1. Introduction

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is a cAMP-dependent member of the large superfamily of ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporters, characterized by four canonical domains, two transmembrane domains (TMDs) and two cytosolic nucleotide-binding domains (NBDs). The main physiologic permeants transported by CFTR are chloride (Cl-) and bicarbonate (HCO3-) anions.

CFTR pore opening and closing (gating) rely on the intramolecular dimerization and dissociation of the NBDs. The former process is promoted by the binding of two ATP molecules, which remain sealed inside the NBD1-NBD2 interface, while the latter follows ATP hydrolysis stimulated by the CFTR intrinsic ATPase activity [

1].

In the closed channel, the transmembrane (TM) helices are tightly assembled on the extracellular side and gradually spread apart while traversing the membrane and protruding into the cytoplasm as intracellular loops (ICLs)(

Figure 1). The ICls are associated in two distinct intramolecular dimers, ICL1/ICl4 and ICL2/ICL3, respectively making contact with NBD1 and NBD2. The dimerization of the NBDs promotes the coupling of the ICL1/ICl4 and ICL2/ICL3 dimers into a tetrameric helical bundle, which sparks further rearrangements in the TMDs finally enabling CFTR anion transport. CFTR also features a regulatory domain (R) that modulates the channel activity in a phosphorylation-dependent manner [

2]. NBD1-NBD2 dimerization is prevented by the intramolecular binding of the R domain to NBD1 and the ICLs, and this self-inhibition vanishes along with phosphorylation at various sites by protein kinase A [

3,

4,

5] and protein kinase C (PKC)[

6]. These post-translational modifications are thought to weaken the obstructive intramolecular interactions by the R domain. Intriguingly, NBD2 is not strictly necessary for channel opening as CFTR molecules lacking all or most the domain residues like the CFTR-Δ1198 construct, the nonsense mutant CFTR-W1282X [

7], and the CFTR-1248X construct [

8] present very low yet detectable chloride transport activity. Nevertheless, both NBDs as well as their dimerizing capability are required for full and ATP-regulated CFTR activation.

Chloride (Cl

-), the most abundant anion in the organism, exerts various physiological functions. Among these, the substantial transport of this anion across membranes to the cell surfaces, mediated by CFTR, elicits osmosis phenomena that move large water volumes that healthily hydrate epithelia. Therefore, mutations impairing the expression or activity of the CFTR channel are inevitably associated with the onset of viscous secretions abnormally persisting on the epithelia of various organs, especially lungs, pancreas, intestine and hepatobiliary ducts, which in turn promote bacterial proliferation, infections, obstructions and fibrosis. These clinical features represent the hallmark of cystic fibrosis (CF), a common autosomal recessive genetic disorder among Caucasians [

9]. Despite CF is fatal, life quality and expectancy of patients improved significantly through the decades with a more widespread diagnosis and improved symptomatic treatments [

10].

In the last few years, a number of small molecule drugs capable to bind and recover the function of a number of defective CFTR protein mutants, named modulators, were introduced in the clinic and also used in combination [

11]. The search of new modulators is still ongoing and the therapeutic arsenal against CF can be enriched also by various natural substances exhibiting CFTR modulation capability [

12,

13]. Interestingly, combinations of synthetic and natural modulators can act synergistically against CF holding promise in more options to improve the treatment of this disease [

14].

