1. Introduction

Intercellular junctions of epithelial and endothelial cells are specializations of the cell membrane that physically integrate individual cells into tissues. These junctions consist of distinct substructures visible by ultrastructural analysis, such as tight junctions (TJs), adherens junctions (AJs) or desmosomes, with different functions at the level of the individual cell, of the organ and of the entire organism, which for example include apical-basal polarity, barrier formation, resistance to mechanical strain and propagation of mechanical forces, and morphogenesis [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The integrity of these junctions is necessary for the maintenance of functional tissues. Abnormalities in the organization or function of the junctions are frequently associated with disorders like inflammation and malignant transformation [

6,

7,

8]. Consistent with the necessity to develop adhesive systems as a prerequisite for the development of multicellular organisms, the invention of proteins mediating cell-cell adhesion dates back to the closest extant unicellular relative of multicellular organisms [

9,

10].

All three types of junctions are composed of several multiprotein complexes. These complexes consist of at least one integral membrane protein that interacts with a cytoplasmic protein which together with other scaffolding proteins forms a junctional plaque that is linked to the actin cytoskeleton, the intermediate filament system or the microtubule system [

11,

12,

13]. In addition to their role in connecting the cellular filamental systems to the cell-cell junctions, all three types of cell junctions serve as hubs for signaling events that regulate proliferation, differentiation, or cell migration [

14,

15,

16]. The integral membrane proteins localized at the different types of junctions thus not only physically link adjacent cells to form a structural continuum of epithelial cells, but also regulate the specific localization of signaling hubs along the intercellular junctions. Interestingly, the most diverse repertoire of adhesion molecules and integral membrane proteins is localized at the TJs. As opposed to AJs and desmosomes, which use cadherins and members of the nectin family of the immunoglobulin superfamily (IgSF) to interact with adjacent cells, TJs make use of various members of the IgSF, members of the claudin family, members of the TJ-associated Marvel protein (TAMP) family, and members of the Crumbs family of integral membrane proteins to regulate their function. In this review article, we provide a brief overview on the emerging new functions of TJ-associated integral membrane proteins. The interested reader is referred to comprehensive recent reviews on the structural organization of TJs and the functional roles of integral membrane proteins in TJ formation [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

2. Integral membrane proteins at the TJs

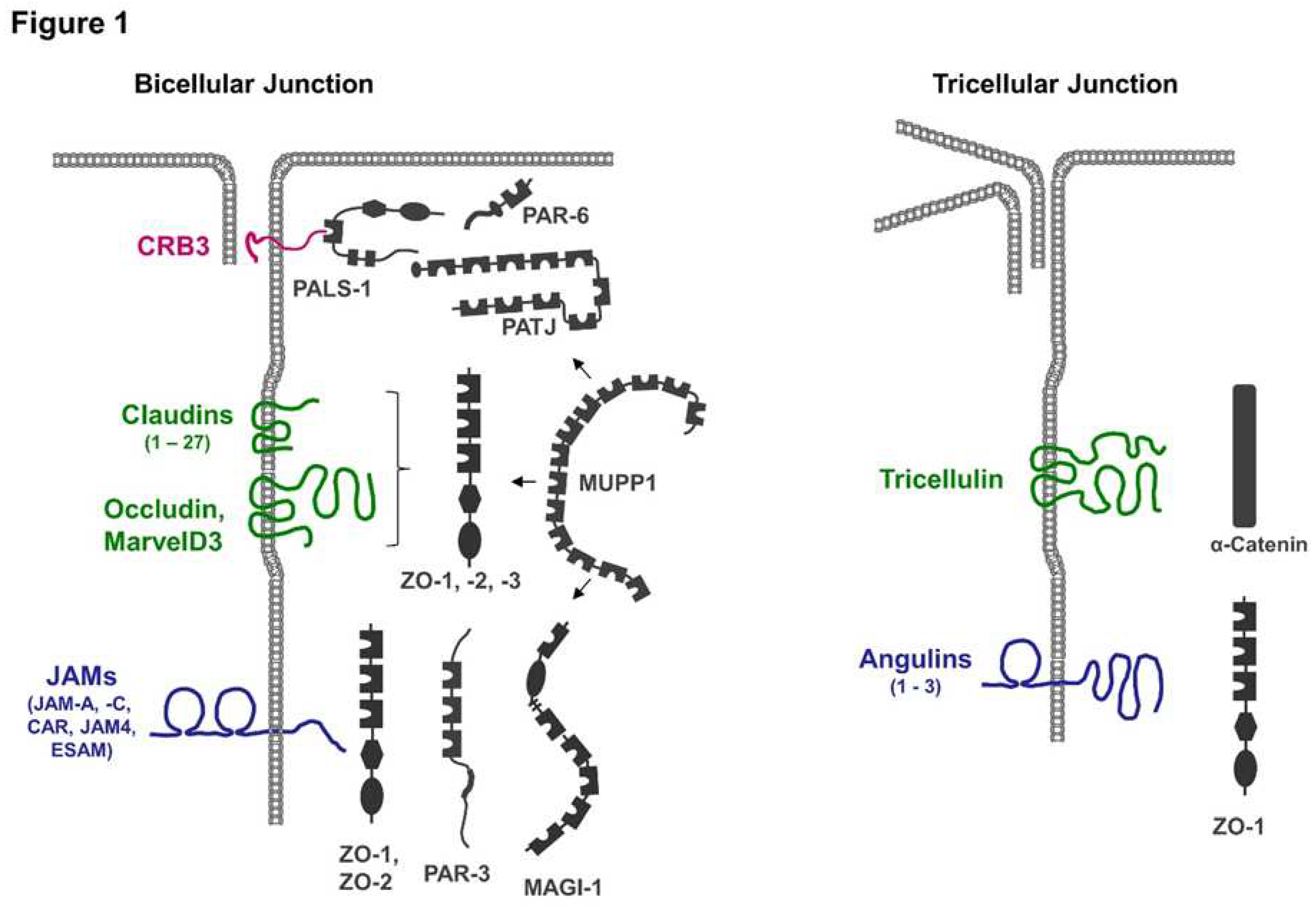

Integral membrane proteins localized at the TJs can be classified into four major groups. Crumbs homolog 3 (CRB3), a member of the Crumbs family of proteins, claudins, TAMPs, and members of the IgSF of adhesion molecules (

Figure 1).

2.1. CRB3 is a member of the vertebrate Crumbs family of proteins which are homologous to Drosophila Crumbs. CRB3 and has a very short extracellular region that consists of 33 amino acids (AA), a single transmembrane region and a short cytoplasmic region of 40 AA [

23]. In addition to its localization at the TJs CRB3 is also localized at the apical membrane domain of epithelial cells [

24]. As opposed to Drosophila Crumbs the vertebrate CRB3 isoform localized at the TJs is most likely not involved in homophilic or heterophilic interactions [

25].

2.2. Claudins are a family of tetraspan transmembrane proteins comprising 27 members [

26,

27]. Notably, claudins support cell aggregation when expressed in fibroblasts, indicating that their adhesive activity not only regulates their localization at homotypic cell-cell contacts but also contributes to the physical cell-cell adhesion at the TJs [

28]. A central property of claudins is their ability to multimerize by interacting both in cis and in trans with either the same or a different claudin family member to form strands that are visible by freeze-fracture electron microscopy (EM) [

29,

30]. Claudin-based strands can act as occluding barriers for water and small solutes as well as anion- or cation-selective paracellular channels and are the principal paracellular permeability regulators of epithelial and endothelial barriers [

31].

