Submitted:

14 November 2023

Posted:

15 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. General introduction

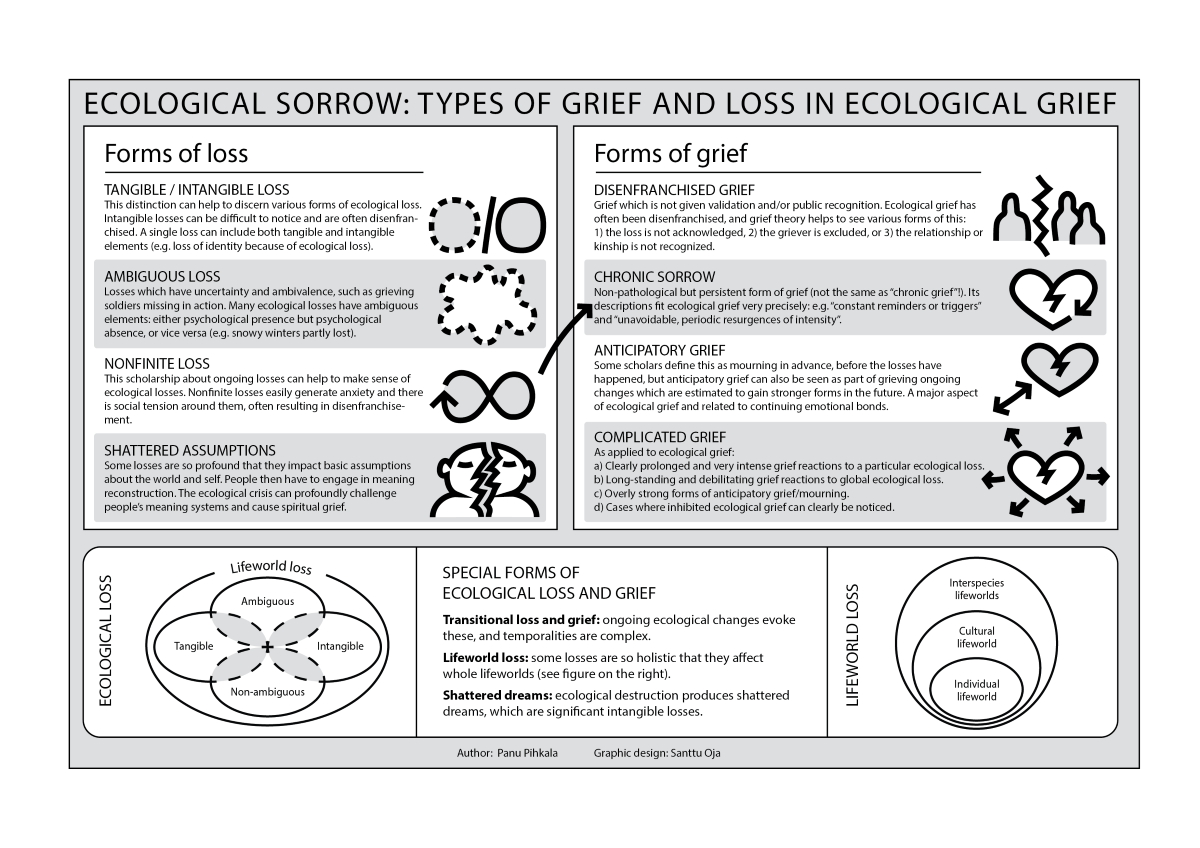

1.2. Forms of ecological grief and loss: building from earlier research

Rooted in losses that can begin in the deep past and extend into the deep future, it [ecological grief] exceeds the span of human seasons, lifetimes, epochs, and even species-being. And while the losses that prompt ecological grief can be actual losses in the present, these losses have a meaning beyond themselves: they are semaphores that point to planetary-scaled, often permanent losses in the future. [55], p.139

1.3. Theories of grief and bereavement

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sources

- Studies which use other formulations which include the word grief, such as “environmental grief” e.g. [1]. Environmental grief is an older term than ecological grief, but it did not spark as much interest among scholars then. Some often-cited articles and essays use the word grief or loss combined with other words, such as Windle’s “Ecology of grief” [20] or Randall’s “Loss and climate change” [47].

2.2. Method, research questions, and structure

- What frameworks and concepts of loss seem helpful for an increased understanding about ecological loss? (Section 3.1.)

- What frameworks and concepts of grief seem helpful for an increased understanding about various forms of ecological grief? (Section 3.2.)

- In the light of the analysis, what kind of new frameworks and concepts about ecological loss and grief could be useful? (Section 4.1.)

3. Types of ecological loss and forms of ecological grief

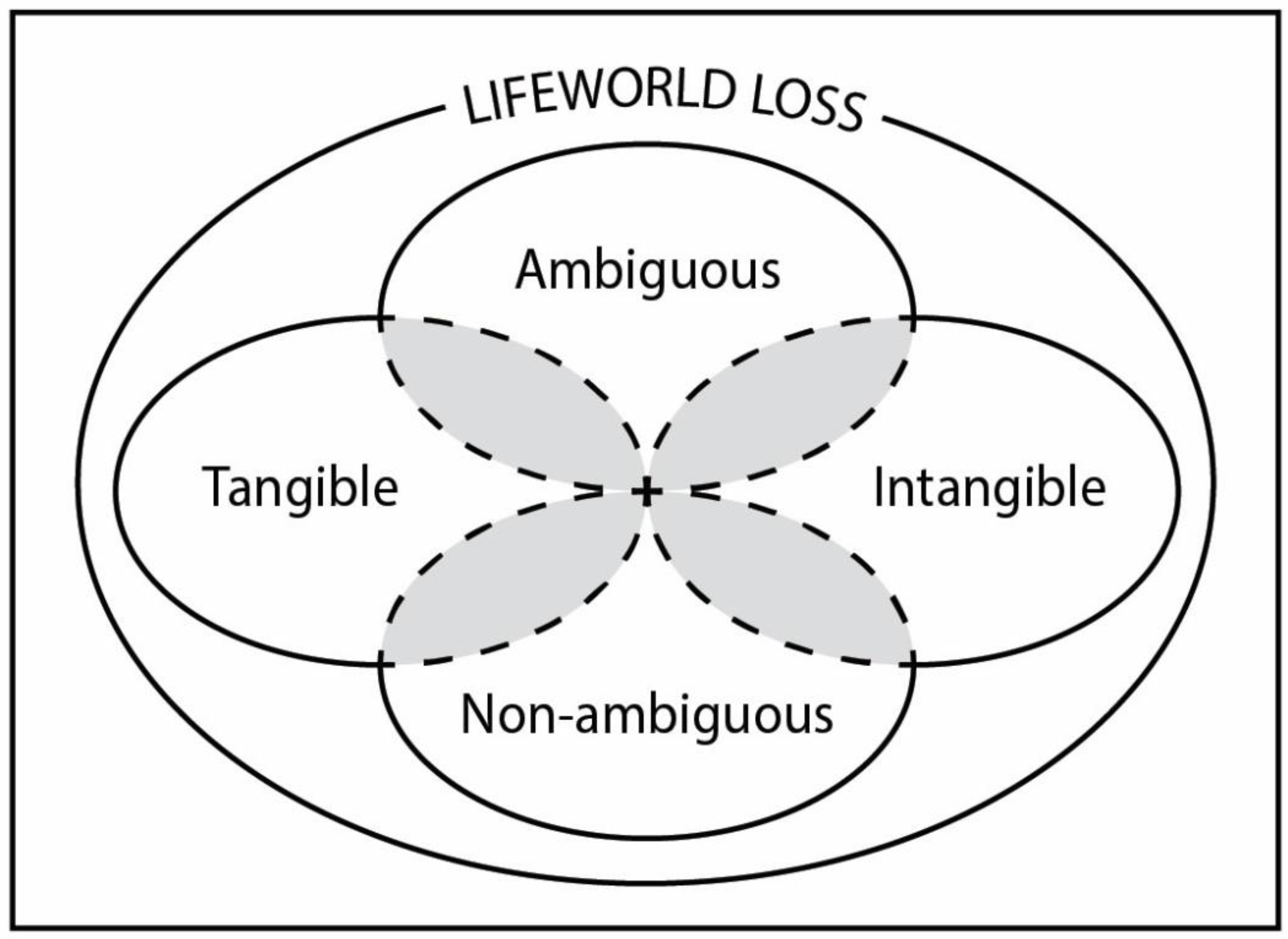

3.1. Types of ecological loss

3.1.1. Tangible and intangible loss

“When Ganga is no more,” she said, “we won’t have any identity”. [62], p. 27

- Loss or change in identity or sense of self

- Loss of connection to others

- Loss of social status

- Loss of meaning, faith or hope [88]

- Material loss

- Relationship loss

- Intrapsychic loss

- Functional loss

- Role loss

- Systematic loss [95]

| Source | Subject | Tangible and intangible aspects (examples) |

| Drew 2013 | Local people’s feelings about the perceived and feared changes in river Ganga, Indian Himalayas | Tangible: changes in river flowIntangible: loss of identity, because people identify with the river and the goddess that it manifests to them; fear of lifeworld loss (see section 4) and fear of spiritual loss |

| Brugger et al. 2013 | Local people’s feelings about glacier retreat in three regions around the world | Tangible: retreating glaciers; diminishing water supply; sometimes a secondary tangible loss of tourism incomeIntangible: aesthetic loss; for some, loss of local identity |

| Cunsolo et al. 2020 | Inuit feelings about declining numbers of caribou and related dynamics | Tangible: less caribou, restricted access to hunting them, loss of social practicesIntangible: many aspects, such as loss of identity, loss of relations, loss of shared experiences, role loss (e.g. hunter), loss of environmental knowledge |

| Amoak et al. 2023 | Climate change –induced grief among smallholder farmers in Ghana | Tangible: loss of local trees and changes in landscapes, social unrestIntangible: many aspects, such as loss of environmental knowledge; losses related to culture, identity, and traditions; role loss especially for men |

3.1.2. Ambiguous loss

Leah experienced solastalgia for predictable New England winters; her embodied, beyond words grief became more salient as autumn turned to winter and the predictable, sustained cold temperatures from her childhood had changed due to climate warming. [101], p. 6

3.1.3. Nonfinite loss

Ashlee Cunsolo Willox … has studied the impact of a changing climate on mental health Inuit communities in Labrador. Visible signs of climate change in the North from month to month or year to year make the repercussions inescapable for the people who live there, she says.

