1. Introduction

Nurses play a pivotal role in the healthcare sector. A sustainable working life is a prerequisite for all nursing professionals, to maintain health and to prevent them leaving the profession and the workplace. According to Eurofound [

1]. Sustainable work means that working and living conditions are such that they support people in engaging and remaining in work throughout an extended working life. From a salutogenic perspective, workplace health can be defined as “the ability of the workforce to participate and be productive in a sustainable and meaningful way” [

2]. A salutogenic organisation provides personal, social, and environmental resources that offer coherent working experiences and sustainable organisational outcomes. It promotes the development of the capacities of employees and employers to use these resources ([

2], p. 77). In a nursing context the concept of sustainability is defined based on attributes such as ecology, the environment, the future, globalism, holism, and maintenance [

3]. Extensive research shows that nurses experience their work situation as demanding, characterized by high level of work-related risk factors for disease such as high workload, depression, burnout, and pandemics [

4,

5,

6]. At the same time the shortage of nurses in Europe is so serious that it has been described as “a ticking time bomb” [

7], especially in the case of specialised nurses [

8], which furthermore is aggravated by the trend of nurses’ motivation to leave the profession and workplace [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. It is therefore essential to not only avoid burnout [

13,

16], depression [

17] and mental health problems among nurses [

18], but to identify resistance resources against stress [

19,

20], enhancing resources for health [

21], work-related “push and pull factors” [

11], and even factors that make nurses thrive professionally [

22,

23], that would enable nurses to remain in the profession and workplace.

This makes us focus on the resource-oriented perspective – instead of a risk-oriented - on the work environment and health, the salutogenic perspective [

19,

20]. Previous research shows that the salutogenic core concept Sense of Coherence (SOC) seems to have a moderating as well as a mediating role in buffering stress among nurses [

24,

25,

26]. More than 30 years have passed since Antonovsky [

19] developed the first questionnaire for measuring the sense of coherence (SOC), entitled The Orientation to Life Questionnaire. Over the years, various modified forms of the SOC questionnaire have been developed, with the same questions as Antonovsky but with different response alternatives and different numbers of items included in the studies. As far as we know there are no other instruments, based on the salutogenic theory, and specifically developed for hospital nurses. In an ever-changing world, where a shortage of nurses together with an increasing intention to leave the profession and the workplace, it becomes particularly challenging for all societies, health care systems and nursing practice. Keeping these facts in mind, it is therefore important to identify GRRs and SRRs relevant to today’s society and, particularly to the nursing context. Therefore, to fill this knowledge gap, the Salutogenic Survey on Sustainable Working Life for nurses (SalWork-N) was developed and is presented here. The aim of the study was to develop, explore and psychometrically test The Salutogenic Survey on Sustainable Working life for Nurses, a new profession specific questionnaire identifying resistance resources that may enhance nurses to manage stress at work.

The Salutogenic Framework

In 1987 Antonovsky [

19] introduced the Orientation to Life Questionnaire, the Sense of Coherence Scale, describing three central dimensions to manage stress, comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness. In the first two decades the focus has been on validating the SOC questionnaire in different countries, cultures, and contexts, and on different populations [

20]. During this time salutogenesis was regarded as merely the same as the SOC. However, this view has more recently been broadened. Salutogenesis is now seen as a theory, a health model, and an orientation to life [

20], not only the measurement of SOC. Salutogenesis is an umbrella concept covering many theories of salutogenic and health promoting factors applicable not only at an individual level, but at a group and an organizational level [

20]. Along with the core concept of SOC, there are two other central concepts to keep in mind, the Generalized (GRRs) and Specific (SRRs) Resistance Resources against stress [

19,

20]. The function of these resistance resources is that they create conditions for people and groups (here nursing teams) to develop strong SOC. Extensive research on the SOC gives evidence for that a strong SOC mediates as well as moderates stress [

20]. In the 21st century more attention was paid to the relationship between SOC and nurses' work-related patterns of behaviour [

34]. Burnout was related to low SOC, meaning that the ability to manage stress was impaired. Work related patterns of behaviour among Polish nurses showed that a strong SOC was associated with healthy functioning [

27]. More recent research focused on how SOC affects nurses’ quality of life and job satisfaction. Ando and Kawano [

28] examined the relationships among moral distress, SOC, mental health, and job satisfaction among 130 Japanese psychiatric nurses. They found that moral distress was negatively related to SOC and job satisfaction. In Singapore, a study among hospital nurses showed that social support and SOC predicted high quality of life in all domains [

29].

The GRRs refer to “phenomena that provide one with sets of life experiences characterized by consistency, participation in shaping outcomes and an underload-overload balance” ([

19], p. 19). According to Antonovsky [

19,

30] such resources may include the following factors (1) material resources (e.g., money), (2) knowledge and intelligence (e.g., knowing the real world and acquiring skills), (3) ego identity (e.g., integrated but flexible self), (4) coping strategies; (5) social support, (6) commitment and cohesion with one’s cultural roots, (7) cultural stability, (8) ritualistic activities, (9) religion and philosophy (e.g., stable set of answers to life’s perplexities), (10) preventive health orientation, (11) genetic and constitutional GRRS, and (12) individuals’ state of mind [see 31 for review]. The GRRs are factors that make it easier for people to perceive their lives as consistent, structured, and understandable and thus prevent tension from being transformed into stress. A GRR is a generality, and a SRR is a particularity or context bounded [

21].

