Submitted:

15 November 2023

Posted:

16 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

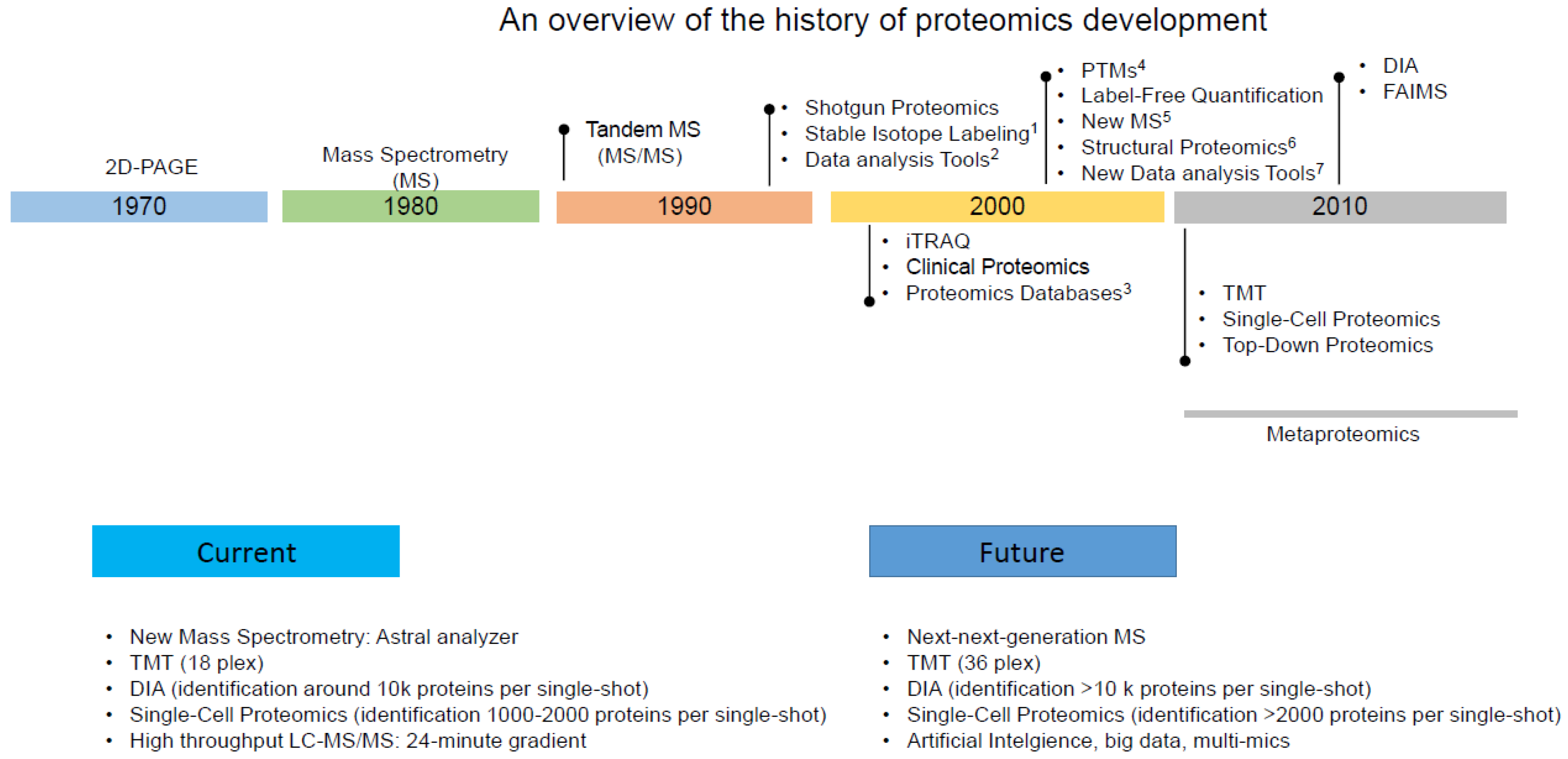

1. Introduction

2. Proteomics Approaches in T. gondii Research

2.1. Early Studies (late 1990s to early 2000s)

2.2. Mid-2000s to the Present

2.2.1. Comparative Proteomics

2.2.2. Subcellular Proteomics

2.2.3. Time-resolved Proteomics

2.2.4. Post-translational Modifications (PTMs)

2.3. Recent Advancements in Proteomics Techniques

2.3.1. Single-cell Proteomics

2.3.2. Data-independent Acquisition (DIA) and High-throughput Proteomics

2.3.3. Targeted Proteomics

2.3.4. Plasma Proteome

2.3.5. Top-down Proteomics

2.3.6. Multi-omics Integration

3. Interactome Analysis

3.1. Affinity Purification

3.2. Proximity Labeling Techniques

3.3. BirA*-mediated Proximity-dependent Biotin Identification (BioID)

3.4. Ascorbate Peroxidase-mediated Proximity Labeling (APEX)

3.5. Two-hybrid (Y2H)

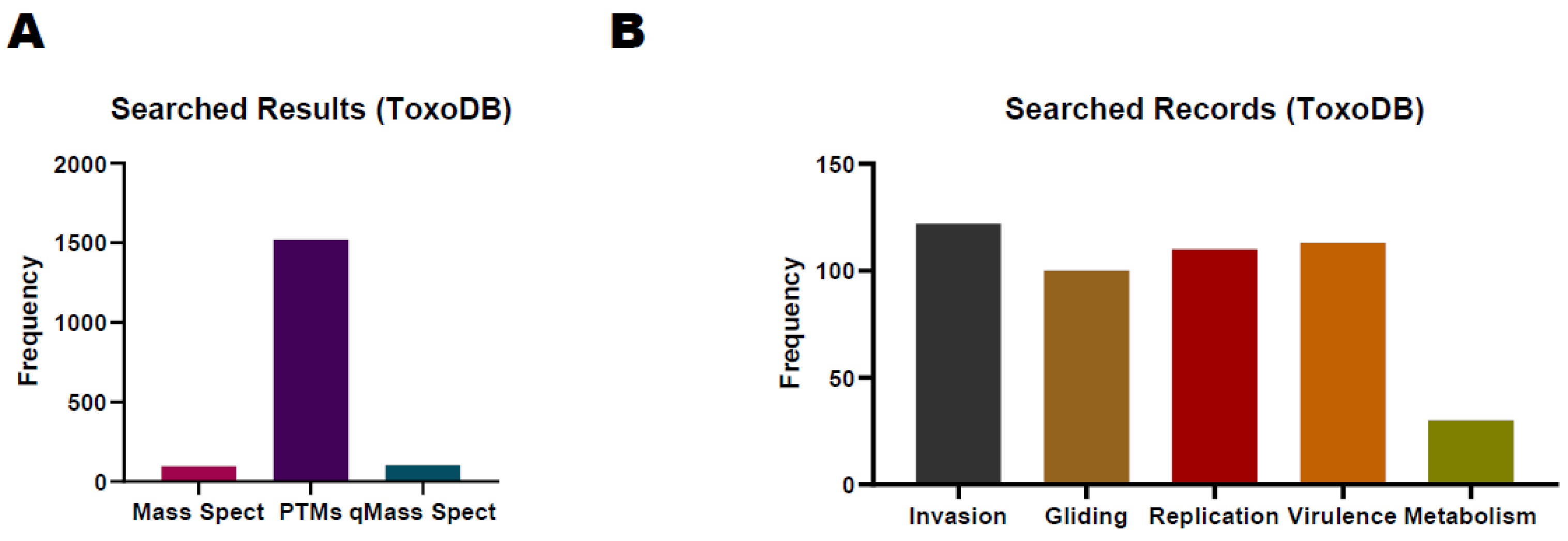

4. ToxoDB in T. gondii Proteome

4.1. Stage-specific Proteomes

4.2. PTM Proteomes

4.2.1. Phosphoproteome

4.2.2. Acetylome

4.2.3. Ubiquitin Proteome

4.3. PTM Crosstalk and Proteome

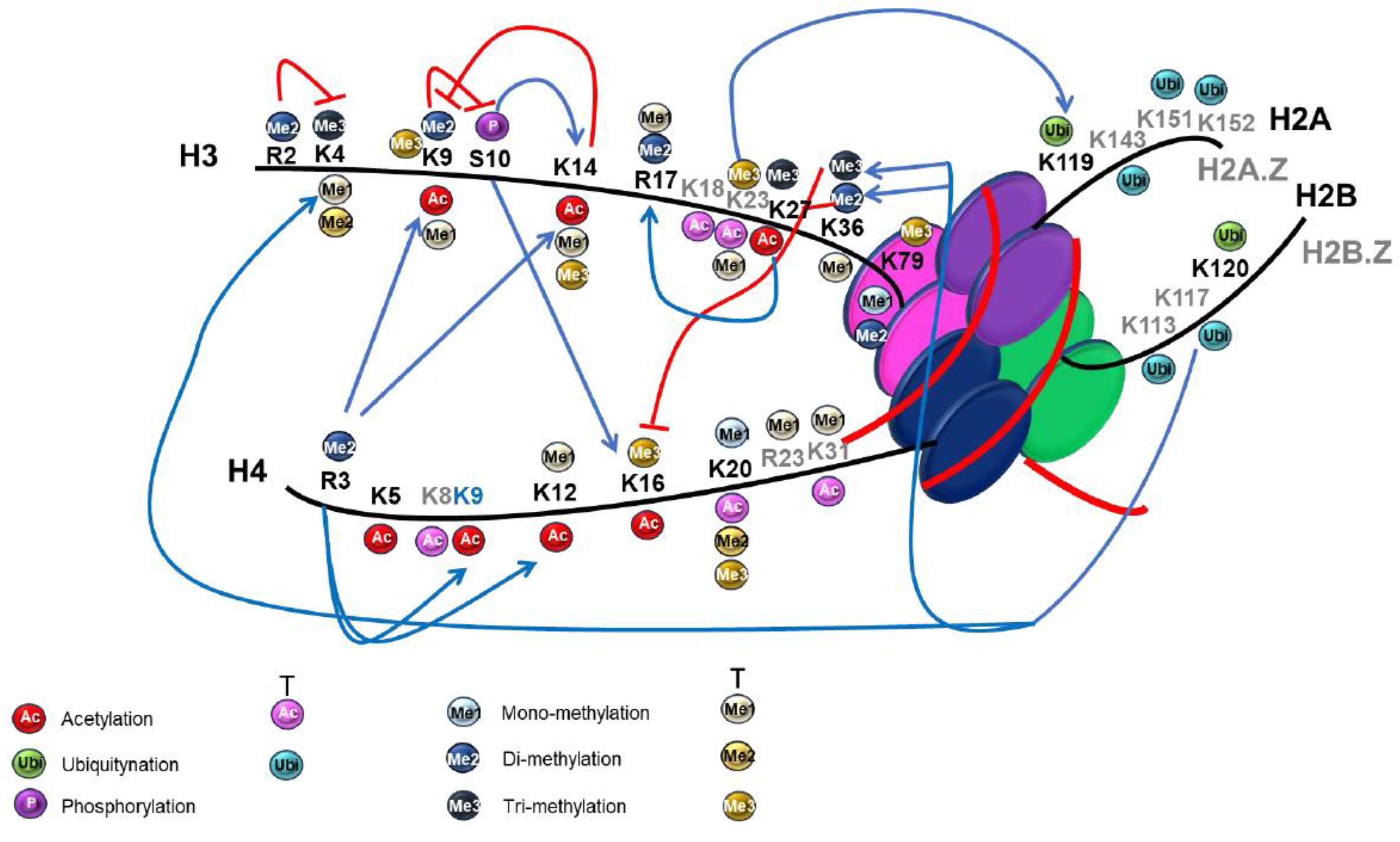

4.3.1. Histones

4.3.2. Hsp90 PTM Crosstalk

5. Subcellular Localization Associated Proteome

6. Proteomics Approach in Drug Discovery Efforts

6.1. Drug Target Identification and Therapeutics

6.2. Insights into Protein Modification and Pathway

6.3. Advancements in Diagnostics and Vaccines

6.4. Screening and Testing Drug Candidates

6.5. Characterizing Drug Resistance

7. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones JL, K.-M.D., Wilson M, McQuillan G, Navin T, McAuley JB, Toxoplasma gondii infection in the United States: seroprevalence and risk factors.Am J Epidemiol. Am J Epidemiol, 2001(154): p. 357-365. [CrossRef]

- Frénal, K.; Dubremetz, J.-F.; Lebrun, M.; Soldati-Favre, D. Gliding motility powers invasion and egress in Apicomplexa. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Kong, L.; Zhou, L.-J.; Wu, S.-Z.; Yao, L.-J.; He, C.; He, C.Y.; Peng, H.-J. Genome-Wide Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation-Based Proteomic Analysis of Toxoplasma gondii ROP18’s Human Interactome Shows Its Key Role in Regulation of Cell Immunity and Apoptosis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Hou, Y.; Hao, T.; Rho, H.-S.; Wan, J.; Luan, Y.; Gao, X.; Yao, J.; Pan, A.; Xie, Z.; et al. A Human Proteome Array Approach to Identifying Key Host Proteins Targeted by Toxoplasma Kinase ROP18. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2017, 16, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego-Lopez, G.M., et al., Metabolic changes to host cells with Toxoplasma gondii infection. bioRxiv, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Katsarou, E.I., et al., Applied Proteomics in ‘One Health’. Proteomes, 2021. 9(3). [CrossRef]

- Bautista, J.M.; Marín-García, P.; Diez, A.; Azcárate, I.G.; Puyet, A. Malaria proteomics: Insights into the parasite–host interactions in the pathogenic space. J. Proteom. 2014, 97, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muselius, B.; Durand, S.-L.; Geddes-McAlister, J. Proteomics of Cryptococcus neoformans: From the Lab to the Clinic. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, J.A., et al., Subcellular proteomics. Nat Rev Methods Primers, 2021. 1. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, F.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, M.; Mi, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Z.; Xu, X.; Hu, X. Label-free proteomic analysis of placental proteins during Toxoplasma gondii infection. J. Proteom. 2017, 150, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Sun, X.; Ren, L.; Yang, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, X. Proteomic profiling of human decidual immune proteins during Toxoplasma gondii infection. J. Proteom. 2018, 186, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, L.M., et al., Toxoplasma gondii proteomics. Expert Rev Proteomics, 2009. 6(3): p. 303-13. [CrossRef]

- Yakubu, R.R., E. Nieves, and L.M. Weiss, The Methods Employed in Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Posttranslational Modifications (PTMs) and Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs). Adv Exp Med Biol, 2019. 1140: p. 169-198. [CrossRef]

- Morlon-Guyot, J.; El Hajj, H.; Martin, K.; Fois, A.; Carrillo, A.; Berry, L.; Burchmore, R.; Meissner, M.; Lebrun, M.; Daher, W. A proteomic analysis unravels novel CORVET and HOPS proteins involved in Toxoplasma gondii secretory organelles biogenesis. Cell. Microbiol. 2018, 20, e12870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurtrey, C., et al., Toxoplasma gondii peptide ligands open the gate of the HLA class I binding groove. Elife, 2016. 5. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.X., et al., Proteomic Differences between Developmental Stages of Toxoplasma gondii Revealed by iTRAQ-Based Quantitative Proteomics. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2017. 8. [CrossRef]

