1. Introduction

The prevention of communicable diseases and infections is key for overall population health and safety, especially in susceptible populations such as patients [

1]. The prevention and containment of viruses and infections have been of elevated attention during the current COVID-19 pandemic [

2]. Especially in hospital settings, many attempts were taken to ensure effective hand hygiene behavior of patients and healthcare professionals to reduce healthcare associated infections [

3]. It was proven that hand hygiene behavior is a cost-effective way of reducing COVID-19 morbidity and accepted as crucial strategy to prevent the spread and transmission of COVID-19 in healthcare facilities such as hospitals [

4,

5]. Since still relatively little is known about patients’ hand hygiene behavior in hospitals, the aim of this study was to examine patients’ hand hygiene and its determinants [

6,

7]. This is especially important as many patients are oftentimes not sufficiently aware that they can actively participate in hand hygiene and thus protect themselves, and others, from infections. It is, however, crucial to understand barriers towards a good hand hygiene in hospitals in detail in order to effectively increase compliance [

8].

In comparison to other preventative measures, especially hygiene behaviors, maintenance of hand hygiene behavior has been rather low, thus, calling for a better understanding of the reasons for the lack of performance and maintenance [

9]. Even though individuals are often motivated to change their behavior, this initial motivation or intention does not always translate into an actual behavior change due to the intention-behavior gap [

10]. Furthermore, it has been shown that even if a desired health behavior, such as hand hygiene behavior, is acquired, individuals may experience difficulties in maintaining this behavior over time and in face of difficulties. This may result in a relapse to old behavioral habits or patterns [

11]. As the regulations to stop or prevent the spread and transmission of the COVID-19 virus have been introduced by the government, individuals were required to change or alter their behavior over a considerable time [

12]. Several theories of social cognition have been used to provide an understanding of determinants of health-related behaviors such as hand hygiene behavior. The theory of planned behavior (TPB) as a classical and fundamental health behavior theory [

13] and the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change (TTM) have widely been used to explain and predict health behaviors [

14]. One of the main criticisms of those theories is, however, that they neglect or struggle to address the intention-behavior gap. Therefore, it has been suggested that those traditional models needed to be expanded to include a volitional phase in which individuals develop actions after having formed an intention. The Health Action Process Approach (HAPA) is an example of a theoretical behavior change model that includes both motivational and volitional phases. The HAPA has been known as a well-established theoretical framework that describes behavior changes by means of modelling social-cognitive determinants of behavior [

15]. One important determinant is the intention to change, which is determined by positive and negative outcome expectancies, belief in one’s ability to perform the behavior (action self-efficacy) and acknowledgement of being at risk for not behaving in the healthy way (risk perception). If the intention is high, self-regulatory skills and planning on when, where, and how to perform the desired behavior as well as having the belief that the individual is able to engage in the desired behavior despite possible adversities (coping self-efficacy) determine action initiation. To maintain the health behavior, individuals need to be confident in their ability to sustain the behavior (maintenance self-efficacy) and need to monitor their behavior (action control) to prevent relapse [

15,

16,

17].

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the burden on the mental health of individuals. As a result, individuals have reported an increase in perceived distress, anxiety, and symptoms associated with depression or loneliness [

18,

19]. However, the questions as to whether those individuals have adapted their hygiene behaviors need further analyses. Literature has shown that mental health and compliance to recommended preventive behaviors were associated with one and another, thus creating a feedback loop [

20,

21]. Further, evidence examining anhedonic depression in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic has shown an association between depression and precautionary behaviors, i.e., that depressive symptoms can be a barrier of effective precautionary behaviors [

22]. Furthermore, it has been shown that anhedonia has been frequently linked to poorer physical health outcomes, which may be explained by reduced self-care behaviors and self-regulatory strategies [

23,

24]. In addition, a decreased mental health status during the COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with more difficulties in adhering to health-related behaviors over a longer period of time [

25]. Previous studies have shown that with regard to symptoms of depression, motivational deficits were associated with a reduced intention to engage in health behaviors [

26]. Also, depressive symptoms have been associated with a decrease in self-efficacy and an increase in negative outcome expectations. Depressive individuals have also shown volitional deficits as they were less able to transform intentions into actions and showed reduced planning and maintenance self-efficacy capabilities [

27]. According to these findings, it may be assumed that depressive patients may display reduced intentions to engage in effective hand hygiene decisions.

Despite the previous findings that mental health might be associated with deficits related to the social-cognitive variables, and consequently health behavior and outcomes, these associations have rather rarely been examined with regard to hand hygiene behavior. Thus, the present study will investigate whether hand hygiene decisions can be explained by a health behavior theory, namely the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA; [

10,

28]), and whether the pattern of the HAPA is invariant for mental health of the study participants.

