1. Introduction

The tourism sector's substantial financial contribution of

$8.9 trillion, representing about 10.3% of the global gross domestic product in 2019 [

1], has a two-fold impact. While tourism benefits local economies economically, it also stresses the environment considerably [

2]. This strain has led to increased ecological damage and pollution in tourist destinations. Unfortunately, many tourists exhibit limited restraint, environmental awareness, and self-discipline, resulting in behaviors that can be deemed uncivilized [

3,

4,

5]. Such conduct contributes to ecological issues in these areas, posing challenges to their overall ecological health [

6] and compelling nations to seek more efficient strategies for managing tourism [

7].

The Hurtado balneary, situated in Valledupar, Colombia, is a prime example. Acting as a major attraction in a municipality of 532,956 inhabitants within the Cesar department, the area is subdivided into 25 territorial divisions, 102 villages, 204 neighborhoods, and 15 settlements [

8]. The balneary grapples with planned disruptions in environmental quality, largely attributed to the surge of tourists [

8]. The upsurge in unsustainable tourism practices and informal trade has triggered negative environmental consequences, evident through the accumulation of waste in riverbeds and riparian zones. This disruption alters landscapes and impacts water quality indicators such as dissolved oxygen, pH levels, organic matter concentration, and suspended solids, particularly in tourist areas.

Rivers play a crucial role in aquaculture, irrigation, recreation, electricity generation, and public water supply [

9]. The escalating global demand for river water amplifies water extraction, decreasing available water volume. Simultaneously, these rivers receive waste from human activities, causing water quantity and quality changes. These alterations disrupt communities, users, aquatic ecosystems, vegetation, and riverside fauna. The pollution of rivers has negative repercussions on human health, access to quality water for economic and recreational uses, and the well-being of aquatic biodiversity. Given the high human traffic in these areas, strategic planning for spaces, facilities, and tourist activities becomes imperative to protect the environment and sustain the allure of natural resources for future generations [

10].

This scenario underscores the importance of sensitizing visitors and those responsible for managing the Hurtado balneary. Consequently, exploring environmental education initiatives becomes crucial, often spearheaded by higher education institutions involved in raising awareness. Environmental education is a powerful tool in addressing environmental impacts, aiming to foster ecological and environmental safeguards [

11]. By influencing perceptions and actions, environmental education encourages individuals to adopt responsible behaviors [

12], making it indispensable for advancing sustainable development [

13]. Recognizing intrinsic motivations within human behavior is pivotal in mitigating anthropogenic environmental effects [

14,

15], given the transient nature of extrinsic incentives [

16].

The interaction between environmental education and perception is closely tied to individual and societal dynamics. This understanding underscores the role of individual perceptions as a catalyst for environmental education, shaping behaviors within social contexts. Additionally, the evolution of media provides novel avenues for reshaping human environmental attitudes [

17], necessitating reflection on social practices in situations marked by environmental degradation.

Considering this, evaluating environmental perception among visitors to the Hurtado balneary is pivotal, offering insights into how individuals perceive and respond to environmental challenges. This evaluation is instrumental in identifying pathways toward solutions through environmental education. The study's primary goal was to assess tourists' environmental perception concerning solid waste and its impact on the Hurtado balneary and Guatapurí River in Valledupar, Colombia. Utilizing observations, photographic records, and an extensive online questionnaire conducted between May and July 2023, the study engaged 769 users, probing their perceptions and behaviors toward waste disposal. Through analyzing their conceptions, actions, and behaviors, the study aims to provide insights to inform strategies for solid waste management. Recommendations include strengthening environmental education and awareness, improving signage for waste disposal, increasing the availability of waste receptacles, and promoting zero waste and recycling initiatives. By aligning with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 12, 13, and 15, focused on responsible consumption, climate action, and ecosystem conservation, the study contributes to global sustainability efforts. While the study focuses on Colombian tourists, its findings offer relevance to nature-based tourism destinations worldwide.

2. Materials and Methods

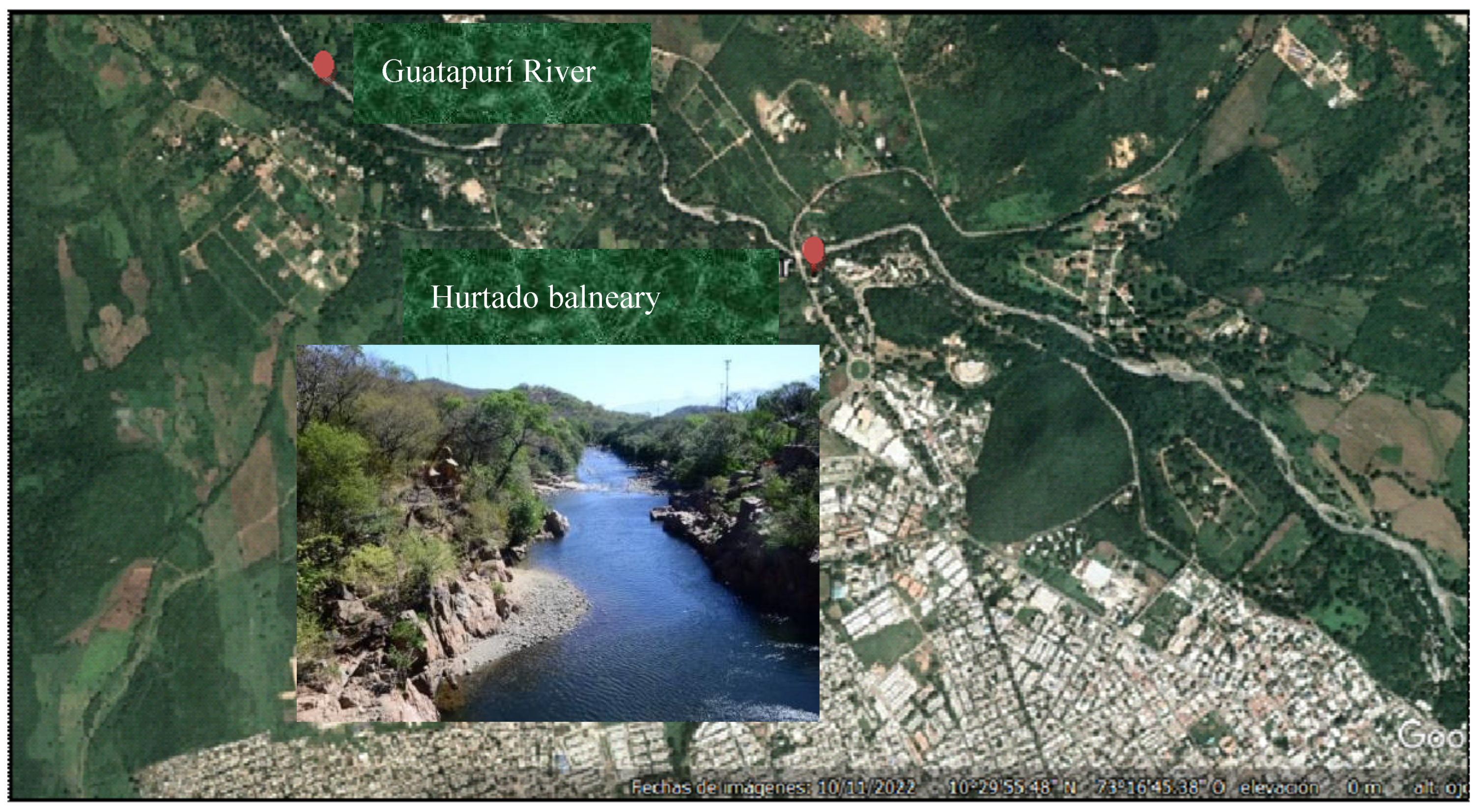

In the context of the Hurtado balneary and the Guatapurí River, situated within Valledupar, Colombia, with a population of 532,956 residents, the area faces environmental challenges stemming from tourism and waste management practices [

8]. This region occupies 4,493 km

2, constituting 18.8% of the Cesar department's total extension. The municipality encompasses 102 villages, 204 neighborhoods, and 15 settlements [

8]. The Guatapurí River (

Figure 1), a natural water reserve critical to the balneary, experiences significant water contamination [

18].

The Hurtado balneary, a recreational space, witnesses a surge in visitors during weekends, resulting in soil and water impacts and an influx of organic and inorganic waste, including food remnants, packaging, and various disposables (

Figure 2).

However, managing waste collection spaces remains problematic (

Figure 3). This challenge is amplified during peak visitor periods, exacerbated by a lack of dedicated personnel to monitor behavior. Current waste collection is primarily performed by on-site staff, who hastily collect visible waste shortly after its generation. Unfortunately, this approach fails to address waste that eventually finds its way into the river, becomes embedded in the ground, or is dispersed by wind, leading to environmental degradation. Moreover, no comprehensive assessment of local species and the impacts of continuous human presence and waste on them has been conducted.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 emphasize the necessity for more stringent regulations, surpassing existing norms, through the implementation of proven standards and indicators for managing solid and liquid waste and compensatory measures to mitigate adverse impacts. The present state of the Hurtado balneary serves as an example of conventional management, where visitors habitually leave various forms of waste near the river and recreational areas.

Despite waste bins, these facilities are often underused, as visitors frequently dispose of waste directly on the ground or into the river currents. Notably, compliance with Resolution 2184 of 2019 [

19], which mandates color-coded waste separation at its source to promote national waste segregation, is lacking.

The research employed a survey method to collect data on attitudes, beliefs, behaviors, and values. This scenario included semi-structured questionnaires, photographic records, and observations, engaging 769 balneary visitors between May and July 2023 via an online platform (

Table 1). The survey aimed to understand participants' perceptions of solid waste, water, and their habits influencing these aspects, as well as their comprehension of the balneary.

Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected. The study analyzed quantitative data using Microsoft Excel to generate percentages and graphs, while qualitative data from questionnaires and observations were subjected to thematic analysis to identify patterns and themes. Moreover, Pearson's Chi-square test was employed to analyze the statistical significance of differences in response distributions between groups.

The research delved into the analysis of perception in the Hurtado balneary, adopting a methodological framework proposed by Hurtado [

23], incorporating criteria examined by other researchers [

20,

21,

22]. The study's methodology culminated in a detailed analysis of perceptions and behaviors related to solid waste, informing strategies for waste management and environmental conservation.

This study underscores the need for enhanced waste management practices and environmental education in the Hurtado balneary to mitigate the detrimental effects of tourism and waste on the ecosystem. The study provides valuable insights into the perceptions and behaviors of balneary visitors utilizing a multifaceted research approach encompassing qualitative and quantitative methods. This approach paves the way for informed decision-making and the development of sustainable strategies, ultimately contributing to the preservation of natural resources and aligning with global sustainability goals.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Diagnosis of the Situation of organic and Inorganic Solid Waste of the Hurtado Balneary on the Banks of the Guatapurí River

The Hurtado balneary is experiencing a lack of proper waste management, particularly along the banks of the Guatapurí River. Various types of solid waste, including glass bottles, plastic containers, disposable items, plastic bags, straws, dry branches, and food scraps, are improperly discarded at this location (

Figure 4). It is crucial that this waste is disposed of correctly and collected regularly to prevent its accumulation and potential migration to the riverbed through wind action.

Figure 4 illustrates the environmental situation at the Hurtado balneary, highlighting the inappropriate disposal of solid waste. Plastic, glass bottles, plastic bags, and face masks are this area's most observed waste categories. This scenario can be attributed to the excessive consumption of alcohol, soft drinks, and disposable products used by leisure visitors, leading to significant waste of these materials. These results are from the study conducted by Chapelle and Gouin [

24], which suggests that tourist destinations produce diverse waste materials, primarily including organic waste, cardboard, paper, glass, tin, plastic, and packaging. Similarities were also found in Dias Filho et al. [

17] study conducted at Boa Viagem beach in Pernambuco, Brazil, where plastic waste was prevalent. The waste composition at the Hurtado balneary resembles that of Nairobi, as noted by Karanja [

25], who emphasized the abundance of plastic bags of different sizes and colors. Karanja [

25] also observed an increase in food packaging, bottling, and the use of cans by the local population. The increase in non-biodegradable substances is thought to be driven by the global expansion of the economy [

25]. Solid waste is growing in volume and undergoing compositional changes, with plastics emerging as the predominant component. Lopes and Cornelian [

26] identified residents as the main contributors to environmental issues on Peruíbe beach in São Paulo, Brazil. Proper management of solid waste is crucial to address environmental pollution that impacts the soil, river water, landscape, and terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems.

Additionally, it can lead to the proliferation of vectors such as flies, mosquitoes, rodents, and diseases. ASEO DEL NORTE SA ESP, CORPOCESAR, and leaders of the mayor's office are expected to have the authority to address these problems. These issues should be identified and resolved promptly if these organizations conduct inspections.

3.2. Socioeconomic Characteristics of Respondents in the Study Area

The demographic characteristics of the respondents revealed that a larger proportion of women (64%) participated in the survey than men (36%). The results obtained from the profile of the interviewees, in which the majority are female, are by the National Population and Housing Census carried out in 2018, where a total of 49,395,678 people were projected for the year 2019, representing 48.8% of men and 51.2% of women [

27]

The sample is represented mostly by local visitors (86%), while the percentage of tourists was 11% and traders only 3%. Although the sample varies in age, older people are often an exception (those 50 and over make up only 18% of the sample). About 53% of those surveyed were between the ages of 25 and 50, with the second largest group being those under 25 (29%).

3.3. Level of Knowledge, Behaviors, and Perceptions of the Users of the Hurtado Balneary Regarding Organic and Inorganic Solid Waste

An attitude is a conceptual framework that reflects an individual's preferences or aversions toward an object or concept. Attitudes can also be perceived as a learned predisposition to assess things from a specific perspective. These assessments typically fall between favorable and unfavorable, occasionally encompassing a sense of uncertainty (neutrality). The amalgamation of knowledge and attitudes substantially shapes people's conduct, choices, and judgments. Positive attitudes can substantially enhance waste management practices in solid waste, while negative attitudes can impede effective strategies.

