Submitted:

06 November 2023

Posted:

07 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection Procedure

2.3. The Questionnaire

2.4. Statical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Sample

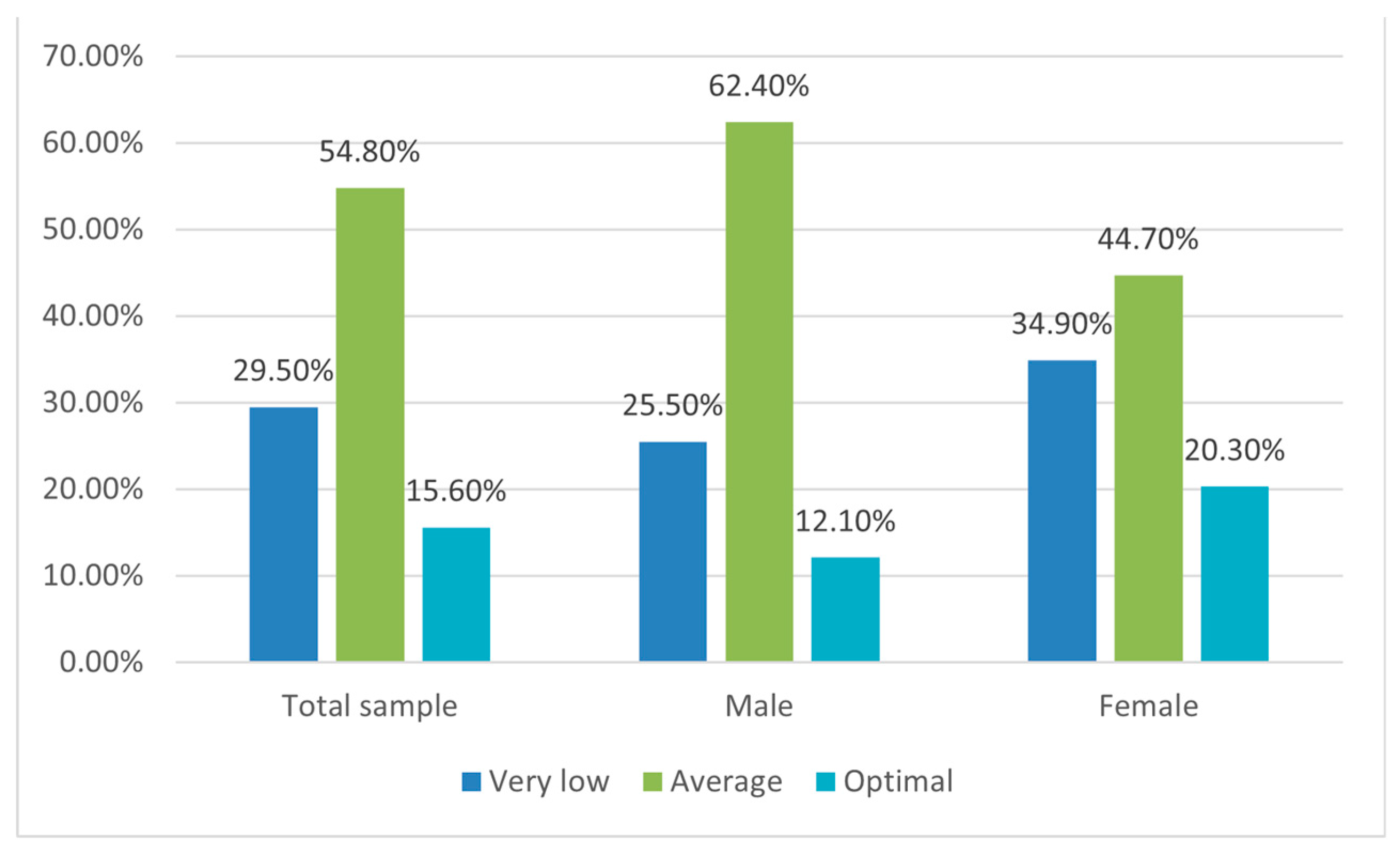

3.2. The Adherence to Mediterranean Diet Assessment (KIDMED Test)

