1. Introduction

Seaweeds generate various low molecular weight organic volatiles which are essential for odor and sensory perception, and they are highly related to the physiology of seaweed species. Volatiles of seaweeds include acids, alcohols, aldehydes, esters, hydrocarbons, ketones, phenols, terpenes, halogenated and sulfur compounds are sometimes unacceptable for some consumers [

1]. Therefore, most seaweeds require to be processed (mostly drying) prior to consumption, and still remain in minor portion in the diet of Western Countries.

Dried red seaweed Gelidium amansii, J. V. Lamouroux, is the raw material of Gelidium jelly, which is a congealed product of boiling dried red seaweed in water for 1 h. The extracted agar solution is then filtered and cooled to room temperature to form Gelidium jelly. The jelly may be added into ice cold honey water as a popular beverage during summer time. The drying process of Gelidium amansii is believed requiring repeatedly washing and sun drying for seven times in days in order to obtain the best quality in tradition. New Taipei City is the main producing area of dried red seaweed in Taiwan. However, the sunshine hours (sunshine is greater than 200W/m2) are low in 1317-1430 hours/year and the annual rainfall is high between 2744 and 3590 mm/year in this area, which limited the production of dried red seaweed. The drying process starts from evenly piling red seaweed on the ground in about 1 cm seaweed mat in height. The impurities and other seaweeds are removed, and seaweed is dried under sun. The seaweed mat is rolled up in evening and then washed with water thoroughly. In the next day, the seaweed is rolled out under sun drying again, and washed with water in the evening. The drying process is repeated for 7 times in 7 days if the weather allowed. This process could remove seaweed fishy odor and turn the purple-red color into yellow. The purple-red matters of red seaweeds are susceptible to photochemical degradation under solar radiation.

Information on the volatile compounds of dried Gelidium seaweed, which contribute to its sensory profile was rare. This study investigated the volatile changes during washing and sun drying cycles of Gelidium seaweed. An alternative drying method by halogen lamp instead of sun drying was studied as well. The jelly properties and volatiles of the two drying method toward Gelidium seaweed were compared, described and discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Dried red seaweed preparation

Red seaweed Gelidium amansii (J. V. Lamouroux) was collected in March 2022 to July 2022 under low tide conditions in Gonglian district (25∘01’N and 121∘54’E) of New Taipei City, Taiwan. The fresh red seaweed was kept in freezer at -18°C until use. Five hundred grams frozen seaweed for each was sunk in running tap water until completely thawed. Then, seaweed was evenly put on a stainless mesh (18 x 10 cm, L x W) in about 1 cm thickness. The red seaweed was dried under sun for 2 h (the illuminance was around 35,000 to 50,000 lux) or dried under 300W halogen lamp (Anjia Light Store, Kaohsiung) for 2 h (the average illuminance was 15,000 to 20,000 lux). The dried red seaweed was then washed with water, stored at night, dried under sun or halogen lamp again in 3 and 7 times for sun drying, 7, 9, 12 times for halogen lamp drying, respectively. Another seaweed dried in a 50°C oven for 4 days reached moisture 10%-13% was used as control sample.

2.2. Moisture and agar content

Moisture content of dried red seaweeds were measured according to AOAC method 984.25 by an oven at 105°C. Agar content was measured by boiling 2 g of seaweed each in deionized water (200 g) for 60 min. Then the extracted agar solution was filtered, and the filtrate was lyophilized using a freeze dryer (LABCONCO 12 L, Kansas City, MO, USA). The yield of agar was expressed as % w/w on the dry basis of 2 g dried seaweed sample.

2.3. Seaweed jelly texture analysis

The above extracted agar solution each was poured into a glass beaker (diameter of 38.0 mm and height of 38.0 mm) when it is hot. The beaker was stored at 4°C overnight to form jelly. Hardness (N) and springiness (%) of jelly sample was measured using a texture analyzer (TA-XT2, Stable Micro Systems, Godalming, UK) equipped with a 4 mm diameter cylinder probe (P/0.5) (test speed: 1.0 mm/sec; target distance: 15.0 mm; trigger force: 15 g) according to the methods of Hurler et al. [

2]. Springiness was defined as the percentage (%) of the second compression force to the maximum compression force (hardness) during two compression cycle. Springiness represented the hardness of the sample at second bite. All tests were performed with 3 replicates.

2.4. Color analysis

The CIELAB color space represented to L* (lightness), a* (redness/greenness), b* (yellowness/blueness) color scale of seaweed powder was conducted with a spectrocolorimeter (TC-1800 MK-II, Tokyo Tokyo, Japan). Standardization was done with black cup and white tile (X = 79.2, Y = 80.7, Z = 90.7). The seaweed powder was loaded onto a quartz sample cup with three measurements for each sample and triplicate determinations were recorded per treatment. Color difference △E was calculated as the following formulation [(△L*)2+(△a*)2+(△b*)2]1/2; △L* = L*sample - L*fresh; △a* = a*sample - a*fresh; △b* = b* sample – b*fresh.

2.5. Rheological measurement

The dynamic viscoelastic properties of filtered agar solution were measured using a rheometer (Physica MCR 92, Anton Paar Gmblt, Ostildern, Germany) at a temperature range of 90°C to 20°C, with a decreasing temperature of 2°C/s. The filtrate of boiling dried seaweed 0.56 mL was immediately poured on the rheometer’s lower plate (PP252, which was conditioned at 90°C. The parallel plate was lowered to the solution, the measurement was initiated after thermal equilibrium was approached. Each run consisted in three steps. The first gelation step conducted at an amplitude strain of 0.5%: temperature ramp from 90°C to 20°C at a cooling rate of 2°C/s and an angular frequency of 30 rad/s. The second curing step: time sweep of 1800 s, at 20°C and an angular frequency of 30 rad/s at shear strain of 0.5%. The third mechanical spectra step: frequency sweep from 1 to 100 rad/s (ramp linear) at 20°C and 0.5% shear strain. All the rheological measurements were analyzed using the Rheoplus software (version 3.21, Anton-Paar) to generate elastic modulus (G’), viscous modulus (G”), and derived parameters. A strain amplitude sweep (from 0.01% to 100%, at 1 rad/s and 20°C) was applied immediately after each run to verify the measurement within the linear viscoelastic range [

3].

