Submitted:

31 October 2023

Posted:

01 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Koji and Miso

2.2. Physico-Chemical Parameters

2.2.1. Colour Measurement

2.2.2. Water Content, pH, and REDOX

2.2.3. Reducing Sugar content with Dinitrosalicylic Acid (DNS)

2.3. Protease Activity

2.4. Extraction and Identification of Kokumi Peptides by HPLC/Ms-Ms

2.5. Extraction and Quantification of Volatile Aroma Compounds by HS-SPME-GC/MS

2.6. Sensory Analysis

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

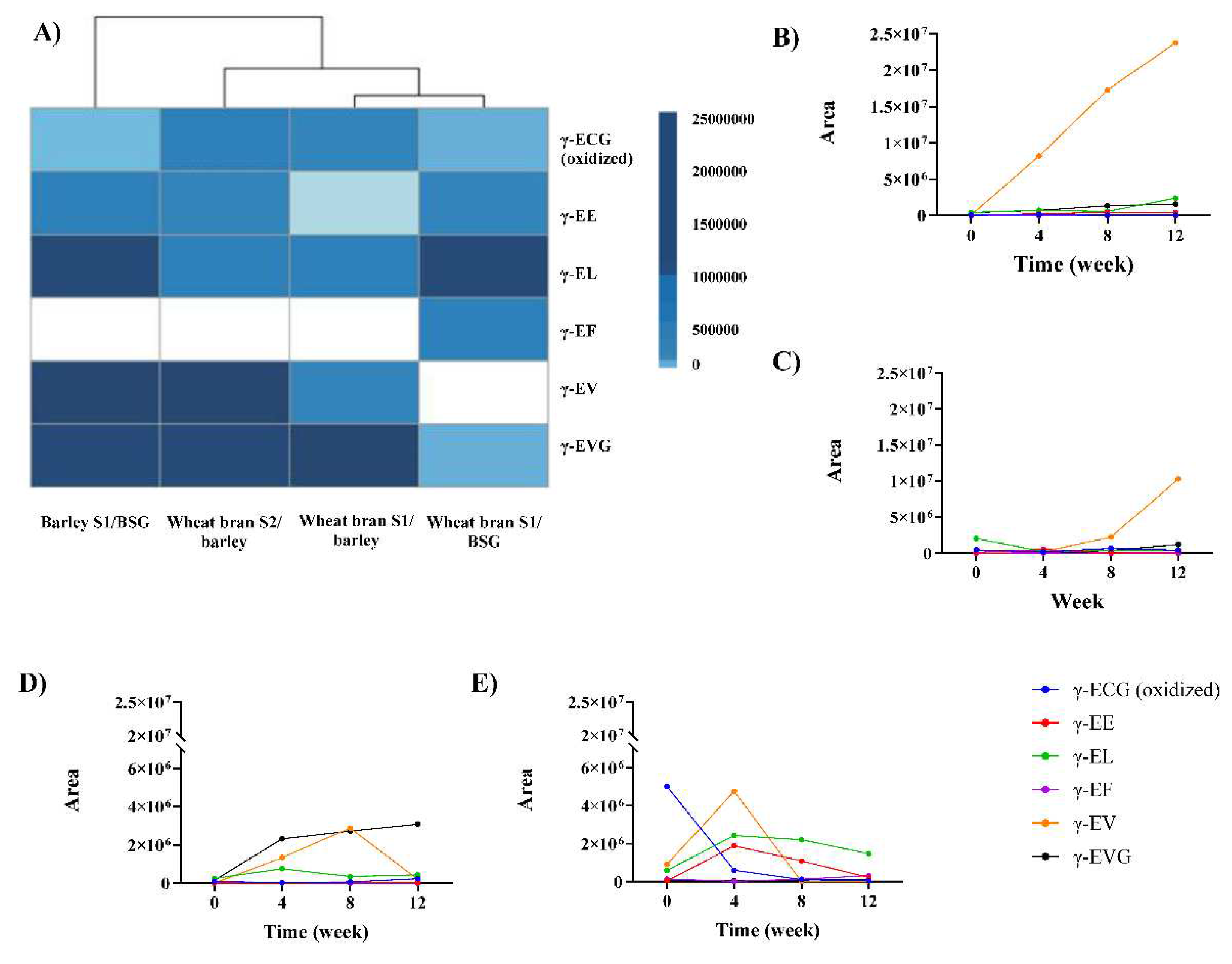

3.1. Miso Fermentation of Cereal Processing by-Products Generates γ-Glutamyl Peptides

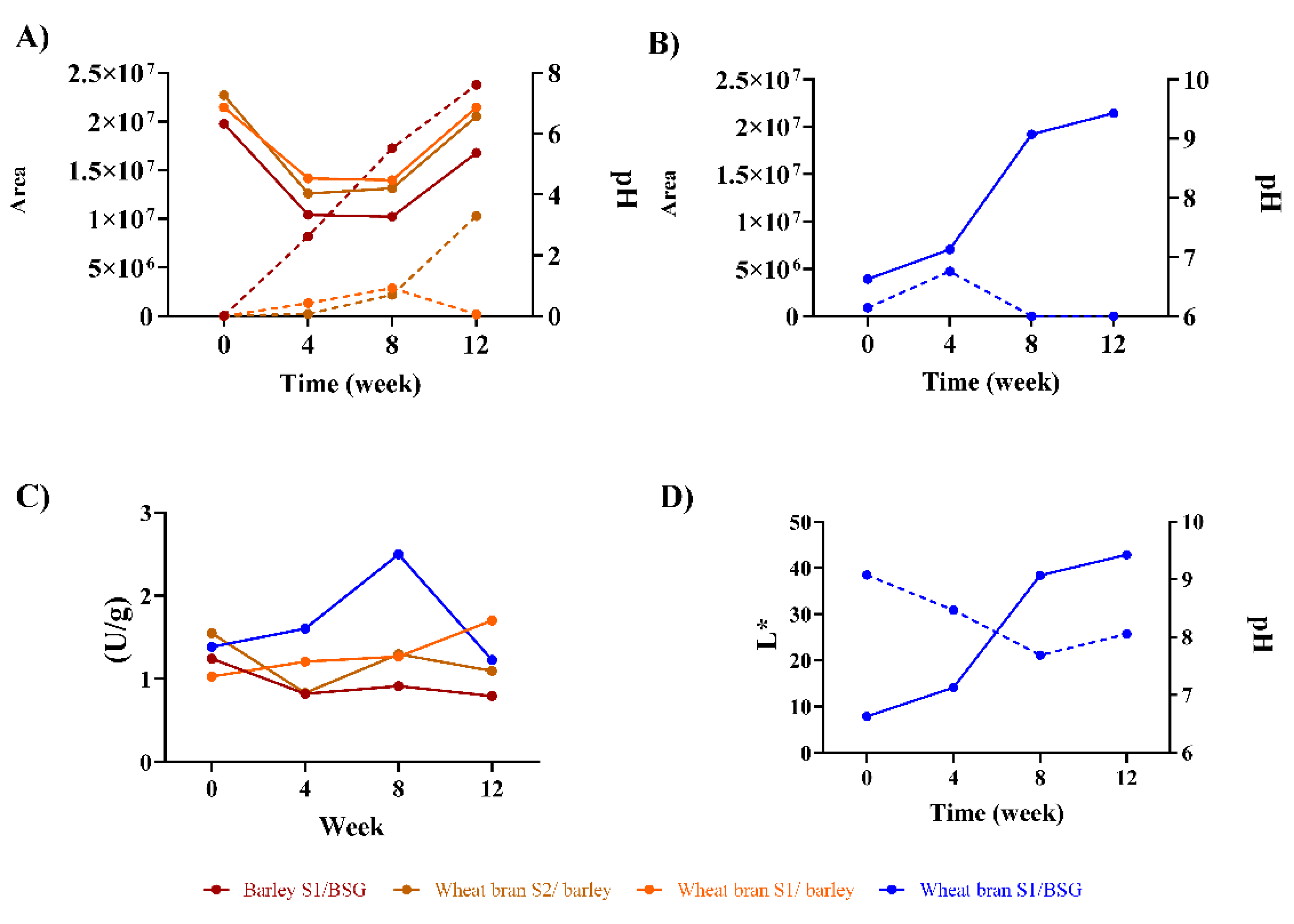