2.3. Members of the TAMP family include occludin, tricellulin/MarvelD2 and MarvelD3 [

32]. Similar to claudins, TAMPs are tetraspan transmembrane proteins, but based on sequence homologies,they are not related to claudins. Their characteristic feature is a conserved four-transmembrane “MAL and related proteins for vesicle trafficking and membrane link” (Marvel) domain [

33]. Among the three TAMPs tricellulin is unique as it is enriched at sites of contact between three cells (tricellular TJs, tTJs) [

34]. Heterotypic interactions between tricellulin and MarvelD3 as well as between occludin and MarvelD3 have been described by co-immunoprecipitation (CoIP) and by Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) experiments. These interactions most likely occur in cis [

32,

35]. A homophilic interaction in trans has been found for occludin but not for tricellulin or MarvelD3 [

35,

36]. While several studies suggested that TAMPs per se are not essential for the development of an epithelial barrier function [

37,

38,

39], recent findings indicate that tricellulin is required for the establishment of the barrier function in mammary gland-derived epithelial cells [

40].

2.4. IgSF members localized at the TJs include the junctional adhesion molecule (JAM) family members JAM-A and JAM-C [

41] and the JAM-related adhesion molecules Coxsackie- and Adenovirus-Receptor (CAR), JAM4, CAR-like membrane protein (CLMP) and Endothelial Cell-Selective Adhesion Molecule (ESAM, in endothelial cells) [

42,

43,

44,

45]. All these IgSF proteins can undergo trans-homophilic interactions which stabilizes their localization at cell-cell contacts. In addition, the trans-homophilic activities of CAR, JAM4, CLMP and ESAM support cell aggregation after transfection in cells [

42,

43,

44,

46] suggesting that their adhesive activities contribute to the strength of the physical interaction at the TJs. Angulins (Angulin-1, -2, -3) are IgSF proteins with a single N-terminal Ig-like domain [

47]. Among all other IgSF proteins localized at the TJs, angulins are unique in that they are enriched at the tTJs [

48]. A main function of all three angulins is to recruit tricellulin to the tTJs [

48,

49]. Ectopic expression of angulin-1 in L cell fibroblasts resulted in angulin-1 enrichment at cell-cell contacts suggesting that angulin-1 is engaged in homophilic or heterophilic trans interactions [

49].

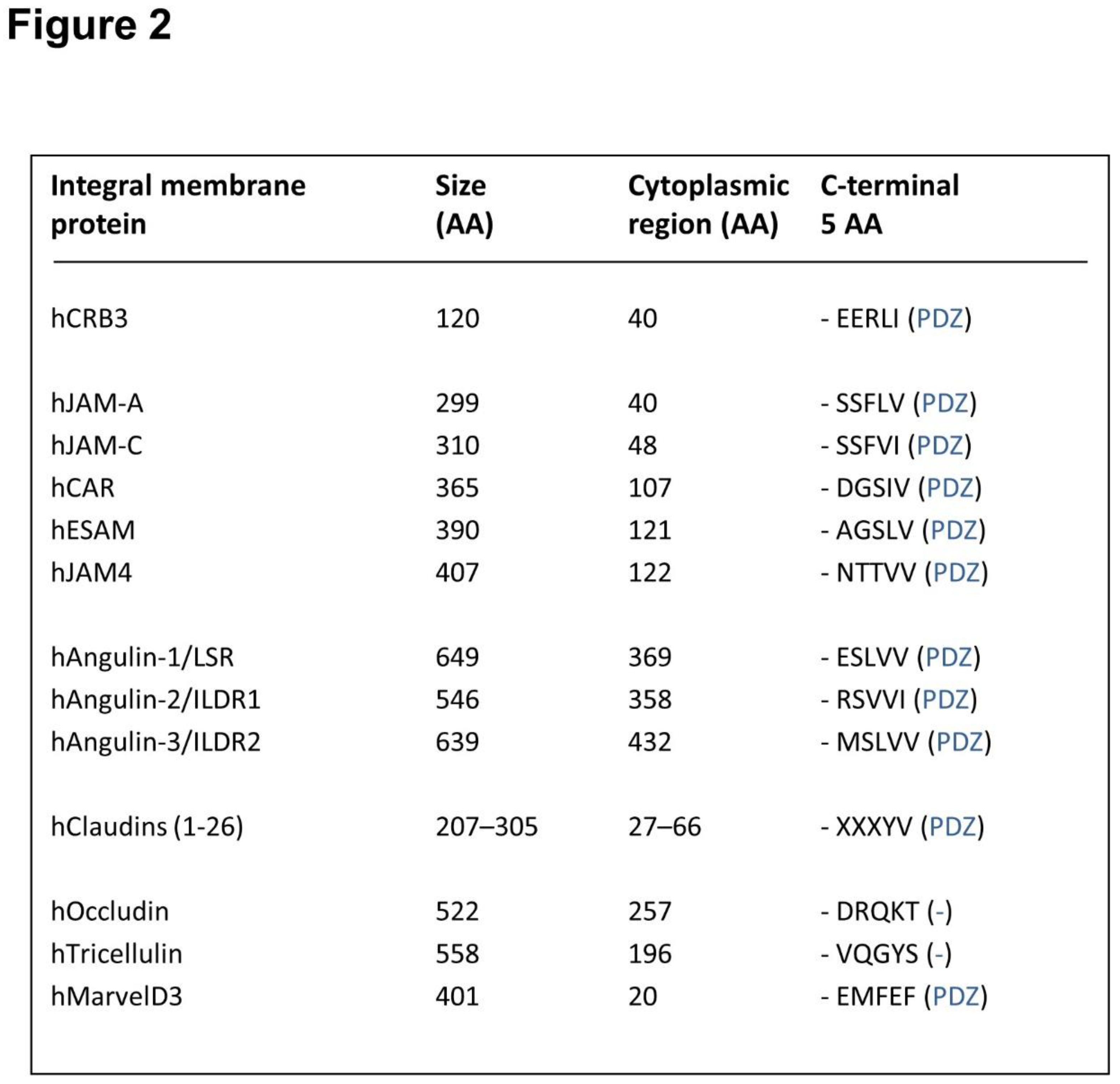

Strikingly, many of the integral membrane proteins localized at the TJs contain a C-terminal PDZ domain-binding motif (PBM) through which they can interact with PDZ domains present in many TJ-localized scaffolding proteins (

Figure 2). The presence of multiple PDZ domains in many scaffolding proteins localized at the TJs (

Figure 1) combined with the promiscuity of PDZ domains in ligand binding allows for the incorporation of several integral membrane proteins in a single scaffolding protein-organized complex. Vice versa, individual membrane proteins can recruit and assemble distinct protein complexes at the TJ. These biochemical properties may in part explain the high complexity and dynamics of protein complexes at the TJs [

24].