One natural CFTR modulator is curcumin, a compound present in turmeric, a spice traditionally used in Middle East and nowadays diffused around the world. Egan et al. [

15] first showed that curcumin corrects functional defects associated with the CFTR-ΔF508 mutation in mice. Subsequently, curcumin efficacy against CF was questioned in the aftermath of a number of contrasting experimental results. Nevertheless, discrepancies among various studies might have been caused by differences in the materials and methods employed, such as the genetics of mouse models, the mutations of patients, the pulmonary functions and responses monitored in the clinics, the treatment duration, and the curcumin source, preparation, storage, and dosing [

16]. As a matter of facts, a known major limitation in curcumin use is the achievement of therapeutic concentrations because this compound is characterized by very poor bioavailability [

17], low solubility and rapid degradation in neutral-basic aqueous solutions [

18]. Furthermore, curcumin presents tautomerism between the diketo and keto-enol forms with a solvent dependent equilibrium [

19,

20]. pH and temperature also regulate this tautomerism, influencing the aggregation propensity and in turn the absorption and bioavailability of curcumin [

21]. Thus, variations in the experimental setting affecting the complex molecular properties of curcumin can lead to reproducibility issues during the assessment of the compound efficacy against CF. Consequently, efforts were made to devise pharmacological formulations that improve bioavailability by delivering the compound more efficiently [

22]. For example, a clinical trial showed that children with CF who were administered curcumin nanoparticles presented significant improvement in the quality of life [

23].

Concerning the curcumin binding site in CFTR, its location unlikely overlaps with the site exploited by the synthetic drug ivacaftor, located in the TMDs within the lipid bilayer, as the natural and the synthetic modulator potentiate synergistically CFTR activity [

14]. Wang et al. [

7] proposed that curcumin interacts with the NBD1 domain following the observation that ATP strongly prevents curcumin-induced stimulation of channels lacking NBD2 and that this inhibition is blunted by the A462F mutation known to disrupt ATP-binding. The same authors also showed that curcumin markedly stimulates poorly active CFTR channels due to defects in ATP-binding and/or NBD1-NBD2 dimerization, like the CFTR-G551D mutant, and even channels lacking NBD2 like the nonsense CFTR-W1282X mutant and the CFTR−Δ1198 construct. Yet, these findings allow to exclude NBD2 as an exclusive binding target in curcumin-induced activation. Wang [

24] highlighted two independent curcumin-mediated potentiation mechanisms, one in which the ligand sequestrates the inhibitory Fe

3+ ions from phosphorylated CFTR, and the other in which it binds, as suggested by mutagenesis experiments, to or near Tyr161 and Lys166 (ICL1), and Arg1066 and Phe1078 (ICL4). It is worth noticing that all these four residues also happen to be near the interface formed by the parent ICLs with NBD1.

In this study, I employed docking and molecular dynamics (MD) to identify a possible curcumin binding site and propose a mechanism for the ligand-induced CFTR activation.

3. Discussion

The search of the mechanism through which curcumin activates CFTR requires to identify the location of the ligand binding site. It also poses the question on which would be the initial binding target between the closed CFTR and the spontaneously opened ATP-free form. While the latter possibility has a logic if curcumin can directly bind and stabilize pre-opened channels it can also be argued because for the rare and transient nature of these species. They can achieve only very low physiological concentrations and the same is true also for the very poorly bioavailable curcumin. It appears unlikely that they can encounter within the organism to form adequate amounts of functioning complexes. Nevertheless, the pharmacological effects of curcumin in CF are observable

in vivo and should also be mediated by direct interactions with CFTR. Since the closed channel levels are orders of magnitude higher than those of the spontaneously activated ATP-free channels, the former could be more plausible candidates as the initial binding targets of curcumin. Should this hold true, a foreseeable mechanism for the closed CFTR-bound curcumin would be the promotion of the active state and/or its stabilization after the open conformation takes place spontaneously. This would imply the presence of a site that efficiently holds curcumin in both CFTR closed and open conformations. The docking strategy here presented led to the identification of a binding site near the NBD1/ICL1/ICL4 interface. In the closed channel, this site lays in a solvent exposed groove, hence the ligand could leave it if the non-bonding attractive interactions are insufficient. In the open channel, the ligand is similarly bound to NBD1/ICL1/ICL4 but also sandwiched between the former region and NBD2/ICL2/ICL3. Thus, the ligand might remain entrapped in the protein cavity with no easy escape route to the outside environment. Indeed, several non-overlapping binding poses near the NBD1/ICL1/ICL4 interface were top scored by docking hence deemed favorable in both the closed and open CFTR prior to applying the filtering procedures (

