Submitted:

19 November 2023

Posted:

20 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Power System Operation And Control

2.1. Introduction

-

Electrical energy sources:Various energy sources are available in nature that are used for generation of electrical energy. These sources are classified as renewable energy sources, such as water, sun, wind, etc., and non-renewable energy sources, such as nuclear energy, fuels, etc.

-

Generation system:The generation system primarily consists of two components i.e. generator, which generates a high frequency electric power, and transformer, which transmits this high frequency generated power from one voltage level to another voltage level.

-

Transmission system:Transmission system is a network of transmission lines through which electric power is transferred from generation side to distribution side.

-

Distribution system:Distribution system provides power to all consumers of an area from the bulk power sources. This power is delivered to consumers at desired voltage and frequency ratings from distribution system.

2.2. Operation and control

- 1.

- AC generators are easier to use in comparison to DC generators.

- 2.

- AC voltage level transformation is easier, offering excellent flexibility of various voltage levels during generation, transmission, and distribution.

- 3.

- Commonly used AC motors are easier to operate and more cost-effective than DC motors.

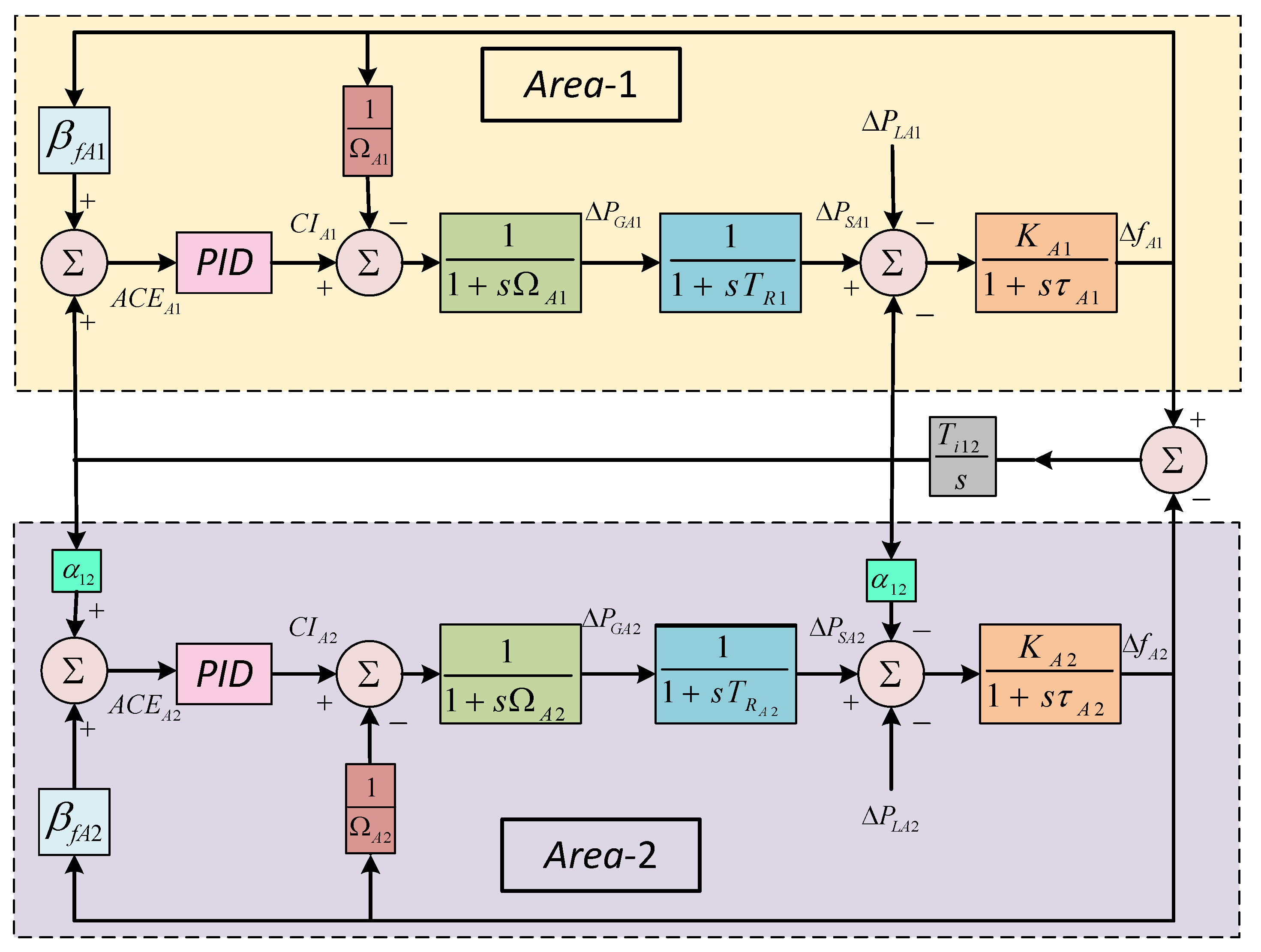

3. Illustration of automatic generation control for considered two area power system

3.1. Automatic generation control

3.2. Framework of two area power system under consideration

4. Problem Formulation

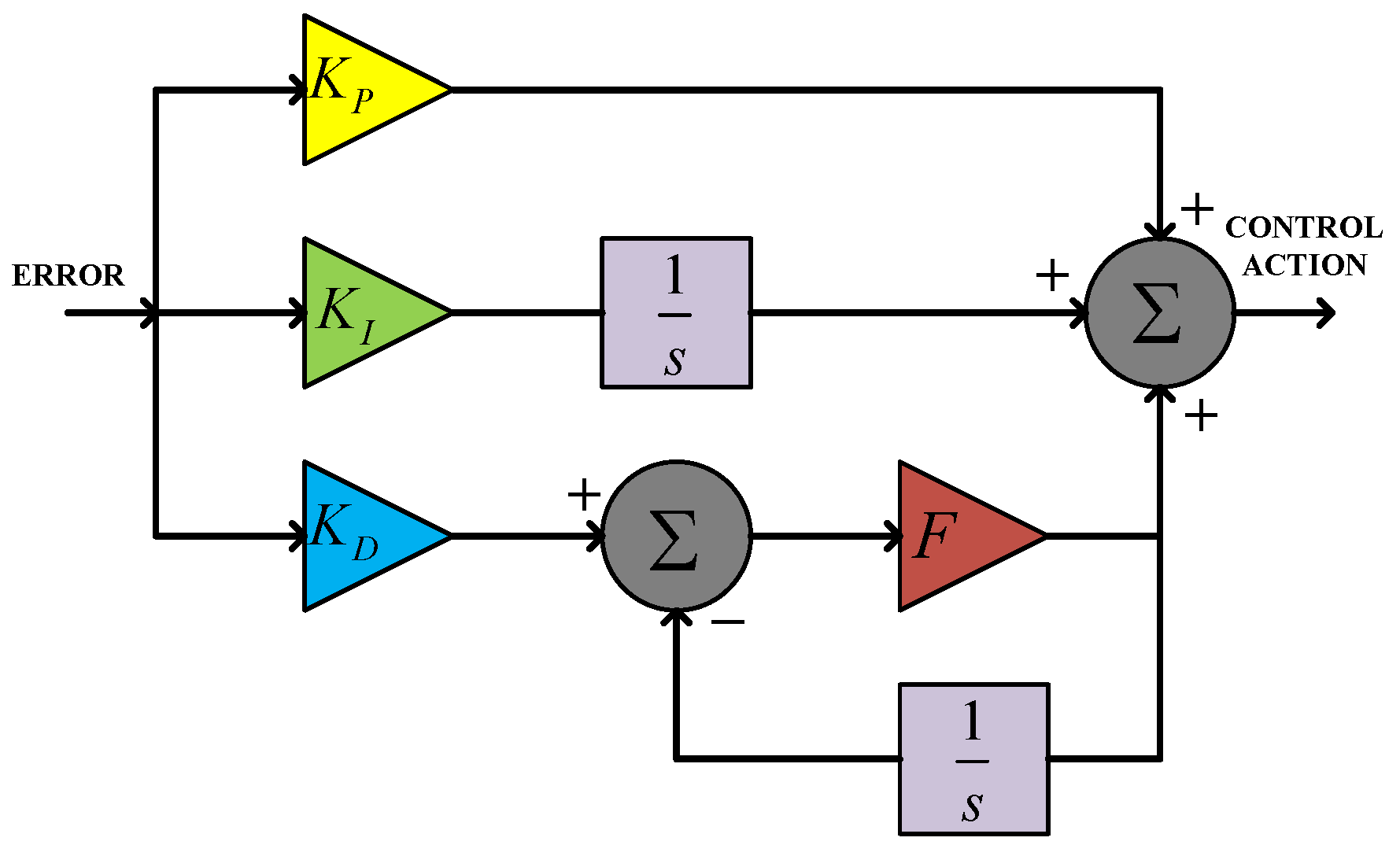

4.1. Design of controller

4.2. Construction of objective function

5. SMART method

6. Jaya Algorithm

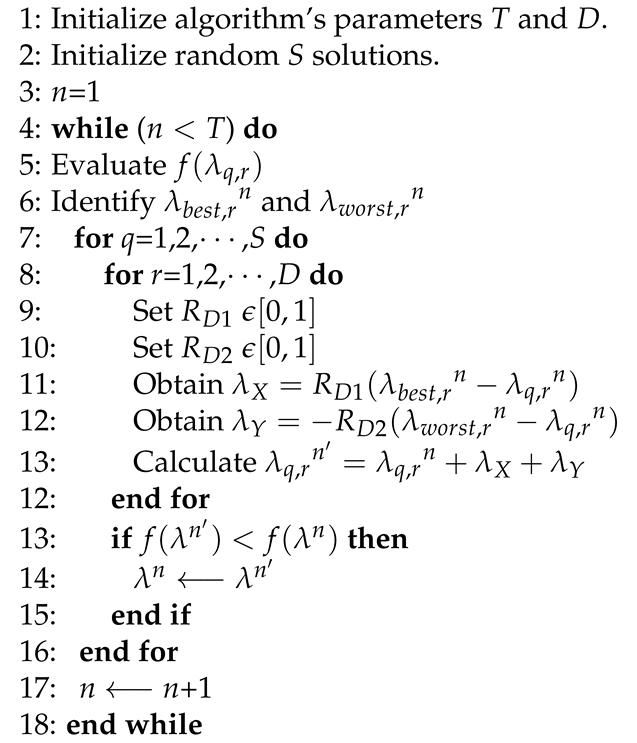

| Algorithm 1 Pseudo-code for Jaya algorithm |

|

7. Results And Discussions

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendices

| Appendix A: Parameters of two-area interconnected power system | |

| Frequency | Hz; |

| Frequency bias factors | , p.u. Mw/Hz; |

| Speed regulating constants for governors | , Hz/p.u.; |

| Time constants for turbine | , s; |

| System gains | , Hz/p.u. Mw; |

| Torque co-efficient for synchronization | p.u.; |

| Area-1 to area-2 tie-line ratio | . |

| Appendix B: Constraints for controller parameters | |

| Filter gain | ; . |

| Integral gain | ; ; |

| Proportional gain | ; ; |

| Derivative gain | ; ; |

References

- Ullah, K.; Basit, A.; Ullah, Z.; Albogamy, F.R.; Hafeez, G. Automatic generation control in modern power systems with wind power and electric vehicles. Energies 2022, 15, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Qiao, S.; Liu, Z. A survey on load frequency control of multi-area power systems: Recent challenges and Strategies. Energies 2023, 16, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, R.K.; Gorripotu, T.S.; Panda, S. Automatic generation control of multi-area power systems with diverse energy sources using teaching learning based optimization algorithm. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal 2016, 19, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Majidi, S.D.; Altai, H.D.S.; Lazim, M.H.; Al-Nussairi, M.K.; Abbod, M.F.; Al-Raweshidy, H.S. Bacterial Foraging Algorithm for a Neural Network Learning Improvement in an Automatic Generation Controller. Energies 2023, 16, 2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kothari, D.P.; others. Recent philosophies of automatic generation control strategies in power systems. IEEE transactions on power systems 2005, 20, 346–357. [Google Scholar]

