1. Introduction

The number of total hip arthroplasty (THA) procedures performed annually is projected to rise 71% by the year 2030, and thus the revision burden is also predicted to grow [1].

The indications for Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty (R-THA) are varied and some of the common causes are aseptic loosening (50%), instability (16%), infection (15%), debilitating pain, periprosthetic fractures, or component failure. In revision cases, massive acetabular osteolysis with Paprosky type IIC and III defects can often be found. In these situations stable fixation of the acetabular component can be very challenging, necessitating structural bone grafting, metal augments and even custom implants. Careful preoperative planning is crucial for the proper reconstruction of hip biomechanics. A comprehensive understanding of the abnormal bony anatomy is required to accurately evaluate acetabular bone defects and manage them appropriately.

The conventional 2D radiographic image often does not allow an accurate evaluation of bone defect, because the 3D extension of the defect cannot be evaluated as well as the bone stock at the level of anterior and posterior columns as well as pelvic disjunction. Computer tomography (CT) is more accurate in evaluating bone loss and fracture lines, but metal hardware in the hip usually causes significant scatter of the images. In addition, CT evaluation on a 2D screen still poses some difficulty in anatomy evaluation. This brings about increased difficulty for the surgeon, who frequently is forced to change implant type during the intervention increasing time of intervention and related complications.

Three-dimensional (3D) printed models based on CT data can aid the surgeon in planning complex acetabular reconstruction. Regarding hip pathology, currently, the major fields of application of 3D printing planning are: treatment of proximal femoral fractures [3], treatment of acetabular fractures [4], hip arthroplasties [5], and reconstructive oncological surgery [6]. According to the current literature, 3D planning facilitates surgical planning and fracture reduction, allows for reduction of the associated soft tissue trauma, it is associated with reduced intraoperative time and blood loss, it grants minimal handling of the plate, and reduced fluoroscopic screening times. In addition, when used in combination with patient specific instruments, it resulted in more accurate acetabular cup placement than traditional planning and instrumentation.

The purpose of this study is to compare the accuracy of bony defect assessment in severe acetabular defects surgery with 3D printing planning as compared to conventional 2D radiographic planning and CT.

2. Materials and Methods

In the present study we included patients who underwent total or partial revision surgery due to septic or aseptic implant loosening classified as Paprosky IIC and III, in the period between April 2019 and December 2021. Each patient signed an informed consent form prior to surgery.

We collected patients’ characteristics, including gender, age, BMI, diagnosis, and follow up. The type of implant utilized in each patient was also recorded. For each patient included we developed a 3D printed model of the femur and pelvis based on their computed tomographic (CT) scan. Clinical and radiographic evaluations were performed before and immediately after surgery and subsequently in the various outpatient clinical checks at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months and after 1 year. Clinical evaluation was performed by an orthopedic surgeon, blinded by type of surgery, and included physical examination with measurement of Harris Hip Score (HHS) and analog scale visual (VAS) for pain. ROM evaluation was performed with a universal goniometer according to standard measurement guidelines [7,8].

2.1. Radiographic evaluation and design of 3D models

All patients had conventional anteroposterior (AP) radiographs of the pelvis and Lowenstein's lateral hip projection in both preoperative and follow-up evaluations. Two independent testers, a radiologist experienced in musculoskeletal radiology and a senior orthopedic surgeon who was not involved in the surgery of these patients, were enrolled to evaluate acetabular bone defects. Disagreements between the two testers were resolved using the intraoperative description of the defect. According to the Paprosky classification [9], acetabular defects were classified on preoperative AP radiographs using four bone landmarks: radiological tear defect, Kohler's line integrity, ischial lysis, and superior defect with cranial migration of the center of rotation of the hip.

