Submitted:

18 October 2023

Posted:

19 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

The benefits of HSW

Strategy and HSW

2. Literature Review

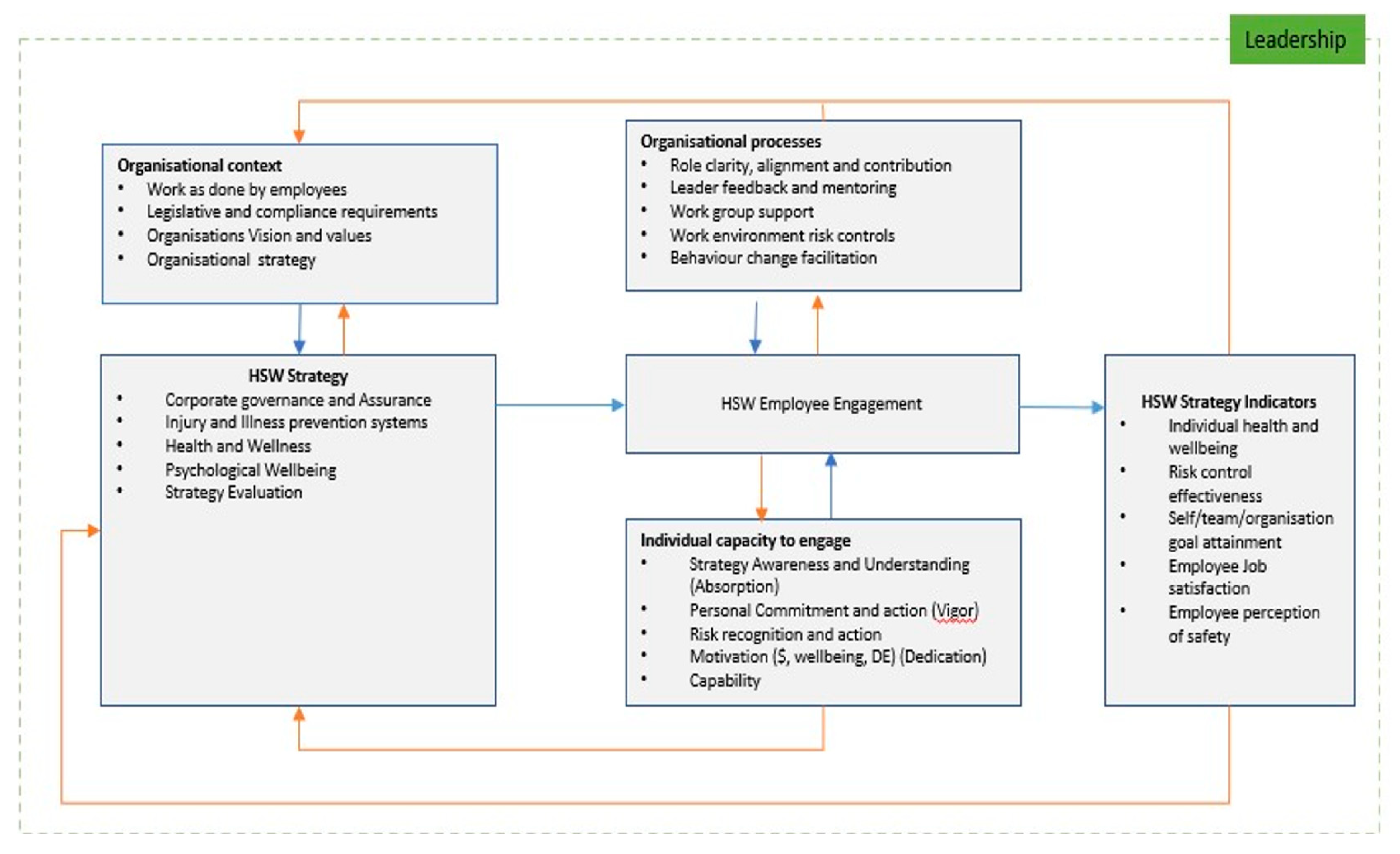

- Organisational strategy. Discussion on strategy formulation in the literature suggests that it is a complex process comprising cognitive, behavioral, social, and technical dimensions [43]. A prominent theory of strategy formulation extensively reported in the literature associated with HSW is the resource-based view (RBV) with significant contributions coming from the work of Barney[44], Prahalad and Hamel[45] and recently Miller [46]. RBV adopts an “inside-out” view by focusing on the internal capabilities of the organization, tangible and intangible resources and core competencies to be competitive and sustainable [47]. Strengths of RBV include that it provides the initial direction for the organization and defines the resources required as “inputs” that enable an organization to carry out its activities are the primary source of a business profit [47]. Talent, and the attendant organisational capabilities are considered a source of competitive advantage and are therefore central to the execution of the organization’s strategy and achievement of strategic goals.