Research on salutogenesis has largely concentrated on the use of the two original questionnaires for measuring SOC, the 29-item Orientation to Life Questionnaire and the 13-item questionnaire. The research is extensive and convincing, a strong SOC is related to positive individual health development but also to health promotion at group level, organizational level in healthcare settings and among nurses. For further exploration of research on the function of SOC and the core concepts GRRs and SRRs, see The Handbook of Salutogenesis [

20].

There are modified instruments, based on the salutogenic theory of health, adjusted for workplaces (WorkSoc) [

32], for measuring work-related salutogenic factors, the Salutogenic Health Indicator Scale (SHIS) [

33] and the Work Experience Measurement Scale (WEMS) [

34]. More than 15 years have passed since Bringsén et al. [

33] collected data among hospital staff (doctors, nurses, assistant nurses, rehabilitation staff, administrators, service personnel) and introduced the Salutogenic Health Indicator Scale (SHIS). At the same time hospital employers (pre/post-op for ambulatory surgery and internal medicine wards) participated in focus-group interviews about their work experiences [

34], which ended up in a new questionnaire, the Work Experience Measurement Scale (WEMS), particularly aiming at identifying work-related specific enhancing resources (SER). This was an attempt to enlarge the discussion about specific resistance resources [

19] to enhancing factors and health promotion. Common to these alternative instruments is that they measure salutogenic factors with their own questions and different response options to Antonovsky’s SOC scales. As far as we know there are no other instrument developed, based on the salutogenic theory, and specifically focused on resistance resources and directed to the context of hospital nurses.

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design

The study design is explorative. It is based on the salutogenic theory and its principles [

19], i.e., it focuses on nurses’ resources and capacities to manage daily stressors in an increasingly demanding work environment. The item generation process was inspired by the MEASURE approach to instrument development by Kalkbrenner [

35], Boateng et al. [

36] and DeVellis [

37], following steps: 1) Make the purpose and rationale clear, which means to define the purpose of conducting an instrument development study by telling what they are seeking to measure and why a development of a new instrument is necessary including a literature review of the construct and a summary of their review. Further, cite instruments that already exist, and highlight a gap in the existing measurement literature [

37]; Establish empirical framework, which means identifying a theory from the literature review to set an empirical framework for the item development process. In the next, Articulate a theoretical blueprint, to decide which areas and concepts are to be investigated, followed by Syntehsize the content and scale development already done. Next step is to Use experts in the field for discussions of relevant research in the field. Thereafter it is time to Recruit participants and administer the posting of the instrument. The final step is to evaluate validity and reliability by pilot testing.

2.2. Participants

Participants were registered nurses (assistant, general and specialist nurses) in a hospital group in western Sweden. The hospital group offers specialized care in many areas, such as emergency medicine, specialist medicine, surgical care, and adult psychiatric inpatient care. The inclusion criteria were understanding and speaking Swedish as well as working in close patient care within the hospital group.

2.3. Data Collection

Data collection took place during January and February 2020, just before the first case of COVID-19 was found in the country. The convenience sample method was used for recruiting all available nurses in the hospital group. An electronic version of the questionnaire was administered online using the web-based Evaluation and Survey System (EvaSys), time- limited to the data collection period and only accessible to the invited participants.

2.4. Data Analysis

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was carried out to identify the underlying structure of the questionnaire [

38,

39]. By grouping the items together in the questionnaire, the results are merged into few components, which is the purpose of PCA [

40]. To ensure the appropriateness of using PCA on the data set, The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure (KMO) should be > 0.5 and a significance level of .001 for Bartlett’s Test of sphericity should be obtained. To explain as much of the total variance as possible, the varimax with Kaiser normalization method for rotation was used for extraction of the components and an eigenvalue >1 was set as a criterion [

41]. Loadings >0.60 were accepted to construct logical components and ensure the theoretical meaning. The collected data was tested for multicollinearity, correlation values >0.9 were removed. Based on an anti-image correlation matrix some variables in the diagonal <0.5 were removed. If the variables would be included in the model, we asked for a residual value < 0.05. A reproduced correlation test showed that 25 % of the variables included met the requirement. Removed were also components where only one variable was loading.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Sample

The study was carried out in a healthcare hospital group in western Sweden. A total of 782 nurses who met the inclusion criteria were invited to participate, of whom 475 completed the SalWork-N questionnaire. The response rate was 60.7 %. Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants are presented (

Table 1).

3.2. The Instrument Development Process

This study is part of a larger study, where data focused on factors that enhance nurses to manage work-related stress, were collected. The instrument development process is not previously described and/or published. The process follows recommendations from Streiner and Kottner [

42].

3.3. The MEASURE Approach

The instrument development process was inspired by the MEASURE approach to instrument development by Kalkbrenner [

35], Boateng et al. [

36] and DeVellis [

37].