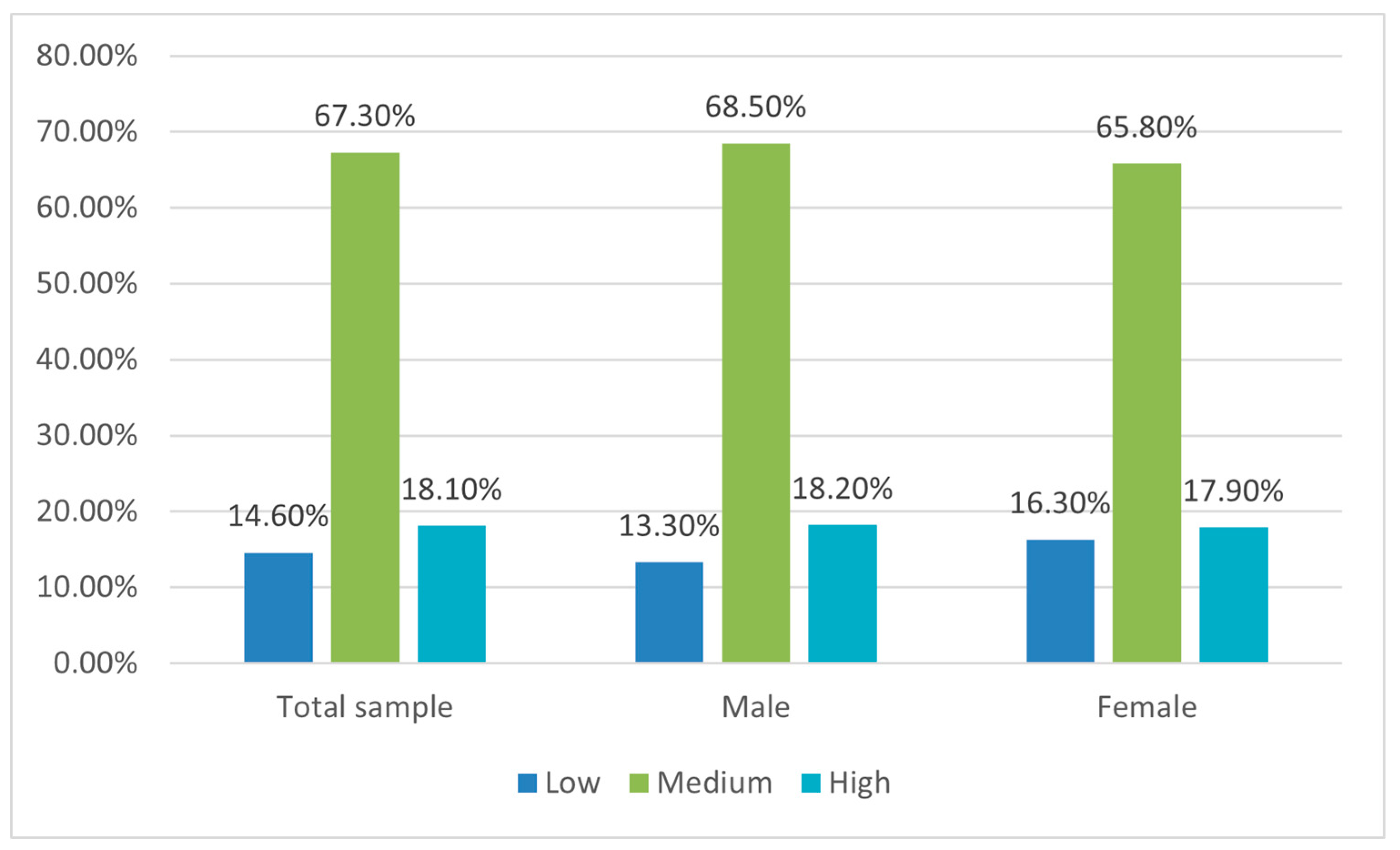

3.3. Food Neophobia Assessment

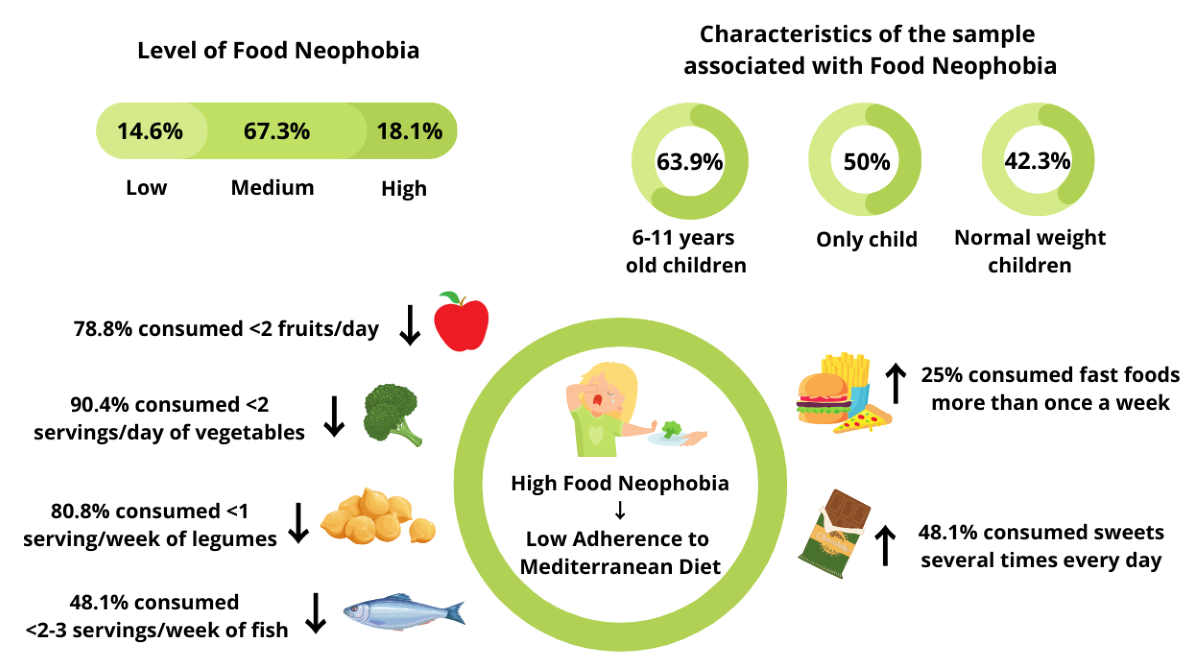

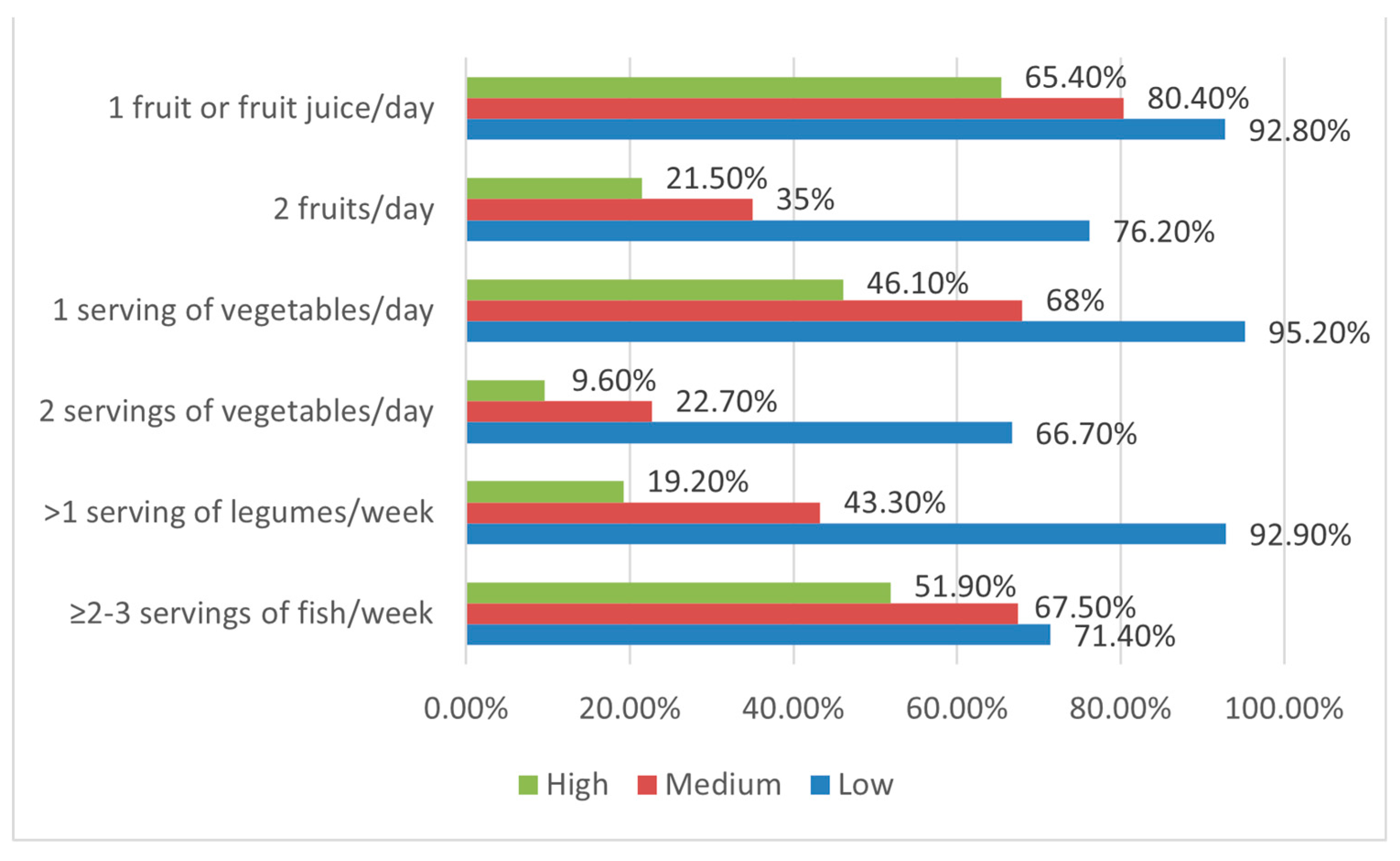

3.4. The Relationship between Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Food Neophobia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodríguez-Tadeo, A.; Patiño-Villena, B.; González-Martínez-La-Cuesta, E.; Urquídez-Romero, R.; Ros-Berruezo, G. Food Neophobia, Mediterranean Diet Adherence and Acceptance of Healthy Foods Prepared in Gastronomic Workshops by Spanish Students. Nutrición Hospitalaria 2018, 35, 642–649. [CrossRef]