- Xie H, S.H., Dong H, Dai L, Xu H, Zhang L, Wang Q, Zhang J, Zhao G, Xu C, Yin K., Label-free quantitative proteomic analyses of mouse astrocytes provides insight into the host response mechanism at different developmental stages of Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023. 2023 Sep 18;17(9). [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.M.; Jones, A.R.; Carmen, J.C.; Sinai, A.P.; Burchmore, R.; Wastling, J.M. Modulation of the Host Cell Proteome by the Intracellular Apicomplexan Parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 828–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntel, J.; Gandhi, T.; Verbeke, L.; Bernhardt, O.M.; Treiber, T.; Bruderer, R.; Reiter, L. Surpassing 10 000 identified and quantified proteins in a single run by optimizing current LC-MS instrumentation and data analysis strategy. Mol. Omics 2019, 15, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jungblut, P.R., et al., Proteomics in human disease: cancer, heart and infectious diseases. Electrophoresis, 1999. 20(10): p. 2100-10. [CrossRef]

- Beckers, C.J.; Roos, D.S.; Donald, R.G.; Luft, B.J.; Schwab, J.C.; Cao, Y.; A Joiner, K. Inhibition of cytoplasmic and organellar protein synthesis in Toxoplasma gondii. Implications for the target of macrolide antibiotics. J. Clin. Investig. 1995, 95, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.W.; Kafsack, B.F.C.; Cole, R.N.; Beckett, P.; Shen, R.F.; Carruthers, V.B. The Opportunistic Pathogen Toxoplasma gondii Deploys a Diverse Legion of Invasion and Survival Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 34233–34244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauquenoy, S.; Morelle, W.; Hovasse, A.; Bednarczyk, A.; Slomianny, C.; Schaeffer, C.; Van Dorsselaer, A.; Tomavo, S. Proteomics and Glycomics Analyses of N-Glycosylated Structures Involved in Toxoplasma gondii-Host Cell Interactions. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2008, 7, 891–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Bajalan, M.M.M.; Xia, D.; Armstrong, S.; Randle, N.; Wastling, J.M. Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum induce different host cell responses at proteome-wide phosphorylation events; a step forward for uncovering the biological differences between these closely related parasites. Parasitol. Res. 2017, 116, 2707–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.-X.; Gao, M.; Han, B.; Cong, H.; Zhu, X.-Q.; Zhou, H.-Y. Quantitative Peptidomics of Mouse Brain After Infection With Cyst-Forming Toxoplasma gondii. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 681242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Yin, K.; Xu, C.; Liu, G.; Xiao, T.; Huang, B.; Wei, Q.; Gong, M.; et al. Comparative Proteomics Analysis for Elucidating the Interaction Between Host Cells and Toxoplasma gondii. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hänggeli, K.P.A.; Hemphill, A.; Müller, N.; Heller, M.; Uldry, A.-C.; Braga-Lagache, S.; Müller, J.; Boubaker, G. Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Toxoplasma gondii RH Wild-Type and Four SRS29B (SAG1) Knock-Out Clones Reveals Significant Differences between Individual Strains. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubu, R.R.; de Monerri, N.C.S.; Nieves, E.; Kim, K.; Weiss, L.M. Comparative Monomethylarginine Proteomics Suggests that Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 1 (PRMT1) is a Significant Contributor to Arginine Monomethylation in Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2017, 16, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doliwa, C.; Xia, D.; Escotte-Binet, S.; Newsham, E.L.; J., S.S.; Aubert, D.; Randle, N.; Wastling, J.M.; Villena, I. Identification of differentially expressed proteins in sulfadiazine resistant and sensitive strains of Toxoplasma gondii using difference-gel electrophoresis (DIGE). Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2013, 3, 35–44. [CrossRef]

- Marugán-Hernández, V.; Álvarez-García, G.; Tomley, F.; Hemphill, A.; Regidor-Cerrillo, J.; Ortega-Mora, L. Identification of novel rhoptry proteins in Neospora caninum by LC/MS-MS analysis of subcellular fractions. J. Proteom. 2011, 74, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, S.; Vieira, C.; Mansouri, R.; Ali-Hassanzadeh, M.; Ghani, E.; Karimazar, M.; Nguewa, P.; Manzano-Román, R. Host cell proteins modulated upon Toxoplasma infection identified using proteomic approaches: a molecular rationale. Parasitol. Res. 2022, 121, 1853–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barylyuk, K.; Koreny, L.; Ke, H.; Butterworth, S.; Crook, O.M.; Lassadi, I.; Gupta, V.; Tromer, E.; Mourier, T.; Stevens, T.J.; et al. A Comprehensive Subcellular Atlas of the Toxoplasma Proteome via hyperLOPIT Provides Spatial Context for Protein Functions. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 752–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demichev, V.; Tober-Lau, P.; Lemke, O.; Nazarenko, T.; Thibeault, C.; Whitwell, H.; Röhl, A.; Freiwald, A.; Szyrwiel, L.; Ludwig, D.; et al. A time-resolved proteomic and prognostic map of COVID-19. Cell Syst. 2021, 12, 780–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herneisen, A.L., et al., Temporal and thermal profiling of the Toxoplasma proteome implicates parasite Protein Phosphatase 1 in the regulation of Ca2+-responsive pathways. Elife, 2022. 11. [CrossRef]