Make the purpose and rationale clear, is the first step. The purpose was to identify generalized and specific resistance resources among hospital nurses in close patient care, to learn about their ability to manage workload and the resources are available. Existing research on a resource-oriented approach and instruments already developed were reviewed [

20]. Two instruments were identified, none of them not particularly directed to hospital nurses in close patient care and not specifically aimed at exploring GRRs and SRRs. In addition, interviews with nurses in close patient care with questions derived from the salutogenic theory and its core concept sense of coherence (SOC) was carried out analyzed through a qualitative content analysis of the data by an inductive (data-driven) approach and a deductive approach for theoretically discussing the findings. Based on the theoretical idea and empirical data of salutogenesis, all items were created de novo. Seven areas (subthemes) emerged from the above-mentioned qualitative study as most relevant to the purpose of this study: job satisfaction, professional attitudes, workload, work motivation, commitment, belonging in working life, factors and conditions for remaining in the profession. To sup up, there is a knowledge gap in the existing measurement literature on generalized and specific resistance resources among hospital nurses.

The next step in the process was to

Establish empirical framework – the established framework was the salutogenic theory by Antonovsky [

19], a well-established theory of how people can manage stress and still maintain health. The theory is nowadays implemented not only at an individual level (here nurses) but on groups (nursing team) and organizations (health care sector) [

20].

The Articulated theoretical blueprint was to focus on the Generalized and Specific Resistance Resources against stress based on the salutogenic theory. A pool of 107 items with response alternatives based on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (Not true at all) to 5 (Is very accurate), with the additional option of no point of view at all. Examples of questions are as follows: Job satisfaction – “I experience job satisfaction in my current work situation. “I feel that I can manage the workload at my job right now”. Response alternatives: 1/Very low (Not true at all) to 5/Very high (Is very accurate). Contacts with patients – Patient contacts motivate me when I start a work shift”. “Patient contacts motivate me to remain a nurse”. 1/To a very low degree (Not true at all) to 5/To a very high degree (Is very accurate). The scale is a sum scale, high scores correspond to high level of conformity.

Next in the process was to

Synthesise the content and scale development already done. We found the Salutogenic Health Indicator Scale (SHIS) [

33] and the Work Experience Measurement Scale (WEMS) [

34].

Experts in the field of Salutogenesis were Used for discussions of relevant research. All researchers in the group were familiar with the salutogenic theory, how to construct surveys as well as the design and methods used for the analysis. To reach consensus on which question areas were relevant for the new questionnaire, several workshops, and discussions within the research group were done. Discussions with experts in the field, among others, the inner core of researchers on salutogenesis, some of them former colleagues to Aaron Antonovsky, and a global network of salutogenesis, were carried out.

Recruited participants were hospital nurses in close patient care, who were invited to participate in the study.

Evaluate validity and reliability by pilot testing is the final step in this process. A pilot test was conducted on nursses, who were studying to become specialist nurses by giving them 30 minutes to answer the questionnaire. The students were informed about the aim of the study, and its potential usefulness for nursing practice by one of the authors (HN). Informed consent was obtained before they started answering the questionnaire and their anonymity was ensured. After the participants filled in the survey, one of the researchers (HN) carried out a follow-up by asking questions if any item was particularly unclear, if any question was difficult to respond on or if the answer options were unclear. After all pilot tests, the answers received were discussed with the rest of the research group. Nine questionnaires were returned. A close examination of the answers indicated the need only for minor linguistic adjustments. For example, in the questions about forms of employment, some questions concerning commitment and belonging to the workplace were adjusted. In addition to background factors such as age, gender, professional education, length of experience as a nurse and type of employment, the final SalWork-N questionnaire consisted of ten areas of interest. Subsequently, several changes and clarifications were made both questions that had been unclear or difficult to respond on, but also some clarifications of the answer options to improve the survey. The pilot test was conducted in three separate groups on three different occasions, 15–23 nurses participated in each group. After this review, all questionnaires were destroyed because they would not be used for further purposes. All nurses who participated in these pilot tests were informed before they filled in the questionnaire about how their answers and viewpoints would be taken care of and what would be done with the response forms.

3.4. Principal Component Analysis

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) amount was acceptable at 0.868 [

41] and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity was equal to 11285.135 (p< 0.0001), which indicated the suitability of PCA on the data set. Salutogenic components related to nurses’ work environment were measured using principal component analysis of the SalWork-N. After varimax rotation, a four-component model containing 19 items with eigenvalues greater than one were extracted as the most relevant for explaining workplace resources, which accounted for 64.7% of the total variance. The share of each component after varimax factor rotation (

Table 2) is shown below.