2.6. Volatiles of dried seaweed

The dried red seaweeds from different washing and drying cycles were cut into 0.5 cm pieces. A sample of 0.5 g was placed into a 20-mL headspace vail, and 12 mL water was added. Ethyl caprate 4 μL at concentration of 20 ppm in methanol was added as internal standard. The headspace vail was sealed with a teflon-lined septum and screw cap, which was conditioned at 70°C for 30 min. A 30/50 μm DVB/CAR/PDMS fiber was then inserted into the headspace vial for 30 min as absorption process. Then, the fiber was inserted into the GC injector for 5 min with splitless mode (vent time for 3 min). The injector was set at 250°C. Volatile compounds were separated and analyzed using a gas chromatograph (GC, 7890B, Agilent Tech., Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a mass spectrometer (MS, 7000C, Agilent Tech.) and a DB-5MS column (30 m × 0.23 mm, film 0.15 μm, Agilent Tech.). Helium was the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The oven temperature was kept at 40°C for 3 min and then increased to 70°C at a rate of 7°C/min. Then, the oven temperature was maintaining at 70°C for 3 min followed by further increase to 170°C at a rate of 10°C/min. and increase to 230°C at a rate of 20°C/min. The final holding was 10 min. The MS scanning range was m/z 30-450.

Volatile compounds were identified based on their retention indices (RI), which were calculated using n-alkane (C7-C30, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and matched MS spectra library (NIST 17). Semi-quantitative analysis was done by the relative area of the compounds to internal standard, ethyl caprate. The estimated odor activity values (OAVs) of selected volatiles were calculated by dividing the concentrations (semiquantitative data) with the odor thresholds (OTs) from references.

2.7. Sensory Evaluation

Sensory evaluation of Gelidium jellies made from dried seaweed by various drying methods were carried out by untrained panelists on the basis of preference tests. The panelists consisted with 37 females and 29 males in age between 19 and 85 were recruited. Attributes on appearance, color, flavor, texture, overall acceptability, and fishy odor were asked. Samples were coded with 3 random digits and supplied to the panelists in random order. Panelists were instructed to evaluate each of the above-mentioned attributes by ranking from “1 = extremely dislike” to “9 = extremely like”. A nine-point hedonic test for fishy odor (1 = no fishy smell, and 9 = strong fishy smell) was also conducted.

Statistical Analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Turkey’s tests at a 5% significance level (p < 0.05) were analyzed with the IBM SPSS statistics (Version 23.0, IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). The General Linear Model (GLM) was assessed for one-way analysis of variance in SPSS. Pearson correlation analysis was used to examine linear correlations on gel appearance, texture, hardness, color parameters, fishy odor, and overall acceptability at significance levels of p < 0.05 and p < 0.01. The semi-quantitated contents of volatiles in dried seaweeds by different washing and drying cycles were used as variables for principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA). Visualized graphs were generated by MetaboAnalyst 5.0 (

http://www.metaboanalyst.ca/). Each variable were normalized by mean-centered and divided by standard deviation.3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effects of Halogen Lamp Drying, Sun Drying, and Washing cycles on the Agar Yield and Properties

The agar yields of red seaweed by different drying processes and cycles were showed in

Table 1. The agar yields ranged from 23.0% to 46.0%. Sun drying for 7 cycles showed the best agar yield, while oven dried seaweed obtained the lowest agar yield. The main components of Gelidium seaweeds were hydrophilic polysaccharides with water surrounded in the internal and external substructure by hydrogen bonding. The washing process mainly hydrated the dried seaweeds, eased the availability of soluble polysaccharides, and removed impurities. The agar yields from native and alkali-modified extractions of the red seaweed Gracilaria lemaneiformis were reported approximately 29.7% and 25.4%, respectively [

4]. It would be influenced by various parameters such as soaking time, soaking temperature, water to seaweed ratio, boiling temperature and duration [

5]. Other pretreatments, such as acid hydrolysis and ultrasound-assisted extraction were found not only to increase the agar yield but also some valuable biomolecules at shorter process time [

6].

The qualities of agar were altered by seaweed grew in different conditions such as light availability, salinity, and seawater temperature [

7,

8]. Gelidium sp. was reported offering better agar quality in terms of gel strength compared to other species such as Gracilaria [

9]. Gracilaria species exhibited lower agar quality due to their high sulphate (L-galactose-6-sulphate) content, which could be treated with alkali and converted into 3,6-anhydro-L-galactose to increase gel strength [

5]. The agar jellies from different drying methods and cycles showed low gelling temperatures in the ranges of 26°C to 31°C, which was lower than that from G. lemaneiformis in the ranges of 40°C to 41°C [

4]. The jelly made from oven dried Gelidium seaweed (F, control) showed the lowest gelling temperature (26°C), while the gel of sun-dried seaweed with 7 times exposure under sun light offered the highest gelling temperature (

Table 1). According to the US Pharmacopoeia, the gelling temperature of commercial agar should fall between 34°C and 43°C. Agars form Gracilaria species were reported in the range of 40°C to 52°C for gelling temperature [

4]. In this study, the gelling temperature of Gelidium was found and reported a lower gelling temperature, ranged from 26°C to 31°C.

Gel hardness, an important gel texture characteristic of the consumer acceptance, was shown in

Table 1. The hardness of jelly samples was in the ranges of 0.23 N (F) to 3.54 N (S7). The jelly hardness of oven dried Gelidium seaweed (F) was lower than those of sun drying and halogen lamp drying red seaweeds. This study found that the color of red seaweed did not change (i.e., no photobleaching occurred) when subjected to 45°C and 105°C oven drying. Later, UV-C light irradiation was applied in the oven drying. However, the color of red seaweed still was still not changed. There Seemed to be full band or certain frequency band that were required for photobleaching, but these was not in the scope of this study. The jelly of sun drying seaweeds with 7 times sun light exposure obtained the highest jelly hardness (

Table 1), followed by the jelly of sun drying seaweeds with 3 times exposure and halogen lamp drying seaweeds with 12 times exposure. This indicated the effect of sun drying and washing treatment will increase the agar yield and jelly strength of agar during extraction.