- Dovey, T.M.; Staples, P.A.; Gibson, E.L.; Halford, J.C.G. Food Neophobia and ‘Picky/Fussy’ Eating in Children: A Review. Appetite 2008, 50, 181–193. [CrossRef]

- Cole, N.C.; An, R.; Lee, S.-Y.; Donovan, S.M. Correlates of Picky Eating and Food Neophobia in Young Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr Rev 2017, 75, 516–532. [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Prescott, J.; Worch, T. Food Neophobia Modulates Importance of Food Choice Motives: Replication, Extension, and Behavioural Validation. Food Quality and Preference 2022, 97, 104439. [CrossRef]

- Agnoli, C.; Krogh, V.; Grioni, S.; Sieri, S.; Palli, D.; Masala, G.; Sacerdote, C.; Vineis, P.; Tumino, R.; Frasca, G.; et al. A Priori-Defined Dietary Patterns Are Associated with Reduced Risk of Stroke in a Large Italian Cohort. J Nutr 2011, 141, 1552–1558. [CrossRef]

- Grosso, G.; Mistretta, A.; Frigiola, A.; Gruttadauria, S.; Biondi, A.; Basile, F.; Vitaglione, P.; D’Orazio, N.; Galvano, F. Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Systematic Review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2014, 54, 593–610. [CrossRef]

- Sofi, F.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A. Accruing Evidence on Benefits of Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet on Health: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis12. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2010, 92, 1189–1196. [CrossRef]

- Trichopoulou, A.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Tong, T.Y.; Forouhi, N.G.; Khandelwal, S.; Prabhakaran, D.; Mozaffarian, D.; de Lorgeril, M. Definitions and Potential Health Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet: Views from Experts around the World. BMC Med 2014, 12, 112. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eleftheriou, D.; Benetou, V.; Trichopoulou, A.; Vecchia, C.L.; Bamia, C. Mediterranean Diet and Its Components in Relation to All-Cause Mortality: Meta-Analysis. British Journal of Nutrition 2018, 120, 1081–1097. [CrossRef]

- Azzam, A. Is the World Converging to a ‘Western Diet’? Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 309–317. [CrossRef]

- Montaño, Z.; Smith, J.D.; Dishion, T.J.; Shaw, D.S.; Wilson, M.N. Longitudinal Relations between Observed Parenting Behaviors and Dietary Quality of Meals from Ages 2 to 5. Appetite 2015, 87, 324–329. [CrossRef]

- Torres, T. de O.; Gomes, D.R.; Mattos, M.P. FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH FOOD NEOPHOBIA IN CHILDREN: SYSTEMATIC REVIEW. Rev. paul. pediatr. 2021, 39, e2020089. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García Cabrera, S.; Herrera Fernández, N.; Rodríguez Hernández, C.; Nissensohn, M.; Román-Viñas, B.; Serra-Majem, L. KIDMED TEST; PREVALENCE OF LOW ADHERENCE TO THE MEDITERRANEAN DIET IN CHILDREN AND YOUNG; A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW. Nutr Hosp 2015, 32, 2390–2399. [CrossRef]

- EpiCentro Indagine nazionale 2019: i dati nazionali Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/okkioallasalute/indagine-2019-dati (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Russell, C.G.; Worsley, A. A Population-Based Study of Preschoolers’ Food Neophobia and Its Associations with Food Preferences. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 2008, 40, 11–19. [CrossRef]

- Falciglia, G.A.; Couch, S.C.; Gribble, L.S.; Pabst, S.M.; Frank, R. Food Neophobia in Childhood Affects Dietary Variety. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2000, 100, 1474–1481. [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.L.; Vander Schaaf, E.B.; Cohen, G.M.; Irby, M.B.; Skelton, J.A. Association of Picky Eating and Food Neophobia with Weight: A Systematic Review. Childhood Obesity 2016, 12, 247–262. [CrossRef]

- Perry, R.A.; Mallan, K.M.; Koo, J.; Mauch, C.E.; Daniels, L.A.; Magarey, A.M. Food Neophobia and Its Association with Diet Quality and Weight in Children Aged 24 Months: A Cross Sectional Study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2015, 12, 13. [CrossRef]

