Submitted:

13 November 2023

Posted:

14 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

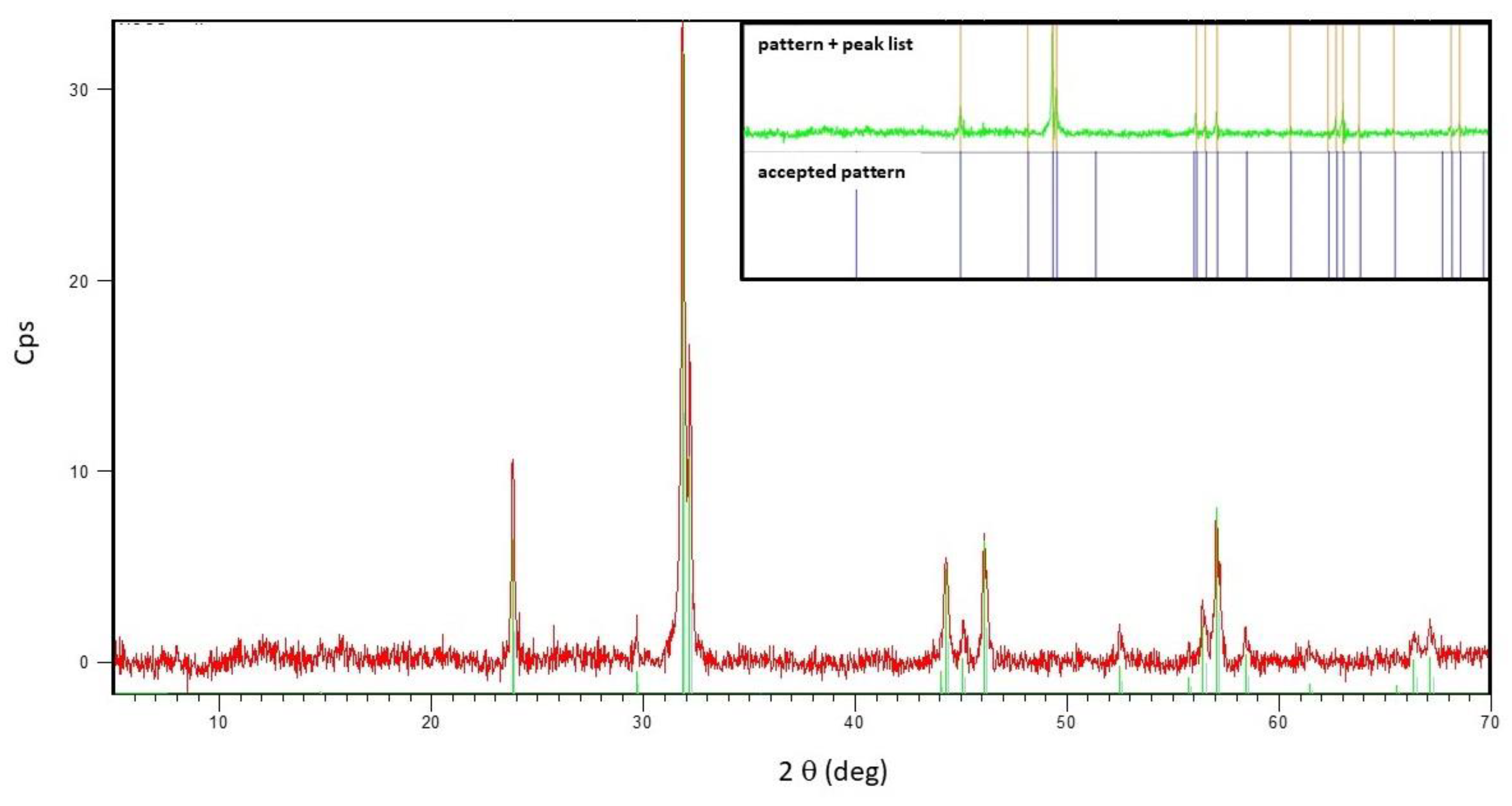

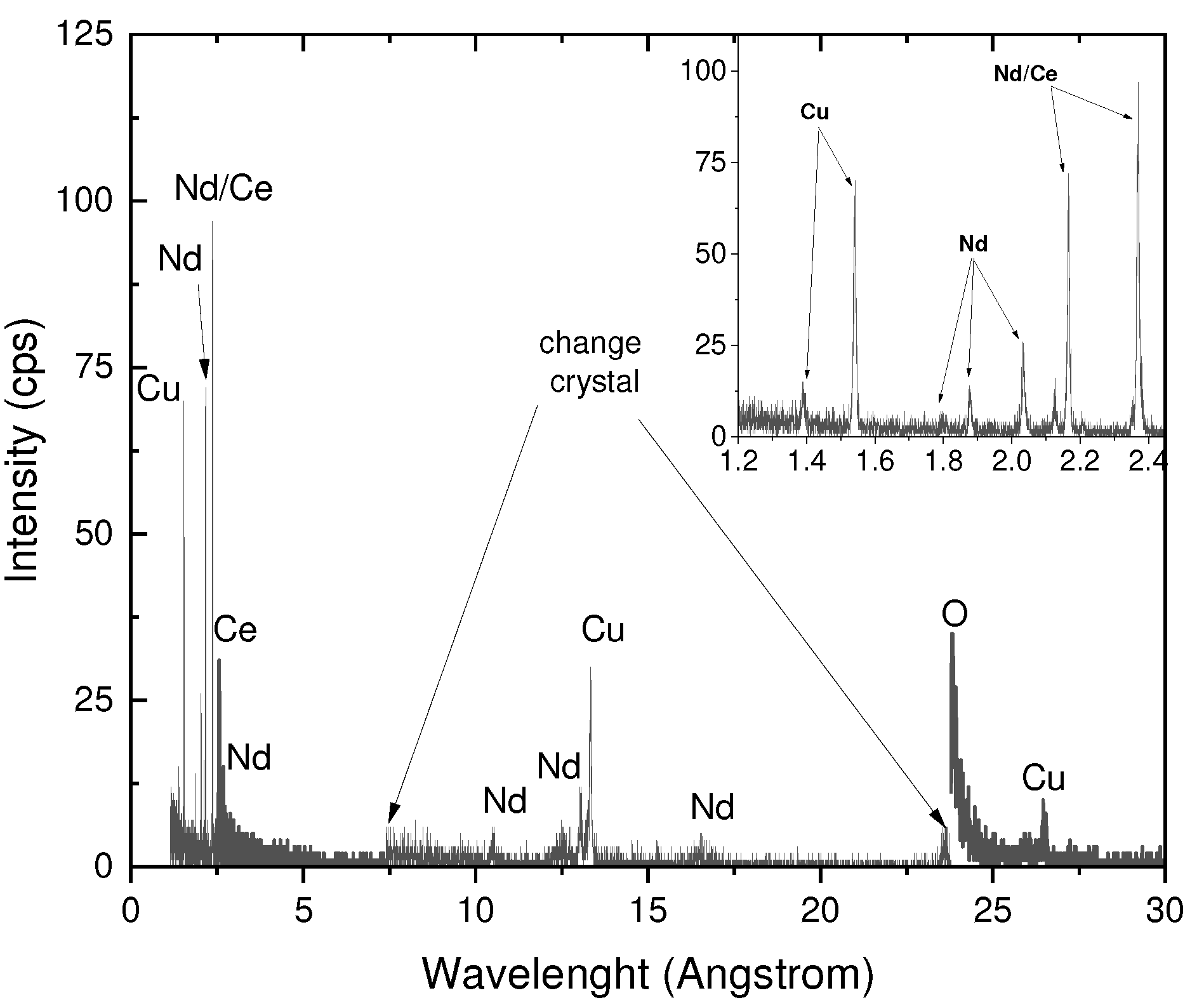

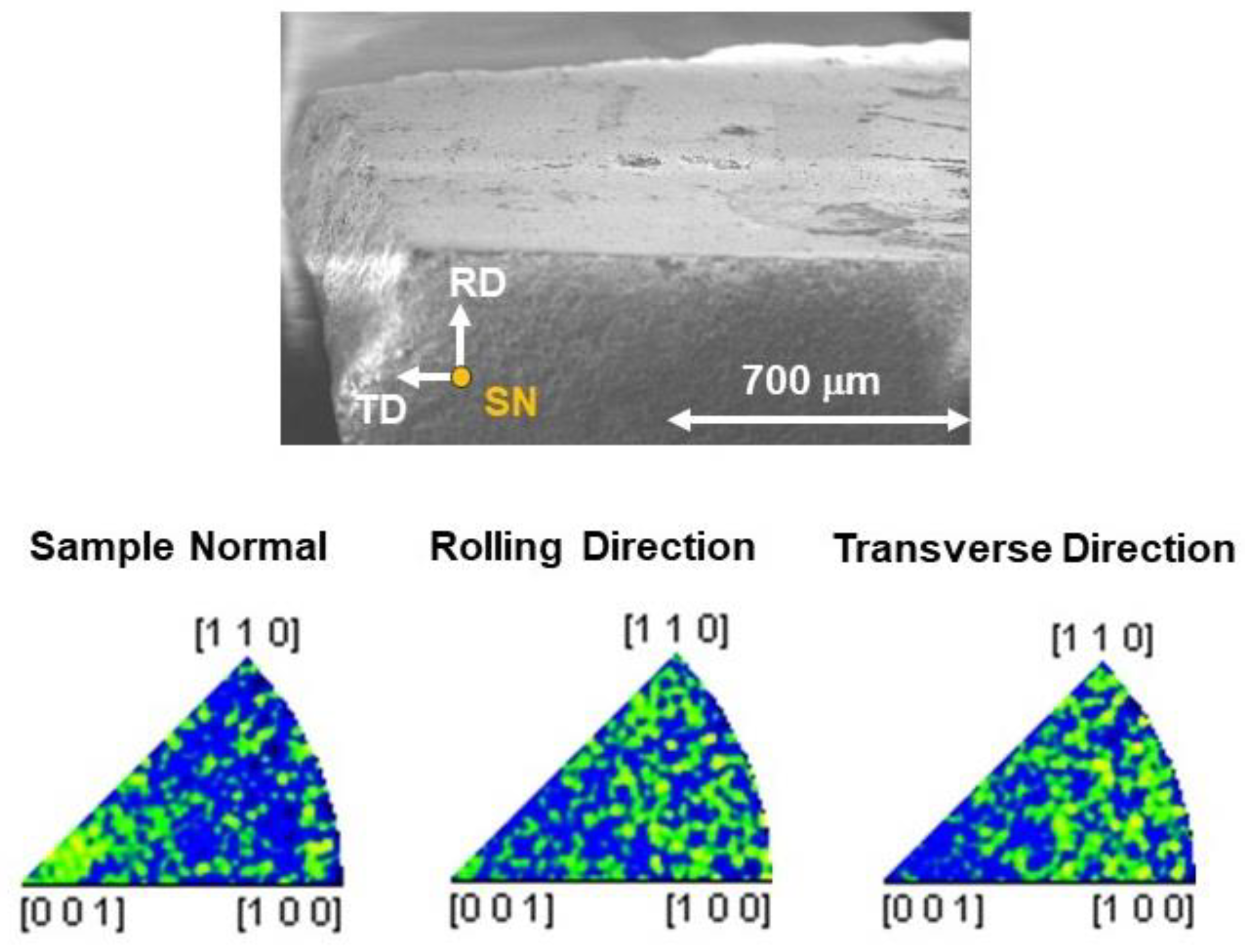

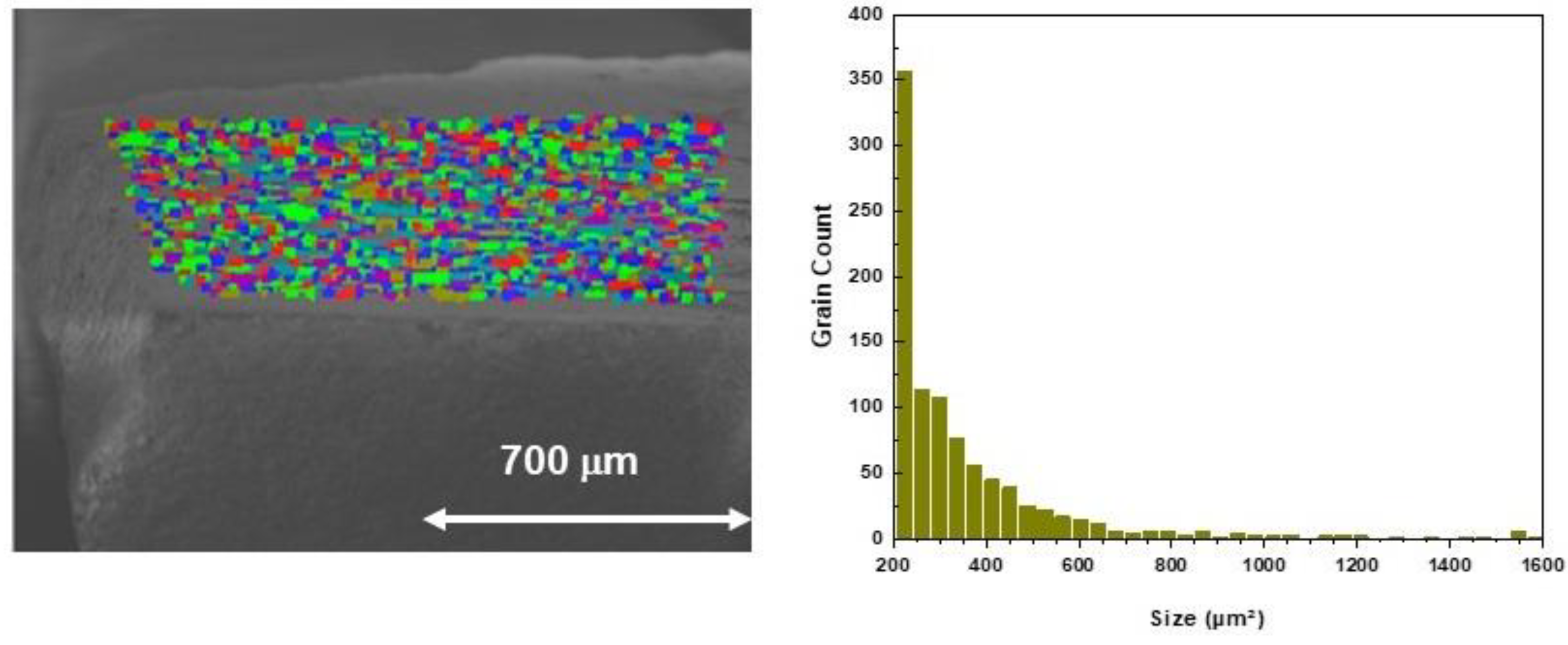

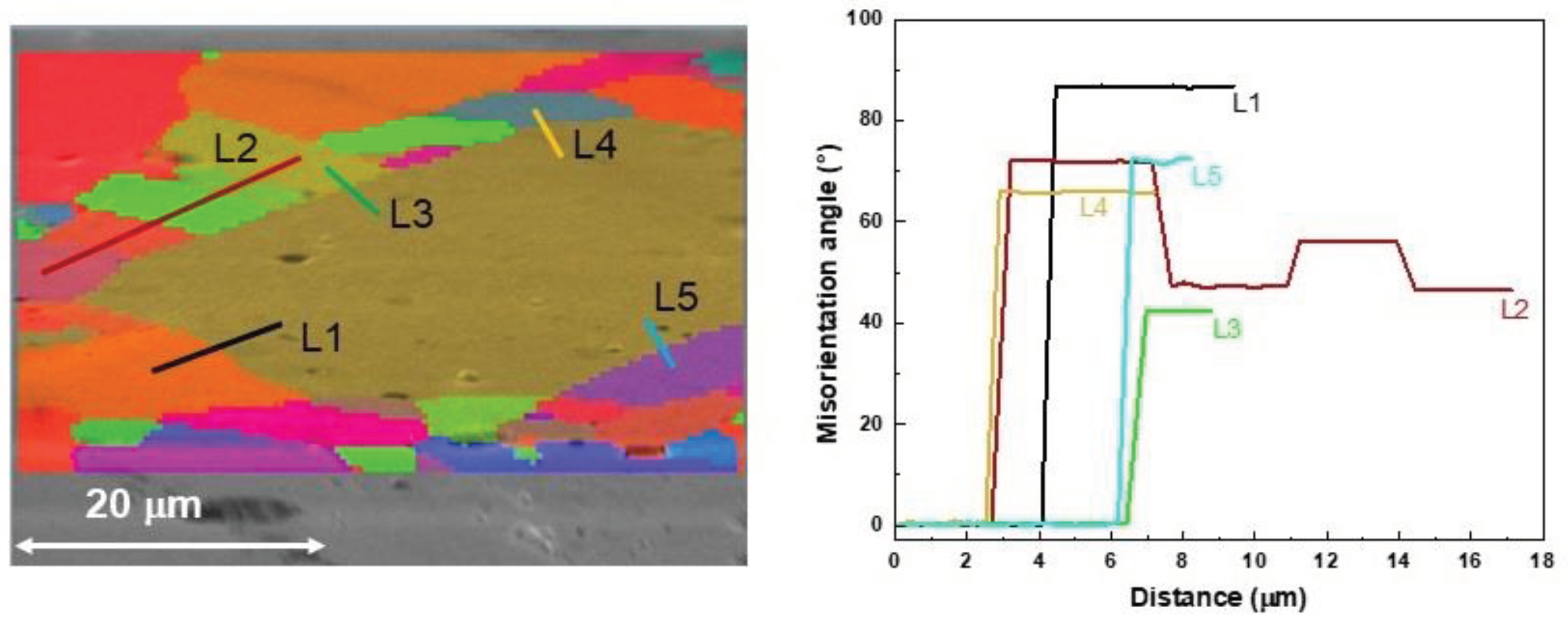

2. Samples Characterization

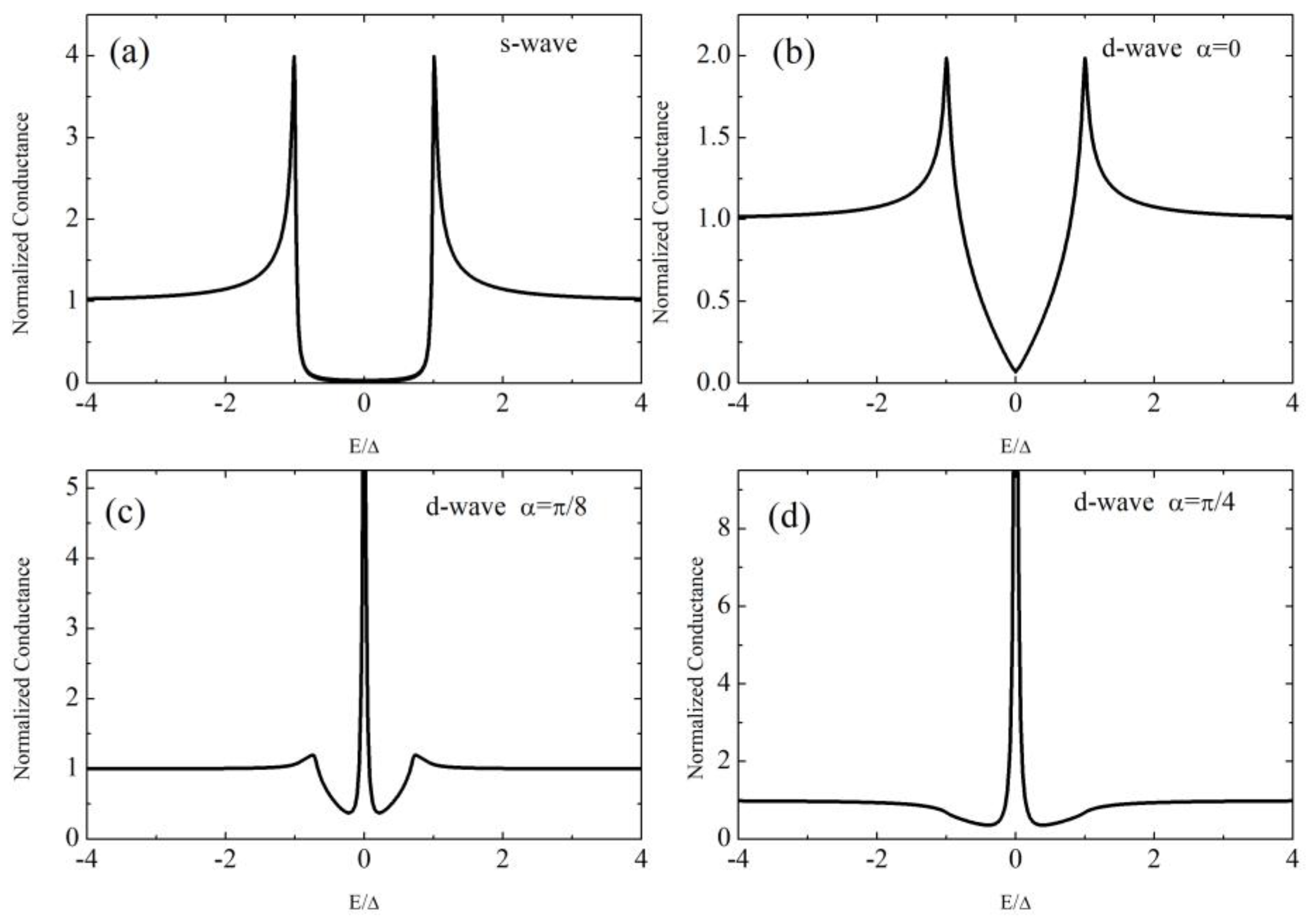

3. Theory

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

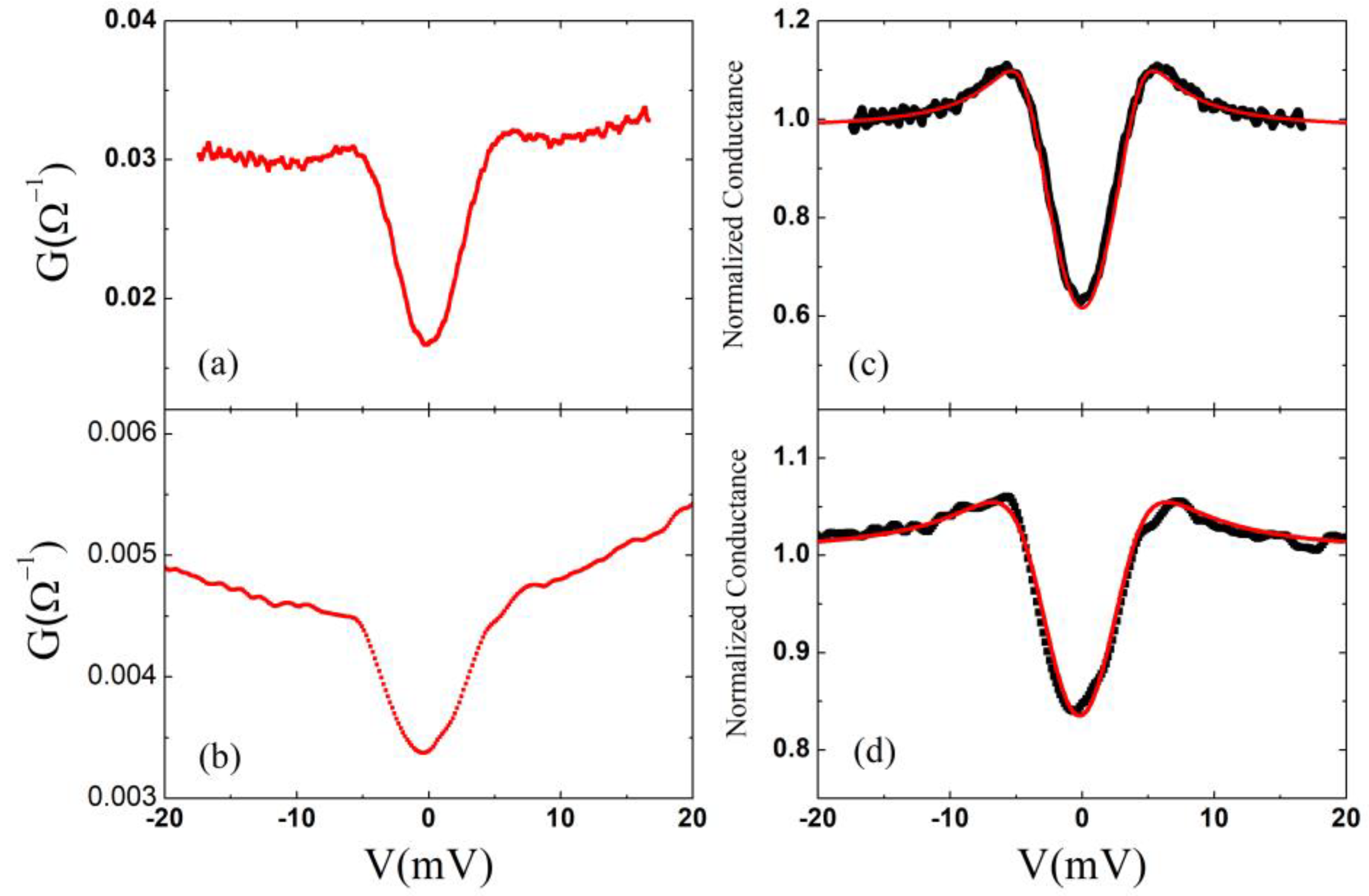

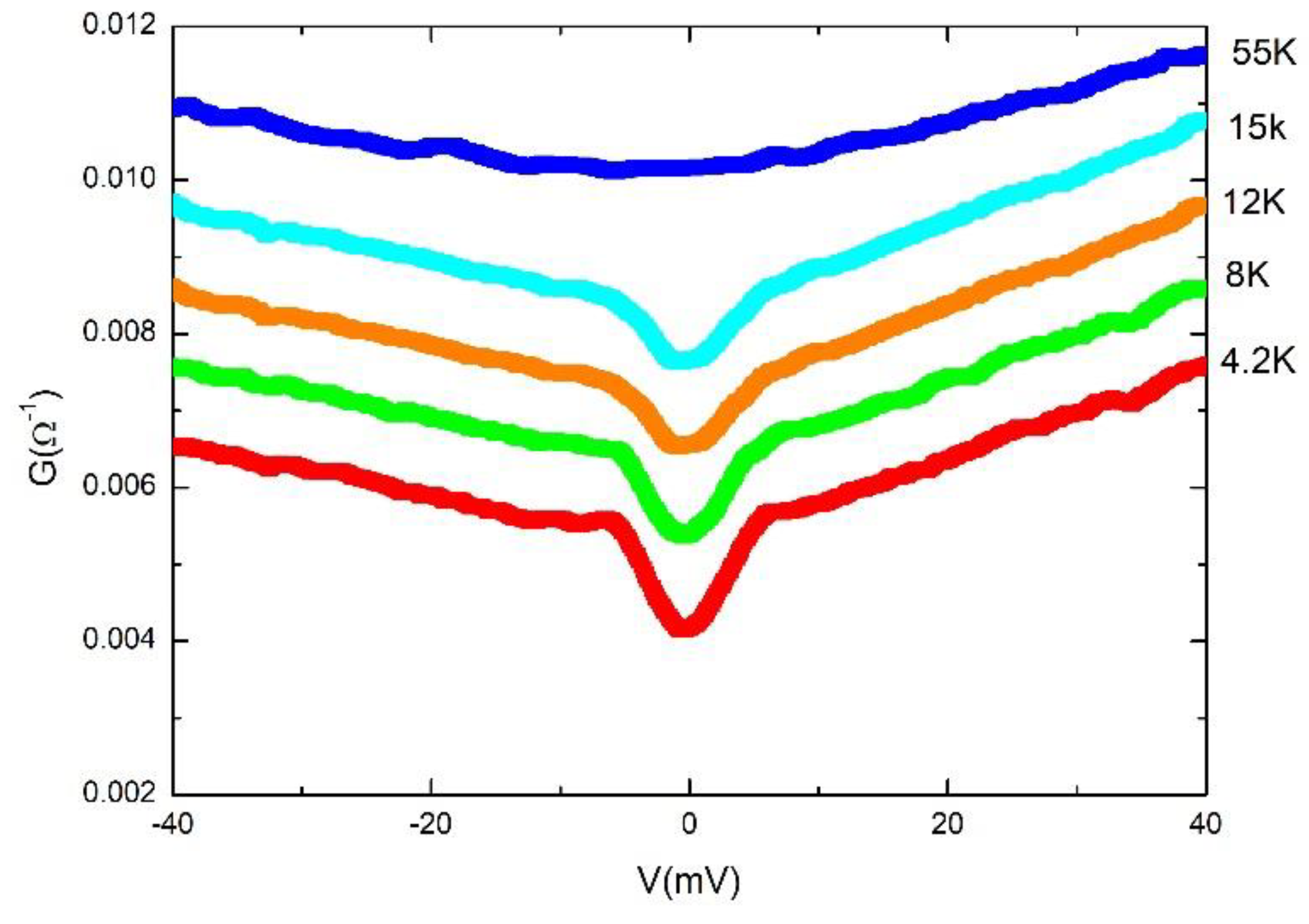

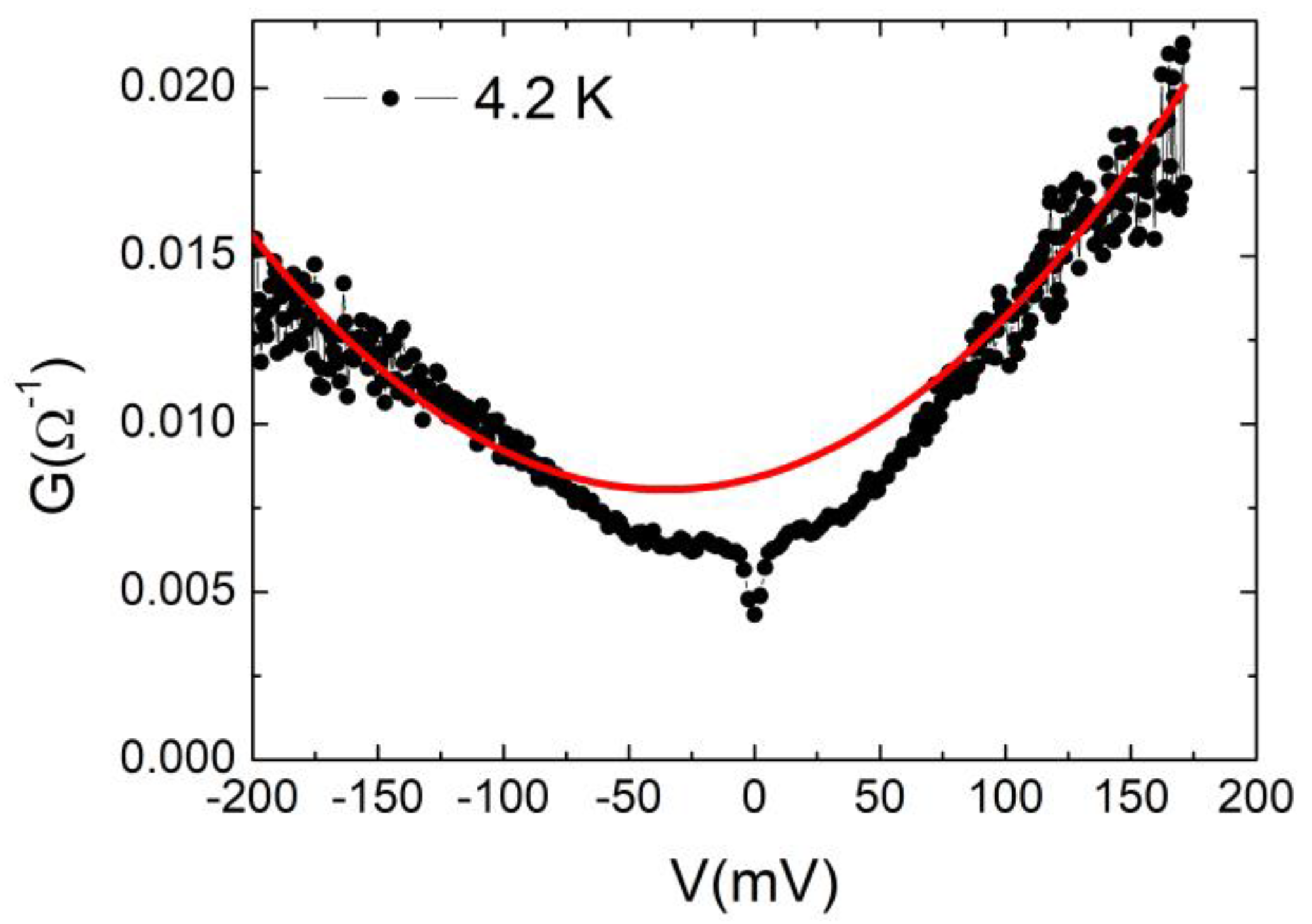

4.1. Low-Bias Conductance

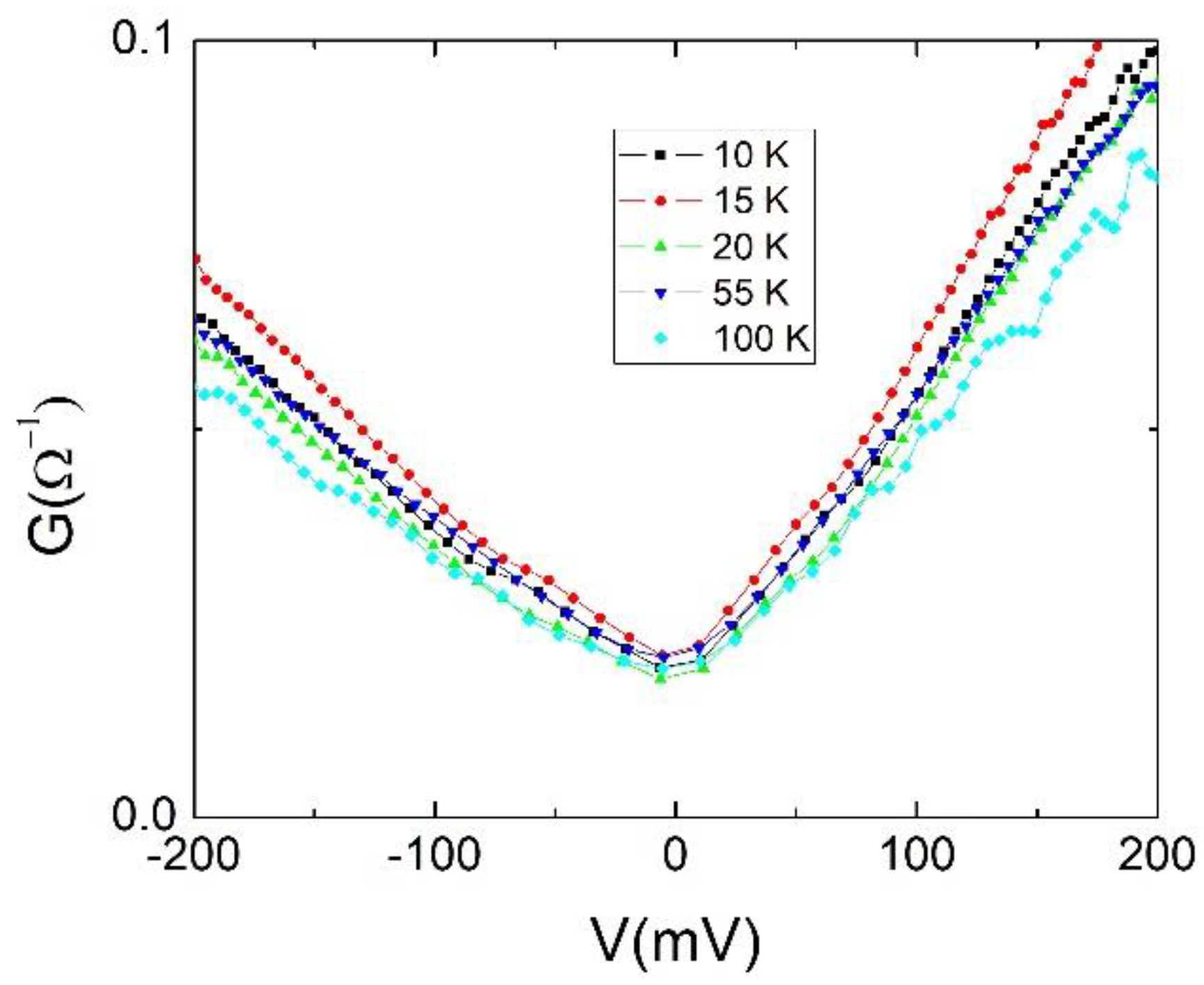

4.2. High-Bias Conductance

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, Qiang; Zasadzinski, J. F.; Gray, K. E. Phonon spectroscopy of superconducting Nb using point-contact tunneling. Phys. Rev. B 1990, 42, 7953. [CrossRef]