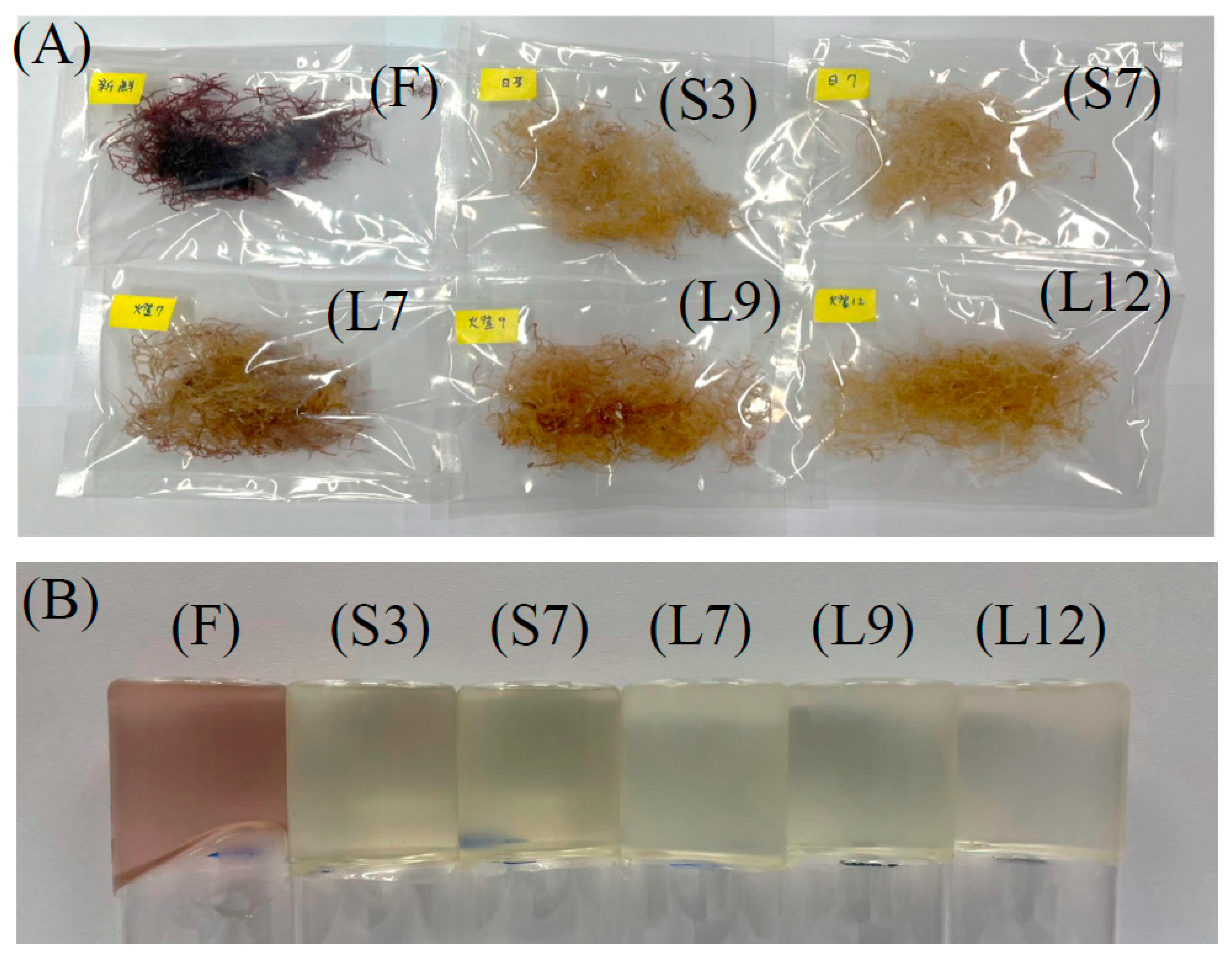

Although the effect of halogen lamp drying (15,000–20,000 lux) and washing treatment for twelve times showed lower agar yield compared to sun drying for seven times, it might due to the photobleaching effect on the red seaweeds by halogen lamp drying was not effective as sun drying (35,000–50,000 lux). The appearance of seaweed and agar were provided in

Figure 1. The maximum agar yield was observed at L9 (washing and halogen lamp drying cycles for 9 times), and decreased at L12. The jelly strength was found increased gradually with sun and halogen lamp drying cycles (

Table 1). Solar spectral irradiance for photobleaching in the first 5 h proved a significant effect on increasing agar gel strength but not agar yield [

10]. The gel strengths of native G. lemaneiformis and G. asiatica processed by oven drying at 60°C were reported as 2.66 N and 4.56 N, respectively [

4]. The gel strength mainly depends on the chemical structure of extracted agar, and was inversely proportional to the sulfate content of agar.

Figure 1.

A) Appearance of Gelidium seaweed; B) Appearance of Gelidium jelly.

Figure 1.

A) Appearance of Gelidium seaweed; B) Appearance of Gelidium jelly.

The springiness of Gelidium jellies showed a similar trend to the hardness. The jelly from sun-dried seaweed for 7 drying cycles observed the highest springiness, followed by the jelly from sun-dried seaweed for 3 drying cycles and halogen lamp-dried seaweed for 12 cycles (Table 1). Gelidium jellies were weak gels, especially for the oven dried sample (control, F), which observed a liquid-like characteristic.

Table 1.

Agar yields, gelling temperature and hardness of Gelidium jelly made by dried red seaweed with different drying processes.

Table 1.

Agar yields, gelling temperature and hardness of Gelidium jelly made by dried red seaweed with different drying processes.