- Laureati, M.; Bertoli, S.; Bergamaschi, V.; Leone, A.; Lewandowski, L.; Giussani, B.; Battezzati, A.; Pagliarini, E. Food Neophobia and Liking for Fruits and Vegetables Are Not Related to Italian Children’s Overweight. Food Quality and Preference 2015, 40, 125–131. [CrossRef]

- Finistrella, V.; Manco, M.; Ferrara, A.; Rustico, C.; Presaghi, F.; Morino, G. Cross-Sectional Exploration of Maternal Reports of Food Neophobia and Pickiness in Preschooler-Mother Dyads. Journal of the American College of Nutrition 2012, 31, 152–159. [CrossRef]

- Cooke, L.J.; Haworth, C.M.; Wardle, J. Genetic and Environmental Influences on Children’s Food Neophobia. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2007, 86, 428–433. [CrossRef]

- Lafraire, J.; Rioux, C.; Giboreau, A.; Picard, D. Food Rejections in Children: Cognitive and Social/Environmental Factors Involved in Food Neophobia and Picky/Fussy Eating Behavior. Appetite 2016, 96, 347–357. [CrossRef]

- Kutbi, H.A.; Alhatmi, A.A.; Alsulami, M.H.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Albagar, S.M.; Mumena, W.A.; Mosli, R.H. Food Neophobia and Pickiness among Children and Associations with Socioenvironmental and Cognitive Factors. Appetite 2019, 142, 104373. [CrossRef]

- Kaar, J.L.; Shapiro, A.L.B.; Fell, D.M.; Johnson, S.L. Parental Feeding Practices, Food Neophobia, and Child Food Preferences: What Combination of Factors Results in Children Eating a Variety of Foods? Food Quality and Preference 2016, 50, 57–64. [CrossRef]

- Clayton, D.A. Socially Facilitated Behavior. The Quarterly Review of Biology 1978, 53, 373–392. [CrossRef]

- Lumeng, J.C.; Cardinal, T.M.; Jankowski, M.; Kaciroti, N.; Gelman, S.A. Children’s Use of Adult Testimony to Guide Food Selection. Appetite 2008, 51, 302–310. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review 1977, 84, 191–215. [CrossRef]

- Litterbach, E.V.; Campbell, K.J.; Spence, A.C. Family Meals with Young Children: An Online Study of Family Mealtime Characteristics, among Australian Families with Children Aged Six Months to Six Years. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 111. [CrossRef]

- Goldman, R.L.; Radnitz, C.L.; McGrath, R.E. The Role of Family Variables in Fruit and Vegetable Consumption in Pre-School Children. J Public Health Res 2012, 1, 143–148. [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.J.; Mallan, K.M.; Byrne, R.; Magarey, A.; Daniels, L.A. Toddlers’ Food Preferences. The Impact of Novel Food Exposure, Maternal Preferences and Food Neophobia. Appetite 2012, 59, 818–825. [CrossRef]

- Kral, T.V.E.; Rauh, E.M. Eating Behaviors of Children in the Context of Their Family Environment. Physiol Behav 2010, 100, 567–573. [CrossRef]

- Faith, M.S.; Heo, M.; Keller, K.L.; Pietrobelli, A. Child Food Neophobia Is Heritable, Associated with Less Compliant Eating, and Moderates Familial Resemblance for BMI. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013, 21, 1650–1655. [CrossRef]

- Kähkönen, K.; Rönkä, A.; Hujo, M.; Lyytikäinen, A.; Nuutinen, O. Sensory-Based Food Education in Early Childhood Education and Care, Willingness to Choose and Eat Fruit and Vegetables, and the Moderating Role of Maternal Education and Food Neophobia. Public Health Nutr 2018, 21, 2443–2453. [CrossRef]

- Scaglioni, S.; De Cosmi, V.; Ciappolino, V.; Parazzini, F.; Brambilla, P.; Agostoni, C. Factors Influencing Children’s Eating Behaviours. Nutrients 2018, 10, 706. [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Kong, K.L.; Eiden, R.D.; Sharma, N.N.; Xie, C. Sociodemographic Differences and Infant Dietary Patterns. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e1387-1398. [CrossRef]

- Iaccarino Idelson, P.; Scalfi, L.; Valerio, G. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2017, 27, 283–299. [CrossRef]

- Maiz, E.; Balluerka, N. Nutritional Status and Mediterranean Diet Quality among Spanish Children and Adolescents with Food Neophobia. Food Quality and Preference 2016, 52, 133–142. [CrossRef]

- Pourhoseingholi, M.A.; Vahedi, M.; Rahimzadeh, M. Sample Size Calculation in Medical Studies. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 2013, 6, 14–17.