- Rout, U.K.; Sahu, R.K.; Panda, S. Design and analysis of differential evolution algorithm based automatic generation control for interconnected power system. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 2013, 4, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chown, G.A.; Hartman, R.C. Design and experience with a fuzzy logic controller for automatic generation control (AGC). IEEE Transactions on power systems 1998, 13, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevrani, H.; Hiyama, T. Intelligent automatic generation control. CRC press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Golpira, H.; Bevrani, H. Application of GA optimization for automatic generation control design in an interconnected power system. Energy Conversion and Management 2011, 52, 2247–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iracleous, D.; Alexandridis, A. A multi-task automatic generation control for power regulation. Electric Power Systems Research 2005, 73, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, K.; Bhatti, T. Automatic generation control of single area power system with multi-source power generation. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part A: Journal of Power and Energy 2008, 222, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossaiin, M.; Takahashi, T.; Rabbani, M.; Sheikh, M.; Anower, M. Fuzzy-proportional integral controller for an AGC in a single area power system. 2006 International Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering. IEEE; 2006; pp. 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Dabur, P.; Yadav, N.K.; Avtar, R. Matlab design and simulation of AGC and AVR for single area power system with fuzzy logic control. International Journal of Soft Computing and Engineering 2012, 1, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Temiz, A.; Guven, A.N. An AGC Algorithm for Multi-Area Power Systems in Network Splitting Conditions. 2023 IEEE PES GTD International Conference and Exposition (GTD). IEEE; 2023; pp. 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Salim, N.; Zambri, N.A. Automatic Generation Control System: The Impact of Battery Energy Storage in Multi Area Network. International Journal of Integrated Engineering 2023, 15, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.A.; Mokhlis, H.; Mansor, N.N.; Illias, H.A.; Usama, M.; Daraz, A.; Wang, L.; Awalin, L.J. Load Frequency Control using Golden Eagle Optimization for Multi-Area Power System Connected Through AC/HVDC Transmission and Supported with Hybrid Energy Storage Devices. IEEE Access 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shouran, M.; Anayi, F.; Packianather, M.; Habil, M. Different fuzzy control configurations tuned by the bees algorithm for LFC of two-area power system. Energies 2022, 15, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, Y. A novel CFFOPI-FOPID controller for AGC performance enhancement of single and multi-area electric power systems. ISA transactions 2020, 100, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, N.; Bhatti, T.; Verma, A.; Nasiruddin, I. AGC of two area power system based on different power output control strategies of thermal power generation. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2017, 33, 2040–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingkang, L.; Hengjun, Z.; Yuyun, L. Genetic algorithm optimization for AGC of multi-area power systems. 2002 IEEE Region 10 Conference on Computers, Communications, Control and Power Engineering. TENCOM’02. Proceedings. IEEE; 2002; 3, pp. 1818–1821. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, P.; Roy, R.; Ghoshal, S. Optimized multi area AGC simulation in restructured power systems. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2010, 32, 311–322. [Google Scholar]

- Daraz, A.; Malik, S.A.; Haq, I.U.; Khan, K.B.; Laghari, G.F.; Zafar, F. Modified PID controller for automatic generation control of multi-source interconnected power system using fitness dependent optimizer algorithm. PloS one 2020, 15, e0242428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.H.; Khan, N.M.; Mansoor, M.; Sanfilippo, F. Optimal Tuning of PID Controller for Boost Converter using Meta-Heuristic Algorithm for Renewable Energy Applications.

- Rajeshwaran, S.; Kumar, C.; Ganapathy, K. Hybrid Optimization Based PID Controller Design for Unstable System. Intelligent Automation & Soft Computing 2023, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Azegmout, M.; Mjahed, M.; El Kari, A.; Ayad, H. New Meta-heuristic-Based Approach for Identification and Control of Stable and Unstable Systems. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF COMPUTERS COMMUNICATIONS & CONTROL 2023, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Alahakoon, S.; Roy, R.B.; Arachchillage, S.J. Optimizing Load Frequency Control in Standalone Marine Microgrids Using Meta-Heuristic Techniques. Energies 2023, 16, 4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.P.; Raut, U.; Gaur, A.P.; Swain, S.; Chauhan, S. Particle Swarm Optimization and Genetic Algorithms for PID Controller Tuning. 2023 5th International Conference on Smart Systems and Inventive Technology (ICSSIT). IEEE, 2023, pp. 189–194.

- Duarte-Forero, J.; Obregón-Quiñones, L.; Valencia-Ochoa, G. Comparative analysis of intelligence optimization algorithms in the thermo-economic performance of an energy recovery system based on organic rankine cycle. Journal of Energy Resources Technology 2021, 143, 112101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, Y.K.; Bhatt, R. BF-PSO optimized PID controller design using ISE, IAE, IATE and MSE error criteria. International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer Engineering & Technology (IJARCET) 2013, 2, 2333–2336. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Halim, H.A.; Othman, E.; Sakr, A.; Zaki, A.; Abouelsoud, A. A Comparative Study of Intelligent Control System Tuning Methods for an Evaporator based on Genetic Algorithm. International Journal of Applied Information Systems 2017, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surjan, R. Design of fixed structure optimal robust controller using genetic algorithm and particle swarm optimization. Int. J. Engineering and Advanced Technology 2012, 2, 187–190. [Google Scholar]

- Zahir, A.M.; Alhady, S.S.N.; Wahab, A.; Ahmad, M. Objective functions modification of GA optimized PID controller for brushed DC motor. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering 2020, 10, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousakazemi, S.M.H. Comparison of the error-integral performance indexes in a GA-tuned PID controlling system of a PWR-type nuclear reactor point-kinetics model. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2021, 132, 103604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwanoko, Y.; Habibi, F.; Purwanto, H.; Swastika, I.; Hudha, M. The smart method to support a decision based on multi attributes identification. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2018, 434, 012037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonen, T. Modern power system analysis; CRC Press, 2013.

- Chakrabarti, A.; Halder, S. Power system analysis: operation and control; PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd., 2022.

- Sivanagaraju, S. Power system operation and control; Pearson Education India, 2009.

- Ali, A.; Biru, G.; Banteyirga, B. Fuzzy Logic-Based AGC and AVR for Four-Area Interconnected Hydro Power System. Electric Power Systems Research 2023, 224, 109494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumal, S.; others. AGC and AVR of Interconnected Thermal Power System while considering the effect of GRC’s. Int. J. Soft Comput. Eng.(IJSCE) 2012, 2, 2117–2126. [Google Scholar]

- Masrur, H.; Ferdoush, A.; Rabbani, M.G. Automatic Generation Control of two area power system with optimized gain parameters. 2015 International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Information Communication Technology (ICEEICT), 2015, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Gopi, P.; Reddy, P.L. A Critical review on AGC strategies in interconnected power system. IET Chennai fourth international conference on sustainable energy and intelligent systems (SEISCON 2013). IET, 2013, pp. 85–92.

- Karnavas, Y.; Papadopoulos, D. AGC for autonomous power system using combined intelligent techniques. Electric power systems research 2002, 62, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Awami, A.T. Control-based Economic Dispatch Augmented by AGC for Operating Renewable-rich Power Grids. 2019 IEEE 10th GCC Conference & Exhibition (GCC). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–5.

- Krishna, P.J.; Meena, V.P.; Singh, V.P.; Khan, B. Rank-Sum-Weight Method Based Systematic Determination of Weights for Controller Tuning for Automatic Generation Control. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 68161–68174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debs, A.S. Automatic Generation Control. In Modern Power Systems Control and Operation; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1988; pp. 203–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oonsivilai, A.; Marungsri, B. Optimal PID tuning for AGC system using adaptive Tabu search. ACE 2007, 1, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mohapatra, T.K.; Sahu, B.K. Design and implementation of SSA based fractional order PID controller for automatic generation control of a multi-area, multi-source interconnected power system. 2018 Technologies for Smart-City Energy Security and Power (ICSESP). IEEE, 2018, pp. 1–6.

- Krishna, P.; Meena, V.; Singh, V.; Khan, B. Rank-sum-weight method based systematic determination of weights for controller tuning for automatic generation control. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 68161–68174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awouda, A.E.A.; Mamat, R.B. Refine PID tuning rule using ITAE criteria. 2010 The 2nd International conference on computer and automation engineering (ICCAE). IEEE, 2010, Vol. 5, pp. 171–176.

- Chen, G.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S. An improved ACO algorithm optimized fuzzy PID controller for load frequency control in multi area interconnected power systems. IEEE Access 2019, 8, 6429–6447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alinezhad, A.; Khalili, J.; Alinezhad, A.; Khalili, J. SMART method. New methods and applications in multiple attribute decision making (MADM). 2019, pp. 1–7.

- Fahlepi, R. Decision support systems employee discipline identification using the simple multi attribute rating technique (smart) method. Journal of Applied Engineering and Technological Science (JAETS) 2020, 1, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R. Jaya: A simple and new optimization algorithm for solving constrained and unconstrained optimization problems. International Journal of Industrial Engineering Computations 2016, 7, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Houssein, E.H.; Gad, A.G.; Wazery, Y.M. Jaya algorithm and applications: A comprehensive review. Metaheuristics and Optimization in Computer and Electrical Engineering 2021, 3–24. [Google Scholar]