- Bernard, C.; Locard-Paulet, M.; Noël, C.; Duchateau, M.; Gianetto, Q.G.; Moumen, B.; Rattei, T.; Hechard, Y.; Jensen, L.J.; Matondo, M.; et al. A time-resolved multi-omics atlas of Acanthamoeba castellanii encystment. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zecha, J.; Bayer, F.P.; Wiechmann, S.; Woortman, J.; Berner, N.; Müller, J.; Schneider, A.; Kramer, K.; Abril-Gil, M.; Hopf, T.; et al. Decrypting drug actions and protein modifications by dose- and time-resolved proteomics. Science 2023, 380, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.-X.; Che, L.; Hu, R.-S.; Sun, X.-L. Comparative Phosphoproteomic Analysis of Sporulated Oocysts and Tachyzoites of Toxoplasma gondii Reveals Stage-Specific Patterns. Molecules 2022, 27, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakubu, R.R.; Weiss, L.M.; de Monerri, N.C.S. Post-translational modifications as key regulators of apicomplexan biology: insights from proteome-wide studies. Mol. Microbiol. 2017, 107, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laura Vanagas, D.M., Constanza Cristaldi, et al., Histone variant H2B.Z acetylation is necessary for maintenance of Toxoplasma gondii biological fitness. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech, 2023. 2023 Sep;1866(3):194943. [CrossRef]

- Bouchut, A.; Chawla, A.R.; Jeffers, V.; Hudmon, A.; Sullivan, W.J. Proteome-Wide Lysine Acetylation in Cortical Astrocytes and Alterations That Occur during Infection with Brain Parasite Toxoplasma gondii. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0117966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, H.I.; Grinfeld, D.; Giannakopulos, A.; Petzoldt, J.; Shanley, T.; Garland, M.; Denisov, E.; Peterson, A.C.; Damoc, E.; Zeller, M.; et al. Parallelized Acquisition of Orbitrap and Astral Analyzers Enables High-Throughput Quantitative Analysis. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 15656–15664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkel, J.M. Single-cell proteomics takes centre stage. Nature 2021, 597, 580–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.T. Single-cell Proteomics: Progress and Prospects. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2020, 19, 1739–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Yu, F.; Fulcher, J.M.; Williams, S.M.; Engbrecht, K.; Moore, R.J.; Clair, G.C.; Petyuk, V.; Nesvizhskii, A.I.; Zhu, Y. Evaluating Linear Ion Trap for MS3-Based Multiplexed Single-Cell Proteomics. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 1888–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, A.; Sing, J.C.; Gingras, A.-C.; Röst, H.L. Improving Phosphoproteomics Profiling Using Data-Independent Mass Spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 2022, 21, 1789–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Qiao, L. Data-independent acquisition proteomics methods for analyzing post-translational modifications. Proteomics 2022, 23, e2200046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulises H Guzman, A.M.D.V., Zilu Ye, Eugen Damoc, et al., Narrow-window DIA: Ultra-fast quantitative analysis of comprehensive proteomes with high sequencing depth. bioRxiv, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Birhanu, A.G. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics as an emerging tool in clinical laboratories. Clin. Proteom. 2023, 20, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, C.D.L.; Malchow, S.; Reich, S.; Steltgens, S.; Shuvaev, K.V.; Loroch, S.; Lorenz, C.; Sickmann, A.; Knobbe-Thomsen, C.B.; Tews, B.; et al. A sensitive and simple targeted proteomics approach to quantify transcription factor and membrane proteins of the unfolded protein response pathway in glioblastoma cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bentum, M. and M. Selbach, An Introduction to Advanced Targeted Acquisition Methods. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2021. 20: p. 100165. [CrossRef]

- Carrera, M.; Piñeiro, C.; Martinez, I. Proteomic Strategies to Evaluate the Impact of Farming Conditions on Food Quality and Safety in Aquaculture Products. Foods 2020, 9, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu C. C. Tsantilas K. A. Park J. Plubell D. L. Naicker P. Govender I et al. Mag-Net: Rapid Enrichment of Membrane-Bound Particles Enables High Coverage Quantitative Analysis of the Plasma Proteome. bioRxiv, 2023. p 2023.06.10.544439. [CrossRef]

- Heil, L.R.; Damoc, E.; Arrey, T.N.; Pashkova, A.; Denisov, E.; Petzoldt, J.; Peterson, A.C.; Hsu, C.; Searle, B.C.; Shulman, N.; et al. Evaluating the Performance of the Astral Mass Analyzer for Quantitative Proteomics Using Data-Independent Acquisition. J. Proteome Res. 2023, 22, 3290–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melby, J.A.; Brown, K.A.; Gregorich, Z.R.; Roberts, D.S.; Chapman, E.A.; Ehlers, L.E.; Gao, Z.; Larson, E.J.; Jin, Y.; Lopez, J.R.; et al. High sensitivity top–down proteomics captures single muscle cell heterogeneity in large proteoforms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023, 120, e2222081120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran, P.M.J.; Federspiel, J.D.; Sheng, X.; Cristea, I.M. Proteomics and integrative omic approaches for understanding host–pathogen interactions and infectious diseases. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2017, 13, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, I.R.; Aswad, L.; Stahl, M.; Kunold, E.; Post, F.; Erkers, T.; Struyf, N.; Mermelekas, G.; Joshi, R.N.; Gracia-Villacampa, E.; et al. Integrative multi-omics and drug response profiling of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell lines. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloehn, J., et al., Multi-omics analysis delineates the distinct functions of sub-cellular acetyl-CoA pools in Toxoplasma gondii. BMC Biol, 2020. 18(1): p. 67. [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.-B.; Cong, W.; He, J.-J.; Zheng, W.-B.; Zhu, X.-Q. Global proteomic profiling of multiple organs of cats (Felis catus) and proteome-transcriptome correlation during acute Toxoplasma gondii infection. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2022, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reel, P.S.; Reel, S.; Pearson, E.; Trucco, E.; Jefferson, E. Using machine learning approaches for multi-omics data analysis: A review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 49, 107739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangaré, L.O.; Alayi, T.D.; Westermann, B.; Hovasse, A.; Sindikubwabo, F.; Callebaut, I.; Werkmeister, E.; Lafont, F.; Slomianny, C.; Hakimi, M.-A.; et al. Unconventional endosome-like compartment and retromer complex in Toxoplasma gondii govern parasite integrity and host infection. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angel, S.O.; Figueras, M.J.; Alomar, M.L.; Echeverria, P.C.; Deng, B. Toxoplasma gondii Hsp90: potential roles in essential cellular processes of the parasite. Parasitology 2014, 141, 1138–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munera López J, A.A., Figueras MJ, Saldarriaga Cartagena AM, Hortua Triana MA, Diambra L, Vanagas L, Deng B, Moreno SNJ, Angel SO, Analysis of the Interactome of the Toxoplasma gondii Tgj1 HSP40 Chaperone.Proteomes. Proteomes, 2023. 2023 Mar 1;11(1):9. [CrossRef]

- Blank, M.L.; Xia, J.; Morcos, M.M.; Sun, M.; Cantrell, P.S.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, X.; Powell, C.J.; Yates, N.; Boulanger, M.J.; et al. Toxoplasma gondii association with host mitochondria requires key mitochondrial protein import machinery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anghel, N.; Müller, J.; Serricchio, M.; Jelk, J.; Bütikofer, P.; Boubaker, G.; Imhof, D.; Ramseier, J.; Desiatkina, O.; Păunescu, E.; et al. Cellular and Molecular Targets of Nucleotide-Tagged Trithiolato-Bridged Arene Ruthenium Complexes in the Protozoan Parasites Toxoplasma gondii and Trypanosoma brucei. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, J.; Boubaker, G.; Imhof, D.; Hänggeli, K.; Haudenschild, N.; Uldry, A.-C.; Braga-Lagache, S.; Heller, M.; Ortega-Mora, L.-M.; Hemphill, A. Differential Affinity Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry: A Suitable Tool to Identify Common Binding Proteins of a Broad-Range Antimicrobial Peptide Derived from Leucinostatin. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.-C.; Nie, L.-B.; Elsheikha, H.M.; Yin, F.-Y.; Zhu, X.-Q. Lysine crotonylation is widespread on proteins of diverse functions and localizations in Toxoplasma gondii. Parasitol. Res. 2021, 120, 1617–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.-M.; Ji, Y.-S.; Elashram, S.A.; Lu, Z.-M.; Liu, X.-Y.; Suo, X.; Chen, Q.-J.; Wang, H. Identification of antigenic proteins of Toxoplasma gondii RH strain recognized by human immunoglobulin G using immunoproteomics. J. Proteom. 2012, 77, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkel, O.; Kharkivska, Y.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, J. Proximity Labeling Techniques: A Multi-Omics Toolbox. Chem. – Asian J. 2021, 17, e202101240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, P.S.; Moon, A.S.; Pasquarelli, R.R.; Bell, H.N.; Torres, J.A.; Chen, A.L.; Sha, J.; Vashisht, A.A.; Wohlschlegel, J.A.; Bradley, P.J. IMC29 Plays an Important Role in Toxoplasma Endodyogeny and Reveals New Components of the Daughter-Enriched IMC Proteome. mBio 2023, 14, e0304222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cygan, A.M.; Beltran, P.M.J.; Mendoza, A.G.; Branon, T.C.; Ting, A.Y.; Carr, S.A.; Boothroyd, J.C. Proximity-Labeling Reveals Novel Host and Parasite Proteins at the Toxoplasma Parasitophorous Vacuole Membrane. mBio 2021, 12, e0026021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelberg, K.; Bechtel, T.; Michaud, C.; Weerapana, E.; Gubbels, M.-J. Proteomic characterization of the Toxoplasma gondii cytokinesis machinery portrays an expanded hierarchy of its assembly and function. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelberg, K., et al., The apical annuli of Toxoplasma gondii are composed of coiled-coil and signalling proteins embedded in the inner membrane complex sutures. Cell Microbiol, 2020. 22(1): p. e13112. [CrossRef]