- Workplace safety. Safety science has evolved significantly through recent theories such as “Safety 2” [22] and resilience engineering [26]; both of which have contributed to the reconceptualization of organisational safety management. These approaches support a more adaptive and responsive process recognizing employees as being a crucial “solution” in maintaining the balance between organisational performance and safety which is a far more positive approach to the traditional risk mitigation focus. From a strategic perspective, Carden et al., [12] (p.143) outline a model drawing on enterprise-wide risk management principles suggesting that it is ‘imperative for companies to manage unforeseen events and safety risks’. The model is based on the input (safety risks) – process (corporate governance) – output (fewer incidents) quality management approach. Significantly, the approach was consistent with the framework applied to wellbeing by Danna and Griffin [48].

- Workplace health and wellbeing. Despite limited evidence, one strategic approach that focuses on the macro level of the enterprise is the Healthy Workplace Framework [50]. This framework establishes four avenues to address and promote holistic worker health, safety, and wellbeing: (i) the psychosocial work environment (ii) the physical work environment (iii) personal health resources, and (iv) linkages between the enterprise and its wider community” (p.83). More recently, Cooklin et al., [51] applied this framework in several Australian workplaces and found that there were positive associations with such interventions. Similar frameworks to follow this methodology include the UK Work Well Model (2017) and US NIOSH Total Worker Health Model (2011). It is also evident that the design of work and promotion of recovery is often an overlooked element of wellbeing. One organization centric theory that supports this is the job-demand resources (JDR) model [39] which seeks to optimize a balance between personal “inputs and outputs”. JDR considers that the individual’s resources such as job autonomy, supervisor support, and goal clarity create motivation, but once the demands of the role exceed the individual’s ability to cope, performance is reduced due to physical and psychological health impairment.

- Organisational Context. The set of organisational circumstances under which the strategy process and content is determined to set the direction and scope of an organization over the long term. It is informed by how employees perceive the enactment of organisational policies and procedures relating to HSW in their organization at a given point in time and the organizations obligations beyond legal compliance [52].

- HSW Strategy. A strategic direction and allocation of resources dedicated to matching internal capabilities with opportunities and threats in achieving a future state of HSW, as embedded in, and acknowledged as a priority of the organisational strategy while being underpinned by the organisational mission, values, and priorities [52].

- HSW Employee engagement. A workplace approach designed to ensure that employees are committed to their organisation’s goals and values, motivated to contribute to organisational success, and are able at the same time to enhance their own sense of well-being through a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption [52].

- Leadership. Strategic leadership is the ability to anticipate, envision, maintain flexibility, think strategically, and work with others to initiate changes that will create a viable future for the organization [53].

