Submitted:

31 October 2023

Posted:

01 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

HIGHLIGHTS

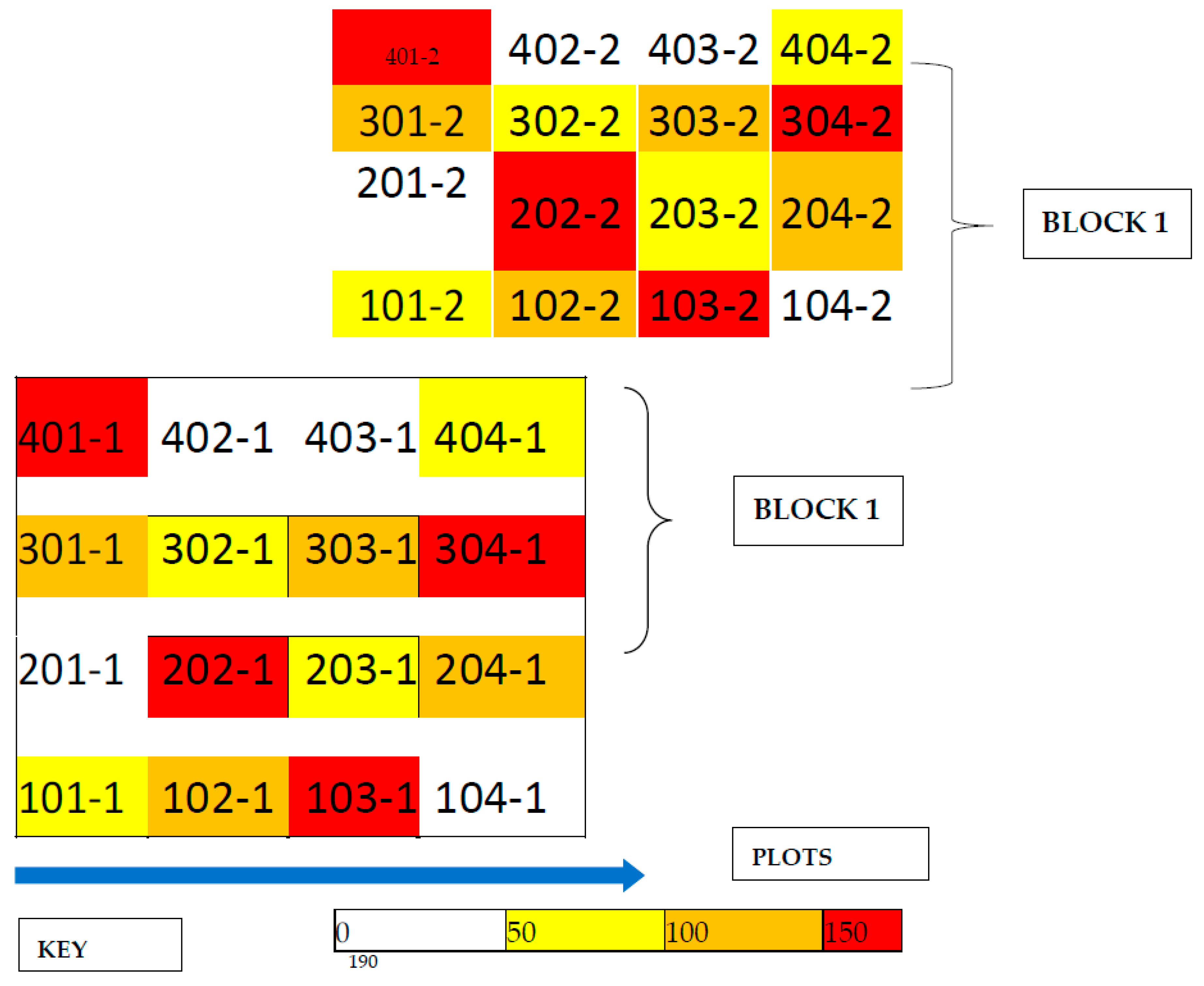

- Using conventional techniques, similar white maize seeds (Pioneer Hybrid: P1120WYHR) were planted with a planting depth of 1.5 cm and a row spacing of 30-inches (2.5 feet). Using a broadcast method, four rates of nitrogen application (0, 50, 100, and 150 kg N ha-1) were applied to each plot in the form of Granular Urea (46-0-0). The white maize seedlings were planted and were reliant only on precipitation. The plots were kept free of weeds through regular weeding.

