Submitted:

12 October 2023

Posted:

13 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Agro-Industrial Waste-Based Fertilizer manufacturing

2.2. Soil treatment

- A)

- 1.2 g of synthetic fertilizer NPK (15-15-15) in which there are 0.18 g of N, 0.18 g of P2O5 and 0.18 g of K2O.

- B)

- 13 g of organic fertilizer, in which there are 0.26 g of N, 0.26 g of P2O5 and 0.195 g of K2O. In this fertilizer there are bovine, equine, sheep and poultry manure mixed with litter, calcium sulphate and olive pomace dust mixed at the total percentage of 50 % on composition.

- C)

- 1.4 g of fertilizer Sulfur-bentonite + orange waste.

2.3. Soil physical, chemical, and biochemical analysis before and after treatment

| SOIL 1 | SOIL 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Skeleton (%) | 45 | 21 |

| Sandy % | 65 | 50 |

| Clay % | 23 | 27 |

| Loam % | 12 | 23 |

| Textural Class | Sandy-loam | Sandy-Clay-loam |

| Moisture % | 18 | 32 |

| S.S (%) | 82 | 68 |

| pH (H2O) | 8.5 | 8.3 |

| pH (KCl) | 7.8 | 7.3 |

| EC (μS/cm) | 107.3 | 302 |

| CEC (cmol(+) kg-1) | 21.57 | 27.71 |

| TOC % | 1.78 | 1.98 |

| TN % | 0.19 | 0.2 |

| C/N | 9.37 | 9.9 |

| SOM % | 3.07 | 3.41 |

| WSP (µg GAE g-1 d.s) | 56.1 | 85.62 |

| MBC (μg C g−1 soil) | 896 | 941 |

| SOIL 1 | SOIL 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| DHA | 1.31 | 2.83 |

| CAT | 1.54 | 3.85 |

| FDA | 8.93 | 15.10 |

| ß-GLU | 514 | 348 |

| PRO | 167 | 157 |

| URE | 312 | 289 |

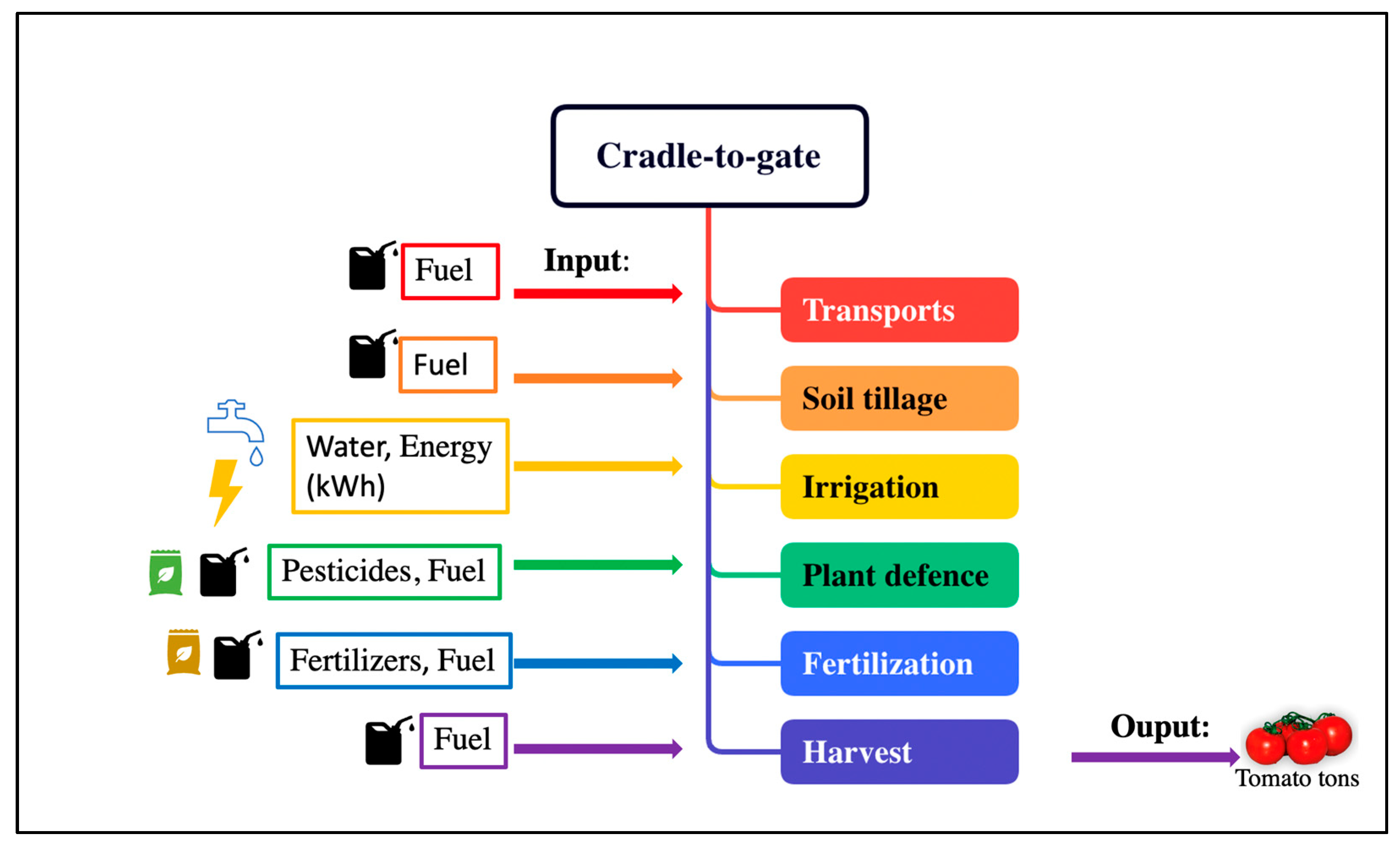

2.4. Environmental impact: Carbon and Water footprint.

2.4.1. Carbon Footprint

| CTR | A | B | C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fertilizers (kg ha-1) | ||||

| NPK | 170 | |||

| Horse Manure | 430 | |||

| Sulfur Bentonite + Orange waste | 476 | |||

| Chemicals (kg ha-1) | ||||

| Primor 50 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| Daramun | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Human labour (h ha-1) | 45 | 46 | 48 | 46 |

| Machinery (h ha-1) | 5 | 10 | 12 | 10 |

| Diesel (kg ha-1) | 10 | 13 | 15 | 13 |

| Water (m3 ha-1) | 750 | 750 | 750 | 750 |

| Electricity (kWh kg-1) | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| Production (t ha-1) | 47 | 57.5 | 58 | 58.4 |

2.4.2. Water Footprint

- ETgreen was calculated as the minimum of Crop WaterRequirement (CWR, mm year−1) and effective precipitation (Peff, mm year−1).