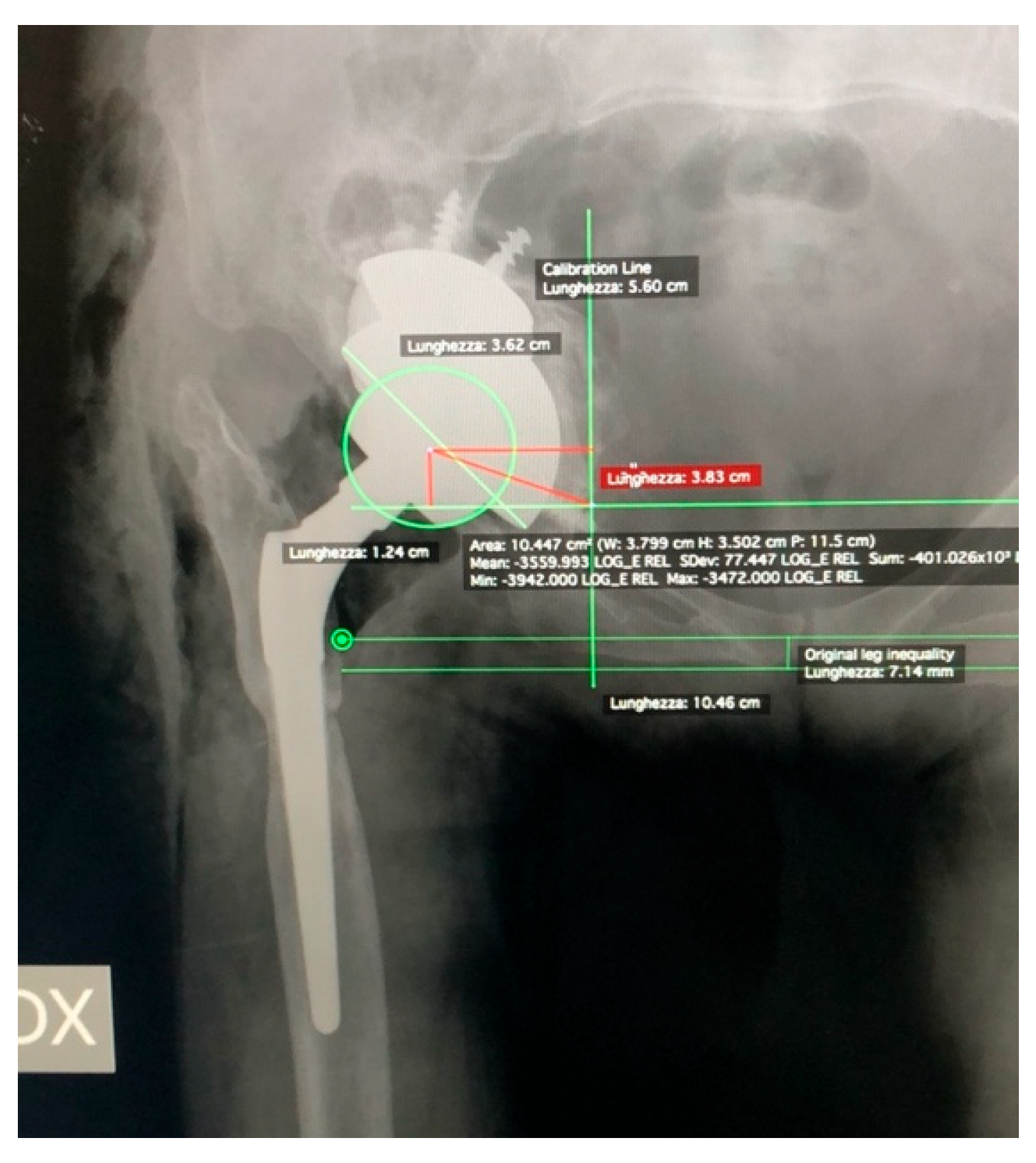

Preoperative and postoperative digital radiographs in AP view were used to assess limb length discrepancy (LLD) with Hip Artroplasty Templating 2.4.3 software running with 64-bit OsiriX v.5.8.1. Measurements were performed using the ischial tuberosities and the lesser trochanter as reference points. Preoperative and postoperative center of rotation were also measured on the vertical axis of the radiological tear and on the horizontal axis from a line passing between the radiological tears [10] (

Figure 1).

