Submitted:

01 November 2023

Posted:

02 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Method

2.1. Specification of the Material

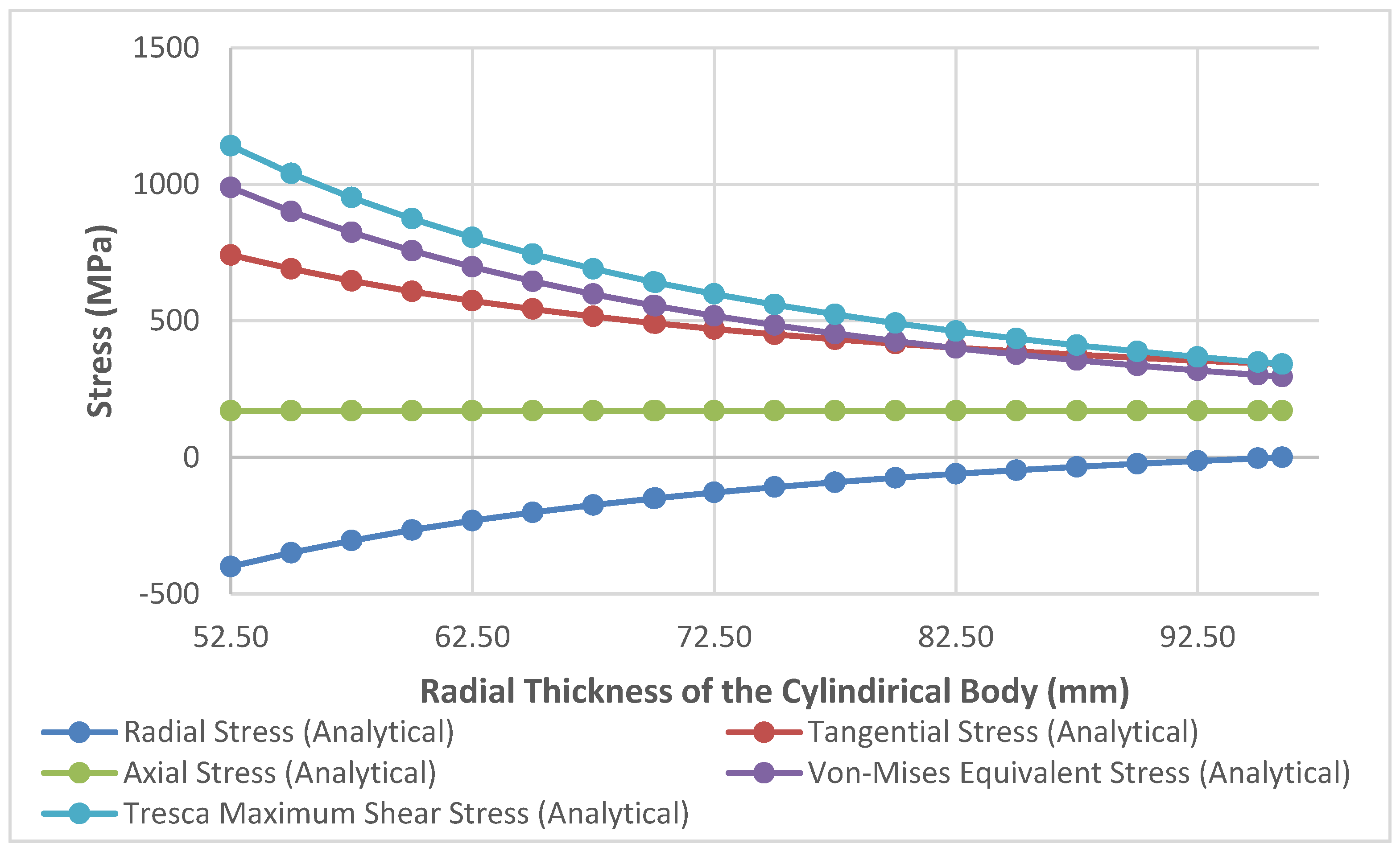

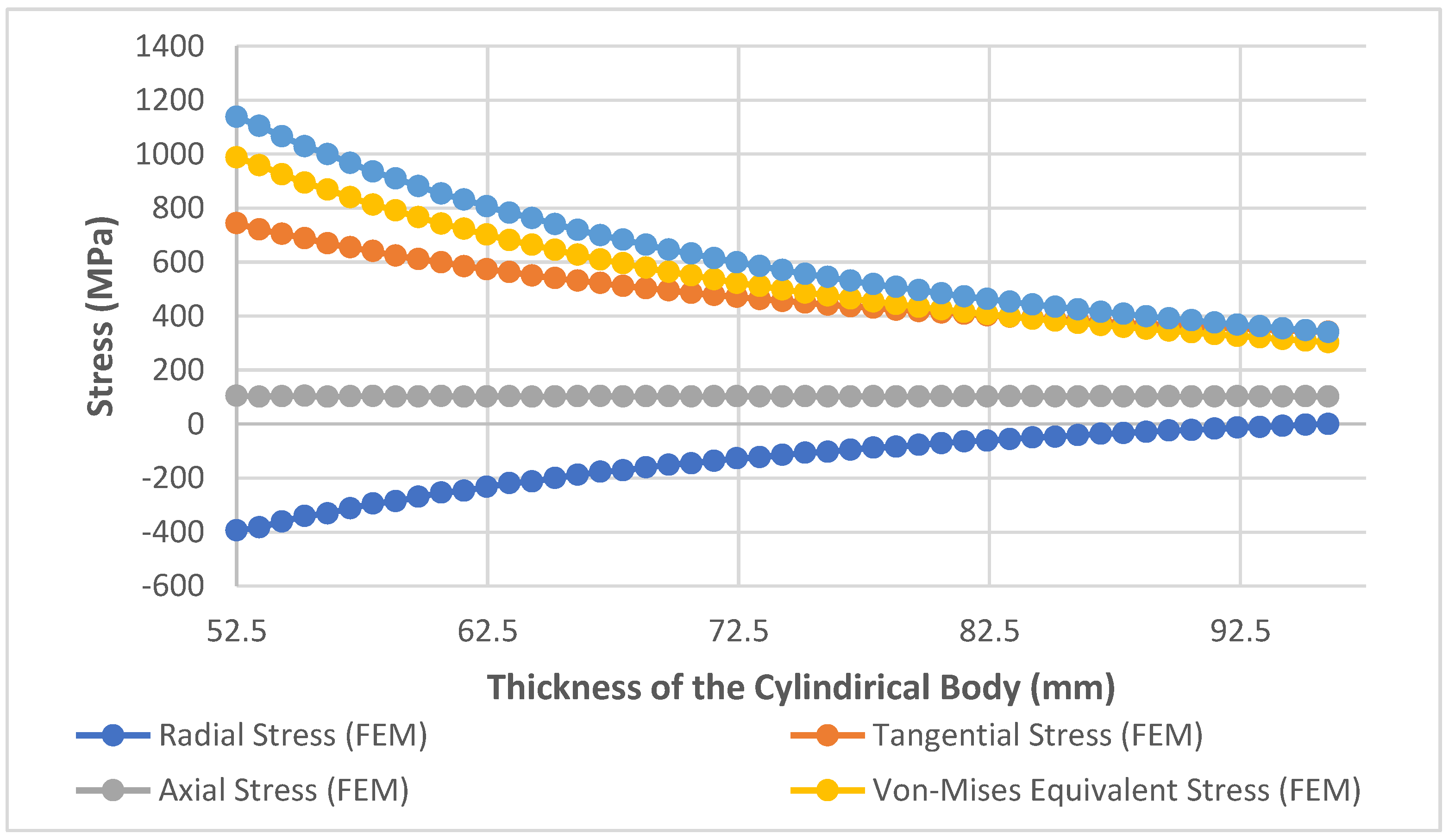

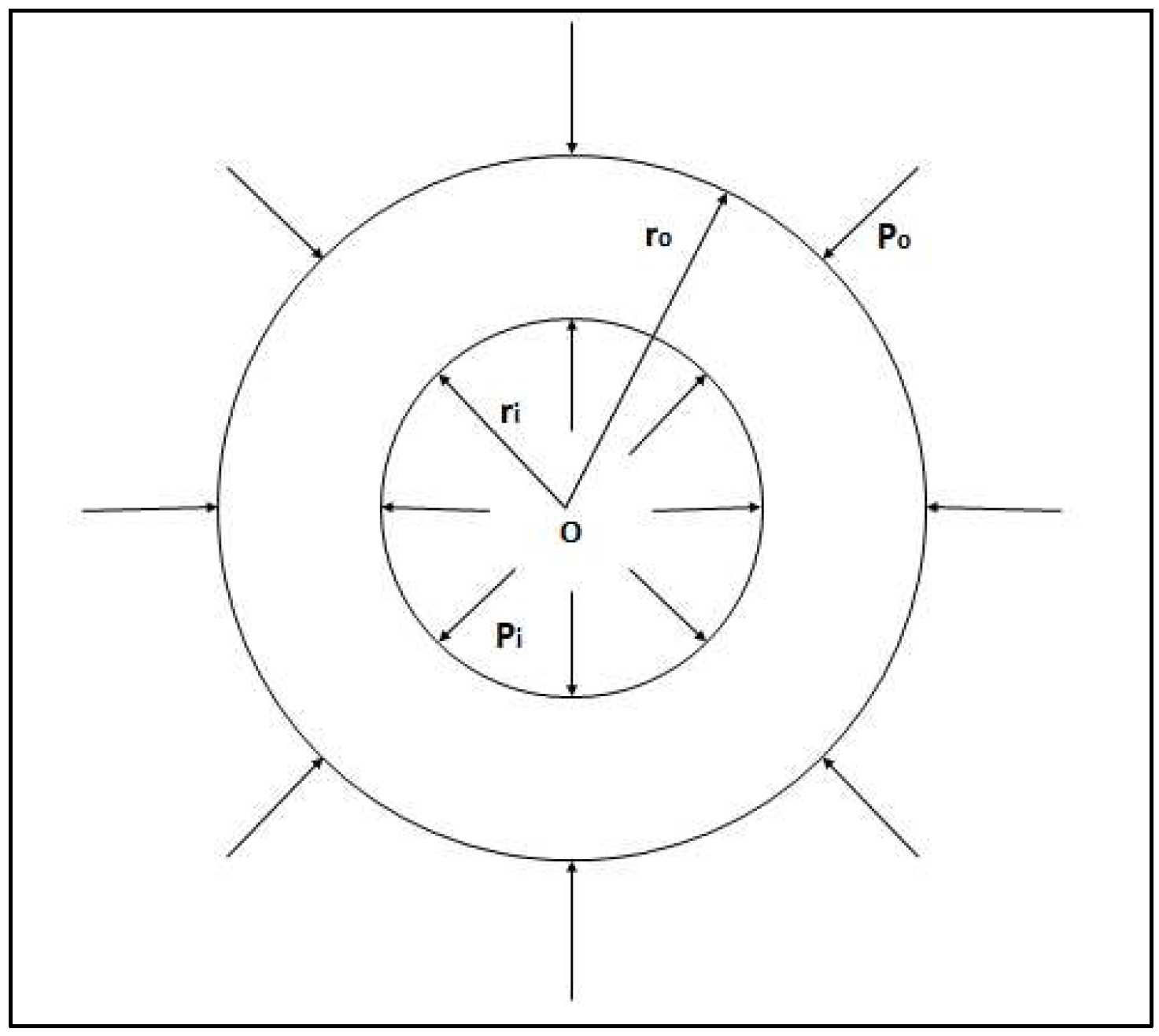

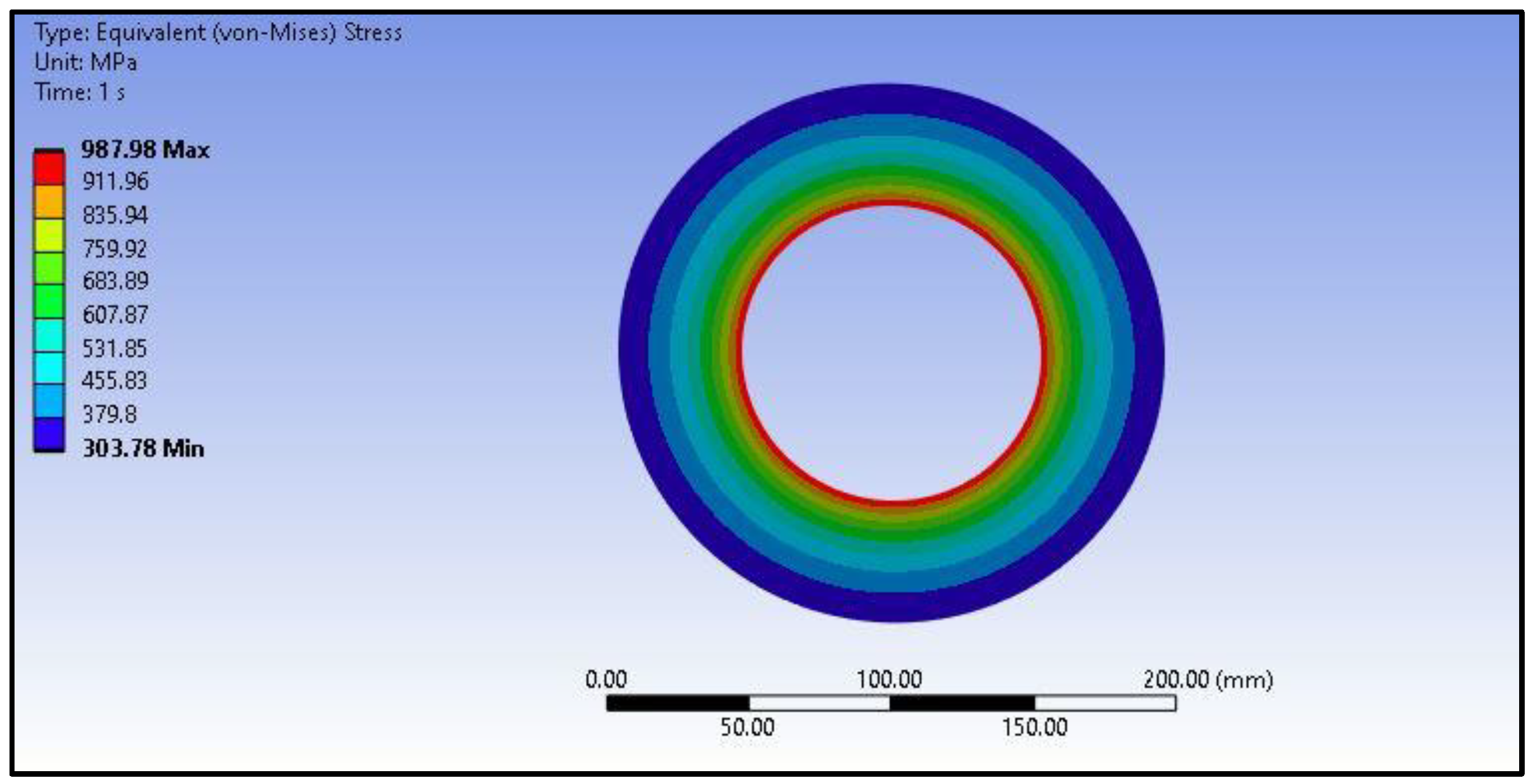

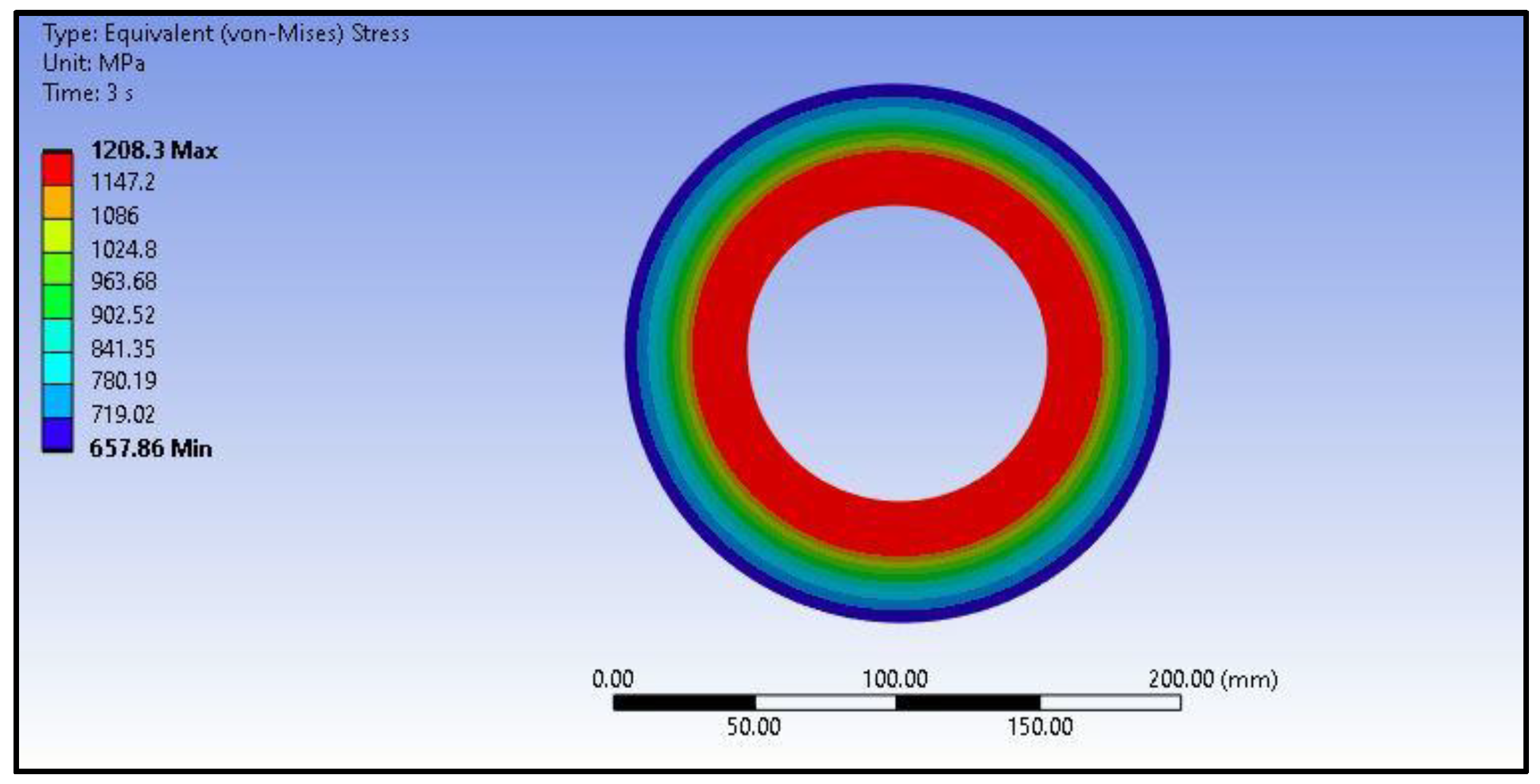

2.2. Calculation of Equivalent Stress Effects on the Component

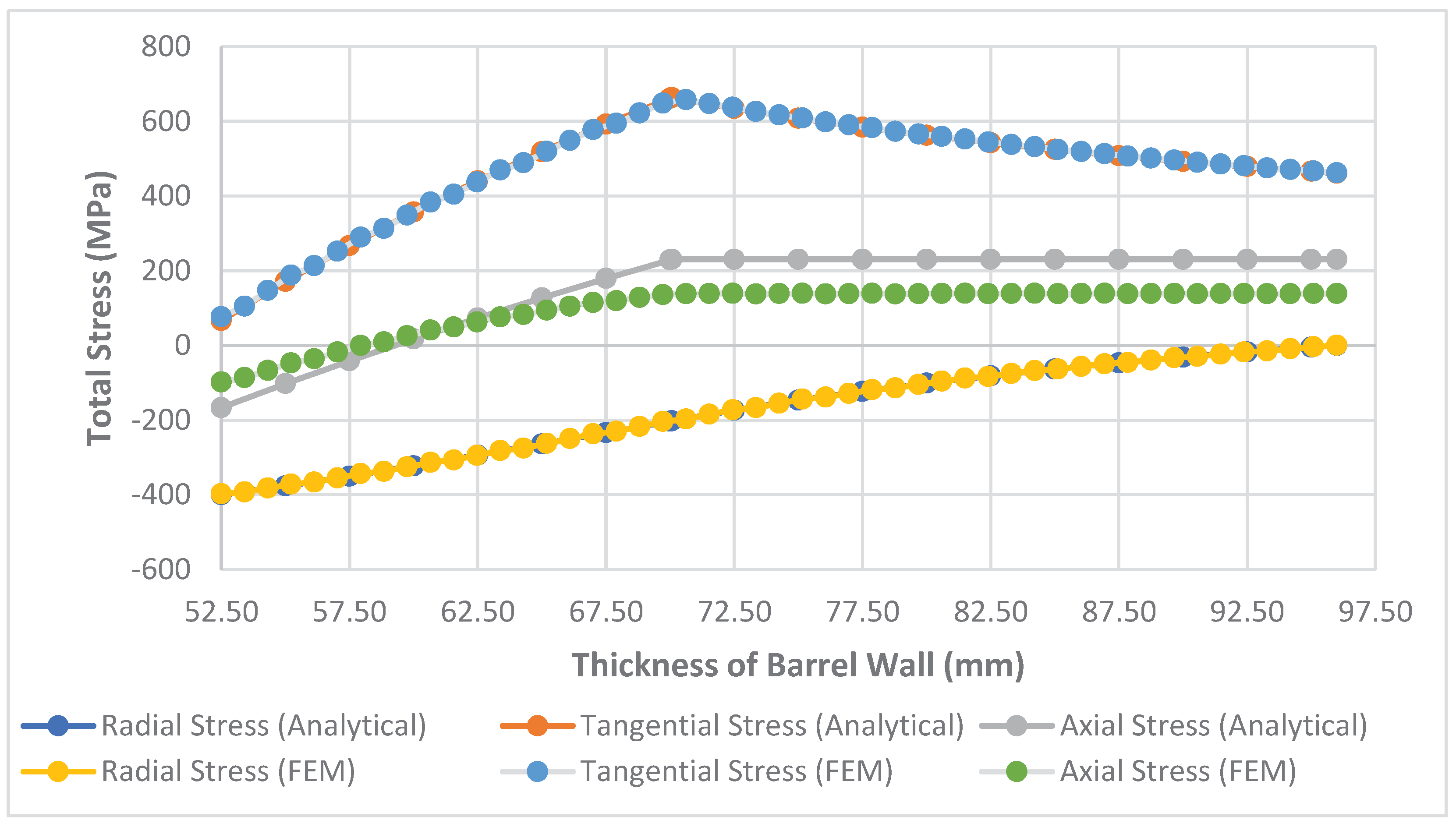

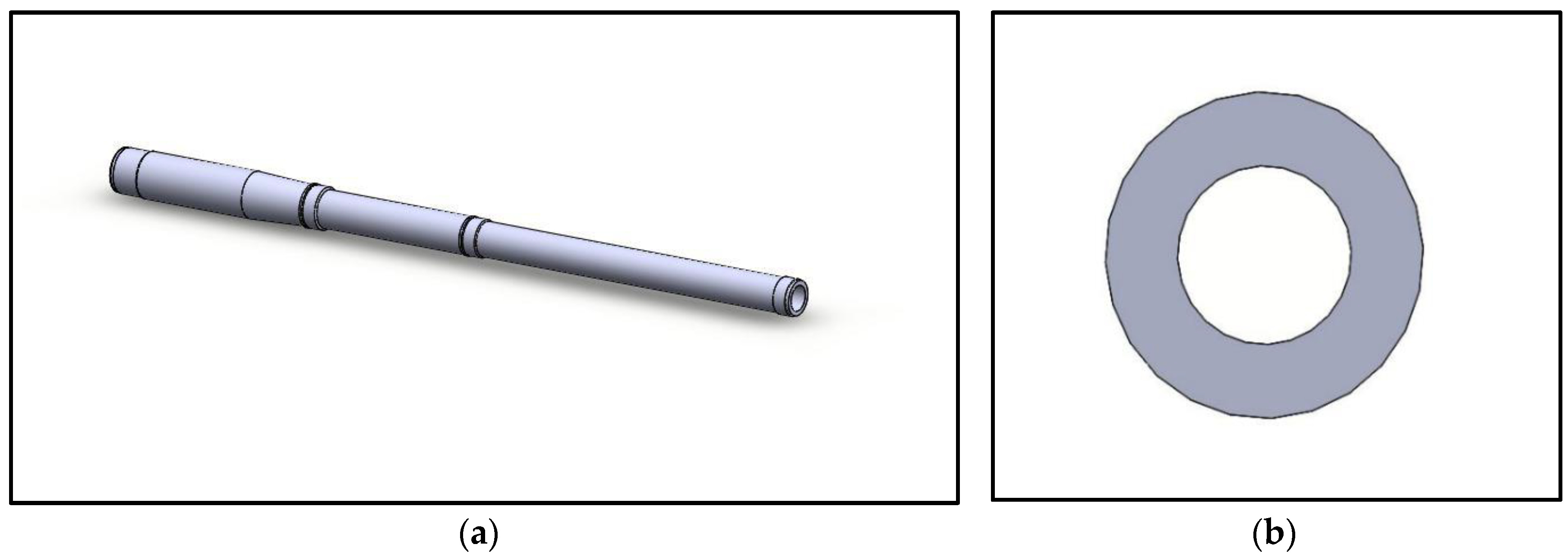

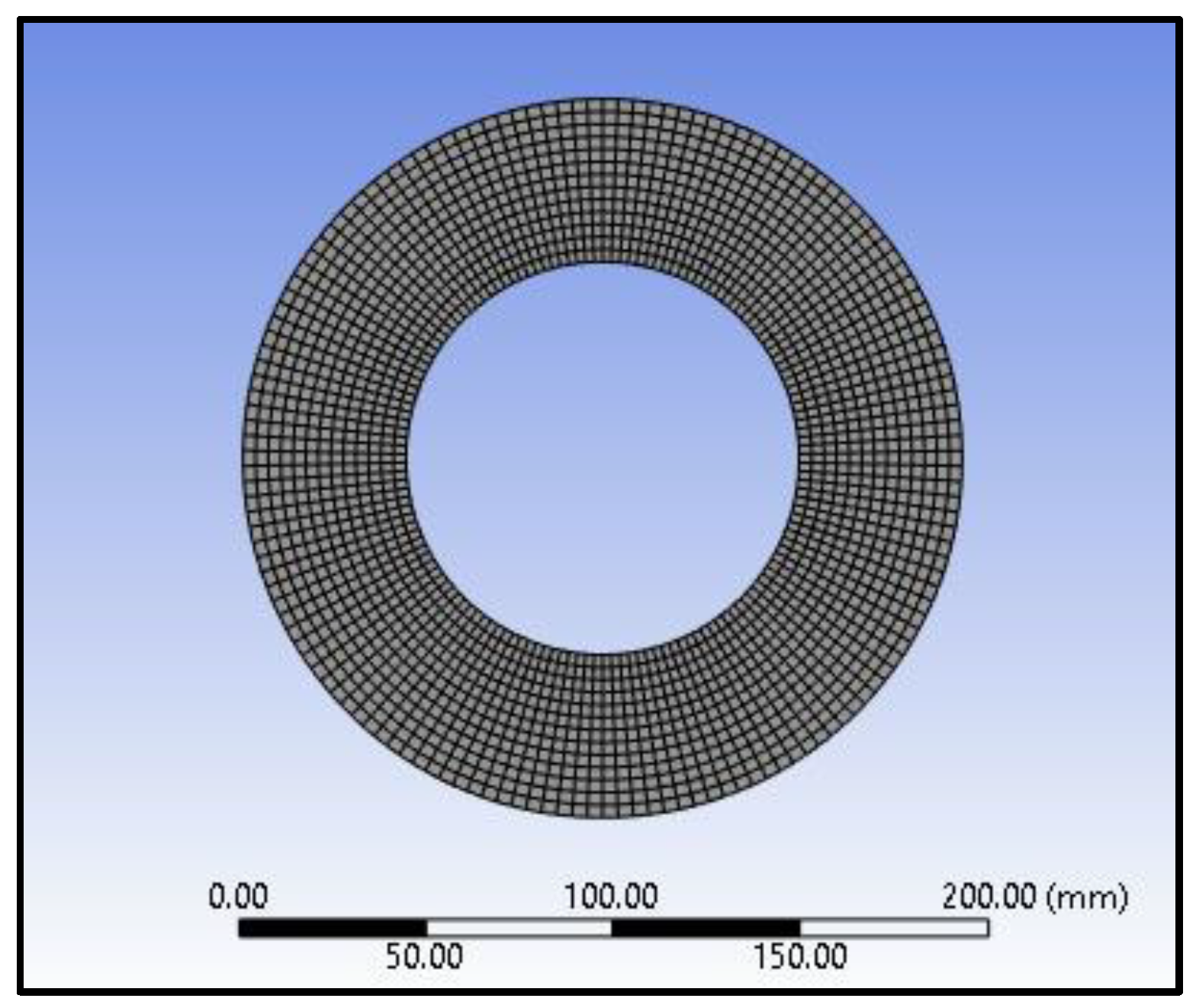

2.3. The Model and Forming of the Mesh Structure

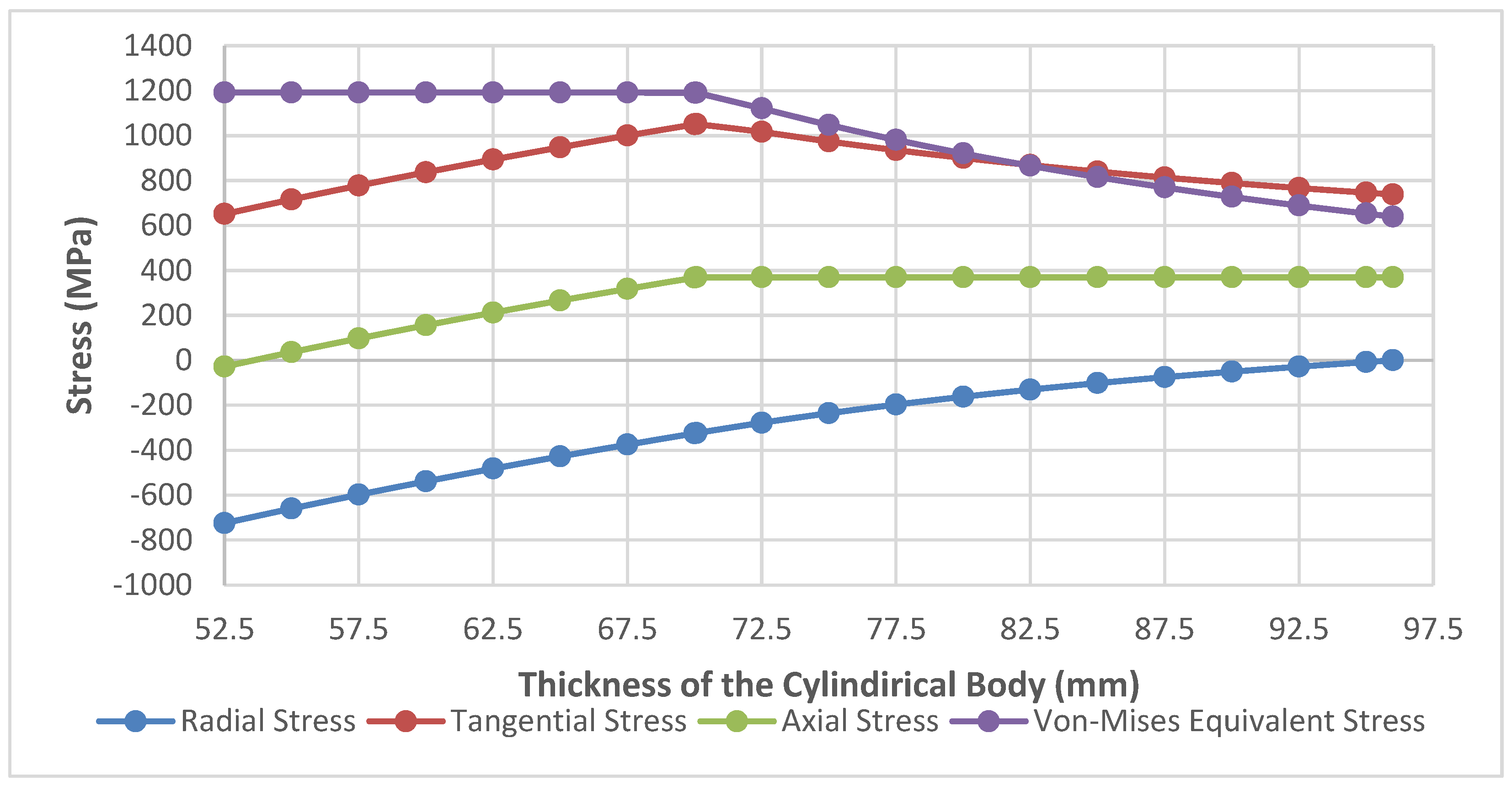

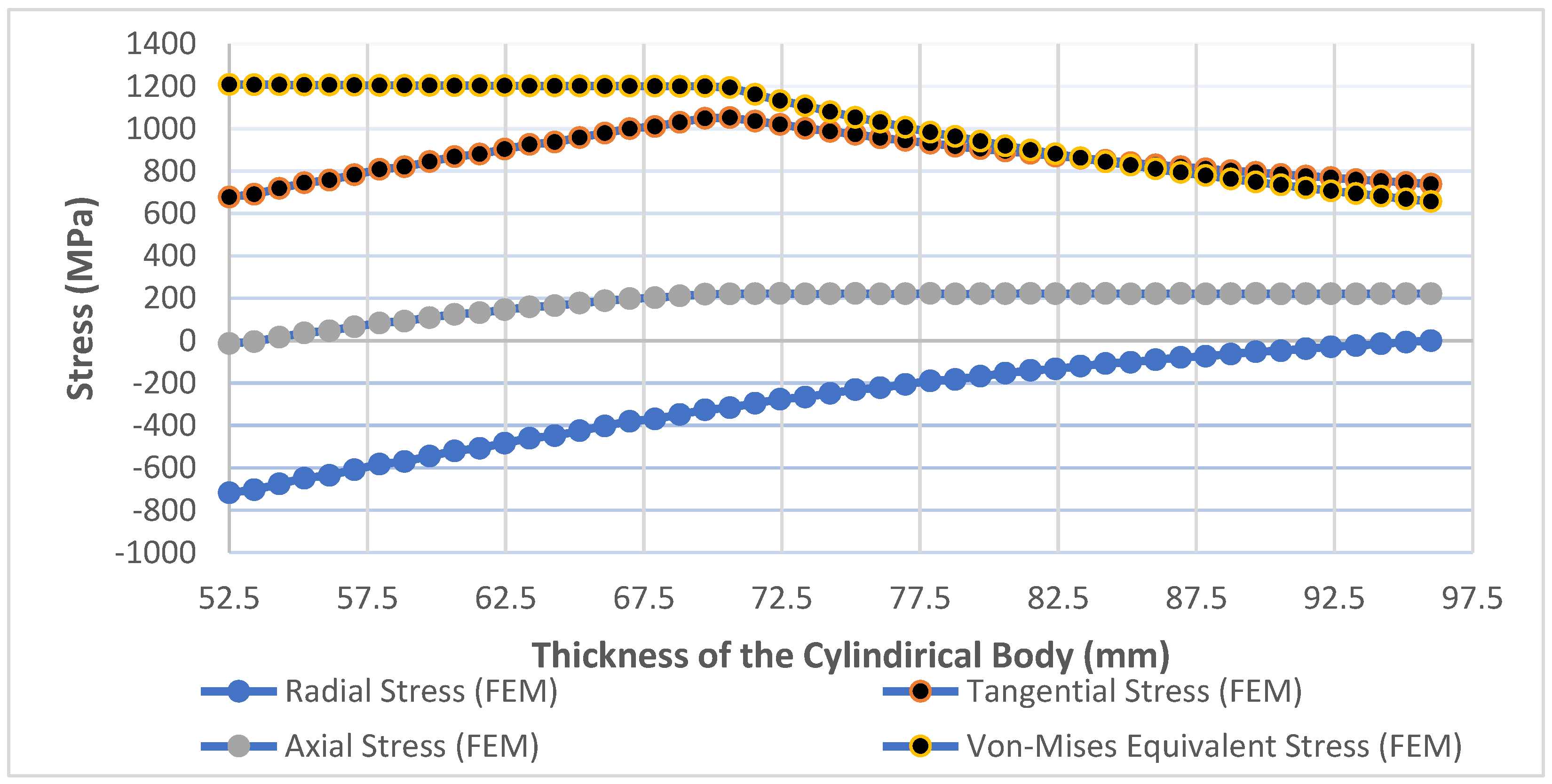

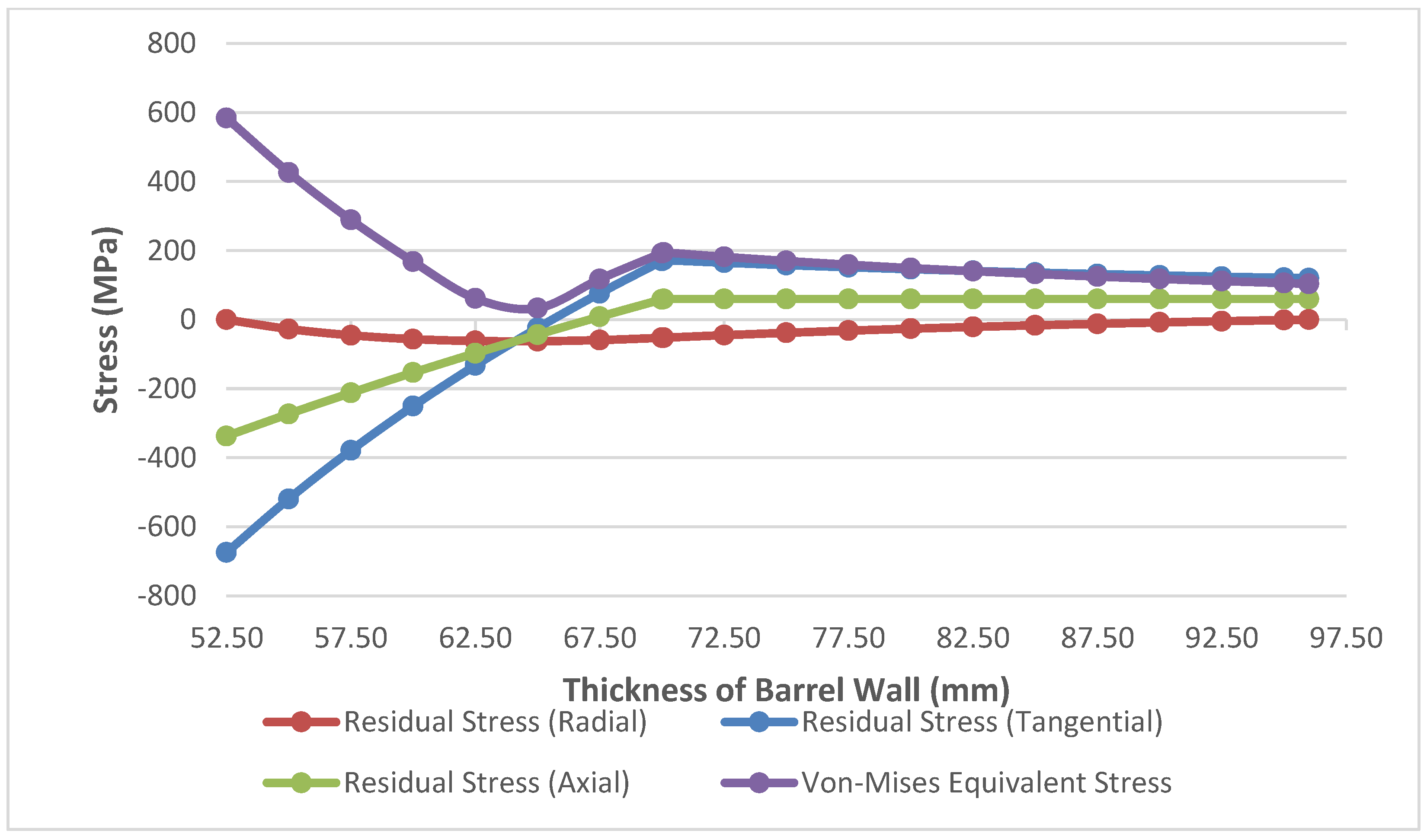

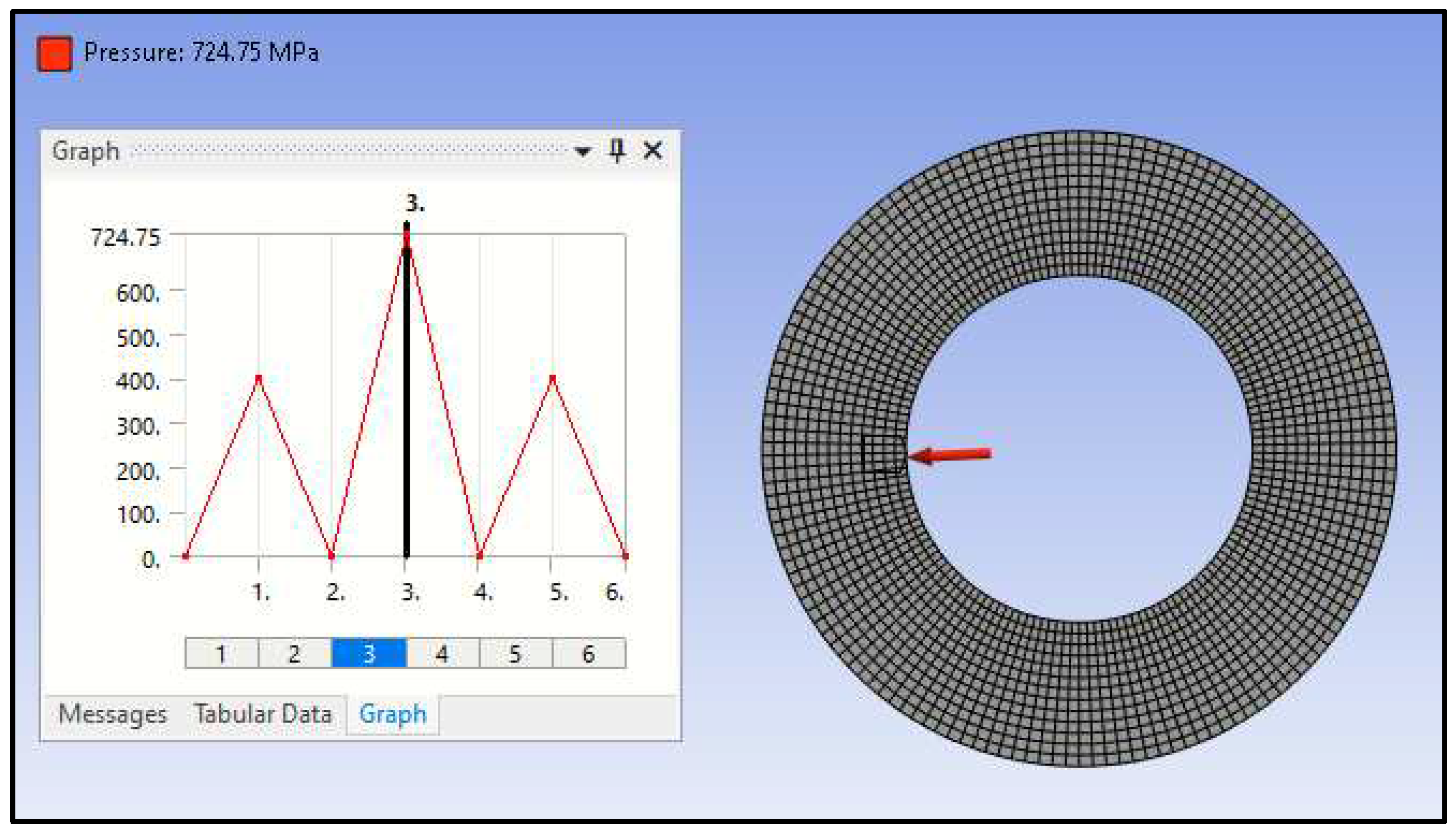

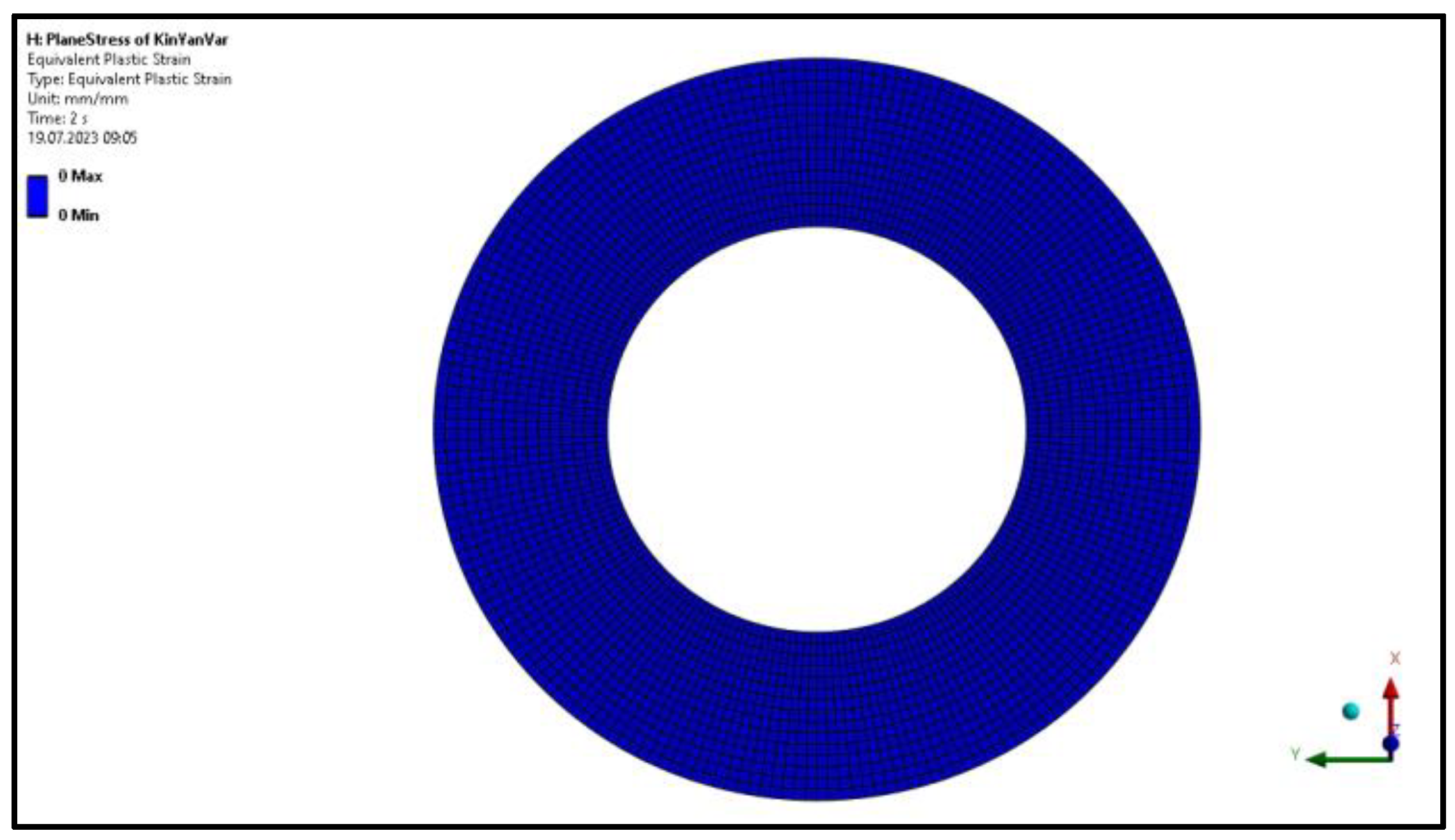