- ETblue was estimated from Irrigation Requirement (IR) rates as the minimum betweenIR (m3 year−1) and the irrigation volume (Ieff, m3 ha−1 year−1). [51].

- IR was calculated as a constant value for the analyzed systems according to the following equation: IR = max (0; CWR-Peff)

- AR is the chemical application rate to the field per hectare (kg ha−1);

- α is the leaching-run-off fraction;

- cmax is the maximum acceptable concentration for the pollutant considered (kg m−3);

- cnat is the natural concentration for the pollutant considered (kg m−3);

- Y is the crop yield (tons ha−1).

3. Results

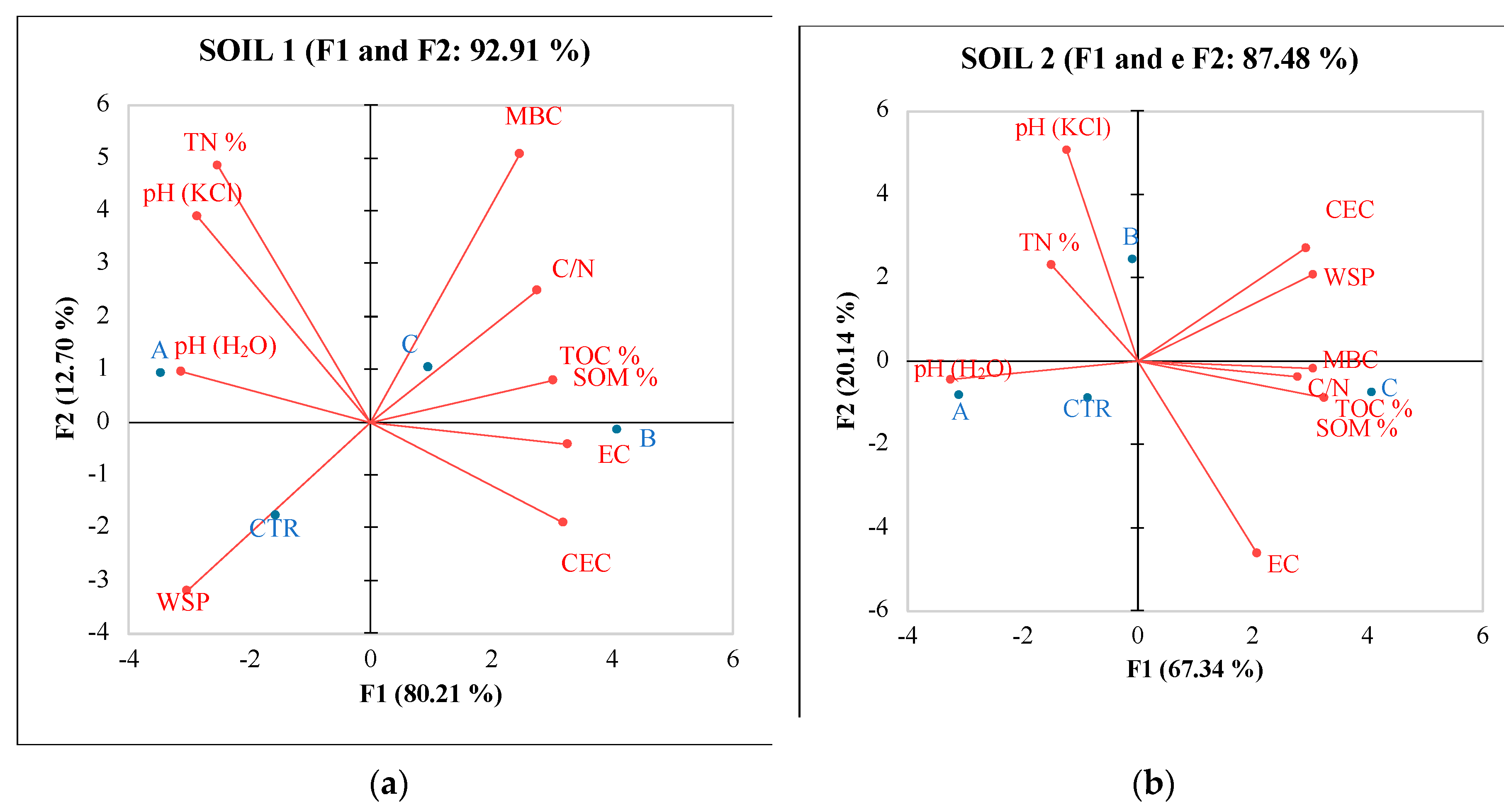

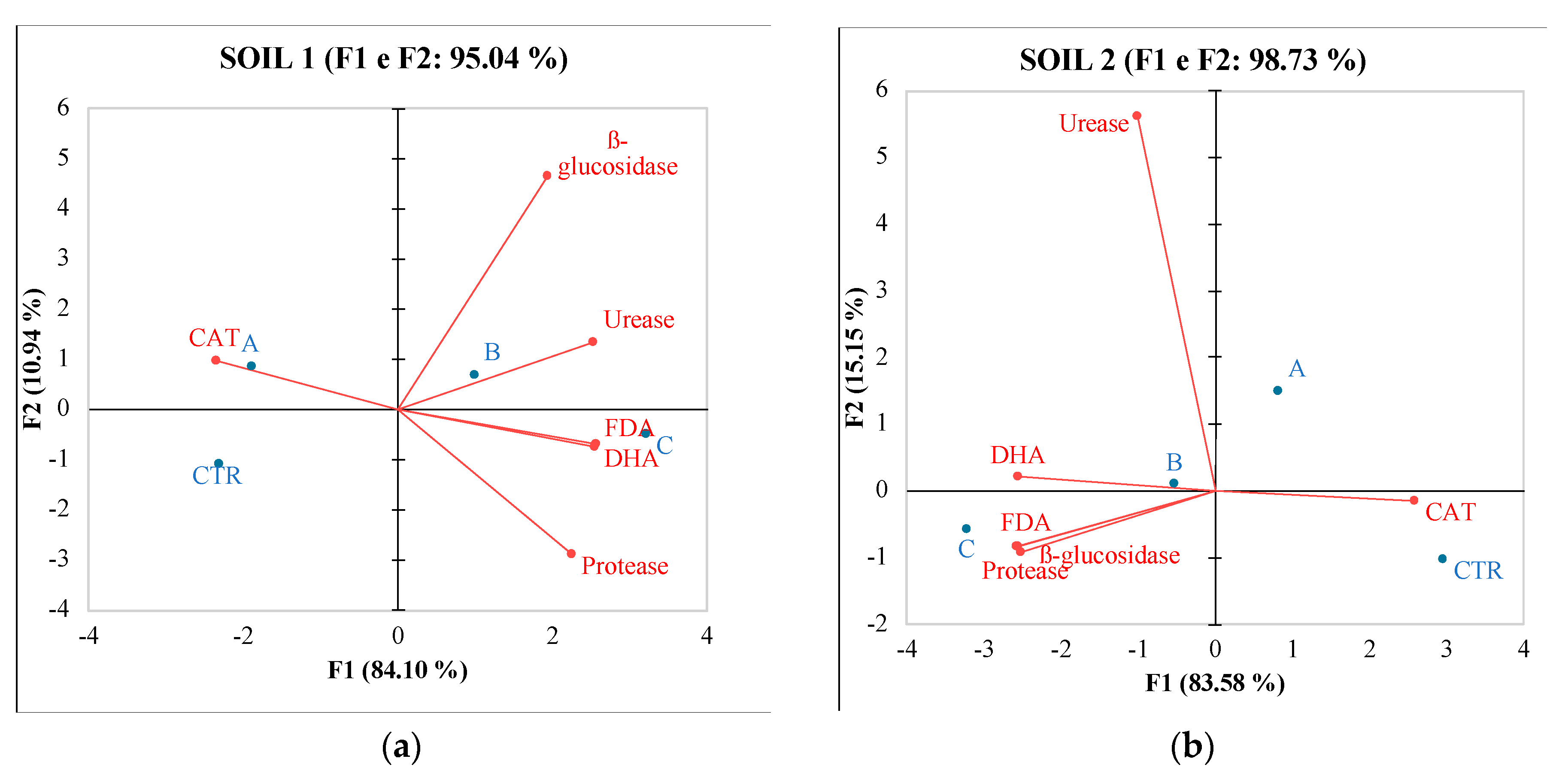

3.1. Effect of different fertilizers on soils quality

| CTR | A | B | C | CTR | A | B | C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil 1 | Soil 2 | |||||||

| Skeleton (%) | 45a | 45a | 45a | 45a | 21a | 21a | 21a | 21a |

| Sandy % | 65a | 65a | 65a | 65a | 50a | 50a | 50a | 50 a |

| Clay % | 23a | 23a | 23a | 23a | 27a | 27a | 27a | 27a |

| Loam % | 12a | 12a | 12a | 12a | 23a | 23a | 23a | 23a |

| Textural Class | Sandy-loam | Sandy-loam | Sandy-loam | Sandy-loam | Sandy-Clay-loam | Sandy-Clay-loam | Sandy-Clay-loam | Sandy-Clay-loam |

| pH (H2O) | 8.3a | 8.76a | 8.0b | 7.82b | 8.2a | 8.43a | 7.89ab | 7.2b |

| pH (KCl) | 7.70a | 7.85a | 7.75a | 7.58b | 7.2a | 7.1ab | 7.4a | 6.98b |

| EC (μS/cm) | 106b | 123ab | 132a | 142a | 298a | 291ab | 267b | 326a |

| CEC | 20.65b | 22.87b | 23.65ab | 28.56a | 26.61b | 24.23b | 26.45b | 31.56a |

| TOC % | 1.67b | 1.45b | 2.02a | 2.03a | 1.51b | 1.25b | 1.98a | 2.12a |

| TN % | 0.14a | 0.17a | 0.16a | 0.12ab | 0.12b | 0.21a | 0.19a | 0.15b |

