1. Introduction

Aerococcus urinae and

Actinotignum schaalii are part of the urinary microbiota [

1,

2,

4], and have also been recently recognized as uropathogens in patients with certain underlying medical conditions [

1,

2,

3]. Wider use of MALDI-TOF-MS technology means it is now possible to correctly identify to the species level these bacteria, which were formerly misidentified by biochemical methods [

1,

2]. These uropathogens have probably been underestimated as disease-causing agents due to the use of outdated identification methods, but also because bacteriological laboratories do not always use apprioriate culture methods to isolate these slow-growing bacteria [

2]. To our knowledge, pyelonephritis caused by both

A. schaalii and

A. urinae has been previously described only once, in a 78-year-old man presenting urinary incontinence [

5]. We report here the second case in an 89-year-old woman who was successfully treated with amoxicillin acting on both bacteria.

2. Case report

An 89-year-old woman was taken to the emergency ward of our university hospital from her nursing home with persistent drowsiness and dyspnea. Her medical history included non-insulin-dependent diabetes, hypothyroidism and cognitive impairment. On physical examination, the patient was drowsy but arousable, and had a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15. Body temperature was 37.9 °C. The patient was tachypneic with a respiratory rate of 23 breaths/min, oxygen saturation was 86% on oxygen 3 L/min, and she had a quickSOFA score of one. Pulmonary auscultation revealed crackles in the left lower lung. Inflammatory markers showed elevated C-reactive protein (139 mg/L), but no leukocytosis (leukocyte count: 9.6 x 109/L). Urine dipstick showed traces of leukocytes and blood 3+, but no nitrites. A midstream urine sample was drawn for microbiological analysis, but no blood cultures were taken. SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza tests were negative. Brain tomodensitometry showed no signs of cerebral hemorrhage. A chest X-ray showed bilateral perihilar infiltrates, and therefore lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) was first suspected, so she was given empiric antibiotherapy with 1g of intravenous amoxicillin/clavulanic acid in the emergency ward. She was promptly transferred to the geriatric department where two sets of blood cultures were finally drawn. The next day, urinalysis revealed 210 leukocytes/µL (iQ 2000, Beckman Coulter, France). In light of these first urinary results and the chest computed tomography results, the LRTI diagnosis was reconsidered and she was switched from amoxicillin/clavulanic acid to intravenous cefotaxime to treat a presumed urinary tract infection (UTI). As the urinary leucocyte count was >50/μL urine Gram staining was performed and showed Gram-positive cocci arranged in clusters. Urinary cultures remained sterile after 24 hours of incubation on chromogenic agar plates (Uriselect 4®; Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France), but grew 106 CFU/mL tiny alpha-hemolytic colonies after 48 hours incubation on Columbia sheep blood agar under 5% CO2 (COL-S; Becton Dickinson, Le Pont-de-Claix, France). MALDI-TOF MS of the colonies using a MicroFlexLT device and the BIOTYPER database (Bruker Daltonics, Wissembourg, France) successfully identified A. urinae (log score >2). The antibiotic treatment was therefore changed to 1g oral amoxicillin t.i.d. The same day, the two anaerobic blood culture bottles (BCBs) incubated in a BacT/ALERT® 3D system (BioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) flagged positive after incubation for 52 and 63 h, respectively. Aerobic BCBs were negative. Gram staining of the positive BCBs revealed Gram-positive cocci arranged in clusters and slightly curved Gram-positive rods. .

MALDI-TOF identification from the positive BCBs, as previously described [

6], failed on the first one, but matched with

A. urinae with a maximum log score of 1.4 (and four times repeatable) on the second. Amoxicillin treatment was adjusted to 2g t.i.d. for ten days for acute pyelonephritis associated with bacteremia. The two positive BCBs were subcultured on blood agar plates, and both grew

A. urinae and

A. schaalii after 48 hours of anaerobic incubation. We used E-test strips to determine antibiotic susceptibility. AST was interpreted in accordance with CASFM/EUCAST 2021 recommendations. The results are shown in

Table 1. The patient was discharged after 8 days with complete clinical and biological recovery.