"People ... talk about experiencing strong emotional reactions: sadness and anger and frustration," she says. "It's a grief without end. Every day it's changing and there's a sense of loss." [111]

- “The loss (and grief) is continuous and ongoing in some way. While the initial event may be time-limited, an element of the experience will stay with the individual(s) for the rest of life.

- An inability to meet normal expectations of everyday life due to physical, cognitive, social, emotional, or spiritual losses that continue to be manifest over time.

- The inclusion of intangible losses, such as the loss of one’s hopes or ideals related to what a person should have been, could have been, or might have been.

- Awareness of the need to continually accommodate, adapt, and adjust to an experience that derails expectations of what life was supposed to be like. The term living losses is sometimes used to refer to nonfinite losses because of the awareness that an individual will live with this loss or some aspect of it for an indefinite period of time, and most likely for the rest of that individual’s life” [77],see also [114]

3.1.4. Shattered assumptions

“When I’m thinking about careers as well, I’m thinking, ‘Oh, well I’m going to find a job, but then the world’s kind of coming to an end’. I feel like that sounds really dramatic, but it does feel like, ‘What’s all this for?’ (Izzy)” [131], p. 480

“when you realize how serious, how far-reaching and how fast we need to act in the climate crisis … That’s an experience that shakes your entire foundation, in every possible way. It changes your entire view on the world in every aspect.” (young Swedish climate activist, [132], p. 27)

Significant life-changing events can cause us to feel deeply vulnerable and unsafe, because the world that we once knew, the people that we relied on, and the images and perceptions of ourselves may prove to be no longer relevant in light of what we have experienced. Grief is both adaptive and necessary in order to rebuild the assumptive world after its destruction. [66], p. 122

3.2. Forms of ecological grief

3.2.1. Disenfranchised grief and its varieties

… my friend Liz loved a certain forest in New Hampshire. … She was a teenager when a fierce storm blew into that forest, wiping out a large swath of trees. Liz was heartbroken. She had lost a friend, a spiritual presence, a guide. The next time her high school English teacher assigned the class an essay, she wrote about her love and grief for the forest. The teacher read the essay aloud to the class – not to praise it but to scorn it. When he finished reading, he chastised Liz for her sentimentality and her misguided notion that it was possible to love a mere thing like a forest. She was twice bereaved: once by the damage to her beloved forest and once by disrespect for her grief. [155], p. 19

Disenfranchising messages actively discount, dismiss, disapprove, discourage, invalidate, and delegitimate the experiences and efforts of grieving. And disenfranchising behaviors interfere with the exercise of the right to grieve by withholding permission, disallowing, constraining, hindering, and even prohibiting it. [164], p. 198

3.2.2. Chronic sorrow

Here is a well of grief we’re going to have to drop into over and over again for all our lives, no matter if we are eighty or eight: the wrecking power of climate change. [155], p. 13

3.2.3. Anticipatory grief and mourning

Leah wept about her children’s futures and the immensity of intensified suffering for all living beings. At times, the grief was in response to a present irretrievable loss and at other times, the mourning was about imagined future loss. [101], p. 6

“the phenomenon encompassing the processes of mourning, coping, interaction, planning, and psychosocial reorganization that are stimulated and begun in part in response to the awareness of the impending loss of a loved one and the recognition of associated losses in the past, present, and future” [196], p. 24

“Rather than liberating ourselves from the dead or disappeared, we can see grief as a way of sustaining connections with those whose loss we have survived. We can also see grief as an anticipatory stance, an orientation toward the vulnerability of the earth and our fellow travellers, that summons us to support and calls us to care.” [11], p. 23

This [ecological] grief is both acute and chronic, carried psychologically and emotionally, but is not linked to any one event or break moment, and develops over time, with knowledge of what could come based both on already-experienced changes (for example, declining sea ice in the North and on-going drought conditions in Australia) and projected changes. [2], p. 278

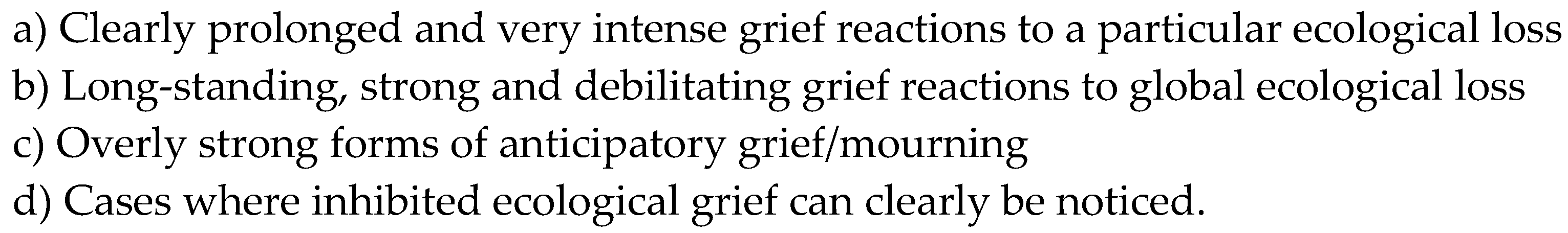

3.2.4. Complicated grief

The patient reported that preoccupation with climate change was impairing his ability to perform activities of daily living, and that he had been experiencing financial difficulties as he had stopped working secondary to this stressor. [220], p. 1

- Violent losses

- Losses which could have been prevented

- Sudden and powerful losses

- An ambivalent relationship with the subject of loss

- Personal or collective lack of grief skills and practices

4. Discussion

4.1. Special forms of ecological loss and grief

4.1.1. Transitional loss and grief

“You have people who for thousands of years have been connected to a cold and ice environment ... and suddenly in one generation, you're looking at ice-free winters and what that does to people, the utter devastation it causes.” [111]

“Over the course of my lifetime I’ve seen much of what I love just disappear . . . It just feels traumatic, I don’t know how to describe it. Because it just feels like grief and trauma.” [131], p. 478

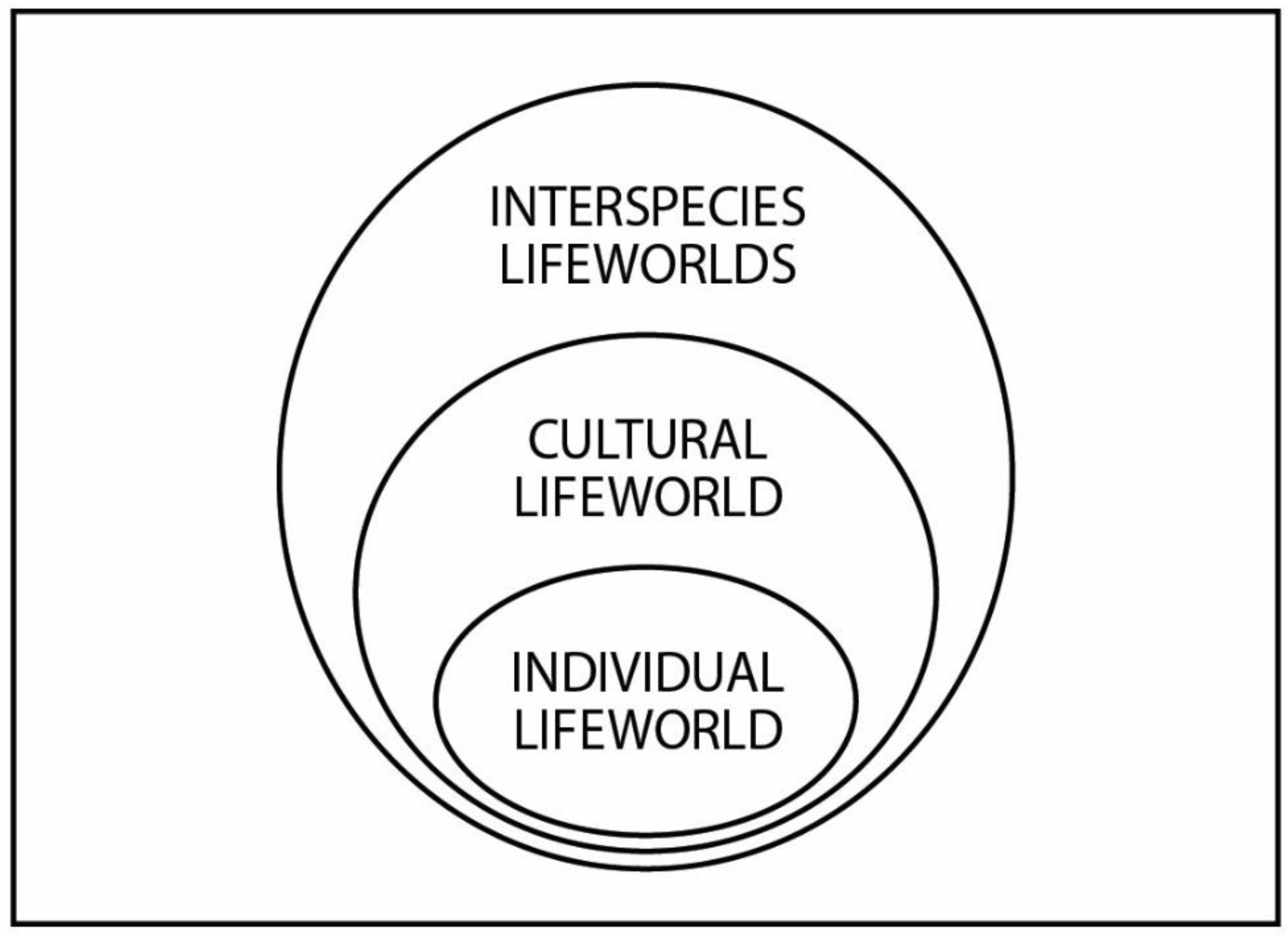

4.1.2. Lifeworld loss

“Losing the farm would be like a death. … we know this is where we’re meant to be, I think if you took us out of that it would be like [… ] It’s like making sense of a whole new map.” [2], p. 277