Figure 4). Furthermore, while a mere entrapping effect between NBD1/ICL1/ICL4 and NBD2/ICL2/ICL3 could even constrain a ligand regardless its affinity for the site, the resulting protein-protein interface, which is also contributed by flexible loops, might undergo conformational changes causing substantial ligand rearrangements. Thus, either poor binding affinity for the closed CFTR or ligand rearrangements in the open CFTR would disprove the above made hypotheses and docking procedure. To assess the plausibility of the consensus binding mode and understand the possible mechanism of channel activation, I performed MD simulations of the curcuminoids placed in that position on the closed CFTR and open CFTR. At the end of the MD simulations all tested curcuminoids were still bound to the closed CFTR (

Figure 7). The ferulinic groups were engaged in bipartite interactions with two protein patches, one constituted mainly by NBD1 residues plus Trp1063 in ICL4, and the other by ICL1 and ICL4 residues. The linker of the two ferulinic groups was also interacted with ICL1 and ICL4 residues. Enol-curcumin and BSc3596 maintained their somehow linear shape, whereas the more flexible diketo curcumin underwent significant bending, yet still maintaining the interactions with the above two protein patches. Of note, the binding site in NBD1/ICL1/ICL4 is enriched in residues producing favorable contact with both ferulinic groups and the different linkers in the three curcuminoids. It also appears that the binding site can offer multivalent alternative stabilizing interactions allowing the ligand to rearrange yet without leaving the protein site. The MD simulations showed that also the curcuminoids complexed with the open CFTR remained stably bound to the protein (

Figure 8). Interestingly, the ligands maintained nearly same pose as in the structures kickstarting the simulations. Unraveling a possible activation mechanism from the ligand-protein geometries would support the plausibility of this binding model. To this purpose, I examined how the individual protein regions composing the site contributed to ligand binding by calculating their energies of interaction in MD snapshots taken at time intervals across the simulations. It can be seen that NBD1, ICL1, and ICL4 maintained favorable interactions with the curcuminoids bound to the closed CFTR, and, remarkably, while keeping these interactions also in the open CFTR, ICL2, ICL3, and NBD2 additionally concurred to the binding (

Figure 9). Thus, in the open CFTR, the curcuminoids undertook multiple simultaneous interactions with all above peptide regions (only ICL3 contributed minimally). This allows to propose as the mechanism of curcumin-induced activation the bridging of NBD1/ICL1/ICL4 and NBD2/ICL2/ICL3 once these regions approach each other by random domain motions. Thus, curcumin appears to reinforce the same interdomain associations that occur in ATP-bound and fully functioning active channels.

By comparing the energy of interactions of diketo curcumin and keto-enol curcumin with CFTR (

Figure 9), the latter appears to be bound stronger in both channel conformations. While, this might not suffice to exclusively endow keto-enol curcumin with the capacity to bind and activate CFTR, it must be added that only this curcumin tautomer has the electrophilic α,β-unsaturated carbonyl group (

Figure 3). This moiety is susceptible to Michael addition, a reaction involving the attack at the β carbon by nucleophilic groups such as the side chain of cysteine and serine (deprotonated forms), or lysine and histidine (unprotonated forms). Indeed, the formation of Michael addition covalent adducts between curcumin and CFTR has been reported [

25]. In the closed CFTR, a curcumin molecule hosted in the consensus binding site presents only one potential Michael nucleophile, Ser492, residing sufficiently close to the α,β-unsaturated carbonyl group of the ligand (

Figure 7). The Michael addition would be more likely in the open CFTR, because in this protein conformation additional nucleophile residues from NBD2 kick in. Among these, Cys1344, His1348, and Lys1351 place their nucleophile side chains in direct contact with the electrophilic group of curcumin (