It's important to note that attitudes are not static but dynamic. The same factors contributing to the formation of attitudes can also pave the way for attitude transformation. In examining attitudes, one must consider the socioeconomic traits of the respondents and their inclinations toward managing solid waste.

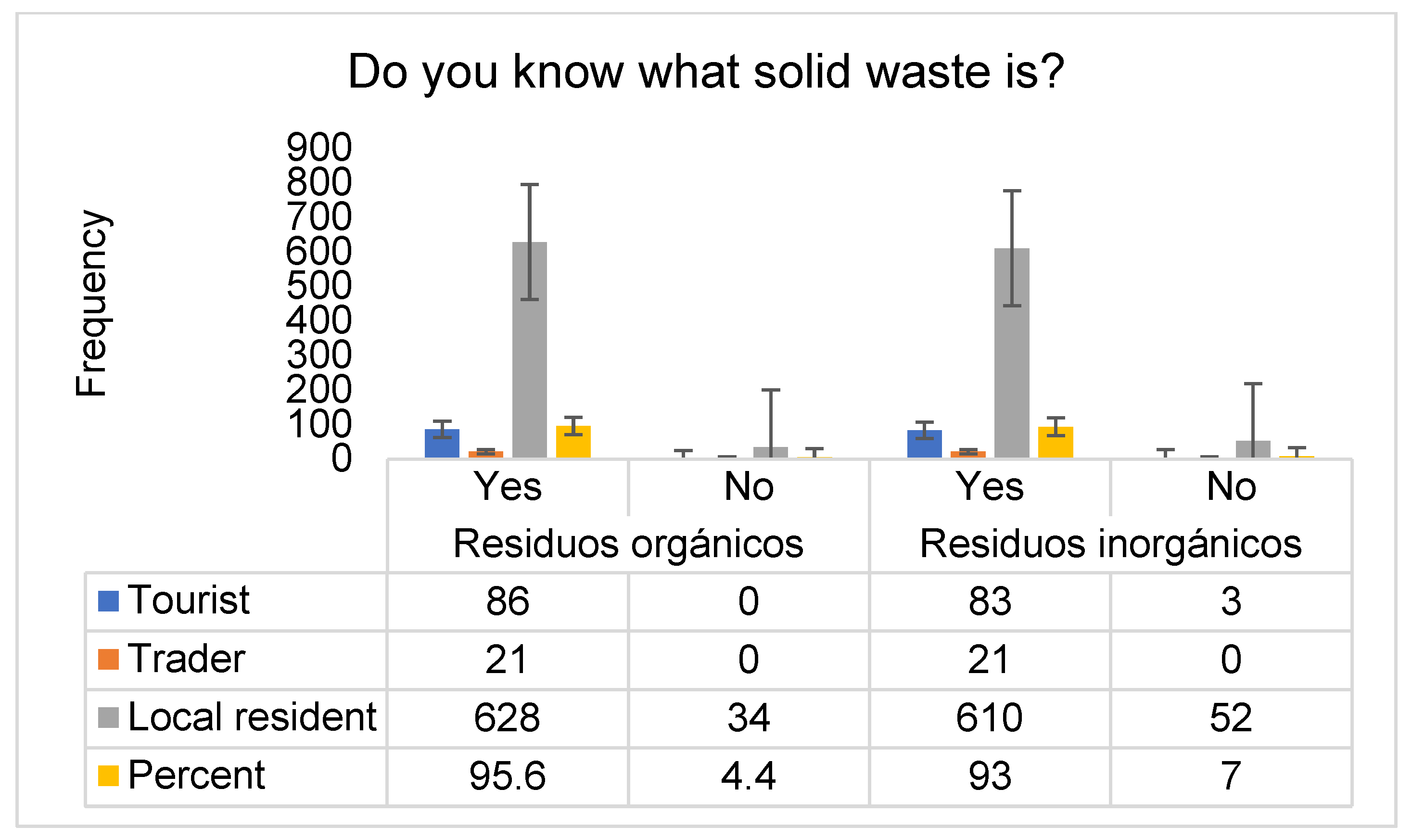

3.4. Level of Knowledge Regarding the Difference between Solid Waste

The waste classification process consists of separating them into different components. The waste can be sorted manually on the site and collected through steel collection programs, or it can be separated automatically in installations that recycle materials or employ mechanical biological treatment systems. The volume of solid waste that must be disposed of is reduced through classification, which reduces expenses and the burden of waste disposal. The classification of waste also improves the recycling of various resources. The results for this variable are shown in

Figure 5, which shows that most of those surveyed (more than 95%) know what they are inorganic. There was a significant statistical difference at the significance level of 5%. P-value = 0.145. To inorganic solid waste (93%), there was little statistical difference at the level of significance at 5%. P-value = 0.056. This scenario means that the type of user and the knowledge regarding solid waste are dependent.

The results of

Figure 5 show that almost 100% of the respondents answered that they know what organic and inorganic solid waste are, indicating that there will be no difficulties in properly separating waste. Most of these materials can be recycled through different processes by recycling and composting plants.

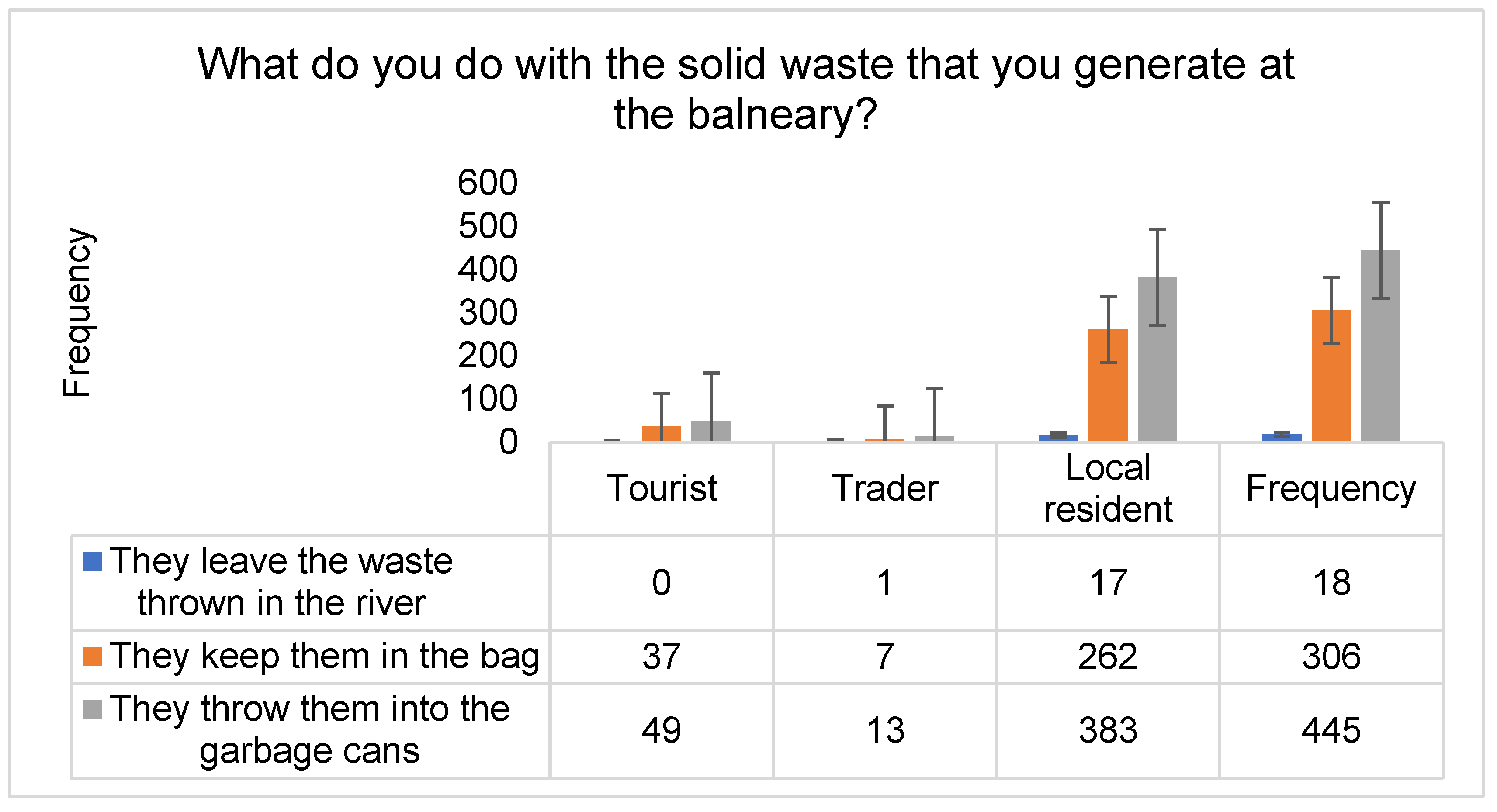

3.5. Knowledge Regarding the Problem of Contamination of the Guatapurí River

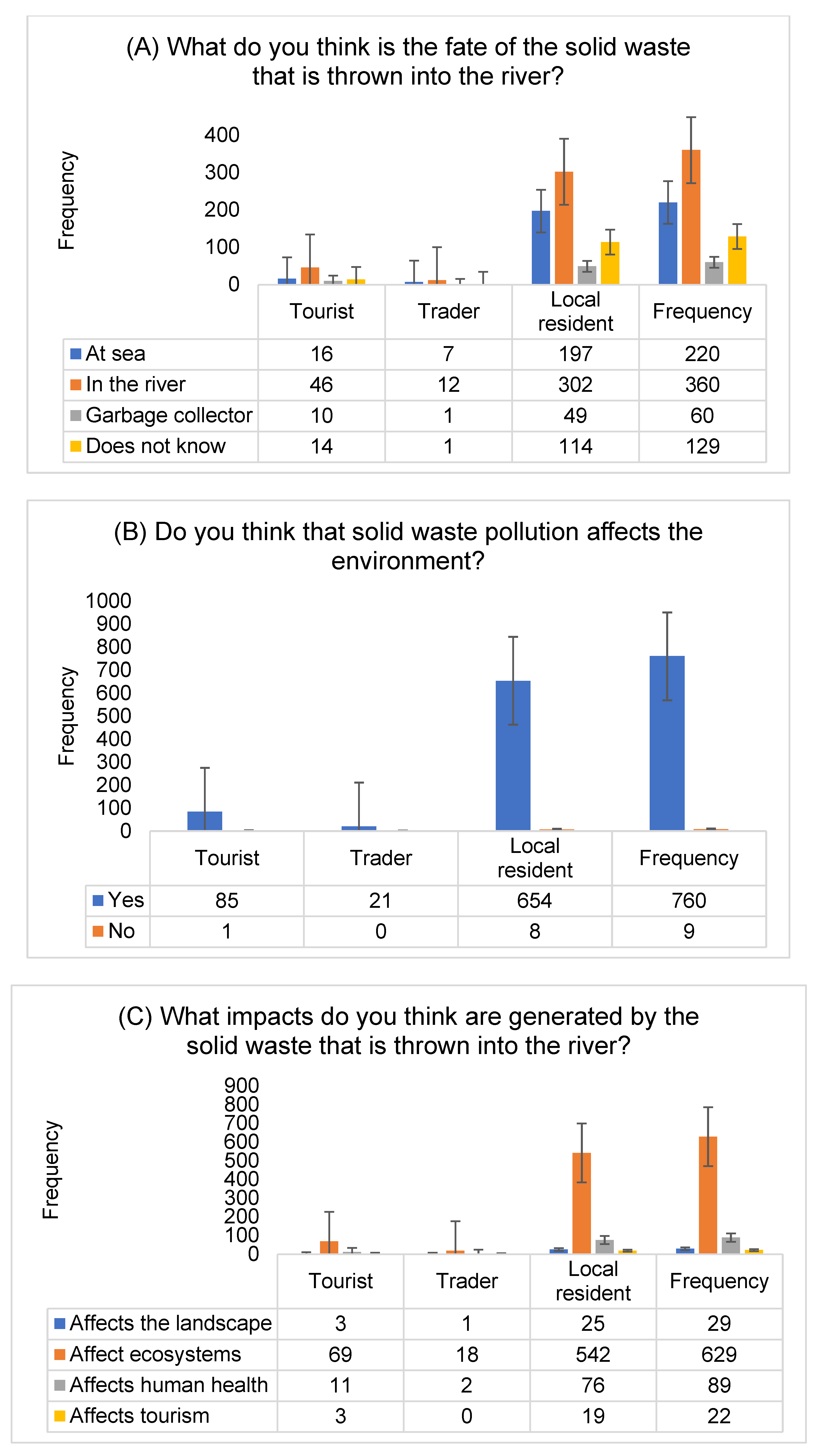

Figure 6 (A–C) provides insights into the surveyed participants' awareness of the Guatapurí River contamination issue. In terms of waste disposal, 28.6% (220) acknowledged that waste ends up in the sea, while 46.8% (360) believed it to be in the river; other respondents were unsure (

Figure 6A).

There was a statistically significant difference with a p-value of 0.325. When considering the environmental impact, a substantial 98.8% (760) recognized that solid waste contamination adversely affects the environment (

Figure 6B), with a significant p-value of 0.523. Examining the consequences of waste dumped into the river, 81.8% (629) indicated that it harms ecosystems (

Figure 6C), accompanied by a significant p-value of 0.248. These findings underline the interdependence between user type and knowledge of solid waste disposal.

3.6. Perception of Visitors about the Causes of Contamination by Solid Waste

The problems of aptitudes and perceptions of the visitors to the balneary about the causes of pollution in the study area influence the littering behavior of people. To gauge respondents' views regarding their knowledge of the causes of pollution, they were asked questions about environmental problems that result from improper waste disposal, among other things.

