1. Introduction

It is widely held understanding that issues associated with climate change and waste related effects on the environment are linked to unsustainable behaviour [

1,

2,

3]. Therefore, sustained response to shift societal norms through effective behavioural change towards pro-environmental and sustainability values are important in driving sustainable development and promoting lasting pro-environmental behaviour (PEB) change. Whilst public engagement through monetary incentives, and fiscal approaches has been applied in managing environmental behavioural change, these can be assessed as transient drivers without long-term transformational benefits.

More recently, there has been a growing body of studies on using social psychological understandings to promote public attitudes and behaviours regarding pro-environmental values. In general, environmental psychosocial determinants ranging from conservation behaviour [

4,

5] and green identity [

6] have been used to promote environmental stewardship behavior. More specifically, interventions based on individual behavioural change has been noted to be ineffective in changing population-level behavior. We argued for consistency and systematic cross-situational perspective in motivating society-wide pro-environmental values across diverse social groups. Specifically, the apparent endorsement within society could strongly influence and guide people in taking pro-environmental action. When individuals acknowledge that their social group values and interests are both prioritized and reflected in pro-environmental action can translate into coherent and transformative pro-environmental actions [

7,

8,

9]. The underestimation of group social influence and dynamics of collective values can thus inhibit or impede pro-environmental action, but the effects it can have on environmental regulation and performance could be even more costly.

The objective in paying close attention to a broad range of social processes in promoting pro environmental values is certainly not to establish a new theoretical concept but to contextualise the power of cultural norms, group values and communal interests in shaping individual environmental behaviour [

10,

11,

12]. Sustainability transitions and environmental psychologists emphasize the benefits of examining the relationship between group behaviour and more succinctly collective environmental intentions [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. This complementary understanding arises from among many simultaneous social and cultural group influences underlying collective environmental behaviour [

18,

19]. By exploring the interaction and influence of collective group processes, this study establishes the social context in which environmental behaviour occurs. This paper introduces the concept of social identity and shapes how this is implicated in both the initiation and formation of individual environmental behaviour.

It is not always clear if pro-environmental and sustainability policies capture individual sensitivities to descriptive social norms, beliefs, values, and attitudes [

20]. Therefore, interventions aiming to change individual behaviour should consider social group to stimulate behaviour change. To fill this gap, this study proposes that groups and individuals in the same geographical space may respond differently to environmental and sustainability concerns, making pro-environmental policies unachievable and ineffective. Importantly, commonly held impression within the social group may reinforce individual-level behaviour offering an objective component of group experiences, a reflection of how people make sense of environmental issues. Therefore, social group roles and self-categorization may be used to predict the dimension of behaviour, and how individual identity correlates to these social systems of classification and description.

Developing and improving societal action towards sustainable future at a community level are critical when tackling sustainability challenges. Based on this understanding, our research examines the influence of collective action on individual environmental and sustainability behaviour [

21,

22,

23]. Studies have highlighted the efficacy of social identity in framing collective action towards implementing the SDGs [

24,

25,

26,

27]. Therefore, this study adds to the broader literature by exploring the centrality of social identity on individual intention towards environmental and sustainability values.

The social identity approach stems from the interplay of social processes and perception of oneness that are congruent of group identity. Scholars argued for the element of collective thought and collaborative governance, using various dynamic social processes and conceptual frames to model the systematic way individuals shape their behaviour towards the environment [

28,

29]. Therefore, social identity becomes a general frame of making sense of the social world with deep roots in perceptual, conceptual, historical, and social processes [

30]. We theorize that environmental transformation and sustainability transitions processes are complex social developments and multi-dimensional. And that deepening our knowledge of social dynamics and identities is useful in understanding sustainability transitions and pro-environmental behaviours. To do this, we use South Africa as the illustrative case for the investigation.

The study is structured as follows:

Section 2 explores literature review and the mediating role of group social processes on environmental and sustainability transitions behaviour.

Section 3 describes the methodological approach, data collection and analysis techniques employed in this study to draw findings.

Section 4 presents the study results, including interpretations, imperatives of social identity on collectivistic cultures traits that reinforces individual and group practices and attitudes, towards framing an environmental and sustainability identity.

Section 5 describes set of social identity-based outcomes for advancing positive environmental policy and behaviour.

Section 6 assess the study limitations and scope for improvements in future research. And

Section 7 concludes the study with a summary, contribution, and recommendations for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Embedded perspective of social identity in environmental transformation

Social identity and group categorisation forms the basis and understanding of environmental identity, a sense of connectedness with the physical environment [

31]. In other words, social identity is a learning and active sharing activity, a process by which individuals develop knowledge about traditional values, norms, and practices [

32,

33]. Societal transformations entail fundamental changes which may provoke complex interactions and contestation of values evident in a multi-cultural setting [

34]. In considering approaches to fostering pro-environmental and sustainability values, it is important to acknowledge that the relationship between individuals and group environmental values, and the behaviour they demonstrate is a complex one.

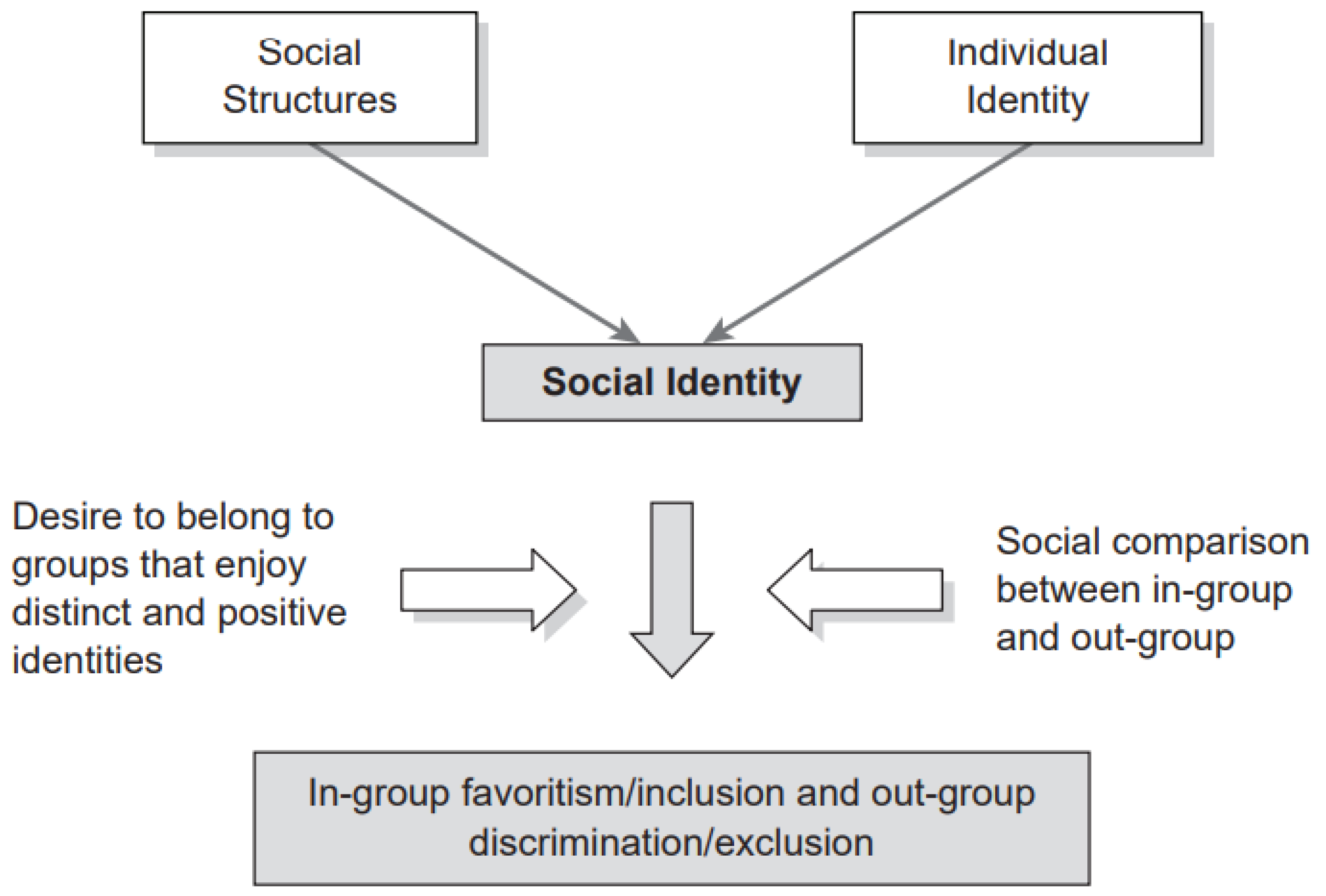

The concept of social identity is built from the seminal work of [

35] and refers to how individuals construct and situate their perspective and identity in society. Research showed that to act collectively group members develop a shared understanding of group values and interest, which in turn, motivate individual members to behave collectively [

36]. Therefore, promoting pro environmental behaviour without considering the wider societal social structure will not foster development changes [

37,

38]. The interconnectedness of social structure, beliefs, and cultural norms enables the individual to draw experiences and perception on how the social group view the world. A social structure is defined as a cluster of different social groups and/or institutions and how they interrelate and co-exist in a shared space [

39] (

Figure 1). From this point of view, human experiences, begins with interpersonal relations with group members, observing and attending to conditions that are relevant to the social group [

36,

38].