- Nadipuram, S.M.; Thind, A.C.; Rayatpisheh, S.; Wohlschlegel, J.A.; Bradley, P.J. Proximity biotinylation reveals novel secreted dense granule proteins of Toxoplasma gondii bradyzoites. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0232552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, V.; Tomita, T.; Sugi, T.; Mayoral, J.; Han, B.; Yakubu, R.R.; Williams, T.; Horta, A.; Ma, Y.; Weiss, L.M. The Toxoplasma gondii Cyst Wall Interactome. mBio 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, L.; Mo, X.; Pan, M.; Shen, B.; Fang, R.; Hu, M.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, Y. Essential Functions of Calmodulin and Identification of Its Proximal Interacting Proteins in Tachyzoite-Stage Toxoplasma gondii via BioID Technology. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0136322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinkle-Mulcahy, L. Recent advances in proximity-based labeling methods for interactome mapping. F1000Research 2019, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samavarchi-Tehrani, P.; Samson, R.; Gingras, A.-C. Proximity Dependent Biotinylation: Key Enzymes and Adaptation to Proteomics Approaches. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2020, 19, 757–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, M., et al., Identification of Novel Dense-Granule Proteins in Toxoplasma gondii by Two Proximity-Based Biotinylation Approaches. J Proteome Res, 2019. 18(1): p. 319-330. [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.-Y.; Abdul-Majid, N.; Lau, Y.-L. Identification of Host Proteins Interacting with Toxoplasma gondii SAG1 by Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay. Acta Parasitol. 2019, 64, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.-Y.; Lau, Y.-L. Screening and identification of host proteins interacting with Toxoplasma gondii SAG2 by yeast two-hybrid assay. Parasites Vectors 2017, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, O.S. and D.S. Roos, ToxoDB: Functional Genomics Resource for Toxoplasma and Related Organisms. Methods Mol Biol, 2020. 2071: p. 27-47. [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Sanderson, S.J.; Jones, A.R.; Prieto, J.H.; Yates, J.R.; Bromley, E.; Tomley, F.M.; Lal, K.; E Sinden, R.; Brunk, B.P.; et al. The proteome of Toxoplasma gondii: integration with the genome provides novel insights into gene expression and annotation. Genome Biol. 2008, 9, R116–R116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Possenti, A., et al., Global proteomic analysis of the oocyst/sporozoite of Toxoplasma gondii reveals commitment to a host-independent lifestyle. BMC Genomics, 2013. 14: p. 183. [CrossRef]

- Krishna, R., et al., A large-scale proteogenomics study of apicomplexan pathogens-Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum. Proteomics, 2015. 15(15): p. 2618-28. [CrossRef]

- Garfoot, A.L.; Wilson, G.M.; Coon, J.J.; Knoll, L.J. Proteomic and transcriptomic analyses of early and late-chronic Toxoplasma gondii infection shows novel and stage specific transcripts. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardelli, S.C.; Che, F.-Y.; de Monerri, N.C.S.; Xiao, H.; Nieves, E.; Madrid-Aliste, C.; Angel, S.O.; Sullivan, W.J.; Angeletti, R.H.; Kim, K.; et al. The Histone Code of Toxoplasma gondii Comprises Conserved and Unique Posttranslational Modifications. mBio 2013, 4, e00922–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, H.E.; Russo, P.; Angulo, N.; Ynocente, R.; Montoya, C.; Diestra, A.; Ferradas, C.; Schiaffino, F.; Florentini, E.; Jimenez, J.; et al. Toward detection of toxoplasmosis from urine in mice using hydro-gel nanoparticles concentration and parallel reaction monitoring mass spectrometry. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biol. Med. 2017, 14, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, P.; Antil, N.; Kumar, M.; Yamaryo-Botté, Y.; Rawat, R.S.; Pinto, S.; Datta, K.K.; Katris, N.J.; Botté, C.Y.; Prasad, T.S.K.; et al. Protein kinase TgCDPK7 regulates vesicular trafficking and phospholipid synthesis in Toxoplasma gondii. PLOS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montano, H., et al., TgTKL4 Is a Novel Kinase That Plays an Important Role in Toxoplasma Morphology and Fitness. Msphere, 2023. 8(2). [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Doud, E.H.; Sampson, E.; Arrizabalaga, G. The protein phosphatase PPKL is a key regulator of daughter parasite development in Toxoplasma gondii. mBio 2023, 14, e0225423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.-X.; Hu, R.-S.; Zhu, X.-Q.; Sun, X.-L.; Elsheikha, H.M. Global phosphoproteome analysis reveals significant differences between sporulated oocysts of virulent and avirulent strains of Toxoplasma gondii. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 161, 105240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treeck, M.; Sanders, J.L.; Gaji, R.Y.; LaFavers, K.A.; Child, M.A.; Arrizabalaga, G.; Elias, J.E.; Boothroyd, J.C. The Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinase 3 of Toxoplasma Influences Basal Calcium Levels and Functions beyond Egress as Revealed by Quantitative Phosphoproteome Analysis. PLOS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero, M.C.; Alonso, A.M.; Deng, B.; Attias, M.; de Souza, W.; Corvi, M.M. Identification of new palmitoylated proteins in Toxoplasma gondii. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Proteins Proteom. 2016, 1864, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foe, I.T.; Child, M.A.; Majmudar, J.D.; Krishnamurthy, S.; van der Linden, W.A.; Ward, G.E.; Martin, B.R.; Bogyo, M. Global Analysis of Palmitoylated Proteins in Toxoplasma gondii. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 18, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zexiang Wang, J.L., Qianqian Yang and Xiaolin Sun, Global Proteome-Wide Analysis of Cysteine S-Nitrosylation in Toxoplasma gondii. molecules, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Treeck, M., et al., The Phosphoproteomes of Plasmmodium falciparum and Toxoplasma gondii Reveal Unusual Adaptations Within and Beyond the Parasites’ Boundaries. Cell Host & Microbe, 2011. 10(4): p. 410-419. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, D.A., et al., Protein kinases on carbon metabolism: potential targets for alternative chemotherapies against toxoplasmosis. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 2023. 13. [CrossRef]

- O’shaughnessy, W.J.; Dewangan, P.S.; Paiz, E.A.; Reese, M.L. Not your Mother’s MAPKs: Apicomplexan MAPK function in daughter cell budding. PLOS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaji, R.Y.; Sharp, A.K.; Brown, A.M. Protein kinases in Toxoplasma gondii. Int. J. Parasitol. 2021, 51, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Chaabene, R.; Lentini, G.; Soldati-Favre, D. Biogenesis and discharge of the rhoptries: Key organelles for entry and hijack of host cells by the Apicomplexa. Mol. Microbiol. 2020, 115, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triana, M.A.H.; Márquez-Nogueras, K.M.; Vella, S.A.; Moreno, S.N. Calcium signaling and the lytic cycle of the Apicomplexan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Res. 2018, 1865, 1846–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, M.J.; Augusto, L.d.S.; Zhang, M.; Wek, R.C.; Sullivan, W.J. Translational Control in the Latency of Apicomplexan Parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2017, 33, 947–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukri AH, L.V., Charih F, Biggar KK, Unraveling the battle for lysine: A review of the competition among post-translational modifications. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech, 2023. 2023 Sep 24;1866(4):194990. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Hao, Y.-H.; Orth, K. A newly discovered post-translational modification – the acetylation of serine and threonine residues. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007, 32, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, D.G.; Xie, X.; Basisty, N.; Byrnes, J.; McSweeney, S.; Schilling, B.; Wolfe, A.J. Post-translational Protein Acetylation: An Elegant Mechanism for Bacteria to Dynamically Regulate Metabolic Functions. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanagas, L., et al., Toxoplasma gondii histone acetylation remodelers as novel drug targets. Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy, 2012. 10(10): p. 1189-1201. [CrossRef]