“I have become a weakling of no fault of mine. You plant, the crops die. You switch to maize; you can’t buy fertilizer. You can tell that your year is going to be bad even as you plant your crops. But what can I do? This is all I know… It’s a disgrace. You are not a man if you cannot provide for your family. I am not a man. It is just me and my alcohol now. (Male farmer, 40, Nakong [Ghana]) [80]

The self and the world must be relearned at profound levels that are central to the individual’s ability to function and navigate in the world. The process is often all-encompassing: redefining aspects of the world, others, and one’s self in ways that ripple across all aspects of daily life, including one’s hopes and dreams. [117], p. 294

A posthumanistic model suggests that the understanding and experience of mourning can become intrinsically ecological, moving from the disappearance of individual species or the impoverishment of the human life-world towards an ecology of mourning that is much more complex, inclusive, intersubjective, evocative of place, and deserving of research. [246], p. 128

4.1.3. Shattered dreams

“[Climate] [a]nxiety for me is when I’m sitting doing my schoolwork and feeling like it is useless because I might not have a future to work towards” [111]

4.2. Bringing types of loss and forms of grief together

4.3. Analyzing current ecological grief scholarship in the light of the results

4.3.1. Varieties of ecological grief (by Cunsolo & Ellis)

4.3.2. Questionnaires and research methods

4.4. Coping, counseling, and other themes for further research

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kevorkian, K.A. Environmental Grief: Hope and Healing, Union Institute & University: Cincinnati, 2004, Vol. Dissertation.

- Cunsolo, A.; Ellis, N.R. Ecological Grief as a Mental Health Response to Climate Change-Related Loss. Nature Climate Change 2018, 8, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, G.; Sartore, G.-M.; Connor, L.; Higginbotham, N.; Freeman, S.; Kelly, B.; Stain, H.; Tonna, A.; Pollard, G. Solastalgia: The Distress Caused by Environmental Change. Australasian psychiatry: Bulletin of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists 2007, 15, S95–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J.; Tschakert, P.; Head, L.; Adger, W.N. Commentary: A Science of Loss. Nature Climate Change 2016, 6, 976–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.H.; Miller, E.D. Toward a Psychology of Loss. Psychol Sci 1998, 9, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, A.; Borish, D.; Harper, S.L.; Snook, J.; Shiwak, I.; Wood, M. ; The Herd Caribou Project Steering Committee “You Can Never Replace the Caribou”: Inuit Experiences of Ecological Grief from Caribou Declines. American Imago 2020, 77, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, N.R.; Albrecht, G. Climate Change Threats to Family Farmers’ Sense of Place and Mental Wellbeing: A Case Study from the Western Australian Wheatbelt. Soc.Sci.Med. 2017, 175, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neckel, S.; Hasenfratz, M. Climate Emotions and Emotional Climates: The Emotional Map of Ecological Crises and the Blind Spots on Our Sociological Landscapes. Social Science Information 2021, 60, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hidalgo, M.; Zografos, C. Emotions, Power, and Environmental Conflict: Expanding the ‘Emotional Turn’ in Political Ecology. Progress in Human Geography 2020, 44, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boss, P. Understanding and Treating the Unresolved Grief of Ambiguous Loss: A Research-Based Theory to Guide Therapists and Counselors. In Non-Death Loss and Grief: Context and Clinical Implications; Harris, D.L., Ed.; Routledge: New York, 2020; pp. 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, J.T. Mourning in the Anthropocene: Ecological Grief and Earthly Coexistence; Michigan State University Press: East Lansing, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss & Grief; Cunsolo, A., Landman, K., Eds.; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal & Kingston, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, B.; Weir, J.; Cavanagh, V.I. Strength from Perpetual Grief: How Aboriginal People Experience the Bushfire Crisis. The Conversation 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Meloche, K. Mourning Landscapes and Homelands: Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Peoples’ Ecological Griefs. Canadian Mountain Network website 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Parham, J. Green Man Hopkins: Poetry and the Victorian Ecological Imagination; Editions Rodopi: Amsterdam, NLD, 2010; ISBN 978-90-420-3107-4. [Google Scholar]

- Leopold, A. A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There; Oxford University Press: New York, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Christie, D.E. The Blue Sapphire of the Mind: Notes for a Contemplative Ecology; Oxford University Press: New York, 2013; ISBN 978-0-19-981232-5. [Google Scholar]

- Macy, J. Despair and Personal Power in the Nuclear Age; Philadelphia: New Society Publishers, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Glendinning, C. My Name Is Chellis and I’m in Recovery from Western Civilization; New Catalyst Books: Gabriola Island, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Windle, P. The Ecology of Grief. In Ecopsychology: Restoring the earth, healing the mind; Roszak, T., Gomes, M.E., Kanner, A.D., Eds.; Sierra Club: San Francisco, 1995; pp. 126–145. [Google Scholar]

- Head, L. Hope and Grief in the Anthropocene: Re-Conceptualising Human–Nature Relations; Routledge research in the anthropocene; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: London, 2016; ISBN 9781315739335. [Google Scholar]

- Vulnerable Witness: The Politics of Grief in the Field, 1st ed.; Gillespie, K., Lopez, P.J., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, 2019; ISBN 978-0-520-29784-5. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, G. Earth Emotions: New Words for a New World; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, 2019; ISBN 978-1-5017-1522-8. [Google Scholar]

- Galway, L.P.; Beery, T.; Jones-Casey, K.; Tasala, K. Mapping the Solastalgia Literature: A Scoping Review Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo Willox, A. Climate Change as the Work of Mourning. Ethics & the Environment 2012, 17, 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Cunsolo Willox, A.; Harper, S.L.; Edge, V.L.; Landman, K.; Houle, K.; Ford, J.D. ; the Rigolet Inuit Community Government ‘The Land Enriches the Soul:’ On Climatic and Environmental Change, Affect, and Emotional Health and Well-Being in Rigolet, Nunatsiavut, Canada. Emotion, Space and Society 2013, 6, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, J.; Cunsolo, A.; Jones-Bitton, A.; Wright, C.J.; Harper, S.L. Indigenous Mental Health in a Changing Climate: A Systematic Scoping Review of the Global Literature. Environmental Research Letters 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, A.; Harper, S.L.; Minor, K.; Hayes, K.; Williams, K.G.; Howard, C. Ecological Grief and Anxiety: The Start of a Healthy Response to Climate Change? The Lancet.Planetary health 2020, 4, e261–e263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M.; Cunsolo, A.; Ogunbode, C.A.; Middleton, J. Anxiety, Worry, and Grief in a Time of Environmental and Climate Crisis: A Narrative Review. Annual review of environment and resources 2021, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Anxiety and the Ecological Crisis: An Analysis of Eco-Anxiety and Climate Anxiety. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landmann, H. Emotions in the Context of Environmental Protection: Theoretical Considerations Concerning Emotion Types, Eliciting Processes, and Affect Generalization. Umweltpsychologie 2020, 24, 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, P. Toward a Taxonomy of Climate Emotions. Frontiers in Climate 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, G. Emotional Reactions to Environmental Risks: Consequentialist versus Ethical Evaluation. J.Environ.Psychol. 2003, 23, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higginbotham, N.; Connor, L.; Albrecht, G.; Freeman, S.; Agho, K. Validation of an Environmental Distress Scale. EcoHealth 2006, 3, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ágoston, C.; Urbán, R.; Nagy, B.; Csaba, B.; Kőváry, Z.; Kovács, K.; Varga, A.; Dúll, A.; Mónus, F.; Shaw, C.A.; et al. The Psychological Consequences of the Ecological Crisis: Three New Questionnaires to Assess Eco-Anxiety, Eco-Guilt, and Ecological Grief. Climate risk management 2022, 37, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczak, M.; Wierzba, M.; Zaremba, D.; Kulesza, M.; Szczypiński, J.; Kossowski, B.; Budziszewska, M.; Michałowski, J.; Klöckner, C.A.; Marchewka, A. Beyond Climate Anxiety: Development and Validation of the Inventory of Climate Emotions (ICE): A Measure of Multiple Emotions Experienced in Relation to Climate Change. Global Environmental Change 2023, 83, article–102764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, C.; Leiva-Bianchi, M.; Serrano, C.; Ormazábal, Y.; Mena, C.; Cantillana, J.C. What Is Solastalgia and How Is It Measured? SOS, a Validated Scale in Population Exposed to Drought and Forest Fires. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 13682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Death, Dying, and Bereavement: Contemporary Perspectives, Institutions, and Practices; Attig, T., Stillion, J.M., Eds.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, 2015; ISBN 0826171427. [Google Scholar]

