Submitted:

01 November 2023

Posted:

02 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant material and virus infection

2.2. Sample collection and RNA extraction

2.3. Libraries construction and sequencing

2.4. RNA-Seq and sRNA data analysis

2.5. Virus-induced gene silencing

2.6. Quantitative real time PCR

2.7. Data availability

3. Results

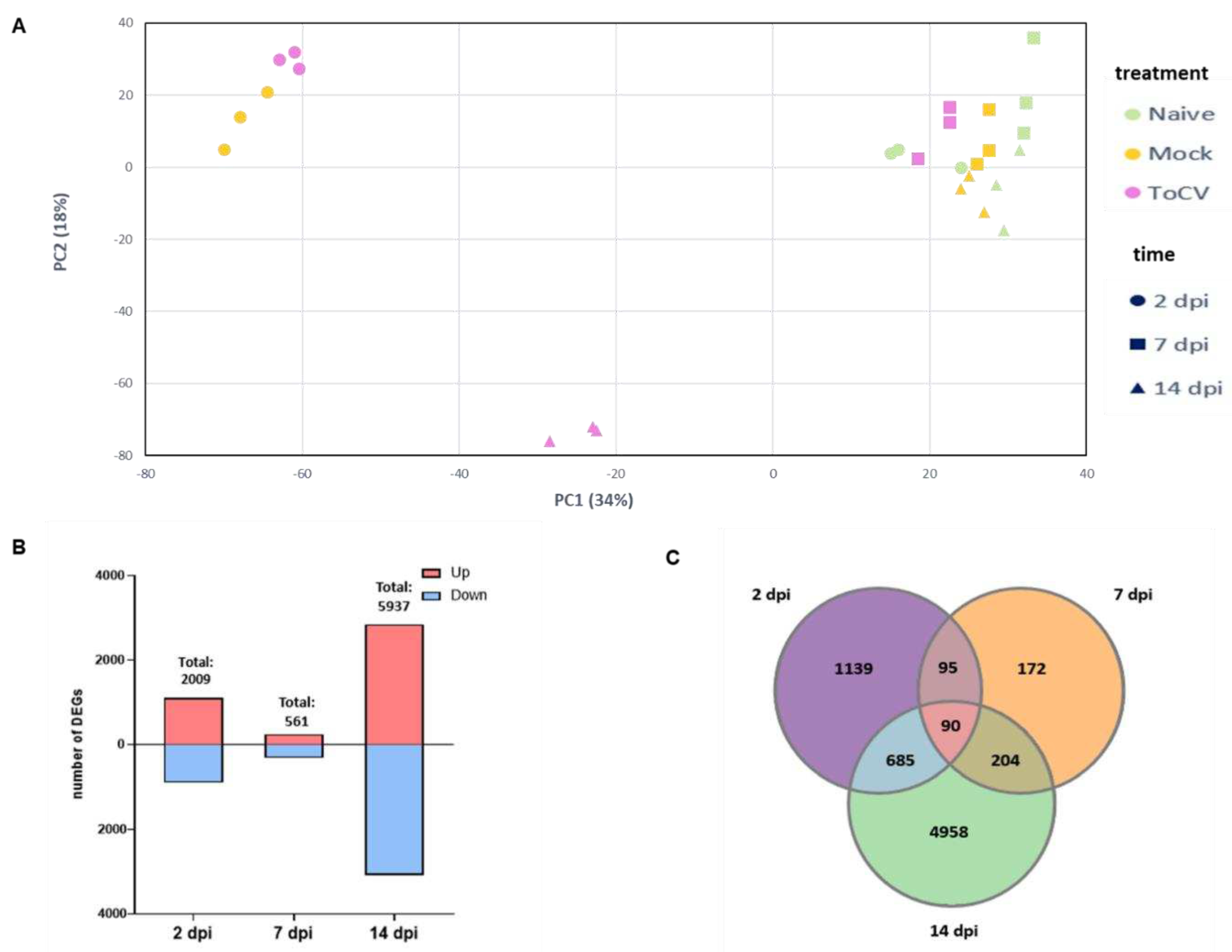

3.1. Identification of DEGs in tomato leaves at different stages of ToCV infection

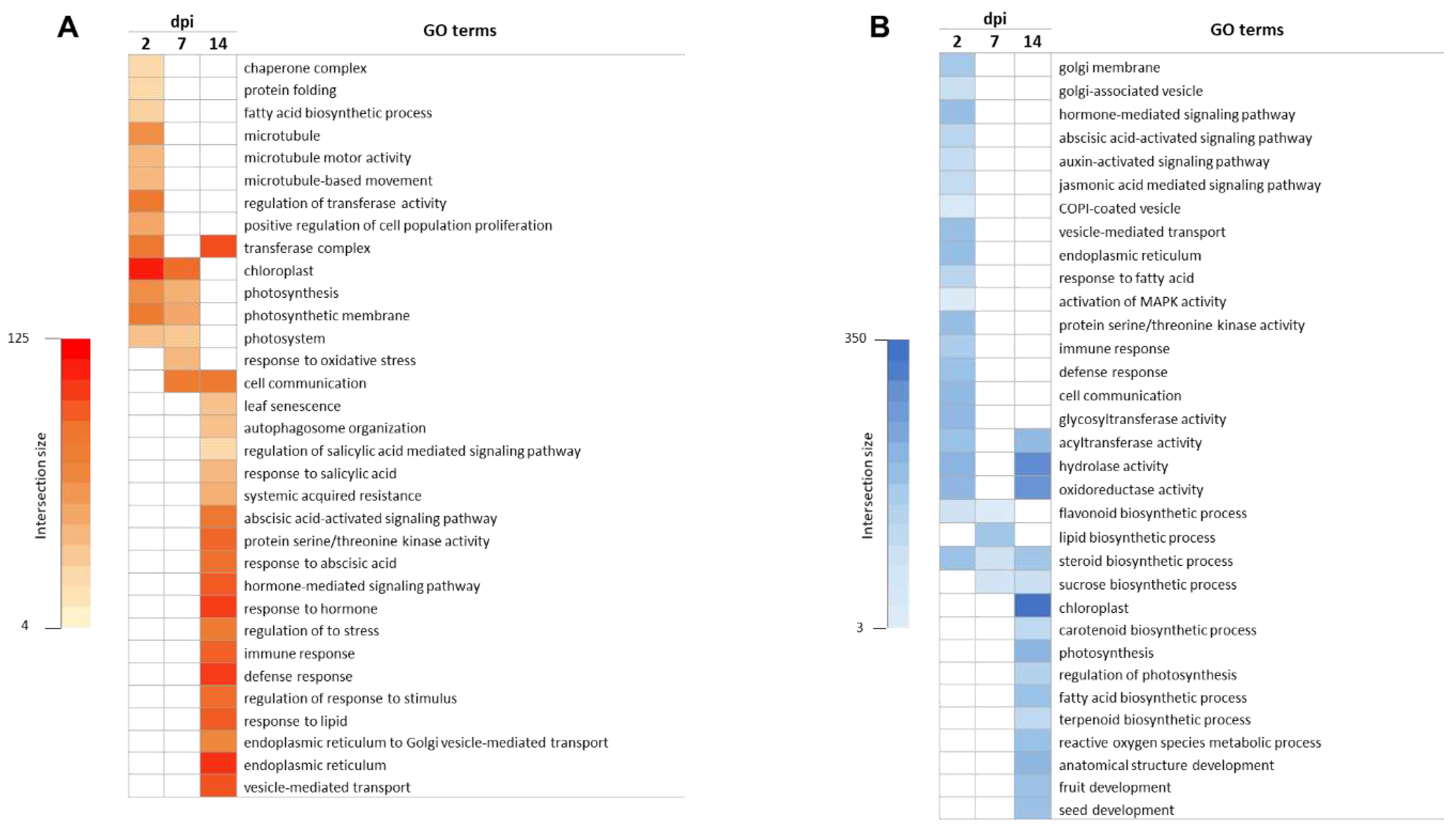

3.2. Gene ontology enrichment analysis in response to ToCV

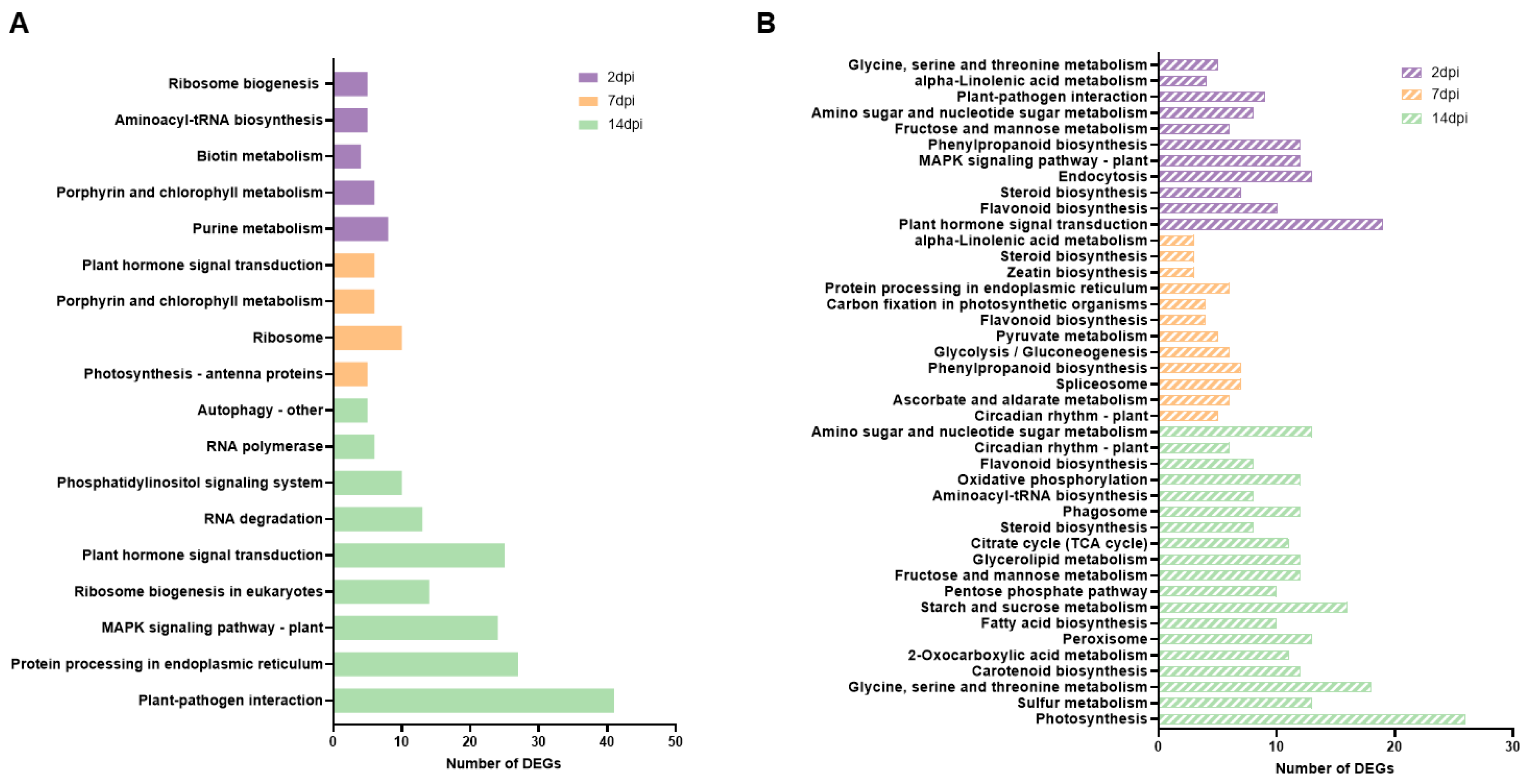

3.3. Impacted pathways in ToCV infection

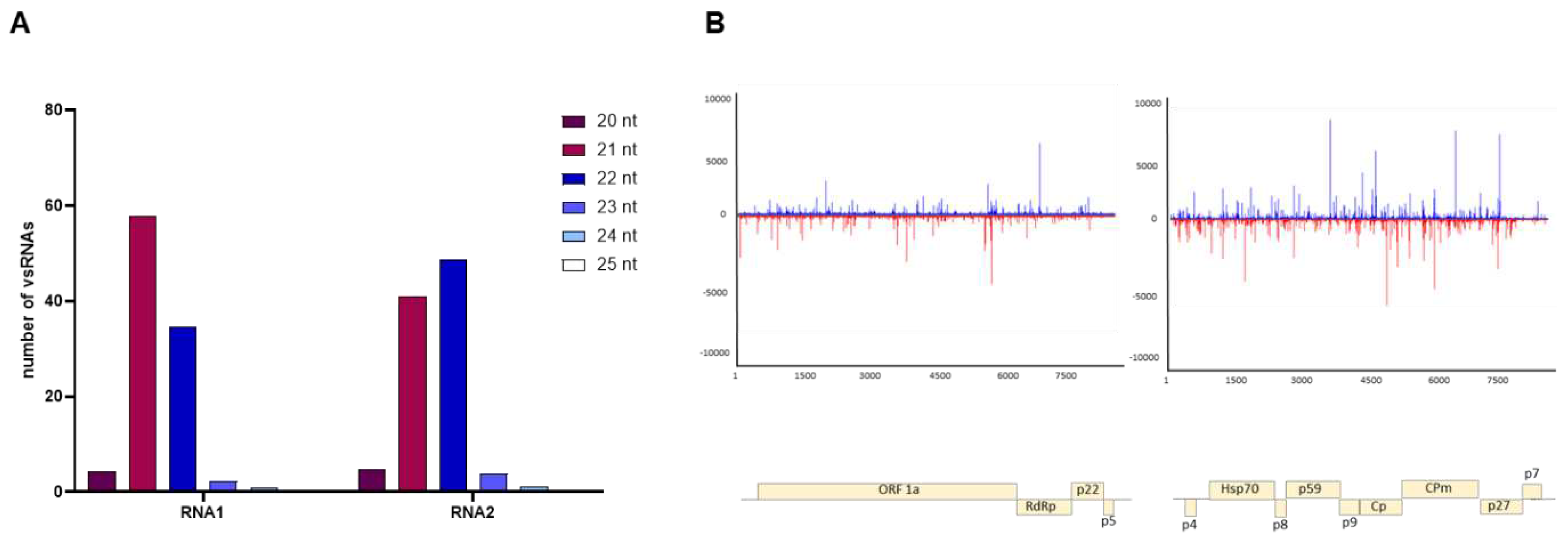

3.4. Characterizing viral small RNAs in ToCV-infected plants

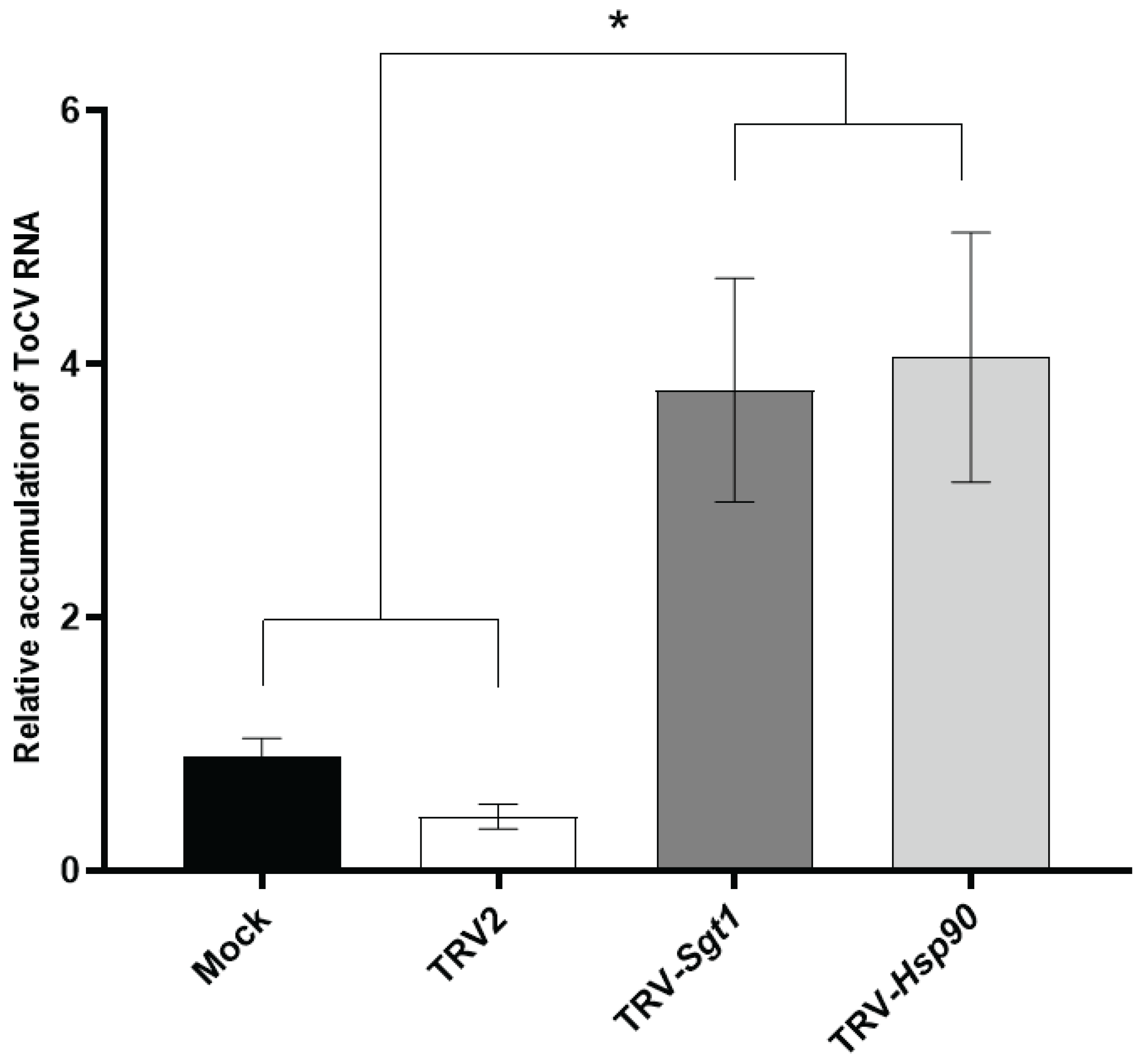

3.5. Enhanced ToCV susceptibility in tomato plants after silencing of Hsp90 and Sgt1 genes

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fiallo-Olivé, E.; Navas-Castillo, J. Tomato Chlorosis Virus, an Emergent Plant Virus Still Expanding Its Geographical and Host Ranges. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2019, 20, 1307–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wintermantel, W.M.; Wisler, G.C.; Anchieta, A.G.; Liu, H.-Y.; Karasev, A.V.; Tzanetakis, I.E. The Complete Nucleotide Sequence and Genome Organization of Tomato Chlorosis Virus. Arch. Virol. 2005, 150, 2287–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortes, I.M.; Fernández-Muñoz, R.; Moriones, E. The Crinivirus Tomato Chlorosis Virus Compromises the Control of Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus in Tomato Plants by the Ty-1 Gene. Phytopathology® 2023, PHYTO-09-22-0334-R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Ding, T.; Chu, D. Synergistic Effects of a Tomato Chlorosis Virus and Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus Mixed Infection on Host Tomato Plants and the Whitefly Vector. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 672400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, A.B.; López-Moya, J.J. When Viruses Play Team Sports: Mixed Infections in Plants. Phytopathology® 2020, 110, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ontiveros, I.; López-Moya, J.J.; Díaz-Pendón, J.A. Coinfection of Tomato Plants with Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus and Tomato Chlorosis Virus Affects the Interaction with Host and Whiteflies. Phytopathology® 2022, 112, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.S.; Citovsky, V. Plant Viruses. Invaders of Cells and Pirates of Cellular Pathways. Plant Physiol. 