Few studies such as the one by Gaube et al. [

1] aimed to evaluate the hand hygiene behavior of patients, specifically by applying the HAPA model with inconclusive results. Self-efficacy, action control, and planning were not able to fully bridge the intention-behavior gap. Therefore, this study aims to validate previous studies on precautionary behaviors by examining the potentially important role of planning in overcoming the intention-behavior gap in hand hygiene. In addition, previous studies have not acknowledged the possible association between mental health and preventative measures (i.e., hand hygiene) in the context of the HAPA. Therefore, the current study will evaluate the HAPA determinants in the context of hand hygiene while acknowledging the role of symptoms of depression and anxiety, therefore examining invariance of the HAPA model for mental health.

In a first study, the fit of the HAPA model to hand hygiene data will be evaluated with mental health as a moderating covariate to see whether mental health will add additional variance to hand hygiene decisions beyond social-cognitive variables. In a second study, the role of mental health for the change of compliance in individuals with a pre-existing vulnerability (i.e., psychosomatic rehabilitation patients) will be evaluated in a longitudinal design. These vulnerable individuals have revealed motivational and adherence problems concerning health behaviors; thus, it is important to test whether the HAPA is robust for such potential differences. It is assumed that as psychosomatic rehabilitation patients receive behavior change interventions during their treatment, they will be more motivated to engage in hand hygiene behavior over time. Therefore, the following research questions will be tested in study 1: (a) Is the HAPA model applicable to hand hygiene decisions in patients? (b) Does a structural equation model, specified in terms of the social-cognitive variables of the HAPA, fit the data? (c) To what extend are hand hygiene decisions and its social-cognitive determinants invariant for mental health? Study 2 examined the research question: (d) Is mental health predictive of a change in hand hygiene compliance rates?

4. Discussion

The current study aimed to evaluate, as part of study 1, whether the theoretical structure of the HAPA model with its social-cognitive variables predicting health behavior can be fitted to hand hygiene decisions and whether the model is invariant for mental health (i.e., symptoms of depression and anxiety). Study 1 especially investigated whether planning was able to bridge the intention-behavior gap. Our results support the hypothesis evaluating interrelations between all HAPA variables and hand hygiene decisions: all variables (except for risk perception) were positively correlated with each other. Risk perception was negatively correlated with action self-efficacy, intention, maintenance self-efficacy, planning, and hand hygiene behavior as predicted.

With regard to whether the HAPA fitted the data well, the first attempt revealed a poor fit according to commonly accepted fit indices [

43]. This, however, is not surprising as models with a good fit found in literature often are incomplete and do not include all of the HAPA constructs [

28,

44].

The final attempt to fit the HAPA model to the data after iterative changes revealed significant paths and acceptable fit indices. Still, the latest model needs to be treated with caution as the model fit was not strong according to the RMSEA [

45]. However, like Kenny et al. [

46] suggested, sample size and degrees of freedom also need to be looked at when interpreting RMSEA. Hence, models with small sample sizes and low degrees of freedom tend to display an elevated RMSEA. Therefore, taking all fit indices into consideration, we can assume that the proposed model fits our data. This is in line with the literature as the HAPA model has been used previously to explain healthcare workers’ hand hygiene as well as to inform successful interventions [

47]. In a recent study, Gaube et al. found that the HAPA model could explain patients’ and visitors’ hand hygiene [

1]. Hence, based on previous evidence, it seems that hand hygiene behavior is a health behavior developing in a dynamic process that is fairly similar between patients with limited or good mental health. Therefore, as expected, the process of performing hand hygiene along the HAPA may be described as follows: In the motivational phase, outcome expectancies and action self-efficacy were associated with intention.

These results indicate that improving beliefs about the beneficial effects of performing good hand hygiene might be promising when motivating patients to become more active concerning their hand hygiene. Contrary to the hypothesized structure of the HAPA, risk perception was not associated with intention. Risk perception does not seem to be significantly associated with the intention to practice good hand hygiene in the context of the HAPA model. This is in line with other studies in the area of physical activity [

48,

49]. These last findings have suggested that risk perception may not be sufficient to form an actual intention to change health behavior [

15] and may instead be a distal predictor of hand hygiene behavior [

33].

However, for effective maintenance and performance to occur, necessary self-regulatory strategies, such as planning, need to be developed and maintained in the volitional stage. It has been assumed that planning bridges the intention-behavior gap, thus ensuring maintenance of hand hygiene. Similar to the results by Gaube et al. [

1], our results have shown a direct link between intention and the desired behavior. However, their study lacks results regarding the mediating effect of planning. Hence, the present study is the first to show that, for hand hygiene behavior of patients to be maintained, planning has the function to bridge the intention-behavior gap. Nevertheless, the present study did not include or acknowledge other self-regulatory skills, automatism, and action control as part of this study. Hence, integrating those variables should be regarded in future research.

Validating the HAPA as a generic framework in explaining social-cognitive processes of hand hygiene decisions invariant for mental health is in line with previous studies examining compliance to hand hygiene behavior in the general population, as well as in psychosomatic rehabilitation patients. Prior research indicates that both groups of participants display good hand hygiene behavior when either possessing greater fear of an infection or being more susceptible to anxiety [

50,

51]. In addition, the systematic review by Farholm and Sørensen [

26] suggested no differences in motivational mechanisms between the normal population and individuals with mental illnesses.