| |

F |

S3 |

S7 |

L7 |

L9 |

L12 |

| Agar yield (%db) |

31.1± 6.2bc

|

35.6± 3.7bc

|

45.5± 8.7ab

|

23.0± 10.8c

|

58.1± 8.5a

|

28.1± 5.3bc

|

| Gelling temperature (°C) |

26.2± 2.3c

|

30.8± 0.2ab

|

31.1± 0.6a

|

27.5± 1.7bc

|

29.7± 0.7ab

|

30.7± 0.6ab

|

| Hardness (N/cm2) |

0.2± 0.01e

|

2.7± 0.1b

|

3.5± 0.1a

|

2.2± 0.1d

|

2.4± 0.0cd

|

2.6± 0.2bc

|

| Springiness |

0.1±0.1b

|

0.6±0.1a

|

0.6±0.2a

|

0.4±0.1ab

|

0.7±0.3a

|

0.6±0.0a

|

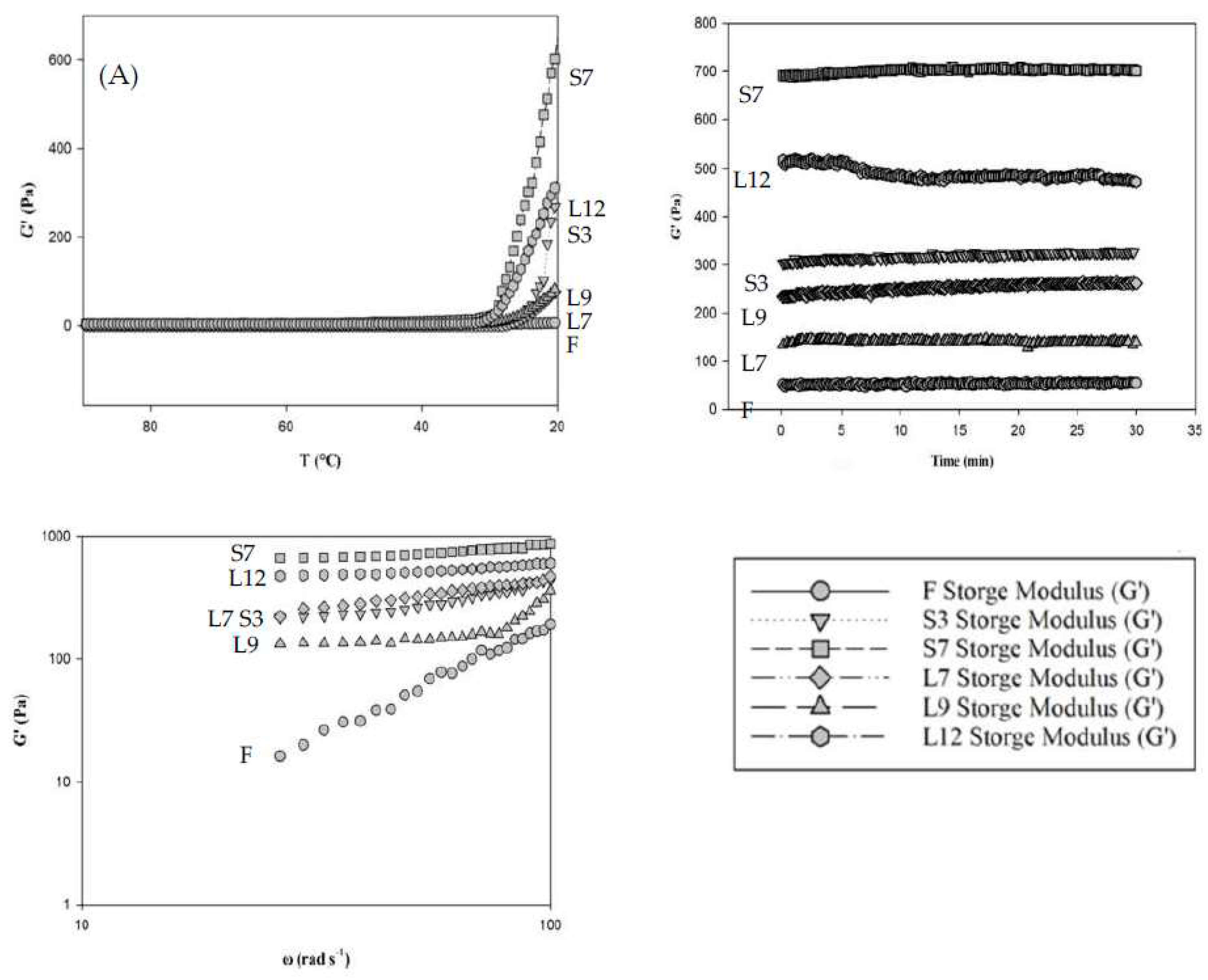

3.2. Effects of Drying Methods and Washing Cycles on Rheological Parameters of Agar Solutions Extracted from Gelidium Seaweeds

Data from the strain sweep tests demonstrated that the linear viscoelastic range of all extracted agar jellies was between 0.01% and 100% at 1 rad/s and 20°C, confirming that all measurements conducted at 0.5% shear strain were within the linear viscoelastic range (data not shown). Values of storage modulus (G') were used to compare the different treatments and considered as an indicator of gel rigidity [

11]. Gelation of agar sol-gel transition of dried red seaweed extract occurred by the formation of junction zones including cross-links and aggregation of helices [

12]. In addition, the gelation of pure agarose occurs in the first hardening step at 45°C during cooling from the solution-state at 90°C. In this study, the hardening step of cross-link gelation was not found at 45°C (

Figure 2A). Loss moduli (G'') were greater than storage moduli (G'), indicating that the hot agar extracted solutions were in a liquid state at 45°C (data not shown). Nevertheless, the second step of the helices joining to form aggregates was found below the sol-gel transition temperature ranges (31°C to 26°C) of gelling temperatures. Further hardening at 20°C was likely corresponded to the aggregation of helices, which increased the modulus G' further, especially for Gelidium jelly S7. The storage modulus of S7 showed the highest value, followed by L12 and S3. These storage modulus results were consistent with the hardness of Gelidium jellies (

Table 1 and Figure 2A). The storage modulus (G') was greater than the loss modulus (G'') at 20°C, which indicated a typically viscoelastic solid behavior by the contribution of the Gelidium jellies.

Storage modulus of curing curves (a relaxation of stresses developed during gel formation of Gelidium jellies at 20°C for 30 min) was shown in

Figure 2B. The storage modulus (G') of L12 decreased after 5 min aging at 20°C, which indicated that the agar jelly network was unstable and showed a nonequilibrium behavior under stress even after aging for short periods compared to the other samples. It was possible that all jellies were tenuous gel-like networks, which were weak gels. Particularly, L12 jelly which was easily broken when subjected to high enough stress (

Figure 2B).

Figure 2C showed the mechanical spectra of the Gelidium jellies. The storage modulus of fresh and untreated (F) and L9 jellies showed a typical behavior of weak gels, compared with the storage modulus of S7, S3, L7, and L12 samples which showed dramatic increases on the frequency sweep for the dynamic moduli. The values of slop were indicative for different nature of bonding in the network structures of jellies. The steeper slopes indicated liquid-like character for the sample at high frequency sweep [

11,

13], such as F and L9 Gelidium jellies.

Figure 2.

