Submitted:

07 November 2023

Posted:

08 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 62E17; 62G32; 62L15; 62P05; 91A35; 91B28; 91B32

1. Introduction & Review of the Literature

1.1. Fat-Tailed Distributions in Economic Time Series – History

1.1.1. Symmetry in the stable Pareto

1.1.2. The Stable Pareto Distribution and the Meaning of "Stable"

1.1.3. Relationship to Stationarity

1.1.4. Accounting for Potential Non-Stationarity

1.1.5. Emergence of other fat-tailed distribution modeling techniques and the Generalized Hyperbolic Distribution (GHD)

- Substantial flexibility afforded by multiple shape parameters, enabling the GHD to accurately fit myriad empirically observed non-normal behaviors in financial and economic data sets. Both leptokurtic and platykurtic distributions can be readily captured.

- Mathematical tractability, with the probability density function, cumulative distribution function, and characteristic function expressible in closed analytical form. This facilitates rigorous mathematical analysis and inference.

- Theoretical connections to fundamental economic concepts such as utility maximization. Various special cases also share close relationships with other pivotal distributions like the variance-gamma distribution.

- Empirical studies across disparate samples and time horizons consistently demonstrate superior goodness-of-fit compared to normal and stable models when applied to asset returns, market indices, and other economic variables.

- Ability to more accurately model tail risks and extreme events compared to normal models, enabling robust quantification of value-at-risk, expected shortfall, and other vital risk metrics.

- Despite the lack of a simple analytical formula, the distribution function can be reliably evaluated through straightforward numerical methods, aiding practical implementation.

1.2. Mathematical Expectation – History

1.3. Optimal Allocations – History

2. Characteristics of the Generalized Hyperbolic Distribution (GHD) – Distributional Form and Corresponding Parameters

- More general distribution class that includes Student's t, Laplace, hyperbolic, normal-inverse Gaussian, and variance-gamma as special cases. Its Mathematical tractability provides ability to derive other distribution properties.

- Exhibits semi-heavy tail behavior which allows modeling data with extreme events and fat-tailed probabilities.

- Density function involves modified Bessel functions of the second kind (BesselK functions). So although there is a lack of closed form density function, it can still be numerically evaluated in straightforward manner.

