Submitted:

27 November 2023

Posted:

29 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fiber Samples and Their Chemical Compositions

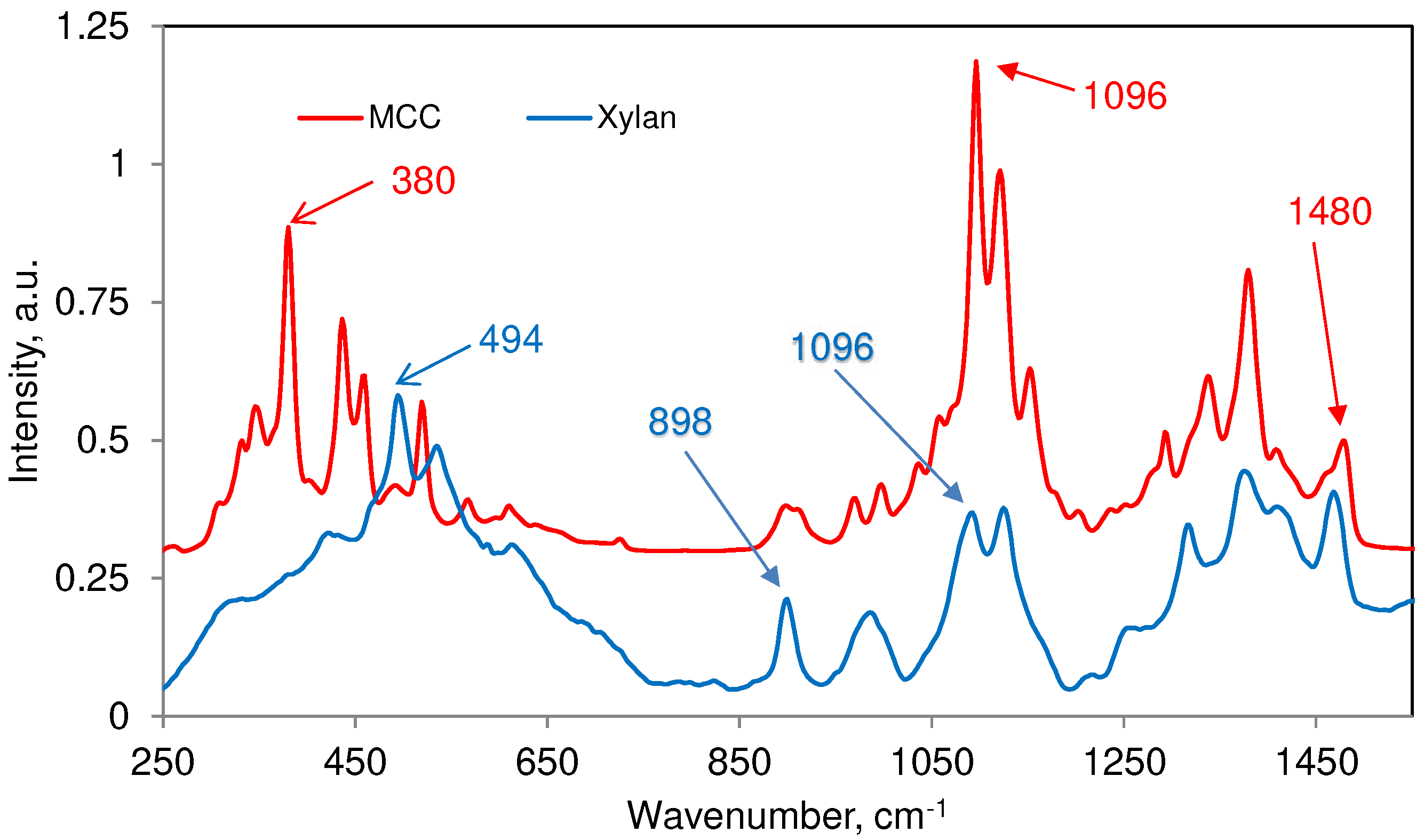