Analysis of rheological properties of Gelidium jellies: (A) Gelation: Storage modulus as a function of temperature, during cooling of Gelidium jellies. (B) Curing: Storage modulus as a function of time during ageing of Gelidium jellies. (C) Mechanical spectra: Storage modulus of Gelidium jellies as a function of frequency.

Figure 2.

Analysis of rheological properties of Gelidium jellies: (A) Gelation: Storage modulus as a function of temperature, during cooling of Gelidium jellies. (B) Curing: Storage modulus as a function of time during ageing of Gelidium jellies. (C) Mechanical spectra: Storage modulus of Gelidium jellies as a function of frequency.

3.3. Color Measurements of Dried Red Seaweeds and Appearance of Gelidium Jellies with Various Drying Methods and Washing Cycles

The color parameters of Gelidium seaweeds with different drying methods and washing cycles were shown in

Table 2. The L* value of S7 Gelidium seaweed had the highest L* and b* values, and the lowest a* value. This indicated the water washing and sun light exposure for 7 times achieved the highest levels of photobleaching in approximate 14 h duration during midday of around 35,000–50,000 lux. The appearance of dried Gelidium seaweeds and Gelidium jellies were shown in

Figure 1(A) and

(B), respectively. The color of dried seaweed turned into yellow due to the photobleaching effect and related to irradiance levels and high temperature [

14]. Fresh Gelidium seaweeds (F) dried at 50°C oven received barely no photobleaching. The control sample F showed the lowest L* and b* values in color (

Table 2). Besides, jelly made from oven dried seaweed still contained pigments and represented dark red in color. The pigmental proteins including allophycocyanin (APC), C-phycocyanin (C-PC) and R-phycoerythrin (R-PE) were reported to be the main pigments of red seaweed and were able to be photobleached under irradiation of a mercury lamp (450 W) with visible light at wavelengths longer than 470 nm, which drove the generation of superoxide radical anion, hydrogen peroxide, hydroxy radical, and singlet oxygen in oxygen-saturated aqueous solutions [

15]. All treatments received either sun drying or halogen lamp drying in the study showed bleached effect and turned into yellow with the extend irradiation.

Table 2.

Color parameters of Gelidium seaweed.

Table 2.

Color parameters of Gelidium seaweed.

| |

L |

a |

b |

ΔE#

|

| F |

26.1±1.6e

|

0.2±0.8c

|

15.6±4.3d

|

- |

| S3 |

50.8±2.6d

|

2.4±0.4a

|

38.7±1.3c

|

28.6±1.8d

|

| S7 |

67.9±1.0a

|

-2.3±0.1f

|

48.5±1.0a

|

46.3±2.9a

|

| L7 |

49.7±2.6d

|

-1.4±0.5e |

36.6±1.2c

|

27.0±4.0d

|

| L9 |

58.7±2.9c

|

1.3±0.5b

|

36.9±1.1c

|

35.2±2.2c

|

| L12 |

63.0±1.9b

|

-0.4±0.2d

|

44.0±2.8b

|

40.7±1.6b

|

3.4. Volatile Compounds of Dried Gelidium Seaweeds

Volatiles analyzed by GC-SPME of dried Gelidium seaweeds subjected to different washing and drying cycles were provided in supplementary

Tables S2-S7. These volatiles comprised mainly aldehydes, ketones and alcohols. The total volatiles semi-quantitated in dried red seaweeds listed in descending order were S3 (3387 ng/g), L7 (3232 ng/g), L9 (2807 ng/g), S7 (2729 ng/g), L12 (2441 ng/g), and F (2119 ng/g). The prolonged washing and drying process in either sun drying or halogen lamp drying favored evaporation of volatiles. Among all compounds identified, hexanal, 2-hexenal, heptanal, octanal, 2-nonenal and β-cyclocitral were found presented in all dried seaweed samples. These compounds were responsible for the green, floral, fatty, and seaweed odor characteristics.

The odor activity value (OAV) was calculated from semiquantitative concentrations of volatiles divided by the odor threshold (OT). Higher OAV implied a high contribution to the flavor profile of dried seaweed aroma (

Table 3). Aldehydes in seaweeds primarily result from enzymatic action of lipoxygenases, auto-oxidation, or degradation of polyunsaturated fatty acids [

16]. Despite their higher threshold compared to other volatile compounds, aldehydes contribute significantly to the aroma profiles of many foods. In this study, 17 aldehydes were identified in dried red seaweeds accounting for approximately 80% of the total volatiles. Among them, the 2,4-nonadienal and 2,4-decadienal offered extremely high OAVs in all sun drying and halogen lamp drying seaweed samples (

Table 3). This confirmed that these two aldehydes contribute to the aroma of dried Gelidium seaweed providing fat, wax, green, and fried (oily) odors.

The OAV of 2-decenal significantly increased after the drying and washing processes. Saturated aldehydes typically gave off green, grassy, citrusy, lemony, or orange peel-like odor sensations, as well as pungent, fatty, soapy, or tallowy aroma notes. Hexanal, with its grassy and green apple scent, was produced by lipid oxidation or by the sequential action of lipoxygenase/fatty acid hydroperoxide lyase (LOX/HPL) on linoleic acid [

17]. Hexanal contributed to the grassy and fishy odor in seafood. The concentration of hexanal was higher in oven dried Gelidium seaweed which did not receive washing process. 2-Nonenal and 2,4-decadienal represented a stale beer aroma with odor thresholds 0.1 ng/mL and 0.07 ng/mL, respectively. Beer brewing industries required to monitor the concentrations of these two compounds, due to they contributed to off-flavor in beer. These two compounds were also the primary volatile components of bread crumb providing roasted and green flavor notes. They were found increased in dried seaweed with the prolonged washing and drying cycles. Beta-cyclocitral, α-ionone and β-ionone were generated from the oxidative cleavage of α- and β-carotene at the double bond site between carbons 7 and 8 [

18]. Although they were was not considered as important odor contributors in dried seaweed due to their lower abundance, they were reported important odorants in raw seaweeds. Alpha and β-ionone were high in fresh, <S5 and <L5 samples but not detected in prolonged drying samples such as S7, L9, and L12, due to the photodegradation by UV photolysis during sun drying and halogen lamp drying [

19,

20].

Table 3.

Odor active values of dried Gelidium seaweeds analyzed by GC-SPME-MS.

Table 3.