Group related activities and uncertain environmental factors compel individuals to collaborate more, causing them to forge a stronger communal bond and higher structural power [

40] (Fullan, 1998). Additionally, group members describe themselves in terms of a particular social context and display unique collective similarities as a group member different from other groups thereby manifesting biases and conflicting key values to intergroup relations [

41]. It is widely debated among scholars that insights from sociocultural and developmental studies can provide a groundwork for observing and monitoring social group biases, although prejudices can get embedded within the social system [

42]. However, it is important to map the manifestation of collective constructs and how they affect individual behaviour and actions towards the environment [

43]. Social norms intersect group values and obligations shaping an individual’s beliefs and how they should act [

44].

There are several other social structure, and group processes that addresses the theoretical background of intergroup relations such as Realistic Conflict Theory (RCT), which focuses on the assumption that intergroup conflict is derived from the individuals desire to maximize interest of their own group at the cost of other groups [

45]. Equity Theory (ET) on the other hand highlights that personal anxiety and intergroup conflict arise from injustice to the group in terms of distribution of resources [

46] Relative Deprivation Theory (RDT) describes dissatisfaction among social intergroups caused by measures of socioeconomic and political deficit that are comparative rather than absolute [

47]. The social identity theory is relevant to this study as it provides a coherent social framework that captures the perspective of normative elements and beliefs that shape the environmental worldviews of individuals across the social groups (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The awareness of group membership can be attributed to being characterised by the larger society on the ground of distinct cultural/ traditional legacy and complex historical connections [

48]. Therefore, emergent environmental identity is based on the contextual specificity of the social group, cultural and societal factors (

Figure 1).

2.2. Perspectives and Challenges in the Design of Deep system

It is widely held opinion that deep system changes and accelerating sustainability transitions are less effective across culturally diverse setting [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53], raising the question of how interventions can be used to guide the design of cultural adaptations environmental strategies [

50,

54]. Recent evidence suggests that socio-cultural adaptations and multi-level studies are valuable to accelerate the directionality of sociotechnical changes and environmental transformation [

38,

50]. It does so through the configurations of actors, specific niches and interconnected social and economic factors [

50]. The perspective of social identity examines collective action as a behaviour which affects societal response to societal changes [

51,

52,

53,

54].

Within the context of growing cultural diversity, dynamic contestation could emerge between the social groups imposing divergent directions and unrealistic challenges on sustainability transitions [

55]. The idea of embedding social identity processes to developmental studies underscore the importance of going beyond individual experiments, incorporating place-specificity, community niche factors and localized institutional framework to society wide transitions [

56,

57,

58]. This approach offers the opportunity of broadening and deepening the scale of societal transformations towards collective actions. Drawing from this, the Multi-Level Perspective - MLP and Social Practice Theory - SPT used in most sociotechnical studies provide further empirical support for analysing the complex social interactions of actors in a culturally diverse population [

50,

59]. The findings from this study informed the conceptualization of a functionalist model that maps the complex interpersonal social processes influencing behaviour. The social identity viewpoint examines the function of society and the role it plays in guarding choices and behaviour. The aim of this study is not to provoke a comprehensive analysis of the MLP and SPT instead relate social identity as a theoretical framework for conducting a deep structure analysis of social, cultural, historical, environmental, and psychological factors that influence the behaviours of individual in a targeted population.

2.3. South Africa Cultural Identity

Although social identity is a complex construct, it can, however, be employed in the design of cultural adaptation to pro environmental values, for diverse racial and ethnic populations who share distinct cultural characteristics and experiences. Culture is a unifying frame that allows individuals to conceptualize the perception of self, community, and the world. Group-focused distinctiveness and customs that apply to socio-cultural groups provide a framework that guides the values, briefs, and environmental worldview of the people [

60]. [

61] argued that identifying the construction of environmental worldviews is valuable because it provides an understanding into environmental behaviours, including learning for environmental social transformation.

While some studies explore factors influencing perception of environmental concerns, however, few researchers have explored the role that social identity plays in shaping environmental behaviour. The role social identity plays in influencing societal transformations and pro-environmental values in South Africa has not been adequately explored. Therefore, findings from a limited number of scholarships enhance the need for further empirical studies [

38]. For example, [

38] found divergent perception among the social groups in South Africa on developing unconventional energy systems based on economic and environmental factors. Similarly, [

62] found difference in group perception relative to risks and benefits of unconventional energy systems in South Africa. Previous studies have demonstrated the need to explore the degree of in-group and out group perception about sustainability transitions [

63,

64,

65] supporting the theory that low uncertainties about the cost and risks of the energy transition has an impact on sustainability outcomes [

66].