Figure 8). In particular, the cysteine residue, in its anionic form, can be the most potent Michael nucleophile. Indeed, Cys1344 deprotonation to a thiolate can be assisted by the adjacent Asp1341. Thus, curcumin in the consensus binding site may undergo Michael addition reactions. This supports the observed curcumin-induced CFTR cross-linking and also suggests that keto-enol curcumin is the curcumin tautomer promoting CFTR activation. Together with the poor bioavailability, the Michael addition reaction is another factor limiting curcumin CFTR activation efficiency. Indeed, BSc3596 was purposedly designed to obtain a CFTR activator not susceptible to undesired Michael addition reactions through the replacement of the β diketone moiety of curcumin with the cyclic 1,2-oxazole group [

25]. This goal was achieved and the curcumin analogue was shown to potently activate wild-type CFTR, G551D-CFTR, and Delta1198-CFTR. The same chemical modification also constrains BSc3596 into a more rigid and linear shape with the two ferulinic groups pointing away from each other, which can additionally explain the potency of this curcuminoid. This geometry is more similar to that of keto-enol curcumin rather than diketo curcumin, further suggesting that keto-enol curcumin is the most efficient CFTR activator between the two natural curcumin tautomers.

Despite no atomistic level structural information on curcumin interactions with CFTR is available to date, biochemical studies provided hints on the possible binding location for this natural compound. Wang [

24] showed that mutagenesis of Tyr161, Lys166, Arg1066, and Phe1078 prevented the Fe

3+-independent curcumin-induced CFTR activation. Although the same author proposed that Lys166 and Arg1066 may form cation-pi interactions with curcumin aromatic rings, the results of the present study failed to support a direct contact between curcumin and any of the above four residues. Nevertheless, the binding site is not distant from the mutagenized amino acids, which are all important for the correct assembly of the ICL1 and ICL4 portions composing the putative curcumin binding site. Thus, the impairment of curcumin-induced CFTR binding/activation might have rather been the indirect result of the mutagenesis-associated conformational changes in the ICLs. Interestingly, it has been shown that curcumin also promotes the activation of CFTR mutants characterized by defective NBD1-NBD2 dimerization, or even lacking NBD2 [

7]. This highlights the ligand ability to skip the CFTR activation dependency from both ATP and NBD2. It also proves that the intramolecular dimerization of the NBDs is not strictly required for channel opening. Nevertheless, NBD dimerization is crucial for the implementation of the ATP-dependent regulation in CFTR. The NBD dimerization also works as a lever in the coupling of ICL1/ICL4 and ICL2/ICL3, which is followed by further TMD rearrangements finally enabling chloride transport. It can be reasonably assumed that the spontaneous activation of channels lacking NBD2 involve conformational changes in the TMDs similar to those of the wild type channels but short lived because not stabilized by the NBD dimerization. According to the curcuminoid binding mode proposed in this study, it is possible to infer that curcumin works by compensating the lack of NBD2 by bridging NBD1/ICL1/ICL4 and ICL2/ICL3, thus pulling and stabilizing the four ICLs into the same tetrahelical bundle sustaining the open conformation. Provided that CFTR mutations do not affect the binding site of curcuminoids, it is possible that these compounds can stimulate a large array of malfunctioning channel mutants, especially those with impaired or even impossible dimerization of the NBDs. The model for curcuminoid binding proposed in this work can be used in the design of CFTR modulators for these particular mutants.

5. Conclusions

In this study I propose that curcumin binds the closed CFTR near the interface formed by NBD1, ICL1, and ICL4. When the channel opens spontaneously with a pre-bound curcumin, this ligand, in addition to maintaining its contact with NBD1/ICL1/ICL4, simultaneously engages in interaction with NBD1, ICL2 and ICL3, finally bridging all protein domains and stabilizing the active channel configuration. This mechanism might explain curcumin ability to potentiate CFTR mutants characterized by defects in ATP binding and/or intramolecular dimerization of the NBDs.