- The plant population was estimated at 35,000 plants/acre, determined by counting the plants in a row multiplied by four. The Yield estimates were determined by the Yield Component Method.

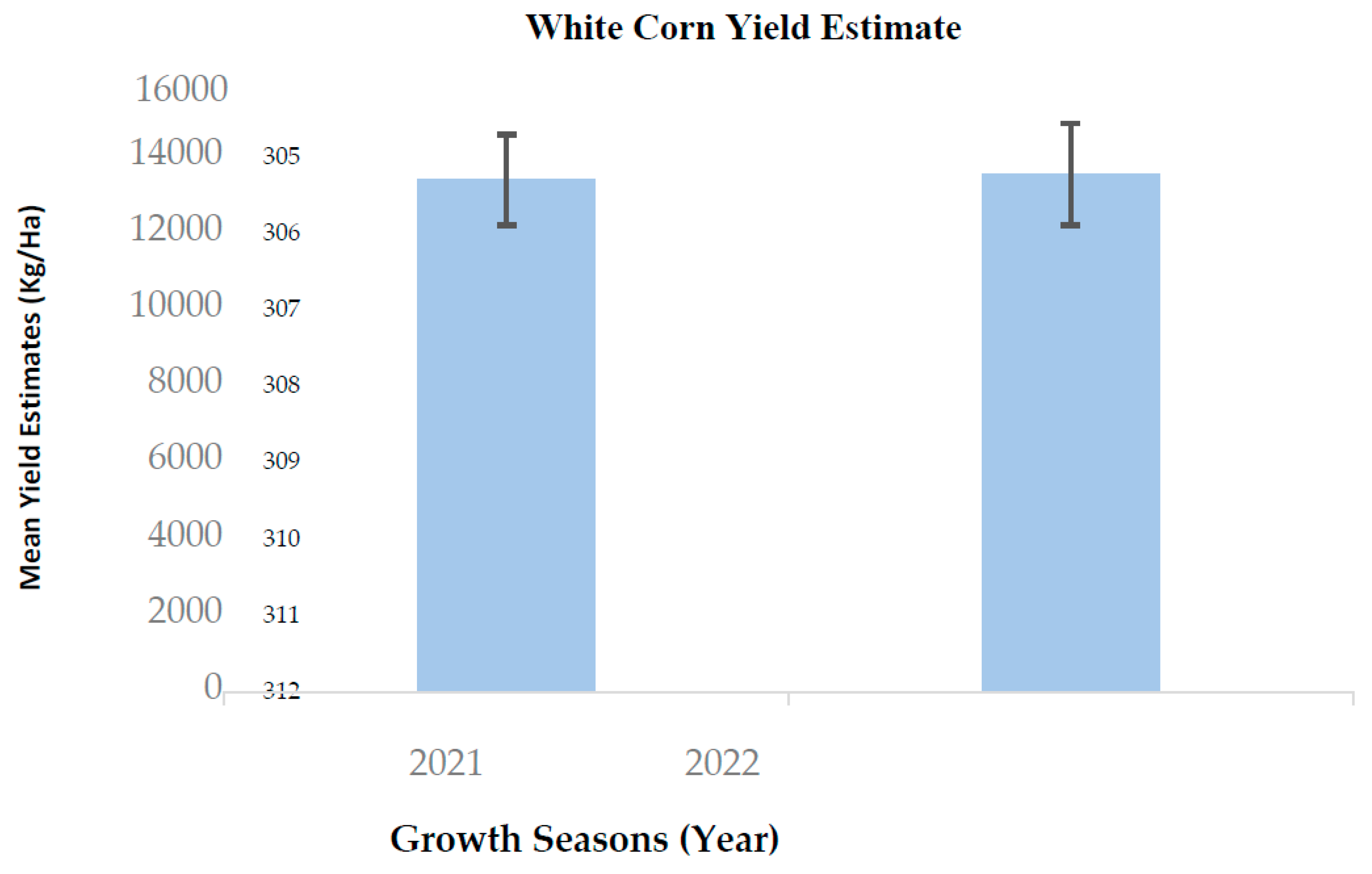

- The yield estimates and grain yields were slightly higher in 2022 than in 2021 (Figure 4.1 & 4.2). In 2021, the mean yield estimate was 12,552 Kg ha-1, while that of 2022 averaged 12687 Kg ha-1. Similarly, the grain yield achieved in 2022 was 844.1kg more than the average grain yield in 2021.