| Attributes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative |

() 40% |

() 40% |

() 20% |

| Highest | Highest | Moderately high | |

| Moderate | Moderate | Extremely high | |

| High | High | Moderate | |

| Attributes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative |

() 40% |

() 40% |

() 20% |

| 100 | 100 | 70 | |

| 50 | 50 | 90 | |

| 60 | 60 | 50 | |

| Attributes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative |

() 0.4 |

() 0.4 |

() 0.2 |

| 1 | 1 | 0.66 | |

| 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.89 | |

| 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.44 | |

| Attributes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative |

() 0.4 |

() 0.4 |

() 0.2 |

Cumulative scores |

| 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.132 | 0.93 | |

| 0.176 | 0.176 | 0.178 | 0.53 | |

| 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.088 | 0.528 | |

| Attributes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative |

() 0.4 |

() 0.4 |

() 0.2 |

Cumulative scores |

Normalized cumulative scores |

| 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.132 | 0.93 | 0.467 | |

| 0.176 | 0.176 | 0.178 | 0.53 | 0.266 | |

| 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.088 | 0.528 | 0.265 | |

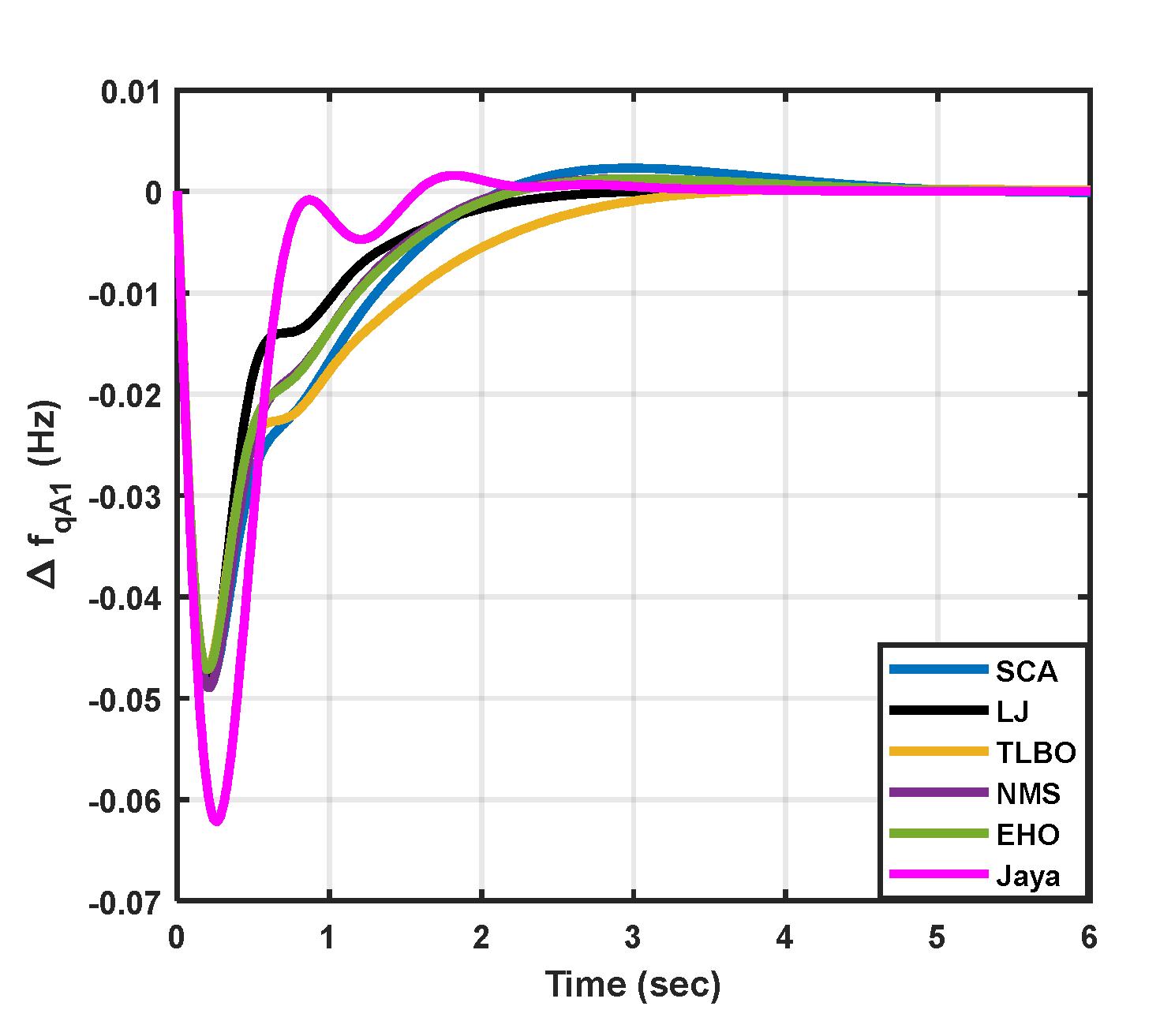

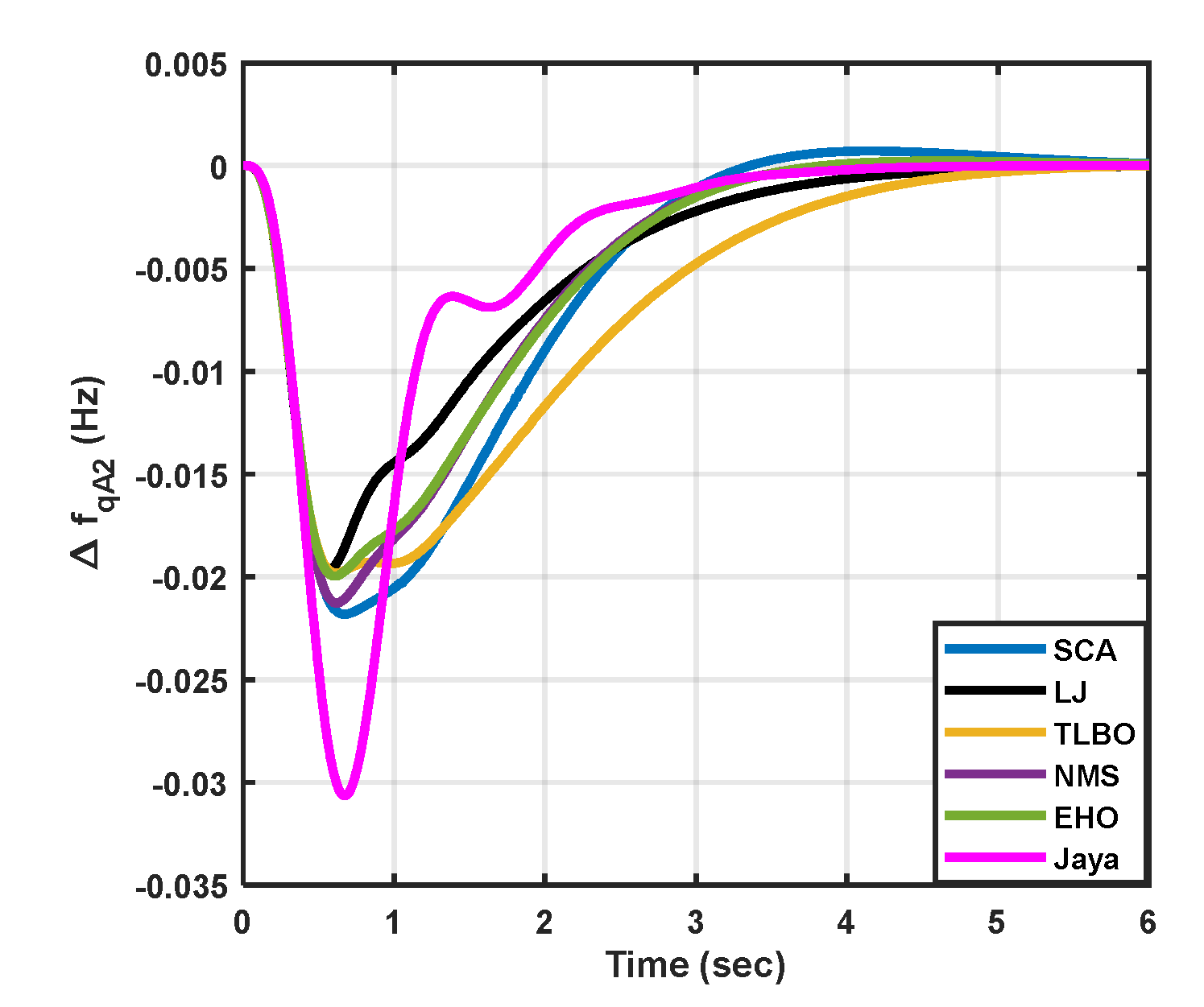

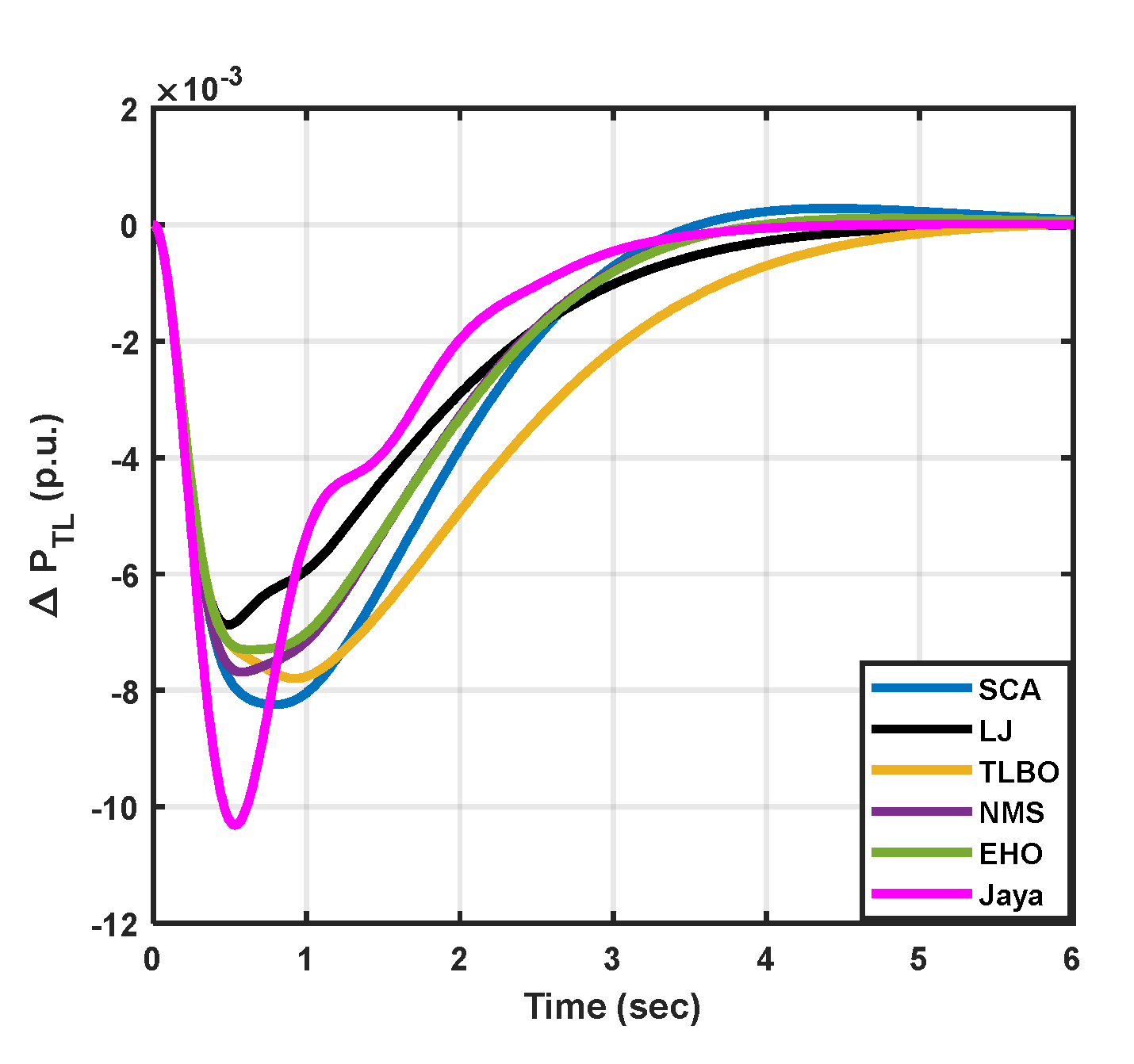

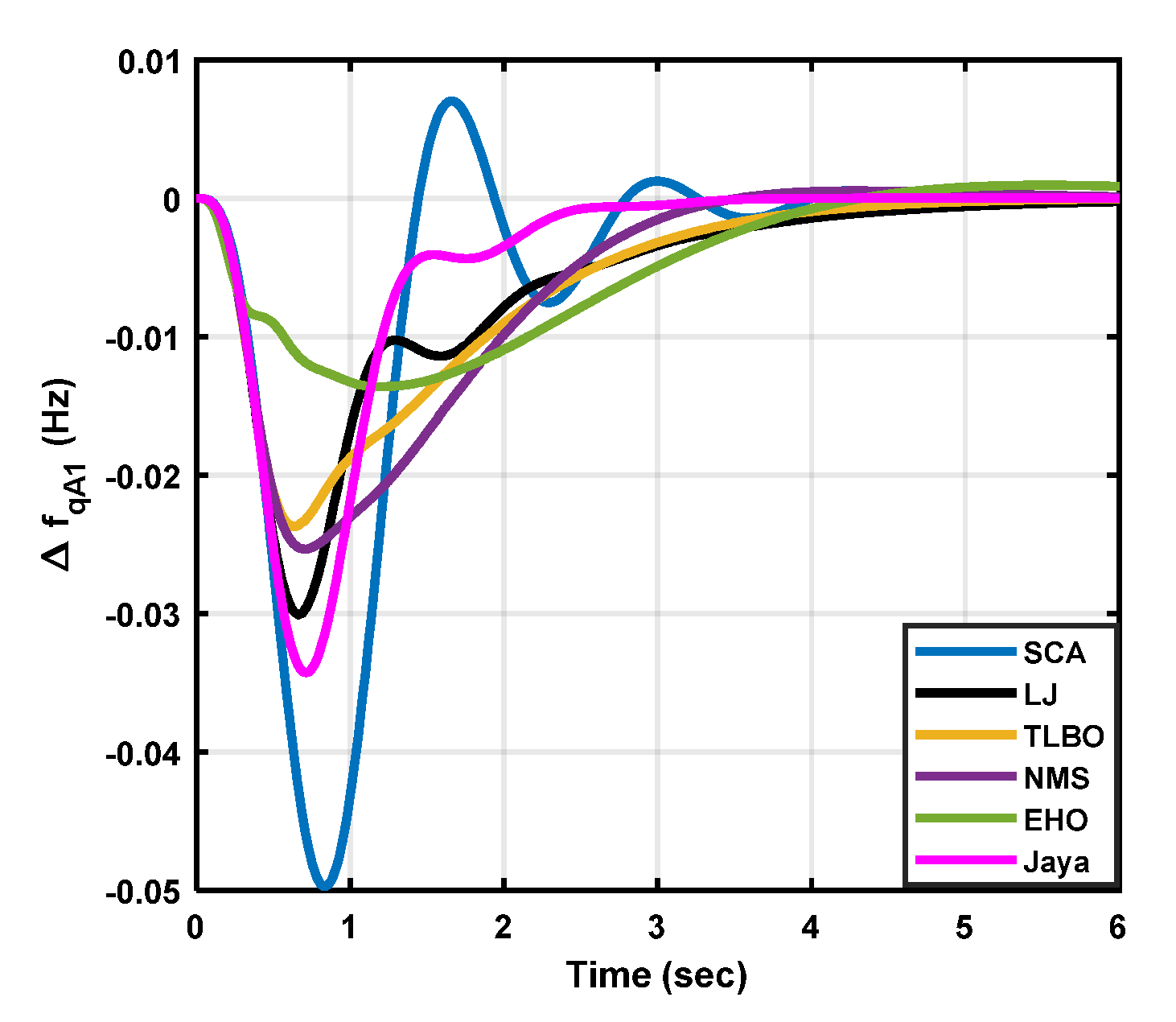

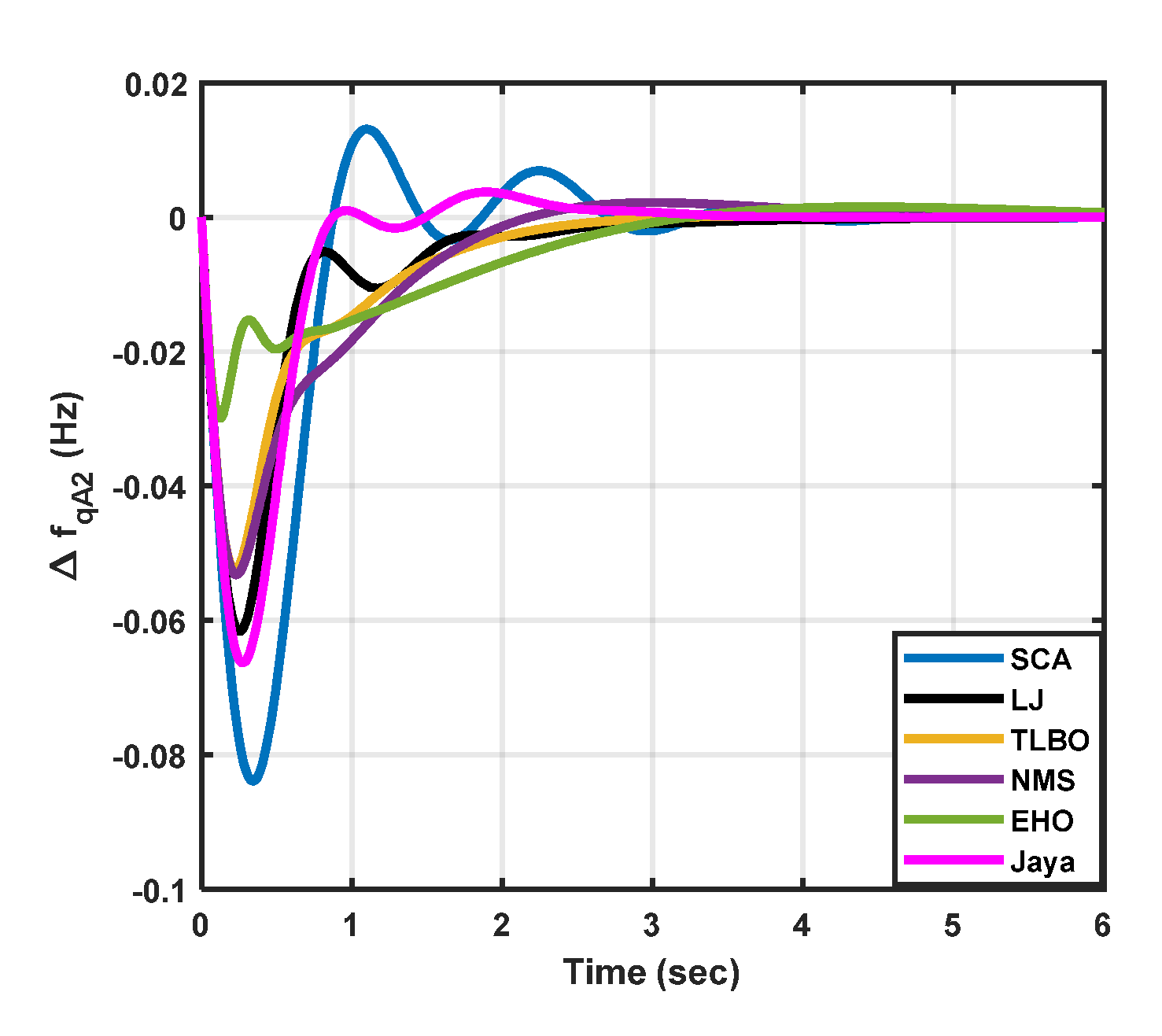

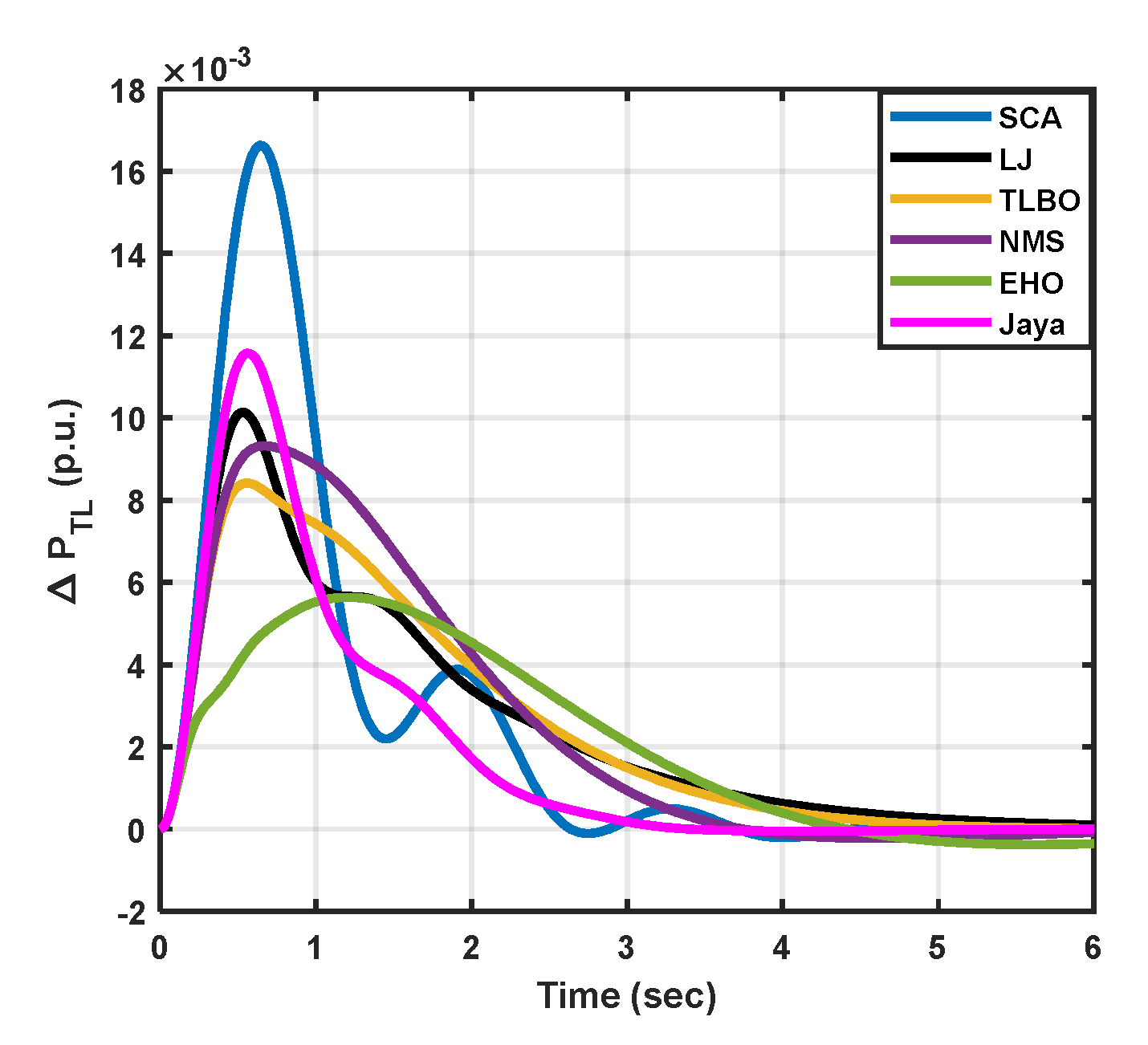

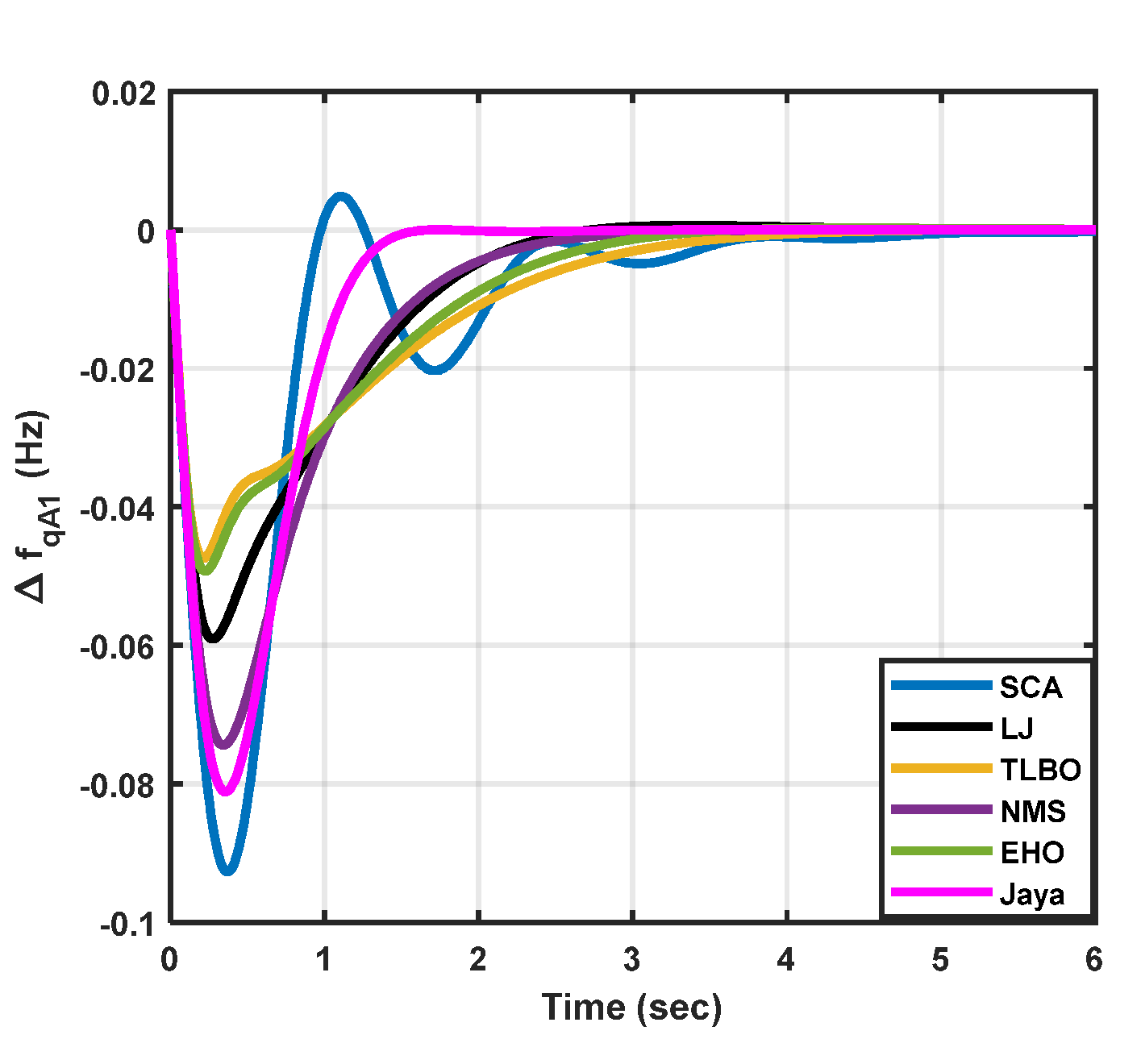