3.2. Physicochemical Changes in Fermentation Processes Influence the Generation of γ-Glutamyl Peptides

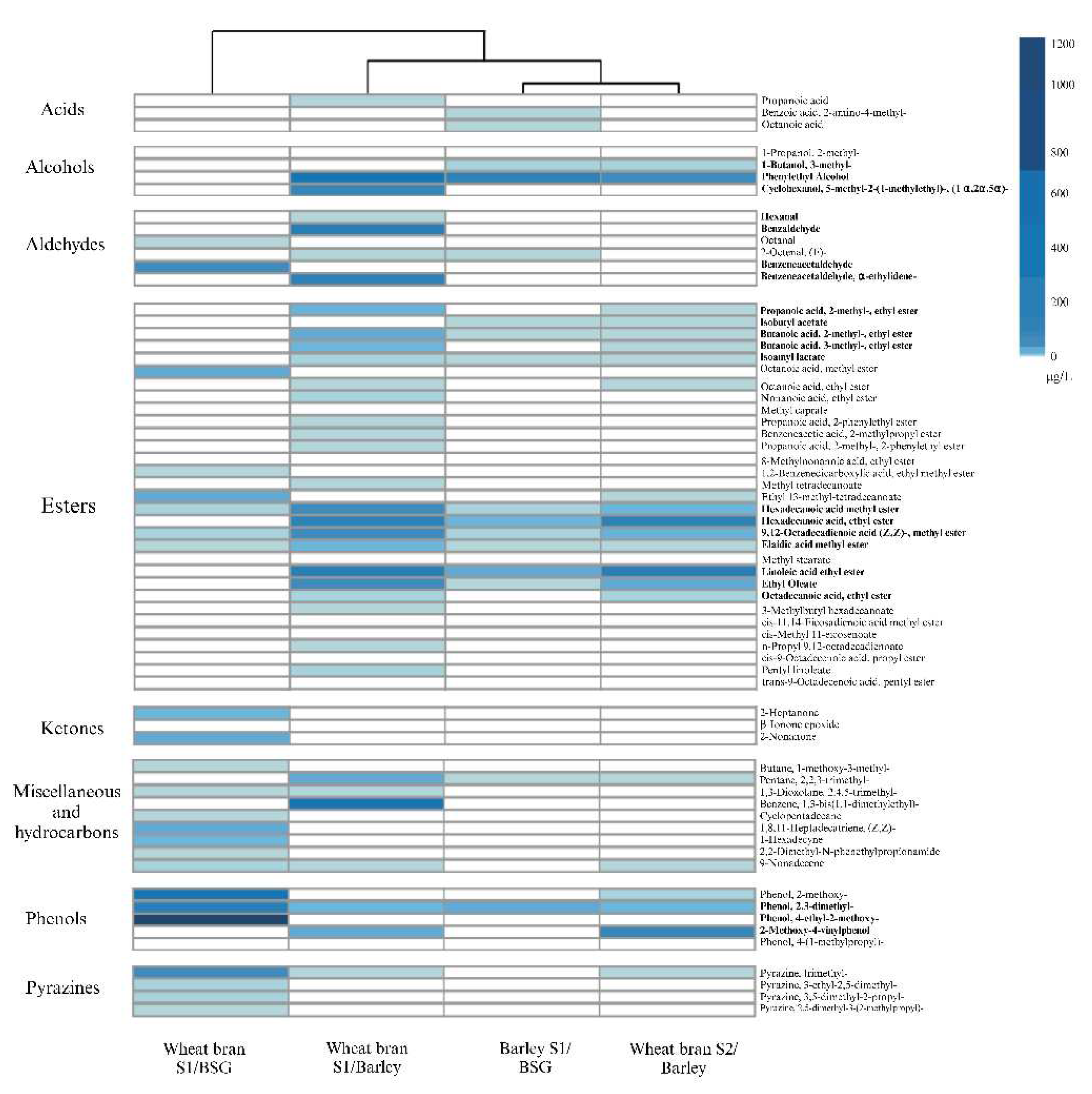

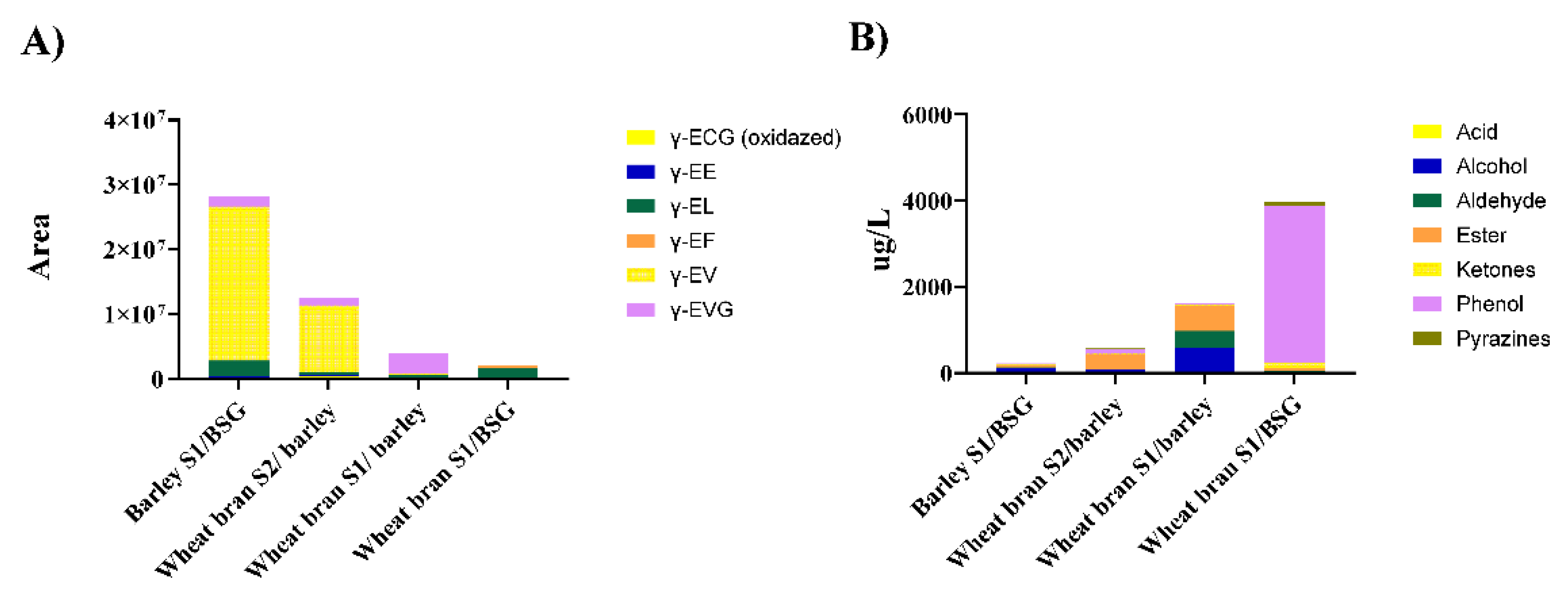

3.3. Volatile Aroma Compound Profiles of Upcycled Miso Reveal Correlation with g-Glutamyl Peptides

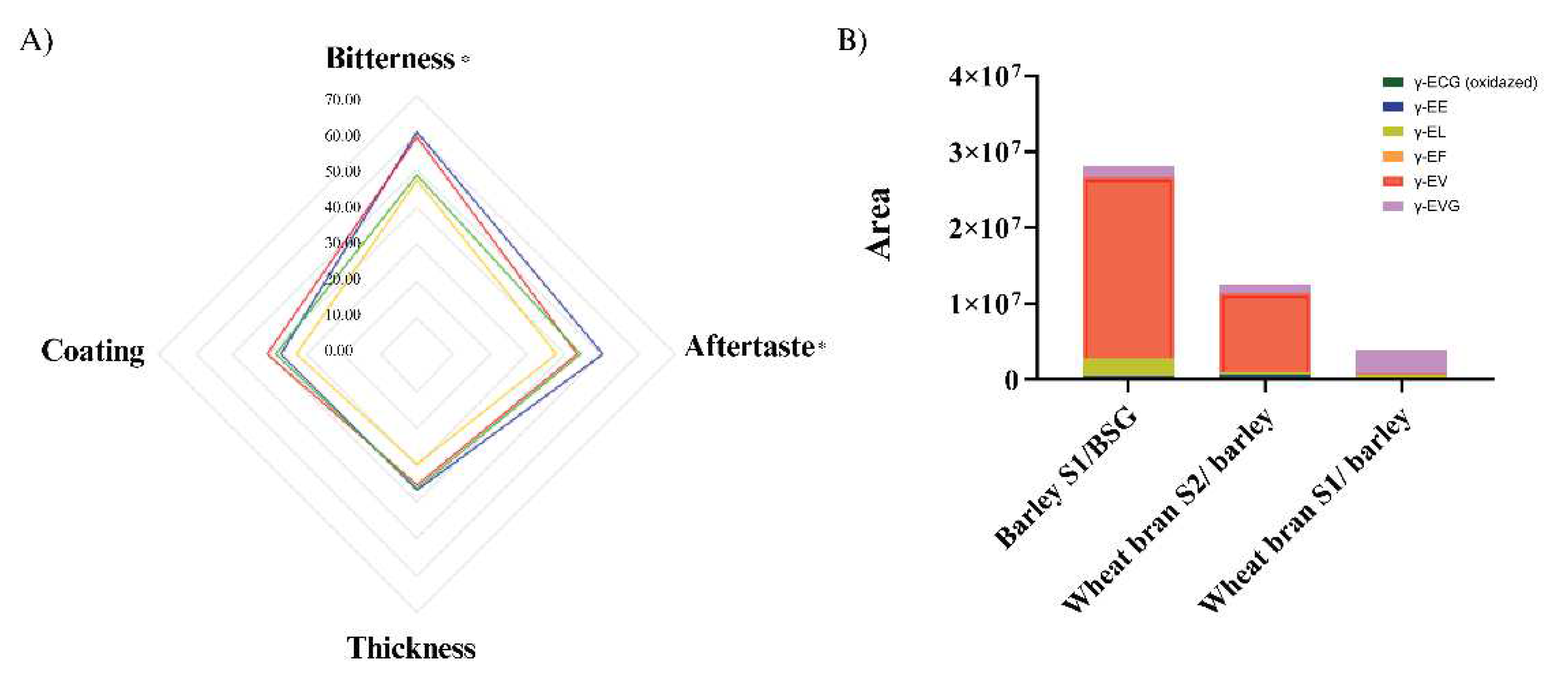

3.4. Addition of Kokumi Peptides Reduces Bitter Taste

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgement

References

- Ravindran, R.; Jaiswal, A.K. Exploitation of Food Industry Waste for High-Value Products. Trends in Biotechnology 2016, 34(1), 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Eat-Lancet Commission. 2019; Food Planet Health: Healthy Diets From Sustainable Food Systems. The Lancet.

- Agudelo Higuita, N.I.; LaRocque, R.; McGushin, A. Climate change, industrial animal agriculture, and the role of physicians – Time to act. Journal of Climate Change and Health 2023, 13(9), 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, T.; Little, D.; Röös, E. 2015; Lean, green, mean, obscene…? What is efficiency? And is it sustainable? Animal production and consumption reconsidered.