- DeWilde, Y., Miyakawa, N.; Guptasarma, P.; Iavarone, M.; Ozyuzer, L.; Zasadzinski, J. F.; Romano, P.; Hinks, D. G.; Kendziora, C.; Crabtree, G. W.; Gray, K. E. Unusual Strong-Coupling Effects in the Tunneling Spectroscopy of Optimally Doped and Overdoped Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 80, 153-156. [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Mu, G.; Fang, L.; Ren, C.; Wen, H-H. Point-contact spectroscopy of iron-based layered superconductor LaO0.9F0.1−δFeAs. Europhysics Letters 2008, 83, 57004. [CrossRef]

- Szabó, P.; Samuely, P.; Kačmarčík, J.; Klein, T.; Marcus, J.; Fruchart, D.; Miraglia, S.; Marcenat, C.; Jansen, A.G.M. Evidence for Two Superconducting Energy Gaps in MgB2 by Point-Contact Spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 87, 137005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giubileo, F.; Romeo, F.; Citro, R.; Di Bartolomeo, A.; Attanasio, C.; Cirillo, C.; Polcari, A.; Romano, P. Point contact Andreev reflection spectroscopy on ferromagnet/superconductor bilayers. Physica C: Superconductivity and its Applications, 2014, 503, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giubileo, F.; Romeo, F.; Di Bartolomeo, A.; Mizuguchi, Y.; Romano, P. Probing unconventional pairing in LaO0.5F0.5BiS2 layered superconductor by point contact spectroscopy. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 2018, 118, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E.L. Principles of Electron Tunneling Spectroscopy; 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2011.

