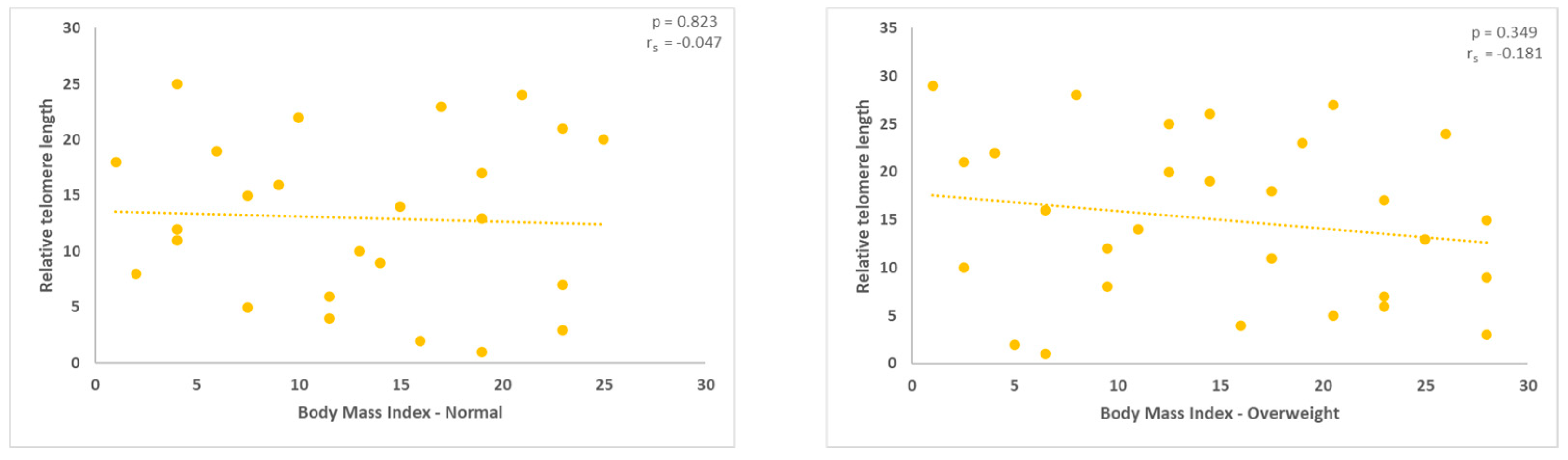

Following that, in each group separately, we examined the interaction regarding relative telomere length (TL). For the three groups with normal, overweight, and obese BMI, the relative length of telomeres was examined, as shown in the figures below. A substantial negative association between telomere length (TL) and the group of people with normal BMI (

Figure 2).

A negative association between BMI and relative TL was also observed in the overweight group, as indicated in the following graph (