3. Integral membrane proteins and the paracellular barrier function of TJs

A central function of TJs is the establishment of a selective paracellular barrier to the free diffusion of water and solutes. This function is mainly accomplished by claudins [

26]. Claudins are the molecular basis for TJ strands and the determinants of the pore permeability pathway of TJs, which is characterized by a size and charge selective permeability for molecules with a hydrodynamic radius of approximately 4 - 6 Å [

50,

51]. The expression of a specific set of claudins enables the formation of ion-selective or barrier-forming channels, which provides a mechanism of adaptation to the needs of a given tissue in the organism [

22,

52].

However, the model of the claudin-based regulation of the paracellular permeability only accounts for the pore permeability pathway. The second major permeability pathway regulated by TJs, the leak pathway which is not charge selective and which allows a limited flux of large molecules with a hydrodynamic radius of up to approximately 120 Å [

50,

51], is not dependent on claudins. MDCK cells lacking all claudins still develop close membrane appositions and form a barrier to 150 kDa FITC-dextran molecules which have a radius of approximately 90 Å [

53]. This barrier is lost upon additional depletion of JAM-A. Interestingly, close membrane appositions observed in the absence of claudins are strongly reduced albeit not completely absent in MDCK cells lacking claudins and JAM-A, suggesting that JAM-A clustering as a result of trans-homophilic interactions [

54] forms a barrier to the diffusion of macromolecules. In line with this assumption, ectopic expression of JAM-A in CHO cells, which express neither claudins nor JAM-A and which lack TJ strands, results in an increased barrier for 40 kDa FITC-dextran (hydrodynamic radius approximately 66 Å) [

55].

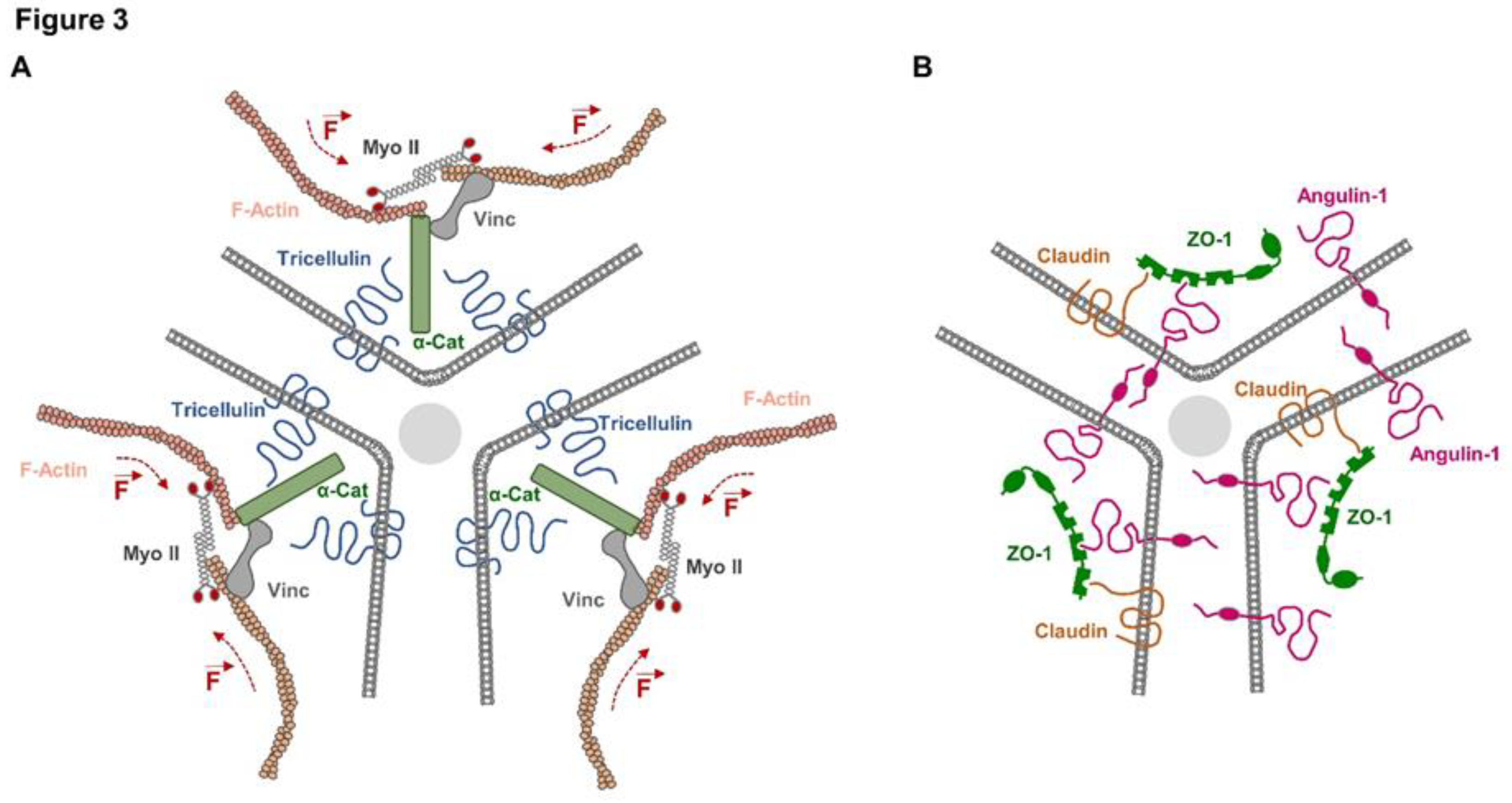

The development of barrier-forming epithelial monolayers requires the formation of a continuous TJ strand network that seals the entire epithelium. The sealing of cell vertices, the common points of three or more neighboring cells, imposes a challenge to this necessity. Early studies using freeze-fracture EM showed that at sites of tTJs the paired strands of two neighboring cells develop vertical extensions, so-called central sealing elements, which are cross-bridged with the central sealing elements of the two other bicellular contact sites to form a central tube [

56,

57]. Tricellulin has been identified as a structural and functional component of tTJs [

34] (

Figure 3). Tricellulin is enriched at tTJs, and its depletion results in discontinuities of the TJ strand network along bicellular TJs (bTJs) and in a loss of the epithelial barrier function [

34], strongly suggesting that tricellulin links the bTJ strand network to the tTJs to warrant continuity of the network at the interfaces of bTJs and tTJs. While this model could not explain how cells prevent leakage of solutes through the central tube that is lined by the three central sealing elements in the center of a tTJ (

Figure 3), new evidence provides a possible explanation. Tricellulin is linked to the actomyosin network via α-catenin and vinculin [

40], two adapter proteins known to link cadherins with the actin cytoskeleton at AJs. Through its interaction with α-catenin and vinculin, tricellulin recruits actin filaments to the central sealing elements present at the tTJs. The myosin II motor-driven contraction of antiparallel actin filaments associated with tricellulin generates a close apposition of the central sealing elements originating from the three cells to minimize the intercellular space at tTJs [

40].