2005, 138, 1809–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyer, A.; Hamlin, L.; Crosslin, J.M.; Buchanan, A.; Chang, J.H. RNA-Seq Analysis of Resistant and Susceptible Potato Varieties during the Early Stages of Potato Virus Y Infection. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Cui, H.; Cui, X.; Wang, A. The Altered Photosynthetic Machinery during Compatible Virus Infection. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2016, 17, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Du, Z.-X.; Kong, J.; Chen, L.-N.; Qiu, Y.-H.; Li, G.-F.; Meng, X.-H.; Zhu, S.-F. Transcriptome Analysis of Nicotiana Tabacum Infected by Cucumber Mosaic Virus during Systemic Symptom Development. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Ding, X.; Fu, X.; Lozano-Duran, R. Transcriptional Reprogramming Caused by the Geminivirus Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus in Local or Systemic Infections in Nicotiana Benthamiana. BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Shen, D.; Sun, P.; Xu, Y.; Tao, X. Dynamic Transcriptional Profiles of Arabidopsis Thaliana Infected by Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus. Phytopathology® 2020, 110, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, M. Next-Generation Sequencing Technologies for Gene Expression Profiling in Plants. Brief. Funct. Genomics 2012, 11, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Gerstein, M.; Snyder, M. RNA-Seq: A Revolutionary Tool for Transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanardo, L.G.; De Souza, G.B.; Alves, M.S. Transcriptomics of Plant–Virus Interactions: A Review. Theor. Exp. Plant Physiol. 2019, 31, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.-K.; Kim, M.-K.; Kwak, H.-R.; Choi, H.-S.; Nam, M.; Choe, J.; Choi, B.; Han, S.-J.; Kang, J.-H.; Jung, C. Molecular Dissection of Distinct Symptoms Induced by Tomato Chlorosis Virus and Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus Based on Comparative Transcriptome Analysis. Virology 2018, 516, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, H.; Huang, L.-P.; Lu, D.-Y.-H.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, D.-Y.; Zheng, L.-M.; Gao, Y.; Tan, X.-Q.; Zhou, X.