| C/N | 11.93b | 8.53c | 12.63b | 16.92a | 12.58a | 5.95c | 10.42b | 14.13a |

| SOM % | 2.88b | 2.50b | 3.48a | 3.50a | 2.60ab | 2.16b | 3.41a | 3.65a |

| WSP (µg GAE*g-1 d.s) | 55.68a | 55.23a | 52.45b | 51.53b | 82.67b | 79.81b | 91.76a | 97.23a |

| MBC μg C g−1 soil | 901b | 876b | 926a | 976a | 945b | 965b | 1023ab | 1198a |

| CTR | A | B | C | CTR | A | B | C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil 1 | Soil 2 | |||||||

| DHA | 1.29b | 1.34b | 1.59ab | 2.01a | 2.69b | 3.1ab | 3.5a | 3.8a |

| FDA | 8.56b | 8.51b | 9.01a | 9.34a | 14.5b | 15.51b | 17.01a | 19.14a |

| CAT | 1.34a | 1.51a | 1.01b | 0.96b | 2.84a | 2.51a | 2.41a | 1.96b |

| ßGLU | 510a | 546a | 555a | 557a | 355b | 365b | 372ab | 401a |

| PRO | 165b | 157b | 167b | 212a | 145b | 157b | 177a | 201a |

| URE | 298b | 312ab | 351b | 365b | 258b | 297a | 281a | 279a |

| from\ to | pH (H2O) | pH (KCl) | EC | CEC | TOC % | TN % | C/N | SOM % | WSP | MBC | DHA | FDA | CAT | ßGLU | PRO | URE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH (H2O) | 1 | 0.853 | -0.581 | -0.638 | -0.974 | 0.724 | -0.938 | -0.974 | 0.845 | -0.931 | -0.806 | -0.902 | 0.972 | -0.344 | -0.768 | -0.792 |

| pH (KCl) | 0.853 | 1 | -0.398 | -0.649 | -0.718 | 0.978 | -0.965 | -0.718 | 0.618 | -0.904 | -0.770 | -0.771 | 0.735 | -0.075 | -0.902 | -0.560 |

| EC | -0.581 | -0.398 | 1 | 0.923 | 0.666 | -0.278 | 0.600 | 0.666 | -0.922 | 0.738 | 0.891 | 0.865 | -0.719 | 0.944 | 0.700 | 0.952 |

| CEC | -0.638 | -0.649 | 0.923 | 1 | 0.635 | -0.586 | 0.768 | 0.635 | -0.871 | 0.858 | 0.970 | 0.897 | -0.698 | 0.761 | 0.905 | 0.884 |

| TOC % | -0.974 | -0.718 | 0.666 | 0.635 | 1 | -0.556 | 0.857 | 1.000 | -0.902 | 0.884 | 0.795 | 0.911 | -0.996 | 0.488 | 0.679 | 0.862 |