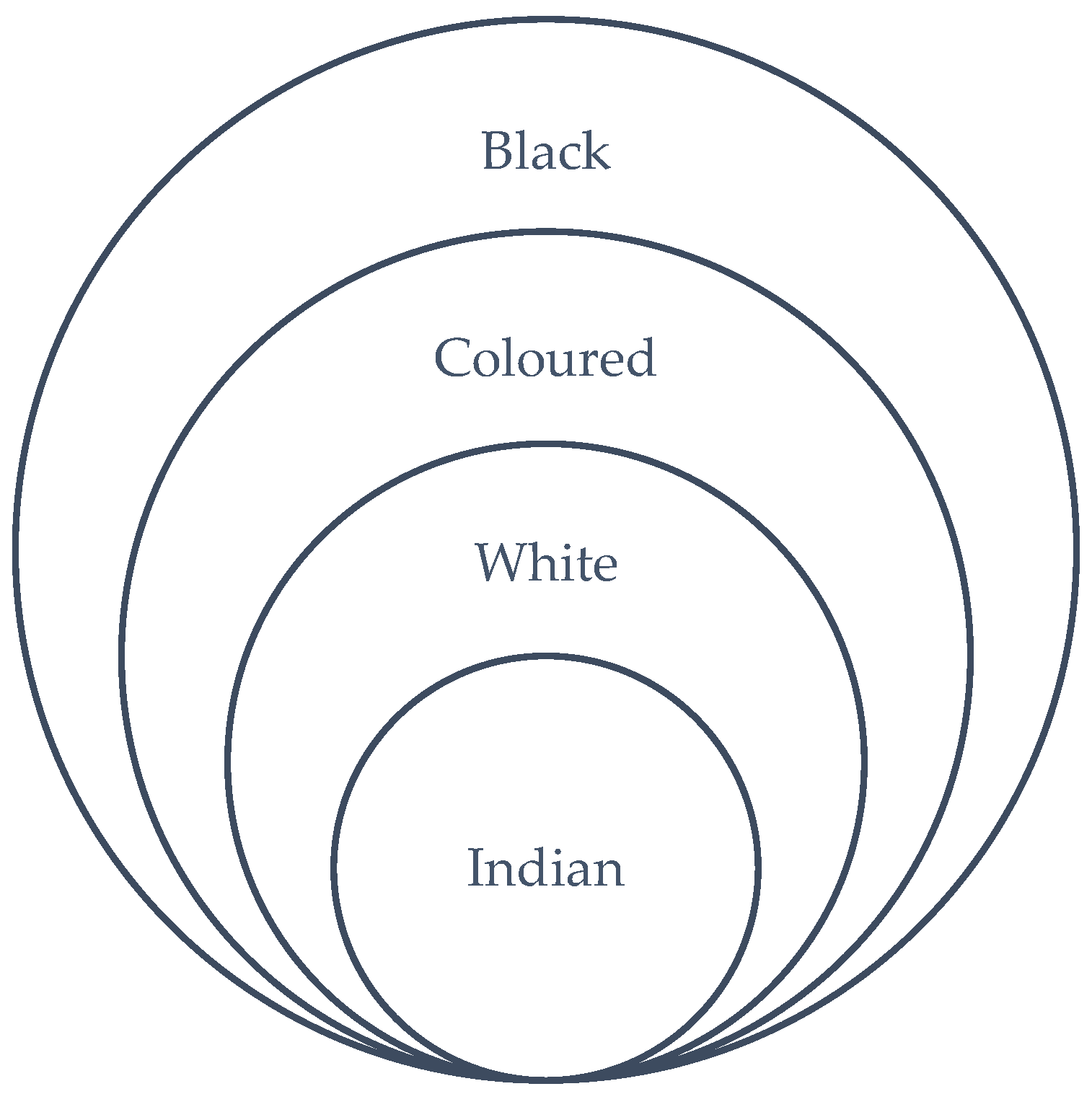

Social categorization across the South Africa population describes the distribution of the dominant ethnic groups (tribes) as “having distinct culture,” denoting that the people share commonality of beliefs, values, norms, prospects, including customs and traditions, as well as sharing recognized social networks and ideals of behaviour that describe them as a cultural group [

67] (

Figure 2). Within the framework of ethnicity as a social construct, social identity is used to understand the variations in environmental values across the population. In and out-group identification and the dynamics that create these differences (biases, generalisation, emotions, prejudices, and stereotypes) can trigger conflicts in the landscape. The differences between the social groups can become more evident and predominate leading to disruptive activities rather than transformational innovation [68,69.70]. At the same time, cultural heritage is important in defining the social identity of the individual which may overlap several other subgroup configurations/ affiliations of the individual in terms of class, occupation, corporate culture, gender, education, and personal ability. These social configurations can provoke contradictions of ideas and values resulting to social crisis [

71,

72] For example, studies by [

73] highlights incidences of social/ racial conflicts between the various dominate social groups in South Africa (

Figure 2). Furthermore, the consequence of power imbalances among the social groups in South Africa illustrates the need to apply the theory of social identity in advancing social environmental transformation [

74] (

Figure 2). For instance, the White social group has the most management and economic power while the Black have the political power [

73].

Furthermore, the effect of multiculturalism produces unequal power relations among the social groups. Accordingly, the dominant groups may have considerable influence in society, promoting only values that serve their interest (

Figure 2). The effects and dynamics of these imbalances (economic and political) and the racial/ social divide in the South Africa landscape pose a barrier to transformation [

75,

76,

38]. Furthermore, the effects of power dominance of an individual in the social group may be repressed in another sub system or social group. Sustainability transformation or changes in the environment may be considered too fast or too slow depending on the cultural perspectives upon which it is assessed [

77]. [

73] noted cases of privileges by the dominant social groups and threat by the minority population to transformational changes in South Africa. The Black and Coloured population constitute dominant social groups in South Africa while the minor social groups are the White and Indian groups. For example, the South African Africa National Congress affirmative action measures are targeted to empower Blacks and Coloured groups rather than Indians and the White social groups [

78,

79,

38].

Studies have demonstrated that social identity groups prefer clear, distinct, and protected spaces or boundaries and identify their in-group configuration as homogenous and are locked-in values, norms, and culture [

80,

81] which becomes challenging for transformation to take place. [

82] suggests that individual worldviews, behaviours, and environmental consciousness “are held in different ways across the social groups of the population”. Therefore, conditions that increase differences between the social groups is likely to develop divergent environmental behaviour.

From this perspective, social identities can adapt or change through continuous interaction with the environment. From a social-ecological systems perspective, developing an inclusive, sustainable, and resilient society is central in building environmental self-efficacy [

76]. The objective of fostering sustainability is developing policies that appeal to social group values. Therefore, studies highlight collective action for developing pro-environmental and sustainability behaviour [

83]. These differences will become progressively significant in today’s world as multilateralization requires cultures and social networks to cooperate in advancing societal transformation, bringing the importance of social identity to the fore. Therefore, studies on social identities are expected to provide useful insights to cultural responses to environment issues, environmental identity formation and culturally prescriptive intervention framework.

2.4. Environmentally specific group-categorization

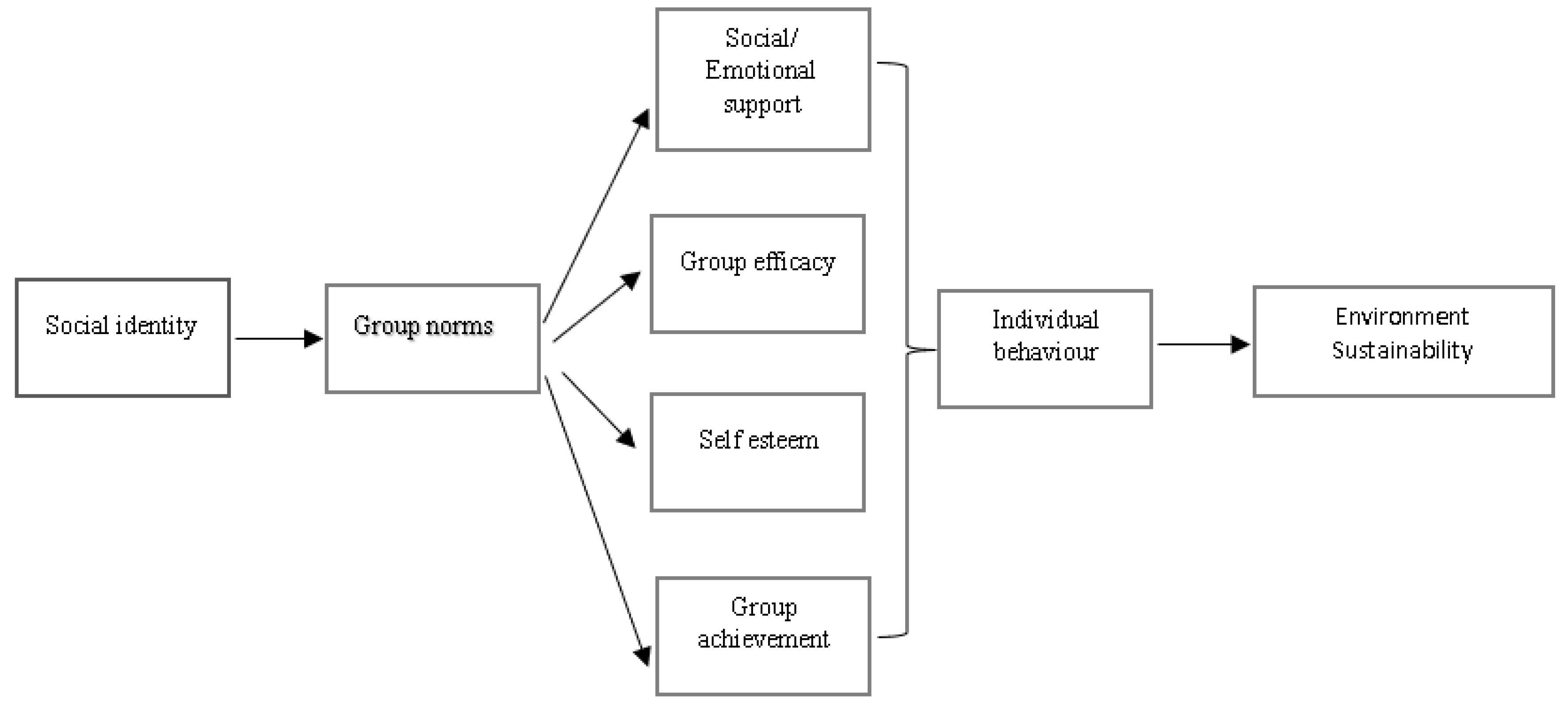

Drawing on the theory of social identity, this study posits that an individual’s membership of a social group strengthens the individual’s solidarity, cohesion, and attitude towards environmental sustainability (

Figure 3). In consequence, the willingness to consider group values and interest (strong environmental identity and strong economic incentives) in support or opposition to sustainability transitions remain the reflexive position of this study. Based on the analysis of literature, this study hypothesizes that the configuration of the social structure and social group processes are keys to understanding the question of whether and how spatial changes could be initiated and what role social actors might (or might not) play in contributing to shaping the directionality of societal transformation. Accordingly, this paper advances the theory of social identity as the crucial factor that influences sustainability outcomes. More specifically, the study examines the question of whether environmental pressure induces the behaviour of individuals in the social group, including the direction of transformational change, and if so, which trajectories would they choose to improve environmental wellbeing (

Figure 3).