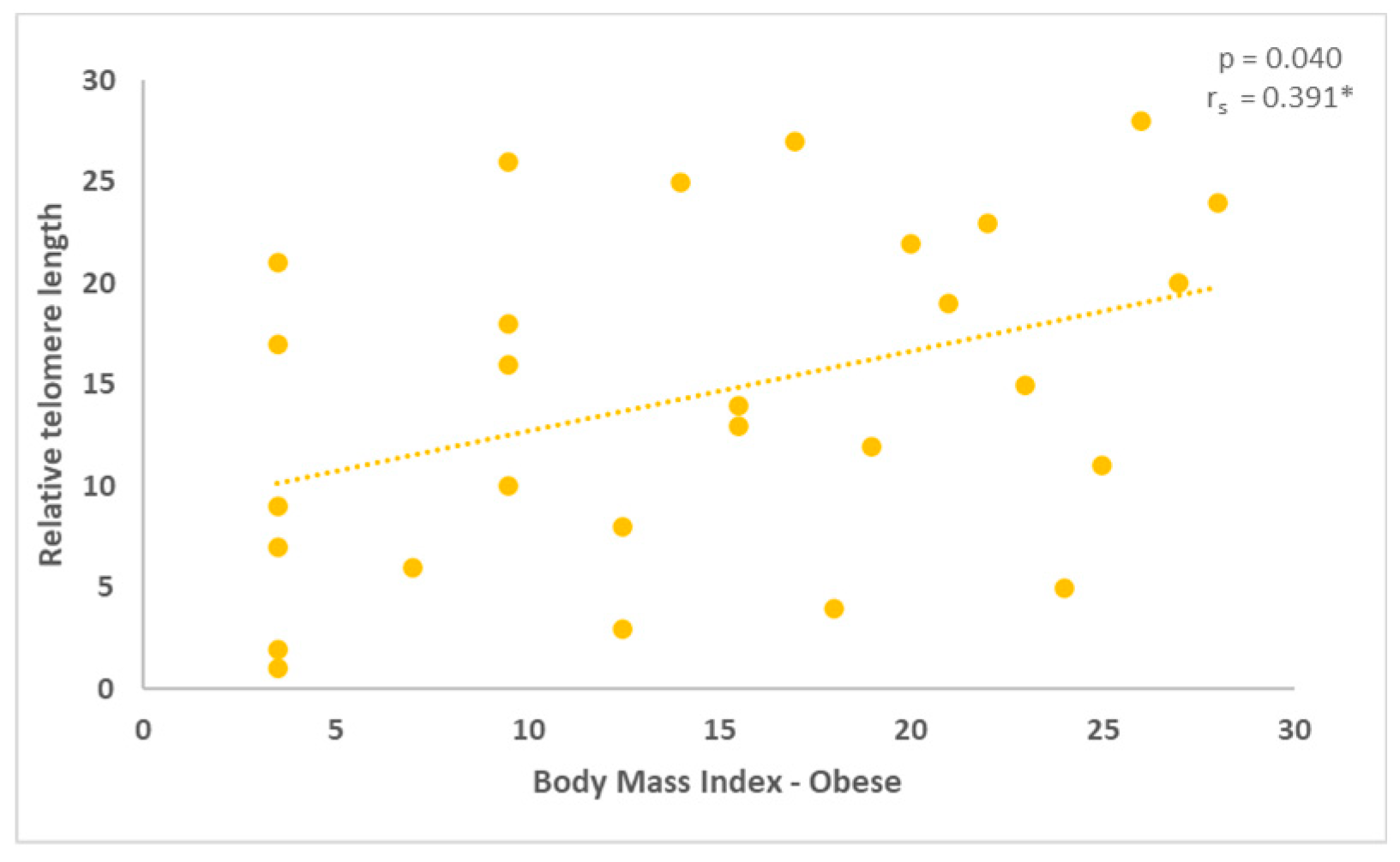

Figure 3). Finally, relative TL demonstrated a positive correlation with BMI in the obese group (

Figure 4). The figures below depict the result of Spearman’s correlation coefficient conducted to examine the relationship between relative TL and BMI.

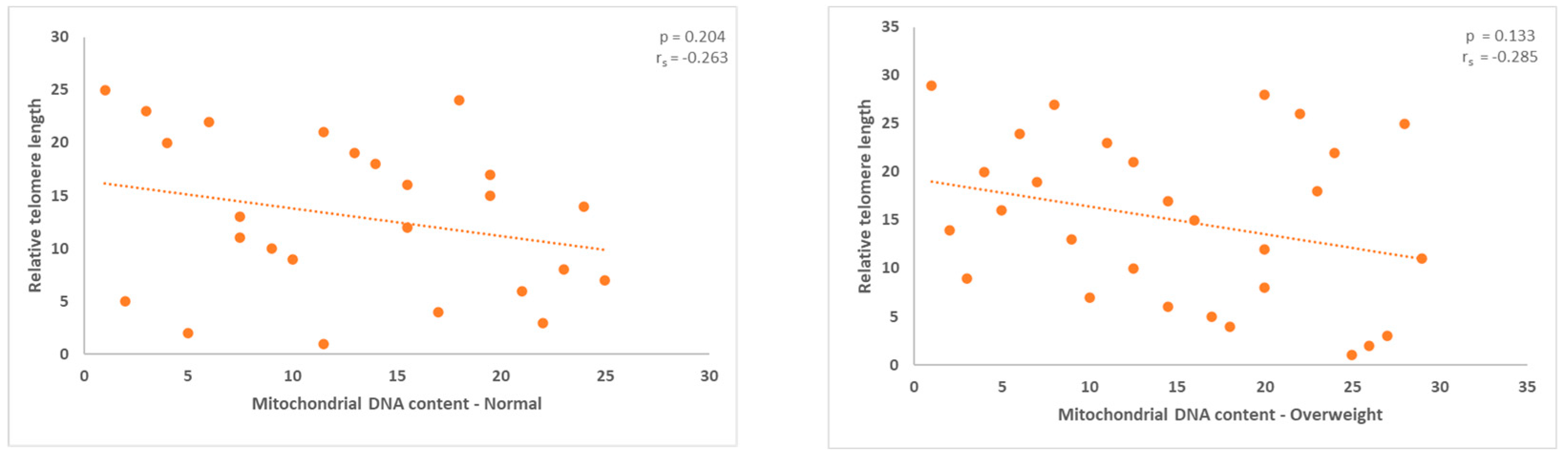

2.1. Correlation between mitochondrial DNA content and the relative telomere length

Additionally, the normal and overweight groups’ correlations between mitochondrial content and TL revealed a negative association. The results, which are shown in the figures below, are not statistically significant, as indicated by the p-values. The p-value for the normal group was 0.204 (

Figure 5), while it was 0.183 for the overweight group (

Figure 6).

The comparison of mitochondrial content and relative telomere length for males who range into the obese category showed a positive connection. The graph below reflects this further (

Figure 7). The outcome in this instance was statistically significant, p=0.812.