- Yield characteristics showed a positive response to nitrogen application in both seasons, whereby, there was a linear increase in yield with an increase in nitrogen

INTRODUCTION

2. METHODOLOGY

| Cultural Practice | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Site Coordinates | 40.66844 N, 88.77591 W | 40.6710 N, 88.77178 W |

| Planting dates | 2nd June 2021 | 16th May 2022 |

| Fertilizer Application dates | 13th June 2021 | 31st May 2022 |

| Mowing & regular weeding | 2nd July 2021 2nd August 2021 2nd September 2021 |

15th June 2022 15th July 2022 15th August 2022 |

| Corn sugar sampling | 9th – 15th September 2021 | 10th – 15th July 2021 |

| Harvesting dates | 15th October 2021 | 30th September 2022 |

2.1. White Corn Yield Estimate

2.2. White Corn Grain Yield

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

| Month | Temperature (°F) 2021 | Rainfall 2021 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Average | Low Average | Ppt (inches) | Ppt (mm) | |

| May | 76.25 | 43.13 | 1.41 | 35.81 |

| June | 82.00 | 64.13 | 4.32 | 109.73 |

| July | 80.38 | 64.17 | 1.41 | 35.81 |

| August | 83.11 | 66.63 | 1.89 | 48.01 |

| September | 76.58 | 57.27 | 0.84 | 21.34 |

| October | 74.42 | 45.71 | 2.58 | 65.53 |

| November | 53.63 | 24.67 | 0.3 | 7.62 |

| Month | Temperature (°F) 2022 | Rainfall 2022 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Average | Low Average | Ppt (inches) | Ppt (mm) | |

| May | 81.19 | 48.87 | 0.87 | 22.10 |

| June | 86.08 | 63.33 | 2.44 | 61.98 |

| July | 85.79 | 69.22 | 0.71 | 18.03 |

| August | 80.00 | 65.56 | 0.77 | 19.56 |

| September | 78.29 | 50.12 | 0.24 | 6.10 |

| October | 61.80 | 39.00 | 0.72 | 18.29 |

3.1. Corn Yield Estimate and Grain Yields

| Variables | N treatment | Block 1 | Block 2 | Blocks 1 & 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Std. Dev | Mean | Std. Dev | N | Mean | Std. Dev | ||

| 2021 | |||||||||

| Yield estimate (Kg ha-1) | 0 kg Nha-1 | 4 | 11240.94 | 537.99 | 11298.95 | 175.92 | 8 | 11269.95 | 371.84 |

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 4 | 12125.68 | 352.07 | 11755.52 | 552.48 | 8 | 11940.60 | 472.32 | |

| 100 kg Nha-1 | 4 | 13042.63 | 349.95 | 13104.82 | 307.95 | 8 | 13073.73 | 306.97 | |

| 150 kg Nha-1 | 4 | 13798.99 | 194.55 | 14048.44 | 598.99 | 8 | 13923.71 | 433.32 | |

| Grain yield (Kg ha-1) | 0 kg Nha-1 | 4 | 11954.99 | 1298.77 | 11746.42 | 1499.23 | 8 | 11850.70 | 1303.32 |

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 4 | 13275.13 | 495.26 | 13017.86 | 240.61 | 8 | 13146.49 | 385.80 | |

| 100 kg Nha-1 | 4 | 14387.00 | 209.70 | 14354.28 | 689.77 | 8 | 14370.64 | 472.29 | |

| 150 kg Nha-1 | 4 | 15382.80 | 1337.83 | 15512.51 | 410.81 | 8 | 15447.66 | 918.80 | |

| 2022 | |||||||||

| Yield estimate(Kg ha-1) | 0 kg Nha-1 | 4 | 11039.92 | 363.47 | 11216.03 | 443.66 | 8 | 11127.98 | 387.09 |