- Capanoglu, E.; Nemli, E.; Tomas-Barberan, F. Novel Approaches in the Valorization of Agricultural Wastes and Their Applications. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2022, 70(2), 6787–6804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, K.M.; Steffen, E.J.; Arendt, E.K. Brewers’ spent grain: a review with an emphasis on food and health. Journal of the Institute of Brewing 2016, 122(4), 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouritsen, O.G.; Styrbæk, K. Design and ‘umamification’ of vegetable dishes for sustainable eating. International Journal of Food Design 2020, 5(2), 9–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouritsen, O.G. Umamification of food facilitates the green transition. Soil Ecology Letters 2023, 5(1), 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, W.; Zhang, P.; Ying, D.; Fang, Z. Surmounting the off-flavor challenge in plant-based foods. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2022, 5(5), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hance, P.; Martin, Y.; Vasseur, J.; Hilbert, J.L.; Trotin, F. Quantification of chicory root bitterness by an ELISA for 11β,13-dihydrolactucin. Food Chemistry 2007, 105(2), 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, M.N.; Walczak, M.; Skrzypczak-Zielińska, M.; Jeleń, H.H. Bitter taste of Brassica vegetables: The role of genetic factors, receptors, isothiocyanates, glucosinolates, and flavor context. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2018, 58(8), 3130–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R.; Cavallo, C.; Cicia, G.; Del Giudice, T. Are (All) consumers averse to bitter taste? Nutrients 2019, 11(2), 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsch, A.; Roy, D.; LaPointe, G. Fermentation of Wheat Bran and Whey Permeate by Mono-Cultures of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus Strains and Co-culture With Yeast Enhances Bioactive Properties. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2020, 8(8), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, J.; Soladoye, O.P.; Aluko, R.E.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Preparation, receptors, bioactivity and bioavailability of γ-glutamyl peptides: A comprehensive review. Trends in Food Science and Technology 2021, 113(9), 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Bai, W.; Zeng, X.; Cui, C. Gamma glutamyl peptides: The food source, enzymatic synthesis, kokumi-active and the potential functional properties – A review. Trends in Food Science and Technology 2019, 91(5), 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Valerón, N.; Mak, T.; Jahn, L.J.; Arboleya, J.C.; Sörensen, P.M. Characterization of kokumi γ-glutamyl peptides and volatile aroma compounds in alternative grain miso fermentations. LWT Food Science and Technology 2023, 188(10), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, T.; Kuroda, M. Koku in Food Science and Physiology. Springer. 2019; Singapure. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onipe, O.O.; Jideani AI, O.; Beswa, D. (2015). Composition and functionality of wheat bran and its application in some cereal food products. International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2015, 50(12), 2509–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balandrán-Quintana, R.R.; Mercado-Ruiz, J.N.; Mendoza-Wilson, A.M. (2015). Wheat Bran Proteins: A Review of Their Uses and Potential. Food Reviews International 2015, 31(3), 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Zhang, J.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ma, H. A Mini-Review on Brewer’s Spent Grain Protein: Isolation, Physicochemical Properties, Application of Protein, and Functional Properties of Hydrolysates. Journal of Food Science 2019, 84(12), 3330–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Cui, C.; Zhao, H.; Gao, X.; Zhao, M.; Sun, W. (2012). Effect of koji fermentation on generation of volatile compounds in soy sauce production. International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2012, 48(3), 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.H.; Kim, M.K. Physiochemical quality and sensory characteristics of koji made with soybean, rice, and wheat for commercial doenjang production. Foods 2020, 9(8), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Chung, H.J.; Bang, W.S. Correlating physiochemical quality characteristics to consumer hedonic perception of traditional Doenjang (fermented soybean paste) in Korea. Journal of Sensory Studies 2018, 33(6), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechman, A.; Phillips, R.D.; Chen, J. Changes in Selected Physical Property and Enzyme Activity of Rice and Barley Koji during Fermentation and Storage. Journal of Food Science 2012, 77(6), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshavath, N.N.; Mukherjee, G.; Goud, V.V.; Veeranki, V.D.; Sastri, C.V. Pitfalls in the 3, 5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) assay for the reducing sugars: Interference of furfural and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 156(8), 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamura, N.; Jo, S.; Kuroda, M.; Kouda, T. Flavour improvement of reduced-fat peanut butter by addition of a kokumi peptide, γ-glutamyl-valyl-glycine. Flavour 2015, 4(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, M.; Kato, Y.; Yamazaki, J.; Kai, Y.; Mizukoshi, T.; Miyano, H.; Eto, Y. Determination and quantification of the kokumi peptide, γ-glutamyl-valyl-glycine, in commercial soy sauces. Food Chemistry 2013, 141(2), 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ThermoFisher Scientific. 2016. TraceFinder Software. Waltham, MA, USA.