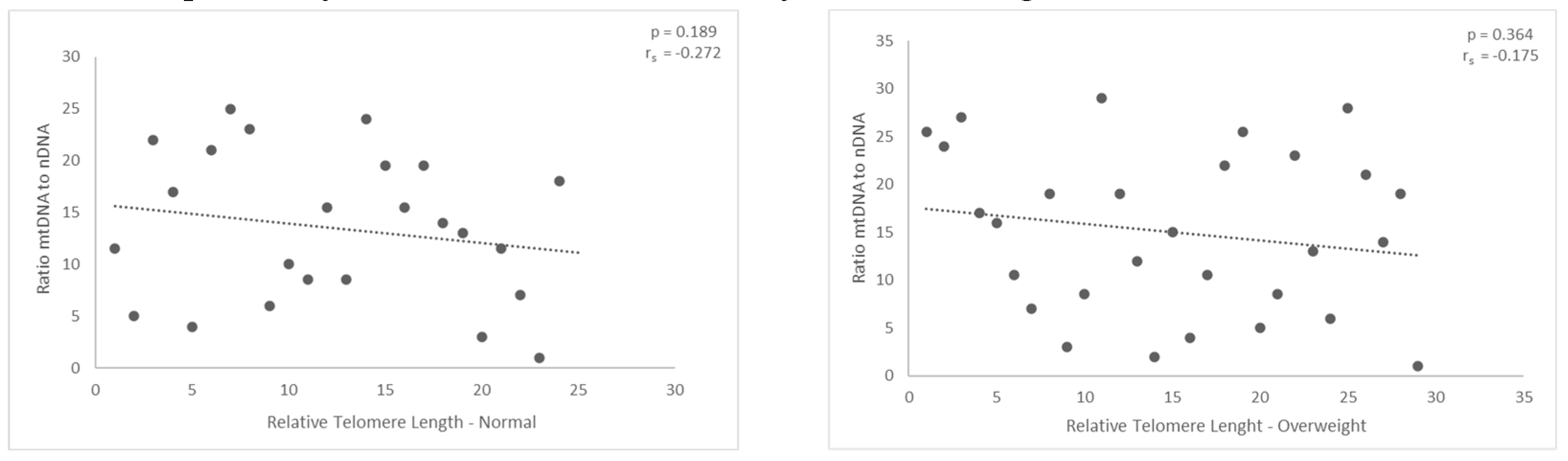

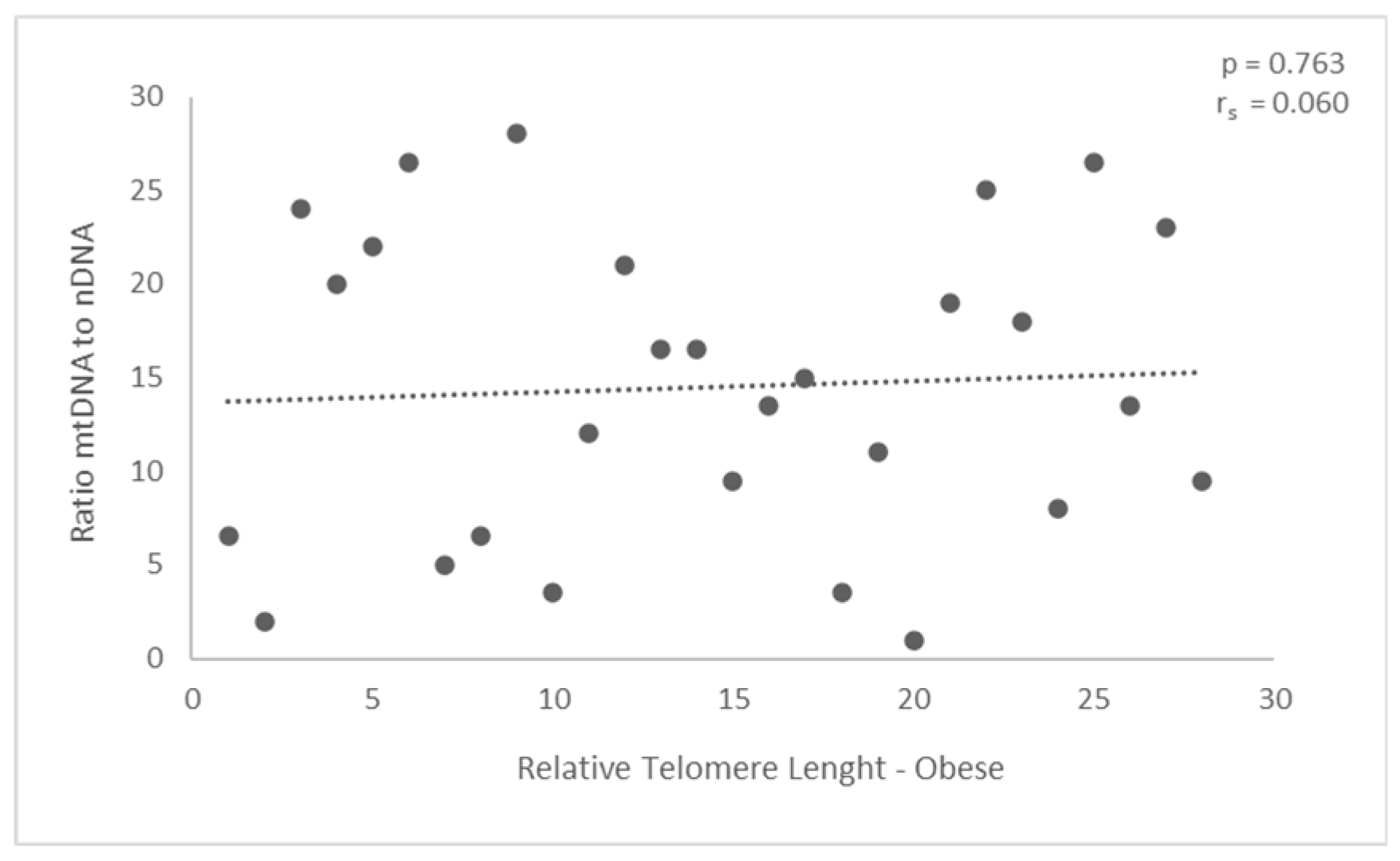

2.2. Correlation between mtDNA to nDNA ratio and the relative telomere length

Assessing the correlation between relative telomere length and the ratio of nuclear to mitochondrial DNA followed next. The diagram demonstrates the first finding, which is that there was a negative correlation between those with normal and overweight BMIs. The findings (p = 0.189 and p = 0.36, respectively) did not demonstrate any statistical significance.

Nevertheless, the outcomes did not reach statistical significance for the group classified as obese. In particular, the ratio displayed a modest positive correlation with the relative length of telomeres in the obese group, however, the p-value is only p = 0.763. The results obtained were not statistically significant.

3. Discussion

This study examined the three parameters for each of the three subject groups based on body mass index and compared them with relative telomere length. When comparing the relative length of telomeres to BMI, it was first observed that there was a positive association for obese individuals and a negative correlation for normal and overweight groups. The results were statistically significant only for the obese group, suggesting that weight affects telomere length and consequently sperm quality.

Similar findings were observed when comparing mitochondrial content and relative telomere length. There is a positive association for the obese group and a negative correlation for the normal and overweight groups. Lastly, research was done on the relationship between the ratio of mitochondrial DNA to nuclear DNA and relative telomere length. The correlation was positive for the obese group and negative for the normal and overweight groups. For all the groups under investigation (normal, overweight, and obese), neither case showed statistically significant outcomes.

Telomere length and structure are essential for maintaining the integrity of the nuclear genome, and spermatogenesis and conception are specifically linked to the maintenance of telomeres in germ cells[

17]. An essential component of the dynamic maintenance of telomere length homeostasis is the existence of telomerase activity in spermatogenic cells. Previous research, however, has demonstrated that both endogenous and exogenous variables, including oxidative stress, inflammation, exposure to the environment, and lifestyle choices, may disrupt telomere homeostasis[