-G.; et al. Integrated Analysis of microRNA and mRNA Transcriptome Reveals the Molecular Mechanism of Solanum Lycopersicum Response to Bemisia Tabaci and Tomato Chlorosis Virus. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 693574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuper, H.; Amari, K.; Krenz, B. Analyzing the G3BP-like Gene Family of Arabidopsis Thaliana in Early Turnip Mosaic Virus Infection. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thivierge, K.; Nicaise, V.; Dufresne, P.J.; Cotton, S.; Laliberté, J.-F.; Le Gall, O.; Fortin, M.G. Plant Virus RNAs. Coordinated Recruitment of Conserved Host Functions by (+) ssRNA Viruses during Early Infection Events. Plant Physiol. 2005, 138, 1822–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baulcombe, D. RNA Silencing in Plants. Nature 2004, 431, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.-W. RNA-Based Antiviral Immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.-W. Transgene Silencing, RNA Interference, and the Antiviral Defense Mechanism Directed by Small Interfering RNAs. Phytopathology® 2023, 113, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llave, C. Virus-Derived Small Interfering RNAs at the Core of Plant–Virus Interactions. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deleris, A.; Gallego-Bartolome, J.; Bao, J.; Kasschau, K.D.; Carrington, J.C.; Voinnet, O. Hierarchical Action and Inhibition of Plant Dicer-Like Proteins in Antiviral Defense. Science 2006, 313, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Pendon, J.A.; Li, F.; Li, W.-X.; Ding, S.-W. Suppression of Antiviral Silencing by Cucumber Mosaic Virus 2b Protein in Arabidopsis Is Associated with Drastically Reduced Accumulation of Three Classes of Viral Small Interfering RNAs. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 2053–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaire, L.; Barajas, D.; Martínez-García, B.; Martínez-Priego, L.; Pagán, I.; Llave, C. Structural and Genetic Requirements for the Biogenesis of Tobacco Rattle Virus -Derived Small Interfering RNAs. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 5167–5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Gomollon, S.; Baulcombe, D.C. Roles of RNA Silencing in Viral and Non-Viral Plant Immunity and in the Crosstalk between Disease Resistance Systems. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwakawa, H.; Lam, A.Y.W.; Mine, A.; Fujita, T.; Kiyokawa, K.; Yoshikawa, M.; Takeda, A.; Iwasaki, S.; Tomari, Y. Ribosome Stalling Caused by the Argonaute-microRNA-SGS3 Complex Regulates the Production of Secondary siRNAs in Plants. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Li, B.; Iwakawa, H.; Pan, Y.; Tang, X.; Ling-hu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Sheng, S.; Feng, L.; Zhang, H.; et al. Plant 22-Nt siRNAs Mediate Translational Repression and Stress Adaptation. Nature 2020, 581, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaire, L.; Wang, Y.; Gonzalez-Ibeas, D.; Mayer, K.F.; Aranda, M.A.; Llave, C. Deep-Sequencing of Plant Viral Small RNAs Reveals Effective and Widespread Targeting of Viral Genomes. Virology 2009, 392, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvira González, L.; Peiró, R.; Rubio, L.; Galipienso, L. Persistent Southern Tomato Virus (STV) Interacts with Cucumber Mosaic and/or Pepino Mosaic Virus in Mixed- Infections Modifying Plant Symptoms, Viral Titer and Small RNA Accumulation. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Ibeas, D.; Blanca, J.; Donaire, L.; Saladié, M.; Mascarell-Creus, A.; Cano-Delgado, A.; Garcia-Mas, J.; Llave, C.; Aranda, M.A. Analysis of the Melon (Cucumis Melo) Small RNAome by High-Throughput Pyrosequencing. BMC Genomics 2011, 12, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavalappara, S.R.; Bag, S.; Luckew, A.; McGregor, C.E. Small RNA Profiling of Cucurbit Yellow Stunting Disorder Virus from Susceptible and Tolerant Squash (Cucurbita Pepo) Lines. Viruses 2023, 15, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaya, C.; Fletcher, S.J.; Zhai, Y.; Peters, J.; Margaria, P.; Winter, S.; Mitter, N.; Pappu, H.R. The Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus (TSWV) Genome Is Differentially Targeted in TSWV-Infected Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum) with or without Sw-5 Gene. Viruses 2020, 12, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Sun, X.; Taylor, A.; Jiao, C.; Xu, Y.; Cai, X.; Wang, X.; Ge, C.; Pan, G.; Wang, Q.; et al. Diversity, Distribution, and Evolution of Tomato Viruses in China Uncovered by Small RNA Sequencing. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e00173-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piedra-Aguilera, Á.; Jiao, C.; Luna, A.P.; Villanueva, F.; Dabad, M.; Esteve-Codina, A.; Díaz-Pendón, J.A.; Fei, Z.; Bejarano, E.R.; Castillo, A.G. Integrated Single-Base Resolution Maps of Transcriptome, sRNAome and Methylome of Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus (TYLCV) in Tomato. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Cano, E.; Resende, R.O.; Fernández-Muñoz, R.; Moriones, E. Synergistic Interaction Between Tomato Chlorosis Virus and Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus Results in Breakdown of Resistance in Tomato. Phytopathology® 2006, 96, 1263–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortes, I.M.; Moriones, E.; Navas-Castillo, J. Tomato Chlorosis Virus in Pepper: Prevalence in Commercial Crops in Southeastern Spain and Symptomatology under Experimental Conditions: Tomato Chlorosis Virus in Pepper. Plant Pathol. 2012, 61, 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewels, P.; Magnusson, M.; Lundin, S.; Käller, M. MultiQC: Summarize Analysis Results for Multiple Tools and Samples in a Single Report. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3047–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Pozo, N.; Menda, N.; Edwards, J.D.; Saha, S.; Tecle, I.Y.; Strickler, S.R.; Bombarely, A.; Fisher-York, T.; Pujar, A.; Foerster, H.; et al. The Sol Genomics Network (SGN)—from Genotype to Phenotype to Breeding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D1036–D1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A Fast Spliced Aligner with Low Memory Requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R. 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup The Sequence Alignment/Map Format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.-C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie Enables Improved Reconstruction of a Transcriptome from RNA-Seq Reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raudvere, U.; Kolberg, L.; Kuzmin, I.; Arak, T.; Adler, P.; Peterson, H.; Vilo, J. G:Profiler: A Web Server for Functional Enrichment Analysis and Conversions of Gene Lists (2019 Update). Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W191–W198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and Accurate Short Read Alignment with Burrows–Wheeler Transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seguin, J.; Otten, P.; Baerlocher, L.; Farinelli, L.; Pooggin, M.M. MISIS-2: A Bioinformatics Tool for in-Depth Analysis of Small RNAs and Representation of Consensus Master Genome in Viral Quasispecies. J. Virol. Methods 2016, 233, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Schiff, M.; Marathe, R.; Dinesh-Kumar, S.P. Tobacco