1. Introduction

Magnesium oxysulfate (MOS) cement is an alternative binder prepared through the reaction between magnesium oxide (MgO) and aqueous solution of magnesium sulfate (MgSO

4) [

1,

2,

3]. It offers several advantages, including good fire resistance, lightweight properties, low alkalinity, and low energy consumption, with its primay application being in the production of lightweight panels [

4,

5,

6]. In general, four oxysulfate phases are found at temperatures between 30 and 120 °C. I) 3Mg(OH)

2-MgSO

4-8H

2O (3-1-8 phase), II) 5Mg(OH)

2-MgSO

4-3H

2O (5-1-3 or 5-1-2 phase), III) Mg(OH)

2-MgSO

4-5H

2O (1-1-5 phase) and IV) Mg(OH)

2-2MgSO

4-3H

2O (1-2-3 phase) [

7].

Despite inconclusive predictions regarding the forthcoming impacts of climate change, a direct relationship exists between the global temperature rise and the heightened concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Of particular concern is the emission of carbon dioxide (CO

2) resulting from the combustion of fossil fuels, due to the greenhouse effect of this gas [

8]. An important source of CO

2 emissions is the production of ordinary Portland cement (OPC) [

9,

10]. OPC is the most commonly used cement in the construction industry and the manufacturing process involves high CO

2 emissions, primarly from the decomposition of carbonates, such as limestone, and the burning of coal at high temperatures, around 1500 °C [

11]. It has been reported that the emissions generated in cement production consist of 5 to 7% of total global CO

2 emissions [

12,

13], making it necessary to develop alternative cementitious materials to replace those conventionally used.

The production of magnesium oxide mainly comes from the calcination of magnesite (MgCO

3), and to a lesser degree from seawater and brine [

14]. In general, MgO is categorized into different grades [

15]: light-burned MgO (LBM) or caustic-calcined (calcined at 700-1000 °C), wich has the highest reactivity and specific surface area; hard-burned (calcined at 1000-1500 °C), with lower reactivity and specific surface area compared to LBM; dead-burned or periclase (calcined at 1400-2000 °C), with the lowest specific surface area, making them almost non-reactive; and fused magnesia (calcined at T>2800 °C) with the lowest reactivity [

3,

16].

Light-burned MgO is the main type of MgO used in the production of MOS cements due to the high reactivity of this magnesia type [

17]. In the case of building materials based on MOS cement with a porous structure, the MgO undergoes carbonation reactions under appropriate curing conditions by absorbing carbon dioxide resulting in a significant improvement in mechanical strength. Additionally, the composition can have a high proportion of cellulose fibers, such as eucalyptus fibers, leading to lower total CO

2 emissions when compared to OPC based building materials.

MgO carbonation can generally be described as the formation of magnesite from MgO by absorbing CO

2 (MgO+CO

2→MgCO

3) or by incorporating H

2O to form needle-like nesquehonite (MgCO

3·3H

2O), acicular artinite (MgCO

3·Mg(OH)

2·3H

2O) and disk-like hydro-magnesite (4MgCO

3·Mg(OH)

2·4H

2O) [

18]; The hydrates formed, depending on the curing conditions, lead to a gain in mechanical strength due to their inherent resistance and their capacity to bind aggregate particles [

14].

Sun Qi et al. [

19] found that carbonation can not only improve the toughness of MOS cement to some extent, but also further reduce the porosity. BA et al. [

4] demonstrated a decrease in the alkalinity and porosity of MOS cement. These findings hold the potential to enhance the durability of cellulose fibers within this type of matrix. According to Qiyan Li et al. [

20], incorporating CO

2 capture during cement curing significantly enhances resistance to wetting-drying cycles. The results suggest that carbon dioxide neutralizes magnesium hydroxide and some basic phases of magnesium oxysulfate within MOS cement, resulting in the formation of magnesium carbonate phases, thereby refining pore structures and increasing overall strength.

There are some studies about the influence of rehydration on the properties of OPC materials [

22,

23]. However, the effect of the rehydration on the carbonation of MOS cement still remains relatively unexplored. In this work, the influence of rehydration method applied to magnesium oxysulfate cement boards before carbonation curing was analyzed. The physical-mechanical performance and microstructural characteristics of MOS boards before and after carbonation were investigated through water absorption (WA), apparent porosity (AP) and bulk density (BD); four-point bending test; X-ray diffraction (XRD); thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The MOS based fiber-cement boards were produced with a mixture of magnesium oxide powder (MgO), magnesium sulphate heptahydrate (MgSO4.7H2O), dolomitic limestone, citric acid and reinforced with unbleached eucalyptus cellulose fiber.

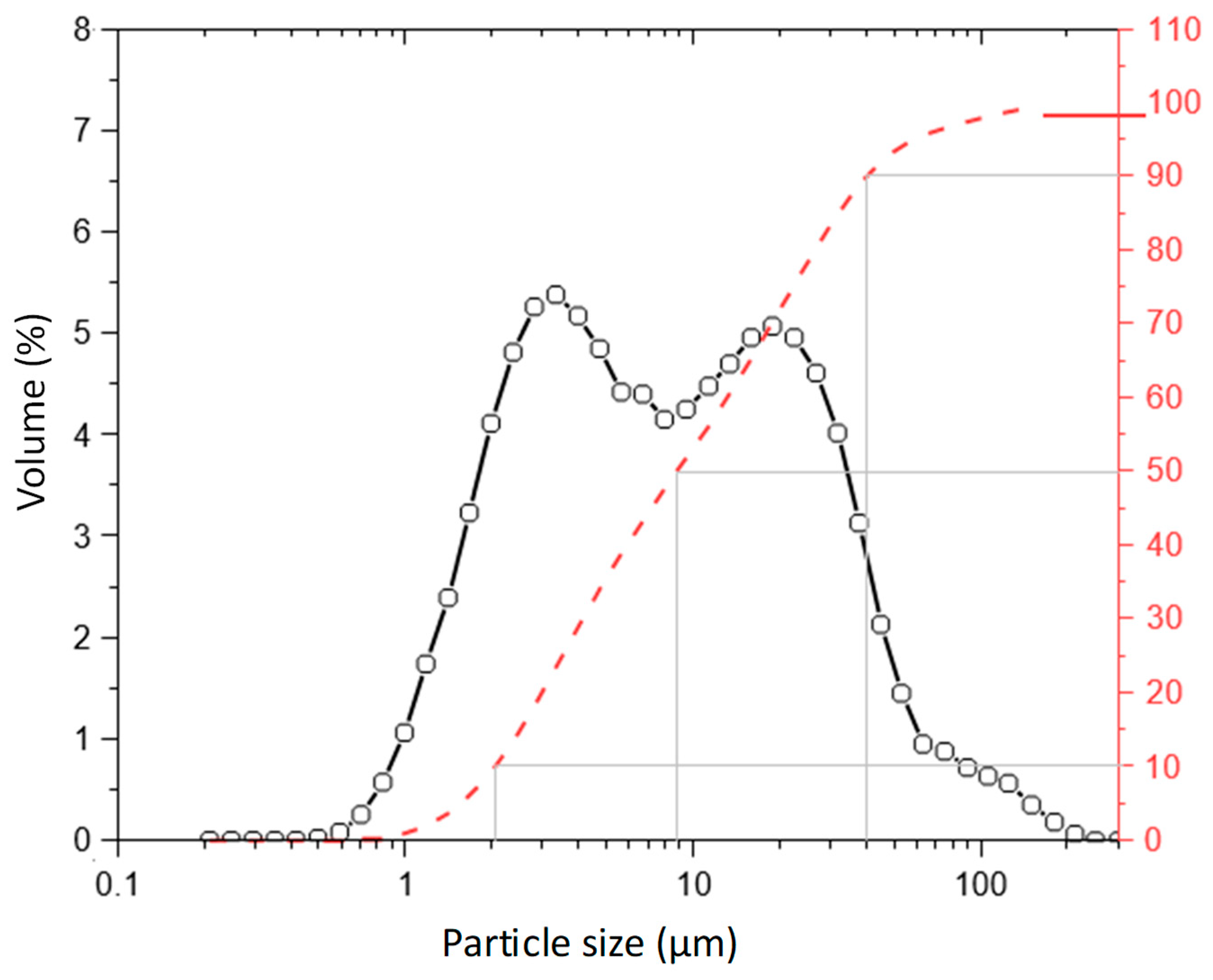

MgO, obtained by controlled calcination of magnesite (1050 °C), was purchased from RHI-Magnesita S.A., Brumado, Bahia State, Brazil. It has a specific gravity of 3.45 g/cm³ and surface area of 26.71 m²/g (SSA). As observes in

Figure 1, the particle size of MgO presents values of D10, D50 and D90 close to 2.1, 8.8 and 40.0 μm, respectively.

Magnesium sulfate heptahydrate (commercial-grade Epsom salt, MgSO

4.7H

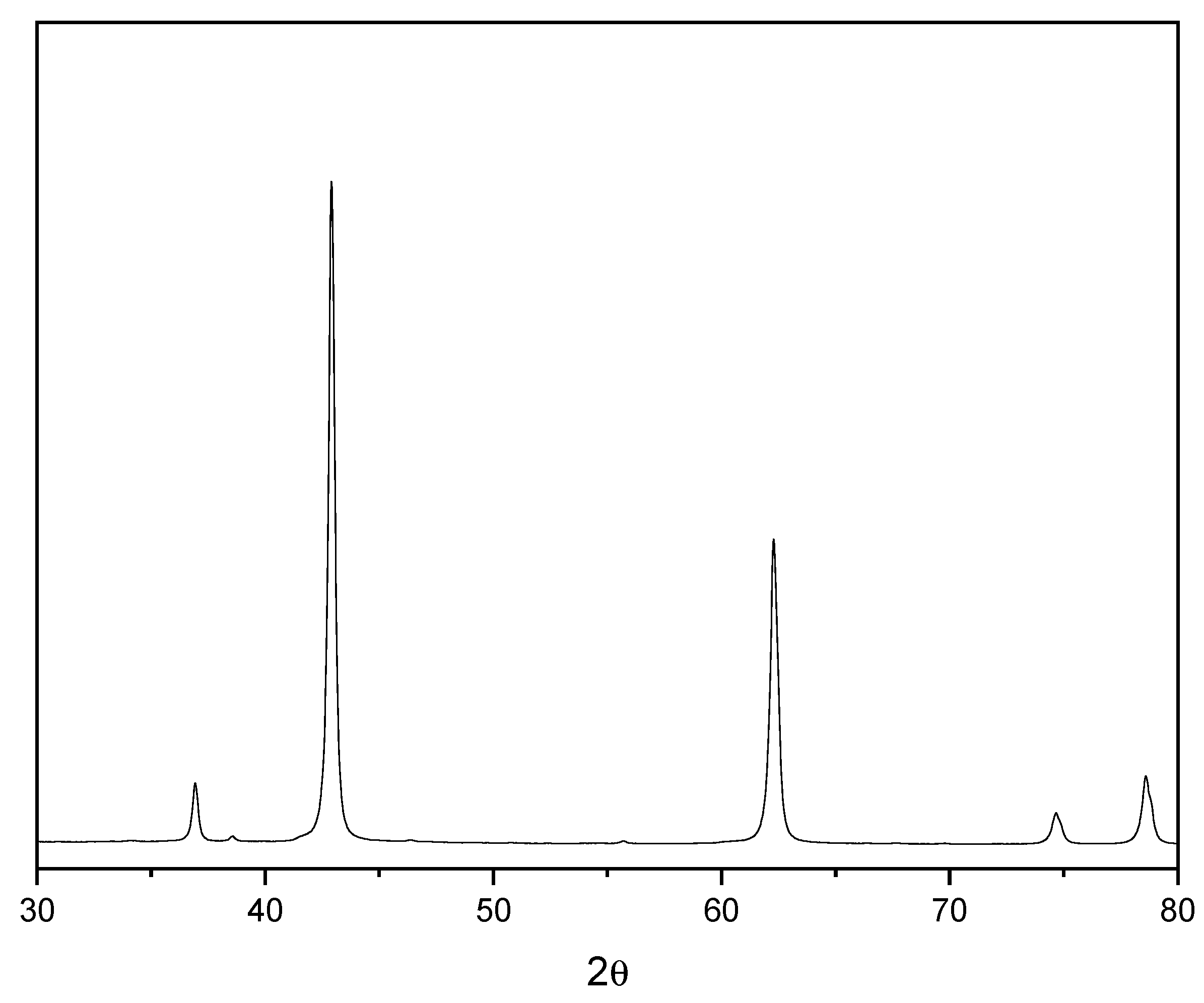

2O) was produced with a purity of 99,83%. The chemical composition, as well the X-ray diffractogram pattern of the MgO used, is presented in

