Submitted:

15 October 2023

Posted:

17 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

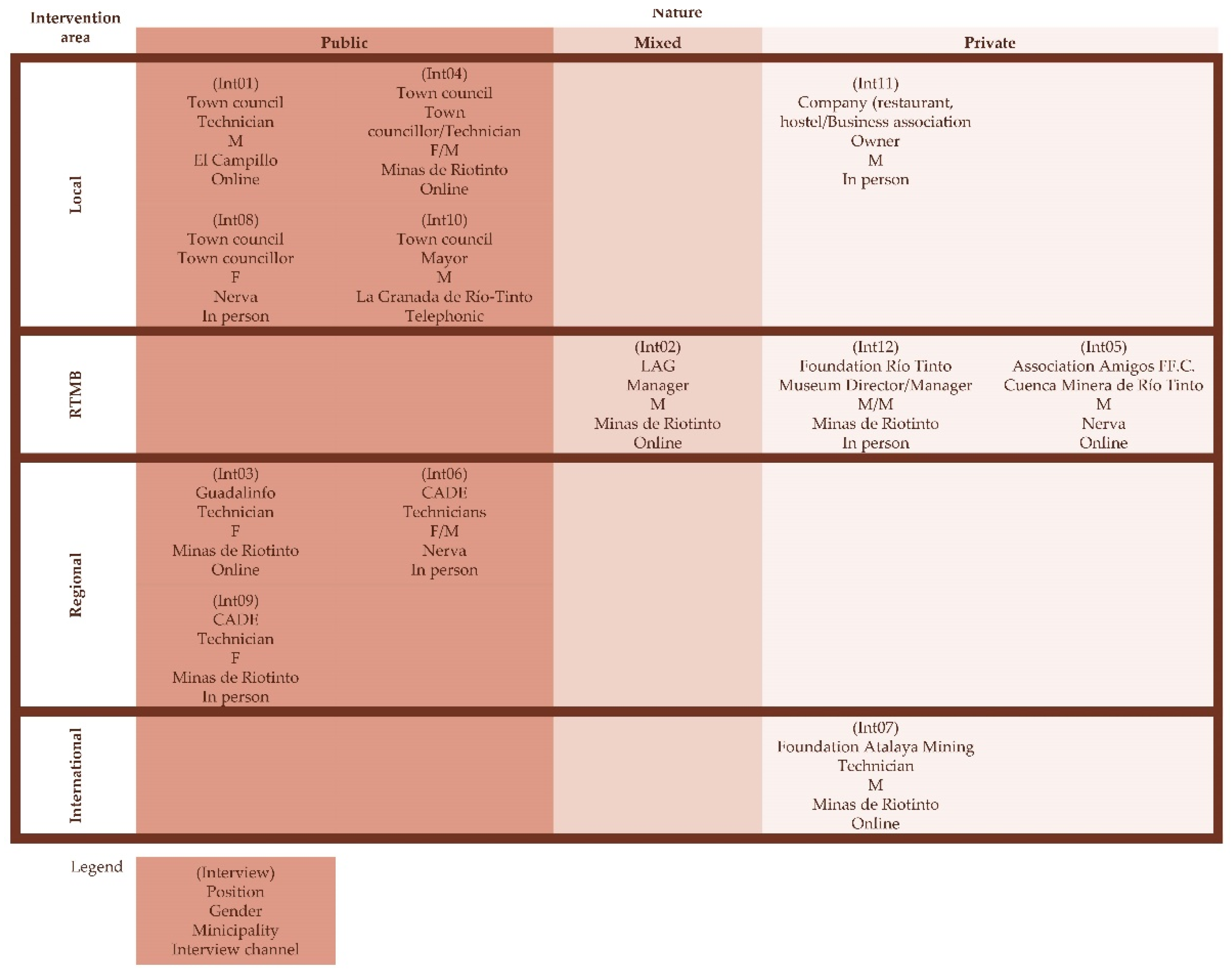

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

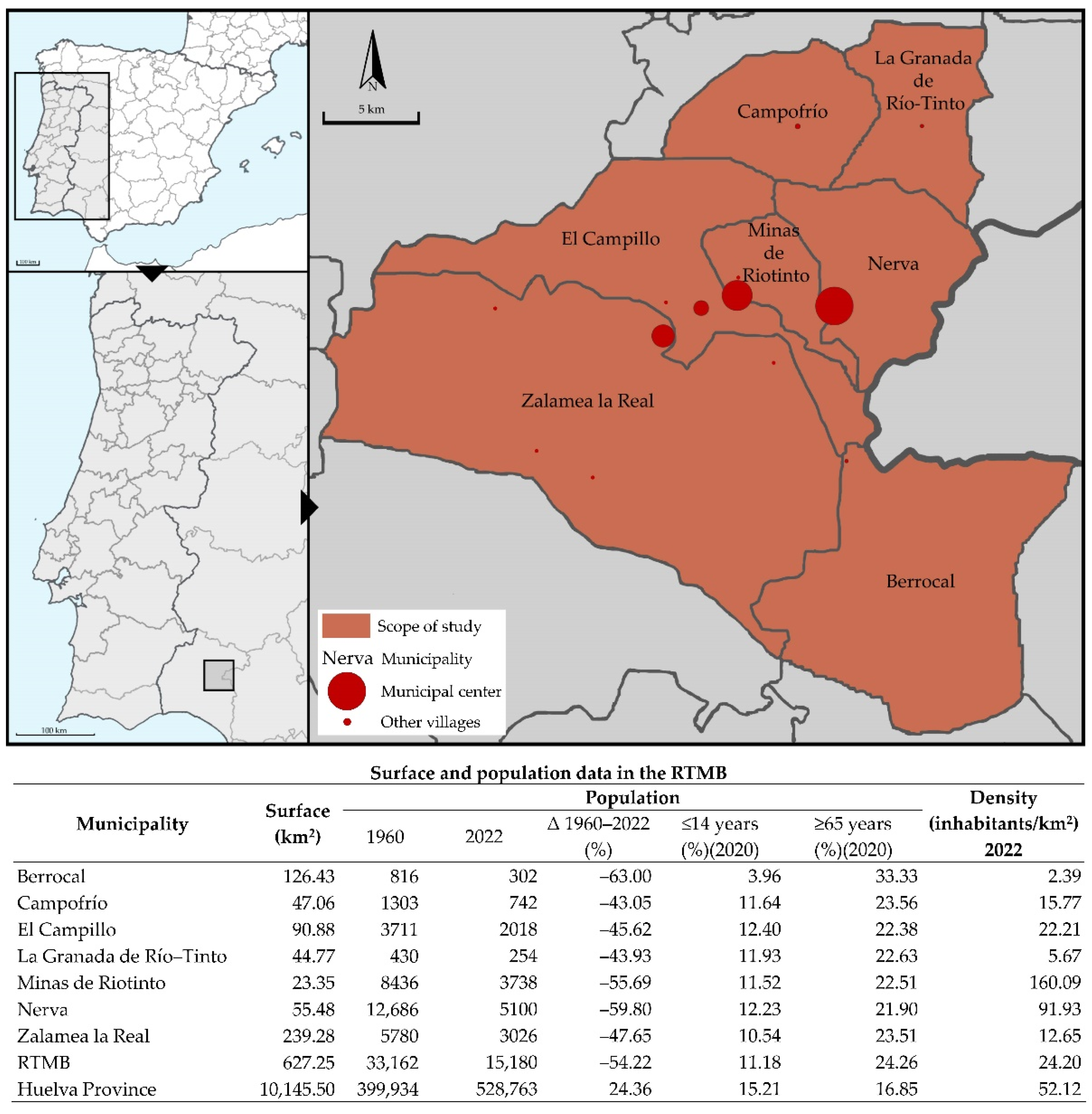

2.2. Scope of study

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Responses to the mining crisis