- Fournier, P. T’ and infinite-layer electron-doped cuprates. Physica C 2015, 514, 314–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, N.P.; Fournier, P.; Greene, R.L. Progress and perspectives on electron-doped cuprates. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 2421–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Han, G.; Kyung, W.; Seo, J.; Cho, C.; Kim, B.S.; Arita, M.; Shimada, K.; Namatame, H.; Taniguchi, M.; Yoshida, Y.; Eisaki, H.; Park, S.R.; Kim, C. Electron Number-Based Phase Diagram of Pr1−xLaCexCuO4−δ and Possible Absence of Disparity between Electron- and Hole-Doped Cuprate Phase Diagrams. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 137001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, T.; Kartsovnik, M. V.; Proust, C.; Vignolle, B.; Putzke, C.; Kampert, E.; Sheikin, I.; Choi, E.-S.; Brooks, J. S.; Bittner, N.; Biberacher, W.; Erb, A.; Wosnitza, J.; Gross, R. Correlation between Fermi surface transformations and superconductivity in the electron-doped high-Tc superconductor Nd2−xCexCuO4. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 094501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, N.P.; Lu, D.H.; Feng, D.L.; Kim, C.; Damascelli, A.; Shen, K.M.; Ronning, F.; Shen, Z.-X.; Onose, Y.; Taguchi, Y.; Tokura, Y. Superconducting gap anisotropy in Nd1.85Ce0.15CuO4: results from photoemission. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86, 1126–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Kamiyama, T.; Takahashi, T.; Kurahashi, K.; Yamada, K. Observation of dx2-y2-like superconducting gap in an electron-doped high-temperature superconductor. Science 2001, 291, 1517–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, H.; Terashima, K.; Sato, T.; Takahashi, T.; Fujita, M.; Yamada, K. Direct observation of a nonmonotonic dx2-y2-wave superconducting gap in the electron-doped high-Tc superconductor Pr0:89LaCe0:11CuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 017003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Dai, P.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Ren, C.; Wen, H.H. Weak-coupling Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer superconductivity in the electron doped cuprate superconductors, Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 014526. [CrossRef]