Table 1 and

Figure 2, respectively. In

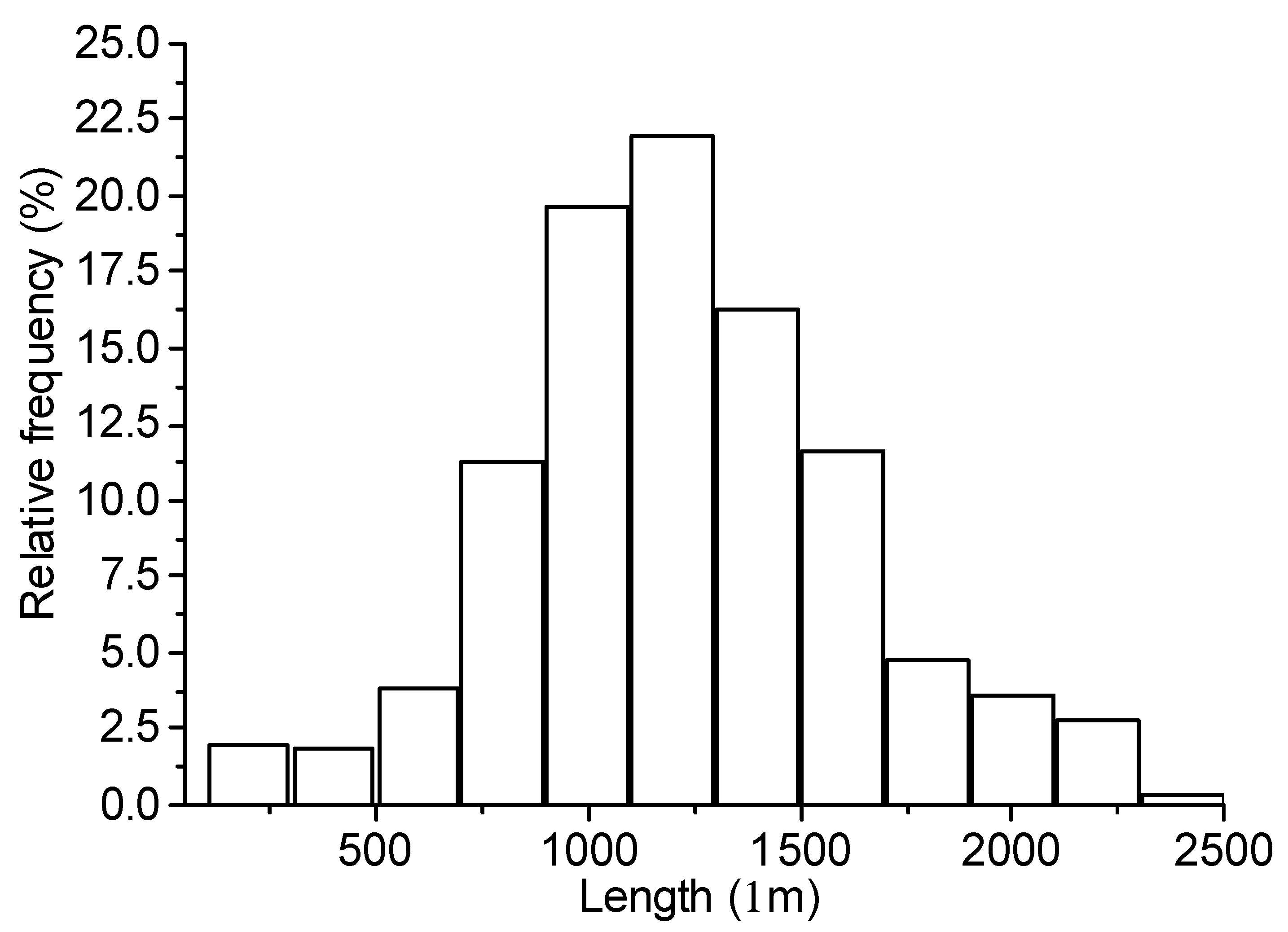

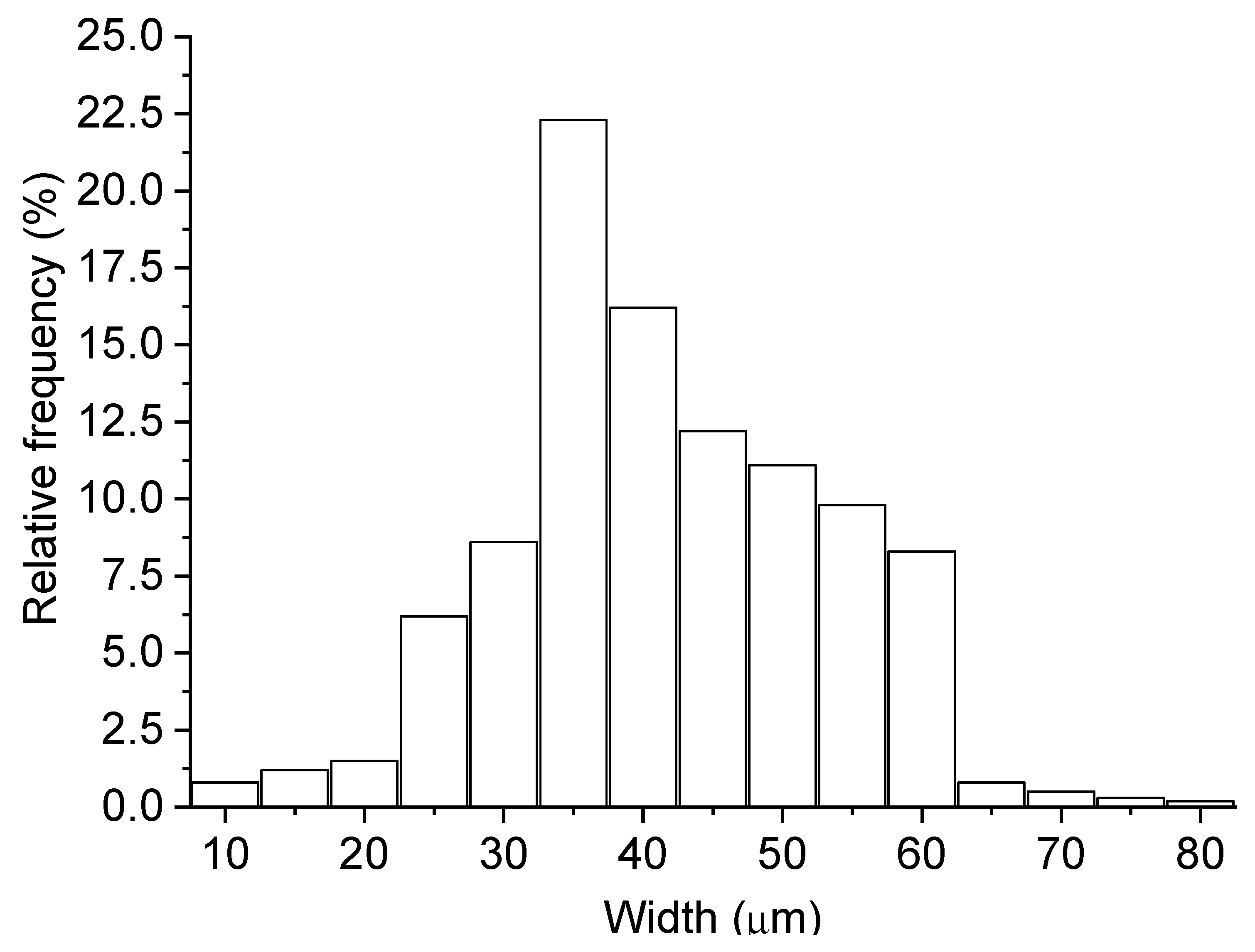

Figure 2, it is possible to identify different diffraction peaks related to periclase (MgO), with the peak close to 42° 2Ɵ having the highest intensity, as shown in ICDD Nº 00-0004-0829. The chemical composition of MgO shows a high concentration of MgO, as suggested by the manufacturer. In contrast, the dolomitic limestone has a high content of CaO in its composition and exhibited a loss on ignition of approximately 40%, which was attributed to the presence of carbonates in the material. The dolomite limestone used as a filler in the fiber cement boards has a density of 2.79 g/cm³. Citric acid of analytical purity was used in the mixture in a proportion of 0.50% in relation to the mass of MgO. Unbleached Eucalyptus pulp was used as lignocellulosic reinforcement in the fiber-cement boards produced. The fiber was process in water (kept in water immersion for 48h) and then disintegrated using a cellulosic pulp mixer, Tedemix MRF31450. The morphological characterization (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) was carried out using an adapted TAPPI T271 Standard. The chemical composition of cellulosic pulp was determined using the procedure reported by Van Soest [

21]. The authors analyzed the vegetable fibers components, considering the chemical compounds present in the cell (lipids, fats, etc.) and cell wall (cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin and insoluble protein). The chemical composition of unbleached Eucalyptus pulp is presented in

Table 2.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Sample preparation

The fiber-cement boards were obtained through an adapted industrial Hatschek process. The cellulose pulp was initially dispersed in a mixture of distilled water, MgSO4 solution with a concentration of 25% and 0.50% of citric acid, at 3000 rpm for 5 min. Subsequently, MgO, in a MgO:MgSO4 molar ratio of 10, and dolomitic limestone, constituting 20% of the amount of MgO by mass (previously homogenized), were added, and the mixture was stirred for another 3 minutes. The paste was then transferred to a perforated mould, and a vacuum pressure was applied. Following that, the boards were compacted with a pressure of 3.2 MPa for 5 min.