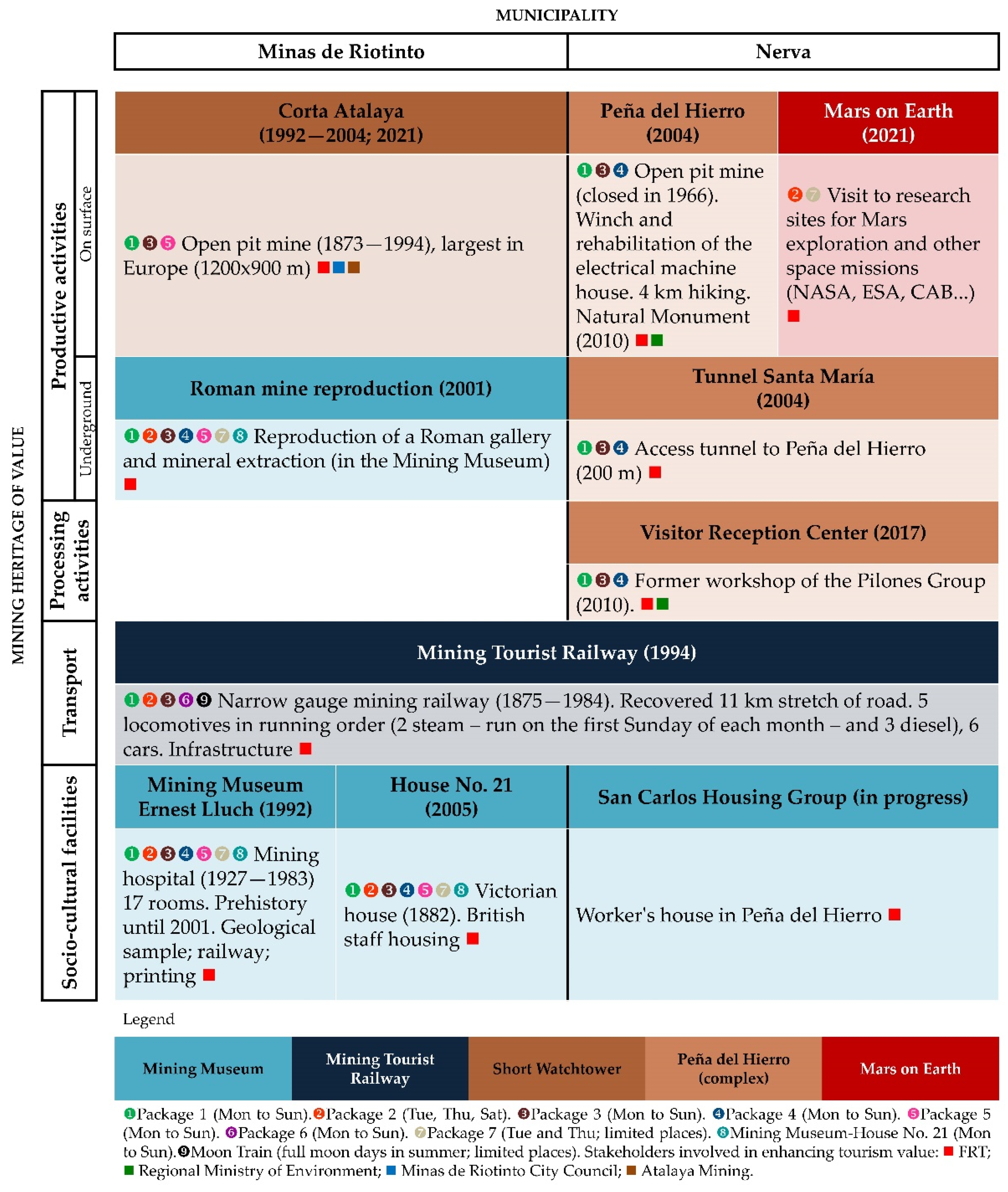

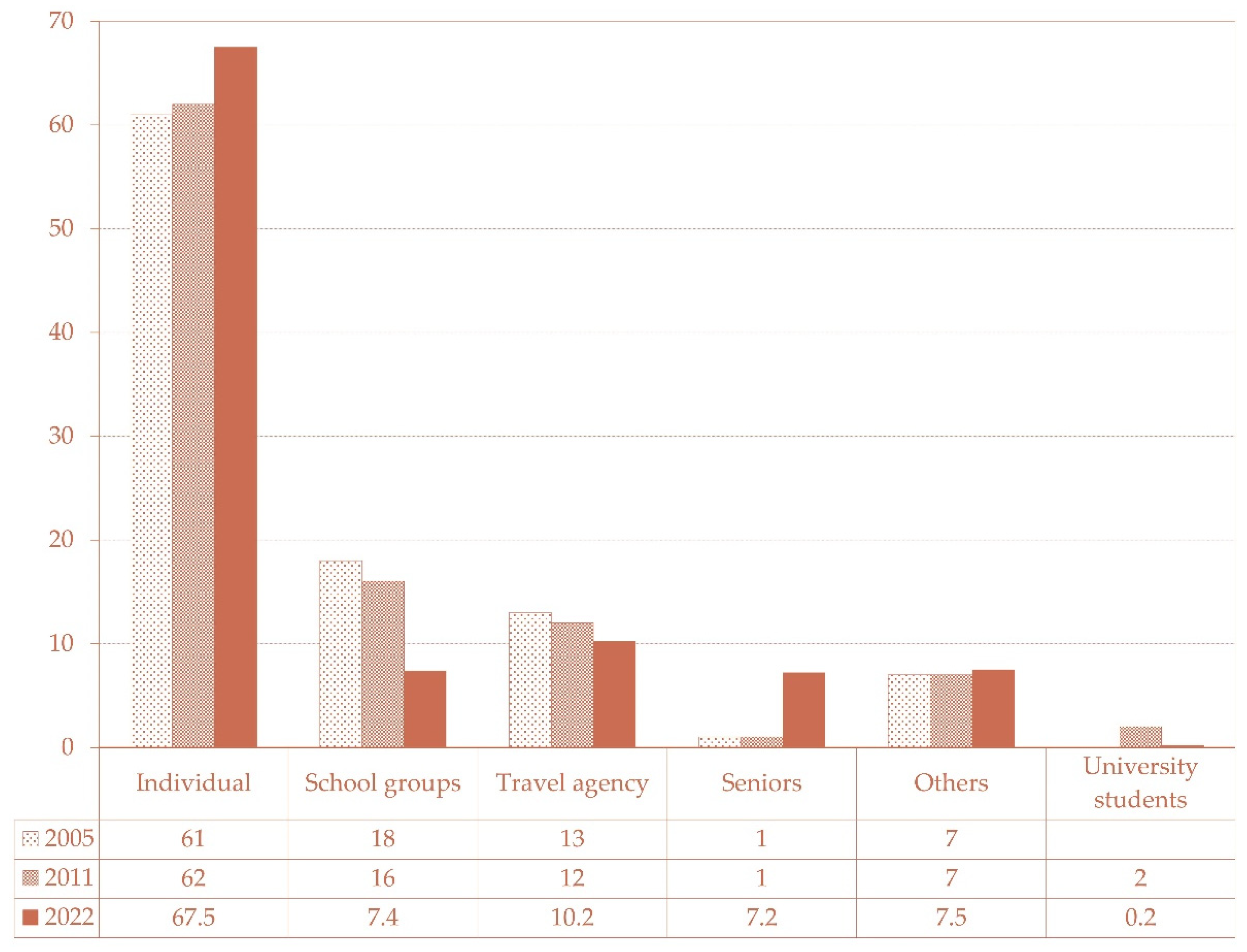

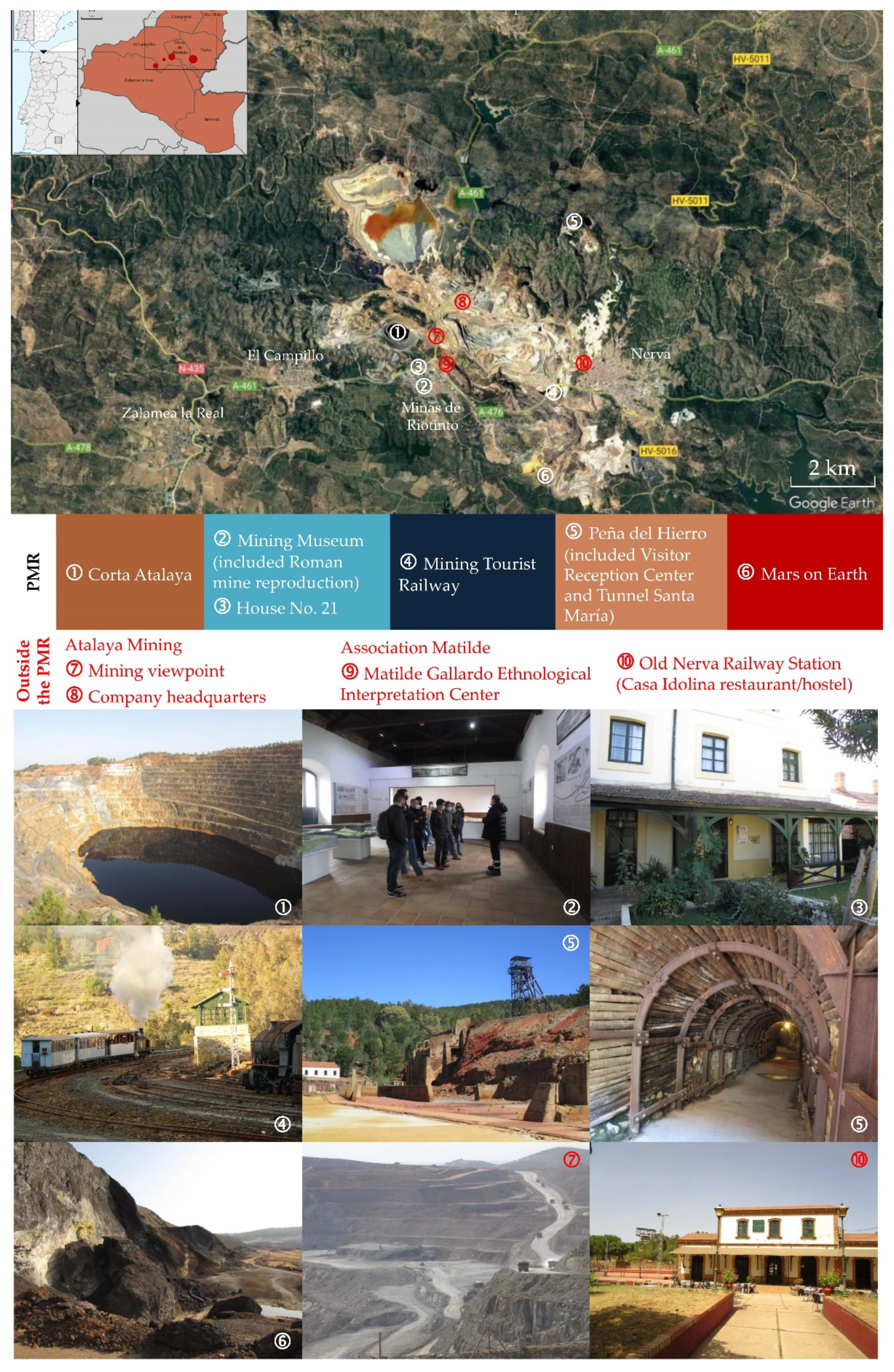

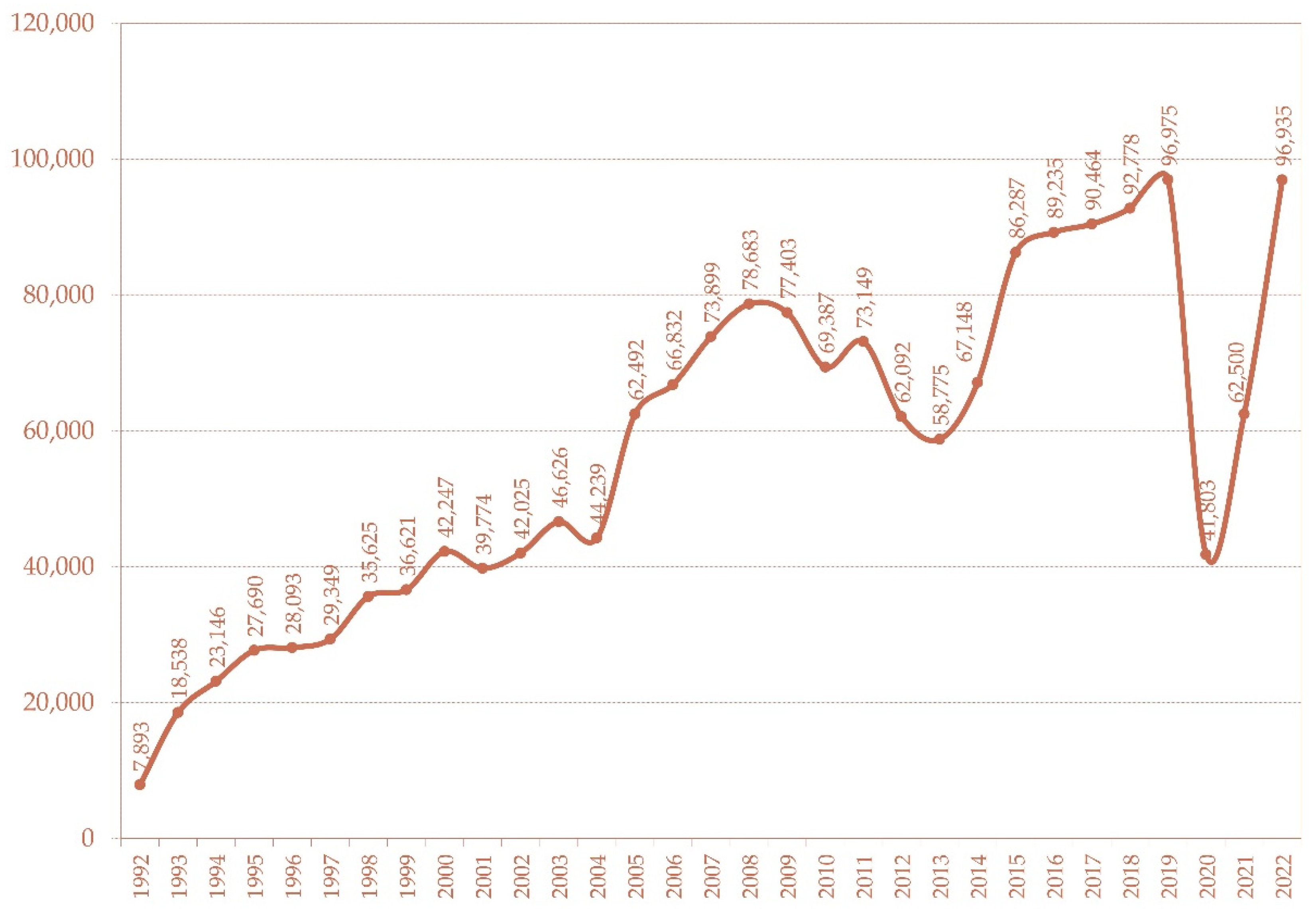

3.2. The tourist value of mining heritage

3.3. Change of scenery

3.4. Tourism and sustainable rural development processes

3.4.1. Socio-cultural dimension