2.1 Parameter description

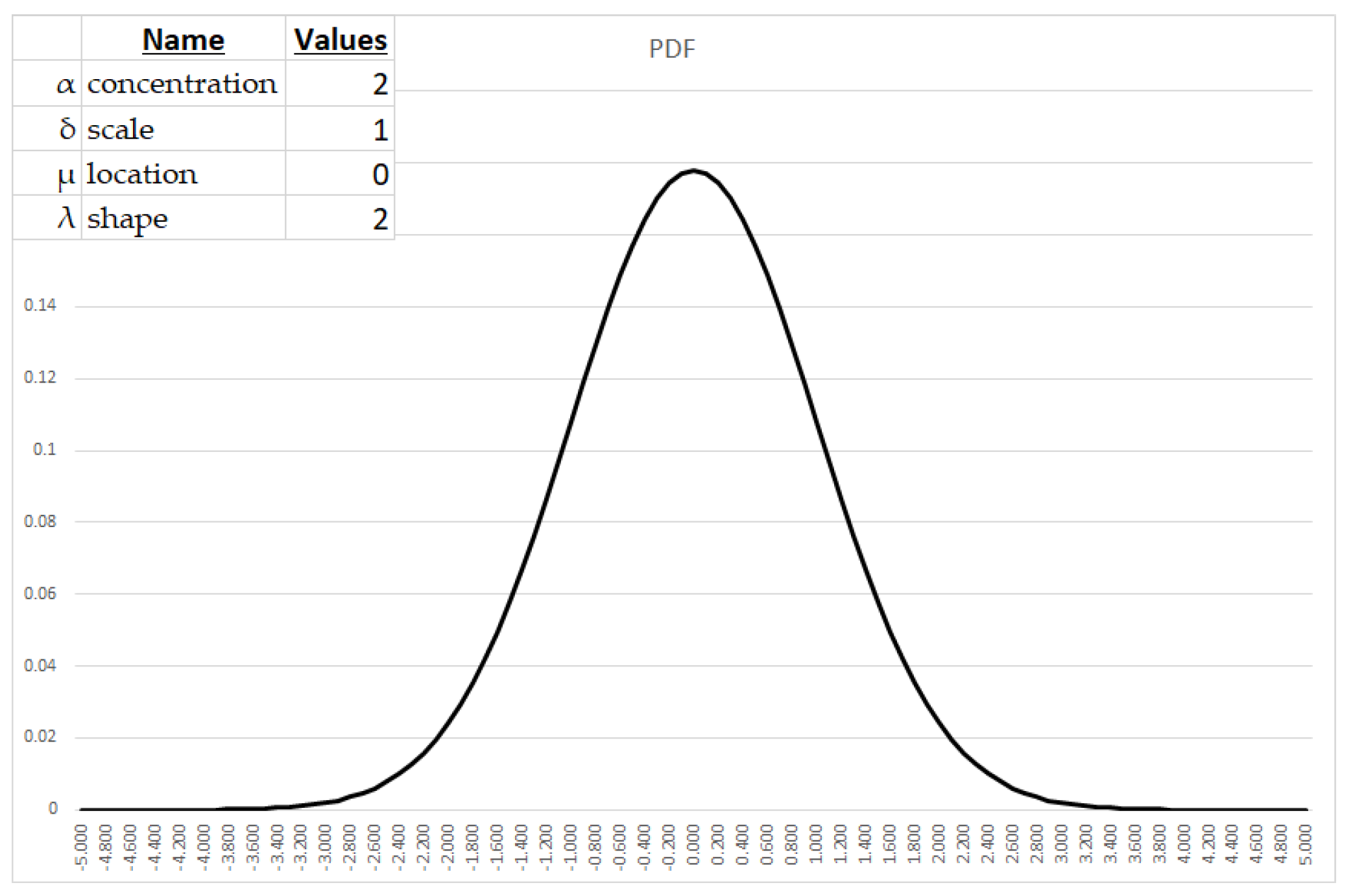

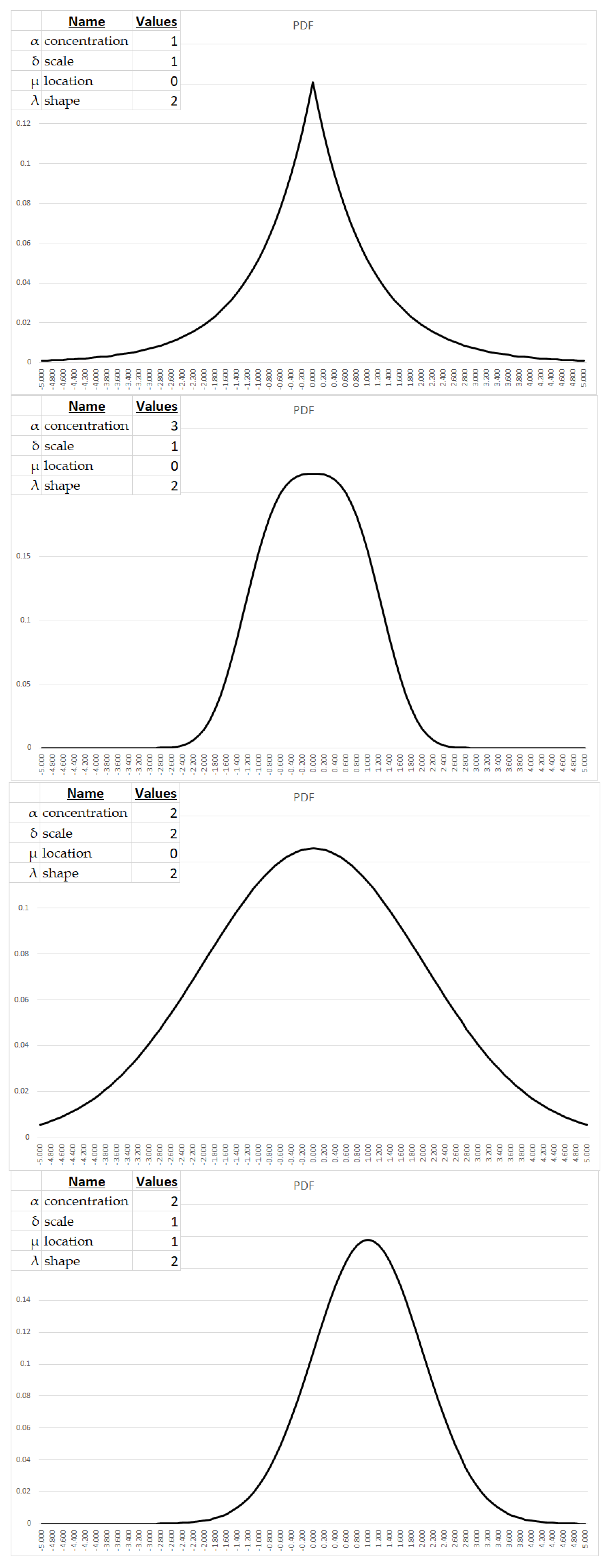

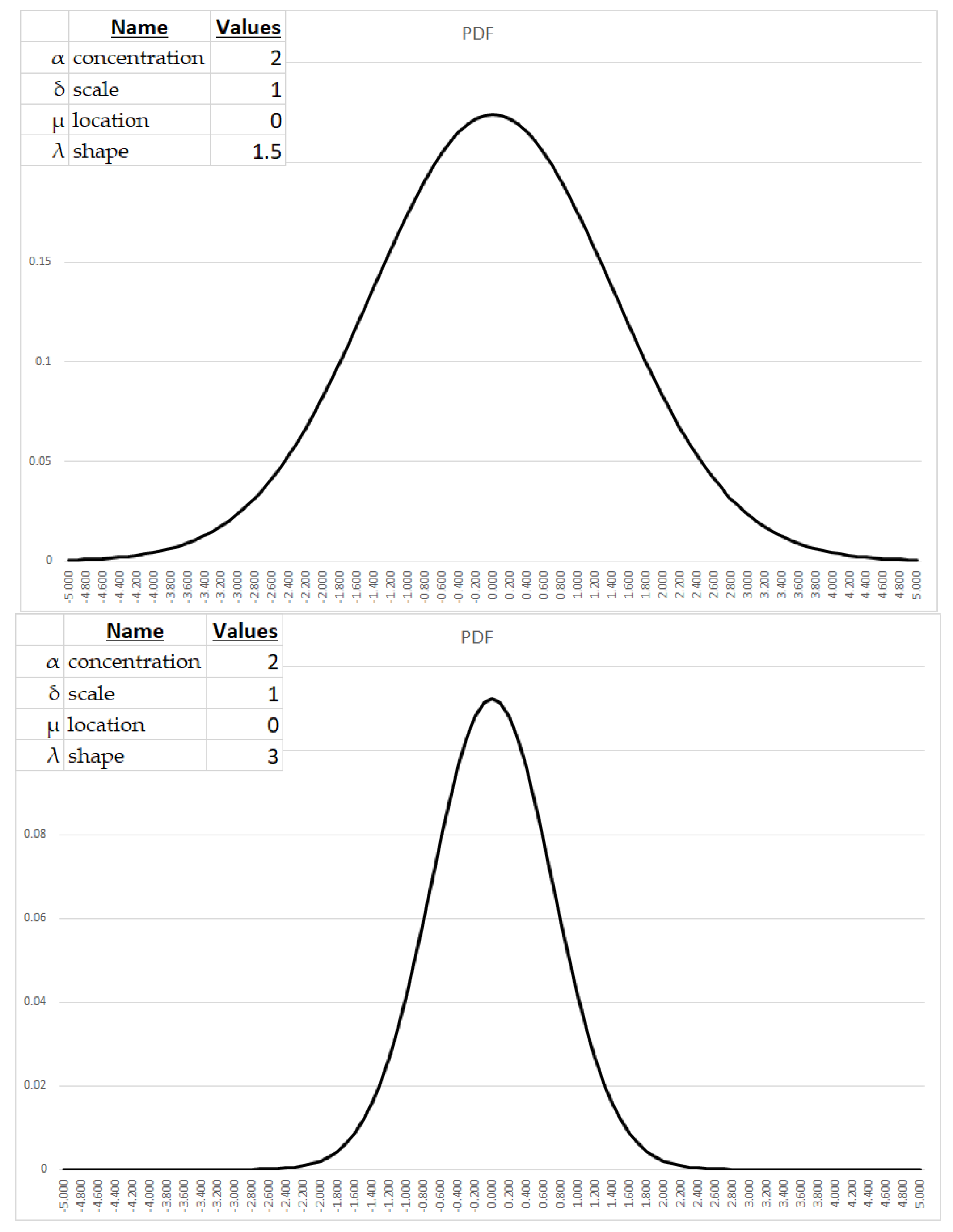

- The concentration parameter (α) modulates tail weight, with larger values engendering heavier tails and hence elevating the probability mass attributable to extreme deviations. α typically assumes values on the order of 0.1 to 10 for modeling economic phenomena.

- The scale parameter (δ) controls the spread about the central tendency, with larger values yielding expanded variance and wider dispersion. Applied economic analysis often utilizes δ ranging from 0.1 to 10.

- The location parameter (μ) shifts the distribution along the abscissa, with positive values effecting rightward translation. In economic contexts, μ commonly falls between -10 and 10.

- The shape parameter (λ) influences peakedness and flatness, with larger values precipitating more acute modes and sharper central tendencies. λ on the order of 0.1 to 10 frequently appears in economic applications.

3. Parameter Estimation of the Symmetrical GHD

4. Discussion

4.1 The goal of median-sorted outcome after N trials; the process of determining the representative "expected" setof oucomes

- Determine what these finite-length expectations are, given a probability distribution we believe the outcomes comport to so as to base on our sample data and the fitted parameters of that distribution, -and-

- Determine a likely N-length sequence of outcomes for what we "expect," that is, a likely set of N outcomes representative of the outcome stream that would see half of the outcome streams of N length be better than, and half less than such a stream of expected outcomes. It is this "expected, representative stream" we will use as input to other functions such as determining growth-optimal allocations.

4.2. Determining median-sorted outcome after N trials

4.2.1. Calculating the inverse CDF

4.2.2. Worst-case expected outcome

4.2.3. Calculating the representative stream of outcomes from the median-sorted outcome

- For each of N outcomes, we determine the corresponding probability by taking the value returned by the inverse CDF as input to the CDF. When using the inverse CDF function, the random number generated is not the probability of the value returned by the inverse CDF. Instead, the random number generated is used as the input to the inverse CDF function to obtain a value from the distribution. This value is a random variable that follows the distribution specified by the CDF. To determine the probability of this value, you would need to use the CDF function and evaluate it at the value returned by the inverse CDF function. The CDF function gives the probability that a random variable is less than or equal to a specific value. Therefore, if you evaluate the CDF function at the value returned by the inverse CDF function, you will get the probability of that value.

- For our purposes however, we must now take any of these probabilities that are > .5 and take the absolute value of their difference to .5. Call this p`.