| TN % | 0.724 | 0.978 | -0.278 | -0.586 | -0.556 | 1 | -0.894 | -0.556 | 0.468 | -0.814 | -0.682 | -0.647 | 0.578 | 0.055 | -0.875 | -0.411 |

| C/N | -0.938 | -0.965 | 0.600 | 0.768 | 0.857 | -0.894 | 1 | 0.857 | -0.802 | 0.983 | 0.888 | 0.909 | -0.877 | 0.311 | 0.932 | 0.755 |

| SOM % | -0.974 | -0.718 | 0.666 | 0.635 | 1.000 | -0.556 | 0.857 | 1 | -0.902 | 0.884 | 0.795 | 0.911 | -0.996 | 0.488 | 0.679 | 0.862 |

| WSP | 0.845 | 0.618 | -0.922 | -0.871 | -0.902 | 0.468 | -0.802 | -0.902 | 1 | -0.894 | -0.935 | -0.977 | 0.932 | -0.791 | -0.771 | -0.996 |

| MBC | -0.931 | -0.904 | 0.738 | 0.858 | 0.884 | -0.814 | 0.983 | 0.884 | -0.894 | 1 | 0.954 | 0.969 | -0.913 | 0.482 | 0.943 | 0.860 |

| DHA | -0.806 | -0.770 | 0.891 | 0.970 | 0.795 | -0.682 | 0.888 | 0.795 | -0.935 | 0.954 | 1 | 0.974 | -0.843 | 0.691 | 0.940 | 0.928 |

| FDA | -0.902 | -0.771 | 0.865 | 0.897 | 0.911 | -0.647 | 0.909 | 0.911 | -0.977 | 0.969 | 0.974 | 1 | -0.942 | 0.672 | 0.880 | 0.960 |

| CAT | 0.972 | 0.735 | -0.719 | -0.698 | -0.996 | 0.578 | -0.877 | -0.996 | 0.932 | -0.913 | -0.843 | -0.942 | 1 | -0.537 | -0.728 | -0.896 |

| ßGLU | -0.344 | -0.075 | 0.944 | 0.761 | 0.488 | 0.055 | 0.311 | 0.488 | -0.791 | 0.482 | 0.691 | 0.672 | -0.537 | 1 | 0.428 | 0.843 |

| PRO | -0.768 | -0.902 | 0.700 | 0.905 | 0.679 | -0.875 | 0.932 | 0.679 | -0.771 | 0.943 | 0.940 | 0.880 | -0.728 | 0.428 | 1 | 0.749 |

| URE | -0.792 | -0.560 | 0.952 | 0.884 | 0.862 | -0.411 | 0.755 | 0.862 | -0.996 | 0.860 | 0.928 | 0.960 | -0.896 | 0.843 | 0.749 | 1 |

| pH (H2O) | pH (KCl) | EC | CEC | TOC % | TN % | C/N | SOM % | WSP | MBC | DHA | FDA | CAT | ßGLU | PRO | URE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH (H2O) | 1 | 0,360 | -0,583 | -0,966 | -0,914 | 0,314 | -0,765 | -0,914 | -0,961 | -0,964 | -0,824 | -0,922 | 0,849 | -0,923 | -0,919 | 0,127 |

| pH (KCl) | 0,360 | 1 | -0,924 | -0,491 | 0,048 | 0,191 | -0,173 | 0,048 | -0,111 | -0,514 | -0,207 | -0,349 | 0,472 | -0,524 | -0,315 | -0,168 |

| EC | -0,583 | -0,924 | 1 | 0,737 | 0,216 | -0,506 | 0,536 | 0,216 | 0,337 | 0,645 | 0,254 | 0,445 | -0,495 | 0,606 | 0,415 | -0,163 |

| CEC | -0,966 | -0,491 | 0,737 | 1 | 0,816 | -0,511 | 0,853 | 0,816 | 0,867 | 0,918 | 0,666 | 0,814 | -0,745 | 0,856 | 0,805 | -0,286 |

| TOC % | -0,914 | 0,048 | 0,216 | 0,816 | 1 | -0,228 | 0,726 | 1,000 | 0,984 | 0,814 | 0,807 | 0,846 | -0,718 | 0,769 | 0,858 | -0,182 |

| TN % | 0,314 | 0,191 | -0,506 | -0,511 | -0,228 | 1 | -0,832 | -0,228 | -0,176 | -0,131 | 0,278 | 0,075 | -0,189 | 0,001 | 0,084 | 0,934 |

| C/N | -0,765 | -0,173 | 0,536 | 0,853 | 0,726 | -0,832 | 1 | 0,726 | 0,693 | 0,592 | 0,285 | 0,458 | -0,314 | 0,476 | 0,455 | -0,735 |

| SOM % | -0,914 | 0,048 | 0,216 | 0,816 | 1,000 | -0,228 | 0,726 | 1 | 0,984 | 0,814 | 0,807 | 0,846 | -0,718 | 0,769 | 0,858 | -0,182 |

| WSP | -0,961 | -0,111 | 0,337 | 0,867 | 0,984 | -0,176 | 0,693 | 0,984 | 1 | 0,903 | 0,878 | 0,925 | -0,826 | 0,871 | 0,932 | -0,073 |

| MBC | -0,964 | -0,514 | 0,645 | 0,918 | 0,814 | -0,131 | 0,592 | 0,814 | 0,903 | 1 | 0,887 | 0,968 | -0,948 | 0,991 | 0,961 | 0,109 |

| DHA | -0,824 | -0,207 | 0,254 | 0,666 | 0,807 | 0,278 | 0,285 | 0,807 | 0,878 | 0,887 | 1 | 0,974 | -0,960 | 0,922 | 0,979 | 0,413 |

| FDA | -0,922 | -0,349 | 0,445 | 0,814 | 0,846 | 0,075 | 0,458 | 0,846 | 0,925 | 0,968 | 0,974 | 1 | -0,978 | 0,980 | 0,999 | 0,261 |

| CAT | 0,849 | 0,472 | -0,495 | -0,745 | -0,718 | -0,189 | -0,314 | -0,718 | -0,826 | -0,948 | -0,960 | -0,978 | 1 | -0,982 | -0,973 | -0,413 |

| ßGLU | -0,923 | -0,524 | 0,606 | 0,856 | 0,769 | 0,001 | 0,476 | 0,769 | 0,871 | 0,991 | 0,922 | 0,980 | -0,982 | 1 | 0,973 | 0,245 |

| PRO | -0,919 | -0,315 | 0,415 | 0,805 | 0,858 | 0,084 | 0,455 | 0,858 | 0,932 | 0,961 | 0,979 | 0,999 | -0,973 | 0,973 | 1 | 0,259 |

| URE | 0,127 | -0,168 | -0,163 | -0,286 | -0,182 | 0,934 | -0,735 | -0,182 | -0,073 | 0,109 | 0,413 | 0,261 | -0,413 | 0,245 | 0,259 | 1 |