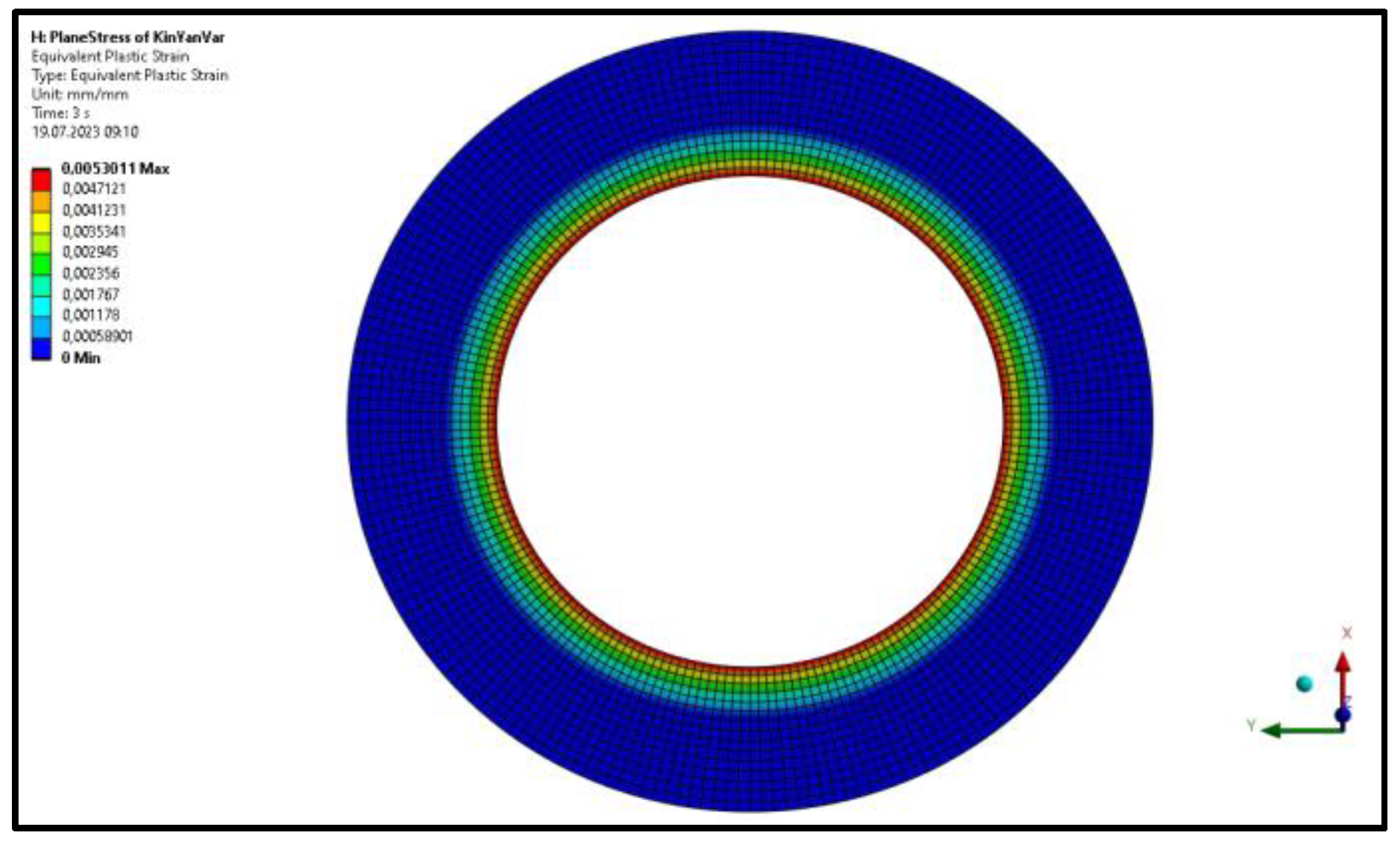

2.4. Autofrettage Application and Determination of Residual Stress

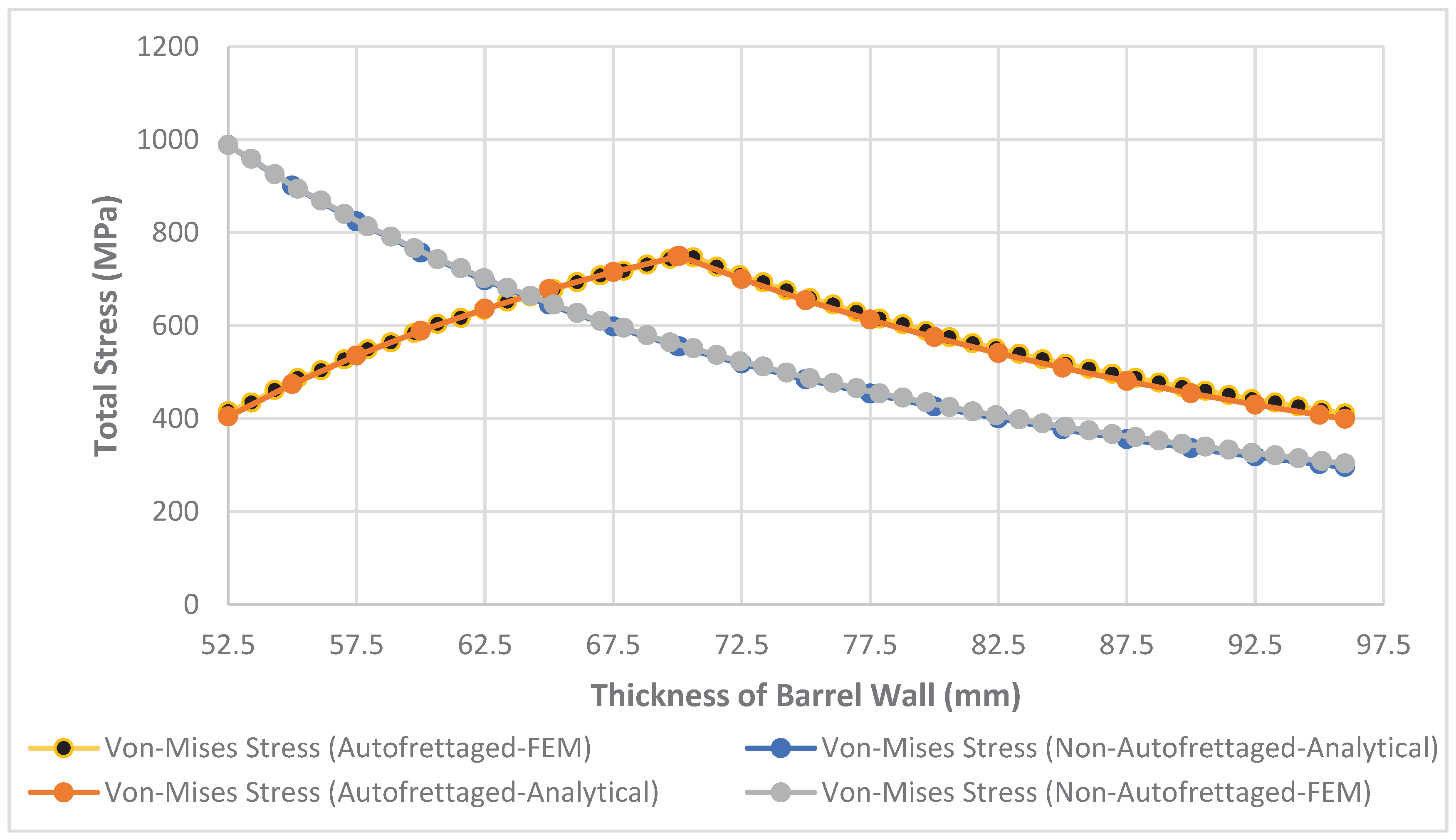

3. Conclusion

NOMENCLATURE

| P | Pressure |

| r | Radius |

| d | Diameter |

| t | Wall thickness of the cylinder |

| σ | Normal stress |

| υ | Poisson’s Ratio |

| T | Tangent Modulus |

| E | Elasticity Modulus |

| k | Outer radius/Inner radius ratio |

| n | Operating pressure/Yield stress ratio |

Subscripts

| i | Inner |

| o | Outer |

| a | Autofrettage |

| opt | Optimum |

| ser | Operating |

| VM | Von Mises |

| TR | Tresca |

| y | Yield |

| r | Radial |

| Ө | Tangential (Hoop) |

| l | Longitudinal (Axial) |

| R | Residual |

| Σ | Total |

Superscripts

| P | Plastic |

| E | Elastic |

References