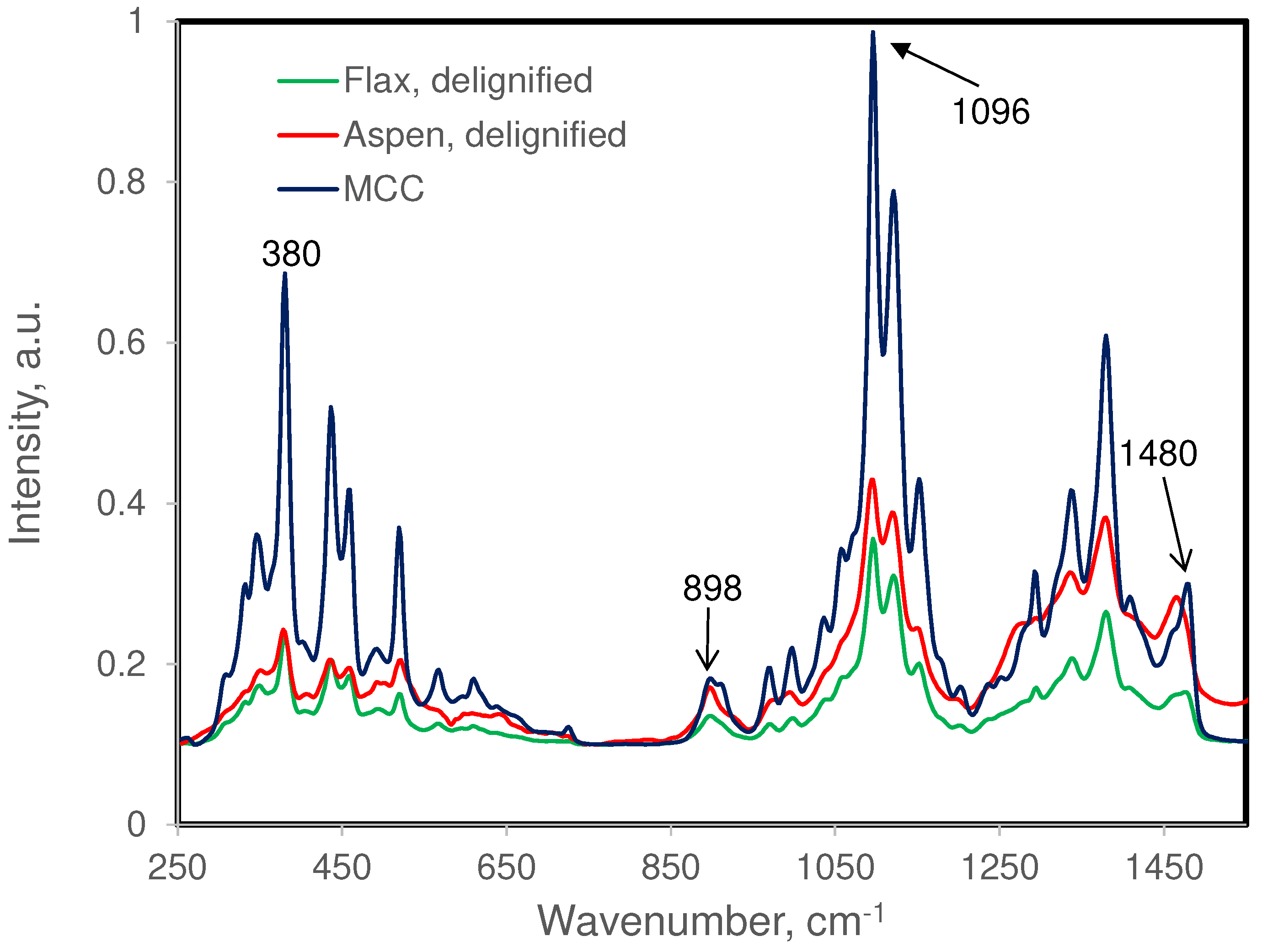

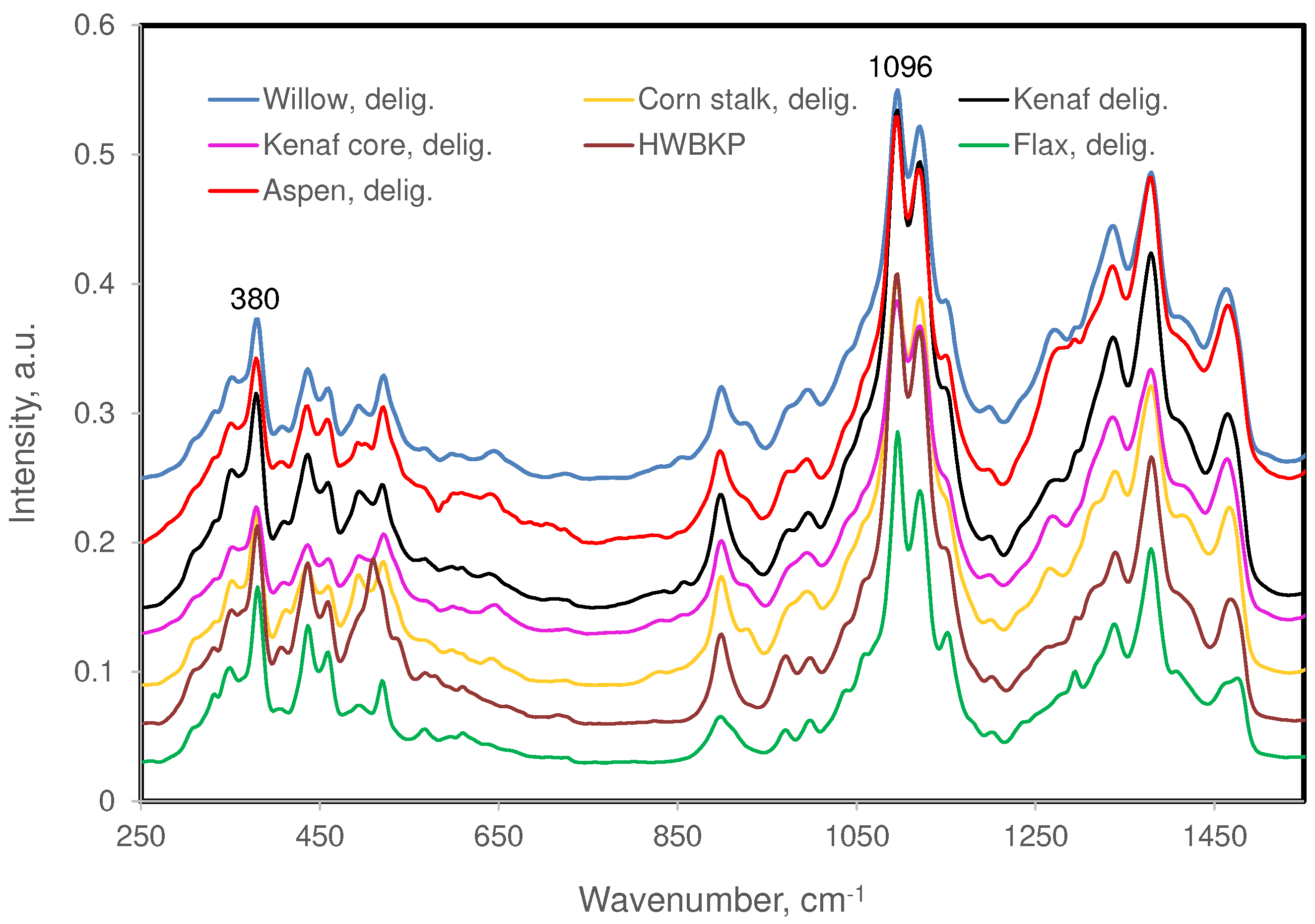

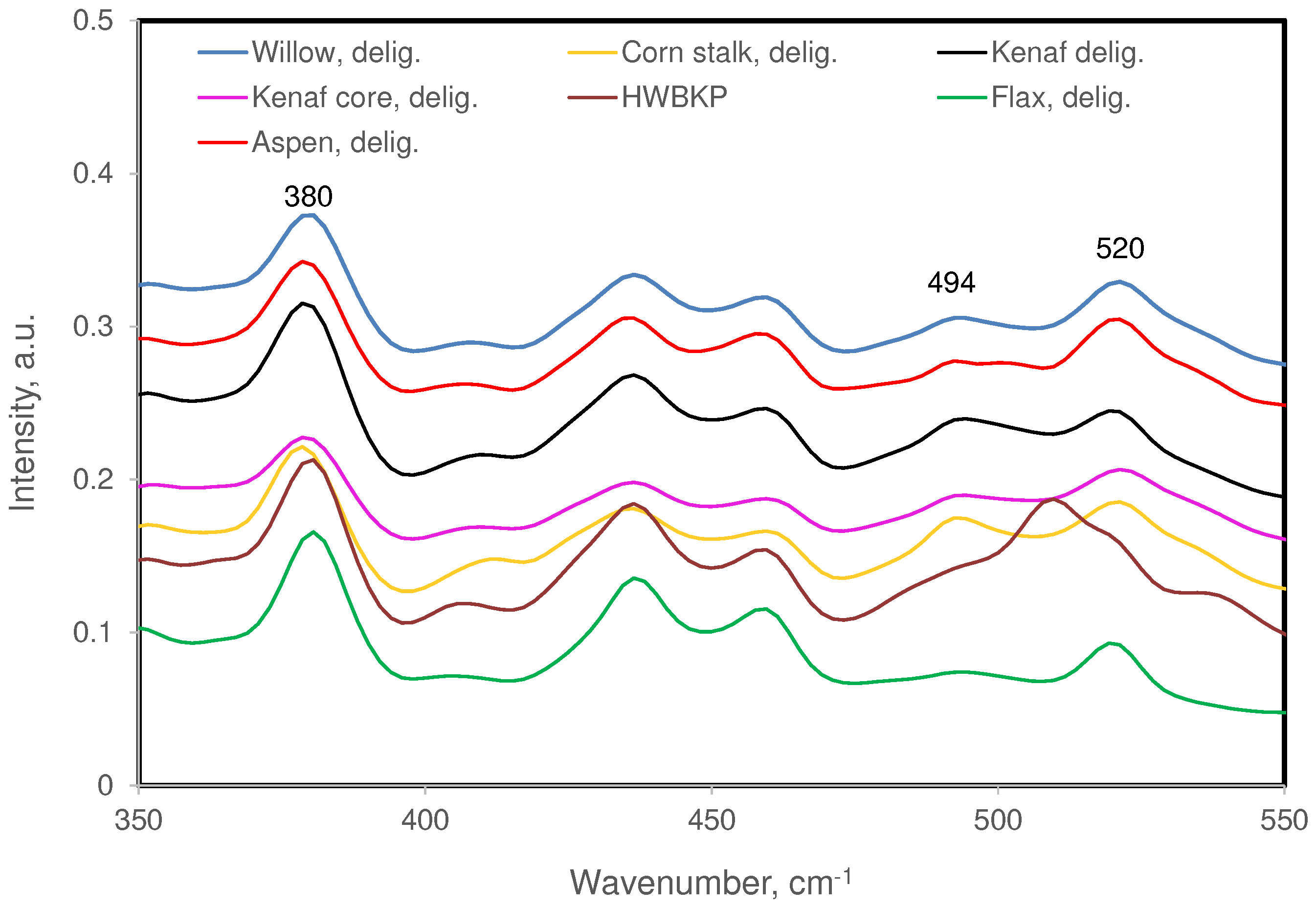

3.2. Raman Bands of Cellulose and Other Cell Wall Components