- p`= p if p <= .5

- p` = |1 - p| if p > .5

- c.

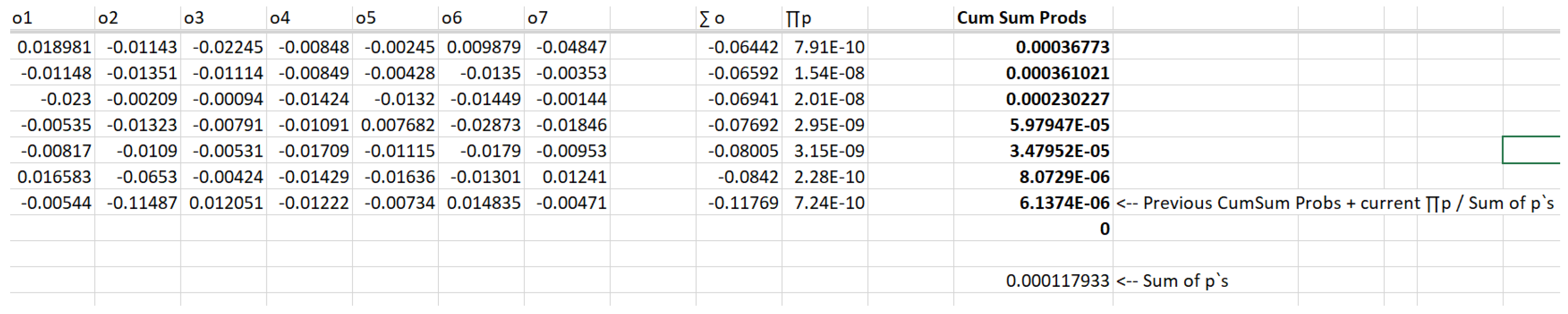

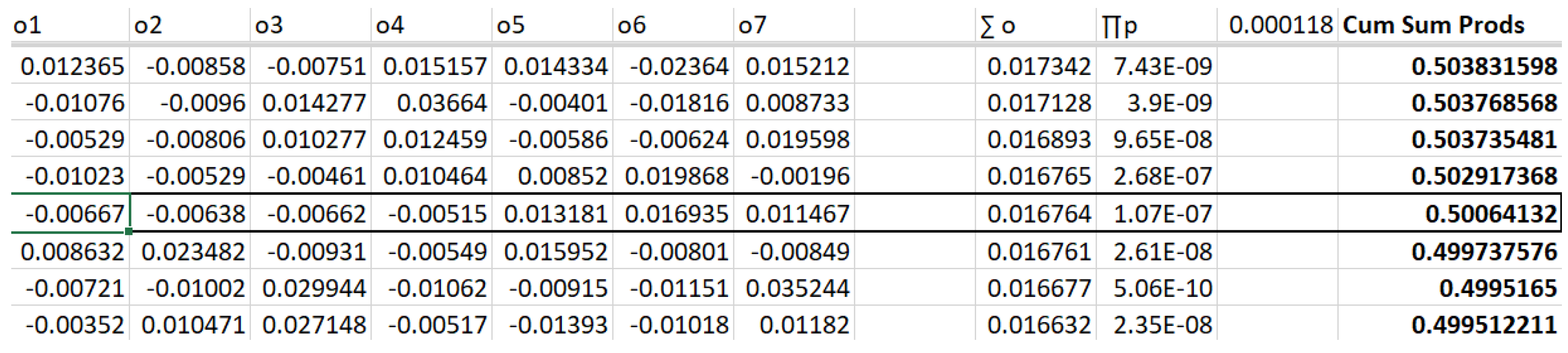

- We take M sets of N outputs, corresponding to outputs drawn from our fitted distribution as well as the corresponding p` probabilities.

- d.

- For each of these M sets of N outcome-p` combinations, we will sum the outcomes, and take the product of all of the p`s.

- e.

- We sort these M sets based on their summed outcomes.

- f.

- We now take the sum of these M product of p`s. We will call this the "SumOfProbabilities."

- g.

- For each M set, we proceed sequentially through them where each M has a cumulative probability specified as the cumulative probability of the previous M in the (outcome-sorted) sequence, plus the probability off that M divided by the SumOfProbabilities.

- h.

- It is this final calculation where we seek that M whose final calculation is closest to 0.5. This is our median sorted outcome, and the values for N which comprise it are our typical, median-sorted outcome, our expected, finite-sequence set of outcomes.

4.2.4. Example - calculating the representative stream of outcomes from the median-sorted outcome

4.3 Optimal Allocations

4.3.1 Growth-optimal fraction

4.3.2 Return/Risk Optimal Points

4.3.3 Growth Diminishment in Existential Contests

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Unit Root Tests: Unit root tests, such as the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test and the Phillips-Perron (PP) test, are widely used in time series analysis to assess the presence of a unit root in the data which indicates non-stationarity. These tests help determine whether the data series exhibits a stochastic trend or random walk behavior, indicating a lack of stationarity.