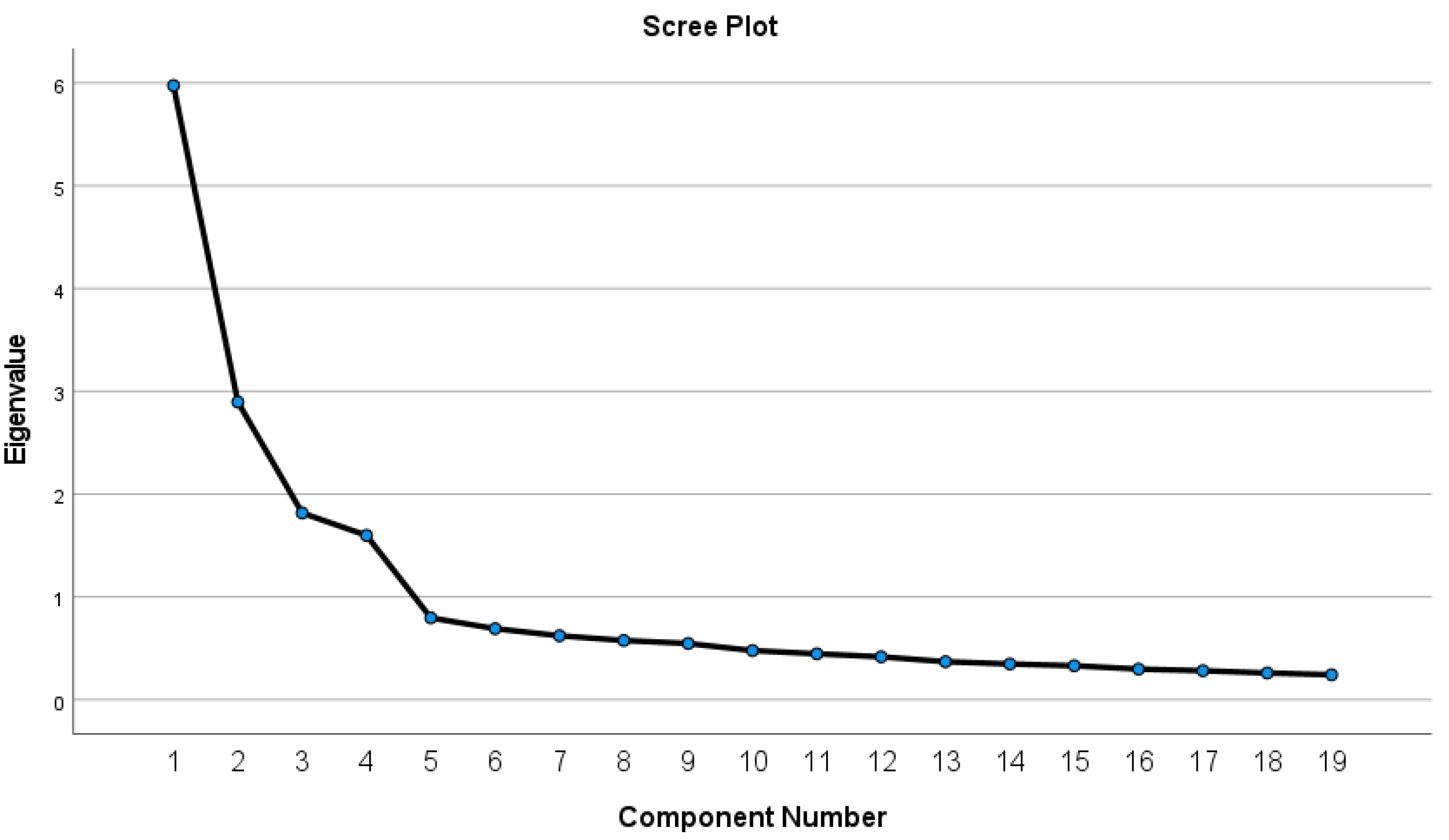

The first component, labelled as Manageability as a resource for handling workload, accounted for 21 % of the explained variance, followed by contacts with patients as resources for nurses’ job satisfaction (17.8 %). The professional attitudes as a nurse are labelled as resources for nursing (15 %) as well as the importance of colleagues as resources for remaining in the profession (11 %). The scree plot of the 19-item SalWork-N scale (

Figure 1) is presented below.

3.5. Reliability

3.5.1. Internal Reliability

In addition, after the final component extraction of the SalWork-N questionnaire, the internal reliability of the new scale was defined using Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale. The Cronbach’s alpha of the 19-item SalWork-N demonstrated acceptable internal reliability with a value of 0.87. The IBM SPSS v27.0 8. was used for statistical analysis.

3.5.2. Inter-Item Correlations

An examination of the inter-item correlations (

Table 3) is shown below.

The following item pairs: 5 and 7, 9 and 10 (r = 0.64) and 13 and 14 (r = 0.63) achieved the highest values.

3.5.3. External Validity

External validity, that is a validation of the new scale with existing salutogenic measures, was not tested because other standardized and validated instruments to measure salutogenic generalized and specific resistance resources for nurses’ work environments were not found and consequently have not been used simultaneously in this study. This is a task for future research.

4. Discussion

This study was conducted to describe the development of a new profession specific questionnaire for measuring work-related resistance resources against stress among hospital nurses, followed by a psychometric test of the questionnaire. The theoretical framework behind this study is salutogenesis, a resource-oriented theory explaining why some nurses can manage stress, whilst others do not.

4.1. The Process of Developing the Questionnaire

The development of a new questionnaire requires many considerations. Following the recommendations by Streiner and Kottner [

42] for reporting results of studies of instrument development and testing, the starting point was to thoroughly review research on nurses’ work-environment, workload and how they struggle to manage everyday stress. Thereafter, twelve interviews of a clinical nurses in close patient care, were conducted. Further, based on the content of the interviews and the theoretical framework chosen (salutogenesis) items reflecting factors affecting the work situation and workload were identified. These items were tested on a larger sample (n=475) of clinical nurses. According to Streiner and Kottner [42,p. 1973] “the scale is ultimately to be used with a clinical sample … because it is questionable whether the results of procedures such as factor analysis are generalizable from one group to the other.” In this study, the sample is the same, right from the very beginning to the final principal component analysis, that is, hospital nurses in close patient care. Streiner and Kottner [42,p. 1973] also provide sample size recommendations to achieve replications. “… and factor analysis, usually require at least ten participants per variable to achieve replicable findings.” We were aware of their recommendation to not use the same data set for validation which the instrument was developed, due to overly optimistic results. Therefore, we only used the principal component analysis to catch the underlying structure of the new questionnaire and emphasize that validation requires a larger sample preferable at national level, but still on hospital nurses in close patient care. We argue that the development process of the SalWork-N questionnaire well meets the recommendations in terms of process and sample size.