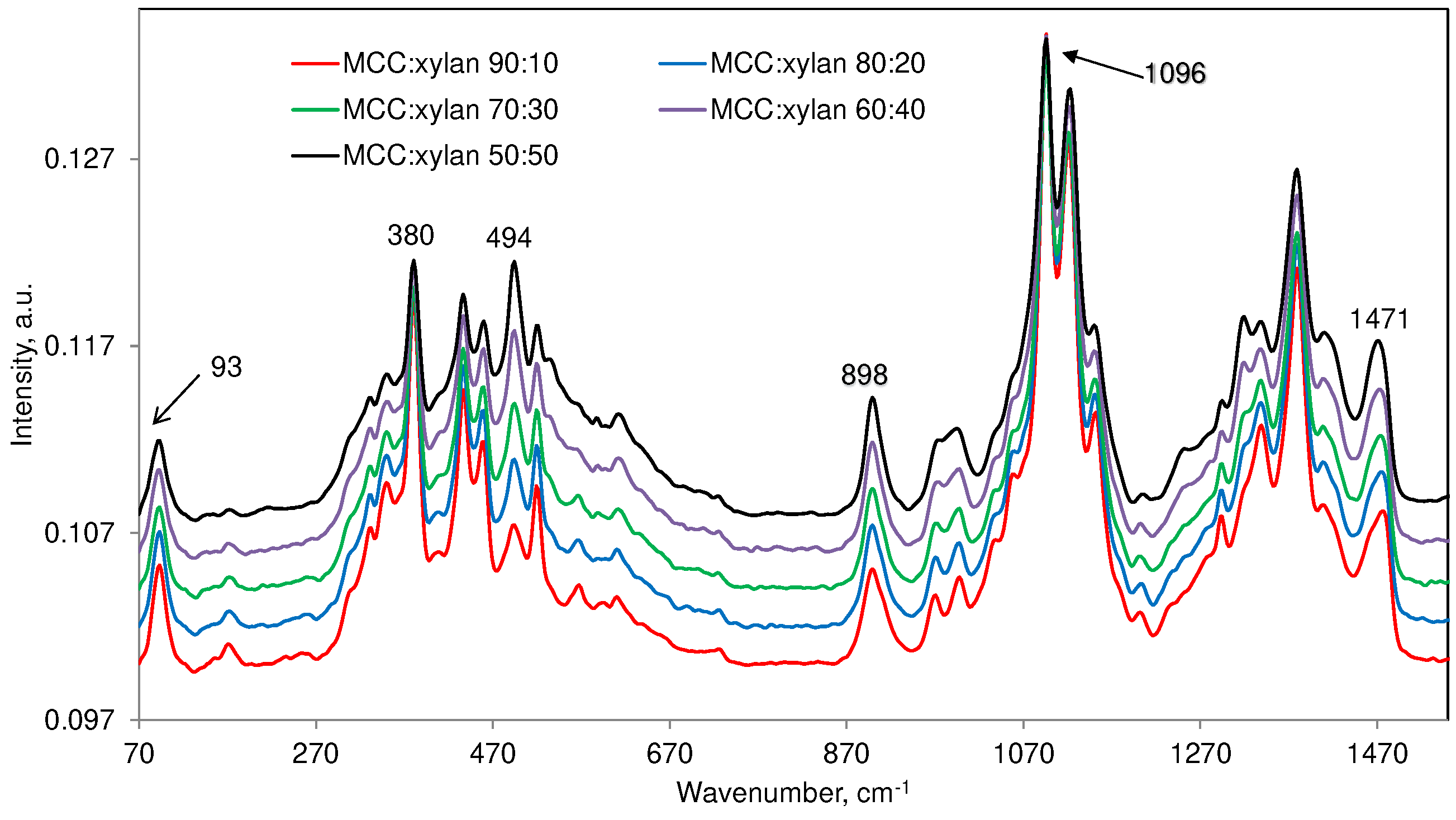

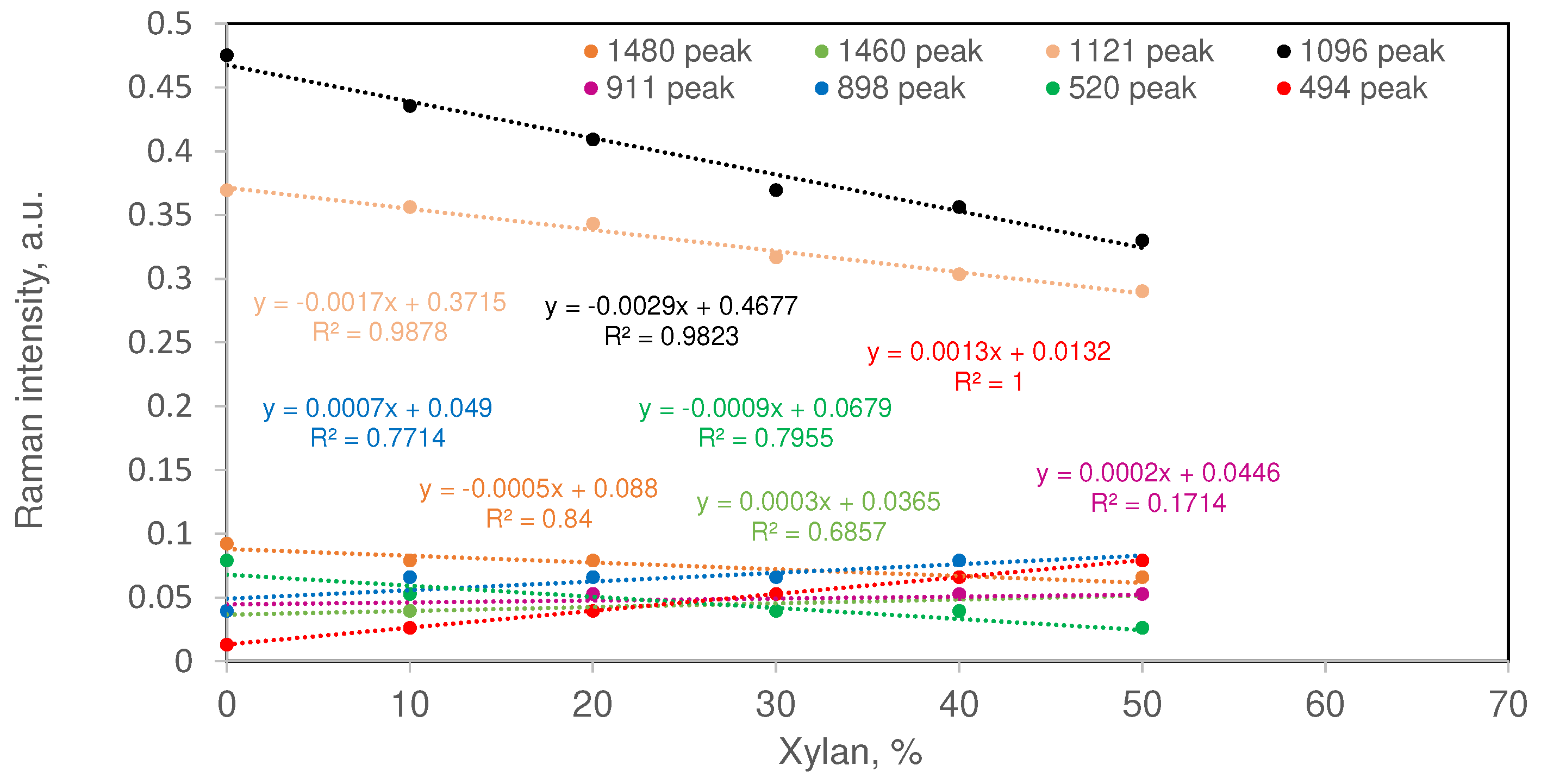

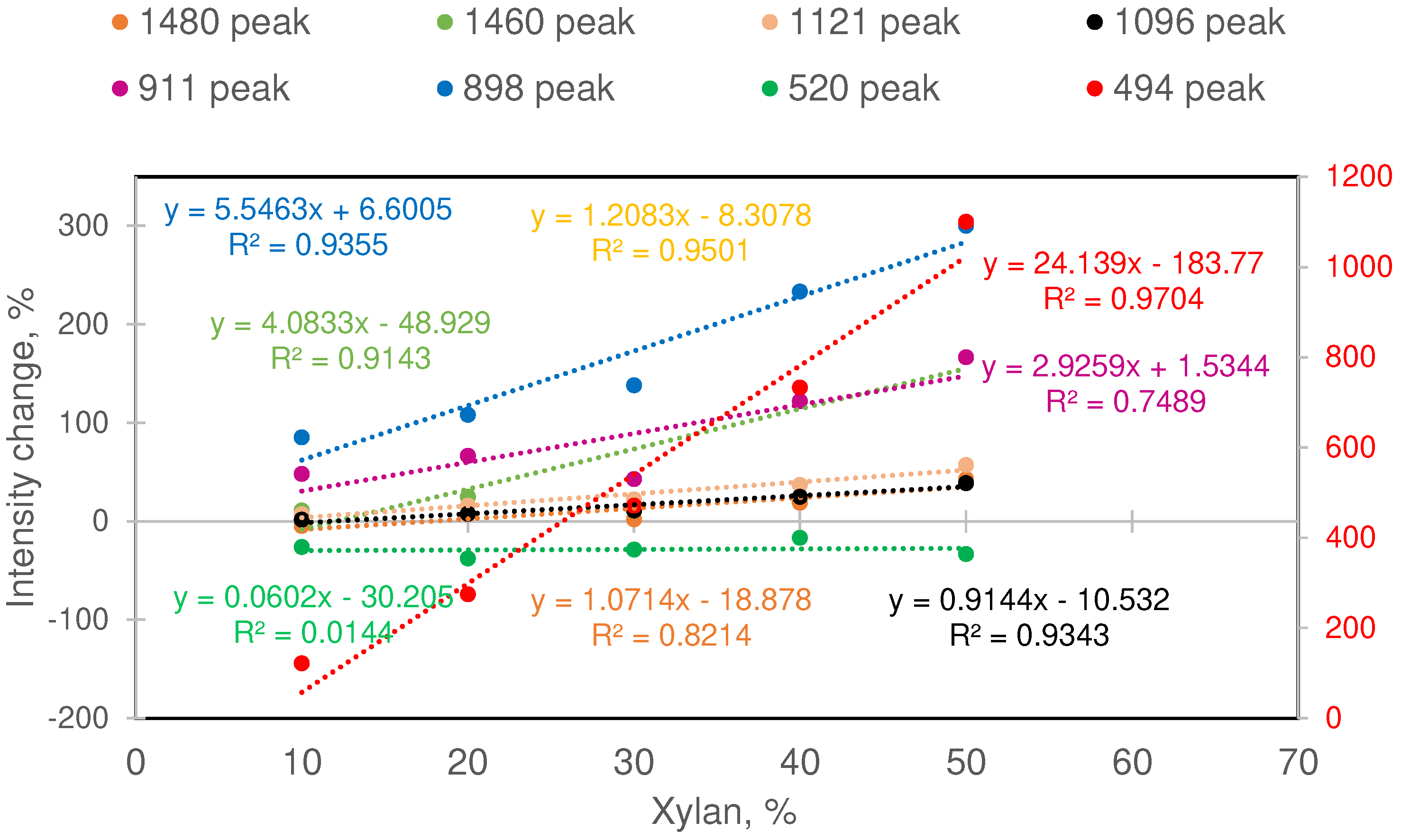

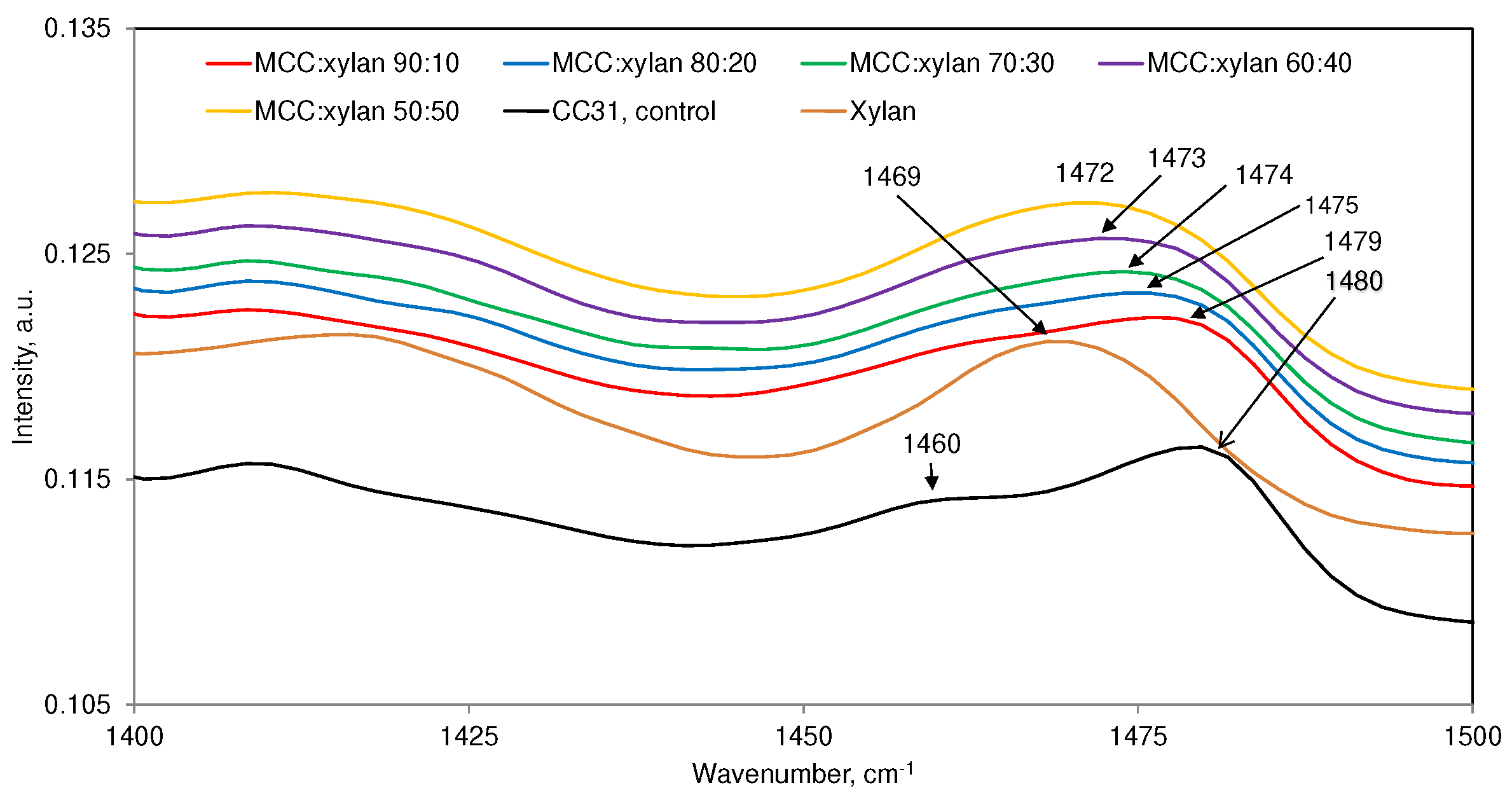

3.3. Cellulose:Xylan Mixture Samples

4. Applications to Fibers

Comparing Band Intensities

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, J.S.; Rowell, J.S. Chemical Composition of Fibers In: Paper and Composites from Agro-based Resources. Eds., R.M. Rowell, R.A. Young, and J.K. Rowell. CRC Press Inc., Boca Raton, FL. 1997; pp 83-134.

- Albersheim, P.; Darvill, A.; Roberts, K.; Sederof, R.; Staehelin, A. Plant cell walls: from chemistry to biology, 1st Edn. Garland Science, New York. 2010.