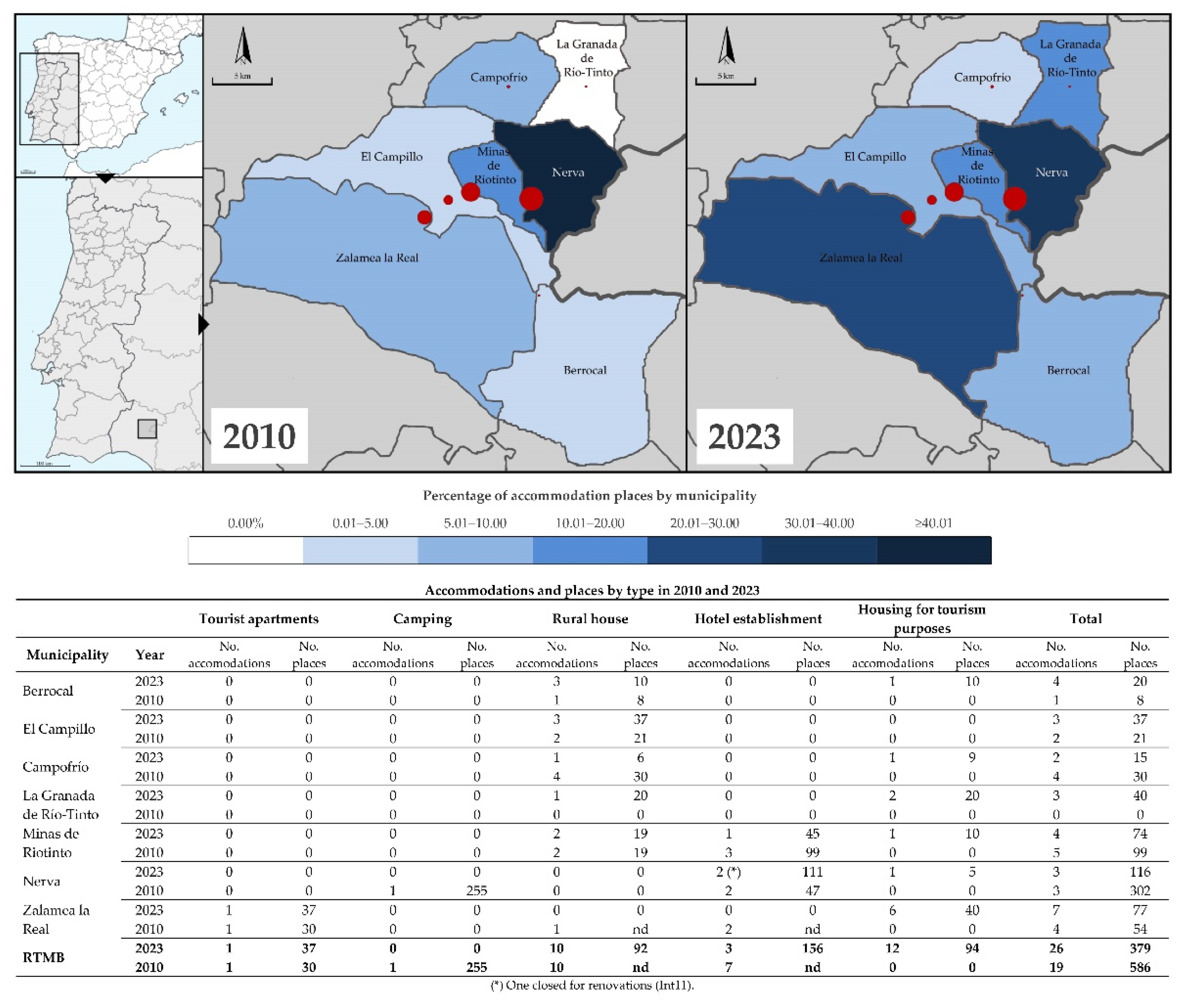

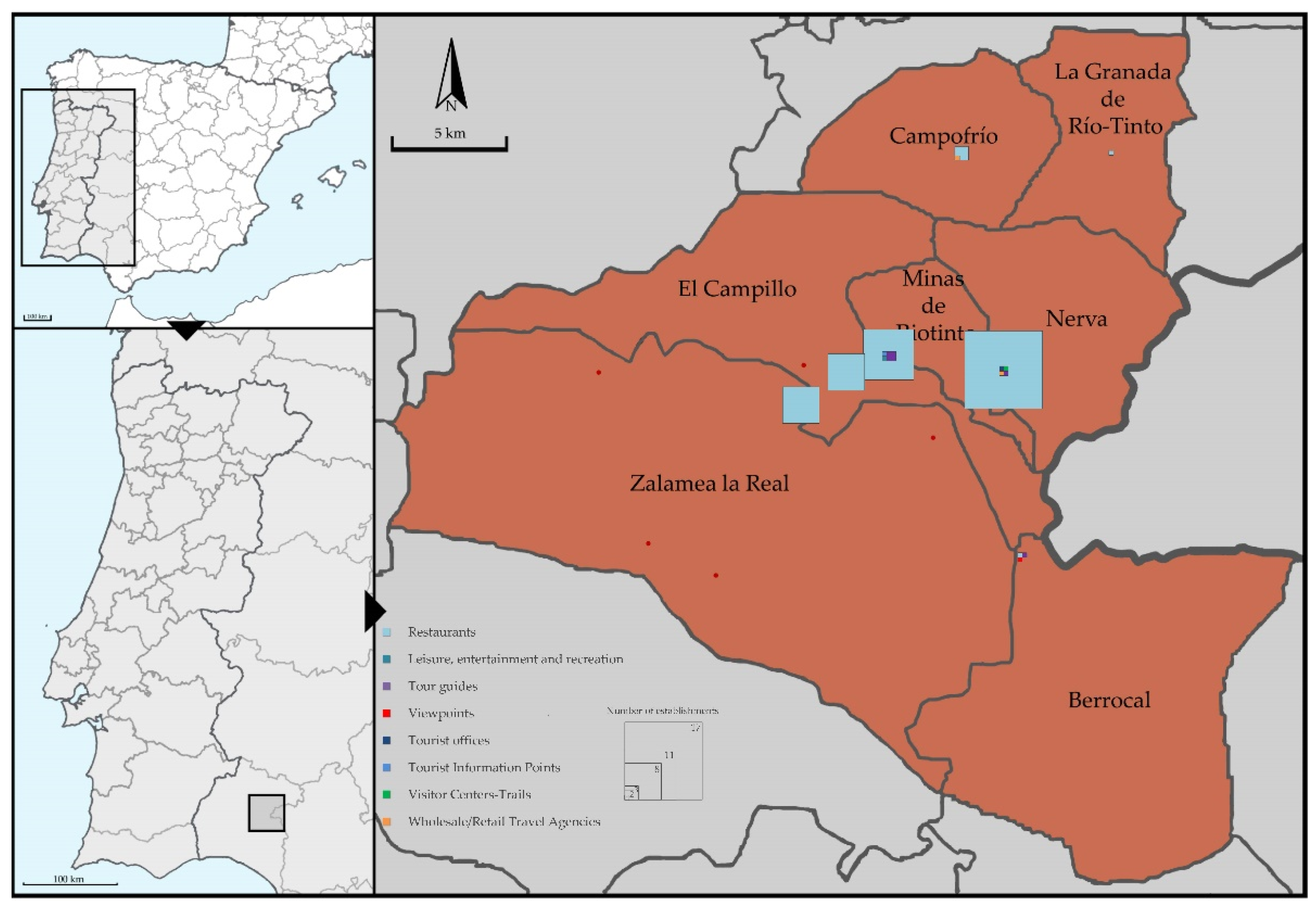

3.4.2. Economic dimension

3.4.3. Environmental dimension

3.4.4. Political-institutional dimension

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tentative Lists. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/ (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Avango, D.; Rosqvist, G. When mines go silent: Exploring the afterlives of extraction sites. In Nordic Perspectives on the Responsible Development of the Arctic: Pathways to Action; Nord, D.C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Swizerland, 2021; pp. 349–367.