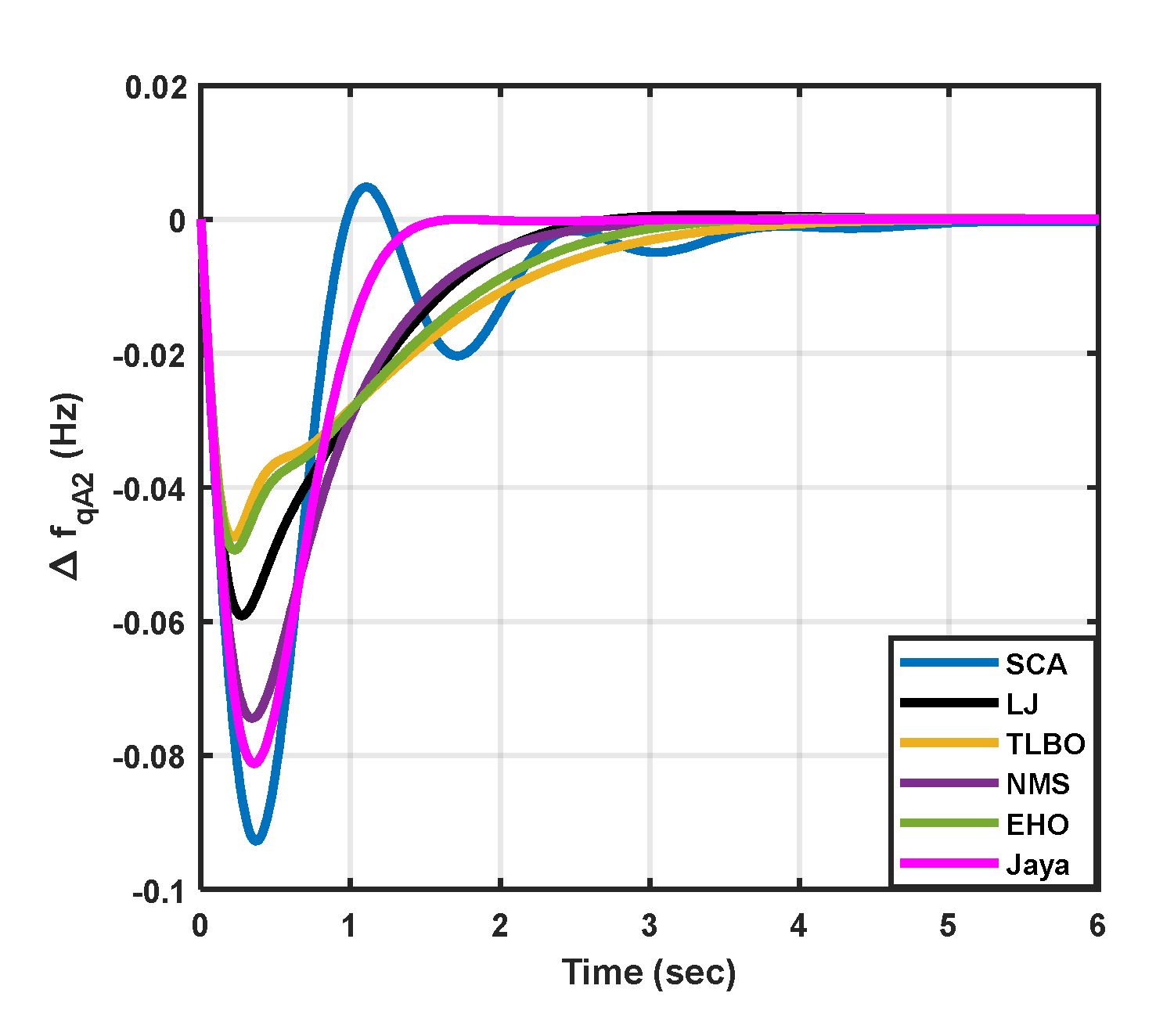

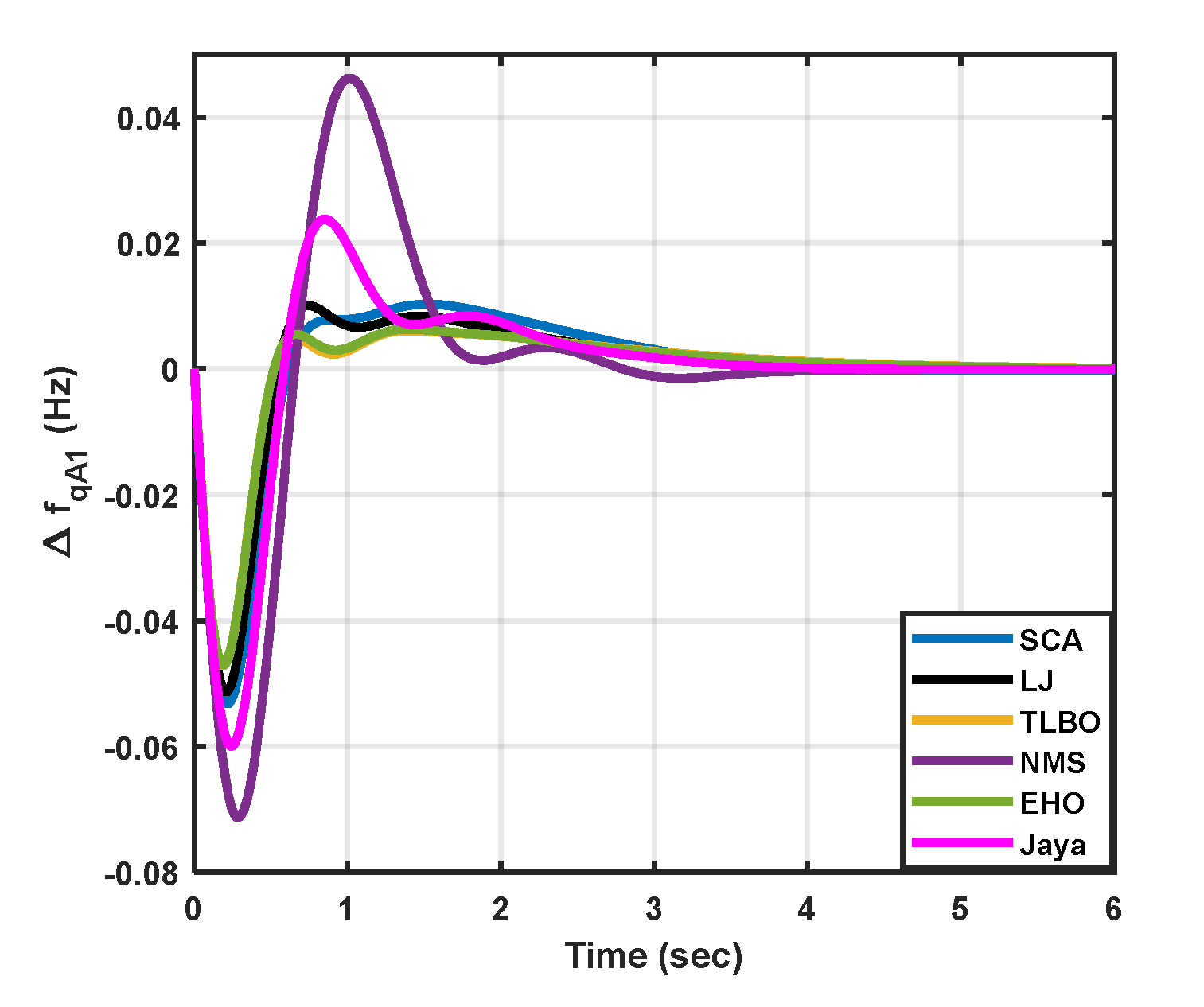

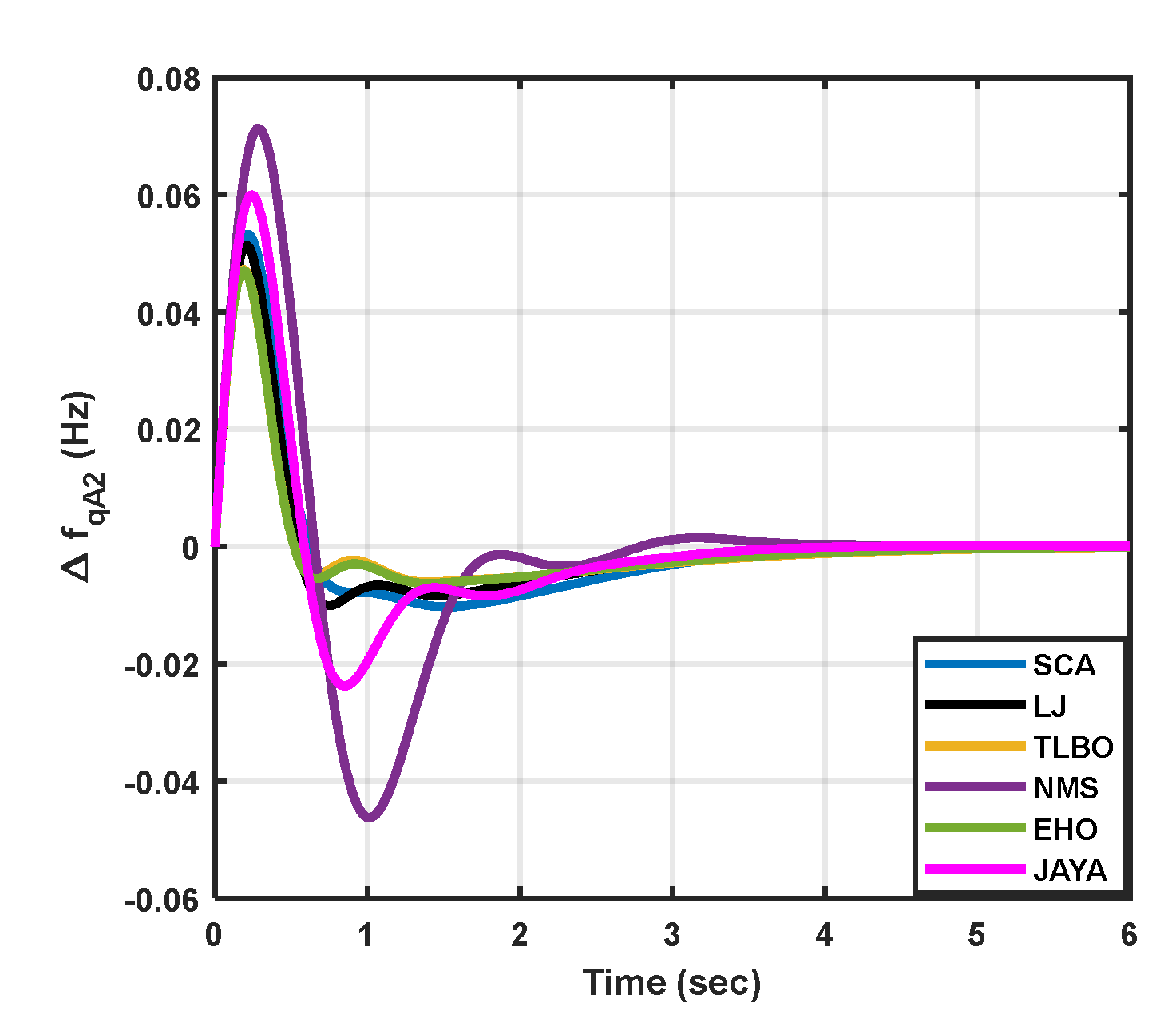

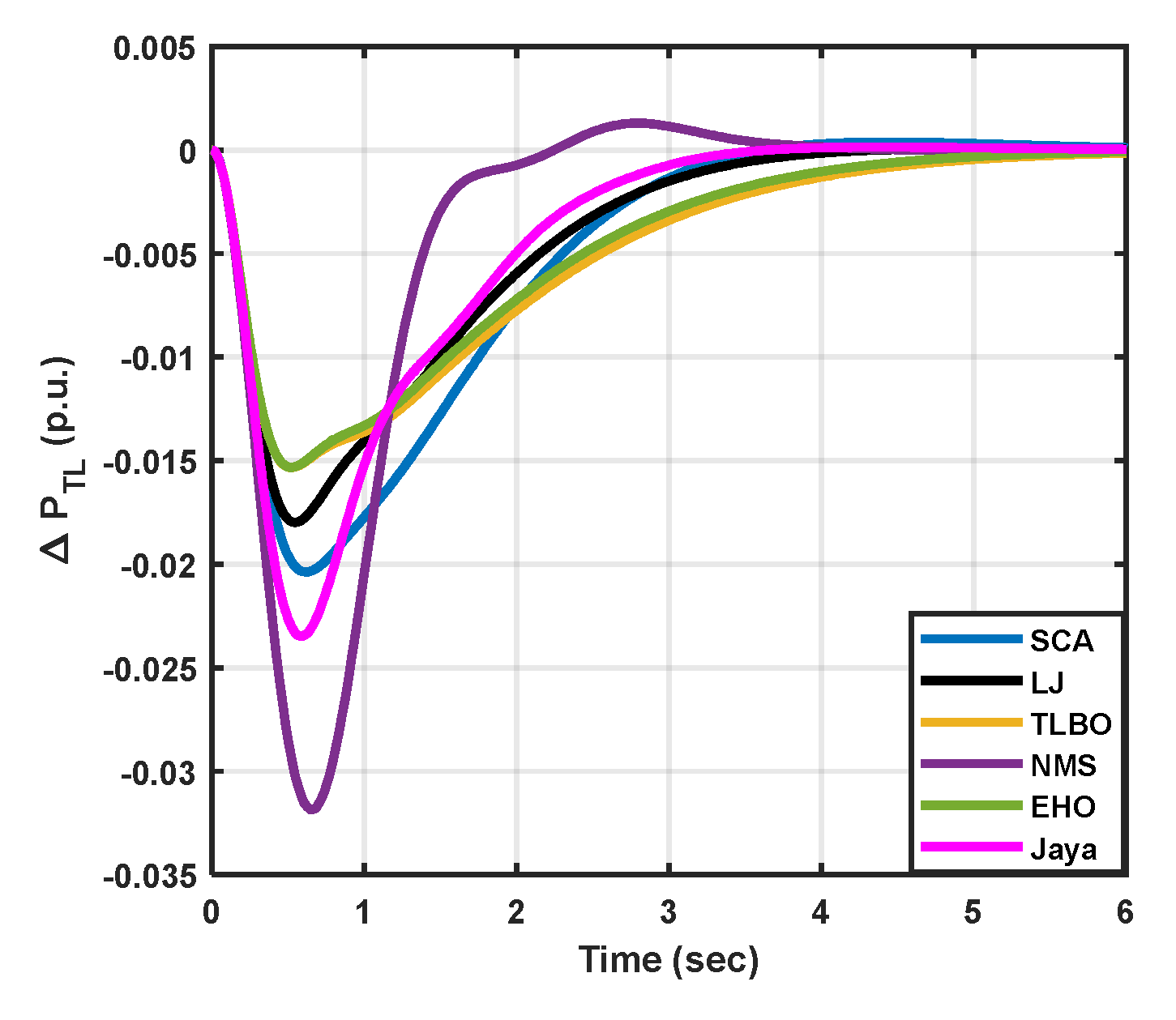

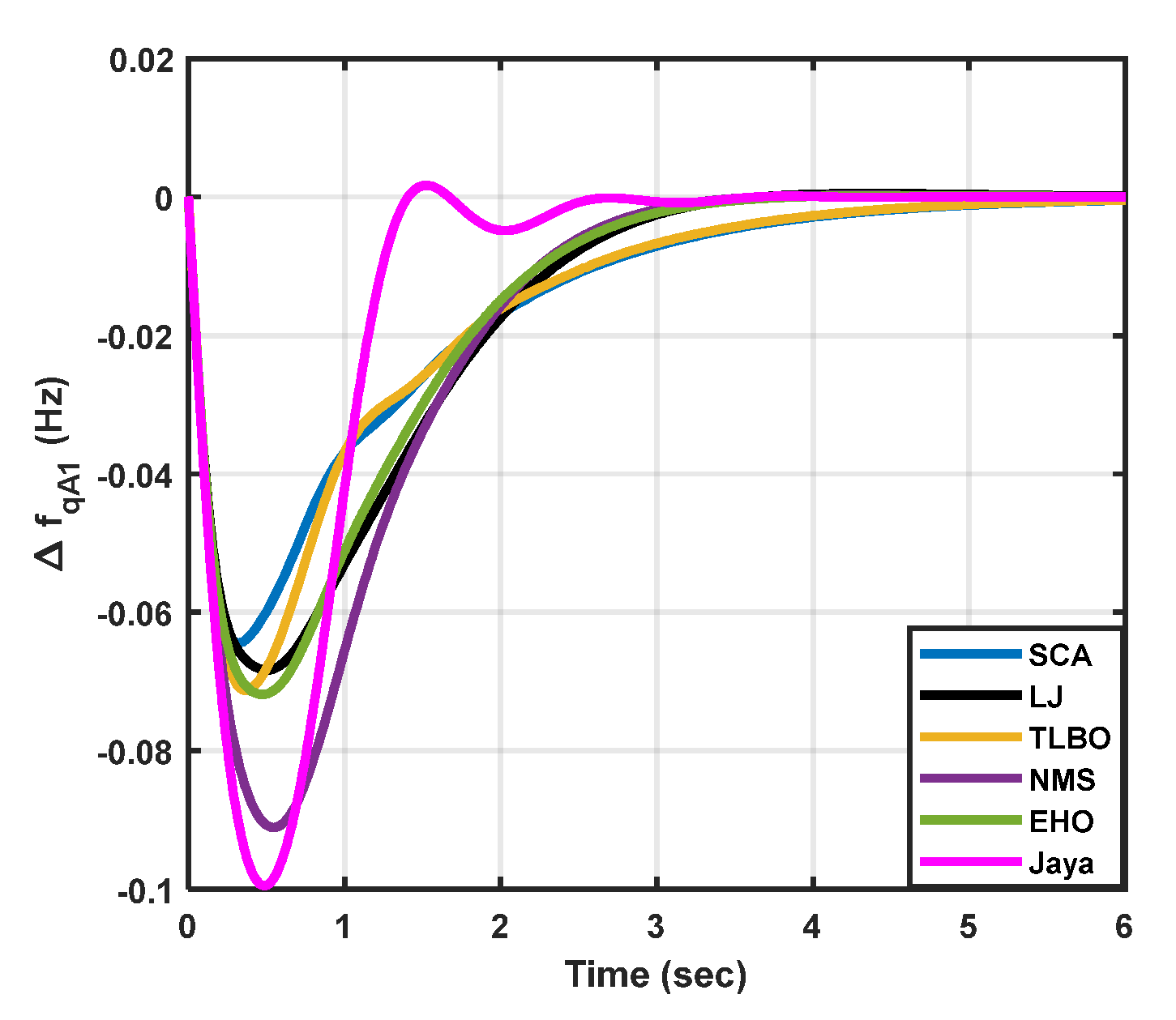

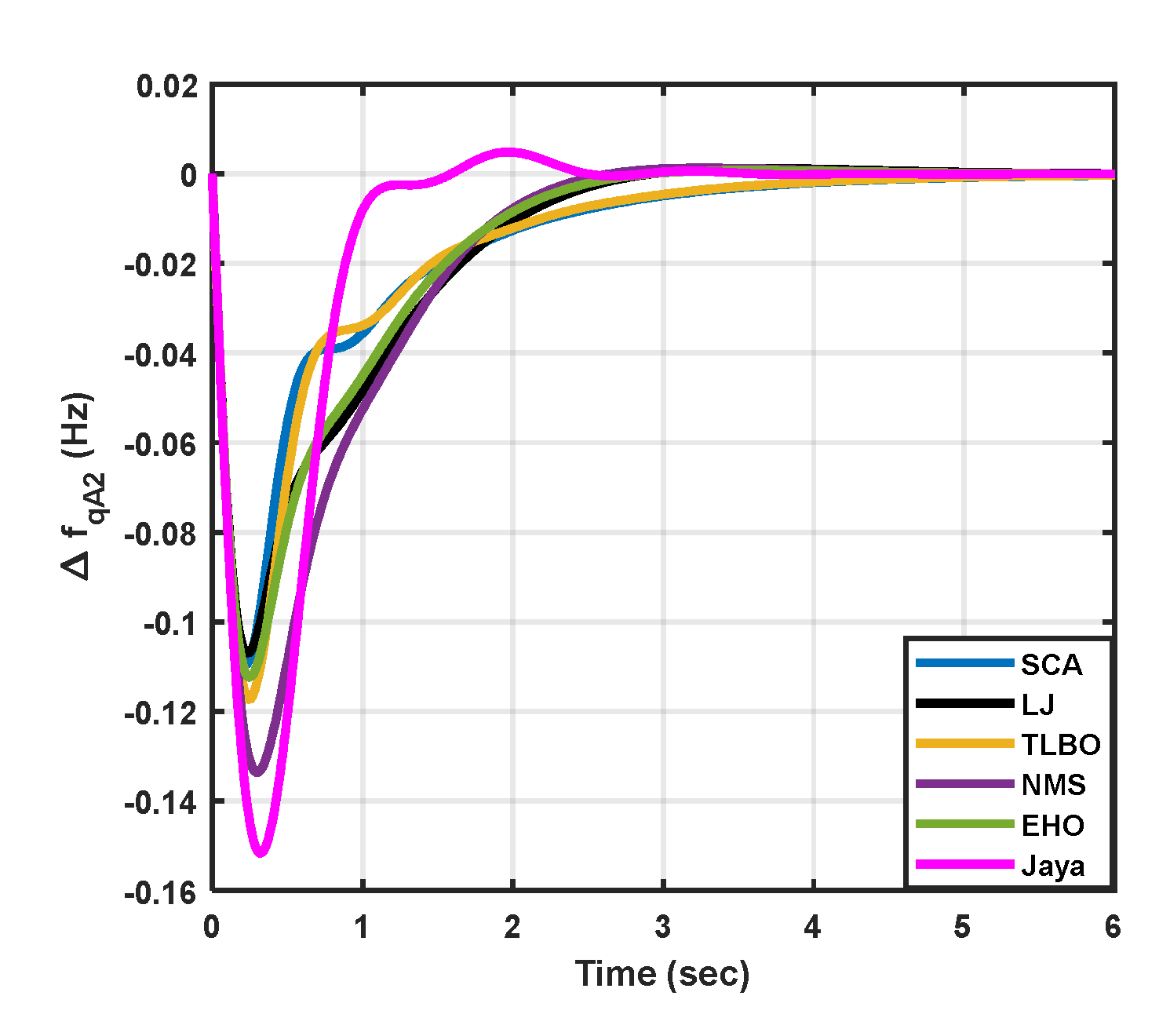

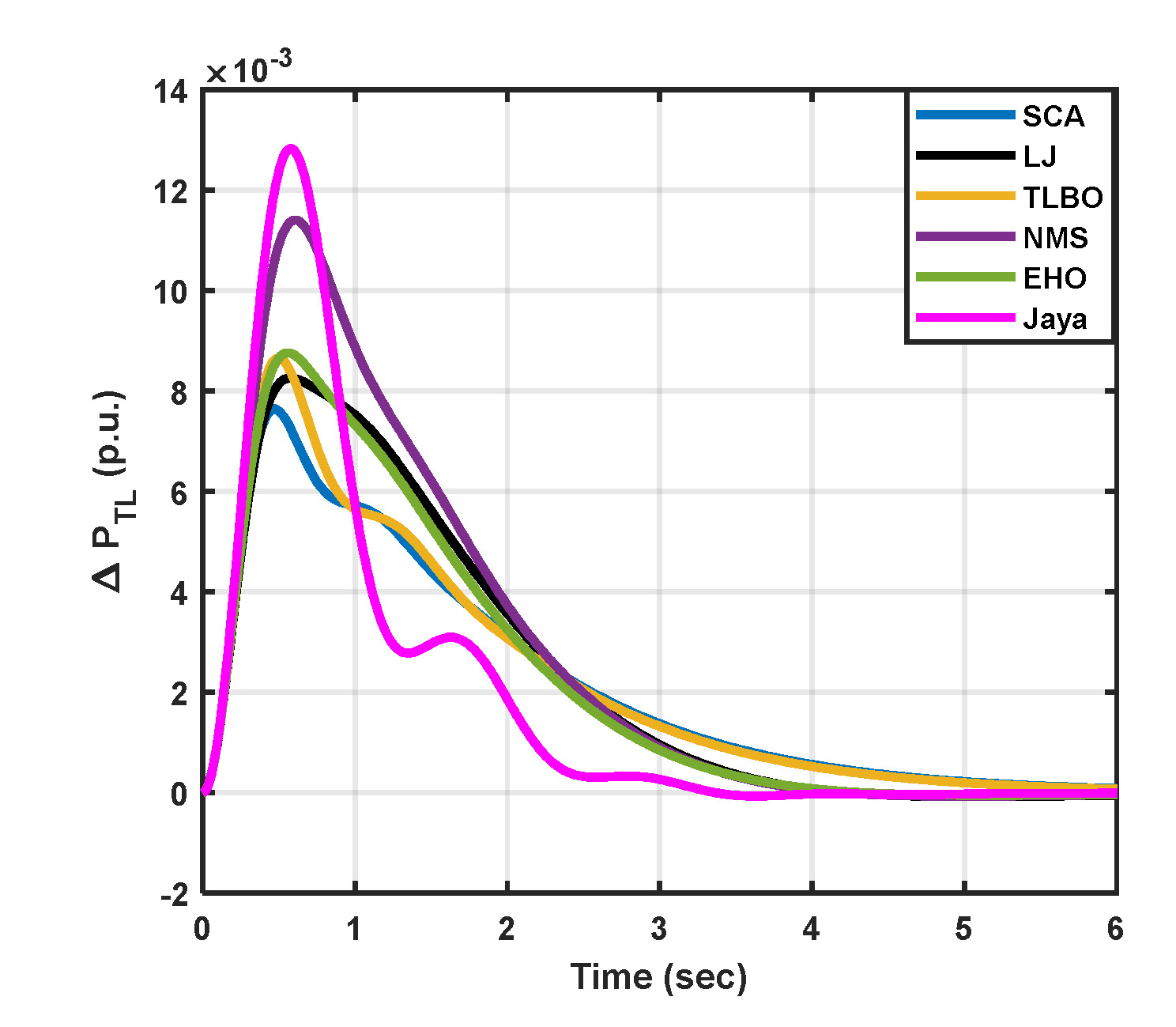

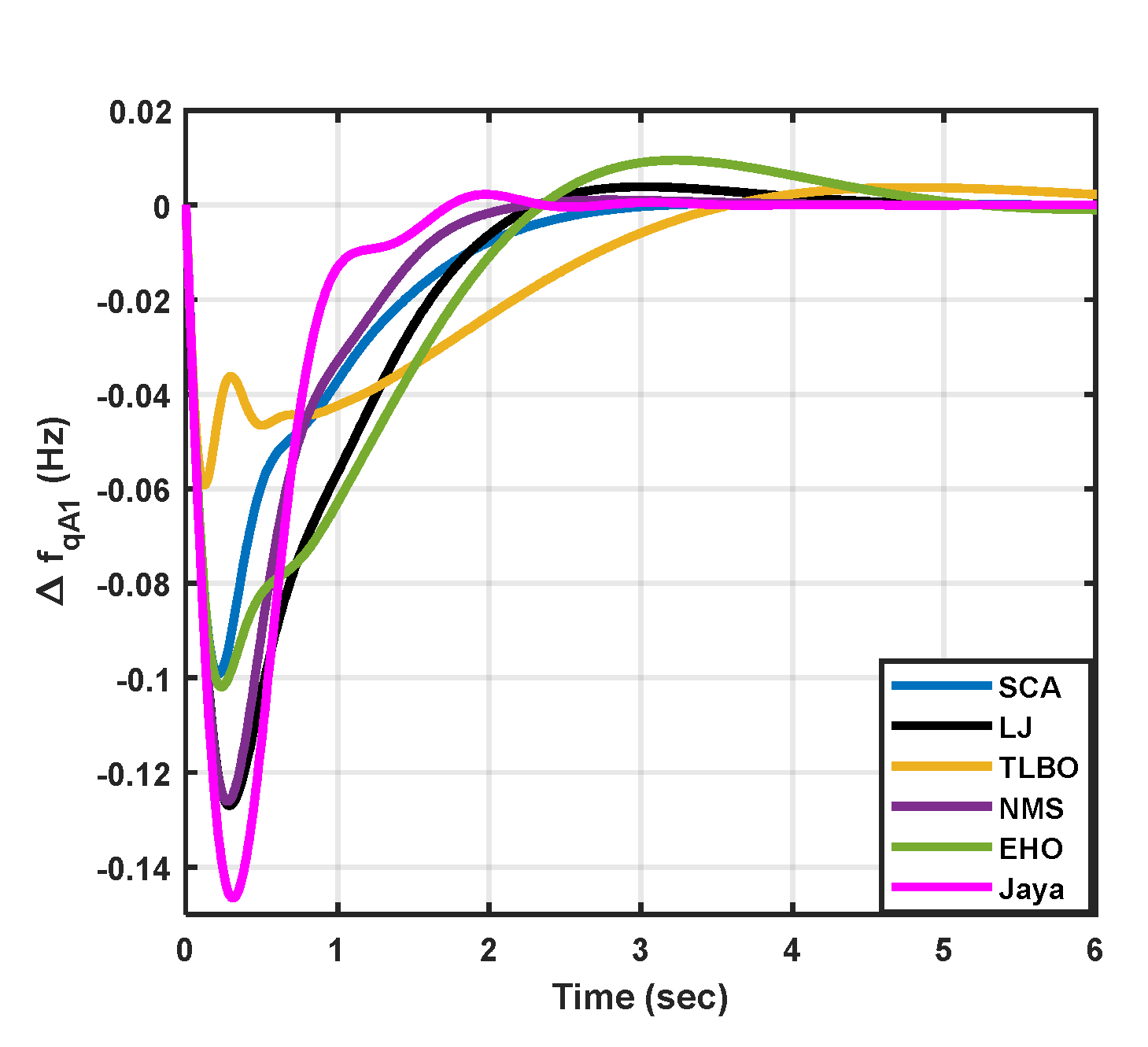

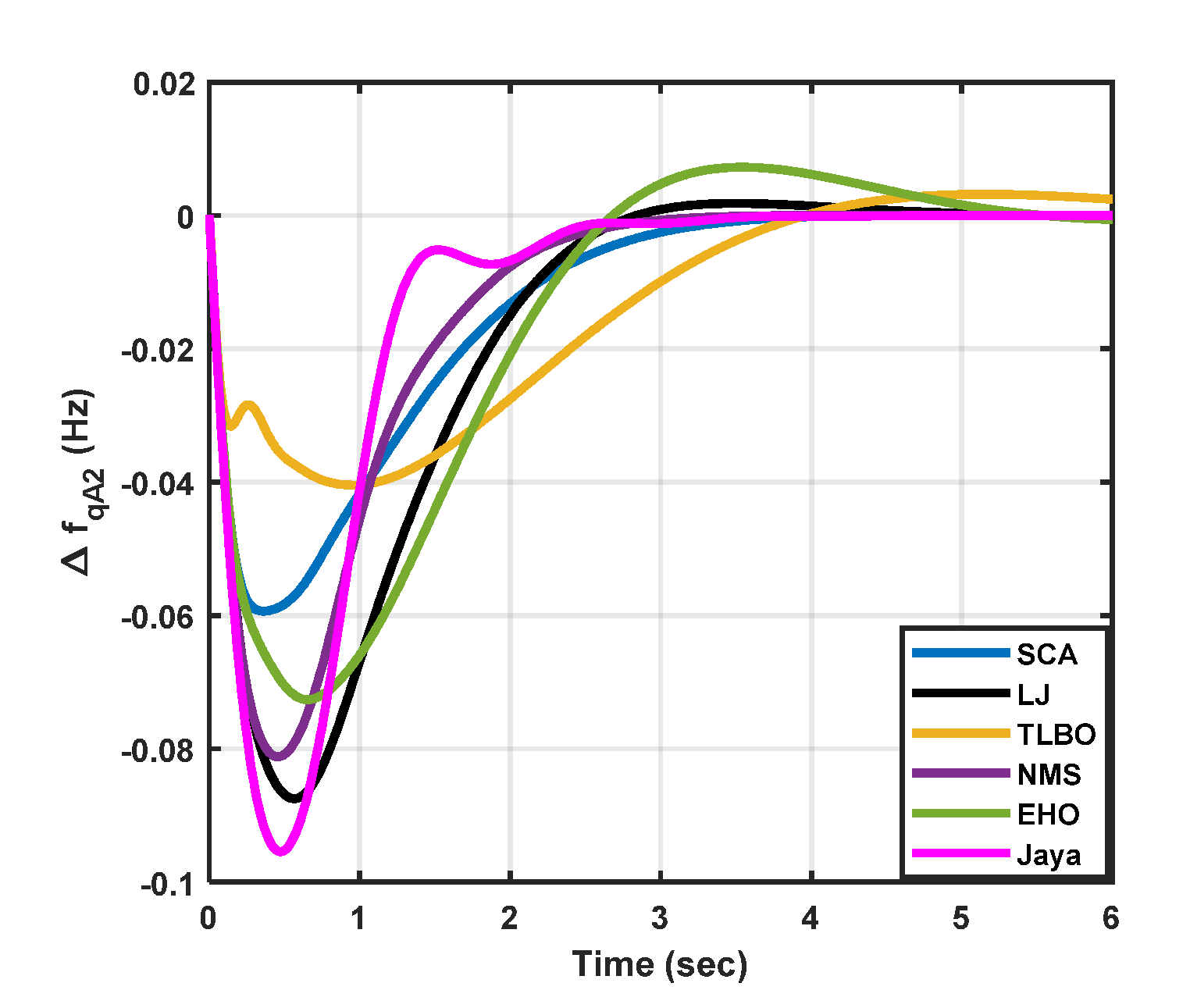

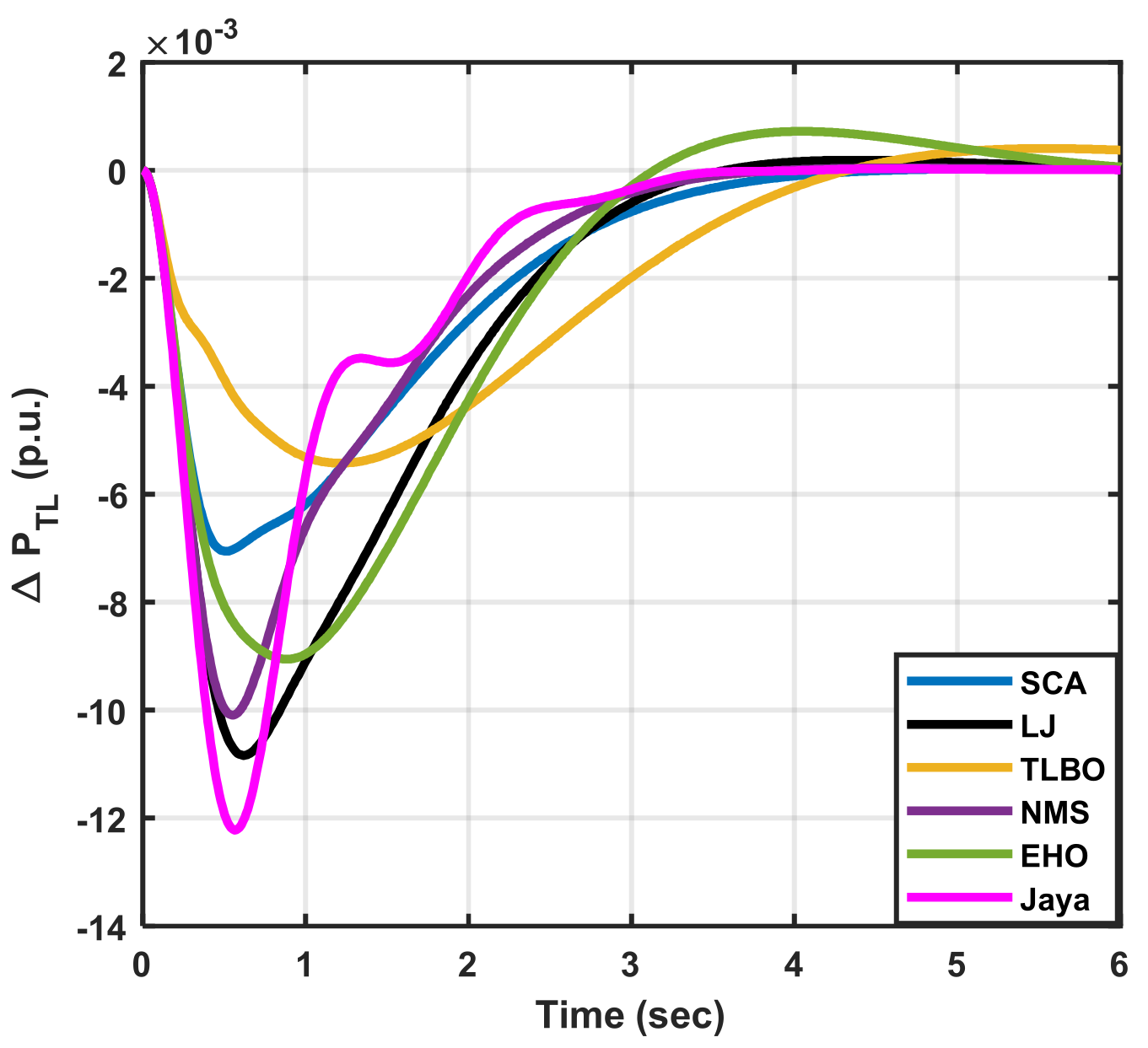

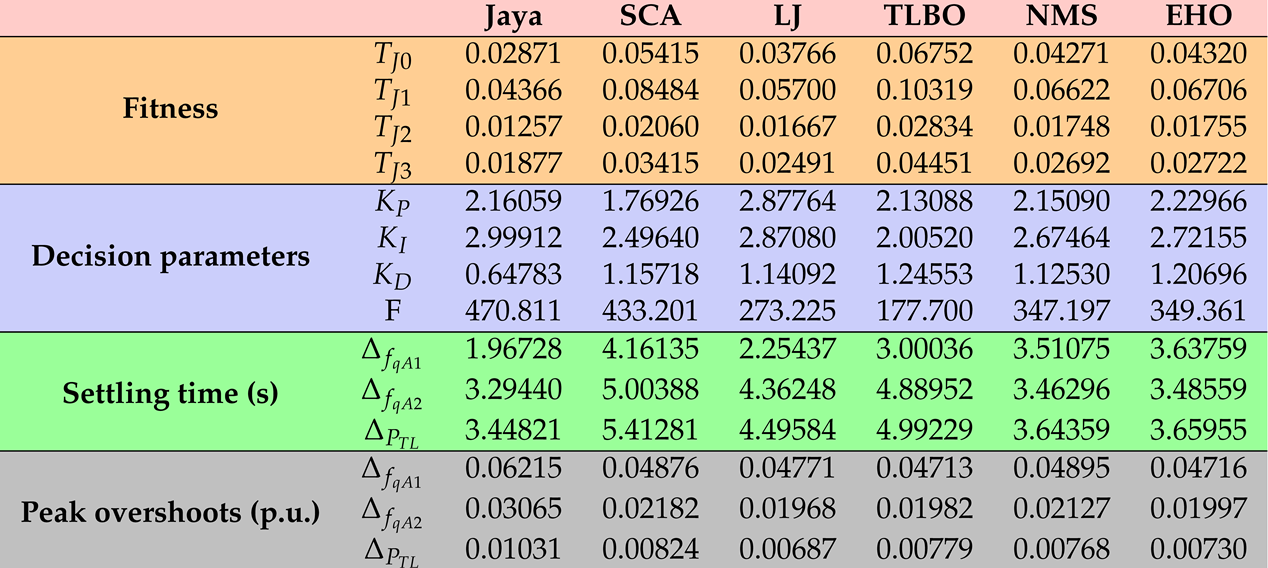

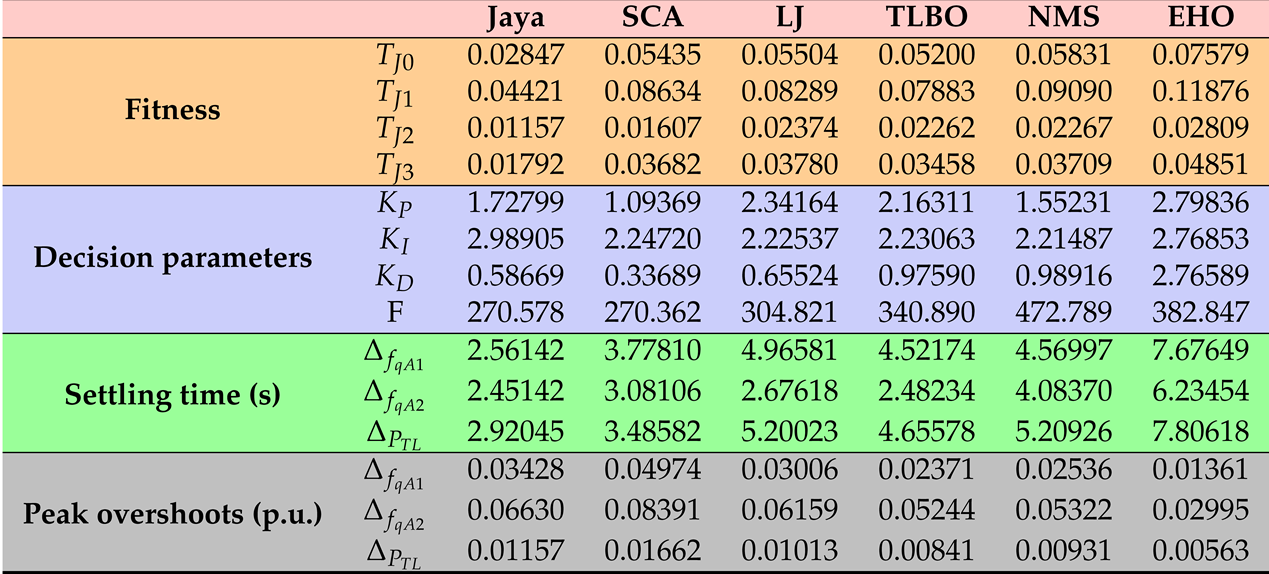

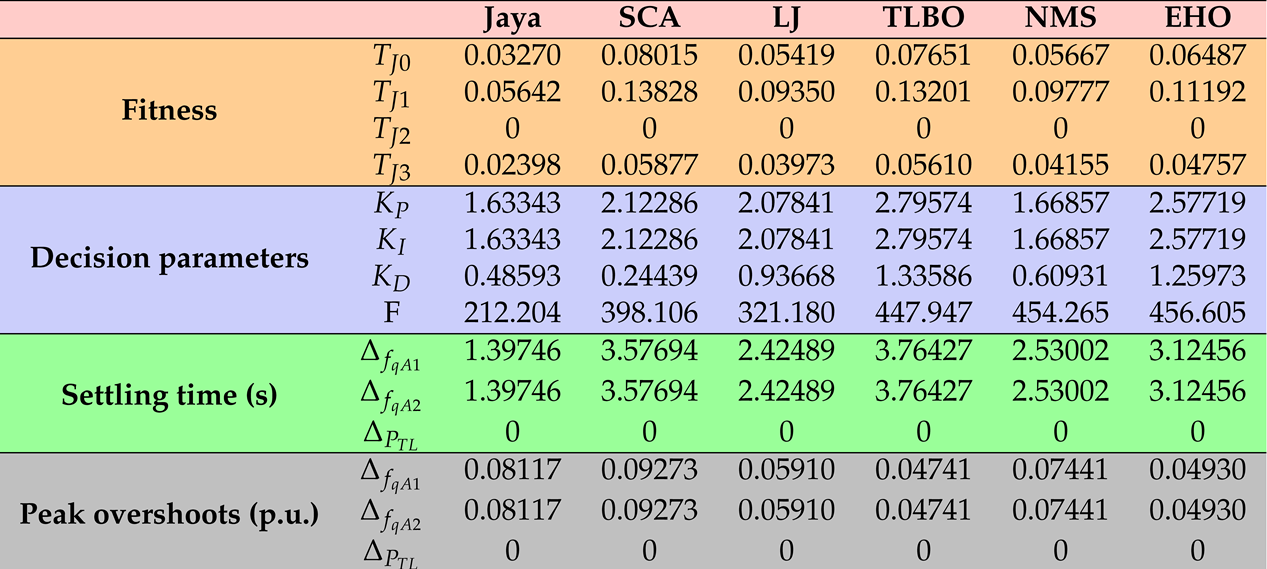

| Step load variations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Case studies | Area 1 | Area 2 |

| I | 0.07 | 0 |

| II | 0 | 0.07 |

| III | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| IV | 0.07 | -0.07 |

| V | 0.07 | 0.14 |

