Submitted:

15 November 2023

Posted:

16 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Laser setup

2.3. Low-pressure plasma setup

2.4. Contact angle and surface free energy measurement

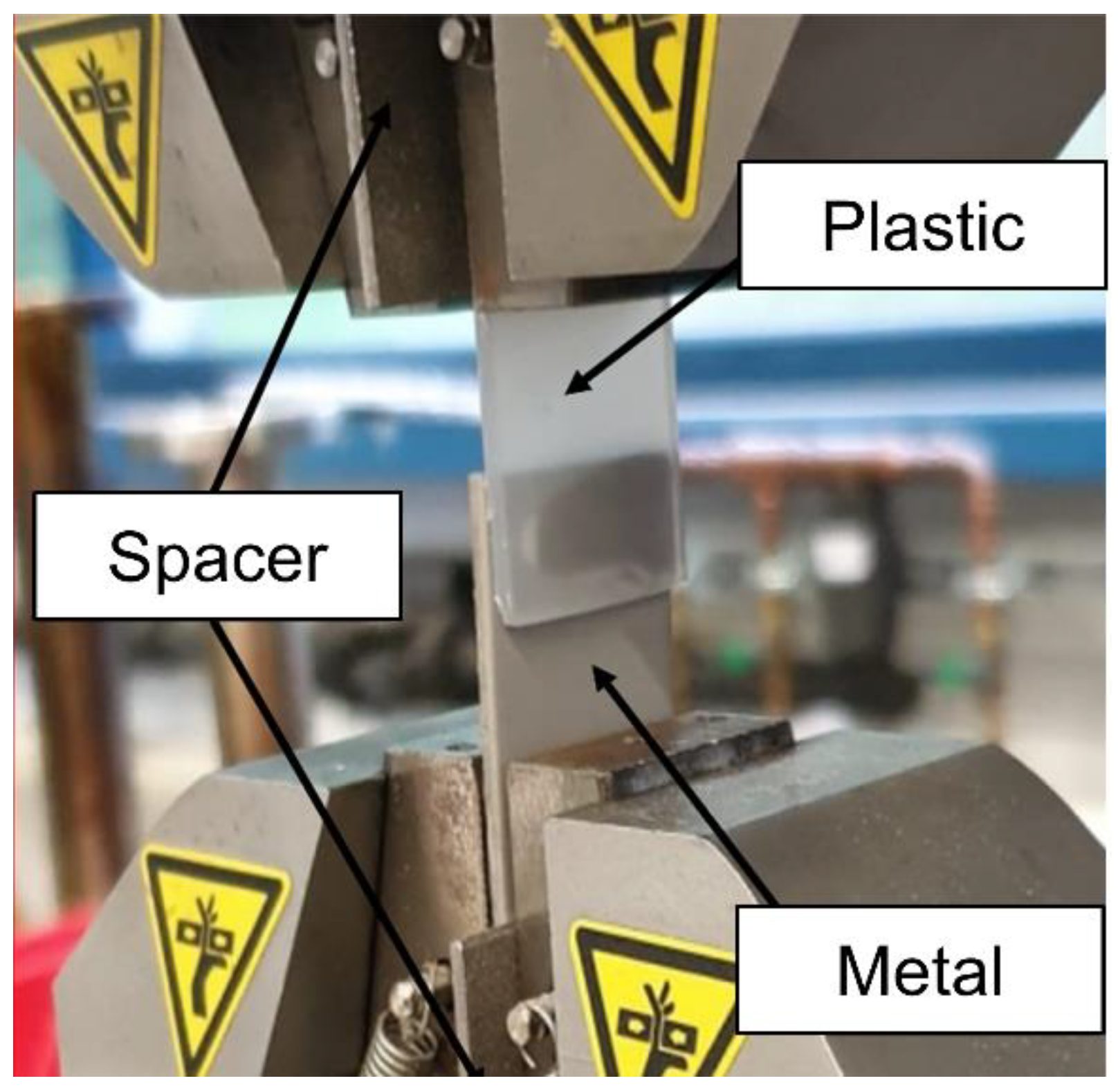

2.5. Mechanical testing and microstructural analysis

3. Results and Discussion

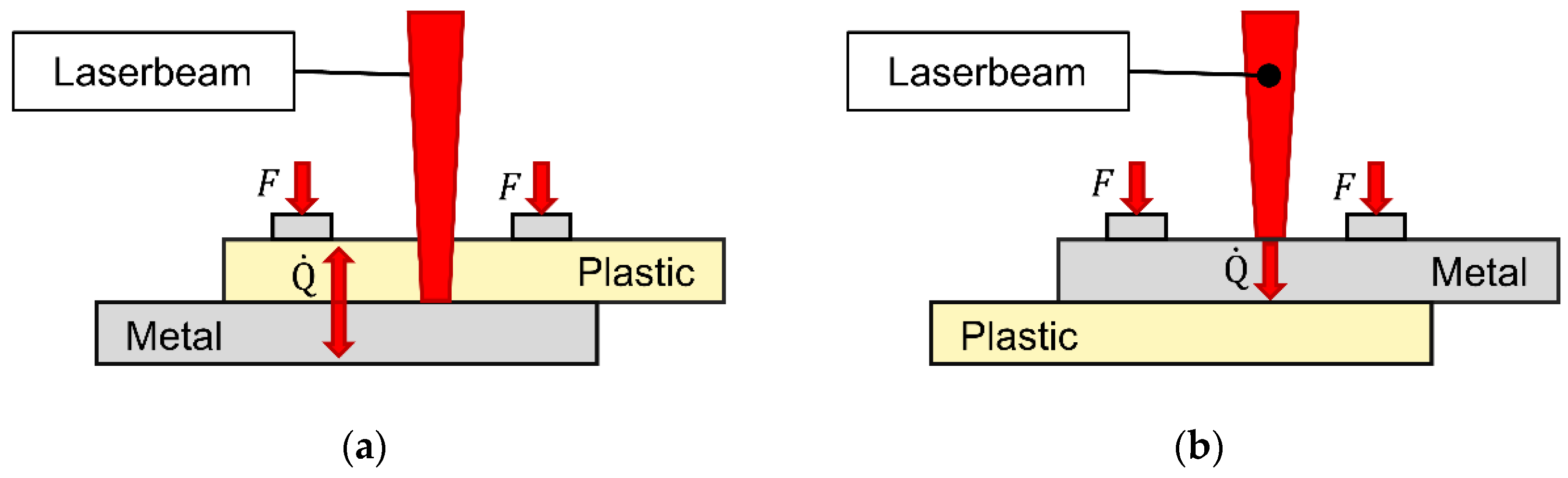