- Somoza-Medina, X.; Monteserín-Abella, O. The sustainability of industrial heritage tourism far from the axes of economic development in Europe: Two case studies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1077. [CrossRef]

- Heldt-Cassel, S.; Pashkevich, A. Heritage tourism and inherited institutional structures: The case of Falun Great Copper Mountain. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2011, 11, 54–75. [CrossRef]

- Lintz, G.; Wirth, P.; Harfst, J. Regional Structural Change and Resilience. Raumforschung und Raumordnung 2012, 70, 373–365. [CrossRef]

- Benito-del-Pozo, P. Patrimonio industrial y Cultura del Territorio. Bol. Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2002, 1, 213–227.

- Edwards, J.A.; Llurdés-i-Coit, J.C. Mines and quarries: Industrial heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 341–363. [CrossRef]

- Cañizares-Ruiz, M.C. El atractivo turístico de una de las minas de mercurio más importantes del mundo: El parque minero de Almadén (Ciudad Real). Cuad. Tur. 2008, 21, 9–31.

- Valenzuela-Rubio, M.; Palacios-García, A.J.; Hidalgo-Giralt, C. La valorización turística del patrimonio minero en entornos rurales desfavorecidos: Actores y experiencias. Cuad. Tur. 2008, 22, 231–260.

- Llurdés-i-Coit, J.C. Patrimonio industrial y Patrimonio de la Humanidad. El ejemplo de las Colonias Textiles Catalanas. Potencialidades turísticas y algunas reflexiones. Bol. Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 1999, 28, 147–160.

- Hospers, G.J. Restructuring Europe’s rustbelt: The case of the German Ruhrgebiet. Intereconomics 2004, 39, 147–156.

- Avango, D.; Lépy, É.; Brännström, M.; Heikkinen, H.; Komu, T.; Pashkevich, A.; Österlin, C. Heritage for the future: Narrating abandoned mining sites. In Resource extraction and arctic communities: The new extractivist paradigm, Sörlin, S., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 206–228.

- Price, W.R.; Rhodes, M.A. Coal dust in the wind: Interpreting the industrial past of South Wales. Tourism Geogr. 2022, 24, 837–858. [CrossRef]

- Lusso, B. Patrimonialisation et greffes culturelles sur des friches issues de l’industrie minière. Regards croisés sur l’ancien bassin minier du Nord-Pas de Calais (France) et la vallée de l’Emscher (Allemagne). EchoGéo 2013, 26. [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Giralt, C. El proceso de valorización turística del patrimonio minero. Un análisis de los agentes involucrados y de las políticas implementadas. Doctoral Dissertation-University Carlos III de Madrid, Birmingham, Madrid, Spain, 2010.

- Cañizares-Ruiz, M.C. Patrimonio, Minería y Rutas en el Valle de Alcudia y Sierra Madrona (Ciudad Real). Estudios geográficos 2013, 74(275), 409–437.

- Jansen-Verbeke, M. Industrial heritage: A nexus for sustainable tourism development. Tourism Geogr. 1999, 1, 70–84. [CrossRef]

- Llurdés-i-Coit, J.C.; Saurí-Pujol, D.; Cerdán-Heredia, R. Conflictos locacionales en territorios en crisis. Turismo y residuos en Cardona (Barcelona). An. Geogr. Univ. Complut. 1999, 19, 119–140.

- Harfst, J.; Sandriester, J.; Fischer, W. Industrial heritage tourism as a driver of sustainable development? A case study of Steirische Eisenstrasse (Austria). Sustainability 2021, 13(7), 3857. [CrossRef]

- Capel-Sáez, H. La rehabilitación y el uso del patrimonio histórico industrial”, en Doc. d’Análisis Geogràfica 1996, 29, 19–50.

- Cueto-Alonso, G.J. Nuevos usos turísticos para el patrimonio minero en España. PASOS 2016, 14, 1013–1026.

- Conesa, H.M. The difficulties in the development of mining tourism projects: The case of La Unión Mining District. PASOS 2010, 8, 653–660. [CrossRef]

- Szromek, A.R.; Herman, K. A Business Creation in Post-Industrial Tourism Objects: Case of the Industrial Monuments Route. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1451. [CrossRef]

- Llurdés-i-Coit, J.C.; Díaz-Soria, I.; Romagosa, F. Patrimonio minero y turismo de Proximidad: Explorando sinergias. El caso de Cardona. Doc. d’Análisis Geogràfica 2016, 62, 55–77. [CrossRef]

- Caamaño-Franco, I.; Andrade-Suárez, M. The value assessment and planning of industrial mining heritage as a tourism attraction: The case of Las Médulas cultural space. Land 2020, 9, 404.

- Cooper, I. Post-occupancy evaluation-where are you? Build. Res. Inf. 2001, 29, 158–163. [CrossRef]

- De-La-Broise, P. La muséologie au défi d’une patrimonialisation post-industrielle: Le cas du bassin minier Nord–Pas-de-Calais. Hermès 2011, 3, 125–130.

- Martínez-Puche, A.; Pérez-Pérez, D. El Patrimonio Industrial de la provincia de Alicante. Rehabilitación y nuevos usos, Investigaciones Geográficas 1998, 19, 49-66. [CrossRef]

- Hospers, G.J. Industrial heritage tourism and regional restructuring in the European Union. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2002, 10, 397–404. [CrossRef]

- Ćopić, S.; ĐorđevićA, J.; Lukić, T.; Stojanović, V.; Đukičin, S.; Besermenji, S.; ... Tumarić, A. Transformation of industrial heritage: An example of tourism industry development in the Ruhr area (Germany). Geographica Pannonica 2014, 18, 43–50.

- Pashkevich, A. Processes of reinterpretation of mining heritage: The case of Bergslagen, Sweden. AlmaTourism 2017, 8, 107–123. [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Suárez, M.; Caamaño-Franco, I. Theoretical and methodological model for the study of social perception of the impact of industrial tourism on local development. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 217. [CrossRef]

- Cañizares-Ruiz, M.C.; Benito-del-Pozo; Pascual-Ruiz-de-Valdepeñas, H. Los límites del turismo industrial en áreas desfavorecidas. Cuad. Geogr. 2019, 58, 180–204. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ballesteros, E.; Hernández-Ramírez, M. Identity and community—Reflections on the development of mining heritage tourism in Southern Spain. Tourism manage. 2007, 28, 677–687. [CrossRef]

- Du-Cros, H. A new model to assist in planning for sustainable cultural heritage tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2001, 3, 165–170. ttps://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.297.

- Ashworth, J.G. (2003). Heritage, identity and place: For tourists and host communities. In Tourism in destination communities; Singh, S., Timothy, D.J., Dowling, R.K., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2003; pp. 79–98.