- Non-Death Loss and Grief: Context and Clinical Implications; Harris, D.L., Ed.; Routledge: New York, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe, M.; Richardson, L. Grief over Non-Death Losses: A Phenomenological Perspective. Passion 2023, 1, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, R.C. On Grief and Gratitude. In Defense of Sentimentality; Solomon, R.C., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2004; pp. 75–107. ISBN 978-0-19-514550-2. [Google Scholar]

- Simos, B.G. A Time to Grieve: Loss as a Universal Human Experience; Family Service Association of America: New York, 1979; ISBN 0-87304-153-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tait, D. Planet Grief: Redefining Grief for the Real World; Flint: Cheltenham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, A.V.; Wakefield, J.C. The Loss of Sadness : How Psychiatry Transformed Normal Sorrow into Depressive Disorder; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2007; ISBN 0-19-804269-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G.A.; Wortman, C.B.; Lehman, D.R.; Tweed, R.G.; Haring, M.; Sonnega, J.; Carr, D.; Nesse, R.M. Resilience to Loss and Chronic Grief: A Prospective Study From Preloss to 18-Months Postloss. Journal of personality and social psychology 2002, 83, 1150–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzen, M.K. “A Grief More Deep than Me” - on Ecological Grief. In Cultural, existential and phenomenological dimensions of grief experience; Køster, A., Kofod, E.H., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon; New York, 2022; pp. 214–228. ISBN 978-0-367-56811-5. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, R. Loss and Climate Change: The Cost of Parallel Narratives. Ecopsychology 2009, 1, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comtesse, H.; Ertl, V.; Hengst, S.M.C.; Rosner, R.; Smid, G.E. Ecological Grief as a Response to Environmental Change: A Mental Health Risk or Functional Response? International journal of environmental research and public health 2021, 18, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; Halstead, F.; Parsons, K.J.; Le, H.; Bui, L.T.H.; Hackney, C.R.; Parson, D.R. 2020-Vision: Understanding Climate (in)Action through the Emotional Lens of Loss. Journal of the British Academy 2021, 9s5, 29–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence; Verso: London, 2003; ISBN 1-84467-005-8. [Google Scholar]

- Cultural, Existential and Phenomenological Dimensions of Grief Experience; Køster, A., Kofod, E.H., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon; New York, 2022; ISBN 978-0-367-56811-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe, M. Grief Worlds: A Study of Emotional Experience; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA & London, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, S. Creating Aesthetic Encounters of the World, or Teaching in the Presence of Climate Sorrow. Journal of Philosophy of Education 2020, 54, 1110–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbach, S. Climate Sorrow. In This is not a drill: an Extinction Rebellion handbook; Penguin Books: London, 2020; pp. 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Amour, P., K. There Is Grief of a Tree. American imago 2020, 77, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardell, S. Naming and Framing Ecological Distress. Medicine Anthropology Theory 2020, 7, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newby, J. Beyond Climate Grief: A Journey of Love, Snow, Fire, and an Enchanted Beer Can; NewSoundBooks: Sydney, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, P. The Process of Eco-Anxiety and Ecological Grief: A Narrative Review and a New Proposal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, C.; Pihkala, P. Eco-Anxiety: What It Is and Why It Matters. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangervo, J.; Jylhä, K.M.; Pihkala, P. Climate Anxiety: Conceptual Considerations, and Connections with Climate Hope and Action. Global Environmental Change 2022, 76, 102569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, T.; Lykins, A.; Piotrowski, N.A.; Rogers, Z.; Sebree, D.D.; White, K.E. Clinical Psychology Responses to the Climate Crisis. In Reference Module in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology; Elsevier, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Drew, G. Why Wouldn’t We Cry? Love and Loss along a River in Decline. Emotion, space and society 2013, 6, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaremba, D.; Kulesza, M.; Herman, A.M.; Marczak, M.; Kossowski, B.; Budziszewska, M.; Michałowski, J.M.; Klöckner, C.A.; Marchewka, A.; Wierzba, M. A Wise Person Plants a Tree a Day before the End of the World: Coping with the Emotional Experience of Climate Change in Poland. Curr Psychol 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, N.; Adger, W.N.; Benham, C.; Brown, K.; Curnock, M.I.; Gurney, G.G.; Marshall, P.; Pert, P.L.; Thiault, L. Reef Grief: Investigating the Relationship between Place Meanings and Place Change on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Sustain Sci 2019, 14, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooyman, N.R.; Kramer, B.J. Living through Loss: Interventions across the Life Span; Foundations of social work knowledge; Columbia University Press: New York, 2008; ISBN 0-231-51072-1. [Google Scholar]

- Winokuer, H.R.; Harris, D. Principles and Practice of Grief Counseling; Third Edition.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, 2019; ISBN 0-8261-7184-2. [Google Scholar]

- Grief and Bereavement in Contemporary Society: Bridging Research and Practice; Neimeyer, R.A., Harris, D.L., Winokuer, H.R., Thornton, G., Eds.; Series in death, dying, and bereavement; Routledge: New York, 2011; ISBN 978-0-203-84086-3. [Google Scholar]

- Worden, J.W. Grief Counseling and Grief Therapy: A Handbook for the Mental Health Practitioner; 5th ed.; Springer: New York, 2018; ISBN 978-0-8261-3474-5. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, C.M.; Prigerson, H.G. Bereavement: Studies of Grief in Adult Life, 4th ed.; Routledge, 2013; ISBN 0-415-45118-3. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe, M.; Schut, H. Bereavement in Times of COVID-19: A Review and Theoretical Framework. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying 2021, 82, 500–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Continuing Bonds: New Understandings of Grief; Silverman, P.R., Nickman, S.L., Klass, D., Eds.; Series in death education, aging, and health care; Taylor & Francis: Washington, DC, 1996; ISBN 978-1-56032-336-5. [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer, R.A. Meaning Reconstruction in Bereavement: Development of a Research Program. Death studies 2019, 43, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. Bereavement Theory: Recent Developments in Our Understanding of Grief and Bereavement. Bereavement Care 2014, 33, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root, B.L.; Exline, J.J. The Role of Continuing Bonds in Coping With Grief: Overview and Future Directions. Death studies 2014, 38, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, C.A.; McCoyd, J.L.M. Grief and Loss across the Lifespan: A Biopsychosocial Perspective; Second edition.; Springer Publishing Company, LLC: New York, NY, 2016; ISBN 0-8261-2029-6. [Google Scholar]

- Counting Our Losses: Reflecting on Change, Loss, and Transition in Everyday Life; Harris, D.L., Ed.; Series in Death, Dying, and Bereavement; Taylor and Francis, 2011; ISBN 0-415-87529-3. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, C.L.; Harris, D.L. Giving Voice to Nonfinite Loss and Grief in Bereavement. In Grief and bereavement in contemporary society: Bridging research and practice; Neimeyer, R.A., Harris, D.L., Winokuer, H.R., Thornton, G., Eds.; Series in death, dying, and bereavement; Routledge: New York, 2011; pp. 235–245. ISBN 978-0-203-84086-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kevorkian, K.A. Environmental Grief. In Non-Death Loss and Grief: Context and Clinical Implications; Harris, D.L., Ed.; Routledge: New York, 2020; pp. 216–226. [Google Scholar]

- Boss, P. The Myth of Closure: Ambiguous Loss in a Time of Pandemic and Change; First edition.; W.W. Norton & Company New York, NY: New York, NY, 2022; ISBN 978-1-324-01681-6. [Google Scholar]

- Amoak, D.; Kwao, B.; Ishola, T.O.; Mohammed, K. Climate Change Induced Ecological Grief among Smallholder Farmers in Semi-Arid Ghana. SN Soc Sci 2023, 3, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Bray, M.; Wutich, A.; Larson, K.L.; White, D.D.; Brewis, A. Anger and Sadness: Gendered Emotional Responses to Climate Threats in Four Island Nations. Cross-Cultural Research 2019, 53, 58–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askland, H.H.; Bunn, M. Lived Experiences of Environmental Change: Solastalgia, Power and Place. Emotion, Space and Society 2018, 27, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugger, J.; Dunbar, K.W.; Jurt, C.; Orlove, B. Climates of Anxiety: Comparing Experience of Glacier Retreat across Three Mountain Regions. Emotion, Space and Society 2013, 6, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, B. Generation Dread: Finding Purpose in an Age of Climate Crisis; Alfred A. Knopf: Toronto, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, J.A. Climate Cure: Heal Yourself to Heal the Planet; Llewellyn Publications: Woodbury, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, S. Climate Crisis and Consciousness: Re-Imagining Our World and Ourselves; Routledge: London & New York, 2020; ISBN 0-367-36534-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sherrell, D. Warmth: Coming of Age at the End of the World; Penguin Books: New York, 2021; ISBN 978-0-14-313653-8. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, D.L. Tangible and Intangible Losses. In Non-Death Loss and Grief: Context and Clinical Implications; Harris, D.L., Ed.; Routledge: New York, 2020; pp. 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider-Mayerson, M.; Leong, K.L. Eco-Reproductive Concerns in the Age of Climate Change. Clim.Change 2020, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rando, T.A. Grieving: How to Go on Living When Someone You Love Dies; Lexington Books: Lexington, Mass, 1995; ISBN 978-0-669-17021-4. [Google Scholar]