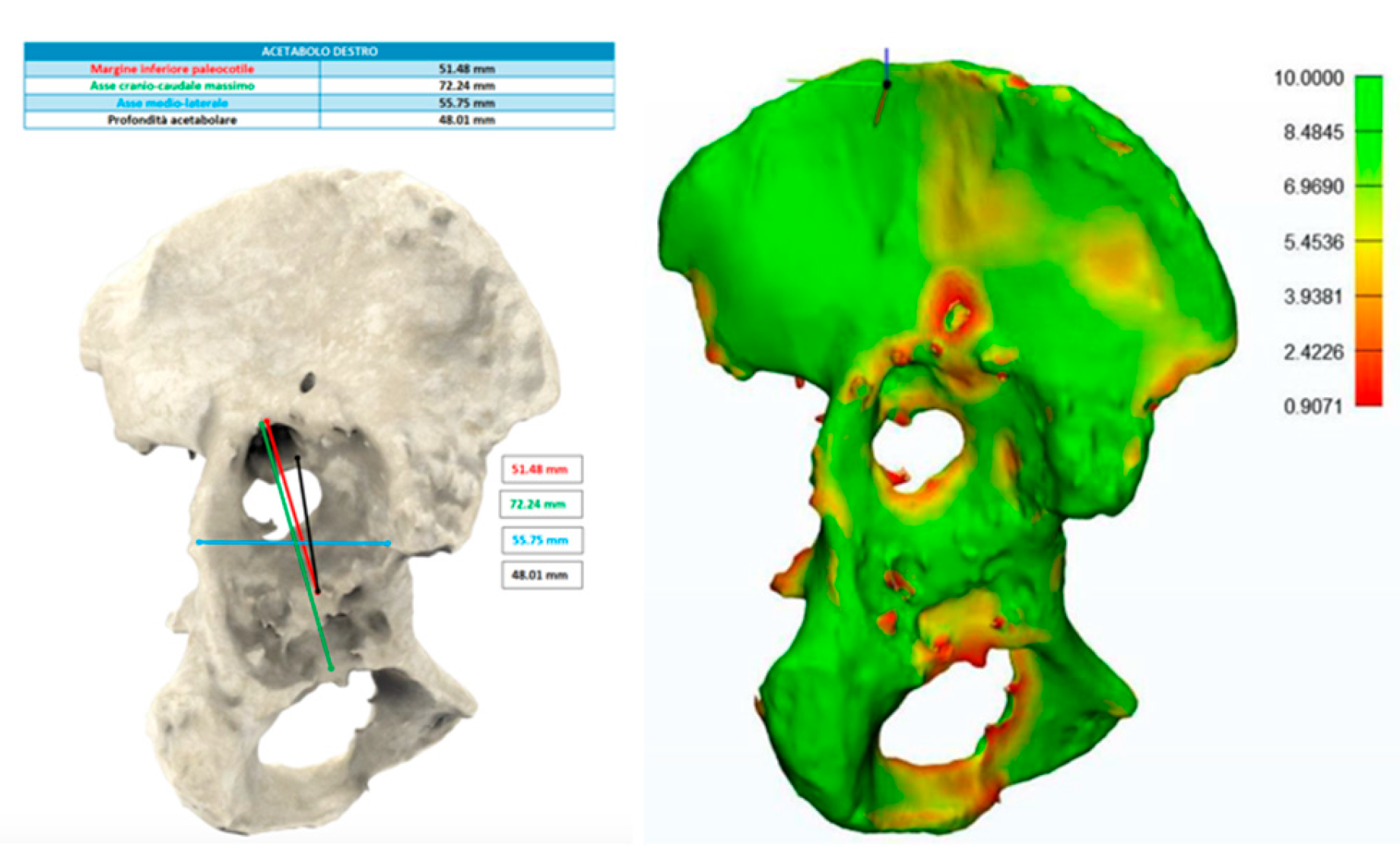

The making of the 3D models arises from a CT examination of the pelvis and lower limbs. All CT images and DICOM data were sent to an external company (Medics srl) to develop a three-dimensional digital model of the pelvis and lower limbs using HA3D ™ technology. Using a computer, the 3D digital model of the pelvis and lower limbs can be rotated by any angle and axially. In addition, a certain amount of bone tissue can be eliminated by the image processing function. Therefore, in this way we were able to identify and separate the different anatomical structures by observing for example the relationship between the acetabulum and the femoral head, the anatomical characteristics of the nerve bundles, and the presence of any implants from multiple angles and directions. It was also possible to obtain various useful information for the purposes of the surgical intervention, including bone thickness, defined on the basis of chromatic variations in a color scale ranging from red (<1 mm) to green (>10 mm); the presence of bone gaps, on which measurements are made in the cranio-caudal, antero-posterior and medial-lateral direction first on the 3D model and subsequently in the operating room; and finally, the presence of osteophytes and the size and orientation of the implants to be revised (

Figure 2).