Finally, as part of study 2, we aimed to investigate whether symptoms of depression and generalized anxiety were predictive of a change in compliance in hand hygiene decisions in psychosomatic rehabilitation patients. Our results indicated that neither symptoms of depression nor generalized anxiety were predictive of a change in compliance. Firstly, these findings confirm results from the general population that compliance with hand hygiene behavior is independent of mental health status [

51]. However, previous researchers assumed that a reduced mental health status would be associated with a poorer compliance in hand hygiene behavior and that psychosomatic rehabilitation treatments would encourage health behavior change in patients. The present results do not support these assumptions. Possibly, hand hygiene is a rather stable construct irrespective of mental health status. For example, individuals who were compliant with hand hygiene behavior prior to the pandemic also were compliant during the pandemic and vice versa [

52], which may also explain the absence of any differences based on the two data collection points (see

Appendix B). Therefore, non-compliant individuals need to be encouraged to perform adequate hand hygiene. One way to do so may be to implement interventions that foster planning and self-efficacy measures, helping to overcome the intention-behavior gap where needed [

47]).

The study was subjected to several limitations. All variables examining hand hygiene decisions within the general population were (retrospective) self-report measures collected at one point in time. This was done to validate previous research (e.g., [

44]) and to assess data during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, recall bias and social desirability need to be considered when interpreting participants’ responses. To overcome this limitation, the handwashing behavior of patients should be observed by trained observers or tracked by technical devices. Still, even with testing for differences in time between hospitalization and participation in the survey (with regard to the self-reporting of hand hygiene behavior), no significant differences were found. This suggests that even though self-reporting biases and social desirability should be acknowledged, reported hand hygiene decisions have remained stable. Additionally, mental health was examined by a validated questionnaire but not via a diagnosis according to the International Classification of Disease (ICD-10) manual. Furthermore, mental health symptoms might have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., through increasing uncertainty, reduced social contacts). Hence, the expression of depressive symptoms, or symptoms of generalized anxiety, may be confounded by the current situation and should be considered in future research.

A further methodological limitation may be that study 1 used data from a cross-sectional study to investigate hand hygiene processes in the general population. Using structural equation modeling on cross-sectional data does not reflect the dynamic nature of underlying processes over time and thus violates model assumptions. However, testing for differences in depression and generalized anxiety has shown no significant differences across the two timepoints of measurement, suggesting relatively stable constructs irrespective of situational context. It is recommended that future research should validate the results from the trimmed HAPA-model in the form of a prospective or experimental study (i.e., a randomized controlled trial) to determine causal effects conclusively. Prospective behavioral measures, especially of the main outcome of hand hygiene decisions, should be applied.

Another limitation is that only a few participants with symptoms of depression and generalized anxiety could be included in this study from the general population, thus, compromising the statistical power. Nevertheless, the findings of this cross-sectional study and longitudinal examination can contribute to the understanding of the current state of hand hygiene adherence of patients and provide a basis for designing interventions to improve psychological aspects related to hand hygiene.

Results indicate that encouragement for the patients, regardless of their mental health status, to create hand washing plans for specific situations should be considered when designing interventions. In this regard, digital tools could be employed to function as reminders of plans and past successes. The present results indicate that social-cognitive variables and self-regulatory processes are necessary determinants for effective hand hygiene behavior. Therefore, to make patients more aware of the necessity and to support them by reducing the need for self-regulatory processes, hospitals should be encouraged to promote hand hygiene behavior throughout the healthcare facilities with visible posters or dispensers at accessible and visible locations as shown in studies by Hobbs et al. [

53].

To increase the intention to perform hand hygiene behavior, visual, auditory, and dynamic videos should be employed to encourage patients to clean their hands which has shown to be effective in other hospitals [

54]. Furthermore, individuals should be better informed about the potential risks associated with reduced hand washing behavior and compliance. Literature has shown that, in general and irrespective of mental health status, individuals report more compliance if they are aware of the potential risks [

51]. Hence, communication in the public media and in hospitals (i.e., on leaflets or posters) needs to be clearer and more objective while focusing on the risks.

Appendix A. Questionnaire and items used

Risk perception – cross-sectional

| |

significantly below average |

below average |

rather below average |

average |

rather above average |

above average |

significantly above average |

| Compared to an average person of my gender and age, my risk of getting an infection from poor hand hygiene is… |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Action self-efficacy – cross-sectional

| I am sure that I can regularly wash and disinfect my hands, even if... |

Completely not applicable |

Not applicable |

Rather not applicable |

Rather applicable |

Applicable |

Completely applicable |

| ... I have to force myself to do it. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ... it is time-consuming. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ... others do not wash their hands. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| … even if my hands get dry. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