2.2.2. Accelerated carbonation process

To evaluate the effect of carbonation at early ages of curing, the samples were kept in a hermetically sealed environment before being cured in a CO

2-rich atmosphere. All samples were exposed to a concentrated CO

2 environment of 20% CO

2 and 40% relative humidity (RH) at 60 °C for 6 hours to accelerate the carbonation process. The boards were carbonated after 24, 48 and 72 hours of production and were named Carb24, Carb48, and Carb72, respectively. The samples cured without the carbonation process were named Ref. A climatic chamber with control of temperature, humidity and CO

2 concentration, of the Espec brand, model EPL-4H, was used. The different samples produced by accelerated carbonation are presented in

Table 3.

In preparation for subsequent carbonation, fiber cement boards underwent an essential rehydration stage through water immersion. This preliminary step aimed to reinstate moisture and create optimal conditions for effective carbonation. According to

Table 3, the boards Carb24-RE, Carb48-RE and Carb72-RE were submerged in water for a timed period of 5 minutes to ensured thorough hydration, followed by draining excess water. This process created an ideal environment for the subsequent carbonation phase. The rehydrated boards transitioned into the carbonation process, highlighting the efficacy of this pre-immersion hydration technique in optimizing the final properties of the fiber-cement boards.

2.2.3. Characterization of samples

The physical, mechanical, and microstructural characterization of the boards was performed 7 days after molding. The test specimens were cut to dimensions of 160x40x5 mm. A total of eight test specimens were utilized for the mechanical and physical analyses of the materials produced under varying conditions.

ASTM-C948-81 [

24] was used to determine the physical properties. Water absorption (WA), apparent porosity (AP), and bulk density (BD) were the parameters that were examined.

A four-point bending test [

25] was performed on the boards to evaluate their mechanical properties. The test was conducted using an EMIC DL30000 universal mechanical testing machine equipped with 5 kN loadcell and a deflectometer to detect the displacement in the center of the sample. A distance of 135 mm was used between the bottom supports, and 45 mm between the top supports, along with a load speed of 5 mm/min, were used. The deflection during the bending test was collected by the deflectometer positioned in the middle span, on the underside of the specimen. The deflectometer used was an EMIC brand with a maximum deformation of 30 mm and an accuracy of 0.0001 mm. The modulus of rupture (MOR), limit of proportionality (LOP), modulus of elasticity (MOE), and specific energy (SE) were determined using the methodology employed by Savastano Junior et al. (2000) [

22].

To identify phase evolution, X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were performed on samples extracted before and after each different carbonation condition. X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) patterns of the fiber cement boards were collected using a Horiba LA-60 diffractometer using CuKα radiation generated at a voltage of 40 kV and a tube current of 30 mA, with scan angles ranging from 10-70° at a rate of 2°/min. The morphological analyses were performed using a Philips XL-30 FEG (Field Emission Gun) microscope.

Samples were prepared following the same procedure used in X-ray diffraction. Thermogravimetry (TGA) was utilized to measure the changes in mass within the fiber cement samples with respect to temperature. The objective of the TGA analysis was to evaluate the constituents generated during the MOS cement production and assess the carbonation in the formation of new products. The analysis was conducted using a TA Instruments SDT 600 model, with a heating rate of 10 °C/min, reaching 1000 °C, and a nitrogen flow rate of 40 mL/min.

3. Results

3.1. Mechanical Properties

Table 4 presents the results of flexural tests conducted on carbonated cementitious composites under varying conditions and the reference samples. It is evident that the accelerated carbonation process applied to the composites induced alterations in the mechanical properties of the boards. The carbonation process, without prior rehydration, notably enhanced the properties of samples cured for 48 hours. Carb48 boards exhibited an average increase in MOR values of approximately 14.7%, 25.34%, and 32.4% when compared to the Ref, Carb24, and Carb72 samples, respectively.

The carbonation process is responsible for the generation of new carbonate products. These reactions occur between the CO

2 present in the carbonation chamber and the alkali species within the cementitious matrix used as the base in composite production. As described by Meng et al. (2023) [

23], the reactions associated with the formation of carbonates in MgO-based cement matrices are presented in equations 1, 2, and 3.

According to

Table 4, the formation of carbonates preferentially occurs in the voids and pores within the cementitious matrix, which is associated with increased material stiffness and, consequently, the average MOE values of the composites. The changes in mechanical properties observed in boards cured for different periods may be linked to the formation of alkali species that are consumed during carbonation in a CO

2-rich atmosphere. The longer pre-carbonation curing period may be associated with the hydration kinetics of MgO particles in the formation of Brucite (Mg(OH)

2). Samples carbonated after 24 hours exhibited lower mechanical performance than samples carbonated after 48 hours. This may be related to the increased availability of alkali species after 48 hours of MgO particle hydration with available water in the system. In contrast, it is observed that after 72 hours, the carbonation process led to a decrease in the average MOR values, representing a decrease of approximately 17%. The carbonation process reduced the average values of SE of the produced composites. This is associated with the increased stiffness of the boards and a reduction in the total voids within the cementitious matrix.

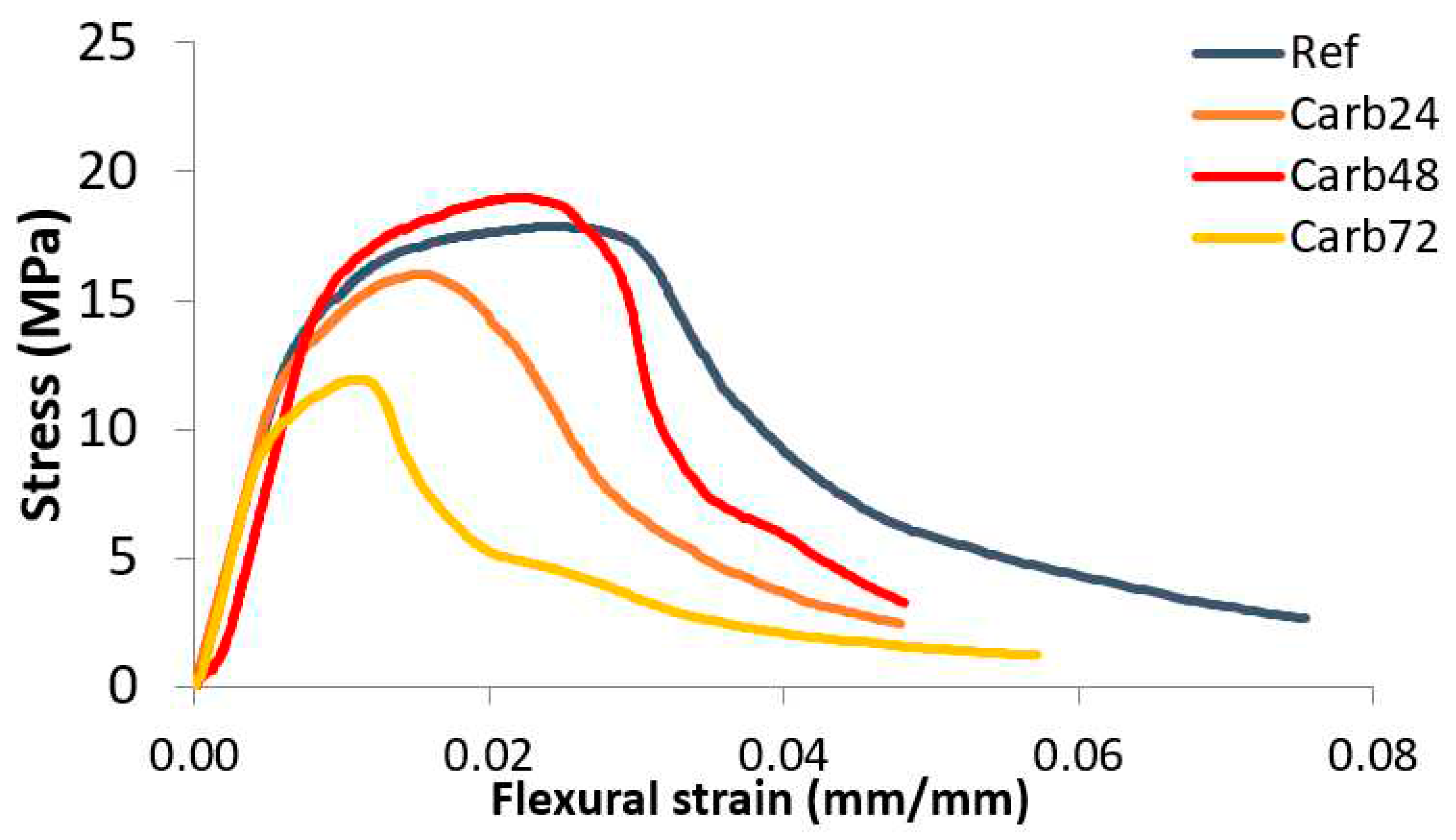

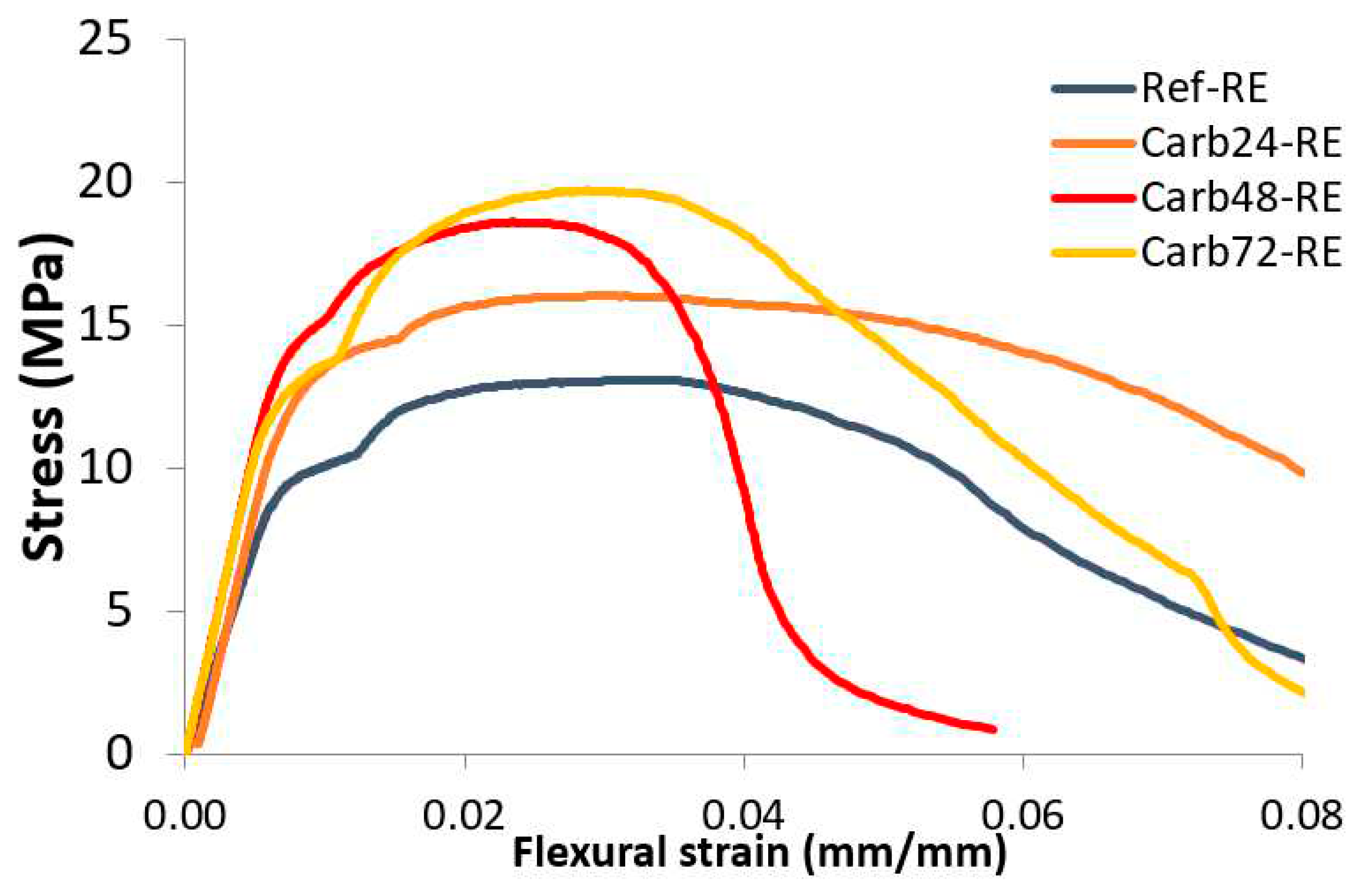

The

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 present the tension-deflection curves of the non-rehydrated and rehydrated MOS-based composites.