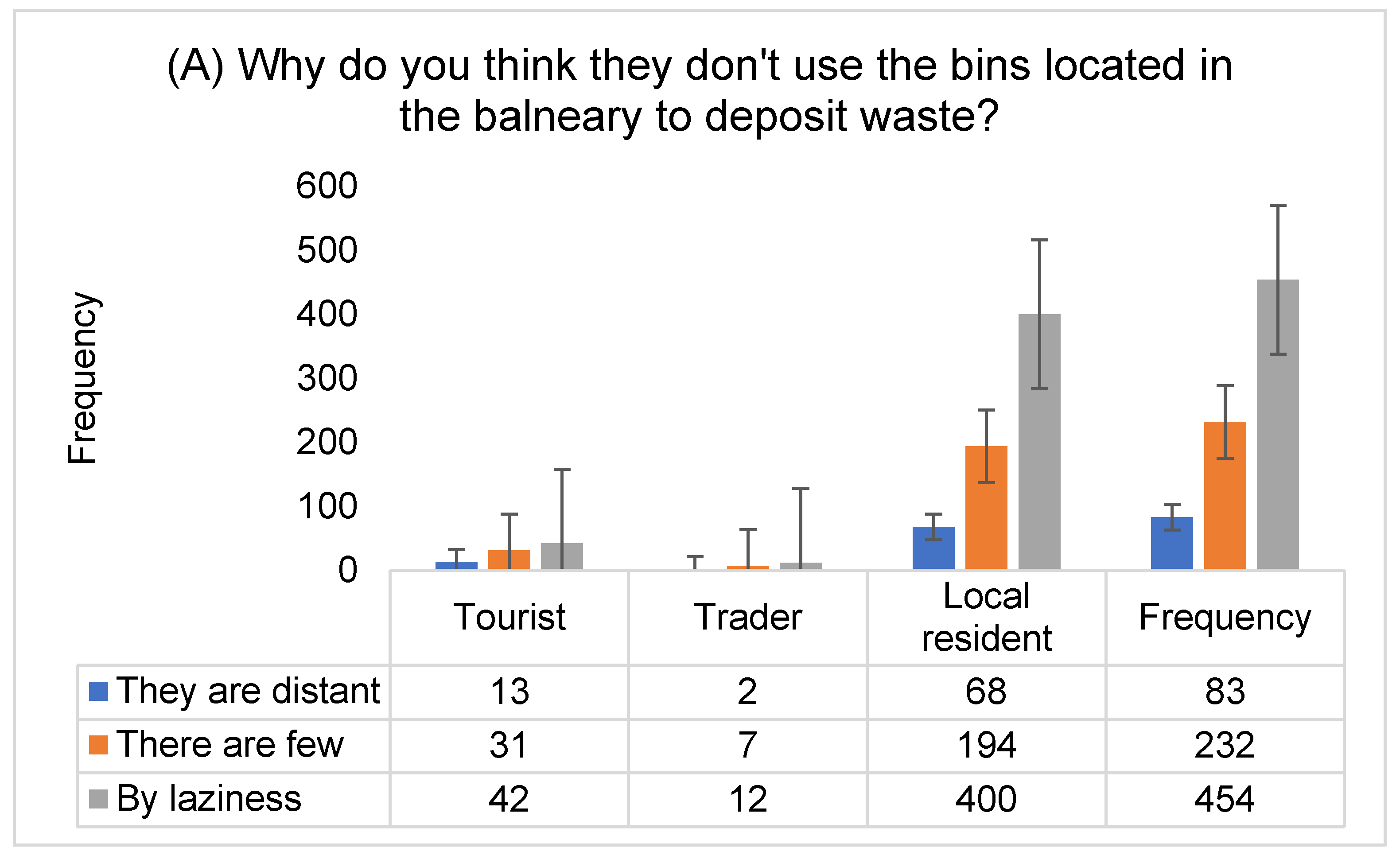

Figure 7 (A – D) shows the possible causes of the impacts generated by solid waste.

According to the results shown in

Figure 7A, laziness was the main reason for not placing solid waste in the cans, followed by the fact that there are few in the Hurtado balneary. There was no statistically significant difference at the 5% significance level. P-value = 0.005. This trend means that the type of user and his perceptions of the cause of the contamination are independent.

Solid waste is thrown on the ground because of the lack of ownership and environmental education (

Figure 7B). There was a significant statistical difference at the significance level at 5%. P-value = 0.393. This behavior means that the type of user and the perception of the cause of contamination by solid waste in the balneary are dependent.

Figure 10C shows that most respondents consider that the residents are the main responsible for the contamination of the Hurtado balneary. There was a significant statistical difference at the significance level of 5%. P-value = 0.983. This trend means that the type of user and their perceptions of the main causes of solid waste contamination are dependent.

In

Figure 7D, most users affirmed that signaling is needed to conserve the river. There was a significant statistical difference at the significance level of 5%. P-value = 0.423. This result means that the type of user and the perception regarding the need for signaling to conserve the Guatapurí River are dependent.

Given the above, the accumulation of solid waste inside and outside the bins was the most relevant environmental impact observed by the researcher, followed by the absence of bins. The Hurtado balneary lacks a basic infrastructure to maintain cleanliness, which makes even the collaboration of users concerning the conservation of the site impossible. The absence of adequate bins for the selective disposal (in colors, black, white, and green) of the waste contributes negatively to the accumulation of solid waste in the extension of the balneary. Similar results were found by Silva and Souza [

28] in Praia do Farol, in Pará, Brazil, where 56.6% of those surveyed pointed to the excess of "garbage" as one of the most significant environmental impacts in the area. In a study conducted by Santana Neto et al. [

29] at Porto da Barra beach, Bahia, Brazil, it was observed that 84.3% of tourists also considered the inappropriate disposal of solid waste in the vicinity as a recurring environmental impact. For Farias [

30], this situation is worrying because the accumulation of solid waste not only affects the landscape but also interferes with the quality of human life in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems.

According to Rezende et al. [

31], the frequent occurrence of environmental degradation may be related to the lack of environmental education, which must educate people about the importance of the rational use of natural resources since it can affect how they perceive and are related to the environment.

Changes in human behavior are one of the key steps in solving environmental problems. Therefore, environmental education must be seen not only to protect the environment but also as a tool that can maintain a harmonious relationship between man and nature, depending on the attitudes of everyone within this system. In this context, Silva et al. [

32] argue that it is necessary to establish actions that prioritize human well-being, the preservation of natural resources used as tourist attractions, and the sustainable use of these places.

A combination of laziness and disregard has fostered a culture of consistent untidiness. Neglect has led individuals to casually discard waste without considering the repercussions of their actions. A substantial portion of the population remains unaware of or underestimates the adverse consequences of littering on the environment. This scenario arises from the notion that individual actions have minimal societal impact.

Consequently, seeing individuals disposing of items like wrappers and cigarette butts in public areas is all too familiar. A prevailing belief among many is that others will assume the responsibility of tidying up after them, leading to a scenario where the duty of waste cleanup frequently falls upon local authorities and taxpayers [

33].

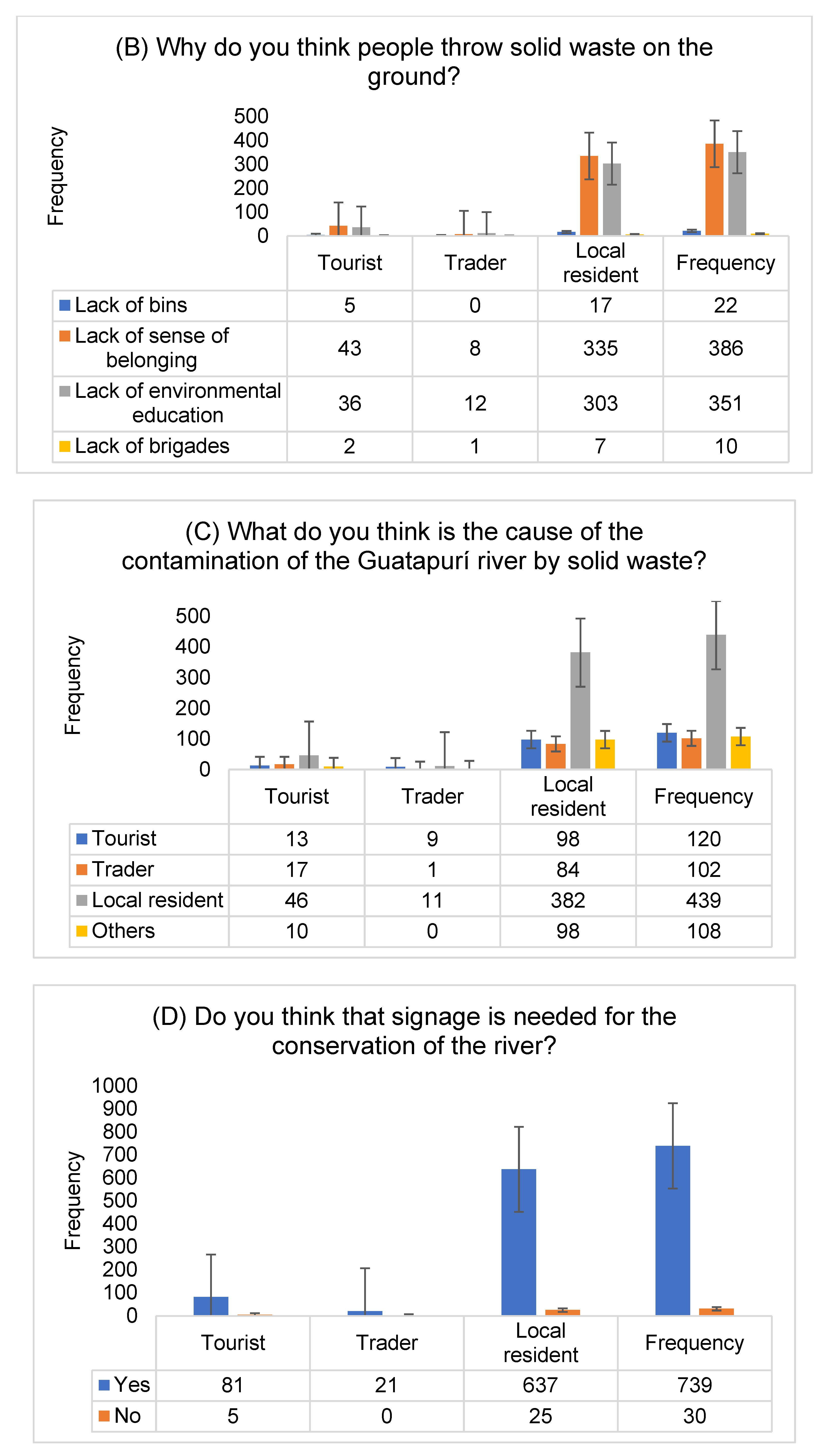

3.7. Behaviors Regarding User Waste Disposal

Figure 8 shows the behavior of the users of the balneary regarding the disposal of waste. Only 2.2% of the users of the balneary do not adequately dispose of the waste they generate. There was a statistically significant difference at the significance level of 5%. P-value = 0.180. This result means that the type of user and perception regarding the destination of solid waste are dependent.

If I could verify that the conscious act made the proper disposal of solid waste by the users of the Hurtado balneary shown in

Figure 8 is not in line with the reality that is present in the place, given that the environmental impact was more perceived as inappropriate generation and disposal of solid waste (

Figure 4). Hence, Evison and Read [

34] emphasize that human behavior impedes the effective execution of solid waste management strategies, necessitating a shift through environmental education. It is logical to assert that the limited understanding exhibited by survey participants regarding waste management methods and their unfavorable dispositions constitute major catalysts for waste issues. Notably, the survey participants highlighted the absence of adequate receptacle installations as a factor contributing to waste challenges (depicted in

Figure 7B). Sichaaza's comprehensive study [

35] delved into public attitudes towards solid waste management, unearthing three key themes: an absence of knowledge concerning waste reduction, classification, and composting; insufficient presence of educational and awareness initiatives; and an overall pessimistic outlook towards waste management practices. This phenomenon was observed throughout public spaces in Lusaka, the capital of Zambia, where a lack of awareness and negative attitudes towards responsible waste handling led to observable adverse outcomes. The prevalence of negative attitudes was traced back to inadequate education and issues intertwined with waste management practices.