- Aas, C.; Ladkin, A.; Fletcher, J. Stakeholder collaboration and heritage management. Ann. Touris. Res. 2005, 32, 28–48. [CrossRef]

- García-Delgado, F.J.; Martínez-Puche, A.; Lois-González, R.C. Heritage, Tourism and Local Development in Peripheral Rural Spaces: Mértola (Baixo Alentejo, Portugal). Sustainability 2020, 12, 9157. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.J.A. Entrepreneurialism, commodification and creative destruction: A model of post-modern community development. J. Rural Stud. 1998, 14, 273–286. [CrossRef]

- George, E.W.; Reid, D.G. The power of tourism: A metamorphosis of community culture. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2005, 3, 88–107. [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J.; Boyd, S.W. Heritage tourism in the 21st century: Valued traditions and new perspectives. J. Herit. Tour. 2006, 1, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Bangstad, T.R. Routes of Industrial Heritage: On the Animation of Sedentary Objects. Culture Unbound 2011, 3, 279–295. [CrossRef]

- Heldt-Cassel, S.; Pashkevich, A. World Heritage and tourism innovation: Institutional frameworks and local adaptation. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 1625–1640. [CrossRef]

- Acheson, C.R. Visiting the industrial revolution: The communication of world heritage values to tourists in Ironbridge Gorge. Doctoral Dissertation-University of Birmingham, Birmingham, 2019.

- Cañizares-Ruiz, M.C. Visibilidad y promoción del patrimonio minero en algunos geoparques españoles. Doc. d'Anàlisi Geogràfica 2020, 66, 109–131.

- Pardo-Abad, C.J. The post-industrial landscapes of Riotinto and Almadén, Spain: Scenic value, heritage and sustainable tourism. J. Heritage Tour. 2017, 12, 331–346. [CrossRef]

- Wanhill, S. Mines—A tourist attraction: Coal mining in industrial South Wales. J. Travel Res. 2000, 39, 60–69. [CrossRef]

- Blockley, M. Developing a Management Plan for the Ironbridge Gorge World Heritage Site. In Archaeology and the National Park Idea: Challenges for Management and Interpretation, 1999; pp. 107–120.

- Otgaar, A.H.J. Towards a common agenda for the development of industrial tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 4, 86–91. [CrossRef]

- Rutherford-Morrison, L. Playing Victorian: Heritage, Authenticity, and Make-Believe in Blists Hill Victorian Town, the Ironbridge Gorge. The Public Historian 2015, 37, 76–101.

- Dicks, B. Performing the hidden injuries of class in coal-mining heritage. Sociology 2008, 42, 436–452. [CrossRef]

- Kesküla, E. Reproducing Labor in the Estonian Industrial Heritage Museum, J. Baltic Stud. 2013, 44, 229–248. [CrossRef]

- Coupland, B.; Coupland, N. The authenticating discourses of mining heritage tourism in Cornwall and Wales. J. Socioling. 2014, 18, 495–517. [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. The experience industry and the creation of attractions. In Cultural attractions and european tourism; Richards, G., Ed.; CABI: Wallinford, UK, 2001; pp. 55–69.

- Napierała, T.; Leśniewska-Napierała, K.; Nalej, M.; Pielesiak, I. Co-evolution of tourism and industrial sectors: The case of the Bełchatów industrial district. European Spatial Research and Policy 2022, 29, 149–173. [CrossRef]

- Conlin, M.V.; Bird, G.R. (Eds.). (2014). Railway heritage and tourism: Global perspectives. Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2014.

- Cole, D. Exploring the Sustainability of Mining Heritage Tourism, J. Sustain. Tour. 2004, 12, 480–494. [CrossRef]

- Molin, T.; Müller, D.; Paju, M.; Pettersson, R. Kulturarvet och entreprenören – om nyskapat kulturarv i Västerbottens Guldrike. Riksantikvarieämbetet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2007.

- Boros, L.; Martyin, Z.; Pàl, V. Industrial tourism-trends and opportunities. Forum Geografic 2013, XII, 108–114.

- Barrado-Timón, D.; Hidalgo-Giralt, C.; Palacios-García, A. Despoblación y envejecimiento en las zonas mineras. ¿Es el turismo una solución? Casos de Riotinto (Huelva) y La Pernía-Barruelo (Palencia). In Despoblación, envejecimiento y territorio: Un análisis sobre la población española, XI Congreso de la Población Española, León, Spain, September 2008; López-Trigal, L., Abellán-García, A., Godenau, D. Coord.; Universidad de León: León, Spain, 2009, pp. 629–641.

- Jakobsson, M. Från industrier till upplevelser: En studie av symbolisk och materiell omvandling i Bergslagen, Doctoral Dissertation-Örebro Universitet, Örebro, 2009.

- Hortelano-Mínguez, L.A. Turismo minero en territorios en desventaja geográfica de Castilla y León: Recuperación del patrimonio industrial y opción de desarrollo local. Cuad. Tur. 2011, 27, 521–539.

- Carson, D.A.; Carson, D.B.; Lundmark, L. (2014). Tourism and mobilities in sparsely populated areas: Towards a framework and research agenda. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour., 14, 353–366.

- Carson, D.A. Challenges and opportunities for rural tourism geographies: A view from the ‘boring’peripheries. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 737–741. [CrossRef]

- Prideaux, B. Building visitor attractions in peripheral areas-Can uniqueness overcome isolation to produce viability? Int. J. Tour. Res., 2002, 4, 379–389. [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, D.; Malcolm, C.D. The importance of location and scale in rural and small town tourism product development: The case of the Canadian Fossil Discovery Centre, Manitoba, Canada. Can. Geogr.-Geogr. Can. 2017, 62, 250–265. [CrossRef]

- Hardy, A. Understanding self drive tourism. Rubber tire traffic: A case study of Bella Cool, British Columbia. In Informed Leisure Practice: Cases as Conduits Between Theory and Practice; Vaugenois, N.L., Ed.; Malaspina University-College: Nanaimo, Canada, 2006; Volume 2, pp. 46–51.

- Simoncini, R.; De-Groot, R.; Pinto-Correia, T. An integrated approach to assess options for multi-functional use of rural areas: Special issue “Regional Environmental Change”. Reg. Environ. Change 2009, 9, 139–141. [CrossRef]

- Ray, C. Towards a meta-framework of endogenous development: Repertoires, paths, democracy and rights. Sociol. Ruralis 1999, 39, 521–537. [CrossRef]

- Van-der-Ploeg, J.D.; Roep, D. (2003). Multifunctionality and rural development: The actual situation in Europe. Multifunctional agriculture: A new paradigm for European agriculture and rural development, van Huylenbroeck, G., Durand, G., Eds., Ashgate: Hampshire, UK, 2003; pp. 37–53.

- Ravazzoli, E.; Valero-López, D.E. Social Innovation: An Instrument to Achieve the Sustainable Development of Communities. In Sustainable Cities and Communities. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020.

- Belliggiano, A.; Cejudo-García, E.; Labianca, M.; Navarro-Valverde, F.; De-Rubertis, S. The “Eco-Effectiveness” of Agritourism Dynamics in Italy and Spain: A Tool for Evaluating Regional Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7080. [CrossRef]

- Bock, B.B. Rural marginalisation and the role of social innovation; a turn towards nexogenous development and rural reconnection. Sociol. Ruralis 2016, 56, 552–573. [CrossRef]

- Bohlin, M.; Brandt, D.; Elbe, J. Tourism as a vehicle for regional development in peripheral areas–myth or reality? A longitudinal case study of Swedish regions. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2016, 24, 1788–1805. [CrossRef]

- Lichrou, M.; O'malley, L. Mining and tourism: Conflicts in the marketing of Milos Island as a tourism destination, Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development 2006, 3, 35–46. [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Pham, T.; Jago, L.; Bailey, G.; Marshall, J. Modeling the impact of Australia’s mining boom on tourism: A classic case of Dutch disease. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55(2), 233–245. [CrossRef]

- Rudd, M.A.; Davis, J.A. Industrial heritage tourism at the Bingham Canyon copper mine. J. Travel Res. 1998, 36, 85–89. [CrossRef]

- Pardo-Abad, C.J. Indicadores de sostenibilidad turística aplicados al patrimonio industrial y minero: Evaluación de resultados en algunos casos de estudio. Bol. Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2014, 65,11–36. [CrossRef]

- García-Delgado, F.J.; Delgado-Domínguez, A.; Felicidades-García, J. El turismo en la cuenca minera de Riotinto. Cuad. Tur. 2013, 31, 129–152.