- Structural Break Tests: Structural break tests aim to detect significant shifts or changes in the statistical properties of the data at specific points in time. Techniques like the Chow test, the Quandt-Andrews test, and the Bai-Perron test are commonly employed to identify structural breaks and assess the presence of non-stationarity resulting from changes in underlying processes or regimes.

- Time Series Decomposition: Time series decomposition methods, such as trend analysis, seasonal adjustment, and filtering techniques, help separate the underlying components of the data series, allowing analysts to examine the trend, seasonality, and irregular fluctuations. Analyzing the behavior of these components can provide insights into the presence of non-stationarity and the dynamics of the data over time.

- Cointegration Analysis: Cointegration analysis is utilized to assess the long-term relationships between multiple time series variables. By examining the existence of cointegration relationships, analysts can determine whether the variables move together in the long run and whether the data series exhibit non-stationary behavior that is linked by a stable relationship.

Appendix B

References

- Marshall, A. Principles of Economics; Macmillan and, Co., 1890. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, A. Industry and Trade: A Study of Industrial Technique and Business Organization; Macmillan and Co., 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Bachelier, L. Théorie de la spéculation. Ann. Sci. De L'école Norm. Supérieure 1900, 17, 21–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévy, P. Théorie de l'addition des variables aléatoires; Gauthier-Villars: 1937.

- Kendall, D.G.; Levy, P.; Ito, K.; McKean, H.P.; Kimura, M. Processus Stochastiques et Mouvement Brownien. Biometrika 1966, 53, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, W. Theory of Probability; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Pareto, V. Pareto Distribution and its Applications in Economics. J. Econ. Stud. 1910, 5, 128–145. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbrot, B. The Variation of Certain Speculative Prices. J. Bus. Univ. Chic. 1963. [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.; Hudson, R.L. The (Mis)Behavior of Markets: A Fractal View of Risk, Ruin, and Reward; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pascal, B.; Fermat, P. Traité du triangle arithmétique. Corresp. Blaise Pascal Pierre De Fermat 1654, 2, 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Huygens. 1657. Libellus de ratiociniis in ludo aleae (A book on the principles of gambling). (Original Latin transcript translated and published in English) London: S. KEIMER for T. WOODWARD, near the Inner-Temple-Gate in Fleet-street. 1714.

- Vince, R. Expectation And Optimal F: Expected Growth With And Without Reinvestment For Discretely-Distributed Outcomes Of Finite Length As A Basis In Evolutionary Decision-Making. Far East J. Theor. Stat. 2019, 56, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernoulli, D. 1738. Specimen theoriae novae de mensura sortis (Exposition of a new theory on the measurement of risk). In Commentarii academiae scientiarum imperialis Petropolitanae 5: 175–192. Translated into English: L. Sommer. 1954. Econometrica 22: 23–36.

- Keynes, J.M. A Treatise on Probability; Macmillan: London, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.B. Speculation and the carryover. Q. J. Econ. 1936, 50, 436–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.L., Jr. A new interpretation of information rate. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1956, 35, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vince, R. Portfolio Management Formulas; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bellman, R.; Kalaba, R. On the role of dynamic programming in statistical communication theory. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1957, 3, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Optimal gambling systems for favorable games. In Proceedings of the fourth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability, Jerzy Neyman; University of California Press: Berkeley, 1961; pp. 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Latané, H.A. Criteria for Choice Among Risky Ventures. J. Politi-Econ. 1959, 67, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latane, H.; Tuttle, D. Criteria for portfolio building. J. Financ. 1967, 22, 362–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorp Edward, O. Beat the Dealer: A Winning Strategy for the Game of Twenty-One; Vintage: New York, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Thorp, E. O. (1997; revised 1998). The Kelly Criterion in blackjack, sports betting, and the stock market. The 10th International Conference on Gambling and Risk Taking, Montreal, June 1997.

- Vince, Ralph. 1992. The Mathematics of Money Management. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Samuelson, P.A. 1971. The “fallacy” of maximizing the geometric mean in long sequences of investing or gambling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 68: 2493–2496. [CrossRef]

- Samuelson, P.A. Why we should not make mean log of wealth big though years to act are long. J. Bank. Finance 1979, 3, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, M. A negative report on the ‘near optimality’ of the max-expected-log policy as applied to bounded utilities for long lived programs. J. Financial Econ. 1974, 1, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.C.; Samuelson, P.A. Fallacy of the log-normal approximation to optimal portfolio decision-making over many periods. J. Financ. Econ. 1974, 1, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vince, R.; Zhu, Q. Optimal betting sizes for the game of blackjack. J. Invest. Strat. 2015, 4, 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Prado, M.L.; Vince, R.; Zhu, Q.J. Optimal Risk Budgeting under a Finite Investment Horizon. Risks 2019, 7, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vince, R. Diminution of Malevolent Geometric Growth Through Increased Variance. J. Econ. Bus. Mark. Res. 2020, 1, 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Choi, I. Unit Roots in Economic and Financial Time Series: A Re-Evaluation at the Decision-Based Significance Levels. Econometrics 2017, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberlein, E.; Ulrich, K. Hyperbolic distributions in finance. Bernoulli 1995, 1, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prause, K. The generalized hyperbolic model: Estimation, financial derivatives, and risk measures. PhD diss., University of Freiburg, 1999.