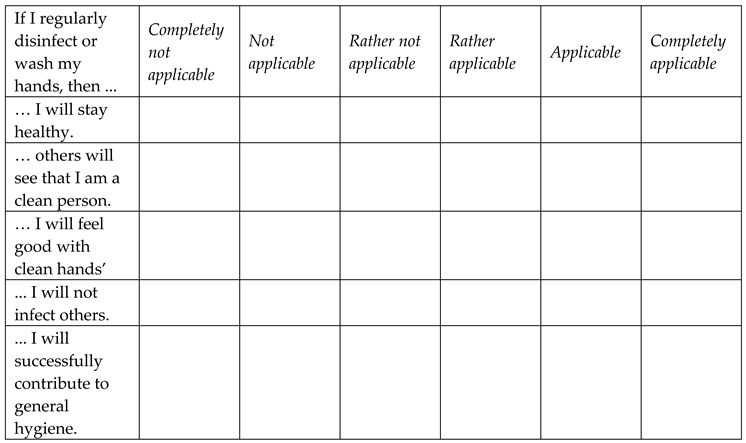

Outcome expectancies – cross-sectional

Intention – cross-sectional

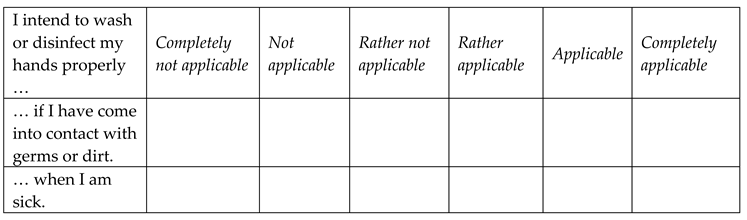

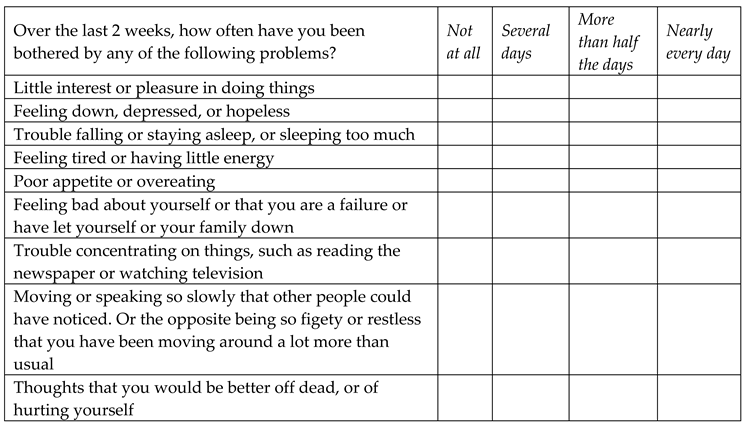

Action planning – cross-sectional

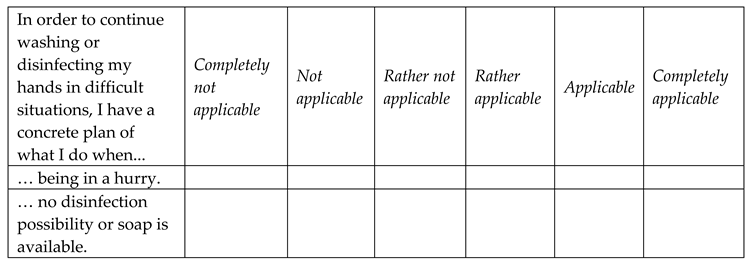

Coping planning – cross-sectional

Maintenance self-efficacy – cross-sectional

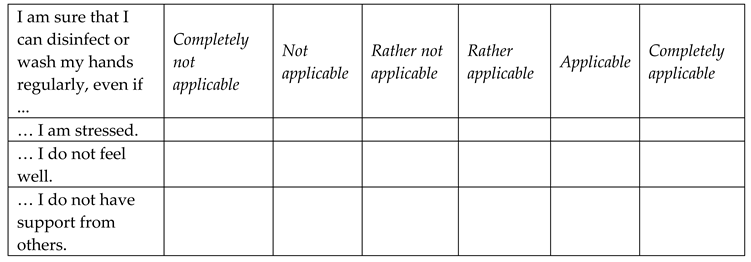

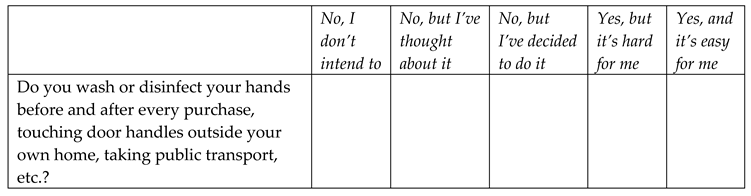

Hand hygiene behavior – cross-sectional

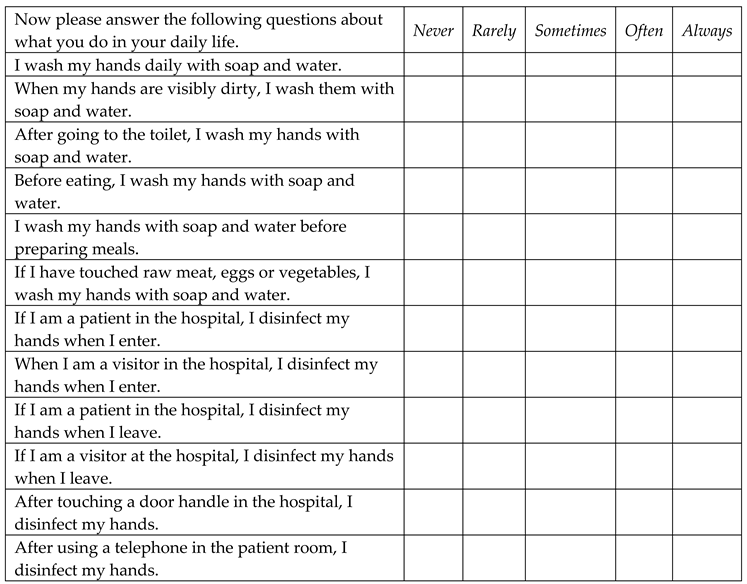

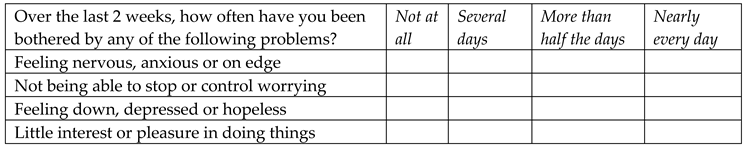

PHQ-9 (Depression) – cross-sectional

GAD-7 (Anxiety) – cross-sectional

Hand hygiene behavior stage item – longitudinal

PHQ-4 (Depression and Anxiety) – longitudinal

Appendix B. Difference between participants from the three measurement waves

To examine differences in participants across the three measurement waves, chi-square analyses and analyses of variance were performed. The results showed no significant differences with respect to symptoms of depression χ²(2, n=248)=0.08 and for symptoms of generalized anxiety controlling for age and gender. In addition, no significant differences between the three waves were found with regard to the HAPA variables: outcome expectancies F(2, 266)=1.07, p=.34, ηp2=.02, risk perception F(2, 266)=1.75, p=.18, ηp2=.01, action self-efficacy F(2, 266)=2.76, p=.06, ηp2=.02, intention F(2, 278)=2.49, p=.07, ηp2=.02, maintenance self-efficacy F(2, 