Sustainability transitions are complex and chaotic processes that are anchored on significant adaptation and have different implications for different group of people in society. It is further necessary to note that these changes may create sectorial barriers among incumbent actors or trigger a range of sociocultural conflicts and uncertainties in the transition pathway [

84]. These interpretive implications and sociocultural dimensions have been found to weaken both pro-environmental values initiatives and sustainability transitions policies [

85,

86]. This does not imply that governance of sustainability transitions and pro-environmental policies will be consensual, as different social groups and niche actors may have different sociocultural interest and meanings, however, it does imply that pro-environmental and sustainability concerns should be framed on a broader societal examination of social values, norms, interest, and practices. More broadly, some key reasons for infusing social identity framework in environmental and sustainability studies is to situate policy measures more meaningfully by introducing local context, sense making and community ownership in innovative environmental systems.

2.5. Effects of Social identity on individual behaviour

Social identity is a learning and sharing activity, a process by which individuals develop knowledge about traditional values, norms, and practices [

32] (Heredia et al., 2013). Research emphasis on how social identity can be defined theoretically and analysed empirically on environmental related issues [

87,

88].

Evidence suggests that when social norms are aligned to pro-environmental goals, they can strengthen long term sustainability objectives [

89,

90]. For instance, positive environmental group association predicts pro-environmental actions and sustainable behaviour [

91]. The findings of this study suggest that more strongly identified group members are more likely to engage in ingroup normative environmental and sustainability behaviours [

92]. Policymakers need to map ingroup values and norms and create incentives that support collective action and shared commitment towards pro-environmental behaviours. This tends to incorporate ingroup members into the same synergy of environmental action and solidarity, so that collective response become a driving mechanism to accomplish pro-environmental goals. This approach has been applied in numerous studies to improve environmental and sustainability objectives [

93,

94,

95].

While it constructive to examine personal level environmental behaviour; by contrast group level behaviour affects both the individual and broader societal systems, moving beyond the individual into the public sphere (including multiple facets of social cultural meaning). Considering that social groups are disproportionately impacted by environmental harm and have different environmental norms and values [

96,

97]

Figure 3. We suggest the need to examine how social identity correlates with environmental behaviour. As argued above, when social identity becomes salient, individual level of awareness, alignment in briefs and social attachment to the social group increases and differences in interpersonal social interaction between ingroup and outgroup social members are accentuated. Seminal work by [

98] suggests that the individual perception and belief on environmental issues is shaped by the complex interaction of sociodemographic variables such as cultural orientation, social norms, economic situation, and expectations within the social context. Therefore, assimilating the components of group value-belief-norm variables in sustainability transitions studies could be used to predict the individual environmental and sustainability behaviour. We define ingroup social norms as the expected actions or behaviour of people in representing or safeguarding the values and interest of their family, community, or ethnic group [

99]. Studies by [

100] confirmed that social group orientation, intention and interest motivates individual people to behave in a predefined way towards environmental issues.

3. Materials and Methods

The qualitative method using in-depth interviews was well suited to address the research questions including perceptions, preferences, practices, and beliefs of the participants regarding environmental and sustainability issues without imposing constraints associated with quantitative study which often rely on predefined statements [

101]. This study uses social identity as lens to ask questions and engage in depth analysis. The interview was guided by key questions (semi-structured). However, the development of the discussion was driven by the participants. The purpose of the interview was threefold: (a) chart the knowledge and attitude of the participants towards sustainability transitions; (b) explore how these perceptions are articulated among the social groups and (c) investigate how perception are accepted/ supported or contested/ opposed by the other out groups members with a view to map shared barriers and commonality to sustainability transitions.

In total, (N = 60) in-depth interviews were conducted for this study. Participants were recruited by purposive sampling technique to represent the demographic profile of South Africa in terms of ethnic/ social grouping. The participants were grouped according to their social group: Black, White, Indian, and Coloured (

Table 1;

Figure 2). The qualitative method allows a common framework to be used for all the participants across the social groups therefore providing a better understanding and knowledge of environmental decision-making and behaviour within the social identity context. The characteristics of the respondents are presented in

Table 1.

3.1. Thematic Analysis

The objective of this study was to explore the sociological factors underlying the observed variation across the social groups. The interview approach guided the interpretation and understanding of how social identity intersects with environmental issues. The interviews presented the opportunity to deduce how culture and salient subjective experiences are used to construct collective belief on environmental issues.

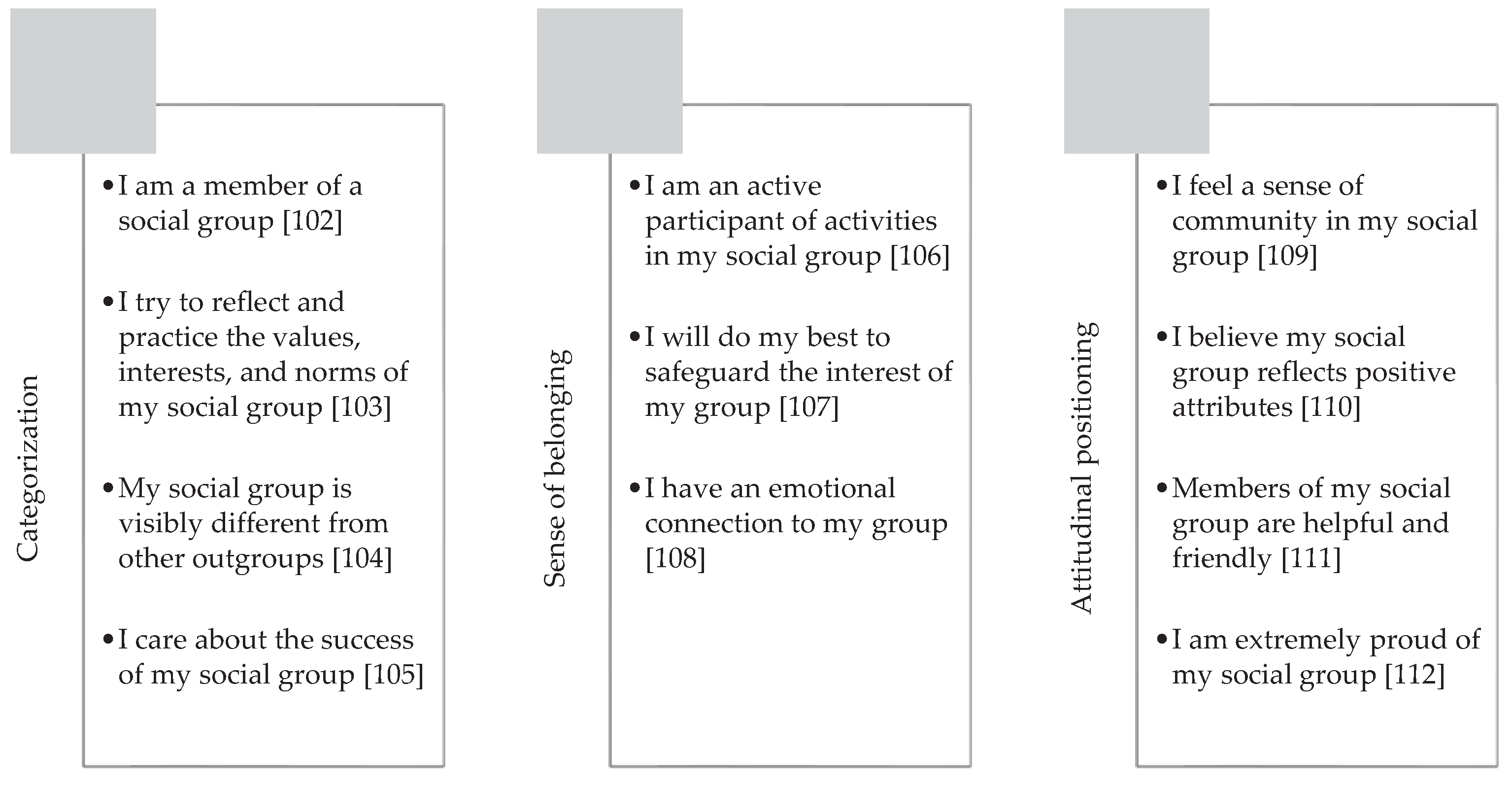

The primary analysis focused on the keen sense of social identification, behavioural intentions, sense making, perceptions, and the extent to which environmental beliefs and social factors predict support or opposition towards pro-sustainability activities. We examined respondents’ support, and relationship between the social groups for sustainability-friendly beliefs as an outcome (

Figure 4). To test the moderating effects of the social identity hypothesis and how people interpret and find meaning to environmental issues, this study created a conceptual social identification framework to understand the potent determinant of individual behaviour and awareness to sustainability transitions based on social categorization, sense of belonging and attitudinal positioning (

Figure 4).