18,

19,

20,

21]. According to several studies, telomerase may even be triggered in some circumstances, leading to telomere elongation[

18,

19,

20]. Low levels of arsenic exposure and oxidative stress have both been shown to boost telomerase activity and lengthen telomeres[

21,

22,

23].

In the absence of direct evidence, the positive correlation between STL and sperm DNA fragmentation in young individuals may be due to the activation of telomerase by a low-level adverse factor, such as mild oxidative stress, which causes genomic damage in addition to STL extension. Moreover, sperm DNA damage is known to increase with age[

24,

25,

26]. Sperm telomere length positively correlates with age, in contrast to most cell lines and tissues[

27,

28]. In the absence of longitudinal data, a recent cross-sectional study by Antunes et al. makes a similar claim that spermatozoa have lengthened telomeres throughout male aging[

29]. The study concluded that the telomere lengthening process must involve an alternative mechanism (=ALT) in addition to the telomerase enzyme. In aging male spermatozoa, there is a significant rise in mean TL and, more importantly, a rise in TL variability, both of which are associated with ALT[

29].

Telomeres, telomerase subunits, and mitochondria have been intimately linked in recent years. Telomere damage results in the reprogramming of mitochondrial biosynthesis and mitochondrial dysfunctions, which have significant consequences for aging and diseases. On the other hand, mitochondrial dysfunctions cause telomere attrition[

30]. Different studies suggest that telomere attrition is modifiable, as substantial variability exists in the rate of telomere shortening that is independent of chronological age[

31]. Telomere attrition has also been linked with other potentially modifiable lifestyle factors, such as poor nutrition and physical inactivity indicating the plasticity of TL[

32,

33]. Findings from different studies show that a healthy diet, low stress, exercise, and a good sleep pattern are related to longer telomeres[

34,

35]. Individuals with shorter telomeres are at higher risk of chronic diseases and mortality.