266)=1.79, p=.17, ηp2=.03, and planning F(2, 278)=3.00, p=.51, ηp2=.02 controlling for age and gender. In addition, no significant differences were found with regard to hand hygiene behavior between the three measurement waves F(2, 266) =0.45, p=.64, ηp2=.01.However, results revealed to be significant with regard to resources F(2, 266)=15.08, p<.01, ηp2=.10 and support F(2, 266)=13.67, p<.01, ηp2=.10 while controlling for the covariates age and gender.

Appendix C. Differences in variables with regard to time of hospital visit.

In order to control for time differences with regard to hospital visit as either an inpatient or an outpatient, variables related to the HAPA model as well as hand hygiene behavior and mental health related symptoms were examined for significant differences. No significant differences were revealed for the following variables: hand hygiene behavior, F(2, 266)=2.67, p=.07, ηp2=.02, action self-efficacy, F(2, 266)=2.37, p=.10, ηp2=.02, risk perception F(2, 266)=1.13, p=.32, ηp2=.01, outcome expectancies, F(2, 266)=0.29, p=.75, ηp2=.01, intention F(2, 266)=0.06, p=.94, ηp2=.01, maintenance self-efficacy, F(2, 266)=0.30, p=.74, ηp2=.01, planning, F(2, 266)=0.51, p=.60, ηp2=.01, resources, F(2, 266)=3.04, p=.54, ηp2=.02, and support F(2, 266)=.73, p=.48, ηp2=.01, symptoms of depression, F(2, 237)=0.49, p=.61, ηp2=.01, and symptoms of generalized anxiety, F(2, 246)=2.50, p=.08, ηp2=.02 controlling for age and gender.