- Gatchel, R.J.; Adams, L.; Polatin, P.B.; Kishino, N.D. Secondary Loss and Pain-Associated Disability: Theoretical Overview and Treatment Implications. Journal of occupational rehabilitation 2002, 12, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, L. Climate Change and Youth: Turning Grief and Anxiety into Activism; Routledge: New York & London, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tschakert, P.; Barnett, J.; Ellis, N.; Lawrence, C.; Tuana, N.; New, M.; Elrick-Barr, C.; Pandit, R.; Pannell, D. Climate Change and Loss, as If People Mattered: Values, Places, and Experiences. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews.Climate change 2017, 8, e476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschakert, P.; Ellis, N.R.; Anderson, C.; Kelly, A.; Obeng, J. One Thousand Ways to Experience Loss: A Systematic Analysis of Climate-Related Intangible Harm from around the World. Global Environ.Change 2019, 55, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.R.; Anderson, H. All Our Losses, All Our Griefs : Resources for Pastoral Care; 1st ed.; Westminster Press: Philadelphia, 1983; ISBN 978-0-664-24493-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kretz, L. Emotional Solidarity: Ecological Emotional Outlaws Mourning Environmental Loss and Empowering Positive Change. In Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss & Grief; Cunsolo Willox, A., Landman, K., Eds.; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal & Kingston, 2017; pp. 258–291. [Google Scholar]

- McKibben, B. Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet; St. Martin’s Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- DeMello, M. Mourning Animals: Rituals and Practices Surrounding Animal Death; Michigan State University Press: East Lansing, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, S.F. Mourning Ourselves and/as Our Relatives: Environment as Kinship. In Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss & Grief; Cunsolo Willox, A., Landman, K., Eds.; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal & Kingston, 2017; pp. 64–91. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, H.; Waite, T.D.; Dear, K.B.G.; Capon, A.G.; Murray, V. The Case for Systems Thinking about Climate Change and Mental Health. Nature Climate Change 2018, 8, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbott, M. Pretraumatic Climate Stress in Psychotherapy: An Integrated Case Illustration. Ecopsychology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boss, P. Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live With Unresolved Grief; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Boss, P.; Roos, S.; Harris, D. Grief in the Midst of Ambiguity and Uncertainty: An Exploration of Ambiguous Loss and Chronic Sorrow. In Grief and bereavement in contemporary society: Bridging research and practice; Neimeyer, R.A., Harris, D.L., Winokuer, H.R., Thornton, G., Eds.; Series in death, dying, and bereavement; Routledge:: New York, 2011; pp. 163–175. ISBN 978-0-203-84086-3. [Google Scholar]

- Boss, P. The Trauma and Complicated Grief of Ambiguous Loss. Pastoral Psychol 2010, 59, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, B. Mourning the Loss of Wild Soundscapes: A Rationale for Context When Experiencing Natural Sound. In Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss and Grief; Cunsolo Willox, A., Landman, K., Eds.; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal & Kingston, 2017; pp. 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Maddrell, A. Living with the Deceased: Absence, Presence and Absence-Presence. Cultural Geographies 2013, 20, 501–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, T. Presence in Absence: The Ambiguous Phenomenology of Grief. Phenom Cogn Sci 2018, 17, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steingraber, S. Raising Elijah: Protecting Our Children in an Age of Environmental Crisis; Da Capo Press: Boston, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, P. Climate Grief: How We Mourn a Changing Planet. BBC Website, Climate Emotions series 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer, K. The Snowy Countries Losing Their Identity. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20210215-winter-grief-how-warm-winters-threaten-snowy-cultures (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- McKie, D.; Keogh, D.; Buckley, C.; Cribb, R. Across North America, Climate Change Is Disrupting a Generation’s Mental Health. The National Observer 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, E.J.; Schultz, C.L. Nonfinite Loss and Grief : A Psychoeducational Approach; Paul H. Brookes Pub. Baltimore, Md.: Baltimore, Md, 2001; ISBN 1-55766-517-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gelderman, G. To Be Alive in the World Right Now: Climate Grief in Young Climate Organizers. Master’s Thesis, Theological Studies, St. Stephen’s College: Edmonton, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, D.L. Nonfinite Loss: Living with Ongoing Loss and Grief. In Non-Death Loss and Grief: Context and Clinical Implications; Harris, D.L., Ed.; Routledge: New York, 2020; pp. 139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Ágoston, C.; Csaba, B.; Nagy, B.; Kőváry, Z.; Dúll, A.; Rácz, J.; Demetrovics, Z. Identifying Types of Eco-Anxiety, Eco-Guilt, Eco-Grief, and Eco-Coping in a Climate-Sensitive Population: A Qualitative Study. International journal of environmental research and public health 2022, 19, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marczak, M.; Winkowska, M.; Chaton-Østlie, K.; Morote Rios, R.; Klöckner, C.A. “When I Say I’m Depressed, It’s like Anger.” An Exploration of the Emotional Landscape of Climate Change Concern in Norway and Its Psychological, Social and Political Implications. Emotion, Space and Society 2023, 46, 100939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D.L. Pulling It All Together - Change, Loss, and Transition. In Non-Death Loss and Grief: Context and Clinical Implications; Harris, D.L., Ed.; Routledge: New York, 2020; pp. 291–295. [Google Scholar]

- Norgaard, K.M. Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life; MIT Press: Cambridge, 2011; ISBN 978-0-262-29577-2. [Google Scholar]

- Jamail, D. End of Ice: Bearing Witness and Finding Meaning in the Path of Climate Disruption.; The New Press: New York, 2019; ISBN 978-1-62097-234-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.E.; Wray, B.; Mellor, C.; Susteren, L. van Climate Anxiety in Children and Young People and Their Beliefs about Government Responses to Climate Change: A Global Survey. The Lancet Planetary Health 2021, 5, e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galway, L.P.; Field, E. Climate Emotions and Anxiety among Young People in Canada: A National Survey and Call to Action. The Journal of Climate Change and Health 2023, 9, 100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, T. Ecologies of Guilt in Environmental Rhetorics; Palgrave studies in media and environmental communication; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-05650-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, S.M. For the Wild: Ritual and Commitment in Radical Eco-Activism; University of California Press: Oakland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Menning, N. Environmental Mourning and the Religious Imagination. In Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss & Grief; Cunsolo Willox, A., Landman, K., Eds.; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal & Kingston, 2017; pp. 39–63. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, T. Ecological Grief and Anthropocene Horror. American Imago 2020, 77, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.J.; Beck, E. Disenfranchised Grief and Nonfinite Loss as Experienced by the Families of Death Row Inmates. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying 2006, 54, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kool, R.; Kelsey, E. Dealing with Despair: The Psychological Implications of Environmental Issues. In Innovative approaches to education for sustainable development; Filho, W.L., Salomone, M., Eds.; Environmental Education, Communication and Sustainability Vol. 25; Peter Lang: Frankfurt, 2006; pp. 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, P. Death, the Environment, and Theology. Dialog 2018, 57, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, D. How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Eco-Apocalypse: An Existential Approach to Accepting Eco-Anxiety. Perspect Psychol Sci 2022, 17456916221093612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Kessel, C. Teaching the Climate Crisis: Existential Considerations. Journal of Curriculum Studies Research 2020, 2, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehling, J.T. Conceptualising Eco-Anxiety Using an Existential Framework. South African Journal of Psychology 2022, 52, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, K. There Is No Alternative: A Symbolic Interactionist Account of Swedish Climate Activists, Lund University, Department of Sociology, 2019, Vol. Master’s Thesis.

- Budziszewska, M.; Jonsson, S.E. From Climate Anxiety to Climate Action: An Existential Perspective on Climate Change Concerns Within Psychotherapy. The Journal of humanistic psychology 2021, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passmore, H.-A.; Lutz, P.K.; Howell, A.J. Eco-Anxiety: A Cascade of Fundamental Existential Anxieties. Journal of Constructivist Psychology 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoff-Bulman, R. Shattered Assumptions: Towards a New Psychology of Trauma; Free Press & Maxwell Macmillan Canada: New York & Toronto, 1992; ISBN 0-02-916015-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, S.S.; Malkinson, R.; Witztum, E. Traumatic Bereavements: Rebalancing the Relationship to the Deceased and the Death Story Using the Two-Track Model of Bereavement. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.B.; Zinner, E.S.; Ellis, R.R. The Connection Between Grief and Trauma: An Overview. In When A Community Weeps; Routledge: New York, 1998; pp. 3–17. ISBN 978-0-203-77801-2. [Google Scholar]

- Van Deurzen, E. Rising from Existential Crisis: Life beyond Calamity; PCCS Books Monmouth, UK: Monmouth, UK, 2021; ISBN 1-910919-85-3. [Google Scholar]

- Vos, J. The Meaning Sextet: A Systematic Literature Review and Further Validation of a Universal Typology of Meaning in Life. Journal of Constructivist Psychology 2023, 36, 204–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl, V. Man’s Search for Meaning; Beacon Press: Boston, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Attig, T. Seeking Wisdom about Mortality, Dying, and Bereavement. In Death, Dying, and Bereavement: Contemporary Perspectives, Institutions, and Practices; Attig, T., Stillion, J.M., Eds.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, 2015; pp. 1–15. ISBN 0826171427. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, C.M. Bereavement as a Psychosocial Transition: Processes of Adaptation to Change. Journal of Social Issues 1988, 44, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R.A.; Burke, L.A.; Mackay, M.M.; van Dyke Stringer, J.G. Grief Therapy and the Reconstruction of Meaning: From Principles to Practice. J Contemp Psychother 2010, 40, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R.A. Treating Complicated Bereavement: The Development of Grief Therapy. In Death, Dying, and Bereavement: Contemporary Perspectives, Institutions, and Practices; Attig, T., Stillion, J.M., Eds.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, 2015; pp. 307–320. ISBN 0826171427. [Google Scholar]