Comparing the

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, the rehydration process of the samples before curing in a CO

2-rich atmosphere increased the mechanical strength of the materials. The reference composites showed lower gains in mechanical strength when compared to the non-rehydrated materials. This was associated with the increased formation of brucite in the materials after rehydration, which promotes the formation of microcracks during the expansion of Mg(OH)

2 crystals, leading to a decrease in the mechanical strength of the boards. Rehydrated and carbonated composites after 48 and 72 hours exhibited the highest gains in mechanical strength among the materials studied. This was associated with the increased formation of alkali species 48 and 72 hours after plate production and immersion in water before carbonation curing.

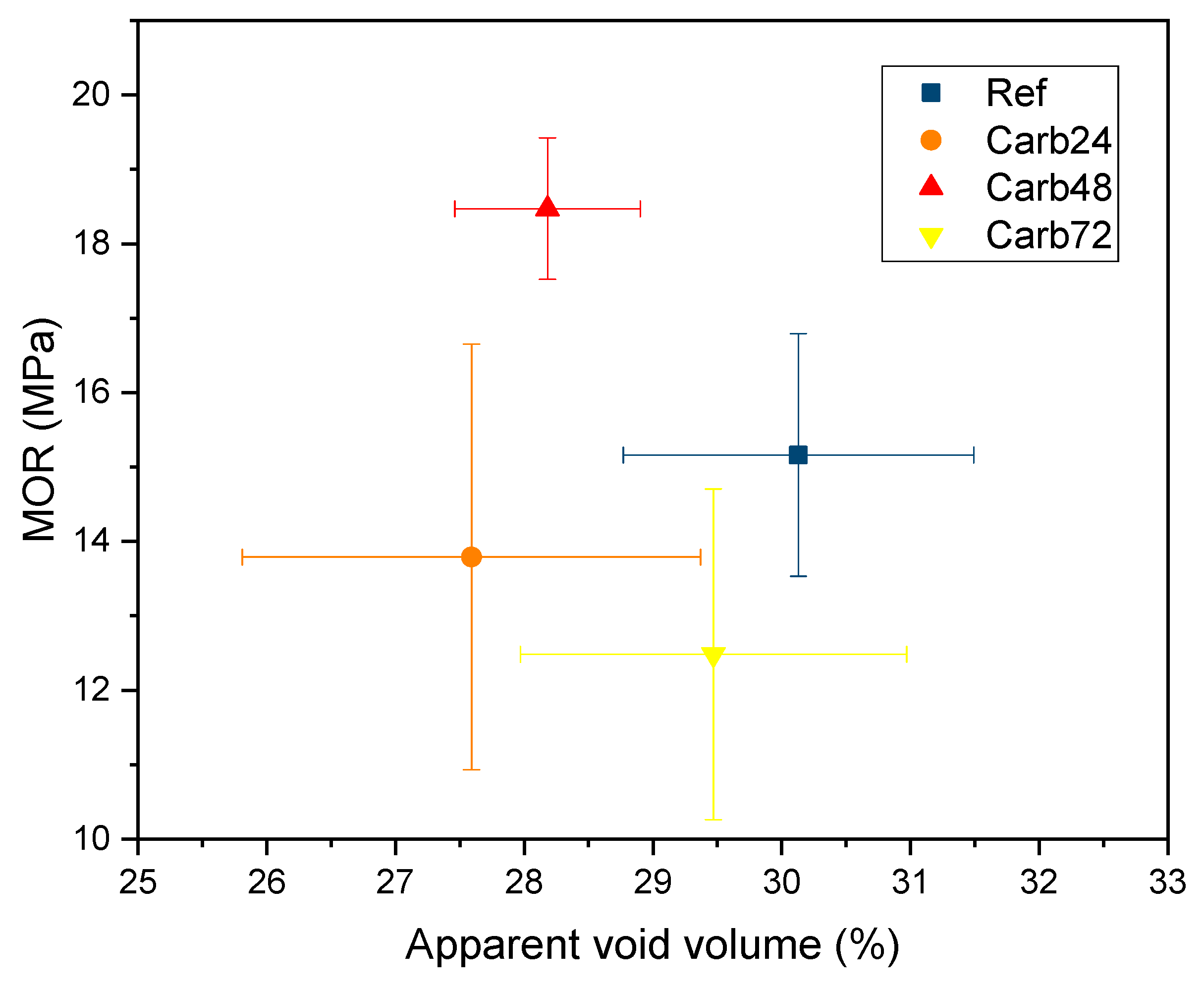

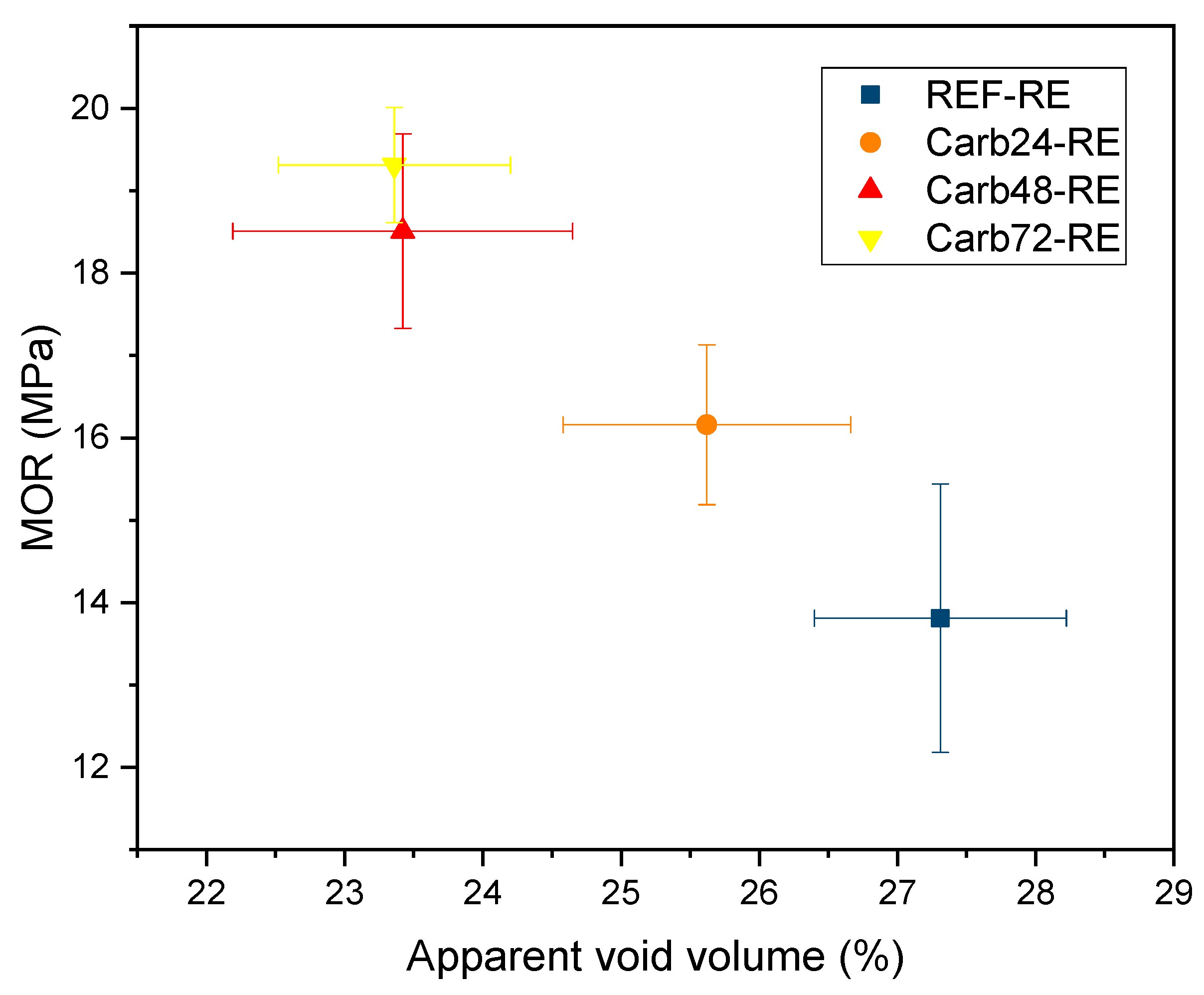

The effect of accelerated carbonation on the properties of rehydrated and non-rehydrated fiber cement can be observed in the

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. The carbonation process led to a trend of decreasing the average values of apparent void volume in the produced composites. However, the alteration of the pre-carbonation period modified the MOR values of the materials. Composites carbonated after 48 hours (Carb28) showed average void volume and MOR values close to 28% and 18.5 MPa, respectively. The rehydration of materials reduced void values to around 23.5% and maintained the average MOR values at 18.5 MPa.

From the analysis of

Figure 8, it can be observed that the carbonation process with rehydration increased the mechanical strength of the boards and reduced the total void content of the materials for composites cured after 72 hours (Carb72-RE). The increase in the mechanical performance of Carb72-RE boards is noteworthy, which increased 35.6% in MOR values and 35.5% in average specific energy values. By analyzing typical stress-strain curves, it can be seen that Carb48-RE and Carb72-RE composites exhibited the highest MOR values among carbonated samples after rehydration. However, Carb72-RE samples showed higher deformation during mechanical loading, which aligns with their higher Specific Energy values at 4.08 KJ/m

2.