- Bougdour, A.; Maubon, D.; Baldacci, P.; Ortet, P.; Bastien, O.; Bouillon, A.; Barale, J.-C.; Pelloux, H.; Ménard, R.; Hakimi, M.-A. Drug inhibition of HDAC3 and epigenetic control of differentiation in Apicomplexa parasites. J. Exp. Med. 2009, 206, 953–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darkin-Rattray, S.J.; Gurnett, A.M.; Myers, R.W.; Dulski, P.M.; Crumley, T.M.; Allocco, J.J.; Cannova, C.; Meinke, P.T.; Colletti, S.L.; Bednarek, M.A.; et al. Apicidin: A novel antiprotozoal agent that inhibits parasite histone deacetylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1996, 93, 13143–13147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissavy, T.; Rotili, D.; Mouveaux, T.; Roger, E.; Aliouat, E.M.; Pierrot, C.; Valente, S.; Mai, A.; Gissot, M. Hydroxamate-based compounds are potent inhibitors of Toxoplasma gondii HDAC biological activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2023, 67, e0066123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, H.; Cong, H.; Qu, Y. In vitro and in vivo anti−Toxoplasma activities of HDAC inhibitor Panobinostat on experimental acute ocular toxoplasmosis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1002817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jublot, D.; Cavaillès, P.; Kamche, S.; Francisco, D.; Fontinha, D.; Prudêncio, M.; Guichou, J.-F.; Labesse, G.; Sereno, D.; Loeuillet, C. A Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Inhibitor with Pleiotropic In Vitro Anti-Toxoplasma and Anti-Plasmodium Activities Controls Acute and Chronic Toxoplasma Infection in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo-Silva, C.A.; De Souza, W.; Martins-Duarte, E.S.; Vommaro, R.C. HDAC inhibitors Tubastatin A and SAHA affect parasite cell division and are potential anti-Toxoplasma gondii chemotherapeutics. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2020, 15, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouveaux, T.; Rotili, D.; Boissavy, T.; Roger, E.; Pierrot, C.; Mai, A.; Gissot, M. A potent HDAC inhibitor blocks Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoite growth and profoundly disrupts parasite gene expression. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2022, 59, 106526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras, S.M.; Ganuza, A.; Corvi, M.M.; Angel, S.O. Resveratrol induces H3 and H4K16 deacetylation and H2A.X phosphorylation in Toxoplasma gondii. BMC Res. Notes 2021, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffers, V.; Sullivan, W.J. Lysine Acetylation Is Widespread on Proteins of Diverse Function and Localization in the Protozoan Parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Eukaryot. Cell 2012, 11, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.-X.; Hu, R.-S.; Zhou, C.-X.; He, J.-J.; Elsheikha, H.M.; Zhu, X.-Q. Label-Free Quantitative Acetylome Analysis Reveals Toxoplasma gondii Genotype-Specific Acetylomic Signatures. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trempe, J.F., Reading the ubiquitin postal code. Current Opinion in Structural Biology, 2011. 21(6): p. 792-801. [CrossRef]

- Silmon de Monerri, N.C., et al., The Ubiquitin Proteome of Toxoplasma gondii Reveals Roles for Protein Ubiquitination in Cell-Cycle Transitions. Cell Host Microbe, 2015. 18(5): p. 621-33. [CrossRef]

- MacRae, J.I.; Sheiner, L.; Nahid, A.; Tonkin, C.; Striepen, B.; McConville, M.J. Mitochondrial Metabolism of Glucose and Glutamine Is Required for Intracellular Growth of Toxoplasma gondii. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 12, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimes, M.; Hall, B.; Foltz, L.; Levy, T.; Rikova, K.; Gaiser, J.; Cook, W.; Smirnova, E.; Wheeler, T.; Clark, N.R.; et al. Integration of protein phosphorylation, acetylation, and methylation data sets to outline lung cancer signaling networks. Sci. Signal. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, K.E.; Zhang, G.; Akcora, C.; Lin, Y.; Fang, B.; Koomen, J.; Haura, E.B.; Grimes, M. Network models of protein phosphorylation, acetylation, and ubiquitination connect metabolic and cell signaling pathways in lung cancer. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2023, 19, e1010690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Smith, E.; Shilatifard, A. The Language of Histone Crosstalk. Cell 2010, 142, 682–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbert, P.B.; Henikoff, S. The Yin and Yang of Histone Marks in Transcription. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2021, 22, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, D.; Jiang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Sang, X.; Feng, Y.; Chen, R.; Wang, X.; Yang, N.; Chen, Q. Global Lysine Crotonylation and 2-Hydroxyisobutyrylation in Phenotypically Different Toxoplasma gondii Parasites. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2019, 18, 2207–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras, S.M., et al., Architecture, Chromatin and Gene Organization of Toxoplasma gondii Subtelomeres. Epigenomes, 2022. 6(3). [CrossRef]

- Sindikubwabo, F., et al., Modifications at K31 on the lateral surface of histone H4 contribute to genome structure and expression in apicomplexan parasites. Elife, 2017. 6. [CrossRef]

- Dalmasso, M.C.; Onyango, D.O.; Naguleswaran, A.; Sullivan, W.J.; Angel, S.O. Toxoplasma H2A Variants Reveal Novel Insights into Nucleosome Composition and Functions for this Histone Family. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 392, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeijmakers, W.A., et al., H2A.Z/H2B.Z double-variant nucleosomes inhabit the AT-rich promoter regions of the Plasmodium falciparum genome. Mol Microbiol, 2013. 87(5): p. 1061-73. [CrossRef]

- Nardelli, S.C.; de Monerri, N.C.S.; Vanagas, L.; Wang, X.; Tampaki, Z.; Sullivan, W.J.; Angel, S.O.; Kim, K. Genome-wide localization of histone variants in Toxoplasma gondii implicates variant exchange in stage-specific gene expression. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizan S, S.S., Tang J, Jeninga MD, Schulz D, et al., The P. falciparum alternative histones Pf H2A.Z and Pf H2B.Z are dynamically acetylated and antagonized by PfSir2 histone deacetylases at heterochromatin boundaries. mBio, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bougdour, A.; Braun, L.; Cannella, D.; Hakimi, M.-A. Chromatin modifications: implications in the regulation of gene expression in Toxoplasma gondii. Cell. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saksouk, N.; Bhatti, M.M.; Kieffer, S.; Smith, A.T.; Musset, K.; Garin, J.; Sullivan, W.J.; Cesbron-Delauw, M.-F.; Hakimi, M.-A. Histone-Modifying Complexes Regulate Gene Expression Pertinent to the Differentiation of the Protozoan Parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 10379–10390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-S.; Shukla, A.; Schneider, J.; Swanson, S.K.; Washburn, M.P.; Florens, L.; Bhaumik, S.R.; Shilatifard, A. Histone Crosstalk between H2B Monoubiquitination and H3 Methylation Mediated by COMPASS. Cell 2007, 131, 1084–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakanishi, S.; Lee, J.S.; Gardner, K.E.; Gardner, J.M.; Takahashi, Y.-H.; Chandrasekharan, M.B.; Sun, Z.-W.; Osley, M.A.; Strahl, B.D.; Jaspersen, S.L.; et al. Histone H2BK123 monoubiquitination is the critical determinant for H3K4 and H3K79 trimethylation by COMPASS and Dot1. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 186, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Davey, M.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Kaplanek, P.; Tong, A.; Parsons, A.B.; Krogan, N.; Cagney, G.; Mai, D.; Greenblatt, J.; et al. Navigating the Chaperone Network: An Integrative Map of Physical and Genetic Interactions Mediated by the Hsp90 Chaperone. Cell 2005, 120, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipale, M.; Tucker, G.; Peng, J.; Krykbaeva, I.; Lin, Z.-Y.; Larsen, B.; Choi, H.; Berger, B.; Gingras, A.-C.; Lindquist, S. A Quantitative Chaperone Interaction Network Reveals the Architecture of Cellular Protein Homeostasis Pathways. Cell 2014, 158, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawarkar, R.; Paro, R. Hsp90@chromatin.nucleus: an emerging hub of a networker. Trends Cell Biol. 2013, 23, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backe, S.J.; Sager, R.A.; Woodford, M.R.; Makedon, A.M.; Mollapour, M. Post-translational modifications of Hsp90 and translating the chaperone code. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 11099–11117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagar, M.; Singh, J.P.; Dagar, G.; Tyagi, R.K.; Bagchi, G. Phosphorylation of HSP90 by protein kinase A is essential for the nuclear translocation of androgen receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 8699–8710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Lu, X.-A.; Song, X.; Zhuo, W.; Jia, L.; Jiang, Y.; Luo, Y. Thr90 phosphorylation of Hsp90α by protein kinase A regulates its chaperone machinery. Biochem. J. 2011, 441, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solier, S.; Kohn, K.W.; Scroggins, B.; Xu, W.; Trepel, J.; Neckers, L.; Pommier, Y. Heat shock protein 90α (HSP90α), a substrate and chaperone of DNA-PK necessary for the apoptotic response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 12866–12872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, S.H.; An, S.; Lee, H.-C.; Jin, H.-O.; Seo, S.-K.; Yoo, D.-H.; Lee, K.-H.; Rhee, C.H.; Choi, E.-J.; Hong, S.-I.; et al. A Truncated Form of p23 Down-regulates Telomerase Activity via Disruption of Hsp90 Function. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 30871–30880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scroggins, B.T.; Robzyk, K.; Wang, D.; Marcu, M.G.; Tsutsumi, S.; Beebe, K.; Cotter, R.J.; Felts, S.; Toft, D.; Karnitz, L.; et al. An Acetylation Site in the Middle Domain of Hsp90 Regulates Chaperone Function. Mol. Cell 2007, 25, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Rao, R.; Shen, J.; Tang, Y.; Fiskus, W.; Nechtman, J.; Atadja, P.; Bhalla, K. Role of Acetylation and Extracellular Location of Heat Shock Protein 90α in Tumor Cell Invasion. Cancer Res 2008, 68, 4833–4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, P.; Ruckova, E.; Halada, P.; Coates, P.J.; Hrstka, R.; Lane, D.P.; Vojtesek, B. C-terminal phosphorylation of Hsp70 and Hsp90 regulates alternate binding to co-chaperones CHIP and HOP to determine cellular protein folding/degradation balances. Oncogene 2012, 32, 3101–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Johnson, J.; Florens, L.; Fraunholz, M.; Suravajjala, S.; DiLullo, C.; Yates, J.; Roos, D.S.; Murray, J.M. Cytoskeletal Components of an Invasion Machine—The Apical Complex of Toxoplasma gondii. PLOS Pathog. 2006, 2, e13–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Flores, C.J.; Cruz-Mirón, R.; Mondragón-Castelán, M.E.; González-Pozos, S.; Ríos-Castro, E.; Mondragón-Flores, R. Proteomic and structural characterization of self-assembled vesicles from excretion/secretion products of Toxoplasma gondii. J. Proteom. 2019, 208, 103490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wowk, P.F.; Zardo, M.L.; Miot, H.T.; Goldenberg, S.; Carvalho, P.C.; Mörking, P.A. Proteomic profiling of extracellular vesicles secreted from Toxoplasma gondii. Proteomics 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, V.; Mayoral, J.; Sugi, T.; Tomita, T.; Han, B.; Ma, Y.F.; Weiss, L.M. Enrichment and Proteomic Characterization of the Cyst Wall from In Vitro Toxoplasma gondii Cysts. mBio 2019, 10, e00469–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, P.J.; Ward, C.; Cheng, S.J.; Alexander, D.L.; Coller, S.; Coombs, G.H.; Dunn, J.D.; Ferguson, D.J.; Sanderson, S.J.; Wastling, J.M.; et al. Proteomic Analysis of Rhoptry Organelles Reveals Many Novel Constituents for Host-Parasite Interactions in Toxoplasma gondii. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 34245–34258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleige, T.; Pfaff, N.; Gross, U.; Bohne, W. Localisation of gluconeogenesis and tricarboxylic acid (TCA)-cycle enzymes and first functional analysis of the TCA cycle in Toxoplasma gondii. Int. J. Parasitol. 2008, 38, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidi, A., et al., Elucidating the mitochondrial proteome of Toxoplasma gondii reveals the presence of a divergent cytochrome c oxidase. Elife, 2018. 7. [CrossRef]