Experimental validation is needed to confirm whether this binding mode reproduces the native binding of curcuminoids. Nonetheless, this model highlights a potentially exploitable mechanism of activation that can be triggered by drugging the NBD1/ICL1/ICL4 interface, and provides the basis for the design of novel activators of CFTR mutants characterized by subnormal NBD dimerization capability.

Figure 1.

Structures of the closed and open CFTR. Shown are the structures of and closed CFTR (PDB 5UAK) and open CFTR (PDB 6MSM) highlighting domains and ICLs with a schematic representation of activation.

Figure 1.

Structures of the closed and open CFTR. Shown are the structures of and closed CFTR (PDB 5UAK) and open CFTR (PDB 6MSM) highlighting domains and ICLs with a schematic representation of activation.

Figure 2.

NBD1/ICL1/ICL4 is conformationally invariant in the closed and open CFTR. Closed and open CFTR (respectively, PDB 5UAK and 6MSM, represented as backbone lines with the domains in different colors; the solved R domain fragment and bound ATP molecules are not shown). The conformationally invariant regions (highlighted by cartoons) are defined as those whose Cα atoms overlap within 2.5 Angstroms in the closed and open CFTR protein structures superposed relative to NBD1.

Figure 2.

NBD1/ICL1/ICL4 is conformationally invariant in the closed and open CFTR. Closed and open CFTR (respectively, PDB 5UAK and 6MSM, represented as backbone lines with the domains in different colors; the solved R domain fragment and bound ATP molecules are not shown). The conformationally invariant regions (highlighted by cartoons) are defined as those whose Cα atoms overlap within 2.5 Angstroms in the closed and open CFTR protein structures superposed relative to NBD1.

Figure 3.

Docking scheme. Curcuminoid structures (diketo curcumin, keto-enol curcumin; BSc3596) employed in docking and CFTR protein targets (ensembles of conformers of the open CFTR, open CFTR-ΔNBD2 construct, and closed CFTR; each ensemble included a parent PDB structure, PDB 6MSM for the open CFTR and the open CFTR-ΔNBD2, and PDB 5UAK for the closed CFTR, the energy minimized and ten MD simulation snapshots of the parent PDB structure; see methods). The parent PDB structures are portrayed and colored by domain (solved R domain fragment and ATP are not shown). The conformationally invariant regions (showing same conformation in the closed and open CFTR; please see the text) are highlighted by ribbons and the remainder of the structures as backbone atom lines. The space covered by the docking searches (transparent spheres) encompassed 33.0 Angstroms from the NBD1 center of mass.

Figure 3.

Docking scheme. Curcuminoid structures (diketo curcumin, keto-enol curcumin; BSc3596) employed in docking and CFTR protein targets (ensembles of conformers of the open CFTR, open CFTR-ΔNBD2 construct, and closed CFTR; each ensemble included a parent PDB structure, PDB 6MSM for the open CFTR and the open CFTR-ΔNBD2, and PDB 5UAK for the closed CFTR, the energy minimized and ten MD simulation snapshots of the parent PDB structure; see methods). The parent PDB structures are portrayed and colored by domain (solved R domain fragment and ATP are not shown). The conformationally invariant regions (showing same conformation in the closed and open CFTR; please see the text) are highlighted by ribbons and the remainder of the structures as backbone atom lines. The space covered by the docking searches (transparent spheres) encompassed 33.0 Angstroms from the NBD1 center of mass.