Postoperative radiographs were evaluated for the presence of radiolucent lines adjacent to the acetabular implant, including any augments, according to DeLee and Charnley [11], indicating mechanical loosening of the components. The prosthetic implant was considered unstable if a radiolucent line with at least 1 mm in width crossed all three acetabular zones, upper third, medial or lower third according to DeLee and Charnley, or if a migration of components could be observed (

Figure 3). The fibrous stability of the cup was characterized by a radiolucent line less than 1 mm in width crossing two of the three acetabular zones. The whole construct was considered stable in the presence of bone growth and if the prosthetic components were in close contact with the pelvic bone in the absence of radiolucent lines in at least two of the three acetabular areas [12]. Loosening was defined by the presence of a change greater than 10° in the component's abduction angle or whether the entire cup moved 6 mm or more on the vertical plane, or on the horizontal plane from its postoperative position [13]. The presence of heterotopic ossification was evaluated according to Brooker classification [14].

2.2. Statistical analysis

The analyses of all the patients were performed using SPSS for Mac (version 16.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois). The categorical data collected were gender, preoperative diagnosis, type of acetabular bone defect, post-operative patient satisfaction, radiological loosening of the acetabular components, radiolucent lines adjacent to the acetabular implant, and/or heterotopic augmentation and ossification. The numerical data collected for the study were age, BMI, HHS values, hip ROM, LLD, and cranial migration of the hip center of rotation. The descriptive statistic was calculated. Statistical significance of improvement in HHS, hip ROM, and LLD values was assessed using the Wilcoxon Two-Tailed Signed Rank Test for the paired sample because the data were not normally distributed. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

In the study period a total of 303 hip arthroplasty revision surgeries were performed in our institution. The study group included 25 patients (20 females - 5 males), mean age 62.9 ± 10.8 years, mean BMI 26.3 ± 5.3 kg. Patients were followed for an average of 13.8 months (± 2.2 months) following the intervention (

Table 1).

All surgeries were performed with a posterolateral approach with patient in lateral decubitus. Mean time of surgery was 206.1 ± 39.5 minutes, blood loss was 463 ± 176.9 ml, hospital stay was 3.7 ± 0.6 days in our operating unit and 13.6 ± 6.5 days in the dedicated rehabilitation therapy department and postoperative complications included 4 dislocations and 2 fistulas (

Table 2).

During the surgery, the implants placed on the 3D model were faithfully replicated on the patient.

Of these 25 patients, 9 underwent revision of both the cup and the stem. Stem removal was performed transfemorally and subsequent synthesis of the greater trochanter using metal cerclages and screws was performed. The remaining 16 patients underwent revision of the cup alone.

A modular multi-hole tantalum cup (Zimmer, Warsaw, Indiana) was used in all patients, with a median diameter of 58.8 (range, 52-66). In 8 patients a TM augment (Zimmer, Warsaw, Indiana) was added, fixed to the pelvic bone with a median number of 3 screws (range, 2 - 6).

In 14 patients a vitamin E-infused Highwall polyethylene insert (E-Poly, Biomet) was cemented in the cup, in 10 a dual mobility metal cup (Avantage, Zimmer) was cemented in the cup, was cemented in the cup and in one patient a Constrained liner (Zimmer, Warsaw, Indiana) was required (

Table 3).

Functional results were evaluated using the Harris Hip Score (HHS), the visual analog scale (VAS); and the Limb Length Discrepancy (

Table 4).

The mean preoperative HHS was 35.9 ± 8.4 points and the postoperative HHS at the final follow-up was 81.2 ± 13.2 points (p < 0.001). Mean VAS decreased from 6.7 ± 1.4 points before surgery to 2.4 ± 1.0 points at final follow-up (p < 0.001). Mean LLD of the operated leg was 1.95 ± 1.23 cm of shortening before surgery and 0.57 ± 0.6 cm of shortening postoperatively (p < 0.001).

The mean vertical position of the center of rotation from the line joining the radiological tears changed from 3.5 ± 1.7 cm before surgery to 1.97 ± 0.65 cm after surgery (P< 0.05). The mean horizontal position of the center changed from 3.9 ± 1.5 cm before surgery to 3.2 ± 0.5 cm after surgery (P< 0.05). The mean acetabular component abduction angle changed 59.7° ± 29.6° before 46° ± 3.9 after surgery (P< 0.05) (

Table 5).