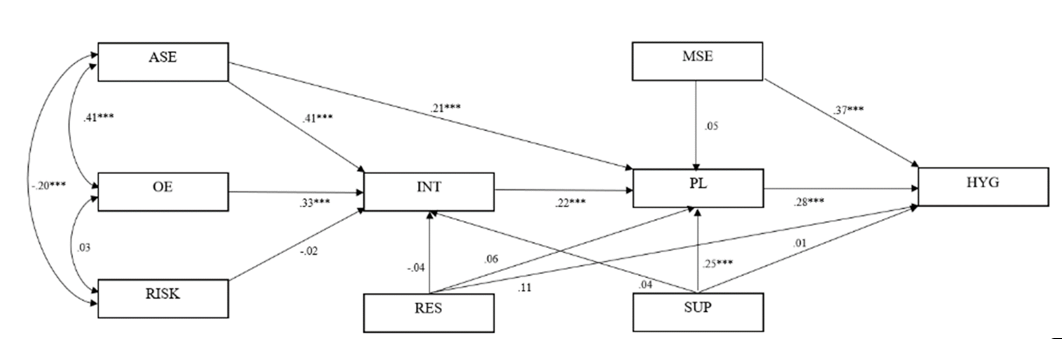

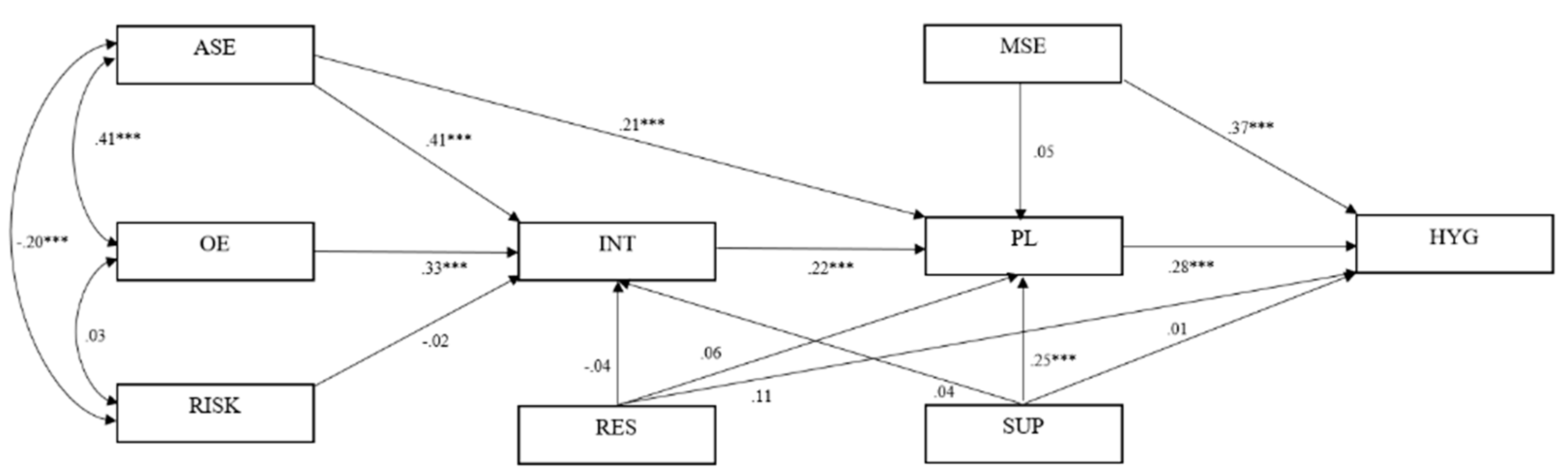

Figure 1.

Structural equation modeling of the full Health Action Process Approach. Note. HAPA variables: ASE=Action Self-Efficacy; OE=Outcome Expectancies, RISK=Risk Perception; INT=Intentions; MSE=Maintenance Self-Efficacy; PL=Planning, RES=Resources, SUP=Social Support, HYG=Hand Hygiene Decisions; N=279; Intention R²=39.5%; Planning R²=19.8%; Hand Hygiene R²=21.6%. The values reported represent the standardized estimates of each path in the model. Significant path at ***p<.001, **p<.01, *p<.05.

Figure 1.

Structural equation modeling of the full Health Action Process Approach. Note. HAPA variables: ASE=Action Self-Efficacy; OE=Outcome Expectancies, RISK=Risk Perception; INT=Intentions; MSE=Maintenance Self-Efficacy; PL=Planning, RES=Resources, SUP=Social Support, HYG=Hand Hygiene Decisions; N=279; Intention R²=39.5%; Planning R²=19.8%; Hand Hygiene R²=21.6%. The values reported represent the standardized estimates of each path in the model. Significant path at ***p<.001, **p<.01, *p<.05.