- Elzek, M.A.W., et al., Localization of Organelle Proteins by Isotope Tagging: Current status and potential applications in drug discovery research. Drug Discov Today Technol, 2021. 39: p. 57-67. [CrossRef]

- Hajj, R.E., et al., Toxoplasmosis: Current and Emerging Parasite Druggable Targets. Microorganisms, 2021. 9(12). [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, S.; Sánchez-Montejo, J.; Mansouri, R.; Ali-Hassanzadeh, M.; Savardashtaki, A.; Bahreini, M.S.; Karimazar, M.; Manzano-Román, R.; Nguewa, P. Mining the Proteome of Toxoplasma Parasites Seeking Vaccine and Diagnostic Candidates. Animals 2022, 12, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stryiński, R.; Łopieńska-Biernat, E.; Carrera, M. Proteomic Insights into the Biology of the Most Important Foodborne Parasites in Europe. Foods 2020, 9, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, J.; Hemphill, A. Toxoplasma gondii infection: novel emerging therapeutic targets. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2023, 27, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabou, M.; Doderer-Lang, C.; Leyer, C.; Konjic, A.; Kubina, S.; Lennon, S.; Rohr, O.; Viville, S.; Cianférani, S.; Candolfi, E.; et al. Toxoplasma gondii ROP16 kinase silences the cyclin B1 gene promoter by hijacking host cell UHRF1-dependent epigenetic pathways. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 77, 2141–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Hemphill, A. Drug target identification in protozoan parasites. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2016, 11, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, R.S.; Briggs, E.M.; Colon, B.L.; Alvarez, C.; Pereira, S.S.; De Niz, M. Paving the Way: Contributions of Big Data to Apicomplexan and Kinetoplastid Research. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 900878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benns, H.J.; Storch, M.; Falco, J.A.; Fisher, F.R.; Tamaki, F.; Alves, E.; Wincott, C.J.; Milne, R.; Wiedemar, N.; Craven, G.; et al. CRISPR-based oligo recombineering prioritizes apicomplexan cysteines for drug discovery. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 1891–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freville, A., et al., Deciphering the Role of Protein Phosphatases in Apicomplexa: The Future of Innovative Therapeutics? Microorganisms, 2022. 10(3). [CrossRef]

- Broncel, M., et al., Profiling of myristoylation in Toxoplasma gondii reveals an N-myristoylated protein important for host cell penetration. Elife, 2020. 9. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Tang, X.; Wu, M.; Hou, S.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Deng, M.; Huang, S.; Jiang, L. Anti-Toxoplasma gondii Effects of a Novel Spider Peptide XYP1 In Vitro and In Vivo. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, F.-Y.; Madrid-Aliste, C.; Burd, B.; Zhang, H.; Nieves, E.; Kim, K.; Fiser, A.; Angeletti, R.H.; Weiss, L.M. Comprehensive Proteomic Analysis of Membrane Proteins in Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2011, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maran, S.R.; Fleck, K.; Monteiro-Teles, N.M.; Isebe, T.; Walrad, P.; Jeffers, V.; Cestari, I.; Vasconcelos, E.J.; Moretti, N. Protein acetylation in the critical biological processes in protozoan parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2021, 37, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, E.A.; Pamukcu, S.; Cerutti, A.; Berry, L.; Lemaire-Vieille, C.; Yamaryo-Botté, Y.; Botté, C.Y.; Besteiro, S. Disrupting the plastidic iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis pathway in Toxoplasma gondii has pleiotropic effects irreversibly impacting parasite viability. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lee, E.-G.; Yu, L.; Kawano, S.; Huang, P.; Liao, M.; Kawase, O.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, J.; Fujisaki, K.; et al. Identification of the cross-reactive and species-specific antigens between Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites by a proteomics approach. Parasitol. Res. 2011, 109, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, V.A.; López, E.F.S.; Morales, L.M.; Duarte, V.A.R.; Corigliano, M.G.; Clemente, M. Use of Veterinary Vaccines for Livestock as a Strategy to Control Foodborne Parasitic Diseases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajazeiro, D.C.; Toledo, P.P.M.; de Sousa, N.F.; Scotti, M.T.; Reimão, J.Q. Drug Repurposing Based on Protozoan Proteome: In Vitro Evaluation of In Silico Screened Compounds against Toxoplasma gondii. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazeri, M.; Mehrzadi, S.; Sharif, M.; Sarvi, S.; Tanzifi, A.; Aghayan, S.A.; Daryani, A. Drug Resistance in Toxoplasma gondii. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thabet, A., et al., Resistance towards monensin is proposed to be acquired in a Toxoplasma gondii model by reduced invasion and egress activities, in addition to increased intracellular replication. Parasitology, 2018. 145(3): p. 313-325. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Ning, D.; Sun, H.; Li, R.; Shang, M.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, W.; Liang, C.; Li, W.; et al. Sequence Analysis and Molecular Characterization of Clonorchis sinensis Hexokinase, an Unusual Trimeric 50-kDa Glucose-6-Phosphate-Sensitive Allosteric Enzyme. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e107940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, S.; Nice, E.C.; Deutsch, E.W.; Lane, L.; Omenn, G.S.; Pennington, S.R.; Paik, Y.-K.; Overall, C.M.; Corrales, F.J.; Cristea, I.M.; et al. A high-stringency blueprint of the human proteome. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Li, C.; Li, X.; Ehsan, M.; Lu, M.; Li, K.; Xu, L.; Yan, R.; Song, X.; Li, X. Proteomics analysis reveals that the proto-oncogene eIF-5A indirectly influences the growth, invasion and replication of Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoite. Parasites Vectors 2021, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.W.; Blackman, M.J.; Howell, S.A.; Carruthers, V.B. Proteomic Analysis of Cleavage Events Reveals a Dynamic Two-step Mechanism for Proteolysis of a Key Parasite Adhesive Complex. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2004, 3, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.F., et al., Identification of a TNF-α inducer MIC3 originating from the microneme of non-cystogenic, virulent. Scientific Reports, 2016. 6. [CrossRef]

- Kawase, O.; Nishikawa, Y.; Bannai, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, G.; Jin, S.; Lee, E.-G.; Xuan, X. Proteomic analysis of calcium-dependent secretion in Toxoplasma gondii. Proteomics 2007, 7, 3718–3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaffari, A.D., et al., Immunoinformatic analysis of immunogenic B- and T-cell epitopes of MIC4 protein to designing a vaccine candidate against Toxoplasma gondii through an in-silico approach. Clinical and Experimental Vaccine Research, 2021. 10(1): p. 59-77. [CrossRef]

- Dogga, S.K., et al., A druggable secretory protein maturase of Toxoplasma essential for invasion and egress. Elife, 2017. 6. [CrossRef]

- Ferra, B.; Holec-Gąsior, L.; Grąźlewska, W. Toxoplasma gondii Recombinant Antigens in the Serodiagnosis of Toxoplasmosis in Domestic and Farm Animals. Animals 2020, 10, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, P.J.; Sibley, L.D. Rhoptries: an arsenal of secreted virulence factors. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2007, 10, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Hajj, H.; Demey, E.; Poncet, J.; Lebrun, M.; Wu, B.; Galéotti, N.; Fourmaux, M.N.; Mercereau-Puijalon, O.; Vial, H.; Labesse, G.; et al. The ROP2 family ofToxoplasma gondii rhoptry proteins: Proteomic and genomic characterization and molecular modeling. Proteomics 2006, 6, 5773–5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antil, N.; Kumar, M.; Behera, S.K.; Arefian, M.; Kotimoole, C.N.; Rex, D.A.B.; Prasad, T.S.K. Unraveling Toxoplasma gondii GT1 Strain Virulence and New Protein-Coding Genes with Proteogenomic Analyses. OMICS: A J. Integr. Biol. 2021, 25, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.X., et al., iTRAQ-Based Global Phosphoproteomics Reveals Novel Molecular Differences Between Toxoplasma gondii Strains of Different Genotypes. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 2019. 9. [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, J.; Sakura, T.; Matsubara, R.; Tahara, M.; Matsuzaki, M.; Nagamune, K. Rhoptry kinase protein 39 (ROP39) is a novel factor that recruits host mitochondria to the parasitophorous vacuole of Toxoplasma gondii. Biol. Open 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echeverria, P.C.; Figueras, M.J.; Vogler, M.; Kriehuber, T.; de Miguel, N.; Deng, B.; Dalmasso, M.C.; Matthews, D.E.; Matrajt, M.; Haslbeck, M.; et al. The Hsp90 co-chaperone p23 of Toxoplasma gondii: Identification, functional analysis and dynamic interactome determination. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2010, 172, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, H.M.; Bowyer, P.W.; Bogyo, M.; Conrad, P.A.; Boothroyd, J.C. Proteomic Analysis of Fractionated Toxoplasma Oocysts Reveals Clues to Their Environmental Resistance. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e29955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangaré, L.O., et al., Toxoplasma GRA15 Activates the NF-κB Pathway through Interactions with TNF Receptor-Associated Factors. Mbio, 2019. 10(4). [CrossRef]