3.2. Environmental impact

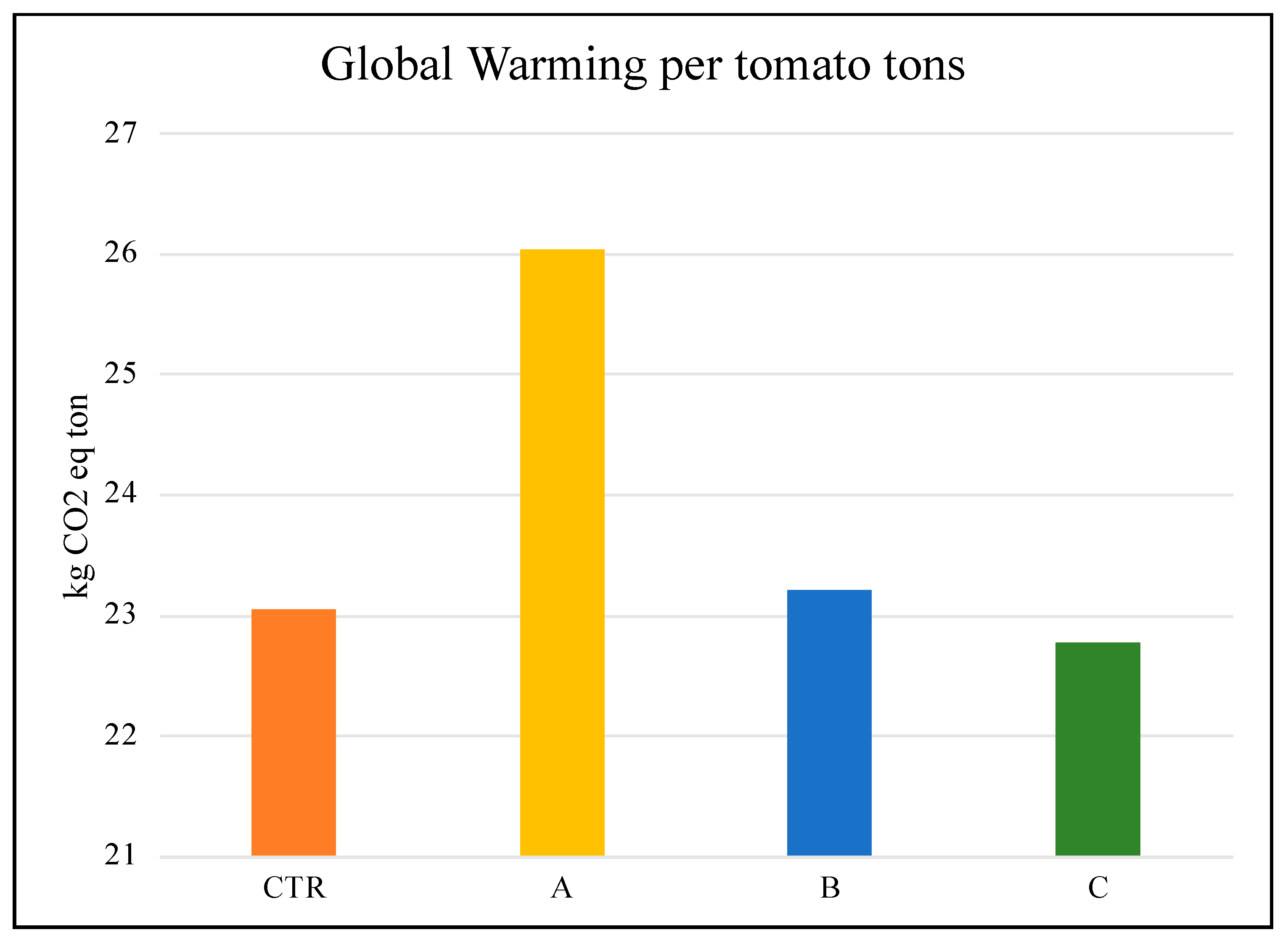

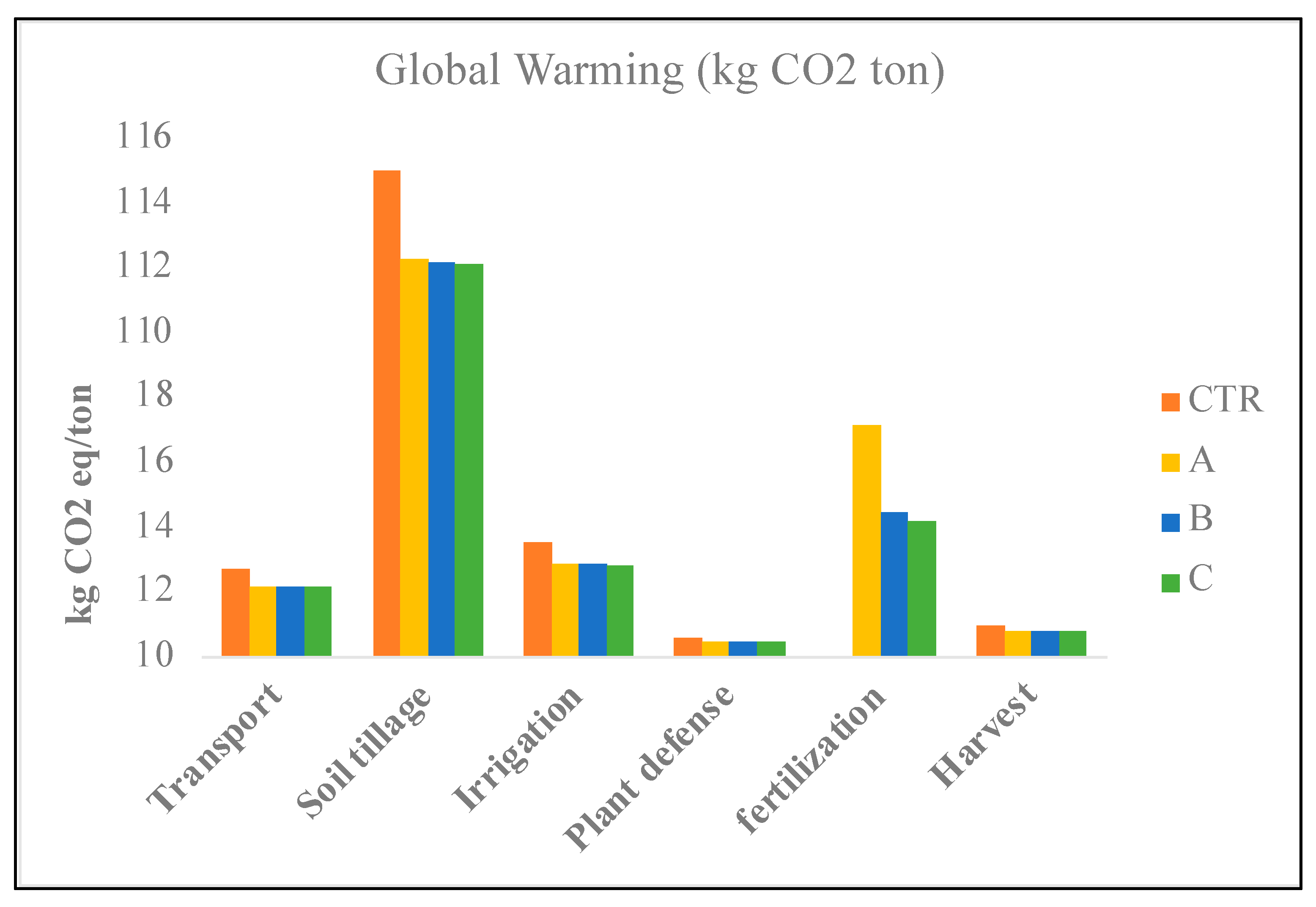

3.2.1. Carbon Footprint