- Smid, G.E. A Framework of Meaning Attribution Following Loss. European journal of psychotraumatology 2020, 11, 1776563–1776563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlie, B. Bearing Worlds: Learning to Live-with Climate Change. Environmental Education Research 2019, 25, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B. States of Emergency: Trauma and Climate Change. Ecopsychology 2015, 7, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodbury, Z. Climate Trauma: Toward a New Taxonomy of Trauma. Ecopsychology 2019, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, K.I.; Exline, J.J. Working with Spiritual Struggles in Psychotherapy : From Research to Practice; Guilford Publications New York: New York, 2022; ISBN 978-1-4625-4789-0. [Google Scholar]

- Vos, J. Meaning in Life: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Practitioners; Bloomsbury: London, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, F. Like There’s No Tomorrow: Climate Crisis, Eco-Anxiety and God; Sacristy Press: Durham, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Words for a Dying World: Stories of Grief and Courage from the Global Church; Malcolm, H., Ed.; SCM Press: London, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, P. Eco-Anxiety and Pastoral Care: Theoretical Considerations and Practical Suggestions. Religions 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, L.A.; Crunk, A.E.; Neimeyer, R.A.; Bai, H. Inventory of Complicated Spiritual Grief 2.0 (ICSG 2.0): Validation of a Revised Measure of Spiritual Distress in Bereavement. Death studies 2021, 45, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T. Fierce Consciousness: Surviving the Sorrows of Earth and Self; Calliope Books, 2023; ISBN 9798218063894. [Google Scholar]

- Doka, K. Disenfranchised Grief and Non-Death Losses. In Non-Death Loss and Grief: Context and Clinical Implications; Harris, D.L., Ed.; Routledge: New York, 2020; pp. 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kalich, D.; Brabant, S. A Continued Look at Doka’s Grieving Rules: Deviance and Anomie as Clinical Tools. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying 2006, 53, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doka, K.J. Disenfranchised Grief; Lexington Books: Lexington, Mass, 1989; ISBN 0-669-17081-X. [Google Scholar]

- Doka, K.J. Disenfranchised Grief: New Directions, Challenges, and Strategies for Practice; Research Press Champaign, Ill.: Champaign, Ill, 2002; ISBN 0-87822-427-0. [Google Scholar]

- Diffey, J.; Wright, S.; Uchendu, J.O.; Masithi, S.; Olude, A.; Juma, D.O.; Anya, L.H.; Salami, T.; Mogathala, P.R.; Agarwal, H.; et al. “Not about Us without Us” – the Feelings and Hopes of Climate-Concerned Young People around the World. International Review of Psychiatry 2022, 34, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bosch, H. Grieving Nature in a Time of Climate Change: An Eco-Feminist Reflection on the Contemporary Responses towards Eco-Grief from a Perspective of Injustice. MA Thesis, Philosophy of Contemporary Challenges, Tilburg University Humanities Faculty: Tilburg, 2020.

- Corr, C.A. Enhancing the Concept of Disenfranchised Grief. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying 1999, 38, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corr, C.A. Rethinking the Concept of Disenfranchised Grief. In Disenfranchised grief: New directions, challenges, and strategies for practice; Doka, K.J., Ed.; Research Press Champaign, Ill.: Champaign, Ill, 2002; pp. 39–60. ISBN 0-87822-427-0. [Google Scholar]

- Attig, T. Disenfranchised Grief Revisited: Discounting Hope and Love. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying 2004, 49, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, N. The Social Context of Loss and Grief. In Non-Death Loss and Grief: Context and Clinical Implications; Harris, D.L., Ed.; Routledge: New York, 2020; pp. 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, G. Don’t Even Think about It: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Ignore Climate Change; Bloomsbury Publishing USA: New York, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stoknes, P.E. What We Think About When We Try Not To Think About Global Warming: Toward a New Psychology of Climate Action; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R.; Lacroix, K.; Chen, A. Understanding Responses to Climate Change: Psychological Barriers to Mitigation and a New Theory of Behavioral Choice. In Psychology and climate change: human perceptions, impacts, and responses; Clayton, S.D., Manning, C.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, 2018; pp. 161–183. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholsen, S.W. The Love of Nature and the End of the World: The Unspoken Dimensions of Environmental Concern; MIT Press: Cambridge, 2002; ISBN 0-262-14076-4. [Google Scholar]

- Burton-Christie, D. The Gift of Tears: Loss, Mourning and the Work of Ecological Restoration. Worldviews: Global Religions, Culture, and Ecology 2011, 15, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertzman, R.A. Environmental Melancholia: Psychoanalytic Dimensions of Engagement; Routledge: Hove and New York, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hoggett, P. Climate Psychology: On Indifference to Disaster; Studies in the Psychosocial; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Neimyer, R.A.; Jordan, J.R. Disenfranchisement as Empathic Failure: Grief Therapy and the Co-Construction of Meaning. In Disenfranchised grief: New directions, challenges, and strategies for practice; Doka, K.J., Ed.; Research Press Champaign, Ill.: Champaign, Ill, 2002; pp. 95–117. ISBN 0-87822-427-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalainen, R. ; Seppo, Sanni. Metsänhoidollisia Toimenpiteitä; Hiilinielu: Kemiö, 2009; ISBN 978-952-99113-4-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar, S.; Aljovin, P.; O’Neill, P.; Alavi, S.; Gamoran, J.; Liaqat, A.; Bitensky, D.; Bi, H.; Grella, E.; Kiefer, M.; et al. The Environment as an Object Relationship: A Two-Part Study. Ecopsychology 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, N. Discrimination, Oppression, and Loss. In Non-Death Loss and Grief: Context and Clinical Implications; Harris, D.L., Ed.; Routledge: New York, 2020; pp. 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, K.P. Is It Colonial Déjà vu? Indigenous Peoples and Climate Injustice. In Humanities for the Environment: Integrating knowledge, forging new constellations of practice; Adamson, J., Davis, M., Eds.; Routledge, 2017; pp. 88–104. [Google Scholar]

- Rinofner-Kreidl, S. On Grief’s Ambiguous Nature. Quaestiones Disputatae 2016, 7, 178–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, S. Affective Intentionality and Affective Injustice: Merleau-Ponty and Fanon on the Body Schema as a Theory of Affect. The Southern journal of philosophy 2018, 56, 488–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, A. The Aptness of Anger. The journal of political philosophy 2018, 26, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, E. The Denial of Death; Free Press: New York, 1973; ISBN 0-02-902150-2. [Google Scholar]

- Pienaar, M. An Eco-Existential Understanding of Time and Psychological Defenses: Threats to the Environment and Implications for Psychotherapy. Ecopsychology 2011, 3, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P. Remembering and Honoring Linda Zhang. The Inside Press 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mosquera, J.; Jylhä, K.M. How to Feel About Climate Change? An Analysis of the Normativity of Climate Emotions. International Journal of Philosophical Studies 2022, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, S. Chronic Sorrow: A Living Loss; Second edition.; Routledge: New York, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Roos, S. Chronic Sorrow. In Non-Death Loss and Grief: Context and Clinical Implications; Harris, D.L., Ed.; Routledge: New York, 2020; pp. 192–204. [Google Scholar]

- Hoggett, P.; Randall, R. Engaging with Climate Change: Comparing the Cultures of Science and Activism. Environmental Values 2018, 27, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.C. Waves of Grief and Anger: Communicating through the “End of the World” as We Knew It. In Global Views on Climate Relocation and Social Justice; Ajibade, I.J., Siders, A.R., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon, GBR, 2021; p. Chapter 20. ISBN 978-1-00-314145-7. [Google Scholar]

- Doppelt, B. Transformational Resilience: How Building Human Resilience to Climate Disruption Can Safeguard Society and Increase Wellbeing; Taylor & Francis: Saltaire, 2016; ISBN 978-1-351-28387-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, P. The Cost of Bearing Witness to the Environmental Crisis: Vicarious Traumatization and Dealing with Secondary Traumatic Stress among Environmental Researchers. Social Epistemology: The Cost of Bearing Witness: Secondary Trauma and Self-Care in Fieldwork-Based Social Research; Guest Editors: Nena Močnik and Ahmad Ghouri 2020, 34, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celermajer, D. Summertime: Reflections on a Vanishing Future; Unabridged.; Penguin Random House: London, 2021; ISBN 9781761042836; 1761042831. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, S.R. Life Trajectories of Youth Committing to Climate Activism. Environmental education research 2016, 22, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toiviainen, P. Ilmastonmuutos.Nyt; Otava: Helsinki, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Solastalgia: An Anthology of Emotion in a Disappearing World; Bogard, P., Ed.; University of Virginia Press Charlottesville: Charlottesville, 2023; ISBN 978-0-8139-4885-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann, E. Symptomatology and Management of Acute Grief. American Journal of Psychiatry 1944, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loss and Anticipatory Grief; Rando, T.A., Ed.; The Free Press: Lexington, Mass, 1986; ISBN 978-0-669-11144-6. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton, G.; Madden, C.; Minichiello, V. The Social Construction of Anticipatory Grief. Soc Sci Med 1996, 43, 1349–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, A. Climate Change as the Work of Mourning. In Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss & Grief; Cunsolo, A., Landman, K., Eds.; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal & Kingston, 2017; pp. 169–189. [Google Scholar]