- Küchler, U.; Klaus, N. Stock Returns and Hyperbolic Distributions. ASTIN Bull. J. Int. Actuar. Assoc. 1999, 29, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberlein, E.; Keller, U.; Prause, K. New Insights into Smile, Mispricing, and Value at Risk: The Hyperbolic Model. J. Bus. 1998, 71, 371–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Mora, J.A.; Sánchez-Ruenes, E. Generalized Hyperbolic Distribution and Portfolio Efficiency in Energy and Stock Markets of BRIC Countries. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2020, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selesho, J.M.; Naile, I. Academic Staff Retention As A Human Resource Factor: University Perspective. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. (IBER) 2014, 13, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fang, Z. Portfolio Optimization under Multivariate Affine Generalized Hyperbolic Distributions. Comput. Econ. 2022, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostovetsky, J.; Betsy, K. Distribution Analysis of S&P 500 Financial Turbulence. J. Math. Financ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Anne, N.K. Risk Management with Generalized Hyperbolic Distributions. Glob. Financ. J. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Barndorff-Nielsen, O. Exponentially decreasing distributions for the logarithm of particle size. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. A. Math. Phys. Sci. 1977, 353, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgórski, K.; Wallin, J. Convolution-invariant subclasses of generalized hyperbolic distributions. Commun. Stat. - Theory Methods 2015, 45, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klebanov, L.; Rachev, S.T. The Global Distributions of Income and Wealth; Springer-Verlag: 1996.

- Klebanov, L.; Rachev, S.T. ν-Generalized Hyperbolic Distributions. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | SP500 | % Change | Date | SP500 | % Change | |