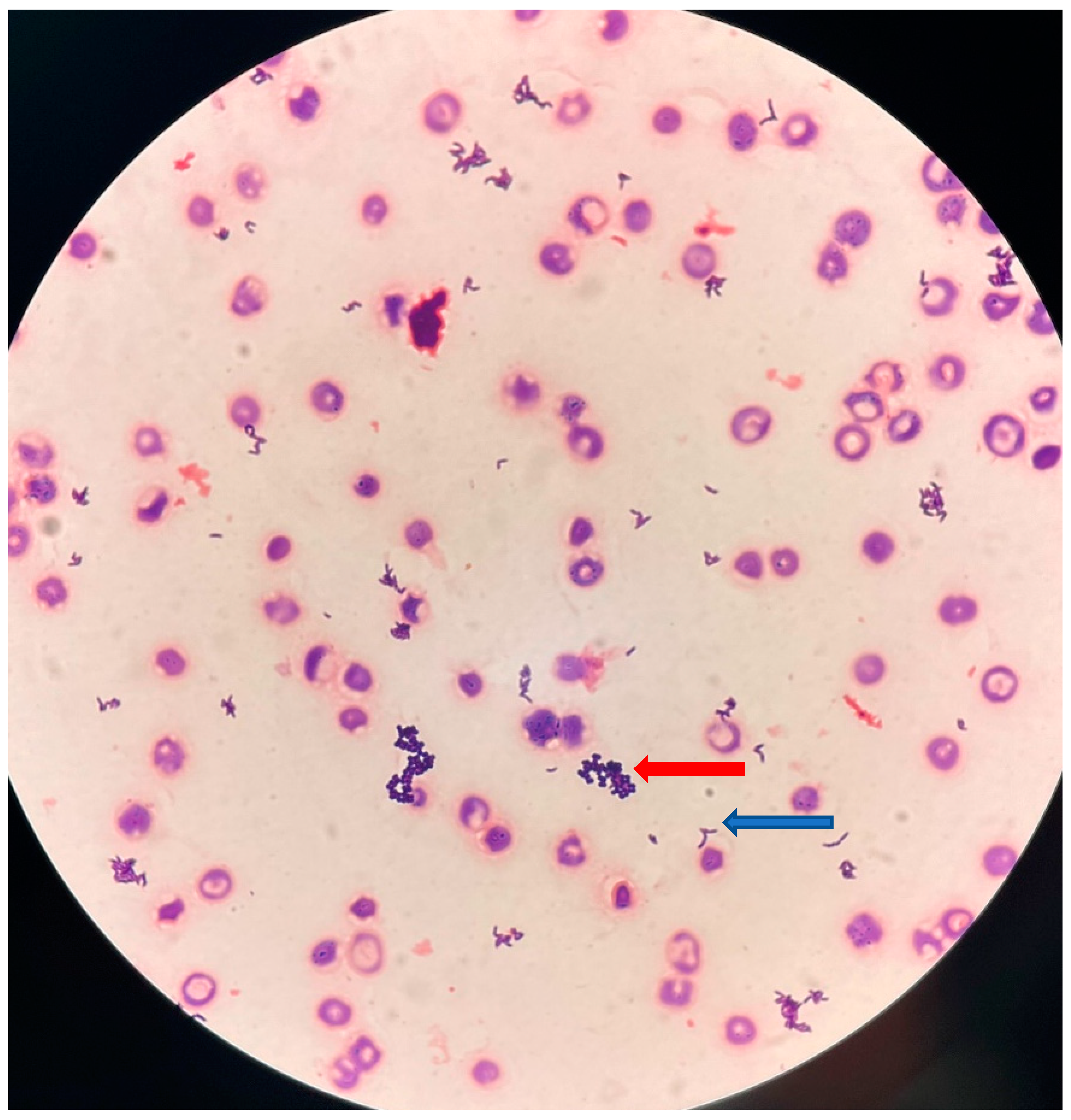

Figure 1.

Gram staining (original magnification, x500) of blood culture showing small, slightly curved, Gram-positive rods (blue arrow), and Gram-positive cocci arranged in clusters (red arrow).

Figure 1.

Gram staining (original magnification, x500) of blood culture showing small, slightly curved, Gram-positive rods (blue arrow), and Gram-positive cocci arranged in clusters (red arrow).