The in-depth interviews were transcribed with notes summarising the similarities, differences, links, and conflicts of the resultant texts. Explanatory accounts and themes (patterns) were developed inductively from the codes and categories responses using NVivo v1.7.1 in deducing the respondent responses in the context of the flow of the conversation and to interpret the data in detail. Thematic analysis provides a systematic strategy needed to improve the analysis of divergent sets of data and enhance the quality of interpretation [

102],

Table 2.

3.2. Measures and Themes

Social identification: Participants were asked to identify the social group they belong to (‘’I identify with a Black, White, Indian, and Coloured social group’’) with follow up questions.

Ingroup environmental norms: Participants were asked to choose options that suggest the position of their social group towards the environment and sustainability transitions. ‘’ I reflect the values and norms of my social group towards the environment’’, ‘’I value pro-environmental values’’.

Pro-environmental and sustainability offering: Participants were asked if they would participate in local pro-environmental rallies or charities and spend time supporting environmental and sustainability awareness initiatives.

Pro-environmental/ conservation behaviours: Participants were asked to peruse over a list of seven pro environmental actions they could do to improve the environment, such as “use of energy saver bulbs’’ “aggregate recycles items to a recycle bin’’ and how much they engage in these options.

3.2.1. Thematic quotes on environmental behaviour

‘’The climate change issue and global environmental problems are caused by the developed world. We have not contributed to the global environmental issues. The polluters should be responsible for the issues, not us’’. (Black Participant, 3)

‘’The notion of developed countries dictating to poorer countries on how they should live their lives is unjust, immoral, and hypocritical. The rich countries own the multinational companies polluting the environment in Africa, they destroy our environment, leaving us with nothing but a responsibility to clean up the pollution. This can’t be right. We have been caring for our environment for generations’’. (Coloured Participant, 15)

‘’We have been asked to abandon our natural energy resources and transition to alternative energy sources in order to accommodate the lavish lifestyle of the western people. This is not fair and equitable’’. (Black Participant, 22)

‘’Pro-environmental behaviour entails taking actions to minimize the impact on the environment by individuals and communities through sustainable consumption. There is need to address impact on the environment caused by the extractive industries, industrialization, and urbanization’’. (White Participant, 7)

‘’It is important to note that our indigenous activities encourage pro-environmental behaviour and hold unique traditional knowledge and belief system for the sustainable management of the environment, biodiversity, and natural resources’’. (Black Participant, 42)

‘’Global warming worsens the inequalities and deprived socio-economic conditions already experienced by indigenous peoples and the practices that permeated colonization and exploitation of our natural resources’’. (Coloured Participant, 12)

‘’Global environmental improvement is a collective responsibility requiring individuals and organisations to take action to preserve the environment’’. (Indian Participant, 17)

‘’Our global well-being is threatened by the growing tide of wastes generated by society. We must transition into a carbon-neutral future by stopping the extraction of fossil fuel and adopting sustainable lifestyle’’. (White Participant, 45)

‘’Industrialized countries are harming the environment in significant ways by their emissions. The focus should be on high polluting countries to reduce their emissions’’. (Indian Participant, 31)

‘’The possibility that the global environment may be destroyed if society doesn’t take urgent action is predictable. Society can do a lot by promoting positive environmental values through awareness and education’’. (White Participant, 27)

3.2.2. Thematic quotes on sustainability transitions

‘’ ...renewable energies require large land space and causes disruptions to farms and animals. We certainly need more land space to grow our food and sustain our livelihoods.

(Black Participant, 22)

It is unfair to ask us to abandon our natural energy resources and adopt a new and costly energy systems for a problem that has nothing to do with us. Climate change is caused by western countries, they should be responsible for mitigating the effects not poor African countries. (Coloured Participant, 15)

The solution to tackling the climate change crisis is to end our reliance on fossil fuels. We need to do this urgently. (White Participant, 20)

We are blessed with abundant natural energy resources such as sun, wind and geothermal so transitioning should not be a problem. (Indian Participant, 11)

4. Results and Discussion

This study found ambivalence in environmental beliefs across the four social groups (Black, White, Indian, and Coloured). The study found that manifestations collectivistic cultural traits shape individual behaviour on environmental issues. Two contextual themes are evidenced in the study in moderating socio-environmental behaviour: ‘’environmentalism’’ and ‘’extractivism’’. This concept appears to both frame and reinforces individual and group practices, attitudes, and power dynamics. The empirical practices of extractivist activities (historical and contemporary), including destructive capitalism in natural resource exploitation, distributional injustices and widening socioeconomic inequalities are measurable constructs that helps us to conceptualise the framing of environmental discourses within the Black and Coloured social groups. These findings emanate on the backdrop of empirical evidence that Africa’s emits less than 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions compared to the rest of the developed world [

113]. Furthermore, studies have shown huge economic and social imbalances in South Africa with cascading inequality in the Black and Coloured social groups compared to the White and Indian groups (who appear to have a strong economic base in the country [

114].

The consequence of climate change and environmental degradation is intensifying in South Africa and reflects the role played by human impact on the environment. The effects exacerbate the challenges already confronted by indigenous peoples including socio-political and economic marginalization, deforestation, forest fragmentation and depletion of natural resources. The findings of this study further highlight the intersectionality of social identity and other historical factors that increase the vulnerabilities to environmental harm. And an interesting element highlighted by the Black and Coloured social groups, as evoked by the lived environmental vulnerabilities/ realities initiated by the colonization of the atmosphere by predominately White and Asian countries in the Global North.

This causality link is evident given that higher proportions of Black and Coloured residents are disproportionately sited in economically deprived areas compared to the White and Indian social groups and consequently, impacted by environmental and economic exposures. More generally, the behaviour of the Black and Coloured social groups towards the environment is framed from a psychological perspective arising from the concept of climate/ environmental justice, colonisation and socio-economic deprivation making environmental protection a secondary issue [

115,

116]. The result of this study provides a theoretical framework for understanding the relationship between the Black and Coloured environmental behaviour and country wide inequalities. We found that environmental behaviour is deeply intertwined with patterns of inequality on many levels such as economically powered and less privileged individuals in society, wealthy industrialised countries, and poorer nations aligning with previous findings that the most vulnerable in society are disproportionately impacted by environmental pressures. We inferred that the environmental hierarchy of needs theory and sociological demographics suggest that people with lesser economic power are more likely to emphasize economic resources for survival rather than focus on environmental issues [

117,

118,

119,

120,

121,

122]. This study is consistent with [

123] hierarchy of needs theory which demonstrated that the needy or marginalized people in society are more preoccupied with economic problems rather than environmental challenges. The demographic profile shows that the White and Indian social groups are wealthier than the Black and Coloured groups (

Table 1). White and Indian groups are more likely to adopt a pro-environmental behaviour and more active in environmental activism while Black and Coloured pro-environmental behaviour and environmental activism stems from the need for climate justice. A key lesson is understanding that contextual economic perspective is entangled with environmental behaviour.