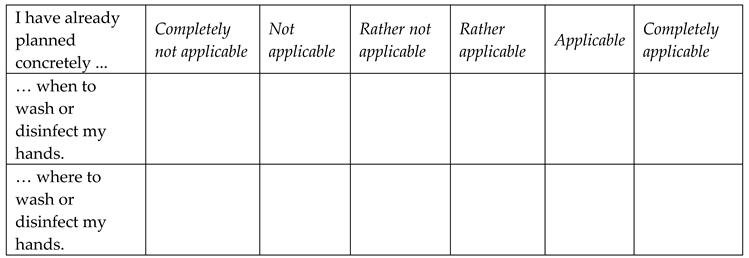

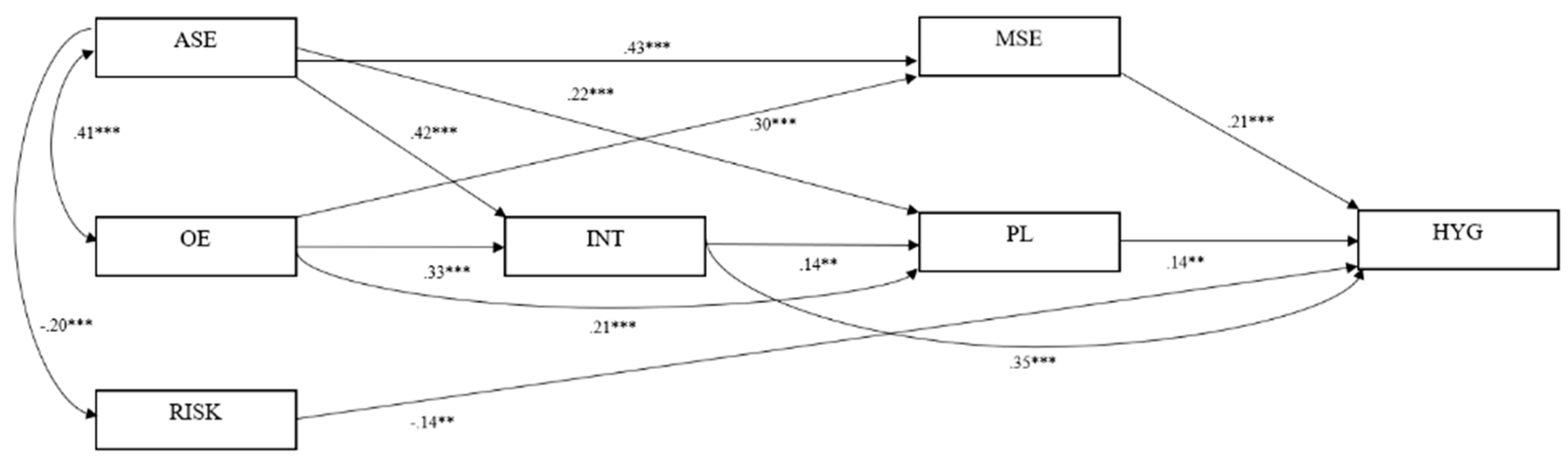

Figure 2.

Structural equation modeling of the trimmed Health Action Process Approach. Note. HAPA variables: ASE=Action Self-Efficacy; OE=Outcome Expectancies, RISK=Risk Perception; INT=Intentions; MSE=Maintenance Self-Efficacy; PL=Planning; HYG=Hand Hygiene Behavior; N=279; Intention R²=39.3%; Planning R²=23.5%; Hand Hygiene R²=33.2%. The values reported represent the standardized estimates of each path in the model. Age, gender, depressive symptoms, and symptoms of generalized anxiety were included as covariates. Significant path at ***p<.001, **p<.01, *p<.05. .

Figure 2.

Structural equation modeling of the trimmed Health Action Process Approach. Note. HAPA variables: ASE=Action Self-Efficacy; OE=Outcome Expectancies, RISK=Risk Perception; INT=Intentions; MSE=Maintenance Self-Efficacy; PL=Planning; HYG=Hand Hygiene Behavior; N=279; Intention R²=39.3%; Planning R²=23.5%; Hand Hygiene R²=33.2%. The values reported represent the standardized estimates of each path in the model. Age, gender, depressive symptoms, and symptoms of generalized anxiety were included as covariates. Significant path at ***p<.001, **p<.01, *p<.05. .

Table 1.

Correlations between Health Action Process Approach (HAPA) constructs, hand hygiene decisions, and mental health status of N=279 participants.

Table 1.

Correlations between Health Action Process Approach (HAPA) constructs, hand hygiene decisions, and mental health status of N=279 participants.

| |

α |

M |

SD |

ASE |

OE |

RISK |

INT |

MSE |

PL |

RES |

SUP |

HYG |

DEP |

ANX |

| ASE |

.87 |

19.13 |

4.28 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| OE |

.83 |

24.61 |

3.83 |

.41** |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| RISK |

-1 |

3.16 |

1.33 |

-.20** |

.03 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| INT |

.68 |

10.04 |

1.87 |

.55** |

.50** |

-.08 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MSE |

.91 |

19.58 |

3.99 |

.56** |

.48** |

-.08 |

.55** |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PL |

.86 |

12.43 |

5.34 |

.40** |

.38** |

-.14** |

.40** |

.28* |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

| RES |

.81 |

20.28 |

5.03 |

.27** |

.34** |

.03 |

.21** |

.26** |

.16** |

- |

|

|

|

|

| SUP |

.92 |

5.82 |

3.15 |

.27** |

.30** |

.05 |

.24* |

.06 |

.33** |

.44** |

- |

|

|

|

| HYG |

.87 |

48.12 |

7.98 |

.39** |

.32** |

-.20** |

.52** |

.44** |

.36** |

.22** |

.12* |

- |

|

|

| DEP |

.86 |

5.89 |

4.75 |

-.08 |

-.03 |

-.04 |

.01 |

-.03 |

.01 |

-.12 |

-.07 |

-.07 |

- |

|

| ANX |

.85 |

4.70 |

3.82 |

-.08 |

-.03 |

-.08 |

.03 |

-.10 |

.01 |

-.05 |

-.10 |

-.01 |

-.48** |

- |

Table 2.