Obesity is a chronic low-grade inflammatory condition that induces the generation of oxidative stress and inflammation. A high body mass index can also lead to a low sperm count while a male’s testosterone will transfer into estrogen, reducing sperm production[

36]. Obesity also raises the scrotum temperature which negatively affects the health of the sperm. Furthermore, OS may result from modifications to mitochondrial activity, which can greatly raise reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels[

37]. A body of evidence has been gathered demonstrating that telomerase can also function in telomere-independent ways and that, under OS, the TERT transfers between the nucleus and mitochondria, and the TERC is processed, imported into mitochondria, and exported back to the cytosol[

30].

The regulation of mitochondrial DNA copy number (mtDNAcn) is a crucial process that controls the expression of mtDNA genes in mitochondria, in contrast to nuclear DNA. For instance, it has been demonstrated that mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) is crucial for maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis and covering up for low mtDNA content in mature human sperm[

38]. Increased mtDNAcn in human sperm has been identified as an indicator of male infertility since the majority of studies have demonstrated a negative correlation between sperm mtDNAcn and several semen parameters, such as sperm concentration, motility, morphology, and mtDNA integrity[

39,

40,

41]. An increase in mtDNA could be the result of a feedback process compensating for the damaged mitochondria[

42].

In addition to nuclear DNA, male infertility is also influenced by mitochondrial DNA. The normal process of fertilization may be affected by alterations in the mtDNA. Telomere length and mtDNAcn are positively correlated, according to several epidemiological research conducted on leukocytes[

43,

44,

45,

46]. Nonetheless, not much research has been done on potential correlations between telomeres and mitochondrial characteristics in human sperm. It is widely acknowledged that mtDNA is especially prone to cumulative mutation and deletion, either as a result of its proximity to the respiratory chains, which produce reactive oxygen species or because it lacks protective histones. Oxidative insults are known to affect both nuclear and mitochondrial DNA[

47].

The question of whether TL may be used as a diagnostic for sperm quality and fertility is a crucial one in the field of male germ cell telomere biology right now. Men’s sperm chromatin quality is not taken into account by the World Health Organization (WHO)’s (WHO) standards for evaluating male fertility[

48]. Even though sperm DNA integrity testing is regarded as a significant endpoint, many of the procedures have historically been difficult to use in a clinical environment since they rely on a high level of technical knowledge. There is therefore a need for an efficient, repeatable test that would look at a novel sperm parameter. Given that early research is starting to reveal associations between sperm TL and reproductive outcomes, TL is a desirable measurement[

17].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants’ characteristics and semen sample collection

The current study included eighty-two (82) men who underwent IVF/ICSI at the IVF Unit of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department of the University Hοspital of Iοannina, Ioannina, Greece. Men were classified into three groups based on their BMI. Twenty-five (25) of the men recruited had normal ΒΜΙ (ranging from 18 to 24.9 kg/m2), twenty-nine (29) men were overweight (ranging from 25 to 29.9 kg/m2), and twenty-eight (28) men were obese (class I & II) with a ΒΜΙ higher than 30 kg/m2. Each participant signed an informed consent form. The characteristics of each sperm sample were identified using Kruger’s criteria.

According to Kruger et al., tougher sperm morphology standards may be a reliable indicator of infertility during in vitro fertilization (IVF). According to Kruger’s requirements, the sperm head must be oval-shaped, regular, and have a smooth, constant outline. Additionally, the acrosome must be intact. Furthermore, midpiece and tail abnormalities are not permitted. Another indication of morphological issues may be bent, numerous, or short tails as well as coiled, bowed, or sloppy midpieces. Finally, a high cytoplasmic droplet count may be a sign of sperm immaturity.

4.2. Sperm DNA extraction and quantification

In the fresh semen samples sperm parameters such as sperm count, motility, morphology, and DFI using Computer Aided Semen Analysis (CASA), within an hour of ejaculation. The samples were then frozen at a temperature of –20°C for storage. The Qiagen methodology was used in the current investigation along with a matching kit; the QIAmp DNA blood Mini kit. During the first stage, 100μl of semen sample was combined with an X2 buffer, and heated for at least an hour at 56 °C in the heat block. Each sample was vortexed at regular intervals. Following this, a volume of 200μL from each preheated semen sample was processed for sperm DNA extraction using the QIAmp DNA blood Mini kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Using a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA, the isolated sperm DNA was eluted in 80μL of elution buffer and measured to determine purity and concentrations. By evaluating the A260/A80 ratio using spectroscopy for DNA analysis, the quality of the isolated DNA was evaluated. A human cell population’s average TL can be measured directly using the Absolute Human Telomere Length Quantification qPCR Assay Kit (AHTLQ) from ScienCell. Recοgnizing and amplifying telοmere sequences is the function of the telomere primer pair. Data normalization was accomplished using the single copy reference (SCR) primer pair, which identifies and amplifies the human chromosome 17 region of 100 base pairs.