- Fox, B.A.; Rommereim, L.M.; Guevara, R.B.; Falla, A.; Triana, M.A.H.; Sun, Y.; Bzik, D.J. The Toxoplasma gondii Rhoptry Kinome Is Essential for Chronic Infection. mBio 2016, 7, e00193–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Mirón, R.; Ramírez-Flores, C.J.; Lagunas-Cortés, N.; Mondragón-Castelán, M.; Ríos-Castro, E.; González-Pozos, S.; Aguirre-García, M.M.; Mondragón-Flores, R. Proteomic characterization of the pellicle of Toxoplasma gondii. J. Proteom. 2021, 237, 104146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, G.-Y.; Zhang, J.-Z.; Yin, G.-R.; Meng, X.-L.; Zhao, F. Toxoplasma gondii: Proteomic analysis of antigenicity of soluble tachyzoite antigen. Exp. Parasitol. 2009, 122, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.H., et al., Comparative proteomic analysis of different Toxoplasma gondii genotypes by two-dimensional fluorescence difference gel electrophoresis combined with mass spectrometry. Electrophoresis, 2014. 35(4): p. 533-45. [CrossRef]

- Leal-Sena, J.A., et al., Toxoplasma gondii antigen SAG2A differentially modulates IL-1beta expression in resistant and susceptible murine peritoneal cells. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2018. 102(5): p. 2235-2249. [CrossRef]

- He, C., et al., iTRAQ-Based Phosphoproteomic Analysis of Toxoplasma gondii Tachyzoites Provides Insight Into the Role of Phosphorylation for its Invasion and Egress. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 2020. 10. [CrossRef]

- Lockyer, E.J.; Torelli, F.; Butterworth, S.; Song, O.-R.; Howell, S.; Weston, A.; East, P.; Treeck, M. A heterotrimeric complex of Toxoplasma proteins promotes parasite survival in interferon gamma-stimulated human cells. PLOS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffey, M.J.; Dagley, L.F.; Seizova, S.; Kapp, E.A.; Infusini, G.; Roos, D.S.; Boddey, J.A.; Webb, A.I.; Tonkin, C.J. Aspartyl Protease 5 Matures Dense Granule Proteins That Reside at the Host-Parasite Interface in Toxoplasma gondii. mBio 2018, 9, e01796–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayoral, J.; Tomita, T.; Tu, V.; Aguilan, J.T.; Sidoli, S.; Weiss, L.M. Toxoplasma gondii PPM3C, a secreted protein phosphatase, affects parasitophorous vacuole effector export. PLOS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cygan, A.M., et al., Coimmunoprecipitation with MYR1 Identifies Three Additional Proteins within the Toxoplasma gondii Parasitophorous Vacuole Required for Translocation of Dense Granule Effectors into Host Cells. Msphere, 2020. 5(1). [CrossRef]

- Nadipuram, S.M.; Kim, E.W.; Vashisht, A.A.; Lin, A.H.; Bell, H.N.; Coppens, I.; Wohlschlegel, J.A.; Bradley, P.J. In Vivo Biotinylation of the Toxoplasma Parasitophorous Vacuole Reveals Novel Dense Granule Proteins Important for Parasite Growth and Pathogenesis. mBio 2016, 7, e00808–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.C.; Broncel, M.; Teague, H.; Russell, M.R.G.; McGovern, O.L.; Renshaw, M.; Frith, D.; Snijders, A.P.; Collinson, L.; Carruthers, V.B.; et al. Phosphorylation of Toxoplasma gondii Secreted Proteins during Acute and Chronic Stages of Infection. mSphere 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayoral, J.; Guevara, R.B.; Rivera-Cuevas, Y.; Tu, V.; Tomita, T.; Romano, J.D.; Gunther-Cummins, L.; Sidoli, S.; Coppens, I.; Carruthers, V.B.; et al. Dense Granule Protein GRA64 Interacts with Host Cell ESCRT Proteins during Toxoplasma gondii Infection. mBio 2022, 13, e0144222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercer, H.L.; Snyder, L.M.; Doherty, C.M.; Fox, B.A.; Bzik, D.J.; Denkers, E.Y. Toxoplasma gondii dense granule protein GRA24 drives MyD88-independent p38 MAPK activation, IL-12 production and induction of protective immunity. PLOS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shastri, A.J.; Marino, N.D.; Franco, M.; Lodoen, M.B.; Boothroyd, J.C. GRA25 Is a Novel Virulence Factor of Toxoplasma gondii and Influences the Host Immune Response. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 2595–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bougdour, A.; Durandau, E.; Brenier-Pinchart, M.-P.; Ortet, P.; Barakat, M.; Kieffer, S.; Curt-Varesano, A.; Curt-Bertini, R.-L.; Bastien, O.; Coute, Y.; et al. Host Cell Subversion by Toxoplasma GRA16, an Exported Dense Granule Protein that Targets the Host Cell Nucleus and Alters Gene Expression. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 13, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elizabeth, N. Rudzki, S.E.A., Rachel S. Coombs, et al., Toxoplasma gondiiGRA28 Is Required for Placenta-Specific Induction of the Regulatory Chemokine CCL22 in Human and Mouse. mBio, 2021. 2021 Nov-Dec; 12(6): e01591-21(2021 Nov-Dec; 12(6): e01591-21). [CrossRef]

- Takemae, H.; Sugi, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Gong, H.; Ishiwa, A.; Recuenco, F.C.; Murakoshi, F.; Iwanaga, T.; Inomata, A.; Horimoto, T.; et al. Characterization of the interaction between Toxoplasma gondii rhoptry neck protein 4 and host cellular β-tubulin. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poukchanski, A.; Fritz, H.M.; Tonkin, M.L.; Treeck, M.; Boulanger, M.J.; Boothroyd, J.C. Toxoplasma gondii Sporozoites Invade Host Cells Using Two Novel Paralogues of RON2 and AMA1. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e70637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Leon, C.T.G., et al., Proteomic characterization of the subpellicular cytoskeleton of Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites. Journal of Proteomics, 2014. 111: p. 86-99. [CrossRef]

- Vigetti, L.; Labouré, T.; Roumégous, C.; Cannella, D.; Touquet, B.; Mayer, C.; Couté, Y.; Frénal, K.; Tardieux, I.; Renesto, P. The BCC7 Protein Contributes to the Toxoplasma Basal Pole by Interfacing between the MyoC Motor and the IMC Membrane Network. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumégous, C.; Hammoud, A.A.; Fuster, D.; Dupuy, J.-W.; Blancard, C.; Salin, B.; Robinson, D.R.; Renesto, P.; Tardieux, I.; Frénal, K. Identification of new components of the basal pole of Toxoplasma gondii provides novel insights into its molecular organization and functions. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1010038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C., et al., iTRAQ-based phosphoproteomic analysis reveals host cell’s specific responses to Toxoplasma gondii at the phases of invasion and prior to egress. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Proteins and Proteomics, 2019. 1867(3): p. 202-212. [CrossRef]

- Rompikuntal, P.K.; Kent, R.S.; Foe, I.T.; Deng, B.; Bogyo, M.; Ward, G.E. Blocking Palmitoylation of Toxoplasma gondii Myosin Light Chain 1 Disrupts Glideosome Composition but Has Little Impact on Parasite Motility. mSphere 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Martín, R.D.; Mercier, C.; de León, C.T.G.; González, R.M.; Pozos, S.G.; Ríos-Castro, E.; García, R.A.; Fox, B.A.; Bzik, D.J.; Flores, R.M. The dense granule protein 8 (GRA8) is a component of the sub-pellicular cytoskeleton in Toxoplasma gondii. Parasitol. Res. 2019, 118, 1899–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, M.; Ge, C.-C.; Fan, Y.-M.; Jin, Q.-W.; Shen, B.; Huang, S.-Y. The determinants regulating Toxoplasma gondii bradyzoite development. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1027073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.-L.; Li, T.-T.; Elsheikha, H.M.; Liang, Q.-L.; Zhang, Z.-W.; Wang, M.; Sibley, L.D.; Zhu, X.-Q. The protein phosphatase 2A holoenzyme is a key regulator of starch metabolism and bradyzoite differentiation in Toxoplasma gondii. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pamukcu, S.; Cerutti, A.; Bordat, Y.; Hem, S.; Rofidal, V.; Besteiro, S. Differential contribution of two organelles of endosymbiotic origin to iron-sulfur cluster synthesis and overall fitness in Toxoplasma. PLOS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1010096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerutti, A.; Blanchard, N.; Besteiro, S. The Bradyzoite: A Key Developmental Stage for the Persistence and Pathogenesis of Toxoplasmosis. Pathogens 2020, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandeep Srivastava, M.W.W., William J. Sullivan, Jr., Toxoplasma gondii AP2XII-2 Contributes to Proper Progression through S-Phase of the Cell Cycle. mSphere, 2020. 2020 Sep-Oct; 5(5): e00542-20.