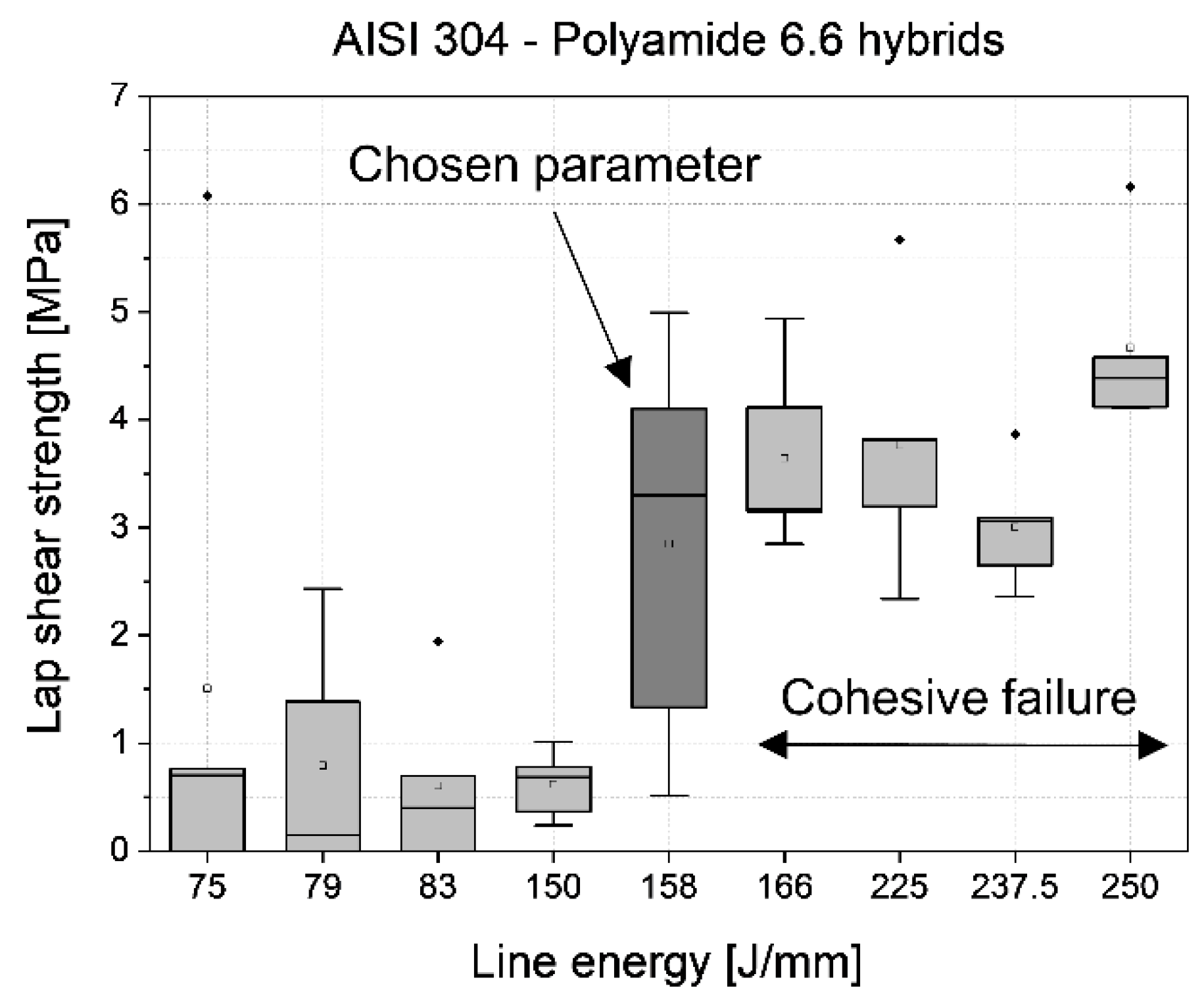

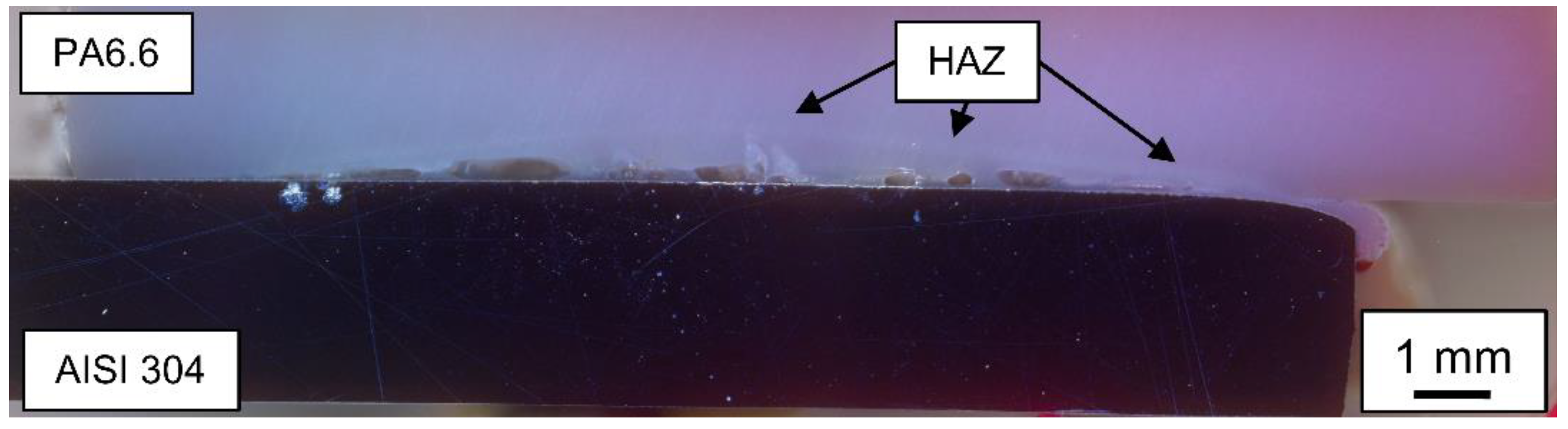

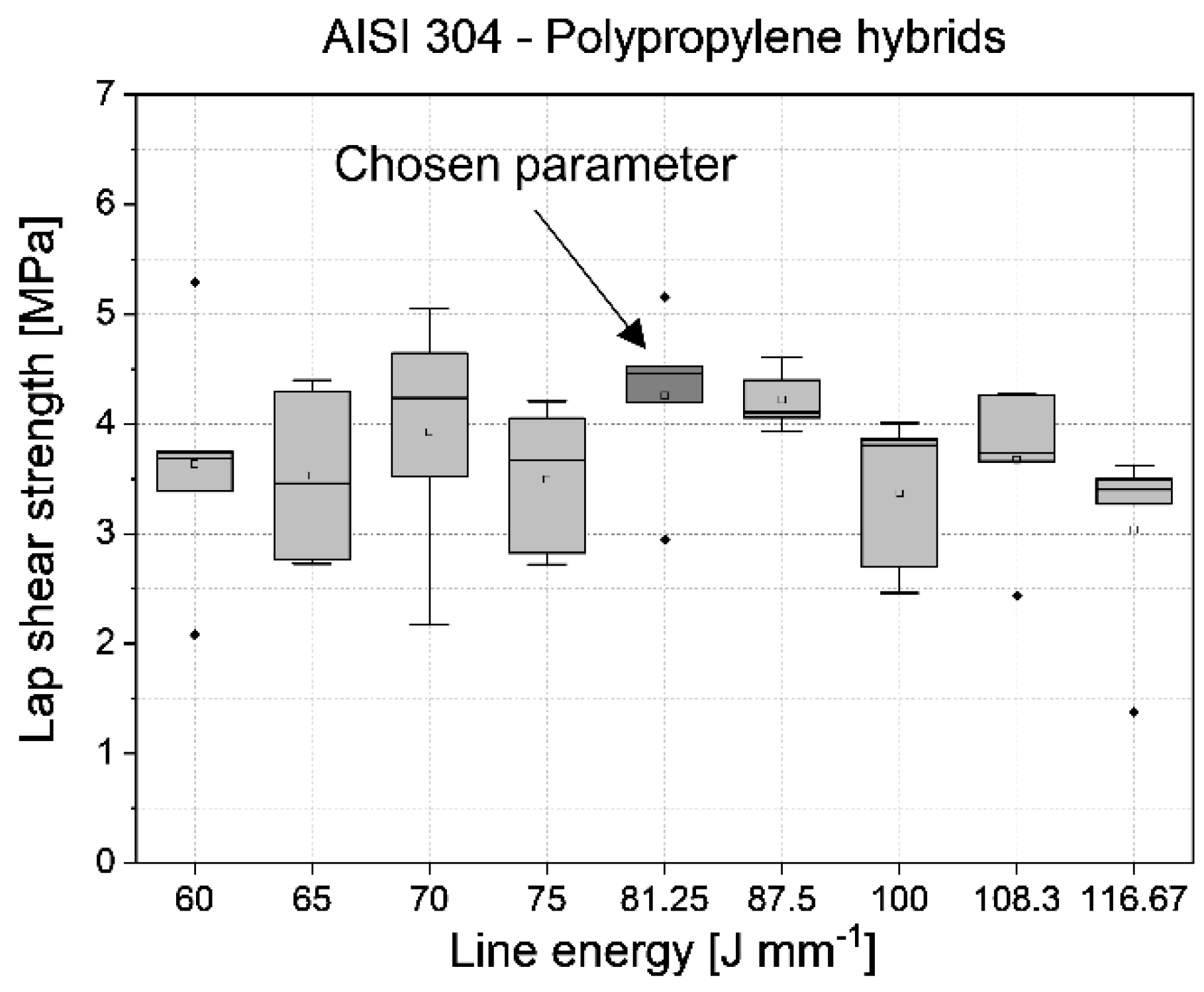

3.1. Identification of the joining parameters