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 4 | 12046.55 | 563.67 | 12151.63 | 322.36 | 8 | 12099.09 | 428.79 | |

| 100 kg Nha-1 | 4 | 13578.63 | 376.01 | 13258.81 | 594.04 | 8 | 13418.72 | 490.97 | |

| 150 kg Nha-1 | 4 | 14167.06 | 680.23 | 14037.29 | 598.88 | 8 | 14102.17 | 597.35 | |

| Grain yield(Kg ha-1) | 0 kg Nha-1 | 4 | 13097.40 | 1512.23 | 12292.20 | 836.34 | 8 | 12694.80 | 1210.41 |

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 4 | 14452.90 | 1580.30 | 13943.42 | 775.84 | 8 | 14198.16 | 1184.24 | |

| 100 kg Nha-1 | 4 | 15646.59 | 610.13 | 14911.90 | 1319.73 | 8 | 15279.25 | 1029.66 | |

| 150 kg Nha-1 | 4 | 16512.64 | 2448.93 | 15526.74 | 2229.14 | 8 | 16019.69 | 2231.04 | |

| Variables | ANOVA | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Blocks 1 & 2 | Block 1 | Block 2 | |

| Yield estimate (Kg/ha) |

F3, 28 = 69.159, p < 0.001 |

F3, 12 = 34.362, p < 0.001 |

F3, 12 = 32.072, p < 0.001 |

| Grain yield (Kg/ha) |

F3, 28 = 26.46, p < 0.001 |

F3, 12 = 9.233, p = 0.002 |

F3, 12 = 14.441, p < 0.001 |

| Variables | ANOVA | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Blocks 1 & 2 | Block 1 | Block 2 | |

| Yield estimate (Kg/ha) |

F3, 28 = 60.849, p < 0.001 |

F3, 12 = 30.903, p < 0.001 |

F3, 12 = 24.229, p < 0.001 |

| Grain mass (Kg/ha) |

F3, 28 = 7.495, p = 0.001 |

F3, 12 = 3.158, p = 0.064* |

F3, 12 = 3.973, p = 0.035 |

4. CONCLUSION

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

APPENDIX I. MULTIPLE COMPARISONS/TUKEY POST HOC TESTS RESULTS TABLES

| Dependent Variable | (I) N treatment | (J) N treatment | Mean Difference (I-J) | Std. Error | Sig. | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| Brix % 60th day (8/25/2021) | 0 kg Nha-1 | 100 kg Nha-1 | .5000-1* | 0.373 | 0.002 | -2.519 | -0.481 |

| 150 kg Nha-1 | -2.719* | 0.373 | 0 | -3.738 | .699-1 | ||

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 150 kg Nha-1 | -2.156* | 0.373 | 0 | -3.175 | .137-1 | |

| 100 kg Nha-1 | 0 kg Nha-1 | 1.500* | 0.373 | 0.002 | 0.481 | 2.519 | |

| 150 kg Nha-1 | .219-1* | 0.373 | 0.014 | -2.238 | -0.199 | ||

| 150 kg Nha-1 | 0 kg Nha-1 | 2.719* | 0.373 | 0 | 1.699 | 3.739 | |

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 2.156* | 0.373 | 0 | 1.137 | 3.175 | ||

| 100 kg Nha-1 | 1.219* | 0.373 | 0.014 | 0.199 | 2.238 | ||

| Brix % 64th day (8/30/2021) | 0 kg Nha-1 | 100 kg Nha-1 | .531-1* | 0.321 | 0 | -2.408 | -0.655 |

| 150 kg Nha-1 | -2.000* | 0.321 | 0 | -2.876 | .1236-1 | ||

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 100 kg Nha-1 | .406-1* | 0.321 | 0.001 | -2.283 | -0.529 | |

| 150 kg Nha-1 | .875-1* | 0.321 | 0 | -2.751 | -0.999 | ||

| 100 kg Nha-1 | 0 kg Nha-1 | 1.531* | 0.321 | 0 | 0.655 | 2.408 | |

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 1.406* | 0.321 | 0.001 | 0.530 | 2.2826 | ||