- Kokales, J.D.; Fournier, P.; Mercaldo, L.V.; Talanov, V.V.; Greene, R.L.; Anlage, S.M. Microwave electrodynamics of electron-doped cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prozorov, R.; Giannetta, R.; Fournier, P.; Greene, R.L. Evidence for nodal quasiparticles in electron-doped cuprates from penetration depth measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snezhko, A.; Prozorov, R.; Lawrie, D.D.; Giannetta, R.; Gauthier, J.; Renaud, J.; Fournier, P. Nodal order parameter in electron-doped Pr2-xCexCuO4-d superconducting films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 92, 157005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, G.; Koitzsch, A.; Gozar, A.; Dennis, B.S.; Kendziora, C.A.; Fournier, P.; Greene, R.L. Nonmonotonic dx2_y2 superconducting order parameter in Nd2-xCexCuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 107002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuei, C.C.; Kirtley, J.R. Phase-sensitive evidence for d-wave pairing symmetry in electron-doped cuprate superconductors, Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesca, B.; Ehrhardt, K.; Mossle, M.; Straub, R.; Koelle, D.; Kleiner, R,; Tsukada, A. Magnetic-field dependence of the maximum supercurrent of La2-xCexCuO4-y interferometers: evidence for a predominant dx2-y2 superconducting order parameter. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 90, 057004. [CrossRef]

- Ariando, D.; Darminto, H.J.H.; Smilde, V.; Leca, D.H.A.; Blank, H.; Rogalla, H.; Hilgenkamp, H. Phase-sensitive order parameter symmetry test experiments utilizing Nd2-xCexCuO4-y/Nb zigzag junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 167001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, N.P.; Ronning, F.; Lu, D.H.; Kim, C.; Damascelli, A.; Shen, K.M.; Feng, D.L.; Eisaki, H.; Shen, Z.-X.; Mang, P.K.; Kaneko, N.; Greven, M.; Onose, Y.; Taguchi, Y.; Tokura, Y. Doping dependence of an n-type cuprate superconductor investigated by angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 257001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagan, Y., and Greene, R. L. Hole superconductivity in the electron-doped superconductor Pr2−xCexCuO4. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 024506. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Qingshan; Chen, Yan; Lee, T. K.; Ting, C. S. Fermi surface evolution in the antiferromagnetic state for the electron-doped t−t′−t′′−J model. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 69, 214523. [CrossRef]

- Luo H. G.; and Xiang; T. Superfluid Response in Electron-Doped Cuprate Superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 027001. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. S.; Luo, H. G.; Wu, W. C.; and Xiang, T. Two-band model of Raman scattering on electron-doped high-Tc superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 174517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Huang, Y.; Gao, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, S. L.; Dai, P. C.; Zhou, F.; Xiong, J. W.; Ti, W. X.; and Wen, H. H. Distinct pairing symmetries in Nd1.85Ce0.15CuO4−y and La1.89Sr0.11CuO4 single crystals: Evidence from comparative tunneling measurements. Phys. Rev. B, 2005, 72, 144506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tabis, W.; Tang, Y.; Yu, G.; Jaroszynski, J.; Barišić, N.; and Greven, M. Hole pocket-driven superconductivity and its universal features in the electron-doped cuprates. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaap7349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch J., and Marsiglio, F. Understanding electron-doped cuprate superconductors as hole superconductors. Physica C 2019, 564, 29. [CrossRef]

- Qazilbash, M. M.; Koitzsch, A.; Dennis, B. S.; Gozar, A.; Balci, Hamza; Kendziora, C. A.; Greene, R. L.; Blumberg, G. Evolution of superconductivity in electron-doped cuprates: Magneto-Raman spectroscopy. Phy.Rev.B. 2005, 72, 214510. [CrossRef]

- Armitage N. P. et al. Anomalous Electronic Structure and Pseudogap Effects in Nd1.85Ce0.15CuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 87, 147003. [CrossRef]

- Yamashiro, M.; Tanaka, Y.; Tanuma, Y.; Kashiwaya, S. Theory of tunneling conductance for normal metal/insulator/triplet superconductor junction. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1998, 67, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourachkine, A. Andreev reflections and tunneling spectroscopy on underdoped Nd1.85Ce0.15CuO4–δ. Europhys. Lett. 2000, 50, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, Amlan; Fournier, P.; Qazilbash, M. M.; Smolyaninova, V. N.; Balci, Hamza; Greene, R. L. Evidence of a d- to s-Wave Pairing Symmetry Transition in the Electron-Doped Cuprate Superconductor Pr2−xCexCuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 207004. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.S. and Wu, W.C. Theory of point-contact spectroscopy in electron-doped cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 220504. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-S.; Skinta, J.A.; Lemberger, T.R.; Tsukada, A.; Naito, M. Evidence for a Transition in the Pairing Symmetry of the Electron-Doped Cuprates La2−xCexCuO4−y and Pr2−xCexCuO4−y. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 087001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinta, J.A.; Kim, M.-S.; Lemberger, T.R.; Greibe, T.; Naito, M. Evidence for a Transition in the Pairing Symmetry of the Electron-Doped Cuprates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 207005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmers, A.; Lobo, R. P. S. M.; Bontemps, N.; Homes, C. C.; Barr, M. C.; Dagan, Y.; Greene, R. L. Infrared signature of the superconducting state in Pr2−xCexCuO4. Phys. Rev.B 2004, 70, 132502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucolo, A. M.; Di Leo, R.; Nigro, A.; Romano, P.; and Bobba, F. Linear normal conductance in copper oxide tunnel junctions. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, R9686–R9688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, M.; Krockenberger, Y.; Ikeda, A.; Yamamoto, H. Reassessment of the electronic state, magnetism, and superconductivity in high-Tc cuprates with the Nd2CuO4 structure. Physica C 2016, 523, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radaelli, P. G.; Jorgensen, J. D.; Schultz, A. J.; Peng, J. L.; Greene, R. L. Evidence of apical oxygen in Nd2CuOy determined by single-crystal neutron diffraction. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 49, 15322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mang, P. K.; Larochelle, S.; Mehta, A.; Vajk, O. P.; Erickson, A. S.; Lu, L.; Buyers, W. J. L.; Marshall, A. F.; Prokes, K.; Greven, M. Phase decomposition and chemical inhomogeneity in Nd2−xCexCuO4±δ. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 70, 094507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. Q.; Mao, S. N.; Jiang, W.; Peng, J. L.; Greene, R. L. Oxygen dependence of the transport properties of Nd1.78Ce0.22CuO4±δ. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 53, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J. S.; Dagan, Y.; Barr, M. C.; Weaver, B. D.; Greene, R. L. Role of oxygen in the electron-doped superconducting cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 104510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riou, G.; Richard, P.; Jandl, S.; Poirier, M.; Fournier, P.; Nekvasil, V.; Barilo, S. N.; Kurnevich, L. A. Pr3+ crystal-field excitation study of apical oxygen and reduction processes in Pr2−xCexCuO4±δ. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 69, 024511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, P.; Riou, G.; Hetel, I.; Jandl, S.; Poirier, M.; Fournier, P. Role of oxygen nonstoichiometry and the reduction process on the local structure of Nd2−xCexCuO4±δ. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 70, 064513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. J.; Dai, P.; Campbell, B. J.; Chupas, P. J.; Rosenkranz, S.; Lee, P. L.; Huang, Q.; Li, S.; Komiya, S.; Ando, Y. Microscopic annealing process and its impact on superconductivity in T’-structure electron-doped copper oxides. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, P.; Riccio, M.; Guarino, A.; Martucciello, N.; Grimaldi, G.; Leo, A.; Nigro, A. Electron doped superconducting cuprates for photon detectors. Measurement 2018, 122, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, A.; Autieri, C.; Marra, P.; Leo, A.; Grimaldi, G.; Avella, A.; and Nigro, A. Superconductivity induced by structural reorganization in the electron-doped cuprate Nd2−xCexCuO4. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 014512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, A.; Fittipaldi, R.; Romano, A.; Vecchione, A.; Nigro, A. Correlation between structural and transport properties in epitaxial films of Nd2−xCexCuO4±δ. Thin Solid Films 2012, 524, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, A.; Leo, A.; Avella, A.; Avitabile, F.; Martucciello, N.; Grimaldi, G.; Romano, A.; Pace, S.; Romano, P.; Nigro, A. Electrical transport properties of sputtered Nd2−xCexCuO4±δ thin films. Physica B 2018, 536, 742–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, A.; Patimo, G.; Vecchione, A.; Di Luccio, T.; Nigro, A. Fabrication of superconducting Nd2−xCexCuO4±δ films by automated dc sputtering technique. Physica C 2013, 495, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, A.; Leo, A.; Grimaldi, G.; Martucciello, N.; Dean, C.; Kunchur, M. N.; Pace, S.; Nigro, A. Pinning mechanism in electron-doped HTS Nd1.85Ce0.15CuO4−δ epitaxial films. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2014, 27, 124011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avella, A.; Buonavolontà, C.; Guarino, A.; Valentino, M.; Leo, A.; Grimaldi, G.; de Lisio, C.; Nigro, A.; Pepe, G. Disorder-sensitive pump-probe measurements on Nd1.83Ce0.17CuO4±δ films. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 115426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, A.; Romano, P.; Avitabile, F.; Leo, A.; Martucciello, N.; Grimaldi, G.; Ubaldini, A.; D’Agostino, D.; Bobba, F.; Vecchione, A.; Pace, S.; Nigro, A. Characterization of Nd2−xCexCuO4±δ (x = 0 and 0.15) Ultrathin Films Grown by DC Sputtering Technique. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2017, 27, 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Uthayakumar, S.; Fittipaldi, R.; Guarino, A.; Vecchione, A.; Romano, A.; Nigro, A.; Habermeier, H.-U.; Pace, S. Thermal treatments and evolution of bulk Nd1.85Ce0.15CuO4 morphology, Physica C 2008, 468, 2271-2274. [CrossRef]