Heterotopic ossification was found in 5 (20%) of the 25 hips. Of these, two showed a Grade I according to Brooker, two a Grade II and one a Grade III. No patient required additional surgery to remove the ossification. The number of patients with lameness decreased from 25 cases before surgery to 4 (low grade) after surgery. The preoperative and postoperative clinical and radiological parameters are listed in

Table 5.

Among the 25 patients operated, 4 presented instability. Three among these required reintervention and one was reduced non surgically. Two patients developed an infection within one-year from the intervention, followed by removal of the mobile prosthetic components (insert and head) with preservation of the osteo-integrated and/or cemented prosthetic components, and subsequent targeted long-term antibiotic therapy.

The 4 reference bone landmarks (Kholer line, Tear drop, Vertical Migration, Ischiatic Lysis) were measured on the RX, CT and 3D model for all 25 cases, and subsequently compared with surgical reports. On the x-ray, medial wall (Kholer line / tear drop) was erroneously reported as affected in 3 cases. Vertical migration was miscalculated in 4 cases and ischiatic lysis was inaccurately reported in 5 cases. On the CT, medial wall was miscalculated in 5 cases, vertical migration in 2 cases, and ischiatic lysis in 4 cases. On the 3D model, the medial wall was erroneously reported as intact in 1 case and misreported as affected in 2 cases. Vertical migration was miscalculated in 2 cases and ischiatic lysis was incorrectly reported in 1 case (

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8).

4. Discussion

In complex revision hip arthroplasties, the presence of acetabular bone loss might change the surgical strategy defined by Paprosky in his world-renowned protocol [9]. Consequently, proper diagnosis and preoperative planning are essential for successful treatment. Often, in this type of surgery, surgeons need to have available, at the same time in the operating room, prosthetic implants of different shapes and sizes. In addition to the difficulty of surgical access, with consequent debridement of the soft tissues, it is often difficult for the surgeon to assess the size of the prosthesis to be implanted.

CT is currently the gold standard in the evaluation of periprosthetic osteolysis and bone loss [15–17]. Modern CT scanners with high resolution acquisition and suppression of metal artifacts are able to provide localization and characterization of bone losses [18]. However, the oblique orientation of the acetabulum and the presence of the acetabular cup can reduce the sensitivity of the CT. In this regard, in the study by Fehring et al. [15] it is shown that the oblique CT reconstruction of 45 degrees allows the frontal visualization of the acetabulum increasing the sensitivity from 73% (with traditional CT reconstructions) to 91% (with reconstruction at 45 degrees) to detect any bone gaps and unrecognized pelvic discontinuities.

Using an accurate 3D printed model of the joint, the surgeon can try to fit different types and sizes of implants in the preoperative setting.

By examining in detail, we found discrepancies between the defects observed on radiography and CT compared to the 3D model. The 3D model offered us a faithful representation of the defect subsequently found in the operating room, easier to evaluate than conventional radiographic or 3D images. Paprosky himself highlighted in his study that about 10% of his patients did not show signs of pelvic discontinuity on standard radiographs later found during surgery [9]. The trial of the implant in a 3D model also allowed us to evaluate the degree of coverage of the cup to favor bone growth, its version to limit the rate of dislocation and also the orientation of the screws and augments towards the areas with increased bone thickness. Knowing the type of trabecular metal (TM) cup to be used in the preoperative phase also allowed us to better evaluate the type of insert, the range of motion, the size of the head, the restraint options, the dual mobility options and other specific options which could be potentially used for the selected implant. From the pre and post-operative evaluations we observed that the hip to be revised had the center of rotation (COR) in an abnormal position, generally displaced cranially and laterally. Nevertheless, despite the complexity of the cases, we were able to restore the COR in an anatomical position, similar to that of the healthy contralateral hip, bringing about an improvement in the function of the pelvic muscles, allowing a reduction in lameness during walking, and significantly reducing limbs length discrepancy. The end result was an early recovery of walking ability, which took place on the same day of the operation, with the help of a walker.