| 150 kg Nha-1 | 0 kg Nha-1 | 2.000* | 0.321 | 0 | 1.124 | 2.8764 | |

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 1.875* | 0.321 | 0 | 0.999 | 2.7514 | ||

| Yield estimate Kg/ha | 0 kg Nha-1 | 50 kg Nha-1 | -670.650* | 200.523 | 0.012 | 218.14-1 | 23.16-1 |

| 100 kg Nha-1 | 803.783-1* | 200.523 | 0 | -2351.27 | 256.29-1 | ||

| 150 kg Nha-1 | -2653.765* | 200.523 | 0 | -3201.26 | -2106.28 | ||

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 0 kg Nha-1 | 670.650* | 200.523 | 0.012 | 123.16 | 1218.14 | |

| 100 kg Nha-1 | 133.133-1* | 200.523 | 0 | 680.62-1 | -585.642 | ||

| 150 kg Nha-1 | 983.115-1* | 200.523 | 0 | -2530.61 | -435.63 | ||

| 100 kg Nha-1 | 0 kg Nha-1 | 1803.783* | 200.523 | 0 | 1256.292 | 2351.273 | |

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 1133.133* | 200.523 | 0 | 585.642 | 1680.623 | ||

| 150 kg Nha-1 | -849.983* | 200.523 | 0.001 | 397.47-1 | -302.492 | ||

| 150 kg Nha-1 | 0 kg Nha-1 | 2653.765* | 200.523 | 0 | 2106.275 | 3201.255 | |

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 1983.115* | 200.523 | 0 | 1435.625 | 2530.605 | ||

| 100 kg Nha-1 | 849.983* | 200.523 | 0.001 | 302.492 | 1397.473 | ||

| Grain Yield Kg/ha | 0 kg Nha-1 | 50 kg Nha-1 | 295.790-1* | 426.814 | 0.025 | -2461.13 | 30.453-1 |

| 100 kg Nha-1 | -2519.936* | 426.815 | 0 | -3685.27 | 354.6-1 | ||

| 150 kg Nha-1 | -3596.956* | 426.815 | 0 | -4762.29 | -2431.62 | ||

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 0 kg Nha-1 | 1295.790* | 426.815 | 0.025 | 130.453 | 2461.127 | |

| 100 kg Nha-1 | 224.146-1* | 426.815 | 0.037 | -2389.48 | -58.809 | ||

| 150 kg Nha-1 | -2301.166* | 426.815 | 0 | -3466.5 | 135.83-1 | ||

| 100 kg Nha-1 | 0 kg Nha-1 | 2519.936* | 426.815 | 0 | 1354.599 | 3685.274 | |

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 1224.146* | 426.815 | 0.037 | 58.809 | 2389.484 | ||

| 150 kg Nha-1 | 0 kg Nha-1 | 3596.956* | 426.815 | 0 | 2431.619 | 4762.294 | |

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 2301.166* | 426.815 | 0 | 1135.829 | 3466.504 | ||

| Dependent Variable | (I) N treatment | (J) N treatment | Mean Difference (I- J) | Std. Error | Sig. | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| Brix 60th day (8/12/2022) | 0 kg Nha-1 | 150 kg Nha-1 | -3.006* | 0.608 | 0 | -4.667 | .3451-1 |

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 150 kg Nha-1 | -3.250* | 0.608 | 0 | -4.911 | .5888-1 | |

| 150 kg Nha-1 | 0 kg Nha-1 | 3.006* | 0.608 | 0 | 1.345 | 4.6674 | |

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 3.250* | 0.608 | 0 | 1.589 | 4.9112 | ||

| Brix 64th day (8/15/2022) | 0 kg Nha-1 | 150 kg Nha-1 | -2.594* | 0.628 | 0.002 | -4.310 | -0.878 |