3.2. Physical Properties

The physical properties of carbonated cementitious composites are presented in

Table 5 and

Table 6. It is evident that the accelerated carbonation process led to changes in the average values of water absorption, apparent porosity, and apparent density of the carbonated materials (both rehydrated and non-rehydrated). The non-rehydrated boards showed higher average water absorption values when compared to the carbonated boards at different pre-cure times and after the rehydration of the boards. The decrease in water absorption by the carbonated boards after rehydration was associated with the improved carbonation process of the rehydrated materials, which promoted the formation of new carbonation products in the existing voids of the composites. The formation of carbonation products was favored by an extended pre-cure period and rehydration of the boards before curing in a CO

2-rich environment. The apparent density of the boards is indicative of carbonate formation during accelerated carbonation. The rehydration process of the boards before accelerated carbonation favored an increase in the average density values. An increase of approximately 8.2, 4.3, 5.2, and 8.0% in the average apparent density values was observed for the Ref-RE, Carb24-Re, Carb48-RE, and Carb72-RE samples, respectively. The similar density increase observed in the reference and Carb72-RE samples was associated with the formation of a larger quantity of Mg(OH)

2 in the samples after the rehydration process. However, the gain in mechanical strength of the Ref-RE boards is not comparable to the values obtained in the Carb48-RE and Carb72-RE boards, with the density increase being related to the formation of carbonate products that enhance the mechanical performance of the composites.

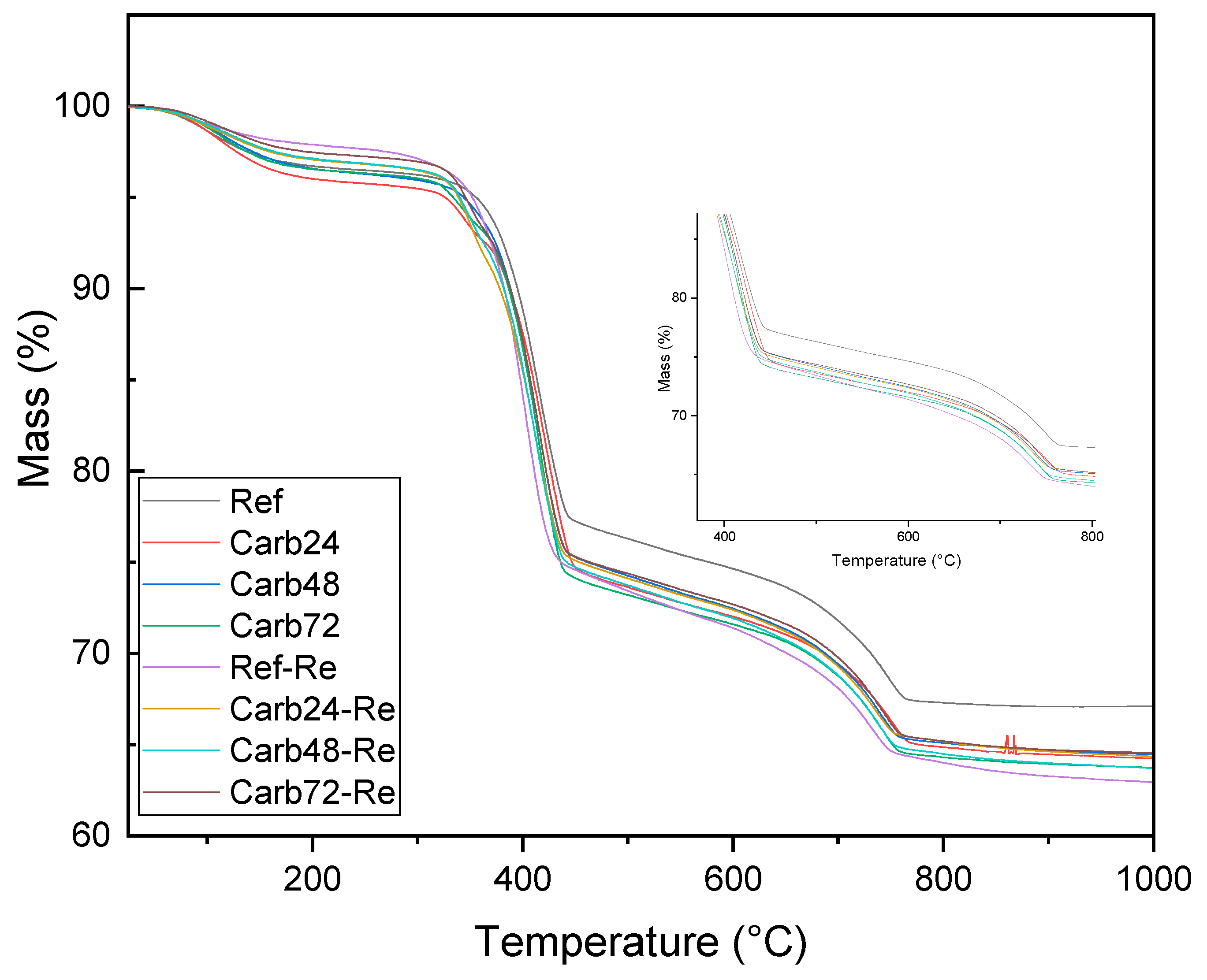

3.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA/DTG)

The thermogravimetric analyses of carbonated (rehydrated and non-rehydrated) MOS matrix fiber-cement samples are presented in

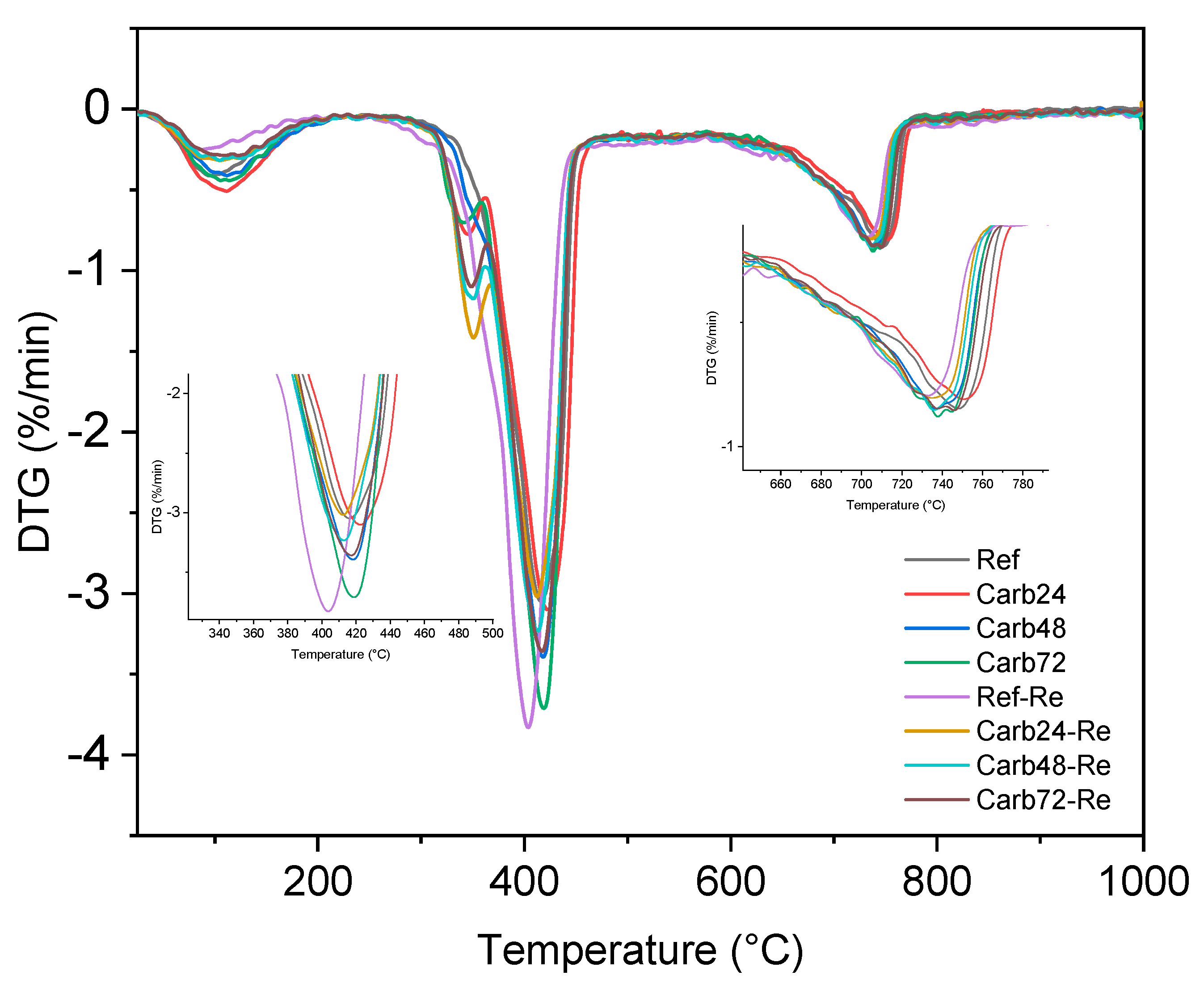

Figure 9. It is apparent that the analyzed materials exhibited similar behavior regarding thermal decomposition.

Figure 10 reveals that these materials displayed four distinct thermal events at similar temperatures. In the temperature range of 90 to 200 °C, a mass loss is observed, attributed to the decomposition of water molecules physically adsorbed on the surface and the commencement of decomposition of water molecules within the crystalline lattice of the 5-1-7 phase. This phase is primarily responsible for the enhancement of mechanical strength in MOS-type cement.

The analysis of

Figure 10 is possible to observe a second thermal event occurring at temperatures near 300-370 °C, associated with the decomposition of lignocellulosic material used as reinforcement in the produced composites. The most significant mass loss is observed within the temperature range of 390-500 °C, linked to the decomposition of brucite crystals formed during the hydration of MgO. Notably, a more pronounced peak is discerned in the sample labeled as Ref-RE, which underwent rehydration but not carbonation. This observation can be attributed to an excess of water molecules in the rehydrated and non-carbonated boards, as the accelerated carbonation process consumes water molecules for the formation of hydrated magnesium carbonates (Equations 2 and 3). The Ref-RE boards exhibit a higher quantity of brucite due to the hydration reactions occurring after the rehydration of MgO crystals that are not entirely consumed.

The increased formation of Mg(OH)2 following the initiation of the curing process of the boards can be linked to the development of microcracks within the system due to expansion reactions occurring during the hydration of MgO. This phenomenon may be connected to the reduced mechanical performance of the boards when compared to non-carbonated and non-rehydrated composites (Ref), resulting in an approximate 9.0% decrease in the average MOR values of the boards. The carbonated samples under different pre-curing conditions exhibited similar mass losses. However, it is notable that materials rehydrated before curing in a CO2-rich atmosphere showed a decrease in the peak related to the decomposition of brucite. This could be attributed to the improved carbonation process of the boards through prior rehydration, facilitating the consumption of alkaline species for the formation of carbonates responsible for enhancing the mechanical properties of the studied materials.

The results from the DTG analysis reveal that the rehydrated but non-carbonated material exhibited a decomposition band at temperatures close to 400 °C, associated with brucite. In contrast, the carbonated materials (both rehydrated and non-rehydrated) displayed a shift of this band to higher temperatures (420 °C), linked to the formation of hydrated magnesium carbonates, as described in the work of Hay R., et al. (2020) [

24]. In their study, the authors found that the carbonation process, in addition to altering the decomposition temperature of brucite, led to greater mass loss in the carbonated samples due to decarbonization and increased dehydroxylation of these samples.