- Predieri, S.; Sinesio, F.; Monteleone, E.; Spinelli, S.; Cianciabella, M.; Daniele, G.M.; Dinnella, C.; Gasperi, F.; Endrizzi, I.; Torri, L.; et al. Gender, Age, Geographical Area, Food Neophobia and Their Relationships with the Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet: New Insights from a Large Population Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1778. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WMA - The World Medical Association-Declaration of Helsinki.

- Sette, S.; Le Donne, C.; Piccinelli, R.; Arcella, D.; Turrini, A.; Leclercq, C. The Third Italian National Food Consumption Survey, INRAN-SCAI 2005–06 – Part 1: Nutrient Intakes in Italy. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2011, 21, 922–932. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group WHO Child Growth Standards Based on Length/Height, Weight and Age. Acta Paediatr Suppl 2006, 450, 76–85. [CrossRef]

- de Onis, M. Development of a WHO Growth Reference for School-Aged Children and Adolescents. Bull World Health Organ 2007, 85, 660–667. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pliner, P. Development of Measures of Food Neophobia in Children. Appetite 1994, 23, 147–163. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laureati, M.; Spinelli, S.; Monteleone, E.; Dinnella, C.; Prescott, J.; Cattaneo, C.; Proserpio, C.; De Toffoli, A.; Gasperi, F.; Endrizzi, I.; et al. Associations between Food Neophobia and Responsiveness to “Warning” Chemosensory Sensations in Food Products in a Large Population Sample. Food Quality and Preference 2018, 68, 113–124. [CrossRef]

- Kozioł-Kozakowska, A.; Piórecka, B.; Schlegel-Zawadzka, M. Prevalence of Food Neophobia in Pre-School Children from Southern Poland and Its Association with Eating Habits, Dietary Intake and Anthropometric Parameters: A Cross-Sectional Study. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1106–1114. [CrossRef]

- Di Nucci, A.; Scognamiglio, U.; Grant, F.; Rossi, L. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Food Habits and Neophobia in Children in the Framework of the Family Context and Parents’ Behaviors: A Study in an Italian Central Region. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 1070388. [CrossRef]

- Serra-Majem, L.; Ribas, L.; Ngo, J.; Ortega, R.M.; García, A.; Pérez-Rodrigo, C.; Aranceta, J. Food, Youth and the Mediterranean Diet in Spain. Development of KIDMED, Mediterranean Diet Quality Index in Children and Adolescents. Public Health Nutrition 2004, 7, 931–935. [CrossRef]

- Hinton, P.; McMurray, I.; Brownlow, C. SPSS Explained; Routledge: London, 2004; ISBN 978-0-203-64259-7.

- Laureati, M.; Cattaneo, C.; Bergamaschi, V.; Proserpio, C.; Pagliarini, E. School Children Preferences for Fish Formulations: The Impact of Child and Parental Food Neophobia: L aureati et al . J Sens Stud 2016, 31, 408–415. [CrossRef]

- Białek-Dratwa, A.; Szczepańska, E.; Szymańska, D.; Grajek, M.; Krupa-Kotara, K.; Kowalski, O. Neophobia—A Natural Developmental Stage or Feeding Difficulties for Children? Nutrients 2022, 14, 1521. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyman, M.B.; Abrams, S.A.; SECTION ON GASTROENTEROLOGY, HEPATOLOGY, AND NUTRITION; COMMITTEE ON NUTRITION Fruit Juice in Infants, Children, and Adolescents: Current Recommendations. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20170967. [CrossRef]

- Salvy, S.-J.; Kieffer, E.; Epstein, L.H. Effects of Social Context on Overweight and Normal-Weight Children’s Food Selection. Eat Behav 2008, 9, 190–196. [CrossRef]

- Cassells, E.L.; Magarey, A.M.; Daniels, L.A.; Mallan, K.M. The Influence of Maternal Infant Feeding Practices and Beliefs on the Expression of Food Neophobia in Toddlers. Appetite 2014, 82, 36–42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moding, K.J.; Stifter, C.A. Temperamental Approach/Withdrawal and Food Neophobia in Early Childhood: Concurrent and Longitudinal Associations. Appetite 2016, 107, 654–662. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, L.J.; Chambers, L.C.; Añez, E.V.; Wardle, J. Facilitating or Undermining? The Effect of Reward on Food Acceptance. A Narrative Review. Appetite 2011, 57, 493–497. [CrossRef]