4.3. Real-time quantitive PCR – qPCR

A quantitative polymerase chain reaction was employed to measure the absolute telomere length. Every genomic DNA sample was used in two separate qPCR procedures, one using telomere primer stock solution and the other using SCR primer stock solution. We employed the following components in each reaction: 0.5–0.5 ng/μL of genomic DNA template, 2μL of primer stock solution (Telomere or SCR), 10μL of 2X GoldNStart TaqGreen qPCR master mix, 7μL of nuclease-free water, and a total volume of 20μL. The reaction was conducted on a Corbett Rotor-Gene 3000 Real-Time Rotary Analyzer (Corbett Research, Sydney, Australia) using the cycling conditions listed below: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 32 cycles of denaturing at 95 °C for 20 s, annealing at 52 °C for 20 s, and extension at 72 °C for 45 s. Following data collection, a hold at 25°C for 1 min was performed. Data were analyzed using the SPSS statistical program.

4.4. Quantification Method: Comparative ΔΔCq Method based on the AHTLQ assay kit

The difference in the number of quantification cycles of telomeres (TEL) between the target and reference genomic DNA samples is known as Cq (TEL).

For single-copy references, Cq (SCR) is the number of quantification cycles that differ between the reference and target genomic DNA samples.

ΔΔCq= ΔCq (TEL) – ΔCq (SCR)

The target sample’s relative telomere length to the reference sample (fold) =2-ΔΔCq

4.5. Statistical analysis

The association between the two variables was evaluated statistically using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. The statistical software SPSS was used to analyze the data between the groups under study. The direction and correlation coefficient (rs) between the variables shown in the graph are reported numerically in the analysis. Microsoft Excel spreadsheets were used to organize the extraction data, mtDNA copy numbers, and Ct rates to create graphs. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

5. Conclusions

Consequently, the investigation into the relationship between relative TL and mitοchοndrial DNA content has shed light on the complex interactions between these two vital aspects of cellular health and aging[

47]. The evidence points to a complex interaction that may have repercussions for our knowledge of how cells age, how they become susceptible to disease, and how they operate as a whole. To form a more comprehensive opinion, additional research is necessary. The findings highlight the significance of preserving mitochondrial health and telomere integrity as critical elements in promoting lifespan and general well-being, even though more study is required to clarify the specific nature of this link. This discovery could influence future medical therapies and methods meant to maintain cellular vitality and lengthen healthy lifespans as our understanding of these interrelated processes continues to advance.

6. Limitations of the study

When evaluating the study’s findings, one should take into account a number of its shortcomings. Firstly, a smaller sample size may have limited how broadly the results may be applied to the public. Furthermore, answer bias and recall errors may have been introduced by the data collection strategy, which mostly relied on self-report surveys. The study was also limited by the geographic area in which it was carried out, thus contextual and cultural factors may have a different effect on the findings elsewhere. Relative measurements are often obtained by PCR-based methods, which are the most widely used approaches for measuring mtDNA-CN and telomere length. Furthermore, no research has been done that focuses on population-based studies and systematically examines the relationship between telomere length, mtDNA-CN, and sperm prevalence, incidence, and death. Finally, logistical and ethical limitations may have affected the study’s conduct and results, as they do with any research involving human beings. These restrictions highlight the need for additional investigation to strengthen and improve the understanding this study provided.

Author Contributions

Data curation, A.Z. (Athanasios Zikopoulos), C.S., S.S. and P.D.; Methodology, A.Z. (Athanasios Zikopoulos), C.S., S.S. and P.D.; Project administration, I.G. and A.Z. (Athanasios Zachariou); Resources, I.G. and A.Z. (Athanasios Zachariou).; Supervision, I.G.; Writing—original draft, E.M.; Writing—review and editing, E.M., A.Z. (Athanasios Zikopoulos), and I.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to in vitro fertilization (IVF).

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

We offer a thorough summary of all the variables examined in this research in this appendix. To improve transparency and reproducibility for readers and other researchers, we hope that this information will be presented in an orderly and systematic way, enabling a greater understanding of the variables and their impact on our study.

References

- Hayflick L, Moorhead PS. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res. 1961 Dec;25:585–621. [CrossRef]

- van Deursen JM. The role of senescent cells in aging. Nature. 2014 May 22;509(7501):439–46. [CrossRef]

- Griffith JD, Comeau L, Rosenfield S, Stansel RM, Bianchi A, Moss H, et al. Mammalian Telomeres End in a Large Duplex Loop. Cell. 1999 May;97(4):503–14. [CrossRef]

- Chan SRWL, Blackburn EH. Telomeres and telomerase. Sherratt DJ, West SC, editors. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004 Jan 29;359(1441):109–22. [CrossRef]

- Turner S, Hartshorne GM. Telomere lengths in human pronuclei, oocytes, and spermatozoa. Mol Hum Reprod. 2013 Aug 1;19(8):510–8. [CrossRef]

- Kimura M, Cherkas LF, Kato BS, Demissie S, Hjelmborg JB, Brimacombe M, et al. Offspring’s leukocyte telomere length, paternal age, and telomere elongation in sperm. PLoS Genet. 2008 Feb;4(2):e37. [CrossRef]