- Mark, A.; Di Battista, A. Making Loss the Centre: Podcasting Our Environmental Grief. In Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss and Grief; Cunsolo Willox, A., Landman, K., Eds.; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal & Kingston, 2017; pp. 227–257. [Google Scholar]

- Barr, J.M. Auguries of Elegy: The Art and Ethics of Ecological Grieving. In Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss & Grief; Cunsolo Willox, A., Landman, K., Eds.; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal & Kingston, 2017; pp. 190–226. [Google Scholar]

- Moratis, L. Proposing Anticipated Solastalgia as a New Concept on the Human-Ecosystem Health Nexus. Ecohealth 2021, 18, 411–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical Dimensions of Anticipatory Mourning: Theory and Practice in Working with the Dying, Their Loved Ones, and Their Caregivers; Rando, T.A., Ed.; Research Press Champaign, Ill.: Champaign, Ill, 2000; ISBN 978-0-87822-380-0. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton, R. Anticipatory Mourning: A Critique of the Concept. Mortality (Abingdon, England) 2003, 8, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, J. On Robert Fulton’s Anticipatory Mourning: A Critique of the Concept. Mortality (Abingdon, England) 2005, 10, 155–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, D. Beyond Ecophobia: Reclaiming the Heart in Nature Education; Orion Society: Great Barrington, 1996; ISBN 0-913098-50-7. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, P. Environmental Education After Sustainability: Hope in the Midst of Tragedy. Global Discourse 2017, 7, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, B.M.H.; Fischer, B.; Clayton, S. Should We Connect Children to Nature in the Anthropocene? People and Nature 2022, 4, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, A. The Affective Legacy of Silent Spring. Environmental Humanities 2012, 1, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.C. Whither the Heart(-to-Heart)? Prospects for a Humanistic Turn in Environmental Communication as the World Changes Darkly. In Handbook on Environment and Communication; Hansen, A., Cox, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, 2015; pp. 402–413. [Google Scholar]

- Verlie, B. Learning to Live with Climate Change: From Anxiety to Transformation; Routledge Focus; Routledge: London, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Plant, B. Living Posthumously: From Anticipatory Grief to Self-Mourning. Mortality (Abingdon, England) 2022, 27, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attig, T. Coping with Mortality: An Essay on Self-Mourning. Death studies 1989, 13, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalom, I.D. Existential Psychotherapy; Basic Books: New York, 1980; ISBN 0-465-02147-6. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, J. After Sustainability: Denial, Hope, Retrieval; Routledge: London and New York, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, J.L. The People Paradox: Self-Esteem Striving, Immortality Ideologies, and Human Response to Climate Change. Ecology & Society 2009, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kurth, C. The Anxious Mind: An Investigation into the Varieties and Virtues of Anxiety; The MIT Press: Cambridge, 2018; ISBN 978-0-262-03765-5. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, E.R. Grief in Freud’s Life: Reconceptualizing Bereavement in Psychoanalytic Theory. Psychoanalytic psychology 1996, 13, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T. Radical Joy for Hard Times: Finding Meaning and Making Beauty in Earth’s Broken Places; North Atlantic Books: Berkeley, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, P. Climate Anxiety, Maturational Loss and Adversarial Growth. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child 2024, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, D.; O’Callaghan, A.; Guérandel, A. “Don’t Look Up”: Eco-Anxiety Presenting in a Community Mental Health Service. Irish journal of psychological medicine 2023, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budziszewska, M.; Kałwak, W. Climate Depression. Critical Analysis of the Concept. Psychiatr. Pol. 2022, 56, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prigerson, H.G.; Shear, M.K.; Reynolds, C.F. Prolonged Grief Disorder Diagnostic Criteria—Helping Those With Maladaptive Grief Responses. JAMA psychiatry (Chicago, Ill.) 2022, 79, 277–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, T.M.; Tofthagen, C.S.; Buck, H.G. Complicated Grief: Risk Factors, Protective Factors, and Interventions. Journal of social work in end-of-life & palliative care 2020, 16, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Stroebe, M.; Chan, C.L.W.; Chow, A.Y.M. Guilt in Bereavement: A Review and Conceptual Framework. Death Stud 2014, 38, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weintrobe, S. Psychological Roots of the Climate Crisis: Neoliberal Exceptionalism and the Culture of Uncare; Bloomsbury: New York, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kałwak, W.; Weihgold, V. The Relationality of Ecological Emotions: An Interdisciplinary Critique of Individual Resilience as Psychology’s Response to the Climate Crisis. Frontiers in psychology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szuhany, K.L.; Malgaroli, M.; Miron, C.D.; Simon, N.M. Prolonged Grief Disorder: Course, Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment. FOC 2021, 19, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macy, J.; Brown, M.Y. Coming Back to Life: The Updated Guide to the Work That Reconnects; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Susteren, L.V.; Al-Delaimy, W.K. Psychological Impacts of Climate Change and Recommendations. In Health of People, Health of Planet and Our Responsibility: Climate Change, Air Pollution and Health; Al-Delaimy, W.K., Ramanathan, V., Sánchez Sorondo, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2020; pp. 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, E.A. Is Climate-Related Pre-Traumatic Stress Syndrome a Real Condition? American Imago 2020, 77, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, J.; Pantesco, V.; Plemons, K.; Gupta, R.; Rank, S.J. Sustaining the Conservationist. Ecopsychology 2013, 5, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, L.; Harada, T. Keeping the Heart a Long Way from the Brain: The Emotional Labour of Climate Scientists. Emotion, Space and Society 2017, 24, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, F. The Wild Edge of Sorrow: Rituals of Renewal and the Sacred Work of Grief; North Atlantic Books: Berkeley, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, O.; Rigby, K.; Williams, L. Everyday Ecocide, Toxic Dwelling, and the Inability to Mourn: A Response to Geographies of Extinction. Environmental Humanities 2020, 12, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wielink, J.; Wilhelm, L.; van Geelen-Merks, D. Loss, Grief, and Attachment in Life Transitions: A Clinician’s Guide to Secure Base Counseling; Death, Dying and Bereavement; Routledge & CRC Press: New York, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brondizio, E.S.; O’Brien, K.; Bai, X.; Biermann, F.; Steffen, W.; Berkhout, F.; Cudennec, C.; Lemos, M.C.; Wolfe, A.; Palma-Oliveira, J.; et al. Re-Conceptualizing the Anthropocene: A Call for Collaboration. Global Environmental Change 2016, 39, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markard, J.; Raven, R.; Truffer, B. Sustainability Transitions: An Emerging Field of Research and Its Prospects. Research Policy 2012, 41, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, M.K.; Stock, P. “You’re Asking Me to Put into Words Something That I Don’t Put into Words.”: Climate Grief and Older Adult Environmental Activists. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, T. Grief, Melancholy, and Depression. In Cultural, existential and phenomenological dimensions of grief experience; Køster, A., Kofod, E.H., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon; New York, 2022; pp. 11–24. ISBN 978-0-367-56811-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, J. The Edge of Extinction : Travels with Enduring People in Vanishing Lands; Cornell University Press Ithaca, NY: Ithaca, NY, 2015; ISBN 978-0-8014-5504-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, R.A. Rough and Plenty: A Memorial; Life writing series; Wilfrid Laurier University Press Waterloo, Ontario: Waterloo, Ontario, 2020; ISBN 1-77112-438-5. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.W. Phenomenology. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Zalta, E.N., Ed.; Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2018.

- Beyer, C. Edmund Husserl. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Zalta, E.N., Nodelman, U., Eds.; Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2022.

- Fairtlough, G.H. Habermas’ Concept of “Lifeworld”. Systems Practice 1991, 4, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breyer, T.; Widlok, T. The Situationality of Human-Animal Relations: Perspectives from Anthropology and Philosophy / Thiemo Breyer, Thomas Widlok (Eds.).; Human-animal studies ; volume 15; Transcript-Verlag: Bielefeld, 2018; ISBN 3-8394-4107-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, J.C. Where Have All the Boronia Gone? A Posthumanist Model of Environmental Mourning. In Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss & Grief; Cunsolo, A., Landman, K., Eds.; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal & Kingston, 2017; pp. 117–143. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, K. Transdisciplinary Journeys in the Anthropocene: More-than-Human Encounters; Routledge Environmental Humanities; Routledge: London & New York, 2017; ISBN 978-1-138-91114-7. [Google Scholar]

- Spark, A. The Authentic Hypocrisy of Ecological Grief. In Vulnerable Witness: The Politics of Grief in the Field; Gillespie, K., Lopez, P.J., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, 2019; pp. 80–90. ISBN 978-0-520-97003-8. [Google Scholar]

- Dooren, T. van Flight Ways: Life and Loss at the Edge of Extinction; Columbia University Press: New York, 2014; p. 208 Pages; ISBN 978-0-231-53744-5.

- Bowman, T. The Threshold of Shattered Dreams. In Non-Death Loss and Grief: Context and Clinical Implications; Harris, D.L., Ed.; Routledge: New York, 2020; pp. 243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C. Life in the Shadows: Young People’s Experiences of Climate Change Futures. Futures 2023, 154, 103264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkkonen, J. Nuorten ilmastotoimijoiden kerronnallisesti rakentuvat aktivisti-identiteetit. Master’s Thesis, Philosophical faculty, School of Educational Sciences and Psychology, Psychology, University of Eastern Finland: Joensuu, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- admin, A. Eco Nightmare: Shattered Dreams, Broken Future. Aliran 2020.