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 150 kg Nha-1 | -2.969* | 0.628 | 0 | -4.685 | .253-1 | |

| 100 kg Nha-1 | 150 kg Nha-1 | .844-1* | 0.628 | 0.032 | -3.560 | -0.128 | |

| 150 kg Nha-1 | 0 kg Nha-1 | 2.594* | 0.628 | 0.002 | 0.878 | 4.3095 | |

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 2.969* | 0.628 | 0 | 1.253 | 4.6845 | ||

| 100 kg Nha-1 | 1.844* | 0.628 | 0.032 | 0.128 | 3.5595 | ||

| Brix 67th day (8/19/2022) | 0 kg Nha-1 | 150 kg Nha-1 | -2.750* | 0.663 | 0.002 | -4.561 | -0.939 |

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 150 kg Nha-1 | -2.844* | 0.663 | 0.001 | -4.655 | .0328-1 | |

| 150 kg Nha-1 | 0 kg Nha-1 | 2.750* | 0.663 | 0.002 | 0.939 | 4.561 | |

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 2.844* | 0.663 | 0.001 | 1.033 | 4.6547 | ||

| Yield estimate Kg/ha | 0 kg Nha-1 | 50 kg Nha-1 | -971.113* | 241.296 | 0.002 | 629.93-1 | -312.299 |

| 100 kg Nha-1 | -2290.743* | 241.296 | 0 | -2949.56 | 631.93-1 | ||

| 150 kg Nha-1 | -2974.196* | 241.296 | 0 | -3633.01 | -2315.38 | ||

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 0 kg Nha-1 | 971.113* | 241.296 | 0.002 | 312.299 | 1629.926 | |

| 100 kg Nha-1 | 319.630-1* | 241.296 | 0 | 978.44-1 | -660.817 | ||

| 150 kg Nha-1 | -2003.084* | 241.296 | 0 | -2661.9 | 344.27-1 | ||

| 100 kg Nha-1 | 0 kg Nha-1 | 2290.743* | 241.296 | 0 | 1631.929 | 2949.556 | |

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 1319.630* | 241.296 | 0 | 660.817 | 1978.443 | ||

| 150 kg Nha-1 | -683.454* | 241.296 | 0.04 | 342.27-1 | -24.641 | ||

| 150 kg Nha-1 | 0 kg Nha-1 | 2974.196* | 241.296 | 0 | 2315.383 | 3633.009 | |

| 50 kg Nha-1 | 2003.084* | 241.296 | 0 | 1344.271 | 2661.897 | ||

| 100 kg Nha-1 | 683.454* | 241.296 | 0.04 | 24.641 | 1342.267 | ||

| Grain Yield Kg/ha | 0 kg Nha-1 | 100 kg Nha-1 | - 2584.450* | 746.042 | 0.009 | -4621.38 | -547.523 |

| 150 kg Nha-1 | -3324.890* | 746.042 | 0.001 | -5361.82 | 287.96-1 | ||

| 100 kg Nha-1 | 0 kg Nha-1 | 2584.450* | 746.042 | 0.009 | 547.523 | 4621.378 | |

| 150 kg Nha-1 | 0 kg Nha-1 | 3324.890* | 746.042 | 0.001 | 1287.963 | 5361.818 | |

ANNEX II. WHITE CORN YIELD & SUGAR CHARACTERISTICS

| Variables | Block | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | ||||||

| Yield estimate (Kg ha-1) | Blocks 1 & 2 average | 32 | 10451.70 | 14760.50 | 12551.99 | 1105.32 |

| Block 1 | 16 | 10451.70 | 14024.70 | 12552.06 | 1049.01 | |

| Block 2 | 16 | 11103.90 | 14760.50 | 12551.93 | 1193.52 | |

| Grain Yield (Kg ha-1) | Blocks 1 & 2 average | 32 | 9655.62 | 17336.93 | 13703.87 | 1588.72 |

| Block 1 | 16 | 10271.30 | 17336.93 | 13749.98 | 1578.50 | |

| Block 2 | 16 | 9655.62 | 16055.85 | 13657.76 | 1649.29 | |

| 2022 | ||||||

|

Yield estimate (Kg ha-1) |

Blocks 1 & 2 average | 32 | 10660.70 | 14922.90 | 12686.99 | 1257.69 |

| Block 1 | 16 | 10660.70 | 14922.90 | 12708.04 | 1356.20 | |

| Block 2 | 16 | 10660.70 | 14760.50 | 12665.94 | 1195.33 | |

|

Grain Yield (Kg ha-1) |

Blocks 1 & 2 average | 32 | 11433.69 | 19193.86 | 14547.97 | 1904.12 |

| Block 1 | 16 | 11677.59 | 19193.86 | 14927.38 | 1997.97 | |

| Block 2 | 16 | 11433.69 | 17360.41 | 14168.57 | 1787.19 |

ANNEX III. PICTORIAL ILLUSTRATION ON THE METHODS & MATERIALS

References

- Alexandratos, N., & Bruinsma, J. (2012). World agriculture towards 2030/2050: the 2012 revision.