- Baird DM, Britt-Compton B, Rowson J, Amso NN, Gregory L, Kipling D. Telomere instability in the male germline. Hum Mol Genet. 2006 Jan 1;15(1):45–51. [CrossRef]

- Johnson GD, Lalancette C, Linnemann AK, Leduc F, Boissonneault G, Krawetz SA. The sperm nucleus: chromatin, RNA, and the nuclear matrix. REPRODUCTION. 2011 Jan;141(1):21–36. [CrossRef]

- Steger K. Transcriptional and translational regulation of gene expression in haploid spermatids. Anat Embryol (Berl). 1999 Apr 21;199(6):471–87. [CrossRef]

- Carrell DT, Emery BR, Hammoud S. Altered protamine expression and diminished spermatogenesis: what is the link? Hum Reprod Update. 2007 May 1;13(3):313–27. [CrossRef]

- De Vries M, Ramos L, Housein Z, De Boer P. Chromatin remodeling initiation during human spermiogenesis. Biol Open. 2012 May 15;1(5):446–57. [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden GW, Dieker JW, Derijck AAHA, Muller S, Berden JHM, Braat DDM, et al. Asymmetry in histone H3 variants and lysine methylation between paternal and maternal chromatin of the early mouse zygote. Mech Dev. 2005 Sep;122(9):1008–22. [CrossRef]

- Wright WE, Piatyszek MA, Rainey WE, Byrd W, Shay JW. Telomerase activity in human germline and embryonic tissues and cells. Dev Genet. 1996;18(2):173–9. [CrossRef]

- Ioannou D, Tempest HG. Human Sperm Chromosomes: To Form Hairpin-Loops, Or Not to Form Hairpin-Loops, That Is the Question. Genes. 2019 Jul 3;10(7):504. [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen PB, Fedder J, Koelvraa S, Graakjaer J. Age-dependence of relative telomere length profiles during spermatogenesis in man. Maturitas. 2013 Aug;75(4):380–5. [CrossRef]

- Nordfjäll K, Larefalk Å, Lindgren P, Holmberg D, Roos G. Telomere length and heredity: Indications of paternal inheritance. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005 Nov 8;102(45):16374–8. [CrossRef]

- Fice H, Robaire B. Telomere Dynamics Throughout Spermatogenesis. Genes. 2019 Jul 12;10(7):525. [CrossRef]

- Yim HW, Slebos RJC, Randell SH, Umbach DM, Parsons AM, Rivera MP, et al. Smoking is associated with increased telomerase activity in short-term cultures of human bronchial epithelial cells. Cancer Lett. 2007 Feb 8;246(1–2):24–33. [CrossRef]

- Ferrario D, Collotta A, Carfi M, Bowe G, Vahter M, Hartung T, et al. Arsenic induces telomerase expression and maintains telomere length in human cord blood cells. Toxicology. 2009 Jun 16;260(1–3):132–41. [CrossRef]

- Mo J, Xia Y, Ning Z, Wade TJ, Mumford JL. Elevated human telomerase reverse transcriptase gene expression in blood cells associated with chronic arsenic exposure in Inner Mongolia, China. Environ Health Perspect. 2009 Mar;117(3):354–60. [CrossRef]

- López-Diazguerrero NE, Pérez-Figueroa GE, Martínez-Garduño CM, Alarcón-Aguilar A, Luna-López A, Gutiérrez-Ruiz MC, et al. Telomerase activity in response to mild oxidative stress. Cell Biol Int. 2012 Apr 1;36(4):409–13. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Rhee DB, Lu J, Bohr CT, Zhou F, Vallabhaneni H, et al. Characterization of oxidative guanine damage and repair in mammalian telomeres. PLoS Genet. 2010 May 13;6(5):e1000951. [CrossRef]

- Mishra S, Kumar R, Malhotra N, Singh N, Dada R. Mild oxidative stress is beneficial for sperm telomere length maintenance. World J Methodol. 2016;6(2):163. [CrossRef]

- Wyrobek AJ, Eskenazi B, Young S, Arnheim N, Tiemann-Boege I, Jabs EW, et al. Advancing age has differential effects on DNA damage, chromatin integrity, gene mutations, and aneuploidies in sperm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Jun 20;103(25):9601–6. [CrossRef]

- Vagnini L, Baruffi RLR, Mauri AL, Petersen CG, Massaro FC, Pontes A, et al. The effects of male age on sperm DNA damage in an infertile population. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007 Nov;15(5):514–9. [CrossRef]

- Gunes S, Hekim GNT, Arslan MA, Asci R. Effects of aging on the male reproductive system. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016 Apr;33(4):441–54. [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg DTA. An evolutionary review of human telomere biology: the thrifty telomere hypothesis and notes on potential adaptive paternal effects. Am J Hum Biol Off J Hum Biol Counc. 2011;23(2):149–67. [CrossRef]

- Aston KI, Hunt SC, Susser E, Kimura M, Factor-Litvak P, Carrell D, et al. Divergence of sperm and leukocyte age-dependent telomere dynamics: implications for male-driven evolution of telomere length in humans. Mol Hum Reprod. 2012 Nov 1;18(11):517–22. [CrossRef]