The differential socioeconomic dimensions, and degrees of exposure to climate variabilities of the social groups influence their environmental and sustainability transitions behaviour. In this sense, the Black and Coloured view mainstream environmental issues as a Western environmentalism philosophy, grounded in environmental racism [

124,

125,

126,

127]. The results of this study conceptualised environmental and ecological failures through a causal attribution of Westernized, Asianized, and industrialized activities assigning specific actions of pollution and extractivism to the White and Indian social groups. As an example, extractivism and mining activities has continued to reshape the South Africa landscape at an unprecedented destructive pace and scale contributing to social displacement, deterioration of biodiversity and severe environmental damage. Against this backdrop, the damage caused by entrenched extractivism plays a key role in weakening pro-environmental values. This study proposes a deep transformational model in which environmental equity and climate justice are precursors of pro-environmental behaviour and action toward environmental conservation in a multicultural setting. These differences in sociocultural values inform the basis for collective environmental behaviour, resulting in misalignment of social group values/ interests and embedded social processes in determining divergent environmental action. Therefore, establishing a collective environmental identity is critical in fostering environmental transition.

In conclusion, we found evidence to suggest that in-group factors have a significant impact on environmental identity and this condition of internal group cohesion means that individuals within the social group are likely to adopt the group environmental values. Therefore, the impact of in-group cohesion on environmental issues could either foster or hinder environmental interventions.

5. Policy implications and future research

As discussed above, social group values have the potential to undermine positive environmental objectives. Furthermore, conflicts in intergroup relationships can reinforce barriers to sustainability transitions such that group members exhibit anti-environmental behaviour. When examined in this context, it is easy to forge inclusive policy strategies that encompass all the social groups. It is often the case that individuals are more likely to act in a pro-environmental and sustainable manner when the norms of the social group are aligned with social/ environmental justice and positive environmental values. The appropriate approach is to design environmental and sustainable policy interventions that place emphasis on collective ingroup environmental norms and intersectional justice. It is also imperative for policymakers and researchers to shift focus on frames and assign sustainable resources that appeal and align to the values and norms of the social group to stimulate positive responses towards environmental citizenship [

128,

129]. This study highlights a unifying conceptual framework for understanding the relationship and influence of disproportionate socioeconomic power, “within-country social inequalities, western environmental worldview, environmental justice on environmental behaviour.

Throughout this study, we highlighted pertinent questions that environmental and sustainability transition scholars could address to foster a more positive environmental behaviour. This study proffered a social identity approach in framing inclusive environmental policies and interventions that align to the various group values and norms. Thus far, psychological, and sociotechnical studies in promoting pro-sustainability and environmental behaviour have focused on individual actions, however, there is need to place emphasis on the broader social processes and ingroup norms that shape individual and collective group behaviour. Forging an inclusive policy response through a multi-level perspective would promote social, environmental, and institutional effects that are critical in shaping the broader pro-environment interactions. The findings suggest that environmental thought processes among social groups are regulated by contrasting ideologies and hold great promise in extending future studies on environmental identities. These solutions propose that policies need to be formulated on a structural level: a deep transformational framework that addresses the socio-economic vulnerabilities of Black-Coloured group in order for their environmental rights to be better safe-guarded from the impacts of environmental harm. And in response to their demands for climate and environmental justice.

6. Limitation of the Study

While this study sought to address the gaps in previous studies which mainly focused on prescriptive assessment of environmental behaviour. Participants interviewed for this study linked local context, embedded intersectionality, worldviews, socioeconomic considerations to environment problems rather than on what descriptive norms or environmental behaviour the social group is engaged in. Likewise, it will be valuable for future studies to increase the sample size and complement the qualitative insights with quantitative data and analysis to help capture the sensitivity to nuanced variations across the social groups and spaces.

7. Conclusion

Previous studies explored the social antecedents of environmental and sustainability behaviour at the individual level. Therefore, it becomes critical to study the environmental norms, values, behaviours, and beliefs of individuals from a cross-cultural perspective so that tailored actions and interventions can be adopted in country context toward environmental conservation and sustainable practices. This study adopts the theory of social identity to address intergroup relationships and social group identity processes. This study is also embodied with other theoretical frameworks of self-categorization and collective representations to identify critical contextual factors that shapes key construct in environmental and sustainability studies. These social processes trigger specific outcomes in improving pro environmental behaviours. With emphasis on multiculturalism and emergence of ethnic identities, we argue that it is important to examine environmental/ sustainability transition views of the population. Although transition scholars advocate the importance in understanding the governance of sustainability transitions in multicultural environment, the underlying social processes have barely elaborated or conceptualised in Sub-Saharan Africa. This study uses social identity to explore how the distinct ethnic groups in South Africa construct their story and narrative about sustainability transition. The study identified a lock-in behaviour and divergent social and environmental perspectives, and motivations between the social groups in their collective formation on sustainability transition. Exploring how group dynamics affect individual perception and behaviour towards sustainability transitions will provide an understanding of the consequences that sustainability transitions have on the wider society. In doing so, this paper also provides an empirical insight about the challenges of the energy transition in a multi scalar context. The disposition of the individual to the social processes of the group may take a positive and negative position shaping the directionality of sustainability transition. This study highlights how social identity can be used to motivate sustainable behaviour in a diverse culture or what their relevance or feature could be in fostering sustainability transitions in a homogenous population. Given the complexity of sustainability transitions, this study bridged the gap in understanding the effects of social identity on sustainability transition thinking. We hope to motivate transition scholars to contribute to this field of studies by recognising the empirical outcomes on which this study build.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Julius Irene; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Julius Irene; writing—review and editing, Julius Irene, Chux Daniels, Mary Kelly, Bridget Irene, Regina Frank and Kingsley Okpara; methodology, Julius Irene and Bridget Irene; data analysis, Julius Irene and Chux Daniels and Bridget Irene; references, Regina Frank and Kingsley Okpara. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Marshall, R.E.; Farahbakhsh, K. Systems approaches to integrated solid waste management in developing countries. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 988–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.L. and Singh, P.K., 2017. Global environmental problems. Principles and applications of environmental biotechnology for a sustainable future, pp. 13-41.

- Barakat, M.M. and Aboulnaga, M.M., 2023, September. Urban Resilience and Climate Change: Risks and Impacts Linked to Human Behaviours in the Age of COVID-19. In Mediterranean Architecture and the Green-Digital Transition: Selected Papers from the World Renewable Energy Congress Med Green Forum 2022 (pp. 691-710). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Pocock, M.J.; Hamlin, I.; Christelow, J.; Passmore, H.A.; Richardson, M. The benefits of citizen science and nature-noticing activities for well-being, nature connectedness and pro-nature conservation behaviours. People and Nature 2023, 5, 591–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammann, J.; Arbenz, A.; Mack, G.; Nemecek, T.; El Benni, N. A review on policy instruments for sustainable food consumption. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 36, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.H.; Zhongfu, T.; Irfan, M.; Ahmad, B.; Ali, M. Assessing eco-label knowledge and sustainable consumption behavior in energy sector of Pakistan: an environmental sustainability paradigm. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 41319–41332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.-C.; Stritch, J.M.; Christensen, R.K. Eco-Helping and Eco-Civic Engagement in the Public Workplace. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2016, 40, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouro, C.; Duarte, A.P. Organisational Climate and Pro-environmental Behaviours at Work: The Mediating Role of Personal Norms. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Yu, X. Green transformational leadership and employee organizational citizenship behavior for the environment in the manufacturing industry: A social information processing perspective. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1097655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.Y.; Bowker, J.M.; Cordell, H.K. Ethnic variation in environmental belief and behavior: An examination of the new ecological paradigm in a social psychological context. Environment and behavior 2004, 36, 157–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, L.; Klocker, N.; Aguirre-Bielschowsky, I. Environmental values, knowledge and behaviour: Contributions of an emergent literature on the role of ethnicity and migration. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2018, 43, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, V.; DeRonda, A.; Ross, N.; Curtin, D.; Jia, F. Revisiting Environmental Belief and Behavior Among Ethnic Groups in the U.S. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, F.S.; Knapp, C.N. Sense of place: A process for identifying and negotiating potentially contested visions of sustainability. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 53, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterson, V.A.; Stedman, R.C.; Enqvist, J.; Tengö, M.; Giusti, M.; Wahl, D.; Svedin, U. The contribution of sense of place to social-ecological systems research: a review and research agenda. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axon, S. , 2018. The human geographies of coastal sustainability transitions. In Towards coastal resilience and sustainability (pp. 276-291). Routledge.