3.8. Perception of Visitors Regarding the Conditions of the Hurtado Balneary

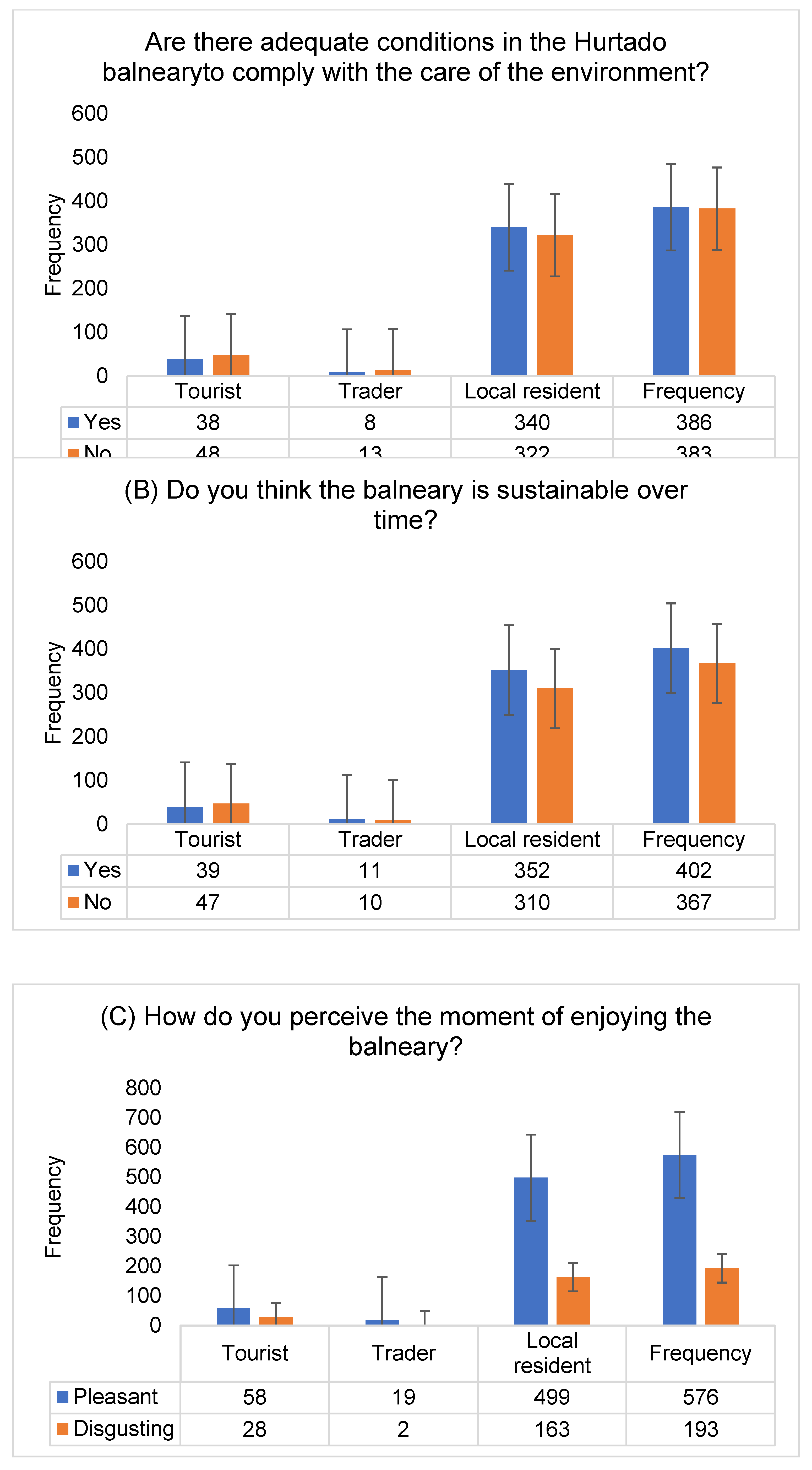

Figure 9 (A-C) shows the results of the perceptions of visitors to the Hurtado balneary regarding their conditions.

It is interesting to observe the results presented in

Figure 9 (A - B) for the differences in the percentages of the responses of the participants to the question about the conditions of the balneary if they comply or not with care for the environment and sustainability a the long of the time. There was a significant statistical difference at the significance level of 5%. P-value = 0.242. This result means that the type of user and the perceptions about the conditions of the Hurtado balneary are dependent (

Figure 9A). There was a significant statistical difference at the significance level of 5%. P-value = 0.879. This result means that the type of user and the perception regarding the sustainability of the balneary are dependent (

Figure 9B). The percentage of participants who believe in sustainability and conditions is 52.3% and 50.2%, while 47.7% and 49.8% believe they do not have sustainability and care conditions in the Hurtado balneary, respectively. 65% perceive the balneary as pleasant, while 35% consider it not (

Figure 9C). There was a significant statistical difference at the significance level at 5%. P-value = 0.069. This result means that the type of user and the perception of the spa environment are dependent.

These results are somewhat contradictory to the reality shown in

Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Evidence of the waste dumped in the Hurtado balneary.

Figure 10.

Evidence of the waste dumped in the Hurtado balneary.

Quintero-Corrales et al. [

18] showed that tourists and residents meet their physiological needs in the river, which increases the possibility of spreading some infectious diseases. Additionally, the study carried out by Martínez-García et al. [

36] revealed that the lower Guatapurí River habitat proves to be a little diverse, with a lower score concerning the Hurtado balneary area and that this low score is mainly due to tourist activity.

SDG target 6.2 necessitates the collective efforts of various stakeholders to ensure universal access to suitable drinking water, equitable sanitation, and hygiene practices while also eradicating open defecation by 2030. Given that the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) encompass three fundamental dimensions—environmental, economic, and social sustainability—the participants' responses were dissected to reveal their implications across these dimensions, which collectively form the foundational pillars of the SDGs.

Examining environmental sustainability, the scrutiny of responses, as depicted in

Figure 9 (A-C), revealed incongruities with on-site observations and

Figure 10, a collection of photographs captured by the researcher. These visuals exposed unsuitable behaviors in waste disposal, contributing to environmental degradation and the contamination of the Guatapurí River. Consequently, these actions have instigated the deterioration and depletion of biodiversity. Transitioning to economic sustainability, users' attitudes toward waste disposal carry the potential to escalate collection expenses for the Valledupar municipality. Regarding social sustainability, these behaviors can introduce environmental contamination—spanning air, soil, and water bodies—culminating in public health predicaments. A direct consequence of improper waste disposal is the onset of illnesses, impacting public health and potentially carrying socioeconomic ramifications for both the local populace and any individuals encountering the tainted surroundings.

The water right is not expressed in the Political Constitution of Colombia, however, to the extent that all human beings are guaranteed the enjoyment of their human rights, since they are universal, indivisible, and interdependent, linked to each other, belonging to the community; denotes the construction that the water right is interrelated with other rights such as: to life, to the dignity of the human person, to adequate food, to health and the environment, for which reason it needs constitutional recognition, to be True, an authentic fundamental right. For this reason, there is an intense international impulse to support the right to water for its universal recognition, whose understanding is shared by Albuquerque and Roaf [

37], who express the thought when they affirm that this right must be provided for in national Constitutions, emphasizing that the most developed legal frameworks are found in countries that explicitly recognize the rights to water and sanitation. Since national constitutions define the roles and responsibilities of all, this recognition emphasizes the national commitment to the rights of all and ensures their incorporation into national law. In addition, the recognition provides an essential reference point for policymakers, government ministries, judicial bodies, and civil society, all to influence policy, set norms, and hold political actors accountable.

3.9. Knowledge Level of the Users Concerning Solid Wastes

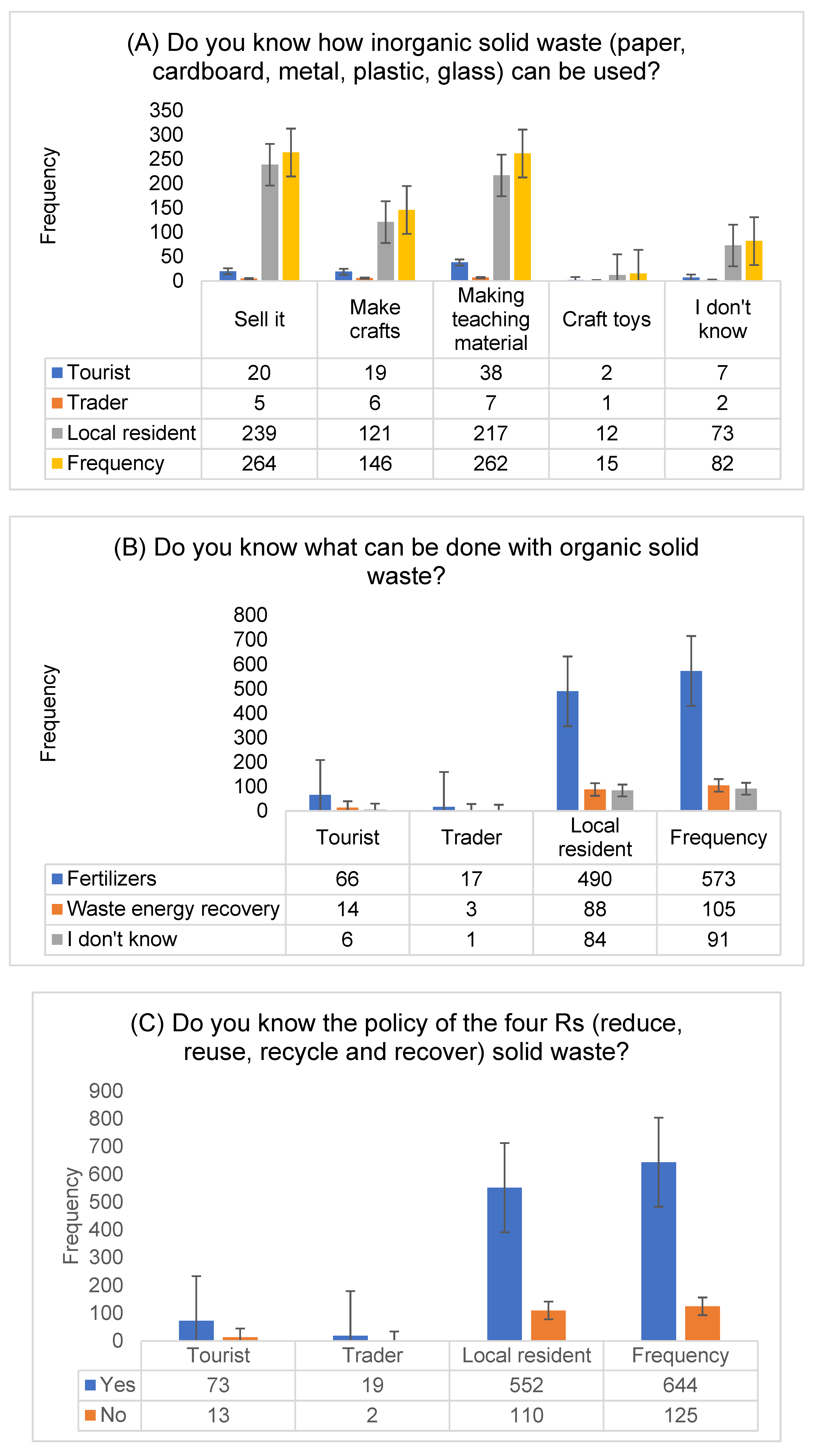

The level of knowledge of the Hurtado balneary users is presented in

Figure 11 (A–C). The option to sell (264) and make didactic material (262) were the ones that presented the highest frequency regarding the use of inorganic waste. At the same time, most of those surveyed (573) said that organic waste could be composted. There was a significant statistical difference at the significance level of 5%. P-values = 0.65 and 0.446. This finding means that the type of user and his knowledge about using inorganic and organic solid waste, respectively, are dependent. When asked about their knowledge of the 4R policy, 83.7% (647) of the respondents said they were aware (

Figure 11). There was a significant statistical difference at the significance level of 5%. P-value = 0.65. This result means that the type of user and the knowledge regarding the 4 RS policy are dependent.

These results point to the need for environmental education in the Valledupar community to generate knowledge and awareness to efficiently manage solid waste in the Hurtado balneary and the municipality. In this sense, Madrid [

38], in a study, presented a comprehensive solid waste management plan for the central market of the Canton of Esmeraldas in Ecuador, where he discusses the importance of raising awareness about the separation of solid waste for future purposes. However, the separation of waste does not make sense if there is no method of treatment and use for each waste. Arboleda [

39] presented in his dissertation a plan for the integral management of solid waste in the Gorgona National Park in Cauca, Colombia. He mentioned that visitors should be aware of the solid waste generated in the park since the park produces more waste per capita than the national average.

Ramdas and Mohamed [

40] assessed visitor and resident perceptions of the impacts of tourism on water quality in the Redang and Perhentian Islands in Malaysia using 469 questionnaires. The results showed a high level of agreement between visitors and residents regarding the water quality of both islands affected by tourism. The authors suggested establishing the carrying capacity and incorporating environmental education in sustainable tourism management to broaden visitors' perceptions.

The beaches of the island of San Andrés in Colombia had high levels of contamination by solid waste due to human activities, mainly by tourists and residents, and inadequate waste disposal [

41].

The environmental problem caused by the increase in solid waste is partly due to the lack of education and environmental responsibility to classify it as the source and reuse it as raw material for new products. Integrated solid waste management contributes to the sustainable conservation of natural resources. In the five semesters that the La Salle University Corporation developed the program, it saved more than 18 million pesos in cleaning costs and reduced the amount of waste for disposal in sanitary landfills. Other benefits include the production of compost and the sale of recycled materials [

42].