- Bante, H.; Elliott, M.; Harrod, A.; Haire-Joshu, D. The Use of Inappropriate Feeding Practices by Rural Parents and Their Effect on Preschoolers’ Fruit and Vegetable Preferences and Intake. J Nutr Educ Behav 2008, 40, 28–33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galloway, A.T.; Fiorito, L.M.; Francis, L.A.; Birch, L.L. “Finish Your Soup”: Counterproductive Effects of Pressuring Children to Eat on Intake and Affect. Appetite 2006, 46, 318–323. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.C.; Holub, S.C. Maternal Feeding Practices Associated with Food Neophobia. Appetite 2012, 59, 483–487. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.L.; Davies, P.L.; Boles, R.E.; Gavin, W.J.; Bellows, L.L. Young Children’s Food Neophobia Characteristics and Sensory Behaviors Are Related to Their Food Intake. J Nutr 2015, 145, 2610–2616. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maternal Controlling Feeding Behaviours and Child Eating in Preschool-aged Children - MOROSHKO - 2013 - Nutrition & Dietetics - Wiley Online Library Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1747-0080.2012.01631.x (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Sarin, H.V.; Taba, N.; Fischer, K.; Esko, T.; Kanerva, N.; Moilanen, L.; Saltevo, J.; Joensuu, A.; Borodulin, K.; Männistö, S.; et al. Food Neophobia Associates with Poorer Dietary Quality, Metabolic Risk Factors, and Increased Disease Outcome Risk in Population-Based Cohorts in a Metabolomics Study. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2019, 110, 233–245. [CrossRef]

| n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Females | 123 | 42.7 |

| Males | 165 | 57.3 |

| Age | ||

| 3-5 years | 83 | 28.8 |

| 6-11 years | 205 | 71.2 |

| Ethnic group | ||

| African | 13 | 4.5 |

| Asiatic | 4 | 1.4 |

| Caucasian | 229 | 79.8 |

| Eurasian | 37 | 12.9 |

| Hispanic | 4 | 1.4 |

| Parents employment | ||

| Both parents employed | 253 | 87.8 |

| ≤1 parent employed | 35 | 12.2 |

| Household income | ||

| Up to 10.000 euros | 26 | 9 |

| Between 10.001 and 25.000 euros | 91 | 31.6 |

| Between 25.001-40.000 euros | 103 | 35.8 |

| Between 40.001 and more | 68 | 23.6 |

| Children per family | ||

| 1 | 108 | 37.5 |

| 2 | 145 | 50.3 |

| ≥2 | 35 | 12.2 |

| BMI | ||

| Underweight | 16 | 5.6 |

| Normal weight | 129 | 44.8 |

| Overweight | 60 | 20.8 |

| Obesity | 83 | 28.8 |

| AMD levels | Very low (≤3) | Average (4-7) | Optimal (≥8) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Socio-demographic characteristics and BMI | |||||||

| Gender | Males | 42 | 49.4 | 103* | 65.2 | 20 | 44.4 |

| Females | 43 | 50.6 | 55 | 34.8 | 25 | 55.5 | |

| Household income | < 10.000€ | 9 | 10.6 | 11 | 6.9 | 6 | 13.3 |

| 10.000 - 25.000 € | 28 | 32.9 | 46 | 29.1 | 17 | 37.8 | |

| 25.000 - 40.000 € | 30 | 35.3 | 62 | 39.2 | 11 | 24.4 | |

| > 40.000 € | 18 | 21.2 | 39 | 24.7 | 11 | 24.4 | |

| Parents employment | Both parents employed | 68 | 80 | 147* | 93 | 38 | 84.4 |

| ≤1 parent employed | 17 | 20 | 11 | 7 | 7 | 15.6 | |

| Children per family | 1 | 35 | 41.2 | 65 | 41.1 | 8 | 17.8 |

| 2 | 40 | 47.1 | 73 | 46.2 | 32* | 71.1 | |

| > 2 | 10 | 11.8 | 20 | 10.8 | 5 | 11.1 | |

| Ethnic group | African | 1 | 1.2 | 9 | 5.7 | 3 | 6.7 |

| Asiatic | 2 | 2.3 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 2.2 | |

| Caucasian | 69 | 81.2 | 129 | 82.2 | 31 | 68.9 | |

| Eurasian | 11 | 13 | 16 | 10.2 | 10 | 22.2 | |

| Hispanic | 2 | 2.3 | 2 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | |

| BMI | Underweight | 3 | 3.5 | 9 | 5.7 | 4 | 8.9 |

| Normal weight | 42 | 49.4 | 68 | 43 | 19 | 42.2 | |

| Overweight | 9 | 20 | 40 | 25.3 | 11 | 24.4 | |

| Obesity | 31 | 36.5 | 41 | 26 | 11 | 24.4 | |

| FN levels | Low | Medium | High | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Socio-demographic characteristics and BMI | |||||||