- Welch, D.; Yates, L. The practices of collective action: Practice theory, sustainability transitions and social change. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2018, 48, 288–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.; Bögel, P.; Upham, P. The role of social identity in institutional work for sociotechnical transitions: The case of transport infrastructure in Berlin. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 162, 120385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postmes, T.; Spears, R.; Lee, A.T.; Novak, R.J. Individuality and Social Influence in Groups: Inductive and Deductive Routes to Group Identity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 89, 747–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jans, L. Changing environmental behaviour from the bottom up: The formation of pro-environmental social identities. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 73, 101531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomberg, E.; McEwen, N. Mobilizing community energy. Energy Policy 2012, 51, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; Hornsey, M.J. A Social Identity Analysis of Climate Change and Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors: Insights and Opportunities. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, I.; Barth, M.; Jugert, P.; Masson, T.; Reese, G. A Social Identity Model of Pro-Environmental Action (SIMPEA). Psychol. Rev. 2018, 125, 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggar, P.; Whitmarsh, L.; Nash, N. A Drop in the Ocean? Fostering Water-Saving Behavior and Spillover Through Information Provision and Feedback. Environ. Behav. 2023, 55, 520–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.M.; Crosby, B.C.; Stone, M.M. The Design and Implementation of Cross-Sector Collaborations: Propositions from the Literature. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapucu, N. and Hu, Q., 2020. Network governance: Concepts, theories, and applications.

- Wong, R. What makes a good coordinator for implementing the Sustainable Development Goals? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.W.; Smith, E.R. Conceptualizing Social Identity: A New Framework and Evidence for the Impact of Different Dimensions. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 25, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkuyten, M. Further Conceptualizing Ethnic and Racial Identity Research: The Social Identity Approach and Its Dynamic Model. Child Dev. 2016, 87, 1796–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, M.; Baron, A. The development of social categorization. Annual review of developmental psychology 2019, 1, 359–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, S. , 2003. Environmental identity: A conceptual and an operational definition. Identity and the natural environment: The psychological significance of nature, pp.45-65.

- Heredia, A. , Cuadrado-Mingo, J.A., Amescua, A. and Garcia-Guzman, J., 2013. Exploring the use of social identities for sharing knowledge in the learning process. In EDULEARN13 Proceedings (pp. 5849-5856). IATED.

- Allen, B.J. , 2023. Difference matters: Communicating social identity. Waveland Press.

- Swilling, M. , 2020. The age of sustainability: Just transitions in a complex world (p. 350). Taylor & Francis.

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. Intergroup behavior. Introducing social psychology 1978, 401, 466. [Google Scholar]

- Akfırat, S.; Uysal, M.S.; Bayrak, F.; Ergiyen, T.; Üzümçeker, E.; Yurtbakan, T.; Özkan, S. Social identification and collective action participation in the internet age: A meta-analysis. Cyberpsychology: J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, C.M.; Schmitt, M.T. Do people who feel connected to nature do more to protect it? A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irene, J.O. , 2021. The socio-economic and environmental implications of shale gas development in the Karoo, South Africa (Doctoral dissertation, Kingston University).

- DiMaggio, P. , 2019. Social structure, institutions, and cultural goods: The case of the United States. In Social theory for a changing society (pp. 133-166). Routledge.

- Fullan, M. Leadership for the 21st century: Breaking the bonds of dependency. Educational leadership 1998, 55, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Abrams, D.; Hogg, M.A. Social identity and self-categorization. The SAGE handbook of prejudice, stereotyping and discrimination 2010, 1, 179–193. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio, J.F. , Gaertner, S.L. and Pearson, A.R., 2005. On the Nature of Prejudice: The Psychological Foundations of Hate.

- Bogaert, S.; Boone, C.; Declerck, C. Social value orientation and cooperation in social dilemmas: A review and conceptual model. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 47, 453–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E. Beyond Homo Economicus: New Developments in Theories of Social Norms. Philos. Public Aff. 2000, 29, 170–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutezo, M.E. , 2015. Exploring the value of realistic conflict theory and social identity theory for understanding in-group giving in the minimal group paradigm (Doctoral dissertation).

- McKown, C. Social Equity Theory and Racial-Ethnic Achievement Gaps. Child Dev. 2012, 84, 1120–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, Q.T. Reinvigorating relative deprivation: A new measure for a classic concept. Soc. Sci. Res. 2006, 35, 779–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, M.M. , 2008. Social psychological perspectives of workforce diversity and inclusion in national and global contexts. Handbook of human service management, pp.239-254.

- Wieczorek, A.J. Sustainability transitions in developing countries: Major insights and their implications for research and policy. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 84, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schot, J.; Kanger, L. Deep transitions: Emergence, acceleration, stabilization and directionality. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1045–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feola, G. Capitalism in sustainability transitions research: Time for a critical turn? Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 2019, 35, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häyrynen, S.; Hämeenaho, P. Green clashes: cultural dynamics of scales in sustainability transitions in European peripheries. Palgrave Commun. 2020, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swilling, M. , 2020. The age of sustainability: Just transitions in a complex world (p. 350). Taylor & Francis.

- Castro, F.G.; Barrera, M., Jr.; Holleran Steiker, L.K. Issues and challenges in the design of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions. Annual review of clinical psychology 2010, 6, 213–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irene, J.O.; Kelly, M.; Irene, B.N.O.; Chukwuma-Nwuba, K.; Opute, P. Exploring the role of regime actors in shaping the directionality of sustainability transitions in South Africa. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, L.; Raven, R.; Verbong, G. Local niche experimentation in energy transitions: A theoretical and empirical exploration of proximity advantages and disadvantages. Technol. Soc. 2010, 32, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, L.; Truffer, B. Places and Spaces of Sustainability Transitions: Geographical Contributions to an Emerging Research and Policy Field. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2012, 20, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.; Coenen, L. The geography of sustainability transitions: Review, synthesis and reflections on an emergent research field. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 2015, 17, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: A multi-level perspective and a case-study. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, R.F.; Mendelson, T. Toward evidence-based interventions for diverse populations: The San Francisco General Hospital prevention and treatment manuals. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 73, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.J. , 2006. The Impact of Culture and Race on Environmental Worldviews: A Study from the Southeastern US. Adult Education Research Conference. https://newprairiepress.org/aerc/2006/papers/31.

- Willems, M.; Dalvie, M.A.; London, L.; Rother, H.-A. Environmental Reviews and Case Studies: Health Risk Perception Related to Fracking in the Karoo, South Africa. Environ. Pr. 2016, 18, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upham, P. , Bögel, P. and Johansen, K., 2019. Energy transitions and social psychology: A sociotechnical perspective. Routledge.

- Colvin, R. Social identity in the energy transition: an analysis of the “Stop Adani Convoy” to explore social-political conflict in Australia. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 66, 101492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghard, U. , Breitschopf, B., Wohlfarth, K., Müller, F. and Keil, J., 2021. Perception of monetary and non-monetary effects on the energy transition: Results of a mixed method approach (No. S04/2021). Working Paper Sustainability and Innovation.

- Ivanovski, K.; Marinucci, N. Policy uncertainty and renewable energy: Exploring the implications for global energy transitions, energy security, and environmental risk management. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 82, 102415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, H.; López, S.R. The study of culture, ethnicity, and race in American psychology. American psychologist 1993, 48, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, S. Transformational innovation: A journey by narrative. Strategy & leadership 2005, 33, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, L.; Dale, A. The role of agency in sustainable local community development. Local Environ. 2005, 10, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slee, B.; Burlando, C.; Pisani, E.; Secco, L.; Polman, N. Social innovation: a preliminary exploration of a contested concept. Local Environ. 2021, 26, 791–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonthuys, E. (Un) thinking Citizenship: Feminist Debates in Contemporary South Africa, Amanda Gouws (ed): book review. South African Journal on Human Rights 2005, 21, 501–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, H. Talking of Change: Constructing Social Identities in South African Media Debates. Soc. Identit- 2005, 11, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booysen, L.A.; Nkomo, S.M. Gender role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics: The case of South Africa. Gender in Management: An international journal 2010, 25, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilliers, F.; Smit, B. A systems psychodynamic interpretation of South African diversity dynamics: A comparative study. South African Journal of Labour Relations 2006, 30, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Booysen, L. Societal power shifts and changing social identities in South Africa: workplace implications. South Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2013, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irene, B.N.O. , 2019. Technopreneurship: a discursive analysis of the impact of technology on the success of women entrepreneurs in South Africa. Digital Entrepreneurship in Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges, Opportunities and Prospects, pp.147-173.