Rar1, EDS1 and NPR1/NIM1 like Genes Are Required for N-Mediated Resistance to Tobacco Mosaic Virus. Plant J. 2002, 30, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Sánchez, L.; Planelló, R.; Ferrero, V.; Fernández-Muñoz, R.; De La Peña, E.; Díaz Pendón, J.A. More than Trichomes and Acylsugars: The Role of Jasmonic Acid as Mediator of Aphid Resistance in Tomato. J. Plant Interact. 2023, 18, 2255597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expósito-Rodríguez, M.; Borges, A.A.; Borges-Pérez, A.; Pérez, J.A. Selection of Internal Control Genes for Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR Studies during Tomato Development Process. BMC Plant Biol. 2008, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenberg, D.; Thompson, T.S.; German, T.L.; Willis, D.K. Methods for Effective Real-Time RT-PCR Analysis of Virus-Induced Gene Silencing. J. Virol. Methods 2006, 138, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaroson, M.-L.; Koutouan, C.; Helesbeux, J.-J.; Le Clerc, V.; Hamama, L.; Geoffriau, E.; Briard, M. Role of Phenylpropanoids and Flavonoids in Plant Resistance to Pests and Diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 8371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Peng, Z.; Tong, H.; Yang, F.; Xing, G.; Wang, L.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Su, Q. Tomato Plant Flavonoids Increase Whitefly Resistance and Reduce Spread of Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus. J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, toz199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhary, S.P.; Yu, J.-Q.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K.; Tran, L.-S.P. Benefits of Brassinosteroid Crosstalk. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 594–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Qian, H.; Shen, W.; Liu, L.; Zhang, M.; Cai, C.; Zhao, Y.; Qiao, J.; Wang, Q. BZR1 and BES1 Participate in Regulation of Glucosinolate Biosynthesis by Brassinosteroids in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 2401–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyaji, T.; Yamagami, A.; Kume, N.; Sakuta, M.; Osada, H.; Asami, T.; Arimoto, Y.; Nakano, T. Brassinosteroid-Related Transcription Factor BIL1/BZR1 Increases Plant Resistance to Insect Feeding. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2014, 78, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Einig, E.; Almeida-Trapp, M.; Albert, M.; Fliegmann, J.; Mithöfer, A.; Kalbacher, H.; Felix, G. The Systemin Receptor SYR1 Enhances Resistance of Tomato against Herbivorous Insects. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.-H.; Hettenhausen, C.; Baldwin, I.T.; Wu, J. BAK1 Regulates the Accumulation of Jasmonic Acid and the Levels of Trypsin Proteinase Inhibitors in Nicotiana Attenuata’s Responses to Herbivory. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kørner, C.J.; Klauser, D.; Niehl, A.; Domínguez-Ferreras, A.; Chinchilla, D.; Boller, T.; Heinlein, M.; Hann, D.R. The Immunity Regulator BAK1 Contributes to Resistance Against Diverse RNA Viruses. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interactions® 2013, 26, 1271–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Durán, R.; Zipfel, C. Trade-off between Growth and Immunity: Role of Brassinosteroids. Trends Plant Sci. 2015, 20, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.-H.; Zhao, Z.-Z.; He, J.-X. Brassinosteroid Signaling in Plant–Microbe Interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcaide, C.; Donaire, L.; Aranda, M.A. Transcriptome Analyses Unveiled Differential Regulation of AGO and DCL Genes by Pepino Mosaic Virus Strains. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 23, 1592–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasgupta, U.; Mishra, G.P.; Dikshit, H.K.; Mishra, D.C.; Bosamia, T.; Roy, A.; Bhati, J.; Priti; Aski, M.; Kumar, R.R.; et al. Comparative RNA-Seq Analysis Unfolds a Complex Regulatory Network Imparting Yellow Mosaic Disease Resistance in Mungbean [Vigna Radiata (L.) R. Wilczek]. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0244593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Cheng, Y.; Gong, M.; Zhao, Q.; Jiang, C.; Cheng, L.; Ren, M.; Wang, Y.; Yang, A. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Differential Gene Expression in Resistant and Susceptible Tobacco Cultivars in Response to Infection by Cucumber Mosaic Virus. Crop J. 2019, 7, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, A.; Gargani, D.; Macia, J.-L.; Malouvet, E.; Vernerey, M.-S.; Blanc, S.; Drucker, M. Virus Factories of Cauliflower Mosaic Virus Are Virion Reservoirs That Engage Actively in Vector Transmission. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 12207–12215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niehl, A.; Peña, E.J.; Amari, K.; Heinlein, M. Microtubules in Viral Replication and Transport. Plant J. 2013, 75, 290–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Xiao, K.; Pan, H.; Liu, J. Chloroplast: The Emerging Battlefield in Plant–Microbe Interactions. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 637853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Hong, Y.; Liu, Y. Chloroplast in Plant-Virus Interaction. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salguero-Linares, J.; Coll, N.S. Cell Death as a Defense Strategy against Pathogens in Plants and Animals. PLOS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Liu, Y. Autophagy in Plant Viral Infection. FEBS Lett. 2022, 596, 2152–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.D.G.; Dangl, J.L. The Plant Immune System. Nature 2006, 444, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miozzi, L.; Napoli, C.; Sardo, L.; Accotto, G.P. Transcriptomics of the Interaction between the Monopartite Phloem-Limited Geminivirus Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Sardinia Virus and Solanum Lycopersicum Highlights a Role for Plant Hormones, Autophagy and Plant Immune System Fine Tuning during Infection. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Pendon, J.A.; Ding, S.-W. Direct and Indirect Roles of Viral Suppressors of RNA Silencing in Pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2008, 46, 303–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cañizares, M.C.; Navas-Castillo, J.; Moriones, E. Multiple Suppressors of RNA Silencing Encoded by Both Genomic RNAs of the Crinivirus, Tomato Chlorosis Virus. Virology 2008, 379, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, S.; Xu, F.; Li, T.; Fu, D.; et al. Tomato DCL2b Is Required for the Biosynthesis of 22-Nt Small RNAs, the Resulting Secondary siRNAs, and the Host Defense against ToMV. Hortic. Res. 2018, 5, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirasu, K. The HSP90-SGT1 Chaperone Complex for NLR Immune Sensors. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2009, 60, 139–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshe, A.; Gorovits, R.; Liu, Y.; Czosnek, H. Tomato Plant Cell Death Induced by Inhibition of HSP90 Is Alleviated by Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus Infection: Cell Death Reduction in Virus-Infected Plants. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016, 17, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).