Aprato et al. [19] compared the effectiveness of traditional CT and 3D models for identifying pelvic discontinuity. All patients with clinical confirmation of pelvic discontinuity were identified with both techniques. The most relevant difference found was a higher specificity via the 3D model and, consequently, a higher positive predictive value. This is possible thanks to the absence of artifacts caused by the prosthetic implant and also to the possibility of being able to evaluate the acetabulum without the cup. Tu Q et al. [20] reported the advantages of planning through 3D printing in patients with Crowe IV Congenital Hip Dysplasia: according to the authors, thanks to the improved spatial orientation, the 3D digital anatomical model promotes the surgical process, allowing the surgeon to understand the anatomical structure of the affected hip and its adjacent area, prior to surgery. In fact, by simulating the intervention, corrective methods and preventive measures are taken into consideration in advance for possible problems that may be encountered in the operating room, also benefiting the average surgical time. Li et al. [21] reported in their study a reduction in the average of surgical times and blood losses, to the advantage of a desirable reduction in the risk of infective complications and a more rapid recovery in the post-operative period. The reduction in surgical times would also lead to a reduction in management costs for each individual patient. Ballard et al. [22] analyzed several studies in the literature identifying the cost per minute in the operating room and quantifying the time saved in the operating room using 3D models. According to the author, this method allows an average reduction of 23 minutes per individual patient and a saving of $1’388 per case.

Although our data is also comforting, more time is needed to accurately define the relationship between the costs and benefits of this technology.

This study has some limitations. The sample of patients is very small, because such complex cases are not so common and the data collection lasted only from April 2019 to October 2020.

The second limit is the duration of the follow-up, which is limited to one year. More interventions and long-term follow-up will be needed to understand the real benefits of this method.

5. Conclusions

From our observations, we believe that the use of the 3D model allows to accurately assess, in the preoperative phase, the type of defect, and consequently, the best surgical strategy for complex hip arthroplasty revisions. An improved preoperative evaluation allows better postoperative results, a reduction in the duration of the surgery, with a consequent reduction in infectious complications, in blood loss and also in costs for each single operation. For this reason, we believe that the benefits brought by this technique have a greater impact as compared to the costs, which, in addition, are going to decrease with the spread of this methodology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G., F.L.C. and M.L.; methodology, F.L.C. and M.L.; software, F.L.C. and E.M.; validation, M.L.; formal analysis, F.L.C. and E.M.; investigation, C.M.F. and F.L.C.; resources, A.P. and M.L.; data curation, and M.L, E.M., F.L.C. and G.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.; writing—review and editing, A.P. and F.L.C.; visualization, E.G., V.D.M., F.L.C. and M.L.; supervision, F.L.C. and M.L.; project administration, G.G. and M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practice guidelines. The study protocol for the development of this registry was approved by Ethics Committee of Humanitas Research Hospital (protocol code 618/17).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.Patients signed informed consent regarding storing and publishing their data and photographs for scientifical purposes in an anonymous way.

Data Availability Statement

Data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Supplementary datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Livio Sciutto Foundation for Medical Research. This is a non-profit social organization that recorded in its database the data of the patients included in the study with the previous consent of the patients and respecting the current law on privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

FLC has received financial support for attending symposia and educational programs from Zimmer Biomet. GG has received honoraria for speaking at symposia, financial support for attending symposia and educational programs from Zimmer Biomet and royalties from Zimmer Biomet and Innomed. ML has received a research grant from Italian Ministry of Health (GR-2018- 12367275), financial support for attending symposia, educational programs and post marketing studies from Zimmer Biomet. He is also Scientific Director of the Livio Sciutto Foundation Biomedical Research in Orthopaedics—ONLUS. CMF, AP, VdM, EG, and EM have no conflicts of interest to declare. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Fryhofer GW, Ramesh S, Sheth NP. Acetabular reconstruction in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2020;11:22–8. [CrossRef]

- Maryada VR, Mulpur P, Eachempati KK, Annapareddy A, Badri Narayana Prasad V, Gurava Reddy AV. Pre-operative planning and templating with 3-D printed models for complex primary and revision total hip arthroplasty. Journal of Orthopaedics 2022;34:240–5. [CrossRef]

- Zheng S-N, Yao Q-Q, Mao F-Y, Zheng P-F, Tian S-C, Li J-Y, et al. Application of 3D printing rapid prototyping-assisted percutaneous fixation in the treatment of intertrochanteric fracture. Exp Ther Med 2017;14:3644–50. [CrossRef]