- Amer, M. W., Alhesan, J. S. A., Ibrahim, S., Qussay, G., Marshall, M., & Al-Ayed, O. S. (2021). Potential use of corn leaf waste for biofuel production in Jordan (physio-chemical study). Energy, 214, 118863.

- Caballero, B., Trugo, L. C., & Finglas, P. M. (2003). Encyclopedia of food sciences and nutrition. Academic.

- Erenstein, O., Jaleta, M., Sonder, K., Mottaleb, K., & Prasanna, B. M. (2022). Global maize production, consumption, and trade: trends and R&D implications. Food Security, 1-25.

- Fausti, S. W. (2015). The causes and unintended consequences of a paradigm shift in corn production practices. Environmental Science & Policy, 52, 41-50.

- García-Lara, S., & Serna-Saldivar, S. O. (2019). Corn history and culture. Corn, 1-18.

- Gheith, E., El-Badry, O. Z., Lamlom, S. F., Ali, H. M., Siddiqui, M. H., Ghareeb, R. Y., El-Sheikh, M. H., Jebril, J., Abdelsalam, N. R., & Kandil, E. E. (2022). Maize (Zea mays L.) Productivity and Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Response to Nitrogen Application Levels and Time. Frontiers in plant science, 13, 941343.

- Helstad, S. (2019). Corn Sweeteners. In Corn (pp. 551-591). AACC International Press.

- Jafarikouhini, N., Kazemeini, S. A., & Sinclair, T. R. (2020). Sweet Corn Ontogeny in Response to Irrigation and Nitrogen Fertilization. Journal of Horticulture and Plant Research, 23.

- Jusoh, N., Ahmad, A., & Tengah, R. Y. (2019). Evaluation of nutritive values and consumer acceptance of sweet corn (Zea mays) juice as a recovery beverage for exercising people. Malays. J. Fundam. Appl. Sci, 15, 504-507.

- Khanduri, A., Hossain, F., Lakhera, P. C., & Prasanna, B. M. (2011). Effect of harvest time on kernel sugar concentration in sweet corn. Indian Journal of Genetics and Plant Breeding, 71(3), 231.

- Lao, Y. X., Yu, Y. Y., Li, G. K., Chen, S. Y., Li, W., Xing, X. P., & Guo, X. B. (2019). Effect of Sweet Corn Residue on Micronutrient Fortification in Baked Cakes. Foods, 8(7), 260.

- Malvar, R. A., Revilla, P., Moreno-González, J., Butrón, A., Sotelo, J., & Ordás, A. (2008).

- White maize: genetics of quality and agronomic performance. Crop science, 48(4), 1373-1381.

- Manjunatha, S. B., Biradar, D. P., & Aladakatti, Y. R. (2016). Nanotechnology and its applications in agriculture: A review. Journal of farm Science, 29(1), 1-13.

- Merrill, W. L., Hard, R. J., Mabry, J. B., Fritz, G. J., Adams, K. R., Roney, J. R., & MacWilliams, A.C. (2009). The diffusion of maize to the southwestern United States and its impact. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(50), 21019-21026.

- Ohyama, T. (2010). Nitrogen as a major essential element of plants. Nitrogen assimilation in plants, 37(2), 2-17.

- Omar, S., Abd Ghani, R., Khaeim, H., Sghaier, A.H., & Jolánkai, M. (2022). The effect of nitrogen fertilisation on yield and quality of maize (Zea mays L.). Acta Alimentaria, 51(2). [CrossRef]

- Pan-in, S., & Sukasem, N. (2017). Methane production potential from anaerobic co-digestions of different animal dungs and sweet corn residuals. Energy Procedia, 138, 943-948.