From the literature review of studies on using the salutogenic theory and the core concept sense of coherence, it appeared that most of the research was about using the SOC scale in different context and on different samples. Research dealing with GRRs and SRRs, particularly directed to identify new and more sensitive ones to changes today, was scarce. We know that a strong SOC moderates and mediates stress and predicts depressive state, burnout, and job dissatisfaction among female nurses [

24]. Understanding of the function behind GRRs and SRRs, the critical question is how to strengthen these resources among hospital nurses and hereby reduce their motivation to leave the profession and/or the workplace. Few studies have explored the connection between a strong SOC and intention to leave. Matsuo and colleagues [

43] found that burnout among nursing professionals in Japan directly affected intention to leave, it also affected intention to leave through SOC. SOC did not directly affected intention to leave but lessened the effect of burnout on striving for work-balance, therefore reducing its impact on intention to leave. It is not enough to just measure SOC, one must also identify and measure resources, that enhance a positive development of SOC in a working context of nurses.

Based on the salutogenic theory, the SalWork-N, identifies hospital nurses’ resistance resources against stress. It is one of the questionnaires that go beyond the original scales measuring sense of coherence, health indicators (SHIS) and workplace health resources (WEMS). The aim of developing the Health Indicator Scale was to measure health among healthcare staff (doctors, nurses, assistant nurses, rehabilitation staff, administrators, and service personnel) [

33]. Dimensions in the underlying structure of SHIS were among others perceived stress, illness, energy, physical function, psychosomatic function, and self-realization, thus the central focus was on individual health. The Work Experience Measurement Scale (WEMS) intend to measure Specific Enhancing Resources in work (nurses, assistant nurses, physician, administrative, paramedical personnel, and managers) covering dimensions such as management, reorganization, internal work experience, pressure of time, autonomy, and supportive working conditions ) [

34]. Both instruments contribute substantially to highlighting the salutogenic perspective of health in working life. However, none of them are particularly intended to measure generalized and specific resistance resources and adjusted for hospital nurses. The items in WEMS come closest to the SalWork-N questionnaire, however, the selection of the sample is broad, with professions having varying tasks in health care. Therefore, we argue that the development of a profession specific instrument measuring resistance resources among hospital nurses in close patient care can be justified.

4.2. The Results from the Principal Component Analysis

This study used PCA as the component extracting method to identify the underlying structure of the questionnaire [

38,

40]. PCA is frequently used in studies where the underlying assumption is that the items are independent of each other. Initially, the questionnaire consisted of many questions, making it important to reduce them to the smallest possible number but with the greatest possible theoretical explanation. The varimax with Kaiser normalization method for rotation was used for extraction of the components, a decision made after testing the data set several times, which resulted in a linear orthogonal transformation. According to Gie and Pearce [

44], there should be few cross loadings (i.e., split loadings) so that each factor defines a distinct cluster of interrelated variables. A cross loading is when an item loads at .32 or higher on two or more factors [

40,

41,

45]. All the loadings in this study were <.30, thus do not load heavily on other components. Another issue is the cut-off point for loadings. Here loadings > 0.60 were accepted to construct logical components and to ensure theoretical meaning. There are general rules and no consensus about the cut-off point of loadings, some use > 0.20, others >0.30, whilst even > 0.50 is used. The most important thing is to set a cut-off point so that the greatest possible theoretical understanding can be achieved. Tabanick and Fidell [

40] describe loadings >0.60 as being very good. All the loadings in this study are > 0.63, which means that the items really belong to the components presented.

4.2.1. Manageability as a Resource for Handling Workload

The results from the principal component analysis revealed a four-component model of 19 items measuring generalized as well as specific resistance resources, which allow nurses to manage the increased workload and high level of stress. The items that emerged from the analysis of the component

“Manageability as a resource for handling workload” reflect both individual and organizational resources at disposal. This was the most important component, accounting for 21 % of the explained variance. The result s is not surprising, as there is extensive research on the consequences for nurses of a stressful work environment in terms of burnout and depression [

4,

5] . Drawing on the salutogenic theory, this comes close to the manageability dimension of the Sense of Coherence. Manageability, is the instrumental or behavioral dimension of SOC, defined as the degree to which one feels that there are resources for one's disposal, which can be used to meet the requirements of the stimuli that they are bombarded by [

19]. Research explaining why nurses stay in the profession explored “push” and “pull” factors of nurses’ intention to leave [

11]. Understaffing, emotional exhaustion, poor patient safety, and performing non-nursing care were “push” factors, “positive perception of quality and safety of care” and “performing core nursing activities” were factors explaining why nurses stayed in the profession. A similar study was conducted among German nurses [

46]. Here “pull” factors were identified in terms of professional pride, professionalisation and improving the image of nursing as a profession.