| VI | 0.14 | 0.07 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

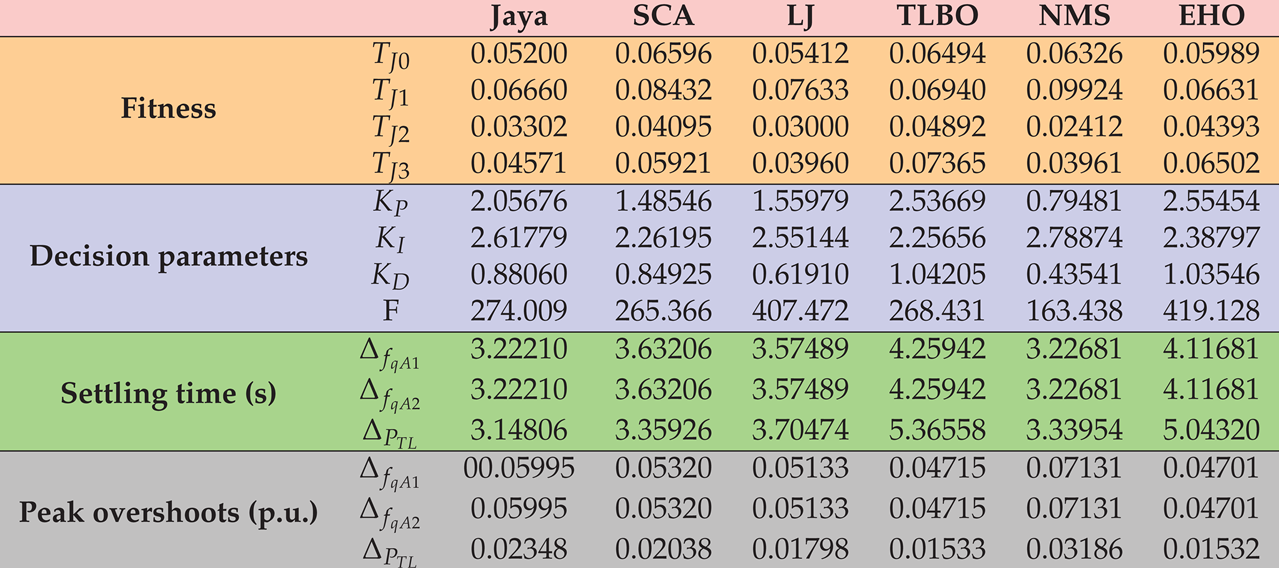

| Cases | Statistical measures | Jaya | SCA | LJ | TLBO | NMS | EHO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Mean | 0.02976 | 0.09934 | 0.06514 | 0.08390 | 0.04687 | 0.05063 |

| Min | 0.02871 | 0.05415 | 0.03766 | 0.06752 | 0.04271 | 0.04320 | |

| Max | 0.03343 | 0.13681 | 0.09762 | 0.12246 | 0.05011 | 0.06231 | |

| Standard deviation | 0.00205 | 0.03024 | 0.02580 | 0.02375 | 0.00296 | 0.00804 | |

| II | Mean | 0.02913 | 0.09286 | 0.10004 | 0.07604 | 0.08159 | 0.07970 |

| Min | 0.02847 | 0.05435 | 0.05504 | 0.05200 | 0.05831 | 0.07579 | |

| Max | 0.02974 | 0.16590 | 0.19179 | 0.10603 | 0.10371 | 0.08434 | |

| Standard deviation | 0.00047 | 0.04909 | 0.05450 | 0.02037 | 0.01794 | 0.00359 | |