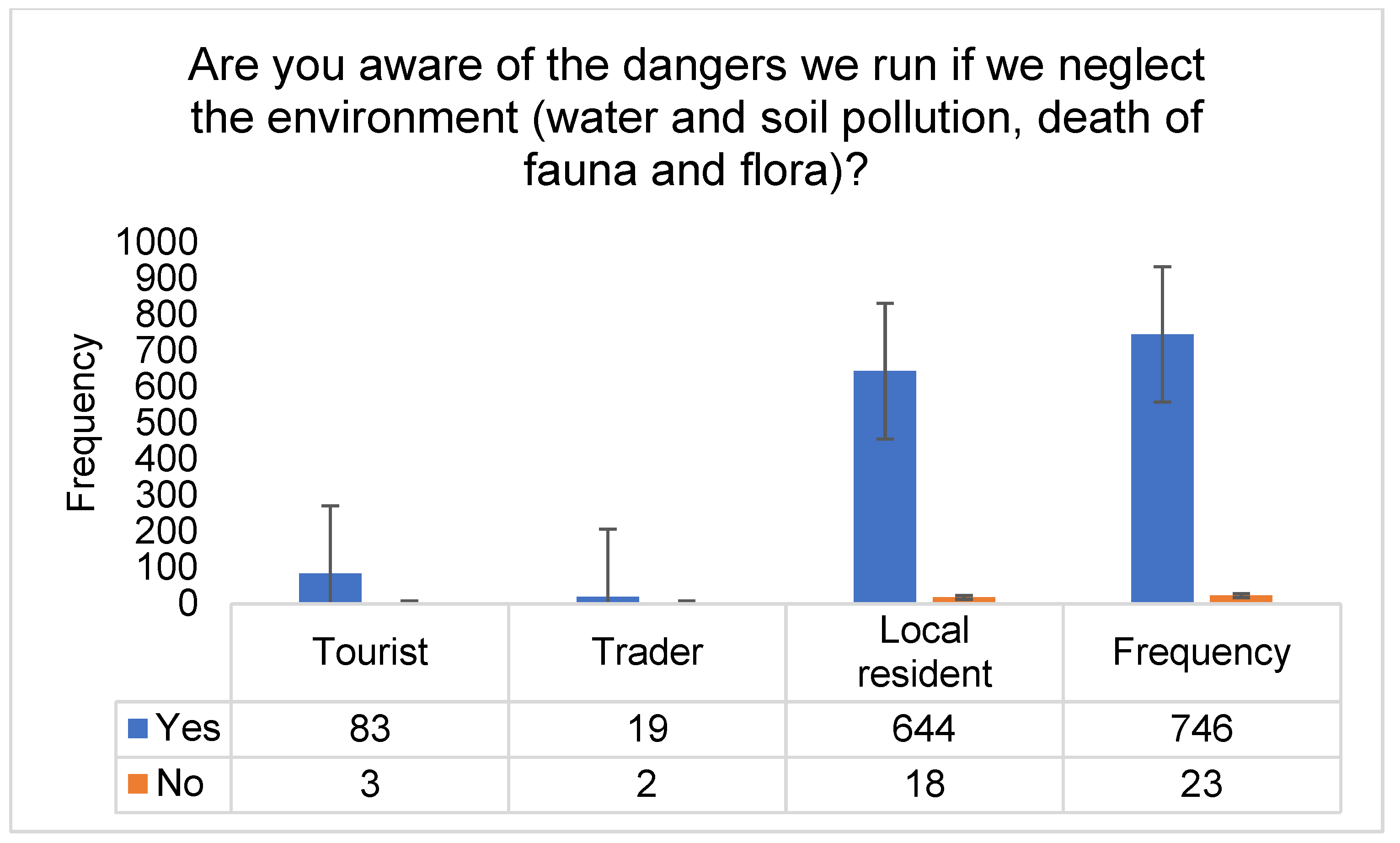

3.10. Level of Knowledge of the Respondents about the Insecurity Regarding the Contamination of Water, Soil, and Affectations of the Ecosystems of the Hurtado Balneary

The results obtained on the level of knowledge of the users of the Hurtado balneary regarding the sanitary insecurity that solid waste can generate are presented in

Figure 15. 97% of the users of the Hurtado balneary know the risks of contamination by solid waste. There was a significant statistical difference at the significance level of 5%. P-value = 0.189. This finding means that the type of user and the knowledge regarding insecurity and the risks of contamination by solid waste are dependent.

The results shown in

Figure 12 are like those of Martínez-García and Zequeira-Cuervo [

43], who observed that the impacts caused by anthropic activity in the Hurtado balneary were tourism, recreation, mismanagement of solid waste of this activity, the degradation of the riparian forest, the alteration of the banks and urbanization.

The riverside forest of the Hurtado Balneary, which presents the worst quality, is of poor quality since it presents extreme degradation. The riparian forest downstream of the Hurtado Balneary has received less impact, but compared to the riparian forest upstream, it shows a significant loss of floristic biodiversity and considerable degradation. Martínez-García and Zequeira-Cuervo [

43] have attributed the lack of environmental education and infrastructure to the poor disposal of solid waste in the Hurtado balneary. These materials are dumped into rivers by wind action or by the bathers themselves. The wind then carries these away, but a certain amount of it precipitates, allowing organic matter to decompose in the water and facilitating the formation of sludge that can favor the presence of some species of macroinvertebrates and other disease-carrying vectors that adapt to these conditions.

Additionally, solid waste production contributes to negative economic, social, and environmental effects because it reduces the tourism potential, contaminates the environment with pathogenic microorganisms, and costs public organizations money to clean up the natural environment. This money could be better used for other purposes [

44] since the negative environmental impacts generated by activities such as tourism and commerce have progressively increased waste, accompanied by poor management, which may be prone to depositing both in the Guatapurí river bed and the riparian areas and may negatively alter the physicochemical characteristics such as organic matter, solids in suspension, dissolved oxygen, pH, among others, of the areas of the Guatapurí river that are used by bathers in the Hurtado balneary [

36].

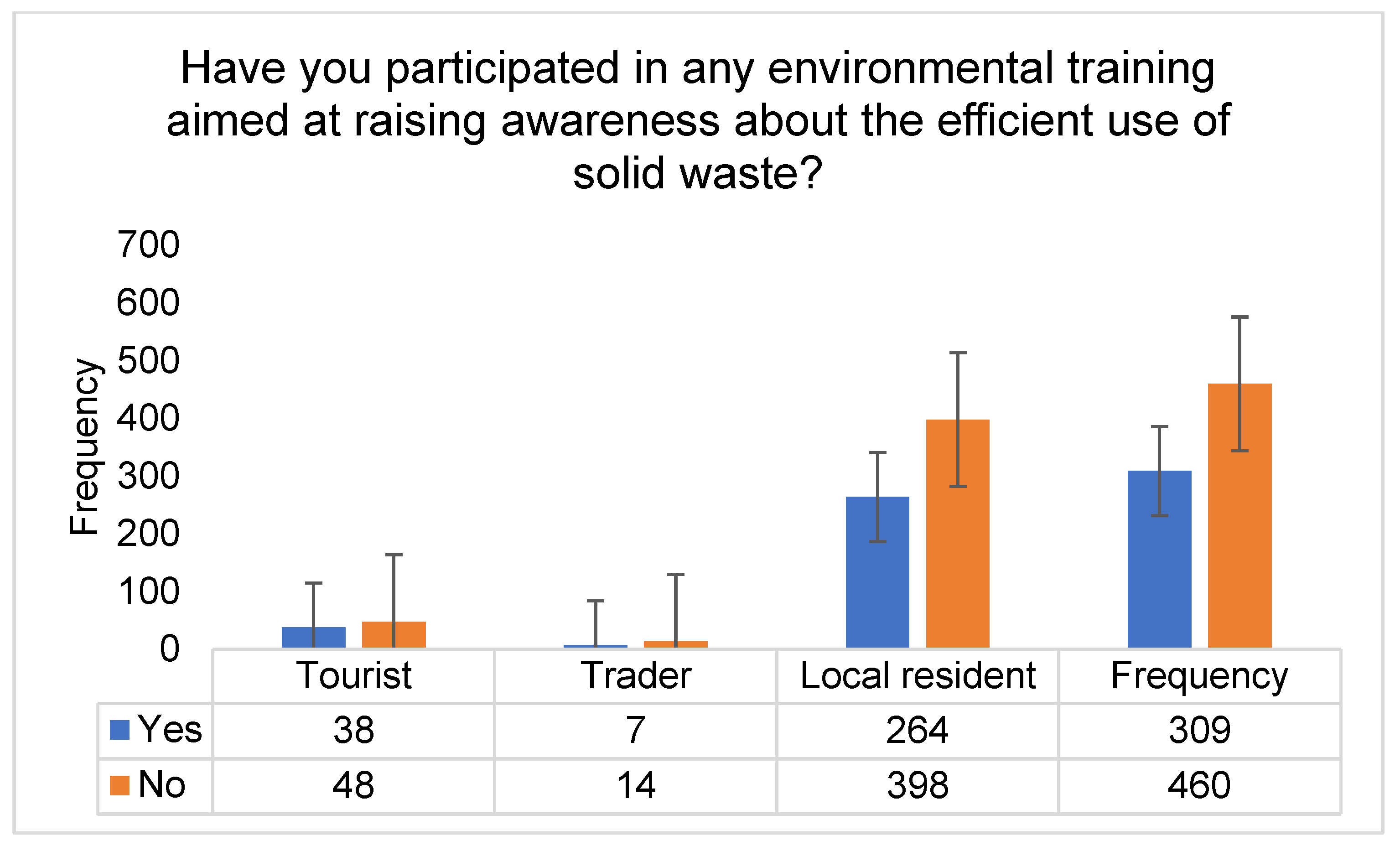

3.11. Level of Knowledge of Users Regarding the Efficient Use of Solid Waste

The results obtained on the level of knowledge of the users of the Hurtado balneary regarding training for the efficient use of solid waste are presented in

Figure 13.

59.8% of the users of the Hurtado balneary have not participated in environmental training, and 40.2% said yes. There was a significant statistical difference at the significance level of 5%. P-value = 0.603. This finding means that the type of user and the knowledge regarding the conscious use of solid waste are dependent.

This discovery carries significant weight as it underscores the imperative of initiating an environmental education initiative as the initial step. This educational program aims to heighten the community's consciousness and instill a sense of ownership [

45]. Identifying and incorporating these factors into solid waste management strategies is pivotal for fostering environmental consciousness. Such inclusion ensures the effectiveness of these initiatives, further underscoring the criticality of an interdisciplinary approach when tackling environmental issues, as demonstrated here—specifically, the realm of solid waste management within aquatic ecosystems.

Additionally, the results obtained in this section indicate that awareness and environmental education, its tools and strategies need to be incorporated into the various environmental policies, promoting citizen participation based on the construction of an environmental culture by schools and communities, which focuses on developing processes that modify the behavior of individuals [

46].

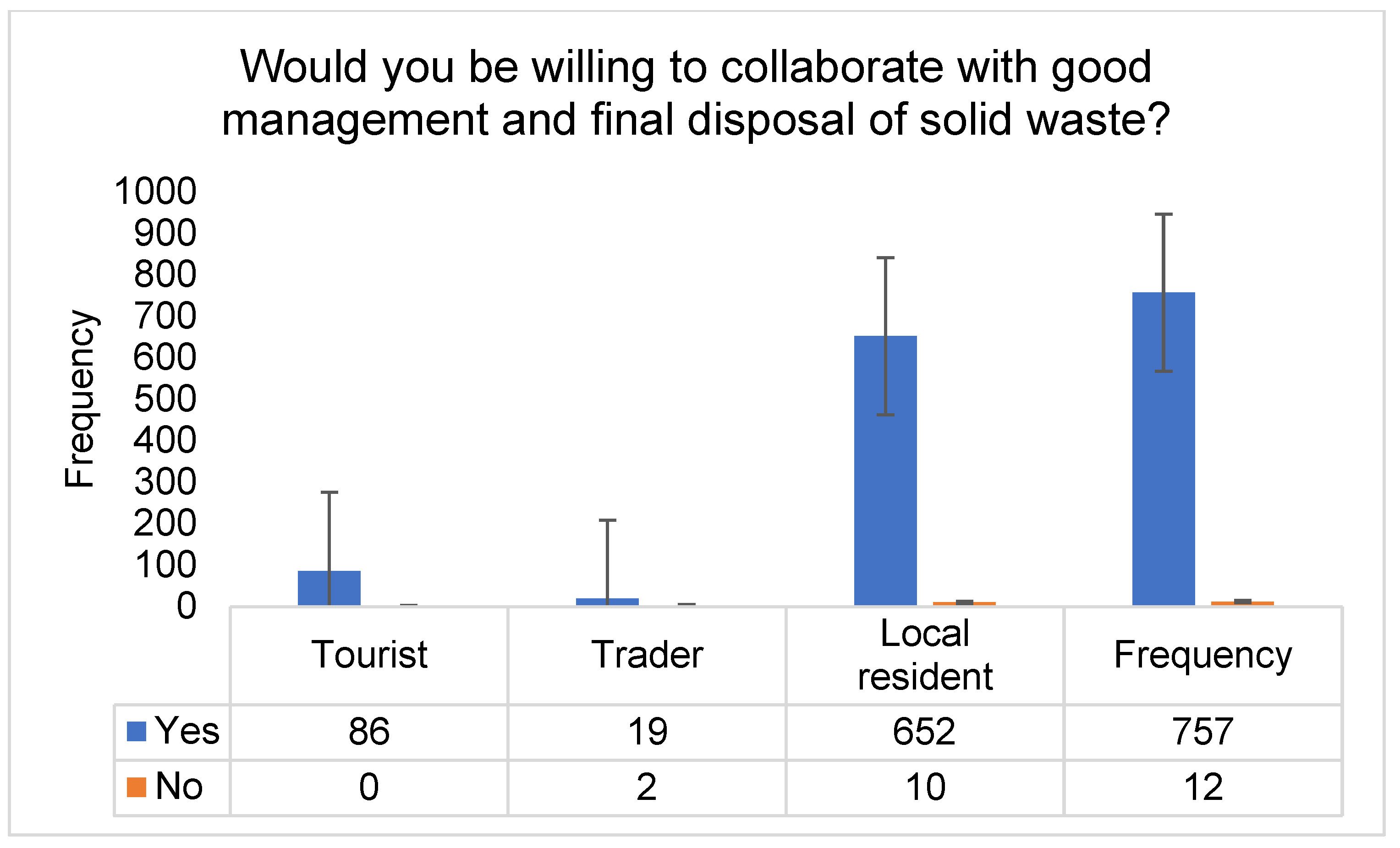

3.12. Willingness to Collaborate with Good Management and Final Disposal of Solid Waste

When the respondents were asked about their willingness to participate in improving solid waste management services, the results indicated that (98%) would be willing to collaborate with good management and final disposal of solid waste (

Figure 14).

According to the results of

Figure 14, it was possible to verify that 98% of the respondents are willing to collaborate with the good management of solid waste from Hurtado balneary. There was no statistically significant difference at the 5% significance level. P-value = 0.007. This result means that the type of user and the willingness to collaborate with the proper management and final disposal of waste are independent.