Model fit indices for the unrestricted model, the semi-restricted model, and the fully restricted model for the multi-group mental health status model for individuals below and above the symptom threshold for depression (N=279).

Table 2.

Model fit indices for the unrestricted model, the semi-restricted model, and the fully restricted model for the multi-group mental health status model for individuals below and above the symptom threshold for depression (N=279).

| Indices |

Unrestricted model |

Semi-restricted model |

Fully restricted mode |

| χ2– Test of model fit |

40.49 |

51.77 |

63.15 |

| df |

16 |

12 |

27 |

| χ2

|

p<.01 |

p<.01 |

p<.05 |

| CFI |

.94 |

.94 |

.95 |

| TLI |

.85 |

.92 |

.95 |

| Model 1 Delta TLI |

- |

-.07 |

-.09 |

| RMSEA (90% CI) |

.08 |

.06 |

.04 |

Table 3.

Model fit indices for the unrestricted model, the semi-restricted model, and the fully restricted model for the multi-group model of individuals below and above the symptom threshold for generalized anxiety (N=279).

Table 3.

Model fit indices for the unrestricted model, the semi-restricted model, and the fully restricted model for the multi-group model of individuals below and above the symptom threshold for generalized anxiety (N=279).

| Indices |

Unrestricted model |

Semi-restricted model |

Fully restricted model |

| χ2 – Test of model fit |

29.75 |

40.63 |

63.80 |

| df |

16 |

12 |

27 |

| χ2

|

p=.020 |

p=.062 |

p=.013 |

| CFI |

.97 |

.97 |

.97 |

| TLI |

.92 |

.95 |

.95 |

| Model 1 Delta TLI |

- |

-.03 |

-.03 |

| RMSEA (90% CI) |

.06 |

.04 |

.04 |

Table 4.

Latent Mean Analysis: Mean estimates, standard error, and critical ratio (N=279).

Table 4.

Latent Mean Analysis: Mean estimates, standard error, and critical ratio (N=279).

| |

ASE |

OE |

RISK |

INT |

MSE |

PL |

HYG |

|

With symptoms of depression in comparison to the reference group without depressive symptoms |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mean estimate (ME) |

-0.194 |

-0.090 |

-0.137 |

0.049 |

-0.239 |

0.050 |

0.016 |

| Standard error (SE) |

0.163 |

0.126 |

0.238 |

0.154 |

0.150 |

0.282 |

0.018 |

| Critical ratio (CR) |

-1.252 |

-0.715 |

-0.576 |

0.320 |

-1.159 |

0.177 |

0.907 |

| p |

.233 |

.475 |

.565 |

.749 |

.110 |

.859 |

.365 |

|

With symptoms of anxiety in comparison to the reference group without symptoms of anxiety |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mean estimate (ME) |

-0.227 |

-0.102 |

-0.310 |

0.068 |

-0.072 |

0.127 |

-0.043 |

| Standard error (SE) |

0.212 |

0.136 |

0.242 |

0.176 |

0.168 |

0.294 |

0.029 |

| Critical ratio (CR) |

-1.073 |

-0.752 |

-1.280 |

0.384 |

-0.429 |

0.433 |

-1.466 |

| p |

.283 |

.452 |

.201 |

.701 |

.668 |

.665 |

.143 |

Table 5.

HAPA stage distributions and changes of the longitudinal sample (N=1,058).

Table 5.

HAPA stage distributions and changes of the longitudinal sample (N=1,058).

| Time 2 (after rehabilitation) |

|---|

| |

|

Non-compliance |

Compliance |

Total |

| Time 1 |

Non-compliance |

25 (45.46) |

30 (54.54) |

55 (100) |

| Compliance |

47 (4.69) |

956 (95.31) |

1003 (100) |

| |

|

|

|

Table 6.

Summary of results from the binary logistic regression analysis and descriptive data for mental health variables and control variables predicting changes in compliance in hand hygiene decisions (n=71).

Table 6.

Summary of results from the binary logistic regression analysis and descriptive data for mental health variables and control variables predicting changes in compliance in hand hygiene decisions (n=71).

| Predictors |

Wald |

OR |

95% CIOR

|

p -Value |

Remaining in baseline compliance |

Change in compliance |

| M |

SD |

M |

SD |

| Change in compliance: remaining non-compliant (0) versus progression (1) |

| Depression |

1.03 |

1.36 |

0.75-2.48 |

.31 |

2.79 |

1.14 |

3.27 |

1.89 |

| Anxiety |

0.32 |

0.84 |

0.45-1.57 |

.58 |

2.84 |

1.25 |

3.10 |

1.69 |

| Change in compliance: remaining compliant (0) versus regression (1) |

| Depression |

1.14 |

1.15 |

0.89-1.48 |

.29 |

3.45 |

1.66 |

3.83 |

1.61 |

| Anxiety |

0.05 |

0.97 |

0.75-1.26 |

.84 |

3.61 |

1.67 |

3.82 |

1.35 |