- Feng, T.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Song, S.; Zhuang, H.; Xu, Z.; Yao, L.; Sun, M. Purification, identification, and sensory evaluation of kokumi peptides from agaricus bisporus mushroom. Foods 2019, 8(2), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deba-Rementeria, S.; Zugazua-Ganado, M.; Estrada, O.; Regefalk, J.; Vázquez-Araújo, L. Characterization of salt-preserved orange peel using physico-chemical, microbiological, and sensory analyses. Lwt 2021, 148(5), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumivero. 2022. XLSTAT statistical and data analysis solution. Denver, CO. Retrieved from https://www.xlstat.com/en/.

- Team, Rs. 2022. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio. Boston, MA. Retrieved from http://www.rstudio.com/.

- Wang, H.; Suo, R.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, J. Kokumi γ-glutamyl peptides: Some insight into their evaluation and detection, biosynthetic pathways, contribution and changes in food processing. Food Chemistry Advances 2022, 1(7), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano-enzyme. 2021. How the Amano-style Koji-Making Process Changed Microbial Enzymes for Food Industry. Retrieved October 23, 2023. from https://www.amano-enzyme.com/uk/introduction-to-the-amano-style-aerated-koji-making-process/.

- Chancharoonpong, C.; Hsieh, P.C.; Sheu, S.C. Effect of Different Combinations of Soybean and Wheat Bran on Enzyme Production from Aspergillus oryzae S. APCBEE Procedia 2012, 2(4), 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumoto, K.I.; Yamagata, Y.; Tazawa, R.; Kitagawa, M.; Kato, T.; Isobe, K.; Kashiwagi, Y. Japanese traditional miso and Koji making. Journal of Fungi 2021, 7(7), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakadai, T.; Nasuno, S. Enzyme preparation from extract of wheat bran koji by alcohol precipitation. Journal of Fermentation and Bioengineering 1989, 67(4), 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofyanovich, O.A.; Nishiuchi, H.; Yamagishi, K.; Matrosova, E.V.; Serebrianyi, V. Multiple pathways for the formation of the γ-glutamyl peptides γ-glutamyl-valine and γ-glutamyl-valyl-glycine in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS ONE 2019, 14(5), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, S.; Majumder, K. Comprehensive Review of γ-Glutamyl Peptides (γ-GPs) and Their Effect on Inflammation Concerning Cardiovascular Health. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2022, 70(6), 7851–7870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egg, P.C. 2023; Safety of Fermented Foods.