Solid waste and its management, which is everyone's responsibility, cannot be attributed solely to the responsibility of local authorities. The protagonists that generate waste must be the same people responsible for its management, that is, everyone: society, public administrations, private initiatives, and even tourists. Gradually, from the moment in which the tourist experiences are shared collectively, inserting the socio-environmental problems of the tourist destinations - which goes from the encouragement to the commitment and reciprocity with the conservation of the environment and the improvement of the quality of life of the local population - it is possible to affirm the existence of a new pattern of tourism, that is, the sustainable one.

If there are sustainable development indicators, sustainable tourism indicators, and the Comprehensive Solid Waste Management Policy in the country, which offers guidelines to be implemented, in short, a sufficient framework of information, there is no excuse for the local government of Valledupar to evade the responsibility of adequately managing the solid waste of the Hurtado balneary and encourage new practices about the management of these materials in the local community. The fact is that there are problems: an increase in solid waste due to tourist activity; the non-recycling of waste by the municipality, since only pressed materials are classified and sold; the lack of selective collection; the inefficiency of the municipal plan for comprehensive management of solid waste and the absence of the 4RS policy. However, solutions to these problems are possible through public policies and environmental education that includes tourists, residents, and city business people.

3.13. Perception of Visitors Regarding the Solid Waste Collection Services of the Balneary and CORPOCESAR's Commitment to the Guatapurí River

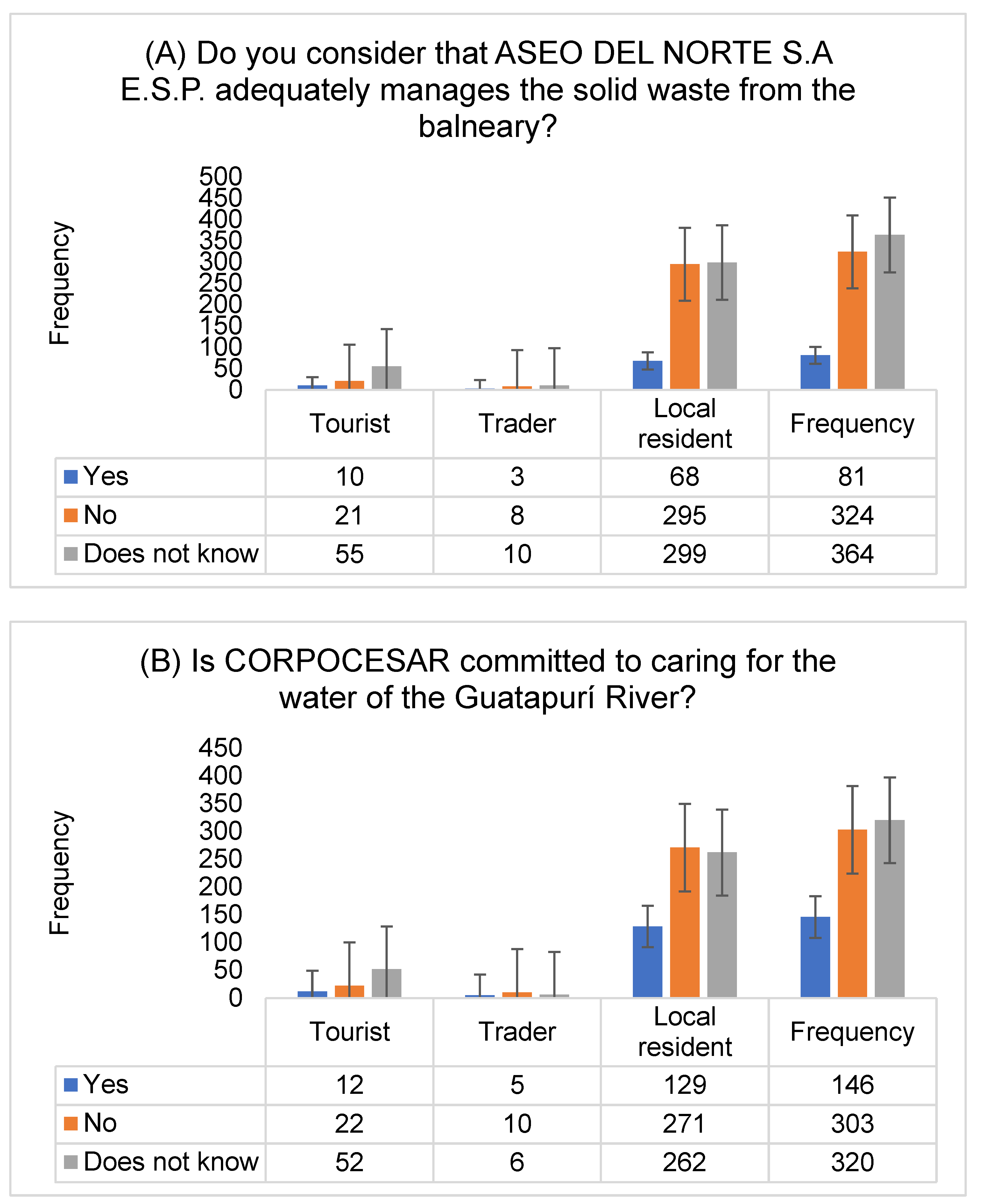

Figure 15 (A - B) shows the results of visitors' perceptions of the Hurtado balneary regarding the provision of services and the government's commitment to the Guatapurí River.

The perception of the respondents about waste management was also measured to verify the commitment to keep the balneary facilities clean by the institutions responsible for public sanitation; 364 (47.4%) said that ASEO DEL NORTE SA ESP adequately manages the solid waste from the balneary while 324 (42.1%) did not know how to answer.

There was no statistically significant difference at the 5% significance level. P-value = 0.009. This behavior means that the type of user and the perceptions regarding the cleanliness of the balneary are independent. 41.6% (320) said they do not know if CORPOCESAR is committed to caring for the water of the Guatapurí River, while 303 (39.4%) consider that it is not (

Figure 15A-B). There was a significant statistical difference at the significance level of 5%. P-value = 0.945. The null hypothesis is not rejected since the P-value is greater than the significance level. So, the type of user and the perceptions regarding the commitment of the government of Cesar are dependent.

Figure 15.

Perceptions about the solid waste collection services of the Hurtado balneary and CORPOCESAR's commitment to the Guatapurí River. The vertical bars (I) represent the standard error of 769 responses.

Figure 15.

Perceptions about the solid waste collection services of the Hurtado balneary and CORPOCESAR's commitment to the Guatapurí River. The vertical bars (I) represent the standard error of 769 responses.

User perception of environmental issues can be a better basis for planning and management so that collaboration between stakeholders can be implemented. This information is supported by Meppem [

47] and Tress and Trees [

48], who stated that dialogue sessions between managers and stakeholders are encouraged, supporting and sharing decisions.

Leff [

49] argues that sustainable development depends on ecosystem characteristics based on biological resources, environmental services, and sociocultural and political ideologies. In terms of solid waste management, an effort should be made to provide environmental services instead of logistics services that move materials from the point of waste generation to final disposal. In addition, it is necessary to pay attention to responsible consumption, respecting the balance between human activity and its impact on nature, to promote sustainable development.

Likewise, the UN body [

50] of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) sets common goals on issues such as water, air, soil, etc., to achieve better living conditions and ensure the life of future generations, respecting ecosystems. Specifically, regarding solid waste management, the Sustainable Development Goals include goal six, which aims to "guarantee access to water and its sustainable management and sanitation for all."

The effective provision of public services allows citizens to live and work in peace and contentment and promotes development. In particular, the proper management of solid waste can be a decisive factor in improving urban environmental conditions, positively affecting the environment and all the economic actors involved in this activity.

The results of behaviors and perceptions of the users of the Hurtado balneary indicated that tourist activities negatively impact the study area's environmental attributes. This evidences that the implementation of more cans, awareness campaigns, and environmental education for the community that enjoys the balneary must be included in the solid waste management plan and thus contribute to the improvement of environmental conditions, reducing insecurity regarding dangers of the contamination of water, soil, and affectations of the ecosystems of the Hurtado balneary.

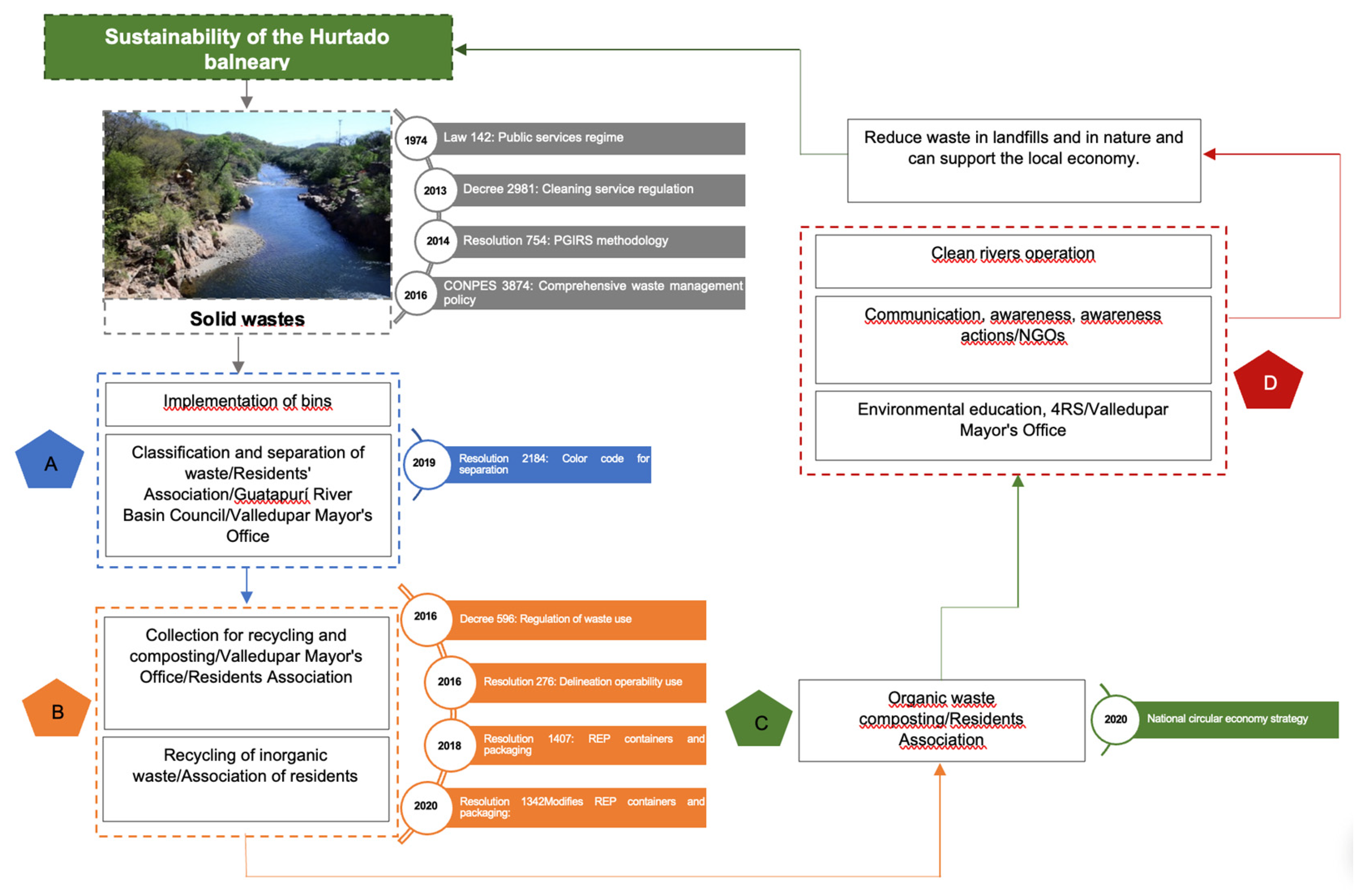

4. Solid Waste Management Plan for the Hurtado Balneary, Guatapurí River in Valledupar, Department of Cesar, Colombia

The main problems diagnosed in the Hurtado balneary through the observation and photographic record of the researcher and the answers obtained from the survey were that the bins located in the balneary are not used to deposit waste due to the lack of bins and because of user laziness. Users throw solid waste on the ground for lack of belonging and environmental education. Signage is needed for the conservation of the Guatapurí River. The company ASEO DEL NORTE SA ESP does not adequately manage the solid waste from the balneary, and CORPOCESAR is not committed to caring for the water of the Guatapurí River. So, there is a need for a solid waste management plan since the solid waste generated in the Hurtado balneary increases local waste production, which generates financial and logistical pressures for the local government of Valledupar. The average monthly cost per inhabitant is

$2,250 for collection and transportation and

$860 for final disposal. Valledupar has a population of 532,956 people, representing a monthly expense of

$1,657,493,160.00 [

51]. This cost does not include cleanup activities, which are also expensive. The municipality has limited logistics of solid waste, containers, and garbage cans available in the Hurtado balneary.

Furthermore, the 'Los Corazones' sanitary landfill in Valledupar is grappling with spatial constraints. Competent waste management not only ensures the enduring viability of the surveyed region but also plays a pivotal role in upholding the destination's allure. Benefits include income from the sale of recyclable materials, development of good community relations, odor reduction, landscape and sanitation improvements, and increased tourist satisfaction. It should be noted that regulations and strategies designed to promote greater use of waste and the formalization of recyclers must be considered before implementing a solid waste management program. The possible actions for the main activities to be carried out in the Hurtado balneary and the regulatory and planning instruments for waste management in Colombia are presented in

Figure 16.

Solid waste management services primarily include waste collection, transportation, and treatment. These services hold significant importance in maintaining the cleanliness of tourist regions, thus serving as a crucial component. Consequently, they also contribute to sustaining economic and social dynamics within tourist destinations [

52].

Figure 16.

The general model proposed for the organic and inorganic solid waste management plan in the Hurtado balneary [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62].

Figure 16.

The general model proposed for the organic and inorganic solid waste management plan in the Hurtado balneary [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62].