| Gender | Males | 22 | 52.4 | 113 | 58.2 | 30 | 57.7 |

| Females | 20 | 47.6 | 81 | 41.8 | 22 | 42.3 | |

| Household income | < 10.000€ | 2 | 4.8 | 19 | 9.8 | 5 | 9.6 |

| 10.000 - 25.000 € | 8 | 19 | 67 | 34.5 | 16 | 30.8 | |

| 25.000 - 40.000 € | 18 | 42.8 | 68 | 35.1 | 17 | 32.7 | |

| > 40.000 € | 14 | 33.3 | 40 | 20.6 | 14 | 26.9 | |

| Parents employment | Both parents employed | 40 | 95.2 | 170 | 87.6 | 43 | 82.7 |

| ≤1 parent employed | 2 | 4.8 | 24 | 12.4 | 9 | 17.3 | |

| Children per family | 1 | 7* | 16.7 | 75 | 38.7 | 26 | 50 |

| 2 | 25 | 59.5 | 98 | 50.5 | 22 | 42.3 | |

| > 2 | 10 | 23.8 | 21 | 10.8 | 4 | 7.7 | |

| Ethnic group | African | 2 | 4.8 | 10 | 5.2 | 1 | 1.9 |

| Asiatic | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2.1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Caucasian | 34 | 80.9 | 153 | 79.3 | 42 | 80.8 | |

| Eurasian | 6 | 14.3 | 22 | 11.4 | 9 | 17.3 | |

| Hispanic | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2.1 | 0 | 0 | |

| BMI | Underweight | 0 | 0 | 12 | 6.2 | 4 | 7.7 |

| Normal weight | 26 | 61.9 | 81 | 41.8 | 22 | 42.3 | |

| Overweight | 16 | 38.1 | 36 | 18.5 | 8 | 15.4 | |

| Obesity | 0* | 0 | 65 | 33.5 | 18 | 34.6 | |

| FN levels | Low | Medium | High | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| KIDMED total score | Very low | 1 | 2.4 | 57 | 29.4 | 27* | 51.9 |

| Average | 26 | 61.9 | 109 | 56.2 | 23 | 44.2 | |

| Optimal | 15 | 35.7 | 28 | 14.4 | 2 | 3.8 | |

| KIDMED Test components | |||||||

| Fruit or fruit juice every day | Yes | 39 | 92.9 | 156 | 80.4 | 34 | 65.4 |

| No | 3 | 7.1 | 38 | 19.6 | 18* | 34.6 | |

| Second fruit every day | Yes | 32* | 76.2 | 67 | 34.5 | 11 | 21.2 |

| No | 10 | 23.8 | 127 | 65.5 | 41 | 78.8 | |

| Fresh or cooked vegetables regularly once a day | Yes | 40* | 95.2 | 132 | 68 | 24 | 46.2 |

| No | 2 | 4.8 | 62 | 32 | 28 | 53.8 | |

| Fresh or cooked vegetables more than once a day | Yes | 28* | 66.7 | 44 | 22.7 | 5 | 9.6 |

| No | 14 | 33.3 | 150 | 77.3 | 47 | 90.4 | |

| Fish at least 2-3 times per week | Yes | 30 | 71.4 | 131 | 67.5 | 27 | 51.9 |

| No | 12 | 28.6 | 63 | 32.5 | 25* | 48.1 | |

| Fast-food more than once a week | Yes | 1 | 2.4 | 40 | 20.6 | 13 | 25 |

| No | 41* | 97.6 | 154 | 79.4 | 39 | 75 | |

| Legumes more than once a week | Yes | 39* | 92.9 | 84 | 43.3 | 10 | 19.2 |

| No | 3 | 7.1 | 110 | 56.7 | 42 | 80.8 | |

| Cereals or grains (bread, etc.) for breakfast | Yes | 13* | 31 | 35 | 18 | 6 | 11.5 |

| No | 29 | 69 | 159 | 82 | 46 | 88.5 | |

| Nuts at least 2–3 times per week | Yes | 7 | 16.7 | 56 | 28.9 | 10 | 19.2 |

| No | 35 | 83.3 | 138 | 71.1 | 42 | 80.8 | |

| Skips breakfast | Yes | 2 | 4.8 | 22 | 11.3 | 10 | 19.2 |

| No | 40 | 95.2 | 172 | 88.7 | 42 | 80.8 | |

| Dairy product for breakfast (yoghurt, milk, etc.) | Yes | 40 | 95.2 | 180 | 92.8 | 44 | 84.6 |

| No | 2 | 4.8 | 14 | 7.2 | 8 | 15.4 | |

| Commercially baked goods or pastries for breakfast | Yes | 36 | 85.7 | 156 | 80.4 | 43 | 82.7 |

| No | 6 | 14.3 | 38 | 19.6 | 9 | 17.3 | |

| Sweets and candy several times every day | Yes | 11 | 26.2 | 79 | 40.7 | 25 | 48.1 |

| No | 31 | 73.8 | 115 | 59.3 | 27 | 51.9 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).