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; Sage: LA, USA, 2018.

- Bahamonde-Rodríguez, M.; García-Delgado, F.J.; Šadeikaitė, G. Sustainability and Tourist Activities in Protected Natural Areas: The Case of Three Natural Parks of Andalusia (Spain). Land 2022, 11, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Perfetto, M.C.; Vargas-Sánchez, A. Towards a Smart Tourism Business Ecosystem based on Industrial Heritage: Research perspectives from the mining region of Rio Tinto, Spain. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 528–549. [CrossRef]

- Bahamonde-Rodríguez, M.; Šadeikaitė, G.; García-Delgado, F.J. (2023). The effects of tourism on local development in protected nature areas: The case of three nature parks of the Sierra Morena (Andalusia, Spain). Land 2023, 12, 898. [CrossRef]

- Censos de Población y Viviendas. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/inebase/es/operacion.htm?c=estadistica_c&cid=1254736176992&menu=ultidatos&idp=1254735572981 (accesessed on 12 October 2023).

- Sistema de Información Multiterritorial de Andalucía. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia/badea/informe/anual?CodOper=b3_151&idNode=23204 (accesessed on 12 October 2023).

- Buscador de Establecimientos y Servicios Turísticos. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/organismos/turismoculturaydeporte/areas/turismo/registro-turismo/buscador-establecimientos-servicios-turisticos.html (accesessed on 12 October 2023).

- Delgado-Domínguez, A. (2020). Cuenca Minera de Riotinto (Huelva), paisaje hecho a mano. In I Simposio Anual de Patrimonio Natural y Cultural, Madrid, Spain, November 21-23; ICOMOS España: Madrid, Spain, 2020.

- Delgado-Domínguez, A. El Parque Minero de Riotinto: Museo Minero, Casa nº 21, Peña de Hierro y FFCC Turístico Minero. In Activos ambientales de la Minería Española; Fernández-Rubio, R., Ed.; TIASA: Madrid, Spain, 2007, pp. 120-137.

- Peña-Guerrero, M.A. Caciquismo y poder empresarial. El papel político de las compañías mineras en la provincia de Huelva (1898–1923). Trocadero 1993, 5, 299–324.

- Foronda-Robles, C.; Joya-Reina, M.P. Características del tejido empresarial en la Cuenca Minera de Riotinto (Andalucía). In Innovación tecnológica, servicios a las empresas y desarrollo territorial; Manero, F., Pascual, H., Coorts., Universidad de Valladolid: Valladolid, Spain, 2005; pp. 293–308.

- Campos-Torrado, A.; Delgado-Domínguez, A. (2011). Ferrocarril turístico minero, Parque Minero de Riotinto (Huelva, España). In Río Tinto: Historia, patrimonio minero y turismo cultural; Pérez-Macías, J.A., Delgado-Domínguez, A., Pérez-López, J.M., García-Delgado, F.J., Eds.; Universidad de Huelva: Huelva, Spain, 2011; pp. 575-593.

- Cabello-López, F.J. (Dir.) 30. Fundación Río Tinto 1987-2017. Conservando una historia milenaria, Fundación Río Tinto, Spain, 2017.

- Cabello-López, F.J.; García-Delgado, F.J.; Delgado-Domínguez, A. La crisis económica en territorios en crisis estructural. Instrumento de desarrollo en la Cuenca Minera de Riotinto. In Profesionales y herramientas para el desarrollo local y sus sinergias, Actas IX Coloquio Nacional de Desarrollo Local, Alicante, Spain, June 6-8, 2013; Universidad de Alicante: Alicante, Spain, 2016; pp. 367-384.

- Asprogerakas, E.; Mountanea, K. (2020). Spatial strategies as a place branding tool in the region of Ruhr. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 2020, 16, 336–347. [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. Seven questions in the economics of cultural heritage. In Economic Perspectives on Cultural Heritage; Hutter, M., Rizzo, I., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1997; pp. 13–30. [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B.; Fyall, A. Managing heritage tourism. Ann. Touris. Res. 2000, 27, 682–708. [CrossRef]

- Conlin, M.V.; Jolliffe, L. (Eds.). Mining heritage and tourism: A global synthesis. Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010.

- Bhati, A.; Pryce, J.; Chaiechi, T. Industrial railway heritage trains: The evolution of a heritage tourism genre and its attributes. J. Travel Res. 2014, 9(2), 114–133. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Domínguez, A.; Regalado-Ortega, M.C. Casa nº 21 de Bella Vista (Minas de Riotinto). Sección etnográfica del Museo Minero de Riotinto. In Río Tinto: Historia, patrimonio minero y turismo cultural; Pérez-Macías, J.A., Delgado-Domínguez, A., Pérez-López, J.M., García-Delgado, F.J., Eds.; Universidad de Huelva: Huelva, Spain, 2011; pp. 519–527.

- Parque Minero de Riotinto. Available online: https://parquemineroderiotinto.es/ (accesessed on 12 October 2023).

- Mitchell, C.J.A. Creative destruction or creative enhancement? Understanding the transformation of rural spaces. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 32, 375–387. [CrossRef]

- López-Archilla, A.I. Riotinto: Un universo de mundos microbianos. Ecosistemas 2005, 14, 51–63.

- Loulanski, T.; Loulanski, V. The sustainable integration of cultural heritage and tourism: A meta-study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 837–862. [CrossRef]

- Hortelano-Mínguez, L.A.; Plaza-Gutiérrez, J.I. (2004). Valoración de algunas propuestas de desarrollo en la Montaña palentina a partir de la promoción de iniciativas turísticas vinculadas al patrimonio minero. Publicaciones de la Institución Tello Téllez de Meneses 2004, (75), 413–433.

- Fundación Riotinto. Memoria de Actividades 2022. Available online: https://fundacionriotinto.es/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Memoria-Actividades-FRT-2022_Para-Web.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Kerstetter, D.; Confer, J.; Bricker, K. Industrial Heritage Attractions: Types and Tourists, J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1998, 7, 91–104. [CrossRef]

- Frost, W.; Laing, J.H. Children, families and heritage, J. Travel Res. 2017, 12, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Jeuring, J.H.G.; Díaz-Soria, I.. Introduction: Proximity and intraregional aspects of tourism, Tourism Geogr. 2017, 19, 4–8. [CrossRef]

- Brouder, P. Tourism Development Against the Odds: The Tenacity of Tourism in Rural Areas, Tourism Planning & Development 2012, 9, 333–337. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Sánchez, A.; Plaza-Mejía, M.A.; Porras-Bueno, N. Understanding residents’ attitudes toward the development of industrial tourism in a former mining community. J. Travel Res. 2009, 47, 373–387. [CrossRef]

- Fundación Atalaya Riotinto. Memoria #2018. Avaiable online: https://riotinto.atalayamining.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/FAR-Memoria-2018-Final-WEB.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Holcombe, S.; Keenan, J. Mining as a temporary land use scoping project: Transitions and repurposing. The University of Queensland: Brisbane, Australia, 2020.

- Rizzardo, R. Tourisme culturel: Un élément d’aménagement du territoire. Cahier Espaces 1994, 37, 88-92.

- Managing Tourism at Places of Heritage Significance, 1999. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/newsletters-archives/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/162-international-cultural-tourism-charter (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Hewison, R. The Heritage Industry; Methuen: London, UK, 1987.