- Shufen R., Dixit U. S. A Review of Theoretical and Experimental Research on Various Autofrettage Processes. Journal of Pressure Vessel Technology, ASME. (2018).

- Perl M., Arone R. An Axisymmetric Stress Release Method for Measuring the Autofrettage Level in Thick-Walled Cylinders—Part I: Basic Concept and Numerical Simulation. Journal of Pressure Vessel Technology, ASME. (1994); 116:384-388.

- Zare H.R., Darijani H. A Novel Autofrettage Method for Strengthening and Design of Thick-Walled Cylinders. Materials & Design. (2016); 105:366-374.

- David P. K. A Short History of High Pressure Technology From Bridgman to Division 3. Journal of Pressure Vessel Technology, ASME. (2000);122:229-233.

- Perl M., Perry J. An Experimental-Numerical Determination of the Three-Dimensional Autofrettage Residual Stress Field Incorporating Bauschinger Effects. Journal of Pressure Vessel Technology, ASME. (2006);128:173-178.

- Kassir M. Applied Elasticity and Plasticity. CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group. (2018);303.

- Vullo V. Circular Cylinders and Pressure Vessels Vincenzo Vullo Stress Analysis and Design. Springer International Publishing, Springer Series in Solid and Structural Mechanics. (2014);3:73.

- Subramanian BY R. Strength of Materials (2nd Edition). Oxford University Press. (2010);737.

- Chakrabarty J. Theory of Plasticity. Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann. (2006);333.

- Ma Q., Levy C., Perl M. A Study of the Combined Effects of Erosions, Cracks and Partial Autofrettageon the Stress Intensity Factors of a Thick Walled Pressurized Cylinder. Journal of Pressure Vessel Technology, ASME. (2013);135:041403:1:8.