| III | Mean | 0.04533 | 0.23470 | 0.10134 | 0.11566 | 0.11939 | 0.11585 |

| Min | 0.03270 | 0.08015 | 0.05419 | 0.07651 | 0.05667 | 0.06487 | |

| Max | 0.06973 | 0.42988 | 0.14667 | 0.15864 | 0.14458 | 0.13495 | |

| Standard deviation | 0.01500 | 0.12540 | 0.03525 | 0.03032 | 0.03572 | 0.02878 | |

| IV | Mean | 0.06296 | 0.06780 | 0.08167 | 0.08457 | 0.07379 | 0.06663 |

| Min | 0.05200 | 0.06596 | 0.05412 | 0.06494 | 0.06326 | 0.05989 | |

| Max | 0.06848 | 0.07229 | 0.10889 | 0.11664 | 0.09765 | 0.07052 | |

| Standard deviation | 0.00268 | 0.00630 | 0.02395 | 0.02210 | 0.01455 | 0.00404 | |

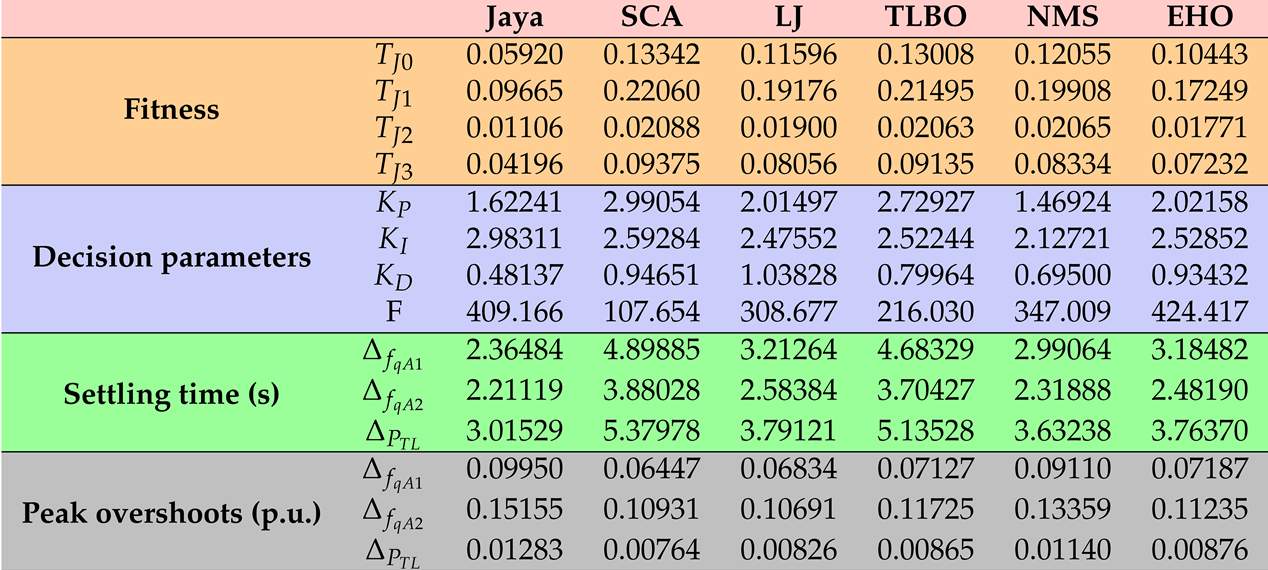

| V | Mean | 0.06900 | 0.29577 | 0.21858 | 0.20074 | 0.13704 | 0.13045 |

| Min | 0.05920 | 0.13342 | 0.11596 | 0.13008 | 0.12055 | 0.10443 | |