| 20221230 | 3839.5 | 20230403 | 4124.51 | 0.003699 | ||

| 20230103 | 3824.14 | -0.004 | 20230404 | 4100.6 | -0.0058 | |

| 20230104 | 3852.97 | 0.007539 | 20230405 | 4090.38 | -0.00249 | |

| 20230105 | 3808.1 | -0.01165 | 20230406 | 4105.02 | 0.003579 | |

| 20230106 | 3895.08 | 0.022841 | 20230410 | 4109.11 | 0.000996 | |

| 20230109 | 3892.09 | -0.00077 | 20230411 | 4108.94 | -4.1E-05 | |

| 20230110 | 3919.25 | 0.006978 | 20230412 | 4091.95 | -0.00413 | |

| 20230111 | 3969.61 | 0.012849 | 20230413 | 4146.22 | 0.013263 | |

| 20230112 | 3983.17 | 0.003416 | 20230414 | 4137.64 | -0.00207 | |

| 20230113 | 3999.09 | 0.003997 | 20230417 | 4151.32 | 0.003306 | |

| 20230117 | 3990.97 | -0.00203 | 20230418 | 4154.87 | 0.000855 | |

| 20230118 | 3928.86 | -0.01556 | 20230419 | 4154.52 | -8.4E-05 | |

| 20230119 | 3898.85 | -0.00764 | 20230420 | 4129.79 | -0.00595 | |

| 20230120 | 3972.61 | 0.018918 | 20230421 | 4133.52 | 0.000903 | |

| 20230123 | 4019.81 | 0.011881 | 20230424 | 4137.04 | 0.000852 | |

| 20230124 | 4016.95 | -0.00071 | 20230425 | 4071.63 | -0.01581 | |

| 20230125 | 4016.22 | -0.00018 | 20230426 | 4055.99 | -0.00384 | |

| 20230126 | 4060.43 | 0.011008 | 20230427 | 4135.35 | 0.019566 | |

| 20230127 | 4070.56 | 0.002495 | 20230428 | 4169.48 | 0.008253 | |

| 20230130 | 4017.77 | -0.01297 | 20230501 | 4167.87 | -0.00039 | |

| 20230131 | 4076.6 | 0.014642 | 20230502 | 4119.58 | -0.01159 | |

| 20230201 | 4119.21 | 0.010452 | 20230503 | 4090.75 | -0.007 | |

| 20230202 | 4179.76 | 0.014699 | 20230504 | 4061.22 | -0.00722 | |

| 20230203 | 4136.48 | -0.01035 | 20230505 | 4136.25 | 0.018475 | |

| 20230206 | 4111.08 | -0.00614 | 20230508 | 4138.12 | 0.000452 | |

| 20230207 | 4164 | 0.012873 | 20230509 | 4119.17 | -0.00458 | |

| 20230208 | 4117.86 | -0.01108 | 20230510 | 4137.64 | 0.004484 | |

| 20230209 | 4081.5 | -0.00883 | 20230511 | 4130.62 | -0.0017 | |

| 20230210 | 4090.46 | 0.002195 | 20230512 | 4124.08 | -0.00158 | |

| 20230213 | 4137.29 | 0.011449 | 20230515 | 4136.28 | 0.002958 | |

| 20230214 | 4136.13 | -0.00028 | 20230516 | 4109.9 | -0.00638 | |

| 20230215 | 4147.6 | 0.002773 | 20230517 | 4158.77 | 0.011891 | |

| 20230216 | 4090.41 | -0.01379 | 20230518 | 4198.05 | 0.009445 | |

| 20230217 | 4079.09 | -0.00277 | 20230519 | 4191.98 | -0.00145 | |

| 20230221 | 3997.34 | -0.02004 | 20230522 | 4192.63 | 0.000155 | |

| 20230222 | 3991.05 | -0.00157 | 20230523 | 4145.58 | -0.01122 | |

| 20230223 | 4012.32 | 0.005329 | 20230524 | 4115.24 | -0.00732 | |

| 20230224 | 3970.04 | -0.01054 | 20230525 | 4151.28 | 0.008758 | |

| 20230227 | 3982.24 | 0.003073 | 20230526 | 4205.45 | 0.013049 | |

| 20230228 | 3970.15 | -0.00304 | 20230530 | 4205.52 | 1.66E-05 | |

| 20230301 | 3951.39 | -0.00473 | 20230531 | 4179.83 | -0.00611 | |

| 20230302 | 3981.35 | 0.007582 | 20230601 | 4221.02 | 0.009854 | |

| 20230303 | 4045.64 | 0.016148 | 20230602 | 4282.37 | 0.014534 | |

| 20230306 | 4048.42 | 0.000687 | 20230605 | 4273.79 | -0.002 | |

| 20230307 | 3986.37 | -0.01533 | 20230606 | 4283.85 | 0.002354 | |

| 20230308 | 3992.01 | 0.001415 | 20230607 | 4267.52 | -0.00381 | |

| 20230309 | 3918.32 | -0.01846 | 20230608 | 4293.93 | 0.006189 | |

| 20230310 | 3861.59 | -0.01448 | 20230609 | 4298.86 | 0.001148 | |

| 20230313 | 3855.76 | -0.00151 | 20230612 | 4338.93 | 0.009321 | |

| 20230314 | 3919.29 | 0.016477 | 20230613 | 4369.01 | 0.006932 | |

| 20230315 | 3891.93 | -0.00698 | 20230614 | 4372.59 | 0.000819 | |

| 20230316 | 3960.28 | 0.017562 | 20230615 | 4425.84 | 0.012178 | |

| 20230317 | 3916.64 | -0.01102 | 20230616 | 4409.59 | -0.00367 | |

| 20230320 | 3951.57 | 0.008918 | 20230620 | 4388.71 | -0.00474 | |

| 20230321 | 4002.87 | 0.012982 | 20230621 | 4365.69 | -0.00525 | |

| 20230322 | 3936.97 | -0.01646 | 20230622 | 4381.89 | 0.003711 | |

| 20230323 | 3948.72 | 0.002985 | 20230623 | 4348.33 | -0.00766 | |

| 20230324 | 3970.99 | 0.00564 | 20230626 | 4328.82 | -0.00449 | |

| 20230327 | 3977.53 | 0.001647 | 20230627 | 4378.41 | 0.011456 | |

| 20230328 | 3971.27 | -0.00157 | 20230628 | 4376.86 | -0.00035 | |

| 20230329 | 4027.81 | 0.014237 | 20230629 | 4396.44 | 0.004474 | |

| 20230330 | 4050.83 | 0.005715 | 20230630 | 4450.38 | 0.012269 | |

| 20230331 | 4109.31 | 0.014437 |

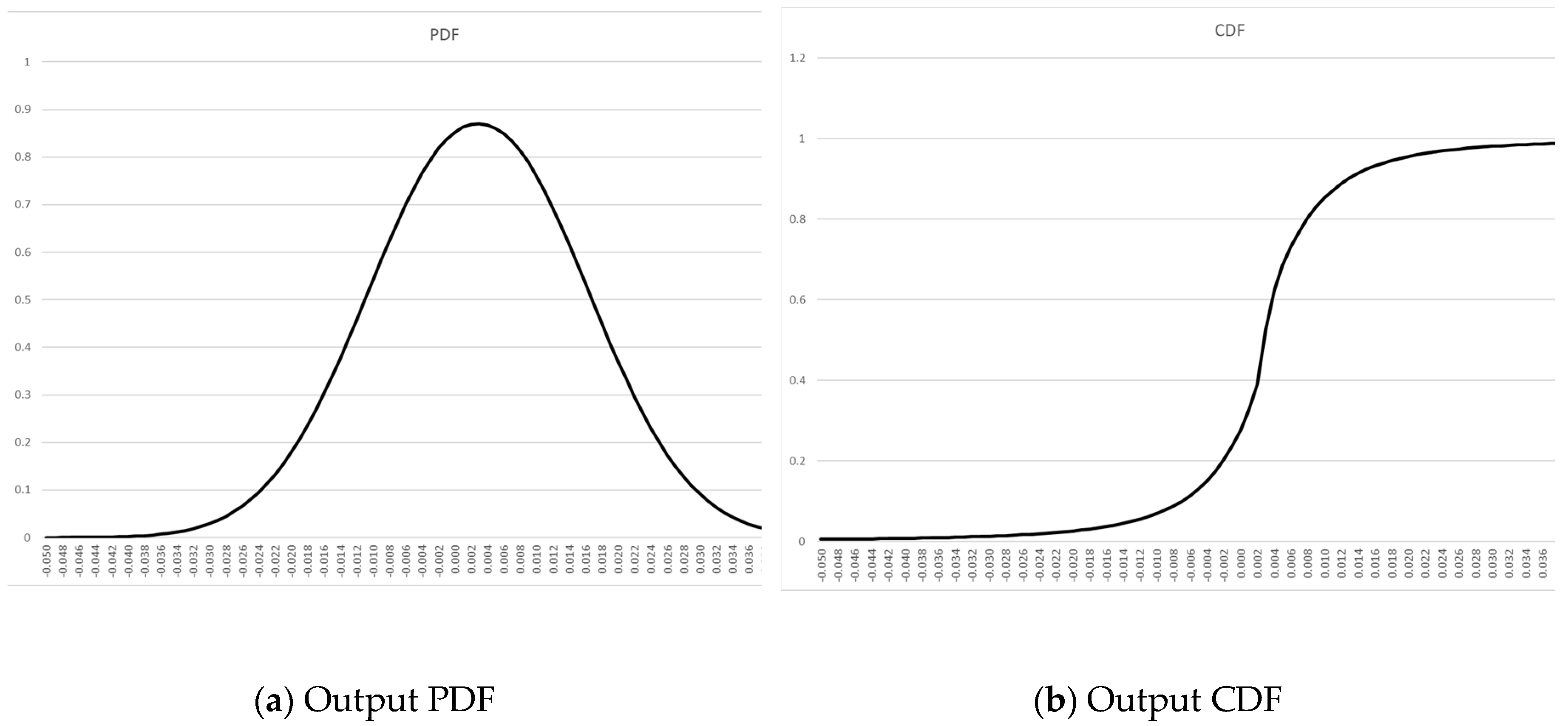