- CEI-Patriomonio. Available online: https://www.ceipatrimonio.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/12206013-RIO-TINTO-CERTIFICADO-SGSP-rev13032023-VALIDADO-POR-CEI-modificado.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Harfst, J.; Wust, A.; Nadler, R. Conceptualizing industrial culture. GeoScape 2018, 12, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Maguire, K. Examining the power role of Local Authorities in planning for socio-economic event impacts. Local Economy 2019, 34, 657–679. [CrossRef]

- Jansen-Verbeke, M. The territoriality paradigm in cultural tourism. Turyzm 2009, 19, 25–31. [CrossRef]

- Cañizares-Ruiz, M.C. Protección y defensa del patrimonio minero en España. Scr. Nova 2011, 15.

- Angelstam, P.; Andersson, K.; Isacson, M.; Gavrilov, D.V.; Axelsson, R.; Bäckström, M.; ... Törnblom, J. Learning about the history of landscape use for the future: Consequences for ecological and social systems in Swedish Bergslagen. Ambio 2013, 42, 146–159. [CrossRef]

- Stihl, L. Local culture and change agency in old industrial places: Spinning forward and digging deeper. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2023, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Bowitz, E.; Ibenholt, K. (2009). Economic impacts of cultural heritage–Research and perspectives. J. Cult. Herit. 2009, 10, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Atalaya Mining. Informe de sostenibilidad 2021. Available online: https://riotinto.atalayamining.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Informe_Sostenibilidad_ES.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2023).

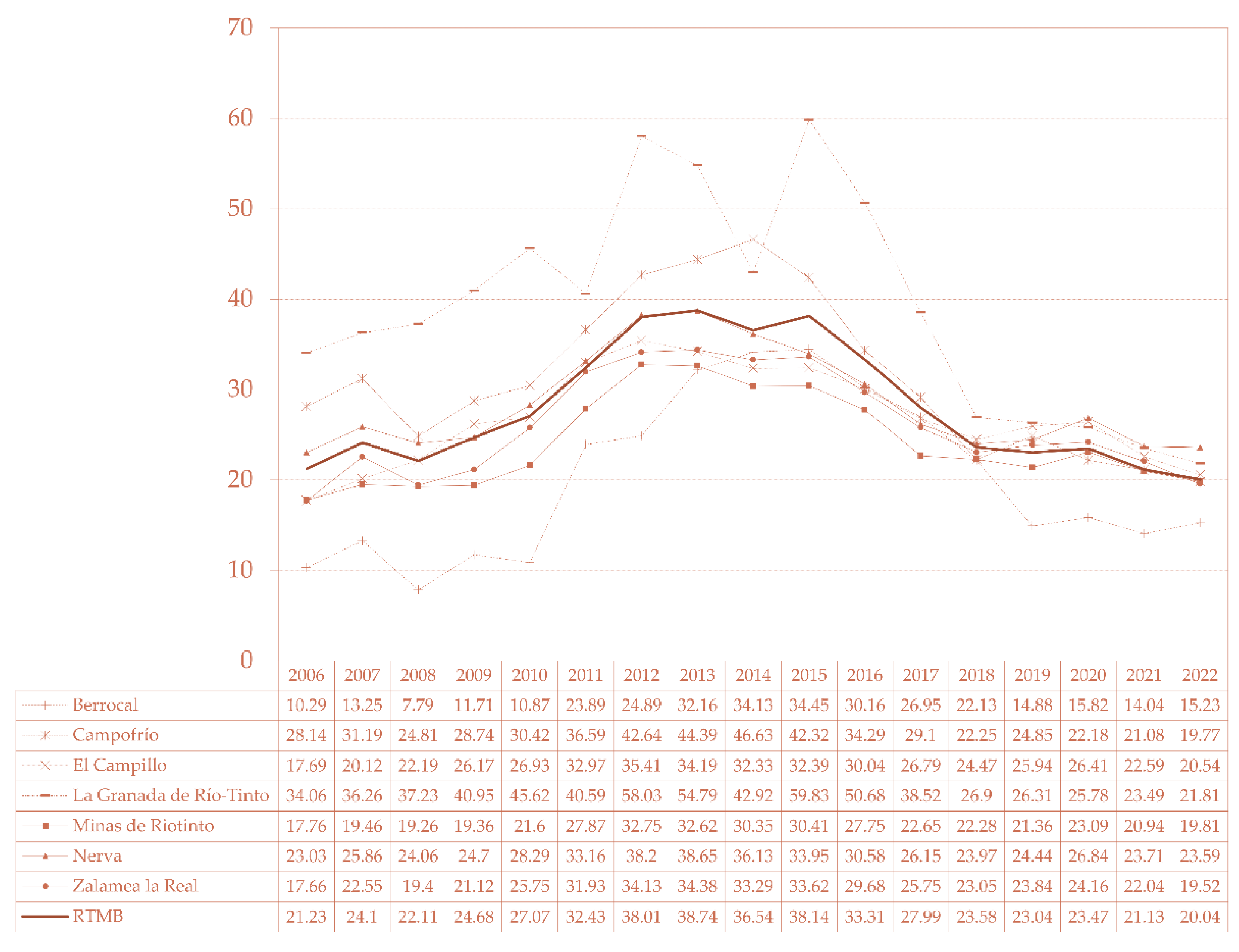

- Tasa de paro registrado (2006-2022). Available online: https://datosmacro.expansion.com/paro/espana/municipios/andalucia/huelva/ (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Monteserín-Abella, O. Espacios patrimoniales de intervención múltiple. Conflictos territoriales en torno al Plan de Dinamización Turística de las Médulas. PASOS 2019, 17, 209–224.

- Alfrey, J.; Putnam, T. The industrial heritage. Managing resources and uses. London: Routledge: London, UK, 1992.

- Decreto 504/2012, de 16 de octubre, por el que se inscribe en el Catálogo General del Patrimonio Histórico Andaluz como Bien de Interés Cultural, con la tipología de Zona Patrimonial, la Cuenca Minera de Riotinto-Nerva, en los términos municipales de Minas de Riotinto, Nerva y El Campillo (Huelva). Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2012/208/20 (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Ruhanen, L. Local government: Facilitator or inhibitor of sustainable tourism development? J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21(1), 80–98. [CrossRef]

- Vukosav, S.; Garača, V.; Ćurčić, N.; Bradić, M. Industrial Heritage of Novi Sad in the Function of Industrial Tourism: The Creation of New Tourist Products. Int. Sci. Conf. Geobalcanica 2015, 495–502. [CrossRef]

| Code | Question | Topics |

|---|---|---|

| q1 | What role does your entity have in tourism in the RTMB? | (a)(c) |

| q2 | Do you identify your territory with mining tourism? Why? | (a)(b)(c)(d) |

| q3 | What projects have you launched (or supported) for the heritage/tourism enhancement of the region/municipality? | (a)(b)(c) |

| q4 | What heritage projects/tourism enhancement does your entity plan (or will support) in the region/municipality? | (a)(b)(c)(d) |

| q5 | Who should we look to for the development of tourism? | (a)(b)(d) |

| q6 | What functions does the Río Tinto Foundation have in the destination? Which are, from your point of view, the most important? | (a)(b)(d) |

| q7 | What singularities does the mining tourism management model have in the region? | (b)(c)(d) |

| q8 | What are the instruments used for the development of mining tourism? | (b)(c)(d) |

| q9 | What can you say about promoting and developing tourist activities (companies and products) in the region? | (b)(c)(d) |

| q10 | What projects related to tourism (or not) have been launched in your municipality? | (b)(c)(d) |

| q11 | What is the future of mining tourism, given the reactivation of mining? | (a)(b)(c)(d) |

| q12 | What has been the situation of tourism activity during the COVID-19 pandemic? | (b)(c)(d) |

| q13 | Future proposals for improving tourism in the region | (a)(b)(c)(d) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).