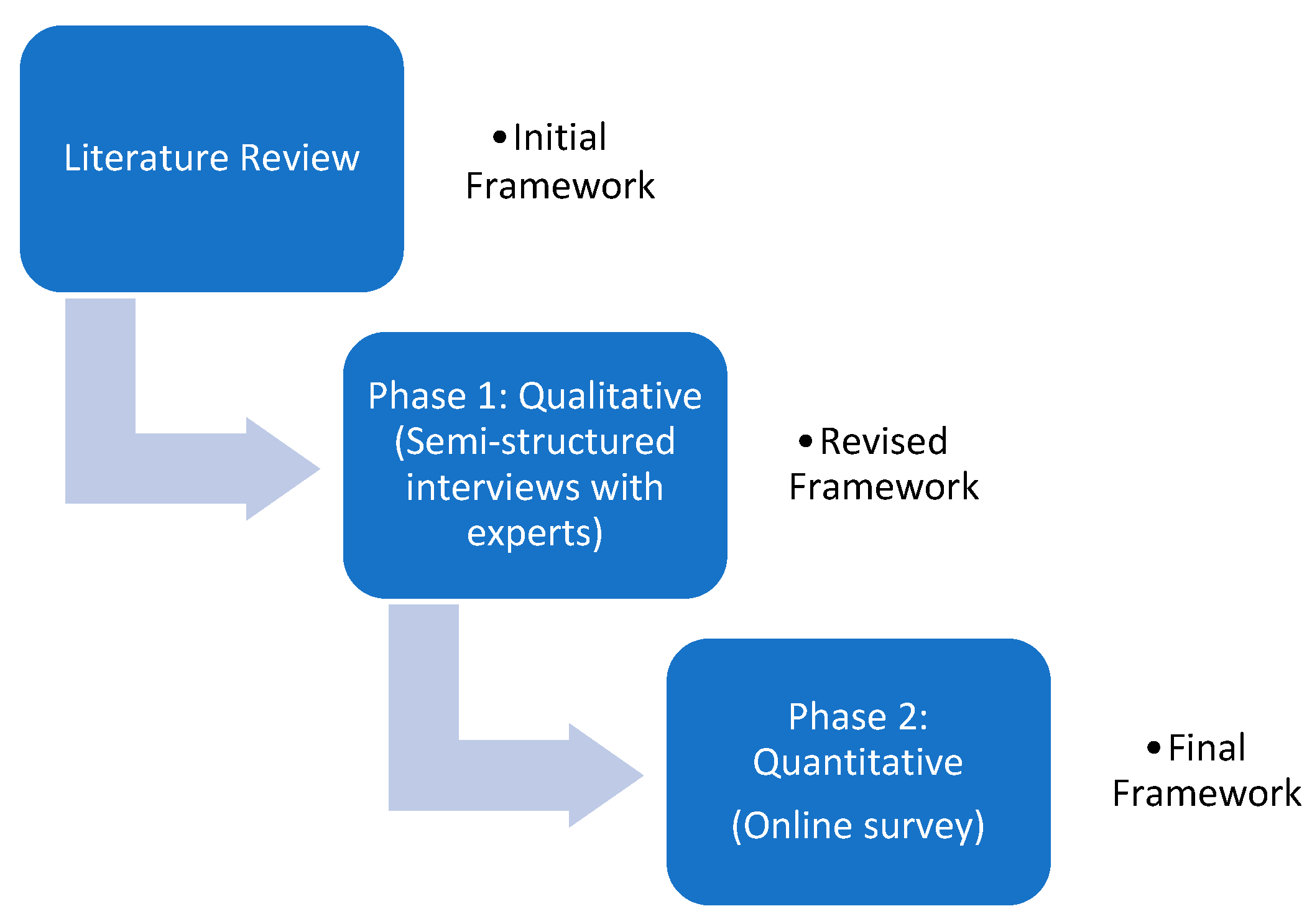

3. Materials and Methods

Summary of Semi-structured Interviews [Phase one – qualitative enquiry]

Triangulation and validation of Phase One results [Phase Two – quantitative enquiry]

Participant selection

- experience at a management level (middle or executive) responsible for the WHS or wellbeing strategy; or

- experience at a management level (middle or executive) responsible for employee engagement or human capital management; and,

- currently working in either public or private sector organizations.

Survey development and administration

Pilot Survey

Main Survey

Data analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sample Demographics

4.2. HSW Strategy Scale

- Factor one was explained by two variables with loadings of 0.41 and 0.80. This represented the physical safety and personal growth elements of HSW. This was labelled Worker Wellbeing.

- Factor two was explained by one variable with a loading of -0.97 and represented the UWES (vigor, dedication, and absorption), risk recognition, proactive action, and individual capability. This was labelled Individual Capacity.

- Factor three was explained by three variables with loadings of 0.54, 0.70 and 0.74, This factor represented relationships between engagement, efficacy, and strategy feedback loops in the conceptual framework. This was labelled Engagement and Efficacy.

- Factor four was explained by six variables with loadings ranging between 0.41 to 0.70 representing the organisational context in which the HSW strategy emerges, and content dimensions for safety, wellness, and wellbeing from the conceptual framework. This was labelled Strategy Context and Content.

- Factor five was explained by three variables with loadings ranging between 0.44 to 0.68. This represented attributes such as leader-member coaching, mentoring, strength of interpersonal relationships, and the individual’s ability to influence and act on HSW. This was labelled Connection and Ownership.