3. Discussion

A. urinae and

A. schaalii are part of the urinary microbiota [

1,

2,

4] and have also been recently recognized as uropathogens in patients with certain underlying medical conditions [

1,

2,

3]. Wider use of MALDI-TOF-MS technology means it is now possible to correctly identify to the species level these bacteria, which were formerly misidentified using biochemical methods:

A. schaalii as

Gardnerella vaginalis, Arcanobacterium spp.,

Actinomyces meyeri or

Actinomyces israelii, and

A. urinae as

Aerococcus viridans or

Granulicatella spp. [

1,

2]. These uropathogens have probably been underestimated as causes of disease due to the use of biochemical identification methods, but also because few bacteriological laboratories employ the enriched medium required to grow these fastidious bacteria [

2]. In our laboratory, urine culture protocols for slow-growing bacteria include culture on Columbia sheep blood agar with incubation at 37 °C under 5% CO2 (COL-S; Becton Dickinson, Le Pont-de-Claix, France), and anaerobic culture on Columbia CAP (Colistin+Aztreonam) blood agar (Oxoid) for 48 hours, in addition to the usual chromogenic agar plates (Uriselect 4®; Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France), when the Gram stain is positive and yields Gram-positive rods or cocci. Gram staining is performed when the urinary leukocyte count is >50/μL and/or bacterial count is >14/μL [

7]. In the present case, urinalysis revealed 210 leukocytes/µL and the Gram stain revealed Gram-positive cocci arranged in clusters. The leukocyturia, clinical presentation, and chest computed tomography results eventually excluded the diagnosis of LRTI and suggested pyelonephritis.

The antibiotherapy was therefore switched to intravenous cefotaxime.

A. urinae was then identified by urinary culture confirming the diagnosis of pyelonephritis, and the antibiotic treatment was changed to 1g oral amoxicillin t.i.d. as

Aerococcus species have very low MICs to aminopenicillin, making this class of antibiotics the treatment of choice against these pathogens [

1]. In contrast,

A. urinae is not consistently susceptible to the antibiotics frequently used to treat UTIs, such as fluoroquinolones (50-80%) [

1,

8], and is inherently resistant to sulfamethoxazole, which makes the action of the trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole association uncertain [

1].

A. schaalii is also consistently susceptible to aminopenicillin, and is more frequently resistant to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (60%) and second-generation quinolones (norfloxacin, ciprofloxacin) (99%) [

2]. We should point out that we were unable to isolate

A. schaalii in urine and one explanation for this could be that

A. urinae had grown over it. Another portal of entry seems unlikely considering that

A. schaalii does not seem to be part of the gut microbiota [

2] and the patient did not show any symptoms of digestive disorder. Although

A. schaalii can sometimes be involved in cellulitis and abscesses [

2], cutaneous inoculation is also unlikely because the patient did not present any skin wound. Even if,

A. schaalii was not isolated in the urine sample, the patient had several predisposing factors for UTI. Indeed, the advanced aged of the patient (89 years), the humid environment created by diapers and urinary incontinence are all common risk factors for UTI related to

A. schaalii [

2].

Interestingly, the same day

A. urinae was isolated in a urine sample and two anaerobic BCBs flagged positive. Gram staining of both BCBs showed slightly curved Gram-positive rods and Gram-positive cocci arranged in clusters. As

Corynebacteria and

Propionibacterium spp. are Gram-positive bacilli, and coagulase-negative staphylococci are Gram-positive cocci arranged in clusters, and both are frequently involved in BC contamination, our results may have been attributed to BC contamination if the previous urine Gram stain had not showed Gram-positive cocci arranged in clusters and we had not simultaneously identified

A. urinae in the urine. Our results highlight the importance of (i) Gram staining a urinary sample where urinary dipstick is negative for nitrites and is associated with leukocyturia; and (ii) using an enriched culture medium when the Gram stain shows Gram-positive rods or Gram-positive cocci. This is the major take-home message of this case. In our laboratory, we also performed direct identification on BCBs, as our team described in a previously study [

6], in which we compared direct MALDI-TOF identification from BCBs (Day0) with identification from colonies on Day1 (log (score) ≥2). We showed that using a log (score) ≥1.5 and 3 times repeatable at Day0 we were able to correctly identify 100% of the staphylococci, enterococci, beta-hemolytic streptococci,

Enterobacterales and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa. We did not test this identification protocol with any fastidious microorganisms, such as

A. urinae and

A. schaalii, because these bacteria are rarely involved in blood stream infections (BSI) [

6]. Nevertheless, in the present case, direct MALDI-TOF of one of the two anaerobic BCBs matched with

A. urinae with a log score of 1.4 (four times repeatable). Although the maximum log (score) did not reach the threshold (log (score) ≥1.5), the combination of these results (Gram stain of BCB and direct MALDI-TOF of BCB and urinary culture) reassured us that the diagnosis of bacteremia caused by