- Kamal S. M. Analysis of Residual Stress in the Rotational Autofrettage of Thick-Walled Disks. Journal of Pressure Vessel Technology, ASME. (2018).

- Abdelsalam O. R., Sedaghati R. Design Optimization of Compound Cylinders Subjected to Autofrettage and Shrink-Fitting Processes. Journal of Pressure Vessel Technology, ASME. (2013);135:021209:1-11.

- Adibi-Asl R., Livieri P. Analytical Approach in Autofrettaged Spherical Pressure Vessels Considering the Bauschinger Effect. Journal of Pressure Vessel Technology, ASME. (2007);129:411-419.

- Brünnet H., Bähre D. Full Exploitation of Lightweight Design Potentials by Generating Pronounced Compressive Residual Stress Fields with Hydraulic Autofrettage. Advanced Materials Research. (2014);907:17-27.

- Ayob A., Elbasheer M. K. Optimum Autofrettage Pressure In Thick Cylinders. Jurnal Mekanikal. (2007);24:1-14.

- H. Yildirim. Analytical and Numerical Analysis of Swage Autofrettage Process Applied to Thick Walled Cylinders”, M.Sc. Thesis, Yıldırım Beyazıt University Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences. (2015);42.

- Hu Z., Parker A. P. Swage Autofrettage Analysis – Current Status and Future Prospects. International Journal of Pressure Vessels and Piping. (2019);233–241.

- Malik A. M., Khan M., Rashid B., Khushnood S. Analysis of Swage Autofrettage in Metal Tube. Conference Paper. International Conference on Nuclear Engineering. (2006).

- Hu Z. Design of Two-Pass Swage Autofrettage Processes of Thick-Walled Cylinders by Computer Modeling. Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science. (2018).

- Till E.T., Rammerstorfer F.G. Nonlinear Finite Element Analysis of an Autofrettage Process. Computers & Structures. (1983);17:54:857-864.

- Chen P.C.T. Finite Element Analysis of the Swage Autofrettage Process. Technical Report. US Army Armament Research, Development and Engineering Center. (1988).

- Iremonger M.J., Kalsi G.S. A Numerical Study of Swage Autofrettage. Journal of Pressure Vessel Technology. (2003);125:347.

- Barbachano H, J. M. Alegre, Cuesta I. I. Numerical Simulation of the Swage Tube Forming (STF) in Cylinders. International Journal of Materials Engineering and Technology. (2012).

- Dewangan M. K., Panigrahi S.K. Residual Stress Analysis of Swage Autofrettaged Gun Barrel Via Finite Element Method. Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology. (2015).