Interestingly, the function of tricellulin is closely linked to the functional activity of angulin-1. As mentioned before, angulin-1 is localized specifically at tTJs [

49]. Depletion of angulin-1 phenocopies depletion of tricellulin, with discontinuities of occludin localization at bTJs, widening of the intercellular space at tTJs, and impaired paracellular barrier formation [

40,

49]. While depletion of angulin-1 results in a loss of tricellulin from tTJs, angulin-1 retains its specific localization at TJs after depletion of tricellulin [

40,

49], indicating that one major function of angulin-1 is the recruitment of tricellulin to tTJs. Angulin-1 has functions that go beyond the mere recruitment of tricellulin to tTJs. Angulin-1 recruits ZO-1 and, via ZO-1, claudin-2 to the more basal region underneath the typical TJs at tricellular contacts, which most likely represent the central sealing elements formed by vertical TJ strands [

39]. In addition, Angulin-1 is responsible for the close membrane apposition of the three cells at tricellular contact sites, and, surprisingly, not only at the level of the tTJs but also at the level of the desmosomes [

39]. This function of angulin-1 is independent of JAM-A or claudins. Interestingly, in MDCKII cells used in this study by Sugawara and colleagues [

39], tricellulin appears to be required for the connection of TJ strands to the central sealing elements but not for the barrier for 332 Da fluorescein, which suggests that the function of angulin-1 in forming a barrier for small uncharged solutes is independent of tricellulin. Together with the observation in mammary gland-derived Eph4 cells [

40], these observations also indicate that the specific contribution of a given integral membrane protein to the barrier function might depend on the given tissue.

4. Integral membrane proteins and mechanical force load on TJs

Epithelia are exposed to mechanical forces that originate both form external sources (extrinsic forces) but also from epithelial cells themselves when sites of adhesion are coupled to the contractile actomyosin cytoskeleton (intrinsic forces) [

58,

59]. During the last decade, the mechanisms through which forces are sensed and propagated between cells have been extensively characterized resulting in the concept that cell-cell adhesion receptors connected to the actomyosin cytoskeleton through adapter proteins link cells and thus can generate tissue-scale tension. In addition, through tension-dependent conformational changes of adapter proteins, alterations in mechanical forces can be sensed and translated into intracellular signaling pathways [

4,

58,

60]. While this concept has been elaborated in detail for AJs [

61], the sensing of tensile forces and their transduction at the TJs is now beginning to be understood in more detail [

62].

As part of the apical junctional complex, TJs are frequently subjected to mechanical challenges evoked by cell shape changes as they occur during cell extrusion or cytokinesis, as well as those generated during morphogenetic movements. Resisting these mechanical forces is in particular challenging as breaches in TJ strands could impair the barrier function [

63], possibly resulting in a loss of the organ-specific absorptive function of the epithelium or in inflammation. The recent observations that ZO-1 and ZO-2 undergo actomyosin-dependent conformational changes and that ZO-1 is under tensile stress have provided the first direct evidence that mechanisms of force-sensing and -translation analogous to those described in AJs operate at the TJs [

64,

65]. When connected to the actomyosin cytoskeleton both ZO-1 and ZO-2 adopt an open conformation that exposes a region of approx. 400 AA required for the binding of occludin and the transcription factor DNA-binding protein A (DbpA) [

64]. This open conformation is required to recruit occludin and DbpA to cell-cell junctions and to mediate occludin- and DbpA-dependent functions [

64]. Recent findings further confirmed that several functions of ZO-1 in polarized epithelial cells, including junction formation and cell morphology, are dependent on actomyosin-mediated forces, and that ZO-1, surprisingly, also regulates tension on AJs and traction forces on the growth substrate, indicating a mutual regulation of cytoskeletal tension and ZO-1 function [

66,

67].

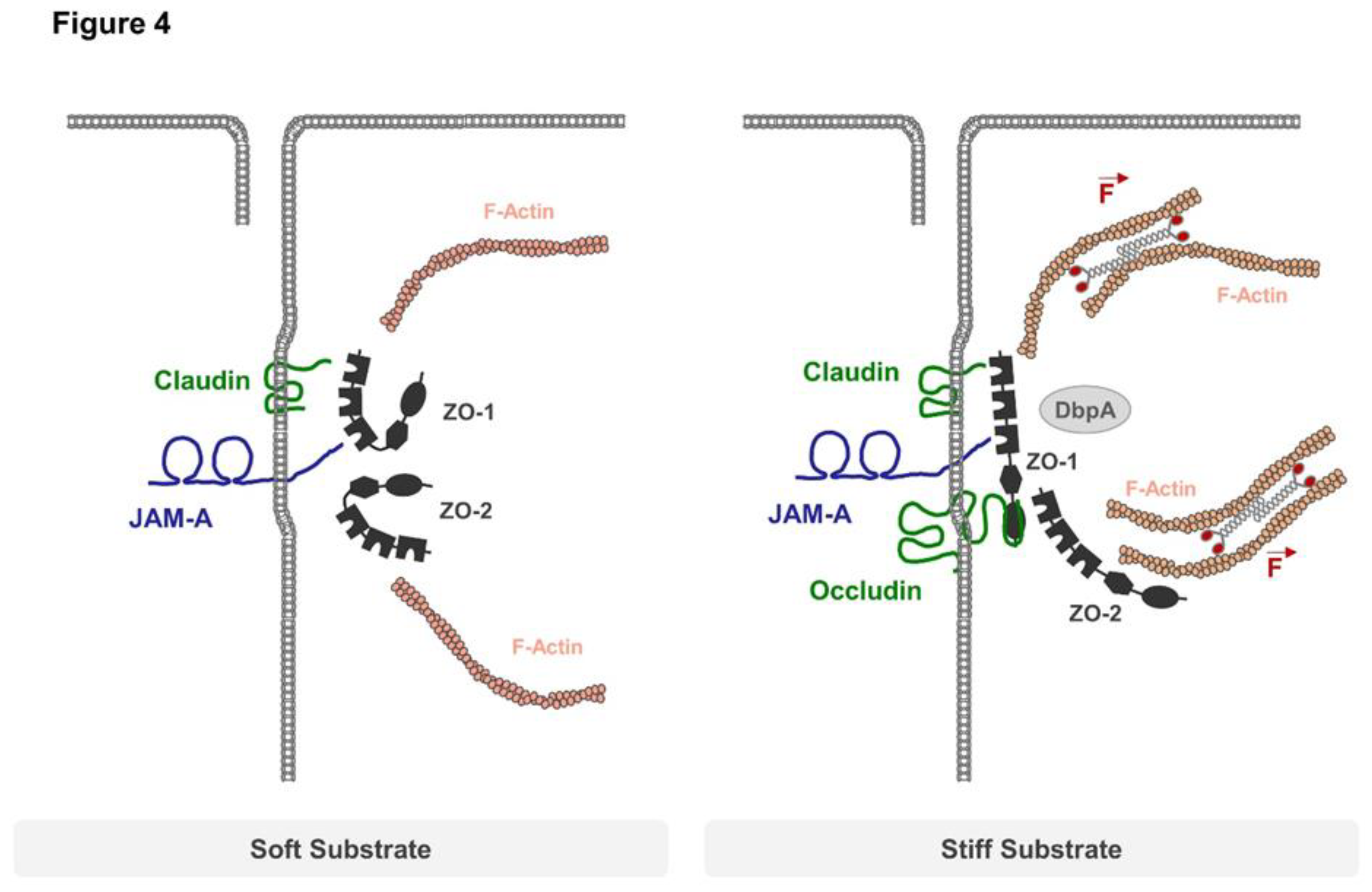

Interestingly, the tensile stress acting on ZO-1 is regulated by JAM-A. JAM-A directly interacts with PDZ3 of ZO-1 [

68,

69,

70] and, thus, exists in a common complex with ZO-1 and also ZO-2 [

71] (

Figure 4). Similar to depletion of ZO-1, depletion of JAM-A increases RhoA and actomyosin activity, which is mediated by the recruitment of p114RhoGEF to cell-cell junctions [

65]. At the same time, JAM-A depletion increases tension on ZO-1, which is most likely mediated by the increased actomyosin activity. By regulating the local activity of RhoA, JAM-A has a direct impact on the mechanical load acting on ZO-1 at TJs. It is also noteworthy that apart from the regulation of this intrinsic mechanical tension acting on TJs, JAM-A may also regulate extrinsic force load on cells. Direct application of pulling forces on JAM-A through trans-homophilic JAM-A interaction activates various RhoA GEFs and increases RhoA activity [

72]. Since JAM-A is not exclusively localized at the TJs [

73,

74], this activity of JAM-A may not be restricted to TJs.