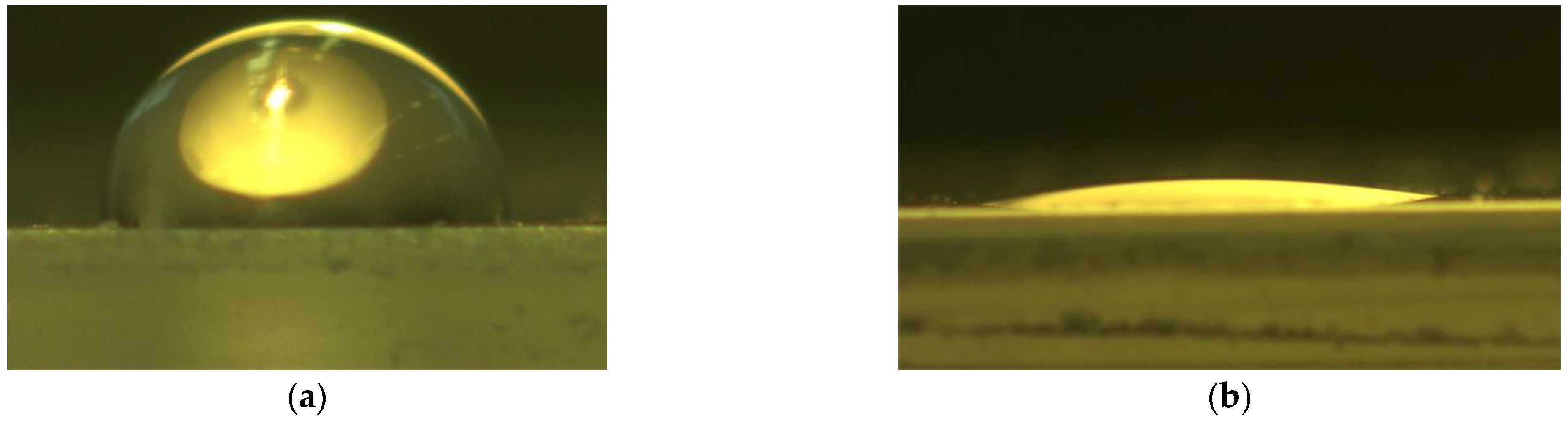

3.2. Surface free energy

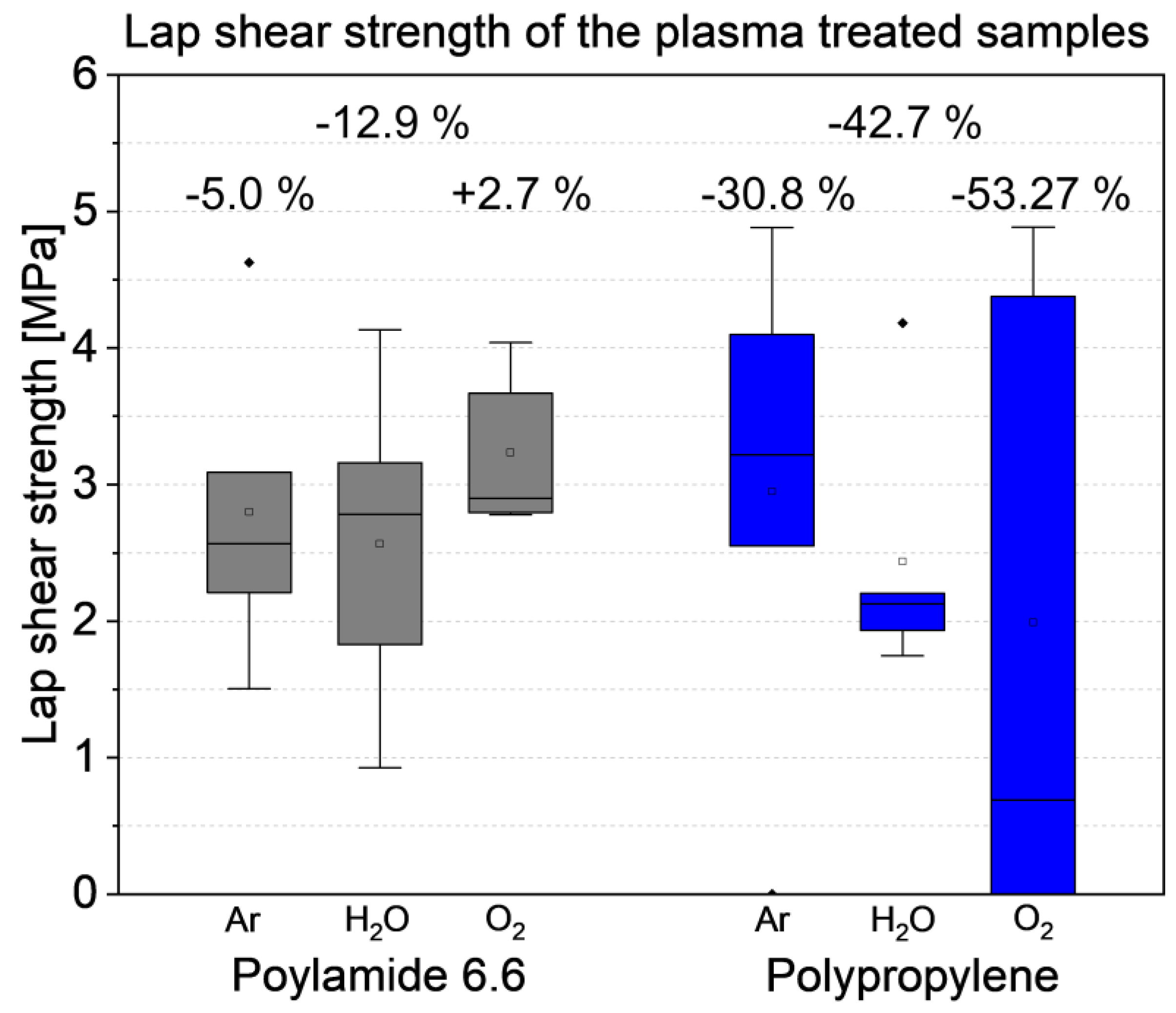

3.3. Influence of the plasma treatment on the lap shear strength

4. Conclusions

- I.