4.2.2. Contacts with Patients as Resources for Job Satisfaction

“Contacts with patients as resources for nurses’ job satisfaction” was the second most important component (explained 17.8 % of the variance). Patient contacts seemed to give nurses meaning in work. The items in this component reflect the important relationship between nurses and patients, i.e., the innermost essence of nursing. Nurse-patient interaction seems to affect all the three levels of body-mind-spirit and is shown to be a key salutogenic resource in supporting patients’ meaning-making processes [

47]. Nursing gives life meaning and is the essence of job engagement, were findings from a qualitative study among community nurses in Norway [

23]. The results from the analysis of the second component are in line with what is called “Specific Enhancing Resources (SER)”, which are shown to contribute to savouring positive experiences of nursing [

34].

4.2.3. Professional Attitudes as Resources for Nursing

The four items in the component reflect nurses’ attitudes to and experiences of work, labelled as Professional attitudes as a nurse as resources for nursing, accounting for 15 % of the total variance. The work as a nurse was found to have some individual characteristics such as challenging, varying, stimulating, creative and developing. These four items were cached by the PCA analysis. In the questionnaire that was sent out to the nurses, there were more questions about the professional role, i.e., how well the education matches the demands made today, the importance of meaningful tasks, and whether you feel proud in being a nurse. None of these items contributed to any greater extent to the explanation of the total variance.

4.2.4. Colleagues as Resources for Remaining in the Profession

The fourth component was labelled as “colleagues as resources for remaining in the profession” (11 %). Three items were cached by the PCA analysis, showing the importance of having supportive colleagues. One item, “Colleagues make me feel a sense of belonging in working life” is interesting, insofar as the question harmonize with the salutogenic theory of being in a comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful context, here nursing. Social support is one of the most important generalized resistance resources [

19].

The findings from this study capture today’s changes in the work environment for nurses, which in turn give the prerequisites for the leaders in the healthcare sector to create a more sustainable working environment for nurses by measuring Generalized and Specific Resistance Resources. The basis for such balance could be that health care leaders promote a creative and positive working climate by strengthen; the contacts with patients as resources for job satisfaction, the professional attitudes as a resource for nursing and strengthen colleagues as resources to remain in the profession for nursing. These components can enable nurses strengthen their manageability as a resource for workload and the ability to practice the profession safely and satisfactorily with reduced stress. Research on best practice recommendations for healthy work environment for nurses shows that central in creating sustainable working conditions requires leadership, effective communication, teamwork, and professional autonomy [

48]. Drawing on the salutogenic theory Stock [

22] explored salutogenesis as a concept of health and wellbeing in nurses who thrive professionally. Qualitative data analysis revealed themes as “other people”, “passion”, “coping mechanisms”, “personal characteristics” and “time”. Vaandrager and Koelen [

2] argued that making changes that promote health and sustainability in workplaces requires an organisational understanding that reaches beyond individual responsibility, it depends on everyday technical, social, and personal resources (GRRs) as well as employees’ capacities to use these resources (SRRs). Thus, is it about creating a supportive environment and “healthy” organisations, where nurses can thrive, not just survive. The responsibility for such development must not lie with the individual nurse, but also with the whole organisation.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths and limitations. Firstly, the new salutogenic questionnaire presented here, the SalWork-N, is one of the next generation of questionnaires measuring resistance resources related to nurses’ work situation. The questions are profession-specific in that they are aimed at professional nurses in close patient care and emerged from face-to-face interviews with nurses in the same context. Secondly, the scale is applicable to a healthcare setting, particularly for nursing professionals with a focus on workplace health, which may contribute to a sustainable working life. It also addresses important factors that may make nurses decide to remain in the profession. In addition, nurses’ education may benefit from this new knowledge for their future professional life.

The data collection was carried out shortly before the outbreak of the COVID pandemic. This can be seen as a limitation, as extensive research shows how the pandemic has increased the workload on nurses and their intention to leave [

49]. Thus, it becomes even more urgent to continue research on nurses’ resistance and enhancing resources to manage workload.

This is the first psychometric exploration of the SalWork-N instrument, using Principal Component Analysis, frequently used in nursing research, as the extracting technique to identify the underlying structure of the questionnaire, which can be considered a limitation. The four-component model with nineteen items explained 64.7 % of the variance. Even if the level of explained variance can be considered acceptable, there is still more than 35 % unexplained. A limitation is that the instrument development could have been firstly preceded by a quantitative analysis of descriptive statistics, correlations, and regressions. However, this is always a matter of balancing between sticking to what we have done, given the prerequisites at disposal, and what we could have done differently if we were starting over. This is a matter for further research in the project.

One might question why we did not use confirmatory factors analysis (CFA) instead of PCA. The reason for choosing PCA was an underlying assumption of uncorrelated and orthogonal components. There is a recommendation to start with a PCA analysis for newly developed instruments and were there is no corresponding instrument to confirm the results on [

40,

42]. A way to further strengthen the analysis could have been to carry out a confirmatory factor analysis on the data set. However, it is recommended that the same data should not be used for an exploratory factor analysis, because it “capitalizes on chance” [

42,

50]. Therefore, future studies need to confirm these findings in larger samples of hospital nurses in close patent care and other methods such as confirmatory factor analysis. The lack of other similar questionnaires measuring resistance resources among hospital nurses can be considered a weakness. Thus, we cannot provide any further empirical information on the comparison with similar questionnaires. This is a task for future research.