This management plan aims to recover, take advantage of, and value solid inorganic and organic waste. This operation requires a prior classification of waste at the Hurtado balneary to separate recyclable fractions and organic waste. They are making it necessary to implement more cans. These may oversee the residents' association, the Guatapurí River Basin Council, and the Valledupar mayor's office (

Figure 16, point A). The latter will be responsible for financing and organizing solid waste management activities. The city mayor's office could collaborate with the collection companies and recyclers, additionally control and monitor the system, as well as establish collection objectives for recycling and composting to be respected by the residents' association that will be the operator of the system (

Figure 16, point B).

Organic solid waste poses a challenge for municipal and local entities as it escalates collection and treatment expenses. Additionally, it contributes to CO

2 emissions and leachate generation within landfills. Notably, proper source-based sorting could recover this waste through composting. This technical approach primarily aims to mitigate an existing issue rather than generate composting-based revenue. The resultant compost could serve agricultural needs within Valledupar municipality (

Figure 16, point C). A well-defined strategy called "Operation Clean Rivers" is suggested to execute this, targeting effective communication, awareness, and infrastructure for source-level waste segregation. In the context of the Hurtado balneary, this role could be effectively played by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) for communication and awareness initiatives, along with local authorities such as the Valledupar mayor's office, which can facilitate an environmental education and 4Rs training program (reducing, reusing, recycling, recovering) (

Figure 16, point D). This holistic solution can potentially augment the local collection of recyclable materials, consequently minimizing their presence in landfills and natural settings while bolstering the local economy.

River and garbage do not mix! Solid waste contamination can remain on the banks of the Guatapurí River for a long time, generating soil and water contamination, affecting aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, proliferating disease-causing vectors, and putting human health at risk. The cleanliness of the balneary should receive special attention from all the actors throughout the year. For traders, residents, and tourists, communication and awareness campaigns with various slogans, signs, and awareness guidelines are needed.

Ensuring the sustainability of pristine rivers necessitates key components such as active engagement, effective leadership, strategic planning, and prudent governance. Introducing awareness initiatives targeting visitors at Hurtado Balneary can assume a pivotal role in ensuring the pristine state of the region while facilitating the recovery of recyclable materials and the composting of organic waste.

The main objectives of the solutions proposed for the management of solid waste in the Hurtado balneary are to improve the efficiency of waste management activities (proper disposal, collection, recycling, and cleaning); create new employment opportunities, and support the economic sector (recyclers, composters, and agriculture); minimize waste to landfill, thus reducing CO2 emissions.

Nonetheless, implementing viable alternatives for sustainable solid waste management within the balneary necessitates a multifaceted approach. Alongside this, it is imperative to develop a robust infrastructure for recycling inorganic solid waste, adopt source separation practices to curtail waste generation and sustain an ongoing regimen of awareness and education targeting diverse waste contributors. The engagement of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) can further fortify the sustainable framework of the Hurtado balneary.

Several recommendations can be proposed to enhance the solid waste management at the balneary. The effectiveness of solid waste management models can be improved by establishing diverse initiatives such as training programs and awareness campaigns to bolster the technical and environmental expertise of municipal staff. Moreover, addressing the lack of professional knowledge and experience among local and national authorities and waste management personnel could be tackled through specialized training endeavors for decision-makers and other stakeholders. Such efforts could facilitate the exchange of best practices with international entities and countries.

Emphasizing public education and sensitizing residents while fostering comprehensive communication with all stakeholders is pivotal. By doing so, active participation in the waste management process is ensured. Implementing waste sorting at the source and segregation and separation of waste can significantly diminish waste generation and reduce associated costs in collection, transportation, and landfill management. This approach can contribute to a surplus of clean, recyclable materials, fostering new economic avenues and employment prospects.

Enhancements are essential for augmenting the budget allocated to solid waste management activities within tourist destinations. Primarily, fostering collaboration among all stakeholders within the waste management sector of tourist municipalities holds the potential to address numerous challenges by distributing financial responsibilities across various partners. This collaborative approach could alleviate the financial burden on the municipality.

Integration of waste collectors is a pivotal facet in establishing a comprehensive and sustainable solid waste management framework in the Hurtado balneary, particularly concerning material recovery operations. Exploring the integration of waste collectors within this framework aims to enhance waste recovery processes and facilitate the working conditions of collectors.

The government should actively promote alliances and cultivate models for solid waste management in aquatic environments centered on waste reduction, reuse, recycling, recovery, and composting. Moreover, the government should bolster companies and communities through initiatives like pilot projects, financial support, training, technical assistance, information exchange, and continuous monitoring. For instance, the municipality can stimulate small-scale private composting endeavors by forming contracts to secure the product for 3 to 5 years for application in municipal or private undertakings. Using regulations, rigorous enforcement, and the establishment of economic incentives, the government can stimulate improved waste management practices and facilitate market creation to ensure effective waste collection and recycling. Educational initiatives should also be focal points, including organizing conferences, seminars, and workshops, publishing training materials, showcasing case studies best practices, and offering technical and financial aid.

The Department of Cesar's government is advised to adopt a dual-pronged approach, encompassing "bottom-up" and "top-down" strategies. The "bottom-up" approach, crucially, entails the rejuvenation of the 'Los Corazones' sanitary landfill in Valledupar. Conversely, the "top-down" strategy revolves around source waste minimization, valorization, and pre-treatment before disposal. While this approach demands more time and effort, its comprehensive impact is paramount.

5. Conclusions

The study delved into the multifaceted impacts of tourist activities on the Hurtado balneary's environment, shedding light on how tourist behaviors exacerbate not only the balneary's ecological challenges but also those of the Guatapurí River. Through a comprehensive investigation, it became evident that solid waste mismanagement prevails within the Hurtado balneary, with improper waste disposal being a prominent concern.

The survey conducted as part of this study aimed to capture tourist perceptions, behaviors, and knowledge concerning environmental impact. The outcomes underscored tourists' belief in the substantial adverse effects of tourism-related activities, development, and infrastructure on the environment. This scenario underscores the heightened awareness and concern among tourists about the ecological consequences of their actions.

The strategies recommended for creating a solid waste management plan for the Hurtado balneary address the problematic waste disposal practices that result in negative environmental and social outcomes. The study found a lack of awareness, ownership, and education among the local population regarding proper waste disposal. This deficiency leads to mismanaged organic and inorganic solid waste within the balneary, as observed by the researcher's fieldwork and survey results.

Implementing the proposed solid waste management plan, including awareness campaigns and environmental education for the Valledupar community, offers a promising avenue for enhancing the balneary's condition. Effective signage and user-friendly waste bins are vital components. Installing warning signs in areas prone to uncivil behavior can also foster improved visitor conduct.

Infusing environmental education into the tourist experience can pave the way for positive action. Environmental education can foster a positive attitude toward the environment among tourists, making it a pivotal aspect of sustainable solid waste and tourism management.

It's important to acknowledge that the research was limited to the interviewees' perspectives rather than relying on purely scientific data or mathematical models. The study, conducted during peak tourist periods, experienced limitations inherent to cross-sectional research, which focused on weekend visitors facing heightened pollution and environmental disturbances.

The findings from this study are anticipated to extend beyond the Hurtado balneary, offering insights for better solid waste management practices in similar aquatic settings. Future research could replicate this study to validate data applicability and compare outcomes in diverse tourist destinations. Moreover, this research aligns with Sustainable Development Goals 12, 13, and 15, reflecting its contribution to broader global sustainability objectives.

6. Recommendations

Stronger regulatory measures need to be put in place by local, regional, and national governing bodies to ensure rigorous environmental practices. This practice should involve the development of comprehensive management plans and efficient programs that empower both public and private entities to take swift actions in enhancing environmental stewardship within the balneary's premises.

Deploying informative signage across the Hurtado balneary is recommended to effectively curb issues. These visual aids can delineate proper conduct within the ecosystem, minimizing adverse impacts on the natural environment. Furthermore, these signs can educate visitors on the appropriate handling and disposing solid waste, fostering responsible behavior.

Augmenting the number of waste receptacles in colors denoting different types of waste—black, white, and green—can significantly enhance the visual aesthetics and reputation of the balneary. This approach would simultaneously safeguard precious natural resources while elevating the overall ambiance.

Incorporating environmental education into the curriculum of educational institutions at all levels, in collaboration with the Ministry of Environment and Tourism, is pivotal. This initiative can kindle voluntary engagement and instill a sense of responsibility among students to actively contribute to the upkeep of the balneary. It also aids in fostering a collective ethos of respect and admiration for these vulnerable natural spaces, which would otherwise be subject to degradation.

The forthcoming research could delve more deeply into aquatic life's material and daily intricacies, specifically focusing on the sustainability of the Guatapurí River. This approach necessitates the inclusive involvement of all stakeholders in decision-making processes, recognizing their integral roles in shaping the river's fate. The perspectives and insights of decision-makers, which were not covered in this study, warrant attention, warranting a comprehensive investigation to outline comprehensive strategies for holistic solid waste and tourism management.

Author Contributions

Nataylde Gutiérrez Vargas: Investigation, Data curation. Brayan Caballero and Esteban Ochoa: Methodology, Data curation. Karen Muñoz Salas: Writing and correction. Alcindo Neckel and Hugo Hernández Palma: Original draft preparation. Guilherme Luiz Dotto: Writing Reviewing. Claudete Gindri Ramos: Supervision and support in analyzes.

Data Availability Statements

It does not apply to that specific section.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Biodata

Nataylde Gutiérrez Vargas: Occupational Health and Safety Management Specialist. Brayan Caballero: Student of the undergraduate course in Environmental Engineering at Universidad de la Costa (CUC).

Esteban Ochoa: Student in the undergraduate course in Environmental Engineering at Universidad de la Costa (CUC).

Karen Muñoz Salas: Administrative coordinator of the master's degree in Sustainable Development Universidad de la Costa (CUC).

Alcindo Neckel: Bachelor's degree in Geography. He is a permanent professor at Atitus Education and in the Postgraduate Program in Architecture and Urbanism (PPGARQ-IMED). Additionally, he is a Research Productivity fellow of the Meridional Foundation. He leads the Research Groups on Society, Environment, and Urban Environmental Impacts and the Center for Studies and Research in Urban Mobility (NEPMOUR) at the Meridional Faculty. Neckel has extensive experience as an evaluator and Editor in various academic journals and works in Urban and Regional Planning, Urban Environmental Impacts, Environmental Assessment, Solid Waste, Water Resources Management, Remote Sensing, and Geoprocessing.

Hugo Hernández Palma is a doctoral student in project management from the School of Business Administration - EAN, a doctorate in energy engineering at the University of the Coast, and a senior researcher at the Ministry of Science and Technology with a master's degree in management systems. Also, he is a specialist in Construction Intervention and Supervision, Project Management, Pedagogical Studies, and Project Design and Evaluation. He currently works as an undergraduate and graduate university professor.

Guilherme Luiz Dotto: Professor at the Department of Chemical Engineering at the Federal University of Santa Maria (DEQ/UFSM). He is a CNPq research productivity fellow, level 1 D, around Chemical Engineering. He works as a permanent professor of the Postgraduate Program in Chemical Engineering (PPGEQ / UFSM) (where he was coordinator from 03/2019 to 12/2022) and also as a permanent professor of the Postgraduate Program in Chemistry (PPGQ / UFSM). He has a degree in Food Engineering (2008), a master's degree (2010), and a doctorate (2012) in Food Engineering and Science from the Federal University of Rio Grande (FURG-RS). He works in transport phenomena, unit operations, liquid effluent treatment, particulate systems, and separation processes. Specifically, he has experience in adsorption, biosorption, and drying operations. In these areas, he has more than 400 articles published in indexed journals and is a reviewer for more than 120 international journals, for which he has issued more than 1,000 opinions since 2011. Since 2012, he has been a member of the editorial board of important journals in publishers such as Springer, Elsevier, and Taylor & Francis. Between 2016 and 2018, he served as Editor of the journal Environmental Science and Pollution Research-Springer. He served as Associate Editor of Chemical Engineering Communications-Taylor & Francis in 2017 and 2018. He served as Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering-Elsevier from 2018 to 2021. He is currently the Editor of Environmental Science and Pollution Research-Springer. He also has experience in organizing scientific events in the field of Chemical Engineering, being president of the organizing committee of the 12th Brazilian Meeting on Adsorption (EBA 12) (2018) and president of the organizing committee of the 23rd Brazilian Congress of Chemical Engineering (COBEQ) (2021).

Claudete Gindri Ramos: Graduate in Chemistry, master's in environmental Impact Assessment (Unilasalle, Brazil). PhD in Engineering (Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil) and Postdoctoral Degree in Geosciences (Universidade Federal do Pará, Brazil). Full Professor at the Universidad de la Costa, Colombia. Junior Researcher recognized by MINCIENCIAS – Colombia. Leader of the Research Group on Sustainable Industrial Processes of the Civil and Environmental Department of the Universidad de la Costa recognized as A by MINCIENCIAS. Publications manager of the Civil and Environmental Department of the Universidad de la Costa. Associate Editor of Frontiers in Climate Magazine, Negative Emission Technologies. With more than 11 years of experience in research, intervention, and innovation in the environmental area at the inter-institutional and international collaboration level, as well as in the publication of high-impact scientific articles, on topics such as the use of mineral by-products as agricultural inputs, exploitation of agro-industrial waste as adsorbents of water contaminants, environmental toxicology and sustainable development. With experience in supervising doctoral, master's and undergraduate theses. Member of research groups such as Rock Flour Research Group and Mineralogy of Soils and Sediments in a Subtropical Climate and Associated Properties of the National Research Council of Brazil.

References

- World Travel and Tourism Council: World, Transformed-January 2019. Disponible en: https://wttc.org/.