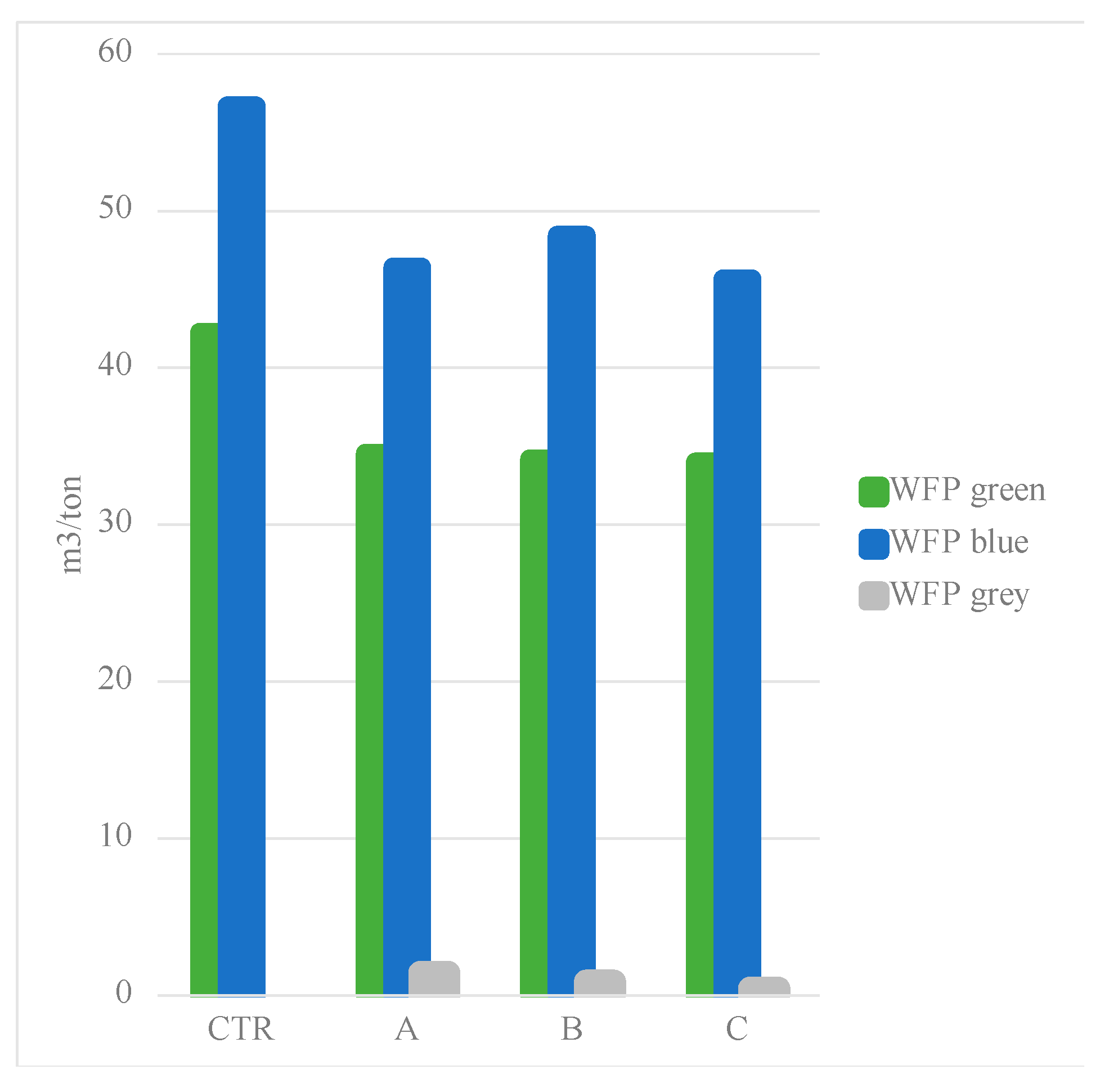

3.2.2. Water Footrpint

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of different fertilizers on soils quality