5. Integral membrane proteins and phase separation at the TJs

The TJs represent an adhesive structure at the apical region of cell-cell junctions that is highly enriched in cell adhesion molecules, cytoplasmic adapter proteins and signaling proteins [

2,

75]. As mentioned before, many of the adapter proteins are modular in nature and contain multiple protein-protein interaction domains such as PDZ domains, SH2 domains, or SH3 domains [

76], which promotes the formation of multimolecular protein complexes involved in the initiation of signaling cascades triggered by cell-cell adhesion. Studies in the recent years have shown that the formation of such large protein complexes is facilitated by a process called liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) [

77,

78].

LLPS is driven by weak interactions between multivalent molecules which at a specific concentration start to exclude the surrounding solution and form aggregates. This process promotes the formation of molecular condensates in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus (three-dimensional (3D)-LLPS), or the assembly of clusters consisting of adhesion receptors and their cytoplasmic binding partners in the plasma membrane (2D-LLPS, membrane-associated LLPS) [

78]. At the plasma membrane, cluster formation can be triggered by phosphorylation of transmembrane receptors, which provides a means for the dynamic and reversible formation of protein clusters [

79]. In addition, transmembrane receptors frequently dimerize, either constitutively or in response to ligand binding [

79], enabling a dimer to interact with a distinct multivalent cytoplasmic scaffolding protein. This property contributes to a positive feed-back mechanism for the clustering of transmembrane receptors [

80], a mechanism that might be of particular importance for the “leak pathway” of TJs [

50].

Recent evidence indicates that LLPS-mediated condensation of the three zonula occludens proteins ZO-1, ZO-2 and ZO-3 drives the accumulation of TJ components including claudins at a specific membrane compartment, and that this separation of ZO proteins into membrane-attached compartments is necessary for the formation of claudin-based strands and, thus, for the development of functional TJs, both in cell culture and in the organism [

81,

82,

83]. Notably, the sequestration of ZO proteins from cytoplasmic condensates into membrane-associated compartments is dependent on mechanical forces [

82,

83] suggesting that force-mediated conformational changes of ZO proteins drive the formation of multiprotein complexes at the TJs. As recently shown, ZO-1 is under tensile stress [

65], which induces an open conformation that exposes binding sites for interaction partners including occludin [

64]. The direct interaction of JAM-A with the third PDZ domain of ZO-1 suggest that JAM-A at the TJs may act as a membrane receptor for ZO-1 which triggers the transition of ZO-1 cytoplasmic condensates into ZO-1 surface condensates required for TJ formation. In vitro partition assays revealed a co-clustering of JAM-A with claudin-2 [

84]. Through its interaction with ZO-1 and ZO-2, JAM-A appears as likely transmembrane component at TJs that initiates the formation of surface condensates. At the same time, JAM-A’s clustering at the TJs may be the result ZO protein condensate formation at TJs.

6. Lipid modifications of integral membrane proteins at TJs

TJs undergo continuous remodeling not only in response to mechanical challenges but also at steady state [

85,

86,

87]. This dynamic behaviour is also reflected in the constant reorganization of TJ strands [

85] accompanied by a rapid diffusion of TJ components within the membrane and a high exchange rate between the membrane and intracellular pools of some other TJ components [

86]. A rapid turnover of proteins can be regulated by reversible post-translational modifications including the attachment of phosphate residues, the addition of ubiquitin and ubiquitin-related residues, or the additon of acyl chains. In fact, many TJ-localized membrane proteins are post-translationally modified [

88,

89].

S-palmitoylation, i.e. the reversible addition of a saturated C16 fatty acid chain to specific cystein residues via a thioester bond [

90], appears as mechanism underlying the specific localization of several membrane proteins at the TJs. S-palmitoylation of membrane proteins promotes their association with membrane domains that are enriched for cholesterol and sphingolipids, so-called lipid rafts [

91,

92]. Of note, TJs have been described as raft-like membrane microdomains that are enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids [

93,

94]. S-palmitoylation has been identified in several members of the claudin family [

95,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100], as well as in JAM-C [

101] and Angulin-1 [

102]. S-palmitoylation of these TJ membrane proteins may thus contribute to the specific and perhaps dynamically regulated localization at the TJs.

The role of S-palmitoylation has recently been underlined by studies showing that claudins that lack the PBM and thus cannot be recruited by ZO proteins [

103,

104] still can localize to TJs and form TJ strands, whereas a palmitoylation-deficient claudin mutant is no longer localized at the TJs [

100]. This study revealed that ZO proteins, besides their widely accepted function in acting as a scaffold for a number of integral membrane proteins including claudins, IgSF members and occludin at the TJs, also regulate the accumulation of cholesterol at the TJs through a mechanism that involves the formation of the circumferential actin ring at the TJs [

100]. Importantly, this latter function of ZO proteins is sufficient to promote the formation of claudin-dependent TJ strands. This study, thus, also established a hierarchy of ZO protein-mediated functions in TJ formation and provided important new insights into the functional relevance of palmityolation of TJ membrane proteins.

7. Summary and conclusions

The TJs maintain a selective permeable seal between epithelial cells to establish a barrier between tissue compartments. Live cell imaging experiments using fluorescently tagged TJ proteins experiments have revealed that TJ strands are highly dynamic structures at steady state. The dynamic properties of TJ strands are most likely an evolutionary adaptation to the mechanical forces imposed on cell-cell junctions during cellular processes like cell division or cell extrusion but also during developmental processes such as cell rearrangements and tissue stretching and bending. A dynamic reorganization of TJ strands allows the TJs to maintain an intact barrier in the presence of mechanical challenges. Cell adhesion receptors at the TJs are critical in sensing and relaying mechanical challenges at the cellular scale. The association of several different adhesive membrane proteins with the force-sensor and actin-interactor ZO-1 provides a mechanism how forces are sensed and translated into intracellular signaling cascades by cell adhesion receptors. Also, the recent identification of cytoplasmic ZO-1 condensates and their transition into surface condensates, presumably triggered by ZO-1 binding to JAM-A, provides a possible mechanism for a dynamic regulation of the protein composition at the TJs. A better understanding of the role of cell adhesion receptors and their interaction with scaffolding proteins in TJ physiology will be a challenging task for future studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all members of the Institute-associated Research Group “Cell Adhesion and Cell Polarity” for their help and for useful discussions.