4.4. Future Research Directions and Implications

Further research can contribute by validating the instrument with more specific analysis on a considerably lager sample on nurses and health professionals. Being able to measure nurses' work environment from a salutogenic perspective becomes useful for both the hospital leaders on different levels, as well as for nurses in close patient care with an overall goal to create sustainable work environments. Nurses who enjoy their work are motivated to remain in the workplace as well as the profession, they also have good conditions for providing good patient care regardless of the context in which the care is provided.

5. Conclusions

The SalWork-N questionnaire, is profession specific in its character adjusted for hospital nurses in close patient care and identifying resistance resources against stress. The results from the principal component analysis (PCA) support a 19-item questionnaire with four components. The ability to manage the workload was the most important component for nurses’ work environment followed by working close to the patients. Nurses’ attitudes to work as a nurse and support from colleagues were additional important components for nurses to manage work related stress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization - all authors, methodology - first, second and third authors, software - second and third authors, validation - all authors, formal analysis - first, second and third authors, investigation - all authors, resources - last author, data curation - second author, writing original draft preparation - first author, writing, review and editing - all authors, visualization - first and third author, supervision - fourth and last authors, project administration - last author. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript and have substantially contributed in different stages to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval obtained from The Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr 2019-05185). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Guided by the ethical principles of voluntary enrolment, privacy, and confidentiality. Participants could withdraw at any time without explanation. They were informed that the data would be treated according to the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Data Availability Statement

The data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the nurses who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Eurofound. Available online: URL (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Vaandrager, L.; Koelen, M. Salutogenesis in the Workplace: Building General Resistance Resources and Sense of Coherence. In Salutogenic Organizations and Change: The Concepts Behind Organizational Health Intervention Research. Bauer, G.F., Jenny, G.J. (Eds.); Dordrecht, Springer Science, The Netherlands, 2013, pp. 77-89. [CrossRef]

- Anåker, A.; Elf, M. Sustainability in nursing: a concept analysis. Scand J Car Sci 2014, 28, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diehl, E.; Rieger, S.; Letzel, S.; Schablon, A.; Nienhaus, A.; Escobar Pinzon, L.C.; Pavel, D. The relationship between workload and burnout among nurses: The buffering role of personal, social and organisational resources. PloS ONE 2021, 6, e0245798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Ora, C.; Ball, J.; Reinius, M.; Griffiths, P. Burnout in nursing: a theoretical review. Hum Resour Health 2020, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeds Alenius, A.; Lindqvist, R.; Balla, J.; Sharpa, L.; Lindqvist, O.; Tishelman, C. Between a rock and a hard place: Registered nurses’ accounts of their work situation in cancer care in Swedish acute care hospitals. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2020, 47, 101778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://www.healtheuropa.com. Available online: URL (accessed 11 November 2023).

- Statistics Sweden, SCB. Major shortage of specialist nurses. Statistical news 2022-02-22. Available online: URL https://www.scb.se (accessed 11 November 2023).

- Bahlman-van Ooijen, W.; Malfait, S.; Huisman-de Waal, G.; Hafsteinsdóttir, T.B. Nurses’ motivation to leave the nursing profession: A qualitative meta-aggregation. J Adv Nurs. [CrossRef]

- Burmeister, E.A.; Kalisch, B.J.; Xie, B.; Doumit, M.A.A.; Lee, E.; Ferraresion, A.; Terzioglu, F.; Bragadóttir, H. Determinant of nurse absenteeism and intent to leave: An international study. J Nurs Manag 2019, 27, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasso, L.; Bagnasco, A.; Catania, G.; Zanini, M.; Aleo, G.; Watson, R. Push and pull factors of nurses’ intention to leave. J Nurs Manag 2019, 27, 27,946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, W.Y.; Chien, L.Y.; Hwang, F.M.; Huang, N.; Chiou, S.T. From job stress to intention to leave among hospital nurses: A structural equation modelling approach. J Adv Nurs 2018, 74, 74,677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hämmig, O. Explaining burnout and the intention to leave the profession among health professionals – a cross-sectional study in a hospital setting in Switzerland. BMC Health Serv Res 2018, 18, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone, C.; Bruyneel, L.; Anderson, J.E.; Murrells, T.; Dussault, G.; Henriques de Jesus, É.; Sermeus, W.; Aiken, L.; Rafferty, A.M. Work environment issues and intention-to-leave in Portuguese nurses: A cross-sectional study. Health Policy 2015, 119, 1584–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flinkman, M.; Leino-Kilpi, H.; Salanterä, S. Nurses’ intention to leave the profession: an integrative review. J Adv Nurs 2010, 66, 1422–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L. Burnout, Compassion Fatigue, and Secondary Trauma in Nurses: Recognizing the Occupational Phenomenon and Personal Consequences of Caregiving. Crit Care Nurs Q 2020, 43, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brulin, E.; Lidwall, U.; Seing, I.; Nyberg, A.; Landstad, B.; Sjöström, M.; Bååthe, F.; Nilsen, P. Healthcare in distress: A survey of mental health problems and the role of gender among nurses and physicians in Sweden. J Affect Disord, 1: 15;339. [CrossRef]

- Nagel, C.; Nilsson, K. Nurses’ Work-Related Mental Health in 2017 and 2020—A Comparative Follow-Up Study before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 15569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. Unraveling the mystery of health. How people manage stress and stay well. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 1987.