| Max | 0.08900 | 0.59853 | 0.36557 | 0.35189 | 0.15336 | 0.16432 | |

| Standard deviation | 0.01222 | 0.19395 | 0.10443 | 0.08977 | 0.01526 | 0.02889 | |

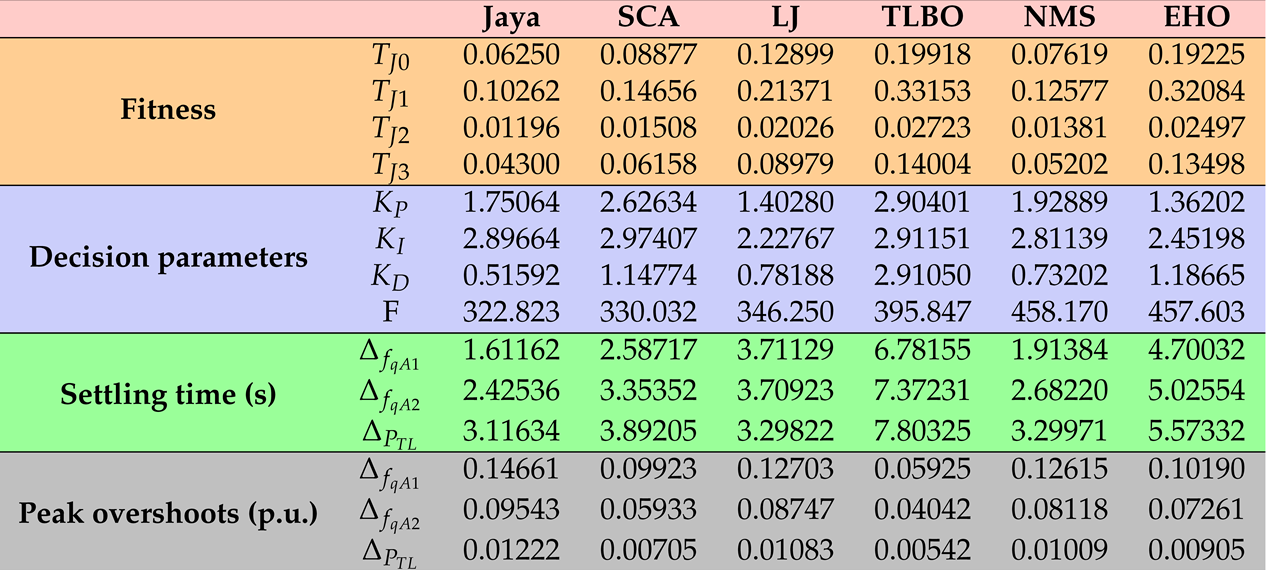

| VI | Mean | 0.07210 | 0.16302 | 0.33597 | 0.21898 | 0.16838 | 0.24129 |

| Min | 0.06250 | 0.08877 | 0.12899 | 0.19918 | 0.07619 | 0.19225 | |

| Max | 0.08819 | 0.30000 | 0.66838 | 0.25634 | 0.21956 | 0.28512 | |

| Standard deviation | 0.01110 | 0.08392 | 0.22385 | 0.02429 | 0.06345 | 0.04132 |

| Friedman rank test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jaya | SCA | LJ | TLBO | NMS | EHO | |

| Mean rank | 1 | 4.6666 | 4.6666 | 4 | 3.5 | 3.1666 |

| Q value | Q=16 | |||||

| p value | p=0.006844 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).