Author Contributions

N.W. and K.E. designed and conceived the article, and wrote the manuscript. Both authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding resources

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (EB 160/8-1; EXC 1003-CiMIC) to KE and the Medical Faculty of the University of Münster (MedK-fellowship to NW).

References

- Buckley, C.E.; St Johnston, D. Apical-basal polarity and the control of epithelial form and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022, 23, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zihni, C.; Mills, C.; Matter, K.; Balda, M.S. Tight junctions: from simple barriers to multifunctional molecular gates. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2016, 17, 564–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegazy, M.; Perl, A.L.; Svoboda, S.A.; Green, K.J. Desmosomal Cadherins in Health and Disease. Annu Rev Pathol 2022, 17, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladoux, B.; Mege, R.M. Mechanobiology of collective cell behaviours. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2017, 18, 743–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Gonzalez, R.; Peifer, M. Powering morphogenesis: multiscale challenges at the interface of cell adhesion and the cytoskeleton. Mol Biol Cell 2022, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knauf, F.; Brewer, J.R.; Flavell, R.A. Immunity, microbiota and kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2019, 15, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, A.W.; Weinberg, R.A. Linking EMT programmes to normal and neoplastic epithelial stem cells. Nat Rev Cancer 2021, 21, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Belmonte, F.; Perez-Moreno, M. Epithelial cell polarity, stem cells and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2011, 12, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, P.W.; Clarke, D.N.; Weis, W.I.; Lowe, C.J.; Nelson, W.J. The evolutionary origin of epithelial cell-cell adhesion mechanisms. Curr Top Membr 2013, 72, 267–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.S.; Zaidel-Bar, R. Pre-metazoan origins and evolution of the cadherin adhesome. Biol Open 2014, 3, 1183–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeichi, M. Dynamic contacts: rearranging adherens junctions to drive epithelial remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014, 15, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasileva, E.; Citi, S. The role of microtubules in the regulation of epithelial junctions. Tissue Barriers 2018, 6, 1539596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, L.; Hatzfeld, M.; Keil, R. Desmosomes as Signaling Hubs in the Regulation of Cell Behavior. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 745670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zihni, C.; Balda, M.S.; Matter, K. Signalling at tight junctions during epithelial differentiation and microbial pathogenesis. J Cell Sci 2014, 127, 3401–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonsa, A.M.; Na, T.Y.; Gumbiner, B.M. E-cadherin in contact inhibition and cancer. Oncogene 2018, 37, 4769–4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broussard, J.A.; Jaiganesh, A.; Zarkoob, H.; Conway, D.E.; Dunn, A.R.; Espinosa, H.D.; Janmey, P.A.; Green, K.J. Scaling up single-cell mechanics to multicellular tissues - the role of the intermediate filament-desmosome network. J Cell Sci 2020, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinemann, U.; Schuetz, A. Structural Features of Tight-Junction Proteins. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, C.; Schwietzer, Y.A.; Otani, T.; Furuse, M.; Ebnet, K. Physiological functions of junctional adhesion molecules (JAMs) in tight junctions. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2020, 1862, 183299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otani, T.; Furuse, M. Tight Junction Structure and Function Revisited. Trends Cell Biol 2020, 30, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piontek, J.; Krug, S.M.; Protze, J.; Krause, G.; Fromm, M. Molecular architecture and assembly of the tight junction backbone. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2020, 1862, 183279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, T.; Chiba, H. Molecular organization, regulation and function of tricellular junctions. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2020, 1862, 183143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, A.C.; Higashi, T.; Chiba, H. Tight-junction strand networks and tightness of the epithelial barrier. Microscopy (Oxf) 2023, 72, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margolis, B. The Crumbs3 Polarity Protein. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Yatim, S.; Peng, S.; Gunaratne, J.; Hunziker, W.; Ludwig, A. The Mammalian Crumbs Complex Defines a Distinct Polarity Domain Apical of Epithelial Tight Junctions. Curr Biol 2020, 30, 2791–2804 e2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, G.C.; Lucas, E.P.; Brain, R.; Tournier, A.; Thompson, B.J. Positive feedback and mutual antagonism combine to polarize Crumbs in the Drosophila follicle cell epithelium. Curr Biol 2012, 22, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuse, M.; Tsukita, S. Claudins in occluding junctions of humans and flies. Trends Cell Biol 2006, 16, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunzel, D.; Yu, A.S. Claudins and the modulation of tight junction permeability. Physiol Rev 2013, 93, 525–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, K.; Furuse, M.; Sasaki, H.; Sonoda, N.; Fujita, K.; Nagafuchi, A.; Tsukita, S. Ca(2+)-independent cell-adhesion activity of claudins, a family of integral membrane proteins localized at tight junctions. Curr Biol 1999, 9, 1035–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuse, M.; Sasaki, H.; Fujimoto, K.; Tsukita, S. A single gene product, claudin-1 or -2, reconstitutes tight junction strands and recruits occludin in fibroblasts. J Cell Biol 1998, 143, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuse, M.; Sasaki, H.; Tsukita, S. Manner of interaction of heterogeneous claudin species within and between tight junction strands. J Cell Biol 1999, 147, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukita, S.; Tanaka, H.; Tamura, A. The Claudins: From Tight Junctions to Biological Systems. Trends in biochemical sciences 2019, 44, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raleigh, D.R.; Marchiando, A.M.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, L.; Sasaki, H.; Wang, Y.; Long, M.; Turner, J.R. Tight junction-associated MARVEL proteins marveld3, tricellulin, and occludin have distinct but overlapping functions. Mol Biol Cell 2010, 21, 1200–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Pulido, L.; Martin-Belmonte, F.; Valencia, A.; Alonso, M.A. MARVEL: a conserved domain involved in membrane apposition events. Trends in biochemical sciences 2002, 27, 599–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikenouchi, J.; Furuse, M.; Furuse, K.; Sasaki, H.; Tsukita, S.; Tsukita, S. Tricellulin constitutes a novel barrier at tricellular contacts of epithelial cells. J Cell Biol 2005, 171, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cording, J.; Berg, J.; Kading, N.; Bellmann, C.; Tscheik, C.; Westphal, J.K.; Milatz, S.; Gunzel, D.; Wolburg, H.; Piontek, J.; et al. In tight junctions, claudins regulate the interactions between occludin, tricellulin and marvelD3, which, inversely, modulate claudin oligomerization. J Cell Sci 2013, 126, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Itallie, C.M.; Anderson, J.M. Occludin confers adhesiveness when expressed in fibroblasts. J Cell Sci 1997, 110 ( Pt 9), 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitou, M.; Furuse, M.; Sasaki, H.; Schulzke, J.D.; Fromm, M.; Takano, H.; Noda, T.; Tsukita, S. Complex phenotype of mice lacking occludin, a component of tight junction strands. Mol Biol Cell 2000, 11, 