- Antunes DMF, Kalmbach KH, Wang F, Dracxler RC, Seth-Smith ML, Kramer Y, et al. A single-cell assay for telomere DNA content shows increasing telomere length heterogeneity, as well as increasing mean telomere length in human spermatozoa with advancing age. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015 Nov;32(11):1685–90. [CrossRef]

- Zheng Q, Huang J, Wang G. Mitochondria, Telomeres and Telomerase Subunits. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2019 Nov 6;7:274. [CrossRef]

- Du M, Prescott J, Kraft P, Han J, Giovannucci E, Hankinson SE, et al. Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Leukocyte Telomere Length in Women. Am J Epidemiol. 2012 Mar 1;175(5):414–22. [CrossRef]

- Cassidy A, De Vivo I, Liu Y, Han J, Prescott J, Hunter DJ, et al. Associations between diet, lifestyle factors, and telomere length in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010 May 1;91(5):1273–80. [CrossRef]

- Puterman E, Lin J, Blackburn E, O’Donovan A, Adler N, Epel E. The Power of Exercise: Buffering the Effect of Chronic Stress on Telomere Length. Vina J, editor. PLoS ONE. 2010 May 26;5(5):e10837. [CrossRef]

- Farzaneh-Far, R. Association of Marine Omega-3 Fatty Acid Levels With Telomeric Aging in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease. JAMA. 2010 Jan 20;303(3):250. [CrossRef]

- Ornish D, Lin J, Daubenmier J, Weidner G, Epel E, Kemp C, et al. Increased telomerase activity and comprehensive lifestyle changes: a pilot study. Lancet Oncol. 2008 Nov;9(11):1048–57. [CrossRef]

- on behalf of Obesity Programs of Nutrition, Education, Research and Assessment (OPERA) Group, Bellastella G, Menafra D, Puliani G, Colao A, Savastano S. How much does obesity affect male reproductive function? Int J Obes Suppl. 2019 Apr;9(1):50–64. [CrossRef]

- Jing J, Peng Y, Fan W, Han S, Peng Q, Xue C, et al. Obesity-induced oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction negatively affect sperm quality. FEBS Open Bio. 2023 Apr;13(4):763–78. [CrossRef]

- Amaral A, Ramalho-Santos J, St John JC. The expression of polymerase gamma and mitochondrial transcription factor A and the regulation of mitochondrial DNA content in mature human sperm. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2007 Jun;22(6):1585–96. [CrossRef]

- May-Panloup P, Chrétien MF, Savagner F, Vasseur C, Jean M, Malthièry Y, et al. Increased sperm mitochondrial DNA content in male infertility. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2003 Mar;18(3):550–6. [CrossRef]

- Song GJ, Lewis V. Mitochondrial DNA integrity and copy number in sperm from infertile men. Fertil Steril. 2008 Dec;90(6):2238–44. [CrossRef]

- Tian M, Bao H, Martin FL, Zhang J, Liu L, Huang Q, et al. Association of DNA methylation and mitochondrial DNA copy number with human semen quality. Biol Reprod. 2014 Oct;91(4):101. [CrossRef]

- Ling X, Cui H, Chen Q, Yang W, Zou P, Yang H, et al. Sperm telomere length is associated with sperm nuclear DNA integrity and mitochondrial DNA abnormalities among healthy male college students in Chongqing, China. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2023 Jun 1;38(6):1036–46. [CrossRef]

- Kim JH, Kim HK, Ko JH, Bang H, Lee DC. The relationship between leukocyte mitochondrial DNA copy number and telomere length in community-dwelling elderly women. PloS One. 2013;8(6):e67227. [CrossRef]

- Qiu C, Enquobahrie DA, Gelaye B, Hevner K, Williams MA. The association between leukocyte telomere length and mitochondrial DNA copy number in pregnant women: a pilot study. Clin Lab. 2015;61(3–4):363–9. [CrossRef]

- Alegría-Torres JA, Velázquez-Villafaña M, López-Gutiérrez JM, Chagoyán-Martínez MM, Rocha-Amador DO, Costilla-Salazar R, et al. Association of Leukocyte Telomere Length and Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number in Children from Salamanca, Mexico. Genet Test Mol Biomark. 2016 Nov;20(11):654–9. [CrossRef]

- Melicher D, Illés A, Littvay L, Tárnoki ÁD, Tárnoki DL, Bikov A, et al. Positive association and future perspectives of mitochondrial DNA copy number and telomere length - a pilot twin study. Arch Med Sci AMS. 2021;17(5):1191–9. [CrossRef]

- Moustakli E, Zikopoulos A, Sakaloglou P, Bouba I, Sofikitis N, Georgiou I. Functional association between telomeres, oxidation and mitochondria. Front Reprod Health. 2023 Feb 20;5:1107215. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Annual technical report: 2013 : department of Reproductive Health and research, including UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP) [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014 [cited 2022 May 30]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/112658.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).