- Terrett, O.M.; Dupree, P. Covalent interactions between lignin and hemicelluloses in plant secondary cell walls. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2019, 56, 97–104. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.B.; Cosgrove, D.J. Xyloglucan and its interactions with other components of the growing cell wall. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 180–194; [CrossRef]

- Berglund, J.; Mikkelsen, D.; Flanagan, B.M.; Dhital, S.; Gaunitz, S.; Henriksson, G.; Lindström, M.E.; Yakubov, G.E.; Gidley, M.J.; Francisco Vilaplana, F. Wood hemicelluloses exert distinct biomechanical contributions to cellulose fibrillar networks. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4692. [CrossRef]

- Salmén, L. On the organization of hemicelluloses in the wood cell wall. Cellulose 2022, 29,1349–1355. [CrossRef]

- Terrett, O.M.; Lyczakowski, J.J.; Yu, L.; Iuga, D.; Franks, W.T. Brown, S.P.; Dupree, R.; Dupree, P. Molecular architecture of softwood revealed by solid-state NMR. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4978. [CrossRef]

- Pękala, P.; Szymańska-Chargot, M.; Zdunek, A. Interactions between non-cellulosic plant cell wall polysaccharides and cellulose emerging from adsorption studies. Cellulose 2023, 30, 9221–9239. [CrossRef]

- Spönla, E.; Rahikainen, J.; Potthast, A.; Grönqvist, S. High consistency enzymatic pretreatment of eucalyptus and softwood kraft fibres for regenerated fibre products. Cellulose 2023, 30, 4609–4622. [CrossRef]

- Wollboldt, R.P.; Zuckersta¨tter, G.; Weber, H.K. Larsson, P.T.; Sixta, H. Accessibility, reactivity, and supramolecular structure of E. globulus pulps with reduced xylan content. Wood Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 533–546. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U.P. 1064 nm FT-Raman spectroscopy for investigations of plant cell walls and other biomass materials. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5: 490; [CrossRef]

- Lupoi, J.S.; Singh, S.; Simmons, B.A.; Henry, R.J. Assessment of Lignocellulosic Biomass Using Analytical Spectroscopy: An Evolution to High-Throughput Techniques. 2014, 7, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Gierlinger, N. New Insights into Plant Cell Walls by Vibrational Microspectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2018, 53, 517–551. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U.P. Analysis of Cellulose and Lignocellulose Materials by Raman Spectroscopy: A Review of the Current Status. Molecules 2019, 24, 1659. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U.P.; Ralph, S.A. FT-Raman Spectroscopy of Wood: Identifying contributions of lignin and carbohydrate polymers in the spectrum of black spruce (Picea mariana). Appl. Spectrosc. 1997, 51, 1648–1655; [CrossRef]

- Himmelsbach, D.S.; Akin, D.E. Near-Infrared Fourier-Transform Raman Spectroscopy of Flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) Stems. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 991–998. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U.P. Raman imaging to investigate ultrastructure and composition of plant cell walls: distribution of lignin and cellulose in black spruce wood (Picea mariana). Planta 2006, 224: 1141–1153; [CrossRef]

- Kanbayashi, T.; Kataoka, Y.; Ishikawa, A.; Matsunaga, M.; Kobayashi, M.; Kiguchi, M. Depth profiling of photodegraded wood surfaces by confocal Raman microscopy. J. Wood Sci. 2018, 64, 169. [CrossRef]

- Saletnik, A.; Saletnik, B.; Puchalski, C. Overview of popular techniques of Raman spectroscopy and their potential in the study of plant tissues. Molecules 2021, 26, 1537. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U.P.; McSweeny, J.D.; Ralph, S.A. FT–Raman Investigation of Milled-wood Lignins: Softwood, hardwood, and chemically modified black spruce lignins. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 2011, 17, 324–344. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U.P.; Reiner, R.S.; and Ralph, S.A. Estimation of cellulose crystallinity of lignocelluloses using near-IR FT-Raman spectroscopy and comparison of the Raman and Segal-WAXS methods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 103–113. [CrossRef]

- Schenzel, K.; Fischer, S.; Brendler, E. New method for determining the degree of cellulose I crystallinity by means of FT Raman spectroscopy. Cellulose 2005, 12, 223–231.

- Agarwal, U.P; Ralph, S.A.; Reiner, R.S.; Baez, C. New cellulose crystallinity estimation method that differentiates between organized and crystalline phases. Carbohydr. Poly. 2018, 190, 262–270. [CrossRef]

- Browning, B. L. Methods of Wood Chemistry; Wiley-Interscience:New York, 1967; Vol. II.

- TAPPI Test Method. Acid insoluble lignin in wood and pulp; official test method T-222 (Om). 1983, TAPPI, Atlanta.

- Davis, M.W. A rapid method for compositional carbohydrate analysis of lignocellulosics by high pH anion-exchange chromatography with pulse amperometric detection (HPAE/PAD). J. Wood Chem. Technol. 1998, 18, 235–252. [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, M.J. Quantitative Analysis Using Raman Spectrometry. Applied Spectrosc. 2003, 57, 20A–42A. [CrossRef]

| Fiber samples | Glucan, % | Xylan, % | Mannan, % | Klason lignin,% | Ratio glucan:xyland |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cotton MCC | 92.2 | 0.1 | NDc | 3.1 | 99.9:0.1 |