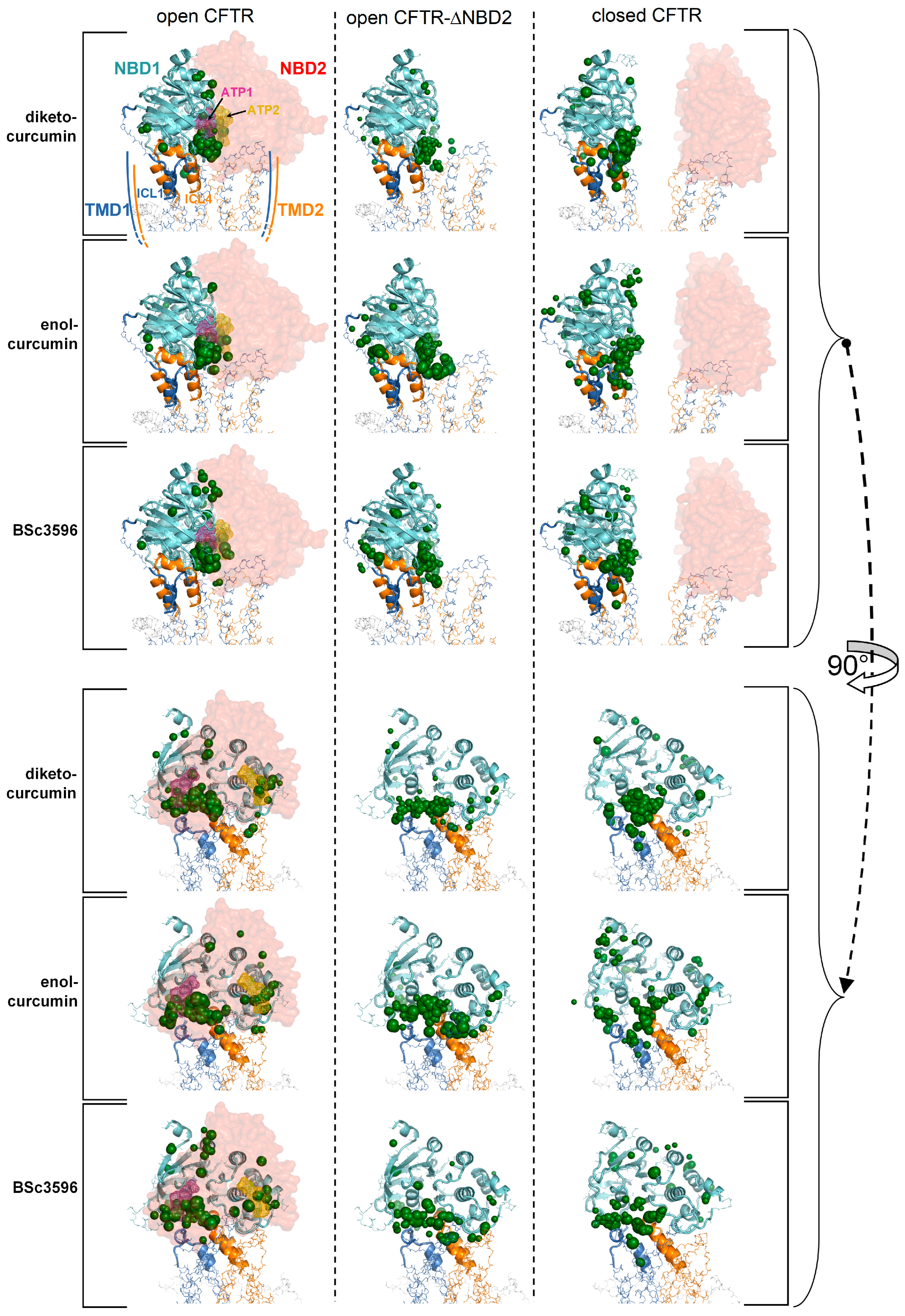

Figure 4.