The mass loss observed in all samples in the temperature range between 650 and 790 °C is associated with the decomposition of the limestone used as filler in the production of MOS cement boards.

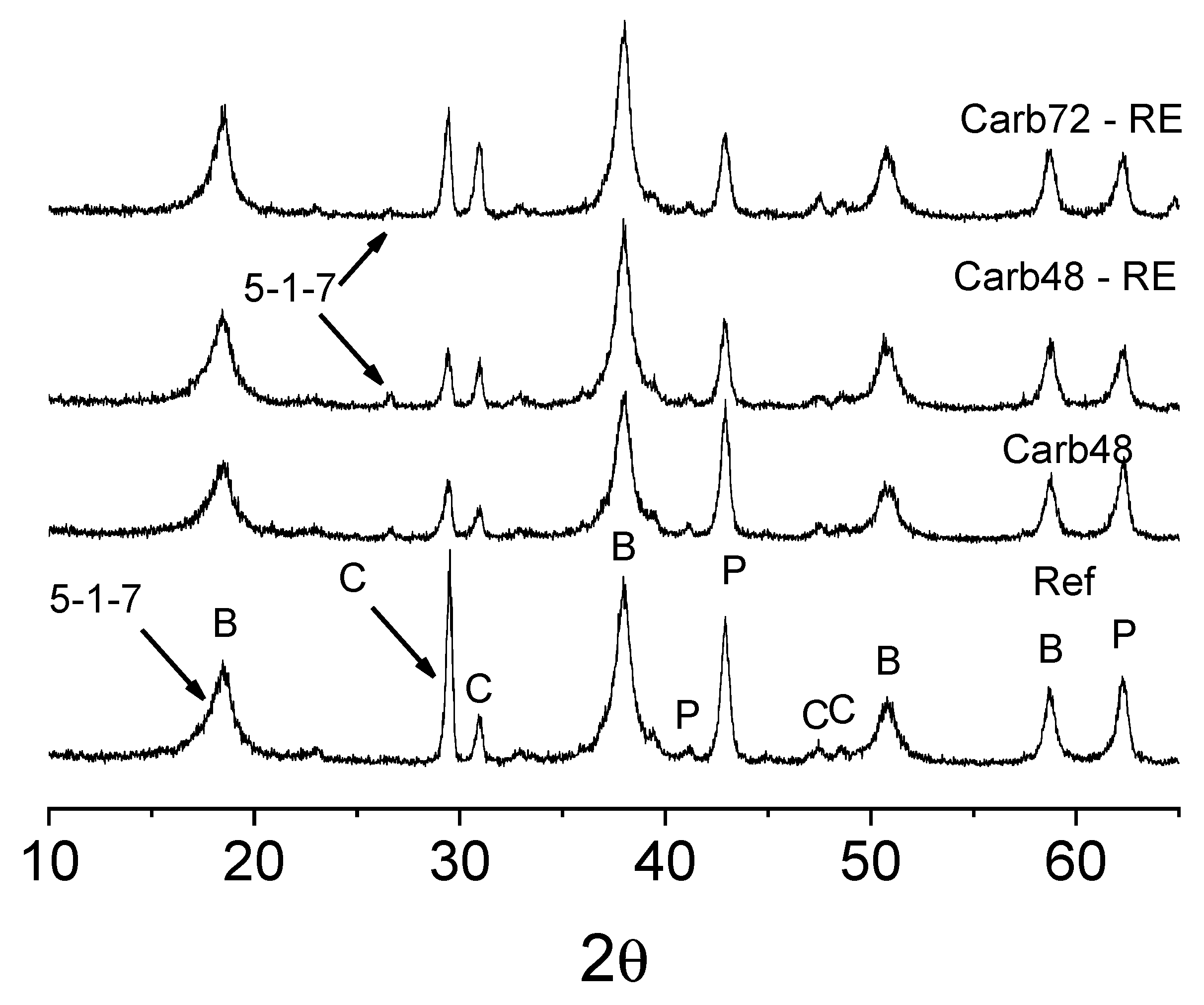

3.4. Phase analysis

The crystalline phases formed during the production of both carbonated and non-carbonated MOS matrix fiber cements were analyzed using X-ray diffraction, and the results are presented in

Figure 11. Prominent peaks associated with the brucite phase (COD 96-100-0055), Periclase (COD 96-900-6786), calcite (96-900-9669), and crystalline phases linked to the 5-1-7 phase, responsible for the mechanical strength of the resulting materials, are evident [

20,

24]. In the rehydrated samples, an increase in the intensity of the diffraction peaks related to the brucite phase can be observed. In the Carb48-RE and Carb72-RE samples, the Mg(OH)

2 phase peaks resemble those observed in the Ref sample (without carbonation), indicating that the rehydration process promotes the appearance of new hydration products that facilitate carbonation. Rehydrated samples also exhibited a decrease in the intensity of the peaks associated with the Periclase (MgO) phase, as observed at 43.0 2θ, which is related to the hydration of these MgO particles for the formation of Brucite.

It is possible to observe the presence of the 5-1-7 phase in the materials, which correlates with the demonstrated mechanical strength of these boards. However, a reduction in the intensity of the diffraction peak closely aligned with the 5-1-7 phase at angles around 26.7 2θ is observed. However, a reduction of this diffraction peak was observed in the carbonated samples after rehydration. This reduction in intensity may be associated with the formation of carbonation products with short-range atomic ordering (amorphous) on the surface of the boards, which interferes with the diffraction process of the other phases. This phenomenon may be linked to the decrease in the diffraction peaks of the calcite phases, a material used as a filler in the board formation, which exhibited reduced diffraction peaks in all samples after curing in a CO2-rich atmosphere (29.4 and 31.04 2θ).