- Factor six was explained by two variables with loadings of -0.64 and -0.60. This factor represented relationships between engagement and efficacy and organisational processes. This was labelled Engagement and Processes.

- Factor seven was explained by two variables with loadings of 0.54 and 0.53. This factor represented processes inclusive of governance, resourcing requirements, and involvement of employees at various levels in the organization in strategy to determine the content. This was labelled Strategy Process Content.

5. Discussion

- Organisational context. The online survey was able to confirm that immediate and long term HSW strategy content is determined by internal organisational aspects and external obligations. An organizations’ HSW strategy content and priorities are informed by the strategy process embedded within organisational context. This context relates to legal obligations and corporate governance requirements and its effect on organisational culture. In addition, the consideration of organisational strategy requires feedback loops within the strategy cycles informed by employees’ perception of HSW priorities based on normal work and risk. This was confirmed by both phases of the study. As such, our study was able to make original contribution and define organisational context as:

- HSW strategy. The study proposed that the HSW strategy process and content are interrelated and need to match internal capabilities with the risk and opportunity management efforts of the organization to achieve a future state of HSW, acknowledged as an organisational strategic priority. In our study the HSW strategy dimensions included within the conceptual framework were informed by, and was able to extend, the frameworks outlined by Zou and Sunindijo [49], Yorio, Willmer, and Moore [37], World Health Organisation and Burton [50] and O’Neill and Wolfe [6]. It was also evident that prominent contributions from Hollnagel [22], and Provan et al., [26] informed current thinking on strategy which has attributes that are analogous with the resource-based view. In particular, guided adaptability dimensions of Anticipation, Readiness to respond, Synchronization and Proactive learning [26] were incorporated in the framework to support the creation, revision, and refinement of risk models in strategy development that meet operational demands. As such, the dynamic iterative cycle adopted for this study related to organisational context, corresponds with strategy development as outlined by Zou and Sunindijo [49], and with the Anticipation and the Plan and Revise phase of resilience engineering. In this study, Readiness and respond phase were aligned with the matching of resources and capabilities, Synchronization and Proactive learning phases were related to the feedback loops as iterative cycles and strategy efficacy indicators were included in the conceptual framework developed for this study. This research, therefore, made original contribution to the research in HSW through the operationalization and validation of HSW strategy in phase one and two, and was able to re-define HSW strategy as:

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zwetsloot, G. I. J. M.; van Scheppingen, A. R.; Dijkman, A. J.; Heinrich, J.; den Besten, H. The organizational benefits of investing in workplace health. International Journal of Workplace Health Management 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S. L.; Green, C. R.; Marty, A. Meaningful Work, Job Resources, and Employee Engagement. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; LoBuglio, N.; Dutton, J. E.; Berg, J. M. Job crafting and cultivating positive meaning and identity in work. In Advances in positive organizational psychology; Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2013.

- Xiang, J.; Mittinty, M.; Tong, M. X.; Pisaniello, D.; Bi, P. Characterising the burden of work-related injuries in South Australia: a 15-year data analysis. International journal of environmental research and public health 2020, 17, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S.; Martinov-Bennie, N.; Cheung, A.; Wolfe, K. Issues in the Measurement and Reporting of Work Health and Safety Performance: A Review; Canberra., Available Online:. Available online: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au (accessed on 01 December 2016).

- O’Neill, S.; Wolfe, K. Measuring and Reporting on Work Health and Safety; Safe Work Australia. Canberra. Avaliable online: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au (acessed on 06 June 2018).

- Bar-Haim, A.; Karassin, O. A Multilevel Model of Responsibility Towards Employees as a Dimension of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Mgmt. & Sustainability 2018, 8, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kercher, K. Corporate Social Responsibility: Impact of globalisation and international business. Corporate Governance eJournal 2007, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbey, J. Work wellbeing : A new perspective. Governance Directions 2015, 67, 334–339. [Google Scholar]

- Zwetsloot, G.; Starren, A.; Schenk, C.; Heuverswyn, K.; Kauppinnen, K.; Lindstrom, K.; et al. Corporate Social Responsibility and Safety and Health at Work; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work: Luxembourg, 2004; Available online: https://www.lu.lv (accessed on 06 June 2019).

- Hopkins, A, Toohey, J, Stacy, R & Else, D. Orgnisations. In in HaSPA (Health and Safety Professionals Alliance), The core body of knowledge for generalist OHS professional; Safety Institute of Australia: Tullamarine, VIC, 2012; Available online: https://www.ohsbok.org.au (accessed on 19 19 August 2016).