| Flax, delignifieda | 78.8 | 1.34 | 5.02 | 1.9 | 98.3:1.7 |

| HWBKPb | 73.8 | 14.8 | ND | 4.2 | 83.3:16.7 |

| Kenaf core delignified | 56.9 | 19.3 | ND | 2.1 | 74.7:25.3 |

| Corn stalk, delignified | 53.7 | 24.4 | 0.5 | 2.13 | 68.8:31.2 |

| Willow, delignified | 47.9 | 14.4 | 1.2 | 4.3 | 76.9:23.1 |

| Aspen, delignified | 44.6 | 16.7 | 1.4 | 3.3 | 72.8:27.2 |

| Kenaf bast delignified | 44.6 | 17.5 | 1.4 | 3.3 | 71.8:28.2 |

| aAfter sample delignified by acid chlorite; bHardwood bleached kraft pulp; cND, not detected; dAssuming that the fibers are solely made of glucan and xylan (glucan + xylan = 100). | |||||

| Cellulose (MCC) | Xylana | Glucomannana | Ligninb | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 93 (m)c | ― | ― | ― | Detected in only crystalline cellulose |

| 172 (vw) | ― | ― | ― | Detected in only crystalline cellulose |

| 331 (w) | ― | ― | ― | ― |

| 345 (w) | ― | 346 (w) | ― | ― |

| 380 (m) | 377(w) | ― | 384 (w) | Cellulose contribution dominates |

| 437 (m) | ― | ― | ― | ― |

| 459 (m) | ― | ― | 463 (vw) | ― |

| 494 (w) | 494(s) | 492 (w) | 491 (vw) | Xylan contribution dominates |

| 520 (m) | ― | ― | 522 (sh) | 522 (sh) is only in syringyl lignins |

| 567 (vw) | ― | ― | ― | ― |

| 614 (vw) | 614(m) | ― | ― | ― |

| 898 (m) | 900(m) | 897 (w) | 895 (w) | Contributions mostly from MCC and xylan |

| 911 (sh) | ― | ― | ― | ― |

| 968 (w) | ― | ― | 969 (vw) | ― |

| 998 (w) | ― | ― | ― | ― |

| 1096 (s) | 1091(s) | 1089 (m) | 1090 (w) | Order of contribution MCC > xylan > glucomannan >> lignin |

| 1121 (s) | 1126(s) | 1121 (m) | 1134 (m) | Order of contribution MCC > xylan > glucomannan > lignin |

| 1152 (m) | ― | ― | ― | ― |

| 1294 (m) | ― | ― | 1297 (sh) | Both MCC and lignin contribute |

| 1339 (m) | ― | ― | 1333 (m) | Both MCC and lignin contribute |

| 1380 (m) | 1378(m) | 1374 (m) | 1363 (sh) | Order of contribution MCC > xylan = glucomannan |

| 1409 (sh) | 1413(m) | ― | Both MCC and xylan contribute | |

| 1460 (sh) | ― | 1463 (m) | 1454 (m) | Except xylan others contribute |

| 1480 (m) | 1469(m) | ― | ― | Both MCC and xylan contribute |

| aReference [15]; bReferences [15,20]; cRelative band intensities in a spectrum are indicated by vs = very strong, s = strong, m = medium, w = weak, vw = very weak, and sh = shoulder. | ||||

| Sample ID | Xylan, % | MCC, % | Changes in selected MCC band intensities %* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔI1480 | ΔI1460 | ΔI1121 | ΔI1096 | ΔI911 | ΔI898 | ΔI520 | ΔI494 | |||

| MCC | 0 | 100 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Xylan | 100 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| X1 | 10 | 90 | -4.8 | 11.1 | 7.1 | 1.9 | 48.1 | 85.2 | -25.9 | 122.2 |

| X2 | 20 | 80 | 7.1 | 25.0 | 16.1 | 7.6 | 66.7 | 108.3 | -37.5 | 275.0 |

| X3 | 30 | 70 | 2.0 | 42.9 | 22.4 | 11.1 | 42.9 | 138.1 | -28.6 | 471.4 |

| X4 | 40 | 60 | 19.0 | 122.2 | 36.9 | 25.0 | 122.2 | 233.3 | -16.7 | 733.3 |

| X5 | 50 | 50 | 42.9 | 166.7 | 57.1 | 38.9 | 166.7 | 300.0 | -33.3 | 1100.0 |

| *Changes are with respect to pure MCC fraction present in the sample. | ||||||||||

| Sample ID | Band intensitiesa, a.u. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1480 | I1460 | I1121 | I1096 | I911 | I898 | I520 | I494 | |

| Cotton MCC | 0.157 | 0.07 | 0.673 | 0.871 | 0.074 | 0.081 | 0.156 | 0.031 |

| Flax, delignified | 0.041 | 0.027 | 0.202 | 0.248 | 0.027 | 0.034 | 0.024 | 0.007 |

| HWBKP | 0.05 | 0.041 | 0.291 | 0.335 | 0.04 | 0.068 | -0.02 | 0.038 |

| Kenaf core, delignified | 0.038 | 0.063 | 0.215 | 0.234 | 0.039 | 0.061 | 0.019 | 0.023 |

| Corn stalk, delignified | 0.04 | 0.053 | 0.274 | 0.289 | 0.047 | 0.073 | 0.021 | 0.039 |

| Willow, delignified | 0.053 | 0.069 | 0.319 | 0.359 | 0.048 | 0.075 | 0.015 | 0.032 |

| Aspen, delignified | 0.04 | 0.053 | 0.274 | 0.289 | 0.047 | 0.073 | 0.021 | 0.039 |

| Kenaf bast, delignified | 0.047 | 0.070 | 0.247 | 0.275 | 0.04 | 0.059 | 0.028 | 0.022 |

| aNot normalized for different cellulose contents. | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).