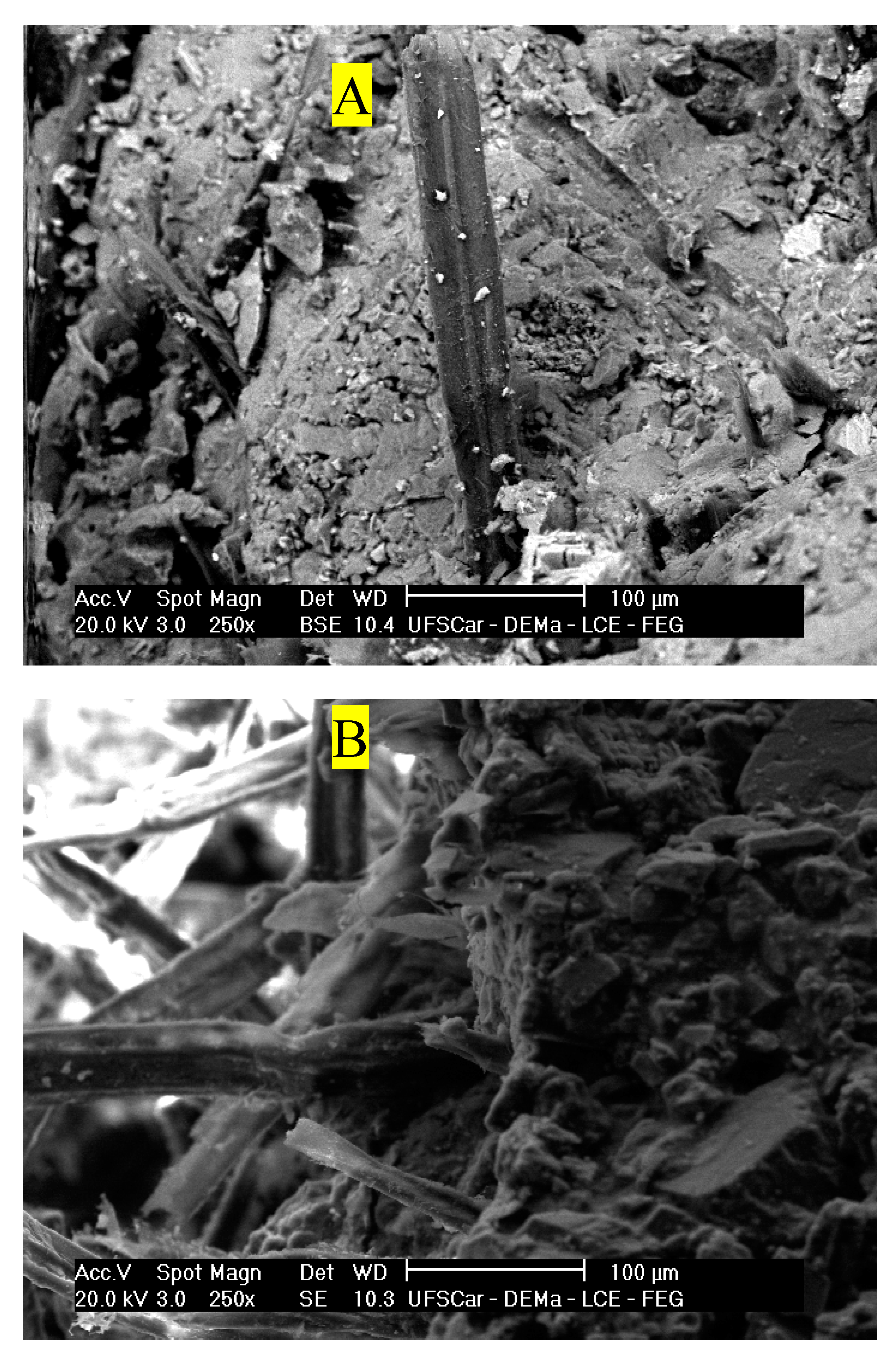

3.4. SEM analysis

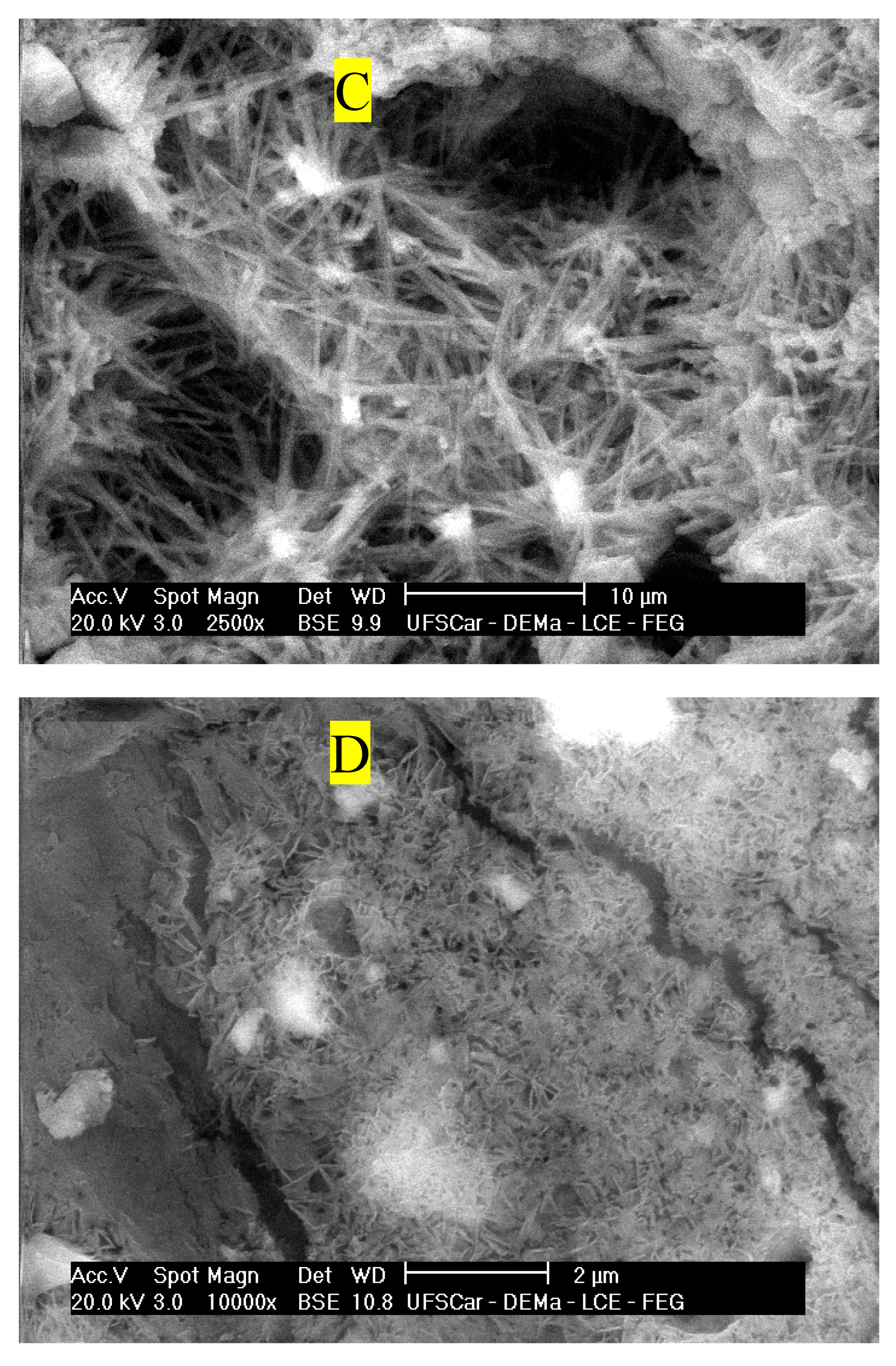

The analysis of the morphology of both carbonated and non-carbonated composites is presented in

Figure 12A–E. It is evident that the lignocellulosic materials are embedded in the MgO-based matrix. These materials adhere to the inorganic matrix, and in

Figure 12 A and

Figure 12 B, one can observe fibers with a fractured appearance after mechanical loading. This phenomenon is related to the strong bond between the fiber and the matrix, facilitating the transfer of energy during the mechanical test and contributing to the increased specific energy of the materials, as observed in the mechanical property results of the boards. The presence of needle-shaped crystals (

Figure 12 C) related to the 5-1-7 phase was found in the materials under all conditions, demonstrating that the formulation used facilitated the formation of species responsible for the mechanical strength gain in the studied materials.

Figure 12 D the morphology of the Carb72 samples, which were not subjected to prior rehydration, is observed. The presence of Brucite (Mg(OH)

2) crystals on the surface of the samples is identifiable. This may be associated with the extended period before curing in a CO

2-enriched environment. However, microcracks are evident, which could be linked to the expansion processes during the hydration of MgO. The presence of these microdefects may be associated with the reduction in mechanical strength observed in these samples and the increase in the average values of water absorption and porosity.

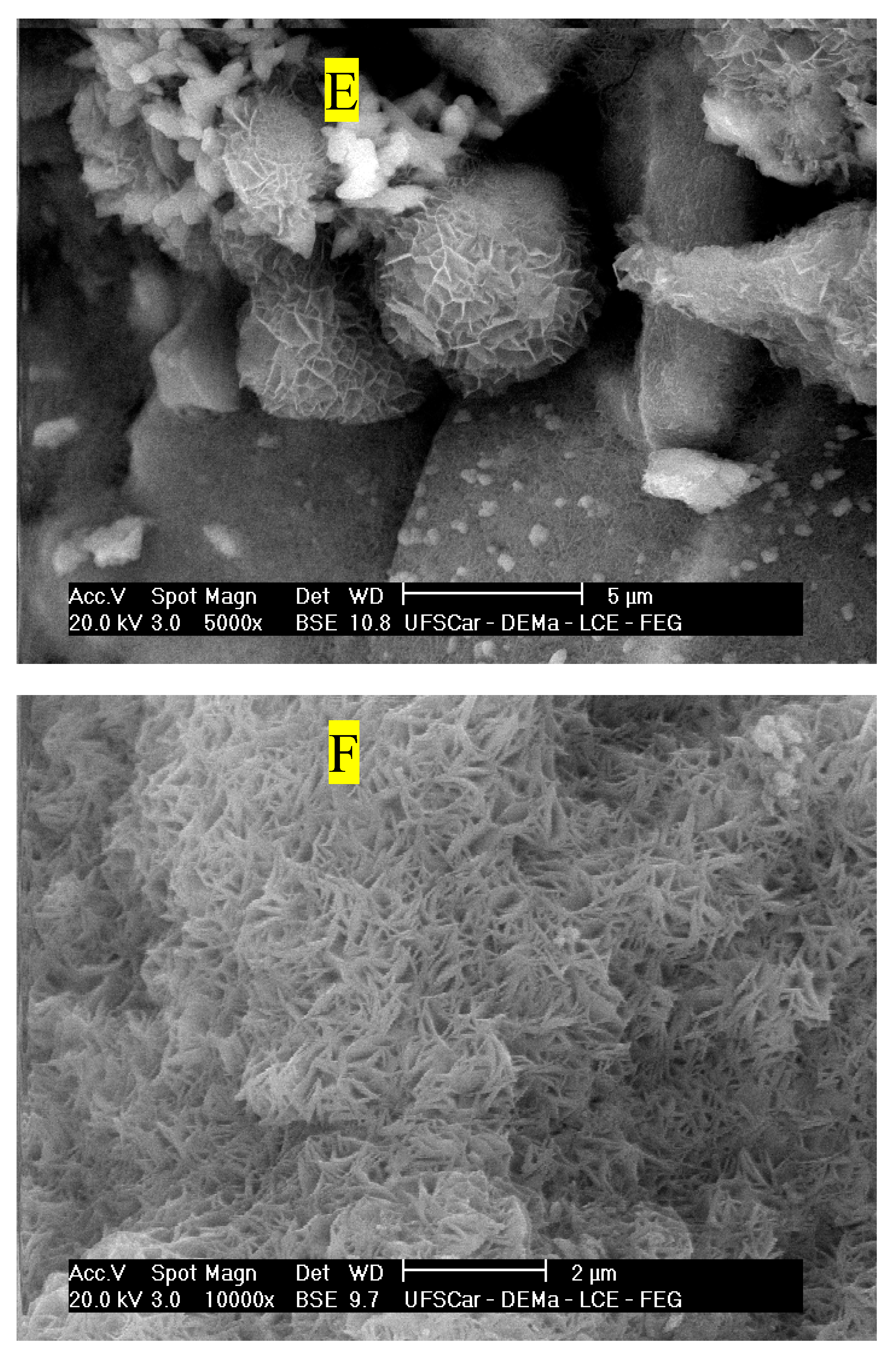

Rehydration of the samples before the accelerated carbonation process led to alterations in the physico-mechanical properties of the composites, associated with the formation of new compounds. The presence of Hydromagnesite (4MgCO

3⋅Mg(OH)

2⋅4H

2O) in the Carb48-RE and Carb72-RE samples is notable. The appearance of this compound related to carbonation aligns with the findings in the work of Unluer et al., (2011), where the authors demonstrated that hydromagnesite crystals can form in environments containing Mg(OH)

2, CO

2, and additional water, correlating with the rehydrated materials after 48 and 72 hours. The extended pre-curing period (48 and 72 hours) is linked to increased hydration of the MgO crystals and the formation of Mg(OH)

2, which promotes the formation of 4MgCO

3⋅Mg(OH)

2.4H

2O after carbonation and results in the observed alterations in the physico-mechanical properties of the carbonated composites [

25].

4. Discussion

The production of MOS matrix fiber cements serves as an alternative for mitigating the release of pollutants during the production of cementitious composites with common Portland cement matrices. The use of lignocellulosic fibers provides an alternative to asbestos and enhances the mechanical performance of the materials. The accelerated carbonation process employed in this study has proven to be an effective curing method for improving the final properties of composites produced with MOS matrices. It is essential to control the duration before exposure to a CO2-enriched atmosphere and the provision of extra water before carbonated curing through board rehydration. Accelerated carbonation of MOS cement is achieved through the reaction of brucite, the main product of MgO hydration, with CO2. Carbonated materials exhibited increased average values of the modulus of rupture (MOR) and modulus of elasticity (MOE) due to the formation of carbonation products. Carbonation reactions occur within the voids and pores of the matrices, promoting matrix stiffening, which results in reduced water absorption and apparent porosity values. Carbonation showed improvement when board rehydration was applied before exposure to a CO2-rich atmosphere. Longer periods before carbonation and prior rehydration favored the enhancement of the mechanical strength of the boards, with Carb48-RE and Carb72-RE samples showing the highest average MOR values among the materials studied. Rehydration facilitated the appearance of hydromagnesite crystals, which are observed in environments with high concentrations of Mg(OH)2, CO2, and H2O and may be associated with the reduction in the intensity of diffraction peaks related to brucite, as observed in carbonated materials with prior rehydration. The use of accelerated carbonation brought more significant changes in the properties of non-rehydrated materials cured after 48 hours and rehydrated materials cured after 48 and 72 hours. The rehydration process can be applied to these materials to increase the water content in the system, promoting more hydration products, facilitating CO2 dissolution, and subsequent carbonation of MOS cement-based boards. Rehydrating MOS matrix fiber cement boards before carbonation can be an alternative due to the water loss caused by the Hatschek process simulation. This procedure, in addition to generating more hydration products, enhances the material's mechanical performance, which may be of interest to the fiber cement board market.

Conclusions

Analyzing the results related to the production and carbonation of MOS matrix fiber cement boards, several important points can be concluded: i) The production of boards using the Hatschek process simulation was successful, and the materials exhibited satisfactory mechanical behavior after different types of curing were applied; ii) The accelerated carbonation process of the boards resulted in more significant improvements in the rehydrated composites, with the formation of hydromagnesite observed in these materials after curing in a CO2-rich environment; iii) The pre-curing applied before carbonation proved to be a crucial parameter to control for obtaining materials without microcracks and enhanced mechanical properties; iv) The use of MOS cement in the production of fiber cement boards can be an alternative to the traditionally employed inorganic binders, as they exhibit superior mechanical properties that can be further enhanced by the application of accelerated carbonation to the materials.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

To the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) - Processes: 2021/04780-7, 2022/07179-5, and 2014/50948-3. To the CNPQ- Processes: 422701/2021-1 and 402980/2022-0. To the NOVA University of Lisbon and the University of Minho.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- M.A. Shand, Magnesium oxysulfate cement, Magnesia Cem. (2020) 75–83. [CrossRef]

- F. Chen, Study on preparation and properties of modified magnesium oxysulfate cements, Chem. Eng. Trans. 62 (2017) 973–978. [CrossRef]

- Walling, S.A.; Provis, J.L. Magnesia-Based Cements: A Journey of 150 Years, and Cements for the Future? Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 4170–4204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ba, M.; Xue, T.; He, Z.; Wang, H.; Liu, J. Carbonation of magnesium oxysulfate cement and its influence on mechanical performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 223, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, K.; Chen, B.; Yu, H.; Zhang, N.; Bi, W.; Guan, Y. Characterization of magnesium-calcium oxysulfate cement prepared by replacing MgSO4 in magnesium oxysulfate cement with untreated desulfurization gypsum. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 121, 104091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Li, C.; Zhao, F. Study on water resistance modification of magnesium oxysulfate cement. IOP Conf. Series: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 493, 012079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demediuk, T.; Cole, W. A study of Mangesium Oxysulphates. Aust. J. Chem. 1957, 10, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. MÁRMOL DE LOS DOLORES, Low-alkalinity matrix composites based on magnesium oxide cement reinforced with cellulose fibres, (2017) 161.