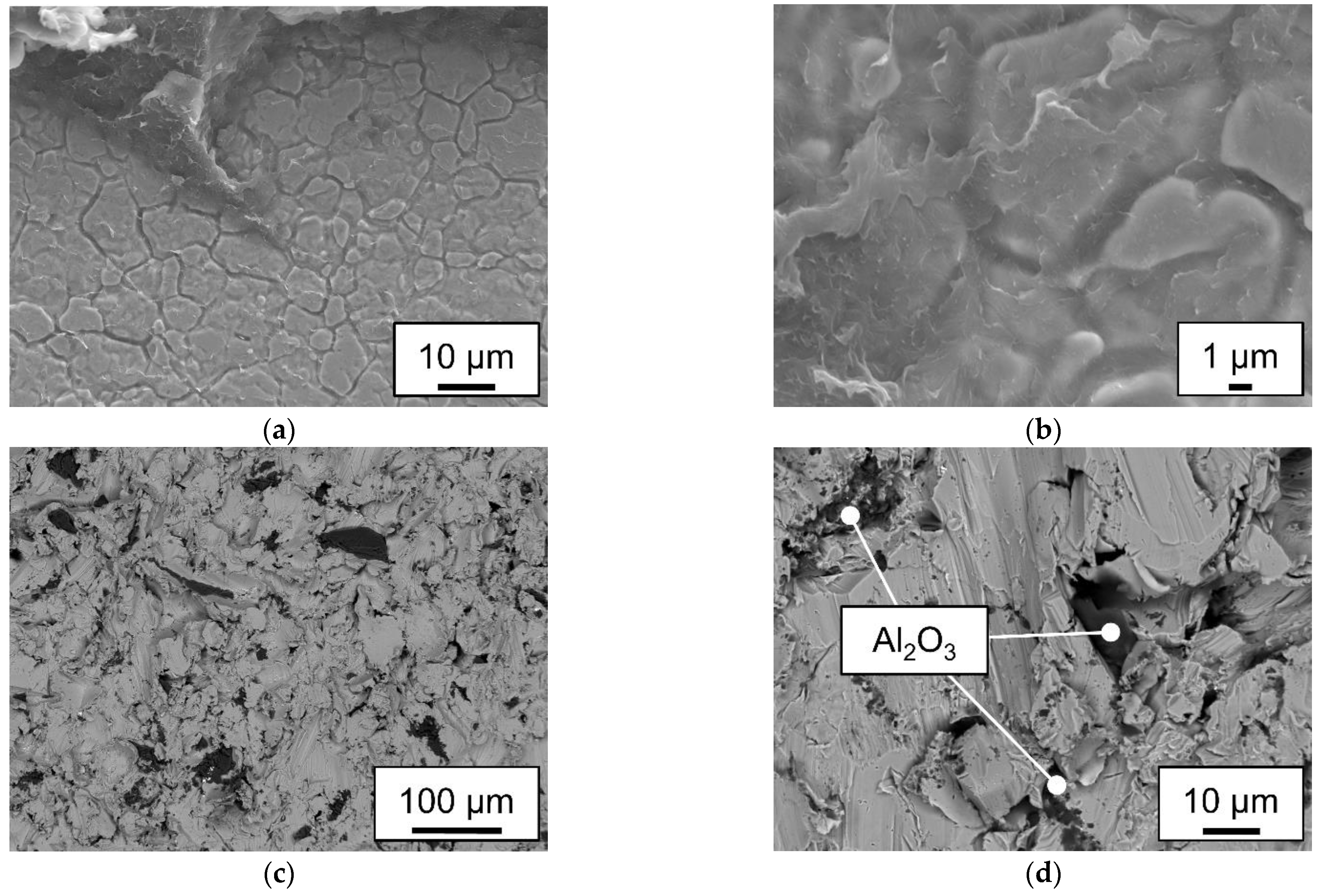

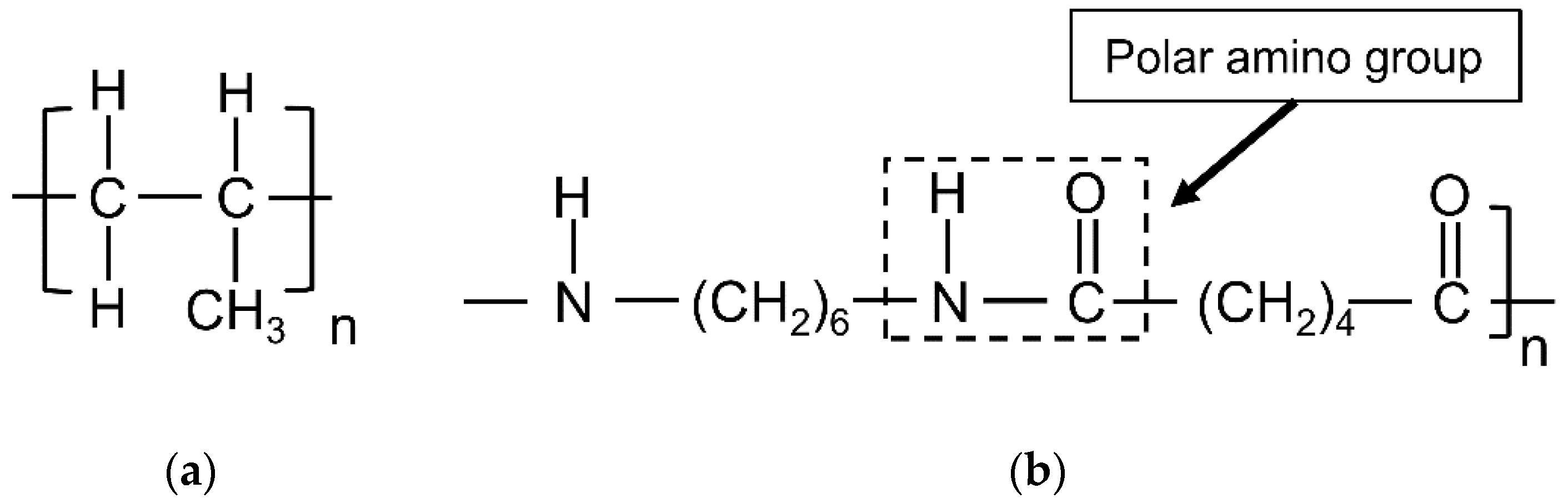

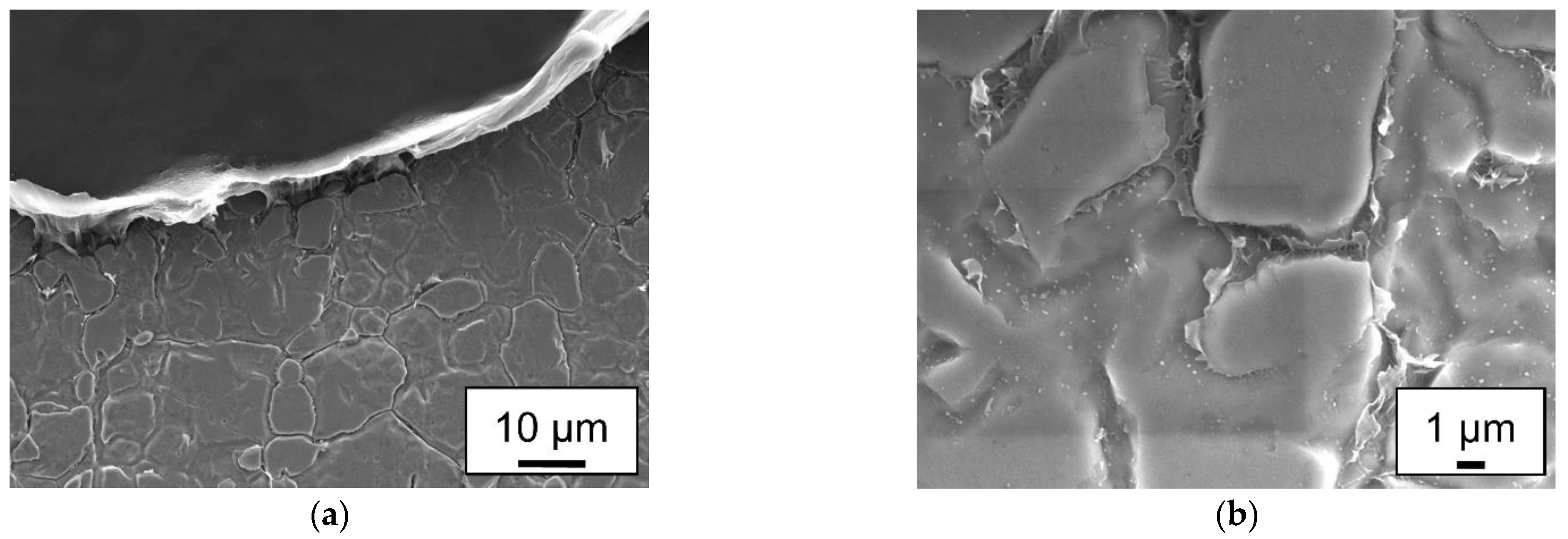

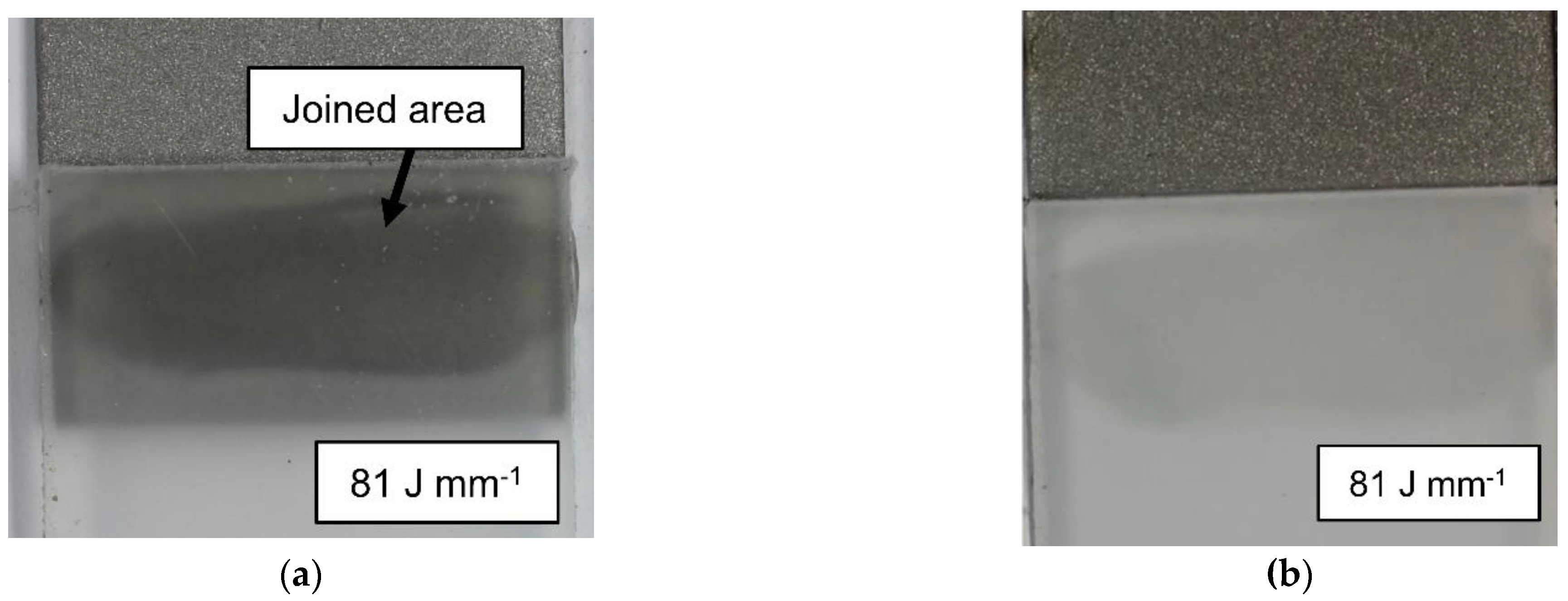

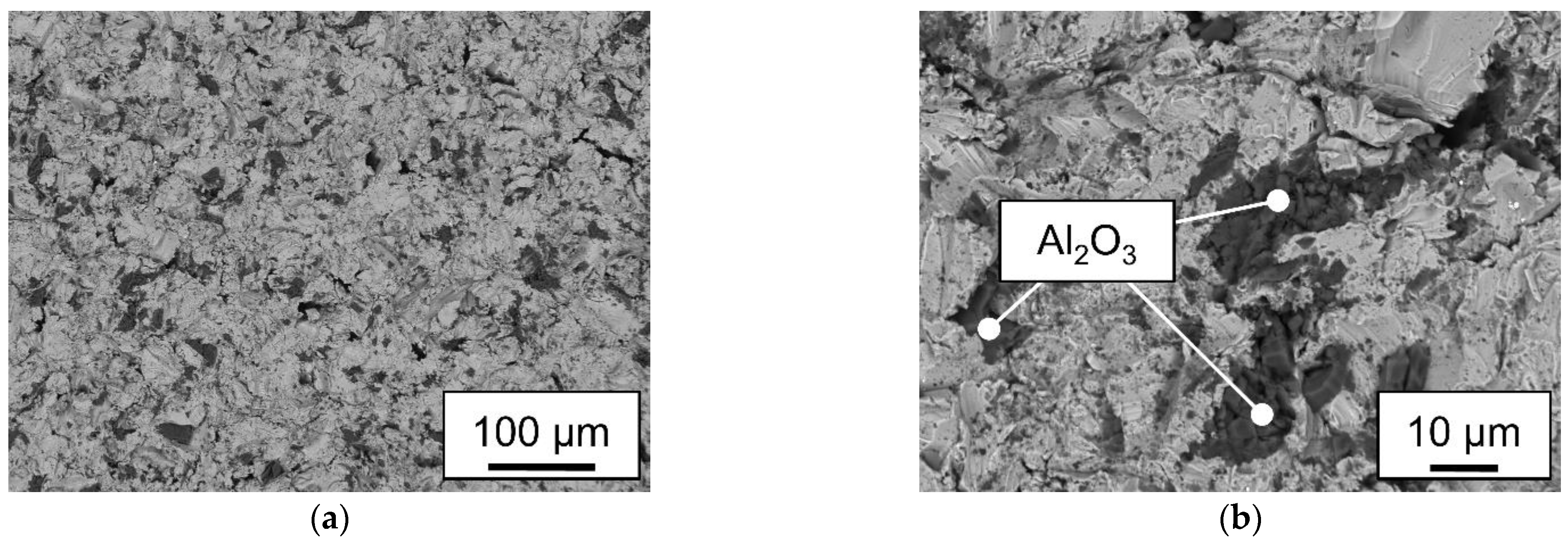

- Unpolar plastics like the used polypropylene needs sufficient mechanical adhesion when used within a laser joining process with metals. No plastic residue could be detected on the fractured surface.