- Carden, L. L.; Boyd, R. O.; Valenti, A. Risk management and corporate governance: Safety and health work model. Southern Journal of Business and Ethics 2015, 7, 137. [Google Scholar]

- Harter, J. K.; Schmidt, F. L.; Agrawal, S.; Plowman, S. K.; Blue, A. The Relationship between Engagement at Work and Organizational Outcomes Q12 Meta-Analysis; Gallup Organisation. 2013. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/reports. (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- McCarthy, G.; Almeida, S.; Ahrens, J. Understanding employee well-being practices in Australian organizations. 2011.

- Gahan, P.; Sievewright, B.; Evans, P. Workplace Health and Safety, Business Productivity and Sustainability:A Report Prepared for Safe Work Australia. Centre for Workplace Leadership; Canberra. Australia, 2014. avaliable online: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au. (accessed on 27 August 2016).

- Zwetsloot, G.; Van Scheppingen, A. Towards a Strategic Business Case for Health Management; Work Healt.; Johansson, U., Ahonen, G., Roslander, R., Eds.; Taylor & Francis, 2007.

- Bevan, S. The Business Case for Employees’ Health and Wellbeing; The Work Foundation. London, 2010. Available online: http://investorsinpeople.ph/wp-content/uploads (accessed on 24 May 2016).

- Hafner, M.; van Stolk, C.; Saunders, C.; Krapels, J.; Baruch, B. Health, Wellbeing and Productivity in the Workplace; Europe. 2015. available online https://www.rand.org/pubs. (accessed on 06 June 2019).

- Braithwaite, J.; Hibbert, P.; Blakely, B.; Plumb, J.; Hannaford, N.; Long, J. C.; et al. Health system frameworks and performance indicators in eight countries: a comparative international analysis. SAGE open medicine 2017, 5, 2050312116686516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borys, D.; Else, D.; Leggett, S. The fifth age of safety: the adaptive age. Journal of health and safety research and practice 2009, 1, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman, J.; Lyon, A. Defining Best Practice in Corporate Occupational Health and Safety Governance; London. 2006. Available online: https://www.hse.gov.uk (accessed on 20 September 2017).

- Hollnagel, E. A tale of two safeties. Nuclear Safety and Simulation 2013, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K. E.; Sutcliffe, K. M. Managing the Unexpected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty; John Wiley & Sons, 2011; Vol. 8.

- Hollnagel, E.; Woods, D. D.; Leveson, N. Resilience Engineering: Concepts and Precepts; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2006.

- Hollnagel, E. Safety-I and Safety-II: The Past and Future of Safety Management; CRC press, 2018.

- Provan, D. J.; Woods, D. D.; Dekker, S. W. A.; Rae, A. J. Safety II professionals: How resilience engineering can transform safety practice. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2020, 195, 106740. [Google Scholar]

- Litchfield, P.; Cooper, C.; Hancock, C.; Watt, P. Work and wellbeing in the 21st century. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2016, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Zhu, C. J.; Timming, A. R.; Su, Y.; Huang, X.; Lu, Y. Using the past to map out the future of occupational health and safety research: where do we go from here? The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2020, 31, 90–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanko, M.; Dawson, P. Occupational Health and Safety Management in Organizations: A Review. International Journal of Management Reviews 2012, 14, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Begum, M.; Van Eerd, D.; Smith, P. M.; Gignac, M. A. M. Organizational perspectives on how to successfully integrate health promotion activities into occupational health and safety. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2021, 63, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryson, A.; Forth, J.; Stokes, L. Does Worker Wellbeing Affect Workplace Performance; London. 2014, available online:. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications (accessed on 18 June 2017).

- Lee, C.; Esen, E.; DiNicola, S. Employee Job Satisfaction and Engagement: The Doors of Opportunity Are Open; 2017.