4131–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steed, E.; Rodrigues, N.T.; Balda, M.S.; Matter, K. Identification of MarvelD3 as a tight junction-associated transmembrane protein of the occludin family. BMC Cell Biol 2009, 10, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugawara, T.; Furuse, K.; Otani, T.; Wakayama, T.; Furuse, M. Angulin-1 seals tricellular contacts independently of tricellulin and claudins. J Cell Biol 2021, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Haraguchi, D.; Shigetomi, K.; Matsuzawa, K.; Uchida, S.; Ikenouchi, J. Tricellulin secures the epithelial barrier at tricellular junctions by interacting with actomyosin. J Cell Biol 2022, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebnet, K. Junctional Adhesion Molecules (JAMs): Cell Adhesion Receptors With Pleiotropic Functions in Cell Physiology and Development. Physiol Rev 2017, 97, 1529–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, C.J.; Shieh, J.T.; Pickles, R.J.; Okegawa, T.; Hsieh, J.T.; Bergelson, J.M. The coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor is a transmembrane component of the tight junction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98, 15191–15196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirabayashi, S.; Tajima, M.; Yao, I.; Nishimura, W.; Mori, H.; Hata, Y. JAM4, a junctional cell adhesion molecule interacting with a tight junction protein, MAGI-1. Mol Cell Biol 2003, 23, 4267–4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raschperger, E.; Engstrom, U.; Pettersson, R.F.; Fuxe, J. CLMP, a novel member of the CTX family and a new component of epithelial tight junctions. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasdala, I.; Wolburg-Buchholz, K.; Wolburg, H.; Kuhn, A.; Ebnet, K.; Brachtendorf, G.; Samulowitz, U.; Kuster, B.; Engelhardt, B.; Vestweber, D.; et al. A transmembrane tight junction protein selectively expressed on endothelial cells and platelets. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 16294–16303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, K.; Ishida, T.; Penta, K.; Rezaee, M.; Yang, E.; Wohlgemuth, J.; Quertermous, T. Cloning of an immunoglobulin family adhesion molecule selectively expressed by endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 16223–16231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuse, M.; Izumi, Y.; Oda, Y.; Higashi, T.; Iwamoto, N. Molecular organization of tricellular tight junctions. Tissue Barriers 2014, 2, e28960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, T.; Tokuda, S.; Kitajiri, S.; Masuda, S.; Nakamura, H.; Oda, Y.; Furuse, M. Analysis of the 'angulin' proteins LSR, ILDR1 and ILDR2--tricellulin recruitment, epithelial barrier function and implication in deafness pathogenesis. J Cell Sci 2013, 126, 966–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, S.; Oda, Y.; Sasaki, H.; Ikenouchi, J.; Higashi, T.; Akashi, M.; Nishi, E.; Furuse, M. LSR defines cell corners for tricellular tight junction formation in epithelial cells. J Cell Sci 2011, 124, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Weber, C.R.; Raleigh, D.R.; Yu, D.; Turner, J.R. Tight junction pore and leak pathways: a dynamic duo. Annu Rev Physiol 2011, 73, 283–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, A.; Chanez-Paredes, S.D.; Haest, X.; Turner, J.R. Paracellular permeability and tight junction regulation in gut health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meoli, L.; Gunzel, D. The role of claudins in homeostasis. Nat Rev Nephrol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otani, T.; Nguyen, T.P.; Tokuda, S.; Sugihara, K.; Sugawara, T.; Furuse, K.; Miura, T.; Ebnet, K.; Furuse, M. Claudins and JAM-A coordinately regulate tight junction formation and epithelial polarity. J Cell Biol 2019, 218, 3372–3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbacher, T.; Kummer, D.; Ebnet, K. Junctional adhesion molecule-A: functional diversity through molecular promiscuity. Cell Mol Life Sci 2018, 75, 1393–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Padura, I.; Lostaglio, S.; Schneemann, M.; Williams, L.; Romano, M.; Fruscella, P.; Panzeri, C.; Stoppacciaro, A.; Ruco, L.; Villa, A.; et al. Junctional adhesion molecule, a novel member of the immunoglobulin superfamily that distributes at intercellular junctions and modulates monocyte transmigration. J Cell Biol 1998, 142, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staehelin, L.A. Further observations on the fine structure of freeze-cleaved tight junctions. J Cell Sci 1973, 13, 763–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, J.B.; Karnovsky, M.J. The structure of the zonula occludens. A single fibril model based on freeze-fracture. J Cell Biol 1974, 60, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charras, G.; Yap, A.S. Tensile Forces and Mechanotransduction at Cell-Cell Junctions. Curr Biol 2018, 28, R445–R457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallou, A.; Brunet, T. On growth and force: mechanical forces in development. Development 2020, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, L.S.; Rangarajan, S.; Sadhanasatish, T.; Grashoff, C. Molecular Force Measurement with Tension Sensors. Annu Rev Biophys 2021, 50, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, D.; Bellaiche, Y. Mechanical Force-Driven Adherens Junction Remodeling and Epithelial Dynamics. Dev Cell 2018, 47, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citi, S. The mechanobiology of tight junctions. Biophys Rev 2019, 11, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephenson, R.E.; Higashi, T.; Erofeev, I.S.; Arnold, T.R.; Leda, M.; Goryachev, A.B.; Miller, A.L. Rho Flares Repair Local Tight Junction Leaks. Dev Cell 2019, 48, 445–459 e445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spadaro, D.; Le, S.; Laroche, T.; Mean, I.; Jond, L.; Yan, J.; Citi, S. Tension-Dependent Stretching Activates ZO-1 to Control the Junctional Localization of Its Interactors. Curr Biol 2017, 27, 3783–3795 e3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, A.J.; Zihni, C.; Ruppel, A.; Hartmann, C.; Ebnet, K.; Tada, M.; Balda, M.S.; Matter, K. Interplay between Extracellular Matrix Stiffness and JAM-A Regulates Mechanical Load on ZO-1 and Tight Junction Assembly. Cell Rep 2020, 32, 107924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, A.J.; Zihni, C.; Krug, S.M.; Maraspini, R.; Otani, T.; Furuse, M.; Honigmann, A.; Balda, M.S.; Matter, K. ZO-1 Guides Tight Junction Assembly and Epithelial Morphogenesis via Cytoskeletal Tension-Dependent and -Independent Functions. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatte, G.; Prigent, C.; Tassan, J.P. Tight junctions negatively regulate mechanical forces applied to adherens junctions in vertebrate epithelial tissue. J Cell Sci 2018, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzoni, G.; Martinez-Estrada, O.M.; Orsenigo, F.; Cordenonsi, M.; Citi, S.; Dejana, E. Interaction of junctional adhesion molecule with the tight junction components ZO-1, cingulin, and occludin. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 20520–20526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebnet, K.; Schulz, C.U.; Meyer Zu Brickwedde, M.K.; Pendl, G.G.; Vestweber, D. Junctional adhesion molecule interacts with the PDZ domain-containing proteins AF-6 and ZO-1. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 27979–27988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomme, J.; Fanning, A.S.; Caffrey, M.; Lye, M.F.; Anderson, J.M.; Lavie, A. The Src homology 3 domain is required for junctional adhesion molecule binding to the third PDZ domain of the scaffolding protein ZO-1. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 43352–43360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.C.; Sumagin, R.; Rankin, C.R.; Leoni, G.; Mina, M.J.; Reiter, D.M.; Stehle, T.; Dermody, T.S.; Schaefer, S.A.; Hall, R.A.; et al. JAM-A associates with ZO-2, afadin, and PDZ-GEF1 to activate Rap2c and regulate epithelial barrier function. Mol Biol Cell 2013, 24, 2849–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, D.W.; Tolbert, C.E.; Burridge, K. Tension on JAM-A activates RhoA via GEF-H1 and p115 RhoGEF. Mol Biol Cell 2016, 27, 1420–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Nusrat, A.; Schnell, F.J.; Reaves, T.A.; Walsh, S.; Pochet, M.; Parkos, C.A. Human junction adhesion molecule regulates tight junction resealing in epithelia. J Cell Sci 2000, 113 ( Pt 13), 2363–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iden, S.; Misselwitz, S.; Peddibhotla, S.S.; Tuncay, H.; Rehder, D.; Gerke, V.; Robenek, H.; Suzuki, A.; Ebnet, K. aPKC phosphorylates JAM-A at Ser285 to promote cell contact maturation and tight junction formation. J Cell Biol 2012, 196, 623–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebnet, K. Organization of multiprotein complexes at cell-cell junctions. Histochem Cell Biol 2008, 130, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawson, T.; Nash, P. Assembly of cell regulatory systems through protein interaction domains. Science 2003, 300, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banani, S.F.; Lee, H.O.; Hyman, A.A.; Rosen, M.K. Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2017, 18, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Case, L.B.; Ditlev, J.A.; Rosen, M.K. Regulation of Transmembrane Signaling by Phase Separation. Annu Rev Biophys 2019, 48, 465–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, B.J.; Yu, J. Protein Clusters in Phosphotyrosine Signal Transduction. J Mol Biol 2018, 430, 4547–4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; LuValle-Burke, I.; Pombo-Garcia, K.; Honigmann, A. Biomolecular condensates in epithelial junctions. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2022, 77, 102089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutel, O.; Maraspini, R.; Pombo-Garcia, K.; Martin-Lemaitre, C.; Honigmann, A. Phase Separation of Zonula Occludens Proteins Drives Formation of Tight Junctions. Cell 2019, 179, 923–936 e911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwayer, C.; Shamipour, S.; Pranjic-Ferscha, K.; Schauer, A.; Balda, M.; Tada, M.; Matter, K.; Heisenberg, C.P. Mechanosensation of Tight Junctions Depends on ZO-1 Phase Separation and Flow. Cell 2019, 179, 937–952 e918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, N.; Yamamoto, T.S.; Yasue, N.; Takagi, C.; Fujimori, T.; Ueno, N. Force-dependent remodeling of cytoplasmic ZO-1 condensates contributes to cell-cell adhesion through enhancing tight junctions. iScience 2022, 25, 103846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Zahao, X.; Wiegand, T.; Bartolucci, G.; Martin-Lemaitre, C.; Grill, S.W.; Hyman, A.A.; Weber, C.; Honigmall, A. Assembly of tight junction belts by surface condensation and actin elongation. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, H.; Matsui, C.; Furuse, K.; Mimori-Kiyosue, Y.; Furuse, M.; Tsukita, S. Dynamic behavior of paired claudin strands within apposing plasma membranes. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2003, 100, 3971–3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Weber, C.R.; Turner, J.R. The tight junction protein complex undergoes rapid and continuous molecular remodeling at steady state. J Cell Biol 2008, 181, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, S.; Stephenson, R.E.; Miller, A.L. Multiscale dynamics of tight junction remodeling. J Cell Sci 2019, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigetomi, K.; Ikenouchi, J. Regulation of the epithelial barrier by post-translational modifications of tight junction membrane proteins. J Biochem 2018, 163, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiche, J.; Huber, O. Post-translational modifications of tight junction transmembrane proteins and their direct effect on barrier function. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2020, 1862, 183330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaskovic, S.; Blanc, M.; van der Goot, F.G. What does S-palmitoylation do to membrane proteins? FEBS J 2013, 280, 2766–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingwood, D.; Simons, K. Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle. Science 2010, 327, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levental, I.; Lingwood, D.; Grzybek, M.; Coskun, U.; Simons, K. Palmitoylation regulates raft affinity for the majority of integral raft proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 22050–22054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nusrat, A.; Parkos, C.A.; Verkade, P.; Foley, C.S.; Liang, T.W.; Innis-Whitehouse, W.; Eastburn, K.K.; Madara, J.L. Tight junctions are membrane microdomains. J Cell Sci 2000, 113 ( Pt 10) Pt 10, 1771–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigetomi, K.; Ono, Y.; Inai, T.; Ikenouchi, J. Adherens junctions influence tight junction formation via changes in membrane lipid composition. J Cell Biol 2018, 217, 2373–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Itallie, C.M.; Gambling, T.M.; Carson, J.L.; Anderson, J.M. Palmitoylation of claudins is required for efficient tight-junction localization. J Cell Sci 2005, 118, 1427–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiler, S.; Mu, W.; Zoller, M.; Thuma, F. The importance of claudin-7 palmitoylation on membrane subdomain localization and metastasis-promoting activities. Cell Commun Signal 2015, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodenburg, R.N.P.; Snijder, J.; van de Waterbeemd, M.; Schouten, A.; Granneman, J.; Heck, A.J.R.; Gros, P. Stochastic palmitoylation of accessible cysteines in membrane proteins revealed by native mass spectrometry. Nature communications 2017, 8, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajagopal, N.; Irudayanathan, F.J.; Nangia, S. Palmitoylation of Claudin-5 Proteins Influences Their Lipid Domain Affinity and Tight Junction Assembly at the Blood-Brain Barrier Interface. J Phys Chem B 2019, 123, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Chen, X.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, L.; Xia, Z.; Ye, K.; Jiang, H.; Yang, B.; Ying, M.; Cao, J.; et al. ZDHHC12-mediated claudin-3 S-palmitoylation determines ovarian cancer progression. Acta Pharm Sin B 2020, 10, 1426–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigetomi, K.; Ono, Y.; Matsuzawa, K.; Ikenouchi, J. Cholesterol-rich domain formation mediated by ZO proteins is essential for tight junction formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023, 120, e2217561120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramsangtienchai, P.; Spiegelman, N.A.; Cao, J.; Lin, H. S-Palmitoylation of Junctional Adhesion Molecule C Regulates Its Tight Junction Localization and Cell Migration. The Journal of biological chemistry 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oda, Y.; Sugawara, T.; Fukata, Y.; Izumi, Y.; Otani, T.; Higashi, T.; Fukata, M.; Furuse, M. The extracellular domain of angulin-1 and palmitoylation of its cytoplasmic region are required for angulin-1 assembly at tricellular contacts. J Biol Chem 2020, 295, 4289–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, M.; Furuse, M.; Morita, K.; Kubota, K.; Saitou, M.; Tsukita, S. Direct binding of three tight junction-associated MAGUKs, ZO-1, ZO-2, and ZO-3, with the COOH termini of claudins. J Cell Biol 1999, 147, 1351–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umeda, K.; Ikenouchi, J.; Katahira-Tayama, S.; Furuse, K.; Sasaki, H.; Nakayama, M.; Matsui, T.; Tsukita, S.; Furuse, M.; Tsukita, S. ZO-1 and ZO-2 independently determine where claudins are polymerized in tight-junction strand formation. Cell 2006, 126, 741–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonikian, R.; Zhang, Y.; Sazinsky, S.L.; Currell, B.; Yeh, J.H.; Reva, B.; Held, H.A.; Appleton, B.A.; Evangelista, M.; Wu, Y.; et al. A specificity map for the PDZ domain family. PLoS biology 2008, 6, e239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).