A. urinae was correct. Therefore, we immediately recommended optimizing the antibiotic dose to treat a BSI and amoxicillin was adjusted to 2g t.i.d. The tentative diagnosis of a BSI was confirmed 48 hours later as both

A. urinae and

A. schaalii grew on the BCB subcultures. The patient was discharged after 8 days having completely recovered.

4. Conclusion

Pyelonephritis caused by both A. urinae and A. schaalii is rare and has previously been described only once in an elderly man with an indwelling urinary catheter [

5]. It is therefore important that this case is reported. The case is also interesting because its diagnosis presents a challenge to routine microbiology and to clinical practice, particularly for trainees. Microbiologists should assess the presence of A. schaalii or A. urinae in cases where a positive direct examination reveals small Gram-positive rods or cocci, where undocumented UTIs are present in elderly patients with an underlying disease or urinary incontinence, but also where a urinary dipstick is negative for nitrites and is associated with leukocyturia. Identification of these uropathogens is also important because they are resistant to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and second-generation quinolones, which are widely used in the treatment of UTIs. Antimicrobial treatment with aminopenicillin is the most efficient treatment and should be recommended.

Finally, we would like to point out that our laboratory is operational 24h/7, and direct bacterial identification from BCBs allowed us to promptly diagnose an acute invasive infection, and the physician to immediately optimize the antibiotic therapy, which was crucial for the patient’s recovery.

Author Contributions

L.L. and RL conceptualized the study, contributed to data curation, analyzed the data, wrote the original version of the manuscript and take the responsibility for the accuracy of the data analysis. C.D., A.C., A.G., Y.C and R.R. contributed to the data curation and analyzed the data. RL supervised the study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by fundings from the Ministère de la Santé et de la Prévention of France: Clinical Trial MICROPROSTK 2019 (NCT03947515; ID-RCB: 2019-A00741-56) to R.L.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We also thank Tessa Say for the careful reading and editing of the manuscript. We also thank the technician’s team of the laboratory of bacteriology at Nice University Hospital for the technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rasmussen, M. Aerococcus : An Increasingly Acknowledged Human Pathogen. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2016, 22, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotte, R.; Lotte, L.; Ruimy, R. Actinotignum Schaalii (Formerly Actinobaculum Schaalii ): A Newly Recognized Pathogen—Review of the Literature. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2016, 22, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotte, R.; Durand, M.; Mbeutcha, A.; Ambrosetti, D.; Pulcini, C.; Degand, N.; Loeffler, J.; Ruimy, R.; Amiel, J. A Rare Case of Histopathological Bladder Necrosis Associated with Actinobaculum Schaalii: The Incremental Value of an Accurate Microbiological Diagnosis Using 16S rDNA Sequencing. Anaerobe 2014, 26, 46–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, H.; Nederbragt, A.J.; Lagesen, K.; Jeansson, S.L.; Jakobsen, K.S. Assessing Diversity of the Female Urine Microbiota by High Throughput Sequencing of 16S rDNA Amplicons. BMC Microbiol 2011, 11, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, P.D.J.; Van Eijk, J.; Veltman, S.; Meuleman, E.; Schülin, T. Urosepsis with Actinobaculum Schaalii and Aerococcus Urinae. J Clin Microbiol 2006, 44, 652–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, L.; Ughetto, E.; Gaudart, A.; Degand, N.; Lotte, R.; Ruimy, R. Direct Identification of 80 Percent of Bacteria from Blood Culture Bottles by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry Using a 10-Minute Extraction Protocol. J Clin Microbiol 2019, 57, e01278-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotte, L.; Lotte, R.; Durand, M.; Degand, N.; Ambrosetti, D.; Michiels, J.-F.; Amiel, J.; Cattoir, V.; Ruimy, R. Infections Related to Actinotignum Schaalii (Formerly Actinobaculum Schaalii ): A 3-Year Prospective Observational Study on 50 Cases. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2016, 22, 388–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, F.E.; Berteau, T.; Bestman-Smith, J.; Grandjean Lapierre, S.; Dufresne, S.F.; Domingo, M.-C.; Leduc, J.-M. Validation of a Gradient Diffusion Method (Etest) for Testing of Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Aerococcus Urinae to Fluoroquinolones. J Clin Microbiol 2021, 59, e00259–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).