4.2. Environmental impact

4.2.1. Carbon Footprint

4.2.2. Water Footprint

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosenzweig, C.; Mbow, C.; Barioni, L.G.; Benton, T.G.; Herrero, M.; Krishnapillai, M.; Liwenga, E.T.; Pradhan, P.; Rivera-Ferre, M.G.; Sapkota, T.; et al. Climate change responses benefit from a global food system approach. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blandford, D.; Hassapoyannes, K. The Role of Agriculture in Global GHG Mitigation; Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rouwenhorst, K.H.R.; Travis, A.S.; Lefferts, L. 1921–2021: A Century of Renewable Ammonia Synthesis. Sustain. Chem. 2022, 3, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.; Teitge, J.; Mielke, J.; Schütze, F.; Jaeger, C. The European Green Deal—More Than Climate Neutrality. Intereconomics 2021, 56, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlesinger, W.H.; Andrews, J.A. Soil respiration and the global carbon cycle. Biogeochemistry 2000, 48, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.Y.; He, K.H.; Lin, K.T.; Fan, C.; Chang, C.-T. Addressing nitrogenous gases from croplands toward low-emission agriculture. npj Clim Atmos Sci. 2022, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinckley, E.L.S.; Crawford, J.T.; Fakhraei, H.; Driscoll, C.T. A shift in sulfur-cycle manipulation from atmospheric emissions to agricultural additions. Nat. Geosci. 2020, 13, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneklaus, S.; Bloem, E.; Schnug, E. History of Sulfur Deficiency in Crops. In Sulfur: A Missing Link between Soils, Crops, and Nutrition; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; Volume 50, pp. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Głowacka, A.; Gruszecki, T.; Szostak, B.; Michałek, S. The response of common bean to sulphur and molybdenum fertilization. Int. J. Agron. 2019, 2019, 3830712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głowacka, A.; Jariene, E.; Flis-Olszewska, E.; KiełtykaDadasiewicz, A. The Effect of Nitrogen and Sulphur Application on Soybean Productivity Traits in Temperate Climates Conditions. Agronomy 2023, 13, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandurangan, S.; Sandercock, M.; Beyaert, R.; Conn, K.L.; Hou, A.; Marsolais, F. Differential response to sulfur nutrition of two common bean genotypes differing in storage protein composition. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulczycki, G. The Effect of Elemental Sulfur Fertilization on Plant Yields and Soil Properties. In Advances in Agronomy; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; ISBN 0065-2113. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, K.M.; Khan, K.S.; Billah, M.; Akhtar, M.S.; Rukh, S.; Alam, S.; Munir, A.; Mahmood Aulakh, A.; Rahim, M.; Qaisrani, M.M.; et al. Organic Amendments and Elemental Sulfur Stimulate Microbial Biomass and Sulfur Oxidation in Alkaline Subtropical Soils. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Chen, H.; Gong, Y.; Yang, H.; Fan, M.; Kuzyakov, Y. Effects of 15 years of manureand mineral fertilizers on enzyme activities in particle-size fractions in a North China Plain soil. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2014, 60, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhongqi, H.E.; Pagliari, P.H.; Waldrip, H.M. Applied and environmental chemistry of animal manure: A review. Pedosphere 2016, 26, 779–816. [Google Scholar]

- Tabak, M.; Lisowska, A.; Filipek-Mazur, B. Bioavailability of Sulfur from Waste Obtained during Biogas Desulfurization and the Effect of Sulfur on Soil Acidity and Biological Activity. Processes 2020, 8, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holatko, J.; Brtnicky, M.; Mustafa, A.; Kintl, A.; Skarpa, P.; Ryant, P.; Baltazar, T.; Malicek, O.; Latal, O.; Hammerschmiedt, T. Effect of Digestate Modified with Amendments on Soil Health andPlant Biomass under Varying Experimental Durations. Materials 2023, 16, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinze, S.; Hemkemeyer, M.; Schwalb, S.A.; Khan, K.S.; Joergensen, R.G.; Wichern, F. Microbial Biomass Sulphur—An Important Yet Understudied Pool in Soil. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscolo, A.; Mallamaci, C.; Settineri, G.; Calamarà, G. Increasing soil and crop productivityby using agricultural wastes pelletized with elemental sulfur and bentonite. Agron. J. 2017, 109, 1900–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscolo, A.; Romeo, F.; Marra, F.; Mallamaci, C. Transforming agricultural, municipal and industrial pollutant wastes into fertilizers for a sustainable healthy food production. J. Environ. 2021, 17, 113771. [Google Scholar]

- Panuccio, M.R.; Attinà, E.; Basile, C.; Muscolo, A. Use of Recalcitrant Agriculture Wastes to Produce Biogas and Feasible Biofertilizer. Waste Biomass Val. 2016, 7, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panuccio, M.R.; Papalia, T.; Attinà, E.; Giuffrè, A.; Muscolo, A. Use of digestate as an alternative to mineral fertilizer: Effects on growth and crop quality. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2019, 65, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Pishgar-Komleh, S.H.; Akram, A.; Keyhani, A.; Raei, M.; Elshout, P.M.F.; Huijbregts, M.A.J.; van Zelm, R. Variability in the carbon footprint of open-field tomato production in Iran—A case study of Alborz and East-Azerbaijan provinces. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 1510–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, K.; Hawes, C.; Squire, G.; Hilton, A.; Wale, S.; Smith, P. Carbon footprints of food crop production. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 2009, 7, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Six, J.; King, A.P.; Kessel, C.V.; Rolston, E.D. Tillage and feld scale controls on greenhouse gas emissions. J. Environ. Qual. 2006, 35, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldaya, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. The water needed for Italians to eat pasta and pizza. Agric. Syst. 2010, 103, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapagain, A.K.; Orr, S. An improved water footprint methodology linking global consumption to local water resources: A case of Spanish tomatoes. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, G.; Ridoutt, B.; Bellotti, B. Carbon and water footprint tradeoffs in fresh tomato production. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 32, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Methods of Analysis for Soils of Arid and Semi-Arid Regions; Food and agricultural organization: Rome, Italy, 2007; p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Bouyoucos, G.J. Hydrometer method improved for making particle size analysis of soils. Agron. J. 1962, 54, 464–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlich, A. Rapid Determination of Cation and Anion Exchange Properties and pHe of Soils. J. Assoc. Off. Agric. Chem. 1953, 36, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkley, A.; Black, I.A . An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934, 37, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjeldahl, J. Neue Methode zur Bestimmung des Stickstoff in organishen Kopern. Anal. Chem 1883, 22, 354–358. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminsky, R.; Muller, WH. The extraction of soil phytotoxins using neutral EDTA solution. Soil Sci. 1977, 124, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, E.D.; Brookes, P.C.; Jenkinson, D.S. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biol Biochem 1987, 19, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Mersi, W.; Schinner, F. An improved and accurate method for determining the dehydrogenase activity of soils with iodonitrotetrazolium chloride. Biol Fertil Soils 1991, 11, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuush, H.; Bjorklund, M.; Rystrion, L. Purification and characterization of a novel bromoperoxidase-catalase isolated from bacteria found in recycle pulp white water. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2001, 28, 617–624. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, G.; Duncan, H. Development of a sensitive and rapid method for the measurement of total microbial activity using fluorescein diacetate (FDA) in a range of soils. Soil Biol Biochem 2001, 33, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valášková, V.; Šnajdr, J.; Bittner, B.; Cajtham, T.; Merhautová, V.; Hofrichter, M.; Baldrian, P. Production of lignocellulose-degrading enzymes and degradation of leaf litter by saprotrophic basidiomycetes isolated from a Quercus petraea forest. Soil Biol. Biochem 2007, 39, 2651–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidari, M.; Ronzello, G.; Vecchio, G.; Muscolo, A. Influence of slope aspects on soil chemical and biochemical properties in a Pinus laricio forest ecosystem of Aspromonte (Southern Italy). Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2008, 44, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandeler, E.; Gerber, H. Short-term assay of soil urease activity using colorimetric determination of ammonium, Biol. Fert. Soils 1988, 6, 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- UNI EN ISO 14044:2006; Environmental Management, Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Maffia, A.; Palese, A.M.; Pergola, M.; Altieri, G.; Celano, G. The Olive-Oil Chain of SalernoProvince (Southern Italy): A LifeCycle Sustainability Framework. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PCR- Product Category Rules. ARABLE AND VEGETABLE CROPS UN CPC 011, 012, 014, 017, 0191. Version 1.0.1 Valid ultil: 2024-12-07. Available online: https://environdec.com/pcr-library/with-documents (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- CML; Bureau, B.G. Life Cycle Assessment: An Operational Guide to the ISO Standards; School of SystemEngineering, Policy Analysis and Management, Delft University of Technology: Delft, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra, A.Y.; Chapagain, A.K.; Mekonnen, M.M. The Water Footprint Assessment Manual: Setting the Global Standard; Earthscan: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- FAO, 2010. Database CROPWAT.