- Çelik V., Güngör O., Yıldırım H. Optimization of Mechanical (Swage) Autofrettage Process. Journal of the Faculty of Engineering and Architecture of Gazi University. (2018);34:2:855-863.

- Güngör O, Çelik V. Numerical Evaluation of an Autofrettaged Thick-Walled Cylinder Under Dynamically Applied Axially Non-Uniform Internal Service Pressure Distribution. Defence Technology. (2018).

- Güngör O. An Approach for Optimization of the Wall Thickness (Weight) of a Thick-Walled Cylinder Under Axially Non-Uniform Internal Service Pressure Distribution. Defence Technology. (2017).

- Afzaal Malik M., Khushnood S., Rashid B., Khan M. Hydraulic Autofrettage Technology: A Review. Proceedings of the 16 th International Conference on Nuclear Engineering. (2008).

- Dongxia L., Li L., Xinglei B. Analysis of Optimal Autofrettage Pressure on CFRP Pressure Vessels Using ANSYS. Applied Mechanics and Materials. (2013);184-188.

- Ashikhmin V. N., Gitman M. B., Trusov P. V. Optimal Design of Hydrolic Cylinders Subjected to Autofrettage. Strength of Materials. (1998);30:6.

- Ma X. Research on the Best Autofrettage Pressure of Ultra-High Pressure Valve Body. Key Engineering Materials. (2015);667:524-529.

- Perl M., Saley T. Swage and Hydraulic Autofrettage Impact on Fracture Endurance and Fatigue Life of an Internally Cracked Smooth Gun Barrel Part I- The Effect of Overstraining. Elsevier, Engineering Fracture Mechanics. (2017).

- Perl M., Saley T. Swage and Hydraulic Autofrettage Impact on Fracture Endurance and Fatigue Life of an Internally Cracked Smooth Gun Barrel Part II- The Combined Effect of Pressure and Overstraining. Elsevier, Engineering Fracture Mechanics. (2017).

- Moo Han S., Cheol Hwang B., Yoon Kim H., Kim C. Analysis of the Autofrettage Effect in Improving the Fatigue Resistance of Automotive CNG Storage Vessels. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing. (2009);10:15-21.

- Alegre J.M., Bravo P., Preciado M. Fatigue Behaviour of An Autofrettaged High-Pressure Vessel for the Food Industry. Elsevier, Engineering Failure Analysis. (2006).

- Çandar H., Filiz İ. H. Experimental Study on Residual Stresses in Autofrettaged Thick-Walled High Pressure Cylinders. High Pressure Research. (2017).

- Mustafa Kamal S. A Theoritical and Experimental Study of Thermal Autofrettage Process. PhD. Thesis, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Indian Enstitute of Technology. (2016).

- Berman I., Pai D. H. Elevated Temperature Autofrettage, Journal of Engineering for Power, ASME. (1967).

- Mustafa Kamal S. Dixit U.S. Feasibility Study of Thermal Autofrettage of Thick-Walled Cylinders. Journal of Pressure Vessel Technology, ASME. (2015);137.

- Shufen R., Dixit U.S. An Analysis of Thermal Autofrettage Process with Heat Treatment. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences. (2018).

- Mustafa Kamal S., Borsaikia A. C., Dixit U.S. Experimental Assessment of Residual Stresses Induced by the Thermal Autofrettage of Thick-Walled Cylinders. J Strain Analysis. (2015).

- Mustafa Kamal S. Estimation of Optimum Rotational Speed for Rotational Autofrettage of Disks Incorporating Bauschinger Effect. Mechanics Based Design of Structures and Machines. (2015).

- Jimmy D. Mote, Larry K. W. Ching, Robert E. Knight, Richard J. Fay’, and Michael A. Kaplan. Explosive Autofrettage of Cannon Barrels. Technical Report. (1971).

- Handbook of Comparative World Steel Standards. ASTM DS67A. (2002);35.

- Çandar H., Filiz İ.H. Optimum Autofrettage Pressure for a High Pressure Cylinder of a Waterjet Intensifier Pump. Universal Journal of Engineering Science. (2017).

- Boresi A.P., Schmidt R.J. Advanced Mechanics of Materials. (2002);108.

| Element | Ni | Cr | Mn | C | Mo | Si | S | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition Percent (%) | 1.65-2.00 | 0.70-0.90 | 0.60-0.80 | 0.38-0.43 | 0.20-0.30 | 0.20-0.35 | 0.040 | 0.035 |

| Designation | Yield (Tension) | Yield (Compression) | Yield (Ultimate) | Tangent Modulus | Elastisity Modulus | Poisson’s Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AISI 4340 Steel | 1200 (MPa) | 1130 (MPa) | 1270 (MPa) | 1489 (MPa) | 200 (GPa) | 0.3 |

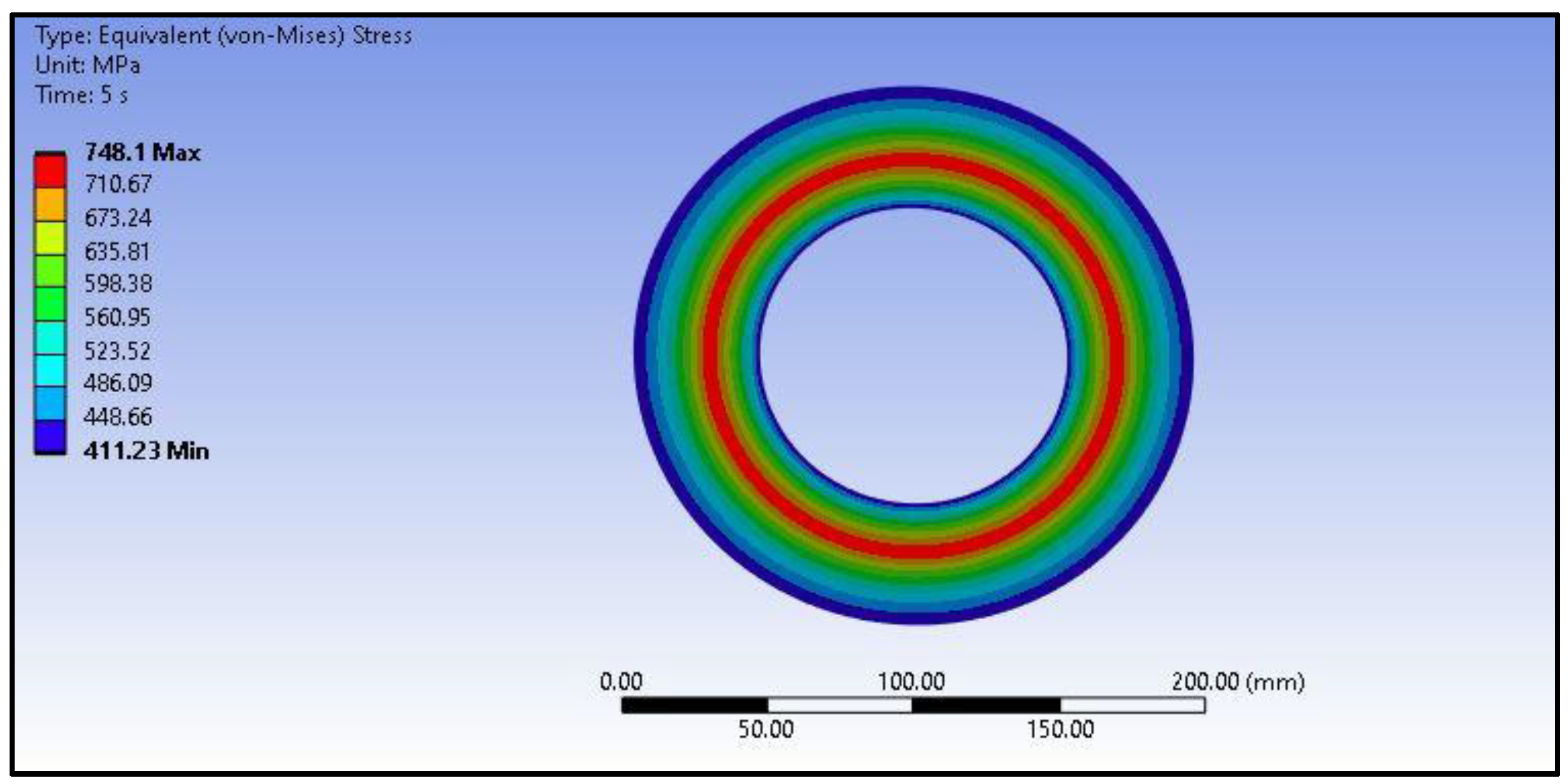

| Analytical Results (MPa) | Finite Element Results (MPa) | |

|---|---|---|

| Inner Radius | 404.32 | 415.39 |

| Elactic-Plastic Radius | 749.55 | 748.10 |

| Outer Radius | 399.29 | 411.23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).