- Yu AW, Duncan JM, Daurka JS, Lewis A, Cobb J. A feasibility study into the use of three-dimensional printer modelling in acetabular fracture surgery. Adv Orthop 2015;2015:617046. [CrossRef]

- Small T, Krebs V, Molloy R, Bryan J, Klika AK, Barsoum WK. Comparison of acetabular shell position using patient specific instruments vs. standard surgical instruments: a randomized clinical trial. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:1030-7. [CrossRef]

- Liang H, Ji T, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Guo W. Reconstruction with 3D-printed pelvic endoprostheses after resection of a pelvic tumour. Bone Joint J 2017;99-B:267–75. [CrossRef]

- La Camera, F.; Loppini, M.; della Rocca, A.; de Matteo, V.; Grappiolo, G. Total Hip Arthroplasty With a Monoblock Conical Stem in Dysplastic Hips: A 20-Year Follow-Up Study. J. Arthroplast. 2020, 35, 3242–3248. [CrossRef]

- Javan R, Ellenbogen AL, Greek N, Haji-Momenian S. A prototype assembled 3D-printed phantom of the glenohumeral joint for fluoroscopic-guided shoulder arthrography. Skeletal Radiol 2019;48:791–802. [CrossRef]

- Paprosky WG, Perona PG, Lawrence JM. Acetabular defect classification and surgical reconstruction in revision arthroplasty. A 6-year follow-up evaluation. J Arthroplasty 1994;9:33–44. [CrossRef]

- Sporer SM, Paprosky WG. Acetabular revision using a trabecular metal acetabular component for severe acetabular bone loss associated with a pelvic discontinuity. J Arthroplasty 2006;21:87–90. [CrossRef]

- DeLee JG, Charnley J. Radiological demarcation of cemented sockets in total hip replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1976:20–32. [CrossRef]

- Weeden SH, Schmidt RH. The use of tantalum porous metal implants for Paprosky 3A and 3B defects. J Arthroplasty 2007;22:151–5. [CrossRef]

- Sporer SM, Paprosky WG. The use of a trabecular metal acetabular component and trabecular metal augment for severe acetabular defects. J Arthroplasty 2006;21:83–6. [CrossRef]

- Brooker AF, Bowerman JW, Robinson RA, Riley LH. Ectopic ossification following total hip replacement. Incidence and a method of classification. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1973;55:1629–32.

- Fehring KA, Howe BM, Martin JR, Taunton MJ, Berry DJ. Preoperative Evaluation for Pelvic Discontinuity Using a New Reformatted Computed Tomography Scan Protocol. J Arthroplasty 2016;31:2247–51. [CrossRef]

- Berry DJ, Lewallen DG, Hanssen AD, Cabanela ME. Pelvic discontinuity in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1999;81:1692–702. [CrossRef]

- Sporer SM, O’Rourke M, Paprosky WG. The treatment of pelvic discontinuity during acetabular revision. J Arthroplasty 2005;20:79–84. [CrossRef]

- Abdelnasser MK, Klenke FM, Whitlock P, Khalil AM, Khalifa YE, Ali HM, et al. Management of pelvic discontinuity in revision total hip arthroplasty: a review of the literature. Hip Int 2015;25:120–6. [CrossRef]

- Aprato A, Olivero M, Iannizzi G, Bistolfi A, Sabatini L, Masse A. Pelvic discontinuity in acetabular revisions: does CT scan overestimate it? A comparative study of diagnostic accuracy of 3D-modeling and traditional 3D CT scan. Musculoskelet Surg 2020;104:171–7. [CrossRef]

- Tu Q, Ding H, Chen H, Shen J, Miao Q, Liu B, et al. Preliminary application of 3D-printed individualised guiding templates for total hip arthroplasty in Crowe type IV developmental dysplasia of the hip. HIP International 2022;32:334–44. [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Chen X, Lin B, Ma Y, Liao JX, Zheng Q. Three-dimensional technology assisted trabecular metal cup and augments positioning in revision total hip arthroplasty with complex acetabular defects. J Orthop Surg Res 2019;14:431. [CrossRef]

- Ballard DH, Mills P, Duszak R, Weisman JA, Rybicki FJ, Woodard PK. Medical 3D Printing Cost-Savings in Orthopedic and Maxillofacial Surgery: Cost Analysis of Operating Room Time Saved with 3D Printed Anatomic Models and Surgical Guides. Acad Radiol 2020;27:1103–13. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).