- Andreev, A.F. The Thermal Conductivity of the Intermediate State in Superconductors. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 1964, 19, 1228. [Google Scholar]

- Deutscher, G. Andreev–Saint-James reflections: A probe of cuprate superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2005, 77, 109–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J.; Cooper, L. N.; and Schrieffer, J. R. Theory of Superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 1957, 108, 1175–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonder, G.E.; Tinkham, M.; Klapwijk, T.M. Transition from metallic to tunneling regimes in superconducting microconstrictions: Excess current, charge imbalance, and supercurrent conversion. Phys. Rev. B 1982, 25, 4515–4532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fano, U. Effects of Configuration Interaction on Intensities and Phase Shifts. PhysRev. 1961, 124, 1866–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zasadzinski, J.; Tralshawala, N. et al. Tunnelling evidence for predominantly electron–phonon coupling in superconducting Ba1−xKxBiO3 and Nd2−xCexCuO4−y. Nature 1990, 347, 369–372. [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, G.; Koitzsch, A.; Gozar, A.; Dennis, B. S.; Kendziora, C. A.; Fournier, P.; Greene, R. L. Nonmonotonic dx2−y2 Superconducting Order Parameter in Nd2−xCexCuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 107002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwaya, S.; Matsubara, N.; Prijamboedi, B. et al. Doping Dependence of Superconducting Energy Gap of NCCO Observed by Tunnelling Spectroscopy. J. Low Temp. Phys. 2003, 131, 327–330. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Perdew, J.P. Spin scaling of the electron-gas correlation energy in the high-density limit. Phys.Rev.B 1991, 43, 8911–8916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onose, Y.; Taguchi, Y.; Ishizaka, K.; Tokura, Y. Charge dynamics in underdoped Nd2−xCexCuO4: Pseudogap and related phenomena. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 69, 024504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.A.; Ramakrishnan, T. V. Disordered electronic systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1985, 57, 287–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duif, A.M.; Jansen, A.G.M.; Wyder, P. Point-contact spectroscopy. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 1989, 1, 3157–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dynes, R. C.; Narayanamurti, V.; Garno, J. P. Direct Measurement of Quasiparticle-Lifetime Broadening in a Strong-Coupled Superconductor. Phys.Rev.Lett. 1978, 41, 1509–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleceník, A.; Grajcar, M.; Beňačka, Š.; Seidel, P.; Pfuch, A. Finite-quasiparticle-lifetime effects in the differential conductance of Bi2Sr2CaCu2Oy/Au junctions. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 49, 10016–10019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Huang, Y.; Ren, C.; Wen, H. H. Vortex overlapping in a BCS type-II superconductor revealed by Andreev reflection spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 134508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagan, Y.; Qazilbash, M. M.; Greene, R. L. Tunneling into the Normal State of Pr2−xCexCuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 187003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagan, Y.; Beck, R.; Greene, R. L. Dirty Superconductivity in the Electron-Doped Cuprate Pr2−xCexCuO4−δ: Tunneling Study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99, 147004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, H.; Terashima, K.; Sato, T.; Takahashi, T.; Fujita, M.; Yamada, K. Direct Observation of a Nonmonotonic dx2−y2-Wave Superconducting Gap in the Electron-Doped High-Tc Superconductor Pr0.89LaCe0.11CuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 017003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. S. and Wu, W. C. Theory of point-contact spectroscopy in electron-doped cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 220504. [CrossRef]

- Simmons, J.G. Electric Tunnel Effect between Dissimilar Electrodes Separated by a Thin Insulating Film. J.Appl.Phys. 1963, 34, 2581–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkman, W. F.; Dynes, R. C.; Rowell, J. M. Tunneling Conductance of Asymmetrical Barriers. J. Appl. Phys. 1970, 41, 1915–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, A.; Romano, P.; Fujii, J.; Ruosi, A.; Avitabile, F.; Vobornik, I.; Panaccione, G.; Vecchione, A.; Nigro, A. Study of the surface properties of NCCO electron-doped cuprate. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2019, 228, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrus, D.; Forro, L.; Koller, D.; Mihaly, L. Giant tunnelling anisotropy in the high- Tc superconductor Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8. Nature 1991, 351, 460–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirtley, J. R.; Washburn, S.; Scalapino, D. J. Origin of the linear tunneling conductance background. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 45, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).