- Saini, M.; Kashyap, A.; Bindal, S.; Saini, K.; Gupta, R. Bacterial Gamma-Glutamyl Transpeptidase, an Emerging Biocatalyst: Insights Into Structure–Function Relationship and Its Biotechnological Applications. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12(4), 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zhou, B.; Zhao, J.; Liao, S.; Han, J.; Fang, J.; Liu, P.; Ding, W.; Che, Z.; Xu, M. Insight into the protein degradation during the broad bean fermentation process. Food Science and Nutrition 2022, 10(8), 2760–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Gänzle, M.G. Characterization of γ-glutamyl cysteine ligases from Limosilactobacillus reuteri producing kokumi-active γ-glutamyl dipeptides. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2021, 105(13), 5503–5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tamura, T.; Kyouno, N.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Akiyama, Y.; Yu Chen, J. Effect of the Chemical Composition of Miso (Japanese Fermented Soybean Paste) Upon the Sensory Evaluation. Analytical Letters 2021, 52(11), 1813–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, R.D.; Fibri DL, N.; Handoko, D.D.; David, W.; Budijanto, S.; Shirakawa, H.; Ardiansyah. The Volatile Compounds and Aroma Description in Various Rhizopus oligosporus Solid-State Fermented and Nonfermented Rice Bran. Fermentation 2022, 8(120), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, J. Efficient Synthesis of Phenylacetate and 2-Phenylethanol by Modular Cascade Biocatalysis. ChemBioChem 2020, 21(8), 2676–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q.; Imamura, M.; Katayama, H.; Obata, A.; Sugawara, E. Key compounds contributing to the fruity aroma characterization in Japanese raw soy sauce. Bioscience, Biotechnology and Biochemistry 2017, 81(10), 1984–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortzfeld, F.B.; Hashem, C.; Vranková, K.; Winkler, M.; Rudroff, F. Pyrazines: Synthesis and Industrial Application of these Valuable Flavor and Fragrance Compounds. Biotechnology Journal 2020, 15(11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Ma, X.; Wang, W.; Xu, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y. Characterization of flavor fingerprinting of red sufu during fermentation and the comparison of volatiles of typical products. Food Science and Human Wellness 2019, 8(4), 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galata, M.; Mahmoud, S. Bioactive plant isoprenoids: Biosynthetic and biotechnological approaches. Studies in Natural Products Chemistry 2012. (Vol. 37, pp. 135–171). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorell, N.; Martí, M.P.; Mestres, M.; Busto, O.; Guasch, J. Determination of 4-ethylguaiacol and 4-ethylphenol in red wines using headspace-solid-phase microextraction-gas chromatography. Journal of Chromatography A 2002, 975(2), 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, A.N.; Tan, Z.W.; Shi, B.A. Influence of the pH on the formation of pyrazine compounds by the Maillard reaction of L-ascobic acid with acidic, basic and neutral amino acids. Asia-Pacific Journal of Chemical Engineering 2011, 7(7), 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, A.; Ohshima, T. Dynamics of Aroma-Active Volatiles in Miso Prepared from Lizardfish Meat and Soy during Fermentation: A Comparative Analysis. International Journal of Nutrition and Food Sciences 2012, 1(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooding, S.P.; Ramirez, V.A.; Behrens, M. Bitter taste receptors, Genes, evolution and health. Evolution, Medicine and Public Health 2021, 9(1), 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshtaghian, H.; Bolton, K.; Rousta, K. Challenges for upcycled foods: Definition, inclusion in the food waste management hierarchy and public acceptability. Foods 2021, 10(11), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohsu, T.; Amino, Y.; Nagasaki, H.; Yamanaka, T.; Takeshita, S.; Hatanaka, T.; Maruyama, Y.; Miyamura, N.; Eto, Y. Involvement of the calcium-sensing receptor in human taste perception. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285(2), 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, M.J.; Hayes, J.E. Regional variation of bitter taste and aftertaste in humans. Chemical Senses 2019, 44(9), 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample code | Koji substrate | Miso substrate | A. oryzae strain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barley S1/BSG | Barley | BSG | S1 |

| Wheat bran S2/barley | Wheat bran | Barley | S2 |

| Wheat bran S1/barley | Wheat bran | Barley | S1 |

| Wheat bran S1/BSG | Wheat bran | BSG | S1 |

| Sample | Bitterness intensity |

Aftertaste intensity |

Thickness intensity |

Coating intensity |

| Control | 59.00 ab | 43.350ab | 35.52 a | 40.45 a |

| Miso Barley S1/BSG | 47.10 c | 37.87 b | 29.95 a | 32.72 a |

| Miso wheat bran S2/ barley | 60.45 a | 50.62 a | 36.53 a | 36.93 a |

| Miso wheat bran S1/ barley | 48.75 bc | 44.27 ab | 36.07 a | 38.22 a |

| p-value | 0.003 | 0.042 | 0.339 | 0.360 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).