- Cheng, W.; Zhang, Y. Research on the impact of tourism development on regional ecological environment and countermeasure based on big data. Technol. Bull. 2017, 55, 464–470. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Cao, J.; Hu, H.; Yu, P. The influence of environmental background on tourists' environmentally responsible behaviour. Journal of environmental management 2019, 231, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Dai, J.; Dewancker, B. J.; Gao, W.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Y. Impact of Situational Environmental Education on Tourist Behavior—A Case Study of Water Culture Ecological Park in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 11388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, F. (2011, August). Notice of Retraction: Review of studies on environmental impacts of tourism waste. In 2011 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Management Science and Electronic Commerce (AIMSEC) (pp. 6369-6372). IEEE.

- Sisneros-Kidd, A. M.; D’Antonio, A.; Monz, C.; Mitrovich, M. Improving understanding and management of the complex relationship between visitor motivations and spatial behaviors in parks and protected areas. Journal of Environmental Management 2021, 280, 111841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, D. Littering in protected areas: a conservation and management challenge–a case study from the Autonomous Region of Madrid, Spain. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2012, 20, 1011–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valledupar. (2020). Valledupar en Orden 2020 – 2023” Plan de Desarrollo Municipio de Valledupar. Disponible en: https://www.valledupar-cesar.gov.co/MiMunicipio/ProgramadeGobierno/PLAN%20DE%20DESARROLLO%20VALLEDUPAR%20EN%20ORDEN%202020%20-%202023.pdf.

- Khatri, N.; Tyagi, S. Influences of natural and anthropogenic factors on surface and groundwater quality in rural and urban areas. Frontiers in life science 2015, 8, 23–39, Ley 23 del 19 de diciembre de 1973, "Código de Recursos Naturales y de Protección al Medio Ambiente", DO: 34.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, I. D.; Croft, D. B.; Green, R. J. Nature conservation and nature-based tourism: A paradox? . Environments 2019, 6, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J. Environmental Education in the 21st Century: Theory, Practice, Progress and Promise; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, D.C. Testing for competence rather than for" intelligence.". American psychologist 1973, 28, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelsen, G.; Fischer, D. (2017). Sustainable Development Policy. Routledge; London, UK. Sustainability and education; pp. 135–158.

- Otto, S.; Kaiser, F. G.; Arnold, O. The critical challenge of climate change for psychology: Preventing rebound and promoting more individual irrationality. European Psychologist 2014, 19, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras del Vecchio, D. (2022). Análisis integrado de percepciones para un plan de manejo del arroyo El Salao II en Barranquilla, Colombia. Corporación Universidad de la Costa.

- De Young, R. New ways to promote proenvironmental behavior: Expanding and evaluating motives for environmentally responsible behavior. Journal of social issues 2000, 56, 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias Filho, M.; Silva-Cavalcanti, J. S.; Araujo, M. C. B.; Silva, A. C. M. Avaliação da percepção pública na contaminação por lixo marinho de acordo com o perfil do usuário: estudo de caso em uma praia urbana no Nordeste do Brasil. Revista de Gestão Costeira Integrada-Journal of Integrated Coastal Zone Management 2011, 11, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Corrales, A.; Fragoso-Castilla, P. J.; Olivieri, G. F. Calidad bacteriológica del agua de cuatro balnearios del municipio de Valledupar (Colombia). Información tecnológica 2021, 32, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MADS. (2019). Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible. Resolución 2184 de 2019. “Por la cual se modifica la resolución 668 de 2016 sobre el uso racional de bolsas plásticas y se adoptan otras disposiciones”.

- Benez, Mara Cristina., Kauffer -Michel, Edith F.; Álvarez- Gordillo, Guadalupe del Carmen. (2010). Percepciones ambientales de la calidad del agua superficial en la microcuenca del río Fogótico, Chiapas Frontera Norte, vol. 22, núm. 43, enero-junio, pp. 129–158.

- Hernández-Solorzano, Sergio (2018). Análisis de la percepción en la contaminación de arroyos urbanos en la microcuenca el Riíto en Tonalá Chiapas, México. Tesis presentada para obtener el grado de Maestro en Gestión Integral del agua. Monterrey, N. L.; México. 109 p.

- Valera, S. Gestión ambiental e intervención psicosocial. Psychosocial Intervention 2002, 11, 289–301. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado, J. (2012). The research project Holistic understanding of methodology and research. Seventh edition. Quiron and Sypal editions. Caracas. Venezuela.

- Chapelle, S.; Gouin, S.; 2015. Observatoire des Multinationales. Disponible en: http://multinationales.org/Dechets-la-face-cachee-du-tourisme-de-masse-en-Tunisie.

- Karanja, A. (2005). Solid Waste Management in Nairobi: Actors, Investment Arrangements and Contribution to Sustainable Development, PhD Dissertation, ISS.

- Lopes, M. M.; Cornelian, A. R. A percepção ambiental de turistas, veranistas e moradores de Peruíbe/SP. Revista Brasileira Multidisciplinar-ReBraM 2017, 20, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DANE. (2018). DEPARTAMENTO ADMINISTRATIVO NACIONAL DE ESTADÍSTICA. Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda de 2018. Disponible en: https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/demografia-y-poblacion/censo-nacional-de-poblacion-y-vivenda-2018/cuantos-somos.

- Silva, T. S. N.; Souza, C. F. Percepção dos impactos do Turismo pelos moradores da Praia do Farol-Ilha de Cotijuba/PA. Revista Brasileira de Gestão e Desenvolvimento Regional 2013, 9.

- Santana-Neto, S. P.; Silva, I. R.; Cerqueira, M. B.; Tinoco, M. S. Socioeconomic profile of beach users and awareness on marine pollution by litter: Porto da Barra beach, BA, Brazil. Journal of Integrated and Coastal Management 2011, 11, 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Farias, S. C. G. Acúmulo de deposição de lixo em ambientes costeiros: a praia oceânica de Piratininga–niterói–RJ. Geo UERJ 2014, 2, 276–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, C. N. V.; da Cunha, S. L.; Silveira, T. C. Percepção ambiental e a prática docente nas escolas do meio rural do município de Itapetinga-BA. REMEA-Revista Eletrônica do Mestrado em Educação Ambiental 2009, 23.

- Silva, F. G. S. D.; Silva Filho, F. P. D.; Oliveira, D. S. D.; Dias, H. D. S.; Silva, E. G. D. A. A Educação Ambiental como instrumento de gestão turística sustentável na Praia da Pedra do Sal, Parnaíba (Piauí). Revista Brasileira de Gestão Ambiental e Sustentabilidade 2016, 3, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhtar, S. Z.; Amirah, A. S. N.; Ab Wahab, M.; Hassan, Z.; Hamid, S. (2021). Study of environmental awareness, practices and behaviours among UniMAP students. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (Vol. 646, No. 1, p. 012061). IOP Publishing.

- Evison, T.; Read, A. D. Local Authority recycling and waste—awareness publicity/promotion. Resources, conservation and recycling 2001, 32, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sichaaza, H. M. (2011). An assessment of knowledge, attitudes and practices towards waste management among Ng'ombe residents (Doctoral dissertation). http://dspace.unza.zm/handle/123456789/515.

- Martínez-García, N.; Royero-Ibarra, A.; Navarro-Sining, B.A.; Torres-Cervera, K.P.; Cahuana-Mojica, A.; Herrera-Martínez, J.R. Determinación de los índices BMWP/COL,(QBR),(IHF) e ICO en Valledupar, Colombia. Revista Politécnica 2022, 18, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, C.; Roaf, V. (2012). Derechos hacia el final: buenos prácticas en la realización de los derechos del agua y al saneamiento. ONGAWA. Disponible en: https://sr-watersanitation.ohchr.org/pdfs/BookonGoodPractices_sp.pdf.

- Madrid León, V. E. (2012). Plan de Manejo Integral de Residuos Sólidos del Mercado Central del Cantón Esmeraldas (Bachelor's thesis, Escuela Superior Politécnica de Chimborazo).

- Arboleda Montaño, N. (2009). Programa de manejo integral de residuos sólidos en el parque nacional natural Gorgona, Cauca, Colombia. Disponible en: https://repositorio.utp.edu.co/server/api/core/bitstreams/771afae6-9de0-455b-9135-73a9fcc12666/content.

- Ramdas, M.; Mohamed, B. Perceptions of visitors and residents on impact of tourism activities towards quality of water in Redang and Perhentian Islands, Malaysia. Asian Journal of Technical Vocational Education and Training 2017, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Portz, L.; Manzolli, R. P.; Herrera, G. V.; Garcia, L. L.; Villate, D. A.; do Sul, J. A. I. Marine litter arrived: Distribution and potential sources on an unpopulated atoll in the Seaflower Biosphere Reserve, Caribbean Sea. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2020, 157, 111323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castrillón Quintana, O.; Puerta Echeverri, S. M. Impacto del manejo integral de los residuos sólidos en la corporación universitaria lasallista Revista Lasallista de Investigación, vol. 1, núm. 1, junio, 2004, pp. 15–21 Corporación Universitaria Lasallista Antioquia, Colombia. Revista lasallista de Investigación 2004, 1, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-García, N.; Zequeira-Cuervo, Á. A. (2018). Evaluación del recurso hídrico del balneario Hurtado, río Guatapurí, determinada a través de macroinvertebrados acuáticos implementando índices biológicos y fisicoquímicos. Disponible en: https://repository.usta.edu.co/handle/11634/13864.

- Moore, C. J. Synthetic polymers in the marine environment: a rapidly increasing, long-term threat. Environmental research 2008, 108, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, A.; Idris, O. Changes in the environmental perception, attitude and behavior of participants at the end of nature training projects. Environmental Engineering and Management Journal 2014, 13, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MADS. (2015, January 25). Minambiente promueve programa que pretende revolucionar la educación ambiental en Colombia | Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible. https://www.minambiente.gov.co/index.php/noticias-educacion-ambiental/1638-minambiente-promueve-programa-que-pretende-revolucionar-laq-educacion-ambiental-en-colombia.

- Meppem, T. The discursive community: evolving institutional structures for planning sustainability. Ecological Economics 2000, 34, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tress, B.; Tress, G. Scenario visualisation for participatory landscape planning—a study from Denmark. Landscape and urban planning 2003, 64, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leff, Enrique (1995). ¿De quién es la naturaleza? Sobre la reapropiación social de los recursos naturales. En: Gaceta Ecológica, n.o 37, p. 28-35.

- UN (2017). Objetivo 6: Agua limpia y saneamiento. Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo. Disponible en: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/es/home/sustainable-development-goals/goal-6-clean-water-and-sanitation.html.

- Valledupar (2022). Alcaldía del Municipio de Valledupar. Disponible en: https://www.valledupar-cesar.gov.co/MiMunicipio/Paginas/Galeria-de-Mapas.aspx.

- Lakioti, E. N.; Moustakas, K.; Komilis, D. P.; Domopoulou, A. E.; Karayannis, V. G. Sustainable solid waste management: Socioeconomic considerations. Chemical Engineering Transactions 2017, 56, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law 142. (1994). By which the regime of home public services is established and other provisions are dictated. https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=2752#:~:text=Asegurar%20que%20se%20presten%20a,la%20administración%20central%20del%20respectivo.

- Decree 2981. (2013). By which the provision of the public toilet service is regulated. https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=56035.

- Resolution 754. (2014). By which the methodology is adopted for the formulation, implementation, evaluation, monitoring, control and updating of Comprehensive Solid Waste Management Plans. https://www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=64163.

- CONPES 3874. (2016). National Policy for the Comprehensive Management of Solid Waste. https://www.minambiente.gov.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/conpes-3874-de-2016.pdf.

- Resolution 2184. (2019). By which resolution 668 of 2016 on the rational use of plastic bags is modified and other provisions are adopted. https://medioambiente.uexternado.edu.co/resolucion-2184-de-2019-por -which-resolution-668-of-2016-on-the-rational-use-of-plastic-bags-is-modified-and-other-provisions-are-adopted/.

- Decree 596. (2016). By which Decree 1077 of 2015 is modified and added in relation to the scheme of the activity of use of the public cleaning service and the transitional regime for the formalization of professional recyclers, and other regulations are issued. provisions. https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=69038.

- Resolution 276. (2016). Official Gazette No. 49,866 of May 7, 2016. Ministry of Housing, City and Territory. By which the guidelines of the operational scheme of the activity of using the public cleaning service and the transitional regime for the formalization of professional recyclers are regulated in accordance with the provisions of Chapter 5 of Title 2 of part 3 of Decree number 1077 of 2015 added by Decree number 596 of April 11, 2016. https://normas.cra.gov.co/gestor/docs/resolucion_minviviendact_0276_2016.htm.

- Resolution 1407. (2018). By which the environmental management of paper, cardboard, plastic, glass, metal packaging waste is regulated and other determinations are made. https://www.minambiente.gov.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/resolucion-1407-de-2018.pdf.

- Resolution 1342. (2020). Official Gazette No. 51,541 of December 28, 2020. Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development. By which Resolution 1407 of 2018 is modified and other determinations are made. https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/sites/default/files/Normograma/docs/resolucion_minambienteds_1342_2020.htm.

- National Circular Economy Strategy. (2020). https://www.minambiente.gov.co/asuntos-ambientales-sectorial-y-urbana/estrategia-nacional-de-economia-circular/.

Figure 1.

Extension of the Guatapurí River Google Earth Pro, 2022.

Figure 1.

Extension of the Guatapurí River Google Earth Pro, 2022.

Figure 2.

Conditions such as the Hurtado balneary on weekends where the presence of solid waste on the banks of the balneary is evident.

Figure 2.

Conditions such as the Hurtado balneary on weekends where the presence of solid waste on the banks of the balneary is evident.

Figure 3.

Container for waste disposal that is full.

Figure 3.

Container for waste disposal that is full.

Figure 4.

Panorama of the conditions of the Hurtado balneary.

Figure 4.

Panorama of the conditions of the Hurtado balneary.

Figure 5.