- Pruitt, J. D. (2016). A brief history of corn: looking back to move forward. The University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- Ranum, P., Peña-Rosas, J. P., & Garcia-Casal, M. N. (2014). Global maize production, utilization, and consumption. Annals of the New York academy of sciences, 1312(1), 105-112.

- Ray, D. K., Ramankutty, N., Mueller, N. D., West, P. C., & Foley, J. A. (2012). Recent patterns of crop yield growth and stagnation. Nature communications, 3(1), 1-7.

- Ray, K., Banerjee, H., Dutta, S., Hazra, A. K., & Majumdar, K. (2019). Macronutrients influence yield and oil quality of hybrid maize (Zea mays L.). PloS one, 14(5), e0216939. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V. R., Seshu, G., Jabeen, F., & Rao, A. S. (2012). Speciality corn types with reference to quality protein Maize (Zea mays L.)-A review. International Journal of Agriculture, Environment and Biotechnology, 5(4), 393-400.

- Revilla, P., Anibas, C. M., & Tracy, W. F. (2021). Sweet corn research around the world 2015–2020. Agronomy, 11(3), 534.

- Rooney, L. W. (1991). Chapter 13: Food uses of whole corn and drymilled fractions. Corn: Chemistry and Technology, 399-429.

- Rose, D. J., Inglett, G. E., & Liu, S. X. (2010). Utilisation of corn (Zea mays) bran and corn fiber in the production of food components. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 90(6), 915-924.

- Sharma, A., Wuebbles, D. J., & Kotamarthi, R. (2021). The need for urban-resolving climate modeling across scales. AGU Advances, 2(1), e2020AV000271.

- Serpen, J. Y. (2012). Comparison of sugar content in bottled 100% fruit juice versus extracted juice of fresh fruit.

- Singh, I., Langyan, S., & Yadava, P. (2014). Sweet corn and corn-based sweeteners. Sugar tech, 16(2), 144-149.

- Szymanek, M., Tanaś, W., & Kassar, F. H. (2015). Kernel carbohydrates concentration in sugary- 1, sugary enhanced and shrunken sweet corn kernels. Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedia, 7, 260-264.

- Tilman, D., Fargione, J., Wolff, B., D'antonio, C., Dobson, A., Howarth, R., & Swackhamer, D. (2001).Forecasting agriculturally driven global environmental change. Science, 292(5515), 281-284.

- Wallington, T. J., Anderson, J. E., Mueller, S. A., Kolinski Morris, E., Winkler, S. L., Ginder, J.M., & Nielsen, O. J. (2012). Corn ethanol production, food exports, and indirect land use change. Environmental science & technology, 46(11), 6379-6384.

- Wang, N., Fu, F., Wang, H., Wang, P., He, S., Shao, H., Ni, Z., & Zhang, X. (2021). Effects of irrigation and nitrogen on chlorophyll content, dry matter and nitrogen accumulation in sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.). Scientific Reports 11, 16651. [CrossRef]

- White, J. S., Hobbs, L. J., & Fernandez, S. (2015). Fructose content and composition of commercial HFCS-sweetened carbonated beverages. International Journal of Obesity, 39(1), 176-182.

- Wu, Y., Zhao, B., Li, Q., Kong, F., Du, L., Zhou, F., Shi, H., Ke, Y., Liu, Q., Feng, D., & Yuan, J. (2019). Non-structural carbohydrates in maize with different nitrogen tolerance are affected by nitrogen addition. PloS one, 14(12), e0225753. [CrossRef]

- Yue, K., Li, L., Xie, J., Liu, Y., Xie, J., Anwar, S. & Fudjoe, S. K. (2022). Nitrogen supply affects yield and grain filling of maize by regulating starch metabolizing enzyme activities and endogenous hormone contents. Frontiers in Plant Science, 12, 798119. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., Ouyang, Z., Zhang, X., Wei, Y., Tang, S., Ma, Z., & Han, X. (2019). Sweet corn stalk treated with saccharomyces cerevisiae alone or in combination with lactobacillus plantarum: Nutritional composition, fermentation traits and aerobic stability. Animals, 9(9), 598.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).