- Benhelal, E.; Zahedi, G.; Shamsaei, E.; Bahadori, A. Global strategies and potentials to curb CO2 emissions in cement industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 51, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juenger, M.; Winnefeld, F.; Provis, J.; Ideker, J. Advances in alternative cementitious binders. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 1232–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhu, X.; Wang, J.; Mu, M.; Wang, Y. Comparison of CO2 emissions from OPC and recycled cement production. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 211, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Habert, G.; Bouzidi, Y.; Jullien, A. Environmental impact of cement production: detail of the different processes and cement plant variability evaluation. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddalena, R.; Roberts, J.J.; Hamilton, A. Can Portland cement be replaced by low-carbon alternative materials? A study on the thermal properties and carbon emissions of innovative cements. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liska, M.; Al-Tabbaa, A.; Carter, K.; Fifield, J. Scaled-up commercial production of reactive magnesium cement pressed masonry units. Part I: Production. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. - Constr. Mater. 2012, 165, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shand, M.A. The Chemistry and Technology of Magnesia; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nobre, J.; Ahmed, H.; Bravo, M.; Evangelista, L.; de Brito, J. Magnesia (MgO) Production and Characterization, and Its Influence on the Performance of Cementitious Materials: A Review. Materials 2020, 13, 4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. DIONISIO SOUSA DE OLIVEIRA, EFEITO DA CURA SOB PRESSÃO E ALTA TEMPERATURA NO CIMENTO OXISSULFATO DE MAGNÉSIO, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 2020.

- Dung, N.; Lesimple, A.; Hay, R.; Celik, K.; Unluer, C. Formation of carbonate phases and their effect on the performance of reactive MgO cement formulations. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 125, 105894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Ba, M.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, N.; Wang, F. Effects of citrate acid, solidum silicate and their compound on the properties of magnesium oxysulfate cement under carbonation condition. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Su, A.; Gao, X. Preparation of durable magnesium oxysulfate cement with the incorporation of mineral admixtures and sequestration of carbon dioxide. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 809, 152127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mármol, G.; Savastano, H. Study of the degradation of non-conventional MgO-SiO2 cement reinforced with lignocellulosic fibers. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2017, 80, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savastano, H.; Warden, P.; Coutts, R. Brazilian waste fibres as reinforcement for cement-based composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2000, 22, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Unluer, C.; Yang, E.-H.; Qian, S. Recent advances in magnesium-based materials: CO2 sequestration and utilization, mechanical properties and environmental impact. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, R.; Celik, K. Hydration, carbonation, strength development and corrosion resistance of reactive MgO cement-based composites. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 128, 105941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Unluer, A. C. Unluer, A. Al-Tabbaa, Green Construction with carbonating reactive magnesia porous blocks: effect of cement and water contents, Proc 2nd Int. Conf. Futur. Concr. (2011) 1–11.

Figure 1.

Particle size distribution of MgO used to produce the MOS cement boards.

Figure 1.

Particle size distribution of MgO used to produce the MOS cement boards.

Figure 2.

X ray diffraction of MgO used to produce the MOS cement boards.

Figure 2.

X ray diffraction of MgO used to produce the MOS cement boards.

Figure 3.

Histogram of the length distribution of pulp reinforcement.

Figure 3.

Histogram of the length distribution of pulp reinforcement.

Figure 4.

Histogram of the width distribution of pulp reinforcement.

Figure 4.

Histogram of the width distribution of pulp reinforcement.

Figure 5.

Tension-deflection curves of the non-rehydrated MOS-based composites.

Figure 5.

Tension-deflection curves of the non-rehydrated MOS-based composites.

Figure 6.

Tension-deflection curves of the rehydrated MOS-based composites.

Figure 6.

Tension-deflection curves of the rehydrated MOS-based composites.

Figure 7.

Average values of modulus of rupture (MOR) vs. apparent void volume of non-rehydrated composites. Horizontal and vertical lines indicate the standard deviation of each sample.

Figure 7.

Average values of modulus of rupture (MOR) vs. apparent void volume of non-rehydrated composites. Horizontal and vertical lines indicate the standard deviation of each sample.

Figure 8.

Average values of modulus of rupture (MOR) vs. apparent void volume of rehydrated composites. Horizontal and vertical lines indicate the standard deviation of each sample.

Figure 8.

Average values of modulus of rupture (MOR) vs. apparent void volume of rehydrated composites. Horizontal and vertical lines indicate the standard deviation of each sample.

Figure 9.

TGA analysis of rehydrated and non-rehydrated carbonated MOS-based fiber cement.

Figure 9.

TGA analysis of rehydrated and non-rehydrated carbonated MOS-based fiber cement.

Figure 10.

TGA analysis of rehydrated and non-rehydrated carbonated MOS-based fiber cement.

Figure 10.

TGA analysis of rehydrated and non-rehydrated carbonated MOS-based fiber cement.

Figure 11.

Diffraction patterns of rehydrated and non-rehydrated carbonated MOS-based fiber cement.

Figure 11.

Diffraction patterns of rehydrated and non-rehydrated carbonated MOS-based fiber cement.

Figure 12.

SEM images of rehydrated and non-rehydrated carbonated MOS-based fiber cement. (A) Ref, (B) Carb48, (C) Carb48, (D) Carb72, (E) Carb72-RE and (F) Carb72-RE.

Figure 12.

SEM images of rehydrated and non-rehydrated carbonated MOS-based fiber cement. (A) Ref, (B) Carb48, (C) Carb48, (D) Carb72, (E) Carb72-RE and (F) Carb72-RE.

Table 1.

Chemical composition and loss of ignition (LOI) of MgO and dolomitic limestone used in MOS-based boards formulation.

Table 1.

Chemical composition and loss of ignition (LOI) of MgO and dolomitic limestone used in MOS-based boards formulation.

| Compound |

Dolomitic Limestone (wt%) |

MgO(wt%) |

| MgO |

7.6 |

97.4 |

| Al2O3

|

1.03 |

<0.10 |

| SiO2

|

3.99 |

0.1 |

| P2O5

|

0.05 |

_ |

| SO3

|

0.13 |

_ |

| Cl |

0.01 |

_ |

| K2O |

0.22 |

<0.10 |

| Na2O |

_ |

<0.10 |

| CaO |

43.9 |

0.81 |

| TiO2

|

0.06 |

_ |

| MnO |

0.09 |

_ |

| Fe2O3

|

0.42 |

_ |

| ZnO |

<0.01 |

_ |

| Rb2O |

<0.02 |

_ |

| SrO |

<0.03 |

_ |

| LOI |

42.4 |

1.6 |

Table 2.

Chemical composition of unbleached Eucalyptus fiber used as reinforcement in the fiber cement.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of unbleached Eucalyptus fiber used as reinforcement in the fiber cement.

| Type of fibre |

Chemical Composition (%) |

| Cellulose |

Hemicellulose |

Lignin |

Others |

| Eucalyptus (unbleached) |

82.55 |

8.39 |

1.73 |

7.33 |

Table 3.

Different samples produced by rehydration and accelerated carbonation processes.

Table 3.

Different samples produced by rehydration and accelerated carbonation processes.

| Sample |

Period until start the accelerated carbonation process |

| Ref |

Without rehydration and carbonation |

| Ref-RE |

Rehydrated carbonated boards |

| Carb24 |

24 hours without rehydration |

| Carb48 |

48 hours without rehydration |

| Carb72 |

72 hours without rehydration |

| Carb24-RE |

24 hours with rehydration |

| Carb48-RE |

48 hours with rehydration |

| Carb72-RE |

72 hours with rehydration |

Table 4.

Mechanical proprieties of rehydrated and non-rehydrated carbonated MOS-based fiber cement.

Table 4.

Mechanical proprieties of rehydrated and non-rehydrated carbonated MOS-based fiber cement.

| Sample |

MOR |

LOP |

MOE |

SE |

| (MPa) |

(MPa) |

(GPa) |

(KJ/m2) |

| Ref |

15.16±0.63 |

12.40±1.95 |

9.89±1.24 |

3.44±0.48 |

| Carb24 |

13.79±1.16 |

10.23±1.47 |

9.90±1.60 |

2.71±0.33 |

| Carb48 |

18.47±0.95 |

14.66±0.90 |

10.52±1.37 |

2.93±0.1 |

| Carb72 |

12.48±1.22 |

10.79±2.88 |

8.26±1.16 |

2.63±0.37 |

| Ref-RE |

13.81±1.63 |

8.75±0.29 |

9.48±0.34 |

4.41±1.11 |

| Carb24-RE |

16.16±0.97 |

12.03±1.65 |

13.44±1.69 |

3.60±1.63 |

| Carb48-RE |

18.51±1.18 |

12.73±1.02 |

14.83±1.48 |

3.28±0.31 |

| Carb72-RE |

19.31±0.70 |

12.39±1.22 |

13.57±0.25 |

4.08±0.62 |

Table 5.

Physical proprieties of non-rehydrated carbonated MOS-based fiber cement.

Table 5.

Physical proprieties of non-rehydrated carbonated MOS-based fiber cement.

| Sample |

Water Absorption(%) |

Apparent porosity(%) |

Bulk Density(g/cm3) |

| Ref |

19.98±1.48 |

30.13±0.76 |

1.46±0.01 |

| Carb24 |

18.08±1.76 |

27.59±0.78 |

1.53±0.05 |

| Carb48 |

19.09±1.87 |

28.18±1.03 |

1.52±0.05 |

| Carb72 |

19.38±1.40 |

29.47±1.13 |

1.50±0.05 |

Table 6.

Physical proprieties of rehydrated carbonated MOS-based fiber cement.

Table 6.

Physical proprieties of rehydrated carbonated MOS-based fiber cement.

| Sample |

Water Absorption(%) |

Apparent porosity(%) |

Bulk Density(g/cm3) |

| Ref-RE |

17.21±0.93 |

27.31±0.91 |

1.59±0.91 |

| Carb24-RE |

16.03±1.10 |

25.62±1.04 |

1.601±0.045 |

| Carb48-RE |

14.63±1.10 |

23.42±0.93 |

1.603±0.056 |

| Carb72-RE |

14.34±0.78 |

23.36±0.84 |

1.631±0.033 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).