- Mittelmark, M.B. , Bauer, G.F., Vaandrager, L., Pelikan, J.M., Sagy, S., Eriksson, M., Lindström, B. & Meier Magistretti, C., Eds., The Handbook of Salutogenesis, 2nd ed., Springer Nature, Switzerland AG, 2022.

- Nilsson, P.; Bringsén, Å.; Andersson, I. H.; Ejlertsson, G. Development and quality analysis of the Work Experience Measurement Scale (WEMS). Work 2010, 35, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stock, E. Exploring salutogenesis as a concept of health and wellbeing in nurses who thrive professionally. Br J Nurs 2017, 26, 238–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinje, H.; Mittelmark, M.B. Community Nurses Who Thrive. The Critical Role of Job Engagement in the Face of Adversity. J Nurses Staff Dev 2008, 24, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masanotti, G.M.; Paolucci, S.; Abbafati, E. , Serratore, C.; Caricato, M. Sense of Coherence in Nurses: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betke, K.; Basińska, M.A.; Andruszkiewicz, A. Sense of coherence and strategies for coping with stress among nurses. BMC Nurs 2021, 20, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smrekar, M.; Zaletel, K.L.; Franko, A. Impact of Sense of Coherence on Work Ability: A Cross-sectional Study Among Croatian Nurses. Slov J Publ Health 2022, 61, 163–170. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basińska, M.; Andruszkiewicz, A.; Grabowska, M. Nurses’ sense of coherence and their work related patterns of behaviour. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2011, 24, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando, M.; Kawano, M. Relationships among moral distress, sense of coherence and job satisfaction. Nurs Ethics 2018, 25, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowitlawkul, Y.; Yap, S.F.; Makabe, S.; Chan, S.; Takagai, F.J.; Tam, W. W. S.; Nurumal, M. S. Investigating nurses' quality of life and work-life balance statuses in Singapore. Int Nurs Rev 2018, 66, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. Health, stress and coping. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1979.

- Horsburgh, M. E. B.; Ferguson, A. L. Salutogenesis: Origins of health and sense of coherence. In Handbook of stress, coping, and health: Implications for nursing research, theory, and practice. 2nd ed.; Rice, V.H., Ed.; London, Sage Publications, Inc., 2012, pp. 180–198.

- Vogt, K.; Jenny, G.; Bauer, G.F. Comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness at work: Construct validity of a scale measuring work related sense of coherence. SA J Industr Psychol 2013, 39, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringsén, Å.; Andersson, I.; Ejlertsson, G. Development and quality analysis of the Salutogenic Health Indicator Scale (SHIS). Scand J Public Health 2009, 37, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, P.; Andersson, I.H.; Ejlertsson, G.; Troein, M. Workplace health resources based on sense of coherence theory. Int J Workplace Health Manag 2012, 5, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkbrenner, M.T. A Practical Guide to Instrument Development and Score Validation in the Social Sciences: The MEASURE Approach. PARE 2021, 26, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, G.O.; Neilnds, T.B.; Frongillo, E.A.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.R.; Young, S.L. Best Practices for Developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and Behavioral Research: A Primer. Front Public Health 2018, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, Vol. 26, Sage, Thousand Oaks, 2016.

- Norman, G.R.; Streiner, D.L. Biostatistics: the bare essentials. Hamilton: B.C. Decker; 2000.

- Matsunaga, M. How to Factor-Analyze Your Data Right: Do’s, Don’ts, and How-To’s. Int J Psychol Res 2010, 3, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabanick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics. Boston, Pearson, 2013.

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics. London, Sage Publications Inc., 2012.

- Streiner, D.L.; Kottner, J. Recommendations for reporting the results of studies of instrument and scale development and testing. J Adv Nurs 2014, 70, 1970–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, M.; Suzuki, E.; Takayama, Y.; Shibata, S.; Sato, K. Influence of Striving for Work–Life Balance and Sense of Coherence on Intention to Leave Among Nurses: A 6-Month Prospective Survey. Inquiry 2021, 58, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gie, Y.A.; Pearce, S.A. Beginner’s Guide to Factor Analysis: Focusing on Exploratory Factor Analysis. TQMP 2013, 9, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J.W. Best Practices in Exploratory Factor Analysis: Four Recommendations for Getting the Most from your Analysis. Practical Assessment 2005, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, C.; Wensing, M.; Breckner, A.; Mahler, C.; Krug, K.; Berger, S. Keeping nurses in nursing: a qualitative study of German nurses’ perceptions of push and pull factors to leave or stay in the profession. BMC Nurs. [CrossRef]

- Haugan, G. The relationship between nurse-patient interaction and meaning-in-life in cognitively intact nursing home patients. J Adv Nurs 2014, 70, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabona, J.F.; Van Rooyen, D.R.M.; Ten Ham-Baloyi, W. ‘Best practice recommendations for healthy work environments for nurses: An integrative literature review’, Health SA Gesondheid 2022, 27, a1788. [CrossRef]

- Poon, Y.R.; Lin, Y.P.; Griffiths, P.; Yong, K.K.; Seah, B.; Liaw, S.Y. A global overview of healthcare workers' turnover intention amid COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review with future directions. Hum Resour Health 2022, 20, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Widaman, K.F.; Zhang, S.; Hong, S. Sample size in factor analysis. Psychol Methods 1999, 4, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).