Top scoring curcuminoid docking results on multi-conformer ensembles of open CFTR, open CFTR-ΔNBD2, and closed CFTR. Shown are the aggregated top scoring docking results of the individual ligands on each CFTR multi-conformer ensemble (for each of the twelve protein structure targets comprised in a CFTR ensemble, ten top scoring docking results, out of the ranked 5000 ligand binding poses, were kept; then, all groups of ten top scoring results from each of the twelve docking searches were aggregated). The top scoring docking results are represented by green spheres (drawn on the centers of docking poses with radii proportional to the normalized docking scores). For simplicity, only the parent PDB protein structures used to derive the CFTR protein ensembles are shown (PDB 6MSM for the open CFTR and open CFTR-ΔNBD2; PDB 5UAK for the closed CFTR; the solved fragment of the R domain is not shown); the two ATP binding sites are highlighted by magenta and dark-yellow meshes in the open CFTR structure).

Figure 4.

Top scoring curcuminoid docking results on multi-conformer ensembles of open CFTR, open CFTR-ΔNBD2, and closed CFTR. Shown are the aggregated top scoring docking results of the individual ligands on each CFTR multi-conformer ensemble (for each of the twelve protein structure targets comprised in a CFTR ensemble, ten top scoring docking results, out of the ranked 5000 ligand binding poses, were kept; then, all groups of ten top scoring results from each of the twelve docking searches were aggregated). The top scoring docking results are represented by green spheres (drawn on the centers of docking poses with radii proportional to the normalized docking scores). For simplicity, only the parent PDB protein structures used to derive the CFTR protein ensembles are shown (PDB 6MSM for the open CFTR and open CFTR-ΔNBD2; PDB 5UAK for the closed CFTR; the solved fragment of the R domain is not shown); the two ATP binding sites are highlighted by magenta and dark-yellow meshes in the open CFTR structure).

Figure 5.

Identification of a consensus binding pose on the closed and open CFTR ensembles. Shown are the aggregated top binding poses of curcuminoids after applying the criterion that same binding mode must be found on both the closed and open CFTR conformer ensembles (binding poses are shown as green sticks highlighted by the ovals): (a) diketo curcumin; (b) enol-curcumin; (c) BSc3596; (d) binding poses from a-b-c obeying the additional criterion of binding similarity between curcumin (any of the two tautomers) and BSc3596: only one binding pose fulfils both criteria (and both curcumin tautomers adopts that pose). The displayed protein structures are the open CFTR (PDB 6MSM) and the closed CFTR (PDB 5UAK). The ATP nearest to the consensus curcuminoid binding site is indicated by the magenta meshes in the two bottom figures.

Figure 5.

Identification of a consensus binding pose on the closed and open CFTR ensembles. Shown are the aggregated top binding poses of curcuminoids after applying the criterion that same binding mode must be found on both the closed and open CFTR conformer ensembles (binding poses are shown as green sticks highlighted by the ovals): (a) diketo curcumin; (b) enol-curcumin; (c) BSc3596; (d) binding poses from a-b-c obeying the additional criterion of binding similarity between curcumin (any of the two tautomers) and BSc3596: only one binding pose fulfils both criteria (and both curcumin tautomers adopts that pose). The displayed protein structures are the open CFTR (PDB 6MSM) and the closed CFTR (PDB 5UAK). The ATP nearest to the consensus curcuminoid binding site is indicated by the magenta meshes in the two bottom figures.

Figure 6.

Detailed view of the consensus binding pose. The consensus binding pose of a curcuminoid (sticks and green surface) is shown on the closed CFTR (PDB 5UAK) and open CFTR (PDB 6MSM). The protein is coloured by domain (TMD1, blue; TMD2, orange; NBD1, cyan; NBD2, red). The protein regions with invariant conformation in the closed and open CFTR (please see the text) are represented by ribbons, the other regions as backbone atom lines. The position of the ATP binding site nearest to the consensus binding pose is indicated by the magenta meshes. The NBD2 domain in the rotated views on the right is in front of the viewer and for clarity not shown.

Figure 6.