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration: Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements; FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper No. 56; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, D.; Wang, S.; Chen, B. The Blue, Green and Grey Water consumption for crop Production in Heilongjiang. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 3908–3914. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini, G.; Ingrao, C.; Camposeo, S.; Tricase, C.; Contó, F.; Huisingh, D. Application of water footprint to olive growing systems in the Apulia region: A comparative assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2407–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Council. Directive n 91/676/EEC of 12 December 1991 Concerning the Protection of Waters against Pollution Causedby Nitrates from Agricultural Sources.

| Month | Decade | Stage | Kc | ETc | ETc | Eff rain | Irr. Req. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| coeff | mm/day | mm/dec | mm/dec | mm/dec | |||

| May | 2 | Init | 0.6 | 2.24 | 13.4 | 8.4 | 6.4 |

| May | 3 | Init | 0.6 | 2.45 | 26.9 | 14.1 | 12.9 |

| Jun | 1 | Init | 0.6 | 2.7 | 27 | 14.6 | 12.3 |

| Jun | 2 | Deve | 0.64 | 3.12 | 31.2 | 14.3 | 16.9 |

| Jun | 3 | Deve | 0.78 | 3.76 | 37.6 | 13.6 | 24 |

| Jul | 1 | Deve | 0.93 | 4.31 | 43.1 | 12.4 | 30.8 |

| Jul | 2 | Deve | 1.07 | 4.92 | 49.2 | 11.4 | 37.8 |

| Jul | 3 | Mid | 1.18 | 5.9 | 64.9 | 12.8 | 52 |

| Aug | 1 | Mid | 1.18 | 6.61 | 66.1 | 14.9 | 51.2 |

| Aug | 2 | Mid | 1.18 | 7.14 | 71.4 | 16.3 | 55.2 |

| Aug | 3 | Mid | 1.18 | 6.65 | 73.1 | 15.6 | 57.6 |

| Sep | 1 | Late | 1.17 | 6.01 | 60.1 | 14.6 | 45.5 |

| Sep | 2 | Late | 1.07 | 5.1 | 51 | 14.1 | 36.9 |

| Sep | 3 | Late | 0.95 | 3.9 | 39 | 13.9 | 25 |

| Oct | 1 | Late | 0.85 | 2.83 | 17 | 7.3 | 10.9 |

| Impact categories | Unit | CTR | A | B | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abiotic depletion | kg Sb eq | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Abiotic depletion (fossil fuels) | MJ | 15055.69 | 17769.39 | 27543.07 | 15335.07 |

| Global warming (GWP100a) | kg CO2 eq | 1083.46 | 1497.40 | 1346.10 | 1329.77 |

| Ozone layer depletion (ODP) | kg CFC-11 eq | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Human toxicity | kg 1.4-DB eq | 494.38 | 650.97 | 530.92 | 508.03 |

| Fresh water aquatic ecotox. | kg 1.4-DB eq | 523.45 | 634.97 | 540.73 | 534.12 |

| Marine aquatic ecotoxicity | kg 1.4-DB eq | 629032.75 | 803512.81 | 678553.69 | 648589.00 |

| Terrestrial ecotoxicity | kg 1.4-DB eq | 1.02 | 1.57 | 1.24 | 1.09 |

| Photochemical oxidation | kg C2H4 eq | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 0.19 |

| Acidification | kg SO2 eq | 7.36 | 15.95 | 9.74 | 8.77 |

| Eutrophication | kg PO4--- eq | 1.96 | 4.16 | 2.28 | 2.50 |

| Impact categories | Unit | CTR | A | B | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abiotic depletion | kg Sb eq | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Abiotic depletion (fossil fuels) | MJ | 320.33 | 309.03 | 474.88 | 262.59 |

| Global warming (GWP100a) | kg CO2 eq | 23.05 | 26.04 | 23.21 | 22.77 |

| Ozone layer depletion (ODP) | kg CFC-11 eq | 0,00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Human toxicity | kg 1.4-DB eq | 10.52 | 11.32 | 9.15 | 8.70 |

| Fresh water aquatic ecotox. | kg 1.4-DB eq | 11.14 | 11.04 | 9.32 | 9.15 |

| Marine aquatic ecotoxicity | kg 1.4-DB eq | 13383.68 | 13974.14 | 11699.20 | 11105.98 |

| Terrestrial ecotoxicity | kg 1.4-DB eq | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Photochemical oxidation | kg C2H4 eq | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Acidification | kg SO2 eq | 0.16 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.15 |

| Eutrophication | kg PO4--- eq | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Cultivation system | Yield (ton/ha) |

Et green (m3/ha) |

Et blue (m3/ha) |

Direct and indirect fraction (m3/ha) |

WFP green (m3/ton) |

WFP blue (m3/ton) |

WFP grey (m3/ton) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTR | 47.0 | 1983 | 1914 | 750.02 | 42.19 | 56.68 | - | ||

| A | 57.5 | 1983 | 1914 | 750.65 | 34.49 | 46.34 | 0.39 | ||

| B | 58.0 | 1983 | 1914 | 896.07 | 34.19 | 48.45 | 0.098 | ||

| C | 58.4 | 1983 | 1914 | 750.02 | 33.96 | 45.62 | 0.039 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).