Odor active values of dried Gelidium seaweeds analyzed by GC-SPME-MS.

| |

OAV** |

|

|

|

|

| |

Compound |

OT*

(ng/ml) |

F |

S |

S7 |

L7 |

L9 |

L12 |

odor |

odor reference |

OT

reference |

| 1 |

hexanal |

4.1 |

69 |

43 |

34 |

57 |

38 |

35 |

green, grass |

a |

[24] |

| 2 |

2-hexenal |

17 |

4 |

- |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

green, leaf |

a |

[24] |

| 3 |

2-heptanone |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

12 |

5 |

- |

Soap |

a |

[24] |

| 4 |

heptanal |

3 |

167 |

31 |

7 |

12 |

7 |

5 |

fat, citrus, rancid |

a |

[24] |

| 5 |

2-heptenal |

4.2 |

- |

80 |

42 |

67 |

59 |

- |

fat, grass |

a |

[25] |

| 6 |

1-octen-3-one |

0.05 |

- |

- |

- |

885 |

348 |

147 |

mushroom, butter |

a |

[24] |

| 7 |

1-octen-3-ol |

14 |

7 |

- |

- |

2 |

1 |

- |

mushroom |

a |

[24] |

| 8 |

octanal |

1.4 |

168 |

210 |

205 |

121 |

99 |

100 |

fat, soap, green |

a |

[24] |

| 9 |

2-octenal |

3 |

- |

102 |

21 |

79 |

60 |

37 |

green, nut, fat |

a |

[24] |

| 10 |

1-octanol |

42 |

- |

5 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

- |

pulpy, fruity, sweet |

[23] |

[24] |

| 11 |

3,5-octadien-2-one |

0.15 |

- |

- |

- |

299 |

60 |

- |

geranium, metal |

a |

[24] |

| 12 |

3,5-octadien-2-one |

150 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

earth, must |

a |

[24] |

| 13 |

nonanal |

1 |

- |

332 |

253 |

293 |

287 |

305 |

fat, citrus, green |

a |

[24] |

| 14 |

2,6-nonadienal |

0.09 |

481 |

316 |

- |

159 |

53 |

- |

cucumber, wax, green |

a |

[24] |

| 15 |

2-nonenal |

0.1 |

836 |

983 |

1370 |

778 |

1612 |

2147 |

cucumber, fat, green |

a |

[24] |

| 16 |

decanal |

0.1 |

- |

362 |

464 |

209 |

379 |

595 |

soap, tallow |

a |

[24] |

| 17 |

2,4-nonadienal, |

0.09 |

- |

2057 |

1206 |

4158 |

3364 |

2939 |

fat, wax, green |

a |

[24] |

| 18 |

2-decenal |

1 |

29 |

206 |

646 |

112 |

475 |

527 |

tallow |

a |

[24] |

| 19 |

β-ionone |

0.03 |

12632 |

747 |

- |

482 |

- |

- |

violet, flower |

a |

[24] |

| 20 |

2,4-decadienal |

0. 07 |

- |

2558 |

2154 |

4067 |

2634 |

1806 |

fried, wax, fat |

a |

[25] |

| 21 |

undecanal |

0.4 |

- |

- |

140 |

17 |

53 |

119 |

oil, pungent, sweet |

a |

[24] |

| 22 |

2-undecenal |

3.5 |

- |

18 |

30 |

- |

6 |

27 |

Sweet |

a |

[26] |

| 23 |

dodecanal |

0.5 |

- |

50 |

124 |

47 |

73 |

87 |

fatty, green |

[21] |

[24] |

| 24 |

α-ionone |

0.6 |

424 |

106 |

- |

60 |

20 |

20 |

wood, violet |

a |

[24] |

| 25 |

tetradecanal |

14 |

- |

2 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

Aldehyde |

[22] |

[25] |

3.5. Sensory Evaluation

The sensory attributes such as appearance, color, texture, flavor, overall acceptability, and fish odor of Gelidium jelly were summarized in Table 4. All processed seaweeds obtained higher scores than sample F (p < 0.05) which was dark in purple color and liquid-like weak gel. Jellies from sun and halogen lamp dried seaweed presented light yellow in color (Figure 1B) and firm in texture, especially for S7 and L12 jellies. Overall acceptability of samples S3, S7, and L12 were all acceptable with scores higher than 5 (average hedonic score). The majority of panelists preferred Gelidium jellies with harder texture, light yellow color, and lower fishy odor in this study. A correlation analysis was conducted between the physicochemical characteristics and sensory attributes to better understand the relationship among jelly quality properties of seaweeds with different treatments (Supplementary Table S1). The overall acceptability of Gelidium jelly samples was highly negatively correlated with fishy odor (p < 0.01) and positively correlated with b* value of dried seaweed, hardness, and springiness of jellies (p < 0.05).

Table 4.

Sensory evaluation of Gelidium jelly made by dried seaweeds by different drying processes.

Table 4.

Sensory evaluation of Gelidium jelly made by dried seaweeds by different drying processes.