- Zulfiqar, S. Hopes and Dreams Shattered by Climate Change. Available online: https://www.3blmedia.com/news/hopes-and-dreams-shattered-climate-change (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Hickman, C. We Need to (Find a Way to) Talk about … Eco-Anxiety. Journal of Social Work Practice 2020, 34, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friederici, P. Beyond Climate Breakdown : Envisioning New Stories of Radical Hope; One planet (MIT Press); The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2022; ISBN 978-0-262-54393-4. [Google Scholar]

- Crandon, T.J.; Scott, J.G.; Charlson, F.J.; Thomas, H.J. A Social–Ecological Perspective on Climate Anxiety in Children and Adolescents. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2022, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.T.; O’Connor, M.-F. From Grief to Grievance: Combined Axes of Personal and Collective Grief Among Black Americans. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroebe, M.; Schut, H. Overload: A Missing Link in the Dual Process Model? Omega (Westport) 2016, 74, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S.L.; Cunsolo, A.; Aylward, B.; Clayton, S.; Minor, K.; Cooper, M.; Vriezen, R. Estimating Climate Change and Mental Health Impacts in Canada: A Cross-Sectional Survey Protocol. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0291303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczak, M.; Wierzba, M.; Kossowski, B.; Marchewka, A.; Rios, R.M.; Klöckner, C.A. Emotional Responses to Climate Change in Norway and Ireland: Cross-Cultural Validation of the Inventory of Climate Emotions (ICE) 2023.

- Calhoun, L.G.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Cann, A.; Hanks, E.A. Positive Outcomes Following Bereavement: Paths to Posttraumatic Growth. Psychologica Belgica 2010, 50, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Shakespeare-Finch, J.; Kanako, T.; Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic Growth: Theory, Research, and Applications; Routledge: New York, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Blackie, L.E.R.; Weststrate, N.M.; Turner, K.; Adler, J.M.; McLean, K.C. Broadening Our Understanding of Adversarial Growth: The Contribution of Narrative Methods. Journal of Research in Personality 2023, 103, 104359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Culture, Lifestyle, Traditions & Heritage Physical health Mental and Emotional Well-being Human Mobility Indirect Economic Benefits and Opportunities Sense of place Social fabric Ecosystem Services, Biodiversity and Species Productive Land and Habitat Knowledge and Ways of Knowing Human life [span] Identity Self-determination and Influence Order in the world Dignity Territory Ability to Solve Problems Collectively Sovereignty |

| Type of ambiguous loss | Example | Ecological loss example |

| Physically absent but psychologically present | a soldier missing in action | ambiguous loss of birds which are expected to be present |

| Psychologically absent but physically present | a person with dementia | a nearby forest still standing but without biodiversity |

| Aspect of nonfinite loss | Themes | Examples of similar dynamics in eco-emotion studies |

| "There is an ongoing uncertainty regarding what will happen next. Anxiety is often the primary undercurrent to the experience." | The central role of uncertainty; anxiety as closely intertwined with loss | Overview: Pihkala 2020 [30] |

| "There is often a sense of disconnection from the mainstream and what is generally viewed as 'normal' in human experience." | Feeling apart from others, possible attempts of pathologization by others, possible isolation | Norgaard (2011), Kretz (2017) [96,118] |

| "The magnitude of the loss is frequently unrecognized or not acknowledged by others." | Disenfranchized grief, lack of recognition of mourners, or lack of acknowledgement of the actual severity of the loss | Jamail (2019), Gillespie (2020) [86,119] |

| "There is an ongoing sense of helplessness and powerlessness associated with the loss." | helplessness, powerlessness | Hickman et al. (2021), Galway & Field (2023) [120,121] |

| "Nonfinite losses may be accompanied by shame, embarrassment, and self-doubting that further complicates existing relationships, thereby adding to the struggle with coping." | shame, embarrassment, implicitly guilt, possible self-doubting and low self-esteem | Jensen (2019); Ágoston et al. (2022) [35,122] |

| "There are typically no rituals that assist to validate or legitimize the loss, especially if the loss was symbolic or intangible." | lack of rituals | Pike (2017); Menning (2017) [123,124] |

| "chronic despair and ongoing dread" (added by Jones & Beck 2007) | chronic despair, ongoing dread, and other similar phenomena with various terms | Macy (1983), Clark (2020) [18,125] |

| Concept or framework | General sources | Main ideas | Examples of similar dynamics in ecological loss and grief |

| Shattered assumptions | Janoff-Bulman 1992 | Major loss and trauma can shatter fundamental assumptions about self and world | Verlie 2019 |

| Existential crisis | van Deurzen 2021 | Events in life and the world can cause people deep existential turmoil | Rehling 2022; Budzisewska & Jonsson 2021 |

| Relearning the world | Attig 2015 | Deep processes of grief and loss require relearning the world and one’s relation to it | Newby 2022; Wray 2022 |

| Meaning reconstruction | Neimeyer 2019 | Major loss causes the need to work through changes in one’s meaning system and narrative understanding of life | Passmore et al. 2022; Jamail 2019 |

| Spiritual crisis | Pargament & Exline 2022 | Major loss can trigger religious and spiritual crises | Ward 2020 |

| Complicated spiritual grief | Burke et al. 2021 | Spiritual grief can become complicated and include e.g. isolation | Malcolm 2020 |

| Dynamic | Example | Ecological grief literature and related dynamics |

| The relationship is not recognized (Doka 2020) | An extra-marital lover is not allowed to grieve | Kinship with non-human others not recognized, e.g. Braun 2017 [99] |

| The loss is not acknowledged (Doka 2020) | Intangible losses are not recognized | Tschakert et al. 2017 [93] |

| The griever is excluded (Doka 2020) |

A young child is deemed incapable of grieving | Ecological mourners excluded, e.g. Kretz 2017 [96] |

| Circumstances of loss (Doka 2020) |

Death due to drug abuse produces stigma and silence | Suicides of people who feel severe eco-depression and grief? |

| Ways of grieving (Doka 2020) |

A family member presupposes that another should grieve exactly in a similar way with them | Normative understandings of ways of ecological grieving? |

| Grief reactions and expressions of them (Corr 2002) | Not allowing a strong grief reaction | Allowing a mild ecological grief but not a strong form of it, Cunsolo & Landman 2017 [12] |

| Mourning and rituals (Corr 2002) |

Not allowing a particular mourning ritual | No funeral for non-human animals, DeMello 2016 [98] |

| Outcomes of grief (Corr 2002) |

Not allowing grief which lasts long | Social disapproval of certain outcomes of ecological grief? |

| Disenfranchising because of existential anxieties (Rinofner-Kreidl 2016) |

Not allowing a grief response because it reminds of mortality | Nicholsen 2002 [169] |

|

Characteristics of chronic sorrow (Roos 2020) |

Ecological grief literature about similar characteristic |

| “(A) its non-pathological nature” | Comtesse et al. (2021) [48] |

| “(B) its essential disenfranchisement” | Cunsolo & Ellis (2018) [2] |

| “(C) references to self- and/or other-loss” | Lertzman (2015) [171] |

| “(D) its frequent traumatic onset” | Hoggett & Randall (2018) [187] |

| “(E) its having no foreseeable end” | Saint-Amour (2020) [55] |

| “(F) constant reminders or triggers” | Gillespie (2020) [86] |

| “(G) unavoidable, periodic resurgences of intensity” | Moser (2021) [188] |

| “(H) predictable and unpredictable stress points” | Wray (2022) [84] |

| “(I) not being a state of permanent despair” | Stoknes (2015) [167] |

| “(J) continuation of functioning by the affected person” | Doppelt (2016) [189] |

| Concept | Key idea and an example of research | Example in context of ecological grief |

| Anticipatory grief | Grieving in advance [195] | Grieving anticipated ecological losses beforehand [2] |

| Anticipatory mourning | Rando’s proposal for a wider framework [202] | Ecological mourning which includes also reactions to ongoing losses and transformation [58] |

| Decathexis | Removing emotional bonds from a (lost) object; historical links to Freud, see [217] | Similarities with biofobia as defined by Sobel [205] |

| Continuing bonds | People wish to continue emotional bonds with the lost person [74] | Finding ways to still be in contact with a damaged environment [218] |

| Transitional loss | Losses felt due a transition in life [47] | Losses related to transitions brought by the climate crisis [47] |

| Maturational loss | Losses related to changing life stages, can exist along felt gains [75] | Growing up amidst the climate crisis brings various maturational losses [219] |

| Self-mourning | Anticipatory grief/mourning includes a dimension of mourning one’s own mortality [211] | Ecological grief can activate self-mourning about one’s own mortality [182] |

|

| Concept | Local ecological grief | Global ecological grief |

| Tangible / intangible loss | Often heavy tangible aspects; many potential intangible aspects | Amount of tangible aspects varies between contexts; very many potential intangible aspects |

| Ambiguous loss | Often | Many aspects |

| Nonfinite loss | Sometimes | Very clearly |

| Shattered assumptions | Sometimes | Prominently |

| Disenfranchised grief | Very often | Very often |

| Chronic sorrow | Sometimes | Dominantly |

| Anticipatory grief/mourning | Often | Often |

| Transitional loss and grief | Very often | A prominent dynamic |

| Lifeworld loss | If happens, deeply felt | Global lifeworld loss? |

| Shattered dreams | Sometimes (often?) | Often |

|

Ambiguous loss (Boss 2020) |

Nonfinite loss (Schultz & Harris 2011) |

| Finding meaning | Name and validate the loss(es). |

| Adjusting mastery | Normalize the ongoing nature of the loss. |

| Reconstructing identity | Find supports and resources. |

| Normalizing ambivalence | Recognize the loss(es) and identify what is not lost. |

| Revising attachment | Allow for the possibility of meaning making and growth. |

| Discovering new hope and purpose for life | Initiate rituals where none exist. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).