- Chen, Y.; Yang, L.-N.; Cheng, L.; Tu, S.; Guo, S.-J.; Le, H.-Y.; Xiong, Q.; Mo, R.; Li, C.-Y.; Jeong, J.-S.; et al. Bcl2-associated Athanogene 3 Interactome Analysis Reveals a New Role in Modulating Proteasome Activity. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2013, 12, 2804–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomita, T.; Bzik, D.J.; Ma, Y.F.; Fox, B.A.; Markillie, L.M.; Taylor, R.C.; Kim, K.; Weiss, L.M. The Toxoplasma gondii Cyst Wall Protein CST1 Is Critical for Cyst Wall Integrity and Promotes Bradyzoite Persistence. PLOS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.O.O., et al., IMC10 and LMF1 mediate mitochondrial morphology through mitochondrion-pellicle contact sites in Toxoplasma gondii. Journal of Cell Science, 2022. 135(22). [CrossRef]

- Koreny, L., et al., Molecular characterization of the conoid complex in Toxoplasma gondii reveals its conservation in all apicomplexans, including Plasmodium species. Plos Biology, 2021. 19(3). [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.M.; Jones, A.R.; Carmen, J.C.; Sinai, A.P.; Burchmore, R.; Wastling, J.M. Modulation of the Host Cell Proteome by the Intracellular Apicomplexan Parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 828–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, C. Gretes, L.B.P., P. Andrew Karplus. Peroxiredoxins in Parasites. Antioxid Redox Signal. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2012. 2012 Aug 15; 17(4): 608–633. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Xiao, Q.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, X. Involvement of Urm1, a Ubiquitin-Like Protein, in the Regulation of Oxidative Stress Response of Toxoplasma gondii. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0239421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Schlange, C.; Heller, M.; Uldry, A.-C.; Braga-Lagache, S.; Haynes, R.K.; Hemphill, A. Proteomic characterization of Toxoplasma gondii ME49 derived strains resistant to the artemisinin derivatives artemiside and artemisone implies potential mode of action independent of ROS formation. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2022, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.-H.; Wang, Z.-X.; Zhou, C.-X.; He, S.; Elsheikha, H.M.; Zhu, X.-Q. Comparative proteomic analysis of virulent and avirulent strains of Toxoplasma gondii reveals strain-specific patterns. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 80481–80491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, C.R.; Sidik, S.M.; Petrova, B.; Gnädig, N.F.; Okombo, J.; Herneisen, A.L.; Ward, K.E.; Markus, B.M.; Boydston, E.A.; Fidock, D.A.; et al. Genetic screens reveal a central role for heme metabolism in artemisinin susceptibility. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.X., et al., Global iTRAQ-based proteomic profiling of Toxoplasma gondii oocysts during sporulation. Journal of Proteomics, 2016. 148: p. 12-19. [CrossRef]

- He, J.-J.; Ma, J.; Elsheikha, H.M.; Song, H.-Q.; Zhou, D.-H.; Zhu, X.-Q. Proteomic Profiling of Mouse Liver following Acute Toxoplasma gondii Infection. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0152022–e0152022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moog, D.; Przyborski, J.M.; Maier, U.G. Genomic and Proteomic Evidence for the Presence of a Peroxisome in the Apicomplexan Parasite Toxoplasma gondii and Other Coccidia. Genome Biol. Evol. 2017, 9, 3108–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, L.-B.; Liang, Q.-L.; Elsheikha, H.M.; Du, R.; Zhu, X.-Q.; Li, F.-C. Global profiling of lysine 2-hydroxyisobutyrylome in Toxoplasma gondii using affinity purification mass spectrometry. Parasitol. Res. 2020, 119, 4061–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, N.; Guo, X.; Guo, Q.; Gupta, N.; Ji, N.; Shen, B.; Xiao, L.; Feng, Y. Metabolic flexibilities and vulnerabilities in the pentose phosphate pathway of the zoonotic pathogen Toxoplasma gondii. PLOS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendran, E.; Clark, M.; Goulart, C.; Steinhöfel, B.; Tjhin, E.T.; Gross, S.; Smith, N.C.; Kirk, K.; van Dooren, G.G. Substrate-mediated regulation of the arginine transporter of Toxoplasma gondii. PLOS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallbank, B.A.; Dominicus, C.S.; Broncel, M.; Legrave, N.; Kelly, G.; MacRae, J.I.; Staines, H.M.; Treeck, M. Characterisation of the Toxoplasma gondii tyrosine transporter and its phosphorylation by the calcium-dependent protein kinase 3. Mol. Microbiol. 2018, 111, 1167–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, D.; Schott, B.H.; van Ham, M.; Morton, L.; Kulikovskaja, L.; Herrera-Molina, R.; Pielot, R.; Klawonn, F.; Montag, D.; Jänsch, L.; et al. Chronic Toxoplasma infection is associated with distinct alterations in the synaptic protein composition. J. Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daher, D.; Shaghlil, A.; Sobh, E.; Hamie, M.; Hassan, M.E.; Moumneh, M.B.; Itani, S.; El Hajj, R.; Tawk, L.; El Sabban, M.; et al. Comprehensive Overview of Toxoplasma gondii-Induced and Associated Diseases. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayoral, J., P. Shamamian, Jr., and L.M. Weiss, In Vitro Characterization of Protein Effector Export in the Bradyzoite Stage of Toxoplasma gondii. mBio, 2020. 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Gay, G., et al., Toxoplasma gondii TgIST co-opts host chromatin repressors dampening STAT1-dependent gene regulation and IFN-gamma-mediated host defenses. J Exp Med, 2016. 213(9): p. 1779-98. [CrossRef]

- Alex W Chan, M.B., Nicole Haseley, et al., Analysis of CDPK1 targets identifies a trafficking adaptor complex that regulates microneme exocytosis in Toxoplasma. bioRxiv, 2023. 2023 Jan 12. [CrossRef]

- Uboldi AD, M.J., Blume M, Gerlic M, Ferguson DJ, et al., Regulation of Starch Stores by a Ca(2+)-Dependent Protein Kinase Is Essential for Viable Cyst Development in Toxoplasma gondii. Cell Host Microbe, 2015. 18(6):670-81. [CrossRef]

- Nofal, S.D.; Dominicus, C.; Broncel, M.; Katris, N.J.; Flynn, H.R.; Arrizabalaga, G.; Botté, C.Y.; Invergo, B.M.; Treeck, M. A positive feedback loop mediates crosstalk between calcium, cyclic nucleotide and lipid signalling in calcium-induced Toxoplasma gondii egress. PLOS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Andenmatten, N.; Triana, M.A.H.; Deng, B.; Meissner, M.; Moreno, S.N.J.; Ballif, B.A.; Ward, G.E. Calcium-dependent phosphorylation alters class XIVa myosin function in the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 2579–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brossier, F.; Starnes, G.L.; Beatty, W.L.; Sibley, L.D. Microneme Rhomboid Protease TgROM1 Is Required for Efficient Intracellular Growth of Toxoplasma gondii. Eukaryot. Cell 2008, 7, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamurthy, S.; Deng, B.; del Rio, R.; Buchholz, K.R.; Treeck, M.; Urban, S.; Boothroyd, J.; Lam, Y.-W.; Ward, G.E. Not a Simple Tether: Binding of Toxoplasma gondii AMA1 to RON2 during Invasion Protects AMA1 from Rhomboid-Mediated Cleavage and Leads to Dephosphorylation of Its Cytosolic Tail. mBio 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Child, M.A.; Bogyo, M. Proteases as regulators of pathogenesis: Examples from the Apicomplexa. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Proteins Proteom. 2012, 1824, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Upadhya, R.; Zhang, H.; Madrid-Aliste, C.; Nieves, E.; Kim, K.; Angeletti, R.H.; Weiss, L.M. Analysis of the glycoproteome of Toxoplasma gondii using lectin affinity chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry. Microbes Infect. 2011, 13, 1199–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Protein Group | Functions | Selected References |

|---|---|---|

| Microneme Protein (MIC) | Host cell adhesion and invasion are critical for the efficient invasion and attachment of T. gondii to host cells | 26, 29, 124, 163, 172, 175-181 |

| Rhoptry Proteins (ROP) | Host cell invasion and manipulation | 3, 4, 26, 29, 93, 124, 147, 175, 178, 182-190 |

| Surface Antigen (SAG) Proteins | Initial host cell invasion | 27, 87, 186, 191-194 |

| Dense Granule Antigens (GRA) | Modulation of host cell processes, immune evasion, and nutrient acquisition | 26, 29, 70, 73, 87, 147, 149, 175, 184, 195-206 |

| Rhoptry Neck (RON) Proteins | Manipulating host cell signaling pathways, and interacting with host cellular components during invasion | 180, 182, 207, 208 |

| Cytoskeletal Proteins | Facilitating the movement of the parasite and the rearrangement of the host cell’s cytoskeleton | 23, 71, 72, 172, 191, 209-214 |

| Bradyzoite-Specific Proteins | Parasite persistence | 28, 85, 181, 215-220 |

| Cyst Wall/Sporozoite-specific (CST) Proteins | Cyst wall of the parasite’s tissue-cyst stage | 74, 149, 221 |

| Inner Membrane Complex (IMC) Proteins | Host cell invasion | 69, 191, 222, 223 |

| Metabolic Enzymes | Parasite’s survival and replication | |

| · Antioxidant Enzymes | Counteracting oxidative stress generated by the host’s immune response | 224-226 |

| · Energy Production and Glycolysis | Parasite energy production | 124, 152, 173, 227 |

| · Krebs Cycle | Generating energy and providing essential metabolites for the parasite’s survival and growth | 124, 228-230 |

| · Fatty Acid Metabolism | Breakdown, synthesis, and regulation of fatty acids within cells | 57, 231, 232 |

| · Gluconeogenesis | Synthesis of glucose from non-carbohydrate precursors | 66, 193, 233 |

| · Pentose Phosphate Pathway | Generates nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) | 234 |

| · Amino Acid Metabolism | Protein synthesis and various metabolic processes | 83, 235, 236 |

| · Phosphatases | Catalyze the removal of phosphate groups from target proteins, counteracting the actions of kinases | 201, 150, 216 |

| Synaptic Proteins | Influence host neuronal function and potentially modulate synaptic activity | 237, 238 |

| T. gondiiIntraNuclear Shuttle Protein (TgIST) | Facilitating the movement of certain proteins into and out of the nucleus | 239, 240 |

| Ca2+-responsive Proteins | Translating Ca2+ signals into specific cellular responses | 34, 39, 241, 242, 243, 88, 244 |

| Rhomboid Proteases | Release of extracellular domains from the membrane and impact various signaling pathways | 245, 246, 247 |

| Heat Shock Proteins (HSP) | Maintenance of survival, growth, and adaptation of T. gondii within its host environment | 61, 62, 187, 193, 248 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).