- Booysen, F. Social grants as safety net for HIV/AIDS-affected households in South Africa. SAHARA-J: J. Soc. Asp. HIV/AIDS 2004, 1, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngambi, H. , 2002. The role of emotional intelligence in transforming South African organisations. In Proceedings of the international and Management Sciences Conference (pp. 221-231).

- Booysen, S. The will of the parties versus the will of the people? Defections, elections, and alliances in South Africa. Party Politics 2006, 12, 727–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccas, S.; Brewer, M.B. Social identity complexity. Personality and social psychology review 2002, 6, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, N. Social Identity Under Various Sociocultural Conditions. Russ. Educ. Soc. 2005, 47, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooney, J.G.; Woodrum, E.; Hoban, T.J.; Clifford, W.B. Environmental worldview and behavior: Consequences of dimensionality in a survey of North Carolinians. Environment and Behavior 2003, 35, 763–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesse, B.-J.; Heinrichs, H.U.; Kuckshinrichs, W. Adapting the theory of resilience to energy systems: a review and outlook. Energy, Sustain. Soc. 2019, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; Kern, F.; Fuchs, G.; Hinderer, N.; Kungl, G.; Mylan, J.; Neukirch, M.; Wassermann, S. The enactment of socio-technical transition pathways: A reformulated typology and a comparative multi-level analysis of the German and UK low-carbon electricity transitions (1990–2014). Res. Policy 2016, 45, 896–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.; Sophoulis, C.M.; Iosifides, T.; Botetzagias, I.; Evangelinos, K. The influence of social capital on environmental policy instruments. Environ. Politi- 2009, 18, 595–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tonder, E.; Fullerton, S.; De Beer, L.; Saunders, S. Social and personal factors influencing green customer citizenship behaviours: The role of subjective norm, internal values and attitudes. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellemers, N.; Kortekaas, P.; Ouwerkerk, J.W. Self-categorisation, commitment to the group and group self-esteem as related but distinct aspects of social identity. European journal of social psychology 1999, 29, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.Y.B.; Ting, C.-W.; Fei, Y.-M. A Multilevel Model of Environmentally Specific Social Identity in Predicting Environmental Strategies: Evidence from Technology Manufacturing Businesses. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.I.; Fielding, K.S.; Louis, W.R. Energizing and De-Motivating Effects of Norm-Conflict. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 39, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.I.; Fielding, K.S.; Louis, W.R. Conflicting Norms Highlight the Need for Action. Environ. Behav. 2012, 46, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ha, S. Understanding pro-environmental behavior: A comparison of sustainable consumers and apathetic consumers. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 2012, 40, 388–403. [Google Scholar]

- White, K.; Argo, J.J.; Sengupta, J. Dissociative versus Associative Responses to Social Identity Threat: The Role of Consumer Self-Construal. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 704–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Torres, C.; Parra-López, C.; Groot, J.C.; Rossing, W.A. Collective action for multi-scale environmental management: Achieving landscape policy objectives through cooperation of local resource managers. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 103, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, K.J.; Cradock-Henry, N.A.; Koch, F.; Patterson, J.; Häyhä, T.; Vogt, J.; Barbi, F. Implementing the “Sustainable Development Goals”: towards addressing three key governance challenges—collective action, trade-offs, and accountability. Current opinion in environmental sustainability 2017, 26, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapucu, N.; Beaudet, S. Network Governance for Collective Action in Implementing United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalof, L. , Dietz, T., Guagnano, G. and Stern, P.C., 2002. Race, gender, and environmentalism: The atypical values and beliefs of white men. Race, Gender & Class, pp.112-130.

- Pearson, A.R. , Ballew, M.T., Naiman, S. and Schuldt, J.P., 2017. Race, class, gender, and climate change communication. In Oxford research encyclopedia of climate science.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. , 1979. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard university press.

- Schultz, P.W.; Tabanico, J. Self, identity, and the natural environment: exploring implicit connections with nature 1. Journal of applied social psychology 2007, 37, 1219–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, K.; Kim, H.S.; Sherman, D.K. Social class, control, and action: Socioeconomic status differences in antecedents of support for pro-environmental action. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 77, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour-Smith, S. , 2009. Group Identity. Men, masculinities and health: Critical perspectives, p.93.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.; Prosser, A.; Evans, D.; Reicher, S. Identity and Emergency Intervention: How Social Group Membership and Inclusiveness of Group Boundaries Shape Helping Behavior. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasko, M.M.; Faraj, S. “It is what one does”: why people participate and help others in electronic communities of practice. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 2000, 9, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, S.R.; Shutts, K.; Olson, K.R. Social class differences produce social group preferences. Dev. Sci. 2014, 17, 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Wang, Y.; Oh, J. Digital Media Use and Social Engagement: How Social Media and Smartphone Use Influence Social Activities of College Students. Cyberpsychology, Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016, 19, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, P.H. ; Iii Organizations as Agents of Mobilization: How Does Group Activity Affect Political Participation? Am. J. Politi- Sci. 1982, 26, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinchcombe, A.L. , 2000. Social structure and organizations. In Economics meets sociology in strategic management (pp. 229-259). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Keefe, S. Ethnic Identity: The Domain of Perceptions of and Attachment to Ethnic Groups and Cultures. Hum. Organ. 1992, 51, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, N.M.; Martin, E.C. Sense of community responsibility at the forefront of crisis management. Adm. Theory Prax. 2020, 44, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.B.; Inder, P.M. Social Interaction in Same and Cross Gender Preschool Peer Groups: a participant observation study. Educ. Psychol. 1993, 13, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desforges, D.M.; Lord, C.G.; Ramsey, S.L.; Mason, J.A.; Van Leeuwen, M.D.; West, S.C.; Lepper, M.R. Effects of structured cooperative contact on changing negative attitudes toward stigmatized social groups. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndubuisi, O.G. Green House Effect and Global Climate Change: The African Perspective. RPH-International Journal of Applied Science 2023, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, F.M.; Jain, H. An assessment of employment equity and Broad Based Black Economic Empowerment developments in South Africa. Equal. Divers. Inclusion: Int. J. 2011, 30, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, S.H.; Nightingale, A.J.; Eakin, H. Reframing adaptation: The political nature of climate change adaptation. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 35, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, A.J. Power and politics in climate change adaptation efforts: Struggles over authority and recognition in the context of political instability. Geoforum 2017, 84, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liere, K.D.V.; Dunlap, R.E. The social bases of environmental concern: A review of hypotheses, explanations, and empirical evidence. Public opinion quarterly 1980, 44, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.E. Blacks and the environment: Toward an explanation of the concern and action gap between blacks and whites. Environment and behavior 1989, 21, 175–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohai, P. Black environmentalism. Social Science Quarterly 1990, 71, 744. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard, J.A.C. The Black-White Environmental Concern Gap: An Examination of Environmental Paradigms. J. Environ. Educ. 1995, 26, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambrel, P.A.; Cianci, R. Maslow’ s hierarchy of needs: Does it apply in a collectivist culture. Journal of Applied Management and Entrepreneurship 2003, 8, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, V.; DeRonda, A.; Ross, N.; Curtin, D.; Jia, F. Revisiting Environmental Belief and Behavior Among Ethnic Groups in the U.S. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. , 1970. Motivation and Personality, (rev. ed.) Harper and Row. New York.

- Hershey, M.R.; Hill, D.B. Is Pollution ‘A White Thing’? Racial Differences in Preadults’ Attitudes. Public Opin. Q. 1977, 41, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westra, L. and Lawson, B. eds., 2001. Faces of environmental racism: Confronting issues of global justice. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Medina, V.; DeRonda, A.; Ross, N.; Curtin, D.; Jia, F. Revisiting Environmental Belief and Behavior Among Ethnic Groups in the U.S. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, W.M. , 2005. Green development theory?: Environmentalism and sustainable development. In Power of development (pp. 85-96). Routledge.

- Feygina, I. and Henry, P.J., 2015. Culture and prosocial behavior. The Oxford handbook of prosocial behavior, pp.188-208.

- Bain, P.G.; Hornsey, M.J.; Bongiorno, R.; Jeffries, C. Promoting pro-environmental action in climate change deniers. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012, 2, 600–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).