| Name | Values | |

|---|---|---|

| α | concentration | 2.1 |

| δ | scale | 0.01053813 |

| μ | location | 0.0029048 |

| λ | shape | 1.64940218 |

| 1 | It is this author's contention that Kelly and Shannon (who signed off on [16]) would have caught this oversight (they would not have intentionally opted to make the application scope of this work knowingly less general) had the absolute value of worst-case not simply been unity, thus cloaking it. |

| 2 |

n.b. In the characteristic function provided in the paper by Klebanov and Rachev (1996), t is a variable used to represent the argument of the characteristic function. It is not the same as , which is a variable used to represent the value of the random variable being modeled by the GHD.

The characteristic function of a distribution is a complex-valued function that is defined for all values of its argument . It is the Fourier transform of the probability density function (PDF) of the distribution, and it provides a way to calculate the moments of the distribution and other properties, such as its mean, variance, and skewness.

In the case of the GHD, the characteristic function is given by:

The argument of the characteristic function is a complex number that can take on any value. It is not the same as the value of the random variable being modeled by the GHD, which is represented by the variable . The relationship between the characteristic function and the PDF of the GHD is given by the Fourier inversion formula:

|

| 3 | These are often expressed as d0/d1 – 1, where d0 represents the most recent data, d1 the data from the previous period. In the case of outputs of a trading approach, the divisor is problematic; the results must be expressed in log terms, in terms of a percentage change. Such results must be expressed therefore in terms of an amount put at risk to assume such results, which are generalized to largest potential loss. The notion of "potential loss" is another Pandora's box worthy of a separate discussion. |

| 4 |

In actual implementation, we would use the full, non-symmetrical GHD. Deriving the PDF from the characteristic function of the GHD:

Starting with the characteristic function of the GHD:

Using the inversion formula to obtain the PDF of the GHD:

Substituting the characteristic function into the inversion formula and simplifing:

4. Changing variable :

5. Using the identity to simplify the integral:

This is the full PDF with the skewness parameter (γ) for the GHD.

The integral required to compute the CDF(x) of the GHD with skewness (γ) does not have a closed-form solution, so numerical methods must be used to compute the CDF(x). However, there are software packages such as R, MATLAB, or SAS that have built-in functions for computing the CDF(x) of the GHD. Once the CDF(x) is computed, the inverse CDF(x) can be obtained by solving the equation for , where is a probability value between 0 and 1. This equation can be solved numerically using methods such as bisection, Newton-Raphson, or the secant method. Alternatively, software packages such as R, MATLAB, or SAS have built-in functions for computing the inverse CDF of the GHD.

|

| 5 | This theorem states that, under certain conditions, the expected value of a martingale at a stopping time is equal to its initial value. A martingale is a stochastic process that satisfies a certain property related to conditional expectations. The Optional Stopping Theorem is an important result in probability theory and has many applications in finance, economics, and other fields. The theorem is based on the idea that, if a gambler plays a fair game and can quit whenever they like, then their fortune over time is a martingale, and the time at which they decide to quit (or go broke and are forced to quit) is a stopping time. The theorem says that the expected value of the gambler's fortune at the stopping time is equal to their initial fortune. The Optional Stopping Theorem has many generalizations and extensions, and it is an active area of research in probability theory. |

| 6 | In a European casino, he would have a better probability as there is only one green zero, and his probabilities therefore increase to 24/37, or approximately 64.9%. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).