- II

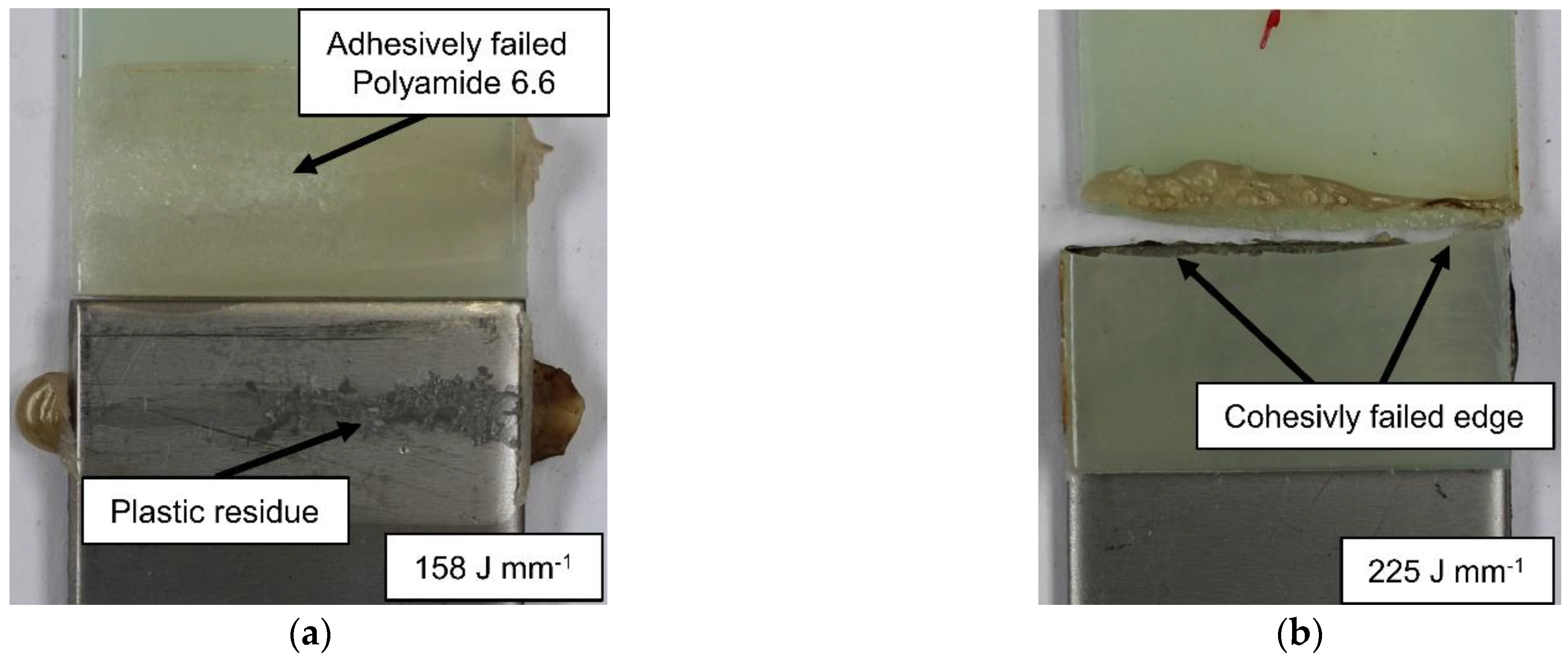

- Polyamide 6.6 hybrids can be joined without mechanical adhesion on smooth surfaces. The adhesively fractured samples leave residues on the steel surface. Higher line energies can cause cohesive failure of the plastic sample.

- III.

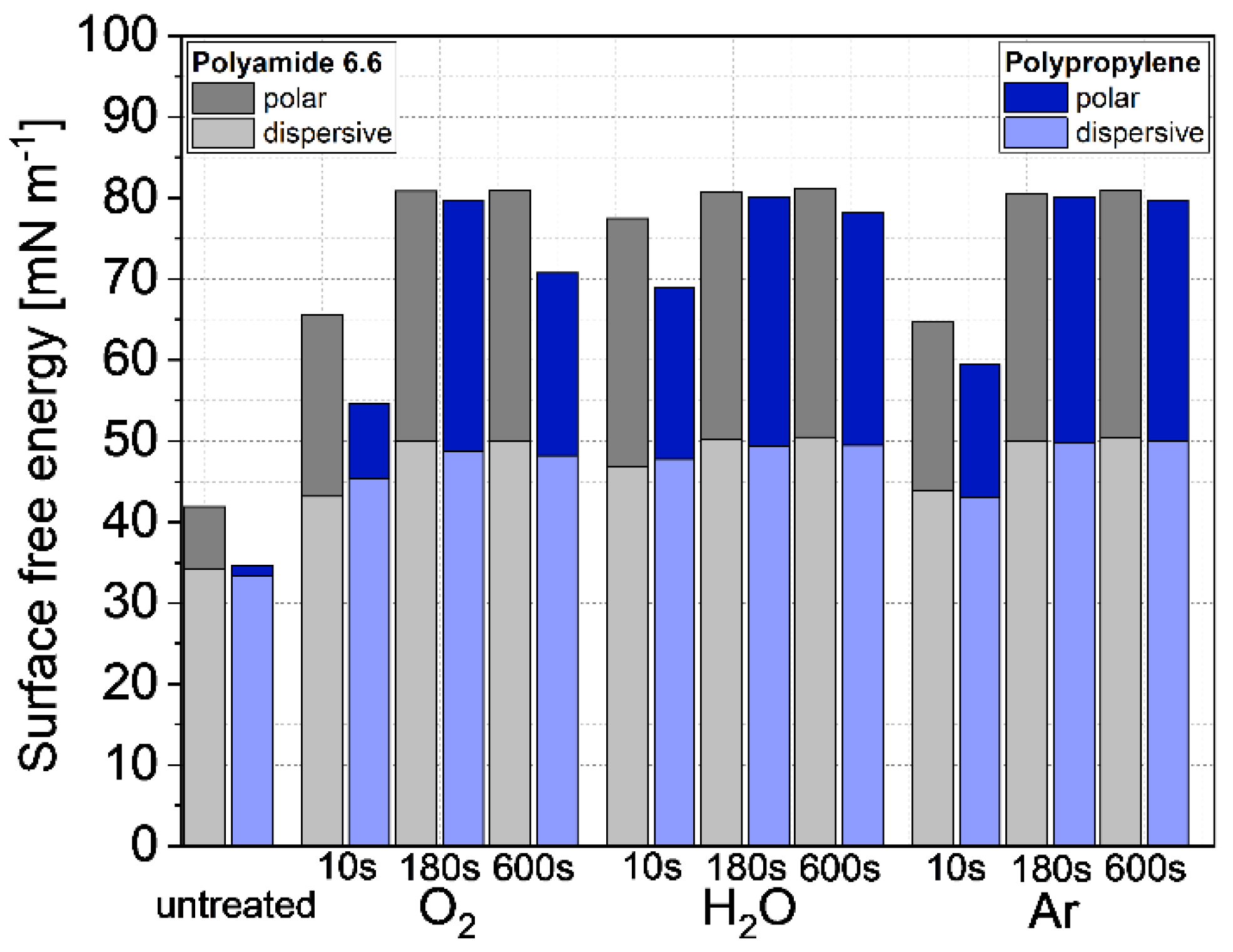

- Low-pressure plasma treatments with argon, oxygen and water as plasma gases increase the surface free energy significantly. The disperse and polar values calculated by the OWRK-Method were on the same level at 180 s treatment time.

- IV

- The low-pressure plasma treated polyamide 6.6 samples showed slightly varying lap shear strengths. The variation was in the range of the untreated samples. The drying effect of the low-pressure treatment increased the number of cohesively failed samples. This lead also to a more fractured appearance of the residue on the steel sample.

- V.

- The lap shear strength of the plasma treated polypropylene samples decreased significantly, especially within the oxygen plasma. This was attributed to overaging and the creation of Low Molecular Weight Oxidized Materials (LMWOM) on the surface.