| |

Appearance |

Color |

Texture |

Flavor |

Overall |

Fishy odor* |

| F |

3.35±2.10c

|

3.73±2.16c

|

2.74±1.96c

|

2.27±1.70d

|

2.53±1.72c |

7.59±2.25a

|

| S3 |

5.65±2.06ab

|

6.07±1.67ab

|

5.80±2.31a

|

4.68±2.08ab

|

5.58±2.20a

|

4.67±2.50c

|

| S7 |

5.87±2.19a

|

5.93±2.23a

|

6.59±2.00a

|

5.38±2.22a

|

6.05±1.95a

|

3.80±2.39c

|

| L7 |

4.67±2.01b

|

5.33±1.73b

|

2.91±1.48c

|

3.02±1.90cd

|

3.29±1.76bc

|

6.02±2.30b

|

| L9 |

5.18±2.00ab

|

5.68±1.71ab

|

4.09±1.86b

|

3.71±1.69bc

|

4.00±1.90b

|

5.91±2.33b |

| L12 |

5.80±2.10a

|

5.90±1.90a

|

5.64±2.24a

|

4.97±2.20a

|

5.44±2.21a

|

3.77±2.29c

|

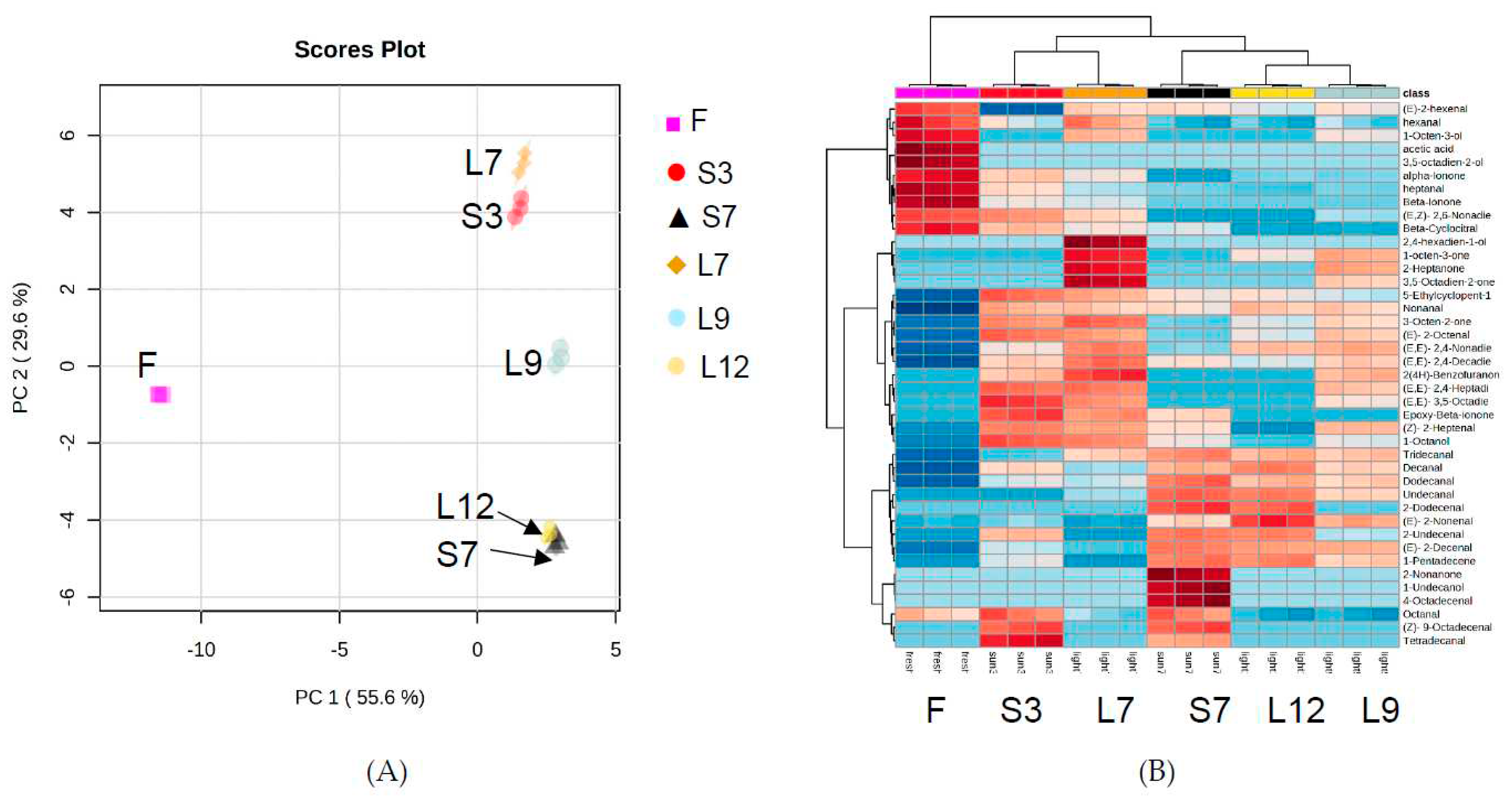

3.6. Principal Component Analysis of volatiles

The amounts semi-quantitated volatiles in each processed seaweed (Supplementary Table S2-7) were used as variables, and visualized by principal component analysis (PCA) in Figure 3A. PC1 and PC2 accounted for 85% of the variation. The triplicate samples of each drying treatment of Gelidium seaweed were clustered together and separated into four different groups: F sample group, L7 and S3 sample group, L9 sample group, and L12 and S7 sample group. The closer groups were related or called similar. Hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) was used to reveal the changes in the volatile compound profiles among all six samples of different drying and washing cycles. The resulting heatmap (Figure 3B) demonstrated similar results to PCA, that the drying effects on volatiles of sun drying for 7 cycles was similar to halogen lamp drying for 12 cycles, and the sun drying for 3 cycles was similar to halogen lamp drying for 7 cycles. This study found halogen lamp drying may be a good replacement of sun drying on production of dried Gelidium for jelly.

Figure 3.

A) Scores plot of volatile compounds in Gelidium seaweed.; B) Heatmap of volatile compounds in Gelidium seaweed.

Figure 3.

A) Scores plot of volatile compounds in Gelidium seaweed.; B) Heatmap of volatile compounds in Gelidium seaweed.

4. Conclusions

The washing and drying cycles of Gelidium seaweed by sun drying and halogen lamp drying were significant parameters on the sensory quality and volatile composition of Gelidium jellies. Halogen lamp drying provided similar effects to sun drying, which improved the yield and strength of extracted agar. These processes removed unpleasant smell (volatile components), such as hexanal, but enhanced long chain unsaturated alkylaldehydes such as decenal and 2-nonenal which provided green, waxy and floral odors. The novel introduction of halogen lamp drying method for Gelidium seaweed could be an alternative option for traditional sun drying processing, especially in rainy days. Sensory evaluation and volatile odorants analysis demonstrated that Gelidium jellies made from traditional sun drying for 7 cycles and halogen lamp drying for 12 cycles showed similar results. This investigation and report may benefit the seaweed jelly industry by aiding in the development of drying techniques and seaweed processing.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Correlation coefficients of color, texture, and sensory evaluation results of Gelidium seaweed; Table S2: Volatile compounds of Fresh and untreated Gelidium seaweed ; Table S3: Volatile compounds of dried Gelidium seaweed (three washing and sun drying cycle); Table S4: Volatile compounds of dried Gelidium seaweed (seven washing and drying cycles) ; Table S5: Volatile compounds of Gelidium seaweed (seven washing and halogen lamp drying cycles); Table S6: Volatile compounds of Gelidium seaweed (nine washing and halogen lamp drying cycles); Table S7: Volatile compounds of Gelidium seaweed (twelve washing and halogen lamp drying cycles).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M. Fang, H-T, Lin; methodology, W-C. Song, H-T, Lin; formal analysis, W-C. Liao; investigation, W-C. Liao, W-C. Song; writing—review and editing, M. Fang; project administration, W-C. Song.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fink, P. (2007). Ecological functions of volatile organic compounds in aquatic systems. Marine and Freshwater Behaviour and Physiology, 40, 155-168. [CrossRef]