- Swamy, D. R.; Nanjundeswaraswamy, T. S.; Rashmi, S. Quality of work life: scale development and validation. International Journal of Caring Sciences 2015, 8, 281. [Google Scholar]

- Warr, P.; Nielsen, K. Wellbeing and work performance. Handbook of well-being. Salt Lake City, UT: DEF Publishers, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Melander, A.; Löfving, M.; Andersson, D.; Elgh, F.; Thulin, M. Introducing the Hoshin Kanri strategic management system in manufacturing SMEs. Management Decision 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Laan, L.; Yap, J. Foresight & Strategy in the Asia Pacific Region. Management for Professionals 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yorio, P. L.; Willmer, D. R.; Moore, S. M. Health and safety management systems through a multilevel and strategic management perspective: Theoretical and empirical considerations. Safety science 2015, 72, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, W. R.; Bingham, J. B.; Colvin, A. J. S. Aligning employees through “line of sight. ” Business horizons 2006, 49, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of managerial psychology 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J. R.; Oldham, G. R. Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational behavior and human performance 1976, 16, 250–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truss, C.; Alfes, K.; Delbridge, R.; Shantz, A.; Soane, E. Employee Engagement in Theory and Practice; Routledge, 2013.

- Van De Voorde, K.; Paauwe, J.; Van Veldhoven, M. Employee well-being and the HRM–organizational performance relationship: a review of quantitative studies. International Journal of Management Reviews 2012, 14, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, Å. Strategic management thinking and practice in the public sector: A strategic planning for all seasons? Financial Accountability & Management 2015, 31, 243–268. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of management 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad CK, H. G. The Core Competence of the corporation Harvard Business Review, Vol. 68. 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D. The resource-based view of the firm. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Business and Management; 2019.

- Henry, A. Understanding Strategic Management; Oxford University Press, USA, 2008.

- Danna, K.; Griffin, R. W. Health and well-being in the workplace: A review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of management 1999, 25, 357–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, P. X. W.; Sunindijo, R. Y. Strategic Safety Management in Construction and Engineering; John Wiley & Sons, 2015.

- World Health Organisation; J.Burton. WHO Healthy Workplace Framework and Model Synthesis Report; 2010; pp 1–13.

- Cooklin, A.; Husser, M. E.; Joss, M. N.; Oldenburg, B. Integrated Approaches to Worker Health, Safety and Well-Being: Research Report 1213-088-R1C; Melbourne, Australia. 2013, available online:. Available online: https://research.iscrr.com.au (accessed on 18 August 2016).

- Halliday, B. Work health, safety, and wellbeing strategy and employee engagement: a mixed-methods study, University of Southern Queensland, 2020.

- Ireland, R. D.; Hitt, M. A. Achieving and maintaining strategic competitiveness in the 21st century: The role of strategic leadership. Academy of Management Perspectives 1999, 13, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, L. Designing and Doing Survey Research; Sage, 2012.

- Williams, B.; Onsman, A.; Brown, T. Exploratory factor analysis: A five-step guide for novices. Australasian journal of paramedicine 2010, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, A. B.; Osborne, J. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical assessment, research, and evaluation 2005, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog, M. A. Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Research in nursing & health 2008, 31, 180–191. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, G. L.; Turgeon, A. F.; Choi, P. T. The science of opinion: survey methods in research. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie 2012, 59, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taheri, B.; Porter, C.; Valantasis-Kanellos, N.; König, C. Quantitative data gathering techniques. Research methods for business and management: A guide to writing your dissertation. 2015, 155–174.

- Saunders, M. N. K.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students 5th ed.; Pearson Education Limited, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England., 2007.

- Fabrigar, L. R.; Wegener, D. T.; MacCallum, R. C.; Strahan, E. J. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological methods 1999, 4, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis; 7th Editio.; Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009.

- Osborne, J. W. What is rotating in exploratory factor analysis? Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation 2015, 20. [Google Scholar]

- O’Dwyer, L. M.; Bernauer, J. A. Quantitative Research for the Qualitative Researcher; SAGE publications, 2013.

| Position | Frequency | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| Senior Manager | 46 | 48.5 |