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lambiase, F. Joinability of different thermoplastic polymers with aluminium AA6082 sheets by mechanical clinching. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2015, 80, 1995–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambiase, F. Mechanical behaviour of polymer–metal hybrid joints produced by clinching using different tools. Materials & Design 2015, 87, 606–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abibe, A.B.; Amancio-Filho, S.T.; dos Santos, J.F.; Hage, E. Mechanical and failure behaviour of hybrid polymer–metal staked joints. Materials & Design (1980-2015) 2013, 46, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feraboli, P.; Masini, A. Development of carbon/epoxy structural components for a high performance vehicle. Composites Part B: Engineering 2004, 35, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlin, E.; Heinonen, E.; Vuorinen, J.; Vippola, M.; Lepistö, T. Adhesion properties of novel corrosion resistant hybrid structures. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives 2014, 49, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, T.; Golewski, P.; Zarzeka-Raczkowska, E. Damage and failure processes of hybrid joints: Adhesive bonded aluminium plates reinforced by rivets. Computational Materials Science 2011, 50, 1256–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugauer, F.P.; Kandler, A.; Meyer, S.P.; Wunderling, C.; Zaeh, M.F. Induction-based joining of titanium with thermoplastics. Prod. Eng. Res. Devel. 2019, 13, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, R.-Y.; Hsu, R.-Q. Development of ultrasonic direct joining of thermoplastic to laser structured metal. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives 2016, 65, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenigaonaindia, A.; Liébana, F.; Lamikiz, A.; Echegoyen, Z. Novel Strategies for Laser Joining of Polyamide and AISI 304. Physics Procedia 2012, 39, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, J.P.; Stambke, M. Potential of Laser-manufactured Polymer-metal hybrid Joints. Physics Procedia 2012, 39, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, W.; Elrefaey, A.; Wojarski, L. Toward process optimization in laser welding of metal to polymer. Prozessoptimierung beim Laserstrahlschweißen von Metall mit Kunststoff. Mat.-wiss. u. Werkstofftech. 2010, 41, 879–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahito, Y.; Tange, A.; Kubota, S.; Katayama, S. Development of direct laser joining for metal and plastic. In International Congress on Applications of Lasers & Electro-Optics. ICALEO® 2006: 25th International Congress on Laser Materials Processing and Laser Microfabrication, Scottsdale, Arizona, USA, October 30–November 2, 2006; Laser Institute of America, 2006; p 604, ISBN 978-0-912035-85-7.

- Chen, Y.J.; Yue, T.M.; Guo, Z.N. A new laser joining technology for direct-bonding of metals and plastics. Materials & Design 2016, 110, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Liao, W.; Chen, C. Improving the interfacial bonding strength of dissimilar PA66 plastic and 304 stainless steel by oscillating laser beam. Optics & Laser Technology 2021, 138, 106869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schricker, K.; Samfaß, L.; Grätzel, M.; Ecke, G.; Bergmann, J.P. Bonding mechanisms in laser-assisted joining of metal-polymer composites. Journal of Advanced Joining Processes 2020, 1, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, S.; Kawahito, Y. Laser direct joining of metal and plastic. Scripta Materialia 2008, 59, 1247–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirchenhahn, P.; Al Sayyad, A.; Bardon, J.; Felten, A.; Plapper, P.; Houssiau, L. Highlighting Chemical Bonding between Nylon-6.6 and the Native Oxide from an Aluminum Sheet Assembled by Laser Welding. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2020, 2, 2517–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirchenhahn, P.; Al-Sayyad, A.; Bardon, J.; Plapper, P.; Houssiau, L. Binding Mechanisms Between Laser-Welded Polyamide-6.6 and Native Aluminum Oxide. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 33482–33497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Sayyad, A.; Bardon, J.; Hirchenhahn, P.; Mertz, G.; Haouari, C.; Laurent, H.; Plapper, P. Influence of laser ablation and plasma surface treatment on the joint strength of laser welded aluminum-polyamide assemblies 2017.

- Friedrich, J.; Friedrich, J.G. The plasma chemistry of polymer surfaces: Advanced techniques for surface design; Wiley-VCH-Verl.: Weinheim, 2012; ISBN 978-3-527-64803-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mandolfino, C. Polypropylene surface modification by low pressure plasma to increase adhesive bonding: Effect of process parameters. Surface and Coatings Technology 2019, 366, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaja, F.; Gilbert, M.; Kelly, G.; Fox, B.; Pigram, P.J. Adhesion of polymers. Progress in Polymer Science 2009, 34, 948–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, A.; Cuccolini, G.; Ascari, A.; Orazi, L.; Campana, G.; Tani, G. Hybrid metal-plastic joining by means of laser. Int J Mater Form 2010, 3, 1131–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polášková, K.; Klíma, M.; Jeníková, Z.; Blahová, L.; Zajíčková, L. Effect of Low Molecular Weight Oxidized Materials and Nitrogen Groups on Adhesive Joints of Polypropylene Treated by a Cold Atmospheric Plasma Jet. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Komuro, A.; Ono, R. Quantitative and selective study of the effect of O radicals on polypropylene surface treatment. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2023, 32, 75013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, E.; Osswald, T.A.; Rudolph, N. Saechtling Kunststoff Taschenbuch; 31. Ausgabe, [komplett überarb., aktualisiert und zum ersten Mal in Farbe]; Hanser: München, 2013; ISBN 978-3-446-43729-6. [Google Scholar]

- Scheik, S. Untersuchungen des Verbundverhaltens von thermisch direkt gefügten Metall-Kunststoffverbindungen unter veränderlichen Umgebungsbedingungen. Dissertation; Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule Aachen, Aachen, 2016.

| Surface | Rz [µm] |

|

|---|---|---|

| X | s | |

| Sand blasted | 14.69 | 1.72 |

| Cold-rolled | 1.44 | 0.35 |

| Plastic | Laser power [W] |

Scanning speed [mm/s] |

Line energy [J/mm] |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyamide 6.6 | 225, 237.5, 250 | 1, 1.5, 2 | 225 | 238 | 250 |

| 150 | 158 | 167 | |||

| 113 | 119 | 125 | |||

| Polypropylene | 150, 162.5, 175 | 1.5, 2, 2.5 | 100 | 108 | 117 |

| 75 | 81 | 88 | |||

| 60 | 65 | 70 | |||

| Liquid |

[mN m-1] |

[mN m-1] |

[mN m-1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 72.8 | 51 | 21.8 |

| Diiodomethane | 50.8 | 50.8 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).