- Hurler, J., Engesland, A., Poorahmary Kermany, B., Škalko-Basnet, N. (2012). Improved texture analysis for hydrogel characterization: Gel cohesiveness, adhesiveness, and hardness. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 125(1), 180-188. [CrossRef]

- Garrido, J. I., Lozano, J. E., Genovese, D. B. (2015). Effect of formulation variables on rheology, texture, colour, and acceptability of apple jelly: Modelling and optimization. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 62(1), 325-332. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Yu, X., Jin, Y., Zhang, W., Liu, Y. (2008). Development of an eco-friendly agar extraction technique from the red seaweed Gracilaria lemaneiformis. Bioresource Technology, 99, 3301-3305. [CrossRef]

- Kurmar, V., Fotedar, R. (2009). Agar extraction process for Gracilaria cliftonii. Carbohydrate Polymers, 78, 813-819. [CrossRef]

- Azizi, N., Najafpour, G., Younesi, H. (2017). Acid pretreatment and enzymatic saccharification of brown seaweed for polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) production using Cupriavidus necator. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 101, 1029-1040. [CrossRef]

- Chirapart, A., Praiboon, J. (2018). Comparison of the photosynthetic efficiency, agar yield, and properties of Gracilaria salicornia (Gracilariales, Rhodophyta) with and without adelphoparasite. Journal of Applied Phycology, 30(1), 149-157. [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, M. A., Manzano-Sarabia, M., Hernandez-Garibay, E., Pacheco-Ruiz, I., Zertuche-Gonzalez, J. A. (2011). Latitudinal variations of the yield and quality of agar from Gelidium robustum (Gelidiales, Rhodophyta) from the main commercial harvest beds along the western coast of the Baja California Peninsula, Mexico. Journal of Applied Phycology, 23(4), 727-734. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Shen, Z., Mu, H., Lin, Y., Zhang, J., Jiang, X. (2017). Impact of alkali pretreatment on yield, physico-chemical and gelling properties of high quality agar from Gracilaria tenuistipitata. Food Hydrocolloids, 70, 356-362. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Huang, J., Xin, Y., Zhang, B., Jin, Y., Zhang, W. (2009). Optimization and scale-up of a new photobleaching agar extraction process from Gracilaria lemaneiformis. Journal of Applied Phycology, 21, 247-254. [CrossRef]

- Genovese, D. B., Ye, A., Singh, H. (2010). High methoxyl pectin/apple particles composite gels: effect of particle size and particle concentration on mechanical properties and gel structure. Journal of Texture Studies, 41(2), 171-189. [CrossRef]

- Nordqvist, D., Vilgis, T. A. (2011). Rheological study of the gelation process of agarose-based solutions. Food Biophysics, 6, 450-460. [CrossRef]

- Basu, S., Shivhare, U. S., Singh, T. V., Beniwal, V. S. (2011). Rheological, textural and spectral characteristics of sorbitol substituted mango jam. Journal of Food Engineering, 105(3), 503-512. [CrossRef]

- Quintano, E., Diex, I., Muguerza, N., Figueroa, F. L., Gorostiaga, J. M. (2017). Bed structure (frond bleaching, density and biomass) of the red alga Gelidium corneum under different irradiance levels. Journal of Sea Research. [CrossRef]

- He, J. A., Hu, Y. Z., Jiang, L. J. (1997). Photodynamic action of phycobiliproteins: in situ generation of reactive oxygen species. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Bioenergetics, 1320(2), 165-174. [CrossRef]

- Le Pape, M.A., Grua-Priol, J., Prost, C., Demaimay, M. (2004). Optimization of dynamic headspace extraction of the edible red algae palmaria palmata and identification of the volatile components. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 52, 550-5560. [CrossRef]

- Ties, P., Barringer, S. (2012). Influence of lipid content and lipoxygenase on flavor volatiles in the tomato peel and flesh. Journal of Food Science, 77(7), C830-C837. [CrossRef]

- Mahattanatawee, K., Rouseff, R., Valim, M. F., Naim, M. (2005). Identification and aroma impact of norisoprenoids in orange juice. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 53(2), 393-397. [CrossRef]

- Kim, T., Kim, T. K., Zoh, K. D. (2019). Degradation kinetics and pathways of β-cyclocitral and β-ionone during UV photolysis and UV/chlorination reactions. Journal of Environmental Management, 239, 8-16. [CrossRef]

- Lalko, J., Lapczynski, A., McGinty, D., Bhatia, S., Letizia, C. S., Api, A. M. (2007). Fragrance material review on β-ionone. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 45(1), S241-S247. [CrossRef]

- Quynh, C. T. T., Kubota, K. (2016). Study on the aroma model of Vietnamese coriander leaves (Polygonum odoratum). Vietnam Journal of Science and Technology, 54(4A), 73-73.

- Shiratsuchi, H., Shimoda, M., Imayoshi, K., Noda, K., Osajima, Y. (1994). Off-flavor compounds in spray-dried skim milk powder. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 42(6), 1323-1327. [CrossRef]

- De Sousa Galvão, M., Narain, N., dos Santos, M. D. S. P., Nunes, M. L. (2011). Volatile compounds and descriptive odor attributes in umbu (Spondias tuberosa) fruits during maturation. Food Research International, 44(7), 1919-1926. [CrossRef]

- Vilar, E. G., O'Sullivan, M. G., Kerry, J. P., Kilcawley, K. N. (2020). Volatile compounds of six species of edible seaweed: A review. Algal Research, 45, 101740. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S., Yu, G., Qi, B., Yang, X., Deng, J., Zhao, Y., Rong, H. (2016). Analysis of volatile compounds of dried Gracilaria lemaneiformis by HS-SPME method. South China Fisheries Science, 12(6), 115-122.

- Tan, Y., Siebert, K. J. (2004). Quantitative structure−activity relationship modeling of alcohol, ester, aldehyde, and ketone flavor thresholds in beer from molecular features. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 52(10), 3057-3064. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).