Detailed view of the consensus binding pose. The consensus binding pose of a curcuminoid (sticks and green surface) is shown on the closed CFTR (PDB 5UAK) and open CFTR (PDB 6MSM). The protein is coloured by domain (TMD1, blue; TMD2, orange; NBD1, cyan; NBD2, red). The protein regions with invariant conformation in the closed and open CFTR (please see the text) are represented by ribbons, the other regions as backbone atom lines. The position of the ATP binding site nearest to the consensus binding pose is indicated by the magenta meshes. The NBD2 domain in the rotated views on the right is in front of the viewer and for clarity not shown.

Figure 7.

MD simulations of curcuminoids complexed with the closed CFTR. Structures of curcuminoids in the consensus binding site of the closed CFTR used to kickstart the MD simulations and same complexes after 100 ns of simulation. The protein is coloured by domain (TMD1, blue; TMD2, orange; NBD1, cyan; NBD2, red). The protein residues near the ligands are shown as sticks (same colour as the parent domains); residues participating in non-bonding interactions (dotted lines) with the ligand are labelled in bold and underscored; other nearby residues requiring only minor movements to engage in interactions with the ligands (as judged by visual inspection) are labelled normally. The ligands are represented as balls and sticks (carbon atoms are in green, oxygens in red, and nitrogens in blue).

Figure 7.

MD simulations of curcuminoids complexed with the closed CFTR. Structures of curcuminoids in the consensus binding site of the closed CFTR used to kickstart the MD simulations and same complexes after 100 ns of simulation. The protein is coloured by domain (TMD1, blue; TMD2, orange; NBD1, cyan; NBD2, red). The protein residues near the ligands are shown as sticks (same colour as the parent domains); residues participating in non-bonding interactions (dotted lines) with the ligand are labelled in bold and underscored; other nearby residues requiring only minor movements to engage in interactions with the ligands (as judged by visual inspection) are labelled normally. The ligands are represented as balls and sticks (carbon atoms are in green, oxygens in red, and nitrogens in blue).

Figure 8.

MD simulations of curcuminoids complexed with the open CFTR. Structures of curcuminoids in the consensus binding site of the open CFTR used to kickstart the MD simulations and same complexes after 100 ns of simulation. For details on protein/residue colours and labels, please refer to the legend of

Figure 7.

Figure 8.

MD simulations of curcuminoids complexed with the open CFTR. Structures of curcuminoids in the consensus binding site of the open CFTR used to kickstart the MD simulations and same complexes after 100 ns of simulation. For details on protein/residue colours and labels, please refer to the legend of

Figure 7.

Figure 9.

Energies of interaction of curcuminoids with the individual CFTR regions composing the consensus binding site. Interaction energies of curcuminoids with CFTR calculated on MD simulation snapshots and subdivided for the protein regions ICL1, ICL4, and NBD1 (closed CFTR) and additionally, ICL2, ICL3, and NBD2 (open CFTR). The position of the ligand in the consensus binding site is indicated (L, green meshes). The individual protein regions employed to calculate the energies of interaction with curcuminoids are highlighted with ribbons in the respective molecular graph (the rest of the protein is shown with backbone lines). The protein is colored by domain (TMD1, blue; TMD2, orange; NBD1, cyan; NBD2, red).

Figure 9.

Energies of interaction of curcuminoids with the individual CFTR regions composing the consensus binding site. Interaction energies of curcuminoids with CFTR calculated on MD simulation snapshots and subdivided for the protein regions ICL1, ICL4, and NBD1 (closed CFTR) and additionally, ICL2, ICL3, and NBD2 (open CFTR). The position of the ligand in the consensus binding site is indicated (L, green meshes). The individual protein regions employed to calculate the energies of interaction with curcuminoids are highlighted with ribbons in the respective molecular graph (the rest of the protein is shown with backbone lines). The protein is colored by domain (TMD1, blue; TMD2, orange; NBD1, cyan; NBD2, red).