| Practitioner | 30 | 31.5 |

| Manager | 19 | 20.0 |

| Discipline | Frequency | % of total |

| Workplace Health and Safety | 44 | 46.4 |

| Other | 31 | 31.6 |

| Human Resources | 18 | 18.9 |

| Wellbeing or Health | 2 | 2.1 |

| Gender | Frequency | % of total |

| Male | 66 | 69.5 |

| Female | 29 | 30.5 |

| Location | Frequency | % of total |

| Queensland | 41 | 43.2 |

| Victoria | 18 | 18.9 |

| New South Wales | 17 | 17.9 |

| South Australia | 6 | 6.3 |

| Western Australia | 4 | 4.2 |

| Tasmania | 4 | 4.2 |

| Northern Territory | 3 | 3.2 |

| Australian Capital Territory | 2 | 2.1 |

| Industry Type | Frequency | % of total |

| Other | 47 | 49.5 |

| Public | 23 | 24.2 |

| Manufacturing | 7 | 7.4 |

| Resources | 7 | 7.4 |

| Construction | 6 | 6.3 |

| Transport | 5 | 5.3 |

| Experience | Frequency | % of total |

| 10 or more | 78 | 82.1 |

| 5-9 | 10 | 10.5 |

| 0-4 | 7 | 7.4 |

| Education level | Frequency | % of total |

| Postgraduate | 75 | 79.0 |

| Undergraduate | 13 | 13.6 |

| Vocational | 7 | 7.4 |

| Question | Mean(M) | Standard Deviation (SD) |

Factor | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |||

| Individual risk awareness and proactive action are central to personal growth in HSW Capability | 4.28 | .76 | 0.98 | ||||||

| Prevention of harm, including physical safety is an inherent core of Worker Wellbeing | 4.57 | .66 | 0.62 | - | |||||

| Individual Enablers influences Work Health, Safety and Wellbeing Employee Engagement | 4.17 | .74 | -0.97 | ||||||

| Individual Enablers influence Work Health, Safety and Wellbeing Strategy | 3.73 | .92 | 0.79 | ||||||

| Work Health, Safety and Wellbeing Strategy Efficacy influences Work Health, Safety and Wellbeing Strategy | 3.80 | .77 | 0.70 | ||||||

| Work Health, Safety and Wellbeing Employee Engagement influences Individual Enablers | 3.79 | .80 | 0.54 | -0.51 | |||||

| Leadership influences Organisational Context, Work Health, Safety and Well-being Strategy and Employee Engagement | 4.59 | .78 | -0.80 | ||||||

| Work Health, Safety and Wellbeing Strategy influences Work Health, Safety and Wellbeing Employee Engagement | 4.27 | .73 | -0.70 | ||||||

| Organisational Culture influences HSW strategy development over the short and long-term | 4.43 | .68 | -0.62 | ||||||

| Individual leadership capability affects wellbeing and the level of engagement in strategy | 4.54 | .70 | -0.58 | ||||||

| Organisational processes influence Work Health, Safety and Wellbeing Employee Engagement | 4.22 | .80. | 0.50 | -0.55 | |||||

| To be in an optimal state of wellbeing employees need to be connected at the individual, team and organisational levels and have purpose in their work | 4.48 | .68 | -0.54 | ||||||

| Organizational Context influences Work Health, Safety and Wellbeing Strategy | 4.38 | .59 | -0.42 | ||||||

| Worker Wellbeing includes employees managing lifestyle health and psychological health risks as an organisational priority. Which positively affects employee commitment | 4.46 | .73 | -0.41 | ||||||

| Meaningful consultation for understanding the HSW Strategy implementation impacts on the level of employee engagement in the short and long term | 4.30 | .63 | 0.68 | ||||||

| HSW Strategy measurement must focus on broader outcomes related to individual wellbeing, work completed, worker perceptions on safety systems, risk management effectiveness and safety | 4.18 | .73 | 0.67 | ||||||

| Organisational and leader trust is dependent on values-based feedback which affects employee motivation and individual wellbeing. | 4.29 | .68 | 0.53 | ||||||

| Ownership enhances personal growth and the capability to engage in HSW Strategy | 4.35 | .61 | 0.44 | ||||||

| Personal risk awareness and control needs to be facilitated by the organisation as part of strategy implementation to engage employees in HSW | 4.26 | .62 | 0.42 | ||||||

| Work Health, Safety and Wellbeing Employee Engagement influences Organisational Processes | 3.87 | .85 | -0.64 | ||||||

| Work Health, Safety and Wellbeing Employee Engagement influences Work Health, Safety and Wellbeing strategy efficacy |

4.36 |

.76 | -0.60 | ||||||

| HSW strategy and resource allocation must be integrated and address immediate risks prior to longer term strategic risks. | 4.00 | .88 | 0.54 | ||||||

| Employees need to be involved in HSW strategy development at an early stage and be clear on their personal contribution as it relates to vision, mission and goals | 4.15 | .87 | 0.53 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).